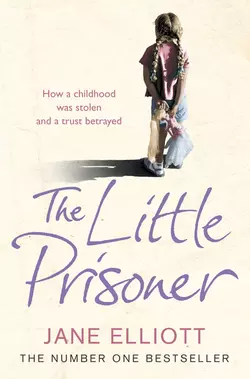

The Little Prisoner: How a childhood was stolen and a trust betrayed

Jane Elliott

An inspirational true story of a 4 year old girl who fell into the power of a man whose evil knew no bounds. She encountered terrifying mental and physical torture from her psychopathic stepfather for a period of 17 years until she managed to break free, her spirit still unbrokenJane Elliott fell into the hands of her sadistic and brutal stepfather when she was 4 years old. Her story is both inspiring and horrifying. Kept a virtual prisoner in a fortress-like house and treated to daily and ritual abuse, Jane nonetheless managed to lose herself in a fantasy world which would keep her spirit alive.Equally as horrifying as the physical abuse Jane suffered, were the mental games her tormentor played – getting his kicks from seeing Jane humiliated, confused, crushed and defeated at every turn.Her family and neighbourhood were all terrified of Jane’s stepfather so no-one held out a rescuing hand. So Jane had to help herself. When she was 21 she ran away with her baby daughter and boyfriend to start a new life in hiding. Several years on she found the courage to go to the police. A court case followed where Jane bravely stood up against the unrepentant aggressor she so feared. He was jailed for 17 years. Jane’s family took his side.

The Little Prisoner

How A Childhood Was Stolen and A Trust Betrayed

Jane Elliott

with Andrew Crofts

Evil is unspectacular and always human, and shares our bed and eats at our table.

W. H. Auden

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u0f5429f4-2a61-5f8d-824f-49ec29a8eb11)

Title Page (#ufa9d56db-b321-5e1b-b416-247ff8a94848)

Epigraph (#uf930a06d-be5d-5d9a-be7e-8ae3e7efeae1)

A Note from the Author (#u1b0bb09e-6432-5706-85f6-4222d3c97748)

Prologue (#u7e1d279e-9987-5bb2-a6b6-9ba4abe90f27)

Introduction (#u7c0c2b66-add4-56c6-8908-59ce8fec0001)

Chapter One (#ub62557bf-21f4-5a0a-ac95-4da34de5fc2b)

Chapter Two (#u3e2f55e7-b599-5f70-a4df-f0660124b361)

Chapter Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Make www.thorsonselement.com your online sanctuary (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

A Note from the Author (#ulink_aa1eb477-7e54-596c-b601-3b7ed9ed97ef)

As a child I never thought anyone would believe what I had to say, so when my book went straight to number one in the hardback bestseller charts and everyone was talking about how brave I was to tell my story, I found it hard to take in. One minute I would be hugging myself with excitement, and the next I would be frightened of what might happen now I’d let the genie out of the bottle.

Initially I wanted to write the book because I knew how much I’d been helped by reading A Child Called It by Dave Pelzer. If just one child who was being abused read my story, I reasoned, and felt inspired enough to speak out and end the cycle of bullying in their own life, it would be worth doing.

Every time my publishers rang to say they were printing more copies to meet the demand, I imagined how many more people would be reading it and maybe seeing that it was possible for them to turn on the bullies and regain control of their lives.

The actual writing process was hard because it stirred up one or two memories and emotions that I’d been trying to forget about. But now I’ve shouted out to the whole world all the things I was told had to be kept secret, it feels as though a lead weight has been lifted off my shoulders.

However hard I’d been trying to suppress the memories over the years, they were always there. I could distract myself with family chores, a bottle of wine or a packet of cigarettes, but that didn’t make the hurt go away for more than a few hours. Facing up to the memories and telling the whole story was like opening the curtains and windows on a sunny day and letting light and a fresh breeze into a dark room, stale with poisonous air.

One of my biggest worries was how my children would react to the book. They’re both still young and although they knew that something bad had happened in my childhood they didn’t know any details. I’ve told them the book contains material they might find upsetting and that I would rather they didn’t read it until they were older, and so far they’ve managed to resist the temptation – I think. The excitement of hearing their mum talking on the radio and seeing the book all over the shelves in the supermarket and W H Smith seems to have more than compensated them for any worries it might have caused them.

The hard thing for them is that they’re not allowed to tell their friends about it. This was particularly tough when it was at the top of the charts and they were longing to share the excitement that was going on within our little family group. But they’re all too aware of the dangers of disclosing my true identity and of my whereabouts being discovered by my family. They saw what happened to their mum last time her brothers caught up with her, and they don’t want to take the risk of that happening again. They keep telling me how proud of me they are. I just hope they realize how proud I am of them as well.

My husband has also had to adjust from being the sole worker in the family to having to stay home a lot to look after the girls while I was off at publishers’ meetings and giving interviews, but there have been some big compensations for him too. The sense of satisfaction I got from seeing how well the book was doing made me a lot easier to live with (not that I’m not still a bit of a nightmare for him some days!), and we have been able to pay off a few of the debts we were building up and improve our lives materially.

I don’t think he really believed the book would be a great success any more than I did, but it’s surprising how quickly we both got used to having a number one hit and started to feel disappointed when it got knocked down to number two or three!

The charts are full of stories of childhood abuse now and there have been a lot of articles in the press speculating on why so many people want to read about such a difficult subject. I don’t think it is the abuse they want to hear about, but the fact that some of the children who suffer from it manage to survive and ultimately triumph. They want to be shocked at the start of the book, crying in the middle and exultant at the end.

I suspect that the audiences for books like The Little Prisoner fall into two categories. Firstly there are those who come from stable, happy homes, who can’t understand how anyone can abuse a child, and want to find out about a world they can barely imagine. Secondly, there are those who suffered something similar themselves and find some comfort in discovering they are not alone in the world. They get some inspiration from discovering that not only is it possible to go on to lead happy and normal lives, but that you can actually turn all that misery into something positive.

I have a horrible feeling there are more people in the second category than anyone really wants to admit, and as long as the subject remains shrouded in secrecy and is considered a taboo to talk about, we’ll never know the full extent of the problem. With the popularity of books like mine, however, at least we have started to open the curtains and let a little light into these darkest and nastiest of corners.

If we don’t all understand what is going on in families like the one I came from, we can’t hope to make things better.

Prologue (#ulink_3815116c-4f55-56a4-aa21-c20a1c350e27)

When people talk about evil they are usually thinking of mass murderers like the fictional Hannibal Lecter or dictators like Adolf Hitler, but for most of us our actual encounters with evil are more mundane. There are the school playground bullies and sadistic teachers who turn their victims’ days into nightmares, the unkind care workers in the old people’s homes or the violent thieves who invade the lives of the elderly or infirm. Our brushes with these evils are usually passing or secondhand, but none the less chilling for that.

This, however, is the true story of a four-year-old girl who fell into the power of a man for whom evil was a relentless daily activity. She remained in his power for seventeen years until she eventually managed to escape and turn the tables. It is a story of terror and abuse on a scale that is almost unbelievable, but it also tells of her enormous act of courage which led to the arrest, trial and imprisonment of her persecutor.

Most of us don’t usually hear about children like Jane until we read about their deaths in the papers and then we all wonder how such things could be going on under our noses and under the noses of all the welfare workers who are supposed to be there to help. We try to imagine what can have gone wrong, but we can’t because these children live in a world that is unimaginable to anyone who hasn’t been there. This is the story of a survivor and we should all listen to what she has to tell us.

Jane Elliott’s story is almost unbearable to read in parts, but it needs to be told because the people who perpetrate these sorts of crimes rely on the silence of their victims. If people talk openly about what happens behind closed doors, then evil on the scale of what happened to Jane becomes harder to achieve. Bullies can only operate when other people are too frightened, ashamed or embarrassed to talk about what is being done to them. By telling her story, Jane is making it a little harder for evil to prosper in future.

