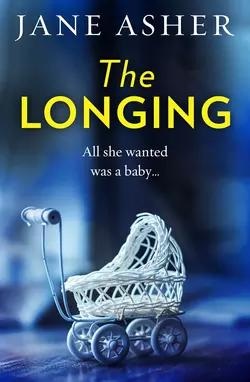

The Longing: A bestselling psychological thriller you won’t be able to put down

Jane Asher

A compulsive and topical psychological thriller and a contemporary story of obsession, in which a happily married, educated, middle-class woman is driven to snatch a stranger’s baby from its pram.All she wanted was a baby. Was that so much to ask? A baby to nourish in her body, to give birth with pain and pleasure, to adore. A baby to suckle and care for, to clean and cuddle and comfort. A baby to make her whole and complete. But her womb was empty and its emptiness filled her days and her nights, invaded her dreams, determined every waking thought. A baby. All she wanted was a baby…

Copyright (#ulink_53e5c7ed-ad40-5fff-8edb-64bd64c7241e)

The characters and events in this book are entirely fictional. No reference to any person, living or dead, is intended or should be inferred.

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

This edition 1997

First published in Great Britain by

HarperCollinsPublishers 1996

Copyright © Jane Asher 1996

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2017 Cover photograph © Shutterstock.com (http://www.shutterstock.com)

Jane Asher asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007571826

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2013 ISBN: 9780007571826

Version: 2017-12-18

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Dedication (#ulink_e7c5e994-de09-5954-a469-06d32f599bff)

To Gerald

THE LONGING

Celebrated British actress of stage and screen, Jane Asher is also well known for her many other activities, especially her non-fiction books and journalism and her successful cake making business. The Longing is her stunning debut novel, and was published in hardcover to widespread acclaim in 1996. She lives in London, with her husband and three children, and is working on her second novel.

Critical acclaim for The Longing:

‘Topical, emotion-charged, [The Longing] grips from the first page and conveys with extraordinary vividness the terrible anguish experienced by couples who cannot start their longed-for baby.’

VAL HENNESSY, Daily Mail

‘A writer who does convey real emotional power . . . The Longing is a story about infertility: the desperation that overtakes couples who can’t conceive and the tragic consequences of that desperation. Like all really good novels, it is true – not in the factual sense, but in the way that its characters seem real and the world in which they move is one we recognise. Even better, its power increases as it goes on, drawing you further into its plot, gripping more tightly with every page . . . if Jane Asher were not already famous, this book would make her so.’

Daily Express

‘Thought provoking, polished and professional, a modern tale of Gothic horror.’

The Times

‘Strong dialogue drives the plot along and short, intercutting scenes add structure and drama.’

TLS

‘Tightly plotted and pacily told.’

Daily Telegraph

‘An absorbing and thought-provoking read.’

Eastern Daily Press

‘A taut psychological thriller . . . she deftly weaves each strand of the very clever plot, keeping the reader tied to every last word.’

Belfast Telegraph

‘Asher undoubtedly has an eye for character. The Longing is a good, if emotionally draining read.’

Punch

‘A celebrity novel from, at last, a celebrity who can actually write them.’

SHERIDAN MORLEY, Sunday Times

Contents

Title Page (#u5899b35b-97f9-5866-9721-e1946dd74e52)

Copyright (#ulink_09a4432b-723f-544d-a792-2851378f0ddd)

Dedication (#ulink_0659bc94-4f6c-5be7-9837-325d16e427cf)

Prologue (#ulink_2fe971a2-f77e-5973-b51c-48fe8e78aa44)

Chapter One (#ulink_6c5d9a2e-8ca7-5b37-9815-c1cd9fcda2c9)

Chapter Two (#ulink_65d4d9c0-4d86-50e1-af2e-6595d4bd51a5)

Chapter Three (#ulink_1b1e1671-34a6-5a4d-81fa-23e491068bba)

Chapter Four (#ulink_d297f14d-0325-5286-ac93-0b100071c0eb)

Chapter Five (#ulink_9260645c-1417-5627-8dfe-72464b31a62c)

Chapter Six (#ulink_cb00e143-9bf1-5e46-8948-8abb5627fc85)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_750bf4f3-d020-5250-b486-43478ee21809)

The effort was exhausting him; instead of getting excited he felt depressed and hopeless. He sighed and stretched his arms out in front of him until his linked fingers cracked at the knuckles, then looked down again at the magazine on his lap, turning the page to be confronted by yet another tight, artificially tanned bottom thrusting uninvitingly up at him, breasts lolling in the background. Instead of making him stiffer, it merely made him despair.

Throwing the magazine back on to the table he stood up, moved over to the line of videos in the small bookcase and scanned the covers in search of inspiration, humming an unidentifiable tune as he turned his head first one way and then another to read the titles. ‘Might be worth a try,’ he muttered to himself as he pulled one out, then slotted it into the open-mouthed recorder and sat back to watch. After a few moments of fascination at the proportions of the girls gambolling on the beach, he realised he had completely forgotten the purpose of it all and had let his mind wander off into thinking how small the little lines must be to fit in six hundred and twenty-five on the screen. ‘Oh, this is ridiculous,’ he said out loud, and blew out his lips in exasperation as he got up and switched off the recorder.

Another tack. He sat on the plastic seat of the nearest chair, leant back against the wall, closed his eyes and thought of Julie, picturing her undressing in the slowly casual way she did when she knew he was watching her. He felt a comforting little twitch of response and persevered. Julie arching her back as she undid her bra, leaning forward to pull down her tights, smiling at him from under her hair as if shy of him after ten years of marriage.

Disappointingly, she was suddenly dressed again and putting the Sunday joint in the oven. He managed to force her clothes off again with a huge effort of will but as soon as she was naked they irritatingly snapped back on again.

He opened his eyes, resisted a strong temptation to look at his watch, and picked up another magazine.

Chapter One (#ulink_59b22eb4-b37f-539f-a2cc-e2e291269c3e)

At last Harry was sleeping. After a night of walking the baby up and down, rubbing his back as he struggled against her left shoulder in the seemingly unending battle against colic, Anna had spent much of the morning trying to settle him in his cot. Finally she had given up and decided to go out, hoping that a long journey in the old-fashioned pram would work its usual magic and lull him to sleep. He had still been wide awake and grizzling as she reached the row of shops where she usually stopped, so she had kept going for half a mile or so towards another supermarket where she hadn’t shopped since before his birth three months earlier. He had drifted off only moments before she turned the corner into Streatham High Road, his eyelids closing in spite of himself, his natural curiosity at the extraordinary business of being alive stifled by the irresistible drowsiness produced by the comforting jolting of the pram wheels over the pavement.

She pushed open the heavy glass door of the shop with one hand and manoeuvred the pram inside by pushing it with her body as she gripped the handle and her bag with the other, then stopped in annoyance. It was immediately clear that there would be no chance of the large second-hand pram fitting comfortably back through the checkouts on her way out, and even the narrow aisles, though they were empty of customers, were littered with dump bins carrying special offers, and looked dauntingly difficult to negotiate. Letting the glass door swing shut behind her, she instinctively reached down to pick up the baby, then hesitated as she looked at Harry’s peacefully dreaming face, his brow smooth and untroubled, his eyes gently moving under their pink translucent lids.

‘Oh God, I can’t wake you up again, I just can’t,’ she muttered under her breath. She sighed, then parked the pram just inside the entrance where she could keep half an eye on it, pushing her foot down to lock the brake in place. She bent down and kissed Harry very lightly on a flushed, rounded cheek, then pressed her mouth to his unconscious ear and whispered gently, ‘It’s only a few things. You’re out for hours by the look of you. Won’t be a moment.’

She picked up her bag, collected a trolley and, making her way into the heart of the store, pushed it quickly but without enthusiasm down the aisle, bored by the very idea of the shopping she had to do, and wearied at the tiresome business of having to keep count of every price as she chose the things she needed. The cardboard boxes balanced on the shelves on either side towered over her in depressing brown walls as she collected tins of baby food and baked beans, and she looked away from them and down into the cabinets, where packets of frozen vegetables were piled in their plastic bags, each covered with a thin white film of frost.

