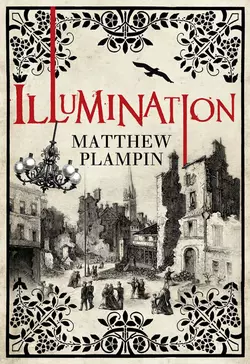

Illumination

Matthew Plampin

A powerful story of revolution, love and intense rivalry set in 1870 during the four-month siege of Paris.1870. All over Paris the lights are going out. The Prussians are encircling the city and Europe’s capital of decadent pleasure and luxury is becoming a prison, its citizens caught between defiance and despair. Desperate times lie ahead as the worst winter for decades sets in and starvation looms.One man seems to shine like a beacon in the shadows. Jean-Jacques Allix promises to be the leader the people need, to save the city itself. Painter Hannah Pardy, his young English lover, believes in him utterly; taking up arms for his cause, she is drawn into the heart of the battle for Paris. But as the darkness and panic spreads it is harder and harder to see things as they really are, and Hannah struggles to separate love from self-interest and revolutionaries from traitors.Faced with impossible decisions, Hannah must confront the devastating reality of her beloved Paris to establish what truly matters to her – and what she will do to protect it.

Table of Contents

Title Page (#ub432712d-4b8c-50d6-b25f-748695dff6ef)

Dedication (#ub1fe5a9a-9e41-5119-82e7-3fc046763299)

Map (#u449e5854-7984-5c2e-8502-6411c1a06a2f)

Epigraph (#u6ec5ad3e-dc7c-5e6f-9287-bd753ebcfc76)

Prologue: Venus Verticordia – London 1868 (#u355d0fe5-9490-5653-ab30-f1998ecfeda1)

Part One: City of Light – Paris, September 1870 (#u356e2e3e-e5b7-503e-bb47-bfb34a69233c)

Chapter I (#u44c7c2a6-23b7-527c-8805-5ea4de81266a)

Chapter II (#ue6213db8-9b96-573f-8152-38568f75f11e)

Chapter III (#u5e0773f7-7a93-51d7-af96-6ff1945bc7a6)

Chapter IV (#ufa489a23-38e7-54a6-a343-77864991f6b2)

Part Two: The Goddess of Revolt (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter I (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter II (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter III (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter IV (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: Wolf Steak at the Paris Grand (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter I (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter II (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter III (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter IV (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Four: Illumination (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter I (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter II (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter III (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter IV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter V (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VI (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Matthew Plampin (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

For my mother

I no longer remember what Bakunin said, and it would in any case scarcely be possible to reproduce it. His speech was elemental and incandescent – a raging storm with lightning flashes and thunderclaps, and a roaring of lions. The man was a born speaker made for the revolution. If he had asked his hearers to cut each other’s throats, they would have cheerfully obeyed him.

The Memoirs of Baron N. Wrangel

It is not enough to conquer; one must also know how to seduce.

Voltaire

PROLOGUE (#ulink_aaf4219f-fabf-54b7-8ce5-f49571ff970d)

Hannah entered the drawing room and froze: what appeared to be a miniature kangaroo had climbed up onto a chair and was nibbling at a vase of lilies. She stared at it for a few seconds – the black lips pulling delicately at the petals, the elongated toes rubbing mud into the satin upholstery – and wondered what she should do. Creatures both strange and familiar were everywhere at Tudor House. Caged parakeets shrieked in the hall; racoons and marmots scuttled beneath the furniture, their claws tapping on the floor tiles; and at dinner, a huge, sad-eyed dog (an Irish deerhound, they were told) had loped in and laid itself by the hearth without even glancing at the assembled guests.

‘My apologies, Miss Pardy,’ said her host, who had arrived at her side, ‘the little buggers are always escaping from their pen and finding their way indoors. There is nought so bold, so precious clever, as a greedy wallaby. Do excuse me – excuse us.’

He edged forward with his arms outstretched, repeating the beast’s name (which was Freda) in the tone of a doting father. The wallaby slipped from the chair, bounding sharply to the right and then to the left – a technique developed to foil the predators of the Australian desert that proved more than a match for a rotund painter-poet in a Chelsea drawing room.

The other guests had started to drift in. Instead of helping their host they gathered like spectators around a street show, cheering as Freda dodged another lunge. Most of them were writers or artists, or those who live off writers or artists; before long they were spouting poetry again, something about a knight’s quest this time, bellowing the verse in good-humoured competition. Hannah didn’t recognise it. She scratched her elbow through the sleeve of her gown. The evening was not going to plan.

Freda made it to the French doors, one of which had been left ajar, and hopped out into the cool April evening. Her owner was close behind, followed in turn by eight or nine chortling gentlemen. Among them was Clement, lighting a cigarette whilst recounting a joke he’d heard in an alehouse. He was doing rather better with these people than Hannah, despite knowing as much about art as the butcher’s boy. Opposite twins, that was Elizabeth’s favoured description: siblings born together who were different in every possible regard. This phrase had always made Hannah wince, but she could not deny the truth in it. Her brother had an easy amiability that she would never possess. Clem could bob along quite happily on the surface of almost any society – whilst she sank down into its depths, growing restless and irritable, longing to be away.

A finger prodded Hannah’s hip. Elizabeth was smiling, but her eyes were hard with purpose. She nodded after their host. ‘Follow him.’

‘He is not interested, Elizabeth. Not in the least.’

‘What rot. He’ll soon be finished with that ridiculous pet of his and then you must act. This opportunity may not be repeated.’

‘It is futile. You were at the table. You heard their conversation.’

‘They are unconventional. I warned you of this, Hannah. They are artists. They think differently, even by our standards.’

Hannah sighed. ‘They talked of money and their love affairs – gossip, Elizabeth – and recited a great long bookshelf’s worth of poetry at one another. What is so unconventional about that?’

Elizabeth’s smile vanished. It pleased her to think that these friends of hers were outrageous, an affront to propriety, and she did not appreciate Hannah suggesting otherwise. ‘Perhaps, then, you should have done something to make yourself worthy of their notice. But once more you insist upon surly silence, coupled with a scowl that spoils you completely. How much do you suppose that will achieve, you impossible girl?’

Hannah would not be scolded. ‘And what exactly was I to say? Their only care was the extent of my resemblance to you. None of them so much as mentioned my work. You said that they were curious – that you’d prepared the ground.’

This was a significant understatement. Back in St John’s Wood, Elizabeth had declared that the evening would be nothing less than an initiation, launching Hannah into a vibrant world rich with possibilities. An alliance with the Cheyne Walk circle could lead to contacts, to sales, to an arrangement with a picture dealer – to an artistic career. Hannah had actually been excited, despite everything she knew about Elizabeth’s promises and predictions; this, at last, had seemed like a real chance. Within a half-hour of their arrival at Tudor House, however, all hope had been dispelled. There was nothing for her here. Elizabeth had done it again, and Hannah had cursed herself for relaxing her usual scepticism.

‘You must show some blessed backbone,’ Elizabeth said. ‘You have the matter in reverse. You are allowing him to overlook you.’

Hannah frowned at the floor. An oriental rug was laid across it, stained and faded by the passage of dirty paws. She decided to stay quiet.

Elizabeth pointed to a spot beside the grand piano. ‘Stand there,’ she instructed, starting for the garden. ‘I will follow him.’

The last of the party came in from the dining room – three young women, the only other females present that evening. All were unaccompanied, but this drew no notice at Tudor House. They’d been seated at the far end of the dinner table from Hannah; they hadn’t been introduced, and had said and eaten very little. The three of them were oddly alike, pale and slender with their auburn hair worn down, clad in loose dresses so white they appeared to glow softly in the gaslight. Hannah wasn’t easily intimidated, yet couldn’t help re-evaluating her own garment; what at home had been a subtle celestial grey now seemed as drab as a day-old puddle.

The three women fell among the cushions of a long sofa, settling into each other’s arms. This casual grace was undercut by their twanging accents, those of ordinary Londoners, which placed them some distance beneath the artistic gentlemen out whooping in the garden. Was this a harem, kept in a similar manner to the painter-poet’s private zoo? Hannah didn’t suppose that such an arrangement was beyond these people. One of the women was looking over at her, she realised, making an assessment then whispering to her friends; they leaned in, heads touching, to share a wicked giggle. Hannah turned away abruptly, searching the drawing room for a distraction. This wasn’t difficult. Every surface was crowded with statuettes and vases, unidentifiable musical instruments or items of exotic jewellery – a collection as vast as it was haphazard. She went to a cluster of jade figurines on a sideboard, suddenly fascinated.

