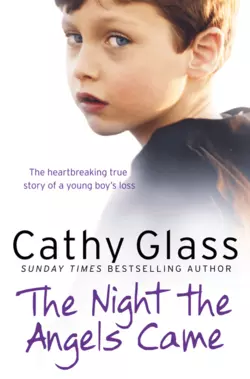

The Night the Angels Came

Cathy Glass

A new memoir from Sunday Times and New York Times bestselling author Cathy Glass.When Cathy receives a call about a terminally ill widower terrified of leaving his son all alone in the world, she is wracked with sadness and indecision. Can she risk exposing her own young children to a little boy on the brink of bereavement?Eight year old Michael is part of a family of two, but with his beloved father given only months to live and his mother having died when he was a toddler, he could soon become an orphan. Will Cathy’s own young family be able to handle a child in mourning? To Cathy’s surprise, her children insist that this boy deserves to be as happy as they are, prompting Cathy to welcome Michael into her home.A cheerful and carefree new member of the family, Michael devotedly prays every night, believing that when the time is right, angels will come and take his Daddy to be with his Mummy in heaven. However, incredibly, in the weeks that pass, the bond between Cathy’s family, Michael and his kind and loving father Patrick grows. Even more promising, Patrick is looking healthier than he’s done in weeks.But just as they are settling into a routine of blissful normality, an unexpected and disastrous event shatters the happy group, shaking Cathy to the core. Cathy can only hope that her family and Michael’s admirable faith will keep him strong enough to rebuild his life.

Cathy Glass

SUNDAY TIMES BESTSELLING AUTHOR

The Night the

Angels Came

The heartbreaking true

story of a young boy's loss

Copyright

Certain details, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect the family’s privacy.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published by HarperElement 2011

Copyright © Cathy Glass 2011

Cathy Glass asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007442621

Ebook Edition © JULY 2011 ISBN: 9780007445691

Version 2016-08-15

Contents

Cover (#u908ffb0e-0080-52bf-881b-f6ce0e1e53ce)

Title Page (#udb280321-f23a-52a6-afbe-f02192e4f29c)

Copyright

Preface

Chapter One - It’s a Cruel World

Chapter Two - Proud of My Children

Chapter Three - Are You Going to Die Soon?

Chapter Four - So Brave Yet So Ill

Chapter Five - Treasure

Chapter Six - Lonely and Afraid

Chapter Seven - Comfortable

Chapter Eight - Michael’s Daddy

Chapter Nine - A Prayer Answered

Chapter Ten - A Child Again

Chapter Eleven - Friends and Neighbours

Chapter Twelve - Good and Bad News

Chapter Thirteen - An Evening Out

Chapter Fourteen - ‘May Joy and Peace Surround You’

Chapter Fifteen - Boyfriend

Chapter Sixteen - An Empty House

Chapter Seventeen - Attached

Chapter Eighteen - News and No News

Chapter Nineteen - The Power of Prayer

Chapter Twenty - Hospital

Chapter Twenty-One - Support

Chapter Twenty-Two - Improving

Chapter Twenty-Three - Worry Mode

Chapter Twenty-Four - The Night Sky

Chapter Twenty-Five - Staying Positive

Chapter Twenty-Six - A Few Days’ Rest

Chapter Twenty-Seven - Premonition

Chapter Twenty-Eight - Time with Dad

Chapter Twenty-Nine - The Stars Glow Brightly

Chapter Thirty - The Meeting

Chapter Thirty-One - The Right Decision

Chapter Thirty-Two - Heaven

Chapter Thirty-Three - Leaving Michael

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Exclusive sample chapter (#litres_trial_promo)

Cathy Glass (#litres_trial_promo)

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Preface (#ulink_d1e01323-dfa8-5ad8-8854-2af24a8867e2)

Children usually come into foster care as a result of abuse or severe neglect. Very occasionally, and sadly, it is as a result of one or both parents being very ill or even dying. This is the true story of Michael, whose courage, faith and strength in the face of so much sorrow will stay in the hearts of my family and me for ever.

Chapter One It’s a Cruel World (#ulink_b38e5c61-f426-5ca2-a7cd-00c43bcd0988)

‘Cathy,’ Jill said quietly, ‘I need to ask you something, and you must feel you can say no.’ ‘Sure, go ahead, Jill. I’m good at saying no,’ I returned light-heartedly.

Jill gave a small laugh but I now realized she sounded subdued – not her usual cheerful self. Jill is my support social worker from Homefinders, the agency I foster for, and we get on very well.

‘Cathy,’ she continued, ‘we need a foster home for a little boy called Michael. He’s just eight. He has been looked after by his father for the last six years since his mother died when Michael was just two.’ Jill paused, as though steeling herself for something she had to tell me, and I assumed it would be that the child had been badly neglected or abused, or that the father had a new partner and no longer wanted the child. I’d answered the telephone in the sitting room and I now sat on the sofa, ready to hear the details of the little boy’s suffering, which would still shock me even after hearing many similar stories in the nine years I’d been fostering. However, what Jill told me shocked me in an entirely different way.

‘Cathy,’ Jill said sombrely, ‘Michael’s father, Patrick, is dying. He has contacted the social services and asked if a carer can be found to look after Michael when he’s no longer able to.’ ‘

Jill paused and waited for my reaction. I didn’t know what to say. ‘Oh, I see,’ I said lamely, as images and thoughts flashed through my mind and I grappled with the implications of what Jill was telling me.

‘Patrick loves his son deeply,’ Jill continued, ‘and he has brought him up very well. Patrick has been battling against cancer for two years but the chemo has been stopped now and he’s on palliative care only. He’s very thin and weak, and realizes it won’t be long before he has to go into a hospital or hospice. He has asked if Michael can get to know his carer before he goes to live with them when Patrick has to go into hospital.’

‘I see,’ I said again, quietly. ‘How very, very sad. And there’s no one in Michael’s extended family who can look after him?’ Which is usually considered the next best option for a child whose parents can’t look after them, and what would have happened in my family if anything had happened to me.

‘Apparently not,’ Jill said. ‘Both sets of grandparents are deceased and Patrick is an only child. There’s an aunt who lives in Wales but Patrick has told the social worker they weren’t close. She hasn’t seen Michael since he was a baby and Patrick doesn’t think she will want to look after him. The social services will obviously be making more enquiries about the extended family – Patrick originally came from Ireland. But that will take time, and Patrick doesn’t have much time.’

‘How long does he have?’ I said, hardly daring to ask.

‘The doctors have given him about three months.’

I fell silent and Jill was quiet too. It was one of the saddest reasons for a child coming into foster care I’d ever heard of. ‘Does Michael know how ill his father is?’ I asked at length.

‘I’m not sure. He certainly knows his dad is very ill but I don’t know if it’s been explained to him that he’s dying. I’ll need to find out and also what counselling has been offered. Obviously, Cathy, this is a huge undertaking and I’m well aware of the commitment and emotional drain on you and your family if you agree to go ahead. Not many would want to take this on. It’s bad enough if someone you know dies, but you don’t go looking for bereavement.’ She gave a small dry laugh.

I was silent again and I gazed through the French windows at the garden, which was now awash with spring flowers. Bright yellow daffodils mingled with blue and white hyacinths against a backdrop of fresh green grass. It seemed a cruel irony that as nature was bursting into life for another year so a life was slowly ending. And while I didn’t know Michael or his father, my heart was already going out to them, especially that poor little boy who was about to lose his father and be left completely alone in the world.

‘What we’re looking for,’ Jill clarified, ‘is a carer who will get to know Michael while his father is still able to look after him, then foster him when his father goes into hospital or a hospice. Obviously if a relative isn’t found who can give Michael a permanent home then we will need a long-term foster placement, but we’ll cross that bridge when we come to it. His father has said he would like to meet the carer first, without Michael present, to discuss his son’s needs, routine, likes and dislikes, which is sensible. The social worker will set up that meeting straight away.’

‘Jill,’ I said, stopping her from going any further, ‘I need to think about this. I mean it’s not straightforward fostering, is it? Apart from the huge emotional commitment I’m also mindful that Adrian and Paula are still coming to come to terms with their father leaving us last year. I’m not sure I can put them through this now. Adrian is the same age as Michael and sensitive; he’s bound to feel Michael’s loss personally. I don’t think I have the right to upset my family more.’

‘I completely understand,’ Jill said. ‘I wasn’t even sure I should ask you.’ At that moment I felt like saying: ‘I wish you hadn’t’, because now I knew about Michael and his father I felt I had a responsibility towards them and I knew it was going to be difficult for me to say no.

