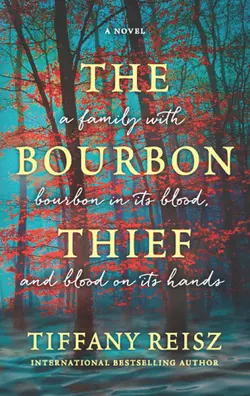

The Bourbon Thief

Tiffany Reisz

Betrayal, revenge and a family scandal that bore a 150–year–old mystery.When Cooper McQueen wakes up from a night with a beautiful stranger, it's to discover he's been robbed. The only item stolen—a million-dollar bottle of bourbon. The thief, a mysterious woman named Paris, claims the bottle is rightfully hers. After all, the label itself says it's property of the Maddox family who owned and operated the Red Thread Bourbon distillery since the last days of the Civil War, until the company went out of business for reasons no one knows… No one except Paris.In the small hours of a Louisville morning, Paris unspools the lurid tale of Tamara Maddox, heiress to the distillery that became an empire. Theirs is a legacy of wealth and power, but also of lies, secrets and sins of omission. Why Paris wants the bottle of Red Thread remains a secret until the truth of her identity is at last revealed, and the century-old vengeance Tamara vowed against her family can finally be completed.

Betrayal, revenge and a family scandal that bore a 150–year–old mystery

When Cooper McQueen wakes up from a night with a beautiful stranger, it’s to discover he’s been robbed. The only item stolen—a million-dollar bottle of bourbon. The thief, a mysterious woman named Paris, claims the bottle is rightfully hers. After all, the label itself says it’s property of the Maddox family who owned and operated the Red Thread Bourbon distillery since the last days of the Civil War, until the company went out of business for reasons no one knows… No one except Paris.

In the small hours of a Louisville morning, Paris unspools the lurid tale of Tamara Maddox, heiress to the distillery that became an empire. Theirs is a legacy of wealth and power, but also of lies, secrets and sins of omission. Why Paris wants the bottle of Red Thread remains a secret until the truth of her identity is at last revealed, and the century-old vengeance Tamara vowed against her family can finally be completed.

The Bourbon

Thief

Tiffany Reisz

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

To Kentucky, my home

Contents

Cover (#uf130fb95-1fc8-5956-938f-4982334a481a)

Back Cover Text (#u60610a40-5a90-5d50-9d18-5ab3dc3c967a)

Title Page (#u4994e081-84fd-5d95-8dde-e2db25929534)

Dedication (#ud75b146e-f0c7-5ca6-8f1a-b4d85d9bbcbb)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_75ea2b88-9503-5111-810c-105ee0260663)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_1223c146-1d62-58e3-9370-b43ac516ea77)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_c481d0d6-fc6b-5165-8177-6172d8c24d09)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_2d393ef7-8c6b-56d1-8e63-ac34d70fcca9)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_820c6f3b-b688-5984-a02a-5cd5f9f4abeb)

Chapter 6 (#ulink_a160afca-f0c9-5783-a590-07a1d273d2d1)

Chapter 7 (#ulink_d155e0e3-aa4d-53d1-b3b6-4927e2620b37)

Chapter 8 (#ulink_5ef662fa-353a-5130-a3b0-0494f062eac8)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

HISTORICAL NOTES AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#ulink_b3023963-8825-5674-a38c-55c147f14124)

Paris

There wasn’t much in the world Cooper McQueen cared about more than a good bourbon. In his forty-five years, not one single beautiful woman had managed to persuade him to set down his drink and leave it down. But when the woman in the red dress walked into his bar—a gift from the gods tied in a tight red bow—McQueen decided he might have seen the one woman on earth who could turn even him into a teetotaler. Her dress was tight as old Scrooge’s fist, red as Rudolph’s nose, and looking at her, McQueen had only one thought—Christmas had come awfully early this year.

Miss Christmas in July glanced his way, smiled like she knew what he was thinking and was thinking along the same lines herself, and McQueen figured he’d be leaving the bar early tonight and nobody better try to talk him out of it.

Not wanting to appear too eager, he continued to sip his bourbon—neat—as he kept her in his peripheral vision. Christmas in July walked over to the bar and took a seat. He watched her study the menu and he smiled behind his glass. In one minute he’d go over to her, buy her a drink, let it slip he owned the bar, dangle out the bait, see if she was in the mood to nibble. He’d seen his fair share of beautiful women in his bar, usually too young—he had some pride, after all—but Miss Christmas looked a respectable thirty-five. A real woman. A grown woman. The sort he could sleep with without apology. She had dark skin and black hair that lay in heavy coils down her back and tied at the nape of her neck with a red ribbon he fully intended to untie with his teeth given the opportunity.

One minute up, he went to claim the opportunity.

It didn’t break McQueen’s heart to excuse himself from his current conversation with someone who was either an investment banker or a venture capitalist. He had stopped listening the moment Miss Christmas walked in. He went over to her and sat in the empty bar stool to her left without waiting for an invitation. He owned the place. No reason not to act like it.

He didn’t say anything at first. He let the silence linger and grow as heady as the muddy Ohio River on a hot night, the kind that made even the sidewalks sweat. Maybe he could talk the lady into a stroll over to the river while the night was still warm. Maybe he could talk her into something more.

“What can I get you?” Maddie, the pretty blonde bartender, asked the woman.

“How about a shot of Red Thread?” the woman said. “I like to match my drinks to my hair ribbon.”

“Red Thread?” Maddie glanced at McQueen, a silent plea for help. “I don’t think...”

“Red Thread’s been out of business for thirty-five years,” McQueen said to Maddie.

“Oh, good. Thought I was going crazy. Could have sworn I knew every bourbon there was,” Maddie said. “Any bottles left?”

“Not a one,” McQueen said, not a white lie, not a black lie. A little red lie.

“What a shame,” Miss Christmas said, although she sounded neither surprised nor disappointed. Christmas was right. Her voice had a frosty tone to it. She was cool. He liked cool.

“A damn shame. They say it was the best bourbon ever bottled.” McQueen waited for the lady in the red dress to speak again, but she stayed silent, listening, alert, eyes only for Maddie at the moment.

“What happened to it?” Maddie asked him.

“Warehouse fire,” McQueen said, shrugging. “It happens. You distill alcohol and store it in wooden barrels? Fire’s your worst nightmare. Red burned to the ground in 1980 and never reopened. No one knows who owns it anymore.” McQueen had tried to buy the old Red Thread property himself but had no luck. He’d gotten as far as finding the shell company—Moonshine, Ltd.—that owned the acreage and the trademark, but it didn’t seem to have a human being behind its name. “I would know because I’ve looked.”

“Isn’t that interesting...” Miss Christmas said with the hint of a smile on her red lips, and he couldn’t tell if she meant it or if she was being sarcastic. She spoke with a Kentucky accent, faint but recognizable to someone who spent half his time in New York and half his time in Louisville. Kentucky accents sounded like home to him and his ears always perked up when he heard one.

“Can I get you something else?” Maddie asked the woman.

“Four Roses, neat. Double pour.”

“A lady who knows her bourbon and isn’t afraid to drink it straight.” McQueen turned ten degrees on his bar stool toward her. “A woman after my own heart.”

“I’m a Kentucky girl,” she said with a graceful shrug. “And bourbon’s like the truth, you know.”

“How’s that?”

“The first taste burns, but once you get used to it, it’s the only thing you want in your mouth.”

Miss Christmas brought the shot glass to her lips, took a sip and didn’t flinch as she drank it. The bourbon didn’t burn her.

“Tell me something true, then,” McQueen said. “What’s your name?”

“Paris.”

“Beautiful name.”

“Thank you, Mr. McQueen.”

“You know who I am?”

“Everybody knows who you are. You own this bar,” she said, nodding at the words The Rickhouse, Louisville, Kentucky, engraved on the mirror behind the bar, the image of a turn-of-the-century wood warehouse also etched in the glass. “I hear you’re opening another bourbon bar in Brooklyn.”

“You don’t approve?”

“Leave it to white people to turn a beautiful drink like bourbon into a fetish. Find a way to make pumpkin spice bourbon, and you’ll be a billionaire.” She took another sip of her Four Roses, all the while looking at him out of the side of her eyes.

“I’ll tell you a secret.”

“Tell it.”

“I’m already a billionaire. But I’m always looking for a new way to waste my money. Why not?”

“You need another business? You tired of owning your basketball team already?”

“I only own part of the team.”

“Which part?” she asked. “I know which part I’d like to own.”