There was laughter in the garden, and Elizabeth reappeared through the French doors with the painter-poet. The taller by two clear inches, she was leading him along as if escorting a convalescent. He was fretting about Freda, who remained at large; she was offering reassurance, telling him that his walls were high and his gardener well practised in dealing with escapees. They drew to a halt a few feet before Hannah.

‘And here she is, Gabriel,’ Elizabeth announced, ‘the reason I ventured out among the menfolk to claim you: my Hannah. Is she not a dove? A skylark, like that of dear Shelley: a star of heaven in the broad day-light?’

Hannah managed a feeble smile; she thought this a peculiar way to broach the subject of her paintings. Their host remained distracted, his small, sunken eyes twitching between the room’s various doorways. He looked as if he was prey to many maladies, of both mind and body – a man locked into an inexorable decline. The three women on the sofa were waving, trying to coax him over, but he paid them no notice.

‘Oh I agree, madam, a skylark, yes,’ he answered, running a hand through his thinning hair. ‘I’m afraid you must excuse me, though. Another crucial matter requires my attention – one quite unrelated to wallabies. It’s my blockheaded errand boy, you see. I have given him instructions, very specific instructions, but the clod is so extraordinarily slow that I cannot tell if he—’

‘People have claimed,’ Elizabeth continued, ‘that she is the picture of me when I was her age; a duplicate, if you like. My feeling, however, if I am quite honest, is that she has a quality I did not. A Renaissance quality. A note of Florence, perhaps, in the late Cinquecento; the beautiful purity one sees in the maidens of Ghirlandaio. It must come from Augustus’s side.’

Mention of Hannah’s father, dead a decade now, was designed to pin their host in place. Augustus Pardy had been a poet of renown, author of the ‘Ode to Dusk’, the verse-play Ariadne at Minos and a number of other commended pieces. He was held in some esteem at Tudor House; Hannah suspected that it was largely for his sake that Elizabeth continued to be invited to these dinners. She held her own, naturally, with endless tales of her foreign travels and the celebrity they had once brought, but her late husband’s name still served as her foundation.

The painter-poet, for the moment at least, was snagged. ‘Your husband was certainly a striking fellow,’ he murmured.

‘She fits so very well among these treasures, does she not? Why, it is like she belongs here, in this enchanting haven of yours.’ Elizabeth brought them closer. ‘And she has a question for you, Gabriel. About your art.’

Hannah attempted to hide both her surprise and the utter blankness that followed it. Seconds passed, piling up; their host cleared his throat; Elizabeth’s expectant gaze glared against her.

‘I do envy your position here beside the river,’ she said eventually. ‘I am sure that if I lived at Tudor House I would be out on the embankment with my easel every morning. Might I ask how often you avail yourself of its sights?’

This made him laugh. ‘Heavens above, I could never work outside! I trade in beauty, Miss Pardy, not coal-smoke and low-hanging cloud! What could there possibly be for my brush out on the Thames? And there are the flies, you know, and the dust, and all the blessed people … It’s a French idea really, this outdoor painting, and results only in the most beastly slop.’ He fixed Hannah with a quizzical expression. ‘But I believe you mentioned an easel, miss. Do you paint?’

There was another brief silence.

Hannah looked back to the jade figurines. She imagined herself smashing them one by one in the fireplace. ‘Our host,’ she stated, ‘is asking if I paint.’

Elizabeth ignored her. ‘You can see something there though, Gabriel, can’t you? As we discussed in the Garrick?’ Her voice was brisk; she was attempting to close a deal. She nodded towards the women on the sofa. ‘Her colouring is lighter than that of Miss Wilding and these others, but then variety is so often the key to success. Perhaps a blonde would—’

‘See something?’ Hannah interrupted. ‘Elizabeth, what on earth are you—’

The painter-poet was growing uncomfortable. ‘Now look here, Bess,’ he said, tugging at his neat little beard, ‘I have told you that I don’t want it. I don’t want the bother or the notice it will bring. I have decided upon my course and will not waste time with second thoughts.’

‘What is he talking about?’ Hannah demanded – although a couple of good guesses were forming in her mind. ‘What doesn’t he want?’

As always, Elizabeth refused to acknowledge defeat. ‘For goodness’ sake, Gabriel, you must not be so damnably stuck in your ways. Hannah may not be quite your normal type but without change, without development, we become stagnant, do we not? Such a painting would serve as the ideal culmination for my account of your career. It would bind author and subject, don’t you see, in a most compelling manner. Interest is sure to be enormous. I predict a serialisation – in the Athenaeum at the very least – and a volume on the stands by the end of the year. Come now, don’t be such a confounded mule. Give your consent and I can promise—’

Tudor House’s errand boy, a gangling youth in cap and braces, filled the doorway that led out to the hall, torn between hailing his master and gaping at the women on the sofa. Provided with the excuse he needed to escape them, their host backed away, reeling off an apology before snapping a reprimand at his boy. Elizabeth watched him go; there was nothing she could do. She shook a crease from her lilac dress, taking care not to meet her daughter’s eye.

‘Explain this,’ Hannah said. ‘Now.’

Elizabeth was unrepentant. ‘If you cannot grasp it for yourself, Hannah, then I have truly failed.’

The artistic gentlemen were filing in from the garden. A spotless mahogany easel was carried through and erected by the piano; the painter-poet fiddled nervously with the gas fittings, opening valves to illuminate the room as much as possible; and finally, at his signal, the canvas was brought before them.

Hannah had never seen an example of their host’s work. She knew about his central role in the Pre-Raphaelite controversy, of course, but that was two decades old; and furthermore, the major paintings it had produced all seemed to be by other hands. He’d become a mysterious figure, enjoying reputation without scrutiny, believed to be selling his startling canvases to a network of buyers across the British Isles yet shunning any form of public exhibition or exposure. Accordingly, although determined to extract a confession from Elizabeth, Hannah could not resist glancing over.

Unframed, unvarnished even, the painting had come straight from the studio upstairs. It depicted the head and shoulders of a young woman, roughly life-sized and quite naked. Her skin was flawless, suffused with warmth, free from the faintest wrinkle or blemish. Flowers crowded around her, the colours unearthly in their richness – honeysuckle blooms rendered in curls of burning orange, roses that ranged from blushing cerise to the ruby blackness of blood. This woman’s beauty had been refined somewhat, but Hannah recognised her immediately. The wide-set green eyes, the slightly heavy jaw, the red, pouting mouth: it was the girl from the sofa, Miss Wilding, who’d mocked her a minute earlier. Indeed, with the unveiling of the picture its model had shifted to the front of her cushion and was preening like an actress at her curtain-call. A cold thought struck through Hannah: thatis what my mother had planned for me.

This was no straightforward portrait, however. Allegorical items were jammed into every corner. Behind the woman hung a gold-leaf halo, fringed unaccountably with buttery moths; off to the right was a bluebird, spreading its wings for flight. In one slender hand she held the apple of temptation, of original sin, and in the other Cupid’s arrow, angled so that it pointed directly at her left nipple – this was Eve and Venus combined, a fleshy goddess neither pagan nor Christian.

To Hannah the result was absurd, overripe and weirdly lifeless, but the artistic gentlemen could scarcely contain their delight. Flushed with wine, they proclaimed the composition to be masterful in its simplicity, the brushwork consummate, and the overall effect so intoxicating that it almost brought one to a swoon. Miss Wilding was showered with compliments and joking avowals of love, and told that she had been captured precisely.

‘The title is Venus Verticordia,’ announced the painter-poet with a flourish, bolstered by his friends’ flattery, ‘the heart-turner, the embodiment of desire – the divine essence of female beauty.’

‘And that she is!’ exclaimed a notable novelist, moving in for a detailed inspection. ‘Dear God, Gabriel, that she dashed well is!’

Hannah resolved to leave. She walked away from the sideboard and cut through the middle of the company. Clement said her name; others laughed and swapped remarks, assuming that her exit was provoked by a fit of feminine jealousy. She didn’t care. Let these idiots think what they pleased. She wanted only to be gone.