‘When do you want my answer by?’ I asked Jill.

‘Tomorrow, please. Can you sleep on it and let me know?’

‘Yes, I will. I don’t know whether I should discuss it with Adrian and Paula. Paula is only four: she doesn’t understand about dying.’

‘Do any of us?’ Jill said quietly. And I remembered she’d lost her own brother the year before.

‘It can be a cruel world sometimes,’ I said. ‘Let me think about it, Jill, and I’ll get back to you.’

‘Thanks, Cathy. Sorry if I’ve placed you in an awkward position. I know it’s difficult.’

We said goodbye and I hung up. I stayed where I was on the sofa and stared unseeing across the room. I thought of Patrick raising his little boy alone after his wife’s death and the strong bond that would have resulted from there being just the two of them. I could imagine the terror Patrick must have felt when the doctors told him he had cancer; it’s a single parent’s worst nightmare – the prospect of leaving your child orphaned. I marvelled at the courage and strength Patrick must have shown in dealing with the gruelling chemotherapy while looking after Michael. How he’d found the inner resources to come to terms with his dying and concentrate on making arrangements to have his son looked after when he was no longer able to I didn’t know. What incredible courage, what sadness. I wouldn’t have done so well, I was sure. But could I help Michael and his father? Did I have the right to bring all their sadness into my house? Did I want to? At that moment I knew I didn’t. Standing, I wiped a tear from my eye, and left the room to busy myself with some housework to take my mind off the great sadness I had just heard.

Chapter Two Proud of My Children (#ulink_de5a4849-b3ca-5e0b-9307-1d8c5704ab08)

That afternoon when I met Adrian from school and then collected Paula from the friend she’d been playing with for the afternoon, I gave them an extra big hug and held them close. Life is so short and precious, but sometimes it takes a tragic reminder of just how fragile life is for us to really appreciate our loved ones and make the most of every day.

The April afternoon was still warm and I suggested we go to the park rather than straight home. Adrian and Paula happily agreed. Clearly other mothers had had the same idea, for when we arrived at the park it was busy, especially in the children’s play area. Adrian ran over to the large slide while I went with Paula into the gated area for under-fives. I stood to one side and watched her as she ran around and then had goes on the little roundabout and rocking horse; then she called me to help her into a swing. As I lifted Paula in I heard Adrian shout, ‘Look, Mum!’

I looked over to the adjacent play area, where Adrian was on the bigger swings, as usual working the swing as high as it would go. He wanted me to admire his daring feat. I smiled and nodded my appreciation of his courage, then called my usual warning, ‘Hold on tight!’, which made him work the swing even higher. But that’s Adrian, and I guess boys in general.

Paula liked a more leisurely and genteel swing and as I pushed her I kept an eye on Adrian. He had left the swing, having jumped off while it was still moving, and was now on the rope ladder that was part of the mini assault course. My thoughts went again to Michael, as they had been doing on and off all afternoon, since Jill’s phone call. Was Michael still able to enjoy simple pleasures like running free and playing in a park, I wondered, or had his life closed in to the illness of his father? With no immediate family to share the burden and help out, Michael’s life must surely centre around his father’s condition, especially now he was so very ill. I looked again at Adrian and for a horrendous second my thoughts flashed to a picture of him being told I was terminally ill. I shuddered and changed direction, and thought instead about the meeting Patrick had requested with the foster carer. I was sure I couldn’t do it. Not meet a dying man and discuss looking after his son when he was no longer able to. Perhaps if I’d had a strong religious faith and sincerely believed Patrick was going on to a better life it would have been easier, but my faith wasn’t that strong. Like many, I believed in something but I wasn’t sure what, and while I hoped for a life after death I wasn’t wholly convinced. Death, therefore, held a shocking finality for me and was something I avoided contemplating at all costs.

By the time we got home, despite a pleasant hour in the park, I was feeling pretty down and a failure for not being able to offer to look after Michael. Then something strange happened, portentous in its timing – a sign, almost.

Adrian and Paula were watching children’s television while I made dinner. I could hear the dialogue on the television from the kitchen. It was an episode in a drama series – the children’s equivalent of adult soap. It dealt with everyday issues as well as family crises. So far the series had covered a new baby in the family, a visit to the doctor, going into hospital, parents divorcing and a parent drinking too much. Now, to my amazement, it appeared to be dealing with the death of a loved one. I left the dinner cooking and joined the children on the sofa. Admittedly it wasn’t a parent dying but a grandparent, but the timing of this episode didn’t escape me. It showed the family visiting Grandpa while he was in hospital, him ‘drifting comfortably into an endless sleep’, followed by the funeral and him ‘being laid to rest’. While the relatives were upset that they would not be seeing Grandpa again they rejoiced in having known him. They shared their special memories and his adult daughter said, ‘He will live for ever in our memory’, so the programme ended on a very positive note.

I returned to the kitchen deep in thought and finished cooking the dinner. Despite the programme I was no more convinced I had what it took to see Michael through his father dying, and indeed if I should. As I’d said to Jill, Adrian and Paula didn’t need any more sadness after their father leaving, and it would be impossible that they wouldn’t become involved. Then, as we ate, I decided to reverse the decision I’d made earlier – not to discuss Michael’s situation with Adrian and Paula – and gently sound them out. It was, after all, their home Michael would be coming into and their lives he would be part of.

‘You know the fostering we do?’ I said lightly, introducing the subject.

‘Yes,’ Paula said. Adrian nodded.

‘Are you both happy to continue and have another child come to live with us for a while?’ It was a question I asked them from time to time and I didn’t automatically assume they wanted to continue fostering.

Adrian nodded again, more interested in his dinner than what I was saying, while Paula glanced up at me furtively, hoping I wouldn’t notice she was stacking her peas into a pile rather than eating them.

‘Have a few,’ I said, referring to the peas. ‘You need to eat some veg.’ Paula had recently gone off anything green (which obviously included most vegetables) after her best friend had told her caterpillars were green so they could hide in vegetables and she’d found a caterpillar on her plate hiding in some broccoli. ‘Good girl,’ I said, as she stabbed one pea on to her fork. ‘And you’re happy to continue fostering as well?’

‘Yes, I like it,’ Paula confirmed.

Now I knew that all things being equal they were happy to foster another child, I felt more confident in talking specifically about Michael’s situation.

‘I had a phone call from Jill earlier today,’ I began, ‘about a little boy called Michael who will be needing a foster home shortly.’

‘A boy, great!’ Adrian said, without waiting for further details. ‘How old is he?’

‘Same age as you – eight.’

‘Fantastic! Someone to play with at home.’

‘That’s not fair,’ Paula moaned. ‘I want a girl, my age.’

‘I’m afraid I can’t put in an order for a specific type of child,’ I said. ‘It’s a case of who needs a home,’ which they knew really. ‘And in the past you’ve all got along, whatever the age of the child, boy or girl, and even with the teenagers.’

‘When’s he coming?’ Adrian said, completely won over by the prospect of having a boy his own age come to stay, while Paula gingerly lifted another pea on to her fork and scanned it for any signs of wildlife.

‘I’m not sure he is coming to us yet,’ I said carefully. ‘Jill’s asked me to think about what she’s told me because it’s a difficult decision to make. You see, Michael’s father is very ill and he won’t be able to look after Michael for much longer, which is why he will need a foster home. But I’m not sure Michael coming to live with us is right for our family.’

Adrian looked at me quizzically. ‘Surely he can stay with us while his father gets better?’

I felt anxiety creep up my spine as I steeled myself to explain. ‘Unfortunately Michael’s father is very, very ill and I’m afraid he is not likely to get better. You know the programme you’ve just been watching?’ I glanced at them both. ‘About the grandpa dying? Well, I’m afraid that’s what is likely to happen to Michael’s father.’

Adrian had now stopped eating and was staring at me across the dining table, appreciating the implications of what I was saying. ‘His father is dying and Michael is my age?’ he asked. ‘His dad can’t be very old.’

‘No, he’s not. It’s dreadfully sad.’

‘His dad can only be your age,’ Adrian clarified, clearly shocked.

I nodded.

‘Can’t his mum look after him?’

Adrian asked. ‘Unfortunately Michael’s mother died when he was little.’ Adrian continued to stare at me, his little face serious and deeply saddened, while Paula, so innocent I could have wept, said, ‘Don’t worry: the doctors will make Michael’s daddy better.’

I smiled sadly. ‘Love, sometimes people get so very ill that the doctors do all they can, and give them lots of medicine, but in the end they can’t make them better.’

