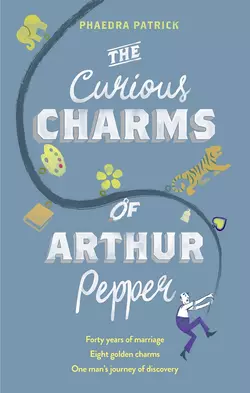

The Curious Charms Of Arthur Pepper

Phaedra Patrick

69 year old Yorkshire widower Arthur Pepper gets up every day at 7.30am.He eats his breakfast, waters his plant, Frederica, and does not speak to anyone unless it is absolutely necessary. Until something happens to disrupt his routine.On the first anniversary of his beloved wife Miriam’s death, Arthur steels himself to tackle the task he’s been dreading: clearing out her wardrobe. There, hidden in a shoebox, he finds a glistening gold charm bracelet that he has never seen before. Upon examination Arthur finds a telephone number on the underside of a gold elephant charm. Uncharacteristically he picks up the phone.And so begins Arthur’s quest – charm by charm, from York to Paris and London and even India – as he seeks to uncover Miriam’s secret life before they were married. And along the way, find out more about himself.

PHAEDRA PATRICK has worked as a stained glass artist, film festival organiser and communications manager. She lives in Saddleworth with her husband and son. The Curious Charms of Arthur Pepper is her debut novel.

ISBN: 978-1-474-03792-1

THE CURIOUS CHARMS OF ARTHUR PEPPER

© 2016 Phaedra Patrick

Published in Great Britain 2016

by HQ, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition is published by arrangement with Harlequin Books S.A.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, locations and incidents are purely fictional and bear no relationship to any real life individuals, living or dead, or to any actual places, business establishments, locations, events or incidents. Any resemblance is entirely coincidental.

By payment of the required fees, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right and licence to download and install this e-book on your personal computer, tablet computer, smart phone or other electronic reading device only (each a “Licensed Device”) and to access, display and read the text of this e-book on-screen on your Licensed Device. Except to the extent any of these acts shall be permitted pursuant to any mandatory provision of applicable law but no further, no part of this e-book or its text or images may be reproduced, transmitted, distributed, translated, converted or adapted for use on another file format, communicated to the public, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of publisher.

Version: 2018-10-26

For Oliver

Acknowledgements (#ulink_b4d119f1-3e6d-5bac-bd08-b35805cbc007)

Firstly, hats off to Super-Agent Clare Wallace for her insight, expertise and all round loveliness. Also, to all at Darley Anderson for their warm welcome and support – especially Mary Darby, Emma Winter and Darley himself. Thanks also to Vicki Le Feuvre for early feedback.

Behind every book is a great editor and I am fortunate to have two of the best in my corner. To my UK editor Sally Williamson and to Erika Imranyi in the US, many thanks for your thoughtfulness, creativity and championing of Arthur. A special acknowledgment also goes to Sammia Hamer, who originally gave Arthur his home in the UK.

All the team at HQ and HarperCollins have been wonderful, with fantastic input from Alison Lindsay, Clio Cornish, Nick Bates and Sara Perkins Bran, to name just a few.

To friends who read an early draft of this book without rolling their eyes, thanks to Mark RF, Joan K, Mary McG and Mags B.

My mum and dad have always encouraged my love of books and reading, so to Pat and Dave – this couldn’t have happened without you!

The biggest shout out goes to Mark and Oliver for supporting me on every step on this journey, believing it was possible and for always being there.

Thanks also to my friend, Ruth Moss, whose bravery and spirit of fun I think of often.

Table of Contents

Cover (#uee9a084b-860d-53dc-a91e-c53d3ff47c22)

About the Author (#u75f0c191-3d70-5321-a3d9-81523c612a41)

Title Page (#ue71c9202-c968-595e-84ef-134905e0a9d3)

Dedication (#uf71dd57e-7d49-5198-9267-eafaf529efb5)

Acknowledgements (#u55d2ee07-4834-5f8f-805c-2e32cec9a5ae)

The Surprise in the Wardrobe (#u0713a55f-ce51-57b3-9de7-ebd5e8e8a00b)

The Elephant (#u9a63c07e-8da0-5f60-91b6-83961bebde5b)

The Great Escape (#u1eca078f-9977-50cf-9d8d-094fa0c4ae74)

On the Way (#ufd6560e4-a99f-58f5-9ba1-ffe7d7fca2f0)

Lucy and the Tortoise (#uf56c4e68-f593-5998-82af-63417c340e0a)

Bed and Breakfast (#u860de4a5-d260-5c11-a377-82d2fac467d5)

The Tiger (#u3f662f62-63e2-549e-a208-aa7ec7cc8b0e)

The Photograph (#litres_trial_promo)

Lucy and Dan (#litres_trial_promo)

Mobile Technology (#litres_trial_promo)

London (#litres_trial_promo)

The Book (#litres_trial_promo)

Lucy the Second (#litres_trial_promo)

Mike’s Apartment (#litres_trial_promo)

The Flower (#litres_trial_promo)

Green Shoots (#litres_trial_promo)

The Thimble (#litres_trial_promo)

Paris Match (#litres_trial_promo)

Bookface (#litres_trial_promo)

The Paint Palette (#litres_trial_promo)

Bernadette (#litres_trial_promo)

The Ring (#litres_trial_promo)

Crappy Birthday (#litres_trial_promo)

Memories (#litres_trial_promo)

The Heart (#litres_trial_promo)

Letters Home (#litres_trial_promo)

Finders Keepers (#litres_trial_promo)

Journey’s End? (#litres_trial_promo)

The Future (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#u112b6903-49f9-51fc-9b05-c576ae64c656)

The Surprise in the Wardrobe (#ulink_5ec5626b-75a8-5f69-bf98-11936effbf7a)

Each day, Arthur got out of bed at precisely 7:30 a.m. just as he did when his wife, Miriam, was alive. He showered and got dressed in the grey slacks, pale blue shirt and mustard tank top that he had laid out the night before. He had a shave then went downstairs.

At eight o’clock he made his breakfast, usually a slice of toast and margarine, and he sat at the pine farmhouse table that could seat six, but which now just seated one. At eight-thirty he would rinse his pots and wipe down the kitchen worktop using the flat of his hand and then two lemon-scented Flash wipes. Then his day could begin.

On an alternative sunny morning in May, he might have felt glad that the sun was already out. He could spend time in the garden plucking up weeds and turning over soil. The sun would warm the back of his neck and kiss his scalp until it was pink and tingly. It would remind him that he was here and alive—still plodding on.

But today, the fifteenth day of the month, was different. It was the anniversary he had been dreading for weeks. The date on his Stunning Scarborough calendar caught his eye whenever he passed it. He would stare at it for a moment then try to find a small job to distract him. He would water his fern, Frederica, or open the kitchen window and shout ‘Gerroff’ to deter next door’s cats from using his rockery as a toilet.

It was one year to the day that his wife had died.

Passed away was the term that everyone liked to use. It was as if saying the word died was swearing. Arthur hated the words passed away. They sounded gentle, like a canal boat chugging through rippling water, or a bubble floating in a cloudless sky. But her death hadn’t been like that.

After over forty years of marriage it was just him in the house now, with its three bedrooms and the en-suite shower room that grown-up daughter, Lucy, and son, Dan, recommended they had fitted with their pension money. The recently installed kitchen was made from real beech and had a cooker with controls like the NASA space centre, and which Arthur never used in case the house lifted off like a rocket.

How he missed the laughter in the home. He longed to hear again the pounding of feet on the stairs, and even doors slamming. He wanted to find stray piles of washing on the landing and trip over muddy wellies in the hallway. Wellibobs the kids used to call them. The quietness of it being just him was more deafening than any family noise he used to grumble about.

Arthur had just cleaned his worktop and was heading for his front room when a loud noise pierced his skull. He instinctively pressed his back against the wall. His fingers spread out against magnolia woodchip. Sweat prickled his underarms. Through the daisy-patterned glass of his front door, he saw a large purple shape looming. He was a prisoner in his own hallway.

The doorbell rang again. It was amazing how loud she could make it sound. Like a fire bell. His shoulders shot up to protect his ears and his heart raced. Just a few more seconds and surely she’d get fed up and leave. But then the letterbox opened.

‘Arthur Pepper. Open up. I know you’re in there.’

It was the third time this week that his neighbour Bernadette had called around. For the past few months she had been trying to feed him up with her pork pies or home-made mince and onion. Sometimes he gave in and opened the door; most of the time he did not.

