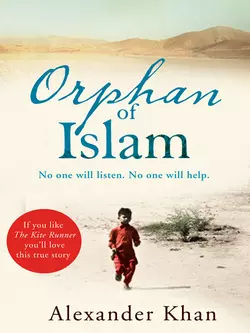

Orphan of Islam

Alexander Khan

“I've told you before, and I will tell you again, if you are unable to read the Holy Book you will be punished.” The teacher’s face was a mask of anger. “Understand?”Born in 1975 in the UK to a Pakistani father and an English mother, Alexander Khan spent his early years as a Muslim in the north of England. But at the age of three his family was torn apart when his father took him to Pakistan. Despite his desperate cries, that was the last he saw of his mother – he was told she had walked out and abandoned them; many years later he learned she was told he’d died in a car crash in Pakistan.Three years on Alex is brought back to England, but kept hidden at all times. His father disappears to Pakistan again, leaving Alex in the care of a stepmother and her cruel brother. And it is then that his troubles really begin. Seen as an outsider by both the white kids and the Pakistani kids, Alex is lost and alone.When his father dies unexpectedly, Alex is sent back to Pakistan to stay with his ‘family’ and learn to behave like a ‘good Muslim’. Now alone in a strange, hostile country, with nobody to protect him, Alex realises what it is to be truly orphaned. No one would listen. No one would help. And no one cared when he was kidnapped by men from his own family and sent to a fundamentalist Madrassa on the Afghanistan border.A fascinating and compelling account of young boy caught between two cultures, this book tells the true story of a child desperately searching for his place in the world; the tale of a boy, lost and alone, trying to find a way to repair a life shattered by the shocking event he witnessed through a crack in the door of a house in an isolated village in Pakistan.

Orphan of Islam

No one will listen. No one will help.

Alexander Khan

Dedication

I dedicate this book to Abad.

Without his help I would not be here.

And to my wife Jessica –

I love you very much.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Map

Author’s Note

Prologue

The mullah bends down, his long grey-black beard brushing agains…

Chapter One

I see a face, a white face, but I don’t…

Chapter Two

We were met at Heathrow by a gaggle of relatives…

Chapter Three

After ten months at Fatima’s I’d become used to Dad…

Chapter Four

We arrived at Hamilton Terrace to find the house deserted.

Chapter Five

In Dad’s absence Rafiq appeared to make himself useful, at…

Chapter Six

I was about 15 feet up, but it felt like…

Chapter Seven

All that flight I kept checking to see if I…

Chapter Eight

The next few days were spent exploring my immediate surroundings.

Chapter Nine

The group that gathered for our farewell to Pakistan wasn’t…

Chapter Ten

After prayers we trooped back to the sleeping quarters. The…

Chapter Eleven

I lay awake most of that night, pain and worry…

Chapter Twelve

I pestered Abad several times to tell me what he…

Chapter Thirteen

The village of small mud houses that lay at the…

Chapter Fourteen

The journey was long, two or three hours, and I…

Chapter Fifteen

I woke to the sound of the early morning call…

Chapter Sixteen

Malik wasn’t the only rebel kid in the village. There…

Chapter Seventeen

One afternoon, 10 days or so before Fatima and Ayesha’s…

Chapter Eighteen

There was a minibus waiting at Heathrow to take me…

Epilogue

I’m standing on the doorstep of a council house near…

Acknowledgments

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Map

Author’s Note

I hope my story is inspirational for those who might find themselves in similar situations and think there is no hope and no way out. There is always a way out, even when the odds are stacked against you and the wall seems very high.

I’ve been there, scared, not knowing who to ask for help. It’s not a nice feeling.

www.alexander-khan.co.uk is a website that offers confidential help and advice to people in similar situations to those described in this book.

Prologue

1988. HAQQANIA MADRASSA, NORTH-WEST PAKISTAN

The mullah bends down, his long grey-black beard brushing against my feet as he unlocks the leg brace. I’ve been standing rigid in it for at least three hours, unable to sit, kneel or even squat for fear of snapping my ankles. I could cry with relief, but I’m too frightened to cry. At least not yet.

He points to the blackboard in front of me with his bamboo stick, the one he uses to whack us all with when we can’t pronounce something from the Holy Book. My Arabic is rubbish; I’m very used to that stick.

‘Read it,’ he commands, glaring at me with dark eyes.

All the lights have gone out across the madrassa and the only illumination in the room is a lantern with a tiny wick. I read the chalked scripture slowly, trying to pronounce all the words right:

‘La ilaha illallah Muhammad rasul Allah’ (‘There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is His Messenger.’)

Whack! The stick comes across my shoulders. Wrong again. Hearing Arabic spoken is one thing, trying to read it quite another, and my northern English accent easily wins out. The mullah glares at me with undisguised contempt.

‘Go back to your room,’ he says. ‘We’ll see each other in here again tomorrow. You’re a disgrace to Islam.’

I stumble through the darkness to the dormitory and feel my way across the room to my blanket. Most of the boys are sleeping. I lie down and start to cry, as quietly as I can. The question goes through my mind, the same question that nags me night and day: how the hell have I ended up here? An ordinary lad from Lancashire stuck in some kind of weird medieval fairy story, but with no sign of a happy ending …

Back home, my mates are secretly listening to Bros or Guns n’ Roses in their bedrooms, hoping their dads won’t catch them and send them for an extra session of prayer at the mosque. That is as bad as life gets for them; why have I been singled out for such harsh punishment so far from home? What have I done to deserve this?

Chapter One

I see a face, a white face, but I don’t recall any features other than dark eyes and a smile. What I remember most is her long dark hair. As she bends down, it tickles the sides of my cheeks and I laugh. She laughs too, then the sun comes out and streams through the thin curtains of the living room. She turns away and is gone. This is the only memory of my mum I have from childhood.

I’ve no idea what she was like as a mother during those brief first few years. I can’t recall the stories she told, the food she cooked, the games she played or even the sound of her voice. There is no scent in this world that evokes her smell, no object or place that brings back those precious moments in time. Dark hair and a white face are all I have, and while that hasn’t been much, it has been enough to hang on to in my worst moments. I always knew she was out there somewhere, even when she’d apparently vanished from the face of the Earth. All I wanted was her to come back and take us home.

What I know about Margaret Firth is what I’ve pieced together over the years and what I’ve learned more recently. She was born near Manchester, the youngest of three sisters living in a house of poverty and pain. Her parents had little time or regard for her. Although she looked up to her sisters, it wasn’t the easiest of relationships. When her elder siblings moved out and made lives for themselves she would go to live with them from time to time, returning to her parents’ home when they’d had enough of her. It was a lonely life, back and forth between people who didn’t really want her. Her parents worked in the textile industry. Margaret would eventually do the same, getting a job in a local mill as soon as she left school.

My father, Ahmed Khan, was born in the village of Tajak, in the Attock district of north-west Pakistan. It is a rural and deeply religious area not far from the North-West Frontier and the border with Afghanistan. Ahmed was the eldest of five siblings: three brothers and two sisters. For the first 30 or so years of his life he lived pretty much how people have lived in this area, close to the Indus river, for many years. The men rise before dawn and go to the mosque for prayers. They return home to walled compounds containing several houses occupied by members of the extended family. Their wives are already up and have prayed in their living rooms on a mat facing Mecca. Then it is into the kitchen to cook curry and chapatis. The food is placed in a small clay pot with a lid on and given to the men as they head out for a day working in the harat, or field. Each family has its own plot of land, irrigated by a large well and including a small brick hut containing tools. Many men spend their entire lives in this routine, their faces etched with deep lines by the sun. Others become drivers or co-drivers of the trucks and buses that travel ceaselessly across Pakistan and beyond. Some turn into mechanics and set up their own garages; others open grocers’ shops. In these rural villages the women just stay at home, raise children and keep house. They are not allowed to do much else.

But even in these insular communities there are men who seek something else. My father was one of them. His eldest sister, Fatima, had travelled to England with her husband, Dilawar, and set up a shop in a mill town in Lancashire. Letters came to Ahmed telling of a wonderful island where the sea was close by and earnings were three, four and five times the amount they were in the village. Fatima revelled in her status as an emigrant adventurer and encouraged her older brother to follow suit.

In the late 1960s the only way for a poor Pakistani to travel to England was by road. It was a 25-day journey across difficult terrain and through inhospitable countries. Dad made an attempt but was delayed in Karachi and his money ran out. It didn’t put him off; he went home, saved up and within a year tried again. This time he succeeded and, after spending time earning money on construction projects in Germany, arrived in England just before the end of the 1960s, with many other Pakistani, Indian and Caribbean immigrants.