‘And sometimes doctors are wrong,’ Adrian put in forcefully. ‘There was a guy on the news last week who was told by his doctors he had only six months to live, and that was ten years ago!’

I smiled at him. ‘Yes, sometimes they do get it wrong, and make the wrong diagnosis,’ I agreed, ‘but not often.’

‘So the doctors might be wrong now,’ Paula put in, feeling she should contribute something but not fully understanding the discussion. Adrian nodded.

‘They might be wrong, but it’s not very likely. Michael’s father is very ill,’ I said. While I would have liked nothing more than to believe a misdiagnosis was an option, it would have been wrong of me to give them false hope.

We all quietly returned to our food but without our previous enthusiasm, and at that moment I knew I should have just said no to Jill and waited for the next child who needed a foster home. ‘Anyway,’ I said after a while, ‘I think I will tell Jill that we feel very sorry for Michael but we can’t look after him.’

‘Why?’ Adrian asked.

‘Because it would be too sad for us. Too much to cope with after … everything else.’

‘You mean Dad going?’

‘Well, yes, and having to be part of Michael’s sadness. I don’t want to be sad: I like to be happy.’

‘I’m sure Michael does too,’ Adrian said bluntly. I met his gaze and in that look I saw not an eight-year-old boy but the wisdom of a man. ‘I think Michael should come here,’ he said. ‘We can help him. Paula and I know what it’s like to lose your dad. I know divorce is different – we can still see our dad sometimes – but when Dad packed all his things and left, and stopped living with us, in some ways it felt like he’d died. I think because Paula and I have been through that it will help us understand how Michael is feeling when he’s very sad.’

It was at times like this I felt so proud of my children and also truly humbled. I felt my eyes fill.

‘And you think the same?’ I asked, turning to Paula.

She nodded. ‘We can help Michael when he cries about his daddy.’

‘Did you cry a lot after your daddy left?’ I asked.

Paula nodded. ‘At night in bed, so you couldn’t see.’

It was a moment before I could find my voice to speak. ‘You should have told me,’ I said, putting my arm around Paula and giving her a hug. ‘Thank you both for explaining how you feel. Now I’ve got to do some careful thinking and decide if I have what it takes to help Michael.’

‘You have, Mum,’ Adrian said quietly. ‘Thanks, son, that’s kind of you, but I’m not so sure.’

Chapter Three Are You Going to Die Soon? (#ulink_68663f1d-3868-5b84-a31f-9a5c66f54d27)

The following morning, after I’d taken Adrian to school and Paula to the nursery where she went for three hours each morning, I phoned Jill. She was expecting my call, and said a quiet, ‘Hello, Cathy.’

‘Has a relative been found for Michael yet?’ I asked hopefully, although I knew it was highly unlikely from what Jill had told me.

‘No,’ Jill said.

I hesitated, my brain working overtime to find the right words for what I had to say although, goodness knows, I’d spent long enough practising it – during the night and as soon as I’d woken.

‘Jill, I’ve obviously given a lot of thought to Patrick and Michael and I also asked Adrian and Paula what they thought.’ I paused again as Jill waited patiently on the other end of the phone. ‘The children think we have what it takes to look after Michael but I have huge doubts, so I’ve got a suggestion.’

‘Yes?’ Jill said.

‘You know Patrick has asked to meet the carer so that he can discuss Michael’s needs, routine, etc.?’

‘Yes.’

‘Presumably that meeting will also give him a chance to see if he feels the carer is right for his son?’

‘I suppose so, although to be honest Patrick can’t afford to be too choosy. We don’t have many foster carers free, and he hasn’t that much time, which he appreciates.’

‘Well, what I’m suggesting is that I meet Patrick and then we decide if Michael coming to me is right for both of us after that meeting. What do you think?’

‘I think you’re delaying a difficult decision and I’m not sure it’s fair on Patrick. But I’ll speak to his social worker and see what she thinks. I’ll get back to you as soon as I’ve spoken to her.’

Chastened, I said a subdued, ‘Thank you.’

Remaining on the sofa in the sitting room, I returned the phone to its cradle and stared into space. As if sensing my dilemma, Toscha, our cat, jumped on to my lap and began purring gently. Jill was partly right: I was delaying the decision, possibly hoping a distant relative of Michael’s might be found or that Patrick would take an instant dislike to me at the meeting. Foster carers don’t normally have the luxury of a meeting with the child’s parents prior to the child being placed so that all parties can decide if the proposed move is appropriate; usually the child just arrives, often at very short notice. But Michael’s case wasn’t usual, as Jill knew, which was presumably why she’d indulged me and was now asking his social worker what she thought about my suggestion. I hoped I wasn’t being unfair to Patrick. I certainly didn’t want to make his life more difficult than it must have been already.

Some time later, feeling pretty despondent, I ejected Toscha from my lap and, heaving myself off the sofa, left the sitting room. I went into the kitchen, where I began clearing away the breakfast dishes, my thoughts returning again and again to Patrick and Michael. Was I being selfish in asking to meet Patrick first before making a decision? Jill had implied I was. The poor man had enough to cope with without a foster carer dithering about looking after his son because it would be too upsetting.

It was an hour before the phone rang again and it was Jill. ‘Right, Cathy,’ she said, her voice businesslike but having lost its sting of criticism. ‘I’ve spoken to Stella, the social worker involved in Michael’s case, and she’s phoned Patrick. Stella put your suggestion – of meeting before you both decide if your family is right for Michael – to Patrick, and Patrick thinks it’s a good idea. In fact, Stella said he sounded quite relieved. Apparently he has some concerns, one being that you are not practising Catholics as they are. So that’s one issue we will need to discuss.’

I too was relieved and I felt vindicated. ‘I’ll look forward to meeting him, then,’ I said.

‘Yes, and we need to get this moving, so Stella has set up the meeting for ten a.m. tomorrow, here at the council offices. The time suits Patrick, Stella and me, and I thought it should be all right with you as Paula will be at nursery.’

‘Yes, that’s fine,’ I said. ‘I’ll be there.’

‘I’m not sure which room we’ll be in, so I’ll meet you in reception.’

‘OK. Thanks, Jill.’

‘And can you bring a few photos of your house, etc., to show Patrick?’

‘Will do.’

When I met the children later in the day – Paula from nursery at 12 noon, and Adrian from school at 3.15 p.m. – the first question they asked me was: ‘Is Michael coming to live with us?’ I said I didn’t know yet – that I was going to a meeting the following morning where Patrick and the social workers would be present and we’d decide after that, which they accepted. The subject of Michael wasn’t mentioned again during the evening, although it didn’t leave my thoughts for long. Somewhere in our community, possibly not very far from where I lived, there was a young lad, Adrian’s age, who was about to lose his father; while a relatively young father was having to come to terms with saying goodbye to his son for good. It had forced me to confront my own mortality, and later I realized it had unsettled Adrian and Paula too.

At bedtime Paula gave me an extra big hug; then, as she tucked her teddy bear in beside her, she said, ‘My teddy is very ill, Mummy, but the doctors are going to make him better. So he won’t die.’

‘Good,’ I said. ‘That’s what usually happens.’

Then when I went into Adrian’s bedroom to say goodnight he asked me outright: ‘Mum, you’re not going to die soon, are you?’

I bloody hope not! I thought.

I sat on the edge of his bed and looked at his pensive expression. ‘No. Not for a long, long time. I’m very healthy, so don’t you start worrying about me.’ Clearly I didn’t know when I was going to die, but Adrian needed to be reassured, not enter into a philosophical debate.

He gave a small smile, and then asked thoughtfully, ‘Do you think there’s a God?’

‘I really don’t know, love, but it would be nice to believe there is.’

‘But if there is a God, why would he let horrible things happen? Like Michael’s father dying, and earthquakes, and murders?’

I shook my head sadly. ‘I don’t know. Sometimes people who have a faith believe they are being tested – to see if their faith is strong enough.’

Adrian looked at me carefully. ‘Does God test those who don’t have a faith?’

‘I really don’t know,’ I said again. I could see where this was leading.

‘I hope not,’ Adrian said, his face clouding again. ‘I don’t want to be tested by having something bad happen. I think if God is good and kind, then he should stop all the bad things happening in the world. It’s not fair if bad things happen to some people.’

‘Life isn’t always fair,’ I said gently, ‘faith or no faith. And we never know what’s around the corner, which is why we should make the most of every day, which I think we do.’

Adrian nodded and laid his head back on his pillow. ‘Maybe I should do other things instead of watching television.’