McQueen laughed. “Tell me something, Miss Paris—what do you own?”

Now it was her turn to spin on her bar stool, ninety degrees, and she met him face on with full eye contact, fearless and shameless.

“I could own you by morning.”

Her words rendered McQueen momentarily speechless. He couldn’t remember the last time any woman had so thoroughly stupefied him. Bourbon on her lips and curves on her hips. He was halfway in love with her already.

“I would like to see you try,” McQueen said. “And that’s not a challenge. I really would like to see that with my own eyes.”

“Shall we?” she asked, raising her eyebrow a fraction of an inch.

He had to know her. “Yes,” he said. “Yes, we shall.”

They left the bar together but drove separately to his house. As he wove his way through downtown traffic, he saw that somehow he’d lost her behind him. He’d given her his address and she surely didn’t need to follow him to find it. An irrational fear took hold of him between the red light and the green, a fear she’d changed her mind, driven off, considered a better offer somewhere else with someone else. No, surely not. She’d wanted him, he knew it. He’d seen avarice in her eyes at the bar, and whether it was for his face, his money or his reputation as the richest man in Kentucky, he didn’t care. They were all true, all parts of him, anyway. Whatever part of him she wanted, he didn’t care as long as she wanted him. She did want him, didn’t she? Irrational thoughts. Irrational fears.

Yet he couldn’t shake the feeling that he must see her tonight, be with her. Anything less would be calamitous. A man needed wanting. What was the point of having wealth, power and the body of a man half his age if no one bothered to use him for it?

McQueen pulled into his driveway and saw a black Lexus already there and waiting. Self-respect prevented him from sighing in his relief, but even a self-respecting man was allowed to smile. She’d simply taken a different route. No big surprise. If she lived anywhere around here, she’d know about his house. Everybody in town knew about Lockwood—named not for the forest that surrounded the property he kept locked behind stone walls, but for the man who built it in 1821. Old by American standards, but McQueen’s family was Irish. A two-hundred-year-old house was just getting comfortable by his grandfather’s standards. And McQueen tended to judge everything by his grandfather’s standards.

Lockwood was a redbrick three-story Georgian masterpiece with double-height white porticos protected by a twelve-foot-high wrought-iron gate. He and Paris parked in the circular cobblestone driveway in front of the temple-style porch. She emerged from her car all long legs and slim ankles and red shoes, and she didn’t blink at the house. It seemed to make no impression on her whatsoever. Miss Paris must have her own money. The shoes, the dress, the Birkin bag that was nearly identical to the one his ex-wife carried? All that screamed money to him. No one was that unimpressed by money except people who have it.

Before entering the house, she paused on the front porch and glanced back at the gate.

“What?” he asked.

“Pretty fence,” she said. “Traditional Kentucky rock fence.”

“Glad you like it,” he said, admiring the view from the porch. The perimeter of the Lockwood property was a rock fence built in the nineteenth century. “I had it built just for you.”

“To keep me in or to keep me out?”

“To keep you surrounded by beautiful things. As you should be.”

She raised her eyebrow slightly and without another word turned and walked into the house. If she hadn’t been looking, McQueen might have patted himself on the back. Good line.

“Welcome to Lockwood,” McQueen said, glad it was late enough all the staff but his security guard were gone. “Hope you like it.”

“Very nice,” she said, barely giving the opulent interior a glance. McQueen didn’t mind that much. He’d rather she looked at him than his foyer, and she was definitely looking at him. Women considered him handsome, and even if they didn’t, they considered him rich, which was usually enough to close the deal.

“I’m the fourth generation of McQueens to live here. My great-grandfather bought this house when he came over from Ireland,” McQueen said. It was summer, warm, and she wasn’t wearing a coat for him to offer to take. He wasn’t sure what to do with his hands. At his age he should have his seduction skills down by now, but Paris made him nervous for a reason he couldn’t name. “He’d planned to settle his family farther west, but the hills reminded him of home. So he stayed.”

“And here we are. What would your great-grandfather have said about you bringing me to his home?”

“I’d like to think he’d have taken one look at you and said, ‘Good job, lad.’”

“I’ll be the judge of how good the job is done.”

“Maybe we should get to work, then.” He reached for her and kissed her under the crystal chandelier, which before today had looked elegant to him, but tonight seemed ostentatious compared to the elegance of this woman in her red dress. She tasted of apples and bourbon when he kissed her and she was right—it did burn, but once he had his first taste, she was all he wanted in his mouth.

McQueen pressed her back against the banister of the spiral staircase that led upstairs. He hooked her leg around his hip, slid his hand up her long bare thigh. She had panties on, but they weren’t enough to keep his fingers out of her. He stepped back, pulled them down her thighs and left them on the floor, where he hoped they would stay until morning.

“Did you plan to seduce me when you came to the bar?” he asked against her lips.

“Yes.”

“Are you after my money?” He sensed such a woman wouldn’t be insulted by such a question.

“Only your bourbon, Mr. McQueen.”

“You want to see my collection?” he asked. “I promise it’s nothing but booze. I don’t own a single etching.”

McQueen and his world-class bourbon and whiskey collection had recently been profiled in Cigar Aficionado magazine, inspiring a few phone calls from collectors trying to buy some of his rarer vintages, but she was his first official bourbon groupie.

“Eventually,” she said, spreading her legs a little wider for him, inviting his fingers a little deeper. “Once you’re done showing me everything else you’ve got.”

McQueen showed her. First he showed her right there against the wall. Then he took her up to the master bedroom, a room baroque with ornamentation and ostentation. Even the bed was gilt. He never actually slept in the room if he could help it. He found other uses for it, however. And that red dress of Paris’s looked about as good on his floor as the priceless gold-and-green Persian rug it lay upon.

When it was all over, Paris reached for her red dress, and it occurred to him that if he let her leave now, he wouldn’t be likely to ever see her again. Something told him he shouldn’t let her go. Something told him if all he did was sleep with her, he would forfeit something, a victory or a prize.

“Don’t leave,” he said as he obliged her by zipping the dress up for her. She had such a lovely back and the light of the bedside Tiffany lamp danced over her dark skin like a tongue of fire. “I haven’t shown you my collection yet.”

“Oh, yes, I’d almost forgotten,” she said, cool as could be. He wasn’t used to women this quiet and unimpressed by being in the bedroom of a billionaire. Too cool.

“I don’t know what to make of you,” he said, narrowing his eyes at her as she wrapped the red ribbon around her hair and pulled the long locks over her shoulder, Venus at her toilette.

“Make of me? Are you putting me in a pie?”

McQueen laughed. “I’d rather keep you in the bedroom than the kitchen. Come on, tell me about yourself.”

“My name is Paris. I was born and raised in Kentucky. I moved to South Carolina for school. I got married a couple years ago, inherited money when my husband died, and now I’m back. I have no children. I am no one special. You only think I’m mysterious because you’ve noticed I’m not terribly interested in spending the rest of my life with you and that is one mystery a man like yourself can’t solve.”

“That hurts.”

“No, it doesn’t.”

McQueen raised his eyebrow. “A rich widow. That explains a lot.”

“What does it explain?”

“Why I don’t impress you. You have your own money.”

“You tell yourself that’s the reason,” she said with a smile sweet as the pie he should put her in, and goddammit, McQueen wanted her again already. She made him forget he was forty-five. “I won’t contradict you.”

“I’m going to impress you before you leave,” he said. “Watch me.”

“I’m watching.”

He dressed in his suit minus the jacket and tie and led her from the bedroom, down the hall and to a bookcase. On the bookcase were unread leather-bound volumes of all the classics.

“Very nice,” Paris said. “Did your decorator provide the books? Or did you order them from the pretty book wholesale warehouse?”

“This isn’t it,” he said. “I’m going to show you my prized possession.” He pulled on the middle shelf of the bookcase, revealing that it wasn’t simply a bookcase, but a door. He switched on a floor lamp inside the door and waved Paris inside. As she gazed around the hidden room, he watched her face. She revealed nothing—no shock, no surprise, no disappointment.

“Cozy,” Paris said, but from her tone she might have meant “airless.” He watched her take note of the old stone fireplace, the antique sofa with the worn jade fabric and the carved ebony arms. She walked to the wall and pulled back the curtain to reveal...nothing.

“You covered your window with a wooden board?” Paris asked, tapping the board.

“That’s a mirror,” he said. “I don’t want anyone looking in here. And really, what’s more terrifying than peeking in the window of a house and seeing yourself?”