The names of the characters have all been changed to protect Jane’s identity and the identities of those who helped her in her fight for justice.

Introduction (#ulink_ef07989b-097d-588a-8988-7f8b3c4b8cb8)

I was being led back into the courtroom by a victim liaison officer, an elderly lady. Up till then they had been careful to take me in and out of a different door from Richard, my stepfather, or if they hadn’t then they had made sure we didn’t meet, which was making me feel more confident. Hiding behind my hair, I had still been able to avoid seeing him and remembering his face too clearly. As I came back in through the door with my head down I saw a pair of shoes directly ahead of me, blocking my way. I looked up, straight into a face that made me feel sick with fear. The pale snakelike eyes and the ginger hair were the same, although he looked a little stockier than I remembered him.

‘Get me out of here,’ I hissed through gritted teeth, feeling his eyes boring into mine and his thoughts getting back inside my head. ‘Get me out, get me out.’

‘Calm down, for heaven’s sake,’ the lady said, irritated by such a show of emotion. ‘Come through here.’

She led me into a room off the court, which had a glass door. He followed us, but didn’t come in, standing outside the glass, just staring at me with no expression.

‘Get the police!’ I screamed. ‘Get the police!’

‘Don’t be silly, dear.’ She was losing patience now. ‘Who is it you’re worried about? Is it him?’ She gestured towards the immobile figure on the other side of the glass with the dead, staring eyes.

‘Get someone!’ I screamed and she realized there was no way she could calm me down. She walked towards the door. ‘Don’t leave me!’ I screamed, suddenly envisaging him and me in the room alone. The woman was panicking now, aware that she didn’t know how to handle the situation.

At that moment Marie and another police officer arrived. Finding me standing in the corner of the room, hiding my face against the wall like a child in trouble, they came to the rescue, furious with everyone and getting me to safety.

‘He’s going to kill me,’ I moaned as Marie put her arm round me. ‘I’m dead.’

‘No, he won’t, Jane,’ she soothed me. ‘He can’t do anything now. You’re doing fine. It’s nearly over.’

Chapter One (#ulink_852a650f-d95b-5df2-b74a-da9e618cf034)

Early childhood memories don’t always remain in the right order or come back the moment they’re called, preferring to remain stubbornly locked in secret compartments deep in the filing cabinets of my mind. Sometimes I can picture a scene clearly from as young as three or four, but I can’t remember why I was there or what happened next. Every now and then the lost memories will return unexpectedly and often it would have been better if they’d remained lost. I have a horrible feeling that there are still some compartments for which my subconscious has deliberately lost the key, fearing that I won’t be able to cope with what would come out, but which one day will allow themselves to be forced open like others before them. It is as if they wait until they know I will be strong enough to cope with whatever is revealed. I don’t look forward to seeing what’s inside them.

I can’t always piece together the order that things happened in either. I might be able to remember that I was a certain size at the time that some event occurred, but be unable to tell if I was four or six. I might be able to remember something that was a regular occurrence, but be unable to say whether it went on for a year or three years, whether it was every week or every month. I suppose it doesn’t matter very much, but this confusion makes it difficult to give a truly factual account of the early years of my life, since anyone else who might be able to remember those times will probably have reasons not to tell the truth, or at least to adjust it to make their role in it more bearable.

I do remember being in care with my little brother Jimmy. I must have been about three when we were taken away from home and he would have been about eighteen months younger, so still little more than a baby. I loved Jimmy more than anything in the world. My dad tells me that when he used to come and take us out of the children’s home for a pub lunch or some such outing, I would act like a little mother to Jimmy, feeding him and fussing over him. I don’t recall the outings, but I do recall how much I adored Jimmy.

The main things I remember about the children’s home were the brown vitamin tablets they used to dispense to us each morning in little purple cups, and being made to eat Brussels sprouts and hating every damp mouthful as they gradually grew colder and more inedible on my plate.

There was one woman working there who used to single me out from the evening line-up, after we had all been given our glasses of milk, and take me somewhere private, putting her finger to her lips as if we had a secret from the rest of the world. Then she would sit me down and comb my long hair, spending ages curling it and making me feel beautiful and special for a few minutes each day. (My hair was so dark and fine that people were always asking me if I was Indian or Pakistani.) When she’d finished her work the woman would give me a hand mirror to hold up in front of me so I could see the back of my head in the mirror on the wall and admire her handiwork. It seemed like a magic mirror to me.

Most of the information I picked up later about those early years and why we were taken away from home came to me because Mum was always happy to talk about me to other people as if I wasn’t there. I’d be sitting quietly in the corner of the room, waiting for an instruction as to my next duty, while she would be holding forth to some neighbour or other. Every so often she would remember I was there and remind me, ‘Don’t you ever let him know I told you that.’ My stepfather didn’t like anyone to talk about the past.

When I was in my mid-twenties I tracked Dad down and he’s told me a few things, but I don’t like to keep asking him questions. It seems that Dad had a bit of a drinking problem, which Mum made worse by playing around with other blokes and generally giving him a hard time. He had already left us before we were taken into care and Mum had started going out with Richard, or ‘Silly Git’, as I prefer to think of him. He might even have been living with us by then, although he would have been very young, no more than sixteen or seventeen. He’s only fourteen years older than me.

Jimmy and I were sent to a couple of different foster homes, one of which I think must have been quite nice, since I can’t remember much about it. The second one wasn’t so good. They seemed like evil people to me, but perhaps they were just very strict in a way I wasn’t used to. We were never allowed to whisper to each other, or speak unless we were spoken to, and when they caught me whispering to Jimmy one time they stuck a piece of tape over my mouth which had been holding together a pair of newly bought socks. I had to sit at the top of the stairs with the tape over my mouth all night while everyone else in the house went to bed.

Even though I wasn’t having a good time in the foster family, I still never wanted to go back home, but I wouldn’t have been able to explain to anyone why not.

‘I’m really looking forward to coming home,’ I would tell Mum when I saw her, but I absolutely wasn’t.

When we went back home for visits there was an atmosphere in the house that made me frightened, although nothing bad actually happened in those few hours. I would sit very quietly, not wanting to make the new man of the house angry, but Jimmy had no such inhibitions and from the moment we were dropped off he would scream with what sounded like terror. I could tell it made Richard angry and that frightened me even more, but nothing I could do would calm Jimmy down until the social workers came to take us back. We would just sit together on the sofa for the whole visit with him screaming and me trying to comfort him. Richard’s anger and our mother’s desperation would swell to what felt like dangerous proportions as they waited for the ordeal of the visit to be over.

Jimmy had a large scar right around his forehead, which has stayed with him into adulthood. I was always told that he got it from falling against the coffee table before we were taken into care. I accepted the story at the time, but thinking back now, it’s an awfully big scar to get from bumping into a table. He was only tiny, so it wasn’t as if he had far to fall, or much weight behind him. I wonder now if something more serious happened to him and that was why we were taken into care and why he was always so terrified to go back home. I don’t suppose I’ll ever know now because Jimmy was too little to remember.

Someone told me that we were taken into care because we were being generally neglected, that we had vivid, sore ‘potty rings’ from where we had been left too long on our pots, but everyone seems to be vague about the details.

Before we went into care we’d lived in a flat, but by the time my memories start to kick in Mum and Richard had moved to a council house. Maybe that was how they managed to convince the authorities that they were fit to have me back. They’d also had a baby boy of their own, called Pete, which must have made them look like a more normal family, like people who had mended their ways, matured and accepted their responsibilities. Richard was, after all, still a teenager, but there might have been a case for believing that he had now grown up enough to be put in charge of children.

I sometimes wonder whether Mum and Richard would have taken me back if I’d made as much fuss as Jimmy. Now I wish I’d given it a go, since Jimmy ended up being adopted by kind people, but at the time it seemed too dangerous to make Richard angry and I preferred to remain docile and well-behaved in his presence.