Last week he had found a sausage roll in his hallway, peeking out of its paper bag like a frightened animal. It had taken him ages to clear up the flakes of pastry from his hessian welcome mat.

He had to hold his nerve. If he moved now she would know he was hiding. Then he’d have to think of an excuse; he was putting out the bins, or watering the geraniums in the garden. But he felt too weary to invent a story, especially today of all days.

‘I know you’re in there, Arthur. You don’t have to do this on your own. You have friends who care about you.’ The letterbox rattled. A small lilac leaflet with the title ‘Bereavement Buddies’ drifted to the floor. It had a badly drawn lily on the front.

Although he hadn’t spoken to anyone for over a week, although all he had in the fridge was a small chunk of cheddar and an out-of-date bottle of milk, he still had his pride. He would not become one of Bernadette Patterson’s lost causes.

‘Arthur.’

He screwed his eyes shut and pretended he was a statue in the garden of a stately home. He and Miriam used to love visiting National Trust properties, but only during the week when there were no crowds. He wished the two of them were there now, their feet crunching on gravel paths, marvelling at cabbage white butterflies fluttering among the roses, looking forward to a big slice of Victoria sponge in the tea room.

A lump rose in his throat as he thought about his wife, but he held his pose. He wished he really could be made of stone so he couldn’t hurt any more.

Finally the letterbox snapped shut. The purple shape moved away. Arthur let his fingers relax first then his elbows. He wriggled his shoulders to relieve the tension.

Not totally convinced that Bernadette wasn’t lurking by the garden gate, he opened his front door an inch. Pressing his eye against the gap, he peered around outside. In the garden opposite, Terry, who wore his hair in dreadlocks tied with a red bandanna and who was forever mowing his lawn, was heaving his mower out of his shed. The two redheaded kids from next door were running up and down the street wearing nothing on their feet. Pigeons had pebble-dashed the windscreen of his disused Micra. Arthur began to feel calmer. Everything was back to normal. Routine was good.

He read the leaflet then placed it carefully with the others that Bernadette had posted for him—‘Friends Indeed’, ‘Thornapple Residents Association’, ‘Men in Caves’ and ‘Diesel Gala Day at North Yorkshire Moors Railway’—then forced himself to go and make a cup of tea.

Bernadette had compromised his morning, thrown him off balance. Flustered, he didn’t allow his tea bag enough time in the pot. Sniffing the milk from the fridge, he winced at the smell and poured it down the sink. He would have to take his tea black. It tasted like iron filings. He gave a deep sigh.

Today, he wasn’t going to mop the kitchen floor or vacuum the stairs carpet so hard that the threadbare bits grew balder. He wasn’t going to polish the bathroom taps and fold the towels into neat squares.

Reaching out, he touched the fat black telescope of bin liners that he’d placed on the kitchen table and reluctantly picked them up. They were heavy. Good for the job.

To make things easier he read through the cat charity leaflet one more time: ‘Cat Saviours. All items donated are sold to raise funds for badly treated cats and kittens.’

He wasn’t a cat lover himself, especially as they had decimated his rockery, but Miriam liked them even though they made her sneeze. She had saved the leaflet under the telephone and Arthur took this as a sign that this was the charity he should give her belongings to.

Purposefully delaying the task that lay ahead, he climbed the stairs slowly and paused on the first landing. By sorting out her wardrobe it felt as if he was saying goodbye to her all over again. He was clearing her out of his life.

With a tear in his eye, he looked out of the window onto the back garden. If he stood on tiptoe he could just see the tip of York Minster, its stone fingers seeming to prop up the sky. Thornapple village, in which he lived, was just on the outskirts of the city. Cherry blossom had already started to fall from the trees, swirling like pink confetti. The garden was surrounded on three sides by a tall wooden fence that gave privacy; too tall for neighbours to pop their heads over for a chat. He and Miriam liked their own company. They did everything together and that was how they liked it, thank you very much.

There were four raised beds, which he had made out of railway sleepers and which housed rows of beetroots, carrots, onions and potatoes. This year he might even attempt pumpkins. Miriam used to make a grand chicken and vegetable stew with the produce, and home-made soups. But he wasn’t a cook. The beautiful red onions he picked last summer had stayed on the kitchen worktop until their skins were as wrinkly as his own and he had thrown them in the recycling bin.

He finally ascended the remainder of the stairs and arrived panting outside the bathroom. He used to be able to speed from top to bottom, running after Lucy and Dan, without any problem. But now, everything was slowing down. His knees creaked and he was sure he was shrivelling. His once-black hair was now dove white (though still so thick it was difficult to keep flat) and the rounded tip of his nose seemed to be growing redder by the day. It was difficult to remember when he stopped being young and became an old man.

He recalled his daughter Lucy’s words when they last spoke, a few weeks ago. ‘You could do with a clear out, Dad. You’ll feel better when Mum’s stuff is gone. You’ll be able to move on.’ Dan occasionally phoned from Australia, where he now lived with his wife and two children. He was less tactful. ‘Just chuck it all out. Don’t turn the house into a museum.’

Move on? Like to bloody where? He was sixty-nine, not a teenager who could go to university or on a gap year. Move on. He sighed as he shuffled into the bedroom.

Slowly he pulled open the mirrored doors on the wardrobe.

Brown, black and grey. He was confronted by a row of clothes the colour of soil. Funny, he didn’t remember Miriam dressing so dully. He had a sudden image of her in his head. She was young and swinging Dan around by an arm and leg—an aeroplane. She was wearing a blue polka dot sundress and white scarf. Her head was tipped back and she was laughing, her mouth inviting him to join in. But the picture vanished as quickly as it came. His last memories of her were the same colour as the clothes in the wardrobe. Grey. She had aluminium-hued hair in the shape of a swimming cap. She had withered away like the onions.

She’d been ill for a few weeks. First it was a chest infection, an annual affliction which saw her laid up in bed for a fortnight on a dose of antibiotics. But this time the infection turned into pneumonia. The doctor prescribed more bed rest and his wife, never one to cause a fuss, had complied.

Arthur had discovered her in bed, staring, lifeless. At first he thought she was watching the birds in the trees, but when he shook her arm she didn’t wake up.

Half her wardrobe was devoted to cardigans. They hung shapeless, their arms dangling as if they’d been worn by gorillas, then hung back up again. Then there were Miriam’s skirts; navy, grey, beige, mid-calf length. He could smell her perfume, something with roses and lily of the valley, and it made him want to nestle his nose into the nape of her neck, just one more time please, God. He often wished this was all a bad dream and that she was sat downstairs doing the Woman’s Weekly crossword, or writing a letter to one of the friends they had met on their holidays.

He allowed himself to sit on the bed and wallow in self-pity for a few minutes and then swiftly unrolled two bags and shook them open. He had to do this. There was a bag for charity and one for stuff to throw out. He took out armfuls of clothes and bundled them in the charity bag. Miriam’s slippers—worn and with a hole in the toe—went in the rubbish bag. He worked quickly and silently, not stopping to let emotion get in the way. Halfway through the task and a pair of old grey lace-ups went in the charity bag, followed by an almost identical pair. He pulled out a large shoe box and lifted out a pair of sensible fur-lined brown suede boots.

Remembering one of Bernadette’s stories about a pair of boots she’d bought from a flea market and found a lottery ticket (non-winning) inside, he automatically slid his hand inside one boot (empty) and then the other. He was surprised when his fingertips hit something hard. Strange. Wriggling his fingers around the thing, he tugged it out.

He found himself holding a heart-shaped box. It was covered in textured scarlet leather and fastened with a tiny gold padlock. There was something about the colour that made him feel on edge. It looked expensive, frivolous. A present from Lucy, perhaps? No, surely he would have remembered it. And he would never have bought something like this for his wife. She liked simple or useful things, like plain round silver stud earrings or pretty oven gloves. They had struggled with money all their married life, scrimping and squirrelling funds away for a rainy day. When they had eventually splashed out on the kitchen and bathroom, she had only enjoyed them for a short while. No, she wouldn’t have bought this box.

He examined the keyhole in the tiny padlock. Then he rummaged around in the bottom of the wardrobe pushing the rest of Miriam’s shoes around, mixing up the pairs. But he couldn’t find the key. He picked up a pair of nail scissors and jiggled them around in the keyhole, but the lock remained defiantly closed. Curiosity pricked inside him. Not wanting to admit defeat, he went back downstairs. Nearly fifty years as a locksmith and he couldn’t bloody get into a heart-shaped box. From the kitchen bottom drawer he took out the two-litre plastic ice cream carton that he used as a tool box; his box of tricks.