McQueen retrieved the key he’d hidden in a small silver vase on top of the fireplace mantel and opened a satin bronze cabinet with the Twelve Apostles embossed on the side.

“Is that a tabernacle?” Paris asked.

“It is.”

“You store your alcohol in a cabinet designed to hold communion wafers?”

“My grandfather had a dark sense of humor where the Catholic Church was concerned.”

“I assume he was Catholic?”

“Until he fell in love with a girl who left him for the Carmelites. Never stepped foot in a church again after that. Said no man with any pride would enter the house of the man who stole his wife.”

“Pride indeed. Sounds like his lady picked the right man. You exist, so I assume he got over his lover’s defection?”

“Got married, yes, but he never got over it. All the McQueens are heathens now, but I do consider this room my little sanctuary. Every man needs one.” He took a bottle out of the cabinet and handed it to her.

“This is it?” she asked, cradling the bottle carefully in her hands.

“That’s it. You ordered Red Thread at the bar tonight. That, my dear, is the first bottle of Red Thread ever distilled, ever bottled, ever-ever.”

“How did you come by this bottle?”

“Private sale. One million dollars. The provenance is perfect. Virginia Maddox herself sold it shortly before she died to pay her medical bills. One of a kind.”

“No wonder you won’t sell it,” she said.

“Not for all the money in the world. This is the holy grail of bourbon. You don’t sell the holy grail.”

“Unholy grail,” she said under her breath, but not so far under he didn’t hear it.

Her eyes softened as she touched the red ribbon tied around the bottle’s neck. It was a tattered old thing.

“It’s a miracle that thing has stayed on there,” McQueen said. “Piece of ribbon from the 1860s.”

“Slave cloth,” Paris said.

“What?”

“The ribbon was cut from slave cloth. Thick wool. Slave cloth was made to last a long time. Slaves didn’t get new clothes very often. What they had had to last, had to hold up to hard work and many years. The girl who wore this ribbon? This was probably the only nice thing she had, the only thing she thought of as hers.”

“I’m sorry. I didn’t know that ribbon... I didn’t know that part of the story, that the ribbon came from a Maddox slave.”

“Now you know.”

“You ordered Red Thread at The Rickhouse. But you would have been a baby when Red Thread burned down. What exactly is your interest in it?”

“It interests me for many reasons. But here, you can’t trust me with that bottle. I might drop it. Wouldn’t that be a shame?”

She passed the bottle back to McQueen. He put it carefully back into the cabinet. When he turned around, Paris was halfway to the door.

“You aren’t leaving, are you?” he asked.

“Leaving for the bedroom,” she said.

“So I did impress you?”

“You have a fine collection,” she said. “I only wish it were mine.”

McQueen followed her to the concealed door and started to open it for her. With his hand on the knob he looked her up and down and into her eyes.

“Who are you really?” he asked.

“You don’t want to know.”

“Why not?”

“I told you why. The truth is like bourbon—it’ll burn going down.”

“I want to burn.”

She kissed him, hard enough McQueen forgot about finding out anything else about her except how to make her come again. And after he’d solved that mystery, he fell fast asleep, one arm over her naked stomach, one leg over her leg, his favorite way to fall asleep.

* * *

When McQueen woke up, he was alone, and Paris had left nothing behind but the scent of her skin on his sheets and her red hair ribbon on his pillow.

Red ribbon?

Hell on earth, he was a first-rate fool.

McQueen pulled on his pants and shirt and ran to the room behind the bookcase.

Too late. She was gone.

So was his million-dollar bottle of Red Thread.

2 (#ulink_d624e5f6-36a3-51df-8d44-46eb1a25a184)

McQueen slammed his hand down onto the intercom button and ordered his night shift security guard to lock the gates.

“Already done,” James answered. “Someone tried to get out without the gate code. She’s in my office. I was about to come wake you up, boss.”

He should have been relieved, but he seethed instead, his shoulders tense with his fury, and he nearly wrenched the door off the hinges when he entered the security guard’s small shed. Paris sat primly on a small folding chair, her legs crossed at the ankles, her black Birkin bag in her lap.

“Give us a minute,” McQueen said to the guard.

“Do I need to call the cops?”

“Not yet. I want to hear her story first. Then we’ll call them.”

James left him alone in the shed with Paris. She looked up at him placidly.

“Are all your servants black?” she asked, nodding at the door that James had closed behind him.

“They’re not servants. They’re employees. And no. My housekeeper is white. The security guard who works the day shift is from Mexico.”

“The United Colors of Yes-Men.”

“And yes-women,” McQueen said. He crossed his arms and leaned back against the door. “You’re good. You wore me out, and when I slept...”

“I’m not good. You’re easy.”

“Am I?”

“Interview in the June 2014 Architectural Digest with billionaire investor Cooper McQueen. ‘What do you like to read, Mr. McQueen?’ the fawning interviewer asked you. ‘What keeps Cooper McQueen up all night?’ And you replied—”

“Raymond Chandler.”

“Because, as you said in the interview, ‘I’m a sucker for a femme fatale. Give me a girl with a black heart in a red dress and I’m a goner.’”

“You thought you could seduce me because I read Chandler?”

“And your last girlfriend was a dark-skinned Knicks City Dancer from Puerto Rico, so I knew I had a very good shot at you. I’m your type, aren’t I?”

“I don’t have a fetish for dark-skinned women, if that’s what you’re implying.”

“I wasn’t implying anything, but you immediately seemed to think it was what I was implying. Methinks the billionaire doth protest too much.”

“Of all the bars in all the world...you walked into mine to steal my bourbon. You know, stealing something worth a million dollars is a felony.”

“I know. But I won’t call the police on you if you don’t call the police on me.”

“I didn’t steal it.”

“You bought stolen goods. Also a felony.”

“That bottle wasn’t stolen.”

“I know it was.”

“I told you, Virginia Maddox sold it—”

“It didn’t belong to Virginia Maddox. You can’t sell what you don’t own. And I was happy to buy it from you and avoid an unpleasant legal battle, but as you refused to sell it, I had no choice but to repossess it,” she said with the slightest sinister hiss.

“How do you know all this? How do you know everything you think you know about Red Thread?”

“I am Red Thread,” Paris said with the slightest sigh like she was admitting to a bad habit.

“Red Thread is dead.”

“A nice rhyme. You should have been a poet.” She raised her chin toward the filing cabinet. On top of it sat the bottle. “Look at it. Read the label. Tell me what it says.”

McQueen knew what the label said, but he took the bottle anyway and held it label side up toward the light.

The label was faded and yellowed, close to peeling. It was a hundred and fifty years old, after all. The font was an elegant script that said “Red Thread—Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey.” Beneath those words it read “Distilled and bottled—Frankfort, Kentucky.” And underneath that in tiny script he read, “‘Owned and operated by the Maddox family, 1866.’”

“There we go,” Paris said.

“Where do we go?”

“Owned by the Maddox family.”

“You aren’t the Maddox family.”

“Are you saying that because they were white and I’m not?”

“I’m saying that because I’ve looked for the Maddox family for years, and I haven’t found a single one of them, by blood or by marriage, who had anything to do with Red Thread. The whole Kentucky line died or disappeared after the distillery burned.”

“Why did you look for us?”

“First of all, I don’t believe you are a Maddox. You’re going to have to show me some proof.”

“You’re holding the proof in your hands. One hundred proof.”

“Funny.”

“Oh, yes,” she said with an exaggerated Southern drawl. “I’m a card. Why were you looking for us?” she asked again.

“I wanted to buy Red Thread. What’s left of it. I’ve been wanting to open my own distillery for years. Red Thread is part of Kentucky history. I’d like to be part of Kentucky’s present.”

“Some things are better off history.”

“Bourbon isn’t one of them.”

“It’s too late anyway, Mr. McQueen. Someone else beat you to it.”

“Beat me to what? Buying Red Thread?”

“Reopening the distillery. Under a new name, of course. And under new management.”

McQueen understood at once.

“You,” he said. “You’re Moonshine, Ltd.? I tried to contact you.”

“That’s my company, yes.”

“You own the old Red Thread property?”

“Owner, operator and master distiller.”

“You?”

“You don’t think a woman can be a master distiller? I have my PhD in chemistry. You can call me Dr. Paris if that sort of thing turns you on.”

“I get it,” McQueen said, nodding. “I do. This is the first ever bottle of Red Thread, the original bottle. Part of the company’s history and you want it because you own Red Thread now. Makes sense. I’m even sympathetic. I might even have loaned it to you to put on display when the company reopens for business. But now you’ve pissed me off. And if you don’t tell me one very good reason why I shouldn’t call the police, I’m picking up the phone in three seconds. Three...two...”

