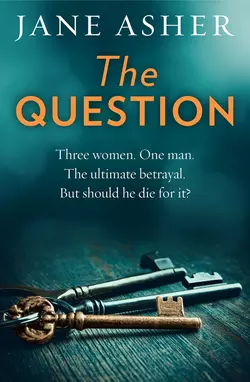

The Question: A bestselling psychological thriller full of shocking twists

Jane Asher

Following the great success of Jane Asher’s debut novel The Longing, her second psychological thriller is a compassionate, compelling and beautifully written study of the terrible effect of jealousy on a woman’s life.John and Eleanor Hamilton are middle-aged, wealthy, and settled in their comfortable life in Hampshire and London. John didn’t want children, so instead Eleanor used her energies to help run the company and get involved in the local community. So imagine her horror when, one day, she discovers that her husband has led a secret life for twenty years, in the shape of a mistress and a nineteen-year-old daughter – the daughter that she herself never had.The jealousy that Eleanor feels is all-consuming, driving her to limits she would never have thought possible. Then John, badly injured in a car crash, becomes a victim of PVS – Persistent Vegetative State. Although he is capable of communicating by the tiniest of signals, he has no quality of life.And so arises the ultimate question – and the ultimate opportunity for revenge. Should he live, or should he die? John’s fate hangs in the balance as the three women he deceived and betrayed decide upon the answer.

THE QUESTION

Jane Asher

Copyright (#ulink_22b28c06-b25e-551f-adae-37795829a23e)

Harper An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 1998

Copyright © Jane Asher 1998

Jane Asher asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2017 Cover photograph © Shutterstock.com (http://www.shutterstock.com)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007349623

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2012 ISBN: 9780007398140

Version 2017-12-18

Dedication (#ulink_ebfe10ad-b515-55dd-a75b-7699ed946490)

For Clare

Contents

Cover (#u7b1f6e49-023d-5ee8-8135-85712ab146cf)

Title Page (#u731e9e22-d18e-54b4-891f-b8efe1e9823d)

Copyright (#ue320cd00-fc0c-5f2c-b56a-dbb455b72bae)

Dedication (#u14e91d5a-ee72-5337-83dd-1ba60a53f002)

Chapter One (#ud7028380-fbc3-52aa-afa4-ae26906aa1f1)

Chapter Two (#u8e156a22-c543-56e8-8108-c815bc05bdb0)

Chapter Three (#uc95412ac-24e4-54f0-b02e-b96e1c4bc9c1)

Chapter Four (#ud950d711-7d84-5e60-a053-64164feed57f)

Chapter Five (#u084fe245-b4a8-5feb-b195-ffe5d2eace42)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_13c46ca0-d893-542e-81f6-454844544a4b)

‘So how was your holiday?’

‘Wonderful, thank you, Mrs Hamilton. Absolutely wonderful. You can never be quite sure about the weather out there, but we were really lucky – it was gorgeous. Jackie got really burnt and I was covered in freckles, as usual, but we really enjoyed ourselves.’

Eleanor grimaced a little to herself as she continued listening to Ruth’s chatter, the girl’s tone and the liberal sprinkling of ‘reallys’ as grating to her ear as ever. She smoothed a hand across her upper lip to wipe away the tension she could feel settling into the muscles around her mouth, then hunched up her shoulder and gripped the receiver against it with her chin. She reached out to pull the kettle closer towards her along the hardtop, tilting her head to examine more clearly the distorted reflection in its rounded chrome surface, feeling the usual jolt of unpleasant surprise at seeing the clarity and depth of the lines running from nose to mouth.

‘Lucky you!’ she volunteered, the flat calmness of her voice giving no indication of the intense scrutiny she was giving herself as she peered even closer at the image in front of her.

‘Oh yes, we were. Really lucky. Getting that late booking was a real stroke of luck, and Mr Hamilton letting me go a week early like that too. We only got back on Friday evening and it still seems a bit like a dream.’

Eleanor stretched her mouth downwards and raised her eyebrows, pulling the soft skin of her face into an elongated, surprised O and the eyes into inquisitive rounds that challenged her in the reflection. The lines lengthened and thinned but remained stubbornly in place. She forced her lips into a grin – wide, huge and humourless – and gripped the receiver again with her hand as she turned her head from side to side to check the profiles. Now that the lines were buried in the flesh of her cheeks they were more acceptable, the forced smile giving them an excuse to be there. She relaxed a little, even allowing a little genuine warmth to creep into the still maintained rictus of her lips. Her hair was looking good, she decided. The new girl had cut just enough to add some bounce and style without giving her that shorn look she hated. And the colour was perfect – exactly the right amount of Russet Brown to warm it up and soften the grey without looking overcoloured and hard around the tidemark, as John always called it. Suddenly she pictured Ruth’s thick, dark red hair spilling and curling, as she knew it must be, over the receiver as she talked on, and felt an uncomfortable little stab of envy pinch deep inside. The grin dropped a little and she sighed.

‘Anyway, Ruth,’ she interrupted, ‘I wanted to show Martin Havers some new swatches I picked up the other day. Lovely colours. And not unreasonable.’

‘For the—’

‘For the show house. Manchester one.’

‘Oh right, yes. Do you want to come in, or shall I—’

‘No, I’ll come in. It’s curtains I’m talking about. You know.’

‘Yes, Mrs Hamilton, I’m with you now. Do you want to—’

‘I’ll come up to town tomorrow. Do you know if he’s particularly busy or will any time suit him?’

‘I’ll put you through to Mr Havers’ office in just a moment. Did you find a good yellow after all that? It was a yellow you were after wasn’t it?’

‘Yes, I did. How clever of you to remember. Gorgeous. A lovely yellow.’

As she spoke, Eleanor could see herself spreading the large sample of lemony cotton piqué across Martin Havers’ desk, acknowledging his appreciative reaction with a satisfied little nod of her head. She pictured folds of it gathered and ruched and blowing from open sunlit windows into the magnolia-washed rooms of the new house. She was happy planning the schemes for the company’s more upmarket developments; the chance to spend a little more on fabrics and paint finishes made her feel less uneasy about the cheaper end of her work on the lower cost estates, where budgets were so tight as to give her no option but to plump for inferior, crudely patterned man-made furnishings that she knew she would never be able to live with herself.

‘Mr Havers’ line is engaged at the moment, Mrs Hamilton, but I’ll keep trying. Did you want a word with Mr Hamilton? He’s around somewhere but he seems to have slipped away from his desk. He has a ten o’clock meeting booked so he’s bound to be back in a second.’

‘No, don’t worry, I don’t need to speak to him; it was only to fix a time to come in and see Martin. I’ll ring back later on – or he can ring me. There’s no mad rush. Yellow curtains can wait till I’ve walked George.’

‘Talking of yellow – I love Mr H.’s new tie. All those swirly things on it – very unlike his usual.’

‘Well, I’m obviously in my yellow phase at the moment. I think it perks him up; very jolly. Certainly better than the usual old dark red. Anyway, Ruth, I’ll see you next time I come up. I’m so glad you had such a good holiday – and just ask Martin to give me a ring later.’

‘Yes, of course, Mrs Hamilton. Nice to talk to you. ’Bye.’