Years later I discovered that they had told the authorities they ‘only wanted the girl’. I couldn’t believe it, but Jimmy’s files later confirmed it. Jimmy had read the files himself and felt deeply rejected, even when I assured him that he’d had the luckiest escape of his life.

I also heard Mum boasting that our family had slipped a bribe to someone in the local authority to allow me home and that two senior people had resigned when they heard that I was being returned to ‘that hell-hole’, as it was described in some report. My missing files would make interesting reading, but it isn’t really important what happened in those first few years, because the real horrors were only just about to begin.

One of the scenes that has always remained clear in my head was saying goodbye to Jimmy on the doorstep of the foster home. He was crying and I wanted to as well, but didn’t dare to show my feelings to anyone. Someone had told me that Jimmy would be coming back home as well in a couple of weeks, but I didn’t believe it. I think I must have overheard something that told me they were lying. I knew they were going to separate us and it broke my heart. I’d hated it at the foster home, but at least I’d had Jimmy with me. Now I was going to be moved to somewhere else where I felt bad things would be happening and I wouldn’t even have him to cuddle and talk to.

I still didn’t tell Mum any of these thoughts; I just told her that I couldn’t wait to get home. I didn’t want to hurt her feelings. Little children only want to please their parents if they can.

From the moment Jimmy and I were parted I used to try to communicate with him telepathically whenever I was on my own. I had a birthmark on my arm which I convinced myself looked like the letter ‘J’, so I would stare at it and try to talk to Jimmy in my mind, telling him to be a good boy and assuring him that I would come to see him soon, asking him what sort of day he had had and telling him all about mine. I never did see him again until we had both grown up and grown apart, but at the time it comforted me a little to think I was still connected to him.

After Pete, Mum and Richard had three more boys, one almost every year, but none of them could take Jimmy’s place in my heart. I had to keep this quiet because I was never allowed to talk about him again. It was as if he had never existed in our lives. We had a lot of secrets like that. I was never allowed to tell anyone that Richard was my stepfather, not my real father, although anyone living in the neighbourhood must have known. My four half-brothers never realized that I wasn’t their full sister until I was in my late twenties and the court case brought everything to light. I was never allowed to have any contact with any of my relations on my father’s side; it was as if they didn’t exist. I have no memory of my grandparents on that side at all. It was as if Richard wanted to keep control of exactly what information was allowed.

My dad tells me that he tried to come and visit me in the house a few times, but was met with such violence and abuse that he decided it would be safer for me if he stayed away and allowed things to calm down. That seemed like the last of my potential allies gone, although I later discovered he had tried to keep an eye on what was happening to me in other ways.

One day a photograph of Jimmy fell out from behind another picture in an album.

‘Who’s that? Who’s that? Who’s that?’ one of my little brothers asked.

Richard immediately became angry, throwing the picture in the bin and making it clear that there were to be no more questions about the little boy in the photograph. Jimmy was no longer part of our family.

Any house we lived in inevitably became a gleaming domestic fortress. I guess that another reason why Mum and Richard were able to convince the authorities that they would be good parents to me now was that they kept their home spotlessly clean and totally secure. My stepfather was obsessed with decorating; there was never a day when he wasn’t redoing one room or another with new flock wallpaper, the sort you see inside old fashioned pubs, or applying another coat of paint, or putting up pine cladding or building fake brick fireplaces. I even used to cover my schoolbooks in the offcuts from old rolls of his flock wallpaper.

Our privacy was everything to him. Net curtains covered the windows during the day and would be reinforced by expensive thick lined velvet curtains as soon as the light outside started to fade. God knows where they got the money to buy them, but they ordered them from catalogues. There could never be a chink left in our armour, anything that would allow prying eyes the slightest opportunity to see inside our private lives. Outside the houses would be gates, high fences and even higher conifers. Locks and bolts would ensure that no one, not even members of the family, could get in and out easily. Richard’s control over his domain was total. Our houses were always the ‘nicest’ in the area.

All of us did housework all the time. Not a speck of dust or dirt ever escaped Richard’s eagle eye. If a bit of fluff came off one of our socks onto the carpet we were immediately screamed at to pick it up, so we would pad around in slippers to be on the safe side. Visitors could never believe that anyone could keep a house with children in so clean and tidy. Every kitchen cupboard would have to be emptied and wiped down every day, every item of furniture moved and cleaned and replaced, even the cooker and the fridge. Ledges above doors and windows that would normally be out of sight and out of mind were wiped down every single day. We sparkled and shone like an army barracks ruled over by a sergeant major prone to terrifying rages. The stairs had to be brushed by hand each morning and Mum would then vacuum them three or four times more during the course of the day.

The garden received just as much attention, the edges of the lawn having to be trimmed with scissors.

But doing housework was a way of keeping busy and out of Richard’s way in case he was in one of his moods.

Richard was about four years younger than Mum and only eighteen when I was taken back home, but to me he was still a fully grown adult and I knew that to answer him back or disobey him in any way would be to endanger all our safety. Children know these things instinctively, just as they know which teachers they can play up at school and which ones will never tolerate any bad behaviour. Even though I’d hated being made to take tablets at the children’s home, I’d never been frightened to fight back against the staff administering them, but something about this man told me that if I fought back or protested in any way, things would become a thousand times worse.

He didn’t look like a monster, although he was over six feet tall, slim and muscular. He had ginger hair and pale snakelike eyes and always dressed casually but smartly. He took great care of his appearance, just like his home. I ironed his clothes so often over the years I can remember exactly what he owned: the neatly pressed pairs of jeans and polo shirts, the v-necked jumpers and Farrahs trousers. When I got older my friends sometimes used to tell me they fancied him, which made me want to be sick because to me he seemed the ugliest thing in the world. He had a tattoo of Mum’s name on his neck to show the world how tough he was.

The moment I was swallowed up into the house and invisible to the outside world, he made his hatred of me plain. Every time he passed me when Mum wasn’t looking he’d slap me, pinch me, kick me or pull my hair so hard I thought it would come out at the roots. He would lean his lips close to my ears and hiss how much he loathed me while his fingers squeezed my face painfully like a vice.

‘I hate you, you little Paki bastard,’ he would spit. ‘Everything was good here until you came back, you little cunt! You are so fucking ugly. You wait till later.’

His hatred for me seemed to be so powerful he could hardly control himself. To call me a ‘Paki’ was the worst insult he could think of, since he carried his racist views proudly, like badges of honour.

He took to spitting in my food whenever he had the opportunity and I would have to mix the spittle into the mash or the gravy to make it possible to swallow, since he would force me to eat every last scrap.

‘You ain’t leaving the table until you’ve eaten every mouthful,’ he’d say, as if he was merely a concerned parent worrying about his child’s diet, but all the time he would be grinning because he knew what he had done.

When my brother Pete was old enough to talk he saw it happen one time.

‘Er, Dad,’ he screeched, ‘why did you spit in Janey’s food?’

‘Don’t be stupid,’ he snapped. ‘I didn’t.’

When I saw that Mum’s attention had been caught, thinking I had a witness in little Pete, I found enough courage to say, ‘Yes, he did. He always does.’ But she couldn’t believe anyone would do such a disgusting thing and so from then on Richard was able to turn it into a double-bluff, making loud hawking noises over my plate and then dropping even larger globs of phlegm into it when my mother looked away, tutting irritably and telling him ‘not to be so stupid’, as if it was no more than a joke that she no longer found funny.

I think she must have known how much he hated me, though, because she never seemed to like to leave me alone in a room with him for any length of time when I was tiny. If she could see he was in a mood and she had to go to the toilet, she would call me to come with her, a bit like calling a dog to heel. When we got inside she would make me sit down in front of her with my back to her knees while she did her business. I can’t think of any other reason why she would have done that, but we never spoke about it and I was always happy to go with her, knowing that it was saving me from a slap or a kick. What she never realized, however, was that Richard didn’t have to be in a mood to hit me or punch me or hiss insults into my ear – he did it all the time.

