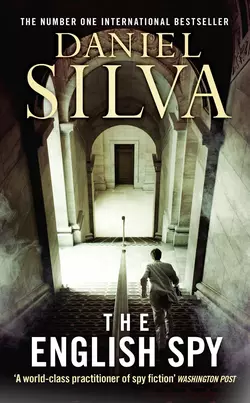

The English Spy

Daniel Silva

No. 1 New York Times bestselling author Daniel Silva delivers another stunning thriller in his latest action-packed tale of high stakes international intrigue featuring the inimitable Gabriel Allon.She is an iconic member of the British Royal Family, beloved for her beauty and charitable works, resented by her former husband and his mother, the Queen of England. When a bomb explodes aboard her holiday yacht, British intelligence turns to one man to track down herkiller: legendary spy and assassin Gabriel Allon.Gabriel’s target is Eamon Quinn, a master bomb maker and mercenary of death who sells his services to the highest bidder. Fortunately Gabriel does not pursue him alone; at his side is Christopher Keller, a British commando turned professional assassin who knows Quinn’s murderous handiwork all too well.And though Gabriel does not realize it, he is stalking an old enemy—a cabal of evil that wants nothing more than to see him dead. Gabriel will find it necessary to oblige them, for when a man is out for vengeance, death has its distinct advantages….

Daniel Silva

The English Spy

Copyright (#u4b2a7299-a82f-5ca2-85b7-eb236d09bf93)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Copyright © Daniel Silva 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cover photographs © Peter Bagi / Gallery Stock (stairwell); Henry Steadman (figure).

Map designed by Leah Nick Springer

Flag illustration © charnsitr/Shutterstock, Inc.

Daniel Silva asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007552337

Ebook Edition © JULY 2015 ISBN: 9780007552320

Version: 2015-11-17

Dedication (#u4b2a7299-a82f-5ca2-85b7-eb236d09bf93)

For Betsy and Andy Lack.

And, as always, for my wife, Jamie,

and my children, Lily and Nicholas.

Epigraph (#u4b2a7299-a82f-5ca2-85b7-eb236d09bf93)

When a man rubs out a pencil-mark, he should be careful to see that the line is quite obliterated. For if a secret is to be kept, no precautions are too great.

— GRAHAM GREENE, THE MINISTRY OF FEAR

No more tears now; I will think upon revenge.

— MARY, QUEEN OF SCOTS

Table of Contents

Cover (#ua1c69d8a-051f-5dc0-8feb-cccd5de15ec3)

Title Page (#u271fb7a4-0e9e-5801-b107-a38e8922a2b1)

Copyright (#u88e56b72-88d3-52ae-bc7f-16b383c366b2)

Dedication (#u054fbe0d-8289-5318-bb6a-ee89d3fb2cb6)

Epigraph (#u304f12c0-b7c2-56bc-b23f-4d45b569ec8c)

Map (#u225e85ba-49ec-5a04-9a52-c95fce6e68e8)

Part One: Death of a Princess (#u66a2192c-01de-593d-b355-3d1b517f89bc)

Chapter 1: Gustavia, Saint Barthélemy (#u52482dae-5560-50cf-a5cc-6098d3c999cd)

Chapter 2: Off the Leeward Islands (#u5a8522cd-4fe7-5057-b565-b0554a2c655e)

Chapter 3: The Caribbean–London (#ucd1c798d-daef-559f-901b-ad93c56192da)

Chapter 4: Vauxhall Cross, London (#ue9be81eb-6abd-5fed-a696-965ef46c34a1)

Chapter 5: Fiumicino Airport, Rome (#ua2aa2e5d-2ca3-5d50-9927-b581cedb89b4)

Chapter 6: Via Gregoriana, Rome (#u6ecfb9fe-ae7c-5732-9bc2-a36e785846fe)

Chapter 7: Via Gregoriana, Rome (#uf260c59b-e1a0-5290-a8aa-f198e0393ff5)

Chapter 8: Via Gregoriana, Rome (#ue31e7bdc-e61e-5584-81a2-accaf432e83d)

Chapter 9: Berlin–Corsica (#u004ac6f4-bd27-5aee-9e1e-f816c137811c)

Chapter 10: Corsica (#u613a3705-47ec-5ca8-8469-d5ccb06bb38f)

Chapter 11: Corsica (#u253afd0e-b333-587c-a19b-fa58ec7e1824)

Chapter 12: Dublin (#u1f3e2a84-a281-51a1-bc36-e733926e2b5c)

Chapter 13: Ballyfermot, Dublin (#ud6cc0604-5a96-5a24-86d9-d807884b50cd)

Chapter 14: Clifden, County Galway (#u82c450cf-9631-5287-bdb6-9877b6e24bbf)

Chapter 15: Thames House, London (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16: Clifden, County Galway (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17: Clifden, County Galway (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18: Omagh, Northern Ireland (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19: Great Victoria Street, Belfast (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20: The Ardoyne, West Belfast (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21: The Ardoyne, West Belfast (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22: Warring Street, Belfast (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23: Belfast–Lisbon (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24: Bairro Alto, Lisbon (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25: Bairro Alto, Lisbon (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26: Heathrow Airport, London (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27: Brompton Road, London (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two: Death of a Spy (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28: London (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29: Dartmoor, Devon (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30: Wormwood Cottage, Dartmoor (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31: Wormwood Cottage, Dartmoor (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32: Wormwood Cottage, Dartmoor (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33: Gunwalloe Cove, Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34: Gunwalloe Cove, Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35: Gunwalloe Cove, Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36: Highgate, London (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37: Wormwood Cottage, Dartmoor (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38: London–the Kremlin (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39: London–Vienna (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40: Intercontinental Hotel, Vienna (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41: Lower Austria (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42: Lower Austria (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43: Lower Austria (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44: Sparrow Hills, Moscow (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45: Copenhagen, Denmark (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46: Vienna (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47: Vienna (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48: Vienna (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49: Rotterdam, the Netherlands (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50: Vienna–Hamburg (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51: Piccadilly, London (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 52: Fleetwood, England (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 53: Thames House, London (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 54: Lord Street, Fleetwood (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 55: Hamburg (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 56: Neustadt, Hamburg (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 57: Hamburg (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 58: Hamburg (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 59: Northern Germany (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: Bandit Country (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 60: Vauxhall Cross, London (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 61: Bristol, England (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 62: 10 Downing Street (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 63: Cornwall, England (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 64: Guy’s Hospital, London (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 65: Gunwalloe Cove, Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 66: Thames House, London (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 67: West Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 68: Gunwalloe Cove, Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 69: Gunwalloe Cove, Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 70: County Down, Northern Ireland (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 71: The Ardoyne, West Belfast (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 72: Crossmaglen, County Armagh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 73: The Ardoyne, West Belfast (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 74: Crossmaglen, County Armagh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 75: Union Street, Belfast (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 76: Creggan Forest, County Antrim (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 77: Randalstown, County Antrim (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 78: Crossmaglen, South Armagh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 79: Crossmaglen, South Armagh (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Four: Home (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 80: South Armagh–London (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 81: Victoria Road, South Kensington (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 82: Narkiss Street, Jerusalem (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 83: Narkiss Street, Jerusalem (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 84: Mount Herzl, Jerusalem (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 85: Buenos Aires (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading ... (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also Written by Daniel Silva (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART ONE (#u4b2a7299-a82f-5ca2-85b7-eb236d09bf93)

DEATH OF A PRINCESS (#u4b2a7299-a82f-5ca2-85b7-eb236d09bf93)

1 (#u4b2a7299-a82f-5ca2-85b7-eb236d09bf93)

GUSTAVIA, SAINT BARTHÉLEMY (#u4b2a7299-a82f-5ca2-85b7-eb236d09bf93)

NONE OF IT WOULD HAVE happened if Spider Barnes hadn’t tied one on at Eddy’s two nights before the Aurora was due to set sail. Spider was regarded as the finest waterborne chef in the entire Caribbean, irascible but altogether irreplaceable, a mad genius in a starched white jacket and apron. Spider, you see, was classically trained. Spider had done a stint in Paris. Spider had done London. Spider had done New York, San Francisco, and an unhappy layover in Miami before leaving the restaurant biz for good and taking to the freedom of the sea. He worked the big charters now, the kind of boats the film stars, rappers, moguls, and poseurs rented whenever they wanted to impress. And when Spider wasn’t behind his stove, he was invariably propped atop one of the better bar stools on dry land. Eddy’s was in his top five in the Caribbean Basin, perhaps his top five worldwide. He started at seven o’clock that evening with a few beers, blew a reefer in the shadowed garden at nine, and at ten was contemplating his first glass of vanilla rum. All seemed right with the world. Spider Barnes was buzzed and in paradise.