As Eleanor walked out of the large, tastefully decorated drawing room into her large, tastefully decorated hall she brushed a hand gently through the front of her hair, then patted the soft curls at her neck. Going up the stairs she automatically straightened her back and pulled in her stomach, vainly trying to flatten the persistent bulge that swelled from below the waistband of her camel skirt to the creases at the tops of her thighs. She paused at the window on the half-landing one flight up and squinted at the faintly reflected outline that she could just make out against the dark background of the shadowed lawns beyond. She sighed a little, pulled the muscles even tighter and moved briskly up the next flight and towards the bedroom, vaguely wondering, as she so often did, why she bothered to worry about her face and figure. John, she knew, loved her just the way she was. Indeed, he never stopped reminding her of it. He was aware and appreciative of the way she dressed; of the trouble she always took over her hair and makeup; of her neat nails and polished shoes (well groomed, as her father had described it), but the relentless signs of ageing that Eleanor acknowledged were creeping into every aspect of her body had never affected his feelings for her and seemed to have no bearing on the inevitable ebbs and flows of the physical side of the marriage. Their sexual relationship came and went in slowly moving cycles of which she was only indistinctly and intermittently aware. On odd occasions she would find herself lying in bed mulling over the evolving shapes and patterns of her marriage, like some infinite, dreamlike version of the earth’s surface – giant plates imperceptibly shifting over millennia to meet in slow motion crashes for a few centuries, before gliding away from each other again into frigid separation. There were periods when she would realise, without surprise or even regret, that they hadn’t made love for several weeks – even months. Certainly there had not, at least since the early days of their relationship over thirty years ago, been times when it had been more frequent than weekly, and, for her part, their supposedly joint decision to have no children had given their sex life an aspect of pointlessness that added to her lack of enthusiasm. Sometimes, during her night-time musings, she would admit to herself that John had talked her into the policy of childlessness; that she herself would have welcomed the ‘disruption’ and ‘diversion’ from their ‘comfortable life’ that he was so adamant had to be avoided, and at times she hated herself for having acquiesced so easily. In the main, however, she convinced herself that she had fully accepted the idea, and felt no lack at either the absence of offspring or the irregularity and unadventurousness of their love-making. The comforting friendliness and companionship of the partnership was enough, and she had long ago understood that John’s libido had gently dwindled, as hers had, to the stage where the occasional routine coupling was all that was needed to keep both parties satisfied.

She walked into the salmon quietness of the large bedroom and made to cross to her dressing table, but stopped suddenly in the middle of the room, her gaze fixed on the window in front of her, but seeing nothing.

At first she couldn’t think why she knew so certainly that her life had changed for ever. She stood suspended in mid-step, frozen into immobility by the shock of the knowledge that as yet had no substance or reason. Her mind wildly flashed back over the past few seconds, seeing in disjointed, back-to-front snatches the moments leading up to the present one. She saw herself entering the room; then her steps into the doorway; then the walk across the carpet of the landing; then her feet taking the last few treads up the stairs – no, her mind had been calm then; she could sense from this distance her normality on the stairs. It had been somewhere between the top of the stairs and—

Eleanor walked quickly out of the bedroom and back onto the landing, hoping she had been wrong; silently screaming at whatever force was controlling this pivotal moment in her destiny to transform what she knew she was about to see lying on the couch in the dressing-room next door.

She had no realistic hope of changing the fact that the yellow snake would still be there, coiled, waiting, on the velvet surface, just as it had been when she saw it those few moments before, but she forced herself to believe that she just might be able to make it change into something less portentous; differently patterned; differently coloured: less deadly. From where she now stood she could see only one blue arm of the couch: the seat and the other end being hidden by the frame of the open dressing-room door. She leant her body the last few inches sideways needed to clear her view, tilting her head to peer reluctantly at what she didn’t want to see. As she moved, the unfocused white gloss moulding in the foreground of her vision slipped away to the side like a curtain pulled back from a sickening tableau.

It still lay there, just as she knew it must; the dark blue pattern along its length pulsing against the bright yellow background. As she stared at it, mesmerised by its unassuming yet deadly presence, she could feel the poison already seeping into her soul. She marvelled at the intricacies of her subconscious; only now in retrospect beginning to work out consciously what she had known instinctively in that first millisecond of awareness when she had passed the open door of the room that lifetime of a few short moments ago.

She stayed unmoving, fascinated, trawling through the evidence logically and calmly, still, in spite of the reptilian silk in front of her, harbouring a tiny seed of hope that something had been missed, that the inevitable conclusion could be changed or avoided. But the facts that forced themselves on her attention chafed at her relentlessly, like some horrific piece of logic leading inexorably to one answer:

I bought the new tie only last week.

The tie is lying here in front of me.

Ruth has been away on holiday for two weeks.

Ruth only arrived back on Friday evening.

Therefore, class,

John is not wearing the tie today.

Ruth hasn’t seen John for two weeks until this morning.

Therefore, again,

Ruth hasn’t seen John’s new tie.

But she has just told me she likes his new yellow tie.

Conclusion:

Someone is lying.

Discuss.

Eleanor’s immediate instinct was to rush back to the phone and get through to Ruth again; to demand an explanation and to scream her panic down the line. Then she thought better of it: that was too easy. Over the phone Ruth could bluff her way out of it; she wasn’t stupid. A physical confrontation was needed – a trip up to town and a storm into the office as in a scene from a film – the avenging wife crashing through into the heartland of her husband’s empire, denouncing, shaming. But picturing the faces of receptionists, secretaries, junior managers, turned towards her incredulously, young eyes agape, lips parted in expectation and enjoyment of the wonderfully embarrassing scene unfolding in front of them, made her quiver in disgust and humiliation. She forced herself to be still and breathe quietly for a few moments before slowly moving across the landing and towards the stairs.

Back in the kitchen she walked over to the kettle and plugged it in, only half aware now of the reflection of the whitened face that stared back at her. There could, of course, be a perfectly rational explanation for this, she told herself. She was getting it all entirely out of proportion. But then why did her whole body tell her something was so dreadfully wrong? Going over it again she tried to work out just what it was that was making her feel so threatened. If Ruth had been away till Friday night then there was no possibility of her having seen the new tie, that was incontrovertible. But perhaps there was another tie? She must have meant a different one. Was there another tie she could possibly have seen that might just have fitted the description of swirly things on yellow? That she could describe as ‘new’?

As the water in the kettle began to mutter and growl around the heat of the element, Eleanor struggled to remember what tie she had seen John wearing as he had left in the morning. She could see him coming out of the bathroom, his thick grey hair still wet, brushed neatly back as always. In her mind’s eye she watched him walk out of the bedroom, his tall figure slightly stooped in the white towelling dressing gown. They had been chatting about the week ahead of them, as they always did on a Monday morning, shouting to each other from bedroom to dressing room, Eleanor sitting at the dressing table carefully sponging beige foundation onto her moisturised face.

‘So I’ll stay up till Thursday, darling,’ John had called out to her, ‘probably. It depends how it goes. I might leave it till Friday, but I’ll see. Abbotts are nearing finishing the plans on Devon and I want to work through them before they’re finalised. And year-end reports are getting horribly close. Have we anything on?’

‘Not really, although I told Amanda we might drop in on them for a drink at some point, but the weekend’ll be fine. Is Devon going to have more ghastly whirly ceilings?’

There was a silence. Eleanor knew John found it particularly irritating when she criticised the inferior plaster finishes on the housing estates, but there was something about the depressing combed half-circles of thick white plaster applied quickly and cheaply to their ceilings that she found objectionable and dishonest and she could never resist saying so. To her eye, combined with the sprayed-on roughcast exteriors, the ceilings gave the houses the impression of shoddy goods covered quickly with an unattractive veneer of mock sophistication.

‘John?’

‘Yes. Probably. Well, of course, yes.’

She could hear the annoyance in his voice but went on, enjoying the predictability of the marital friction that she knew she was inflaming, puffing powder over her face as she talked. ‘I’d just love to see you live in a house like that, that’s all.’

John didn’t bother to reply, but continued dressing next door in silence. Eleanor could hear the slight squeak of hinges as he opened the old mahogany wardrobe, and the faint clink of metal as the hooks of the clothes hangers were pushed together as he sifted through his jackets.