The house had three bedrooms, so I had a room of my own from the start and it was beautifully decorated, just as a little girl’s bedroom should be. To begin with my wallpaper was ‘Sarah Jane’ with pictures of a little girl in a big floppy hat, then it was changed for a Pierrot design, and later a pattern of horses. I had loads of toys, too, but I was never allowed to play with them unless I did Richard some ‘favour’ in return.

These favours became my way of life. If Mum let me go out to play while Richard was out somewhere and he came home and found me outside, then I would ‘owe him a favour’. If I wanted to eat a sweet or go to a friend’s birthday party or watch The Muppet Show, he might say yes, but would let me know that I would be paying him back with a favour later. In the end I stopped asking for anything, but he would still demand the favours or call them ‘punishments’ for some ‘crime’ instead, like being rude or sulky. Looking back now I realize that he was going to make me do the favours anyway, so I wish I had got more in exchange for them, but I wasn’t able to see so clearly what was happening at the time. He managed to make it all so confusing and frightening. My favourite toy was Wolfie, a giant teddy with a dog’s head, which was almost as big as me. Wolfie had braces which I used to slip my arms through so he would dance with me and walk around the room. He was my best friend.

If Mum was in the house when Richard wanted to punish me he would whisper in my ear, ‘Watch this.’ He would then start shouting at me about something and shouting at my mum about what a moody cow I was. Seeing the sort of temper he was in, Mum would agree with him, tutting sadly at what a tiresome girl I was. Richard would then kick me and slap me and drag me upstairs by my ponytail, making me lose my footing so that I was literally being dragged by my hair. He would tell Mum that he was going to put me to bed and give me ‘a good talking to’ and would then beat me even more viciously once we got there.

‘Wait till your Mum goes out,’ he’d tell me as he crushed my face between his fingers, ‘then you’ll get it.’

In the beginning when he used to hit me with his hand, a slipper or a stick, I would always cry. Quite soon, however, I decided that I wouldn’t give him the satisfaction any more. I couldn’t stop my eyes from watering up with the pain, but I found that if I just clenched my teeth and stared at him I could stop myself from actually crying. It was the only little bit of defiance I could find the courage or strength for, and it often made the beatings worse.

‘Not crying?’ he would say. ‘Isn’t it fucking hurting enough then?’

But then when I had cried he would become even angrier and tell me he was going to ‘give me something to cry about’. I guess he was always going to do whatever he wanted, regardless of what I did or said.

I think Mum knew that he was going too far sometimes, because after he had put me to bed she would sometimes creep into my room to check that I was still breathing. I used to breathe really shallowly, just to give her a fright and to punish her for letting him hurt me. It was a mean thing to do, but I was cross with her.

‘Janey, Janey,’ she would whisper and I would open my eyes suddenly, as if I had been asleep. ‘Breathe properly,’ she would scold me, angry that I had frightened her. She never raised her voice because she didn’t want Richard to know that she had come up to check I was alive. Although I was angry with her for not helping me, I was also relieved that she wasn’t getting beaten up herself.

Other times Richard would tell me what he and I were going to do later and if I didn’t look pleased, or turned away or cried, he would say, ‘Right, you ungrateful bitch, now look what I’m gonna do. I’ll teach you.’ He would then start rowing with Mum and beat her up in front of me.

‘The only reason your mum and me ever argue is because of you,’ he would tell me over and over again, and I believed him, the guilt weighing heavily on my soul. I learnt that I must always agree with him, always smile and always be grateful for everything or there would be terrible punishments for me and my mum.

Like a small boy pulling the wings off insects, or stuffing them into jam jars and watching them starve or suffocate, Richard seemed to enjoy making me suffer for no reason at all. The airing cupboard for the house was in my room and he used to like to make me strip my clothes off and crawl inside amongst the piles of towels. I don’t know how long he left me in there, because time is immeasurable when you are small and frightened and sitting in the dark, and I don’t know if the door had a lock on it, because I never had the nerve to try to get out until he told me I could. Disobeying orders would have brought a far worse punishment down on my head. The rule was to endure whatever he told me to endure, and to do so with a cheerful smile and gratitude. Being a ‘sulky cow’ was one of the worst ‘crimes’ I could commit. He would sometimes come back just to check I hadn’t fainted from the heat, then he would shut the door again and leave me in the dark once more with no idea how much longer I would be there.

There was a ledge in my room too and I remember being made to stand on it, but I can’t remember what happened next. One day that memory will probably return as well, but I’m not looking forward to it.

These physical humiliations and discomforts, however, were not as unsettling as the mind games, which started almost immediately I came back home.

‘Go and turn the hot water on for me, Janey,’ Mum would say and I would run upstairs to the immersion.

‘Go and turn the hot water off,’ Richard would tell me as soon as I got back from turning it on. I would know to obey without saying anything.

‘Why didn’t you turn the water on when I asked you?’ Mum would want to know a little while later when she went up for her bath.

‘I did,’ I would protest. ‘He told me to turn it off again.’

‘You bloody little liar!’ he would explode and I would have no chance of convincing Mum that I was telling the truth once he started ranting and raving. If I’d argued any further I would have got a beating, so I just stayed quiet, knowing it wouldn’t be long before he thought of another game.

When it came to the beatings Richard liked to vary the implements he used. Sometimes it was a slipper, or a hand or a bamboo stick. He would make me choose which it was to be. As I got older the beatings got less, perhaps because they had served their purpose in training me to obey him. Instead I would just be punched or smacked around the head or thrown across the room or made to pay a forfeit by doing a favour. Whatever happened, I would never be let off a punishment.

‘Do you want breakfast, Jane?’ Mum called through from the kitchen one morning to where I was sitting on the sofa in the front room.

‘Yes please,’ I called back.

‘No, you don’t,’ my stepfather hissed from the nearby armchair. ‘Tell her you don’t want any.’

‘No, I don’t want any really,’ I shouted.

‘Why not?’ Mum asked, appearing in the doorway.

‘She must be fucking mad,’ he yelled, jumping up from his chair. ‘She doesn’t know what she fucking wants. Do you want fucking breakfast or not?’

‘Yes, please,’ I said in a small confused voice.

‘What do you want?’ Mum asked, shaking her head in puzzlement.

‘Toast,’ I said and she went back to the kitchen to make it for me.

The moment she was out of sight Richard’s fingers closed painfully round my face like a clamp and he was whispering again, his face inches from mine. ‘I told you, you don’t want any fucking breakfast. Now fucking tell her.’

‘I don’t want any toast, Mum,’ I obediently called out to the kitchen. ‘I don’t really want anything.’

‘Stop messing me about, Jane!’ she shouted.

‘Stop messing your mum about!’ Richard screamed, hitting me hard around the head. ‘She’s fucking mad,’ he called out to Mum. ‘She just likes stirring up fucking arguments!’

He was always playing these mind games to make Mum angry with me and to give him an excuse to smack me around. I just ended up so confused.

I know which memory is the first one I can find which has a sexual connection, but I think there may be even earlier ones lying in wait beneath the dust somewhere. This one must have happened a couple of years after I came back home because I remember I was sharing a bed with my brother Pete. My next brother, Dan, was also in with us in a separate bed. I’d been turned out of my room because it was having one of its routine redecorations and Pete and I were lying top to tail in his bed. The reason I think something must have happened before is because I remember I was awake and listening that night, terrified of what was about to happen. I’d heard my mother going out, the front door shutting after her, and I’d known that Richard would soon be upstairs to get me.

