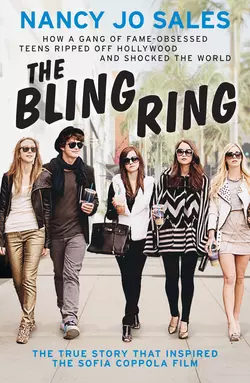

The Bling Ring: How a Gang of Fame-obsessed Teens Ripped off Hollywood and Shocked the World

Nancy Jo Sales

Published alongside the 2013 film The Bling Ring, directed by Sofia Coppola and starring Emma Watson, this is the explosive true story of the seven celebrity-obsessed teens who became the most audacious burglary gang in Hollywood history.It’s 19 September 2010, and 21-year-old Rachel Lee has emerged from Los Angeles Superior Court, having just been sentenced to four years behind bars.A few months earlier, she had been running the Bling Ring: a gang of rich, beautiful, wild-living Valley teens who idolised celebrity, designer labels and luxury brands. Who, in 2009, became the most audacious thieves in recent Hollywood history.In a case that has shocked the nation, the seven schoolfriends stole millions of dollars’ worth of clothing, jewellery and possessions from the sprawling mansions of Paris Hilton, Lindsay Lohan and Orlando Bloom, among others – using gossip websites, Google Earth and Twitter to aid their crimes.But what made these kids – all of whom already enjoyed designer clothes, money, cars and social status – gamble with their lives at such high stakes?Journalist Nancy Jo Sales, the author of Vanity Fair’s acclaimed exposé of the Bling Ring, gained unprecedented access to the group to answer that question. In the process she uncovered a world of teenage greed, obsession, arrogance and delusion that surpassed her wildest expectations.Now, for the first time, Sales tells their story in full. Publishing to tie into Sofia Coppola’s film of the same name, this is a fascinating look at the dark and seedy world of the real young Hollywood.

Clockwise, from top left: Diana Tamayo, Jonathan Ajar, Alexis Neiers, Rachel Lee, Roy Lopez, Courtney Ames, and Nick Prugo.

For Zazie

Preface

Part One

THE FAME MONSTER

Part Two

DANCING WITH THE STARS

Part Three

ALMOST FAMOUS

Author’s Note

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

(#u3ed3969d-b553-5c0b-ab7e-4362b5f4479d)

In the spring of 2010 I got a message from someone in Sofia Coppola’s office saying that Sofia was interested in optioning my Vanity Fair story, “The Suspects Wear Louboutins,” which had just run in that year’s Hollywood Issue. I was thrilled, but also wondered what in this story could possibly appeal to Sofia Coppola. It was about a teenage burglary ring that had targeted the homes of Young Hollywood between 2008 and 2009. The burglars, most of them recent high school graduates, had made off with nearly $3 million in designer clothing, jewelry, luggage and art from a collection of “stars” you wouldn’t exactly expect to see in a Sofia Coppola movie—Paris Hilton, Lindsay Lohan, Audrina Patridge (one of the girls on the reality show The Hills), to name a few. They were famous mainly for being famous, defined by a new kind of celebrity that was all about Facebooking and tweeting and the flashing of thongs. Or maybe the Instagramming of thongs.

It was also a story about kids from an affluent suburb in the Valley—another factor that seemed to make it an unlikely subject for Sofia. She made beautiful-looking movies about beautiful places—she’d shot much of Marie Antoinette (2006) at Versailles, the only person ever allowed to film there—and this was a story about a tackier world where the rich were brash and bloated on their wealth … But then, that sounded a lot like the Ancien Regime before the French Revolution. And maybe the one percent in America today.

But when I started re-watching some of Sofia’s movies in anticipation of meeting her, I realized that the themes in the story of the “Bling Ring”—the name given to the burglary ring by the L.A. Times—were some of the same themes she had been exploring in her films: the obsession with celebrity; the entitlement of rich kids; the emptiness of fame as an aspiration or a way of life. Her first feature, The Virgin Suicides (1999), based on the novel by Jeffrey Eugenides, was about a family of rich girls in Gross Pointe, Michigan, who unaccountably all kill themselves, thereby becoming “famous” in their neighborhood. Sofia’s Marie Antoinette, played by Kirsten Dunst, was a spoiled teenager and a rock star in her own time (until, of course, she lost her head). Lost In Translation—for which Sofia won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay in 2004—was a portrait of an action star (Bill Murray) drowning in a fishbowl of fame; and in Somewhere (2010), Stephen Dorff plays another famous actor living in the legendary Chateau Marmont hotel and finding his existence at the center of Hollywood lonely and meaningless. So, it seemed, the story of a gang of fame-obsessed teens that had robbed the homes of celebrities was to Sofia Coppola sort of like a good horror story was to Hitchcock.

It happened to be right up my alley too. When news of the Bling Ring burglaries first came out, a friend of mine joked that it was like a “Nancy Jo Sales story on speed.” I suppose I knew what he meant. I’d been writing about the misadventures of rich kids since 1996, when I did a story for New York magazine my editor headlined “Prep School Gangsters.” It chronicled the lives of private school students in New York as they acted out underworld fantasies based on gangsta rap and too many viewings of Goodfellas. It was entirely by accident that I got on this beat, which has led me to stories on clubkids and kid models and socialites and d.j.’s and rich kids in love. At the same time, I was doing celebrity profiles on some of the very people these fame-conscious kids wanted to be—Puffy and J-Lo and Tyra and Leo and Jay-Z and Angelina, as well as two of the Bling Ring’s famous victims, Hilton and Lohan. (I did the first magazine story on Hilton, for Vanity Fair, in 2000.)

• • •

I met Sofia for the first time at café in Soho, the Manhattan neighborhood where she was then living with her husband, Thomas Mars, the front man for the alternative French rock band Phoenix, and their daughter, Romy, then 3. Sofia was pregnant at the time with her second child (Cosima, who would be born in May 2010), and putting the finishing touches on Somewhere in the editing room. It was a warm, bright day, and Sofia, in a light purple cotton dress, looked very lovely, with her slanting brown eyes and creamy skin. She was soft-spoken and calm and had a dreamy quality about her which somehow reminded me of the delicate touch of her films. We sat at a table at the back of the restaurant and had breakfast, coffee for me, tea for her. I asked her what had interested her in the Bling Ring story, which she said she had read on an airplane returning to New York from L.A.

“I thought, somebody should make a movie of this,” she said, “and I thought probably someone already was. It never occurred to me that this was something that I would do. Then I kept going back to it—I think because it had in it all of these things that I’m worried about in our culture, or thinking about. I don’t know if ‘microcosm’ is the right word, but somehow it distills all the cultural anxiety of right now. I feel like this story kind of sums it all up.

“To me it’s the whole idea of the narcissism and the reality TV and the social media obsession of kids of this generation,” she said, “and the entitlement—that they,” the Bling Ring kids, “thought it was O.K. to just go into these homes and take whatever they wanted. I think all these themes are in this story and this was what I was connecting to without being aware of it at first. I think it’s about what our culture is all about right now—it’s just so different from when I was growing up….”

Sofia grew up in the Napa Valley, where her father, The Godfather (1972) director Francis Ford Coppola, moved her family from New York in the 70s. “I always knew that we got special attention and the attention was all about him,” she said, smiling, when I asked if she had realized as a child that her father was famous. “But we lived in Napa, which doesn’t have a lot of showbiz people, so we were like ‘the Hollywood people’ there. I feel like that must have had some influence on why I’m always drawn to this step-world, this meta-world” of people living with some kind of fame.

She was raised in a household full of celebrities who to her weren’t celebrities—they were just her family. Sofia wouldn’t be Sofia if she hadn’t grown up around filmmakers. Her mother, Eleanor Coppola, is a documentary filmmaker; her brother Roman is a screenwriter and filmmaker; her aunt Talia Shire and cousins Jason Schwartzman and Nicolas Cage are actors; and her grandfather, Carmine Coppola, was an Oscar-winning film composer. (Her older brother, Gio, a budding director, died in a speedboat accident in 1985.)

Her parents’ friends were filmmakers and writers, actors and artists. One of her earliest memories is sitting on Andy Warhol’s knee. Marlon Brando, Werner Herzog, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas were all dinner guests at her family’s home. Her Italian father set the tone, which was warm and inclusive, so the kids were always around listening to the adults talking about filmmaking. “I think I was learning all these things sort of without knowing it,” Sofia said. And when she and her family would accompany her father on film shoots—they spent months in the Philippines during the filming of Apocalypse Now (1979)—she would watch filmmaking firsthand. (Her mother co-directed an unforgettable documentary about that experience, 1991’s Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse, in which little Sofia appears.) “For me as a kid it was just about getting to take a helicopter ride over the jungle,” said Sofia.

