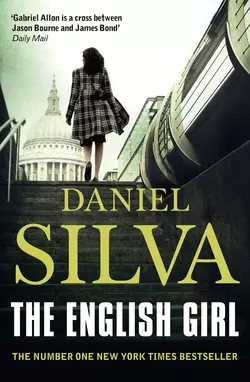

The English Girl

The English Girl

Daniel Silva

Gabriel Allon, master art restorer and assassin, returns in a spellbinding new thriller from No.1 bestselling author Daniel Silva. For all fans of Robert Ludlum.

When a beautiful young British woman vanishes on the island of Corsica, a prime minister’s career is threatened with destruction. And Gabriel Allon, master art restorer, spy, and assassin, is thrust into a game of shadows where nothing is what it seems and where the only thing more dangerous than his enemies might be the truth…

The English Girl

Daniel Silva

Copyright (#ulink_59e93cf2-2bcb-5bd7-92c1-2bf7488f9a9c)

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2013

Copyright © Daniel Silva 2013

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Cover photographs © Elizabeth Ansley/Arcangel Images (woman); Mark Owen/Trevillion Images (city scene)

Daniel Silva asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © 2014 ISBN: 9780007433377

Version: 2014-07-03

Dedication (#ulink_a5477289-542d-5b45-af2e-897876f84b8c)

Once again, for my wife, Jamie,and my children, Lily and Nicholas

He who lives an immoral lifedies an immoral death.

CORSICAN PROVERB

Table of Contents

Cover (#u1f41b2b2-1ddf-5636-8d39-2611f984b127)

Title Page (#u362cce9e-9baa-5b1d-a900-c0d63e17221b)

Copyright (#uff4d443f-b28d-5b1b-b22e-f7020cbe6895)

Dedication (#ud8f2606f-e5ca-58d5-adbb-890362d81cd1)

Epigraph (#u21b02afa-49e3-509f-a7c9-c7163083ce48)

Part One: The Hostage (#u0f520e0c-db51-55fc-96aa-b105035cf66d)

1. Piana, Corsica (#u4f76c88b-d326-5072-9007-68ed6b601067)

2. Corsica–London (#ud54330a8-04b2-5dec-85db-86a42b676a73)

3. Jerusalem (#u8327a574-4e7b-5491-9322-742900dee3b4)

4. King David Hotel, Jerusalem (#u3ddc1e90-7103-5f47-af7a-6f9c2389d2a0)

5. King David Hotel, Jerusalem (#u3bdd3dbc-682d-547b-a5d9-0b68ee287ecf)

6. Israel Museum, Jerusalem (#u65f2cc6d-4996-5e5f-b37f-8b28e27f10d5)

7. Corsica (#ue0f4080e-fcb2-5a79-ab37-ce04531bbc7b)

8. Corsica (#ue04c6922-bbd4-5eac-b5b1-8a5f9a6cf95b)

9. Corsica (#u5591a233-5e97-565c-b91e-c00641cbaec8)

10. Marseilles (#u90813328-c7c9-52ab-9fa2-495cc541c9de)

11. Off Marseilles (#u0d09187e-ad0c-5181-ac02-1c29b8ed711d)

12. Off Marseilles (#u6cefc600-8823-5865-8de4-f5c9723ff20d)

13. Côte D’Azur, France (#ufad0627d-5fc1-5b3c-bf43-41282b57edb3)

14. Aix-En-Provence, France (#u087bd7c1-4305-562f-937e-231ed7b530ee)

15. Aix-En-Provence, France (#litres_trial_promo)

16. The Lubéron, France (#litres_trial_promo)

17. Paris (#litres_trial_promo)

18. Apt, France (#litres_trial_promo)

19. The Lubéron, France (#litres_trial_promo)

20. Marseilles–London (#litres_trial_promo)

21. 10 Downing Street (#litres_trial_promo)

22. London (#litres_trial_promo)

23. 10 Downing Street (#litres_trial_promo)

24. Dover, England (#litres_trial_promo)

25. Grand-Fort-Philippe, France (#litres_trial_promo)

26. Northern France (#litres_trial_promo)

27. Grand-Fort-Philippe, France (#litres_trial_promo)

28. Pas-De-Calais, France (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two: The Spy (#litres_trial_promo)

29. Audresselles, Pas-De-Calais (#litres_trial_promo)

30. Tiberias, Israel (#litres_trial_promo)

31. Corsica (#litres_trial_promo)

32. Corsica–London (#litres_trial_promo)

33. London (#litres_trial_promo)

34. Basildon, Essex (#litres_trial_promo)

35. Basildon, Essex (#litres_trial_promo)

36. Chelsea, London (#litres_trial_promo)

37. Cheyne Walk, Chelsea (#litres_trial_promo)

38. Hampstead Heath, London (#litres_trial_promo)

39. Grayswood, Surrey (#litres_trial_promo)

40. Grayswood, Surrey (#litres_trial_promo)

41. Mayfair, London (#litres_trial_promo)

42. Copenhagen, Denmark (#litres_trial_promo)

43. Copenhagen, Denmark (#litres_trial_promo)

44. Copenhagen, Denmark (#litres_trial_promo)

45. Zealand, Denmark (#litres_trial_promo)

46. Grayswood, Surrey (#litres_trial_promo)

47. Grayswood, Surrey (#litres_trial_promo)

48. Moscow (#litres_trial_promo)

49. Red Square, Moscow (#litres_trial_promo)

50. Café Pushkin, Moscow (#litres_trial_promo)

51. Tver Oblast, Russia (#litres_trial_promo)

52. Tver Oblast, Russia (#litres_trial_promo)

53. St. Petersburg, Russia (#litres_trial_promo)

54. Lubyanka Square, Moscow (#litres_trial_promo)

55. St. Petersburg, Russia (#litres_trial_promo)

56. Lubyanka Square, Moscow (#litres_trial_promo)

57. St. Petersburg, Russia (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: The Scandal (#litres_trial_promo)

58. London–Jerusalem (#litres_trial_promo)

59. London (#litres_trial_promo)

60. London (#litres_trial_promo)

61. Corsica (#litres_trial_promo)

62. Corsica (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also Written By Daniel Silva (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART ONE (#ulink_935ac286-54b1-5f07-bbe6-c26fa7627082)

1 (#ulink_a1c58006-224c-5bf0-a2a9-444c3a78fbf4)

PIANA, CORSICA (#ulink_a1c58006-224c-5bf0-a2a9-444c3a78fbf4)

THEY CAME FOR her in late August, on the island of Corsica. The precise time would never be determined—some point between sunset and noon the following day was the best any of her housemates could do. Sunset was when they saw her for the last time, streaking down the drive of the villa on a red motor scooter, a gauzy cotton skirt fluttering about her suntanned thighs. Noon was when they realized her bed was empty except for a trashy half-read paperback novel that smelled of coconut oil and faintly of rum. Another twenty-four hours would elapse before they got around to calling the gendarmes. It had been that kind of summer, and Madeline was that kind of girl.

They had arrived on Corsica a fortnight earlier, four pretty girls and two earnest boys, all faithful servants of the British government or the political party that was running it these days. They had a single car, a communal Renault hatchback large enough to accommodate five uncomfortably, and the red motor scooter which was exclusively Madeline’s and which she rode with a recklessness bordering on suicidal. Their ocher-colored villa stood at the western fringe of the village on a cliff overlooking the sea. It was tidy and compact, the sort of place estate agents always described as “charming.” But it had a swimming pool and a walled garden filled with rosemary bushes and pepper trees; and within hours of alighting there they had settled into the blissful state of sunburned semi-nudity to which British tourists aspire, no matter where their travels take them.

Though Madeline was the youngest of the group, she was their unofficial leader, a burden she accepted without protest. It was Madeline who had managed the rental of the villa, and Madeline who arranged the long lunches, the late dinners, and the day trips into the wild Corsican interior, always leading the way along the treacherous roads on her motor scooter. Not once did she bother to consult a map. Her encyclopedic knowledge of the island’s geography, history, culture, and cuisine had been acquired during a period of intense study and preparation conducted in the weeks leading up to the journey. Madeline, it seemed, had left nothing to chance. But then she rarely did.