She chucked two solid, icy packets of peas on top of the tins then stopped and pulled a small piece of paper from her pocket. ‘Now, what was it I knew I’d forget?’ she muttered as she stood in the middle of the aisle, studying the neatly written list, but with her other hand still firmly holding on to her small fake leather knapsack which she had rested on the handle of the trolley.

She instinctively gripped it even more tightly as a grey-haired woman wearing a padded coat like an eiderdown came round a corner and pushed past her, tutting a little as she did so. Anna looked up at the large pear-shaped figure as she waddled away towards the gravy powders, and threw a disinterested ‘What’s your problem, then?’ after her.

The woman stopped and turned to look back at Anna, whose small figure with spiky jet-black dyed hair, huge earrings and spindly calves, exaggerated by tight, black leggings and loose white shirt hanging down below a thick black jumper, was dwarfed by the mountains of goods on either side. ‘It’s people like you that’s the problem, love,’ she answered. ‘Learn some manners.’

Anna looked down at her list again, murmuring quietly, ‘Oh go fuck yourself.’ But she felt suddenly uneasy and glanced up towards the doorway. Her view was blocked for a moment by a blonde customer in a blue blazer coming through the door, but as the woman moved towards the stacked row of trolleys Anna was reassured by the sight of the pram still sitting where she had left it. She stuffed the list in her pocket and headed for the nappies.

Juliet turned back from the trolleys and moved quickly over to the pram. As she looked down she suddenly knew for certain what she had suspected when she had seen it through the large plate-glass window. The baby looked so sweet lying there in his blue baby-gro, so securely tucked in and peaceful that it seemed a shame to move him, but she knew she must. As she bent over the pram she breathed in his warm, milky, almost edible smell and felt her womb contract in sympathy. She pulled back the blue cotton blanket, gently slipped her hands under his armpits and lifted him up confidently on to her left shoulder, letting his head fall softly against the wool of her jacket as she held him with one hand and picked up the blanket with the other. He lifted his head slightly, making it wobble on its red, pleated neck, gave a little whimper and screwed up his eyes, then made a small sucking movement with wet lips before giving a tiny sigh and settling back into a deep sleep.

Juliet smiled to herself as she rubbed the side of her face against the fuzzy head, then pushed open the glass door and made her way quickly out of the shop. She tucked the cover round the baby with her free hand as she moved away from the supermarket and crossed the road, walking purposefully up the street and away from the shops: a tall, striking woman dressed in expensive-looking but creased blazer and trousers, her streaked blonde hair unkempt and wearing no make-up; the very picture of a harassed middle-class mother carrying her young baby.

Nappies were the last thing on Anna’s list, so after picking up a large economy bag of the three-month size, she began to make her way back towards the checkout, but stopped as her eye was caught by a display of chocolate sauces. She stood for a moment or two, adding up once more in her head the prices of the goods already in her trolley and considering half-heartedly whether a squeeze or two of chocolate would cheer up the quarter slab of vanilla ice cream she thought might be left over in the small iced-up freezer compartment of her fridge. In an effort to remember she tried to picture the open fridge but, instead of ice cream, saw the bowl of half-eaten baby cereal she had put there that morning, and started guiltily as it reminded her of Harry. As she turned to move on she glanced over again at the pram by the door and, as she did so, felt a spasm of shock roll up her body in a wave that broke at her throat in a little gasp of fear. She tried to identify what had caused it, and as she stood for a split second still staring at the pram, immobilised by anxiety, suddenly knew. It had moved. Only the smallest amount, but to Anna’s eye the change in angle was unmistakable. Unsure why this filled her with such foreboding, and praying that it had simply been knocked a little by a passing shopper, she left the trolley and raced down the aisle, her brain at first refusing to make sense of what her subconscious saw more clearly every second.

The baby’s face had changed colour.

It was flatter, creased – frightening.

By the time she recognised the empty bottom of the pram for what it was, she was screaming.

Michael Evans’ progression up the insurance firm where he had worked since leaving university had been fast and impressive, and the acquisition of a beautiful, clever wife at the age of thirty-four – a wife (as Michael hated himself for admitting he was a little impressed by) a notch or so above him in the social scale – had fitted neatly into a relatively smooth, happy and uneventful life. His Englishness, his emotional restraint – at that time enough to make some doubt that feelings of any real strength lurked under the dignified, correct exterior – attracted Juliet by its appearance of calmness and solidity. A man of few words, her mother had called him, not altogether disparagingly, and Juliet had loved that in him. His habit of thinking long and hard before replying to even the simplest question, bowing his head and placing his hands together against his lips like a praying saint in a mediaeval triptych, had amused her, and the reply that would eventually emerge was invariably coloured by a kindness and consideration for the questioner that contrasted comfortingly with Juliet’s less serene and more dissatisfied outlook on life. At their first meeting at a party in Kensington they had quickly homed in on each other, her elegant beauty and apparent confidence thrown up in shimmering relief against the background of city suits, sensible ties and brightly coloured frilled cocktail dresses that could have gone straight on to enjoy a few dances at Annabel’s before being gently but purposefully unzipped to allow a good grope in the taxi on the way home. Juliet’s naturally blonde hair, bobbed into a swinging, shining pelmet, her white silk suit and expensive but understated jewellery spoke of subtler and ultimately more satisfying delights. She looked stunning but – at least in the immediate future – unzippable. Michael was entranced, and she in her turn was drawn to the oasis of peace and wry amusement that he had hollowed out for himself among the loud, over-confident voices around him. They found themselves spending the whole evening together. Several more had quickly followed, including a few outings to the cinema and to small Chelsea restaurants, until there had come a night when, after a visit to the London Coliseum to indulge Michael’s taste for the less demanding operas, hesitant, respectful sex had followed in his small flat in Fulham. It soon seemed easier, and somehow the right thing to do, that Juliet should move in. Marriage followed within the year, and their lives settled into a predictable, comfortable routine.

Michael was a clever, honest and hard-working businessman, and Juliet’s job in an upmarket firm of estate agents was well suited to her good taste and persuasive manner. She was a popular and successful member of the team, but as she and Michael had known from shortly after their first serious conversation that they both wanted children, she only gave it a limited proportion of her attention and effort. She was quite prepared for a time when she would have to set her career aside – at least until the little Evanses were happily ensconced in the obligatory boarding schools – to concentrate on the important tasks of running a good home, nurturing an admirable, high-earning, respectable husband and bringing up a brood of future useful Englishmen – or women.

When they first moved into the neat terraced house in Battersea a few months after their wedding they both mentally set aside a small light room on the top floor as a future nursery, assuming its occupant would arrive within a few years as easily and comfortably as everything else had so far done in their short, enjoyable courtship and marriage. As time went by and no hint appeared of impending offspring, a tiny little feathery sensation of fear began to flutter occasionally deep within Juliet. After some nine years of conventionally happy, sexually active if unexciting marriage, the flutter had become the beat of heavy wings – and Juliet began to admit to herself that something unspeakable was hovering on the edges of her well-planned, smoothly run adult life, threatening to throw it off balance with the strong gusts of unease it created.

Although she herself was becoming increasingly aware of this shadow lurking at the edges of her everyday life, it was the reactions of those around her that made it difficult to carry on as if no problem existed.

Her mother, in particular, made her feel horribly awkward about the lack of babies and, never the most tactful of women, was extraordinarily accurate in pinpointing the most humiliating moments to drop heavy hints about this shortcoming in her daughter’s achievements. Juliet had once made the fatal mistake of quietly admitting to her that she and Michael were disappointed not to have so far produced any children, and she had regretted it ever since, sensing that – behind the show of sympathy and understanding – it had given her mother another little weapon to use against her.