But then he spotted Veronica, and the evening took a dangerous turn. She was new to the island, a lost girl, a European of uncertain provenance who served drinks to day-trippers at the dive bar next door. She was pretty, though—pretty as a floral garnish, Spider remarked to his nameless drinking companion—and he lost his heart to her in ten seconds flat. He proposed marriage, which was Spider’s favorite approach, and when she turned him down he suggested a roll in the sheets instead. Somehow it worked, and the two were seen teetering into a torrential downpour at midnight. And that was the last time anyone laid eyes on him, at 12:03 a.m. on a wet night in Gustavia, soaked to the skin, drunk and in love yet again.

The captain of the Aurora, a 154-foot luxury motor yacht based out of Nassau, was a man called Ogilvy—Reginald Ogilvy, ex–Royal Navy, a benevolent dictator who slept with a copy of the rulebook on his bedside table, along with his grandfather’s King James Bible. He had never cared for Spider Barnes, never less so than at nine the next morning when Spider failed to appear at the regular meeting of the crew and cabin staff. It was no ordinary meeting, for the Aurora was being made ready for a very important guest. Only Ogilvy knew her identity. He also knew that her party would include a team of security men and that she was demanding, to say the least, which explained why he was alarmed by the absence of his renowned chef.

Ogilvy informed the Gustavia harbormaster of the situation, and the harbormaster duly informed the local gendarmerie. A pair of officers knocked on the door of Veronica’s little hillside cottage, but there was no sign of her either. Next they undertook a search of the various spots on the island where the drunken and brokenhearted typically washed ashore after a night of debauchery. A red-faced Swede at Le Select claimed to have bought Spider a Heineken that very morning. Someone else said he saw him stalking the beach at Colombier, and there was a report, never confirmed, of an inconsolable creature baying at the moon in the wilds of Toiny.

The gendarmes faithfully followed each lead. Then they scoured the island from north to south, stem to stern, all to no avail. A few minutes after sundown, Reginald Ogilvy informed the crew of the Aurora that Spider Barnes had vanished and that a suitable replacement would have to be found in short order. The crew fanned out across the island, from the waterside eateries of Gustavia to the beach shacks of the Grand Cul-de-Sac. And by nine that evening, in the unlikeliest of places, they had found their man.

He had arrived on the island at the height of hurricane season and settled into the clapboard cottage at the far end of the beach at Lorient. He had no possessions other than a canvas duffel bag, a stack of well-read books, a shortwave radio, and a rattletrap motor scooter that he’d acquired in Gustavia for a few grimy banknotes and a smile. The books were thick, weighty, and learned; the radio was of a quality rarely seen any longer. Late at night, when he sat on his sagging veranda reading by the light of his battery-powered lamp, the sound of music floated above the rustle of the palm fronds and the gentle slap and recession of the surf. Jazz and classical, mainly, sometimes a bit of reggae from the stations across the water. At the top of every hour he would lower his book and listen intently to the news on the BBC. Then, when the bulletin was over, he would search the airwaves for something to his liking, and the palm trees and the sea would once again dance to the rhythm of his music.

At first, it was unclear as to whether he was vacationing, passing through, hiding out, or planning to make the island his permanent address. Money seemed not to be an issue. In the morning, when he dropped by the boulangerie for his bread and coffee, he always tipped the girls generously. And in the afternoon, when he stopped at the little market near the cemetery for his German beer and American cigarettes, he never bothered to collect the loose change that came rattling out of the automatic dispenser. His French was reasonable but tinged with an accent no one could quite place. His Spanish, which he spoke to the Dominican who worked the counter at JoJo Burger, was much better, but still there was that accent. The girls at the boulangerie decided he was an Australian, but the boys at JoJo Burger reckoned he was an Afrikaner. They were all over the Caribbean, the Afrikaners. Decent folk for the most part, but a few of them had business interests that were less than legal.

His days, while shapeless, seemed not entirely without purpose. He took his breakfast at the boulangerie, he stopped by the newsstand in Saint-Jean to collect a stack of day-old English and American papers, he did his rigorous exercises on the beach, he read his dense volumes of literature and history with a bucket hat pulled low over his eyes. And once he rented a whaler and spent the afternoon snorkeling on the islet of Tortu. But his idleness appeared forced rather than voluntary. He seemed like a wounded soldier longing to return to the battlefield, an exile dreaming of his lost homeland, wherever that homeland might be.

According to Jean-Marc, a customs officer at the airport, he had arrived on a flight from Guadeloupe in possession of a valid Venezuelan passport bearing the peculiar name Colin Hernandez. It seemed he was the product of a brief marriage between an Anglo-Irish mother and a Spanish father. The mother had fancied herself a poet; the father had done something shady with money. Colin had loathed the old man, but he spoke of the mother as though canonization were a mere formality. He carried her photograph in his billfold. The towheaded boy on her lap didn’t look much like Colin, but time was like that.

The passport listed his age at thirty-eight, which seemed about right, and his occupation as “businessman,” which could mean just about anything. The girls from the boulangerie reckoned he was a writer in search of inspiration. How else to explain the fact that he was almost never without a book? But the girls from the market conjured up a wild theory, wholly unsupported, that he had murdered a man on Guadeloupe and was hiding out on Saint Barthélemy until the storm had passed. The Dominican from JoJo Burger, who was in hiding himself, found the hypothesis laughable. Colin Hernandez, he declared, was just another shiftless layabout living off the trust fund of a father he hated. He would stay until he grew bored, or until his finances grew thin. Then he would fly off to somewhere else, and within a day or two they would struggle to recall his name.

Finally, a month to the day after his arrival, there was a slight change in his routine. After taking his lunch at JoJo Burger, he went to the hair salon in Saint-Jean, and when he emerged his shaggy black mane was shorn, sculpted, and lustrously oiled. Next morning, when he appeared at the boulangerie, he was freshly shaved and dressed in khaki trousers and a crisp white shirt. He had his usual breakfast—a large bowl of café crème and a loaf of coarse country bread—and lingered over the previous day’s London Times. Then, instead of returning to his cottage, he mounted his motor scooter and sped into Gustavia. And by noon that day, it was finally clear why the man called Colin Hernandez had come to Saint Barthélemy.

He went first to the stately old Hotel Carl Gustaf, but the head chef, after learning he had no formal training, refused to grant him an interview. The owners of Maya’s turned him politely away, as did the management of the Wall House, Ocean, and La Cantina. He tried La Plage, but La Plage wasn’t interested. Neither were the Eden Rock, the Guanahani, La Crêperie, Le Jardin, or Le Grain de Sel, the lonely outpost overlooking the salt marshes of Saline. Even La Gloriette, founded by a political exile, wanted nothing to do with him.

Undeterred, he tried his luck at the undiscovered gems of the island: the airport snack bar, the Creole joint across the street, the little pizza-and-panini hut in the parking lot of L’Oasis supermarket. And it was there fortune finally smiled upon him, for he learned that the chef at Le Piment had stormed off the job after a long-simmering dispute over hours and salary. By four o’clock that afternoon, after demonstrating his skills in Le Piment’s birdhouse of a kitchen, he was gainfully employed. He worked his first shift that same evening. The reviews were universally glowing.

In fact, it did not take long for word of his culinary prowess to make its way round the little island. Le Piment, once the province of locals and habitués, was soon overflowing with a newfound clientele, all of whom sang the praises of the mysterious new chef with the peculiar Anglo-Spanish name. The Carl Gustaf tried to poach him, as did the Eden Rock, the Guanahani, and La Plage, all without success. Therefore, Reginald Ogilvy, captain of the Aurora, was in a pessimistic mood when he appeared at Le Piment without a reservation the night after the disappearance of Spider Barnes. He was forced to cool his heels for thirty minutes at the bar before finally being granted a table. He ordered three appetizers and three entrées. Then, after sampling each, he requested a brief word with the chef. Ten minutes elapsed before his wish was granted.

“Hungry?” asked the man called Colin Hernandez, looking down at the plates of food.