Dad went straight up to Lancashire and to the Hawesmill area of the town his sister was living in. Hawesmill was built in the late nineteenth century to house large numbers of mill workers cheaply. Streets lined with stone-built terrace houses stretched for hundreds of yards up steep, windswept hills, forming a tightly-knit enclave that seemed forbidding to outsiders. By the time Dad arrived, many of its white inhabitants had gone for good. Cotton was no longer a major industry in Lancashire – although some mills were still working – and Hawesmill’s rundown old housing had almost served its purpose. But not quite, for a new set of people had moved in, and were finding the natural insularity of the place to their liking. Bengalis, Punjabis, Sindhis and Pathans were making Hawesmill their own, laying down roots and traditions founded in far-off villages. To the rest of the town, they were just ‘them Pakis’.

My father was a Pathan, one of a light-skinned and tall race of people who originate from Afghanistan and north-west Pakistan and speak Pashto. They were part of the Persian Empire and throughout history were known to be fierce warriors, defeating everyone who dared invade their lands, from Alexander the Great to the Soviet Union. As we know, they are still fighting today and are a strict, unyielding and deeply religious people. That said, they are also warm and if you befriend a Pathan, it’s for life.

Fatima was keen to help out her brother and persuaded her husband that he should have a job in his shop. Dad worked there for a while, but the wages were low and it was a matter of pride that he sent money back to the family in Tajak. He left the shop and found a job in a mill in Bolton that took on immigrants prepared to work for lower wages than white people.

He lived in a terrace house with four other men, all Pathans from the same area, and they hot-bedded: when one was on a night shift another would sleep in the bed, then vacate it to go to work when the night worker came home. If there was a time when they were all together, they would sit in the front room of the house, smoke cigarettes and play cards and talk about work and how they missed Pakistan. They would only go home, they declared, once they’d made enough money to build a house in their village. In winter they would pull worn-out second-hand coats over their traditional salwar kameez clothing when they went outdoors and learn not to moan too much about the wind and rain coming in off the bleak moors. Lancashire wasn’t home, and would never be, but when they talked and listened to Pathan music, home didn’t seem so far away. ‘Only a few more years,’ they’d promise themselves before heading off to the mosque – a couple of terrace houses knocked into one. Men from all over Hawesmill would squeeze into it five times a day. This was the reality of Dad’s adventure in England, day after day after day.

No wonder, then, that his curiosity was aroused when a young Englishwoman caught his eye during his shift at the mill. He didn’t know any white people and he couldn’t speak much English. He saw no reason to mix; from what he’d heard, whites didn’t like Pakistanis ‘coming in and taking all the jobs’. But this woman seemed different. She smiled at him, and it was genuine. Shyly he looked away, then back again. She was still smiling.

‘Hiya,’ she said, ‘what’s your name?’

He shrugged, not understanding. But a Bengali friend working on the same shift could speak half-decent English and caught the question.

‘Hey,’ he said to Dad, ‘the girl’s asking your name. Aren’t you going to tell her? She’s a pretty one. Go on, tell her …’

Dad smiled, but said nothing. Farouk leaned round the spinning loom and shouted to the girl, ‘It’s Ahmed … Yeah, Ahmed. He likes you. Talk to him.’

Margaret Firth, 18, lonely and lacking confidence, liked her Asian co-workers. They seemed quiet and dignified, never complaining like the local Bolton lads or drinking and messing about. She appreciated how respectful they were when they spoke to her. And there was something she really liked about Ahmed, even if he couldn’t hold much of a conversation.

Dad was a village boy, but he wasn’t daft. He’d made it to England, found work and was sending money home. He missed Pakistan, but he certainly didn’t want to go back. Not yet. What better way to stay than to marry an Englishwoman? It would give him residency and maybe take him out of Hawesmill altogether. The idea of marrying someone from a non-Muslim background would horrify his sister and the Pathan communities in both Hawesmill and Tajak, but no matter. He would bring her into Islam, and Fatima would teach her the ways of Pakistani women. It would be fine.

Now, I don’t really know if this was the case or not. Perhaps Dad got together with Mum out of love. He certainly liked her enough to introduce her to the family in Hawesmill, braving the stares and whispers that she must have attracted. Mum seemed happy to go along with whatever he wanted. For the first time in her life she’d found someone who treated her with kindness and respect. She was young and impressionable. The language, the clothing, the customs and the cooking all baffled her at first, but when Dad asked her to live with him in a rented terrace house she agreed immediately. They had a formal nika, or engagement ceremony, performed by the local imam. She dressed the way Dad wanted and learned to cook the food he liked. He tried to improve his English. Maybe they would be alright.

Dad’s sister didn’t think so. Fatima was against the relationship from the start and was horrified when they set up home together. It was haraam, strictly forbidden in Islamic law, and a source of dishonour. Fatima was a pioneer, the first of her family to live in England. Her word was law. Ahmed was bringing shame on her and Dilawar around Hawesmill. Again and again she begged him to leave the Englishwoman. Dad was having none of it. Mum’s parents didn’t want anything to do with her, so they eloped to Scotland, where there were jobs waiting for them in a textile mill in Perth, and finally married up there.

I was born on 22 February 1975 and named Mohammed Abdul Khan. My sister, Jasmine, was born in March the following year. Dad was now the father of two British-born children and was entitled to stay in the country for as long as he liked.

What happened next is unclear. There are stories of Dad starting to get a taste for whisky – also completely haraam under Islamic law. Never having drunk alcohol in his life, he became aggressive. I’ve been told he started hitting Mum while drunk. Perhaps he found being married to a Westerner and fathering two children with her much harder than he had expected. Maybe he missed Hawesmill or even Tajak.

What I do know is that within a relatively short space of time, the four of us were back in the north-west of England. Mum and Dad rented a house in Bury, picking up jobs in what remained of the rapidly declining textile industry. Dad seemed pleased to be closer to his family again, but his happiness wasn’t shared by Mum. Fatima was now openly hostile towards her, shunning her when we went to visit and speaking in Pashto to confuse her.

Dad was the source of more grief. He’d stopped drinking, but was now disappearing from the house for days and even weeks on end. ‘Family business at home,’ Mum was told. In this case, ‘home’ meant Pakistan. Without explanation or apology, Dad would just pack a suitcase and go. Mum would be left with two children in a damp, rented terrace house, with no idea when he would come back.

One morning in desperation she put us in the pram, got the bus to Hawesmill and walked up the steep street to Fatima’s house, determined to find out what her husband was up to.

‘Is he here?’ she demanded, as Fatima opened the door. ‘Or is he back in Pakistan? I’ve got two little kids here who miss their dad. I know you don’t like me. But I’ve a right to know what’s going on.’

Fatima paused. She had no time for this kuffar, this unbeliever, who had brought shame on her. But she felt that she was entitled to an explanation. Maybe if she heard the truth, she would disappear very quickly. She invited Mum to come in and sit down.

‘You should hear this from Ahmed, not me,’ said Fatima. ‘But since he’s not here I may as well tell you – the reason he goes to Pakistan all the time is because of his family.’

‘I know that,’ said Mum. ‘But if he’s so desperate to see his mum and dad, or his brothers, sisters, aunties, cousins, whoever, then why doesn’t he just bring them over here for a visit?’

Fatima smiled. The poor woman was clueless.

‘Not that sort of family,’ she said. ‘Ahmed has a wife in Tajak. He married her before he married you. Oh, they’ve got a few children too.’

I wonder what Mum thought as she wandered in a daze back to the bus station that day, the hems of her badly fitting salwar kameez trousers trailing through puddle-strewn cobbled streets, with two scruffy mixed-race kids crying in the pram. Meanwhile, somewhere hot, somewhere she’d never been invited for now obvious reasons, Dad was enjoying the fruits of his labours with the family he’d kept secret from her.

I was too young to remember the row that took place when Dad finally got home. It must have been one hell of a ding-dong. I imagine Mum screwing her Asian clothes up into a ball and throwing them at him, then telling him to cook his own bloody lentil dhal. It sounds almost comic, like a scene from East Is East, but it must have been awful. However it was conducted and whatever was said, the upshot was that Dad moved out of our house and into Fatima’s, leaving Mum with custody of the pair of us.