She had come to the Party’s Millbank headquarters two years earlier, after graduating from the University of Edinburgh with degrees in economics and social policy. Despite her second-tier education—most of her colleagues were products of elite public schools and Oxbridge—she rose quickly through a series of clerical posts before being promoted to director of community outreach. Her job, as she often described it, was to forage for votes among classes of Britons who had no business supporting the Party, its platform, or its candidates. The post, all agreed, was but a way station along a journey to better things. Madeline’s future was bright—“solar flare bright,” in the words of Pauline, who had watched her younger colleague’s ascent with no small amount of envy. According to the rumor mill, Madeline had been taken under the wing of someone high in the Party. Someone close to the prime minister. Perhaps even the prime minister himself. With her television good looks, keen intellect, and boundless energy, Madeline was being groomed for a safe seat in Parliament and a ministry of her own. It was only a matter of time. Or so they said.

Which made it all the more odd that, at twenty-seven years of age, Madeline Hart remained romantically unattached. When asked to explain the barren state of her love life, she would declare she was too busy for a man. Fiona, a slightly wicked dark-haired beauty from the Cabinet Office, found the explanation dubious. More to the point, she believed Madeline was being deceitful—deceitfulness being one of Fiona’s most redeeming qualities, thus her interest in Party politics. To support her theory, she would point out that Madeline, while loquacious on almost every subject imaginable, was unusually guarded when it came to her personal life. Yes, said Fiona, she was willing to toss out the occasional harmless tidbit about her troubled childhood—the dreary council house in Essex, the father whose face she could scarcely recall, the alcoholic brother who’d never worked a day in his life—but everything else she kept hidden behind a moat and walls of stone. “Our Madeline could be an ax murderer or a high-priced tart,” said Fiona, “and none of us would be the wiser.” But Alison, a Home Office underling with a much-broken heart, had another theory. “The poor lamb’s in love,” she declared one afternoon as she watched Madeline rising goddess-like from the sea in the tiny cove beneath the villa. “The trouble is, the man in question isn’t returning the favor.”

“Why ever not?” asked Fiona drowsily from beneath the brim of an enormous sun visor.

“Maybe he’s in no position to.”

“Married?”

“But of course.”

“Bastard.”

“You’ve never?”

“Had an affair with a married man?”

“Yes.”

“Just twice, but I’m considering a third.”

“You’re going to burn in hell, Fi.”

“I certainly hope so.”

It was then, on the afternoon of the seventh day, and upon the thinnest of evidence, that the three girls and two boys staying with Madeline Hart in the rented villa at the edge of Piana took it upon themselves to find her a lover. And not just any lover, said Pauline. He had to be appropriate in age, fine in appearance and breeding, and stable in his finances and mental health, with no skeletons in his closet and no other women in his bed. Fiona, the most experienced when it came to matters of the heart, declared it a mission impossible. “He doesn’t exist,” she explained with the weariness of a woman who had spent much time looking for him. “And if he does, he’s either married or so infatuated with himself he won’t have the time of day for poor Madeline.”

Despite her misgivings, Fiona threw herself headlong into the challenge, if for no other reason than it would add a hint of intrigue to the holiday. Fortunately, she had no shortage of potential targets, for it seemed half the population of southeast England had abandoned their sodden isle for the sun of Corsica. There was the colony of City financiers who had rented grandly at the northern end of the Golfe de Porto. And the band of artists who were living like Gypsies in a hill town in the Castagniccia. And the troupe of actors who had taken up residence on the beach at Campomoro. And the delegation of opposition politicians who were plotting a return to power from a villa atop the cliffs of Bonifacio. Using the Cabinet Office as her calling card, Fiona quickly arranged a series of impromptu social encounters. And on each occasion—be it a dinner party, a hike into the mountains, or a boozy afternoon on the beach—she snared the most eligible male present and deposited him at Madeline’s side. None, however, managed to scale her walls, not even the young actor who had just completed a successful run as the lead in the West End’s most popular musical of the season.

“She’s obviously got it bad,” Fiona conceded as they headed back to the villa late one evening, with Madeline leading the way through the darkness on her red motor scooter.

“Who do you reckon he is?” asked Alison.

“Dunno,” Fiona drawled enviously. “But he must be someone quite special.”

It was at this point, with slightly more than a week remaining until their planned return to London, that Madeline began spending significant amounts of time alone. She would leave the villa early each morning, usually before the others had risen, and return in late afternoon. When asked about her whereabouts, she was transparently vague, and at dinner she was often sullen or preoccupied. Alison naturally feared the worst, that Madeline’s lover, whoever he was, had sent notice that her services were no longer required. But the following day, upon returning to the villa from a shopping excursion, Fiona and Pauline happily declared that Alison was mistaken. It seemed that Madeline’s lover had come to Corsica. And Fiona had the pictures to prove it.

The sighting had occurred at ten minutes past two, at Les Palmiers, on the Quai Adolphe Landry in Calvi. Madeline had been seated at a table along the edge of the harbor, her head turned slightly toward the sea, as though unaware of the man in the chair opposite. Large dark glasses concealed her eyes. A straw sun hat with an elaborate black bow shadowed her flawless face. Pauline had tried to approach the table, but Fiona, sensing the strained intimacy of the scene, had suggested a hasty retreat instead. She had paused long enough to surreptitiously snap the first incriminating photograph on her mobile phone. Madeline had appeared unaware of the intrusion, but not the man. At the instant Fiona pressed the camera button, his head had turned sharply, as if alerted by some animal instinct that his image was being electronically captured.

After fleeing to a nearby brasserie, Fiona and Pauline carefully examined the man in the photograph. His hair was gray-blond, windblown, and boyishly full. It fell onto his forehead and framed an angular face dominated by a small, rather cruel-looking mouth. The clothing was vaguely maritime: white trousers, a blue-striped oxford cloth shirt, a large diver’s wristwatch, canvas loafers with soles that would leave no marks on the deck of a ship. That was the kind of man he was, they decided. A man who never left marks.

They assumed he was British, though he could have been German or Scandinavian or perhaps, thought Pauline, a descendant of Polish nobility. Money was clearly not an issue, as evidenced by the pricey bottle of champagne sweating in the silver ice bucket anchored to the side of the table. His fortune was earned rather than inherited, they decided, and not altogether clean. He was a gambler. He had Swiss bank accounts. He traveled to dangerous places. Mainly, he was discreet. His affairs, like his canvas boat shoes, left no marks.

But it was the image of Madeline that intrigued them most. She was no longer the girl they knew from London, or even the girl with whom they had been sharing a villa for the past two weeks. It seemed she had adopted an entirely different demeanor. She was an actress in another movie. The other woman. Now, hunched over the mobile phone like a pair of schoolgirls, Fiona and Pauline wrote the dialogue and added flesh and bones to the characters. In their version of the story, the affair had begun innocently enough with a chance encounter in an exclusive New Bond Street shop. The flirtation had been long, the consummation meticulously planned. But the ending of the story temporarily eluded them, for in real life it had yet to be written. Both agreed it would be tragic. “That’s the way stories like this always end,” Fiona said from experience. “Girl meets boy. Girl falls in love with boy. Girl gets hurt and does her very best to destroy boy.”

Fiona would snap two more photographs of Madeline and her lover that afternoon. One showed them walking along the quay through brilliant sunlight, their knuckles furtively touching. The second showed them parting without so much as a kiss. The man then climbed into a Zodiac dinghy and headed out into the harbor. Madeline mounted her red motor scooter and started back toward the villa. By the time she arrived, she was no longer in possession of the sun hat with the elaborate black bow. That night, while recounting the events of her afternoon, she made no mention of a visit to Calvi, or of a luncheon with a prosperous-looking man at Les Palmiers. Fiona thought it a rather impressive performance. “Our Madeline is an extraordinarily good liar,” she told Pauline. “Perhaps her future is as bright as they say. Who knows? She might even be prime minister someday.”

That night, the four pretty girls and two earnest boys staying in the rented villa planned to dine in the nearby town of Porto. Madeline made the reservation in her schoolgirl French and even imposed on the proprietor to set aside his finest table, the one on the terrace overlooking the rocky sweep of the bay. It was assumed they would travel to the restaurant in their usual caravan, but shortly before seven Madeline announced she was going to Calvi to have a drink with an old friend from Edinburgh. “I’ll meet you at the restaurant,” she shouted over her shoulder as she sped down the drive. “And for heaven’s sake, try to be on time for a change.” And then she was gone. No one thought it odd when she failed to appear for dinner that night. Nor were they alarmed when they woke to find her bed unoccupied. It had been that kind of summer, and Madeline was that kind of girl.