‘Well, after all it’s not as if I had any grandchildren to leave it to when it comes to mine,’ Mrs Palmer volunteered in the middle of a discussion about wills at one of her dinner parties. As the average age of her guests, apart from Michael and Juliet, was as usual somewhere in the seventies, this jolly subject was fairly typical of those raised around the Palmer table.

‘Everyone should make one, of course,’ added Michael, carefully ignoring the reference to his lack of contribution to the family dynasty. ‘It’s surprising how many people don’t bother, and then leave their spouses with the most complicated situa—’

‘Yes, but I don’t have a spouse, you see. My daughter is all I’ve got,’ ploughed on Mrs Palmer, turning to smile sweetly at Juliet as she underlined her point with the subtlety for which she was famous, ‘all I’ve got. Apart from you, Michael dear, of course. It’s not as if there were any young ones to benefit from my savings. I’d always thought there might be schooling and so on to help with, of course. Even my dear dog isn’t with me any more.’

Michael and Juliet had adopted the Palmers’ black labrador three years previously. Mr Palmer’s death had meant a move for his widow from the large house in Hertfordshire to a London service flat, and to keep the family pet would have been impossible. Juliet, hating the idea of giving her away, had begged Michael to let the dog live with them, and in spite of it necessitating complicated arrangements for having her collected by a friend each day while they were at work, he had agreed. But Mrs Palmer saw the transferring of Lucy as entirely to their benefit, and had never once expressed any thanks for their having taken over the responsibility. At the time, Michael and Juliet had put it down to the recent bereavement, but as the years went by and Mrs Palmer still complained self-pityingly about the old dog’s. absence, Juliet found it increasingly irritating.

Her relationship with her mother was an extraordinary mixture of closeness and utter separateness, and it sometimes appeared to her that Mrs Palmer deliberately chose to hurt her in order to re-establish some kind of power over her. Juliet became adept at brushing aside the references to missing grandchildren, not only because she found them disturbing, but also because treating them with any seriousness made the awful possibility of a genuine problem more real.

But the afternoon she caught Michael looking longingly out of the window at some small boys playing football outside the flats that backed on to their house, she knew something must be done. She walked up quietly to stand just behind him, and followed his gaze towards the laughing children.

‘What is it?’ she asked, not needing an answer, but half hoping they could bring the unspoken problem out into the open.

He jumped guiltily when he became aware of Juliet behind him. ‘I was just wondering if I needed an overcoat. It’s clouded over again.’

‘Oh Michael, for heaven’s sake.’

‘What?’

‘You know.’

If Michael was worried enough to protect her from his consciousness of there being something wrong, then Juliet knew it was time she herself turned and confronted it. Later that evening she studied again the magazine articles and chemist’s leaflets that she had hoarded in her bedside drawer.

‘I’ve bought an ovulation thermometer,’ she announced as she came in from work the next day.

‘What?’

‘It’ll give me an idea when I’m ovulating, and we can make an extra effort, if you see what I mean.’

‘I see exactly what you mean. It sounds delightful. I suggest you take your temperature this minute,’ said Michael, as he threw his jacket on to the sofa and began to undo his shirt buttons.

‘Michael, what are you doing?’ laughed Juliet. ‘Don’t be so silly. It isn’t instant like that, as I’m sure you know perfectly well. No, stop it – I want to read the instructions,’ she said as she wriggled out of his grasp and sat down, moving his coat on to the arm of the sofa. ‘Now look – it’s in a sort of huge scale – see? So I can—’

‘Come here, my dear,’ Michael interrupted, as he sat down beside her and slipped a hand inside her blouse, ‘and I shall personally undertake a particularly thorough examination. I’m sure we can sort out your internal problems in a jiffy.’

‘Darling, shut up. Listen. My temperature will go up immediately after ovulating and – hang on.’ She read on to herself for a moment or two, frowning a little. ‘Well, that’s a fat lot of good, isn’t it? We’ve got to make love like mad just before and during ovulation, and my temperature’s going to go up just afterwards. What good is the thermometer if it’s going to tell me when we’ve just missed it for God’s sake?’

‘I can see a perfectly simple answer. We make love more or less permanently until your temperature goes up, take a few days off to get up our strength, then start again. Don’t you think?’

Juliet smiled but went on reading. ‘I’ve got to fill in the chart and put in little crosses when it goes up. Yeah, yeah, I see the point. I’ll get to know my cycle and all that. And I suppose at least I’ll know that I am ovulating.’ She turned to look at Michael. ‘I do love you, you know. Even if you haven’t got me up the spout yet. Come to think of it, who’s to say it’s me? Perhaps your sperm are a bit wimpish?’

‘Nonsense! They’re absolutely first class. Now come here and I’ll prove it to you.’

But after a few months of temperature taking, crosses on graphs and carefully timed sessions in the creaking double bed, Juliet appeared no nearer to producing the longed-for heir. Michael knew she minded more than she was letting on, and noticed an irritation creeping into her attitude towards him. For his part, the necessity of performing to order was becoming increasingly difficult and depressing: it became hard to remember a time when they’d had sex for the sheer pleasure of it rather than to meet the demands of a schedule.

‘You’re on,’ Juliet said to him one night as she brushed her hair at the dressing table. After six months of attempts at timed conception, this succinct, if uninspiring, phrase had become part of their regular routine.

‘Again? Are you sure?’

‘Why, don’t you want to?’

‘Yes, yes of course I do. Do you?’

‘Well, we don’t have any choice, do we? I’m not going to waste another whole month.’

Michael resisted snapping back at her, and only sighed quietly to himself as he pulled back the sheets and climbed into bed, trying to marshal his thoughts into suitably erotic directions, but feeling more like a sperm bank than a lover.

The evening of the day she went to see her GP was the first time she cried. He had been so matter-of-fact, so sensible, and so horribly in agreement that ‘Something should have happened by now.’ She had half expected him to laugh it off, to jolly her out of it and tell her to go home and not be so silly (a healthily pragmatic approach he had taken to many of her minor ailments since she and Michael had become his patients on their move to Battersea), but he had listened quietly and seriously as she told him of her fears, and she had seen in his eyes that there was to be no quick answer.

‘I’d like you both to go and see a Professor Hewlett,’ he said as she came out from behind the curtains after the examination and moved to sit in front of his desk. He made notes as he went on. ‘There’s no immediately obvious problem, but I don’t see much point in making you wait before taking this further. Standard advice after a first infertility enquiry is to go and try again for a year or so, as you may know, but having known you both for a few years now I’m sure you’ve been making love the right way up, so to speak, and certainly from what you tell me you’ve been trying often enough and at the right times for it to be surprising that nothing’s happened yet. Your cycle’s a bit longer than average, but it seems regular enough, and the chart seems to show quite clearly that you’re ovulating regularly. Go and see Bob Hewlett and we’ll take it from there. There are plenty of good chaps in this field now, but he’s seen a lot of my patients lately and won’t take you round the houses. I’ll get Jennifer to make an appointment and give you a ring.’

His mention of her periods took Juliet back to the time when they had disappeared, to memories of her anxious mother dragging her to the doctor at sixteen, painfully thin yet still refusing to eat normally.

‘You do know I was anorexic years ago?’

‘Yes, yes of course. You told me, and I have it here in the notes that Dr Chaplin sent on. That shouldn’t have any bearing on this at all. Your weight has been perfectly stable in the – um—’ he paused and looked down at the beige folder on his desk, flipping back several pages, ‘—ten years you’ve been coming to see me. Your menstruation was re-established a long time ago wasn’t it?’ Juliet nodded. ‘Don’t worry,’ he smiled up at her encouragingly, ‘there’s a long way to go yet before you need assume we have anything we can’t cope with.’

She was calm all the way home, telling herself over and over again that the doctor had found nothing wrong; that she was to go and see a specialist and that there was every reason to feel positive. But when she had to face Michael, the dark creature that had so far only made itself known by occasional forays into her conscious mind seemed to grow and rise up and fly at her from the front. It was the way he looked up at her anxiously as she walked into the sitting room that made her give way.