“Not really.”

“So why are you here?”

“I wanted to see if you were as good as everyone seems to think you are.”

Ogilvy extended his hand and introduced himself—rank and name, followed by the name of his boat. The man called Colin Hernandez raised an eyebrow quizzically.

“The Aurora is Spider Barnes’s boat, isn’t it?”

“You know Spider?”

“I think I had a drink with him once.”

“You weren’t alone.”

Ogilvy took stock of the figure standing before him. He was compact, hard, formidable. To the Englishman’s sharp eye, he seemed like a man who had sailed in rough seas. His brow was dark and thick; his jaw was sturdy and resolute. It was a face, thought Ogilvy, that had been built to take a punch.

“You’re Venezuelan,” he said.

“Says who?”

“Says everyone who refused to hire you when you were looking for a job.”

Ogilvy’s eyes moved from the face to the hand resting on the back of the chair opposite. There was no evidence of tattooing, which he saw as a positive sign. Ogilvy regarded the modern culture of ink as a form of self-mutilation.

“Do you drink?” he asked.

“Not like Spider.”

“Married?”

“Only once.”

“Children?”

“God, no.”

“Vices?”

“Coltrane and Monk.”

“Ever killed anyone?”

“Not that I can recall.”

He said this with a smile. Reginald Ogilvy smiled in return.

“I’m wondering whether I might tempt you away from all this,” he said, glancing around the modest open-air dining room. “I’m prepared to pay you a generous salary. And when we’re not at sea, you’ll have plenty of free time to do whatever it is you like to do when you’re not cooking.”

“How generous?”

“Two thousand a week.”

“How much was Spider making?”

“Three,” replied Ogilvy after a moment’s hesitation. “But Spider was with me for two seasons.”

“He’s not with you now, is he?”

Ogilvy made a show of deliberation. “Three it is,” he said. “But I need you to start right away.”

“When do you sail?”

“Tomorrow morning.”

“In that case,” said the man called Colin Hernandez, “I suppose you’ll have to pay me four.”

Reginald Ogilvy, captain of the Aurora, surveyed the plates of food before rising gravely to his feet. “Eight o’clock,” he said. “Don’t be late.”

François, the quick-tempered Marseilles-born owner of Le Piment, did not take the news well. There was a string of affronts delivered in the rapid-fire patois of the south. There were promises of reprisals. And then there was the bottle of rather good Bordeaux, empty, that shattered into a thousand shards of emerald when hurled against the wall of the tiny kitchen. Later, François would deny he had been aiming at his departing chef. But Isabelle, a waitress who witnessed the incident, would call into question his version of events. François, she swore, had flung the bottle dagger-like directly at the head of Monsieur Hernandez. And Monsieur Hernandez, she recalled, had evaded the object with a movement that was so small and swift it occurred in the blink of an eye. Afterward, he had glared coldly at François for a long moment as though deciding how best to break his neck. Then, calmly, he had removed his spotless white kitchen apron and climbed aboard his motor scooter.

He spent the remainder of that night on the veranda of his cottage, reading by the light of his hurricane lamp. And at the top of every hour, he lowered his book and listened to the news on the BBC as the waves slapped and receded on the beach and the palm fronds hissed in the night wind. In the morning, after an invigorating swim in the sea, he showered, dressed, and packed his belongings into his canvas duffel: his clothing, his books, his radio. In addition, he packed two items that had been left for him on the islet of Tortu: a Stechkin 9mm pistol with a silencer screwed into the barrel, and a rectangular parcel, twelve inches by twenty. The parcel weighed sixteen pounds exactly. He placed it in the center of the duffel so it would remain balanced when carried.

He left the beach at Lorient for the last time at half past seven and, with the duffel resting upon his knees, rode into Gustavia. The Aurora sparkled at the edge of the harbor. He boarded at ten minutes to eight and was shown to his cabin by his sous-chef, a thin English girl with the unlikely name Amelia List. He stowed his possessions in the cupboard—including the Stechkin pistol and the sixteen-pound parcel—and dressed in the chef’s trousers and tunic that had been laid upon his berth. Amelia List was waiting in the corridor when he emerged. She escorted him to the galley and led him on a tour of the dry goods pantry, the walk-in refrigerator, and the storeroom filled with wine. It was there, in the cool darkness, that he had his first sexual thought about the English girl in the crisp white uniform. He did nothing to dispel it. He had been celibate for so many months that he could scarcely recall what it felt like to touch a woman’s hair or caress the flesh of a defenseless breast.

A few minutes before ten o’clock there came an announcement over the ship’s intercom instructing all members of the crew to report to the afterdeck. The man called Colin Hernandez followed Amelia List outside and was standing next to her when two black Range Rovers braked to a halt at Aurora’s stern. From the first emerged two giggling sunburned girls and a pale florid-faced man in his forties who was holding the straps of a pink beach bag in one hand and the neck of an open bottle of champagne in the other. Two athletic-looking men spilled from the second Rover, followed a moment later by a woman who looked to be suffering from a case of terminal melancholia. She wore a peach-colored dress that left the impression of partial nudity, a wide-brimmed hat that shadowed her slender shoulders, and large opaque sunglasses that concealed much of her porcelain face. Even so, she was instantly recognizable. Her profile betrayed her, the profile so admired by the fashion photographers and the paparazzi who stalked her every move. There were no paparazzi present that morning. For once she had eluded them.

She stepped aboard the Aurora as though she were stepping over an open grave and slipped past the assembled crew without a word or glance, passing so close to the man called Colin Hernandez he had to suppress an urge to touch her to make certain she was real and not a hologram. Five minutes later the Aurora eased into the harbor, and by noon the enchanted island of Saint Barthélemy was a lump of brown-green on the horizon. Stretched topless upon the foredeck, drink in hand, her flawless skin baking in the sun, was the most famous woman in the world. And one deck below, preparing an appetizer of tuna tartare, cucumber, and pineapple, was the man who was going to kill her.

2 (#ulink_9b9f5466-fe88-57ef-97fd-da168e26b386)

OFF THE LEEWARD ISLANDS (#ulink_9b9f5466-fe88-57ef-97fd-da168e26b386)

EVERYONE KNEW THE STORY. AND even those who pretended not to care, or expressed disdain over her worldwide cult of devotion, knew every sordid detail. She was the immensely shy and beautiful middle-class girl from Kent who had managed to find her way to Cambridge, and he was the handsome and slightly older future king of England. They had met at a campus debate having something to do with the environment, and, according to the legend, the future king was instantly smitten. A lengthy courtship followed, quiet and discreet. The girl was vetted by the future king’s people; the future king, by hers. Finally, one of the naughtier tabloids managed to snap a photograph of the couple leaving the Duke of Rutland’s annual summer ball at Belvoir Castle. Buckingham Palace released a bland piece of paper confirming the obvious, that the future king and the middle-class girl with no aristocratic blood in her veins were dating. Then, a month later, with the tabloids ablaze with rumors and speculation, the palace announced that the middle-class girl and the future king planned to marry.

They were wed at St. Paul’s Cathedral on a morning in June when the skies of southern England poured with black rain. Later, when things fell apart, there were some in the British press who would write that they were doomed from the start. The girl, by temperament and breeding, was wholly unsuited for life in the royal fishbowl; and the future king, for all the same reasons, was equally unsuited for marriage. He had many lovers, too many to count, and the girl punished him by taking one of her security guards to her bed. The future king, when told of the affair, banished the guard to a lonely outpost in Scotland. Distraught, the girl attempted suicide by taking an overdose of sleeping tablets and was rushed to the emergency room at St. Anne’s Hospital. Buckingham Palace announced she was suffering from dehydration caused by a bout of influenza. When asked to explain why her husband had not visited her in the hospital, the palace murmured something about a scheduling conflict. The statement raised far more questions than it answered.