Back upstairs, he sat on the bed and took out a hoop full of lock picks. Inserting the smallest one into the keyhole, he gave it a small wriggle. This time there was a click and the box opened by a tantalising few millimetres, like a mouth about to whisper a secret. He unhooked the padlock and lifted the lid.

The box was lined with black crushed velvet. It sang of decadence and wealth. But it was the charm bracelet that lay inside that caused him to catch his breath. It was opulent and gold with chunky round links and a heart-shaped fastener. Another heart.

What was more peculiar was the array of charms, spread out from the bracelet like sun rays in a children’s book illustration. There were eight in total: an elephant, a flower, a book, a paint palette, a tiger, a thimble, a heart and a ring.

He took the bracelet out of the box. It was heavy and jangled when he moved it around in his hand. It looked antique, or had age to it, and was finely crafted. The detail on each charm was sharp. But as hard as he tried he couldn’t remember Miriam wearing the bracelet or showing any of the charms to him. Perhaps she had bought it as a present for someone else. But for whom? It looked expensive. When Lucy wore jewellery it was new-fangled stuff with curls of silver wire and bits of glass and shell.

He thought for a moment about phoning his children to see if they knew anything about a charm bracelet hidden in their mother’s wardrobe. It seemed a valid reason to make contact. But then he told himself to reconsider as they’d be too busy to bother with him. It had been a while since he had phoned Lucy with the excuse of asking how the cooker worked. With Dan, it had been two months since his son had last been in touch. He couldn’t believe that Dan was now forty and Lucy was thirty-six. Where had time gone?

They had their own lives now. Where once Miriam was their sun and he their moon, Dan and Lucy were now distant stars in their own galaxies.

The bracelet wouldn’t be from Dan anyway. Definitely not. Each year before Miriam’s birthday, Arthur phoned his son to remind him of the date. Dan would insist that he hadn’t forgotten, that he was about to go to the post box that day and post a little something. And it usually was a little something: a fridge magnet in the shape of the Sydney Opera House, a photo of the grandkids, Kyle and Marina, in a cardboard frame, a small koala bear with huggy arms that Miriam clipped to the curtain in Dan’s old bedroom.

If she was disappointed with the gifts from her son then Miriam never showed it. ‘How lovely,’ she would exclaim, as if it was the best present she had ever received. Arthur wished that she could be honest, just once, and say that their son should make more effort. But then, even as a boy, he had never been aware of other people and their feelings. He was never happier than when he was dismantling car engines and covered in oil. Arthur was proud that his son owned three car body repair workshops in Sydney, but wished that he could treat people with as much attention as he paid his carburettors.

Lucy was more thoughtful. She sent thank you cards and never, ever forgot a birthday. She had been a quiet child to the point where Arthur and Miriam wondered if she had speech difficulties. But no, a doctor explained that she was just sensitive. She felt things more deeply than other people did. She liked to think a lot and explore her emotions. Arthur told himself that’s why she hadn’t attended her own mother’s funeral. Dan’s reason was that he was thousands of miles away. But although Arthur found excuses for them both, it hurt him more than they could ever imagine that his children hadn’t been there to say goodbye to Miriam properly. And that’s why, when he spoke to them sporadically on the phone, it felt like there was a dam between them. Not only had he lost his wife, but he was losing his children, too.

He squeezed his fingers into a triangle but the bracelet wouldn’t slip over his knuckles. He liked the elephant best. It had an upturned trunk and small ears; an Indian elephant. He gave a wry smile at its exoticness. He and Miriam had discussed going abroad for a holiday but then always settled upon Bridlington, at the same bed-and-breakfast on the seafront. If they ever bought a souvenir, it was a packet of tear-off postcards or a new tea towel, not a gold charm.

On the elephant’s back was a howdah with a canopy, and inside that nestled a dark green faceted stone. It turned as he fingered it. An emerald? No, of course not, just glass or a pretend precious stone. He ran his finger along the trunk, then felt the elephant’s rounded hind before settling on its tiny tail. In places the metal was smooth, in others it felt indented. The closer he looked though, the more blurred the charm became. He needed glasses for reading but could never find the things. He must have five pairs stashed in safe places around the house. He picked up his box of tricks and took out his eyeglass: every year or so it came in handy. After scrunching it into his eye socket, he peered at the elephant. As he moved his head closer then further away to get the right focus, he saw that the indentations were in fact tiny engraved letters and numbers. He read and then read again.

Ayah. 0091 832 221 897

His heart began to beat faster. Ayah. What could that mean? And the numbers too. Were they a map reference, a code? He took a small pencil and pad from his box and wrote them down. His eyeglass dropped onto the bed. He’d watched a quiz programme on TV just last night. The wild-haired presenter had asked the dialling code for making calls from the UK to India—0091 was the answer.

Arthur fastened the lid back onto the ice cream box and carried the charm bracelet downstairs. There, he looked in his Oxford English Pocket Dictionary; the definition of the word ‘ayah’ didn’t make any sense to him—a nursemaid or maid in East Asia or India.

He didn’t usually phone anyone on a whim; he preferred not to use the phone at all. Calls to Dan and Lucy only brought disappointment. But, even so, he picked up the receiver.

He sat on the one chair he always used at the kitchen table and carefully dialled the number, just to see. This was just silly, but there was something about the curious little elephant that made him want to know more.

It took a long time for the dialling tone to kick in and even longer for someone to answer the call.

‘Mehra residence. How may I help you?’

The polite lady had an Indian accent. She sounded very young. Arthur’s voice wavered when he spoke. Wasn’t this preposterous? ‘I’m phoning about my wife,’ he said. ‘Her name was Miriam Pepper, well it was Miriam Kempster before we married. I’ve found an elephant charm with this number on it. It was in her wardrobe. I was clearing it out …’ He trailed off, wondering what on earth he was doing, what he was saying.

The lady was quiet for a moment. He was sure she was about to hang up or tell him off for making a crank call. But then she spoke. ‘Yes. I have heard stories of Miss Miriam Kempster. I’ll just find Mr Mehra for you now, sir. He will almost certainly be able to assist you.’

Arthur’s mouth fell open.

The Elephant (#ulink_c619c091-47b7-5486-b98e-d1e816af9df0)

Arthur gripped the receiver tightly. A voice in his head told him to put it down, to forget about this. Firstly, there was the cost. He was on the phone to India. That couldn’t be cheap. Miriam was always so careful about the phone bill, especially with the cost of phoning Dan in Australia.

And then there was the gnawing feeling that he was prying on his wife. Trust had always formed a great part in their marriage. When he travelled around the country selling locks and safes, Miriam had voiced her concerns that on overnight stays he might succumb to the charms of a comely landlady. He had assured her that he would never do anything to jeopardise his marriage or family life. Besides, he wasn’t the type that women would find attractive. An ex-girlfriend had compared him to a mole. She said that he was timid and a bit twitchy. But, surprisingly, he had been propositioned a few times. Though it was probably because of the loneliness or opportunism of the ladies (and once a man), rather than his own appeal.

Sometimes his working days had been long. He travelled around the country a lot. He especially enjoyed showing off new mortice locks, explaining the latches, snibs and levers to his clients. There was something about locks that intrigued him. They were solid and reliable. They protected you and kept you safe. He loved how his car always smelled of oil and he enjoyed chatting to his customers in their shops. But then along came the internet and online ordering. Locksmiths didn’t need salesmen any longer. The shops that remained open started to order their stock by computer and Arthur found himself confined to a desk job. He used the phone to talk to his clients rather than talking face-to-face. He had never liked the phone. You couldn’t see people smiling or their eyes when they asked questions.

It was hard being away from the kids too, sometimes getting home when they were already in bed. Lucy understood, delighted to see him the next morning. She would fling her arms around his neck and tell him she missed him. Dan was trickier. On the rare occasion that Arthur finished work early, Dan seemed to resent it. ‘I like my time with Mum better,’ he once said. Miriam told Arthur not to take it to heart. Some kids were closer to one parent than the other. It didn’t stop Arthur from feeling guilty about working so hard to provide for his family.

Miriam had vowed that she would always be faithful, no matter what hours he worked, and he trusted that she had been. She never gave him cause to think otherwise. He never saw her flirt with other men or found any evidence that she might ever have strayed. Not that he was looking for it. But sometimes when he got home after working away, he wondered if she’d had company. It must have been hard being alone with the two kids. Not that she ever complained. She was a real trouper was Miriam.