In her teens she became fascinated with fashion; at 15, she worked as an intern for Chanel. “When I was a kid nobody had designer handbags,” she remembered. “In high school there wasn’t all this label awareness. It wasn’t as much of a mainstream culture thing back then. I remember going to fashion shows and you’d never see celebrities sitting in the front row. Now celebrities have clothing lines—and now Alexis [Neiers],” one of the Bling Ring burglars, “wants to be a fashion designer too.”

As did several other kids in the burglary ring. As I got to know Sofia, it struck me that as a teenager she had had some of the same aspirations as the Bling Ring kids—the difference being, of course, that she was the genuine article, the sort of It Girl they longed to become. After leaving the California Institute of the Arts, where she had studied photography and costume and fashion design, she started her own clothing line, Milkfed, which is still sold exclusively in Japan.

Over the almost three years between our first meeting and the completion of The Bling Ring, which premieres on June 14, 2013, Sofia and I would get together to talk about the movie she was writing and then directing. I always looked forward to seeing her. She was fun to talk to. It seemed we were always gossiping about Hollywood, as if something about the subject matter we were dealing with was turning us into the worst kind of tabloid junkies. We talked about the celebrification of everything, which seemed to have happened overnight, over roughly the last decade. I said I thought the milestone was the ascendance of Paris Hilton. Sofia said she thought it was the explosion of tabloid journalism.

“I think Us Weekly changed everything,” Sofia said, referring to how Us magazine went from a monthly to a weekly in 2000, becoming more gossipy and invasive and igniting a huge boom in the coverage of celebrities. “I remember living in L.A. before Us Weekly and you could go out and do things and have privacy,” she said. “I mean, I don’t feel like I’m really in that [celebrity] world, but suddenly it was different. There weren’t paparazzi around all the time before. And another big change was TMZ,” which launched in 2005. “I remember I went and lived in France for a few years and then I came back TMZ was everywhere and it was so weird. It happened fast, too, like TMZ and Twitter and reality TV all of a sudden were everything and it was like our culture just went crazy.

“With Twitter,” she said, “it’s insane how accessible these stars are”—so accessible that the kids in the Bling Ring “thought that they knew them because they knew what they were eating for breakfast. So they felt comfortable going in their homes.”

Sofia seemed to share my amazement for the way the kids in the story spoke about what they had done, as if they were already stars themselves—especially Alexis Neiers. Sofia had read the transcripts of my interviews with Alexis and some of the other Bling Ring defendants, some of the dialogue from which she said she was incorporating into her film. “When people [she was showing her script to] read it,” she said, “they’re like, oh my God, how did you come up with that? And I tell them that was real, that comes from the transcripts. I used the real stuff because I couldn’t make it up, it’s so absurd.”

In my Vanity Fair piece, for example, Alexis tells me how she thinks she might “lead a country” some day. Her comment wasn’t directly related to the burglaries—but perhaps it was. At 18, she was already convinced of the power of her pseudo-fame.

“It’s so weird to me today,” Sofia said, “this whole idea of being famous for nothing. I guess that started with the reality TV thing and then it became normal. The [Bling Ring] kids all wanted to be famous for no reason. When I was a kid people were famous because they accomplished something, they did something.

“I feel like such an old fogie complaining about all this,” she said, smiling self-consciously.

By February 2012, Sofia had cast Emma Watson in the role of Nicki, based on Alexis Neiers (who had now become a consultant on the film, which was becoming like an Escher woodcut about celebrity). “I met with [Emma] and she was so interested in playing the part,” Sofia said, “and I felt like she had a really smart take on it. She understood the themes because of her popularity.” As a co-star of eight Harry Potter films, Watson had an almost cult-like celebrity status. “She was very interested in the whole subject matter of celebrity,” said Sofia. “And she could relate to it, she knew exactly how things are for a celebrity today—she could see it both from the kids’ perspective, who were like, her fans, and from the people on the other side, the ones who were robbed.

“I forgot how famous she was,” Sofia said. “I had the kids” who had been cast in the movie, “all go out to lunch together one day, to bond, and they got swarmed with paparazzi.” Throughout The Bling Ring shoot, which took place in Calabasas, California, and L.A. in March and April of 2012, the set would be dogged by paparazzi and videorazzi and gossiped about on celebrity blogs such as TMZ, mirroring the very themes in the film.

In preparation for their roles, Sofia had also had the young cast—which includes Israel Broussard, Katie Chang, Claire Julien and Taissa Farmiga—“rob” a house in the Hollywood Hills. “It was an improv,” Sofia said. “Before we started filming we had them actually sneak into a friend of mine’s house” (not someone famous). “We set it up so that no one would be home and we had them break into the house while my friend was away for a few hours. We left a window open and we gave them things that they had to take from the house. We gave them a list.” The Bling Ring kids often went “shopping,” as they called their burglaries, armed with lists of articles of clothing owned by their famous victims, items which they had selected from research they did on the Internet. “They did great,” Sofia said of her cast. “They were very good burglars.”

Why did the Bling Ring do what they did? Why steal celebrities’ stuff? This was something Sofia and I talked about a lot. She said, “I love the quote” from the transcripts “in which Nick [Prugo] says,” of his co-defendant Rachel Lee, “ ‘she wanted to be part of the lifestyle, the lifestyle that we all sort of want.’ I thought it was so important to put that in the film, that he assumed that that we all want that lifestyle.”

Finally, Sofia and I talked about raising daughters in a culture gone mad for fame. She told me of how her daughter Romy, now 6, had recently informed a lady in the park that her mother was “famous in France.”

“I don’t even know how she knows that or why she thinks that’s important,” Sofia said, laughing. “I hope there’s going to be a reaction against all this,” that is, our cultural obsession with fame. “There has to be right?” she asked. “I’m hoping that when our kids are teenagers and young women it’s on the reaction side.”

(#u3ed3969d-b553-5c0b-ab7e-4362b5f4479d)

(#u3ed3969d-b553-5c0b-ab7e-4362b5f4479d)

In 2007, Paris Hilton bought a house in the Mulholland Estates, a gated community in what is technically Sherman Oaks, California. The developer was able to secure the more coveted Beverly Hills, 90210, zip code for the address, which over the years has attracted many celebrity residents, including Charlie Sheen, Paula Abdul, and Tom Arnold. The development boasts panoramic views of the San Fernando Valley and some of the area’s most extravagant homes, most of them built in the 1990s, when residential architecture was continuing to reflect the mass celebration of conspicuous consumption as seen on popular television shows like Dallas and Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.

Two thousand seven was a difficult year for Hilton, from a legal perspective. Her driver’s license had been suspended on a DUI charge the year before, and, after she was caught speeding down Sunset Boulevard in her blue Bentley Continental GTC, she spent 23 days of a 45-day sentence for probation violation in jail. Meanwhile, she continued to do very well financially. Even footage that surfaced of her using a number of racial and homophobic slurs did not interfere with her growing success. The “lifestyle brand” she launched in 2004 now encompassed television, movies, music, clothing, books, jewelry, fragrances, handbags, pet apparel, and her Dreamcatcher hair extensions. Her latest reality show, Paris Hilton’s My New BFF, was in the works (contestants in the first season were asked, “Would you die for Paris?” as Hilton looked on, giggling). Hilton, still just 26, was “hot,” as she liked to say. And so she bought herself a 7,493-square-foot, five-bedroom, Mediterranean-style mansion for $5.9 million.

About a year later, on a balmy night in October 2008, two teenagers drove along Mulholland Drive toward Hilton’s home with the intention of robbing it. They were a girl and a boy, 18 and 17, who lived not far away in Calabasas, an affluent suburb in the Valley. The boy, Nick Prugo, was slight of build, with sharp, fox-like features and an anxious, flashing smile. With his prematurely thinning hair, he looked like some former Nickelodeon star who had outgrown his childhood appeal. He had a pencil-thin mustache and a sparse goatee, which complemented his trendy hipster look (hoodie, jeans, sneakers, wallet chain). The girl he said was with him in the car that night, Rachel Lee, was dark-haired and slender with a baby face that belied her steely core. As always, Rachel, who had been voted “Best Dressed” in their high school, twice, was styled to perfection in casual burglar chic (hoodie, scarf, designer T-shirt, jeans). Rachel was obsessed with fashion, Nick said, she was obsessed with clothes; that was why they were going to Paris’s house that night, because Rachel wanted Paris’s clothes.