Upon her release, it became obvious to royal watchers that all was not well with the future king’s beautiful wife. Even so, she performed her marital duty by bearing him two heirs, a son and a daughter, both delivered after abbreviated and difficult pregnancies. The king showed his gratitude by returning to the bed of a woman to whom he had once proposed marriage, and the princess retaliated by attaining a global celebrity that eclipsed that of the king’s sainted mother. She traveled the world in support of noble causes, a horde of reporters and photographers hanging on her every word and movement, and yet all the while no one seemed to notice she was sliding toward something like madness. Finally, with her blessing and quiet assistance, it all came spilling onto the pages of a tell-all book: her husband’s infidelities, the bouts of depression, the suicide attempts, the eating disorder brought on by her constant exposure to the press and public. The future king, incensed, engineered a stream of retaliatory press leaks about his wife’s erratic behavior. Then came the coup de grâce, the recording of a passionate telephone conversation between the princess and her favorite lover. By then, the Queen had had enough. With the monarchy in jeopardy, she asked the couple to divorce as quickly as possible. They did so a month later. Buckingham Palace, without a trace of irony, issued a statement declaring the termination of the royal marriage “amicable.”

The princess was permitted to keep her apartments in Kensington Palace but was stripped of the title Her Royal Highness. The Queen offered her a second-tier honorific but she refused it, preferring instead to be called by her given name. She even shed her SO14 bodyguards, for she viewed them more as spies than protectors of her security. The palace quietly kept tabs on her movements and associations, as did British intelligence, which viewed her more as a nuisance than a threat to the realm.

In public, she was the radiant face of global compassion. But behind closed doors she drank too much and surrounded herself with an entourage that one royal adviser described as “Eurorubbish.” On this trip, however, her retinue of companions was smaller than usual. The two sunburned women were childhood friends; the man who boarded Aurora with an open bottle of champagne was Simon Hastings-Clarke, the grotesquely wealthy viscount who supported her in the style to which she had become accustomed. It was Hastings-Clarke who flew her privately around the world on his fleet of jets, and Hastings-Clarke who footed the bill for her bodyguards. The two men who accompanied them to the Caribbean were employed by a private security firm in London. Before leaving Gustavia, they had subjected the Aurora and its crew to only a cursory inspection. Of the man called Colin Hernandez, they asked a single question: “What are we having for lunch?”

At the request of the former princess, it was a light buffet, though neither she nor her companions seemed terribly interested in it. They drank a great deal that afternoon, roasting their bodies in the harsh sun of the foredeck, until a rainstorm drove them laughing to their staterooms. They remained there until nine that evening, when they emerged dressed and groomed as though for a garden party in Somerset. They had cocktails and canapés on the afterdeck and then repaired to the main salon for dinner: salad with truffle-infused vinaigrette, followed by lobster risotto and rack of lamb with artichoke, lemon forte, courgette, and piment d’argile. The former princess and her companions declared the meal magnificent and demanded an appearance by the chef. When finally he appeared, they serenaded him with childlike applause.

“What will you make us tomorrow night?” asked the former princess.

“It’s a surprise,” he replied in his peculiar accent.

“Oh, good,” she said, fixing him with the same smile he had seen on countless magazine covers. “I do like surprises.”

They were a small crew, eight in all, and it was the responsibility of the chef and his assistant to see to the china, the stemware, the silver, the pots and pans, and the cooking utensils. They stood side by side at the basin long after the former princess and her companions had turned in, their hands occasionally touching beneath the warm soapy water, her bony hip pressing against his thigh. And once, as they squeezed past one another in the linen cabinet, her firm nipples traced two lines across his back, sending a charge of electricity and blood to his groin. They retired to their cabins alone, but a few minutes later he heard a butterfly tap at his door. She took him without a sound. It was like performing the act of love with a mute.

“Maybe this was a mistake,” she whispered into his ear when they had finished.

“Why would you say that?”

“Because we’re going to be working together for a long time.”

“Not so long.”

“You’re not planning to stay?”

“That depends.”

“On what?”

He said nothing more. She laid her head on his chest and closed her eyes.

“You can’t stay here,” he said.

“I know,” she answered drowsily. “Just for a little while.”

He lay motionless for a long time after, Amelia List sleeping on his chest, the Aurora rising and falling beneath him, his mind working through the details of what was to come. Finally, at three o’clock, he eased from the berth and padded naked across the cabin to the cupboard. Soundlessly, he dressed in black trousers, a woolen sweater, and a dark waterproof coat. Then he removed the wrapper from the parcel—the parcel measuring twelve inches by twenty and weighing sixteen pounds precisely—and engaged the power source and the timer on the detonator. He returned the parcel to the cupboard and was reaching for the Stechkin pistol when he heard the girl stir behind him. He turned slowly and stared at her in the darkness.

“What was that?” she asked.

“Go back to sleep.”

“I saw a red light.”

“It was my radio.”

“Why are you listening to the radio at three in the morning?”

Before he could answer, the bedside lamp flared. Her eyes flashed across his dark clothing before settling on the silenced gun that was still in his hand. She opened her mouth to scream, but he placed his palm heavily across her face before any sound could escape. As she struggled to free herself from his grasp, he whispered soothingly into her ear. “Don’t worry, my love,” he was saying. “It will only hurt a little.”

Her eyes widened in terror. Then he twisted her head violently to the left, severing her spinal cord, and held her gently as she died.

It was not the custom of Reginald Ogilvy to stand the lonely hours of the middle watch, but concern for the safety of his famous passenger drove him to the bridge of the Aurora early that morning. He was checking the weather forecast on an onboard computer, a fresh cup of coffee in his hand, when the man called Colin Hernandez appeared at the top of the companionway, dressed entirely in black. Ogilvy looked up sharply and asked, “What are you doing here?” But he received no reply other than two rounds from the silenced Stechkin that pierced the front of his uniform and mauled his heart.

The coffee cup clattered loudly to the floor; Ogilvy, instantly dead, thudded heavily next to it. His killer moved calmly to the console, made a slight adjustment to the ship’s heading, and retreated down the companionway. The main deck was deserted, no other crew members on duty. He lowered one of the Zodiac dinghies into the black sea, clambered aboard, and released the line.

Adrift, he bobbed beneath a canopy of diamond-white stars, watching the Aurora slicing eastward toward the shipping lanes of the Atlantic, pilotless, a ghost ship. He checked the luminous face of his wristwatch. Then, when the dial read zero, he looked up again. Fifteen additional seconds elapsed, enough time for him to consider the remote possibility that the bomb was somehow defective. Finally, there was a flash on the horizon—the blinding white flash of the high explosive, followed by the orange-yellow of the secondary explosions and fire.

The sound was like the rumble of distant thunder. Afterward, there was only the sea beating against the side of the Zodiac, and the wind. With the press of a button, he fired the outboard and watched as the Aurora started her journey to the bottom. Then he turned the Zodiac to the west and opened the throttle.

3 (#ulink_95b842e5-1214-52f5-96ec-a958d9fc4ca2)

THE CARIBBEAN–LONDON (#ulink_95b842e5-1214-52f5-96ec-a958d9fc4ca2)

THE FIRST INDICATION OF TROUBLE came when Pegasus Global Charters of Nassau reported that a routine message to one of its vessels, the 154-foot luxury motor yacht Aurora, had received no reply. The Pegasus operations center immediately requested assistance from all commercial ships and pleasure craft in the vicinity of the Leeward Islands, and within minutes the crew of a Liberian-registered oil tanker reported that they had seen an unusual flash of light in the area at approximately 3:45 that morning. Shortly thereafter the crew of a container ship spotted one of the Aurora’s dinghies floating empty and adrift approximately one hundred miles south-southeast of Gustavia. Simultaneously, a private sailing vessel encountered life preservers and other floating debris a few miles to the west. Fearing the worst, Pegasus management phoned the British High Commission in Kingston and informed the honorary consul that the Aurora was missing and presumed lost. Management then sent along a copy of the passenger manifest, which included the given name of the former princess. “Tell me it isn’t her,” the honorary consul said incredulously, but Pegasus management confirmed that the passenger was indeed the former wife of the future king. The consul immediately rang his superiors at the Foreign Office in London, and the superiors determined the situation was of sufficient gravity to wake Prime Minister Jonathan Lancaster, at which point the crisis truly began.

The prime minister broke the news to the future king by telephone at half past one, but waited until nine to inform the British people and the world. Standing outside the black door of 10 Downing Street, his face grim, he recounted the facts as they were known at that time. The former wife of the future king had traveled to the Caribbean in the company of Simon Hastings-Clarke and two other longtime friends. On the holiday island of Saint Barthélemy, the party had boarded the luxury motor yacht Aurora for a planned one-week cruise. All contact with the vessel had been lost; surface debris had been discovered. “We hope and pray the princess will be found alive,” the prime minister said solemnly. “But we must prepare ourselves for the very worst.”