Swallowing a lump that formed in his throat as he thought about his family, he began to move his ear away from the receiver. His hand trembled. Best just to leave this be. Hang up. But then he heard a tinny voice calling out to him. ‘Hello. Mr Mehra speaking. I understand that you are phoning about Miriam Kempster, yes?’

Arthur swallowed. His mouth had gone dry. ‘Yes, that’s right. My name is Arthur Pepper. Miriam is my wife.’ It felt wrong to say that Miriam was my wife, because although she was no longer here they were still married, weren’t they?

He explained how he’d found a charm bracelet and the elephant charm with the engraved number. He had not expected anyone to answer his call. Then he told Mr Mehra that his wife was now dead.

Mr Mehra fell silent. It was over a minute before he spoke again. ‘Oh, my dear sir. I am so sorry. She looked after me so well when I was a boy. But that was many years ago now. I still live in the same house! There is little movement in our family. We have the same phone number. I am a doctor and my father and grandfather were doctors before me. I have never forgotten Miriam’s kindness. I hoped that one day I might find her again. I should have tried harder.’

‘She looked after you?’

‘Yes. She was my ayah. She looked after me and my younger sisters.’

‘Your childminder? Here in England?’

‘No, sir. In India. I live in Goa.’

Arthur couldn’t speak. His mind went numb. He knew nothing of this. Miriam had never mentioned living in India. How could this be? He stared at the pot pourri stuffed leaf in the hallway twirling and hanging by a thread.

‘May I tell you a little about her, sir?’

‘Yes. Please do,’ he murmured. Anything to fill in some gaps, tell him that this must be some other Miriam Kempster they were talking about.

Mr Mehra’s voice was soothing and authoritative. Arthur didn’t think about his phone bill. More than anything he wanted to hear from someone else who might have known and loved Miriam, even if this man was a stranger to him. Sometimes not talking about her made it feel like her memory was fading away.

‘We had many ayahs before Miriam joined us. I was a naughty child. I played tricks on them. I put newts in their shoes and chilli flakes in their soup. They didn’t last long. But Miriam was different. She ate the hot food and didn’t say a word. She picked the newts out of her shoes and put them back in the garden. I studied her face but she was a fine actress. She never gave anything away and I didn’t know if she was annoyed with me, or amused. Slowly I gave up teasing her. There was no point. She knew all my tricks! I remember that she had a bag of wonderful marbles. They were as shiny as the moon and one was like a real tiger’s eye. She didn’t care if she kneeled in the dust.’ He gave a throaty laugh. ‘I was a little in love with her.’

‘How long did she stay with your family?’

‘For a few months, in India. I was very broken-hearted when she left. It was my entire fault. That is something I have never told anyone before. But you, Mr Pepper, deserve to know. It is a shame I have carried with me for all these years.’

Arthur shifted nervously in his seat.

‘Do you mind if I tell you? It would mean a great deal to me. It is like a secret burning a hole in my stomach.’ Mr Mehra didn’t wait for a response before he carried on his story. ‘I was only eleven but I loved Miriam. It was the first time I had noticed a girl. She was so pretty and always wore such classy clothes. Her laughter, well, it sounded like tiny bells. When I woke up in the morning she was the first thing I thought about and when I went to bed I looked forward to the next day. I know now that this was not true love like when I met my wife, Priya, but for a young boy it was very real. She was very different to the girls I went to school with. She was exotic, with her alabaster skin and hair the colour of walnuts. Her eyes were like aquamarines. I probably followed her around a little too much, but she never made me feel foolish. My mother had died when I was very young and I used to ask Miriam to sit with me in her room. We would look through my mother’s jewellery box together. She loved the elephant charm. We used to look through the emerald and see the world in green.’

So, it is a real emerald, Arthur thought.

‘But then Miriam began to go out on her own twice a week. We spent a little less time together. I was old enough not to need an ayah but my two sisters did. She was there for them but not so much for me. I followed her one day and she met with a man. He was a teacher at my school. An English man. He came around to the house and he and Miriam took afternoon tea. I saw that he liked her. He picked a hibiscus flower from the garden to give to her.

‘Mr Pepper. I was a young boy. I was growing and had hormones roaring around my body. I felt very angry. I told my father that I had seen Miriam and the man kissing. My father was a very old-fashioned man and he had already lost one ayah because of similar circumstances. So there and then he went to find Miriam and told her to leave. She was so surprised but she acted with dignity and packed her suitcase.

‘I was devastated. I had not meant this to happen. I took the elephant from the jewellery box and ran to the village to have it engraved. I pushed it into the front pocket of her suitcase as it stood by the door. I was too much of a coward to say goodbye, but she found me hiding and gave me a kiss. She said, “Goodbye, dearest Rajesh.” And I never saw her again.

‘From that day, Mr Pepper, I swear I have tried never to tell a lie. I only tell the truth. It is the only way. I prayed that she could forgive me. Did she say that to you?’

Arthur knew nothing about this part of his wife’s life. But he knew this was the same woman that they had both loved. Miriam’s laughter did sound like tiny bells. She did have a bag of marbles, which she gave to Dan. He was still reeling from astonishment, but he could hear the longing in Mr Mehra’s voice. He cleared his throat. ‘Yes, she forgave you long ago. She spoke of you kindly.’

Mr Mehra laughed out loud. A short ‘Ha ha!’ Then he said, ‘Mr Pepper! You have no idea how happy your words make me feel. For years this has felt like a huge weight for me. Thank you for taking the trouble to ring me. I am so sorry to hear that Miriam is no longer with you.’

Arthur felt a glow in his stomach. It was something that he hadn’t felt for a long time. He felt useful.

‘You were a lucky man to be married for so long, yes? To have a wife such as Miriam. Did she have a happy life, sir?’

‘Yes. Yes, I think she did. It was a quiet life. We have two lovely children.’

‘Then you must try to be happy. Would she want you to be sad?’

‘No. But it’s hard not to be.’

‘I know this. But there is much to celebrate about her.’

‘Yes.’

Both men fell silent.

Arthur turned the bracelet around in his hand. He now knew about the elephant. But what about the other charms? If he didn’t know about Miriam’s life in India, what stories did the other charms hold? He asked Mr Mehra if he knew anything about the bracelet.

‘I only gave her the elephant. She did write to me once, a few months after she left, to say thank you. I’m a sentimental fool and I still have the letter. I always told myself that I would get in touch, but I felt too ashamed about my lie. I can see what address is on the letter if you like?’

Arthur swallowed. ‘That would be most kind.’

He waited for five minutes until Mr Mehra returned to the call. He reached out to stop the pot pourri leaf from twirling. He flicked through the leaflets Bernadette had posted through the door.

‘Ah, yes, here it is—Graystock Manor in Bath, England, 1963. I hope this helps with your search. She talks in the letter about staying with friends there. There’s something about tigers in the grounds.’

‘There is a tiger charm on the bracelet,’ Arthur said.

‘Aha. Then that might be your next port of call. You will find out the stories of the charms one by one, yes?’

‘Oh, this isn’t a search,’ Arthur started. ‘I was just curious …’

‘Well, if you are ever in India, Mr Pepper, you must look me up. I will show you the places that Miriam loved. And her old room. It hasn’t changed much over the years. You would like to see it?’

‘That’s very decent of you. Though I’m afraid I’ve never left the UK before. I can’t see myself travelling to India any time soon.’

‘There is always a first time, Mr Pepper. You bear my offer in mind, sir.’

Arthur said goodbye and thank you for the invitation. As he placed the receiver down, Mr Mehra’s words rolled over and over in his head: . . next port of call … finding out the stories of the charms one by one …

And he began to wonder.

The Great Escape (#ulink_1788c477-7abb-524c-b506-cd523d611973)

It was still dark the next morning when Arthur woke. The digits on his alarm clock flicked to 5:32 a.m. and he lay for a while staring at the ceiling. Outside a car drove past and he watched the reflection of the headlights sweep over the ceiling like the rays of a lighthouse across water. He let his fingers creep across the mattress, reaching out for Miriam’s hand knowing it wasn’t there and feeling only cool cotton sheet.

Each night, when he went to bed, it struck him how chilly it was without her. When she was next to him he always slept through the night, gently drifting off, then waking to the sound of thrushes singing outside. She would shake her head and ask did he not hear the thunderstorm or next door’s house alarm going off? But he never did.