The friends didn’t say much as they traveled along the curving mountain road toward their target’s home. The planning stages had “felt very Mission: Impossible,” Nick said, and they had taken to calling the job they were about to perform “the mission.” They’d been intense and talkative then, figuring out how they were going to gain access to a gated community with a guard. Nick had scoped out the property on Google Earth, having found Hilton’s address on Celebrity Address Aerial. (It was a website dedicated to the divulging of celebrity addresses and photographs of their residences for $99.99 a year. Its web masters took a dim view of Hilton, opining on their promotional page, “The reason so many people hate America is, quite simply, Paris Hilton.”)

When Nick checked out the aerial shots of the Mulholland Estates, he noticed an area in the back that looked accessible via a steep hill. Rachel was pleased with this finding, he said, and that pleased him; Nick liked to please Rachel. He felt a thrill as they hurtled toward this strange adventure together. He was nervous, he said, but Rachel was calm, and that calmed him down. He tried to keep his mind on the music playing in the car as they zoomed along through the dark. He liked club hits by Pharrell and Lil Wayne and songs by Atmosphere, the melancholy white rap group from Minnesota. There was one song of theirs in particular that always made him think of Rachel—called “She’s Enough.” It’s about a man who will do anything for the woman he loves:

“If she want it/I’m gonna give it up … If she needed the money/I would stick you up … She wanna do the damn thing and I’m on her side …”

Around midnight, Nick said, they arrived at the Mulholland Estates and he parked his white Toyota at the back of the development. They found the hill they were looking for easily and climbed it, making use of the smooth firebreaks—man-made clearings in its side—to help them scale it. They could hear each other panting with the effort. They weren’t athletic kids—they smoked cigarettes and weed. They both had medical marijuana cards issued by the state of California; they weren’t hard to get.

Once inside the gated community, they strolled past the cavernous castle-like mansions and gleaming luxury cars, as if in a dream. They were confident, Nick said, that if anyone spotted them, they wouldn’t be thought out of place. They looked like “normal kids”; he might be some neighbor’s boy; Rachel might be his girlfriend.

“That’s the thing that really made everything flow when me and Rachel would go out and do these things,” Nick said. “We wouldn’t be masked, we wouldn’t be in gloves. We wouldn’t be conspicuous—we’d be just natural looking so if anything ever happened we’d just be like, what? We’re normal kids. It wasn’t that we were criminals.”

He said he could never remember the exact moment when he and Rachel decided to start burglarizing the homes of celebrities; but once they did, they knew right away that Paris would be the first. “Rachel’s idea,” he said, “and, I guess, my idea, was that she was dumb. Like, who would leave a door unlocked? Who would have a lot of money lying around? Logically, anyone in America could probably figure out that if you were gonna do something to a celebrity it would be someone that wasn’t, you know, that bright….”

And then suddenly there was Paris’ house, rising before them like the villa of some Spanish contessa, all glowing yellow stone and Mediterranean tile. Nick tried to stay calm as he followed Rachel across the driveway to the front door. Their plan—well, not really a plan, it was more of an impulse, for as often as they had imagined this night, they had actually decided to just go and do it spontaneously, after having a few drinks—their plan was just to ring the bell and see if anybody answered. And if somebody did, well, then, they might get to see Paris. And that would be awesome, in a funny kind of way. They would pretend they were just a couple of ditzy kids with the wrong address, kids out looking for a party.

Rachel rang the bell, Nick said, putting on the innocent face he had seen her wear so many times before. Rachel was good at playing the pretty girl whenever adults were around asking questions. “She knew she was a good-looking girl and she knew there were certain things she could get away with. She knew how the system worked. She knew how you could play it.”

She rang and rang again … but still there was no answer. Was Paris in, or out? Promoting her handbag line at some Tokyo department store? Attending a Russian billionaire’s birthday party in Moscow (for a fee, of course)? Nick had been tracking Hilton’s whereabouts through her Twitter account and celebrity news outlets like TMZ, but he wasn’t actually sure where she was that night….

Ding-dong.

Paris Hilton’s booking photo following her arrest for reckless driving, September 2006.

Were they really going to do this thing? Or were they just going to go home with a funny story to tell their friends?

And then, Nick said, the thought occurred to him just to look under the mat. It was like finding Willy Wonka’s Golden Ticket when the glinting metal of the key appeared. Dumb was right.

“Wow.”

Inside it was like a Barbie Dreamhouse. There were images of Paris everywhere, framed photographs of Paris on the walls; framed magazine covers of Paris cover stories; framed pictures on tables of Paris with all her famous friends—there was Mariah Carey, Jessica Simpson, Fergie, Nicky Hilton (Paris’ sister), Nicole Richie (were they still close?). There were pictures of Paris in the bathrooms. Her face was silkscreened on couch pillows.

There was a lot of pink, and there were crystal chandeliers in almost every room. Even the kitchen. It was like stepping into the girliest Hilton hotel you’ve ever seen. Nick said they walked around slowly, marveling that they were really there. “There was that percentage of wow, this is Paris Hilton’s house, but as soon as I put my foot in the door, I was just wanting to run out…. It was horrifying.”

He wanted to leave, he said, but now Rachel was running up the stairs. Upstairs were the bedrooms, and the bedrooms had the closets, and the closets had the clothes. Nick said he followed Rachel to the master bedroom—it was chilly in there and smelled like the perfume counter in a department store. The room led out on to a balcony overlooking the pool and, beyond that, the rolling hills of the Valley, shimmering with lights. As they gazed in the direction of their own homes from the vantage point of one of the most Googled people on the planet, they couldn’t help but laugh.

The little dogs—Chihuahuas and a Pomeranian, Tinkerbell, Marilyn Monroe, Prince Baby Bear, Harajuku Bitch, Dolce and Prada—scurried around, regarding them curiously, but they didn’t bark. They must have been used to having strangers in the house. (About a year later, Hilton would build the dogs a 300-square-foot, $325,000 miniature of her home in the backyard. Philippe Starck would provide the furniture.)

“Oh my God!”

Nick said that Rachel squealed with delight when she found the closets. One was the size of a small room and the other the size of a small clothing store. It was like that scene where the dwarves discover the dragon’s treasure-laden lair in The Hobbit. One closet had a chandelier, and the other had furniture, as if Paris might want to just sit in there and look at all her stuff. The smaller closet had floor-to-ceiling shelves with hundreds of pairs of shoes, all lined up like trophies—Manolos, Louboutins, Jimmy Choos, a pair of YSLs shaped like the Eiffel Tower. There were shoes of every color—satiny, shiny, pointy shoes. Huge shoes. Size 11.

The bigger closet was full of racks and racks of clothes. Nick had to smile. “Rachel, do your thing,” he said. And “she was rummaging through everything, very, very into it, very focused, very ‘This is my mission.’ ” She was plowing through the racks of the wild, sparkly, feathery clothing, exclaiming over all the designers—this was Ungaro, that was Chanel! There were dresses, gowns, blouses, and coats by Roberto Cavalli and Dolce & Gabbana and Versace and Diane von Furstenberg and Prada…. Nick said Rachel recognized some of the pieces from Paris’ public appearances; she followed these things; she knew which one Paris had worn to the VMAs and the Teen Choice Awards.

He said she said it was like “going shopping.”

Now he was starting to get nervous again. He decided to go and be the lookout from the top of the stairs; from there, you could see through the big windows to the front of the house. So Nick stationed himself there. He was “sweating unnaturally,” he said. “Every five minutes I was yelling down the hall, ‘Let’s get the fuck out of here! I want to leave! Fuck this, I don’t care anymore!’ And she was like, it’s fine, it’s fine, it’s fine, let’s keep going….”

He resented the way that Rachel was always in charge, no matter what they did—he “hated that,” he said—but what could he do? This was “the girl [he] loved,” and he didn’t want to lose her. And although he’d never tested it, there was something about Rachel that said that if you didn’t do what Rachel wanted, she would walk. It wasn’t that he minded Rachel taking a few of Paris’s things—look at Paris’s house; she “had everything.” And she “didn’t really to contribute to society,” she wasn’t “some great actor like Anthony Hopkins or Johnny Depp, someone that’s really good at their craft.” She was an “heir head,” like the tabloids said, a “celebutard.”

“It wasn’t like a malicious thing for me,” Nick said. “I wasn’t out to get, like, a working-class American.”

But Nick did not want to get caught. He yelled again for Rachel to “hurry up and let’s get out of here!” But he said she just answered, “This is fine, this is okay, why are you tripping out?”

And then he saw on the wall of the stairwell the portrait of Paris scowling down at him. She was wearing a little black cocktail dress and sitting on a settee with her legs folded underneath her. She looked like a Park Avenue princess who has become very displeased about something. She was staring, glaring, as if to say, “How dare you come in my house and touch my stuff, bitch? I’m gonna get you….”