2 (#ulink_f2a2da4b-4a59-5c19-935b-96179531daaa)

CORSICA–LONDON (#ulink_f2a2da4b-4a59-5c19-935b-96179531daaa)

THE FRENCH NATIONAL Police officially declared Madeline Hart missing at 2:00 p.m. on the final Friday of August. After three days of searching, they had found no trace of her except for the red motor scooter, which was discovered, headlamp smashed, in an isolated ravine near Monte Cinto. By week’s end, the police had all but given up hope of finding her alive. In public they insisted the case remained first and foremost a search for a missing British tourist. Privately, however, they were already looking for her killer.

There were no potential suspects or persons of interest other than the man with whom she had lunched at Les Palmiers on the afternoon before her disappearance. But, like Madeline, it seemed he had vanished from the face of the earth. Was he a secret lover, as Fiona and the others suspected, or had their acquaintance been recently made on Corsica? Was he British? Was he French? Or, as one frustrated detective put it, was he a space alien from another galaxy who had been turned into particles and beamed back to the mother ship? The waitress at Les Palmiers was of little help. She recalled that he spoke English to the girl in the sun hat but had ordered in perfect French. The bill he had paid in cash—crisp, clean notes that he dealt onto the table like a high-stakes gambler—and he had tipped well, which was rare these days in Europe, what with the economic crisis and all. What she remembered most about him were his hands. Very little hair, no sunspots or scars, clean nails. He obviously took good care of his nails. She liked that in a man.

His photograph, which was shown discreetly around the island’s better watering holes and eating establishments, elicited little more than an apathetic shrug. It seemed no one had laid eyes on him. And if they had, they couldn’t recall his face. He was like every other poseur who washed ashore in Corsica each summer: a good tan, expensive sunglasses, a golden hunk of Swiss-made ego on his wrist. He was a nothing with a credit card and a pretty girl on the other side of the table. He was the forgotten man.

To the shopkeepers and restaurateurs of Corsica, perhaps, but not to the French police. They ran his image through every criminal database they had in their arsenal, and then they ran it through a few more. And when each search produced nothing so much as a glimmer of a match, they debated whether to release a photo to the press. There were some, especially in the higher ranks, who argued against such a move. After all, they said, it was possible the poor fellow was guilty of nothing more than marital infidelity, hardly a crime in France. But when another seventy-two hours passed with no progress to speak of, they came to the conclusion they had no choice but to ask the public for help. Two carefully cropped photographs were released to the press—one of the man seated at Les Palmiers, the other of him walking along the quay—and by nightfall, investigators were inundated with hundreds of tips. They quickly weeded out the quacks and cranks and focused their resources on only those leads that were remotely plausible. But not one bore fruit. One week after the disappearance of Madeline Hart, their only suspect was still a man without a name or even a country.

Though the police had no promising leads, they had no shortage of theories. One group of detectives thought the man from Les Palmiers was a psychotic predator who had lured Madeline into a trap. Another group wrote him off as someone who had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time. He was married, according to this theory, and thus in no position to step forward to cooperate with police. As for Madeline’s fate, they argued, it was probably a robbery gone wrong—a young woman riding a motorbike alone, she would have been a tempting target. Eventually, the body would turn up. The sea would spit it out, a hiker would stumble across it in the hills, a farmer would unearth it while plowing his field. That was the way it was on the island. Corsica always gave up its dead.

In Britain, the failures of the police were an occasion to bash the French. But for the most part, even the newspapers sympathetic to the opposition treated Madeline’s disappearance as though it were a national tragedy. Her remarkable rise from a council house in Essex was chronicled in detail, and numerous Party luminaries issued statements about a promising career cut short. Her tearful mother and shiftless brother gave a single television interview and then disappeared from public view. The same was true of her holiday mates from Corsica. Upon their return to Britain, they appeared jointly at a news conference at Heathrow Airport, watched over by a team of Party press aides. Afterward, they refused all other interview requests, including those that came with lucrative payments. Absent from the coverage was any trace of scandal. There were no stories about heavy holiday drinking, sexual antics, or public disturbances, only the usual drivel about the dangers faced by young women traveling in foreign countries. At Party headquarters, the press team quietly congratulated themselves on their skillful handling of the affair, while the political staff noticed a marked spike in the prime minister’s approval numbers. Behind closed doors, they called it “the Madeline effect.”

Gradually, the stories about her fate moved from the front pages to the interior sections, and by the end of September she was gone from the papers entirely. It was autumn and therefore time to return to the business of government. The challenges facing Britain were enormous: an economy in recession, a euro zone on life support, a laundry list of unaddressed social ills that were tearing at the fabric of life in the United Kingdom. Hanging over it all was the prospect of an election. The prime minister had dropped numerous hints he intended to call one before the end of the year. He was well aware of the political perils of turning back now; Jonathan Lancaster was Britain’s current head of government because his predecessor had failed to call an election after months of public flirtation. Lancaster, then leader of the opposition, had called him “the Hamlet from Number Ten,” and the mortal wound was struck.

Which explained why Simon Hewitt, the prime minister’s director of communications, had not been sleeping well of late. The pattern of his insomnia never varied. Exhausted by the crushing daily grind of his job, he would fall asleep quickly, usually with a file propped on his chest, only to awaken after two or three hours. Once conscious, his mind would begin to race. After four years in government, he seemed incapable of focusing on anything but the negative. Such was the lot of a Downing Street press aide. In Simon Hewitt’s world, there were no triumphs, only disasters and near disasters. Like earthquakes, they ranged in severity from tiny tremors that were scarcely felt to seismic upheavals capable of toppling buildings and upending lives. Hewitt was expected to predict the coming calamity and, if possible, contain the damage. Lately, he had come to realize his job was impossible. In his darkest moments, this gave him a small measure of comfort.

He had once been a man to be reckoned with in his own right. As chief political columnist for the Times, Hewitt had been one of the most influential people in Whitehall. With but a few words of his trademark razor-edged prose, he could doom a government policy, along with the political career of the minister who had crafted it. Hewitt’s power had been so immense that no government would ever introduce an important initiative without first running it by him. And no politician dreaming of a brighter future would ever think about standing for a party leadership post without first securing Hewitt’s backing. One such politician had been Jonathan Lancaster, a former City lawyer from a safe seat in the London suburbs. At first, Hewitt didn’t think much of Lancaster; he was too polished, too good-looking, and too privileged to take seriously. But with time, Hewitt had come to regard Lancaster as a gifted man of ideas who wanted to remake his moribund political party and then remake his country. Even more surprising, Hewitt discovered he actually liked Lancaster, never a good sign. And as their relationship progressed, they spent less time gossiping about Whitehall political machinations and more time discussing how to repair Britain’s broken society. On election night, when Lancaster was swept to victory with the largest parliamentary majority in a generation, Hewitt was one of the first people he telephoned. “Simon,” he had said in that seductive voice of his. “I need you, Simon. I can’t do this alone.” Hewitt had then written glowingly of Lancaster’s prospects for success, knowing full well that in a few days’ time he would be working for him at Downing Street.

Now Hewitt opened his eyes slowly and stared contemptuously at the clock on his bedside table. It glowed 3:42, as if mocking him. Next to it were his three mobile devices, all fully charged for the media onslaught of the coming day. He wished he could so easily recharge his own batteries, but at this point no amount of sleep or tropical sunlight could repair the damage he had inflicted on his middle-aged body. He looked at Emma. As usual, she was sleeping soundly. Once, he might have pondered some lecherous way of waking her, but not now; their marital bed had become a frozen hearth. For a brief time, Emma had been seduced by the glamour of Hewitt’s job at Downing Street, but she had come to resent his slavish devotion to Lancaster. She saw the prime minister almost as a sexual rival and her hatred of him had reached an irrational fervor. “You’re twice the man he is, Simon,” she’d informed him last night before bestowing a loveless kiss on his sagging cheek. “And yet, for some reason, you feel the need to play the role of his handmaiden. Perhaps someday you’ll tell me why.”