Now his sleep was fitful, restless. He woke up often, shivering and wrapping the duvet around him in a cocoon. He should put an extra blanket on the bed, to stop the cold from creeping around his back and numbing his feet. His body had found its own strange rhythm of sleeping, waking, shivering, sleeping, waking, shivering, which, although uncomfortable, he didn’t want to shake. He didn’t want to drop off and then wake with the birds and find that Miriam was no longer there. Even now that would be too much of a shock. Stirring through the night reminded him that she had gone and he welcomed those constant reminders. He didn’t want to risk forgetting her.

If he had to describe in one word how he felt this morning, it would be perplexed. Getting rid of Miriam’s clothes was going to be a ritual, freeing the house of her things, her shoes, her toiletries. It was a small step in coping with his loss and moving on.

But the newly-discovered charm bracelet was an obstacle to his intentions. It raised questions where once there were none. It had opened a door and he had stepped through it.

He and Miriam differed in how they saw mysteries. They regularly enjoyed a Miss Marple or a Hercule Poirot on a Sunday afternoon. Arthur would watch intently. ‘Do you think it’s him?’ he would say. ‘He’s being very helpful and his character adds nothing to the story. I think he might be the killer.’

‘Watch the film.’ Miriam would squeeze his knee. ‘Just enjoy it. You don’t have to psychoanalyse all the characters. You don’t have to guess the ending.’

‘But, it’s a mystery. It’s supposed to make you guess. We’re supposed to try and work it out.’

Miriam would laugh and shake her head.

If this were the other way round and (he hated to think this) he had died, Miriam might not have given finding a strange object in Arthur’s wardrobe much thought. Whereas here he was, his brain whirring like a child’s windmill in the garden.

He creaked out of bed and took a shower, letting the hot water bounce off his face. Then he dried himself off, had a shave, put on his grey trousers, blue shirt and mustard tank top and headed downstairs. Miriam liked it when he wore these clothes. She said they made him look presentable.

For the first weeks after she died, he couldn’t even be bothered getting dressed. Who was there to make an effort for? With his wife and children gone, why should he care? He wore his pyjamas day and night. For the first time in his life he grew a beard. When he saw himself in the bathroom mirror he was surprised at his resemblance to Captain Birdseye. He shaved it off.

He left radios on in each room so he wouldn’t have to hear his own footsteps. He survived on yoghurts and cans of soup, which he didn’t bother to heat. A spoon and a can opener were all he needed. He found himself small jobs to do: tightening the bolts on the bed to stop it squeaking, scratching out the blackened grout around the bath.

Miriam kept a fern on the windowsill in the kitchen. It was a moth-eaten thing with drooping feathery leaves. He despised it at first, resenting how such a pathetic thing could live when his wife had died. It had sat on the floor by the back door waiting for bin day. But, out of guilt, he relented and set it back in its place. He named it Frederica and began to water and talk to it. And slowly she perked up. She no longer drooped. Her leaves grew greener. It felt good to nurture something. He found it easier to chat to the plant than to people. It was good for him to keep busy. It meant he didn’t have time to be sad.

Well, that’s what he told himself, anyway. But then he’d be going about his daily tasks, kind of doing okay, holding it together. Then he’d spy the green pot pourri fabric leaf hanging in the hallway or Miriam’s mud-encrusted walking shoes in the pantry, or the lavender Crabtree & Evelyn hand cream on the shelf in the bathroom—and it would feel like a landslide. Such small meaningless items now tore at his heart.

He would sit on the bottom step of the stairs and hold his head in his hands. Rocking backward and forward, squeezing his eyes shut, he told himself that he was bound to feel like this. His grief was still raw. It would pass. She was in a better place. She wouldn’t want him to be like this. Blah blah. All the usual mumbo-jumbo from Bernadette’s leaflets. And it did pass. But it never vanished completely. He carried his loss around with him like a bowling ball in the pit of his stomach.

At these times he imagined his own father, stern, strong: ‘Bloody ‘ell. Pull yerself together, lad. Crying’s for sissies,’ and he would lift his chin and try to be brave.

Perhaps he should be getting over it by now.

His recollections of those dark early days were foggy. What he did recall was like seeing it on a black-and-white TV set with a crackly picture. He saw himself shuffling around the house.

If he was honest, then Bernadette had been a great help.

She had turned up on his doorstep like an unwelcome genie and insisted that he bathed while she cooked lunch. Arthur hadn’t wanted to eat. Food held no taste or pleasure for him.

‘Your body is like a steam train that needs coal,’ Bernadette said as he protested against the pies, soups and stews she carried over his threshold, heated and then placed in front of him. ‘How are you going to carry on your journey without fuel?’

Arthur wasn’t planning any journey. He didn’t want to leave the house. The only trip he made was upstairs to use the bathroom or go to bed. He had no desire to do anything more than that. For a quiet life he ate her food, blocked out her chatter, read her leaflets. He really would prefer to be left alone.

But she persisted. Sometimes he answered the door to her, other times he wriggled down in the bed and pulled the blankets over his head or thrust himself into National Trust statue mode. But she never gave up on him.

Later that morning, as if she knew he was thinking of her, Bernadette rang his doorbell. Arthur stood in the dining room, still for a few moments, wondering whether to go to the door. The air smelled of bacon and eggs and fresh toast as the other residents of Bank Avenue enjoyed their breakfasts. The doorbell rang again.

‘Her husband Carl died recently,’ Miriam had told him, a few years ago, as she spied Bernadette on a stall at a local church fete, selling butterfly buns and chocolate cake. ‘I think that bereaved people act in one of two ways. There are those who cling with their fingertips to the past, and those who brush their hands together and get on with their lives. That lady with the red hair is the latter. She keeps herself busy.’

‘Do you know her?’

‘She works at LadyBLovely, the boutique in the village. I bought a navy dress from there. It has tiny pearl buttons. She told me that, in her husband’s memory, she was going to help others through her baking. She said that if people are tired, lonely, heartbroken, or have simply run out of steam, then they need food. I think it’s very courageous of her to make it her mission to help others.’

From then on Arthur noticed Bernadette more—at the local school summer fair, in the post office, in her dressing gown tending roses in her garden. They said hello to each other and not much else. Sometimes he saw Bernadette and Miriam chatting on the street corner. They would laugh and talk about the weather and how strawberries were sweet this year. Bernadette’s voice was so loud that he could hear the conversation from inside the house.

Bernadette had attended Miriam’s funeral. He had a hazy memory of her appearing beside him and patting his arm. ‘If you ever need anything, just ask,’ she said and Arthur wondered what he might possibly ever ask her for. Then she had started to turn up announced on his doorstep.

At first he felt irritated by her presence, then he began to worry that she had set her sights on him, perhaps as a potential second husband. He wasn’t looking for anything like that. He never could do after Miriam. But in all the months she had been knocking on his door, Bernadette hadn’t ever given him cause to think her attention was anything more than platonic. She had a full roster of widows and widowers to call upon.

‘Mince and onion pie,’ she greeted him as he opened up. ‘Freshly made.’ She let herself into the hallway, pie-first. There, she ran her finger along the shelf over the radiator and nodded with satisfaction that it was dust free. She sniffed the air. ‘It’s a bit musty in here. Do you have air freshener?’

Arthur marvelled at how impolite she could be without realising and dutifully fetched one. A few seconds later and the cloying smell of Mountain Lavender filled the air.

She bustled into the kitchen and put the pie down on the worktop. ‘This is a mighty fine kitchen,’ she said.

‘I know.’

‘The cooker is wondrous.’

‘I know.’

Bernadette was the polar opposite to Miriam. His wife had sparrow bones. Bernadette was fleshy, cushioned. Her hair was dyed post-box red and she wore diamanté studs on the tips of her nails. One of her front teeth was stained yellow. Her voice was big, cutting through the quiet of his home like a machete. He jangled the bracelet nervously in his pocket. Since speaking to Mr Mehra last night, he had kept it with him. He had studied each charm in turn several times.

India. It was so far away. It must have been such an adventure for Miriam. Why had she not wanted him to know? Surely Mr Mehra’s story wasn’t enough for her to keep it secret.

‘Are you okay, Arthur? You’re in a dream world.’ Bernadette’s words broke his thoughts.

‘Me? Yes, of course.’

‘I called yesterday morning but you weren’t in. Did you go to Men in Caves?’

Men in Caves was a community group for single men. Arthur had been twice to find a group of men with gloomy expressions handling chunks of wood and tools. The man who ran it, Bobby, was shaped like a skittle with a tiny head and large body. ‘Men need caves,’ he trilled. ‘They need somewhere to retreat to and be at one with themselves.’

Arthur’s neighbour with the dreadlocks had been there. Terry. He was busy filing a piece of wood. ‘I like your car,’ Arthur said to be polite.