Nick bolted back down the hall to Rachel. She had selected a designer dress, he said—he couldn’t remember which, “there would be so many”—and a couple of Paris’ bras. He insisted that now it was time to leave—but not before they checked inside Paris’ purses. They knew from experience—for yes, they’d done this kind of thing before—that people with money tend to leave money lying around the house. And, sure enough, in the closet with the shoes and the sunglasses where Paris also kept her many bags—Fendi, Hermes, Balenciaga, Gucci, Louis Vuitton and on and on—they found “crumpled up cash, fifties, hundreds,” “which looked to us like she went shopping that day, and this was just her spare change.” Nick would remember the smell of the expensive leather, Rachel oohing and aahing over the labels, and the crinkling sound of the bills. They came away with about $1,800 each—a good haul.

And now it really was time to go. But first they couldn’t resist checking out the rest of the house. They wandered around—it was spooky, as if Paris were there somewhere, watching them. Paris could walk in at any time. They discovered the nightclub room with the disco ball and the padded bar. They thought about all the famous people who had been in there—Britney, Lindsay, Nicole, Nicky, Benji Madden (the Good Charlotte guitarist and then Paris’s boyfriend), Avril Lavigne…. They couldn’t help but imagine themselves there again someday, chilling, dancing, with Paris.

Nick took a bottle of Grey Goose vodka for himself, and they left.

(#u3ed3969d-b553-5c0b-ab7e-4362b5f4479d)

About a year later, in October 2009, I found myself driving along the 101 North from L.A., on my way to Calabasas. It was a fine, clear day. I had a cup of coffee in the cup holder beside me, traffic was humming, and the craggy Santa Monica Mountains lay before me like giant scoops of butter pecan ice cream. They were kind of pretty, and that was not what I was expecting. I’d never been to the Valley before. All I knew was its reputation, that it was the West Coast’s bookend to New Jersey, a place full of shopping malls and spoiled teens speaking Valley Girl. Bob Hope, a Valley resident for more than sixty years, had called it “Cleveland with palm trees.”

Vanity Fair had put me on the story of “the Bling Ring”—that was what the Los Angeles Times was calling a band of teenaged thieves that had been caught burglarizing the homes of Young Hollywood. Between October 2008 and August 2009, the bandits had allegedly stolen close to $3 million in clothes, cash, jewelry, handbags, luggage, and art from a number of young celebrities including Paris Hilton, Lindsay Lohan, and Pirates of the Caribbean star Orlando Bloom. They’d stolen a Sig Sauer .380 semi-automatic handgun that belonged to former Beverly Hills, 90210 cast member Brian Austin Green. They’d taken intimate things: makeup and underwear. It seemed they just wanted to own them, wear them.

The Bling Ring kids were from Calabasas, a ritzy suburb about thirty minutes from L.A., and that’s why I was headed there. There’d never been a successful burglary ring in Hollywood before, and somehow it made sense that it would be a bunch of Valley kids. I wasn’t sure why it did, but I thought if I went to Calabasas I might find out.

Up until the 1940s, I’d read, the Valley was “out there,” ranchland where settlers went to grow oranges and raise chickens and families. Then Hollywood discovered it as an appealing hideaway with bigger houses—Clark Gable and Carole Lombard made a love nest there, and so did Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. Jimmy Cagney moved out to play gentleman farmer, Barbara Stanwyck to run a thoroughbred ranch, but somehow the place never became glamorous. Something was always off. After the war, the population exploded, and the Valley became the defining American suburb, a sunny Eden of split-level homes, electric blue swimming pools, and kids living seemingly perfect childhoods. The Brady Bunch were tacitly Valley folk.

Frank Zappa’s song “Valley Girl” (1982) introduced the world to a young white Southern California female whose main interests were shopping, pedicures, and social status: “On Ventura, there she goes/She just bought some bitchen clothes/Tosses her head ’n flips her hair/She got a whole bunch of nothin’ in there….” Zappa learned about Valley Girls from his then 14-year-old daughter Moon Unit, who encountered them at parties, bar mitzvahs, and the Galleria mall in Sherman Oaks. The film Valley Girl, released in 1983—adding “space cadet” and “gag me with a spoon” permanently to the lexicon—explored Valley kids’ longing to be part of the supposedly cooler, star-studded world of Hollywood, so close but so far away.

Calabasas (population 23,058) was said to be a typical Valley hamlet, but with more celebrity residents, including (then) Britney Spears, Will Smith and Jada Pinkett and their already famous kids, country singer LeAnn Rimes, Nikki Sixx of Mötley Crüe and Richie Sambora of Bon Jovi, former Nickleodeon star Amanda Bynes…. Weirdly, Calabasas was also a Fertile Crescent for reality television. One of the first big reality shows featuring a (sort of) famous person, Jessica Simpson, and her then husband Nick Lachey, was shot there: Newlyweds: Nick and Jessica (2003–2005). So was Spears’ burps-and-all look at life with her then husband Kevin “K-Fed” Federline: Britney and Kevin: Chaotic (2005). And so is the Queen Mary of all reality television: Keeping Up with the Kardashians (2007–). In each of these shows, Calabasas looks like Xanadu with SUVs, a place of SoCal-style easy living, where everybody’s wealthy.

And Calabasas is rich, relatively speaking; the median income is about $116,000, more than twice the national average. According to the online Urban Dictionary (albeit an opinionated source), “The typical Calabasas resident is young, rude, rich…. You’ll see … 10-year-old girls with their Louis Vuitton purses and Seven jeans giggling to their friends on their iPhones.”

It was interesting to see how media coverage of the Bling Ring was playing up the burglars as “rich.” Said the New York Post: “A celebrity-obsessed group of rich reform-school girls allegedly waged a year-long, A-list crime spree through the Hollywood Hills, ripping off millions in cash and jewels from the mansions of such stars as Paris Hilton and Lindsay Lohan….” People always seemed fascinated by stories about rich kids. I should know, I’d done a few myself. Editors seemed to like such stories, especially if the kids were behaving badly. Readers seemed to love to hate these kids. I once received a letter, in response to one of my stories about bad rich kids in Manhattan, from a World War II veteran demanding, “Can the prep school gangsters fly a B-29?” That was a very good question.

But it was clear the appeal of the Bling Ring story wasn’t just the wealthy kids; it was one of those stranger-than-fiction tales that hits the Zeitgeist at its sweet spot, with its themes of crime, youth, celebrity, the Internet, social networking (the kids had been advertising their criminal doings on Facebook), reality television, and the media itself, all wrapped up in one made-for-TV movie (which didn’t exist yet, but would). The wall between “celebrity” and “reality” was blurring faster than you could say “Kim Kardashian.” Celebrities were now acting like real people—making themselves accessible nearly all the time; even Elizabeth Taylor tweeted (“Life without earrings is empty!”)—and real people were acting like celebrities, with multiple Facebook and Twitter accounts and sometimes even television shows documenting their—real and scripted—lives. It was all happening at warp speed, affecting American culture on a cellular level and, if you wanted to get fancy about it, begging the age-old question of “What is a self?” (And, “If I post something on Facebook and no one ‘likes’ it, do I exist?”) The Bling Ring had crossed a final Rubicon, entering famous people’s homes, and their boldness felt both disturbing and somehow inevitable.

News of the kids, so far, didn’t offer many details, and no interviews with the suspects themselves. The six who had been arrested in connection with the burglaries were Rachel Lee, 19—“the gang’s alleged mastermind,” according to the Post; Diana Tamayo, 19; Courtney Ames, 18; Alexis Neiers, 18; Nicholas Prugo, 18; and Roy Lopez, 27, who had been identified as a bouncer. Lee, Prugo, and Tamayo all reportedly knew each other from Indian Hills, an alternative high school in Agoura Hills (it was “a couple of exits away” from Calabasas, a Southern Californian had told me). The only one who had been formally charged was Prugo, with two counts of residential burglary of Lohan and reality star Audrina Patridge (she was one of the girls on The Hills, a sort of real-life Melrose Place about vacuous twentysomethings in L.A.). Prugo was facing up to twelve years in prison. Another suspect in the case, Jonathan Ajar—a.k.a. “Johnny Dangerous,” 27—who had been identified as a nightclub promoter, was wanted for questioning. TMZ was saying he was “on the run.”

The kids’ mug shots didn’t tell much, either, except that they all looked very young and bedraggled in the way people do when they get hauled into jail. Prugo looked rather cunning (later, he would admit that the black-and-white striped T-shirt he was wearing in his mug shot belonged to Orlando Bloom). Lee and Ames—a brown-haired, light-eyed girl, neither pretty nor plain—looked scared. Tamayo wore a defiant expression. Lopez looked thuggish and resigned.