Hewitt knew that sleep wouldn’t come again, not now, so he lay awake in bed and listened to the sequence of sounds that signaled the commencement of his day. The thud of the morning newspapers on his doorstep. The gurgle of the automatic coffeemaker. The purr of a government sedan in the street beneath his window. Rising carefully so as not to wake Emma, he pulled on his dressing gown and padded downstairs to the kitchen. The coffeemaker was hissing angrily. Hewitt prepared a cup, black for the sake of his expanding waistline, and carried it into the entrance hall. A blast of wet wind greeted him as he opened the door. The pile of newspapers was covered in plastic and lying on the welcome mat, next to a clay pot of dead geraniums. Stooping, he saw something else: a manila envelope, eight by ten, no markings, tightly sealed. Hewitt knew instantly it had not come from Downing Street; no one on his staff would dare to leave even the most trivial document outside his door. Therefore, it had to be something unsolicited. It was not unusual; his old colleagues in the press knew his Hampstead address and were forever leaving parcels for him. Small gifts for a well-timed leak. Angry rants over a perceived slight. A naughty rumor that was too sensitive to transmit via e-mail. Hewitt made a point of keeping up with the latest Whitehall gossip. As a former reporter, he knew that what was said behind a man’s back was oftentimes much more important than what was written about him on the front pages.

He prodded the envelope with his toe to make certain it contained no wiring or batteries, then placed it atop the newspapers and returned to the kitchen. After switching on the television and lowering the volume to a whisper, he removed the papers from the plastic wrapper and quickly scanned the front pages. They were dominated by Lancaster’s proposal to make British industry more competitive by lowering tax rates. The Guardian and the Independent were predictably appalled, but thanks to Hewitt’s efforts most of the coverage was positive. The other news from Whitehall was mercifully benign. No earthquakes. Not even a tremor.

After working his way through the so-called quality broadsheets, Hewitt quickly read the tabloids, which he regarded as a better barometer of British public opinion than any poll. Then, after refilling his coffee cup, he opened the anonymous envelope. Inside were three items: a DVD, a single sheet of A4 paper, and a photograph.

“Shit,” said Hewitt softly. “Shit, shit, shit.”

What transpired next would later be the source of much speculation and, for Simon Hewitt, a former political journalist who surely should have known better, no small amount of recrimination. Because instead of contacting London’s Metropolitan Police, as required by British law, Hewitt carried the envelope and its contents to his office at 12 Downing Street, located just two doors down from the prime minister’s official residence at Number Ten. After conducting his usual eight o’clock staff meeting, during which no mention was made of the items, he showed them to Jeremy Fallon, Lancaster’s chief of staff and political consigliere. Fallon was the most powerful chief of staff in British history. His official responsibilities included strategic planning and policy coordination across the various departments of government, which empowered him to poke his nose into any matter he pleased. In the press, he was often referred to as “Lancaster’s brain,” which Fallon rather liked and Lancaster privately resented.

Fallon’s reaction differed only in his choice of an expletive. His first instinct was to bring the material to Lancaster at once, but because it was a Wednesday he waited until Lancaster had survived the weekly gladiatorial death match known as Prime Minister’s Questions. At no point during the meeting did Lancaster, Hewitt, or Jeremy Fallon suggest handing the material over to the proper authorities. What was required, they agreed, was a person of discretion and skill who, above all else, could be trusted to protect the prime minister’s interests. Fallon and Hewitt asked Lancaster for the names of potential candidates, and he gave them only one. There was a family connection and, more important, an unpaid debt. Personal loyalty counted for much at times like these, said the prime minister, but leverage was far more practical.

Hence the quiet summons to Downing Street of Graham Seymour, the longtime deputy director of the British Security Service, otherwise known as MI5. Much later, Seymour would describe the encounter—conducted in the Study Room beneath a glowering portrait of Baroness Thatcher—as the most difficult of his career. He agreed to help the prime minister without hesitation because that was what a man like Graham Seymour did under circumstances such as these. Still, he made it clear that, were his involvement in the matter ever to become public, he would destroy those responsible.

Which left only the identity of the operative who would conduct the search. Like Lancaster before him, Graham Seymour had only one candidate. He did not share the name with the prime minister. Instead, using funds from one of MI5’s many secret operational accounts, he booked a seat on that evening’s British Airways flight to Tel Aviv. As the plane eased from the gate, he considered how best to make his approach. Personal loyalty counted for much at times like these, he thought, but leverage was far more practical.

3 (#ulink_f59b3825-7970-5c7e-bd88-5f15dcedda13)

JERUSALEM (#ulink_f59b3825-7970-5c7e-bd88-5f15dcedda13)

IN THE HEART of Jerusalem, not far from the Ben Yehuda Mall, was a quiet, leafy lane known as Narkiss Street. The apartment house at Number Sixteen was small, just three stories in height, and was partially concealed behind a sturdy limestone wall and a towering eucalyptus tree growing in the front garden. The uppermost flat differed from the others in the building only in that it had once been owned by the secret intelligence service of the State of Israel. It had a spacious sitting room, a tidy kitchen filled with modern appliances, a formal dining room, and two bedrooms. The smaller of the two bedrooms, the one meant for a child, had been painstakingly converted into a professional artist’s studio. But Gabriel still preferred to work in the sitting room, where the cool breeze from the open French doors carried away the stench of his solvents.

At the moment, he was using a carefully calibrated solution of acetone, alcohol, and distilled water, first taught to him in Venice by the master art restorer Umberto Conti. The mixture was strong enough to dissolve the surface contaminants and the old varnish but would do no harm to the artist’s original brushwork. Now he dipped a hand-fashioned cotton swab into the solution and twirled it gently over the upturned breast of Susanna. Her gaze was averted and she seemed only vaguely aware of the two lecherous village elders watching her bathe from beyond her garden wall. Gabriel, who was unusually protective of women, wished he could intervene and spare her the trauma of what was to come—the false accusations, the trial, the death sentence. Instead, he worked the cotton swab gently over the surface of her breast and watched as her yellowed skin turned a luminous white.

When the swab became soiled, Gabriel placed it in an airtight flask to trap the fumes. As he prepared another, his eyes moved slowly over the surface of the painting. At present, it was attributed only to a follower of Titian. But the painting’s current owner, the renowned London art dealer Julian Isherwood, believed it had come from the studio of Jacopo Bassano. Gabriel concurred—indeed, now that he had exposed some of the brushwork, he saw evidence of the master himself, especially in the figure of Susanna. Gabriel knew Bassano’s style well; he had studied his paintings extensively while serving his apprenticeship and had once spent several months in Zurich restoring an important Bassano for a private collector. On the final night of his stay, he had killed a man named Ali Abdel Hamidi in a wet alleyway near the river. Hamidi, a Palestinian master terrorist with much Israeli blood on his hands, had been posing as a playwright, and Gabriel had given him a death worthy of his literary pretensions.

Gabriel dipped the new swab into the solvent mixture, but before he could resume work he heard the familiar rumble of a heavy car engine in the street. He stepped onto the terrace to confirm his suspicions and then opened the front door an inch. A moment later Ari Shamron was perched atop a wooden stool at Gabriel’s side. He wore khaki trousers, a white oxford cloth shirt, and a leather jacket with an unrepaired tear in the left shoulder. His ugly spectacles shone with the light of Gabriel’s halogen work lamps. His face, with its deep cracks and fissures, was set in an expression of profound distaste.

“I could smell those chemicals the instant I stepped out of the car,” Shamron said. “I can only imagine the damage they’ve done to your body after all these years.”

“Rest assured it’s nothing compared to the damage you’ve done,” Gabriel replied. “I’m surprised I can still hold a paintbrush.”

Gabriel placed the moistened swab against the flesh of Susanna and twirled it gently. Shamron frowned at his stainless steel wristwatch, as though it were no longer keeping proper time.

“Something wrong?” asked Gabriel.

“I’m just wondering how long it’s going to take you to offer me a cup of coffee.”

“You know where everything is. You practically live here now.”

Shamron muttered something in Polish about the ingratitude of children. Then he nudged himself off the stool and, leaning heavily on his cane, made his way into the kitchen. He managed to fill the teakettle with tap water but appeared perplexed by the various buttons and dials on the stove. Ari Shamron had twice served as the director of Israel’s secret intelligence service and before that had been one of its most decorated field officers. But now, in old age, he seemed incapable of the most basic of household tasks. Coffeemakers, blenders, toasters: these were a mystery to him. Gilah, his long-suffering wife, often joked that the great Ari Shamron, if left to his own devices, would find a way to starve in a kitchen filled with food.

Gabriel ignited the stove and then resumed his work. Shamron stood in the French doors, smoking. The stench of his Turkish tobacco soon overwhelmed the pungent odor of the solvent.

“Must you?” asked Gabriel.