Elizabeth caught her on the chequered tiles of the hall. ‘Go no further, Hannah. We are not finished here.’

‘No, Elizabeth,’ Hannah replied, remaining steady, ‘we most certainly are.’

‘The Venus has upset you.’ Elizabeth was perfectly calm. Hannah’s stormings-out didn’t offend her; she would usually applaud them, in fact, as evidence of her daughter’s fighting spirit. ‘It is a crude specimen, I grant you, but you must see that if you were to sit for Gabriel the two of you would be alone for many hours. There would be ample time for you to explain your ideas and win his support.’

This was too much; Hannah’s composure deserted her. ‘Skylarks!’ she spat. ‘Ghirlandaio! You were trying to sell me. Is that where we stand, Elizabeth? Am I merely an object for you to bargain with?’

Elizabeth looked towards the front door; her profile, once featured on the cover plate of a dozen bestselling volumes and still formidably handsome, was outlined against the deep crimson wallpaper. ‘I am disappointed that you choose to take such a naïve view.’

‘What in blazes is naïve about it? Your plan was to deliver me to this Chelsea hermit of yours – to have him fashion me into a bare-breasted fancy for some banker to pant over in his study – so that he’d permit you to write a book about him and breathe life back into your wretched career!’

Hannah was shouting now. Parakeets flapped and squawked in their cages; a stripe-tailed mammal scurried into a rear parlour. All conversation in the drawing room had ceased somewhere around ‘bare-breasted fancy’. Gentlemen’s shoes thudded across the faded rug; they were acquiring an audience. Aware that their host would be in it, and had probably heard her daughter’s pronouncements, Elizabeth rose to his defence.

‘The Venus may not be to your taste, Hannah – and you are, let us be honest here, very particular – but you must surely appreciate the thinking behind it. Beauty, that is Gabriel’s creed: the creation of an art that is independent from religion, from morality, from every conventional form. An art that exists only for itself.’

‘An art, you mean, that has been entirely severed from reality – that exists only in a perverse, febrile dream! At least the French painters he so disdains engage with life, with what is around them, whereas that daub in there – it’s like this damned house. It is a retreat from the world, an evasion, a refusal to—’

A loud snort of amusement from the drawing room knocked Hannah off her stride. Elizabeth seized the chance to retaliate, asking what her daughter would have instead – pictures of pot-houses and rookeries, of dead dogs in gutters? – but Hannah found that her will to argue had been extinguished, shaken out like a match.

‘You lied to me,’ she said bluntly. ‘You told him nothing about my painting. You brought me here only to serve your own ends.’

Elizabeth came nearer, lowering her voice. ‘Oh, spare me that injured tone! It was a harmless manipulation that might ultimately have yielded results for us both. You must not be so damnably sensitive, Hannah.’ Her manner softened very slightly. ‘There is hope yet, I believe, if we work in concert. Something can always be salvaged.’

Hannah almost laughed; she took a backward step, then two more. Elizabeth’s grey eyes had grown conspiratorial, inviting her daughter to join with her as an accomplice – a standard strategy of hers when things went sour. Hannah would not accept.

The front door was weighty, and its hinges well oiled; the slam reverberated through the soles of Hannah’s evening shoes as she ran down the painter-poet’s path. Elizabeth had insisted she wear her hair up, to show off the line of her neck. The real reason for this was now obvious; once out on Cheyne Walk she took an angry satisfaction in pulling it loose, the pins scattering like pine needles on the pavement as the ash-blonde coil unravelled across her back. The night was turning cold. Ahead, past the road, a barge chugged along the black river, its bell ringing. Hannah paused beneath a street lamp and considered the walk home: seven miles, eight perhaps, through several unsavoury districts. It was the only bearable option.

Before she could start, Clement emerged from Tudor House. She watched her twin approach, a cigarette in the corner of his mouth, moving from the gloom into the yellow light of her street lamp. His costume bordered on the comical. The formal suit he wore was several years old and cut for a rather more boyish frame; the necktie was escaping from his collar and threatening to undo itself altogether. It invariably fell to Clement to serve as the Pardy family’s mediator, a role that fitted him little better than his suit; he was an awkward peacemaker, prone to vagueness and the odd contradiction, but there was simply no one else to do it. His grin, intended to mollify, looked distinctly sheepish.

‘The woman is a monster,’ he began. ‘It cannot be denied.’

Hannah wasn’t taken in. The aftermath of her ructions with Elizabeth followed a well-established pattern. She crossed her arms and waited.

‘I do think she’s embarrassed, though. These people really appear to mean something to her.’

‘They are ludicrous. A gang of reptiles.’

Her brother, unfailingly decent, could not let this pass. ‘I say, Han, that’s hardly fair. A couple of them are pretty remarkable, in their way. There was this one little chap with the most gigantic head, a poet he said he was, who claimed to have—’

‘I suppose she is apologising for me?’ Hannah broke in. ‘Begging our host’s forgiveness?’

Clement tossed away his cigarette. ‘Actually, when I left she was laughing it off – telling them that she had no idea that her daughter had grown so conventional, and asking for suggestions as to how it might be corrected.’

Hannah made a disgusted sound and walked off towards Westminster.

‘Come now, Han,’ pleaded Clement, trotting behind her, ‘hold here for a minute more. You’ve got to look at it from her side. Every one of those fine gentlemen in there knows what she was, how famous and rich and so on. And every one of them knows where she is now. It’s a terrible humiliation for her, really it is.’

This was his regular line of reasoning and it had worked on many occasions. Elizabeth’s slide from glory, after all, had defined their lives. It had determined their transition to ever smaller houses, in less and less fashionable areas; the slow diminishment of their stock of valuables; the whittling of their domestic staff to a single elderly Irishwoman who washed the linen every other Wednesday. That evening, however, was different. Hannah felt it with unsettling clarity. Her brother’s appeals were not going to win her around.

‘I have been waiting for so very long for something to happen, Clem.’ The words came out heavily, slowing her to a stop. ‘She calls herself my best and closest ally. She loves to talk it up as a great cause – a battle waged for the whole of womankind.’ A hot tear collected against her nose. ‘And yet all she does are things like this.’

Clement put a hand gently on her shoulder. He did his best, telling her that she must not lose heart and that her persistence was bound to bring rewards, but he couldn’t begin to understand. He had no wind driving him – no desired destination in life. Clem was content merely to coast through a seemingly random series of projects that were often adopted and abandoned within the same week. His present fascination, for instance, was with the electric telegraph, leading to obscure experiments with currents and lengths of wire. This mechanical inclination was unprecedented among the Pardys. Knowing nothing of such matters, Elizabeth had left her son more or less alone – a lack of attention that had shaped his character as profoundly as her interference had shaped Hannah’s.

‘You must come back, Han, at any rate,’ he concluded, ‘to reclaim your cloak and hat.’

Hannah shook her head, wiping her eye on the cuff of her gown. Even this was unthinkable. Returning to her mother’s side was a certain return to disappointment, to antagonism and dispute. It was reducing her, wearing her thin. She could not go on with it; she refused to. In her bookcase, between Mrs Trollope’s Domestic Manners of the Americans and Mrs Jameson’s Sacred and Legendary Art, was an envelope containing nearly fifteen pounds, scraped together over the past few years. The purpose of this sum, only half-perceived before that evening, came to her with sudden force. Hannah looked along the river, away from London and everyone in it. She had to act.

PART ONE (#ulink_5baa30b0-6855-580e-9f5f-d2bd7e57da09)

I (#ulink_72b29079-896a-5ae5-8fef-9746a9f5b5cb)

The platform was packed with people, well dressed and wealthy for the most part, jostling for places on a train that was about to leave for the provinces. They yelled and shoved, hitting at one another with fists, canes and umbrellas. Banknotes, bribes for the attendants, were being waved in the air like a thousand tiny flags. To Clem, fresh from the Calais express with a valise in each hand, the scene was positively apocalyptic. He stopped and tried to get his bearings.

‘Head left,’ Elizabeth shouted in his ear, pushing him forward. ‘We want the rue Lafayette.’

