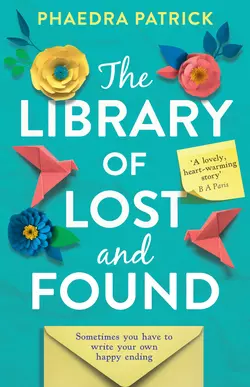

The Library of Lost and Found

Phaedra Patrick

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 920.59 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A librarian’s discovery of a mysterious book sparks the journey of a lifetime in the delightful new novel from the bestselling author of The Curious Charms of Arthur Pepper.Librarian Martha Storm has always found it easier to connect with books than people—though not for lack of trying. She keeps careful lists of how to help others in her superhero-themed notebook. And yet, sometimes it feels like she’s invisible.All of that changes when a book of fairy tales arrives on her doorstep. Inside, Martha finds a dedication written to her by her best friend—her grandmother Zelda—who died under mysterious circumstances years earlier. When Martha discovers a clue within the book that her grandmother may still be alive, she becomes determined to discover the truth. As she delves deeper into Zelda’s past, she unwittingly reveals a family secret that will change her life forever.Filled with Phaedra Patrick’s signature charm and vivid characters, The Library of Lost and Found is a heart-warming and poignant tale of one woman’s journey of self-discovery.