The hinges squeaked again as the wardrobe was closed. Eleanor brushed brown shadow across her eyelid as she half listened to the rustle of cellophane as John took a shirt from its laundry wrappings, and then to the whip of cloth as he briskly shook it free of its folds. She was waiting for the moment when he would come back into the bedroom to proffer first one, then the other arm for her to do up his cuff links. Until she saw his face she felt unable to judge his mood, and unsure as to whether it was worth pursuing the ceiling conversation or whether the annoyance factor was too great to be overcome. Not that she felt particularly strongly about the poorly finished ceilings, but it had become an interesting and long-running challenge to get John to admit that he thought them as ugly and vulgar as she did. The unspoken words that were passed via the briefest of looks on both sides during such discussions were as revealing as those that were actually uttered. A quick glance from beneath John’s raised eyebrow silently asked Eleanor why she couldn’t appreciate that everything that she now enjoyed in the way of lifestyle was paid for by the very ceilings that she so abhorred. Eleanor’s returning smirk conveyed that she was, indeed, only too aware of just what it was that paid the bills but didn’t he realise that there existed men who could provide for their women to a standard as high – or higher – than he did without having to compromise on moral or aesthetic standards? The toing and froing of question, answer, recrimination and impatience would often continue for some time, the silent conversation bouncing between them like some invisible ball.

The click of the kettle’s switch as it came to the boil snapped Eleanor back into the present as she still struggled to picture John as he had walked back into the bedroom. However hard she tried to remember, the tie he had been wearing refused to materialise, but it was quite clear to her that he must have worn one of the relatively limited choice of safe, striped ones that he tended to revert to unless pushed by her into something else. His natural instinct was to quiet conformity, and she would certainly have noticed if he had worn anything even remotely similar to the brightly patterned yellow of the one still pulsing its terrifying implications from the couch upstairs.

She made the tea automatically, hardly glancing at the plastic jar of tea bags, the carton of milk or the bowl of sugar as her hands found what they needed by feel, programmed by years of having made these same movements in the same way day after day to be able to judge precisely and unconsciously the distance from kettle to cup, spoon to bowl and carton back to fridge. While her body moved calmly and routinely, her mind was flying, darting back and forth over days, looks, months, expressions, smiles, phrases, excuses, years, laughs, absences – anything that might now be possibly construed as a clue. Some memories and images came back relentlessly over and over again: the times she had rung the flat and had no answer; the smile he gave her every time he drove off to London; messages from the office to say he couldn’t get back to the country as expected; his voice blowing a kiss down the phone at the end of his regular evening call. The pictures in her head were crescendoing to a visual scream of unbearable misery that battered on her mind’s eye from within. She picked up the mug and took a gulp of scalding tea that burnt her mouth and shocked her into a moment’s respite from the mental cacophony.

But, like a red ant crawling over a stretched white sheet, a single, relentless image crept into the stillness and clarity of her emptied mind. Hair. Red hair. Long red hair curling over a receiver.

Ruth’s hair.

Chapter Two (#ulink_8ea35a08-57f6-5920-9c69-a27ba18234c5)

That Monday morning George didn’t get his walk after all. Eleanor shut the puzzled black Labrador in the kitchen, grabbed her bag from the hall table, locked the front door and drove the Range Rover down the A3 towards London. She had no idea what she would do when she got there, realising after just a few miles that the potentially perfect excuse of the yellow curtain material was lying neatly folded on her desk in the study.

‘Idiot!’ she shouted out loud at herself, then, ‘Idiot!’ again at the very thought that she should need an excuse at all; she, the wronged woman, as she was now convinced she was: the innocent.

‘He’s the one who needs the excuse. Bastard!’

She turned on the radio and listened for a few seconds to the Classic FM jingle played on a harp, wondering, in spite of herself, how many versions of the miniature theme existed, and whether the composer could possibly receive royalties every time it was played.

‘No, of course not. They must have done a sort of allin deal.’

She smiled to herself at her own absurdity, then suddenly frowned and, feeling an uncomfortable tightness in her throat and a fullness behind her eyes, knew she was in danger of starting to cry. She slowed the car down and looked for somewhere to stop.

In the lay-by she switched off the engine and looked out of the window at the cows in the field next to her, their tails flicking away the flies as they grazed, moving slowly across the ground as they tugged at the grass, lifting their heads occasionally to stare around them as their mouths worked at it, jaws sliding sideways in continuous motion. Eleanor felt a deep sadness as she watched them. Had she failed John? What was it he had needed from her that she hadn’t been able to give; that the red-haired Ruth had supplied instead?

‘Sex, I suppose,’ she muttered out loud. ‘Middle-age crisis; male menopause, or whatever they call it. But what do I have to go on? Why do I feel so sure something’s wrong? What do I really know? And I must stop talking to myself – I’ve got to think.’

She stopped and felt herself calm a little. She didn’t like the way her usual ordered, logical intelligence had deserted her, and began to think through the evidence that had prompted the horrible certainty of John’s unfaithfulness. She tried to remember a previous occasion when she had felt like this, but couldn’t. The feeling was utterly alien. In all the years of marriage, through periods of intense irritation with each other, through the times of boredom, of friendship, of comfortable familiarity, she had never once had the slightest suspicion that he might be having an affair. It seemed to her all at once pathetic that she hadn’t. With newspapers packed every day with stories of desertion, divorce and infidelity she couldn’t think now how she had ever felt secure. Even the bastions of her upbringing had deserted her over the past decade: the sleazy goings-on of Tory MPs had become regular reading in the once safely staid pages of her Daily Telegraph.

A string of attractive, available secretaries and PAs from John’s years at the office paraded in front of her mind’s eye. She saw them all in bed with him – first individually, then in a romping, orgiastic group.

The vision filled her with a terrible, furious, nervous energy, and she hurled herself onto the steering wheel and turned the key violently in the lock, holding it pushed as far forward as it would go while the starter motor churned loudly and impatiently. A smell of hot oil reminded her to relax her grip, and the key sprang back in the ignition and the engine purred into life. She released the handbrake and pulled out of the lay-by, hardly glancing in the wing mirror as she did so.

By the time she pulled into a meter bay opposite the office in Portland Place she was calmer. As she reached for the door handle she paused and glanced at her watch, then sat back into the seat again. Why see Ruth before she had to? The idea of a meeting with her was agony: both the possibilities of confronting her with what she knew – or thought she knew – or of avoiding the issue and behaving as normal seemed utterly impossible. In another five minutes or so Ruth would leave the office for lunch as she always did, and Eleanor could talk to John on his own. Quite what she would say, she hadn’t begun to consider. She just knew she had to look at him; to search the face of the man she had thought she’d known for so many years and who now felt like a stranger. This man who was ‘carrying on’ with his beautiful red-haired secretary was a figure from a novel or television programme; not the familiar, boring, comforting, predictable husband of thirty years.

She watched as, a few minutes later, Ruth’s tall, slim figure stepped through the black-painted double doors of the large house and moved down the pillared stone steps. A lightweight beige raincoat was pulled in tightly round her waist, and as she glanced up at the sky, wrinkling her nose in disapproval at the small specks of rain, Eleanor was dismayed to take in the unlined, pale, but prettily freckled skin and clear, shadowless eyes, seeing the attractive face quite differently now that it belonged to a rival rather than a friend. Ruth turned in Eleanor’s direction to reach over one shoulder for her leather knapsack, and Eleanor made to sink down in her seat. Realising even as she did so that the Range Rover was as identifiable as she was herself, she sat up again and stared straight at the young girl, daring her to raise her eyes; ready to tackle whatever greeting might be given, prepared to rage inwardly at the attitude of friendly innocence she felt sure would be assumed. But Ruth pulled a tiny telescoped umbrella out of the bag and, without glancing towards the car, began to unfurl and extend it as she turned away again and walked northwards along the wet pavement. Once she was out of sight, Eleanor stepped from the car and crossed the road, ignoring the sprinkling of fine rain that marked her coat and spotted her shoes.