The cab smelled of rice powder and a sickly citrus perfume. Clem heaved the bags up on the luggage rack and flopped into a corner, reaching inside his pocket for a cigarette. Opposite him, his mother had arrayed herself in her customary fashion: perched in the exact centre of the seat so that she had a clear view from both windows, with a notebook in her lap to record her observations. She began to write, lips slightly pursed, the pencil scurrying from one side of the page to the other and then darting back. Clem pulled open the window next to him and lit his cigarette. His ribs were sore, bruised most likely; he’d been elbowed a good few times as he struggled across the seething concourse.

‘Deuced keen to get off, weren’t they? One would think the city was already burning.’

‘Those who grew fat under the Empire,’ declared Elizabeth, ‘who benefited the most from all that corruption and carelessness, are scattering like geese now that something is being asked of them in return.’

‘Well,’ said Clem, ‘that’s certainly one way of looking at it.’

A vast military camp had been established in the streets around the Gare du Nord. Once-elegant avenues were choked with tents and huts, their trees stripped bare to fuel the fires that dotted the promenades, blackening the stonework with smoke. Soldiers sat in their hundreds along the pavements; peering down at them, Clem saw teenaged farmhands in ill-fitting blue tunics, their grubby faces vacant, rifles propped against their shoulders.

‘Lord above,’ he murmured, ‘there must be an entire division out here.’

Elizabeth glanced at the mass of infantry for a couple of seconds and then resumed her note-taking. ‘Efficiency must be our watchword,’ she said as she wrote. ‘We’ll meet with Mr Inglis, we’ll go to Montmartre to find her, and then we’ll bring her straight home. Do you hear me, Clement? The three of us will escape this city together.’

‘How much does your Mr Inglis know?’

‘Simply that I have some urgent business to attend to before this situation with the Prussians comes to a head.’ Her brow furrowed. ‘He isn’t someone I would necessarily choose to place my trust in, but the streets of Paris have been quite transformed since I last numbered among its residents. I doubt I could even find my way from the Madeleine to Notre Dame after Louis Napoleon’s barbaric interferences.’ She finished a page and flipped it over, the flow of words barely interrupted. ‘Mr Inglis, however, has lived on the rue Joubert for longer than anyone cares to remember. His assistance can only speed things along.’

The cab turned a corner, wheeling from sunlight into shadow; a detachment of field artillery clattered past, the crews shouting to each other from their positions on the mud-encrusted guns.

Clem had lost the taste for his cigarette. ‘Whatever’s best for Han,’ he said, leaning forward to drop it out of the window.

They carried on into the heart of fashionable Paris. Clem marvelled at the crisp geometry of the streets, the monumental ranks of six-storey buildings, the endless rows of tall, identical windows; to one used to the crumbling muddle of London, the effect really was staggering. A neat enamelled sign, its white letters set against a peacock blue ground, informed him that they had reached the boulevard des Capucines, generally considered to be among the most splendid of the emperor’s recent redevelopments. It had been kept free of soldiers, but in their place was an atmosphere of singular desolation. The magnificent shops had their shutters down and their awnings rolled; the gutters were clogged with mud and litter; the strolling, stylish crowds had long since fled. Hardly anyone at all could be seen, in fact, and Clem searched about in vain for a porter when they alighted before the Grand Hotel. Elizabeth went inside directly, pushing apart the heavy glass doors, leaving him to pay their driver and carry the bags.

Clem had friends who swore by the Paris Grand, waxing lyrical about its delightful society and many modern luxuries. That afternoon, though, it was like stepping into the atrium of a failing bank, the air charged with impending disaster. The crystal chandeliers were turned down low to conserve gas. Several of the public rooms had been roped off, the main bar was closed and a sign in front of the lifts informed guests in four languages that they were out of use until further notice. Only a handful of people were passing time there; exclusively male, soberly dressed or in uniform, they conversed quietly over their coffee cups.

Elizabeth was standing by the reception desk with a tallish man at her side. Some way past forty, with a sandy beard, he was wearing a green yachting jacket and shooting boots. He’d just kissed her hand and had yet to release it; she’d adopted a classic, much-employed pose, angling her head carefully to display her nose and jaw-line to their best advantage. Both were smiling.

‘Mr Montague Inglis of the Sentinel,’ Elizabeth said as he arrived before them. ‘Mont, this is Clement Pardy, my son.’

Clem knew the Sentinel. A popular, rather frivolous paper with pretensions to being upmarket, it catered to those who aspired to a life of dandified loafing. He studied Mr Inglis more closely. The journalist’s practical costume was belied by the costly gloss of his boot leather, the expert barbering of his beard and the diamond in his tiepin: the size of pea, this stone was surely worth more than the Pardy family had to its name. Clem set down the bags and the two men shook hands. Inglis’s oar-shaped face was strangely vicarish, but weathered by fast living; his probing, watery eyes appeared to be running through some unknown calculation.

‘Heavens,’ he said, his voice low and slightly hoarse, ‘the last time I saw this young buck he was still messing his britches. First trip to La Ville-Lumière, Clement?’

‘It is, Mr Inglis.’

‘Damn shame – it’ll very probably be your last as well.’ The journalist switched his attention back to Elizabeth. ‘My dear Mrs P, I must insist that you tell me more about why you’ve picked this moment for a visit. You are aware, I take it, that my poor Paris is doomed?’

He said this casually, as if confirming a dinner arrangement. Elizabeth’s response was equally light-hearted; she twisted a dyed curl around her finger as she spoke, resting her elbow against the reception desk.

‘That would seem to be the case, Mont, would it not? Why, in all my travels I have never seen so many blessed soldiers!’

‘Yes, the boulevards have been quite defaced by that godforsaken rabble. Awfully depressing. And the Grand! My God, look at the place! A brilliant company used to assemble here every evening for champagne, billiards, some gossip before the theatre; now they’re all either on the wing or in uniform, out filling sandbags by the city wall.’ Inglis clapped his hands, raising his voice in sardonic triumph. ‘Another capital result for the new republic! Vive la France! Vive la liberté! Bless my soul, I hope that villain Favre and the rest are pleased with what they’ve accomplished.’

Elizabeth’s smile had grown strained. They were political opposites, Clem realised, despite the show of friendship; Inglis was a supporter of the Empire whose collapse at the beginning of the month had brought his mother such satisfaction. This flirtatious performance would only withstand so much before she felt compelled to strike out. Clem decided that he would change the subject.

‘What news of the Prussians, Mr Inglis?’ he asked. ‘How close do the latest reports put them?’

Inglis ignored him. ‘Madam, I do believe that you have yet to answer me. Why are you in Paris? Is it a new project, a new Mrs Pardy volume after all these years of inaction, so tormenting for your public? An account of my city’s final hours, perhaps?’

Elizabeth was being goaded; her laugh had an edge. ‘Goodness no, this is not a writing expedition. I am here for my daughter, Mont. Hannah, Clement’s twin. She lives in Paris – has done so for nearly two and a half years.’

Inglis was unconvinced, but he let the matter go for now. ‘Is she married to a Frenchman? An Englishman with business interests over here?’

‘No, she is not.’

‘A school, then – some manner of ladies’ college?’

Clem dipped his head, squinting at his boots; they looked scuffed and cheap against the Grand’s patterned marble floor. This Mr Inglis knew very well that Han had run away to Paris and was feigning ignorance so that Elizabeth would have to recount the details for him. For all his sociability he was trying to embarrass her.

Elizabeth, however, refused to be embarrassed. ‘Hannah is a painter,’ she said, her nose lifting, ‘of quite extraordinary ability. She came here because she felt that female artists are taken more seriously in France than in England. She had – she has my complete support.’

Inglis took this in. ‘And she wishes to return home, does she, to escape the coming trials?’

‘I honestly don’t know,’ Elizabeth replied, remaining matter-of-fact. ‘She hasn’t contacted us for some months now. But we did receive this.’

She nodded at Clem, who reached inside his jacket for the letter – a single sheet covered on both sides with measured handwriting, making its case, in English, with eloquent directness. Both of them knew it almost word for word. Hannah was out of money, it claimed, friendless and destitute, trapped in Paris as the city faced a devastating ordeal that it might not survive. Her nationality would be no guard against a rain of explosive shells, or the lances of the Uhlans as they charged along the boulevards. They were her last and only chance; if they had any love for her they would go with all haste to No. 34 rue Garreau, Montmartre, Paris. It was unsigned, and offered no clues as to the author’s identity.