Every sound told me a story. The living-room door opened downstairs and I could sense Richard’s stealthy footsteps on the stairs. I closed my eyes, trying to stop my body from shaking so that I could pretend to be asleep. I thought maybe I would be safe because Pete was lying beside me and Richard wouldn’t want to wake him up. I was always clutching at straws like that to give myself some hope, and I was always disappointed.

I could tell the door was opening beside my head and I could feel Richard moving me about to wake me up. I opened my eyes and looked at him.

‘Come out here,’ he whispered, ‘quietly.’

I climbed out of the warm bed, leaving Pete sleeping peacefully, and Richard closed the door behind me. I stood on the landing, waiting as he shut the other doors on the landing and knelt down in front of me.

‘We’re going to play a little game,’ he said. ‘Shut your eyes and don’t you dare open them.’

I obeyed him without question and heard him unzipping his trousers.

‘Don’t open your eyes,’ he repeated. ‘We’re going to play the game now.’

I nodded, not wanting to make him angry.

‘I want you to play with my thumb. You hold it, and stroke it and move it up and down, and something magic will happen.’

I knew it wasn’t his thumb that he put into my hand, which also makes me think something must have happened before that, but I played along and pretended, just as he had told me. The more co-operative I was, I thought, the sooner I could get back to bed and the more likely I was to avoid a beating.

‘What is it you’re holding?’ he asked every so often as I worked away.

‘Your thumb,’ I replied obediently and then the magic happened and he told me to go to the bathroom to wash my hands. Some of his mess had spilled on the carpet and he rubbed at it with his foot, making the scratching noise that I would hear so many times over the coming years.

As I came back out of the bathroom I looked at the patch of disturbed pile on the carpet and couldn’t believe that Mum wouldn’t notice it when she got home. As the years went by more and more of these patches would appear, reminding me every time I walked past of the things I’d had to do.

‘Do you want something to eat then?’ Richard asked, and I nodded. ‘Come downstairs and I’ll make you some toast and tea.’

He was really nice to me that time, just as if we had been playing a game that we’d both enjoyed, but he wasn’t always so pleasant after he’d had his way. One night he took me into the kitchen and grabbed the long wooden-handled carving knife from the drawer, pinned me against the wall and pressed the razor-sharp blade against my neck.

‘If you ever tell anybody what we’ve done I’ll kill you,’ he snarled in my face, ‘and then I’ll kill your mum and no one will ever know because I’ll just tell them you both ran away.

I believed he was capable of it because I’d seen how hard he beat Mum when she made him angry, slamming her head against the floor or the walls and smashing chairs down on her while I sat on the sofa watching and hugging my little brothers as they screamed. He would always tell me that it was my fault, and I believed him. I felt so guilty, and I was terrified he would kill Mum and then I would have no one to protect me from him at all.

Almost as soon as I got back home I was old enough to go to infant school. I loved everything about it, but most of all I loved the fact that it allowed me to get out of the house and be with people who appeared to like me. All through my school years there were several people who seemed to go out of their way to talk to me and ask me how I was. Only later did I discover that they were friends of my dad’s and that they were trying to find out if I was alright for him. Right from the beginning one of my friends’ mothers was reporting back to him. Because I was always so happy at school, and because I didn’t carry any visible signs of abuse, they were able to report back that all was well. If only I had known that, I could have communicated with my dad through them and maybe he would have found a way to get me out of that house.

I think there must have been some people who had an idea about some of the things going on in the house, though, because social workers would come to the door sometimes, but Richard would physically throw them out and I never knew what happened after that because when the police went to look for my files years later they’d disappeared. None of the social workers ever came to speak to me. I can’t blame them if they were frightened off; Richard frightened almost everyone. I dare say there were people around who were as physically strong or even stronger than him, but when he went into one of his blind rages he lost all his inhibitions and very few people were able to match his levels of aggression and viciousness.

Family life provides so many little opportunities for grown ups to inflict pain on their children if they so choose. Mum always bathed us when we were little, but a couple of times Richard got to do it. I guess Mum was ill or too heavily pregnant and he was able to make it sound as if he was doing her a favour by taking over this chore.

One night he told me he was going to wash my hair and I was trembling with fear as we went upstairs, wondering what horrors he had planned. There was no way out. Stepping into the bath I was like a condemned man walking up the steps to the guillotine. Everything went as it should for a few minutes and I stayed as quiet and happy-looking as I could manage. Richard was giving no clues as to when he might pounce or how, but I wasn’t fooled, I knew it was coming.

When it was time to wet my hair I felt his hand gripping me tightly. He pushed my head under the water and held it there, no doubt enjoying the feeling of having the power of life or death over me. As I fought for breath and the water rushed into my mouth, I thought I was going to die, that he had finally decided he hated me so much he was going to kill me. My childish struggles were useless against the strength of his hands and only served to make him angrier.

After what seemed like an age he pulled me up into the air by my hair, squeezing my face painfully as I wailed and hitting me round the head.

‘Shut up and stop screaming!’ he hissed through gritted teeth.

I forced myself to be silent as he washed my hair as though nothing was wrong, knowing that in a few minutes I was going to have to rinse the soap out and certain he wouldn’t be able to resist the temptation of repeating the attack. When the moment came I tried to hold onto both sides of the bath, but he ordered me to loosen my fingers and pushed me back under the water again, infuriated even further by this futile attempt at self-defence, this challenge to his power. I came up a few seconds later, spluttering and screaming, and he put his hand over my nose and mouth, swearing in my ear to shut me up. He then dragged me painfully out of the bath, gripping my arms so hard I thought he would crush them and banging my legs on the hard edges.

‘Get your pyjamas on!’ he shouted and I obeyed, relieved to be out of the water and still alive.

I went downstairs to the front room on wobbly legs and when I saw Mum I burst into tears.

‘What’s wrong with you?’ she asked.

‘He tried to drown me,’ I replied.

He must have heard me and came charging into the room, screaming and shouting about how naughty I had been, how I had refused to have my hair washed and had made a fuss when the soap went into my eyes.

‘Oh, she never likes having her hair washed,’ Mum agreed. It was always easier for her to agree with him if she didn’t want to get a beating herself.

I was sent to bed with a smack for being so uncooperative.

Sometimes when I was in the bath Richard would put a ladder up the side of the house and look in the window, treating it as a joke. Mum would laugh, too, telling me I had to get over feeling shy about myself. Richard always managed to make it sound as though he was doing everything for my own good, as though everything that happened to me was my own fault.

When we were little we were only allowed to have baths on Sunday evenings and always had to share the water in order to keep the bills down. As I got bigger Richard started to let me have one during the week as well. Sometimes he would come down from having his own bath and tell me to have one in his water. He would always leave something that looked like semen floating on top of the water. The first time it happened I tried to get out of it by wetting my hair in the basin to look as if I’d had a bath, but he came upstairs to check on me. He opened the door and smirked at me as I climbed into his filthy water, no doubt knowing how disgusted I was. When I came downstairs afterwards I was quiet and ‘sulky’ so I got a good hiding and was sent back up to bed.

When I was seven I decided that I couldn’t face going home any more. The time had come to run away. I used to daydream about escaping all the time, but when it actually came to doing it things seemed to become more complicated. I was convinced at that stage that Richard could read my mind and that he would be able to tell what I was planning, which made me doubly anxious.

Sometimes he did seem to know things that I was sure I’d never told him. Only years later did I realize that they were things I’d told my mum and that she must have passed them on to him, betraying my confidence every time.

Other times he would trick confessions out of me. ‘I know you was mucking about at school today,’ he would tell me when I got home, ‘because the school board woman came round.’

I would rack my brain for the slightest thing I might have done which could have resulted in being reported like this. Filled with guilt as I always was, it wasn’t hard to find something and to convince myself that Richard truly did know everything. Believing it was hopeless to try to resist his powers, I would admit that I had been bad and he would then be free to punish me in whatever way he pleased. I doubt if I ever really did do anything very bad at school, apart perhaps from talking too much.