‘How did you get on? What did he say?’

‘Oh Michael – there’s something wrong with me. I knew it – I knew it. There’s something horribly wrong.’

She threw her coat on to the sofa and sat in the armchair, leaning forward on to her knees and rubbing at her temples in an effort not to cry. Lucy padded over to her and sat down beside the sofa and licked her hand, sensing unhappiness.

‘Why, what did he say? Juliet – tell me, please. What’s wrong with you? Can they do anything about it?’

‘He didn’t find anything really wrong. It’s just that—’

‘Well then, that’s OK isn’t it? And who’s to say it’s you? It could be my sperm, you know. What did he say?’

‘Oh do stop asking me that! I just know something’s wrong, that’s all. I told you there was. I’m never going to have children, Michael, I can feel it. Oh God, what am I going to do?’

She burst into heaving, sobbing tears, and the whole world seemed to be focused on her empty, useless womb.

It was hard for the policeman to understand what Anna was saying through her hysterical tears. When his radio had first alerted him two streets away he had assumed that yet another car had been broken into, or a purse snatched: the theft of a baby was quite outside his experience and the painful distress of the babbling, wild-eyed girl in front of him was deeply unsettling.

‘Come and sit down for a moment, love,’ he said as he tried to shepherd her gently away from the doors of the supermarket. Then you can tell me calmly exactly what happened and we’ll sort things out. Don’t worry, love – we’ll get your little one back, he can’t be far.’

But Anna couldn’t move. She was clinging desperately to the pram with one hand, and with the other she rubbed her cheek with repetitive movements that seemed to be trying to tear the skin from her thin, white face. The swollen eyes and blotchy, roughened complexion gave her the look of a wizened old lady and there was a bitterness set into the downward lines around her mouth that PC Anderson guessed had been etched there long before today’s drama. She had clearly had to face obstacles before, but now she looked as though she might be torn apart by the intense suffering suddenly thrust upon her from nowhere. The dense black make-up around her eyes was smudged and running, giving her the look of a frightened panda.

‘I’ve g-got to go and – and – and find him!’ she stuttered in a strong Glaswegian accent, easily discernible in spite of her gulping sobs. ‘My baby! My baby!’

As she let go of the pram and made a sudden, darting move towards the door, PC Anderson grabbed her by the shoulder and turned her back to face him. Her eyes were wide open and terrified and sweat was breaking out on her face and neck; he could see that she was in danger of collapsing if he didn’t manage to get her to sit down quickly. He kept his hand on her shoulder and with the other behind her back, ushered her firmly through the checkout.

A gaggle of assistants was hovering around the tills, their excited faces alternating between interest and sympathy, revelling in spite of themselves in the drama of the situation and in the excuse for a break in routine.

‘Stand back, ladies, please. Thank you. Now, love, where’s your manager? I need a quiet room to go and have a chat with this young lady. And I don’t want any of you to leave without telling me, all right? I may need to have a talk to you. One of you bring that pram with us, please.’ He turned as he became aware of a large, flustered woman advancing towards them, wiping back a flopping piece of startlingly red hair from her forehead.

‘Come with me, please, constable. I’m Mrs Paulton, the under-manageress. There’s a room at the back where you can be on your own. I’ll bring you both a cup of tea. Poor thing!’

Both Anna, still juddering and hysterical, and PC Anderson followed the comforting shape of Mrs Paulton towards the back of the shop. As Anna passed packets of cornflakes, rice and washing powder she could feel a part of her brain vaguely wondering how they could still exist in this new universe in which she now found herself. Did people still eat? Did they still wear clothes, and get them dirty? It didn’t seem possible. If Harry wasn’t with her then surely the world as she knew it had stopped, turned upside down and shown its murky underbelly.

As Mrs Paulton sat Anna gently down in the back room, the policeman waited outside in the corridor and radioed a quick message to his communications centre, aware that the simple words ‘alleged child abduction’ would ensure immediate action.

‘Right now, love, what’s your name?’ he asked as he came into the room and squatted down beside Anna.

‘Anna Watkins.’

‘And tell me exactly what happened.’

‘I only left him for a second. I just needed to get a few things and he – oh God, I’m sorry, I’m so sorry, I didn’t mean to leave him, I love him so much. Oh Jesus, what am I going to do?’

‘Come on now, love, there’s no need to get so upset. The sooner you can tell me what happened the sooner we can get him back.’

‘They’ll take him away from me won’t they?’

‘No, no love, come on now, no one’s blaming you for anything. Just try and tell me everything you can. What was your little one wearing? What’s his name? Did you see anyone near the pram?’

The baby was starting to cry. As Juliet continued to walk quickly along Streatham High Road he began to twist and squirm in her arms, turning his face round and up towards her, his mouth sucking and puckering, his eyes open and filling with angry, hungry tears.

‘All right, darling,’ she muttered into his pink coil of an ear, ‘it’s all right, Mummy’s here. We’ll soon get you home.’

But even if it had been true, it wasn’t home Harry was after, but food.

Chapter Two (#ulink_2a6fd443-8be7-5da2-99e2-38b9e70a3197)

‘Please, please stop crying. Mummy’s going to get us home very soon and then we’ll wait for Anthony to come. Won’t he be pleased to see you’re safely back again? Mummy lost you for a bit didn’t she, and Anthony was very angry. Everything’s going to be fine now, sweetheart, and we’ll all be happy again. Please try to stop crying, darling, please try. Sshhh now, quiet now, come on, stop it now, sweetheart. Stop the noise. Mummy’s here.’

Juliet had reached her parked Volvo with an increasingly complaining baby and having placed him in a large shopping basket on the back seat was driving quickly out of Streatham in the opposite direction to the supermarket. His persistent wailing was disturbing her in a way that was more unsettling than anything she had felt for a long time and she couldn’t understand why the stomach-wrenching sensation it produced in her was so familiar. She had been through this before, but in an altered form, in a world the mirror image of this one, darker and more closed in. Where was she when she had felt this, many, many years ago? As she drove on, carefully following her planned route, she remembered: it wasn’t a child’s crying that this terrible sound was dragging up from her past – it was her own. She could hear again the sound of her wailing as she had heard it echoing round her head while they had held her arms and legs in the hospital to stop her running. The more she had wriggled and screamed, the tighter they had gripped her emaciated body, bringing the spoon with its unacceptable contents time and time again to her mouth, pressing it against her lips until she could taste it, or tipping its load into her open, sobbing jaws until she gagged, choked and swallowed in spite of herself.

She turned around to look at the baby on the back seat, but could see only the brown wicker ordinariness of the basket, showing no sign of its extraordinary contents. It was comforting, and she shook her head a little to rid herself of the unwelcome memories that had broken through, unbidden, into the present. She would leave these thoughts till later, until she had reached safety for herself and the baby. Then she would have time to unpack her brain and slowly pick over the contents until she could face them properly and exorcise them; for the time being she would let them hover harmlessly in the pending section of her mind.

Anna had lapsed into a defeated, miserable calm, and was doing her best to give the policeman the information he needed. She was a girl of innate intelligence and a natural toughness which had stood her in good stead through a life that had not been easy. Had she been dealt better cards originally, she would have played them well and avoided the traps set for her by others who appeared to hold all the aces. She had been born into an area of Glasgow that had rid itself of the slums of the fifties and sixties, only to find itself inhabited by an even greater threat. A new, insidious culture was breeding and spreading in the perfect medium of unemployment and poverty, filling the dish that was this small pocket of crowded, inner city life with spores that were ready to break loose and find new areas to infect and ultimately destroy. The figures huddled in corners of Hyatt’s estate no longer discussed the buying and selling of watches or gold jewellery, but of cocaine, crack and heroin. The drug scene had become a way of life: the added threat of HIV had brought a new edge of despair and hopelessness to its victims and even those on the fringes of this miserable, pervasive trade – such as Anna and her family – were touched by its contaminating effects.