“I must,” said Shamron.

“What are you doing in Jerusalem?”

“The prime minister wanted a word.”

“Really?”

Shamron glared at Gabriel through a cloud of blue-gray smoke. “Why are you surprised the prime minister would want to see me?”

“Because—”

“I am old and irrelevant?” Shamron asked, cutting him off.

“You are unreasonable, impatient, and at times irrational. But you have never been irrelevant.”

Shamron nodded in agreement. Age had given him the ability to at least see his own shortcomings, even if it had robbed him of the time needed to remedy them.

“How is he?” asked Gabriel.

“As you might imagine.”

“What did you talk about?”

“Our conversation was wide ranging and frank.”

“Does that mean you yelled at each other?”

“I’ve only yelled at one prime minister.”

“Who?” asked Gabriel, genuinely curious.

“Golda,” answered Shamron. “It was the day after Munich. I told her we had to change our tactics, that we had to terrorize the terrorists. I gave her a list of names, men who had to die. Golda wanted none of it.”

“So you yelled at her?”

“It was not one of my finer moments.”

“What did she do?”

“She yelled back, of course. But eventually she came around to my way of thinking. After that, I put together another list of names, the names of the young men I needed to carry out the operation. All of them agreed without hesitation.” Shamron paused, and then added, “All but one.”

Gabriel silently placed the soiled swab into the airtight flask. It trapped the noxious fumes of the solvent but not the memory of his first encounter with the man they called the Memuneh, the one in charge. It had taken place just a few hundred yards from where he stood now, on the campus of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. Gabriel had just left a lecture on the paintings of Viktor Frankel, the noted German Expressionist who also happened to be his maternal grandfather. Shamron was waiting for him at the edge of a sunbaked courtyard, a small iron bar of a man with hideous spectacles and teeth like a steel trap. As usual, he was well prepared. He knew that Gabriel had been raised on a dreary agricultural settlement in the Valley of Jezreel and that he had a passionate hatred of farming. He knew that Gabriel’s mother, a gifted artist in her own right, had managed to survive the death camp at Birkenau but was no match for the cancer that ravaged her body. He knew, too, that Gabriel’s first language was German and that it remained the language of his dreams. It was all in the file he was holding in his nicotine-stained fingers. “The operation will be called Wrath of God,” he had said that day. “It’s not about justice. It’s about vengeance, pure and simple—vengeance for the eleven innocent lives lost at Munich.” Gabriel had told Shamron to find someone else. “I don’t want someone else,” Shamron had responded. “I want you.”

For the next three years, Gabriel and the other Wrath of God operatives stalked their prey across Europe and the Middle East. Armed with a .22-caliber Beretta, a soft-spoken weapon suitable for killing at close range, Gabriel personally assassinated six members of Black September. Whenever possible he shot them eleven times, one bullet for each Israeli butchered in Munich. When he finally returned home, his temples were the color of ash and his face was that of a man twenty years his senior. No longer able to produce original work, he went to Venice to study the craft of restoration. Then, when he was rested, he went back to work for Shamron. In the years that followed, he carried out some of the most fabled operations in the history of Israeli intelligence. Now, after many years of restless wandering, he had finally returned to Jerusalem. No one was more pleased by this than Shamron, who loved Gabriel as a son and treated the apartment on Narkiss Street as though it were his own. Once, Gabriel might have chafed under the pressure of Shamron’s constant presence, but no more. The great Ari Shamron was eternal, but the vessel in which his spirit resided would not last forever.

Nothing had done more damage to Shamron’s health than his relentless smoking. It was a habit he acquired as a young man in eastern Poland, and it had grown worse after he had come to Palestine, where he fought in the war that led to Israel’s independence. Now, as he described his meeting with the prime minister, he flicked open his old Zippo lighter and used it to ignite another one of his foul-smelling cigarettes.

“The prime minister is on edge, more so than usual. I suppose he has a right to be. The great Arab Awakening has plunged the entire region into chaos. And the Iranians are growing closer to realizing their nuclear dreams. At some point soon, they will enter a zone of immunity, making it impossible for us to act militarily without the help of the Americans.” Shamron closed his lighter with a snap and looked at Gabriel, who had resumed work on the painting. “Are you listening to me?”

“I’m hanging on your every word.”

“Prove it.”

Gabriel repeated Shamron’s last statement verbatim. Shamron smiled. He regarded Gabriel’s flawless memory as one of his finest accomplishments. He twirled the Zippo lighter in his fingertips. Two turns to the right, two turns to the left.

“The problem is that the American president refuses to lay down any hard-and-fast red lines. He says he will not allow the Iranians to build nuclear weapons. But that declaration is meaningless if the Iranians have the capability to build them in a short period of time.”

“Like the Japanese.”

“The Japanese aren’t ruled by apocalyptic Shia mullahs,” Shamron said. “If the American president isn’t careful, his two most important foreign policy achievements will be a nuclear Iran and the restoration of the Islamic caliphate.”

“Welcome to the post-American world, Ari.”

“Which is why I think we’re foolish to leave our security in their hands. But that’s not the prime minister’s only problem,” Shamron added. “The generals aren’t sure they can destroy enough of the program to make a military strike effective. And King Saul Boulevard, under the tutelage of your friend Uzi Navot, is telling the prime minister that a unilateral war with the Persians would be a catastrophe of biblical proportions.”

King Saul Boulevard was the address of Israel’s secret intelligence service. It had a long and deliberately misleading name that had very little to do with the true nature of its work. Even retired agents like Gabriel and Shamron referred to it as “the Office” and nothing else.

“Uzi is the one who sees the raw intelligence every day,” said Gabriel.

“I see it, too. Not all of it,” Shamron added hastily, “but enough to convince me that Uzi’s calculations about how much time we have might be flawed.”

“Math was never Uzi’s strong suit. But when he was in the field, he never made mistakes.”

“That’s because he rarely put himself in a position where it was possible to make a mistake.” Shamron lapsed into silence and watched the wind moving in the eucalyptus tree beyond the balustrade of Gabriel’s terrace. “I’ve always said that a career without controversy is not a proper career at all. I’ve had my share, and so have you.”

“And I have the scars to prove it.”

“And the accolades, too,” Shamron said. “The prime minister is concerned the Office is too cautious when it comes to Iran. Yes, we’ve inserted viruses into their computers and eliminated a handful of their scientists, but nothing has gone boom lately. The prime minister would like Uzi to produce another Operation Masterpiece.”

Masterpiece was the code name for a joint Israeli, American, and British operation that resulted in the destruction of four secret Iranian enrichment facilities. It had occurred on Uzi Navot’s watch, but within the corridors of King Saul Boulevard, it was regarded as one of Gabriel’s finest hours.

“Opportunities like Masterpiece don’t come along every day, Ari.”

“That’s true,” Shamron conceded. “But I’ve always believed that most opportunities are earned rather than bestowed. And so does the prime minister.”

“Has he lost confidence in Uzi?”

“Not yet. But he wanted to know whether I’d lost mine.”

“What did you say?”

“What choice did I have? I was the one who recommended him for the job.”

“So you gave him your blessing?”

“It was conditional.”

“How so?”

“I reminded the prime minister that the person I really wanted in the job wasn’t interested.” Shamron shook his head slowly. “You are the only man in the history of the Office who has turned down a chance to be the director.”

“There’s a first for everything, Ari.”

“Does that mean you might reconsider?”

“Is that why you’re here?”

“I thought you might enjoy the pleasure of my company,” Shamron countered. “And the prime minister and I were wondering whether you might be willing to do a bit of outreach to one of our closest allies.”

“Which one?”

“Graham Seymour dropped into town unannounced. He’d like a word.”

Gabriel turned to face Shamron. “A word about what?” he asked after a moment.

“He wouldn’t say, but apparently it’s urgent.” Shamron walked over to the easel and squinted at the pristine patch of canvas where Gabriel had been working. “It looks new again.”

“That’s the point.”

“Is there any chance you could do the same for me?”

“Sorry, Ari,” said Gabriel, touching Shamron’s deeply crevassed cheek, “but I’m afraid you’re beyond repair.”