I smiled and stroked his forehead. ‘It’s fine to watch your favourite programmes; you don’t watch that much television. And Adrian, please don’t start worrying about any of us dying; what’s happened in Michael’s family is very unusual. How many children do you know who lost one parent when they were little and are about to lose their other parent? Think of all the children in your school. Have you heard of anyone there?’ I wanted to put Michael’s situation into perspective: otherwise I knew Adrian could start worrying that he too could be left orphaned.

‘I don’t know anyone like that at school,’ he said.

‘That’s right. Adults usually live for a long, long time and slowly grow old. Look at Nana and Grandpa. They are fit and healthy and they’re nearly seventy.’

‘Yes, they’re very old,’ Adrian agreed. And while I wasn’t sure my parents would have appreciated being called ‘very old’, at least I had made my point and reassured Adrian. His face relaxed and lost its look of anguish. I continued to stroke his forehead and his eyes slowly closed. ‘I hope Michael can come and stay with us,’ he mumbled quietly as he drifted off to sleep.

‘We’ll see. But if it’s not us then I know whoever it is will take very good care of him.’

Chapter Four So Brave Yet So Ill (#ulink_dee1461c-ac4f-5a19-a1aa-e506a3a76bcb)

I usually meet the parent(s) of the child I am looking after once the child is with me. I might also meet them regularly at contact, when the child sees his or her parents; or at meetings arranged by the social services as part of the childcare proceedings. Sometimes the parents are cooperative and we work easily together with the aim of rehabilitating the child home. Other parents can be angry with the foster carer, whom they see as being part of ‘the system’ responsible for taking their child into care. In these cases I do all I can to form a relationship with the parent(s) so that we can work together for the benefit of their child. I’ve therefore had a lot of experience of meeting parents in the time I’ve been fostering, but I couldn’t remember ever feeling so anxious and out of my depth as I did that morning when I entered the reception area at the council offices and looked around for Jill.

Thankfully I spotted her straightaway, sitting on an end seat in the waiting area on the far side. She saw me, stood and came over. ‘All right?’ she asked kindly, lightly touching my arm. I nodded and took a deep breath. ‘Try not to worry. You’ll be fine. We’re in Interview Room 2. It’s a small room but there’s just the four of us. Stella, the social worker, is up there already with Patrick. I’ve said a quick hello.’

I nodded again. Jill turned and led the way back across the reception area and to the double doors that led to the staircase. There was a lift in the building but it was tiny and was usually reserved for those with prams or mobility requirements. I knew from my previous visits to the council offices that the interview rooms were grouped on the first floor, which was up two short flights of stairs. But as our shoes clipped up the stone steps I could hear my heart beating louder with every step. I was worried sick: worried that I’d say the wrong thing to Patrick and upset him, or that I might not be able to say anything at all, or even that I would take one look at him and burst into tears.

At the top of the second flight of stairs Jill pushed open a set of swing doors and I followed her into a corridor with rooms leading off, left and right. Interview Room 2 was the second door on the right. I took another deep breath as Jill gave a brief knock on the door and then opened it. My gaze went immediately to the four chairs arranged in a small circle in the centre of the room, where a man and a woman sat facing the door.

‘Hi, this is Cathy,’ Jill said brightly.

Stella smiled as Patrick stood to shake my hand. ‘Very pleased to meet you,’ he said. He was softly spoken with a mellow Irish accent.

‘And you,’ I said, relieved that at least I’d managed this far without embarrassing myself.

Patrick was tall, over six feet, and was smartly dressed in dark blue trousers, light blue shirt and navy blazer, but he had clearly lost weight. His clothes were too big for him and the collar on his shirt was very loose. His cheeks were sunken and his cheekbones protruded, but what I noticed most as we shook hands were his eyes. Deep blue, kind and smiling, they held none of the pain and suffering he must have gone through and indeed was probably still going through.

We sat down in the small circle. I took the chair next to Jill so that I was facing Patrick and had Jill on my right and Stella on my left.

‘Shall we start by introducing ourselves?’ Stella said. This is usual practice in meetings at the social services, even though we might all know each other or, as in this case, it was obvious who we were. ‘I’m Stella, Patrick and Michael’s social worker,’ Stella began.

‘I’m Jill, Cathy’s support social worker from Homefinders fostering agency,’ Jill said, looking at Patrick as she spoke.

‘I’m Cathy,’ I said, smiling at Patrick, ‘foster carer.’

‘Patrick, Michael’s father,’ Patrick said evenly. ‘Thank you,’ Stella said, looking around the group. ‘Now, we all know why we’re here: to talk about the possibility of Cathy fostering Michael. I’ll take a few notes of this meeting so that we have them for future reference, but I wasn’t going to produce minutes. Is that all right with everyone?’

Patrick and I nodded as Jill said, ‘Yes.’ Jill, as at most meetings she attended with me, had a notepad open on her lap so that she could make notes of anything that might be of help to me later and which I might forget. Now I was in the room and had met Patrick, I was starting to feel a bit calmer. My heart had stopped racing, although I still felt pretty tense. Everyone else appeared quite relaxed, even Patrick, who had his hands folded loosely in his lap.

‘Cathy,’ Stella said, looking at me, ‘I think it would be really useful if we could start with you telling us a bit about yourself and your family. Then Patrick,’ she said, looking at him, ‘would you like to go next and tell Cathy about you and Michael?’

Patrick nodded, while I straightened in my chair and tried to gather my thoughts. I don’t like being first to talk at meetings, although I’m a lot better now at speaking in meetings than I used to be when I first began fostering; then I used to be so nervous I became tongue-tied and unable to say what I wanted to. ‘I’ve been a foster carer for nine years,’ I began. ‘I have two children of my own, a boy and a girl, aged eight and four. I was married but unfortunately I’m now separated and have been for nearly two years. My children have grown up with fostering and enjoy having children staying with us. They are very good at helping the child settle in. It’s obviously very strange for the child when they first come to stay and they often talk to Adrian and Paula before they feel comfortable talking to me.’ I hesitated, uncertain of what to say next.

‘Could you tell us what sort of things you do at weekends?’ Jill suggested.

‘Oh yes. Well, we go out quite a lot – to parks, museums and places of interest. Sometimes to the cinema. And we see my parents, my brother and my cousins quite regularly. They all live within an hour’s drive away.’

‘It’s nice to do things as a family,’ Patrick said.

‘Yes,’ I agreed. ‘We’re a close family and obviously the child we look after is always included as part of our family and in family activities. I make sure all the children have a good Christmas and birthday,’ I continued. ‘And in the summer we try and go on a short holiday, usually to the coast in England.’ Patrick nodded. ‘I encourage the children in their hobbies and interests and I always make sure they are at school on time. If they have any homework I like them to do it before they play or watch television.’ I stopped and racked my brains for what else I should tell him. It was difficult giving a comprehensive thumbnail sketch of our lives in a few minutes.

‘Did you bring some photographs?’ Jill prompted.

‘Oh yes. I nearly forgot.’ I delved into my bag and took out the envelope containing photos that I had hastily robbed from the albums that morning. I passed them to Patrick and we were all quiet for some moments as he looked through them. There were about a dozen, showing my family in various rooms in the house, the garden, and also our cat, Toscha. Had I had more notice I would have put a small album together and labelled the photos.

Patrick smiled. ‘Thank you,’ he said, returning the photos to the envelope and then handing them back to me. ‘You have a lovely family and home. I’m sure if Michael stayed with you he would feel very comfortable.’

‘Thank you,’ I said.

‘Can I have a look at the photos?’ Stella asked. I passed the envelope to her. ‘While I look at these,’ she said to Patrick, ‘perhaps you’d like to say a bit about you and Michael?’

Patrick nodded, cleared his throat and shifted slightly in his chair. He looked at me as he spoke. ‘First, Cathy, I would like to thank you for coming here today and considering looking after my son when I am no longer able to. I can tell from the way you talk that you are a caring person and I know if Michael comes to stay with you, you will look after him very well.’ I gave a small smile and swallowed the lump rising in my throat as Patrick continued, so brave yet so very ill. Now he was talking I could see how much effort it took. He had to pause every few words to catch his breath. ‘It will come as no surprise to you to learn I was originally from Ireland,’ he continued with a small smile. ‘I know I haven’t lost my accent, although I’ve been here nearly twenty years. I came here when I was nineteen to work on the railways and liked it so much I stayed.’ Which made Patrick only thirty-nine years old, I realized. ‘Unfortunately I lost both my parents to cancer while I was still a young man. Cathy, you are very lucky to have your parents, and your children, grandparents. Cherish and love them dearly; parents are a very special gift from God.’