She sometimes wondered if her early memories of her father, Ian, were imaginary. She was uncertain whether she had invented the times when the house felt happy; when he didn’t shout at her mother, when she and her younger brother, Peter, were given hugs from him at bedtime and treats at weekends. Years of watching perfect families in her favourite television series – when she had wanted to be like them so much that she had sat in front of the set, screwed her eyes tightly closed and prayed and prayed to be taken into the screen and into their lives – had confused her.

But her memories were right. It was only after years of being unemployed since the closure of the tobacco factory where he had worked for over two decades that the morose, defeatist side to Ian Watkins’ nature was released, producing a bitterness that resulted in a lack of kindness and affection to his wife and two children that amounted to cruelty. The bitterness had infected his children: Anna made no real friends at school, and alienated her teachers with the harsh cynicism she expressed with sharp intelligence.

She had always known she would get out of the family home at the earliest opportunity, and the continued daily diet of television for her and Peter had helped to instil in her the illusion that if she could only get herself ‘down South’ she would be able to make something of her life, and even return in glory after a few years, bringing back fame and fortune as in the fairy tales she had read to herself as a young girl.

At the age of fourteen she began to plan her escape. She took on an early morning paper round and started to save the small amount of money that it brought in, and in spite of her father’s insistence that it was to be given to her mother to help with the bills, she managed to lie sufficiently well about exactly how much she was making to be able to put tiny amounts aside in a tin on top of the old-fashioned wardrobe in the bedroom she shared with her brother.

At sixteen she packed her few belongings into a carrier bag in the middle of the night, emptied the tin into her purse and left, making her way down to London by hitching lifts and buying just enough food to survive. Her family made rather half-hearted attempts to find her, but deep down her mother recognised in herself an envy at Anna’s freedom, and knew that even if they did succeed in tracking her down, they had nothing to offer which could persuade her to return. Only Peter was truly sad at losing her, and cried himself to sleep for many nights in their room. For months he waited for some news of her – a letter or call – but gradually began to face the fact that she was gone from his life for ever.

It didn’t take long for Anna to discover the reality of trying to survive in a large city where jobs are impossible to find unless you have a permanent address, and where a permanent address is impossible to find unless you have the job to pay for it. Having no family or friends to turn to, she found that the helping hands she was offered tended to come with invisible and insidious strings attached. Not that she was sexually inexperienced, having had several rushed and unfulfilling encounters after originally losing her virginity at fifteen in the back of a van, but she was streetwise enough to be suspicious of every stranger she met.

She inevitably found herself clinging to the first person who spoke to her with what appeared to be genuine warmth and kindness, knowing that his motives might not be entirely altruistic, but unable to resist basking in the gentleness of his tone and the comfort of his arms around her at night. This was Dave, an eighteen-year-old from Brighton. Having made his way, like Anna, to the streets of London, he had found them paved not with gold but with crumbling, unwelcoming concrete. They met in Piccadilly Circus, where many of the homeless gathered to watch the world go by or to intoxicate themselves into a senseless, or at least differently sensed, stupor in which they could then see it through the comforting haze of drugs or alcohol. Anna, having run away from Glasgow partly to escape the effects of the drug culture, found herself straight back in it, and it soon became clear that Dave himself survived by pushing relatively small amounts of crack and ecstasy around Wardour Street and Soho Square. She added to their meagre finances by begging, something she could only allow herself to do by telling herself, in a piece of tortuous logic, that at least she was going out and finding the money herself, and that it was better than living off the state.

When every penny is a struggle to find, even the smallest expenses become difficult. Anna soon convinced herself that as Dave was sleeping only with her, and as she believed his tales of relative monogamy prior to their relationship, condoms were a luxury that could be dispensed with. She had a vague idea that they were being handed out free somewhere locally, but never got it together to find out where or to bother to do anything more constructive about protecting herself. As a girl who had grown up knowing several friends who’d either had full-blown Aids or were HIV positive, she knew she was taking a calculated risk, but strangely enough the more obvious, and more likely, outcome of a pregnancy never seriously occurred to her.

She put off confronting her condition for months. Somehow in the mess of her life, the lack of periods and the sickness assumed an insignificance they would never have had if other more pressing physical problems hadn’t had to be faced. Anna’s priorities were finding her next meal and a place to sleep without compromising herself with what she saw as the ‘system’, and the momentous change taking place in her own body almost appeared to be part of someone else’s life, belonging to a future that seemed unreal. Perhaps she also knew, without admitting it to herself, exactly what Dave’s reaction to prospective fatherhood would be, and hoped that by ignoring her condition, she could make it disappear. But of course it didn’t. Anna’s impoverished and undernourished body nurtured the tiny uninvited guest in spite of her, and the embryo that was Harry grew and grew until, demanding more space, it began to make her belly swell.

She was right about Dave. Struggling unsuccessfully to take responsibility for his own life, there was no way he could countenance taking on another one, and as soon as Anna had reluctantly confirmed what he had been beginning to suspect, he was off. Anna wasn’t surprised to find herself abandoned – she felt herself destined to be so, and it only seemed to fit into a pattern which had been laid out for her from the start. Perhaps it added another little brick of bitterness to the defensive wall with which she encircled herself, but she almost enjoyed the sheer predictability of it, and if she had believed in God would certainly have been tempted to congratulate Him on the thoroughness of His planning when it came to a life of unhappiness and hopelessness.

Her small effort at coming down to London in order to better herself had landed her in even greater trouble than before; now she saw no possibility of the imagined successful job or marriage, and resigned herself to a future of poverty and dependence. Since her arrival she had thought very little of home, managing to keep her mind carefully turned away from worries about Peter or her mother, frightened that to start on that road would lead her only too quickly towards a horizon of unbearable loneliness. But now the pull of the past was almost irresistible. She admitted to herself for the first time how much she missed not only the two of them, but also, to her own surprise, her father.

She considered an abortion, of course, but having let matters drift for such a long time she knew it was very late for that and, with the loss of Dave, she was already beginning to think of this mysterious lump inside her as her one ally against the world. She was also realistic enough to know that the existence of a baby would secure her some sort of housing, and for once she allowed herself to join the system and accept help. By the time she made the fatal shopping trip when her whole world was to be turned upside down, Lambeth Council had settled her in a high-rise flat in Streatham, where she managed efficiently, if uncomfortably, on benefits. And where she lived for one reason only – to love and protect the little boy who had come to mean everything to her.

The awe-inspiring medical charisma of the Harley Street and Wimpole Street names has been lent so generously to the lesser-known streets that cross them that over the years the houses using the addresses of their more illustrious neighbours have stretched further and further around the corners in a proliferation of ‘A’s and ‘AA’s until they almost meet halfway between the two streets, leaving only a handful of correctly named houses between them. The address of Professor Hewlett’s clinic was officially given as ‘Harley Street’, and so it took Juliet and Michael several minutes to find the pillared white house round the corner in Weymouth Street, separated by at least four houses from the junction. They were surprised by its ordinariness, perhaps expecting the building to show some outward sign of the extraordinary events that took place behind its unrevealing walls.

It would have been hard to imagine a less clinical setting. The hall was carpeted and lit by chandeliers, but the air of luxury was mitigated by a large, practical reception desk placed across the entranceway, almost hiding the two computer screens and the smiling girl positioned behind its high wooden façade. ‘May I help you?’ she enquired, with scarcely a hint of the adult-talking-down-to-child tone that Juliet tended to expect from anyone in the medical world when addressing a patient.

‘I’m Michael Evans, and this is my wife. We’ve come to see Professor Hewlett.’

Juliet looked up quickly, half anticipating a look of pity and superiority on the girl’s face, but catching only a smile of genuine warmth and apparent understanding. She felt Michael’s arm move to rest on her back, as if he sensed her wariness.

