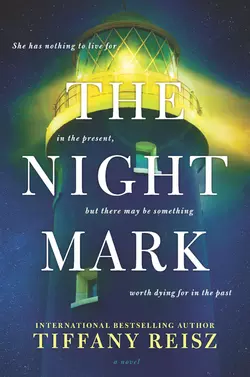

The Night Mark

Tiffany Reisz

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Фэнтези про драконов

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 386.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From the bestselling author of The Bourbon Thief comes a sweeping tale of loss and courage, where one woman discovers that her destiny is written in sand, not carved in stone.Faye Barlow is drowning. After the death of her beloved husband, Will, she cannot escape her grief and most days can barely get out of bed. But when she′s offered a job photographing South Carolina′s storied coast, she accepts. Photography, after all, is the only passion she has left.In the quaint beach town, Faye falls in love again when she sees the crumbling yet beautiful Bride Island lighthouse and becomes obsessed with the legend surrounding The Lady of the Light–the keeper′s daughter who died in a mysterious drowning in 1921. Like a moth to a flame, Faye is drawn to the lighthouse for reasons she can′t explain. While visiting it one night, she is struck by a rogue wave and a force impossible to resist drags Faye into the past–and into a love story that is not her own.Fate is changeable. Broken hearts can mend. But can she love two men separated by a lifetime?