‘Darling – I’ll be with you in a minute. Ruth’s at lunch, but I’ll get Judith to fetch you a cup of tea – or do you want coffee?’

Eleanor couldn’t rescue herself from the lurch of shock she felt in the pit of her stomach at hearing Ruth’s name in John’s mouth in time to answer before his head had disappeared again from around the door of the office. She had looked up just in time to catch the briefest glimpse of a dark red, striped tie at his neck, and it was all she could do to stop herself leaping up from her chair and following him. She tried to pull herself together enough to call for coffee in as normal a voice as she could muster, but he was shouting to her from the corridor before she could manage more than an intake of breath.

‘Do you want to see Martin? Ruth said you were bringing something to show him.’

It was hopeless. The second mention of her name had hit her in the stomach again, and she felt once more the dangerous threat of tears and decided to keep her mouth shut. She knew John wouldn’t wait for a reply – much of the time his questions were thrown out rhetorically in any case, and she was well used to being ignored when replying to them, particularly in the context of the office. If she didn’t answer, he would just stride on in whichever direction he had been going before he had diverted from his route long enough to cast a quick greeting at her where she sat in the luxurious outer office. She had tried to search his face in the couple of seconds it had been in front of her; anxious to catch traces of the new person she was now dealing with. It was disconcerting to find him looking the same as ever, and again she felt a flash of panic and guilt at the assumption she had made and at the guilty verdict that she had so quickly imposed on him on a single piece of evidence.

She took a well-worn gilt compact out of her handbag and began to powder her nose and cheeks, trying hard to ignore the contrast that the picture of her face in the tiny mirror made with the image of the upturned face of the young girl squinting into the rain that she had seen a few minutes before.

‘Thank you, Judith.’

The tea was put down on the coffee table in front of her. She looked up, suddenly anxious that something in the tone of her voice had given her away; half expecting to see curiosity or sympathy on Judith’s face, but meeting only her usual expression of bland indifference.

‘Mr Hamilton says he won’t be long. Anything else I can get you, Mrs Hamilton? Did you want to see Mr Havers?’

‘No, for goodness’ sake, why does everyone think I want to see Martin? And I did ask for coffee, Judith.’

‘Sorry, Mrs Hamilton, I thought Mr Hamilton said tea. And I thought Ruth said you were coming in to see Mr Havers.’

Eleanor knew that Judith was right and that the slight tone of resentment in her voice was completely justified, but that didn’t prevent it from annoying her. How dare she come back at her like that? What gave her the right to—

‘Did you want me to change it for coffee?’

‘No, no, leave it now. Leave it. Tea’s fine.’

She looked at Judith’s large, tightly skirted bottom and hips as she walked away from her and felt a wash of sweaty dread break over her. Could she be another one? Now she no longer knew John, he could be capable of anything. But he hated fat women; he had always said so. But even as she thought it she knew that ‘always’ had no meaning now: the man who had ‘always’ didn’t exist.

She looked around the office at the large modern watercolours, cream sofas and glass coffee table and tried to identify something else that was badgering for her attention at the back of her mind. It took a few seconds to identify it: she was hungry. Her usual routine of toast and marmalade first thing, followed by morning coffee and biscuits an hour or so later to the accompaniment of Woman’s Hour, had been abandoned in the morning’s upheaval, and it was only now that she realised she had eaten nothing since a small supper over fifteen hours before.

Eleanor was solidly built; shaped in a way that had changed little since spreading into a traditionally English pear-shaped middle age in her mid-forties. Her intake of food had varied little over the years: although she sensed that the energy she expended was a little less every month that passed, she did nothing to adjust the amount of fuel that sustained it, secretly a little mocking of those of her friends who had joined in the general drift towards diet and exercise. Gyms and aerobic classes were for those younger than she, and were even to be looked down on for encouraging an unhealthy awareness of one’s own physical condition. Missing a meal was not something to be taken lightly, and even in her present emotional state, the demands of routine were pressing and unavoidable.

She considered calling Judith again and asking her to send out for a sandwich, or to bring her a plate of biscuits from the office kitchen, but suddenly seeing again in her mind’s eye the meeting with John that was inevitable if she stayed, she decided to use her hunger as an excuse to herself to go, and quickly picked up her coat and bag and left.

She turned the car round and drove down one of the side roads towards Marylebone High Street, thoughts of the quiches and rolls she knew would be in the window of her favourite coffee shop juggling for position with an image of Ruth’s slim frame balanced on one hip on a corner of her desk as she nibbled at a crispbread or sipped at some mineral water.

‘Coffee and a Danish pastry, please.’

‘Cappuccino, espresso or filter?’

It had taken an enormous effort on Eleanor’s part to bring her voice into a semblance of normality long enough for her to give the order, and the strain made her dizzy. To have it countered with a question fired back at her so quickly took her by surprise.

As the young waitress gazed down at her, Eleanor opened her mouth to try to answer but suddenly stopped; hit by a terrible uncertainty. The choice of coffee seemed suddenly impossible. How could she make a decision if she didn’t know who she was? She found herself stuttering and panic-stricken: unable to reply or even look the girl in the eye. The waitress’s obvious embarrassment just made it worse, and it was a relief when she muttered something about coming back in a moment and, putting a menu down onto the polished wood surface of the table, moved away towards another customer.

Eleanor took stock. It was so extraordinary for her to be out of control like this. It was new, and it frightened her. Yes she suspected her husband of having an affair, but surely she could deal with this as logically and calmly as she always had with problems? Why did she feel so completely incapable? Even her physical surroundings seemed to be all at once abandoning the rules: the marble floor tilted away from her into the shadows; the walls looked warped and soft; the table sloped and buckled. She rested her forehead on the palm of her hand for a moment and closed her eyes. In the relative calm of the pink world of her inner eyelids she could see more clearly, and suddenly understood. Not only was John not the man she thought she had known: she herself wasn’t the same woman, either. Her position in an ordered, comfortable, middle-class world was turned upside down, and by living with a man who had been lying to her for – how long? – she had unwittingly colluded in a nonsensical pretence. For so long she had read in magazines of women resenting their position as ‘somebody’s wife’ and had always thought their worries childish and irrelevant: now she could see – could feel – what they meant. If she wasn’t the happily married woman she had thought she was for so long she seemed to be nothing.

By the time the waitress returned she was able to order, and after downing the cappuccino and chicken sandwich that arrived within minutes, she felt fortified and more resolved. Sensing suddenly what she must do, she paid the bill and went back to the car, smiling slightly in her newfound sense of purpose and direction.

She swivelled the driver’s mirror down towards her until she could see herself clearly and reached into her bag for a comb, pulling through the dampened but still glossy-looking brown curls until they were arranged to her satisfaction, pleasantly surprised to see that her makeup had survived the ravages of emotional upheaval and that, once a quick swipe of lipstick had been applied to her mouth, she was in reasonable shape to tackle the next stage of this extraordinary day. As she moved the car smoothly out of the meter bay and made her way towards the flat in Nottingham Place she felt almost excited. The sense of terrible anticipation that she had had since the morning’s discovery had taken on an aspect of nervous energy that was almost sexual in its physical attack on her. A sensation that was somewhere between a desperate need to urinate and a thrill of excitement fluttered between her legs, and she squeezed her thighs together as she drove to try and contain it.

The only meter she could find was in Paddington Street, but as the rain had stopped the five-minute walk to the flat didn’t seem too daunting, and the thought of the fresh air was good. She would install herself comfortably in the sitting room and await John’s return in the evening; by the time he arrived she would have planned her assault on him carefully enough to prevent his wriggling out of it; she would be ready to counter any excuse he might have with a crystal-clear, logical comeback. Her step was purposeful and almost confident. A clarity and overwhelming need to know everything had taken over from the blind panic.