As they were ushered into the waiting room and towards a large, comfortable sofa, Michael was puzzled by his sense of being in a fast food restaurant. Why did he feel he should be ordering breakfast? He looked up at what he had been aware of on the edge of his vision: a series of framed photographs of the medical team and staff was hanging on the wall, each subject wearing a cheerful, positive smile and bearing a name, qualifications and a job description. They looked so extraordinarily ready to burst into efficient enquiries as to what Michael would like to order (‘Eggs, sir? Will that be fertile or infertile, sir?’ ‘Just twins to go, please,’), that he had to shake his head to remind himself where he was.

In the armchair opposite sat a balding man of forty-five or so. He was leaning forward, resting his arms on his knees and holding one hand to his forehead, not moving or glancing up as the newcomers sat down. Michael reached for Juliet’s hand and gave it a little pat. He wanted to say something reassuring but felt the sound of his voice would intrude on the quiet, slightly melancholy atmosphere, and contented himself with a small clearing of the throat.

‘Don’t,’ whispered Juliet.

‘What?’ he whispered back, half aware of the man in the chair, who still hadn’t stirred. ‘Don’t what? Cough?’

‘Sorry, it doesn’t matter.’

They sat on in silence for a few minutes. A nurse walked in and over to the man in the armchair. She bent down and murmured something by his lowered head. Michael heard a muttered ‘Oh Christ,’ then, ‘Yes, yes all right. In a moment.’ After a few more words in the man’s ear, the nurse straightened up again and walked towards the door, turning to give him a sympathetic smile as she left. He raised his head and looked after her, then with a sigh rose slowly to his feet and stretched his arms behind him before giving them a little shake. He slowly walked out, still never glancing in the direction of the sofa.

‘Poor chap.’ Michael lifted his hand off Juliet’s and, in order to have an excuse to do so, dusted some imaginary specks off the shoulder of his jacket.

‘Why?’

‘Oh, I don’t know. He just looked a bit bloody miserable that’s all.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, I don’t know, he just looked a bit miserable. You know.’

‘How could you possibly know that? How could you possibly know that a man you’ve never seen before in your life and have only seen now for about two and a half minutes is “bloody miserable” as you put it? God, you’re so irritating sometimes!’

‘Julie, I understand how you’re feeling, but there really isn’t any need to be quite so unpleasant. I was only passing a conversational thought. It wasn’t meant to be in any way serious and I—’

‘Oh all right, all right.’

She dropped her head and Michael could feel the welling of despair in the slight figure next to him. He felt the familiar stab of the intense pity and love that overcame him every time he was reminded of just how deeply she was wounded by her childlessness, and of how much pain it caused her at the slightest provocation.

He put both arms round her and let her head fall on to his chest, laying his cheek on her beautifully dressed hair and smelling the familiar mix of perfume and faint shampoo. ‘It’s all right, darling. It’s all right. We’re going to sort it out, you wait and see.’

‘I’m so sorry, Michael.’

‘I know, I know.’

And she was. Sorry for her short temper, sorry for the way she snapped at him and took out her frustration on him – this kind, tolerant man she depended on and took so much for granted. Years of familiarity had made her careless of his feelings, but at times she could see only too clearly how she treated him, and she hated herself for it. The strain of the past months of making love to order had told on both of them. Even the simple gesture of holding each other had become inextricably linked with their determined attempts to conceive; it was hard to remember a time when they’d had close physical contact for the sheer joy of it.

‘It’s not you. I just can’t bear myself, you see.’

‘I know.’

‘No, I’m sure you don’t. You’ve no idea how I loathe myself most of the time.’ She was looking up at him now, still in his arms but pulling away slightly, not crying but with such despair in her eyes that Michael thought it must be only seconds until she was. ‘I feel so empty, and so foolish – it’s hard to explain – as if I’ve just been pretending – how can I—’

‘Pretending what?’

‘I don’t know how to – pretending to live. Pretending I was getting up, pretending I was going to work. No you don’t know what I’m talking about, of course you don’t. I mean – I’m a sham. I’m not real.’

Apart from the necessary discussions about the love-making cycle, it wasn’t often that the subject of the non-existent child was touched upon openly now. For most of the time it was left as an unacknowledged hollow at the base of their marriage, only occasionally referred to obliquely by Juliet as in, ‘Well, at least we don’t have baby-sitter problems.’ Or, ‘I don’t suppose we’d be able to afford this holiday if things had gone according to plan.’ The small upstairs room had always been called the nursery, and the name had become so familiar and ordinary that neither had thought to stop using the word when it became less and less suitable. They had discussed things enough to confirm a willingness on both their parts to pay their way out of the Situation if it were possible, but it always filled Michael with hope when he felt Juliet was trying to put across to him how she really felt. These moments often seemed to follow patches of intense irritation with him, as if something in her was fighting every inch of the way against revealing her true feelings until they burst out of her unbidden and released themselves in a wave of weeping.

It was this intense distress of Juliet’s that made it so difficult for Michael to talk about his own sense of inadequacy and loss. For a man who liked to think he was rational and in control of his feelings it amazed him how much guilt he, too, felt at his failure to produce the required son and heir (it never occurred to him to wonder why he always imagined his offspring as male). But it was more than that – he had unexpectedly found a deep sadness within himself at the thought of never carrying his child in his arms, never kicking a football in the park with a miniature version of himself, never proudly watching the young Evans collecting his degree. As time went by his thoughts became almost biblical: phrases such as ‘Fruit of his loins’, ‘Evans begat Evans’, ‘Thy seed shall replenish the earth’ rattled round his head. The child became a clear picture in his mind until he could have described every detail of hair, figure, expression and face as if the boy really existed. Sometimes he felt he was going mad, but comforted himself with the realisation that this life of the imagination at least gave him a release of emotion which might otherwise have unleashed itself on Juliet.

Even at work he remained good-natured and outwardly at peace. He sometimes envied the ability of his colleagues to release their frustrations in outbursts of swearing and shouting, marvelling at their capacity to show strong emotion on such subjects as parking fines or politics. He thought with amusement of how violent, on a scale ranging from parking meters to childlessness, the manifestation of his own unhappiness would be if it truly reflected the deep wells of despair buried inside him. Not that his restraint made him seem in any way weak or inadequate; on the contrary his gentle but slightly cynical analysis of office problems betrayed a wisdom and maturity that were clearly lacking in the overheated reactions of those surrounding him. His childhood in Nottingham, as the bright-eyed boy of the manager of a furniture shop and a piano teacher mother, had led him to be aware, from his entrance into the local grammar school to his departure from Manchester University with a degree in economics, of how much was expected of him. Ever since seeing his parents’ anxiety at his admittance of any blip in the smooth upward curve of the life they had planned for him, he had learnt to keep his worries to himself.

But the distress over the non-existent child was different. For the first time in his life he felt the lack of any kind of real escape valve for the emotional pressure building inside, but was inhibited by his keen awareness of her own suffering from unburdening himself to the only other person who would be completely in sympathy. He found himself becoming increasingly attached to Lucy, the labrador, but consciously steered clear of imbuing her with too many human attributes, having seen in other couples how easily a pet can become a child substitute, involving, in his eyes, a lack of dignity for both parties.

As it was, he liked to think that Juliet was unaware of just how much he minded, and concentrated on supporting and cheering her.

This policy may have been a mistake.

Chapter Three (#ulink_c79c1a81-2e78-5a6e-a8fa-3e867ecb0adf)

‘And?’

‘Polycystic ovaries.’

‘Poly-what-ovaries?’

‘Cystic.’

‘Oh, right.’

There was a pause while Harriet let this mysterious information sink in.

‘And is that bad?’

The two women stared at each other for a moment, then Juliet made a face. ‘Well I suppose so.’ She went on looking across at her friend, then they both laughed. ‘Well, evidently.’ They laughed more. ‘How would you like cysts on your ovaries’. Not just one, mind you, not just your monocystic, but the full poly. It’s not madly glamorous is it?