And then there was this wild picture of two of the other girls—it was like a poster for Bling Ring: The Hollywood Movie (which didn’t exist yet, but would as well). It was of Alexis Neiers and her “sister”—actually her friend—Tess Taylor, 19, a Playboy model and “person of interest” in the case. They were coming out of the Van Nuys Area Jail in the wee hours of October 23, after Neiers had been released on a $50,000 bond. It looked like a paparazzi shot—in fact, it was. You had to wonder who had alerted the paparazzi to Neiers’ arrest.

In the picture, Taylor has her arm protectively slung around Neiers’ shoulder as she hustles her past photographers blasting away. Both girls have lots of lustrous dark hair and perfectly shaped eyebrows and perfectly toned, exposed midriffs. Taylor has on a black tracksuit and Ray-Ban sunglasses, although it’s night. Neiers is wearing what appear to be ice blue Juicy sweatpants and a pair of Uggs. She’s holding the end of a black scarf up around her face, dramatically concealing everything but an expertly made-up eye. The girls look like celebrities. It appears as if they think they are. What had not yet been reported was that they were the stars of an upcoming reality show, Pretty Wild, which was being filmed for E!.

“I didn’t do jack shit, it’s a joke,” Neiers told reporters outside the jail.

(#u3ed3969d-b553-5c0b-ab7e-4362b5f4479d)

“You are going to hear about five targets in this case: Rachel Lee, Nick Prugo, Diana Tamayo, Roy Lopez, and Courtney Ames. You are going to hear that these five targets know each other through school, through the neighborhood, with the exception of Roy Lopez, who the other targets know from having frequented a local [Calabasas] restaurant, Sagebrush, where he was working.

“You are going to see photographs of the targets hanging out. You are going to see that they celebrate birthdays together … that they hung out on the computer together, that they eat lunch together.

“They go to hotels together. They party together.

“But you are also going to hear that they commit crimes together, and over the course of the year between the end of 2008 and for about ten months in 2009, they committed burglaries.”

—Opening Statement, L.A. Deputy District Attorney Sarika Kim, Grand Jury proceedings in the People of the State of California vs. Nicholas Frank Prugo, Rachel Lee, Diana Tamayo, Courtney Leigh Ames, and Roy Lopez, Jr., June 18, 2010

(#u3ed3969d-b553-5c0b-ab7e-4362b5f4479d)

Some of the views around the edges of Calabasas are almost rural. You can see fields with horses grazing, swishing their tails in the sun, echoes of the days when the residents wore desert boots instead of Louboutins. It makes you feel, suddenly, very far away from Hollywood. The approach to town turns suburban; the inevitable car dealerships, fast food chains, and shopping malls appear. The mountains as they draw closer grow greener and still prettier. Calabasas, meanwhile, is beige. Everything is overcast with a wash of sameness—a clean and shiny sameness, a corporate sameness. It’s as if Calabasas should have a logo.

Once I got to town, I pulled into the parking lot of a Gelson’s market in order to do a Google Maps search on Nick Prugo, ironically enough. Prugo was said to be the Bling Ring’s surveillance-meister, the one who found the celebrities’ addresses and pictures of their homes on the Internet. TMZ, which was all over this story (they were calling the gang “the Burglar Bunch”), had posted a Google Maps search of Orlando Bloom’s home that Prugo had allegedly done on a stolen computer; they were calling the image a “smoking gun.” (It was a bit of a mystery how TMZ was getting its hands on all these interesting things, but more on that later.)

I’d located Prugo’s address using a garden variety people-finding website. More than a decade before, an editor had asked me to do a story on how easy it was to track down the world’s most elusive literary recluse, Thomas Pynchon, with the click of a mouse. Nothing much had changed since then, except that privacy had all but disappeared. Everybody was spying on everybody. Prugo’s data mining was nothing compared to Facebook’s. “It was information anyone in America could get,” he would tell me later.

As I was sitting there trying to get directions, I looked up and saw two funky-looking, middle-aged people hurrying past my car. A couple of photographers were chasing them, shouting, “Sharon!” “Ozzy!” It was the Osbournes. They’d moved to the Valley in 2007 after the success of their reality show, The Osbournes (2002–2005). I’d never seen paparazzi working in quite so mundane a setting before. The other people in the parking lot just strolled along with their carts as if nothing out of the ordinary were happening. Ozzy, wearing his signature-tinted granny glasses, looked a little rattled.

It got me thinking about the Lady Gaga song “Paparazzi” (2008), which was still all over the radio at that time. It seemed like an anthem for our celebrity-obsessed age, or at least for this story I was working on. Gaga equates modern love with a love of fame—to be in love is to be a celebrity stalker, a paparazzi: “I’m your biggest fan/I’ll follow you until you love me/Papa-paparazzi….” Now it was as if everybody had become their own fan. Everybody was broadcasting themselves on social media. Everyone was their own paparazzi.

And I thought of Lady Gaga—born Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta, four to five years before the Bling Ring kids, in New York. She’d dropped out of college and hustled her way to superstardom. She often talked about how bad she’d wanted it. “In the book of Gaga,” she said in an interview, “fame is in your heart, fame is there to comfort you, to bring you self-confidence and worth whenever you need it.” In Gaga’s world, she was a prophet of fame and fame was a kind of god.

I drove up into the hilly streets of Calabasas, which were lined with lavish homes, some so big they looked like hotels, resort hotels, with enormous driveways and burbling fountains. I gave myself a tour. There were faux Colonial McMansions and Tuscan McMansions, each one like a different theme park attraction. “Living out here is sort of like living at Disneyland,” said a kid in the teenager-produced video, Calabasas: Behind the Glamour, which I’d watched on YouTube. “It’s not like real life.” (In the same video, the kids try and trick Calabasas residents into being mean to a fake homeless person, but they only catch one trying to shove money at him.)

And then there were streets with smaller homes—modest ranch-style ones and Spanish-style ones that looked like the humbler, distant cousins of the opulent spreads. I remembered a line from Double Indemnity (1944), one of my favorite films, where Fred MacMurray says in voice-over, “It was one of those California Spanish houses everyone was nuts about ten or fifteen years ago.” Prugo’s house, on a narrow canyon road, had a wistful look. The lawn was in need of attention. I parked across the street and stared at it awhile, waiting to see if anyone would come out of it. The Bling Ring kids had apparently done the same thing—sat and observed their targets’ homes, scoping for Intel on how to get in and rob, and maybe hoping to catch a glimpse of a star.

On September 17, the LAPD had swarmed Prugo’s house and searched for items belonging to celebrities. They found “several pairs of designer sunglasses, luggage, and articles of clothing.” Prugo denied any involvement in the burglaries at that time. His mother, Melva-Lynn, watched as police led him away in handcuffs. Melva-Lynn ran a dogwalking service. She was from Idaho. Prugo’s father, Frank (or like his son, Nicholas Frank), who was originally from the East Coast, was a senior vice president at IM Global, a film and television sales and distribution company. Founded in 2007, IM Global had handled the international rights for Paranormal Activity—a “supernatural shockumentary” about a couple being haunted in their bedroom at night by a menacing presence. The film would go on to become the most profitable movie of all time, based on return on investment. With a budget of $15,000, it grossed nearly $108,000,000 in the United States and close to $200,000,000 worldwide. It was released on September 25, eight days after Prugo’s arrest. Prugo’s lawyer, Sean Erenstoft, told me Prugo’s father seemed upset that his son’s legal troubles were overshadowing his success.

“He’s having the best year of his life,” said Erenstoft. “Mr. Prugo is completely distraught. He is concerned about his son, but he said, look, my name is Nicholas Frank Prugo and that’s my son’s name too.”

The younger Prugo had been in trouble before. In February 2009, he’d been arrested for possession of cocaine. He’d pleaded guilty and entered an 18-month Deferred Entry of Judgment program, a kind of drug treatment program that allows the offender to avoid a criminal record. TMZ had posted a video, taken off that same allegedly stolen computer, of Prugo sitting at his desk in front of the computer smoking weed and singing along to the Ester Dean dance hit “Drop It Low” (“Drop it, drop it low, girl”). The bedroom behind him is Everyboy’s room, sneakers strewn across the floor. Prugo gazes at his image onscreen, cocking his head this way and that, making “sexy” faces, checking himself out. Inspired, he gets up and lifts up his shirt, showing off his bare midriff. Then he turns around and does a booty dance for the camera. It was like an updated, computer literate version of Tom Cruise’s underwear dance scene in Risky Business (1983).

Then the phone starts to ring and Prugo answers it, demanding in a jocular tone, “Why are you ruining my life? I don’t really want to….” Watching it, I wondered if he were talking to Rachel Lee and she was inviting him out to a burglary.