“I can tell you what happened to Red Thread,” she said. “I can tell you the whole story. The whole truth.”

Well.

That got his attention.

“You know why it burned down?”

“I know everything. But if I were you, I wouldn’t ask. By the time I’m done telling you the story, you’ll hand over that bottle with your compliments and an apology.”

“Must be one hell of a story, then.”

“It’s what brought me here, the story.”

“Your story?”

“My story. I inherited it.”

“I think I’d rather inherit money than a story.”

“I have that, too, not entirely by my choice.”

“You don’t want to be rich?”

“God favors the poor. But don’t tell rich people that. It’ll hurt their little feelings.”

McQueen sighed and sat back. He buttoned the middle buttons of his shirt, crossed his leg over his knee. He should call the cops. Why hadn’t he called the cops? Embarrassed he’d fallen for the oldest trick in the book? Beautiful woman in red goes home with him, fucks him and robs him while he sleeps. He could laugh at himself, but he wouldn’t let anyone else laugh at him. Yes, he could call the cops.

Or...

“They call bourbon the honest spirit,” he said. “You know why?”

“You aren’t legally allowed to flavor it with anything. Water, corn, barley, rye and that’s it. You see what you get. You get what you see. No artificial colors. No artificial sweeteners. No artificial nothing.”

“Right. So let’s drink a little honesty, shall we?”

“If you’re buying,” she said.

“I’m always buying.”

He picked up the bottle and slipped it into his pants pocket. He opened the door of the security shed and Paris stepped out into the warm night air. Almost 2:00 a.m., he should be in bed now. He’d hoped to be in bed with her. One of these days he’d learn. Not today apparently.

“Boss?” James asked, dropping his cigarette on the ground and crushing it under his boot.

“A misunderstanding.” McQueen had his hand on the small of Paris’s back. “Don’t worry about it.”

“Got it. Sleep well, Mr. McQueen.”

As they walked back into the house and up to his drinking closet, McQueen considered the possibility that he might be making the worst mistake of his life.

“Sit.” McQueen pointed at the jade sofa and Paris sat without a word of protest.

McQueen took the key from the silver bowl and put the bottle of Red Thread back into the cabinet.

“I shouldn’t have trusted you.” McQueen locked the cabinet and slipped the key into his pocket.

“You’re a rich white man. Not your fault for assuming the entire world is on your side. It must seem like it most days. Usually you’d be right, but times, Mr. McQueen, are a-changing.”

“That sounds like a threat.”

“Sounds like Bob Dylan to me.”

He needed a drink, a stiff one, so he poured each of them a shot. The entire time he kept an eye on her as he unscrewed the cap and measured out the bourbon. Now she seemed calm, but it wasn’t the calm of surrender. This was a cat’s version of calm. A calm that could turn into an attack or a run in an instant.

When she had her shot in hand and he had his, he lifted it in a toast, a toast she didn’t return. Instead, she merely sipped her bourbon.

“Pappy’s?” she asked.

“It is. You have a good palate.”

“You can taste the leather in it.”

He couldn’t, but it impressed him she could.

“You weren’t exaggerating. You do know your bourbon,” he said.

“They used to say that about the Maddoxes,” she said. “Ever since Jacob Maddox started the distillery and made himself a wealthy man in five years...they said it about all of us—the Maddoxes have bourbon in their blood.”

“I’ve seen the Maddox family tree. There is no Paris on it.”

“Perhaps you were looking at the wrong branches,” she said coldly.

His words had hit a sensitive spot and her eyes flashed in a familiar way. It was not his first encounter with her sensitive places, after all.

“Now that we both have an honest spirit in our hands,” McQueen said, “tell me something.”

“Anything,” she said, although he doubted the sincerity of that declaration. She was proving to be altogether miserly with her explanations and answers.

“Did you sleep with me just to steal my bottle?”

“Does that sting? I bet it stings.” She winced in feigned sympathy, shaking her head and clucking her tongue like a mother tending to the skinned knee of her child. Right then and there he made a realization—he didn’t like this woman, not at all.

“I think I could fuck you a thousand nights and never actually touch you.”

“Don’t feel bad,” she said. “You’re not the only one with rock fences around you. Built by the same people, too, as a matter of fact.”

“Irish immigrant stonemasons hired by my great-grandfather?”

Paris’s eyes widened slightly. Then she laughed. Finally. He knew he’d scored a point on her. True, most of the rock fences in Kentucky were built by slave labor. His was not, however, and somewhere he had the paperwork to prove it. While he didn’t know the game he and Paris were playing, he knew that while he wouldn’t win it, if he played it well enough, he might not lose it.

“You’re funny. And you’re handsome.” She tossed the compliment at him like a dollar bill at a stripper’s feet. “If it makes you feel any better, I didn’t have to fake anything with you. If I hadn’t wanted to sleep with you, I wouldn’t have. It was convenient that you were attractive. Otherwise, I might have simply hired someone to break into the house while you were away. Does that help?”

“I feel so much better now,” he said. “While we’re being honest...is it true? You’re widowed?”

“I am. Widowed at thirty-four.”

“Awfully young to lose a husband.”

“Not my husband, although he died too young for my liking. He was twenty-eight years older than I am.”

McQueen nearly choked on his Pappy’s. The youngest woman he ever slept with was eighteen years his junior and that relationship had lasted about as long as a bad movie.

“Twenty-eight. I guess that’s what they call a May/December romance.”

She smiled and it was a debt collector’s smile, and something told him she had come to make him pay up. “Twenty-eight years? That’s a January/December romance in a leap year.”

McQueen chuckled and raised his glass to her.

“What?” she asked.

“You get enough bourbon in you and you sound like a real Kentucky girl.”

“I am a real Kentucky girl. Born in Frankfort a stone’s throw from the Kentucky River. That’s not an exaggeration. With a good arm, you could hit the river from our porch.”

“That’s not a good neighborhood.”

“It was the only neighborhood we had. If you have a roof over your head and food in the fridge and nobody breaking down your door, it’s a good neighborhood.”

McQueen tried to take another drink of his bourbon and found his shot glass empty. He set it down again on his knee.

“So you slept with me and stole a million-dollar bottle of bourbon. You must really want that bottle.”

“I don’t want it, no. But I need it.” For the second time that night he saw a glimpse of the real woman behind the mask of the femme fatale, the woman in red. A determined woman.

“For what?”

“To finish something someone else started.” She glanced down at the bourbon in the glass she’d balanced on her knee. “You know what a bourbon thief is, Mr. McQueen?”

“It’s a sampling tube,” McQueen said. “You stick it in the bunghole of a bourbon barrel and extract the contents for tasting.”

“Isn’t that one hell of a visual metaphor?” Paris asked.

McQueen laughed big and long and loud.

“What’s your point?”

“Do I look like a bourbon thief to you?”

“You look like a woman who’s never stolen anything in her life.”

“I haven’t. That bottle belongs to my family. You will return it one way or another.”

“Apparently I’m going to give it to you by morning in exchange for a story. That’s quite a feat.”

“It’s quite a story.”

“Go on, then.”

McQueen looked at her as she crossed her long legs, pulled her hair over her shoulder and met his eyes without a hint of fear even though she was on the hook for a million-dollar heist. It made him nervous, what she was about to tell him, but he wanted to know. Knowledge was power and power was money, and no man ever got rich buying stock in ignorance.

“On December 10, 1978, two very important events in the history of Red Thread occurred—the Kentucky River broke its banks and crested at a record forty-eight feet, and the granddaughter of George J. Maddox, the owner of Red Thread Bourbon Distillery, turned sixteen years old. That was the beginning of the end of Red Thread.”

“What was? The river flooding?”

Paris gave him a smile, a smile that made him momentarily rethink his decision to not call the police.

“Tamara Maddox.”

3 (#ulink_49a54720-9569-5e32-ae7f-34079b80647c)

Veritas

1978

Tamara Maddox wanted to ride her horse the morning of her sixteenth birthday.

And whatever Tamara Maddox wanted to do, Tamara Maddox did.

In all fairness to the girl, spoiled as she was and she knew it, anyone would have wanted to get out of that house and any excuse would do. They’d been fighting again, Granddaddy and Momma. If only they yelled, that would have been one thing, something Tamara could roll her eyes at, laugh at, ignore by turning the volume up on her radio. But no, they whispered their fights behind closed doors, hissing at each other like snakes. Neither of them had the courtesy to tell her what they were fighting about, so Tamara assumed they were fighting about her.