Eleanor walked with her upper body thrust forward from the hips as if her head were more eager to reach its destination than her feet, but the look of assurance it gave her on this occasion belied her inner struggles: to the onlooker the tall, middle-aged woman in sturdy shoes and Burberry raincoat striding quickly along the shiny London pavements appeared to have not a care in the world.

But that stride was to be stopped in its tracks by something so startling and yet so obvious that, even as she stood transfixed in horror, she wondered at herself for not having foreseen it. From where she watched, twenty yards or so away on the other side of the road, she was able to see quite clearly the attractive, neatly belted girl with red hair, carrying a bulging supermarket bag in one hand, approach the large dark red brick block of flats and turn into the entrance. How stupid she was! Where else did she think they would have met, for goodness’ sake? What had she imagined – a quick fling on the sofa in the office? A willing body pressed back onto the desktop, skirt pushed up; knickers pulled down? Secret kisses stolen by the photocopier?

Eleanor could feel the calm clarity of the last few minutes evaporating even as her mind scrolled relentlessly through the horrifying images; images that, intolerable as they were, she knew now were less terrible than the reality must have been. As she saw Ruth’s figure receding into the gloom of the flat’s main entranceway they were superseded by images more tranquil, more domestic and far, far more hurtful. Ruth cooking an amusing little Italian meal in the tiny kitchen of John’s pied-à-terre; John creeping up behind her, sliding his arms round her waist and kissing the nape of her neck in a clichéd movie version of cosy domesticity. Eleanor stirred herself and made to cross the road before she had to let them move into the bedroom and onto the white-framed Heal’s bed she had chosen with such care. Some things were not to be looked at – at least not for now. Anger drove her in through the front door of the flat and towards the confrontation she now felt was inevitable – and even to be welcomed.

The darkness of the inner hallway was comforting; she was less exposed in here, and more able to let her face reveal the anguish and fury which fought for expression in the set of her mouth and the tension in the muscles round her eyes. She stood still a moment to listen, tilting her head upwards towards the stairwell, expecting to hear the hum of the lift’s motor making its way up to the third floor with its hated cargo. But there was nothing; just the distant sound of a television set. She frowned, puzzling over the speed at which Ruth had apparently managed to get into the lift and up to the flat in the short space of time that it had taken Eleanor to follow her in, then tutted to herself at her stupidity.

Of course, she thought, she’s gone up the stairs. Just because I always take the lift it doesn’t mean she does. She’s young and fit – even if she was carrying that shopping. No doubt she does aerobics, or step or whatever it is now. Gym. She goes to the gym. In a leotard and tight shiny Lycra leggings. She puts her hair up in one of those scrunchy things and her face goes shiny and red with the effort of toning herself. Honing herself. Honing and toning. John likes her honed. He likes to see the gleam of sweat on her neck, the tiny droplet of moisture running down from the damp hair. He puts his mouth to the—

‘Oh shut up, you silly woman!’ Eleanor snapped at herself out loud and made her way towards the lift.

She stepped out at the third floor and turned to shut the old-fashioned metal lift gates quietly, not wanting to alert her prey to the avenging eagle in camel skirt about to descend on her. As she pulled the outer gate across, she suddenly panicked, all at once completely unsure of what she would say, what she would do, when directly facing the horror of looking Ruth in the eye. She could see how the girl would greet her: an immediate smile of recognition and pleasure at the sight of her boss’s wife, a flicker of guilty knowledge at the realisation that she shouldn’t have been found here in his flat, at the possibility that this woman in front of her knew that the husband was not only a boss but a lover, then a quick and smoothly accomplished murmur of excuse and explanation.

Eleanor took the door key from her pocket and crossed the worn maroon-carpeted landing towards the front door of the flat. She held the key out in front of her, waving it about slightly as if pushing aside the irresolute thoughts threatening to stop her momentum, like a blind man feeling with his white stick for objects in his path. As she made to push it into the lock, she stopped again and listened. Still nothing but the distant sound of audience laughter from the television. She almost believed she could hear her heart beating, but knew it was the sensation of it throbbing against her chest that she was aware of, and that the two senses of feeling and hearing had become confused. As she turned the key in the lock, surprised to find her hand far steadier than her thoughts, she shut her eyes tightly against what was about to be revealed by the opening of the door.

Chapter Three (#ulink_e63927e1-95d1-506d-9065-650574f5642c)

Eleanor took a deep breath and pushed open the door. The bottom edge of it brushed over the cream carpet with a faint swishing sound as it swung away from her, and she opened her eyes and looked into the darkness of the flat’s unlit hallway. She frowned a little, surprised into a mixture of relief and disappointment to find no lights on and to hear no signs of life coming from the kitchen at the other end of the passage.

‘Hello?’ she called out bravely into the silence.

Nothing.

She stepped into the hallway and closed the flat door behind her, feeling rather as she thought a lion tamer must when shutting himself into a cage with one of his animals, uncomfortably aware of the possible presence of her rival in one of the rooms in front of her. She coughed loudly as she walked along the length of the hall, unsure now whether she wanted to see the dreaded glimpse of red hair or not as she looked quickly into first the lavatory, then the bathroom, kitchen and sitting room.

She moved towards the bedroom and was annoyed to feel her heart begin its dramatic thumping against her ribs again. As she breathed in deeply but quietly in an attempt to calm it, or at least to give it more space in the uncomfortable tightness of her chest, she sensed for what seemed like the hundredth time that day the terrible urge to cry. She couldn’t remember ever feeling as alone as she did at this moment. To be creeping towards her own bedroom – or at least the bedroom she occasionally shared with John on her rare visits to London – in dread at the thought of finding the beautiful young girl she had convinced herself must be inside, was so miserably humiliating that she longed to turn to someone and appeal for the sympathy she knew she deserved for being placed in such an impossible situation. She even found herself crying out from some dim place in her soul for her mother to comfort her, a person and presence she hadn’t thought of with any particular warmth for many years.

By the time she entered the bedroom, registered it as empty and collapsed in frustration and fury onto the bed, the storm had broken, and she burst into the kind of relentless and exhausting tears that she hadn’t experienced since childhood.

But she didn’t let them last for long. If Ruth wasn’t here in the flat, where the hell was she? Had Eleanor fantasised that it was indeed the same girl that worked for her husband whom she had seen entering the building ten minutes ago? Could her overstimulated jealous imagination have created this doppelgänger of Ruth to taunt her and mislead her? Eleanor suddenly found herself feverishly examining yet again the early morning’s evidence that had begun the nightmare she had been living in ever since. Once more she trawled her memory for the tiniest hint of uncertainty or ambivalence. But even as she did so, she knew she was right. Some deeply rooted female instinct told her not to waste her time. There was an affair going on. And she had seen Ruth walk into this very block of flats. Ignoring the puzzling question as to where the girl could possibly have got to, pushing aside visions of her escaping from a bathroom window or hiding under the kitchen sink, she rose instead from the bed in a movement of intense but controlled energy and began to search the bedroom and bathroom for any evidence, however tiny, of an alien female’s occupation, certain that nothing could escape the concentrated scrutiny she gave to every corner, examining everything as intently and revealingly with every effort of her mind as with the needle-sharp beam of a finely focused torch.

After twenty minutes or so she gave up. She was certain that no other woman had occupied the room, or, if she had, she was so extraordinarily clever at covering her tracks that Eleanor knew she was no match for her. She carefully tidied everything back in place, splashed her face with cold water in the bathroom sink and made her way out of the flat and back towards the lift.