Now I believe Fatima acted maliciously by telling Mum the truth about Dad. She wanted to split them up. But in a way Mum had what she wanted – two beautiful children to care for and love as she had never been loved. She didn’t have to fit in with foreign customs anymore or cook funny food. She had a roof over her head and a job. There were people saying, ‘Told you so,’ but she didn’t care. I’d like to think that my first memory of her happened around this point: her smiling face turned towards me and the sun coming out.

‘Mohammed, oh my Mohammed …’ Do I remember her whispering that as she cuddled me protectively to her? Perhaps she did. At any rate, I’d like to think she was happy.

Dad still wanted to see us and would call round at weekends. Mum was still angry with him, but didn’t stop him from visiting. I guess he wouldn’t have taken us much further than the local park or the ice-cream parlour, and up to Hawesmill to see the family. Whether they wanted to see us would have been another matter, but knowing Dad he would’ve made sure that the family connections so important to Muslims were maintained, even if they included the children of an unbeliever.

One Saturday in the early part of 1978, just a few months after Dad and Mum had split up, he called for us as usual. He made sure we were dressed in our best clothes and also had a change of outfit. He explained to Mum that there was a family gathering in Hawesmill because a relative had flown in from Pakistan. We needed a change of clothes, he said, because we’d end up playing in the backyard and would get filthy. Mum packed us a little bag each, kissed us both on the head and saw us to the door. I guess we turned and waved to her as we climbed into the back of the battered old Datsun Dad always borrowed to pick us up. She shut the door, happy that she had a few hours to herself before we returned, tired out, after a long afternoon’s playing with the local kids in Hawesmill.

In the 1970s only lucky little English kids travelled on aeroplanes. Normally a family like ours would’ve been completely out of the international air travel league, but strong ties to Pakistan meant that money was somehow found to make the trip ‘back home’ and see relatives longing to hear stories about the land of opportunity that was giving such a warm welcome to its former ‘colonials’. I expect there was a whip-round in the streets of Hawesmill in the weeks before Dad came to pick us up from Mum’s. Whatever work Dad was doing at the time – shifts in the mill, plus a bit of labouring on the side – wouldn’t have paid for three airline tickets to Islamabad. That said, two of those tickets were one-way only, so maybe there was a discount. I don’t know – I’d just turned three and Jasmine was almost two. Babies, really – and far too young to be removed from their mother without explanation.

From what I can gather, the police were involved. I’d like to think that Mum banged on every door in Hawesmill for answers. She certainly did later on, until it became clear that she wasn’t going to get a straight answer out of anyone up there. But what were the police’s chances of making an arrest? An Asian man takes his mixed-race kids to Pakistan for a holiday and forgets to tell his estranged wife, a white woman who tried to fit in with the funny foreigners but wasn’t welcome – sounds like an open-and-shut case. Perhaps the police thought she had it coming to her, or maybe they did try hard to find us. But the trail would’ve gone cold as soon as we arrived in Islamabad, and I don’t think the law could’ve expected much help in Hawesmill.

We were taken to Tajak for a ‘holiday’ and put in the care of various ‘aunties’, some related, some not. Dad stayed for a while, a week or two perhaps, then went back to England. The need to earn money must have been overwhelming, because of course he had two families to support, so staying in Pakistan for any length of time wasn’t an option.

Meanwhile Mum made repeated attempts to track us down, without success. She must have been heartbroken, trailing those windswept terrace streets for her two missing children and begging Fatima for news of our whereabouts. What did they tell her – if anything? Many years later, I was told she had been informed by Dad’s family that we’d been killed in a car crash while on holiday in Pakistan, and that we’d been buried there. What a terrible thing to say to a mother, especially when it was a barefaced lie. Mum, poor and isolated from her own friends and family, could do nothing to disprove it. Luckily, she never believed it.

I can’t recall if I met my step-family at this time. It’s probable, given that Tajak is a small place, but being so young, I don’t have any memory of them. What I do remember is the day I was circumcised. Although it isn’t mentioned in the Qu’ran, circumcision (tahara) is a long-established ritual in Islam. It is to do with cleanliness and purification, particularly before prayer, and there was no reason why I would be exempted. Unfortunately for me, Mum had opposed this after my birth and Dad had no choice but to postpone it. Now she wasn’t around he could do what he liked, and one of his first jobs in Tajak was to find somebody suitably qualified to do it.

It goes without saying there was no anaesthetic. Dad would’ve rounded up the village imam, who also served as the village doctor, and a few of the elders, to oversee proceedings. I don’t recall their solemn bearded faces leaning over me as I lay on a scruffy bit of carpet in the village mosque, but I do remember the searing pain as the razor-sharp butcher’s knife cut through my little foreskin and my blood staining the carpet a deep red. Iodine must’ve been applied very quickly, as I remember looking down and seeing my genitals covered all over with a substance the colour of saffron. For days afterwards I suffered burning agony when I tried to pee. If I called out for my mummy at any time during those hazy, fractured few years, it would have been then.

My only other memory from this period is when I tried to shoot the moon. I’d found an old pellet gun in the house where we were staying and had been encouraged to take it outside and learn to use it. Having a gun in Pakistan is no big deal and boys handle weapons from an early age. Seeing an old shotgun propped against the interior wall of a house or an AK47 left in the corner of a mosque while its owner says his prayers isn’t uncommon. So the uncles of the family must’ve been delighted when I picked up the gun and lugged it outside. The moon was an obvious target. I’d never seen such clear skies in my short life; the sheer number and brilliance of the stars in the night sky was mesmerizing, and the moon hung in between them like a gigantic waxy-yellow fruit. I heaved the rifle to my shoulder, assisted by Jasmine, and took careless aim at the sky. No one had told me about recoil, so when I dropped it immediately after it went it off, the butt landed right on Jasmine’s foot, leaving her with a deep cut and a permanent scar.

We didn’t go to school during our time in Pakistan. Our family in England spoke Pashto among themselves, so it’s not as if we knew nothing of the language and couldn’t have managed to some extent in school. But I imagine the Pakistani relatives thought there was little point in sending us; we probably seemed happy enough, playing in the dust beneath the brick and mud walls of the houses or watching the farmers slowly gather in their crops under the vast and cloudless sky. The days were endless and dangers were few. My Pashto was certainly getting better, and after a year or so I could communicate with my cousins. If Dad hadn’t needed to earn money in England, maybe this is where my story would’ve ended. I’d have remained in Pakistan all my life, tending the fields or driving trucks or fixing cars or keeping a shop. In time the memories of Mum would’ve faded, and although I might never have fitted in – the gossip about the boy with the kuffar for a mother was unlikely to disappear – I’d have probably had an arranged marriage with a cousin and spawned a few kids. The opportunities to do anything other than conform would’ve been extremely limited. However, it might have been a much happier existence than the one that was waiting for me.

After spending three years in Pakistan, not knowing who we were or if we really belonged to anyone, we were taken back to England. That’s when my troubles really began.

Chapter Two

We were met at Heathrow by a gaggle of relatives who’d obviously relished the chance of getting out of Hawesmill for the day, even if it was just a boring trip down the M6 to London. What little baggage we had was crammed into the back of an ancient Ford Transit minibus and we were squashed in against our cousins. They sniggered and winked at one another whenever we spoke in fluent accentless Pashto.

I was jammed up against the window. It was December 1981. The minibus’s windscreen wipers waved monotonously the whole journey. It was only late afternoon, but already every headlight was on. England seemed cold, grey and dark. I shivered in my thin salwar kameez, wishing I had a nice parka with fur round the hood, just like my cousins had. The endless sun and long, lazy days seemed far away. The further north we travelled, the darker it got. It was like entering the mouth of a tunnel with no end in sight.

‘Where’s our house?’ I asked Dad. ‘Where are we going to live? Will Mum be there?’

Dad, sitting in the front passenger seat, turned round and exchanged a glance with Fatima, who was in the aisle seat opposite mine, her two youngest children curled up on her lap. She nodded, then stared at me wordlessly.

‘You’re going to live with Aunty Fatima for a while,’ Dad said. ‘Just while I get sorted out. It won’t be long before we have our own house. Aunty will look after you until then.’

‘But where will you be?’

‘I’m busy, Mohammed,’ Dad said. ‘You’ll both have to be patient. I’ll be around, off and on. You’ll be fine.’

‘So when will we see Mum?’

‘That’s enough questions!’ shouted Fatima, sitting upright and glaring at me. ‘We don’t know where she’s gone. So stop asking. You’ll be fine with us. Now go to sleep.’