The first day of the search produced no remains or survivors. Nor did the second day or the third. After conferring with the Queen, Prime Minister Lancaster announced that his government was operating under the assumption that the beloved princess was dead. In the Caribbean, the search teams focused their efforts on finding wreckage rather than the bodies. It would not be a long search. In fact, just forty-eight hours later, an unmanned submersible operated by the French navy discovered the Aurora lying beneath two thousand feet of seawater. One expert who viewed the video images said it was clear the vessel had suffered some type of cataclysmic failure, almost certainly an explosion. “The question is,” he said, “was it an accident, or was it intentional?”

A majority of the country—reliable polling said it was so—refused to believe she was actually gone. They hung their hopes on the fact that only one of the Aurora’s two Zodiac dinghies had been found. Surely, they argued, she was adrift on the open seas or had washed ashore on a deserted island. One disreputable Web site went so far as to report that she had been spotted on Montserrat. Another said she was living quietly by the sea in Dorset. Conspiracy theorists of every stripe concocted lurid tales of a plot to kill the princess that was conceived by the Queen’s Privy Council and carried out by Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service, better known as MI6. Pressure mounted on its chief, Graham Seymour, to issue a full-throated denial of the allegations, but he steadfastly refused. “These aren’t allegations,” he told the foreign secretary during a tense meeting at the service’s vast riverfront headquarters. “These are fairy tales spun by people with mental disorders, and I won’t dignify them with a response.”

Privately, however, Seymour had already reached the conclusion that the explosion aboard the Aurora was not an accident. So, too, had his counterpart at the DGSE, the highly capable French intelligence service. A French analysis of the wreckage video had determined that the Aurora was blown apart by a bomb detonated belowdecks. But who had smuggled the device aboard the vessel? And who had primed the detonator? The DGSE’s prime suspect was the man who had been hired to replace the Aurora’s missing head chef on the evening before the yacht left port. The French forwarded to MI6 a grainy video of his arrival at Gustavia’s airport, along with a few poor-quality still photos captured by private storefront security cameras. They showed a man who did not care to have his picture taken. “He doesn’t strike me as the sort of chap who would go down with the ship,” Seymour told a gathering of his senior staff. “He’s out there somewhere. Find out who he really is and where he’s hiding out, preferably before the Frogs.”

He was a whisper in a half-lit chapel, a loose thread at the hem of a discarded garment. They ran the photographs through the computers. And when the computers failed to find a match, they searched for him the old-fashioned way, with shoe leather and envelopes filled with money—American money, of course, for in the nether regions of the espionage world, dollars remained the reserve currency. MI6’s man in Caracas could find no trace of him. Nor could he find any hint of an Anglo-Irish mother with a poetic heart, or of a Spanish-businessman father. The address on his passport turned out to be a derelict lot in a Caracas slum; his last known phone number was long deceased. A paid asset inside the Venezuelan secret police said he’d heard a rumor about a link to Castro, but a source close to Cuban intelligence murmured something about the Colombian cartels. “Maybe once,” said an incorruptible policeman in Bogotá, “but he parted company with the drug lords a long time ago. The last thing I heard, he was living in Panama with one of Noriega’s former mistresses. He had several million stashed in a dirty Panamanian bank and a beach condo on the Playa Farallón.” The former mistress denied all knowledge of him, and the manager of the bank in question, after accepting a bribe of ten thousand dollars, could find no record of any accounts bearing his name. As for the beach condo in Farallón, a neighbor could recall little of his appearance, only his voice. “He spoke with a peculiar accent,” he said. “It sounded as though he was from Australia. Or was it South Africa?”

Graham Seymour monitored the search for the elusive suspect from the comfort of his office, the finest office in all spydom, with its English garden of an atrium, its enormous mahogany desk used by all the chiefs who had come before him, its towering windows overlooking the river Thames, and its stately old grandfather clock constructed by none other than Sir Mansfield Smith Cumming, the first “C” of the British Secret Service. The splendor of his surroundings made Seymour restless. In his distant past, he had been a field man of some repute—not for MI6 but for MI5, Britain’s less glamorous internal security service, where he had served with distinction before making the short journey from Thames House to Vauxhall Cross. There were some in MI6 who resented the appointment of an outsider, but most saw “the crossing,” as it became known in the trade, as a sort of homecoming. Seymour’s father had been a legendary MI6 officer, a deceiver of the Nazis, a shaper of events in the Middle East. And now his son, in the prime of life, sat behind the desk before which Seymour the Elder had stood, cap in hand.

With power, however, there often comes a feeling of helplessness, and Seymour, the espiocrat, the boardroom spy, soon fell victim to it. As the search ground futilely on, and as pressure from Downing Street and the palace mounted, his mood grew brittle. He kept a photo of the target on his desk, next to the Victorian inkwell and the Parker fountain pen he used to mark his documents with his personal cipher. Something about the face was familiar. Seymour suspected that somewhere—on another battlefield, in another land—their paths had crossed. It didn’t matter that the service databases said it wasn’t so. Seymour trusted his own memory over the memory of any government computer.

And so, as the field hands chased down false leads and dug dry wells, Seymour conducted a search of his own from his gilded cage atop Vauxhall Cross. He began by scouring his prodigious memory, and when it failed him, he requested access to a stack of his old MI5 case files and searched those, too. Again he found no trace of his quarry. Finally, on the morning of the tenth day, the console telephone on Seymour’s desk purred sedately. The distinctive ringtone told him the caller was Uzi Navot, the chief of Israel’s vaunted secret intelligence service. Seymour hesitated, then cautiously lifted the receiver to his ear. As usual, the Israeli spymaster didn’t bother with an exchange of pleasantries.

“I think we might have found the man you’re looking for.”

“Who is he?”

“An old friend.”

“Of yours or ours?”

“Yours,” said the Israeli. “We don’t have any friends.”

“Can you tell me his name?”

“Not on the phone.”

“How soon can you be in London?”

The line went dead.

4 (#ulink_200fb4fa-4389-5530-a1bc-eb270d6bd805)

VAUXHALL CROSS, LONDON (#ulink_200fb4fa-4389-5530-a1bc-eb270d6bd805)

UZI NAVOT ARRIVED AT VAUXHALL CROSS shortly before eleven that evening and was fired into the executive suite in a pneumatic tube of an elevator. He wore a gray suit that fit him tightly through his massive shoulders, a white shirt that lay open against his thick neck, and rimless spectacles that pinched the bridge of his pugilist’s nose. At first glance, few assumed Navot to be an Israeli or even a Jew, a trait that had served him well during his career. Once upon a time he had been a katsa, the term used by his service to describe undercover field operatives. Armed with an array of languages and a pile of false passports, Navot had penetrated terror networks and recruited a chain of spies and informants scattered around the world. In London he had been known as Clyde Bridges, the European marketing director for an obscure business software firm. He had run several successful operations on British soil at a time when it was Seymour’s responsibility to prevent such activity. Seymour held no grudge, for such was the nature of relationships between spies: adversaries one day, allies the next.

A frequent visitor to Vauxhall Cross, Navot did not remark on the beauty of Seymour’s grand office. Nor did he engage in the usual round of professional gossip that preceded most encounters between inhabitants of the secret world. Seymour knew the reason for the Israeli’s taciturn mood. Navot’s first term as chief was nearing its end, and his prime minister had asked him to step aside for another man, a legendary officer with whom Seymour had worked on numerous occasions. There was talk that the legend had struck a deal to retain Navot’s services. It was unorthodox, allowing one’s predecessor to remain on the premises, but the legend rarely concerned himself with adherence to orthodoxy. His willingness to take chances was his greatest strength—and sometimes, thought Seymour, his undoing.

Dangling from Navot’s powerful right hand was a stainless-steel attaché case with combination locks. From it he removed a slender file folder, which he placed on the mahogany desk. Inside was a document, one page in length; the Israelis prided themselves on the brevity of their cables. Seymour read the subject line. Then he glanced at the photograph lying next to his inkwell and swore softly. On the opposite side of the imposing desk, Uzi Navot permitted himself a brief smile. It wasn’t often that one succeeded in telling the director-general of MI6 something he didn’t already know.

“Who’s the source of the information?” asked Seymour.

“It’s possible he was an Iranian,” replied Navot vaguely.

“Does MI6 have regular access to his product?”

“No,” answered Navot. “He’s ours exclusively.”