Harriet was giggling now, bending over in her chair, relieved to see the old Juliet emerging once more out of the midst of this alien affliction. And Juliet was laughing in relief too, knowing this was the only person she could ever talk to in this way, able to unburden herself without facing the over-solicitous reactions of Michael or the demanding worry of her mother. She was always smugly aware of Harriet’s envy of her own happily surviving marriage, but Juliet’s searing jealousy of her friend’s two children counterbalanced it, giving them a spurious emotional equality. Juliet had sometimes imagined a world where the two of them could combine – a creature half-Harriet and half-Juliet; the perfect happily married mother of two. The other halves – merging to create a woman not only abandoned but also barren – could wander in some eternal limbo for those that don’t fit, for those that break too many of the rules of social acceptability.

‘No, but I mean what can they do about it? Can’t they sort of scrape them off or something?’ This produced another burst of giggling. Harriet scooped her long brown hair (too long for thirty-five as Juliet sometimes idly considered telling her) back behind her ears and wiped smudged mascara from beneath her eyes.

Juliet leant forward and spoke more quietly. ‘You should see how they look inside you, it’s really bizarre. They said I had to have a scan, so of course I thought it would be like the ones you had with Adam, but it’s completely different.’ She pictured herself back on the couch in the small dark room in Weymouth Street; the radiographer had explained what was going to happen, but she had still been taken aback by the jellied penis-shaped instrument with its ultrasonic eye inserted gently into her vagina to gaze unashamedly up and around her womb and ovaries like an all-seeing joyless dildo.

‘God, I just feel so pleased that they’ve found something. I don’t care what I’ve got so long as there’s something I can do. I should be dark, fat and hairy apparently.’

‘What?’

‘The typical polycystic woman is large, dark and hairy. But not always. Obviously. Can I have another glass of wine?’

‘Of course.’ Harriet stood up and reached across the coffee table between them for Juliet’s glass. ‘It’ll have to be the Bulgarian red now, that’s all I’ve got left. Are you sure you’re allowed to drink by the way?’ She moved towards the small kitchen, collecting an old newspaper and abandoned toy gun as she went.

‘Oh don’t be so silly, Hattie. Believe me, if I get pregnant I shan’t touch a drop, but at the moment they tell me anything that helps me to relax is good.’

‘OK. Fine. So how did you get these things?’

‘They didn’t exactly say.’ Juliet stretched in her chair and looked around the comfortable, untidy sitting room. Harriet’s second-floor flat in Pimlico had been a refuge for many years now, in spite of the painful reminders of babies and then, later, of young children that were invariably scattered about. ‘Where are the sprogs?’ she asked.

‘Peter’s got them for the weekend. They’re taking them to Chessington today I think. The ghastly Lauren likes fast rides apparently. She would, of course. Another point to her.’ She was calling from the kitchen, and Juliet thought how little bitterness suited her even from a distance. Her voice always changed tone when the ex-husband or his new love were mentioned, reminding Juliet of the early days at school when Harriet’s sneering and bullying had been so impressive and had made all the girls want to be in her gang. Only after the two of them had been friends for two or three terms had Juliet got to know her softer side which, as Harriet relaxed into the routine of boarding-school life, had become increasingly dominant – until eventually it was Harriet to whom Juliet turned for comfort and advice, and who took her completely under her wing and used her dominance protectively rather than aggressively. It was Harriet who had first realised that something was very wrong as she had watched the skeletal Julie undressing in the dormitory; Harriet who had seen the pocketed food, heard the retching and groaning from the lavatory late at night. Although she had been too young to put a name to it she had sensed very quickly that her friend needed help, and that something quite dangerous was inhabiting her, subtly changing her not only physically but also from within.

The pair had remained friends after they left school. Long indulgent letters were exchanged between Harriet’s bedsit in Paris, where she was taking an interesting but unproductive Fine Art course, and Juliet’s university flat in Exeter, descriptions of suitors dominating the narrative, detailing their prowess in activities ranging from electrical repairs to love-making. But when Harriet met Peter over coffee in the Louvre, a change in tone crept into the letters and Juliet soon sensed love in the air. Back in London a couple of years later they had married, and the original hard and dissatisfied little girl was buried beneath a mound of glorious and uncomplicated happiness.

Juliet had envied Harriet’s complete abandonment in love. Peter was her world, and it was quite startling to see how Hattie adored him. It was the sort of love, Juliet supposed, that most people find only once in a lifetime, and some never find at all. Her own feelings for Michael seemed so contained in comparison, and Juliet often idly wondered if what she felt for him perhaps wasn’t love at all, but a convenient liking and companionship which, overlaid with the glitter of lust, had appeared to be deeper and more important than it actually was. But when the phone call had come from Hattie late that night; when the strange, thick voice had told of her misery at Peter’s infidelity and of her utter hopelessness faced by a future without him, Juliet had had enough of a glimpse into the open soul to see the torment that is always waiting on the other side of such all-encompassing love.

She had thought, gratefully, never to know it herself.

Juliet abandoned the car deep in the recesses of a public car park in Streatham and took from it a large brown holdall and the precious shopping basket with the thankfully sleeping baby in it, and carried them outside. It was almost dark, and she instinctively kept away from the streetlights as she walked quickly towards her destination. A lucky chance had led to her discovery of the semi-derelict house in Andover Road some weeks before; several wrong turns taken unthinkingly while coming back from a shopping trip had led her deeper and deeper into the unknown territory. She had pulled over to the side of the road and taken out her A–Z, but had soon found herself lost yet again in the thoughts that were then dominating nearly every waking moment. Gazing up at the row of abandoned houses alongside her she had sensed a solution, and had begun to formulate her terrible plan.

Now at last she was here. She had her baby back and all else would soon fall into place; when she was ready she would call Anthony and he would come, of that she was sure. Checking both ways to make sure that no one saw her, she slipped down the path along the side of the house and forced her way in through the broken door at the back, then climbed the stairs to the first floor. Once in the large front room she took a car rug out of the holdall, gently lifted the baby from the basket and then placed him carefully down on the tartan wool. He stirred a little in his sleep but didn’t wake, dreaming now of food instead of crying for it; feeling in his dream, rather than seeing, the comforting embrace of his mother and the rush of sweet, warm milk. His brain was as yet filled only with sensations and needs, with emotions, pictures and desires, with no memories older than a few months.

Juliet undid the poppers of his baby-gro, slipped it off his shoulders and rolled it down over his arms and legs. She pulled open the sticky tabs of his nappy and slid it from beneath his body, wincing a little involuntarily at the strong smell of ammonia. He stirred and whimpered. She looked down at his naked form, lit only dimly by the orange light from the lamp post that stood a few doors down the street, and found herself quietly crying. She bent her head to kiss him on his rounded belly, then laid her cheek lightly against him, not letting any of her weight rest on him, but touching him just enough to feel the warm beating softness.

‘Oh my dearest, dearest darling. Oh my sweetest darling. Oh my lovely baby.’

She lifted her head again to look down at him, seeing the gleam where her wet cheek had pressed against him, then as she gazed at him began to feel frightened. She sat up quickly and took off her blazer and laid it over him, panicking at the thought that he was cold. It was very quiet, and the silences between the baby’s whimperings were only broken by the noise of occasional cars turning into the small street, throwing odd swinging shadows from their headlights on to the walls and ceiling of the room as they negotiated the nearby corner. The whiteness of their lights and the thrust of their engines cut through the orangey quietness in sudden bursts of intensity, stirring the unease inside her, and leaving her each time more threatened by the silent darkness in between. She had never before been inside the room, but had assumed it would be completely empty, and only now did she begin to wonder what unknown objects were lurking in the corners, or what remnants of human occupation might be mouldering in unsavoury piles in the shadows. ‘Dear Lord, let him come soon. Let him come,’ she whispered, then closed her eyes, covered her face with her hands and swore quietly to herself, ‘Oh fuck it, fuck it, I haven’t told him yet have I? How can he come when you haven’t told him? Pull yourself together, Juliet, think it through. He’ll come when you tell him.’ She kept her face covered and breathed in the warm sweatiness of her hands mixed with a sharpness from the baby’s urine.