Fatima turned away and pulled her two children closer to her. I traced my finger over the steamed-up window and made a small square that I could see out of. I felt very uncomfortable. Fatima had snapped at me just because I’d asked about Mum. It seemed clear that she wasn’t to be mentioned in her presence. But why? Adults were stupid, always telling you not to say this, not to do that. I drew a circle on the window and put in two dots for eyes and a straight line for a nose. I sneaked a look at Fatima, then drew a sad mouth. Already I hated her.

The Transit began a slow crawl from the town centre up to Hawesmill. My memories of this place were few; compared to the spacious compounds in Tajak and the vast fertile plains of the Indus Valley, Hawesmill looked small, cold and mean. Every house was the same. One street was no different from the next. The van bumped and slid over greasy cobbles before stopping outside a house three-quarters of the way up a long terrace row.

‘Here we are, kids,’ said Dad, smiling. ‘97 Nile Street. Welcome home. Come on, let’s get your stuff in.’

Dad grabbed our bags and gave a few notes to the driver. We stood shivering on the pavement. Snow was falling. I’d never seen white stuff dropping from the sky before and I was rooted to the spot with amazement.

Fatima was busy with her girls, Majeeda, who was 12, and Maisa, aged seven. Her nine-year-old boy, Tamam, banged on the door and shouted through the letterbox. Fatima pulled him away sharply, clipping him on his ear before rummaging in her bag for a key. Tamam winced and stared up at her like a beaten dog. Then he caught me looking at him and pulled his face into a snarl.

Fatima opened the door and pushed us all inside. We crowded into a narrow lobby, tripping over coats, bags and shoes. Tamam and Maisa bustled past Jasmine and me. Tamam gave me an extra shove as he passed.

‘Ayesha! Ayesha!’ Fatima yelled up the stairs. ‘Ayesha, come down now! Have you made the dinner? I can’t smell anything. Get down these stairs now!’

A teenage girl stuck her head round the top of the bannister rail and caught my eye. She winked and smiled. She plodded slowly downstairs, even as her mother screeched at her.

‘Hurry up, girl,’ Fatima said, ‘we’re all starving. I hope you’ve made something. Where’s your father?’

‘At the shop,’ she replied. ‘Where else? So … these are the little village kids. Haven’t they grown up? They’re really brown, too. You’d never think their mum was …’

‘Shut up!’ said Fatima fiercely. ‘Where’s the dinner?’

‘Made ages ago,’ came the surly reply. ‘It’s gone cold.’

‘Put the stove on then,’ Fatima said. ‘And leave a plate aside for your father. He’ll want something when he comes in.’

Ayesha took our hands and led us into the kitchen. ‘What’ve they been feeding you out there?’ she said. ‘Goat and more goat, I reckon. Come on, I’ve made some mincemeat with potatoes and peas. That’ll warm you up. Do you want a chapati while you’re waiting?’

We nodded, still trying to get used to the sound of Pashto underpinned by flat Lancashire vowels. Ayesha lit the hob and placed the cooking pot on top, then started singing in English.

‘Da da, da da, da da, da-da, tainted love, woah-oh, tainted love!’ She danced around the tiny kitchen, banging a spatula on the work surface to the rhythm of the song. We looked at her, wide-eyed in amazement. We hadn’t heard any music at all in Pakistan. No one ever sang or danced like this.

‘Guess what?’ Ayesha whispered. ‘I’ve got a radio in my bedroom. It’s true – Parveen in Alma Street lent it me. It’s got an earphone so no one knows you’re listening. I like the charts on a Sunday night. Do you like them too? What’s your favourite song? I like Soft Cell, Duran Duran, the Human League – all of them. You can have a listen if you want.’

‘Thank you,’ I said, not knowing what I’d agreed to.

‘It’s OK. Just don’t tell Mum. I’ll get done if she finds out …’

‘Finds out what?’ Fatima was standing at the kitchen door, glaring at her 15-year-old daughter. She must’ve been listening in when Ayesha was singing.

She turned to me. ‘What’s she been saying to you? Tell me.’

‘I dunno,’ I said, trying not to look at Ayesha. ‘I couldn’t understand it.’

‘Of course you couldn’t,’ Fatima said sarcastically. Then she pointed at Ayesha. ‘If I catch you singing that rubbish again, I’ll put you out of this house. Nice Pakistani girls don’t sing. Is that clear?’

Ayesha looked at the floor, then silently turned her back on her mother and stirred the contents of the pot.

‘Upstairs, you two,’ Fatima said to me and Jasmine, ‘and I’ll show you where you’re sleeping. It’ll be a squash, but you’ll just have to get used to it.’

The house was tiny: two rooms and a kitchen downstairs and two bedrooms and a bathroom upstairs. For a couple with one child, it would’ve been just about adequate. But not for two adults and seven children. Yasir, Fatima and Dilawar’s elder son, slept in the downstairs front room. He was due to get married in a few months and would then move out, but for the moment he was living at home and working in the family shop with his dad. Fatima and Dilawar slept in the front bedroom upstairs. The back bedroom was shared by Ayesha, Tamam, Majeeda and Maisa. And now there were two more occupants.

Fatima indicated Tamam’s bed. ‘You’re in there,’ she said, ‘and your sister can get in with Majeeda and Maisa. Yes?’

Jasmine pulled at my sleeve. ‘I don’t like it here, Moham,’ she said. ‘It smells funny. I don’t want to share a bed. Why can’t we go with Dad?’

‘Because you can’t,’ snapped Fatima in her shrill high-pitched voice. The tone of that voice, forever shrieking and shouting around that tiny house, would grate on me in the months ahead. Even now, if I close my eyes I can still hear it, like fingernails going down a blackboard.

‘This isn’t a hotel,’ Fatima continued, ‘despite what your father seems to think. Anyway, he’s not going to be around for a while, so I’m in charge. And in this house, what I say goes. Got it?’

We nodded meekly.

Fatima threw our pathetic little suitcases onto the beds. ‘Dinner will be ready in 10 minutes,’ she said, walking out of the bedroom. ‘Get your hands and faces washed now.’

That first evening in Nile Street was awful. Dilawar and Yasir knew we were coming to stay, but made no effort to make us feel welcome when they arrived home from the shop. All they wanted was their dinner, and they didn’t seem at all happy to have to share it with two new mouths on the other side of the table. But Dad was there, so they said nothing. Fatima was all smiles in front of Dad, reassuring him that of course she’d look after us and yes, we’d be fine staying there and the other kids would love to have two new people to play with. The sly looks and digs in the ribs we were getting from around that cramped table suggested otherwise. Only Ayesha seemed to understand how weird it felt for us to be back in England. She rubbed our heads and gave us extra little pieces of chapati when she thought no one was looking.

‘We might make a half-decent Pakistani wife out of you after all,’ commented Fatima, who had noticed the extra attention she was giving us.

When the meal was over, the men and a few of the children, me and Jasmine included, sat in the back room. Fatima, Ayesha and Majeeda stayed in the kitchen to clean up. The men lit cigarettes, sat back on the settees, which faced each other along two walls, and chatted among themselves. There was no TV set, so we played on the floor.

After a while, Dad stood up. ‘Time I was off,’ he said, looking at his watch.

He bent down and kissed us both.

‘Now, you two behave for your Aunty Fatima and Uncle Dilawar,’ he said. ‘I’ll be gone for a few weeks now. I’ve got some work on. Remember, be good. No playing up.’

He shook hands with Dilawar and Yasir and shouted a goodbye to Fatima. The front door banged and he was gone.

Again we were alone. With family, yes, but without the parents we needed and wanted to hold us, look after us, keep us safe.

The false smile Fatima had put on for Dad soon disappeared. The shrill tone was again present in her voice when she ordered us all upstairs to get washed and changed for bed. There were the usual bedtime moans and groans from her children, but Fatima was having none of it. We were hustled up the narrow staircase to the bedroom, Tamam and Majeeda leading the charge.

Majeeda was first into the bathroom, banging the door. Tamam stood outside, shouting and shouting for his sister to hurry up. In the bedroom, Maisa flung Jasmine’s suitcase on the floor and climbed onto the bed, stretching out her legs in a defiant display of ownership. Finally, Majeeda left the bathroom and got into bed, pushing Maisa against the wall. There was barely a ruler’s width of space for poor Jasmine. She looked at me with frightened eyes and I squeezed her hand. I was just as afraid, but didn’t want to let her know.

Tamam came into the room. He looked as though he’d rather share a bed with a crocodile.

‘Get in,’ he ordered, ‘and move right up. If you even breathe, I’ll boot you one!’