After a while I drove on to Rachel’s house. She lived on the west side of Calabasas, not far from Agoura Hills, in a development bounded by a couple of two-lane highways. The house was large and boxy, like the cookie-cutter homes on Weeds. (In fact, the satellite picture from the show’s opener for seasons 1 through 3 was a shot of Calabasas Hills, a gated community in Calabasas.) On September 17, the LAPD had served a warrant here, too, but Rachel’s mother told police that Rachel had moved to live with her father in Las Vegas. You had to wonder if she was running.

Rachel’s mother, Vickie Kwon, was reportedly a North Korean immigrant—an unusual thing to be, since North Korea has strict emigration laws—and the owner of a couple franchises of the tutoring company Kumon. It was “the world’s largest after-school math and reading academic enrichment program,” according to its website. Kwon sounded like an immigrant success story, which no doubt made it awkward for her that, while she was helping other people’s children excel academically, her daughter had been kicked out of Calabasas High School for disciplinary problems and transferred to Indian Hills. In July 2009, Rachel had been arrested for shoplifting makeup at a Sephora in Calabasas and sentenced to a year’s probation. On October 22, she was arrested at the Vegas home of her father, David Lee, a businessman.

I drove on to Diana Tamayo’s residence, an unremarkable-looking apartment building near a freeway in Newbury Park, about fifteen minutes west of Calabasas. Tamayo shared a two-bedroom rental unit with her parents and two younger brothers. Her parents had been described to me by a cop on the case as “hardworking illegals” from Mexico. Her mother, Aracely Martinez, was a swap meet vendor. Tamayo drove an expensive car, a Navigator.

In her bedroom, police said they found “several items allegedly belonging to celebrities,” including Hermes, Chanel and Louis Vuitton bags, Paris Hilton brand perfume, and four pairs of designer heels. After being arrested on October 22, Tamayo spent four days in jail until her family could raise her $50,000 bail. The LAPD discovered her to be an undocumented immigrant, exposing the illegal status of other members of her family. (She’d come to the United States when she was six; her brothers were born here.)

She’d been class president at Indian Hills and earned a $1,500 “Future Teacher” scholarship after graduating in 2008. A teacher had called her a “spectacular student.” She’d been named “Best Smile” in the 2007 yearbook and voted, along with her boyfriend Bobby Sanchez, “Cutest Couple.” According to my cop source she was “best buddies with Rachel.” They were arrested shoplifting together at Sephora in July, and Tamayo had also been sentenced to a year’s probation.

Courtney Ames lived in a small but centrally located Calabasas home on a climbing mountain road. There was a lone rocking chair on the bare white front porch, which seemed like a failed attempt at coziness. I’d heard her stepfather was Randy Shields, a former U.S. Amateur Light Welterweight boxer who beat Sugar Ray Leonard for the National AAU title in 1973. I’d watched a YouTube video of Shields going 12 rounds with a powerhouse named Thomas Hearns, another former welterweight champion, in 1981. Howard Cosell, who’d announced the fight, said, “As you look at that kid you have to give him all the credit in the world,” watching a bloodied Shields being led away after the fight. Now Shields sometimes worked as a bodyguard. In 1994, he’d told the Los Angeles Times he wrote screenplays in his spare time.

Ames had graduated from Calabasas High in 2008. That same year, she was arrested for allegedly fighting with a co-worker. She pleaded guilty to the lesser charge of disturbing the peace and was sentenced to 24 months probation. “She was always looking for trouble and always looking to fall into the wrong crowd,” one of her neighbors had told the Post. “People would make fun of her. She alienated herself on purpose.” She drove an Eclipse, a gift from her stepfather, who “bought her everything,” a source told The Daily Beast.

In 2009, Ames was arrested for D.U.I. and sentenced to community service. Making light of paying her debt to society, she’d posted on her Facebook page: “Cal trans”—the state agency responsible for road maintenance—“at 5 am you can all look for me on the side of the road ill be in that hot orange vest picking up [after] all you dirty motherfuckers.” She was arrested at home on October 22 in connection with the Bling Ring burglaries.

It wasn’t clear yet how she knew the other suspects, but she knew Roy Lopez from a former job. In 2008, Ames worked as a waitress at a local Calabasas bar and restaurant, Sagebrush Cantina—a rowdy pizza-margaritas-and-burgers joint with live music and Harley-Davidsons parked out front. Lopez was a bouncer there. He was essentially homeless, my cop source said: “He lives on people’s couches. He’s the only person who ‘needed’ to steal.” He had a minor juvenile arrest record, but had never been convicted of a crime. “A review of Lopez’s criminal history reveals that he is a Pinnoy Boys gang member who uses the street name of ‘Bugsy,’ ” said the LAPD’s report on the Bling Ring case. (Lopez’s lawyer, David Diamond, denied his client had any gang affiliation.)

“While this activity started as a twisted adventure for Prugo and his small group of friends fueled by celebrity worship,” the LAPD’s report said, “it quickly mushroomed into an organized criminal enterprise and—inevitably—the introduction of hard-core criminals, such as Jonathan Ajar and Roy Lopez.” (Diamond called this characterization of his client “wrong.”)

Lopez was arrested on October 22, along with all the others in the Bling Ring sting, after being located sitting in a car at a stoplight by a police surveillance team. “Is this about the Paris Hilton thing?” he spontaneously inquired, according to LAPD Officer Brett Goodkin.

Finally, I drove by the home of Alexis Neiers in Thousand Oaks, about 20 minutes west of Calabasas. Thousand Oaks is another prosperous bedroom community that has basked in the light of many local stars, including Heather Locklear, Sophia Loren, and Wayne Gretzky. Neiers’ home was on a rolling road with a cul-de-sac, flanked by camouflage-colored hills. It was a two-story, yellow stucco house with a tile roof and a lot of foliage around the front porch. Andrea Arlington Dunn, Neiers’ mother, was a former Playboy model, sometime masseuse and holistic health care practitioner. She was married to Jerry Dunn, a television production designer who had worked on Disney shows, including Hannah Montana and The Suite Life of Zack and Cody.

Neiers had been homeschooled. She had a little sister, Gabrielle, then 15. Neiers’ connection to the other burglary suspects was still unclear. On her MySpace page, she had described herself this way: “I am currently working as a full-time model and actress but in my spare time (when I have any haha) I am a Pilates, pole dance and hip-hop instructor.” Her father, Mikel Neiers, a director of photography on Friends between 1995 and 2000, told People, “[Alexis] was in the wrong place at the wrong time, associating with the wrong people. She got sucked into this. We’re standing by her. I’m sure [the case against her] is going to be thrown out of court.”

She had no criminal record except for a misdemeanor warrant for “Driver in Possession of Marijuana.” On October 22, she was arrested at home after police found a black and white Chanel necklace allegedly belonging to Lindsay Lohan and a Marc Jacobs purse allegedly owned by former star of The O.C. Rachel Bilson in her little sister’s bedroom.

(#u3ed3969d-b553-5c0b-ab7e-4362b5f4479d)

I headed over to the Commons, the snazzy local mall, hoping to run in to some teenagers who knew the Bling Ring kids or could offer some speculation about why they did it—which is what everybody wanted to know. Why would a bunch of kids who had everything risk everything to steal a bunch of famous people’s clothes?

But it was clear from driving by their homes that the kids weren’t as rich as everyone seemed to want to believe. Everybody wanted them to be the like kids on Gossip Girl, but it seemed they lived more like typical teenagers. They were better off than many kids, at the dawning of the Great Recession; but they didn’t appear to be wealthy in the way of the new elite class that had been engaging in the deregulated accumulation of capital for the better part of three decades. They weren’t as rich as other people in Calabasas, or their victims, either. Which made them wannabes.

The first person I ran into at the Commons wasn’t a teenager, however, but Kourtney Kardashian, sister of Kim. “Looking good, Kourtney,” said a paparazzo in tow. Being in Calabasas was like having a strange dream where celebrities popped out from every corner, like funhouse clowns. Kardashian was very pregnant (with her first child with her boyfriend, former teen model Scott Disick) and wearing what appeared to be a small fortune in tight-fitting maternity wear. She was carrying a bag that cost about the same as many Americans’ monthly salaries. She was coming out of the mall entrance laden down with shopping bags. Her lip gloss glimmered in the sunlight.

Later, I would learn that Kardashian’s Calabasas home had been robbed on October 18, 2009, and that the burglary bore all the marks of a Bling Ring job. Except for Prugo, none of the kids in the gang had been arrested at the time of the heist. One-hundred-eight-thousand dollars in diamond jewelry, Rolex and Cartier watches had been stolen. Cops were never able to put any of the Bling Ring kids at the scene, but they suspected a connection (and still do; the culprits in that burglary have never been apprehended).