Then, as she knelt beside the baby, head still buried in her hands, eyes tightly closed, she heard something. Without moving her head, she snapped her eyes open behind her covering palms as she flinched and held her breath. She heard it again: a rustling behind her. Not daring to move for fear of what she might see, she kept completely still and focused every effort on listening, feeling her stomach clench in fear. Nothing. She could hold her breath no longer and began to let it out as quietly as she could, straining to listen as she exhaled, hearing only the smallest sound of her own breath escaping into the room, and of the baby’s fast, even breathing. Then – something again – a whisper of a rustle this time, still behind her, and a small dragging sound. As she turned and brought the hands down from her face, she saw the large figure of a man rising up out of the shadows in the corner and at the same moment she opened her mouth to scream.

Chapter Four (#ulink_9104bb39-2a11-5867-96a7-907f6164efbd)

Michael and Juliet were quite taken aback when Professor Hewlett suggested IVF treatment. Test-tube babies were something you read about in the newspaper; something that happened to other people, like plane crashes and lottery wins, even something to be slightly disapproved of as unnatural and unnecessary. Back in the large, comfortable consulting room after the results of all the tests had come through, Juliet had tried hard to listen once more to the details of the condition of her ovaries and the problems with hormones, egg quality and elevated levels of this or that substance, but it wasn’t until towards the end of the consultation when the words ‘in vitro fertilisation’ hung in the air that she really tuned in. She sensed then that, although the professor was giving her and Michael every opportunity to feel they were taking some active part in the decisions and alternatives that appeared to present themselves at every turn, they were being guided inexorably towards a particular treatment and that if they did nothing but nod and appear to be following the arguments they would slowly but surely be set on the extraordinary course that must lie ahead.

‘We’ve had considerable success with using IVF in cases such as yours, and thirty-five is a good age to be trying. After thirty-eight or thirty-nine the eggs do tend to be of lesser quality, as I think you know, and although we have many successes after that age – and indeed over forty – you stand a higher chance if you start immediately. My inclination is not to go through the laser or diathermy route with your ovaries, I have a feeling we’d be wasting precious time and there are other factors which lead me back to IVF. We’ll have to monitor you very carefully as there’s a higher risk of overstimulating the ovaries when they’re polycystic, but as I say we’ve had considerable experience with other cases just like yours and I’m very happy to treat you along these lines. You’ll obviously need to discuss this between yourselves and you may feel you’d like a chat with your GP, but I see it quite clearly as the best course of action . . . I’ll get Sally to give you some leaflets and of course I understand that you’ll need to consider the financial implications.’

A strange sensation in the pit of Juliet’s stomach was puzzling her, exciting her, and she turned her thoughts inward to confront it. As Professor Hewlett paused and looked at her she felt she was expected to ask all sorts of intelligent, relevant questions, but for a moment she had to indulge herself in examining this little spark in the very middle of her being. She smiled to herself as she recognised it for what it was; something long forgotten but comfortingly familiar after such a long absence – hope.

Sensing that the appointment was nearing its close, she bent to pick up her handbag from the floor next to her chair, letting her hair fall forward over her face to hide the smile, then brushing it back with her hand as she straightened up again. ‘I don’t think we need even to discuss the money, do we, Michael? I’d just like to get going as soon as we possibly can.’

Michael nodded. ‘Absolutely. It’s not as if we’re rolling in it or anything, you understand, but this is more important to us than anything else. We’d sell everything we’ve got.’

‘Let’s hope it won’t come to that.’ The professor smiled at them as he rose and moved from behind his desk. ‘But it’s very important that you understand exactly what you’re doing and that it’s not going to put too much strain on you both. Now, let me find Sally for you and we’ll see if we can start sorting things out.’

Husband and wife walked back to the car in silence, both deep in their own thoughts but each comfortingly aware that the other was thinking about the same thing. Michael slipped his arm round Juliet’s shoulders and she snuggled against him as they made their way along Weymouth Street and round the corner into Wimpole Street. When they reached the blue Volvo parked sedately in its ‘Pay and Display’ space, she looked at him across the roof as he took out his keys and pressed the button on the small black box that was attached to them. Nothing happened and he pressed it again, and then again, as he waved it vaguely around in the hope of directing its invisible beam more effectively.

She rested her hands on the car roof. ‘What do you think, darling?’

‘It’s the bloody battery, it’s—’

‘What? No. I mean—’

‘Oh, I see! Sorry, sorry.’ He stopped pressing and looked at her. ‘I think we’re going to do it. I think it’s going to work.’

‘So do I.’

He pressed again and the locks lifted with a satisfying click.

After a week and a half of using a nasal spray containing a drug to ‘shut down her system’ as they put it, Juliet started the course of injections which was to stimulate her ovaries and start her on the journey towards egg collection. She was offered the choice of going to her own GP for the injections, going to the clinic daily or even letting Michael administer them, but she had chosen to go to the clinic, loving the feeling of having something positive to do every day, and each time looking forward to the contact with the nurses who were always happy to answer questions patiently and discuss the thrilling subjects of pregnancy and birth over and over again for as long as she wished. She went every day at eight-thirty in the morning before going to work. She would chat to other women undergoing treatment, some of them into their third or fourth try, and sometimes she would feel panic at the thought that this might be her in a year or two’s time, growing ever older and more desperate, nearer every minute to the watershed of forty, and then reaching it and passing on to the downhill slope that would lead further and further from any hope of success. But on the whole it was comforting to be with others who understood and who had already been through the processes that still lay ahead of her.

Every day she was ushered into a small room subdivided by screens and she became quickly accustomed to watching the ritual of her treatment. The top of a glass ampoule would be broken off, the clear liquid it contained sucked up into a syringe, squirted back into a second ampoule of white powder which dissolved instantaneously, then sucked up again before a new needle was attached and plunged into her buttock where the magic liquid was slowly pushed into the waiting muscle. Then after a few minutes relaxing she would set off for the office, feeling better for being filled with a mysterious substance which would work silently inside her body, bringing the fantasy of the baby ever closer to reality.

As the days passed she began to feel quite bloated, and imagined huge sacs of eggs ever expanding inside her.

‘I’m like a chicken, Hattie. If only I could just lay one of the bloody things and let it hatch in one of those incubators.’

‘How do they know when you’ll be ready?’

‘When I’m ripe you mean?’ Only with Hattie could she joke so lightly about this most important of all possible events in her life. With Michael it was too fragile, too serious to discuss in any but the most hushed and reverential of tones, and it was a relief to be having lunch with her friend again in one of their familiar haunts in Kensington, smiling over the lasagne and chatting about eggs and babies as if it were no different from discussing the weather or the government; just much more interesting.

‘They scan me every few days to see how they’re doing. More jellied eyes. I’m getting quite used to it.’

‘And how’s Michael?’

‘Oh, he’s fine. He’s terribly worked up about it, of course. He thinks it doesn’t show, but I can feel his tension zinging about inside him. To tell you the truth it really irritates me sometimes.’ Juliet leant forward over the pink-clothed table. ‘I mean it’s not as if he’s got to do anything but just wait – I’m the one who feels like a battery hen. And who has things stuck up her all the time.’

‘Don’t knock it, darling.’ Harriet raised her eyebrows. ‘Some of us could do with a bit more of that, I can tell you.’

‘Oh no, you’re not pulling that one on me! It’s the most unpleasant experience and even you couldn’t possibly find anything remotely sexy in it at all. Much more fun to produce them the way you did. Michael and I haven’t had it for weeks now. It’s really weird – all those times we were so careful when we were going out together; we’d have given anything not to have had to worry about condoms and all that, and now that there’s no need, it – well, sex just doesn’t seem to have any point somehow.’