‘Yes, I know,’ I said, feeling my eyes mist. Get a grip, I told myself.

‘Despite my deep sadness at losing both my parents so young,’ Patrick continued, ‘I had a good life. I earned a decent wage and went out with the lads – drinking too much and chasing women, as Irish lads do. Then I met Kathleen and she soon became my great love. I gave up chasing other women and we got married and settled down. A year later our darling son, Michael, was born. We were so very happy. Kathleen and I were both only children – unusual for an Irish family – but we both wanted a big family and planned to have at least three children, if not four. Sadly it was not to be. When Michael was one year old Kathleen was diagnosed with cancer of the uterus. She died a year later. She was only twenty-eight.’

He stopped and stared at the floor, obviously remembering bittersweet moments from the past. The room was quiet. Jill and Stella were concentrating on their notepads, pens still, while I looked at the envelope of photographs I still held in my hand. So much loss and sadness in one family, I thought; it was so unfair. But cancer seems to do that: pick on one family and leave others free.

‘Anyway,’ Pat said casually, after a moment. ‘Clearly the good Lord wanted us early.’

I was taken aback and wanted to ask if he really believed that, but it didn’t seem appropriate.

‘To the present,’ Patrick continued evenly. ‘For the last six years, since my dear Kathleen was taken, there’s just been Michael and me. I didn’t bring lots of photos with me, but I do have one of Michael which I carry everywhere. Would you like to see it?’

I nodded. He tucked his hand into his inside jacket pocket and took out a well-used brown leather wallet. I watched, so touched, as Patrick’s emaciated fingers trembled slightly and he fumbled to open the wallet. Carefully sliding out the small photo, about two inches square, he passed it to me.

‘Thank you,’ I said. ‘What a smart-looking boy!’

Patrick smiled. ‘It’s his most recent school photo.’

Michael sat upright in his school uniform, hair neatly combed, slightly turned towards the camera, with a posed impish grin on his face. There could be no doubt he was Patrick’s son, with his father’s blue eyes, pale complexion and pleasant expression: the likeness was obvious.

‘He looks so much like you,’ I said as I passed the photo to Jill.

Patrick nodded. ‘And he’s got my determination, so don’t stand any nonsense. He knows not to answer back and to show adults respect. His teacher says he’s a good boy.’

‘I’m sure he is a real credit to you,’ I said, touched that Patrick should be concerned that his son’s behaviour didn’t deteriorate even when he was no long able to oversee it.

Jill showed the photograph to Stella and handed it back to Patrick. Patrick then went on to talk a bit about Michael’s routine, foods he liked and disliked, his school and favourite television programmes, all of which I would talk to him about in more detail if Michael came to stay with us. Patrick admitted his son hadn’t really had much time to pursue interests outside the home because of Patrick’s illness and having to help his father, although Michael did attend a lunchtime computer club at school. ‘I’m sure there are a lot of things I should have told you that I’ve missed,’ Patrick wound up, ‘so please ask me whatever you like.’

‘Perhaps I could step in here,’ Stella said. We looked at her. ‘I think the first issue we should address is the matter of Michael’s religion. Patrick and Michael are practising Catholics and Cathy’s family are not. How do you both feel about that?’ She looked at Patrick first.

‘Well, I won’t be asking Cathy to convert,’ he said with a small laugh. ‘But I would like Michael to keep attending Mass on a Sunday morning. If Cathy could take and collect him, friends of mine who also go can look after him while he’s there. I’ve been going to the same church a long time and the priest is aware of my illness, and does what he can to help.’

‘Would this arrangement work?’ Stella asked me.

‘Yes, I don’t see why not,’ I said, although I realized it would curtail us going out for the day each Sunday.

‘If you had something planned on a Sunday,’ Patrick said, as if reading my thoughts, ‘Michael could miss a week or perhaps he could go to the earlier mass at eight a.m.?’

‘Yes, that’s certainly possible,’ I said.

‘Thank you,’ Patrick said. Then quietly, almost as a spoken afterthought, ‘I hope Michael continues to go to church when I’m no longer here, but obviously that will be his decision.’

‘So can we just confirm what we have decided?’ Stella said, pausing from writing on her notepad. ‘Patrick, you don’t have a problem with Cathy not being a Catholic as long as Michael goes to church most Sundays?’

‘That’s right.’ He nodded.

‘And Cathy, you are happy to take Michael to church and collect him, and generally encourage and support Michael’s religion?’

‘Yes, I am.’

Both Jill and Stella made a note. Patrick and I exchanged a small smile as we waited for them to finish writing.

Stella looked up and at me. ‘Now, if this goes ahead, and we all feel it is appropriate for Michael to come to you, I know Patrick would like to visit you with Michael before he begins staying with you. Is that all right with you, Cathy?’

‘Yes.’

‘Thank you, Cathy,’ Patrick said. ‘It will help put my mind at rest if I can picture my son in his new bed at night.’

‘It’ll give you both a chance to meet my children as well,’ I said.

Jill and Stella both wrote again. ‘Now, to the other question Michael has raised with me,’ Stella said: ‘hospital visiting. When Patrick is admitted to hospital or a hospice, will you be able to take Michael to visit him?’

‘Yes, although I do have my own two children to think about and make arrangements for. Would it be every day?’

‘I would like to see Michael every day if possible, preferably after school,’ Patrick confirmed.

‘And at weekends?’ Jill asked.

‘If possible, yes.’

It was obviously a huge undertaking, and while I could see that of course father and son would want to see as much of each other as possible I was wondering about the logistics of the arrangement, and also how Adrian and Paula would feel at being bundled into the car each day after school and driven across town to the hospital instead of going home and relaxing.

‘Were you thinking Cathy would stay for visiting too?’ Jill asked, clearly appreciating my unspoken concerns.

‘Not necessarily,’ Patrick said. ‘Cathy has her own family to look after and Michael is old enough to be left in the hospital with me. It would just need someone to bring and collect him.’

‘If Cathy wasn’t able to do it every day,’ Jill said to Patrick, ‘would you be happy if we used an escort to bring and collect Michael? We use escorts for school runs sometimes. All the drivers are vetted.’

‘Yes, that’s fine with me,’ he said. ‘It shouldn’t be necessary for a long time, as I intend staying in my home for as long as possible, until I am no longer able to look after myself.’ Which made me feel small-minded and churlish for not agreeing to the arrangement outright.

‘It’s not a problem,’ I said quickly. ‘I’ll make sure Michael visits you every day.’

‘Thank you, Cathy,’ Patrick said, then with a small laugh: ‘And don’t worry, you won’t have to arrange my funeral: I’ve done it.’

I met Patrick’s gaze and hadn’t a clue what to say. I nodded dumbly. Jill and Stella made no comment either, for what could we possibly say?

‘So,’ Stella said, after a moment, ‘do either of you have any more questions or issues you wish to explore?’

I shook my head. ‘I don’t think so,’ I said. ‘No,’ Patrick said. ‘I would like it if Cathy agreed to look after Michael. I would be very grateful.’

I was looking down again, concentrating on the floor. ‘And what is your feeling, Cathy?’ Stella asked. ‘Or would you like some time to think about it?’

‘No, I don’t need more time,’ I said. ‘And Patrick deserves an answer now.’ I felt everyone’s eyes on me. Especially Jill on my right, who, I sensed, was cautioning me against saying something I should take time to consider. ‘I will look after Michael,’ I said. ‘I’d be happy to.’

‘Thank you,’ Patrick said. ‘God bless you.’ And for the first time I heard his voice tremble with emotion.

Chapter Five Treasure (#ulink_b2b8cbf8-e66e-57d6-9651-e663ece72d20)

Usually, once I’ve made a decision I’m positive and just get on with the task in hand. But now, as I left the council offices and began the drive to collect Paula from nursery, I was plagued with misgiving and doubt. Had I made the right decision in offering to look after Michael or had I simply felt sorry for Patrick? What effect would it have on Adrian and Paula? What effect would it have on me? Then I thought of Patrick and Michael and all they were going through and immediately felt guilty and selfish for thinking of myself.