I did as I was told and squeezed myself as far as I could against the wall. I stared at the cheap torn lime-green wallpaper for as long as possible until the light went off. I was tired from the long flight and journey up from Heathrow, and soon fell asleep. Less than an hour later the light pinged on again. There was no lampshade, and the bare bulb seemed to penetrate every corner of that tiny claustrophobic bedroom.

‘Who’s nicked my radio?! Come on, you’re not going back to sleep till you tell me!’

Ayesha was furiously rummaging under beds, pulling sheets off sleeping children and pushing their tousled heads roughly aside so she could look under the pillows. Maisa started to wail and was quickly silenced by a thump in the guts from a grumpy Majeeda. Jasmine fell out of bed in the chaos, landing on the floor with a heavy thud. She started to cry. Tamam shouted at his oldest sister that he hadn’t got it.

The noise brought Fatima to the foot of the stairs.

‘What’s going on?!’ she screamed. ‘Get back in those beds and go to sleep. If I hear any more noise, I’ll come up there and beat the lot of you!’

Instantly there was silence and I knew she meant what she said.

Ayesha stood in the middle of the room, still looking for the missing radio. Then she crouched over Tamam and whispered within an inch of his face, ‘So if you haven’t nicked it, you thieving little sod, who has?’

Tamam smiled. ‘Better ask Mum,’ he said. ‘I think she’s got the answer to that.’

Ayesha’s face fell. Fatima must’ve heard her in the kitchen telling us about the radio. ‘What am I gonna tell Parveen?’ she muttered to no one in particular. ‘That was her radio. She lent it me. Mum’ll have binned it by now. Parveen’s going to kill me.’

‘Should’ve thought of that,’ said Tamam. ‘Now put the light off, will you?’

Ayesha yanked the cord and we were in darkness again. Tamam wriggled around until he was comfortable, not caring that I was on the receiving end of his feet and elbows.

Finally the room settled down and I dozed off. Tamam, too, relaxed and I could hear snoring from Ayesha’s side of the room. The younger girls had also nodded off at last. Until …

‘BZZZZ! BZZZZ!! BZZZZ!!! BZZZZ!!!!’

I sat bolt upright, looking round in terror. Something was wrong with the bed. It seemed to be alive, humming and buzzing as though a nest of angry wasps hiding in the mattress had been disturbed. I shook Tamam as hard as I could and tried to clamber over him to get out. In response he pulled himself up, crawled out of bed and pulled the light cord. Everyone woke up. Ayesha chucked a pillow in his direction and pulled her eiderdown over her head. Tamam leaned under the bed and unplugged something. Immediately the noise stopped. Then he pulled at the sheet on top of the mattress and from underneath it yanked out a thick grey blanket with an ominous dark stain spread right across it.

‘I piss the bed,’ he said simply. ‘I do it every night. If you’ve got a problem with that, lie on the floor. Otherwise shut up.’

I hadn’t said a word. Ayesha leaned over and clicked the light off. The mattress was soaked through and I could feel cold pee all over my legs. Horrible, but not so bad if it’s your own. If it isn’t – disgusting. I turned to the wall and started to cry. Was this what life was going to be like at Aunty Fatima’s?

In the days and weeks that followed, I discovered that the answer was ‘yes’. 97 Nile Street was cramped, chaotic, often violent (when Fatima delivered the slaps she’d promised on that first night) and always noisy. It’s the noise I remember most – the screaming, shouting, bickering, pushing and shoving that inevitably goes on when too many people are packed into a small space. Nile Street was less of a home and more of a crowd, especially when the daily procession of ‘aunties’ and their children came knocking on the door. True to his word, Tamam pissed the bed every night and mostly slept through the terrible wake-up call of his blanket alarm. Fatima was occasionally woken by it and would come into the bedroom screeching and shouting at us all to get up while she changed the sheets. Every night involved some kind of disturbance. Within a few days I went from a happy, playful child to a withdrawn creature with dark rings around his eyes who craved his own space and spent hours loitering in the alley behind Fatima’s backyard.

That said, Tamam wasn’t the bully I had him down for on that first night. He turned out to be a nice enough lad, and although he was a couple of years older than me, he didn’t resent me being in the house and even seemed to be pleased to have someone to knock around with.

I didn’t bother much with the younger girls; they did their own thing and that was fine by me. Ayesha was kind to both Jasmine and me, but seemed to be spending more and more time in the kitchen or sweeping the backyard. There was talk of marriage to a man from Pakistan. Ayesha would go ‘home’ for the wedding, then come back to live here with her new husband. Her British-born status guaranteed his residency. Was she happy about this? Being so young, I found it hard to know, but I do recall that she would regularly stand on the windowsill in the front bedroom, talking through the unlatched window to other teenagers – boys included – on the street. Sometimes Fatima caught her at it and gave her a big dressing-down in front of the whole family. Talking to boys was ‘shameful’, she insisted, and was bringing dishonour on their good name around Hawesmill.

‘Do you want to get married,’ she screeched, ‘or are you going to stay on the shelf forever? Because that’s the way you’re going!’

Ayesha was 15 at the time – stupidly young by Western standards for any talk of marriage, or even engagement. But in Pakistan it wasn’t uncommon to find girls half her age in that position. Besides, Yasir was 17 and he was due to get married soon. It was only right that Ayesha should be next.

The front room of the house was Dilawar’s little kingdom. He used it as a kind of storeroom for the shop, particularly for valuable and easily-stolen items like cigarettes, and we were never allowed in. Often he would take in his Pakistani newspaper and lock the door behind him, pleased to be away from the noise. He couldn’t escape the smell of curry, though, which percolated every room. There was always something bubbling away in a pan on the stove – just as well, given the number of visitors the house received and the odd times of day or night that Dilawar and Yasir would arrive home.

Generally, Dilawar was a kind and quiet man who would only flare up when Tamam was misbehaving. Then he’d beat him severely, leaving the rest of us in no doubt that he would do the same to us if we played up.

One of the highlights of the week was when Dilawar and Yasir came home from the shop with bags full of loose change. They’d pour it all over the low table in the back living room and ask us children to help count it. My cousins were surprisingly good at this, given their age and the fact that attending school wasn’t high on the list of priorities in Nile Street. They’d count out piles of coppers and silver, putting them to one side when they’d reached a pound’s worth. Yasir or Dilawar would then bag them up, £10 per bag. As far as I could tell, they didn’t have a bank account (it’s considered un-Islamic to trade with high street banks that have interest rates) and so all the money was kept in the locked front room. That’s what passed for family entertainment in that house.

As time went on and Dad’s visits became fewer, Fatima took less trouble to disguise her feelings towards us. She’d never been what you might describe as ‘warm’, but she definitely got worse. She screamed and shouted endlessly and it always seemed to be me who provoked it. Many times she raised her hand, and while she never hit me or Jasmine, the threat was clear. Perhaps she was afraid that we’d tell Dad and she’d get in trouble. Her problem was that she couldn’t see us simply as her brother’s kids. We also belonged to ‘that Englishwoman’, the woman who’d entered this close-knit family and taken her brother away. That he’d betrayed his Western wife and taken her kids abroad didn’t count; Fatima seemed to believe we were tainted with kuffar blood and would always remain outsiders. So why didn’t she and the family set us free? The logical decision would’ve been to return us to our mum. But there was something about this family that made it impossible for them to let go. We would have to stay among them until all traces of Western influence were removed.

But if we were out of sight, we were out of mind. So Fatima created a special punishment for Jasmine and me. If we’d been naughty we were marched upstairs, pushed into the back bedroom and locked in. Occasionally it was both of us, but more often than not, I was alone. I think Fatima knew that Jasmine was young enough to be ‘re-educated’ effectively. She was also female, which carries its own status in Muslim culture. I was a different matter. Perhaps Fatima saw that I would not be so easily moulded. Whatever her reasons, I found myself spending hours in that locked room, staring out over the grey slate rooftops of Hawesmill and wondering what I’d done that was so wrong.

There were times when Jasmine and I clearly hadn’t done anything wrong, but were locked in the bedroom anyway. One minute we would be playing with our cousins, the next Fatima would be whisking us upstairs as the whole house erupted in frenzied activity, children and adults running and shouting everywhere. As we were rushed up, I was sometimes certain I could hear the sound of the letterbox flapping at the front door, accompanied by a woman’s voice yelling through it. When this happened, the door was never, ever opened, and yet normally a constant stream of visitors walked over that threshold at all times of the day. What was so wrong with this particular visitor that they could not be admitted?