“It’s boring here,” said the girl in Starbucks. “There’s nothing to do. A lot of people drink.” Now I was sipping sugary coffee drinks with three teenagers, two girls and a boy. They asked me not to use their real names; they said they could speak more freely that way. I’ll call them Jenny, Justin, and Jill. They were recent graduates of Calabasas High School, all attractive and fit and sporting bright, sporty gear. They were enrolled in a local two-year college, Pierce, in nearby Woodland Hills.

“A lot of people around here get D.U.I.s,” Justin said.

They talked about knowing Courtney Ames and hearing about her recent D.U.I. “I heard her blood alcohol level was point-thirty,” said Jenny. “You can die from that—or at least go unconscious.”

Ames’ Facebook page was full of partying bravado and references to drinking and getting high: “Beer pong, keg, the normal”…. “Wanna smoke a bluuunt.”

“I heard she was, like, a white supremacist,” said Jill. “People called her ‘White Power.’ She had tattoos all over her and was always listening to hip-hop and acting like she was some big gangsta chick.”

One of the arresting officers at Ames’ home on October 22 told me that in her bedroom he found notebook papers filled with numerous “generic white power kinda stuff. And the ‘n’ word.” When he asked her what this was doing there, he said she told him, “I was into that in high school but I’m not into it anymore.” (Robert Schwartz, Ames’ lawyer, had no comment.)

“She was always talking about going into Hollywood to party,” said Jenny.

“Most people don’t want to go into Hollywood,” said Jill. “We’re like in a bubble out here. We’re in a bubble.”

“People hang out at the mall,” said Jenny. “Hang out at Starbucks.”

“Go to Malibu or Zuma Beach in the summer. Go to the Promenade in Westlake,” said Jill.

“Make bonfires,” Jenny said.

I asked them if it was strange growing up in a community surrounded by so many celebrities.

“It is strange,” Justin said. “There’s a lot of people with money who think they’re better than everyone else. It’s the haves and have-nots.”

“They act like they’re, like, the people on The Hills,” said Jill. “They wear, like, three-hundred-dollar jeans.”

I asked them what they thought motivated the Bling Ring kids.

“Kids are very influenced by the media,” said Justin, looking thoughtful. “They’re constantly seeing movies and TV shows telling them a certain lifestyle is better, and if you don’t live that lifestyle you can’t be happy. You’re like a loser. So people want what they don’t have.”

“Everybody wants to be famous,” said Jenny.

“No,” said Jill. “Everybody thinks they are famous. I call it ‘FOF’—Famous on Facebook. It’s like they think they can just put themselves out there and don’t even have to work for it.”

I told them I’d just seen Kourtney Kardashian.

“We see them all the time,” said Jill. “They have really big butts.”

“I saw Britney at the gas station,” Jenny said. “Even though she’s gained some weight I still think she’s really cute.”

(#u3ed3969d-b553-5c0b-ab7e-4362b5f4479d)

When I got back to my hotel in L.A. that night I thought about what it must be like growing up in an America where everybody wanted to be famous. An awards show was on, the American Music Awards. I watched the stars gliding up the red carpet, and thought of Nick Prugo and Rachel Lee watching it, somewhere, transfixed. Then Jennifer Lopez was singing her song “Louboutins” (2009): “I’m throwing on my Louboutins … Watch this Benz/Exit that driveway….” I turned it off.

If the kids at the Calabasas Commons were right, then everybody not only wanted to be famous, but thought it was within their reach. It’s telling that the most popular show on television between 2003 and 2011—in fact, the only show ever to be number one in the Nielsen ratings for eight consecutive seasons—was American Idol, a competition program celebrating the attainment of instant notoriety. “This is America,” said Idol co-host Ryan Seacrest in 2010, “where everyone has the right to life, love, and the pursuit of fame.” As proof of this, Seacrest is also the executive producer of Keeping Up with the Kardashians.

The narrative of fame runs deep in American culture, dating back to A Star Is Born (1937) and beyond (arguably to the spread of photography in the 1850s and 1868’s Little Women—Jo wants to be a famous writer—which isn’t quite the same as wanting to be on The Real Housewives of Atlanta). But it’s safe to say there’s never been more of an emphasis on the glory of fame in the history of American popular culture. There are the countless competition shows (The X Factor, America’s Got Talent, The Voice, America’s Next Top Model, Project Runway); awards shows; reality television, on which even “hoarders” and “American pickers” can become famous. There are Justin Bieber and Kate Upton, self-made sensations through the wonders of self-broadcasting. Explaining the success of YouTube in 2007, co-founder Chad Hurley said, “Everyone, in the back of his mind, wants to be a star.” There’s the new 24/7 celebrity news industry exemplified by TMZ and gossip blogs. There’s the way in which even legitimate news venues have become infused with celebrity reporting.

Unsurprisingly, the massive growth of the celebrity industrial complex hasn’t failed to affect kids. To put it mildly, kids today are obsessed with fame. There’s already a fair amount of research about this—it seems we’re obsessed with how obsessed kids are with becoming famous. A 2007 survey by the Pew Research Center found that 51 percent of 18-to-25-year-olds said their most or second-most important life goal—after becoming rich—was becoming famous. In a 2005 survey of American high school students, 31 percent said they “expect” to be famous one day. For his book Fame Junkies (2007), author Jake Halpern and a team of academics conducted a survey of 650 teenagers in the Rochester, New York area. Among their findings: Given the choice of becoming stronger, smarter, famous, or more beautiful, boys chose fame almost as often as they chose intelligence, and girls chose it more often. Forty-three percent of girls said they would like to grow up to become a “personal assistant to a very famous singer or movie star”—three times more than as chose “a United States Senator” and four times more than chose “chief of a major company like General Motors.” When asked whom they would most like to have dinner with, more kids chose Jennifer Lopez than Jesus. More girls with symptoms of low self-esteem said they would like to have dinner with Paris Hilton.

Interestingly, kids who read tabloids and watch celebrity news shows like Entertainment Tonight and Access Hollywood are more likely to feel that they, too, will one day become famous. Girls and boys who describe themselves as lonely are more likely to endorse the statement: “My favorite celebrity just helps me feel good and forget about all of my troubles.”

The fame bug is more prevalent in industrialized nations than in the developing world. A 2011 survey by the ChildFund Alliance, a network of 12 child development organizations operating in 58 countries, found that a majority of children in developing countries aspire to be doctors and teachers—when asked about their top priorities, they talked about improving their nations’ schools and “[providing] more food”—while their counterparts in developed nations want to grow up to have the kind of jobs that will make them rich and famous—professional athlete, actor, singer, fashion designer.

Or for the less hardworking, there is burglar.

It occurred to me, while looking over the careers of the Bling Ring victims, that not only were they rich and famous, but nearly all of them had been in movies or on popular TV shows about people who were rich and famous or wanted to be rich and famous. They provided the burglars with an enticing image of fame within fame, imaginary wealth rewarded by actual wealth. There was a double mirroring with all their targets, as deliciously full of things that were bad for you as a double-stuffed Oreo.

There was Paris Hilton, whose “heiress” background was the premise for her reality show The Simple Life (2003–2007), in which she and her friend Nicole Richie invaded the lives of working-class people and made fools of themselves and their hosts. There was Lindsay Lohan, famous since the age of eleven, who had appeared in a movie, Confessions of a Teenage Drama Queen (2004), about a girl who is consumed with wanting to become a famous actress. And there was Rachel Bilson, who had starred on The O.C., about rich kids in Newport Beach, California. (Josh Schwartz, who created the show, now had another hit with Gossip Girl, about rich kids in New York.)

The Bling Ring had also burglarized the home of Brian Austin Green, who had starred in the 1990s teen drama Beverly Hills, 90210, about rich kids in Beverly Hills. Their real target in hitting Green was his girlfriend (now wife), actress Megan Fox, who had co-starred with Lohan in Confessions of a Teenage Drama Queen, playing a rich mean girl. Then there was Audrina Patridge of The Hills, a reality show about rich girls trying to find themselves in L.A. Spencer Pratt, another regular on the show, was apparently also a target, but the Bling Ring was busted before it had a chance to rob him.

Rachel Lee and Diana Tamayo allegedly fled from the home of High School Musical star Ashley Tisdale in July 2009 after encountering her housekeeper at the front door (Tisdale was in Hawaii). The High School Musical phenomenon hit when the Bling Ring kids were entering high school. The first installment in the three-part Disney franchise appeared in 2006. Although it was geared more toward tweens, no one could escape the hype, which made stars of newcomers Tisdale, Zac Efron, and Vanessa Hudgens (all three were Bling Ring targets, although none was ever successfully burglarized). The squeaky-clean movies, shot in squeaky-clean Salt Lake City, are about high school kids vying for roles in a high school musical, but their true message is about the thrill of fame. Tisdale’s character, Sharpay Evans, a spoiled rich girl seemingly modeled after Paris Hilton (she’s a platinum diva who carries a lapdog), announces she will “bop to the top” and have only “fabulous” things in her life. The final number of the first High School Musical movie declares, “We’re all stars.”