After waiting by the gates for a couple of minutes and hearing no sign of life she abandoned it and decided to walk, much less daunted by the thought of going down three floors than she would have been at having to climb the stairs coming up. The time it would take her to get back down to the ground floor stretched ahead of her rather comfortingly; the three or four minutes spent in the no man’s land of the stairwell would give her a further chance to recover and take stock. She was aware again of the sounds of the television she had heard earlier, and as she made her way down the stairs it became louder, reaching a climax on the first floor, where it clearly came from the open door of one of the flats. The sheer ordinariness of the varying notes and cadences of the human voice, interspersed with bursts of clapping or laughter, was deeply reassuring, and Eleanor glanced up at the door as she passed, catching a brief glimpse of a grey-haired woman in the doorway. She heard the door close quietly behind her as she went on down, muffling the noise of the television, and she reached the ground floor in a better state of equilibrium and calm.

The journey back to Surrey was uneventful. She still had no idea what she would do next, but managed to put away the car, open up the house, read the note left by the cleaning woman and attend to a frantically welcoming dog without feeling the need to know. She surprised herself by reaching for the telephone and dialling her brother in Gloucestershire, unsure what she would say to him but satisfying some deep-seated urge to make contact with someone.

Andrew picked up the phone in dread. For the last few years he’d always hated answering it, knowing he would find it difficult to hear what the person on the other end was saying and, even worse, knowing he might well be completely unable to identify them even if he could hear them. What appeared to be the entire collapse of his memory system, at least as far as names and faces went, caused him much embarrassment and annoyance, and at times like this, when Catherine was out of the house and he had no option but to pick up the receiver, he felt very hard done by.

‘Hello? Winstead 354?’

‘Andrew? Andrew, it’s me.’

Now that was familiar. He felt a huge sense of relief wash over him as he recognised the voice of his sister, and the fact it took him a split second to remember her name seemed amusing rather than serious.

‘Nellie. How are you?’

‘I’m fine. Well I – no, I’m fine.’

There was a small pause, and Andrew panicked slightly at the thought that something was expected of him. He went quickly over the conversation he’d had with Catherine that morning before she left. Was there any message he was supposed to do, have done, give to somebody? It wasn’t Nellie’s birthday or anything was it? It wasn’t his own birthday, surely? He smiled to himself. No, his internal address book and mug shot files might be completely out of sync but he did at least know that his birthday was a good few months away. But it was odd, Nellie ringing up like this out of the blue. The occasional call she made to them was more likely to be at a weekend than in the middle of a Monday afternoon.

‘Everything all right?’ he asked.

‘Yes, of course. How’s Catherine?’

‘She’s fine. She’s off shopping in the village. Stocking up after yesterday. We had one of our parish dos. She put on the most marvellous spread.’

‘Oh, right.’

There was another silence and Andrew shifted his weight off the more arthritic of his hips and cleared his throat. The small hall clock made the odd grating noise that it did before chiming, echoing in the polished quietness of the cottage hallway, and he turned to look at it.

‘She should be back soon,’ he went on. ‘She’s been gone about three-quarters of an hour. How’s John?’

Well, yes, thought Eleanor, of course he’s going to ask that. It’s only normal. The huge significance this simple question has for me is irrelevant to him.

She opened her mouth to give him some sort of noncommittal reply, then stopped, struck by the thought that if she were to answer with any sort of truth at all she would have to say she had absolutely no idea. How was John? Was he happy? Guilty? Miserably wretched and bored with his life of compromise; at having to come back to his worn old wife every weekend after the joys of Ruth’s firm young flesh? Or did he revel smugly in his cleverness at having deceived her, enjoying the rest and comfort of a well-ordered Surrey home after the rigours of his London life? She couldn’t stop a short grunt of disgust spilling out of her mouth at her own stupidity.

‘What?’

‘Nothing, Andrew. He’s fine, thanks. I thought I might pop down and see you both for a few days – are you a full house at the moment?’

Why did I say that? she thought. She had had no idea she was going to ask before it had slipped quickly out, but even as she waited for him to answer she found the thought of an escape route rather comforting.

‘No, no, just us. Yes, of course, Nellie, come any time you like. Just you, or could John manage a few days?’

‘No, just me. Not immediately, I don’t think, but maybe in a week or so. I’ll give you a ring. There are a few things I need to ask you.’

This last sentence filled Andrew with foreboding. Even as a practising vicar he had hated to be confronted by other people’s problems, much preferring the ceremonial and administrative side of his job to the shepherding and nurturing of the flock that was an inescapable part of it, and since retirement he had been even more uneasy at having to discuss anything of any personal depth. For a man who had spent all his working life representing or at least acting as an officer for the Church, his reluctance to discuss matters of the spirit or of emotional depth was a tiresome handicap, but one which he had managed to overcome by hiding behind the comforting rituals of the job. He had coped quite happily with his parishioners’ divorces, bereavements, illnesses and deaths by not only using the designated paragraphs from Prayer Book or Bible, but by trotting out the well-used formulaic words of comfort that he had copied from older and wiser colleagues during his training. But if anyone ever looked him in the eye and attempted a direct conversation with him about what he really believed in himself, or tried to tell him, really tell him, about their passion, agony or a dark night of the soul, he would dip his head in embarrassment and change the subject.

Now there was something in the way Eleanor had spoken that made him think that something very emotional indeed was about to come his way, and he curled his toes at the thought of having to face it.

After lunch the office always tended to quieten down a little, and John found a moment to pop over to see Ruth across the corridor.

‘Oh hello, Mr Hamilton,’ she smiled at him, ‘how was the lunch?’

‘Good, thank you, Ruth, very good. That’s all well on course and the client seems very happy. The last house should be finished next week. Thanks for all your help on that as usual – and the food was excellent, too. We should use that place again.’

‘Yes, right, I’ll make a note of it. Did you want me for some letters now?’

‘No, don’t worry, we’ll leave it for now. Come and do them about four, would you?’

‘Of course, Mr Hamilton.’

Just as John turned to leave he remembered what he had come to ask her.

‘Did you manage to get that spot of shopping done for me, Ruth?’

‘Yes, of course I did. It’s fine. Everything’s fine. Much better, in fact. Much better.’

She gave him a little encouraging smile and he nodded back at her.

‘Jolly good. Thanks again. See you at four.’

He walked back to his own office and shut the door behind him, feeling more settled than he had during the morning, now that things seemed to be getting sorted out. Ruth had become indispensable during the five years she had worked for him. She was pleasant-looking, too. What was it she was wearing today? He knew he wasn’t too good at women’s clothes, but he tried to picture her attractive body as he had seen it seated at the desk not a minute before. Pale blue. That was it, wasn’t it? A pale blue jumper of some sort; pleasingly tight. Her pretty red hair fastened up in one of those slide things. Very nice. He smiled a little to himself and shook his head. He gave a little sigh as he smoothed his straight greying hair back with both hands and then sat heavily into the leather swivel armchair behind the desk, hitching up both knees of his trousers automatically as he lowered himself into it, regretting the Stilton and biscuits he had unwisely indulged in after the chicken, but congratulating himself on having stuck to mineral water. He shook his head a little and smiled to himself as he thought, not for the first time, how lunches had changed since before he had become chairman. In those days they had taken place in the office dining room and lasted two or three hours; good, rich food – three courses minimum – always accompanied by plenty of claret, a Sauternes perhaps with the pudding, and port with the cigars. A certain sleepy fullness hung over everybody who had taken part for the rest of the afternoon – certainly there was not much work accomplished, or if it was it had always been a wise precaution to look over it carefully the next morning. On taking over on his father’s retirement, John had moved quickly to curtail such enjoyable excess, and, just as he saw his friends in the City doing, he cut his own and all the staff’s lunch breaks to a maximum of one hour when taken as part of the normal office routine, or an hour and a half when entertaining clients. The in-house catering had had to go: pleasant though it was to be cooked for by a regular small team who knew one’s every taste in food and drink, it was an extravagant indulgence that the company could do without.