MI6, the CIA, and Israeli intelligence had worked closely for more than a decade to delay the Iranian march toward a nuclear weapon. The three services had operated jointly against the Iranian nuclear supply chain and shared vast amounts of technical data and intelligence. It was agreed that the Israelis had the best human sources in Tehran, and, much to the annoyance of the Americans and the British, they protected them jealously. Judging from the wording of the report, Seymour suspected that Navot’s spy worked for VEVAK, the Iranian intelligence service. VEVAK sources were notoriously difficult to handle. Sometimes the information they traded for Western cash was genuine. And sometimes it was in the service of taqiyya, the Persian practice of displaying one intention while harboring another.

“Do you believe him?” asked Seymour.

“I wouldn’t be here otherwise.” Navot paused, then added, “And something tells me you believe him, too.”

When Seymour offered no reply, Navot drew a second document from his attaché case and laid it on the desktop next to the first. “It’s a copy of a report we sent to MI6 three years ago,” he explained. “We knew about his connection to the Iranians back then. We also knew he was working with Hezbollah, Hamas, al-Qaeda, and anyone else who would have him.” Navot added, “Your friend isn’t terribly discriminating about the company he keeps.”

“It was before my time,” Seymour intoned.

“But now it’s your problem.” Navot pointed toward a passage near the end of the document. “As you can see, we proposed an operation to take him out of circulation. We even volunteered to do the job. And how do you suppose your predecessor responded to our generous offer?”

“Obviously, he turned it down.”

“With extreme prejudice. In fact, he told us in no uncertain terms that we weren’t to lay a finger on him. He was afraid it would open a Pandora’s box.” Navot shook his head slowly. “And now here we are.”

The room was silent except for the ticking of C’s old grandfather clock. Finally, Navot asked quietly, “Where were you that day, Graham?”

“What day?”

“The fifteenth of August, nineteen ninety-eight.”

“The day of the bombing?”

Navot nodded.

“You know damn well where I was,” Seymour answered. “I was at Five.”

“You were the head of counterterrorism.”

“Yes.”

“Which meant it was your responsibility.”

Seymour said nothing.

“What happened, Graham? How did he get through?”

“Mistakes were made. Bad mistakes. Bad enough to ruin careers, even today.” Seymour gathered up the two documents and returned them to Navot. “Did your Iranian source tell you why he did it?”

“It’s possible he’s returned to the old fight. It’s also possible he was acting at the behest of others. Either way, he needs to be dealt with, sooner rather than later.”

Seymour made no response.

“Our offer still stands, Graham.”

“What offer is that?”

“We’ll take care of him,” Navot answered. “And then we’ll bury him in a hole so deep that none of the old problems will ever make it to the surface.”

Seymour lapsed into a contemplative silence. “There’s only one person I would trust with a job like this,” he said at last.

“That might be difficult.”

“The pregnancy?”

Navot nodded.

“When is she due?”

“I’m afraid that’s classified.”

Seymour managed a brief smile. “Do you suppose he might be persuaded to take the assignment?”

“Anything’s possible,” replied Navot noncommittally. “I’d be happy to make the approach on your behalf.”

“No,” said Seymour. “I’ll do it.”

“There is one other problem,” said Navot after a moment.

“Only one?”

“He doesn’t know much about that part of the world.”

“I know someone who can serve as his guide.”

“He won’t work with someone he doesn’t know.”

“Actually, they’re very well acquainted.”

“Is he MI6?”

“No,” replied Seymour. “Not yet.”

5 (#ulink_bb86e937-fec7-5970-b7cb-ab0c0bae1d81)

FIUMICINO AIRPORT, ROME (#ulink_bb86e937-fec7-5970-b7cb-ab0c0bae1d81)

WHY DO YOU SUPPOSE MY flight is delayed?” asked Chiara.

“It could be a mechanical problem,” replied Gabriel.

“It could be,” she repeated without conviction.

They were seated in a quiet corner of a first-class departure lounge. It didn’t matter the city, thought Gabriel, they were all the same. Unread newspapers, tepid bottles of suspect pinot grigio, CNN International playing silently on a large flat-panel television. By his own calculation, Gabriel had spent one-third of his career in places like this. Unlike his wife, he was extraordinarily good at waiting.

“Go ask that pretty girl at the information desk why my flight hasn’t been called,” she said.

“I don’t want to talk to the pretty girl at the information desk.”

“Why not?”

“Because she doesn’t know anything, and she’ll simply tell me something she thinks I want to hear.”

“Why must you always be so fatalistic?”

“It prevents me from being disappointed later.”

Chiara smiled and closed her eyes; Gabriel looked at the television. A British reporter in a helmet and flak jacket was talking about the latest airstrike on Gaza. Gabriel wondered why CNN had become so enamored with British reporters. He supposed it was the accent. The news always sounded more authoritative when delivered with a British accent, even if not a word of it was true.

“What’s he saying?” asked Chiara.

“Do you really want to know?”

“It’ll help pass the time.”

Gabriel squinted to read the closed captioning. “He says an Israeli warplane attacked a school where several hundred Palestinians were sheltering from the fighting. He says at least fifteen people were killed and several dozen more seriously wounded.”

“How many were women and children?”

“All of them, apparently.”

“Was the school the real target of the air raid?”

Gabriel typed a brief message into his BlackBerry and fired it securely to King Saul Boulevard, the headquarters of Israel’s foreign intelligence service. It had a long and deliberately misleading name that had very little to do with the true nature of its work. Employees referred to it as the Office and nothing else.

“The real target,” he said, his eyes on the BlackBerry, “was a house across the street.”

“Who lives in the house?”

“Muhammad Sarkis.”

“The Muhammad Sarkis?”

Gabriel nodded.

“Is Muhammad still among the living?”

“I’m afraid not.”

“What about the school?”

“It wasn’t hit. The only casualties were Sarkis and members of his family.”

“Maybe someone should tell that reporter the truth.”

“What good would it do?”

“More fatalism,” said Chiara.

“No disappointment.”

“Please find out why my flight is delayed.”

Gabriel typed another message into his BlackBerry. A moment later came the response.

“One of the Hamas rockets landed close to Ben-Gurion.”

“How close?” asked Chiara.

“Too close for comfort.”

“Do you think the pretty girl at the information desk knows my destination is under rocket fire?”

Gabriel was silent.

“Are you sure you want to go through with it?” asked Chiara.

“With what?”

“Don’t make me say it aloud.”

“Are you asking whether I still want to be the chief at a time like this?”

She nodded.

“At a time like this,” he said, watching the images of combat and explosions flickering on the screen, “I wish I could go to Gaza and fight alongside our boys.”

“I thought you hated the army.”

“I did.”

She tilted her head toward him and opened her eyes. They were the color of caramel and flecked with gold. Time had left no marks on her beautiful face. Were it not for her swollen abdomen and the band of gold on her finger, she might have been the same young girl he had first encountered a lifetime ago, in the ancient ghetto of Venice.

“Fitting, isn’t it?”

“What’s that?”

“That the children of Gabriel Allon should be born in a time of war.”

“With a bit of luck, the war will be over by the time they’re born.”

“I’m not so sure about that.” Chiara glanced at the departure board. The status box for Flight 386 to Tel Aviv read DELAYED. “If my plane doesn’t leave soon, they’re going to be born here in Italy.”

“Not a chance.”

“What would be so wrong with that?”

“We had a plan. And we’re sticking to the plan.”

“Actually,” she said archly, “the plan was for us to return to Israel together.”

“True,” said Gabriel, smiling. “But events intervened.”

“They usually do.”

Seventy-two hours earlier, in an ordinary parish church near Lake Como, Gabriel and Chiara had discovered one of the world’s most famous stolen paintings: Caravaggio’s Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence. The badly damaged canvas was now at the Vatican, where it was awaiting restoration. It was Gabriel’s intention to conduct the early stages himself. Such was his unique combination of talents. He was an art restorer, he was a master spy and assassin, a legend who had overseen some of the greatest operations in the history of Israeli intelligence. Soon he would be a father again, and then he would be the chief. They didn’t write stories about chiefs, he thought. They wrote stories about the men whom chiefs sent into the field to do their dirty work.

“I don’t know why you’re being so stubborn about that painting,” Chiara said.

“I found it, I want to restore it.”

“Actually, we found it. But that doesn’t change the fact that there’s no possible way you can finish it before the children are born.”