I had a friend at school called Lucy and had told her about my stepdad beating me and threatening to kill me. I hadn’t told her about any of the other stuff; that would have been too embarrassing. Lucy said she wanted to run away as well, although I don’t think she was having any particular problems at home, just fancied an adventure. I wasn’t trying to escape from school, because I really liked my teacher, but it seemed more sensible to us to go during the lunch hour, when we were less likely to be missed, than to wait until the end of the day.

‘I want to take my sister with us as well,’ Lucy told me as we were laying our escape plans. Her sister was in the infant school, which was next door to the junior school where we were in our first year.

‘How are we going to get her?’ I asked.

‘I’ll tell her dinner lady that she has a dentist’s appointment,’ Lucy explained, apparently confident that this would work.

I waited in the bushes beside the playground while she disappeared into the infant school. I was so excited by the prospect of finally getting away that my heart was thumping.

A few minutes after going in Lucy reappeared and came running across the playground towards me.

‘The dinner lady didn’t believe me,’ she panted. ‘She went to check, so I had to run for it.’

‘We’ll have to go without your sister,’ I said, and she nodded her agreement.

We ran as fast as we could to get out of the area of the school, which wasn’t easy for me because I had such stupid shoes. Silly Git always went with me to buy my clothes and shoes and for some reason he wouldn’t let me go into the shop that sold sensible school shoes. He always made me buy high-heeled court shoes with pointed toes and then insisted on putting blakeys (those little metal tips) on the heels so that I would make a noise when I walked in them and everyone would turn round to look as I went clacking past on my skinny little legs. I suppose it must have turned him on or something, but I kept twisting my ankles because I wasn’t used to walking in heels. He didn’t care about details like that. Lucy was always really keen to borrow my shoes, believing them to be the height of sophistication. I would have been happy never to have seen them again as long as I lived.

By the time school was over we had managed to get a long way away and had reached a row of shops on a new estate.

‘I’m really hungry,’ I complained. ‘Have you got any money?’

‘I’ve only got five pence that my mum gave me for crisps,’ Lucy said dubiously. ‘That won’t get us far. We’ll have to nick something.’

I’d never stolen anything in my life and the thought of it filled me with horror. What if we were caught? They would be bound to take us home and that would give Richard the perfect excuse to beat me half to death. But hunger got the better of my fears and we went into a little supermarket to see what we could get. We must have been looking very suspicious, hanging around for too long, because the woman behind the till threw us out, by which time Lucy had managed to steal a cake but I had only managed to get a plastic Jif lemon, having panicked and grabbed the first thing that came to hand.

‘Can I try your shoes?’ Lucy asked as we sat munching on the cake in a nearby underpass.

I agreed happily, since my feet were hurting from walking so far in them. We changed socks at the same time, so that I could have her long ones with pictures of the Flintstones up the sides, and then continued on our way.

I was desperate for the toilet, but there was nowhere else to go other than beside the path. I was just getting down to business when a woman came round the corner with her kids. Unable to run away, I had to answer her questions about where our parents were and whether they knew we were there. I don’t suppose my answers were very convincing. She eventually went away, but I suspect she was planning to ring the police the moment she got to a phone.

We continued on our journey and by the time we reached open fields it was starting to get dark. Lucy was beginning to talk about the possibility of going home, but then she didn’t have anything to be afraid of when she got there. I knew that my parents would have been told of my disappearance by now and that I was going to be in serious trouble. I wanted to keep walking forever. I didn’t care how dark or cold it got, nothing could be as frightening as stepping through my own front door.

Some bigger children were coming out of a senior school and we had to walk past a bunch of them. They were all staring. I guess we must have looked like the runaways we were. There wasn’t much chance that we were going to get away with our break for freedom for much longer and in fact the next figures who appeared out of the darkness were a couple of police officers. A terrible fear gripped me when I realized they were going to take me home. I would rather have lived in the woods forever than take another beating. But I could tell Lucy was quite relieved to have been found before night set in.

The police told us off for all the trouble and worry we had caused everyone and escorted us back to their car.

‘Why did you run away?’ one of them asked as we drove towards home.

‘Her dad says he’s going to kill her,’ Lucy replied, ‘and he beats her all the time.’

Just when I thought things couldn’t get any worse, they had.

‘Is that true?’ the policeman asked.

‘No,’ I shook my head. ‘I was lying when I told her that. It never happened.’

I looked down at the floor to avoid his eyes and realized we were still wearing the wrong shoes and socks. I would be in even more trouble if I got home without my own stuff.

‘Quick,’ I whispered to Lucy, ‘swap back.’

I was now more frightened about the punishment for this than I was about the punishment for running away. We were practically at my house by this time and only had time to change the shoes. I would have to take my chances with the socks.

The moment my mother opened the door she was shouting at me. She didn’t seem at all relieved that I was safe, just angry at what I’d done. I was freezing cold and sweating with fear at the same time. When I heard the policeman telling her what Lucy had said about Richard beating me and threatening to kill me, I knew that I was really in trouble.

‘Get upstairs to your bedroom,’ she shrieked the moment the police had gone, ‘and wait there until your dad gets home so he can deal with you.’

He was out, apparently searching for me, and so I got ready for bed with a heavy heart, knowing just what was going to happen once he returned. I couldn’t sleep as I lay there listening for the sound of him coming back into the house.

Eventually he was there and I could hear him shouting like a lunatic at Mum and then there was the sound of his feet running up the stairs. His voice was so loud and angry I couldn’t make out the words as he ripped the blankets off me and started punching me so hard I thought he was going to kill me. The pain was so bad I actually hoped that this time I would die. In my panic I wet myself and it soaked his arm, making him even angrier and more violent.

I didn’t go back to school for about a week after that and was bought lots of new clothes and things, so the bruises must have been pretty bad. They always kept me off school if there was any chance the teachers would see what they’d done to me.

Chapter Two (#ulink_cd058e59-5f3f-52af-b0af-e0f4ba729cbe)

Torture and cruelty can so easily become routine. Just as Richard could make a joke of pretending to spit in my food to disguise the fact that he was actually doing it, so he could also refer to me, apparently jokingly, as ‘Paki slave’. I had to pretend not to mind, otherwise I would have been the one who couldn’t take a joke and I would have got a hiding for lacking a sense of humour.

Richard never made any secret of how much he hated all black and Asian people and the fact that I had dark hair and an olive skin that tanned the moment I looked at the sun was enough to categorize me as different and inferior to the rest of the family, someone he could treat in any way he wanted.

He would tell me to sit on the floor in the front room because I was a Paki slave, while they all sat on the comfortable chairs and the sofa. Just as I sat down he would snap his fingers.

‘Paki slave, make me and your mum a cup of tea.’

‘Paki slave, clean the boots.’

‘Paki slave, take the washing out.’

‘Paki slave, put the immersion on.’

It would be said as if it were just a game, but I knew I would have to obey the orders with a smile if I didn’t want to get a beating for being a bad sport.

By the time I came back into the room with the tea Richard would be giggling with my brothers, encouraging them to snap their fingers like him and send me on another errand. ‘Make her do what you want,’ he’d tell them, and they would laugh, treating it like the game he was pretending it was. But I had to do what they told me as well, or I would have been accused of not joining in the fun and would have been punished for being a miserable cow.

This ‘joke’ went on for years. I didn’t blame the boys – they didn’t know any better and they were as anxious to do as they were told as I was. If the shoe had been on the other foot I expect I would have done the same in order to avoid the beatings. When he was throwing us from wall to wall and punching and kicking us, Richard didn’t seem to care what damage he might do. It was as if shutters came down in his brain and he lost all control and reason. No one ever wanted to be on the receiving end of one of those explosions.

At other times, however, he was entirely in control of what he was doing and his malice could not be excused by temper. He used to make me light his cigarettes for him, even when I was small. He got the boys to do it as well, but they just used to lean them on a bar of the electric fire or the top of the cooker until they started to smoulder, whereas I was made to get down and puff to make them light more quickly.