We ourselves weren’t allowed out of the house very much. A walk to Dilawar’s shop with Fatima or Ayesha was as far as we got. There were no trips to the park, the playground or the seaside. We didn’t go into the town. Our whole life was 97 Nile Street and a couple of streets around it. We didn’t even go to school. Now I wonder why no school inspectors were on Fatima’s tail, but maybe back then they didn’t care whether Asian kids attended or not. However, we were getting an education of sorts at a house at the back of Nile Street that had been knocked through into the house next door and converted into a mosque.

Sebastopol Street was the home of the local imam and his wife. The mosque itself was only for men and older boys, so, with Jasmine, Tamam and Maisa, plus a handful of other little kids from around Hawesmill, I went along several times a week to sit in a side-room and learn the basics of Arabic, making a start on the 114 chapters of the Qu’ran. The imam’s wife took the lessons, handing out simple little textbooks which taught the ‘ABC’ in Arabic, plus other key words and phrases. As we made our first clumsy attempts at this complicated language she listened to us in silence, constantly playing with a set of worry beads. She taught us sentences that form the cornerstones of the Holy Book, for example:

Bismill

hi r-ra

m

ni r-ra

m

Al

amdu lill

hi rabbi l-’

lam

n.

which translates as:

‘In the name of God, the most beneficent, the most merciful,

All appreciation, gratefulness and thankfulness are to Allah alone, lord of the worlds.’

From an early age all Muslims know these verses from the opening of the Qu’ran, and I was no exception. I’d heard them spoken while in Pakistan. But I found it very difficult to read basic Arabic and also to get the correct pronunciation. The imam’s wife would listen to my tongue twisting all over the place and, with an expression like vinegar, hit me with a short stick she kept under the seat. She didn’t do it very hard – it was more of a tap than anything else – but it was enough to make me anxious. It also had the opposite effect to that intended: instead of learning to read and speak the verses properly, I became more word-blind and tongue-tied. From that moment on, I struggled with the Qu’ran. It would cause me no end of problems as my childhood progressed.

Chapter Three

After ten months at Fatima’s I’d become used to Dad coming and going. He would disappear for weeks on end and although I missed him at first, especially as Fatima obviously had it in for me, his absence wasn’t so noticeable day by day. What was becoming annoying was Tamam’s constant teasing about my ‘white Mum’. It was childish stuff but it hurt, especially when I was locked in the bedroom for retaliating. In there, the same old questions would go round in my mind. Where was she? Did she know we were here? When would she come for us?

The last question was the one I thought about most. As time went on and she didn’t appear, I wondered if she’d forgotten us or had found some other kids to be mum to. I must have asked Fatima loads of times about her (and, judging by Tamam’s teasing, it was obviously a topic for family discussion when we weren’t listening), but she constantly stonewalled me.

In the end, the knock on the door that saved us from a life of punishment and drudgery at Fatima’s came not from Mum but from Dad. He appeared one afternoon in late autumn, looking well-fed and satisfied with life. He stepped into 97 Nile Street with a big smile on his face and picked up me and Jasmine in one swoop.

‘I’m back, kids,’ he shouted, ‘and I won’t be going away again! I’ve got us a place to live just round the corner. We’re all going home at last.’

We squealed and shouted with happiness. I couldn’t believe Dad was back and we were leaving horrible Aunty Fatima’s.

We were full of questions, but Dad silenced us with a wave of the hand. ‘I know, I know, you want to ask everything,’ he said. ‘But first I want you to do something. There are some people outside I’d like you to meet. They’re in the car. Come on, I’ll show you.’

He took us by the hand and led us about 10 yards up the street to an old brown Datsun Sunny. A youngish shy-looking woman in a headscarf sat in the passenger seat, holding a baby. As we got up to the window she stared wide-eyed at us, then up at Dad. In the back of the car were three children who were jumping and scrabbling about like a family of monkeys. They seemed very keen to get out and yet they shrank back from the window as I leaned forward and looked in.

I turned to Dad. ‘Who are these people?’

‘This,’ he said slowly, ‘is your new mum. She’s come all the way from Pakistan to look after you. Isn’t that good?’

‘So why’s she brought these kids?’

‘They’re your brother and sisters. We’re going to live together. You’ve got some new kids to play with now, eh?’

Brother and sisters? I didn’t get it. Neither could I understand why we needed a new mum. I wanted to ask about the old one, but Dad seemed so happy to see us that I decided not to make him cross by mentioning her. Jasmine and I climbed onto the back seat of the Datsun, squeezing in next to the kids, who had suddenly become strangely silent.

‘This is Abida,’ Dad said, pointing at the woman in the front seat.

She smiled gently and said, ‘Hello there,’ in Pashto. I smiled back. She seemed nice – nicer than Fatima anyway.

‘And this is Rabida,’ Dad continued, gesturing to a girl of about 12. She ignored the introduction and looked out of the window at the row of terrace houses.

‘And these little ones are Baasima, Parvaiz and Nahid. Nahid’s the baby. Children, this is Mohammed and Jasmine. Say hello, everyone.’

The younger boy and girl, Parvaiz and Baasima, just stared at us. I shuffled around on the leatherette seat, not knowing what to do. The awkward moment was broken by Dad turning the key in the ignition and revving the engine as hard as he could before pulling away up the hill and out of Nile Street. I didn’t really care who these strangers were. We’d escaped from Fatima’s; for the moment, that was all that mattered.

The car turned into Hamilton Terrace, a street or two away from Fatima’s, and stopped outside a house in the middle of the row. From the outside, number 44 looked much the same as 97 Nile Street. The inside was depressingly familiar: two small rooms and a kitchen downstairs, two little bedrooms and a bathroom upstairs, plus a yard out the back. What was missing, thankfully, was Fatima’s sour face. I was very pleased about that and hardly noticed how shabby the house really was. From the beginning, despite Abida’s shyness, this felt like a happy home.

Dad started work as a jobbing builder and handyman, fixing drains, roof tiles, chimneys and window frames on houses all over Hawesmill. The condition of the properties meant work was plentiful. We were glad, not just because it brought some money in but also because Dad was around a lot more. His trips to Pakistan stopped and it slowly dawned on me that when Dad had introduced Rabida, Baasima, Parvaiz and Nahid as our ‘brother and sisters’ he had been telling us that he was their dad too. This was the family he’d left behind when he’d journeyed to England, the family that had patiently waited for him while he had married Mum and had us two.

Rabida was older than me. The others were younger. Dad had been a busy man on his trips abroad, that was obvious. I don’t know how Abida had reacted to the news of his English marriage. I expect she had taken the long-term view that one day she would come to England and take up her rightful place as Dad’s wife. I don’t know how she viewed Mum. Perhaps she thought she’d share Dad with her, as polygamy is not uncommon among Muslims. Or maybe she knew full well that Mum wouldn’t be around one day.

Dad tried his best to make this flung-together family work. When he had time off he’d take us all to a nearby park for an hour or two on the swings. It was lovely for us, because Fatima had never taken us anywhere. I can see him now, pushing me higher and higher until I could barely breathe with the thrill of it. The more I squealed, the more he laughed, the other kids pulling desperately at his trousers to make sure they got their turn. Once he piled us all into the back of the Datsun Sunny and took us to Blackpool for the day. It must have been my first visit to the seaside. I was overwhelmed by the experience. I sat at the water’s edge and dug in the sand, the sea filling up the hole as quickly as I could dig. The beach was packed with holidaymakers and daytrippers, all having fun. Above, seagulls wheeled and cried and I could almost taste the salty wind. It was one of the best days of my life so far and I didn’t want it to end.

The sleeping arrangements at Hamilton Terrace were almost as complicated as those at Nile Street, but at least Parvaiz didn’t wet the bed. Although there were a lot of us, the atmosphere around the house was nowhere near as frenetic as it had been at Fatima’s. Dad treated us all the same, as we were all his children. It was different with Abida: her own children came first every time. If they wanted an apple or a fig, they only had to ask. When Jasmine or I asked, the request was granted, but reluctantly. Now, I see that a mother naturally puts her own first, but back then I just felt that Abida was being difficult and sometimes unfair. At Eid, the holiday that marks the end of Ramadan, little gifts of money or sweets are given to children by adults grateful that the long period of fasting has finished. Abida’s four children always filled their pockets with bits and pieces given to them by their mum and dad. Sadly, Jasmine and I hardly ever shared in their good fortune. Dad, I suppose, was too busy to notice, but we certainly did.