‘That is what brought us to Paris, Mont,’ Elizabeth said. ‘That is why we’re taking this risk.’

Inglis skimmed the letter, a corner of the page pinched between his immaculately manicured fingertips. ‘She is in Montmartre,’ he said.

‘A recent change. The address we had for her was in the Latin Quarter. I don’t know why she has moved.’

The journalist handed the letter back to Clem, as one might to a butler. ‘Dear lady, you’re in luck. I’m well acquainted with the 18th arrondissement and would be happy to accompany you on this mission of yours. I was up there only yesterday afternoon, in fact, to pay a call on a photographer I know – an associate,’ he added, ‘of the great Nadar.’

Clem had been hoping that Mr Inglis would reveal himself to be of no use, allowing them to dispense with him and get on with their search alone. Now, though, he regarded the Sentinel’s correspondent with new curiosity. Photography was among his keenest interests; he’d even thought for a while last winter that he might have a proper go at it, until he’d discovered the prohibitive cost of the materials. Still, Nadar was a big beast – among the very biggest.

‘Have you met Nadar, Mr Inglis?’ he enquired, trying not to sound too impressed. ‘Have you been to his studio?’

Again, Inglis acted as if Clem hadn’t spoken. He turned towards the reception desk. No clerk could be seen. There were signs of neglect; dust was gathering in the pigeonholes and the brass counter-bell was dappled with fingerprints.

‘Do you have a reservation?’ he asked Elizabeth.

‘We do, but I doubt we will sleep here. We are intending to be on the early-morning train back to Calais. With Hannah.’

‘Wise, Mrs P, very wise. The Prussians will soon be blocking the railway lines. I understand that it’s an initial stage in the process of encirclement.’ Inglis straightened up. ‘I’m rather surprised, actually, that it didn’t happen this afternoon.’

Clem stared over at Elizabeth. She’d predicted confidently that it would be two more days before the invaders reached Paris. He felt sick, his collar tightening. This was a mistake of epic proportions. What on earth did they think they were doing?

Elizabeth remained composed. ‘Is that possible?’ she asked, sounding only mildly irked by the journalist’s revelation. ‘Can a city that is home to millions really be placed under siege? Is this some kind of joke, Mont?’

Inglis was grinning. ‘No joke, Mrs P, upon my honour. All the experts are agreed. The Prussians are more than capable of organising such an operation. That is why the French have been crushed so absolutely – why their best legions have been knocked to bits in a matter of weeks. This is the modern way, you see. Valour and courage have been displaced by planning and logistics.’

‘It seems improbable, to say the very least.’

‘Perhaps, madam, but the strategies are well established. Roads will be barricaded, batteries built, trenches dug. They’re going to lock us in, starve us down to nothing, and deliver a final humiliation so complete that the new republic will submit to whatever peace terms they propose.’ Inglis struck the counter-bell, its sharp chime cutting through the lobby. ‘The siege of Paris is about to begin.’

Evening had arrived whilst they’d been in the Grand. Ornate cast-iron lampposts lit expanses of empty pavement; a soft autumn mist was drifting down through the denuded trees. Inglis hailed them a cab, stopping to give the driver his instructions as Clem and his mother climbed inside. Elizabeth had entrusted Clem with her notebook; he went to draw it from his pocket and pass it over to her.

‘No, Clement,’ Elizabeth said, ‘I fear that would only provoke him. Lord above, I’d forgotten how trying the man can be. Memory is too forgiving at times.’

‘He isn’t easy to like, I have to say.’

‘Liking him isn’t necessary. He might be able to help us locate Hannah. All we have to do is put up with him until then.’

Inglis folded his long limbs into the cab, settling himself at the opposite end of Clem’s seat. The journalist was in high spirits, glad to have been liberated from the dullness of the Grand. He took a squashed-looking cap from his jacket and stuck it on his head. It was a kepi, he informed them, headwear of choice for partisans of the new republic – which made it an essential item for any man who wished to walk about the city and not be lynched either as a Prussian spy or an Imperialist.

‘The latter,’ he confided, ‘for the shabbier class of Parisian, is by far the more grievous offence.’

They went north, passing through yet more roadside army camps, the fires now casting tangled shadows over the fine buildings behind. Inglis held forth on the incompetence of the new republic, the destructive savagery of the masses, the immense wrongs done to the noble, fallen emperor; Elizabeth stayed very still, gazing out of the window.

Entering Montmartre felt abrupt, like walking behind a section of stage-set. The scale and precision of the boulevards disappeared, the cab creaking its way up into a web of crooked, sloping lanes. No one had fled this district; Montmartre was truly alive that night, crammed with its inhabitants. The mood was oddly jubilant, the erratically lit streets resounding with songs and laughter. Every man was in uniform, but not one worn by any of the regular troops; their simple blue outfits were halfway between those of soldiers and policemen, topped off with a kepi just like Inglis’s. The majority were drinking hard. They dominated the cafés and restaurants, debated on corners and lounged around shop fronts. Countless flags and banners were on display. The tricolour was the most popular – but another, plain red, was so common that it could easily have been mistaken for the standard of a new army, separate from that of France.

‘National Guard,’ Inglis said, his voice loaded with disdain. ‘The Parisian militia. Louis Napoleon had the good sense to suppress them, but they’re back with a vengeance now, claiming that they’re the ones to save the city.’ He pointed at a particularly large red flag, propped above the door of a bar. ‘And as you can see, in humble districts such as this, the units are already thoroughly infected with socialistic doctrine.’

‘The International?’ Elizabeth asked.

‘Among others. Reds of every stripe were all over Paris the moment the emperor was captured, spreading their sedition – sowing disinformation and slander.’ Inglis smiled bitterly. ‘Disaster piled upon disaster.’

The cab became caught in a herd of goats that was being driven into the city from the surrounding countryside. Inglis opened the door, leaned out to survey the brown, bleating backs, and suggested that they continue on foot.

‘I know the way from here, Mrs P,’ he said. ‘It ain’t far.’

Skirting the herd, he led them up a steep alley and across a courtyard. A good deal could be seen of the hilltop village Montmartre had been before it was swallowed by the expanding capital. Many of the houses were little more than cottages; whitewashed walls hemmed in gardens and orchards. Between a butcher and a tool shop Clem caught a glimpse of a broken-down windmill, the sails silhouetted against the darkening sky.

The rue Garreau lay a short distance beyond the courtyard. No. 34 was one of the larger buildings upon it, standing at the junction of two quiet backstreets, its floors stacked untidily like books on a scholar’s desk. A portly, middle-aged woman in a grey dress was climbing down from a stool, having just lit the gas lamp above the door. Noticing their purposeful approach, she wiped her hands on her apron and prepared to meet them. Inglis began to speak, assuming command, but Elizabeth stepped smartly in front of him. They had arrived at Hannah’s address; his usefulness was almost at an end.

Elizabeth bade the woman good evening and launched into a double-time explanation of their presence in Montmartre. Her French had remained remarkably fluent – whereas Clem’s, only ever schoolroom level, had rusted to the point of uselessness. Following the conversation was a struggle, but he managed to grasp that this woman was Hannah’s landlady – a Madame Lantier. Utterly overawed by Elizabeth, she was listening closely to what she was being told, her eyes open wide. She’d realised that they were relations of Hannah’s due to the family resemblance, the blonde hair and so forth, and that they had travelled to Paris to effect a reunion; Elizabeth’s talk of her tenant being in some kind of distress, however, came as a complete surprise.

‘Les Prussiens, oui, c’est très grave, mais Mademoiselle Pardy …’ Madame Lantier shrugged. ‘Mademoiselle Pardy est la même.’

Elizabeth shot Clem a glance; this was not the author of their mysterious letter. She asked another question and an agreement was reached, the landlady nodding as she turned to open her front door.

‘She’ll show us Hannah’s room,’ Elizabeth said. ‘The blessed girl isn’t there, of course – she’s off in the city somewhere. But Madame hasn’t noticed anything wrong at all.’

Clem considered this as they followed Madame Lantier into her hallway. It made sense that she was unaware of his sister’s troubles. Who would want their landlady to know that they were out of cash, if they could possibly help it?