I switched my thoughts and tried to concentrate on the practical. At the end of the meeting we’d arranged for Patrick and Michael to visit the following evening at 6.00. I now considered their visit and what I could do to make them feel relaxed and at home. Although I’d had parents visit prior to their child staying before, it was very unusual. One mother had visited prior to her daughter staying when she was due to go into hospital (she didn’t have anyone else to look after her child); another set of parents had visited before their son (with very challenging behaviour) had begun a respite stay to give them a break. Both children were in care under a voluntary care order (now called a Section 20), where the parents retain all legal rights and responsibilities. This was how Michael would be looked after, but that was where any similarity ended: the other children had returned home to their parents. And whereas the other visits had been brief – I’d showed the family around the house and explained our routine – I thought Patrick and Michael’s visit needed to be more in-depth, to give them a feeling of our home life which would, I hoped, reassure them both. I decided the best way to do this would be for us to try and carry on as ‘normal’, and then tormented myself by picturing Patrick and Michael sitting on the sofa and Adrian and Paula staring at them in silence.

At dinner that evening I told Adrian and Paula that Patrick and Michael would be coming for a visit the following evening to meet them and see the house. ‘So let’s make sure they feel welcome and the house is tidy,’ I added, glancing at Adrian.

He looked at me guiltily, for even allowing for the fact that eight-year-old boys were not renowned for their tidiness the mess he managed to generate sometimes was incredible. It was often impossible to walk across his bedroom floor for toys, all of which he assured me had to remain in place, as otherwise his game would be ruined. I was never quite sure what exactly ‘the game’ was but it seemed to rely on all his toy cars and models – of dinosaurs, famous people and the planets – covering the carpet and being scooped up and then put down again in a different places by a large plastic dumper truck, which made a hideous hooting sound when it reversed. But the game had kept him, visiting friends and sometimes Paula occupied for hours in recent months, and had only been tidied away when I’d vacuumed.

‘Suppose I’d better tidy my room,’ Adrian muttered, understanding my hint.

‘That would be good,’ I said.

‘Is Michael coming to stay, then?’ Paula asked.

‘Yes, but not tomorrow. Tomorrow he and his father are just coming for a visit so that they can see what our home is like before Michael has to move in.’

‘When’s he moving in?’ Adrian asked.

‘I’m not sure yet. It will depend on his father. I met him today. He’s a lovely man. Sometimes he has to speak slowly to catch his breath.’ I thought I should mention this so that the children wouldn’t stare or, worse, comment. Adrian was old enough to know not to comment, but I could picture Paula asking Patrick, ‘Why are you talking funny?’ as a young child can.

‘Why does he speak slowly?’ Paula now asked.

‘Because he’s ill,’ Adrian informed her.

‘That’s right,’ I said. ‘Sometimes it takes all Patrick’s energy to talk, although he does very well.’

‘I see,’ Paula said quietly, and we continued with our meal.

The following day I took Adrian to school, and Paula to nursery, and then did a supermarket shop. I came home and by the time I’d unpacked all the bags it was time to collect Paula from nursery. The afternoon vanished in playing with Paula and housework, and it was soon time to collect Adrian from school. Those who don’t have children sometimes wonder what stay-at-home mothers (or fathers) find to do all day; and indeed I was guilty of this before I gave up work to look after my children and foster. Now I know!

At 5.40 p.m. the children were eating their pudding when the doorbell rang. ‘You finish your meal,’ I said, standing. ‘It might be Patrick and Michael arriving early.’

Although the children hadn’t mentioned Michael and his father since the previous evening, they hadn’t been far from my thoughts, especially when I’d prepared the spare bedroom that afternoon so that it would look welcoming when Michael saw it. Now as I went down the hall towards the front door my heart began pounding as all my anxieties and misgivings returned. I just hoped, as I had done prior to the meeting, I didn’t say anything silly or embarrassing that would upset Patrick and now Michael.

Taking a deep breath, I opened the door with a smile. ‘Hello,’ I said evenly. ‘Good to see you both.’

‘And you,’ Patrick said easily. ‘This is Michael.’ Patrick was standing slightly behind his son and again looked very smart in a blazer and matching trousers. Michael was dressed equally smartly in his school uniform but looked as anxious as I felt.

‘Hi, Michael,’ I said. ‘Come in. Try not to worry. It’s a bit strange for me too.’

He gave a small nervous laugh and shrugged as they came into the hall. Patrick shook my hand and kissed my cheek, which I guessed was how he greeted all female friends and acquaintances. ‘Lovely place you have here,’ he said.

‘Thank you. Come on through and meet Adrian and Paula.’

I smiled again at Michael and then led the way down the hall and to where the children were finishing their pudding.

‘We’ve interrupted your meal,’ Patrick said, concerned.

‘Don’t worry, they’ve nearly finished. This is Adrian and Paula, and this is Michael and his dad, Patrick,’ I said, introducing everyone.

‘Good to meet you,’ Patrick said to Adrian and Paula.

‘Hi,’ Adrian said, glancing up from his pudding. Michael said nothing.

‘Say hello, Michael,’ Patrick prompted.

‘Hello,’ Michael said reluctantly.

‘Why can’t we have a girl?’ Paula grumbled.

Patrick frowned, puzzled, and looked at me. ‘It’s Paula’s little joke,’ I said, throwing her a warning glance.

Patrick smiled at Paula while I asked Michael, ‘Have you had a good day at school?’ I wasn’t sure who felt more awkward – the children or the adults.

Michael thrust his hands into his trouser pockets and shrugged.

‘Answer Cathy,’ Patrick said.

‘Yes, thank you,’ Michael said formally. ‘Your dad tells me you’re doing very well at school,’ I said, trying to put him at ease and get some conversation going.

Michael dug his hands deeper into his trouser pockets and shrugged again.

‘Take your hands out of your pockets,’ Patrick said firmly, catching his breath. Then to me, ‘I’m sorry, Cathy, the cat seems to have got my son’s tongue. He’s usually quite talkative.’

‘Don’t worry,’ I said. ‘It’s a bit strange for everyone. I’m sure they’ll all thaw out soon.’ Adrian and Paula had finished their pudding and were now sitting staring at Michael, not unkindly, just eyeing the newcomer up and down. ‘Shall I show you around the house first?’ I asked Patrick. ‘Then afterwards the children can play together for a while.’

‘Thank you, Cathy,’ Patrick said with a smile. ‘That would be nice.’ Michael said nothing.

Adrian and Paula stayed at the table while I turned and led the way into the kitchen. ‘Very nice,’ Patrick said.

‘And through here,’ I said going ahead, ‘is the sitting room. From here you can see the garden and the swings.’ Patrick joined me at the French windows while Michael hung back.

‘Your garden looks lovely,’ Patrick said. ‘Do you do it all yourself?’

‘Yes, it keeps me fit,’ I said, smiling. ‘I usually garden while the children are out there playing. The bottom half of the garden with the swings is for the children. There are no plants or flowers there, so they can play and kick balls without doing any damage.’

‘Good idea. Come and have a look, Michael,’ Patrick encouraged. ‘What a lovely big garden!’

Michael took a couple of steps into the centre of the room, shrugged and stayed quiet. I saw how uncomfortable Michael’s sulky attitude was making Patrick feel and I felt sorry for him. Patrick was being so positive and I knew he would be wanting to create a good first impression, just as I did, but I also knew that Michael’s behaviour was to be expected. Clearly Michael didn’t want to be here, for this was where he would be staying when his father could no longer look after him. I wondered how much discussion Patrick had had with his son to prepare him for staying with me – it was something we would need to talk about.

‘There’s just the front room left downstairs,’ I said, moving away from the window.

I led the way out of the sitting room, down the hall and to the front room with Patrick just behind me and Michael bringing up the rear. Then we went upstairs, where I showed them our bedrooms, toilet and bathroom. Patrick made a positive comment about each room while Michael said nothing. When we went into what was going to be Michael’s bedroom Michael stayed by the door. ‘Very comfortable,’ Patrick said. Then to Michael: ‘Come in and have a look. You’ll be fine here, son.’

But Michael didn’t reply. He shrugged, jabbed his hands into his trouser pockets again and refused to move. I saw Patrick’s expression set and knew he was about to tell him off. I lightly touched Patrick’s arm and shook my head slightly, gesturing for him not to say anything. ‘Perhaps we could have a chat later?’ I suggested.

Patrick nodded.

‘Well, that’s the tour finished,’ I said lightly to Michael and Patrick. ‘Let’s go downstairs and find Adrian and Paula.’

I went out of the bedroom and as I passed Michael I touched his shoulder reassuringly. I wanted him to know it was all right to feel as he did – that I wasn’t expecting him to be dancing and singing.