The plans for the development of fifteen four- to six-bedroomed detached houses on the estate just outside Manchester were still spread out across the desk, and he pulled them over towards him, swivelling the large photostatted sheet round to face him. He was particularly proud of this project: the houses were going to look elegant and well-proportioned, with just enough garden round each one to give a feeling of privacy, in spite of his having insisted on squeezing in one more than the originally scheduled fourteen. He had listened to his architects’ arguments about angles of building height, diagonals of wall relative to ground span, proportion of garden size to number of rooms, but he was convinced the illusion of space given by the carefully planned hedges, arches and strategically placed walls would make up for the small amount of land he took from each plot. His speech to the planning officer had been masterful, even if he did say so himself.

It wouldn’t be long now before they finished the final plastering, and the interest from local estate agents had been extremely encouraging. He particularly wanted a quick turnround for these, and reached for the phone to check on the progress of the show house, and to remind himself of the date of its opening.

‘Ruth, get me Martin, would you? Did Mrs Hamilton show him the colour schemes this morning? I didn’t see her go – did she manage to get together with him, do you know?’

‘I don’t think she did, Mr Hamilton. I didn’t see her go either, I’m afraid. Do you want me to try and get hold of her?’

‘No, don’t worry. Just put me through to Martin, would you?’

He wondered idly why Eleanor had gone without saying goodbye – hadn’t she asked for a cup of tea or something? Usually she would bring her drink into his office and fill him in on her latest ideas for design, but maybe she’d had somewhere to go on to today. The large variety of charity work, church organising and general local do-gooding that she was involved in meant he was never quite sure what she was talking about when she discussed anything relevant to their life in Surrey. Perhaps she’d had something to go back to this afternoon – but then it was odd that she’d bothered to come up to town at all. She certainly wouldn’t have driven in just to meet Martin and show him her samples; there must have been something up in town for her to do. He knew it was no good his thinking back over their conversation this morning; she had said something about her plans, but as usual he hadn’t really been listening. During such conversations he generally managed to reply often and noncommittally enough to convince her that he was interested and aware, but all he could remember from this morning was a vaguely uncomfortable feeling that she had brought up the old whirly ceiling business again, and that he had half known she had unwittingly hit the nail on the head in that particular instance. The Devon houses weren’t going to be one of his better schemes: they would sell because there was a desperate shortage of houses in that area of this particular type and price bracket, but they were overpriced and ugly, and the sooner they were finished, sold and forgotten, the happier he would be.

He gave up waiting for Martin to come to the phone, and instead pressed the speed dial button on the telephone that was programmed for the Surrey number, ready to leave a warm and thoughtfully interested conjugal message on the machine to greet Eleanor when she returned, but was surprised to hear her voice answer in reality, rather than via the rather strained message that she had recorded on the answering tape.

‘Hello?’

John thought she sounded quieter than normal, almost hesitant. Eleanor’s middle-class tones usually had a quality of stridency about them that cut across the most crowded of rooms; this softly spoken one-worded question was almost inaudible.

‘Eleanor? It’s me. Are you OK? You haven’t got a migraine or anything, have you?’

‘No, why should I have a migraine? I thought you were Andrew ringing back.’

‘Because you came into the office and then just disappeared. I thought you must have an appointment in town, so I was surprised to find you answering the – Andrew? Andrew, brother Andrew? Why should he be ringing?’

‘Because I rang him.’

‘Oh I see.’

There was no doubt about it; there was something very peculiar in her tone. John couldn’t quite put his finger on it. After thirty years he prided himself on judging her moods and state of health very finely; knowing exactly when to leave her alone and when to indulge in the comforting husband scenario he knew he was so good at. But this one was a bit of a puzzle.

‘Why were you ringing Andrew?’

‘I just felt like it.’

‘You felt like it? You haven’t felt like ringing your brother for as long as I can remember. Had to, yes; felt you ought to, plenty of times, but not wanted to off your own bat. Not that I can think of. Is he all right?’

‘Yes, he’s fine.’

There was another pause, and John found himself getting irritated by this mysterious laconic exchange.

‘OK, I’ll leave you to it, then. Are you coming up tomorrow?’

Yes, thought Eleanor, no doubt I am. No doubt I am.

‘No, I’ll be here all day.’

‘Right. I’ll ring you this evening, anyway. ’Bye, darling.’

‘’Bye.’ The tiniest of pauses. ‘Darling.’

Chapter Four (#ulink_3ff4ce7f-191e-56f2-ac2e-d62d413875a0)

Eleanor went up to London for the next three days running. She managed to cancel or postpone most of her local meetings and social arrangements without causing too many problems, getting back to the country each day in time to fulfil at least some of the prearranged appointments. She surprised herself by being calmly efficient in her lying; smoothly explaining that John had had a change of schedule in one of his developments, and that her interior design work had been brought forward. She had no worries that her subterfuge would be found out – her life in Surrey was so separate from John’s in London that the two rarely intertwined at all. She was quite well aware that John understood almost nothing of the time she spent apart from him during the week; she knew even as she chatted to him on a Sunday evening or Monday morning of her plans for the week ahead that he neither understood nor cared about the people and places she was describing. It had never worried her; she had found it rather sweet the way he bothered to grunt or reply occasionally in roughly the right places so as to keep her happy, and the monologues – which in effect was what they were – were delivered as much to herself as to her bored husband. Now, however, she found herself thinking quite differently about his lack of interest in her life, although it was proving very useful when it came to her surreptitious excursions up to town.

She divided her time between watching the outside of the office and that of the flat, happy to sit calmly in the car for hours at a time; parking it carefully so that the likelihood of it being identified was kept to a minimum. She still occasionally thought she might be imagining that there was any problem at all, but as she churned over it, time and time again, she knew more definitely all the time that she was right. The possibility that Ruth had happened to be at the same block of flats as John’s purely by chance, coupled with the knowledge of the tie and the way she had clearly lied about not having seen him over her holiday added up to only one conclusion. Eleanor didn’t know quite what she was waiting for. She just knew that if she gave it long enough, something or somebody would reveal a further clue, give her a little more evidence, a little more knowledge. Two questions dominated her thoughts as she tried to penetrate the superficial smattering of facts and find the truth. She couldn’t leave it alone. It was like an itchy patch of skin she kept fiddling with and picking at; worrying at the inflamed place until it would break open to reveal the ugly sore underneath. How long had the affair been going on? And did John think he loved Ruth, or was it a short-lived sexual encounter that had already begun to fizzle out? Either way, Eleanor wasn’t at all sure how she would react when she finally made her move; if indeed she ever did make a move at all. She had considered more than once doing nothing, returning to Surrey and pretending nothing had changed, that she had never heard Ruth mention the yellow tie, and never seen her in Nottingham Place.

But she knew that wasn’t possible. Never again would she be able to look John in the eye, never again hear him tell her of his evenings in town or his nights in the flat without being aware of the possibility that he was lying.

On the Thursday she made sure she got back in good time to the country, unsure as to whether John might be returning that evening, and wanting to see that everything was looking as normal as possible for his homecoming, and that she herself was calmly ready to tackle the awkwardness of having to face him for what was in effect the first time since the weekend. Their Spanish cleaning woman, Carla, given the extra time allowed by three days completely alone in the house without the coming and going of Eleanor, had tidied and polished more than usual, and Eleanor spent some time rearranging things, opening up windows and scattering signs of life about to make the house feel more as if it had been inhabited as normal during the past three days.

She didn’t know whether to feel angry, relieved or disappointed when John’s call came at six o’clock. It wasn’t as if it were anything new, of course, and many times over the years she had been rather pleased to have another night on her own in front of the television when she had been expecting to cook for John and spend the evening with him. But this time she found herself listening wryly to his call and realising that she had no way of knowing now whether what he said to her contained a word of truth.