That said, some months after we moved in I asked Abida if I could call her Ami, meaning ‘Mum’. She seemed very pleased that I thought of her in this way, and from then on I called her Mum at every available opportunity. It was nice to be able to say the word after so long, though it was tinged with sadness because it made me think of my real mum. The old image of the white face and dark hair would flash through my mind and I would desperately try to remember her features. But the memory had long gone.

Finally, I started primary school. I must have been around nine by then and had missed out on a huge amount in terms of reading and writing. There would be a lot of catching up to do, but I was prepared to put the work in.

The school was old-fashioned in terms of the building. The roof leaked in winter and when the boiler packed up in freezing conditions we were always sent home. The teachers were a kindly bunch. They were mainly elderly, female and white, and did their best to educate children who had been born in Britain but whose language and culture were based elsewhere. There weren’t many white faces among my classmates. Most white families had moved out of Hawesmill long before, not wanting to live next door to ‘Pakis’. Those who did stay put wanted little or nothing to do with us but refused to be ‘forced out’, as they saw it.

I found white people fascinating. We never went into the town and didn’t know any white people, so to be near them in the classroom was very interesting, even if they hardly spoke to me. I wished they would. I would hear Tamam’s taunts about the ‘white mother’ in my head, and wonder what life was like for these kids with white mums and dads. What did they talk about? Where did they go? What did they eat? My curiosity was stirred.

I made some progress at school and still attended the mosque school in Sebastopol Street as well. Abida did her best with us all at home, but she had been raised traditionally and wanted exactly the same for her children. Her girls were all shown how to cook, clean and keep house, and Jasmine was not immune from these chores. I remember coming downstairs one morning to find she’d been up for at least an hour washing the family’s clothes by hand in the sink. She was about seven at the time.

Dad seemed happy enough with the domestic arrangements. He breezed in and out of Hamilton Terrace, usually for meals, between labouring jobs. He loved his food, relishing the oily, traditional Pakistani curries made for him by Abida. He would mop up whatever remained with thick pieces of naan bread, licking his lips as he swallowed down the last of the rice.

‘Mum is a great cook,’ he’d say, as she cleared his plate away. ‘Best food I’ve ever had.’

Abida smiled, delighted that she was making her husband happy. After all, there is no greater honour for a Muslim wife than to serve her husband according to the laws of God.

After his meal, Dad would settle back on the settee in the back room, reading his paper and smoking heavily. I very rarely saw him without a cigarette in his mouth, and the house was thick with the smell of tobacco almost all the time, especially when his male friends came round for a chat and a game of cards, just as they would’ve done back in Tajak.

One of these regular visitors was Rafiq, Abida’s brother. A skinny black-bearded man in his forties who always wore the traditional Pathan topi, or skullcap, he had left Pakistan some years previously to find work in England and had settled in Bradford with a much younger wife who had eventually walked out on him. They had had no children, so, perhaps out of shame or anger, he had left Bradford and come over the Pennines to Hawesmill. Because he was family, Dad took pity on him and welcomed him into the house. He stayed for a few nights before moving into a shared place around the corner and would come round frequently for food and company. He was a solitary brooding man with a deep voice who certainly wasn’t into entertaining us children. We seemed to irritate him hugely and I sensed that given the opportunity, he would lash out. Fortunately Dad was around almost every evening and so Rafiq had little chance to show off the temper I suspected was lurking under the surface.

Dad turned 50 in the early spring of 1985, just before I went into double figures myself. Friends and relations across the north of England were keen to see him, so one afternoon he told Jasmine and me to get our coats. We were going over to Blackburn to pick up a minibus, he explained. Then we’d come back to Hawesmill and collect Abida and the other kids, plus whoever else we could fit in, before heading off to relatives in Bradford. The Yorkshire city had a high number of Pathans living there, and those from the Attock district were either related to or friends of Dad. It would be a big get-together, with plenty of feasting and catching up.

We stood by the old Datsun, pulling impatiently at the passenger door handle. Never mind Bradford, a trip to Blackburn was a big deal, and we couldn’t wait to get going.

We waited and waited, and finally I went back into the house to hurry Dad up. I found him sitting in a chair in the front room, wiping his forehead with a handkerchief. Abida was fussing over him. Dad was naturally light-skinned, but he’d turned a weird sickly yellow colour.

I stood by his chair and pulled at his sleeve. ‘Come on, Dad, we want to go. Why are you sitting there? Come on, hurry up!’

He turned to me. There were dark rings under his eyes. He was sweating like mad. ‘I’m sorry, Moham,’ he said, ‘I’m not feeling so good. I don’t think I’m up to driving.’

I groaned out loud. I really wanted to go. I was sick of looking at the same four walls. I needed a change, even if it was only Blackburn and Bradford.

‘Come on, Dad,’ I pleaded. ‘You’ll be alright in a minute. We can always stop on the way. Please, Dad.’

He didn’t reply, just waved his hand in my direction. I sensed someone behind me and looked round. Rafiq was standing there, calmly taking in the scene.

‘I’ll go and get the minibus,’ he said. ‘I’ll get someone to drive your car back.’

‘Thanks, Rafiq,’ Dad said, taking a sip of water from a glass. Abida wiped his forehead again. ‘Would you mind taking the kids with you? They’re desperate for a trip out and I’ve promised them. Sorry, Rafiq. They’ll be good. Won’t you?’

I was torn between wanting a trip out and not wanting to go with Rafiq. I knew it would be an uncomfortable journey, but it would be a journey all the same.

‘Yes, Dad. I promise.’

‘Good lad. Go on then, off you go. I’ll be OK by the time you get back.’

I ran out and told Jasmine the news. She scrunched up her face when she heard who was taking us, but luckily she didn’t say anything, because within a second Rafiq was out of the front door, car keys in hand. He unlocked the car and indicated that we should get into the back. By trade he was a minicab driver, and we definitely felt like a couple of fares he’d just picked up. Jasmine started chatting straight away, but a look from Rafiq through the rear-view mirror was enough to shut her up and we drove to Blackburn in complete silence.

After 30 minutes or so we arrived at a house in the Whalley Range area of the town. This was the Hawesmill of Blackburn – steep hills, streets full of Asians and not a white face in sight. Like every other in the street, the house we were going to was a small brick-fronted terrace. A gang of kids playing outside peered into the car as we pulled up.

Rafiq let us out, telling us to stand by the car. He went into the house and came out five minutes later with a grey-bearded, grave-looking older man. This man pushed past us and opened the driver’s door. He wound down the window, said a quick few words to Rafiq and was gone.

‘Follow me,’ Rafiq said and we trotted up the hill behind him. Just before the brow of the hill we turned into a scruffy backstreet where a minibus was parked. Again we were consigned to the back seat. Again the journey took place in complete silence. The van smelled of diesel and I hoped I wouldn’t be sick. If I was, I knew for sure it wouldn’t be Rafiq cleaning it up.

I tried to concentrate on getting home and the journey to Bradford with Dad. We would laugh and joke with him as we crossed the Pennines, pointing out funny things by the road and playing ‘I spy’. He’d open the windows and get rid of this horrible fuel smell. Perhaps we’d stop at a café before we reached the city. Once Rafiq was out of the way we’d be fine.

As we reached Hawesmill and pulled into Hamilton Terrace there was a group of people standing outside number 44. Abida was in the middle of a group of women, and I could see Fatima, Ayesha and Yasir, Fatima’s eldest son, standing among them.

Rafiq pulled up against the kerb. ‘What’s going on?’ he shouted.

Yasir came over and leaned into the open window. He saw us and silently beckoned Rafiq out. Abida was clutching her hijab, or headscarf, across her face. She looked frightened. Someone put a hand on her shoulder and whispered to her. There was something terribly wrong.

The bus’s engine was still running as Abida and Rabida got in, along with Yasir. The younger children were hustled back into the house by Fatima. Rafiq climbed back into the driver’s seat.

‘Are we off to Bradford now?’ I said. ‘Why’s Dad not coming? Is he still poorly?’

Abida took hold of my hand. ‘He’s not very well, Mohammed,’ she said. ‘Not very well at all. He’s had to go to hospital. We’re going to see how he is.’

In the front seat Yasir turned round. ‘Don’t worry, kids,’ he said, smiling. ‘He’ll be OK. He’s just a bit … hurt. We’ll see him soon. That’ll cheer him up.’