Richard believed that we should be taught how to inhale properly, especially the boys. Sometimes he would make them smoke a whole cigarette, while he and Mum laughed at them and exclaimed how cute they looked as they turned green and coughed as if they were going to choke.

When my brother Dan was two or three they made him light up and suck the smoke in and he started choking and turning red and purple. After a while their laughter turned to panic and they started screaming at him to breathe and banging him on the back. Richard picked him up by the ankles and smacked him like a newborn baby, yelling at me to go and get him some water.

Lighting those cigarettes gave me a taste for smoking by the time I was eleven or twelve, but I knew that if Richard found out I’d taken up the habit he would find some way to turn it into a torture, so I tried to keep it secret for as long as I could.

When I was thirteen I went on a school trip to Belgium that my granddad had paid for. I must have stunk of fags when I got back. The following evening Mum went out to have a cup of tea with a friend across the road, leaving me with Richard.

‘You’re smoking, aren’t you?’ he said as soon as we were alone.

‘No.’ I wondered what was coming next.

‘You are,’ he said, overruling my protests. ‘Here’s a fag. You either smoke it or you eat it, unless you tell me the truth.’

I took the cigarette, lit it up and smoked it in front of him.

‘Inhale it properly,’ he ordered. ‘I ain’t wasting my money buying you fucking fags if you ain’t gonna smoke them properly.’

Once I’d proved to his satisfaction that I was able to smoke properly he gave me a pack of ten, which I took straight up to my bedroom. By the time Mum came back across the road I was leaning out of my bedroom window puffing away happily.

‘Alright, Mum?’ I said cheerfully.

‘What are you doing?’ she asked, obviously horrified at the thought of what would happen if Richard saw me.

‘I smoke now. It’s alright, Dad says I can.’

I guess it didn’t bother them because they worked out that if I was a smoker they would soon be able to cadge cigarettes off me when they ran short.

To start with Richard offered me a choice: I could have money for sweets each day or I could have fags. I chose the fags and for the next few mornings there would be a pack of ten waiting for me in a brass horsecart on the mantelpiece. It soon dwindled down to one or two loose ones, which I would use to refill my packet.

There was an awful lot of brass around the house – horse brasses on the wall, brass ornaments on every surface – all of which had to be polished regularly. Mum and Richard did have two big heavy brass soldiers as well, but he got rid of them because Mum kept using them to defend herself when he attacked her.

‘You’re gonna fucking kill me!’ he’d protest whenever she laid into him while fighting back.

As well as cleaning the house from top to bottom several times every day, we had to clean all our boots and shoes, and it had to be done properly, melting the polish into the leather in front of the fire before brushing it in. Everything had to be spotless and shiny, right down to the toilet seat, which was polished so often it was hard not to slide off it. Richard would insist that I made my bed with hospital corners that were exactly ninety degrees. I had no idea what ninety degrees meant, but he still warned me he would be checking them. If ever I complained to Mum, he would tell her he was just joking and that I was a stupid cow to take him seriously, but when we were alone he was deadly serious. If I did anything wrong I would be hit or have to pay a penance.

Every little task that he set me I did to the very best of my ability, but it was never enough. If anything, it seemed that the more I tried to please him, the further he wanted to push me, just to show that he could, just to inflict pain, just to show me that I was only allowed to live because he chose not to kill me.

The idea of hurting me must have been playing on his mind all the time, the urge to prove his power over me too delicious to resist. One of his favourite tortures, which started almost as soon as I came home from care, was to suffocate me in bed with my pillow, or with one he brought into the bedroom with him, pressing it down onto my face so hard that I was sure he was sitting on it with all his weight, although he was probably just using his hands. He was very strong when he was excited or angry.

The first few times it happened I was unable to stop myself from screaming as I fought for breath, but I soon learnt that that made it worse because it used what little air there was in my lungs and nobody could hear through the pillow anyway. I would thrash around in my panic, trying to escape, but there was no hope of that happening until he was ready to release me.

When he finally lifted the pillow he would squeeze my face painfully. ‘I fucking hate you,’ he would say, his face almost touching mine. ‘Everyone fucking hates you.’ He would then slap me a few times and press the pillow down again.

The only time he would let me get some air was when he thought I was about to pass out. He would check this by lifting my arm and letting it drop, so I learnt to go limp earlier, but he soon cottoned on to that and became angrier still.

I would usually become so frightened under those pillows that I would wet myself, which made him even more incensed, and he would push my face into it like a puppy, rubbing the wet sheet roughly against my skin to teach me a lesson. He’d tell Mum I’d wet the bed, which was why he was angry with me, so she would shout at me too. Sometimes, if she had been out, he would tell her he’d given me a drink which I’d spilled down myself, which would explain why I was in different pyjamas when she came home. That would give him another reason to hit me and shout angrily, and then he would do it all again.

Because the suffocating happened nearly every night I tried different tricks to try to make it better. I would lie on my side when I heard him coming up the stairs, because I found I could breathe more easily that way, and then I decided I could get more air through the mattress than through the pillow, so I would lie on my front, sometimes putting the pillow over my head in readiness for the attack. Richard realized what I was doing quite soon and would put another pillow under my face so that there was no escape. The only thing I could do was stay as still as possible and take shallow breaths. Instinctively I worked out that if I lay quite still it would make it less exciting for him and he was more likely to become bored. I half-hoped that he would succeed in killing me, but he was too cunning for that, always pulling back at the last minute.

It was worse when Mum went out, but sometimes he would even do it when she was downstairs. But there were some tortures, or ‘games’ as he preferred to call them, which he was happy to inflict on me whoever was around. There were ‘thumb jobs’, for instance, which entailed him bending my thumb down as far as he could until I was crying out from the pain. That was one he would do for laughs. Another was to make me spread my fingers out on a wooden surface and he would stab a sharp kitchen knife down in between them at faster and faster speeds to show how accurate and fast his reflexes were. Once he carried this further by throwing a paint scraper at my feet so that it sliced between my toes, pinning them to the floor.

If Mum was in the house he might leave me alone after the suffocation game, but if she was out it would just be the start of his night’s entertainment.

‘Come out here,’ he would say once he was bored with the pillow trick, and I would obediently make my way out into the hallway, knowing what was coming.

The ritual was more or less the same each time for many years. He would strip his clothes off and bend over the top few stairs.

‘Lick my arse,’ he would instruct me and I would reluctantly make my way up to him. I would start by licking his cheeks, hoping he would let me get away with that. That was bad enough, but I always knew it wouldn’t be enough for him.

‘Lick the hole!’ he would snarl at me angrily, and I would have to do it, however sick and humiliated it made me feel. Then he would make me push my finger into it as hard as I could. I guess my finger wasn’t big enough to reach wherever he wanted me to reach, though, because then he would often do it to himself.

These nights always had to end with him giving me oral sex and me masturbating him. If Mum was out for the whole night, he would keep the ‘games’ going for hours. Sometimes he would want me to smack his bum and tell him he was a naughty boy. Sometimes he would make me go on all fours, with my arms and legs straight, and he would rub his penis around my back and front entrances, pushing into my back entrance.

The force of his weight would make me move away even if I tried not to, which wasn’t what he wanted, so he would take me downstairs to the sofa so I couldn’t move. At other times he would lay me across his lap with my knickers down, or off completely, and smack, bite, kiss or play with my bottom and my vagina.

‘I can’t stand to look at your fucking ugly face!’ he’d tell me, and I would have to kneel with my face pressed against his bottom and put my arm through his legs to masturbate him. Or he would sit me on his lap and wriggle me around, telling me to keep the movements going myself.