‘So I’ll stay up till tomorrow darling, and leave a little early in the afternoon. Are we still on for the drink with Amanda, or didn’t you fix it?’

‘No, I haven’t called her. Any problem today? Any particular reason why you’re not coming back tonight?’ Is Ruth feeling a bit randy? Hasn’t she had enough this week? Eleanor mentally interpreted the conversation on both sides as it continued.

‘No, not really. Just a bit more on than I thought, that’s all.’ It’s not her. It’s him. He wants to spend another night next to her: to play with her firm, high breasts, to kiss her unlined, smooth face.

‘Well, I’ll see you tomorrow then, about fourish as usual. Have a good evening.’ I hope she gives you a heart attack as she f—as you make love.

‘Yes, OK. Thanks, darling. Have a good evening yourself. I’ll see you tomorrow.’ He’s thanking God he’s got one more night away from me, you tired old bag.

As soon as she had put down the receiver, she knew she would go up to the flat again the next day. It felt like her last chance; once he had come back and spent all weekend at home she knew she would weaken into either saying something too soon and give him the chance to cover up the truth, or she would do nothing and let the suspicions fade away into a permanent, grumbling misery. The flat seemed like the best bet for a final throw: at the office they were used to his wife appearing with no notice; they would be too practised at their deceit. The flat she virtually never visited except when with John after an evening out together. If Ruth was seeing him there with any kind of regularity there was a good chance of her being caught.

No – of course! she suddenly thought. How could she have been so stupid? It wasn’t during the day that she would catch them – it was now, this evening, at night. He had rung with his excuse – bastard – and now knew his wife was safely at home as usual. Now was the time they’d be together, and now was the time she’d catch them.

She threw a jacket over her brown long-sleeved dress, picked up her bag and quickly locked up the house, catching the dog’s reproachful glance as she walked out through the kitchen.

‘Oh Christ, I haven’t fed you, have I, George? Never mind, I’ll do it when I get back. Be a good boy.’

She installed herself in her usual discreet parking place from where she could clearly see the front entrance to the flats, and waited. After ten minutes she began to feel impatient, and looked at her watch. Seven forty-five, she muttered quietly to herself. On a hardworking day he’ll stay at the office until seven thirty or eight, and reach the flat about eight fifteen. Give it another ten minutes or so.

But then a sudden quiver of something like frightened excitement ran down the inside of her belly as a thought struck her. Or does he? Has he been getting back to the flat far earlier than I’ve ever known? Has he been ringing me after he’s eaten, or made love, or lain in the bath with her, or whatever they like to do together when they first get there after work? Telling me he’s just got back, when they’ve been relaxing there for an hour or so with their drinks and their self-satisfied, smirking, knowing looks into each other’s eyes?

Anger ripped through her body and jolted her muscles into sudden, intense action. She almost leapt out of the car, slammed the door shut and ran over the road towards the building, not bothering, for the first time in her life, to lock the car, and intent on only one thing. To find them. Together. Now.

Too impatient to wait for the lift, she half ran, half walked up the stairs to the third floor, getting out of breath by the time she reached the second-floor landing, but refusing to let herself stop and rest until she had reached the flat and discovered what she felt sure was the lovers in their lair. She went straight for the door and inserted the key without hesitation, still fired by the furious indignation that had possessed her since she had left the car.

But once more the flat was empty.

This time she didn’t bother to look around or to search. She felt completely out of her depth, outwitted by a pair of conspirators, who, even now, she felt were watching her somehow, and laughing at her. Almost tearful in her frustration, and reluctant to return to the loneliness of the car, she began once more to walk slowly down the stairs, anxious to put off the decision of what to do next or where to go, and trying in some small way to recapture the relative serenity she had found the last time she had walked slowly back down from the flat in the warm, dark silence of the stairwell.

The door of the first-floor flat was ajar once more as she passed it, but this time there was no sound of a television, and the quietness surrounding her was deep and total and made her feel uneasy. She found herself missing the cheerful sound of the audience laughter that had reassured her those three days before. Once again, her footsteps creaked on the old floorboards of the landing, and she could hear her breath still escaping in little pants after the effort of the climb up.

As she started to go down the final flight of stairs she heard the sound of the door behind her being pulled further open. Almost as if she could feel it through the back of her neck, Eleanor sensed something extraordinary was about to take place. It seemed as if she knew exactly what she was going to hear just a split second before it happened, and it was almost calmly that she paused on the stair to listen, as the quiet, hesitant voice spoke gently into the twilight of the landing.

‘Ruth, dear, is that you? Is that you, Ruth?’

Eleanor turned round quickly just in time to catch a glimpse of the same grey-haired woman she had seen before. She thought she saw a flash of something like anxiety in the hooded eyes behind their gold-framed glasses as they looked into hers for a fraction of a second, but as Eleanor moved back up onto the landing and towards the door, it was closed quickly and firmly against her.

She stood outside it and considered. She wasn’t sure why she felt so certain that this woman was the key to answering the questions that had been plaguing her for three days. She could see, even in the state of suspicion and unease that clouded her normal logical practicality, that there were alternative explanations. Yes, it was possible that here was another coincidence: that this woman knew another Ruth; or that it was the same Ruth but here on an entirely innocent mission: that this friend of hers, or relative, just happened to have a flat in the same building as John – or not even just happened to, but had taken it on John’s recommendation. Ruth was an efficient, helpful PA after all; she knew about this place; she must ring John here in the evenings to deal with problems or prepare him for the next day’s meetings. She could well have suggested this location for her friend or relative and fixed it up for her.

But nothing that suggested itself to Eleanor’s weary mind could convince her. Even as she dismissed every alternative, she was walking slowly towards the closed door, certain that every step was bringing her closer to an explanation; willing now to face anything in the desperate and relentless need to know the truth.

She pressed the small white push button on the side of the door and heard the bell ring out quietly inside the flat. She thought she heard some movement inside, but after a few seconds it stopped, and the landing was as silent as before. She pushed the bell again, and then again, angry at the way this woman, whom she knew to be somewhere inside and listening, was ignoring her. Couldn’t she feel her pain, this person a few feet away from her? Wasn’t the lonely humiliation on this side reaching out to her on the other through the thickness of the wooden door? Surely she must be able to sense it? Eleanor rested her forehead on the surface of the door and closed her eyes. She pressed her finger back onto the bell push and held it there while she focused all her mental effort on the questions that still burnt into her brain, feeling almost as if she could transmit them by the force of her will into the flat beyond. Never having been a particular believer in the sisterhood of women, or in the idea of some sort of communion of the female spirit, she nevertheless now found herself appealing to some primitive common bond between herself and the woman on the other side, whom she knew now could, if she wanted, give her the answers she needed so desperately.

Please, she found herself silently begging, please, please tell me. Open the door and talk to me. I’m in agony here – can’t you feel it? You don’t look like a bad person; you can’t want me to suffer like this, surely?

Her head suddenly jerked forward as the door moved. For a confused second she wasn’t sure if she had somehow pushed it with the weight of her body, but as she lifted her head and recovered her balance she found herself looking straight into the glittering lenses of the woman who stood in front of her, holding the edge of the open door.

‘You’d better come in.’

Her voice was still quiet, but the eyes behind the glasses had lost their anxiety and gazed back into Eleanor’s almost challengingly.

‘Yes. Thank you.’

The layout of the flat followed the same pattern as that of John’s, but in reverse, and, as she followed the rather dumpy figure of the woman in front of her through the hallway and into the sitting room, Eleanor had the uncanny feeling that she was walking into the one upstairs, but in a surreal version that had somehow been changed into a mirror image of itself. She was half aware of the differences in colour and décor, but couldn’t shake off the dreamlike feeling that she was somewhere she had been before, and that it was the woman in front of her that was the visitor, and that it should be Eleanor ushering her into the sitting room and onto the floral sofa, not the other way round.