‘It’s actually a tortoise.’

‘Oh.’

‘I saw one last week when I was mowing my lawn.’

‘A wild one?’

‘It belongs to the red-haired kids who wear nothing on their feet. It escaped.’

Arthur didn’t know what to say. He had enough trouble with cats on his rockery without a tortoise being on the loose too. Returning to his own work, he made a wooden plaque with the number of his house on it—37. The 3 was much bigger than the 7 but he hung it on his back door anyway.

It would have been easy to say yes, he was at Men in Caves, even though it had been too early in the morning. But Bernadette was standing and smiling at him. The pie smelled delicious. He didn’t want to lie to her, especially after hearing Mr Mehra’s regret over telling lies about Miriam. He would do the same and try not to lie again. ‘I hid from you yesterday,’ he said.

‘You hid?’

‘I didn’t want to see anyone. I’d set myself the task to clear out Miriam’s wardrobe and so when you rang the doorbell, I stood very still in the hallway and pretended not to be at home.’ The words tumbled off his tongue and it felt surprisingly good to be this honest. ‘Yesterday was the first anniversary of her death.’

‘That’s very truthful of you, Arthur. I appreciate your honesty. I can see how that would be upsetting. When Carl died … well, it was a hard thing to let him go. I gave his tools to Men in Caves.’

Arthur felt his heart dip. He hoped that she wouldn’t tell him about her husband. He didn’t want to trade stories of death. There seemed to be a strange one-upmanship amongst people who had lost spouses. Only last week in the post office he had witnessed what he would describe as boasting amongst a group of four pensioners.

—‘My wife suffered for ten years before she eventually passed away.’

—‘Really? Well, my Cedric was flattened by a lorry. The paramedics said they’d never seen anything like it. Like a pancake, one said.’

—Then a man’s voice, breaking. ‘It was the drugs, I reckon. Twenty-three tablets a day they gave her. She almost rattled.’

—‘When they cut him open there was nothing left inside. The cancer had eaten him all up.’

They talked about their loved ones as if they were objects. Miriam would always be a real person to him. He wouldn’t trade her memory like that.

‘She likes lost causes,’ Vera, the post office mistress, said to him as he took a pack of small brown manila envelopes to the counter. She always wore a pencil tucked into her round tortoiseshell glasses and made it her business to know everything and everyone in the village. Her mother had owned the post office before her and had been exactly the same.

‘Who does?’

‘Bernadette Patterson. We’ve noticed that she brings you pies.’

‘Who has noticed?’ Arthur said, feeling angry. ‘Is there a club whose role it is to pry into my life?’

‘No, just my customers having a friendly information exchange. That’s what Bernadette does. She’s kind to the hopeless, helpless and useless.’

Arthur paid for his envelopes and marched out.

He stood and switched on the kettle. ‘I’m giving Miriam’s things to Cat Saviours. They sell clothes, ornaments and things to raise money to help mistreated cats.’

‘That’s a nice idea, though I prefer small dogs myself. They’re much more appreciative.’

‘I think Miriam wanted to help cats.’

‘Then that’s what you must do. Shall I pop this pie in the oven for you? We can have lunch together. Unless you have other plans …’

He was about to murmur something about being busy but then remembered Mr Mehra’s story again. He had no plans. ‘No, nothing in the diary,’ he said.

Twenty minutes later as he dug his knife into the pie, he thought about the bracelet again. Bernadette could give him a woman’s perspective. He wanted someone to tell him that it was of no significance and that, although it looked expensive, you could buy good reproductions cheaply these days. But he knew the emerald in the elephant was real. And she might gossip about it to Post Office Vera and to her lost causes.

‘You should get out more,’ she said. ‘You only went to Men in Caves once.’

‘I went twice. I do get out.’

She raised an eyebrow. ‘Like to where?’

‘Is this Mastermind? I don’t remember applying.’

‘I’m just trying to take care of you.’

She saw him as a lost cause, just as Vera had implied.

He didn’t want to feel like this, be treated like this. An urge swelled in his chest. He needed to say something so she wouldn’t think him helpless, hopeless and useless, like Mrs Monton who hadn’t left her house in five years and who smoked twenty Woodbines a day, or Mr Flowers who thought there was a unicorn living in his greenhouse. Arthur had some pride left. He used to have meaning as a father and a husband. He used to have thoughts and dreams and plans.

Thinking of the forwarding address Miriam had left on her letter to Mr Mehra, he cleared his throat. ‘Well, if you must know,’ he said hurriedly, ‘I’ve been thinking about going to Graystock Manor in Bath.’

‘Oh yes,’ Bernadette mused. ‘That’s where the tigers roam free.’

Bernadette was a one-woman almanac of the UK. She and Carl had toured everywhere together in their luxury campervan. The back of Arthur’s neck bristled as he prepared to hear where he should and shouldn’t go, what he should and shouldn’t do, at Graystock.

As she busied herself in his kitchen, straightening his scales and checking that his knives were clean enough, Bernadette recited what she knew.

No, Arthur didn’t know that five years ago Lord Graystock had been mauled by a tiger, which sank its teeth and claws into his calf, and now he walked with a limp. He also didn’t know that, as a younger man, Graystock kept a harem of women of all nationalities, like a hedonistic Noah’s ark, or that he was renowned for hosting wild orgies at his manor in the sixties. He also didn’t know that the lord only wore the colour electric blue, even his underwear, because he had once been told in a dream that it was lucky. (Arthur wondered if he had been wearing electric blue during the tiger attack.)

He also now knew that Lord Graystock tried to sell his manor to Richard Branson; however the two men had fallen out and refused to speak to each other ever again. The lord was now a recluse and only opened up Graystock Manor on Fridays and Saturdays and the public were no longer allowed to look at the tigers.

After Bernadette’s tales, Arthur now felt well informed about Lord Graystock’s life and times.

‘It’s just the gift shop and gardens that are open now. And they’re a bit tatty.’ Bernadette finished cleaning Arthur’s mixer taps with a flourish. ‘Why are you going there?’

Arthur looked at his watch. He wished he hadn’t said anything now. She had taken twenty-five minutes to regale him. His left leg had grown stiff. ‘I thought it would be a nice change,’ he said.

‘Well, actually, Nathan and I are going to be down in Worcester and Cheltenham next week. We’re looking at universities. Tag along if you like. You could head off to Graystock on the train from there.’

Arthur’s stomach felt fizzy. Going to Graystock had only been a mild consideration for him. He hadn’t actually planned to go there. He only went on outings with Miriam. What was the point of going alone? He had only mentioned going to Graystock to show Bernadette that he wasn’t useless. Now apprehension nagged him. He wished he could turn back the clock and not have pushed his hand into the boot and discovered the bracelet. Then he would never have phoned the number on the elephant. He wouldn’t be sitting here discussing Graystock Manor with Bernadette. ‘I’m not sure about it,’ he said. ‘Another time perhaps …’

‘You should go. Try to move on with your life. Small steps. An outing might do you good.’

Arthur was surprised to feel a tiny kernel of excitement taking root in his stomach. He had found out something about his wife’s past life and his inquisitive nature was compelling him to find out more. The only feelings he experienced these days were sadness, disappointment and melancholy, so this felt new. ‘I like the idea of tigers walking around an English garden,’ he said.

And he did like tigers. They were strong majestic colourful beasts, prowling around with the key purposes in life of hunting, eating and mating. Humans were so different with their lives of meekness and worry.

‘Really? I’d have you down more as a small dog person, you know a terrier or something. Or you look like the kind of person who would like hamsters. Anyway, why don’t you come with us in the car? Nathan is driving.’

‘Are you not taking the campervan?’

‘I’m selling it. It’s too big for me to handle and I’ve been paying for storage since Carl died. Nathan’s got a Fiesta. It’s a rust bucket but reliable.’

‘Shouldn’t you ask him first? He might have other plans …’ Arthur instinctively found himself trying to get out of the trip. He should have kept his mouth shut. He couldn’t carry out his daily chores if he went away. His timings would be up the shoot. Who would care for Frederica the fern and stop the cats crapping in his garden? If he went down south then he might have to stay overnight. He had never packed his own suitcase before. Miriam did that kind of thing for him … His brain ticked away trying to find excuses. He didn’t want to pry on his wife but he did want to discover more about her life before they met.