Fine. If they wanted to fight on her birthday, she’d leave them to it. She had better things to do. And the urge to go riding only grew when she saw a blue Ford pickup truck with a white cab wheezing its way down the drive to the stables. What was Levi doing here on a Sunday? She hoped it was because he knew it was her birthday, but even Tamara Maddox wasn’t spoiled enough to think that was the case. Still, one more reason to go riding when one reason—she wanted to—was more than enough for her.

Tamara changed out of her pajamas and into her riding clothes—tan jodhpurs, black boots, a white blouse and a heavy coat—braided her long red hair and raced out to the barn. It was cold today—only forty-five by the thermometer in the barn—but she’d ridden in worse weather. Plus, the rain had stopped finally, and she’d been going stir-crazy inside the house. All she needed was an hour outside in the air with Kermit, her pale black Hanoverian pony, and everything would be all right again.

And if it wasn’t, at least she’d see Levi today, and if that didn’t make a girl feel better, nothing on God’s wet green earth would.

Levi barely acknowledged her when she ran into the barn. Nothing new there. She had to work for his attention and she worked for it very hard. In the summer she’d often catch him shirtless as he mucked out stalls and threw hay bales around. In winter she had to content herself with the memories of his lean strong body that she knew was hidden under his brown coat with the leather collar and a chocolate-colored cowboy hat. Mud crusted his boots. He had dirt on his cheek. And if he got any more handsome, she would die before she hit seventeen. She would simply die of it.

Tamara walked up to him as he was carrying a bale of straw and knocked on his shoulder like she was knocking on a door.

“Nobody’s home,” Levi called out before she could say a word.

“I would like to ride my horse right now, please and thank you.”

“Nope.”

“Nope? What do you mean nope?”

“I mean, nope, no, no way. You can’t ride your horse right now, please and thank you.” Levi walked away from her, straw bale in hand, as if that were the end of it.

Tamara chased after him and determinedly knocked on his shoulder again. He dropped the bale.

“Why can’t I ride today?”

“It’s been raining for days. It’s too wet.”

“It’s not raining now.” She tapped on the glass of the window. “Look—it’s dry. Dry, dry, dry.”

“What part of no do you not understand, Rotten? The N or the O?”

“You shouldn’t call me Rotten,” she said, hands on her hips in the hopes he’d notice she had them. “It’s not nice.”

“I’m not nice. And I wouldn’t call you Rotten if you weren’t so damn spoiled rotten, so whose fault is it really? And again—the answer is no—N and O, no. Even you can spell that.”

He might have been right about her being spoiled rotten, not that Tamara wanted to admit that. Most days he was the only person in the county—other than her mother—who had it in him to say no to her.

“Oh, I can spell. I can spell frontward and backward, and no spelled backward is on, as in I’m on the back of my horse and on the trail for a ride.”

“And on my last nerve,” Levi said. He took his hat off and brushed his sleeve over his forehead. She wondered sometimes if he did this sort of stuff just to torment her because he knew she had a crush on him—not that she did much to hide it. He was a first-class gold-medal tormentor, that Levi. He was twenty-eight and she was only sixteen as of midnight last night, which meant there was no way in hell Momma or Granddaddy would let her date him even if he was more handsome than the men on TV. He had curly black hair and a crinkle-eyed devilish smile he aimed at her often enough to get her hopes and her temperature up. He had a good tan, too, all the time, even in winter, making her wonder how he kept his tan so good even in February...and whether all of him was that tan. These were important questions to one Miss Tamara Belle Maddox.

And when he called her Rotten, it made her want to jump on top of him every time he did it.

“You know, today’s my birthday,” she said. “You have to be nice to me on my birthday.”

“I don’t have to do anything but die and pay taxes. Unless you’re the grim reaper or the IRS, you don’t get any of my attention today. Today is my day off. I’m only here because this is the only time the farrier could come and see to Danny Boy’s shoes.”

She stared at him, eye-to-eye. Or as close to eye-to-eye as she could get. She’d come in at five foot six this year and he had to be at least half a foot taller than her. Still, she did her level best to stare him down.

“Levi.”

“Yes, Rotten?”

“I am the grim reaper. Now let me go riding or I’m going to tell Momma I caught you engaged in unnatural acts with Miss Piggy.”

“You mean your momma’s horse or the pig on The Muppets?”

“Does it matter?”

“It matters a helluva lot to me if I’m engaging in unnatural acts with one of them. I need to know who I’m sending flowers to after.”

“You are the meanest man ever born,” she said, shaking her head. “Where’s the pitchfork?”

“You finally going to clean out Kermit’s stall without me having to tell you twenty thousand times?”

“No. I’m going to stab you with it so many times we can use you to drain noodles.”

“It’s on the wall where it always is. Now if you’ll excuse me, I have to do anything that involves not talking to you anymore.”

Levi stepped away, but she stepped in front of him.

“Levi...” she said, her voice cracking in her desperation. “Please let me go riding today. It’s my birthday and I’ll clean the stalls and it’s my birthday and I’ll do whatever you tell me to do and it’s my birthday and—”

He sighed—heavily—and lowered his chin to his chest.

“What crime did I commit in a past life that brought me to this point in my current incarnation?” he said with a heavy sigh.

“You’re talking weird again,” she said.

“Karma,” he said. “I’m talking about karma. Which you would know nothing about as you are obviously so young and so dumb and so naive that the only way to explain it is that this is your very first incarnation. You are a baby soul in this universe. Only cause for your soul to be so wet behind the ears.”

“You know you love me,” she said. “You know I’m your favorite.”

“I don’t even like you, Rotten. Not one bit.”

“Oh, you like me. You like me many bits.”

“Love you or hate you, you can’t go riding. I have spoken.”

“You have to let me go. You work for us. You have to do what I say.”

He stared her down and that stare felt like a rolling pin or worse—a steamroller. She gave him a steamroller back.

“You don’t sign my paychecks, Rotten. I work for your granddaddy, not you.”

“I wish you worked for me. I’d pay you to kiss me and fire you if you didn’t.”

“I realize I’m the last man who needs to be stereotyping anyone, but apparently everything I ever heard about redheads is true.”

“Levi.”

“What?”

“They’re fighting again.”

Levi gave her a tight-lipped look like he wanted to be nice to her but it went against his grain.

“What is it this time?” Levi asked.

“I don’t know. They won’t tell me. But I know Momma wants to move out and Granddaddy doesn’t want us to.”

“Didn’t y’all use to live in your own house?”

She nodded. “We did until Daddy died.”

“You want to move out?”

“I’d rather live in here in the stable than in any house when they’re fighting like this.”

“That bad?”

“Yeah,” she said, then she grinned at him. “Plus, you’re out here. I’d trade Granddaddy and Momma both for you.”

“Good God, go. Go away. Shoo. Ride your damn horse and leave me alone. But if Kermit gets a leg stuck in a mudhole and throws you and breaks your neck, don’t come crawling to me to fix it. Your head’ll have to hang there on your shoulders all lopsided.”

“Merci, mon capitan.” She grabbed him by the arms, kissed both his cheeks and saluted him like she was a junior officer and he her French captain.

“You are out of your damn mind,” he muttered as she raced to Kermit’s stall.

“Can’t hear you,” she sang out. “I’m riding in the wind with joy at my feet and freedom in my hair.”

Levi unlocked the door where he kept their saddles. They were too expensive, she knew, too tempting for thieves. Also, Levi knew if he didn’t lock them up, she’d steal them to go riding whenever she wanted, which wasn’t what she wanted, though she would protest otherwise if asked. Half the fun of going riding was bugging Levi until he let her go.

Once she’d saddled Kermit, she led him out to the riding trail that began at the end of the paddock. She hadn’t been too keen on the idea of moving in with her granddaddy after her father died. She’d loved their old house, a rambling brick Victorian in Old Louisville, but there wasn’t much horseback riding in the city. No horses meant no stables. No stables meant no grooms. No grooms meant no Levi. Oh, yes, she’d gotten used to living out here in the Maddox estate, Arden, with her granddaddy pretty quick after laying eyes on her grandfather’s groom. But more and more her mother and grandfather had been fighting their ugly whispering fights, and Tamara hadn’t been kidding when she’d said she’d rather live in the stables than the big house.