We parked close by the hospital’s A and E department and hurried through its doors, the adults looking right and left down the wards to catch a glimpse of Dad. Everyone seemed to be staring at this scared-looking bunch of foreigners in their flowing clothes, running down corridors and shouting Dad’s name.

Ahead of us, a man in a white coat saw us coming and put out his hand to stop us in our tracks. ‘Can I help you?’ he said brightly. ‘Are you looking for anyone in particular?’

The women looked at one another. They knew no English and hadn’t a clue what the white man in the white coat had said. Rafiq knew a few words, but not enough to answer the doctor, and he simply shrugged his shoulders. Fortunately Yasir’s English was good, saving us from looking like a complete bunch of village idiots.

‘We’re looking for Ahmed Khan,’ he said, ‘from Hamilton Terrace, Hawesmill. He’s 50. He’s been brought in by ambulance. How is he? Can we see him?’

The doctor looked at his clipboard and ran his finger down a list of names. ‘Please, all of you come over here,’ he said, ‘just to the side of the ward.’

Obediently we shuffled into a small office off the main corridor.

The doctor bit his lip and looked down as he spoke. ‘I’m sorry to have to tell you that Mr Khan died half an hour ago. He had a huge heart attack.’

I caught the words but didn’t understand. Yasir paused, taking in the terrible news, then translated for Abida and the others. Immediately she started caterwauling, beating her chest and head with her shut fists. Rafiq stared out of the office door, expressionless, as Rabida wept and clung to her mother.

‘I’m sorry,’ repeated the doctor. ‘I’m afraid there was nothing we could do.’

The next hour or so was a blur of tears, screaming, shouting and grief-stricken fury. ‘Mr Khan died half an hour ago. Died … died … died …’ The doctor’s words were repeating in my head. Dad was dead. Something had happened to his heart and he’d died. We wouldn’t see him again. He’d gone, this time for good.

This couldn’t be happening. I’d never known anyone to die. It seemed a really stupid thing for Dad to do. Stupid enough for him to return home later on, when everyone had stopped crying, and apologize for being so daft. But he wasn’t going to. They said he was dead. Dead people didn’t come back.

Chapter Four

We arrived at Hamilton Terrace to find the house deserted. Rabida was sent down the street to Fatima’s with the bad news. Abida was still weeping and beating her chest. Rafiq and Yasir stood a few feet from her, not wishing to be contaminated by female grief. Muslim men have their own mourning rituals and there is little mutual comfort between the sexes, at least not in public. Jasmine and I stood on the pavement, not knowing where we belonged. Jasmine pulled at the sleeve of Abida’s jilbab, or coat, but she didn’t want to know. She was too caught up in the horrifying shock of what had happened.

Within five minutes Fatima came marching up the street, Rabida behind her, clutching the hands of the little kids we’d left in her care before we set off to the hospital. She was crying hard, but as the nearest of Dad’s relatives in this country, she was second in line to the chief mourner and therefore had work to do. The first job was to organize a very large pot of tea and find as many cups as possible.

The men, including Rafiq, Yasir and Dilawar, went into the front room and shut the door. The women trooped into the kitchen with us children. Chairs were arranged in a circle in the back room while Fatima made the tea. She put her arms around Abida and the two cried on each other’s shoulders, praying to God for Dad’s soul.

News of Dad’s death spread quickly and within quarter of an hour the little house was full of people from the surrounding streets. To us, all the women were ‘aunty’, no matter whether they were related or not. Many of these grieving ladies were gazing at Jasmine and me with pity as we stood bewildered in the back room.

‘God bless them,’ said one aunty, putting her hand on my head and pulling me to her. ‘What have they done to deserve this?’

She squeezed hard and I felt uncomfortable pressed up tight against her salwar kameez. As she released her grip, I was bundled into the folds of another mourner, who asked God to forgive us: ‘Astaghfirullah.’

‘Don’t worry, child,’ she whispered in my ear. ‘You will be fine. You will be looked after. God has willed it.’

In the far corner of the room Jasmine was getting an equal amount of attention. She was being passed from one aunty to another like a precious china doll. Our step-sisters and brother were around, and just as upset as we were, but getting nowhere near the amount of fuss.

‘Oh, Mohammed, God bless you, I’m so sorry about your father. He was a good man.’ A tubby aunty stood in front of me, her hand flat on the top of my head. She smiled sympathetically and wiped away a tear. ‘God bless you both,’ she said, ‘you poor little orphans.’

I stepped back, shocked. Orphans? How could we be? I’d heard the word in school, but had taken no notice of it. It seemed to be something that happened to people a hundred years ago. Then I realized: our Dad was dead and our Mum was … well, where was she? She certainly wasn’t here, and we hadn’t seen her for seven years. Did that mean she was dead too? Was it something they all knew about, but weren’t telling us?

Suddenly I felt very sick, and for the first time that day, my resistance crumbled and I began to cry. This had a chain reaction and soon the tiny back room was filled with women lifting their arms up to God and keening loudly with grief.

Not long after, the front-room door was opened and the men left the house. That room was also full to bursting and they’d decided to find a quieter place. Their way of mourning was to tell old stories about the deceased and make arrangements for the funeral. Under Islamic law the body must be washed, dressed in a shroud and buried as soon as possible, usually within hours of the death. As Dad’s body was to be flown back to Pakistan, however, this wasn’t possible. His funeral would be in two days, followed by immediate repatriation. In Muslim communities, individuals pay into a fund that covers funeral and travel expenses. One family looks after this money and makes all the arrangements when a person dies. The men were obviously going away to discuss this.

Later that day, Rafiq came back to Hamilton Terrace. This was the signal for the women to leave. With final hugs and kisses, plus pats on the head for us, the aunties went home and another chapter in the life of the Muslim community of Hawesmill was closed. Everything would return to normal once Dad had made his final journey to Pakistan. If only that could be true for me …

A worn-out looking Abida began to wash up all the cups and plates, assisted by Rabida. When the last cup was dried, she turned to us, her eyes puffy and cheeks blotched from crying. ‘Go to bed now,’ she said. ‘Today is a very sad day, but tomorrow will be better. Go on – upstairs.’

She kissed us all one by one and ushered us out of the kitchen. The younger ones clung to her, but she firmly but kindly brushed them off and sent them on their way. She probably wanted time alone to reflect. At 10, I had no concept of that and just wanted someone to hold.

‘I don’t want to go to bed,’ I said. ‘I’m frightened. Can I stay down for a bit?’

‘No, Moham,’ she said, ‘not now. It’s getting late. Tomorrow we will talk if you want.’

‘But Ami, I’m scared. Please.’

‘No!’ Rafiq glared at me. ‘Upstairs – now!’

I stood for a second or two, not knowing whether to stay or go. I could feel him staring at me, waiting for me to make a move. When I did turn towards the stairs it was with deliberately slow movements. I didn’t want to disobey him, but neither did I want him to tell me what to do.

I crawled into bed and pulled the covers over my face. Outside, people were still knocking on the door to offer their condolences. Rafiq’s deep voice boomed through the thin walls as he thanked people for their thoughts and advised them to come back tomorrow. I thought about the aunty and her ‘orphan’ reference. Dad wouldn’t want me to cry, but I couldn’t stop the tears from coming. To know that I wouldn’t see his face again was hard enough, but at least he hadn’t made the choice to leave us, it had just happened. What about Mum? Had she had a choice? And if she had, why hadn’t she chosen to keep us? The same questions went round and round until my mind was playing games with itself and my eyes began to droop …

I woke, or at least I thought I did. Dad was in a corner of the room, looking at me. He seemed to be smiling, reaching out his hand. I stared, blinked … Then he was gone.

I screamed, jumped out of bed and ran downstairs.

‘Dad’s in my room! Ami, Daddy’s in my room!’

Abida was sitting in the kitchen, nursing a cup of tea and talking to Rafiq.

‘Ami, please!’ I pulled at her sleeve, wanting her to come upstairs and take away the nightmare I’d just had.

Rafiq was having none of it. He grabbed me by the neck before Abida could stop him and hauled me up the purple-carpeted stairs.

‘I’ve told you once,’ he hissed, ‘and I won’t tell you again. Into bed, go to sleep – or else …’

He pushed me into the bedroom and slammed the door.

I really didn’t want to be back in there and immediately turned the light on. The others began to wake up, their tangled little heads rising up sleepily from warm pillows.

Rafiq flung open the door and pushed me hard up against the wall. ‘Get to sleep, you bastarrd,’ he snarled at me, the ‘r’ of the last word rolling off his tongue.