“It doesn’t matter whether I can finish it or not. I just want to—”

“Leave your mark on it?”

He nodded slowly. “It might be the last painting I ever get to restore. Besides, I owe it to him.”

“Who?”

He didn’t answer; he was reading the closed captioning on the television.

“What’s he talking about now?” Chiara asked.

“The princess.”

“What about her?”

“It seems the explosion that sank the boat was an accident.”

“Do you believe it?”

“No.”

“So why would they say something like that?”

“I suppose they want to give themselves time and space.”

“For what?”

“To find the man they’re looking for.”

Chiara closed her eyes and leaned her head against his shoulder. Her dark hair, with its shimmering auburn and chestnut highlights, smelled richly of vanilla. Gabriel kissed her hair softly and inhaled its scent. Suddenly, he didn’t want her to get on the airplane alone.

“What does the departure board say about my flight?” she asked.

“Delayed.”

“Can’t you do something to speed things up?”

“You overestimate my powers.”

“False modesty doesn’t suit you, darling.”

Gabriel typed another brief message into his BlackBerry and sent it to King Saul Boulevard. A moment later the device vibrated softly with the reply.

“Well?” asked Chiara.

“Watch the board.”

Chiara opened her eyes. The status box for El Al Flight 386 still read DELAYED. Thirty seconds later it changed to BOARDING.

“Too bad you can’t stop the war so easily,” Chiara said.

“Only Hamas can stop the war.”

She gathered up her carry-on bag and a stack of glossy magazines and rose carefully to her feet. “Be a good boy,” she said. “And if someone asks you for a favor, remember those three lovely words.”

“Find someone else.”

Chiara smiled. Then she kissed Gabriel with surprising urgency.

“Come home, Gabriel.”

“Soon.”

“No,” she said. “Come home now.”

“You’d better hurry, Chiara. Otherwise, you’ll miss your flight.”

She kissed him one last time. Then she turned away without another word and boarded the plane.

Gabriel waited until Chiara’s flight was safely airborne before leaving the terminal and making his way to Fiumicino’s chaotic parking garage. His anonymous German sedan was at the far end of the third deck, the front end facing out, lest he had reason to flee the garage in a hurry. As always, he searched the undercarriage for evidence of a concealed explosive before sliding behind the wheel and starting the engine. An Italian pop song blasted from the radio, one of those silly tunes Chiara was always singing to herself when she thought no one else was listening. Gabriel switched to the BBC, but it was filled with news about the war so he lowered the volume. There would be time enough for war later, he thought. For the next few weeks there would only be the Caravaggio.

He crossed the Tiber over the Ponte Cavour and made his way to the Via Gregoriana. The old Office safe flat was at the far end of the street, near the top of the Spanish Steps. He squeezed the sedan into an empty spot along the curb and retrieved his Beretta 9mm pistol from the glove box before climbing out. The chill night air smelled of frying garlic and faintly of wet leaves, the smell of Rome in autumn. Something about it always made Gabriel think of death.

He walked past the entrance of his building, past the awnings of the Hassler Villa Medici Hotel, to the Church of the Trinità dei Monti. A moment later, after determining he was not being followed, he returned to his apartment building. A single energy-efficient bulb burned weakly in the foyer; he moved through its sphere of light and climbed the darkened staircase. As he stepped onto the third-floor landing, he froze. The door of the flat was ajar, and from within came the sound of drawers opening and closing. Calmly, he drew the Beretta from the small of his back and used the barrel to slowly push open the door. At first, he could see no sign of the intruder. Then the door yielded another inch and he glimpsed Graham Seymour standing at the kitchen counter, an unopened bottle of Gavi in one hand and a corkscrew in the other. Gabriel slipped the gun into his coat pocket and went inside. And in his head he was thinking of three lovely words.

Find someone else …

6 (#ulink_b9be07f1-3590-54ea-93ca-6cee9e41e808)

VIA GREGORIANA, ROME (#ulink_b9be07f1-3590-54ea-93ca-6cee9e41e808)

PERHAPS YOU’D BETTER SEE TO this, Gabriel. Otherwise, someone’s liable to get hurt.”

Seymour surrendered the bottle of wine and the corkscrew and leaned against the kitchen counter. He wore gray flannel trousers, a herringbone jacket, and a blue dress shirt with French cuffs. The absence of personal aides or a security detail suggested he had traveled to Rome using a pseudonymous passport. It was a bad sign. The chief of MI6 traveled clandestinely only when he had a serious problem.

“How did you get in here?” asked Gabriel.

Seymour fished a key from the pocket of his trousers. Attached was the simple black medallion so beloved by Housekeeping, the Office division that procured and managed safe properties.

“Where did you get that?”

“Uzi gave it to me yesterday in London.”

“And the code for the alarm? I suppose he gave you that, too.”

Seymour recited the eight-digit number.

“That’s a violation of Office protocol.”

“There were extenuating circumstances. Besides,” added Seymour, “after all the operations we’ve done together, I’m practically a member of the family.”

“Even family members knock before entering a room.”

“You’re one to talk.”

Gabriel removed the cork from the bottle, poured out two glasses, and handed one to Seymour. The Englishman raised his glass a fraction of an inch and said, “To fatherhood.”

“It’s bad luck to drink to children who haven’t been born yet, Graham.”

“Then what shall we drink to?”

When Gabriel offered no answer, Seymour went into the sitting room. From its picture window it was possible to see the bell tower of the church and the top of the Spanish Steps. He stood there for a moment gazing out across the rooftops as though he were admiring the rolling hills of his country estate from the terrace of his manor house. With his pewter-colored locks and sturdy jaw, Graham Seymour was the archetypal British civil servant, a man who’d been born, bred, and educated to lead. He was handsome, but not too; he was tall, but not remarkably so. He made others feel inferior, especially Americans.

“You know,” he said finally, “you really should find somewhere else to stay when you’re in Rome. The entire world knows about this safe flat, which means it isn’t a safe flat at all.”

“I like the view.”

“I can see why.”

Seymour returned his gaze to the darkened rooftops. Gabriel sensed there was something troubling him. He would get around to it eventually. He always did.

“I hear your wife left town today,” he said at last.

“What other privileged information did the chief of my service share with you?”

“He mentioned something about a painting.”

“It’s not just any painting, Graham. It’s the—”

“Caravaggio,” said Seymour, finishing Gabriel’s sentence for him. Then he smiled and added, “You do have a knack for finding things, don’t you?”

“Is that supposed to be a compliment?”

“I suppose it was.”

Seymour drank. Gabriel asked why Uzi Navot had come to London.

“He had a piece of intelligence he wanted me to see. I have to admit,” Seymour added, “he seemed in good spirits for a man in his position.”

“What position is that?”

“Everyone in the business knows Uzi is on his way out,” answered Seymour. “And he’s leaving behind a terrible mess. The entire Middle East is in flames, and it’s going to get a lot worse before it gets better.”

“Uzi wasn’t the one who made the mess.”

“No,” agreed Seymour, “the Americans did that. The president and his advisers were too quick to part ways with the Arab strongmen. Now the president’s confronted with a world gone mad, and he doesn’t have a clue as to what to do about it.”

“And if you were advising the president, Graham?”

“I’d tell him to resurrect the strongmen. It worked before, it can work again.”

“All the king’s horses, and all the king’s men.”

“Your point?”

“The old order is broken, and it can’t be put back together. Besides,” added Gabriel, “the old order is what brought us Bin Laden and the jihadists in the first place.”

“And when the jihadists try to evict the Jewish state from the House of Islam?”

“They are trying, Graham. And in case you haven’t noticed, they don’t have much use for the United Kingdom, either. Like it or not, we’re in this together.”

Gabriel’s BlackBerry vibrated. He looked at the screen and frowned.

“What is it?” asked Seymour.

“Another cease-fire.”

“How long will this one last?”

“I suppose until Hamas decides to break it.” Gabriel placed the BlackBerry on the coffee table and regarded Seymour curiously. “You were about to tell me what you’re doing in my apartment.”

“I have a problem.”

“What’s his name?”

“Quinn,” answered Seymour. “Eamon Quinn.”

Gabriel ran the name through the database of his memory but found no match. “Irish?” he asked.

Seymour nodded.

“Republican?”

“Of the worst kind.”

“So what’s the problem?”

“A long time ago, I made a mistake and people died.”