They were taken past the main staircase, through a pristine parlour and outside again, into the walled garden at the rear of the house. The air smelled of autumnal ripeness, of fat vegetables and soil; an abundance of tall plants thronged around a brick pathway, their leaves turning blue in the fading light. Madame Lantier had already started up this path, pushing through the press of vegetation. A little bemused, Elizabeth, Clem and Inglis went after her, holding onto their hats to stop them being dragged from their heads. After a few awkward yards they were back in the open. In front of them, set against the garden’s rear wall, was a small wooden outbuilding. The landlady was at the door, fumbling with keys.

‘Good Lord,’ Elizabeth exclaimed, ‘Hannah is living in a shed.’

The interior reeked of linseed oil, acrid and disagreeable after the sweet scents of the garden. It was dark; the single high window had been firmly shuttered. Clem could just discern a table, a stove, several easels and a number of black rectangles he took to be canvases.

‘Stay where you are, Mrs P,’ instructed Inglis. ‘Madame has found a lamp.’

An oil flame flared, illuminating the modest room and the hoard of paintings it contained. There were views of sunlit boulevards, of cafés buzzing with people, of skiffs on the Seine – of Paris in 1870. The compositions were irregular, lop-sided, done with apparent disregard for both the conventions of picture-making and the symmetries of the remade city. Clem took a few steps towards one of the larger boulevard scenes. The image grew less precise the nearer he got to it. He saw how little detail there was, and how few definite lines; its forms were on the verge of coming apart, of dissolving into each other. Brush marks had been left openly visible throughout. Buildings were pale tracks of grey; trees feathery flurries of green and yellow; the crowds on the pavements nothing but a profusion of intermingled smears. Madame Lantier carried the lamp to the table. The light glistened across the surface of the canvases, catching on tiny beads and ridges of pigment.

‘My dear Mrs Pardy,’ Inglis said, ‘I am so very sorry. Your poor daughter has obviously gone mad. The seedier side of Paris has corrupted her completely.’

Elizabeth had been making an initial survey of the paintings; now she turned on Inglis, dropping all pretence of amity. She would never permit anyone to criticise her children. That right was hers alone.

‘This blinkered response does not surprise me, Mont. How could someone like you possibly appreciate such boldness and originality?’

Inglis appeared unconcerned by this shift in her attitude. He was well used to hostility, Clem perceived – welcoming it, even, as a sign of the merciless veracity of his observations. ‘What is so original, pray, about painting like a drunk with a broom?’

‘This is the real world, not the finely finished fakery of your beloved Empire, with its voluptuous come-hither nudes and slave-market scenes. This is art swept into the present.’ Elizabeth looked over at her son, inviting him to rally to his sister’s defence. ‘Don’t you agree, Clement?’

Clem’s interest in painting was pretty casual, and inclined towards its technical aspects. The only time he’d become truly enthusiastic had been a few years previously when he’d developed a fascination with the actual manufacture of the paint – how the stuff was mixed and squeezed into those metal tubes. He’d even taken a couple of cautious steps towards setting up his own factory, an artisanal operation catering only to the first rank of painters, but the finances had quickly become impossible and he’d been forced to abandon it.

‘They’re very fresh,’ he said.

Elizabeth liked this. ‘Aren’t they? Why, the effect is like a spring breeze – a ray of living sunshine.’ She paused significantly. ‘Pass my notebook, would you?’

Inglis was clearly the sort who picked his battles carefully; sensing a disadvantage, he produced a cigar and pointed to the door. ‘I think I’ll wait outside, Mrs P – all this churning paint is making me nauseous. I’ll be ready when you wish to resume the search.’

Clem handed the notebook to his mother. She started writing straight away, angling the page towards the lamp. ‘I mean they’re recent,’ he enlarged. ‘Not wholly dry. Some are less than a week old, I’d say.’

The room was clean and as orderly as an office. Sketches were stored away in folders, brushes and palette knives in jars, paint tubes heaped in a large cardboard box. A bookcase held a select library – works on art mostly, but also histories and a couple of slim volumes that looked like political tracts. There was no trace either of the corruption Inglis had mentioned or the miserable poverty described in the letter. Off to the side was a Japanese screen printed with a pattern of swooping swallows; behind it Clem could see a mattress, the corner of a battered chest and two winter coats, one black and the other blue, hanging from a nail in the wall. The black one, he realised, was made for a man.

‘Elizabeth,’ he said, ‘I don’t believe that Han is the only person living here.’

His mother followed his gaze. Such a discovery would have left any normal parent mortified, furious, raving about scandal and disgrace. Elizabeth, however, merely blinked; then she turned to study the paintings again.

‘This is how artists are,’ she said. ‘It has always been thus, in Paris especially. Perhaps this friend is the reason she has moved out here, to Montmartre – although of course such a contrary step is typical of her.’

Their eyes met. For all Elizabeth’s offhand tolerance, the same questions were occurring to them both. Was it this other resident, this man, who had written to them? Or was he the true source of danger?

Elizabeth resumed her grilling of Madame Lantier, rather more intently than before; Clem, meanwhile, walked further into the outbuilding, hunting for clues. Several unfinished works were propped away in a corner. Two were portraits: a young woman dressing, and a man sitting beside a window. The style was strikingly intimate and informal. The woman was perched on a wicker chair, a satin ballgown hitched up to her knees. She had an angular, impish face that hinted at an appetite for pleasure of all kinds; her tongue poked out between her lips as she reached for a stocking that lay crumpled on the floorboards. The skin of her bare shoulders had been painted in broad, butter-like strokes, the different tones left unblended beside one another. Just two shades of orange had been used to render her short coppery hair, and the bunched fabric of her gown was but a mesh of purple-pink diagonals.

The portrait of the man had a more considered effect. Clean-shaven and gravely handsome, he was sitting forward on a bench, his thick black hair brushed back from his brow. His coat was black as well, and his gloves; this austere figure, equal parts preacher, lawyer and soldier, had been set against a stretch of plain cream wallpaper, a contrast that fixed the eye upon him completely. In his hand was a slim green tome that Clem recognised as one of the political volumes from his sister’s bookshelf. He was looking out at the viewer, his expression resolute but also reassuring, caring even, as if he was alone with a close comrade-in-arms.

Clem crouched to examine the picture further. Something he had taken to be a flaw, a crack in the paint, was no such thing. A dark scar ran down the left side of the sitter’s face, running like a tear-track from his eye socket to the line of his jaw.

Over by the door, Elizabeth’s voice was growing louder and more impatient. Clem stood up, thinking to go to Madame Lantier’s aid, when he noticed a black strip on one of the other paintings in that corner, behind the two portraits. He pulled it out. Little more than a sketch, largely uncoloured, it depicted what looked like the inside of a small common theatre. An audience had gathered in the murky atmosphere, faces and hats and jackets blurring into an indistinct mass. Before them was an imposing, black-coated orator – the man from the portrait. He’d struck a simple pose, chin raised and right arm extended; his glove was a black V in the middle of the canvas, rendered with a single mark of the brush. Someone, Hannah it looked like, had scrawled a date along the bottom: 12th Septembre, 1870.

Clem held it up for his mother and the landlady to see. ‘Madame,’ he called, ‘où est ça, s’il vous plaît?’

The landlady told them that it was the Café-Concert Danton, a place of indifferent reputation only a few streets away. She pointed to another café scene, saying that it showed the Danton also; and another, over on the far side of the room.

‘We should go there,’ Clem said. ‘Han’s clearly a regular. If we don’t find her we can come straight back.’

Elizabeth agreed. Madame Lantier provided directions and they left the shed at once. Inglis claimed to have heard of the Danton; he slowed his pace, though, dropping to the rear. His usefulness had expired, they all knew it, but he plainly had no desire to return to his lonely table in the lobby of the Grand. Clem suspected that they were stuck with him until they departed the city.

Once on the busier lanes they soon began to attract attention. Clem and Elizabeth’s travelling clothes, although hardly ostentatious, were enough to draw unfriendly stares from nearly everyone they passed. Insults were hissed, the word bourgeois spat out as if it was the worst curse imaginable; children trailed behind them, sniggering and asking rude-sounding questions. Inglis wasn’t nearly as comfortable in Montmartre as he’d implied. His proletarian disguise, with its various quality touches, was largely ineffective; Clem saw him remove the diamond tiepin and secure it inside his jacket.