4 (#ulink_8410f94f-bf5c-5c7d-a56f-a6a2d68c64d0)

KING DAVID HOTEL, JERUSALEM (#ulink_8410f94f-bf5c-5c7d-a56f-a6a2d68c64d0)

ON THE AFTERNOON of July 22, 1946, the extremist Zionist group known as the Irgun detonated a large bomb in the King David Hotel, headquarters of all British military and civilian forces in Palestine. The attack, a reprisal for the arrest of several hundred Jewish fighters, killed ninety-one people, including twenty-eight British subjects who had ignored a telephone warning to evacuate the hotel. Though universally condemned, the bombing would quickly prove to be one of the most effective acts of political violence ever committed. Within two years, the British had retreated from Palestine, and the modern State of Israel, once an almost unimaginable Zionist dream, was a reality.

Among those fortunate enough to survive the bombing was a young British intelligence officer named Arthur Seymour, a veteran of the wartime Double Cross program who had recently been transferred to Palestine to spy on the Jewish underground. Seymour should have been in his office at the time of the attack but was running a few minutes late after meeting with an informant in the Old City. He heard the detonation as he was passing through the Jaffa Gate and watched in horror as part of the hotel collapsed. The image would haunt Seymour for the remainder of his life and shape the course of his career. Virulently anti-Israeli and fluent in Arabic, he developed uncomfortably close ties to many of Israel’s enemies. He was a regular guest of Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser and an early admirer of a young Palestinian revolutionary named Yasir Arafat.

Despite his pro-Arab sympathies, the Office regarded Arthur Seymour as one of MI6’s most capable officers in the Middle East. And so it came as something of a surprise when Seymour’s only son, Graham, chose a career at MI5 rather than the more glamorous Secret Intelligence Service. Seymour the Younger, as he was known early in his career, served first in counterintelligence, working against the KGB in London. Then, after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rise in Islamic fanaticism, he was promoted to chief of counterterrorism. Now, as MI5’s deputy director, he had been forced to rely on his expertise in both disciplines. There were more Russian spies plying their trade in London these days than at the height of the Cold War. And thanks to mistakes by successive British governments, the United Kingdom was now home to several thousand Islamic militants from the Arab world and Asia. Seymour referred to London as “Kandahar on the Thames.” Privately, he worried that his country was sliding closer to the edge of a civilizational abyss.

Though Graham Seymour had inherited his father’s passion for pure espionage, he shared none of his disdain for the State of Israel. Indeed, under his guidance, MI5 had forged close ties with the Office and, in particular, with Gabriel Allon. The two men regarded themselves as members of a secret brotherhood who did the unpleasant chores no one else was willing to do and worried about the consequences later. They had fought for one another, bled for one another, and in some cases killed for one another. They were as close as two spies from opposing services could be, which meant they distrusted each other only a little.

“Is there anyone in this hotel who doesn’t know who you are?” Seymour asked, shaking Gabriel’s outstretched hand as though it belonged to someone he was meeting for the first time.

“The girl at reception asked if I was here for the Greenberg bar mitzvah.”

Seymour gave a discreet smile. With his pewter-colored locks and sturdy jaw, he looked the archetype of the British colonial baron, a man who decided important matters and never poured his own tea.

“Inside or out?” asked Gabriel.

“Out,” said Seymour.

They sat down at a table outside on the terrace, Gabriel facing the hotel, Seymour the walls of the Old City. It was a few minutes after eleven, the lull between breakfast and lunch. Gabriel drank only coffee but Seymour ordered lavishly. His wife was an enthusiastic but dreadful cook. For Seymour, airline food was a treat, and a hotel brunch, even from the kitchen of the King David, was an occasion to be savored. So, too, it seemed, was the view of the Old City.

“You might find this hard to believe,” he said between bites of his omelet, “but this is the first time I’ve ever set foot in your country.”

“I know,” Gabriel replied. “It’s all in your file.”

“Interesting reading?”

“I’m sure it’s nothing compared to what your service has on me.”

“How could it be? I am but a humble servant of Her Majesty’s Security Service. You, on the other hand, are a legend. After all,” Seymour added, lowering his voice, “how many intelligence officers can say they spared the world an apocalypse?”

Gabriel glanced over his shoulder and stared at the golden Dome of the Rock, Islam’s third-holiest shrine, sparkling in the crystalline Jerusalem sunlight. Five months earlier, in a secret chamber 167 feet beneath the surface of the Temple Mount, he had discovered a massive bomb that, had it detonated, would have brought down the entire plateau. He had also discovered twenty-two pillars from Solomon’s Temple of Jerusalem, thus proving beyond doubt that the ancient Jewish sanctuary, described in Kings and Chronicles, had in fact existed. Though Gabriel’s name never appeared in the press coverage of the momentous discovery, his involvement in the affair was well known in certain circles of the Western intelligence community. It was also known that his closest friend, the noted biblical archaeologist and Office operative Eli Lavon, had nearly died trying to save the pillars from destruction.

“You’re damn lucky that bomb didn’t go off,” Seymour said. “If it had, several million Muslims would have been on your borders in a matter of hours. After that …” Seymour’s voice trailed off.

“It would have been lights out on the enterprise known as the State of Israel,” Gabriel said, finishing Seymour’s thought for him. “Which is exactly what the Iranians and their friends in Hezbollah wanted to happen.”

“I can’t imagine what it must have been like when you saw those pillars for the first time.”

“To be honest, Graham, I didn’t have time to enjoy the moment. I was too busy trying to keep Eli alive.”

“How is he?”

“He spent two months in the hospital, but he looks almost as good as new. He’s actually back at work.”

“For the Office?”

Gabriel shook his head. “He’s digging in the Western Wall Tunnel again. I can arrange a private tour if you like. In fact, if you’re interested, I can show you the secret passage that leads directly into the Temple Mount.”

“I’m not sure my government would approve.” Seymour lapsed into silence while a waiter refilled their coffee cups. Then, when they were alone again, he said, “So the rumor is true after all.”

“Which rumor is that?”

“The one about the prodigal son finally returning home. It’s funny,” he added, smiling sadly, “but I always assumed you’d spend the rest of your life walking the cliffs of Cornwall.”

“It’s beautiful there, Graham. But England is your home, not mine.”

“Sometimes even I don’t feel at home there any longer,” Seymour said. “Helen and I recently purchased a villa in Portugal. Soon I’ll be an exile, like you used to be.”

“How soon?” asked Gabriel.

“Nothing’s imminent,” Seymour answered. “But eventually all good things must end.”

“You’ve had a great career, Graham.”

“Have I? It’s difficult to measure success in the security business, isn’t it? We’re judged on things that don’t happen—the secrets that aren’t stolen, the buildings that don’t explode. It can be a profoundly unsatisfying way of earning a living.”

“What are you going to do in Portugal?”

“Helen will attempt to poison me with her exotic cooking, and I will paint dreadful watercolor landscapes.”

“I never knew you painted.”

“For good reason.” Seymour frowned at the view as though it was far beyond the reach of his brush and palette. “My father would be spinning in his grave if he knew I was here.”

“So why are you here?”

“I was wondering whether you might be willing to find something for a friend of mine.”

“Does the friend have a name?”

Seymour made no reply. Instead, he opened his attaché case and withdrew an eight-by-ten photograph, which he handed to Gabriel. It showed an attractive young woman staring directly into the camera, holding a three-day-old copy of the International Herald Tribune.

“Madeline Hart?” asked Gabriel.

Seymour nodded. Then he handed Gabriel a sheet of A4 paper. On it was a single sentence composed in a plain sans serif typeface:

You have seven days, or the girl dies.

“Shit,” said Gabriel softly.

“I’m afraid it gets better.”

Coincidentally, the management of the King David had placed Graham Seymour, the only son of Arthur Seymour, in the same wing of the hotel that had been destroyed in 1946. In fact, Seymour’s room was just down the hall from the one his father had used as an office during the waning days of the British Mandate in Palestine. Arriving, they found the DO NOT DISTURB sign still hanging from the latch, along with a sack containing the JerusalemPost and Haaretz. Seymour led Gabriel inside. Then, satisfied the room had not been entered in his absence, he inserted a DVD into his notebook computer and clicked PLAY. A few seconds later Madeline Hart, missing British subject and employee of Britain’s governing party, appeared on the screen.