‘No, no. Nathan doesn’t really do thinking. I do it all for him. It will do him good to have some self-responsibility. He won’t have remembered that he has to look at universities. I know he won’t need to apply for a few months but I want to start early. I will be so lonely when he goes. It will be strange being on my own again. I dread to think how he’ll cope away from me. I’ll visit him in his student digs and find his skeleton because he’s forgotten to eat …’

Arthur had been about to say that, now he thought about it, he might go later in the year. He already knew that he didn’t want to go on a trip with Bernadette and her son. He had met Nathan briefly once before when he and Miriam had bumped into Bernadette at a coffee morning. He seemed like a monosyllabic kind of young man. Arthur really didn’t want to leave the security of his house, the smothering comfort of his routine.

But then Bernadette said, ‘When Nathan leaves, I will be all on my own. A lonely widow. Still, at least I have you and my other friends, Arthur. You’re like family to me.’

Guilt twisted his gut. She sounded lonely. It was a word he would never have used to describe her. Every cautious nerve in his body told him not to go to Graystock. But he wondered what connection Miriam had there. It seemed a highly unlikely address for her. But then so was India. Lord Graystock sounded an intriguing character and his family had owned the manor for years, so there was a possibility that he might know or remember Miriam. He might know the stories behind more of the charms. Could Arthur really expect to be able to forget all about the charm bracelet, to put it back in its box and not discover more about his wife as a young woman?

‘Do you mind if I’m honest with you?’ Bernadette said. She sat down beside him and wrung a tea towel in her hands.

‘Er, no …’

‘It’s been difficult for Nathan since Carl died. He doesn’t say much but I can tell. It would be good for him to have a little male company. He has his friends but, well, it’s not the same. If you could give him a bit of advice or guidance while we’re travelling … I think that would do him good.’

It took all his might for Arthur not to shake his head. He thought about Nathan with his runner-bean body and black hair that hung over one eye like a mortuary curtain. When they met, the boy had hardly spoken over his coffee and cake. Now Bernadette was expecting Arthur to have a man-to-man talk with him. ‘Oh, he won’t listen to me,’ he said lightly. ‘We’ve only met the once.’

‘I think he would. All he hears is me telling him what and what not to do. I think it would do him the world of good.’

Arthur took a good look at Bernadette. He usually averted his eyes, but this time he took in her scarlet hair: her dark grey roots were springing through. The corners of her mouth drooped downwards. She really wanted him to say yes.

He could take Miriam’s things to the charity shop. He could put the bracelet back in his wardrobe and forget about it. That would be the easy option. But there were two things stopping him. One, was the mystery of it. Like one of the Sunday afternoon detective stories that he and Miriam watched, finding the stories behind the charms on the bracelet would nag at his brain. He could find out more about his wife and feel close to her. And the second was Bernadette. In the many times she had called around with her pies and kind words, she had never once asked for anything in return—not money, not a favour, not to listen to her talk about Carl. But now she was asking him for something.

He knew that she would never insist, but he could tell by the way she sat before him, turning her wedding ring around and around on her finger, that this was important to her. She wanted Arthur to accompany her and Nathan on their trip. She needed him.

He rocked a little in his chair, telling himself that he had to do this. He had to silence the nagging voices in his head telling him not to go. ‘I think a trip to Graystock would do me good,’ he said before he could change his mind. ‘And I think me and Nathan will get along just swell. Count me in.’

On the Way (#ulink_4736aa4e-a75b-5b5a-9734-1075895f18f0)

Nathan Patterson existed in that he had a body and a head and arms and legs. But Arthur wasn’t sure if there were any thoughts inside him making his body operate. He walked like he was on an airport conveyer belt, looking as if he was gliding. He was reed thin and dressed in tight black jeans that hung off his hips, a black T-shirt with a skull on it and bright white training shoes. His fringe obscured most of his face.

‘Hello, Nathan. It’s very nice to meet you again,’ Arthur said brightly and offered his hand as they stood together on the pavement outside Bernadette’s house. ‘We met at a coffee morning once, do you remember?’

Nathan looked at him as if he was an alien. His hands hung by his sides. ‘Nah.’

‘Oh well, it was only briefly. I understand that you’re looking at universities. You must be a very smart young man.’

Nathan turned his head and looked away. He opened the car door and got into the driver’s seat without speaking. Arthur stared after him. This could be a long journey. ‘I’ll sit in the back, shall I?’ he said, to no response as he got in the car. ‘Give you and your mum a chance to talk in the front.’

Arthur had wheeled his suitcase over to Bernadette’s house after lunch. He had given Frederica extra water and felt quite guilty leaving her behind. ‘It will just be for a couple of days,’ he muttered as he gave her leaves a wipe with a damp cloth. ‘You’ll be fine. Me and you, we can’t just sit around any longer. Well, you can. But I have to go. I’m going to find things about Miriam that I didn’t know. I think you would want this for me.’ He examined Frederica for a sign, a shake of her leaves or a bubble of water in her soil, but there was nothing.

He packed a spare shirt and underwear, his toiletries, cotton pyjamas, an emergency carrier bag and a sachet of hot chocolate. Bernadette had booked him a single room at the Cheltenham bed and breakfast they were staying at that night. ‘It looks nice,’ she said. ‘Some rooms have a view of Cheltenham Minster. It will just be like being in York, Arthur. So you won’t feel homesick.’

Bernadette bustled out of her house. She wheeled out a navy blue suitcase and then a purple one, followed by four Marks and Spencer carrier bags.

Arthur wound the window down. He assumed that Nathan would rush out to help, but the young man sat with his feet on the dashboard eating a bag of crisps. ‘Do you need a hand?’

‘I’m fine. I’ll just load this little lot into the boot then we can set off.’ She slammed the boot door shut then took the front seat next to Nathan. ‘Now, do you know where we’re going?’

‘Yes,’ her son sighed.

‘It should take us around three hours to get to our accommodation,’ Bernadette said.

In the car Nathan turned up the radio so loud that Arthur couldn’t think. Rock music blared out. A male singer screamed about wanting to kill his girlfriend. Periodically, Bernadette turned and gave Arthur a smile and mouthed, ‘Okay?’

Arthur nodded and gave a thumbs-up. He was already tense about changing his morning routine. He hadn’t shaved and he didn’t remember washing out his teacup. When he got back from the trip it would have a thick collar of beige gunk inside. Perhaps he had over-watered Frederica. Had he swept up the crumbs from the worktop? He shuddered at the thought. And he had locked the front door properly, hadn’t he?

To cancel out his worries, he tucked his hand in his pocket and wrapped his fingers around the heart-shaped box. He stroked the textured leather and felt the small padlock. It felt comforting to have something that belonged to his wife so close to him, even if he didn’t know where it had come from.

As they drove along tree-lined roads toward the motorway, Arthur felt his eyes shutting. He widened them but then slowly they flickered and closed again. The shush of tyres on tarmac lulled him to sleep.

He dreamed that he was on a picnic with Miriam, Lucy and Dan at the seaside. He couldn’t recall which town. Lucy and Dan were still young enough to be excited by a trip to the sea and a 99 ice cream. ‘Come and have a paddle, Dad.’ Dan tugged his hand. Sunlight rippled like silver sweet papers on the surface of the sea. The air smelled of freshly cooked doughnuts and vinegar from the food vans on the promenade. Seagulls cawed and swooped overhead. The sun shone hot and bright.

‘Yes, come on in, Arthur.’ Miriam stood facing him. The sun was behind her and she looked as if she had a golden halo in her hair. He admired the silhouette of her legs through her translucent white dress. He sat on the sand, his trousers rolled up to his ankles. Perspiration formed under his mustard tank top.

‘I’m a bit tired,’ he said. ‘I’ll just have a lie down on the sand and watch you three. I’ll catch up on the day’s news.’ He patted his newspaper.

‘You can do that anytime. Come on in with us. We can relax tonight when the kids are in bed.’

Arthur smiled. ‘I’ll just stay here. You and the kids go paddle.’ He reached up and ruffled Lucy’s hair.

His wife and two kids stood and stared at him for a few seconds before giving up on their persuasion. He watched as they held hands and ran toward the sea. For a moment he almost stood up and raced after them, but they disappeared into a sea of beach umbrellas and coloured towels. He took off his tank top, rolled it up and put it under his head.

But because this was a dream, he was able to rewind events in his head. This time when his wife stood before him inviting him to paddle, he said yes. Because he knew he might never have this moment again. Because he knew that his time with the kids was precious, and in the future Dan would live thousands of miles away and Lucy would be distant. He knew there would be so many times over the coming years that he would long to be on the beach with his family again.