Once out in the cold air, Tamara decided maybe a shorter ride was a better ride. Muddy trails meant a slow pace and a nervous pony. Her ears burned with the cold and her nose dripped. She swiped at it with her sleeve and was glad Levi wasn’t around to see that unladylike maneuver. She and Kermit picked their way down the main path that led through a couple hundred acres of trees. Fall had stripped the leaves off the trees, but there was still something beautiful about the barren forest. Not barren at all despite appearances. Not barren, but only sleeping. She sensed the sap under the bark, and the wood drinking up all the water in the ground from the days and days of December rain they’d had. Even bare the trees seemed brutally alive to her. They were bursting to wake up and release the green in them, counting the seconds until spring when they could stretch and bloom and eat warm wet air like candy.

Tamara found her favorite rock, a big chuck of limestone she liked to lie on in better weather, and used it to dismount. After tying Kermit to a tree trunk, she squished her way through ankle-deep mud and muck to the edge of the river. It was high today, higher than she remembered ever seeing it, and darker, too. Faster. It smelled different, a thick, pungent odor like dead fish and dirty metal. It made her nose wrinkle. As the water tripped over the rocks, it turned white like ocean waves. She’d inherited ocean fever from her father, not that he’d ever admitted that was where he went on his business trips. He’d never had to tell her, though. She’d found the sand in his shoes. When she told him to take her with him next time, he’d winked at her like that had been his plan all along.

Instead, he’d shot himself in the head somewhere in South Carolina three years ago while on one of those business trips, and she still didn’t know which beach that sand had come from.

“Come back, Daddy,” she said to the river. This river met up with the Ohio, which met up with the Mississippi, which met up with the ocean. And water could turn to vapor and rise up into the sky. There was nowhere water couldn’t go. If she gave the water her message, maybe it could find her father. “I miss you. You were supposed to take me to the beach, remember? You were supposed to take me with you.”

She sent the same message once a week at least. So far no answer, but today maybe...maybe the river heard her. Maybe today the river would find Daddy.

Tamara returned to Kermit, rubbed his chilled flanks, kissed his velvet nose before mounting up to finish her ride. Without Kermit and Levi, she might very well go haywire in her grandfather’s house. Girls at school envied her the brick palace she lived in, but they didn’t know about the fights. They didn’t know about Momma’s rules. They didn’t know about Daddy and the cloud his death had lowered around Arden House, shrouding it so that screams became whispers and whispers became silence. Her mother and grandfather were keeping secrets from her, secrets that set them to fighting nearly every day, even on her birthday.

Even on her birthday.

The rain had returned by the time she made it back to the stables, her hands cramped in her gloves and her cheeks chapped raw from the cold wind. She unsaddled Kermit and brushed him down, showering him with all the pets and scratches any horse in the world would want. She left to fetch a fresh bale of straw for bedding and found Levi waiting for her in Kermit’s stall when she returned. He’d turned the heater on in the stables and had taken his coat off. In his long-sleeved flannel shirt and jeans he looked more handsome than he had even an hour earlier. An hour from now he’d look even more handsome than he did right this minute. She wasn’t sure how he accomplished this feat, but she was quite happy to observe it in action.

“Here.” Levi held out a small red box no bigger than a deck of cards.

“What’s this?” she asked, taking the box from him.

“Your birthday present.”

Tamara’s eyes widened.

“How did you know it was my birthday?”

“You said so about ten million times today.”

“You got this for me today? While I was riding?”

“Well...no.”

“Then you already knew it was my birthday. So you must have gotten it earlier. Unless you keep presents for me hidden around here all the time. You do, don’t you?”

“George told me he bought you a Triumph Spitfire for your sweet sixteen. I don’t give a damn it’s your birthday. I just wanted to borrow your car.”

“I’ll trade you the car for a kiss.”

“Forget it. I’m keeping your present.”

He reached for the box and Tamara yanked it away, nearly biting off her fingertips in her urgency to pull her gloves off her hands. They were shaking by the time she got the box lid open. One of the girls at school—Crissy, God help her with a name like that—said girls should always play it cool with guys, not act too eager. Well, Crissy had never been given a birthday present by the most handsome man in the entire world, and Tamara couldn’t play it cool if she were sitting in an igloo.

From a bed of yesterday’s newspaper, Tamara pulled out a little gold horse on a little gold chain.

“You like horses,” he said before she could say anything about it.

“I like you,” she said.

“An hour ago you were threatening to turn me into a spaghetti strainer.”

“I only threaten to turn people into strainers if I like them. Is this a bracelet?” The chain was only a few inches long.

“Necklace,” he said.

“If you put this short chain around my neck, I’ll choke to death.”

“Exactly.”

She glared at him.

“It’s an ankle bracelet, Rotten,” he said. “Unless you have really fat wrists, then it’s a regular old bracelet.”

“I don’t have fat wrists.”

“All I’m saying is if you did happen to have unusually fat wrists, it could be a bracelet.”

“I weigh one hundred pounds, Levi.” She draped the ankle bracelet around her wrist to show how loose it fit on her.

“One hundred pounds of wrist. I’m not saying it’s a normal place to carry extra weight, but it happens. Maybe you could do some wrist exercises or something...”

Tamara kissed him.

It wasn’t a cheek kiss this time. She wasn’t playing junior officer to his mon capitan. She kissed him like she meant it. Because she meant it. God Almighty, did she mean it.

Levi gripped her by the upper arms and pushed her back gently, but still, it was a definite move to put distance between them.

“Sorry,” she said, flushing slightly. “Got a little twitterpated there. You know, because I like horses.”

“You know you can’t go around kissing guys like that.”

“Like what?”

“Like me. You can’t go around kissing guys like me.”

“Why not?”

“You’re sixteen, Tamara.”

“I was fifteen yesterday.”

“That’s the opposite thing of what you should say.”

“What should I say?”

“Maybe that you won’t kiss me on the mouth again. Or anywhere else. I think that would be a good start.”

He crossed his arms over his chest.

“But it’s my birthday.”

“You don’t get to do everything you want to do just because it’s your birthday.” He sounded wildly exasperated with her, and wildly exasperated Levi was her favorite version of Levi. “Try telling a police officer you’re allowed to kill anybody and everybody you want just because it’s your birthday. That duck won’t fly.”

“I didn’t kill anyone. I kissed. Two S’s, not two L’s. Makes all the difference.”

“Rotten, I’m way too old for you. I work for your granddaddy. He’d have my hide if he caught me messing around with you.”

“I want a kiss, Levi, not a marriage proposal. I’ve never been kissed before. Not really. And that didn’t count because you didn’t know it was happening.”

“I think I knew. Parts of me sure did.”

She bounced up and down in her boots.

“Just one? Please? A real kiss?”

“What do you consider a real kiss?” he asked.

She shrugged her shoulders, shook her head. “I don’t know. Like the way they kiss on The Young and the Restless?”

“Which one am I? The young or the restless?”

“You’re the restless, obviously,” she said. “Because you’re so so so old, and I’m so so so young.”

“Will it shut you up if I kiss you?”

“Can’t talk with a tongue in my mouth, right?”

He took the box from her hand and tossed it on the pile of hay. He took her hand and pulled her flush against his body.

“Finally,” he said, smiling down at her. “Now we have a persuasive argument.”

4 (#ulink_0f48a72b-233c-55ab-ac8c-9b60e68d2f1f)

Tamara hadn’t expected him to go through with it. She’d only expected she would tease him and beg him to do it until he kicked her giggling and pouting spoiled rotten self out of the barn. Making him mad was the next best thing to making him laugh. When he actually took her in his arms, she froze in surprise. He didn’t kiss her—he did something better and worse at the same time.

Levi pushed her up against the rough wood of Kermit’s stall wall and held her there with his entire body.

“Your grandfather pays me to take care of his horses,” Levi said. “I am not paid to indulge you.”

“Then do it for free.”

Levi gave her a flat hard stare that scared her. Everything scared her right now. Being in such close quarters revealed the disparity in their sizes. Her shoulders spanned half his width. He stood a head taller. She could push against him with everything she had in her and she wouldn’t be able to budge the solid pillar of his body that held her pinned in place.

Oh, but she didn’t want to push against him. That was, in fact, the very last thing she wanted to do right now.

A teardrop of rainwater slid from Tamara’s temple down her face. Levi pressed his lips to that drop. They warmed her cold skin, and she’d never felt anything like that in her life, never felt something so sensual and threatening all at once. She closed her eyes and prayed for more rain, so much rain it would trap them in the stable. So much rain it would form a moat to keep the world out. So much rain everyone on earth would drown in it but her and Levi.

“Levi.” She pushed her hips against his. He had something she needed and her body had to tell him that.

“You are playing with fire, little girl,” Levi said into her ear.