And then there was Miley Cyrus, another target on the Bling Ring’s list. Her wildly popular tween comedy, Hannah Montana, ran on the Disney Channel from 2006 to 2011. It was, famously, about a high school girl who lives a double life as a famous pop star. Miley the regular teen has dark hair, while Hannah the celebrity dons a platinum wig and flashier clothes. “You get the limo out front,” Cyrus sang in the show’s theme song. “Yeah, when you’re famous it can be kinda fun.” Hannah Montana attracted more 6-to-14-year-old viewers than any other show on cable, and 164 million viewers worldwide.

A study of the effect of celebrity culture on the values held by kids found that the TV shows most popular with 9-to-11-year-olds have “fame” as their number one value, above “self-acceptance” and “community feeling.” “Fame” ranked number 15 in 1997. “Community feeling” was number one in 1967. I searched YouTube for a typical episode of The Andy Griffith Show from that year, and found one that showed Aunt Bee fretting over the responsibilities of jury duty (and mind you, this show was a big hit). Meanwhile, a typical episode of Hannah Montana from 2009 has Hannah fretting over her overbooked schedule—how will she juggle a concert and a radio show? Or for older kids, there was a 2008 episode of Entourage in which Vince the movie star (played by Adrian Grenier) worries over whether he should take a part in a movie, and what it will do for his image.

But it may be too easy to blame pop culture and the media for promoting the “value” of fame. Movies and TV shows and popular music are often more of a reflection than an engine of cultural trends. I think when we talk about the obsession with fame, we’re also talking about an obsession with wealth. Rich and famous, famous and rich—they seem connected as aspirations. Interviewing teenagers over the years, I’ve often heard them talk about wanting to be famous, but almost always in the context of being rich and the “lifestyle” fame ushers in. “Lifestyle” is a word that comes up a lot. “We put them up in the nicest hotels,” said X Factor judge Demi Lovato of the contestants on the show, “because we want them to get a taste of the lifestyle that fame can bring them.” (Sadly for Lovato and also former X Factor judge Britney Spears, “the lifestyle” of fame has also included time in rehab, where they both landed in 2010 and 2007, respectively.) When the kids in the Starbucks at the Commons in Calabasas started talking about fame, they immediately started talking about money. It’s striking that while there seems to be much consternation about kids wanting to be famous, there seems to be little concern about them wanting to be rich.

America has always offered a dream of wealth; in “the land of opportunity,” anyone who is willing to work hard can make a good life for himself and his family. But the idea of what constitutes a good life hasn’t always included private planes and 50,000-square-foot homes and $100,000 watches and $20,000 handbags. We are living in a new Gilded Age, with a “totally new stratosphere” of financial success.* (#ulink_52d19180-d080-544d-9c95-c0c3a72ee720)

As we’ve become aware in the national conversation about the one percent, income inequality has increased dramatically since the late 1970s. Then, the top 1 percent of Americans earned only about 10 percent of the national income; now they earn a third. In terms of total wealth, they control about 40 percent. Meanwhile the 99 percent has been going into debt trying to keep up with the newly extravagant lifestyle the one percent inhabits.

“While the top 1 percent have seen their incomes rise 18 percent over the past decade, those in the middle have actually seen their incomes fall,” wrote Nobel Prize–winning economist Joseph E. Stiglitz in Vanity Fair in 2011. “All the growth in recent decades—and more—has gone to those at the top.” At the same time, Stiglitz wrote, “People outside the top 1 percent increasingly live beyond their means. Trickle-down economics may be a chimera, but trickle-down behaviorism is very real.”

When rich people started having more money—a lot more money—they started coming up with bigger and fancier ways of spending it. The explosion in demand for high-end consumer goods has been called “the luxury revolution,” although it’s anything but revolutionary. Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities (1987) was a scathing look at the materialistic (and ultimately criminal) culture created by Wall Street players like his main character, Sherman McCoy. But while yuppies might have been portrayed as loathsome in movies like Wall Street, they had stuff, and their stuff was coveted. A bemused Michael Douglas said in a 2012 interview that young men routinely come up to him and say, “Gordon Gekko! You’re my hero! You’re the reason I went to Wall Street!”—as if Wall Street were an inspirational film rather than a cautionary tale about a financial crook.

Greed was suddenly good, so was shopping. In the wake of 9/11, then President George W. Bush elevated it to a patriotic act. (“Some don’t want to go shopping,” after the terrorist attack, Bush said. “That should not and that will not stand in America.”) Carrie Bradshaw of Sex and the City became our lovable over-spender, trolling for Manolos she couldn’t afford in between too many cosmopolitans. The show, which ran from 1998 to 2004, and could be credited with mainstreaming a familiarity with designer brands, became very popular among tween and teenage girls, who took to showing off their hauls from shopping expeditions in online “haul vlogs.” Who Wants to Be A Millionaire? (1999–2013) another popular show asked. Well, who didn’t? “Everyone wants to be rich,” said David Siegel, the private timeshare mogul profiled in the documentary The Queen of Versailles (2012). “If they can’t be rich, the next best thing is to feel rich.”

By the 1980s, there weren’t songs on the radio anymore about loving your fellow human beings. “Come on, people now, smile on your brother, everybody get together, try to love one another right now,” sang the Youngbloods in 1967. “People all over the world, join hands, start a love train,” crooned the O’Jays in 1973. Now there were songs about loving yourself—and stuff. There was Madonna singing about being “a material girl,” “living in the material world.” There was Puff Daddy, in the 1990s, rapping, “It’s all about the Benjamins, baby.” In 2008, the R&B group Little Jackie proclaimed, “The world should revolve around me.” Jay-Z goes by the nickname “Hova”—as in Jehovah—and calls himself “the eighth wonder of the world.” The shift in values could be seen on television, too. There weren’t shows about poor families anymore, like Good Times (1974–1979) or The Waltons (1972–1981)—there were shows about rich people, Dynasty (1981–1989) and Dallas (1978–1991) and, of course, Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.

Lifestyles had a long run, from 1984 to 1995, and its impact was enormous. Now regular people could see what it was like to be rich from the inside—and they wanted it. “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous” (1996) by rappers Kool G Rap and DJ Polo, trumpeted the delights of having a “yacht that makes the Love Boat look like a life raft.” Quite a change from the Intruders’ 1974 anthem, “Be Thankful for What You Got.”

When I got a chance to talk to Nick Prugo and asked him why he thought Rachel Lee was so obsessed with their famous victims that she would steal their clothes, he said, “I think she just wanted to be part of the lifestyle. Like, the lifestyle that everybody kind of wants.”

* (#ulink_f78470ae-48d1-5fda-838e-024e2d41db1f) See Chrystia Freeland, Plutocrats: The Rise of the New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else (Penguin 2012).

(#u3ed3969d-b553-5c0b-ab7e-4362b5f4479d)

When you drive up to the address of Indian Hills, the first thing you see is another school, Agoura High; the two schools share a campus. Agoura is a bustling, idyllic sort of American high school, very proud of its Chargers football team. It sits in a large tan brick building with a parking lot full of luxury cars, shiny BMWs, Audis, and SUVs.

Indian Hills, which has less than 100 students, resides at the back, in several prefab buildings, like the ones used as offices at construction sites. It has as its logo the uncomfortable image of an Indianhead, and, hidden at the back of the compound as it is, it has the feeling of being stuck on a reservation.

The two girls I met in the parking lot were seniors at the school. They said they’d rather not use their real names, as they “didn’t want to get involved.” They chose the names “Monica” and “Ashley.” They were wearing low-slung jeans, tight long-sleeved Ts and a lot of dark eye makeup. Monica was smoking.

We went and sat on the bleachers of the playing field, which was empty except for a couple boys running around the track. Monica said she was sent to Indian Hills for “drugs”; Ashley because “I have trouble learning.”

“She was toootally into herself,” said Monica.

“Oh, I liked Rachel,” said Ashley. “She could be sweet.”

Monica raised an eyebrow. “Sweet? You mean mean,” she said.

They said they knew Rachel Lee, Nick Prugo, and Diana Tamayo, having gone to school with the older kids before they graduated in 2008. “Everybody knew what they were doing”—that is, burglarizing the homes of celebrities, said Monica.

“They bragged about it. At parties and stuff,” said Ashley.

“Most people didn’t believe it,” Monica said. “People thought they were just talking shit.”