So this time, in his dream, he stood up and took Dan’s and Lucy’s small clammy, sandy hands in his own. They ran down the sand together, the four of them in a line, laughing and squealing. And he kicked the sea until it soaked his trousers to the thighs and made his lips salty. Miriam waded toward him. She laughed and trailed her fingertips in the water. Lucy clung to his legs and Dan sat with the sea lapping around his waist. Arthur wrapped an arm around his wife’s waist and pulled her close to him. He saw that freckles had sprung to life on her nose and she had pink sun circles on her cheeks. There was nowhere he wanted to be more than this. He leaned in toward her, feeling her breath on his mouth and …

‘Arthur. Arthur!’

He felt a hand on his knee. ‘Miriam?’ He opened his eyes. His time with his wife and children vanished abruptly. Bernadette was leaning over from her front seat. Her door was open. He could see expanses of grey tarmac. ‘You dropped off. We’re at the services. I need to spend a penny.’

‘Oh.’ Arthur blinked, readjusting to the real world. He could still feel Miriam’s hand in his. He wanted to be with her so badly, to kiss her lips. He wriggled out of his slump. ‘Where are we?’

‘We’ve almost reached Birmingham already. The roads are quiet. Come on out and stretch your legs.’

He did as he was told and got out of the car. He had been asleep for two hours. As he walked toward the grey slab of a building, he wished that he could slip back into his dream to be with his family again. It had seemed so real. Why hadn’t he appreciated those moments when they were happening?

He meandered around WHSmith and bought a Daily Mail and then a coffee in a cardboard cup from a machine outside. It tasted of soil. The lobby rang with the sound of amusement machines, their coloured lights flashing and piping out jaunty electronic music. He could smell fried onion rings and bleach. He carefully placed his half-drunk coffee in the bin and went to the loo.

Back at the car he found himself alone with Nathan.

The boy was sitting with his feet on the dashboard again, displaying an expanse of milky ankle. In the back Arthur opened up his paper. There was going to be a heatwave over the next couple of days. The hottest May in decades. He thought of Frederica’s soil and hoped it would stay moist.

Nathan took a yellow curl from his packet of crisps. After taking the longest time that Arthur had known anyone eat a crisp, he finally said: ‘So are you and my mum, you know …?’

Arthur waited for the next part of the sentence, which didn’t arrive. ‘I’m sorry, I …’

‘You and Mum. Are you, y’know, getting it on?’ He then affected a posh accent as he turned to face Arthur. ‘Are you dating?’

‘No.’ Arthur tried not to sound aghast. He wondered how Nathan could possibly have got this idea. ‘Definitely not. We’re just friends.’

Nathan nodded sagely. ‘So, you have a separate room at the B and B?’

‘Of course I have.’

‘I was just wondering.’

‘We are definitely just friends.’

‘I’ve noticed that she makes you the savoury stuff, pies and shit. Her others only get sweet things.’

Her other lost causes, Arthur thought. Mad Mr Flowers, housebound Mrs Monton and Co. ‘I really appreciate your mother’s efforts for me. I’ve been going through a tough time and she’s been a great help. I prefer savoury to sweet.’

‘Oh, yeah.’ Nathan finished munching his crisps. He folded up the packet, tied it into a knot, then positioned it beneath his nose and wore it as a moustache. ‘My mum gets off on helping people. She’s a real saint.’

Arthur didn’t know if he was being sarcastic or not.

‘Your wife. She died, didn’t she?’ Nathan said.

‘Yes, she did.’

‘That must’ve been pretty shit, huh?’

For a second, Arthur felt like jumping over the seats into the front of the car and ripping the crisp packet out from under Nathan’s nose. How easily young people could dismiss death, as if it was some far-off country that they’d never get to visit. And how dare he talk so casually about Miriam like that. He dug his fingernails into the leather seat. His cheeks burned and he stared out of the window to avoid catching Nathan’s gaze in the vanity mirror.

A woman wearing a black T-shirt printed with a badger was dragging her screaming toddler across the car park. The little girl clutched a Happy Meal bag. An elderly lady stepped out of a red Ford Focus and began to shout too. She pointed at the bag. Three generations of family arguing over a McDonald’s hamburger.

Arthur had to answer Nathan because it would be rude not to, but he couldn’t be bothered to describe how he felt. ‘Yes. Pretty shit,’ he responded, not even realising he had sworn.

‘Here we are then.’ Thankfully, the front door opened and Bernadette manoeuvred a series of stuffed carrier bags into the footwell of the car. She then tried curving into her seat to fit herself around them. ‘Ready for off?’ she asked, fastening her seat belt.

‘What have you got in there, Mum? There’s only a MaccieD.’s and a WHSmith in that place,’ Nathan said.

‘Just some magazines, drinks, chocolatey things for the journey. You and Arthur might get hungry.’

‘I thought you had food in the boot?’

‘I know, but it’s nice to have fresh stuff.’

‘I thought we’d be getting tea at the B and B,’ Nathan said. ‘We’ll be there in an hour.’

Arthur felt uncomfortable. Bernadette was only trying to please. ‘I’m a little peckish actually,’ he said, trying to support her, even though he wasn’t hungry at all. ‘A drink and snack would be just the ticket.’

He was rewarded with a warm smile, a king-size Twix and a two-litre bottle of Coke.

His bedroom at the B and B was tiny with just enough space for a single bed, a rickety wardrobe and a chair. There was the smallest sink he had ever seen in the corner with a wrapped soap the size of a Babybel cheese. The toilet and bath (the landlady informed him) were on the next floor up. No baths after nine at night and you had to give the toilet a firm flush or else it wouldn’t get rid of all the contents.

Arthur couldn’t remember the last time he had slept in a single bed. It seemed so narrow and confirmed his status as a widower. The bedding was bright and fresh though and he sat on the side of the bed and looked through the sash window. A seagull strutted along the windowsill and there was a pleasant view of the park across the street.

Usually the first thing he and Miriam would do when they got to a room in a B and B was to have a nice cup of tea and see what type of biscuit graced the courtesy tray. They had devised a rating system together. Obviously, receiving no biscuits at all scored a big fat zero. Digestives scored a two. Custard creams were a little better, coming in at a four. Bourbons, he had originally rated as a five, but had grown to appreciate them, so upgraded them to a six. Any biscuit that tasted of chocolate without containing any had to be admired. Further up the scale were the posh biscuits usually provided by the larger hotel chains—the lemon and ginger or chocolate chip cookies, which came in at an eight. For a ten, the biscuits had to be home-made by the proprietors, and this was very rare.

Here, there was a packet of two ginger nuts. They were perfectly acceptable but the sight of them in their packet made his heart sink. He took one out and munched on it then folded over the packet and put it back on the tray. The remaining ginger nut was Miriam’s biscuit. He couldn’t bring himself to eat it.

There were still two hours before he had arranged to meet Bernadette and Nathan for their evening meal in the restaurant downstairs. He and Miriam would usually put their anoraks on and go for a walk to explore and get their bearings, to plan what they would do the next day. But he didn’t want to go out on his own. There didn’t seem much point in discovering things alone. Out of the window he watched as Nathan sloped out toward the park. He had one hand dug in his pocket and smoked a cigarette. Arthur wondered if Bernadette knew about this bad habit.

He took the box from his pocket and opened it up on the windowsill. Even though he was used to seeing it now, used to handling it, he still couldn’t relate the bracelet to his wife. He couldn’t imagine something so chunky and bold dangling from her slender wrist. She had taken pride in having elegant taste and was often mistaken for being French because of her classic way of dressing. In fact, she often said that she admired the way French ladies dressed and that one day she would like to go to Paris. She said it was chic.

When she began to feel ill, felt her chest growing tight and the shortness of breath, she changed the way she dressed. Her navy blue silk blouses, cream skirts and pearls were replaced by the shapeless cardigans. Her only aim was to keep warm. She even shivered when the sun beat down on her skin. She wore her anorak in the garden, her face bravely tilted toward the sun as if she were confronting it. Ha! I can’t feel you.

‘I just don’t understand why you didn’t tell me about India, Miriam,’ he said aloud. ‘Mr Mehra’s story was unfortunate, but there was nothing for you to be ashamed of.’

A magpie stood on the other side of the window and stared in at him, and then it seemed to look at the bracelet. Arthur tapped the window. ‘Shoo.’ He held the box to his chest and squinted at the charms. The flower was made of five coloured stones surrounding a tiny pearl. The paint palette had a tiny paintbrush and six enamelled blobs to represent paint. The tiger snarled, baring pointed gold teeth. He looked at his watch again. There was still an hour and forty-five minutes to go before dinner.