“And Quinn was responsible?”

“Quinn lit the fuse, but ultimately I was responsible. That’s the wonderful thing about our business. Our mistakes always come back to haunt us, and eventually all debts come due.” Seymour raised his glass toward Gabriel. “Can we drink to that?”

7 (#ulink_2d81aa12-fb0a-5363-a72f-5e019ea95110)

VIA GREGORIANA, ROME (#ulink_2d81aa12-fb0a-5363-a72f-5e019ea95110)

THE SKIES HAD BEEN THREATENING all afternoon. Finally, at half past ten, a torrential downpour briefly turned the Via Gregoriana into a Venetian canal. Graham Seymour stood at the window watching fat gobbets of rain hammering against the terrace, but in his thoughts it was the hopeful summer of 1998. The Soviet Union was a memory. The economies of Europe and America were roaring. The jihadists of al-Qaeda were the stuff of white papers and terminally boring seminars about future threats. “We fooled ourselves into thinking we had reached the end of history,” he was saying. “There were some in Parliament who actually proposed disbanding the Security Service and MI6 and burning us all at the stake.” He glanced over his shoulder. “They were days of wine and roses. They were days of delusion.”

“Not for me, Graham. I was out of the business at the time.”

“I remember.” Seymour turned away from Gabriel and watched the rain beating against the glass. “You were living in Cornwall then, weren’t you? In that little cottage on the Helford River. Your first wife was at the psychiatric hospital in Stafford, and you were supporting her by cleaning paintings for Julian Isherwood. And there was that boy who lived in the cottage next door. His name escapes me.”

“Peel,” said Gabriel. “His name was Timothy Peel.”

“Ah, yes, young Master Peel. We could never figure out why you were spending so much time with him. And then we realized he was exactly the same age as the son you lost to the bomb in Vienna.”

“I thought we were talking about you, Graham.”

“We are,” replied Seymour.

He then reminded Gabriel, needlessly, that in the summer of 1998 he was the chief of counterterrorism at MI5. As such, he was responsible for protecting the British homeland from the terrorists of the Irish Republican Army. And yet even in Ulster, scene of a centuries-old conflict between Protestants and Catholics, there were signs of hope. The voters of Northern Ireland had ratified the Good Friday peace accords, and the Provisional IRA was adhering to the terms of the cease-fire. Only the Real IRA, a small band of hard-line dissidents, carried on the armed struggle. Its leader was Michael McKevitt, the former quartermaster general of the IRA. His common-law wife, Bernadette Sands-McKevitt, ran the political wing: the 32 County Sovereignty Movement. She was the sister of Bobby Sands, the Provisional IRA member who starved himself to death in the Maze prison in 1981.

“And then,” said Seymour, “there was Eamon Quinn. Quinn planned the operations. Quinn built the bombs. Unfortunately, he was good. Very good.”

A heavy thunderclap shook the building. Seymour gave an involuntary flinch before continuing.

“Quinn had a certain genius for building highly effective bombs and delivering them to their targets. But what he didn’t know,” Seymour added, “was that I had an agent watching over his shoulder.”

“How long was he there?”

“My agent was a woman,” answered Seymour. “And she was there from the beginning.”

Managing the agent and her intelligence, Seymour continued, proved to be a delicate balancing act. Because the agent was highly placed within the organization, she often had advance knowledge of attacks, including the target, the time, and the size of the bomb.

“What were we to do?” asked Seymour. “Disrupt the attacks and put the agent at risk? Or allow the attacks to go forward and try to make sure no one gets killed in the process?”

“The latter,” replied Gabriel.

“Spoken like a true spy.”

“We’re not policemen, Graham.”

“Thank God for that.”

For the most part, said Seymour, the strategy worked. Several large car bombs were defused, and several others exploded with minimal casualties, though one virtually leveled the High Street of Portadown, a loyalist stronghold, in February 1998. Then, six months later, MI5’s spy reported the group was plotting a major attack. Something big, she warned. Something that would blow the Good Friday peace process to bits.

“What were we supposed to do?” asked Seymour.

Outside, the sky exploded with lightning. Seymour emptied his glass and told Gabriel the rest of it.

On the evening of August 13, 1998, a maroon Vauxhall Cavalier, registration number 91 DL 2554, vanished from a housing estate in Carrickmacross, in the Republic of Ireland. It was driven to an isolated farm along the border and fitted with a set of false Northern Ireland plates. Then Quinn fitted it with the bomb: five hundred pounds of fertilizer, a machine-tooled booster rod filled with high explosive, a detonator, a power source hidden in a plastic food container, an arming switch in the glove box. On the morning of Sunday, August 15, he drove the car across the border to Omagh and parked it outside the S.D. Kells department store on Lower Market Street.

“Obviously,” said Seymour, “Quinn didn’t deliver the bomb alone. There was another man in the Vauxhall, two more in a scout car, and another man who drove the getaway car. They communicated by cellular phone. And we were listening to every word.”

“The Security Service?”

“No,” replied Seymour. “Our ability to monitor phone calls didn’t extend beyond the borders of the United Kingdom. The Omagh plot originated in the Irish Republic, so we had to rely on GCHQ to do the eavesdropping for us.”

The Government Communications Headquarters, or GCHQ, was Britain’s version of the NSA. At 2:20 p.m. it intercepted a call from a man who sounded like Eamon Quinn. He spoke six words: “The bricks are in the wall.” MI5 knew from past experience that the phrase meant the bomb was in place. Twelve minutes later Ulster Television received an anonymous telephone warning: “There’s a bomb, courthouse, Omagh, main street, five hundred pounds, explosion in thirty minutes.” The Royal Ulster Constabulary began evacuating the streets around Omagh’s courthouse and frantically looking for the bomb. What they didn’t realize was that they were looking in the wrong place.

“The telephone warning was incorrect,” said Gabriel.

Seymour nodded slowly. “The Vauxhall wasn’t anywhere near the courthouse. It was several hundred yards farther down Lower Market Street. When the RUC began the evacuation, they unwittingly drove people toward the bomb rather than away from it.” Seymour paused, then added, “But that’s exactly what Quinn wanted. He wanted people to die, so he deliberately parked the car in the wrong place. He double-crossed his own organization.”

At ten minutes past three the bomb detonated. Twenty-nine people were killed, another two hundred were wounded. It was the deadliest act of terrorism in the history of the conflict. So powerful was the revulsion that the Real IRA felt compelled to issue an apology. Somehow, the peace process held. After thirty years of blood and bombs, the people of Northern Ireland had finally had enough.

“And then the press and the families of the victims started to ask uncomfortable questions,” said Seymour. “How did the Real IRA manage to plant a bomb in the middle of Omagh without the knowledge of the police and the security services? And why were there no arrests?”

“What did you do?”

“We did what we always do. We closed ranks, burned our files, and waited for the storm to pass.”

Seymour rose, carried his glass into the kitchen, and removed the bottle of Gavi from the refrigerator. “Do you have anything stronger than this?”

“Like what?”

“Something distilled.”

“I’d rather drink acetone than distilled spirits.”

“Acetone with a twist might do the trick about now.” Seymour dumped an inch of wine into his glass and placed the bottle on the counter.

“What happened to Quinn after Omagh?”

“Quinn went into private practice. Quinn went international.”

“What kind of work did he do?”

“The usual,” replied Seymour. “Security work for the thugs and potentates, bomb-making clinics for the revolutionaries and the religiously deranged. We caught a glimpse of him every now and again, but for the most part he flew beneath our radar. Then the chief of Iranian intelligence invited him to Tehran, at which point King Saul Boulevard entered the picture.”

Seymour popped the latches on his briefcase, removed a single sheet of paper, and placed it on the coffee table. Gabriel looked at the document and frowned.

“Another violation of Office protocol.”

“What’s that?”

“Carrying a classified Office cable in an insecure briefcase.”

Gabriel picked up the document and began to read. It stated that Eamon Quinn, former member of the Real IRA, mastermind of the Omagh terrorist outrage, had been retained by Iranian intelligence to develop highly lethal roadside bombs to be used against British and American forces in Iraq. The same Eamon Quinn had performed a similar service for Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in the Gaza Strip. In addition, he had traveled to Yemen, where he had helped al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula construct a small liquid bomb that could be slipped onto an American jetliner. He was, the report said in its concluding paragraph, one of the most dangerous men in the world and needed to be eliminated immediately.