“I made love to Prime Minister Jonathan Lancaster for the first time at the Party conference in Manchester in October 2012 …”

5 (#ulink_9cc5b358-28c2-55cb-9c1c-9d7c3935e62e)

KING DAVID HOTEL, JERUSALEM (#ulink_9cc5b358-28c2-55cb-9c1c-9d7c3935e62e)

THE VIDEO WAS seven minutes and twelve seconds in length. Throughout, Madeline’s gaze remained fixed on a point slightly to the camera’s left, as if she were responding to questions posed by a television interviewer. She appeared frightened and fatigued as, reluctantly, she described how she had met the prime minister during one of his visits to the Party’s Millbank headquarters. Lancaster had expressed admiration for Madeline’s work and on two occasions invited her to Downing Street to personally brief him. It was at the end of the second visit when he admitted that his interest in Madeline was more than professional. Their first sexual encounter had been a hurried affair in a Manchester hotel room. After that, Madeline had been spirited into the Downing Street residence by an old friend of the prime minister, always when Diana Lancaster was away from London.

“And now,” said Seymour gloomily as the computer screen turned to black, “the prime minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is being punished for his sins with a crude attempt at blackmail.”

“There’s nothing crude about it, Graham. Whoever’s behind this knew the prime minister was involved in an extramarital affair. And then they managed to make his lover disappear without a trace from Corsica. They’re obviously extremely sophisticated.”

Seymour ejected the disk from the computer but said nothing.

“Who else knows?”

Seymour explained how the three items—the photograph, the note, and the DVD—had been left the previous morning on Simon Hewitt’s doorstep. And how Hewitt had transported them to Downing Street, where he showed them to Jeremy Fallon. And how Hewitt and Fallon had then confronted Lancaster in his office at Number Ten. Gabriel, a recent resident of the United Kingdom, knew the cast of characters well. Hewitt, Fallon, Lancaster: the holy trinity of British politics. Hewitt was the spin doctor, Fallon the master schemer and strategist, and Lancaster the raw political talent.

“Why did Lancaster choose you?” asked Gabriel.

“Our fathers worked together in the intelligence service.”

“Surely there’s more to it than that.”

“There is,” Seymour admitted. “His name is Siddiq Hussein.”

“I’m afraid it doesn’t ring a bell.”

“That’s not surprising,” Seymour said. “Because, thanks to me, Siddiq disappeared down a black hole several years ago, never to be seen or heard from again.”

“Who was he?”

“Siddiq Hussein was a Pakistani-born resident of Tower Hamlets in East London. He popped up on our radar screens after the bombings in 2007 when we finally came to our senses and started pulling Islamic radicals off the streets. You remember those days,” Seymour said bitterly. “The days when the leftists and the media insisted we do something about the terrorists in our midst.”

“Go on, Graham.”

“Siddiq was hanging around with known extremists at the East London Mosque, and his mobile phone number kept appearing in all the wrong places. I gave a copy of his file to Scotland Yard, but the Counterterrorism Command said there wasn’t enough evidence to move against him. Then Siddiq did something that gave me a chance to take care of the problem on my own.”

“What was that?”

“He booked an airline ticket to Pakistan.”

“Big mistake.”

“Fatal, actually,” said Seymour darkly.

“What happened?”

“We followed him to Heathrow and made sure he boarded his flight to Karachi. Then I placed a quiet call to an old friend in Langley, Virginia. I believe you know him well.”

“Adrian Carter.”

Seymour nodded. Adrian Carter was the director of the CIA’s National Clandestine Service. He oversaw the Agency’s global war on terror, including its once-secret programs to detain and interrogate high-value operatives.

“Carter’s team watched Siddiq in Karachi for three days,” Seymour continued. “Then they threw a bag over his head and put him on the first black flight out of the country.”

“Where did they take him?”

“Kabul.”

“The Salt Pit?”

Seymour nodded slowly.

“How long did he last?”

“That depends on whom you ask. According to the Agency’s account of the events, Siddiq was found dead in his cell ten days after arriving in Kabul. His family alleged in a lawsuit that he died while being tortured.”

“What does this have to do with the prime minister?”

“When the lawyers representing Siddiq’s family asked for all MI5 documents related to his case, Lancaster’s government refused to release them on grounds it would damage British national security. He saved my career.”

“And now you’re going to repay that debt by trying to save his neck?” When Seymour made no reply, Gabriel said, “This is going to end badly, Graham. And when it does, your name will feature prominently in the inevitable inquest.”

“I’ve made it clear that, if that happens, I’ll take everyone down with me, including Lancaster.”

“I never had you figured for the naive type, Graham.”

“I’m anything but.”

“So walk away. Go back to London and tell your prime minister to go before the cameras with his wife at his side and make a public appeal for the kidnappers to release the girl.”

“It’s too late for that. Besides,” Seymour added, “perhaps I’m a bit old-fashioned, but I don’t like it when people try to blackmail the leader of my country.”

“Does the leader of your country know you’re in Jerusalem?”

“Surely you jest.”

“Why me?”

“Because if MI5 or the intelligence service tries to find her, it will leak, just the way Siddiq Hussein leaked. You’re also damn good at finding things,” Seymour added quietly. “Ancient pillars, stolen Rembrandts, secret Iranian enrichment facilities.”

“Sorry, Graham, but—”

“And because you owe Lancaster, too,” Seymour said, cutting him off.

“Me?”

“Who do you think allowed you to take refuge in Cornwall under a false name when no other country would have you? And who do you think allowed you to recruit a British journalist when you needed to penetrate Iran’s nuclear supply chain?”

“I didn’t realize we were keeping score, Graham.”

“We’re not,” said Seymour. “But if we were, you would surely be trailing in the match.”

The two men lapsed into an uncomfortable silence, as though embarrassed by the tone of the exchange. Seymour looked at the ceiling, Gabriel at the note.

You have seven days, or the girl dies …

“Rather vague, don’t you think?”

“But highly effective,” said Seymour. “It certainly got Lancaster’s attention.”

“No demands?”

Seymour shook his head. “Obviously, they want to name their price at the last minute. And they want Lancaster to be so desperate to save his political hide, he’ll agree to pay it.”

“How much is your prime minister worth these days?”

“The last time I had a peek at his bank accounts,” Seymour said facetiously, “he had upward of a hundred million.”

“Pounds?”

Seymour nodded. “Jonathan Lancaster made millions in the City, inherited millions from his family, and married millions in the form of Diana Baldwin. He’s a perfect target, a man with more money than he needs and a great deal to lose. Diana and the children live within the security bubble of Number Ten, which means it would be almost impossible for a kidnapper to get them. But Lancaster’s mistress …” Seymour’s voice trailed off. Then he added, “A mistress is an altogether different matter.”

“I don’t suppose Lancaster has mentioned any of this to his wife?”

Seymour made a gesture with his hands to indicate he wasn’t privy to the inner workings of the Lancaster marriage.

“Have you ever worked a kidnapping case, Graham?”

“Not since Northern Ireland. And those were all IRA-related.”

“Political kidnappings are different from criminal kidnappings,” Gabriel said. “Your average political kidnapper is a rational fellow. He wants comrades released from prison or a policy changed, so he grabs an important politician or a busload of schoolchildren and holds them hostage until his demands are met. But a criminal wants only money. And if you pay him, it makes him want more money. So he keeps asking for money until he thinks there’s none left.”

“Then I suppose that leaves us only one option.”

“What’s that?”

“Find the girl.”

Gabriel walked to the window and stared across the valley toward the Temple Mount; and for an instant he was back in a secret cavern 167 feet beneath the surface, holding Eli Lavon as his blood pumped into the heart of the holy mountain. During the long nights Gabriel had spent next to Lavon’s hospital bed, he had vowed to never again set foot on the secret battlefield. But now an old friend had risen from the depths of his tangled past to request a favor. And once more Gabriel was struggling to find the words to send him away empty-handed. As the only child of Holocaust survivors, it was not in his nature to disappoint others. He made accommodations for them, but he rarely told them no.

“Even if I’m able to find her,” he said after a moment, “the kidnappers will still have the video of her confessing an affair with the prime minister.”

“But that video will have a rather different impact if the English rose is safely back on English soil.”

“Unless the English rose decides to tell the truth.”

“She’s a Party loyalist. She wouldn’t dare.”

“You have no idea what they’ve done to her,” Gabriel responded. “She could be an entirely different person by now.”

“True,” said Seymour. “But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. This conversation is meaningless unless you and your service undertake an operation to find Madeline Hart on my behalf.”

“I don’t have the authority to place my service at your disposal, Graham. It’s Uzi’s decision to make, not mine.”

“Uzi’s already given his approval,” Seymour said flatly. “So has Shamron.”

Gabriel glared at Seymour in disapproval but said nothing.

