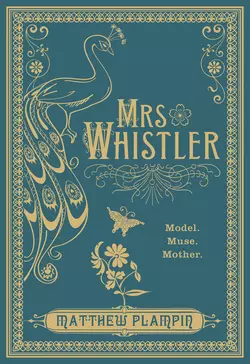

Mrs Whistler

Matthew Plampin

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1396.27 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘A captivating tale …This novel is a delight’ THE TIMES‘A terrific novel … It springs off the page’ DEBORAH MOGGACH′Vividly engaging’ SUNDAY TIMES‘Maud could tell the whole story, but she will not’Chelsea 1876: Jimmy Whistler stands on the cusp of fame, ready to astound the London art world with his radical paintings. At his side is Maud Franklin, his muse, lover and occasional pupil, sharing his house, his dazzling social life and his grand hopes for the future.But Jimmy’s rebelliousness comes at a heavy price for them both as he battles a furious patron, challenges an influential and viciously hostile critic and struggles with a dire lack of cash. Before long a fight for survival is being waged through the galleries, the drawing rooms and even the courts – and Maud, Jimmy’s Madame and closest ally, is expected to do her part.The Madame has problems of her own, however. Maud has fallen pregnant, and must now face the reality of what life with Jimmy entails. As the situation starts to unravel, as loyalties are sorely tested and bankruptcy looms, she has to decide what she wants. Who she is. What she is prepared to endure.Stunning and suspenseful, this a story of one woman’s progress through a world of beauty and sacrifice, art and ambition; a story which asks what we will withstand for love, and what it means to reach for greatness.