Downstairs, Adrian had thawed out and Paula seemed to be over her pique about not having a girl to stay. They had taken some board games from the cupboard and Adrian was setting up a game called Sunken Treasure. It was a good choice: I saw Michael’s eyes light up. ‘Would you like to play with Adrian and Paula,’ I suggested, ‘while your father and I have chat in the sitting room?’

Michael nodded, took his hands out of his pockets and slid into a chair at the table. ‘I’ve played this before,’ he said enthusiastically. I looked knowingly at Patrick and he winked back.

‘Would you like a drink?’ I asked Patrick. ‘Tea, coffee?’

‘Could I have a glass of water, please?’

‘Of course. Michael,’ I asked, ‘would you like a drink? Or how about an ice cream?’

Michael looked up from the table and for the first time smiled.

‘Is it all right if I give Michael an ice cream?’ I asked his father.

He nodded.

‘Would you like one?’

‘No, just the water, please,’ Patrick said. ‘Thank you.’

I didn’t bother asking Adrian and Paula if they wanted an ice cream because I knew what their answers would be. I went into the kitchen, took three ice creams from the freezer and, together with three strips of kitchen towel, returned to the table and handed them out. I poured a glass of water for Patrick and we went into the sitting room, where I pushed the door to so that we couldn’t be easily overheard.

‘Sorry about that,’ Patrick said.

‘Don’t worry. It’s to be expected.’

As Patrick sat on the sofa he let out a sigh, pleased to be sitting down. ‘That’s better. It’s a good walk from the bus stop,’ he said.

‘You caught the bus here?’ I asked, surprised.

He nodded, took a sip of his water, and then said easily, ‘I sold my car last month. I thought it would be one less thing for Eamon and Colleen to have to worry about. Eamon and Colleen are my good friends who are executors of my will. I’ve been trying to make it easier for them by getting rid of what I don’t need now.’

Although Patrick was talking about his death he spoke in such a practical and emotionless manner that he could have been simply making arrangements for a trip abroad, so that I didn’t feel upset or emotional.

‘All that side of things is taken care of,’ Patrick continued. ‘What money I have will be held in trust until Michael is twenty-one. I have a three-bedroom house and I was going to sell that too and rent somewhere, but I thought it would be an unnecessary upheaval for Michael. It’s always been his home and he will have to move once I go into hospital, so I decided there was no point in making him move twice.’

‘No,’ I agreed. ‘I think that was wise of you.’

There was a small silence as Patrick sipped his water and I watched him from across the room. I liked Patrick – both as a person and a man. Already I had formed the impression that he was kind and caring, as well as strong and practical, and despite his illness his charisma and charm shone through. I could picture him out drinking with the lads and chasing women in his twenties, as he’d said he had at the meeting, and then being a loyal and supportive husband and proud father.

‘I think you are doing incredibly well,’ I said. ‘I’m sure I wouldn’t cope so well.’

‘You would if you had to, Cathy,’ he said, looking directly at me. ‘You’d be as strong as I’ve had to be – for the sake of your children. But believe me, in my quieter moments, in the early hours of the morning when I’m alone in my bed and I wake in pain and reach for my medication, I have my doubts. Then I can get very angry and ask the good Lord what he thinks he’s playing at.’ He threw me a small smile.

‘And what does the good Lord say?’ I asked lightly, returning his smile.

‘That I must have faith, and Michael will be well looked after. And I can’t disagree with that because he’s sent us you.’

I felt my emotion rise and also the enormity and responsibility of what I’d taken on. ‘I’ll do my best,’ I said, ‘but I’m no angel.’

‘You are to me.’

I looked away, even more uncomfortable that he was placing me on a pedestal. ‘Is there really no hope of you going into remission?’ I asked quietly.

‘Miracles can happen,’ Patrick said, ‘but I’m not counting on it.’

There was silence as we both concentrated on the floor and avoided each other’s gaze. ‘I hope I haven’t upset you,’ I said after a moment, looking up.

‘No.’ Patrick met my gaze again. ‘It’s important we speak freely and you ask whatever you wish. You will become very close to me and Michael over the coming months. Not to talk of my condition would be like ignoring an elephant in the room. I wish Michael could talk more freely.’

‘How much does Michael understand of the severity of your condition?’ I now asked.

‘I’ve been honest with him, Cathy. I have told him I am very ill – that unfortunately the treatment didn’t work and I am unlikely to get better. But I don’t think he has fully accepted it.’

‘Does he talk about his worries to you?’

‘No, he changes the subject. I’m sorry he was rude earlier but he didn’t want to come here this evening.’

‘It’s understandable,’ I said. ‘There’s no need to apologize. Coming here has forced Michael to confront a future he can’t bear to think about – one without you. To be honest, since I heard about you and Michael I have tried to imagine what it would be like for Adrian and Paula to be put in Michael’s position, and I can’t. I can’t contemplate it. So if I, as an adult, struggle, how on earth does Michael cope? He’s only eight.’

‘By pretending it’s not happening,’ Patrick said. ‘He’s planning our next summer holiday. We always take – I mean we used to take – a holiday together in August, but I can’t see it happening this year.’

‘It might,’ I said. ‘You never know.’

‘Possibly, but I’m not giving Michael false hope.’

‘No, and I won’t either,’ I reassured him.

A cry of laughter went up from the room next door where the children were playing Sunken Treasure, followed by a round of applause. ‘I think someone has found treasure,’ I said.

Patrick’s eyes sparkled as he looked at me and said, ‘I think Michael and I have too.’

Chapter Six Lonely and Afraid (#ulink_8d35d843-416c-54e1-a865-cf49d5964e2b)

That evening Patrick and I continued talking for another hour while the children played. Our conversation grew easier and more natural as we both relaxed and got to know each other. We didn’t talk about the future again or his illness but about our separate pasts and the many happy memories we both had. He told me of all the good times he’d had as a child in Ireland and then with his wife, Kathleen. I shared my own happy childhood memories and then told him how I’d met John, my husband, and how we’d started fostering. I also told him of the shock and disbelief I’d felt when John had suddenly left me. I was finding Patrick very easy to talk to, as I think he did me.

‘Looking back,’ I said speaking of John’s affair, ‘I guess there were warning signs: the late nights at work, the weekend conferences. Classic signs, but I chose to ignore them.’

‘Which was understandable,’ Patrick said. ‘You trusted him. Trust is what a good marriage is based on.’

‘I’ve let go of my anger, but it will be a long time before I forgive him,’ I admitted.

Patrick nodded thoughtfully.

I made us both a cup of tea while the children continued playing board games; then when it was nearly 7.15 and the light outside was staring to fade, Patrick said, ‘Well, Cathy, I could sit here all night chatting with you but we’d best be off. Michael has school in the morning and I’m sure you have plenty to do.’

‘Will you be all right catching the bus?’ I said. ‘Or can I give you a lift?’

‘No, we’ll be fine, thank you. I’m sure you’d rather get started with your children’s bedtime routine.’

I smiled. As a single parent – having raised Michael alone for six years – Patrick was familiar with the bedtime routine of young children: of bathing, teeth-brushing, bedtime stories, hugs and kisses goodnight, etc. He was right: I did appreciate the opportunity of settling the children into bed rather than driving across town.

We went to the table where the children were now in the middle of a game of Monopoly. ‘Time to go, son,’ Patrick said.

‘Oh, can’t I finish the game first?’ Michael moaned good-humouredly. I was pleased to see he had now relaxed and was enjoying himself.

‘Next time,’ Patrick said. ‘You’ve got school tomorrow.’

Michael pulled a face and reluctantly stood. ‘Do you want some help packing away?’ he asked Adrian, which I thought was very thoughtful.

‘Don’t worry,’ I said. ‘We’ll do it. You and your dad need to get on the bus.’

Michael and his father used the bathroom first and then Adrian, Paula and I showed them to the front door and said goodbye.

‘Thanks, Cathy,’ Patrick said, taking my hand between his and kissing my cheek. ‘We’ve had a nice evening, haven’t we, Michael?’

Michael nodded. He looked a lot happier than he had done when he’d first arrived; his cheeks were flushed from the excitement of the games they’d played, and Adrian and Paula looked as though they’d enjoyed playing with Michael. All of which bode well for the future.

‘I’ll be in touch,’ Patrick said as he and Michael went down the front path. ‘Goodnight and God bless.’

‘And you,’ I called after them.

We watched them go and then I closed the front door. ‘All right?’ I asked the children. ‘Did you have a nice evening?’

‘Yes,’ Adrian said. ‘Michael’s OK.’