Madame Lantier’s directions brought them to the place Saint-Pierre, the square at the heart of the district, and on past the derelict merry-go-round in its centre. The northern side of the place had been left empty of buildings, a chain of gas lamps tracing a path up the last stretch of the hill to the signalling tower at its summit. An electric searchlight was trained on this structure; as Clem watched, a soldier stepped into its white beam, waved a series of semaphore flags and then withdrew into the darkness.

The Danton lay to the east, on the rue Saint-André. It was mean and rather dingy – nothing much to look at. Clem felt the deadening cramp of nerves, his breath catching in his throat. He hadn’t seen Hannah for more than two years now, but that wasn’t the reason for his unease. It was more like an intimation of doom – a profound sense that things weren’t going to go as planned. This bothered him. He really wasn’t the sort for such hand-wringing; indeed, he tended not to have the slightest inkling of doom’s approach until he was sunk in it up to his neck. Nothing could be done, at any rate. Elizabeth was steaming past the gaudy street women sitting around the pavement tables and in through the doors. There was no time to reconsider.

Conditions inside were very close to the undignified crush represented in the paintings. The theatre itself was shut, the customers restricted to the narrow bar. A large proportion were National Guard, red flags and all; the rest were clerks, shop assistants, off-duty waiters and waitresses, with a scattering of trollops and pickpockets. Everyone was laughing, singing, arguing at the tops of their voices. Elizabeth jabbed a finger towards one end of the room and then started in the opposite direction, worming between the swaying guardsmen.

Clem pushed on along the bar as politely as he could manage. His ribs, still aching from the Gare du Nord, were barged anew; sour, boozy breath washed over his face as unpleasant comments were muttered; tobacco ash was flicked on his coat and wine splashed on his shoes. Ten minutes passed and he saw no one who looked remotely like an artist, or even like they might know an artist. He’d almost finished his search when a fight broke out nearby among a group of shrieking laundresses, forcing him against the marble bar-top. There was a mirror behind the rows of bottles: Clem contemplated himself as the brawling women were bundled into the street. How bloody wrong I am here, he thought, in my brown flannel and my squat English hat – wearing trimmed whiskers in this land of beards and drooping moustaches. He closed his eyes, sorely tempted to marshal his French and order a large brandy.

Upon opening them he saw someone familiar in the mirror, past his shoulder – a young woman. The image was itself a reflection, he realised, caught in a glass door panel and made especially sharp by the darkness outside. An arm nudged against this panel; it moved very slightly and the woman disappeared. He glanced around, judging the angles. By his estimation she was in a small area beyond the end of the bar. He worked his way towards it.

The woman from the painting was sitting at the edge of a candlelit booth, watching the barroom with an air of total boredom as a cigarette burned between her velvet-gloved fingers. She was almost as alien to the Danton as Clem – a more natural inhabitant of flash dancing halls than the drinking dens of Montmartre. Her dress was dark blue, extremely tight above the skirts and cut low to put as much of her pale flesh on show as possible. The copper hair, longer than in the portrait, was gathered up and adorned with black ribbon and lace. Her legs were crossed carelessly, revealing patent leather ankle boots and a few inches of silk stocking. She noticed Clem, acknowledging him with a beat of her turquoise eyelids. There was sly recognition in her smile. She beckoned for him to approach.

Hannah was in the rear of the booth, engaged in a lively conversation. It was an uncanny moment – gratifying and mystifying in equal measure. Her silver-blonde hair was tied beneath a length of red muslin. She was thinner than Clem remembered, but in a way that suggested vitality and energy rather than privation. And how like them she was! He’d never paid it much mind before, but there in that booth he saw his mother’s oval face and clever grey eyes; the gentle point to the chin that he’d never cared for on himself, but on Hannah was nothing short of beautiful. There was his sister, his twin, for many years his closest friend. He’d found her.

This relief was tempered with disquiet. She was surrounded by men, all of them wearing simple, faded clothes. They looked more like a band of revolutionaries than artists. Han had never been one for gangs, being an impatient, solitary type; yet here she was holding court, telling these moustachioed fellows what was what in French that sounded even better than Elizabeth’s. She didn’t need rescuing, by Clem or anyone else. The letter was a lie. His sister was neither friendless nor destitute; she wouldn’t be leaving Paris, no matter what danger the city might be in. They’d been misled.

The copper-haired woman reached out to Hannah, attracting her attention and jerking a thumb towards Clem. His sister’s astonishment seemed to smack against her, knocking her back in her seat.

‘Dear God!’ she cried. ‘What – what the devil are you doing here?’

The booth went quiet.

‘Well, Han,’ Clem began, ‘with everything that’s going on, it was felt—’

Hannah got to her feet. ‘Please, Clem,’ she said, ‘just tell me she isn’t with you.’

II (#ulink_ce3f406e-cfc4-53f0-a4b3-9053c0697e22)

Hannah took hold of Clement’s lapel and pulled him away from the booth, into a doorway beside the bar. The material was well worn; it was the same coat he’d been using when she went, and it hadn’t been new then. The fortunes of the Pardy household had plainly not improved. He’d started talking in his old manner, rambling on about how very well she looked and how much this place seemed to suit her; hearing and speaking English again after so long felt strange, a little wrong, like walking in someone else’s boots.

‘Shut up, Clem,’ she said, ‘for pity’s sake.’

She considered him for a second: a guileless boy still, largely unchanged by the two years that had passed. His face, freckled by another idle summer, lacked the pinched quality Hannah had grown used to in Montmartre. Poor he might be, but he had food; he had a good bed and an easy mind. A flicker of contempt gave way immediately to guilt. Clement had been her sole regret when she’d fled from London. She’d abandoned her brother to Elizabeth. This could not be ducked or denied. He had every right to resent her – to demand that she explain herself and listen to the suffering he’d endured in her absence – but he was grinning, saying how pleased he was that they’d been reunited, whatever the circumstances. She released his coat.

‘Is she here with you? Answer me.’

Clem’s grin fell. He scratched at his blond whiskers and glanced along the bar. ‘Over there somewhere, I’m afraid. Her blood’s up something awful, Han. You’d better get ready.’

Hannah was glad of the anger that gripped her; it at least dictated a clear course of action. ‘Why have you come? Why now?’

A letter was produced from his coat pocket, written in an official-looking hand. She read it with gathering dismay.

‘But this is quite untrue. It’s nonsense.’

‘Who could’ve sent it, do you reckon?’

Hannah thought hard. This letter was obviously intended to humiliate. The arrival of her family from London at this pivotal time would make her seem like a hopeless ingénue – no different from the hundreds of hare-brained English girls who ran away to Paris every year, only to be retrieved by their relatives. It labelled her a tourist, an outsider, someone not to be taken seriously. The list of suspects was long. She’d learned that camaraderie between artists was a fragile thing, in constant danger of tipping into rivalry. They might share a philosophy of painting, but each one of these professed comrades, in some private chamber of his heart, desired the ruination of the rest. There were others as well; impatient creditors, a handful of rebuffed suitors, and the likes of Laure Fleurot, who’d pointed Clement in her direction with such malevolent delight. Any of them could be responsible.

Ingenuity had been required, of course, both to discover the St John’s Wood address and compose a letter in English. Nobody of Hannah’s acquaintance had ever admitted familiarity with her mother tongue. Translators and draughtsmen could be found throughout the city, though; and besides, who could say what knowledge people chose to keep hidden?

‘I’ve no idea,’ she said.

‘Things are getting bad here though, aren’t they? It’s like the city has been given over entirely to soldiers. I’ve heard that there’s to be a siege, Han – a bloody siege.’

Clem’s experience of Paris had plainly unnerved him. Her brother led a sheltered life, seldom straying from long-established paths; he was singularly ill-equipped to cope with the upheaval that had come to define the city. The past few months had seen wild jubilation at the outbreak of war, the misery of subsequent defeat and then a bloodless revolution, swift and uproarious, unseating an empire in a single day. And now, almost impossibly, events were escalating yet further. The end of Napoleon III had not brought the end of the war he’d started. The Prussians were coming for Paris – set on razing her to the ground, it was rumoured, and then remaking her in their own forbidding image.