“Do you really think Ari Shamron would have let me within a mile of you without knowing why I was in town?” Seymour asked. “He’s very protective of you.”

“He has a funny way of showing it. But I’m afraid there’s one person in Israel who’s more powerful than Shamron, at least when it comes to me.”

“Your wife?”

Gabriel nodded.

“We have seven days, or the girl dies.”

“Six days,” said Gabriel. “The girl could be anywhere in the world, and we don’t have a single clue.”

“That’s not entirely true.”

Seymour reached into his briefcase and produced two Interpol photographs of the man with whom Madeline Hart had lunched on the afternoon of her disappearance. The man whose shoes left no marks. The forgotten man.

“Who is he?” asked Gabriel.

“Good question,” said Seymour. “But if you can find him, I suspect you’ll find Madeline Hart.”

6 (#ulink_1af2bb3a-7948-5063-a5ba-6e6c15a172a0)

ISRAEL MUSEUM, JERUSALEM (#ulink_1af2bb3a-7948-5063-a5ba-6e6c15a172a0)

GABRIEL TOOK A single item from Graham Seymour, the photograph of a captive Madeline Hart, and carried it westward across Jerusalem, to the Israel Museum. After leaving his car in the staff parking lot, a privilege only recently granted to him, he made his way through the soaring glass entrance hall to the room that housed the museum’s collection of European art. In one corner hung nine Impressionist paintings that had once been in the possession of a Swiss banker named Augustus Rolfe. A placard described the long journey the paintings had taken from Paris to this spot—how they had been looted by the Nazis in 1940, and how they were later transferred to Rolfe in exchange for services rendered to German intelligence. The placard made no mention of the fact that Gabriel and Rolfe’s daughter, the renowned violinist Anna Rolfe, had discovered the paintings in a Zurich bank vault—or that a consortium of Swiss businessmen had hired a professional assassin from Corsica to kill them both.

In the adjoining gallery hung works by Israeli artists. There were three canvases by Gabriel’s mother, including a haunting depiction of the death march from Auschwitz in January 1945 that she had painted from memory. Gabriel spent several moments admiring her draftsmanship and brushwork before heading outside into the sculpture garden. At the far end stood the beehive-shaped Shrine of the Book, repository of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Next to it was the museum’s newest structure, a modern glass-and-steel building, sixty cubits long, twenty cubits wide, and thirty cubits high. For now, it was cloaked in an opaque construction tarpaulin that rendered its contents, the twenty-two pillars of Solomon’s Temple, invisible to the outside world.

There were well-armed security men standing along both sides of the building and at its entrance, which faced east, as had Solomon’s original Temple. It was just one element of the exhibit that had made it arguably the most controversial curatorial project the world had ever known. Israel’s ultra-Orthodox haredim had denounced the exhibit as an affront to God that would ultimately lead to the destruction of the Jewish state, while in Arab East Jerusalem the keepers of the Dome of the Rock declared the pillars an elaborate hoax. “There was never an actual Temple on the Temple Mount,” the grand mufti of Jerusalem wrote in an op-ed published in the New York Times, “and no museum exhibit will ever change that fact.”

Despite the fierce religious and political battles raging around the exhibit, it had progressed with remarkable speed. Within a few weeks of Gabriel’s discovery, architectural plans had been approved, funds raised, and ground broken. Much of the credit belonged to the project’s Italian-born director and chief designer. In public she was referred to by her maiden name, which was Chiara Zolli. But all those associated with the project knew that her real name was Chiara Allon.

The pillars were arranged in the same manner in which Gabriel had found them, in two straight columns separated by approximately twenty feet. One, the tallest, was blackened by fire—the fire the Babylonians had set the night they brought low the Temple that the ancient Jews regarded as the dwelling place of God on earth. It was the pillar Eli Lavon had clung to as he was near death, and it was there that Gabriel found Chiara. She was holding a clipboard in one hand and with the other was gesturing toward the glass ceiling. She wore faded jeans, flat-soled sandals, and a sleeveless white pullover that clung tightly to the curves of her body. Her bare arms were very dark from the Jerusalem sun; her riotous long hair was full of golden highlights. She looked astonishingly beautiful, thought Gabriel, and far too young to be the wife of a battered wreck like him.

Overhead two technicians were making adjustments to the exhibit’s lighting while Chiara supervised from below. She spoke to them in Hebrew, with a distinct Italian accent. The daughter of the chief rabbi of Venice, she had spent her childhood in the insular world of the ancient ghetto, leaving just long enough to earn a master’s degree in Roman history from the University of Padua. She returned to Venice after graduation and took a job at the small Jewish museum in the Campo del Ghetto Nuovo, and there she might have remained forever had an Office talent spotter not noticed her during a visit to Israel. The talent spotter introduced himself in a Tel Aviv coffeehouse and asked Chiara whether she was interested in doing more for the Jewish people than working in a museum in a dying ghetto.

After spending a year in the Office’s secretive training program, Chiara returned to Venice, this time as an undercover agent of Israeli intelligence. Among her first assignments was to covertly watch the back of a wayward Office assassin named Gabriel Allon, who had come to Venice to restore Bellini’s San Zaccaria altarpiece. She revealed herself to him a short time later in Rome, after an incident involving gunplay and the Italian police. Trapped alone with Chiara in a safe flat, Gabriel had wanted desperately to touch her. He had waited until the case was resolved and they had returned to Venice. There, in a canal house in Cannaregio, they made love for the first time, in a bed prepared with fresh linen. It was like making love to a figure painted by the hand of Veronese.

Now the figure turned her head and, noticing Gabriel’s presence for the first time, smiled. Her eyes, wide and oriental in shape, were the color of caramel and flecked with gold, a combination that Gabriel had never been able to accurately reproduce on canvas. It had been many months since Chiara had agreed to sit for him; the exhibit had left her with little time for anything else. It was a distinct change in the pattern of their marriage. Usually, it was Gabriel who was consumed by a project, be it a painting or an operation, but now the roles were reversed. Chiara, a natural organizer who was meticulous in all things, had thrived under the intense pressure of the exhibit. But secretly Gabriel was looking forward to the day he could have her back.

She walked to the next pillar and examined the way the light was falling across it. “I called the apartment a few minutes ago,” she said, “but there was no answer.”

“I was having brunch with Graham Seymour at the King David.”

“How lovely,” she said sardonically. Then, still studying the pillar, she asked, “What’s in the envelope?”

“A job offer.”

“Who’s the artist?”

“Unknown.”

“And the subject matter?”

“A girl named Madeline Hart.”

Gabriel returned to the sculpture garden and sat on a bench overlooking the tan hills of West Jerusalem. A few minutes later Chiara joined him. A soft autumnal wind moved in her hair. She brushed a stray tendril from her face and then crossed one long leg over the other so that her sandal dangled from her suntanned toes. Suddenly, the last thing Gabriel wanted to do was to leave Jerusalem and go looking for a girl he didn’t know.

“Let’s try this again,” she said at last. “What’s in the envelope?”

“A photograph.”

“What kind of photograph?”

“Proof of life.”

Chiara held out her hand. Gabriel hesitated.

“Are you sure?”

When Chiara nodded, Gabriel surrendered the envelope and watched as she lifted the flap and removed the print. As she examined the image, a shadow fell across her face. It was the shadow of a Russian arms dealer named Ivan Kharkov. Gabriel had taken everything from Ivan: his business, his money, his wife and children. Then Ivan had retaliated by taking Chiara. The operation to rescue her was the bloodiest of Gabriel’s long career. Afterward, he had killed eleven of Ivan’s operatives in retaliation. Then, on a quiet street in Saint-Tropez, he had killed Ivan, too. Yet even in death, Ivan remained a part of their lives. The ketamine injections his men had given Chiara had caused her to lose the child she was carrying. Untreated, the miscarriage had damaged her ability to conceive. Privately, she had all but given up hope she would ever become pregnant again.

She returned the photograph to the envelope and the envelope to Gabriel. Then she listened intently as he described how the case had ended up in Graham Seymour’s lap, then in his.

“So the British prime minister is forcing Graham Seymour to do his dirty work for him,” she said when Gabriel had finished, “and Graham is doing the same to you.”

“He’s been a good friend.”

Chiara’s face was expressionless. Her eyes, usually a reliable window into her thoughts, were concealed behind sunglasses.

“What do you suppose they want?” she asked after a moment.

“Money,” said Gabriel. “They always want money.”