“I’m not a little girl anymore,” she said, looking up at him. It was a brash thing to say, but it had to be said. Her voice quavered as she spoke the words. Tamara studied his face. She’d never seen him this close-up, inches away, close enough to smell him, close enough to see the freckle on his bottom lip. She could have counted his eyelashes.

Levi pushed his hips back into hers, and she felt something hard against her, something that demanded her attention.

Oh, dear. She had made a terrible miscalculation. Levi wasn’t a boy. Levi was a man. An adult man twelve years older than her. Older, wiser and so much bigger than she was. She really ought to stop him. She really ought to. Yes, she should do that.

“I love you,” Tamara said instead.

“Do you?” Levi asked, barely batting an eyelash at her declaration, which made her madder than being pinned to the wall. How dare he not take her seriously when she told him she was in love with him.

“I do. I swear I do.”

“You don’t even know who I am. You don’t know who you think you love.”

“I don’t care. I know I love you. You’re perfect and handsome and I think about you all the time and I want you all the time and I love you.”

“All the time?”

She nodded. “All the time.”

She pressed her mouth hard against his, kissing him like she had a loaded gun pointed at her head and only kissing could save her life. It felt so good she sighed, and when the sigh parted her lips, Levi’s tongue slipped between her teeth. She’d been kidding about the tongue in her mouth, but Levi wasn’t laughing. Not anymore and not about anything. Levi dug a hand into the back of her braid and pushed her mouth harder against his. His tongue tasted so good she wanted to suck on it. When she did, he made a noise in the back of his throat, a dirty noise that made her want to make him do it again.

Levi pulled back from the kiss like he was ripping off a Band-Aid. And yet she remained pinned in place. He had her pushed so hard against the wall she could lift her boots off the ground and not fall.

“Do you have any idea how many girls I’ve fucked in my life?” he asked her. “Or do you think my entire life is brushing your grandfather’s horses and putting up with you?”

She didn’t know how to answer that. She panted and shook her head. “I don’t know.”

“You want to know?” he asked. His voice was menacing now, not seductive, and yet she felt utterly seduced. She didn’t want to be anywhere but here against this wall. “You want to know how many girls I’ve fucked?”

“Yes,” she said because she thought that was what he wanted to hear.

“Every girl I’ve ever wanted to fuck, that’s how many,” he said, and she believed him. Maybe yesterday she wouldn’t have believed that. Yesterday he’d have been just the horse groom with the pretty eyes and sexy smile. Today he was a man with muscles and a body and hands big enough to span her waist like they were doing now. “Every girl I’ve ever wanted to fuck...minus one.”

Tamara inhaled sharply.

His hands slid from her waist to her thighs. He lifted her off the straw-covered ground and wrapped her legs around him. She clung to him as if for life, hands grasping his shoulders, her boots wound together at his lower back and locked tight. The seam along the crotch of her jodhpurs rubbed against a soft and swollen part of her, and every time Levi pushed closer, she flinched with pleasure. Her head fell back when he did it again. When she raised her head, she saw him looking into her shirt. She had larger breasts than any other girl her age at her school, not huge, but full. She couldn’t hide them and neither could her bra. Tamara took her hand off his shoulder long enough to unbutton her shirt to the center of her chest. He wanted to look at her and she wanted him to see her. He lowered his head and kissed the top of her breast where it spilled out over the lace-trim edge of her white bra. Against her neck she felt his hair and loved, loved, loved the soft tickle of it on her skin.

“You like this?” he asked, grinding against her again, flint against tinder.

“Yes.” She could scarcely catch a breath with his chest pressed so hard against hers.

“You’re not scared?”

She shook her head no.

“You a virgin?” he asked.

“I told you, I’ve never even had a real kiss.”

“You can fuck without kissing.”

“That had never occurred to me.”

“I don’t recommend it,” he said. “I like to do both at the same time.”

“That’s quite...”

“Quite what?” he asked.

“That’s quite a thought,” she said. “I like that thought.”

“I like your thoughts. I’d like to give you more of them.” Again Levi pushed against that raw sensitive place between her legs and she let out a little cry that he silenced with a kiss. At first she froze in fear, but she thawed almost instantly. Then it went beyond thawing and into an immediate burn.

His mouth moved over hers and she sighed with unfathomable pleasure.

With her eyes closed she could do nothing but taste him and smell him and feel him against her, and it was even better than seeing him. He tasted like he’d taken a nip or two of her granddaddy’s Red Thread bourbon. A good taste like apples and licorice, but hot, not on the rocks. His lips were soft, too, but insistent, like he was trying to win an argument by kissing her. She happily conceded defeat. Oh, and he smelled perfect to her. Sweat and aftershave and the leather and oil of horse tack. He smelled like a man who worked hard, even on Sundays. Sundays should be a day of rest, a day to spend in bed kissing. Kissing, and more than kissing...

It was the strangest thing, being kissed. His mouth was on her mouth. His tongue was between her teeth and nowhere else. His hands were on her hips holding her up. And yet she felt the kiss in all sorts of places she didn’t expect. She felt it in her stomach, down deep. She felt it inside her pelvis and all along her thighs. She felt it in her breasts, which were pressed against his chest. A layer of shirt and bra separated her body from his and yet her nipples were hard and wanted touching and sucking. She was almost out of her mind enough to ask him to do it.

Tamara reached up and ran her hand through his hair. He might not like that, but she wanted to touch his hair, had wanted to touch it since she first saw it two years ago when she and her mother moved into the big house at Arden. Now that his mouth was occupied kissing her, she had the chance to do anything she wanted to do without hearing a protest song about it. She ran her fingers through his hair, loving its soft, thick texture. There was so much more of him she wanted to touch, too. She stroked his cheek, his strong neck, his shoulders. She’d give anything to get his clothes off and touch every part of him that touched her.

Tamara knew about sex from school, about things she’d heard from girls who’d gone all the way and had lived to tell the tale. But no one had ever told her what to do in this situation, when she felt an erection outside her clothes and wanted it inside her body. She didn’t want to be a virgin anymore, and she wanted him to be the one to have it for what it was worth. To have her.

“Please do it, Levi...” she said into his ear.

“Only because it’s your birthday.” Levi cupped her breast and squeezed it and that was it—it was happening. Not even a stampede of the four horsemen could stop them now. He pushed the bra cup down, baring her nipple. He pinched it and she died. He lowered his mouth and licked it and she died again. Then he covered her breast with his hot mouth and sucked it and she died and was born again.

“What in God’s name do you two think you’re doing?”

Levi let Tamara down to the floor so fast her knees nearly gave out under her. The horse anklet she’d draped over her wrist fell to the ground and into the hay. She yanked her coat tight around her chest and looked at Levi, but he wasn’t looking back at her. He stared straight ahead.

There were three people in the universe and all its dimensions whom Tamara Maddox was afraid of. God and the Devil were two of the three and even God and the Devil ranked a distant second behind the one woman who could scare even Tamara Belle Maddox—she who got what she wanted when she wanted it because she wanted it—and that was the woman standing in the stables staring black ice at both her and Levi.

“Nothing, Momma.”

5 (#ulink_be8a9d89-7428-5372-aebd-4a0834fac5dc)

“Nothing? That was not nothing.”

Her mother’s voice hit her like a bucket of cold water. Levi let her go and turned and stood in front of her, giving her a chance to straighten her clothes.

“We were just kissing, Momma,” Tamara said, moving to Levi’s side. “It’s my birthday.”

“Mrs. Maddox, I swear it was a quick little birthday kiss,” Levi said. “Nothing more.”

“You are dead, boy,” her mother said. Her mother had never been fond of Granddaddy’s stable hand, but right now she wished him dead and buried, and she looked perfectly willing to do it herself.

Levi’s chin rose and his jaw set.

“What did you call me?” he asked.

“You heard me, boy. And if you ever lay a hand on my daughter again, what I call you will be the least of your problems.” She grabbed Tamara by the arm and dragged her from the stables.

“Momma, stop—”

“Not a word,” she said. “You wait until I tell your granddaddy about this.”

“What’s he gonna care?”

Her mother had hellfire in her eyes and her face was set in granite. She looked as scared as she did angry.

“He’ll care.”

Her mother marched her from the stables, up the path and through the back door of the big house. She was so angry her hair vibrated like jelly, and considering the amount of White Rain she put in that blond aura every morning, any movement was a bad sign.