When he was performing oral sex on me I would try to disconnect myself from my body, distracting my mind by counting things like the patterns on the wallpaper or the digits on the clock counter on the video. If the television was on I would close my eyes and spell out the things that people were saying and count the letters in my head, anything to keep my mind busy so that I didn’t have to think about what he was doing to me. Sometimes he would shout at me to move my bottom up and down or to pull his hair while he was doing it and masturbating himself.

If my brothers were upstairs in their bedrooms, they knew better than to come out for any reason. God knows how much they heard or understood of the night-time noises outside their closed doors.

Although Richard fought with everyone he came into contact with, bullying everyone, regardless of their age or gender, I don’t think there was anyone else that he degraded sexually in the way that he degraded me. Everyone in the area hated him, though, and they didn’t much like the way my mum carried on either. All day long I would be sent out to knock on doors and cadge cigarettes, teabags, washing powder or anything else that she needed and couldn’t be bothered to go out and buy for herself.

The neighbours must have been able to watch me going from door to door. I bet sometimes they would avoid answering my knock. ‘Oh, Janey,’ they would say in despairing voices when I came back with my fifth request of the day. They all knew they would never be paid back for anything that was borrowed.

Although they spent a fortune doing up their houses, Mum and Richard never had enough money for the essentials of life. Mum would always buy a cheap toilet roll on a Monday when she got her giro cheque, but with seven people in the house it was gone by Tuesday and we would be using torn up newspapers for the rest of the week. I got into the habit of filling my pockets with tissues wherever I came across them. I stole a toilet roll from school once and Mum told me to get more, but I made up some excuse as to why I couldn’t. Every time I went out of the house Mum would say, ‘Try and get some toilet roll.’ I couldn’t understand how she and Richard could afford to smoke and eat McDonald’s, Chinese and curries, but not to buy the basic decencies of life.

Sometimes if Mum had run out of cigarettes and the giro wasn’t due I would have to go out with one of my little brothers and scour the streets for dog-ends, so she could take the tobacco out and make roll ups. I had to keep it a secret from Richard, because he would have gone mad if he’d known we were showing ourselves up like that. I was so ashamed I would tell my friends we were looking for stones, but they knew perfectly well what we were doing. They were always very kind to me. I think they felt sorry for me, having to live with Richard.

Everyone was meant to believe that Richard didn’t work, which he didn’t for years. Then he started doing shifts as a mini-cab driver, but didn’t want to give up the disability benefit he received for his ‘bad leg’, so the work had to be kept quiet. He would unscrew the aerial from the roof of the car whenever he came home and cover up the two-way radio. He would even use a walking stick sometimes, particularly if he’d noticed a new car in the street and thought social services were spying on him. If they had spied on him they would have been able to see him building sheds, laying patios and doing up houses with no trouble at all, not to mention beating people up when they annoyed him.

We were always under strict instructions to lie to anyone who asked about him and to act as if he were really poorly. My friends would always tell me that everyone knew what he was up to, but no one wanted to accuse him to his face.

He even went to the trouble of having handrails fitted in the bathroom so that he could claim a higher level of welfare payment. ‘I hate having those fucking ugly things in my house,’ he would complain, but he was happy to do anything that would bring in a bit more easy money.

I would have to make plenty of trips to the shops as well as to neighbours’ houses during the average day, always sent on the spur of the moment and my journey timed to make sure I didn’t take any detours and meet up with a friend or play with the other kids who messed about in the car park which was a couple of doors away. Sometimes, however, things would go wrong. One day, for instance, when I was still small, I was sent to get Richard some cigarettes and a few other things.

‘Don’t be long,’ he warned, and I could see he was in a bad mood.

I hurried down the road and got to the shop in record time, but the people behind the counter wouldn’t sell me cigarettes and so I knew I was going to have to stand outside as usual asking other customers to buy them for me. That could sometimes take ages, as most people would refuse. This particular day it took what seemed like hours and I was becoming increasingly agitated. If I went back without them I would be in trouble, but if I took too long Richard would think I’d gone to play with a friend, disobeying his orders. It looked as if there was going to be no way out of getting a smack at the very least.

Eventually a man came along who lived opposite us and I begged him to help me, promising that I was buying the cigarettes for my parents. He seemed to believe me, got the cigarettes for me and then asked if I wanted a lift home. We’d been told never to accept lifts from strange men, but I often played with this man’s daughters and knew his wife. There didn’t seem to be any danger and I was eager to get back as quickly as possible in the hope of avoiding a punishment, so I accepted his offer, assuming he would park in the car park round the corner and my stepfather wouldn’t see me getting out of the car. To my horror, however, the neighbour, presumably thinking he was doing me a favour, dropped me off right outside the house. As I came in through the front door Richard went berserk, shouting and screaming, hitting me around the head and kicking me.

‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry,’ I kept saying over and over again, but I couldn’t make him stop.

‘Stand against the backroom window,’ he ordered, ‘and put your arms down by your sides.’

There was no one else in the house to intervene. I did as he told me, terrified of what new torture he might have thought up but equally terrified of moving and angering him still further. So when he pulled back his fist I didn’t flinch, taking the punch full in the face.

‘You deserve that,’ he shouted, finally happy that he had taught me a lesson. ‘Never get in anyone’s car again.’

As the boys grew older my duties towards them increased. I didn’t mind that too much because I loved them when they were little and they were very affectionate back. The younger ones used to call me ‘Mum’ a lot of the time, which would make me laugh. I liked it when they did that; it made me feel they were grateful for what I did for them.

Richard kept wanting more children because he was trying to have a girl of his own. Even when Mum got ill and lost a kidney, he insisted that they went on trying.

Mum and Richard would stay in bed in the mornings once I was able to get the others up and sort out their breakfasts. I was always turning up at school with safety pins all over my clothes from changing nappies.

If the boys woke up early they would come into my room. All of us were terrified of making a noise and disturbing the sleeping adults. To entertain them and keep them quiet until it was time for breakfast I would sit them in a line and dress them up in my clothes, doing their hair as if they were my dolls. They loved it, but when Richard found out he went mad, saying I was trying to turn them into ‘poofs’.

If Mum got up, Silly Git would stay in bed and I would be sent up to give him cups of tea. On each trip I would have to do him some horrible little ‘favour’. He would make me come right up to the edge of the bed, lifting up my skirt and tugging my knickers down so that he could touch me. I would then have to play with him under the covers for a few minutes until Mum called me back downstairs again.

‘Bring me up a fag,’ he would say as I went out the door, and the same thing would happen again when I returned. He always insisted on having two cups of tea before he got up, both brought to him by me.

As the years went by we all used to confide in one another how much we hated Richard, but never when he was in earshot. Mum used to tell us how she was just waiting until the boys had finished school and then we would all be off. Sometimes, when he had given her a beating, she would tell me that once the boys were grown up they would all turn on him for her.

On a few occasions Mum did pluck up the courage to leave him, with all of us walking along behind her like a parade of baby ducks. But he always did whatever was necessary to drag her back, regardless of who might be watching.

On one occasion he was driving his car when he came for her, winding the window down and driving slowly along beside her as she looked straight ahead and pretended not to see him.

‘Get in the fucking car!’ he ordered.

‘Fuck off!’ she replied.

Without another word he reached out of the window and grabbed her hair, then reversed the car back up to the house, literally dragging her back by the hair, not caring about the danger or who might see.

Sometimes he would playact being pathetic and unable to remember whether he had taken his tablets. He took them for the pains in his legs, something to do with trapped nerves, although no one ever really got to the bottom of it. He used to go to pain clinic and I had to go with him once to learn how to give him acupuncture, sticking needles in his back. Richard knew I was too frightened to be tempted to do him any damage with the needles.

Being in pain often made him moody.

‘Have I taken my tablets?’ he would whine.

‘No,’ one of us would lie, ‘I don’t think you have.’

‘You give them to him,’ Mum would whisper to me if we were in another room. ‘Maybe they’ll finish him off.’