‘Is Michael’s daddy coming to live with us?’ Paula asked. ‘No, only Michael,’ I said. ‘What made you think that?’ Paula looked thoughtful, clearly having been working something out. Then she said, ‘If Michael’s daddy came to live with us, you could look after him and make him better. You make me better when I’m ill. Then when he’s better we can all live together, and Michael will have a mummy again, and we’ll have a daddy.’

Adrian tutted.

I smiled and gave her a hug. If only life were that simple, I thought. ‘It’s a bit more complicated than that,’ I said. ‘And you have a daddy: it’s just that he doesn’t live with us any more.’

That evening when the children were in bed I wrote up my log notes of Patrick and Michael’s visit. All foster carers have to keep a log – a daily record of the child or children they are fostering. In their log the carer records the child’s progress, their physical and emotional health, their education and any significant events. The log is usually begun when the carer first meets the child and ends when the child leaves the foster home. These log notes are then placed on the social services’ files and form part of the child’s record, which the child can read when they are older. Not only is keeping a log a requirement of fostering: it is also a valuable and detailed record of part of the child’s history. I had begun my log for Michael after meeting Patrick at the social services’ offices the day before and now continued it with their visit. It was just a paragraph saying how long they had stayed, that their visit had gone well, and while Michael had been subdued to begin with he had responded to Adrian and Paula, and the three of them had played together, while Patrick and I had talked. But as I wrote I felt as though I was writing up a friend’s visit in a diary rather than the log notes of a foster carer, so easily had we all bonded.

The following afternoon Jill telephoned to check on how Patrick and Michael’s visit had gone. ‘Very good,’ I said. ‘Much better than I’d expected. Michael was a bit quiet to begin with, but then he played with Adrian and Paula while Patrick and I chatted. Patrick’s a lovely person and very easy to talk to. He’s done a great job of bringing up Michael alone.’

Possibly Jill heard something in my voice or perhaps it was that she knew me from being my support social worker, for there was a small pause before she said: ‘Good, but you might have to put some professional distance between you and Patrick. I know how involved you get with our looked-after children and their families. Patrick is likely to be very needy in his situation with no family of his own to support him.’

‘He’s not needy,’ I said defensively. ‘And although he has no immediate family he has lots of very supportive friends.’

‘Good,’ Jill said again, ‘but just be careful. I wouldn’t want you getting hurt.’

‘All right, Jill. I hear what you’re saying. I’ll be careful.’

Jill then gave me some feedback from Stella – Patrick and Michael’s social worker – who’d spoken to Patrick that morning. Stella had confirmed that the evening had gone well from Patrick and Michael’s point of view. Patrick had sent his thanks and asked if they could visit again the following Saturday, perhaps for a bit longer. Today was Friday, so it was just over a week away.

‘I realize this is more introduction than we would normally do,’ Jill added. ‘But if it helps prepare Michael for when he moves in, when Patrick goes into hospital, then it seems appropriate.’

‘Yes, that’s fine with me,’ I said. ‘I could make us some dinner.’

‘Let’s set the time for their visit as two to six. Does that fit in with your plans?’

‘Yes, or two to seven if they are staying for dinner.’

‘OK. I’ll run it past Stella and get back to you. If I can’t reach her this afternoon, it’ll be Monday. Have a good weekend.’

‘Thanks, Jill. And you.’

When Jill phoned back on Monday afternoon she asked if we’d had a good weekend and then confirmed that Patrick and Michael would be visiting from 2.00 to 7.00 p.m. the following Saturday. She passed on Patrick’s thanks and Stella’s gratitude for being so accommodating, but there was no need. If they came and stayed for dinner it would be more like a social event than part of the introductions for a fostering placement, and something I would look forward to, as I thought Adrian and Paula would too. As soon as Jill had finished on the phone I began planning what I would cook for dinner on Saturday. I knew Patrick and Michael were both meat eaters because Patrick had mentioned the roasts he liked to cook after church on Sundays, so I thought roast chicken with vegetables would be a good idea, and perhaps I’d make a bread-and-butter pudding; I hadn’t made one in ages and Adrian and Paula loved it. Planning for Saturday gave me a frisson of warmth for the rest of the day and indeed most of that week.

However, it was not to be.

On Thursday afternoon when I was standing in the school playground with Paula, waiting for Adrian to come out, my mobile rang. ‘Sorry,’ I said to the mother I was talking to, taking my phone from my pocket. Jill’s office number was displayed and I moved slightly away from the group I’d been standing with in case what Jill had to say was confidential.

‘Cathy, where are you?’ Jill asked as soon as I answered. ‘Are you collecting Adrian from school?’ She spoke quickly, suggesting it was urgent.

‘I’m in the playground now, waiting for his class to come out. What’s the matter?’

‘Patrick has just been admitted to hospital. He collapsed at home this afternoon. A neighbour found him and called an ambulance.’

‘Oh. Is he all right?’ I said, which was a really silly question.

‘I don’t have any more details, but can you collect Michael from school and look after him for the weekend? It’s what we’d been working towards but obviously it’s come early. Michael’s going to be very upset and shocked, as it’s all happened so quickly. His teacher is looking after him until you arrive. I’ll phone the school and tell them you’re on your way. You know where St Joseph’s school is?’

‘Yes,’ I said, shocked by the news. ‘I’ll go as soon as I’ve got Adrian. Is Patrick very ill?’

‘I don’t know. I’ll phone Stella after I’ve phoned the school and see what I can find out. We’ll need to get a change of clothes for Michael and also see about hospital visiting.’

‘Yes,’ I said, my thoughts reeling. The school doors opened and classes began filing out. ‘I should be at Michael’s school in about fifteen minutes,’ I said to Jill.

‘I’ll phone them and let them know. Thanks. I’ll be in touch.’

Saying a quick goodbye, I returned my phone to my jacket pocket and took hold of Paula’s hand. I gave it a reassuring squeeze. ‘That was Jill,’ I said. ‘I’m afraid Michael’s daddy isn’t very well. He’s in hospital. We’re going to collect Michael from school and he’s staying the weekend.’ I took some comfort from Jill’s words, which suggested Patrick would be coming out of hospital again after the weekend.

‘Aren’t they coming for dinner on Saturday?’ Paula asked as Adrian’s class began streaming out.

‘No. Well, Michael will be with us but his daddy isn’t well enough.’

I spotted Adrian and gave a little wave. He bounded over. ‘Can Jack come to tea? He’s free tonight.’

‘I’m sorry, not tonight,’ I said as Jack dragged his mother over. ‘Can we make it next week?’

‘Sure,’ Jack’s mother said. ‘I told Jack it was too short notice.’

Adrian pulled a face.

‘I’ll speak to you next week and arrange something,’ I confirmed to Jack’s mother.

‘That’s fine,’ she said. ‘Come on, Jack.’

I began across the playground with a disgruntled Adrian on one side and Paula on the other. ‘I’m sorry,’ I said to Adrian, ‘but it would have been a good idea to ask me first before you invited Jack for tea. I’ve just had a call from Jill and –’

‘Michael’s daddy is in hospital,’ Paula put in.

‘Thank you, Paula,’ I said a little tersely. ‘I can tell Adrian.’ I could feel myself getting stressed.

‘We’re going to Michael’s school now,’ I clarified. ‘His daddy was taken to hospital this afternoon. Michael will be staying with us for the weekend. I know it’s all a bit short notice but it can’t be helped. Michael’s obviously going to be very worried and upset.’

Adrian didn’t say anything but his face had lost its grumpiness and disappointment at not having Jack to tea and was now showing concern for Michael.

We went round the corner to where I’d parked the car and the children clambered into the back. I helped Paula fasten her seatbelt as Adrian fastened his. I then drove to Michael’s school – St Joseph’s Roman Catholic primary school – on the other side of the town centre, although I used the back route to avoid going through the town itself. During the drive we were all quiet, concerned for Michael and his father and feeling the sadness Michael must be feeling.

The road outside the school was clear, most of the children having gone home, so I was able to park where the zigzag lines ended outside the school. The building was a typical Victorian church school with high windows, a stone-arched entrance porch and a small playground at the front, now protected by a tall wire-netting fence. Although I’d driven past the school before, I’d never been inside. Someone in the school must have seen us cross the playground, for as I opened the heavy outer wooden door and entered the enclosed dark porch, the inner door suddenly opened. I was startled as a priest in a full-length black cassock stood before us. Adrian and Paula had stopped short too.

‘You’ve come to collect Michael?’ the priest asked.

‘Yes. I’m Cathy Glass.’

‘Come this way. Michael is waiting in the head teacher’s office.’ He turned and led the way.