Well, this was perfect, wasn’t it? Couldn’t Tamara have one single day without her mother blowing up at her about something pointless? Yesterday she’d blown her top over Tamara saying “shit” at the dinner table. And Friday when she’d come home from her school in Louisville for Christmas break, Tamara had gotten screamed at for hauling nothing but dirty clothes back with her. Why her mother cared, Tamara didn’t know. Not like Momma did any of the laundry. Cora, the housekeeper, did all the work. Her mother didn’t work. Her mother never worked. Her mother might not know how to spell work if they were playing Scrabble and the only tiles she had were a W, an O, an R and a K. She’d probably say crow started with a K.

Inside the kitchen Tamara kicked off her muddy boots while her mother watched her. Tamara did her level best to ignore her, a feat she’d nearly perfected in the past three years since Daddy died and “angry” had become her mother’s default expression, her go-to response to anything. In the beginning Tamara had taken each little slight, each cold reply, each insult, like a brick to her face. But after a few months Tamara had put those bricks to good use and built a wall—high, deep and wide—between her and her mother until she had a fortress of her own and her mother seemed like nothing so much as a villager throwing pebbles at the queen’s castle. Of course, even when her father had been alive, her mother hadn’t been much of a treat to live with. She and Daddy had whispered jokes to each other about her mother when she got in those moods. Daddy liked to say the Devil owed him a debt and Momma was how Satan paid him back.

Once Tamara’s boots were off, her mother grabbed her by the arm and dragged her down the hallway. Arden was a massive home, a hundred-year-old Georgian-revival brick box. Every room a different color like the White House. Following her mother, Tamara passed her pink princess bedroom and the blue billiard room and the green dining room all the way to the red room on the right—her granddaddy’s study. Upstairs her granddaddy had his office and for the life of her she couldn’t figure out the difference between an office and a study except one had a desk and the other one didn’t.

Inside his study her grandfather sat on a red-and-gold armchair, holding a tumbler of bourbon—probably a bourbon sour from the looks of it—in one hand and a newspaper in the other.

“I need to discuss something with you,” her mother said.

“You always do, Virginia,” Granddaddy said, turning a page in the newspaper without looking up.

“Granddaddy, Momma—” Tamara began, but her mother cut her off.

“You get to your room right now, and don’t you dare step foot out of it until I tell you.”

“What’s going on here?” Now Granddaddy was paying attention. He laid the newspaper on his lap in a neat heap of pages. In the overcast afternoon light he didn’t look much more than fifty years old, although he was well over sixty. He had a full head of hair and a face that reminded people of Lee Majors. Women called him the Six-Million-Dollar Man behind his back because they said that was probably how much money he kept in his wallet. Even sitting in his chair he looked big and strong and in control—the opposite of her twig-thin angry little mother.

“I caught your stable boy kissing my daughter,” her mother said.

“Levi? Kissing Tamara?”

“I asked him to, since it’s my birthday,” Tamara said quickly. “That’s all. Nothing else happened.”

“And this is worth my time?” Her grandfather addressed the question to her mother, not her.

“It was more than a kiss. That boy was all over her.”

“It was just a kiss,” Tamara said, yelling the words, overenunciating them like her mother was both slow and partially deaf.

“It was Levi Shelby, are you hearing me?” Her mother outyelled her. “Levi Shelby. I told you and told you not to have that boy around here. I told you and you didn’t listen and you still aren’t listening and you’re gonna pay a big price for not listening to me someday.”

Her granddaddy took a big old inhale and let out a big old exhale.

“I’m listening to you, Virginia.”

“So what are you going to do about it?”

“Nothing,” Tamara said. “There’s nothing either of you have to do about it. It’s my birthday. I asked Levi to kiss me. That’s all that happened.”

“Go to your room right this second,” her mother ordered.

“But—”

“Go on, baby,” Granddaddy said, waving his newspaper like he was shooing a dog from the room.

“Go.” Her mother pointed a long white finger tipped in a long red fingernail at the door. Tamara left. She shut the door behind her and trudged down the hall, but slowly, slow enough she could hear them still talking. Her mother said, “This is all your fault,” which was a classic Momma thing to say. How was Levi kissing her or her kissing Levi her grandfather’s fault?

Tamara went into her bedroom and sat on the bed, waiting and trying not to cry. She’d been given the only downstairs bedroom when they’d moved in and as a “treat” to her they’d had it painted pink, since that was a color sure to please a girl. It didn’t please her. It was Pepto-Bismol pink and it caused her more stomachaches than it cured.

Finally her bedroom door swung open and slammed shut. Her mother stood before her, hands on hips. Tamara stared at the floor.

“So...how long has this been going on?” she asked.

“What’s going on?”

“Answer me,” her mother said.

“Nothing’s going on. I told you, I asked Levi to kiss me because it’s my birthday. He did. That’s all.”

“Did he touch you?”

“Well, his lips touched me.”

“Did he touch you under your clothes?”

“No, Momma.” Tamara groaned and rolled her eyes. “We kissed. That’s all. I’m sixteen. Am I not allowed to kiss boys?”

“You aren’t allowed to do anything. Nothing. Nothing without my permission or your granddaddy’s.”

“Fine. Get Granddaddy in here. We’ll ask him if I’m allowed to kiss a boy on my birthday.”

“You can ask him about Levi Shelby, but you’re not gonna like his answer.”

Her mother stood with her arms crossed, her high-heeled brown leather boot tapping on the hardwood floor. Once, Virginia Maddox had been a real beauty. Tamara had seen the pictures. But she wore too much makeup and dyed her Farrah Fawcett hair until it was dry and cracking. Most days she looked well-put-together, but on days like this Tamara could see the seams showing.

“Tamara, I’m going to tell you something you’re not going to like to hear, but you better hear it.”

“What?”

“You have one role to play in this family,” she said. “Only one. Your uncle Eric is dead. And your daddy, Nash, is dead. You are the only Maddox left after your grandfather’s gone. I know you think this makes you special. And I know you think this means you can get away with murder if you feel like it. But it doesn’t. It means the opposite. It means you don’t get to do anything and everything you want to do. It means you have to fill your role because there’s no one else to do the job you need to do. And you better believe if you don’t shape up and grow up and do what your grandfather tells you to do, you will end up with nothing. I will not let you screw this up, not after all I’ve put up with.”

“I’m only sixteen. What am I supposed to do?”

“You know. You’ve always known.”

Tamara sighed. “I know. I have to get married. I have to have babies.” She knew this. She had known this for years now. Two years ago she wanted to get a Dorothy Hamill haircut and her mother had told her no way—girls who wanted husbands did not have short hair. “I have to keep Red Thread alive, blah blah blah.”

“Yes, you do. And you have no choice in the matter.”

“I don’t have a choice in any matter. You don’t give me a choice. Granddaddy doesn’t give me a choice. I might as well be in prison for all the choices I have.”

“You want a choice?”

“I’d love a choice,” Tamara said.

“Fine. Here’s your choice. You can pick between Kermit or Levi. How’s that for a choice?”

“What do you mean pick between them?”

“I mean, I’m going to fire Levi or I’m going to sell Kermit to the glue factory. So what’s it going to be?”

“You can’t do that. You can’t make me fire Levi or kill my horse. You can’t...” Tamara’s voice broke on the words.

“Oh, I can. I can and I will and not even your granddaddy will try to stop me. And you know what? It’s for your own good and you don’t even know it.”

“It’s not for my own good. It’s for your own good.”

“Pick, princess. You wanted a choice. I’m giving you a choice.”

“I’m not going to choose between Levi and Kermit. I will not.” Tamara stood up and crossed her arms over her chest. “I absolutely will not do that.”

“Both, then. Levi gets fired and I sell Kermit. Hell, maybe I’ll take your granddaddy’s revolver out of his desk and put that damn horse down right now.”

“Momma—” Tamara choked on her tears. She took a step forward, arms out, beseeching her mother to relent.

“Oh, don’t even try that baby-girl routine on me,” her mother said, shaking her head so hard her dangling gold-and-diamond earrings clinked like tiny bells. “You won’t talk me out of this. You don’t even know what you’re getting into with Levi. So decide and decide right now. You got three seconds to tell me—Kermit or Levi. One...”

“But Daddy gave me Kermit.”

“Your daddy gave himself a bullet in the brain, so your daddy don’t get a say in this. Two...”

“Momma, no. Please don’t make me.”

“Kermit or Levi. Tell me now.”

“You,” Tamara said. “You go take Granddaddy’s revolver and you put yourself down, and me and Kermit and Levi will ride off into the sunset, you nasty old bitch.”

Her mother slapped her. Hard. So hard Tamara gasped and nearly fell on her side.