Hannah shook her head, remembering Jean-Jacques’s words. ‘These invaders do not see what Paris is,’ she said. ‘They think we’ve been cowed by the fall of the Empire and the destruction of the Imperial armies, but the opposite is true. Our city has been liberated.’

‘Our city? Quite the loyal Parisian these days, Han, ain’t you?’ Clem’s laugh was tense. ‘I mean to say, that’s all well and good, but these Prussian blighters are approaching in their hundreds of thousands. They have guns like you wouldn’t believe. I read in TheTimes that at the battle of Sedan they—’

Hannah wasn’t listening. She looked at the letter – at her address on the rue Garreau. ‘How did you find me? Here in the Danton, I mean?’

Clem stopped; he grinned again, pride in his detective powers displacing his apprehension. ‘Why, from your paintings. This fine establishment features in a good few of them. I asked your landlady about it and she was kind enough to provide directions. Then I recognised that girl, the one in blue, from your portrait of her. Simple stuff, really.’

‘You went into my home? What were you thinking, Clem?’

He became defensive. ‘We were worried, Han. We thought you might be poorly, or starving, or—’

A murmur of excitement spread through the Danton, rippling out from the doors to its furthest corners. Many turned to stare; Hannah overheard a nearby labourer say ‘l’Alsatian’ to his companions. Jean-Jacques had arrived. Two inches taller than the next tallest man, black hat still on his head, he was moving slowly towards the bar, shaking hands and giving nods of acknowledgement. A squad of National Guard pulled him among them, hailing him as a brother as they poured him a glass from their wine jug.

‘I say,’ Clem remarked, craning his neck, ‘isn’t that the black-suited fellow from your paintings – the orator? Is he going to speak?’

Hannah didn’t answer. Exactly how much had her brother deduced? She tried to remember what had been left in the shed – and suddenly realised that if Clem could recognise Jean-Jacques, Elizabeth might be able to as well. A situation too awful ever to be anticipated was unfolding around her. She stepped from the doorway, hurriedly plotting the best path through the crowd whilst trying to think of an excuse that would get Jean-Jacques back outside.

‘What news, Alsatian?’ someone shouted. ‘Where are the pigs now?’

Jean-Jacques addressed the room. His voice, accented slightly by his home province, was not loud, but it blew away the bar’s chatter like a March wind. ‘The latest sightings are of Crown Prince Frederick, crossing the Seine to the south. The Orléans line has certainly been severed.’ The Danton let out a groan. ‘Do not lose heart, friends, it is but a minor loss. The Prussians will be driven back across the Rhine before a single week has passed. We will beat them.’

Those around him managed an embattled cheer, the National Guard raising their glasses to the coming victory; and between the uniformed arms was Elizabeth Pardy, poised to introduce herself to this noteworthy gentleman and ask him about her daughter. Like Clement, she seemed eerily the same – a figure from Hannah’s past transposed awkwardly onto the present. Her hair was tucked up beneath a fawn travelling hat; her expression amiable yet glassy, concealing a deeper purpose. And now Jean-Jacques was turning towards her, listening as she leaned in to speak.

The next Hannah knew she was before them, quite breathless, grasping his left hand in both of hers. There were exclamations of surprise. Elizabeth planted a kiss on Hannah’s cheek; her face was cold and heavily powdered, and the most extravagant praise, in French, was pouring from her lips. It took Hannah a moment to understand that the subject of this laudation was her paintings. She’d expected some overwhelming line, delivered with chilly calmness – a statement of disappointment and distress, perhaps, intended to floor her with shame. She hesitated, completely wrong-footed.

‘Wonderful,’ Elizabeth was saying. ‘Extraordinary, beyond anything I had hoped for. I see what you are doing, Hannah, I see it so clearly. It is close to genius. You are on the verge of something great, my girl. I predict a—’

Hannah recovered her wits. She cut her mother short. ‘You’ve made a mistake,’ she said, in English. ‘That letter is false. I don’t need your help, Elizabeth. Go back to London. Go before it’s too late.’

The alleyway smelled of pears and neat alcohol. It led downhill, away from the rue Saint-André; a stream of inky liquid was crawling through a central gutter. This was Hannah’s short-cut to the rue Garreau, skirting the place Saint-Pierre to the south. She’d covered a dozen yards before she realised that home was useless. Elizabeth knew where she lived. She’d been to the shed and seen what was inside. She could return there at any time.

Hannah stopped beneath a lamp set in a rusted wall bracket. She’d released Jean-Jacques as soon as they’d left the Danton, running off to the right and into her alley. He’d followed, keeping up easily; he was only a couple of yards behind her now. She crossed her arms and glowered at him. His instinct for people was strong; he should have seen through Elizabeth at once, yet they’d been talking quite happily when Hannah had snatched him back. It felt almost as if he’d been an accessory to her mother’s ambush – to that contemptible attempt to disarm her with flattery. He was watching her, waiting for her to speak. Their abrupt exit from the Danton hadn’t perturbed him. Jean-Jacques Allix was a man beyond alarm. Throughout the summer, as France had been shaken to the brink of collapse, Hannah had found this absolute steadiness reassuring. Right then it made her want to knock off his hat.

‘What did she say, Jean-Jacques? What was under discussion?’

He was quiet for a few more seconds. ‘Only you, Hannah,’ he said. ‘Only you.’

His voice was tender; Hannah remembered the day she’d just passed, sitting at her easel on the place de l’Europe with her brushes in her lap, longing for the moment when they would be together again. But she steeled herself. She would not be lulled.

‘I can’t believe she’s here in Montmartre. I can’t believe it.’

‘She told me that she’d come to ensure that you were safe. A mission of mercy.’

‘Elizabeth came to fetch me,’ Hannah snapped, ‘to reclaim her wayward child and return her to London.’ She covered her brow. ‘I fled my family, Jean-Jacques. I climbed from my bedroom window in the dead of night and travelled alone to Paris. There it is. That’s what I am. A runaway.’

Jean-Jacques nodded; up until now, Hannah had let him infer that she was an orphan, without any surviving relatives in England, but he didn’t seem surprised or affronted by the truth. ‘We all must adapt ourselves,’ he said. ‘It is part of life. The timing of this visit is strange, though. Surely any person of sense can see that there’s a good chance of becoming trapped – that our foe is nearly upon us?’

Hannah sighed; she calmed a little. ‘An anonymous letter was sent to London. It informed her that I was in urgent trouble and needed to be collected before the Prussians arrived.’

Jean-Jacques considered this. ‘A low trick,’ he said. ‘The act of a coward. Do you know who was responsible?’

‘I have my suspicions.’

‘Your mother has been cruelly deceived – fooled into coming to Paris at a most hazardous time. You must be worried for her.’

Hannah glanced at him; his humour could be difficult to detect. ‘That woman is why I am in France. It was her manipulations, her interferences and lies, that drove me from my home. And she is more than capable of looking after herself. Why on earth should I worry for her?’

Jean-Jacques looked away; a line appeared at the side of his mouth. ‘You’re right,’ he said. ‘She’ll be well. Bourgeois like her always are. A haven will be found. She’ll wait out the assault in perfect safety.’

A barrier ran through the population of Paris, according to Jean-Jacques and his comrades, separating the bourgeoisie from the workers. It rather pleased Hannah to hear Elizabeth placed on the wrong side of their great boundary; it gave her a sense that she had allies, not least Jean-Jacques himself. Directly next to this, however, sat the uncomfortable knowledge that but for a change of clothes and lodgings she was certainly as bourgeois as her mother.

‘Such a simple path would never do for Elizabeth. She isn’t one to hide away.’ Hannah paused. ‘It doesn’t matter, at any rate. She’ll have to leave Paris. She hasn’t any money. A stay in a hotel, even for a single night, is completely beyond her means. To be quite honest, I’m surprised that she managed to find enough for her and Clem’s passage.’

Jean-Jacques had been gazing at the surrounding rooftops, his hands in his pockets; now his dark eyes flicked back to her. ‘Clem?’

Hannah cursed under her breath; she was being careless. ‘Clement,’ she admitted, ‘my twin brother. He lives with Elizabeth still, back in London. And has come to Paris today.’

‘You have a twin brother.’ Jean-Jacques said this with gentle wonderment. The line at the side of his mouth deepened again. ‘Another of Hannah’s secrets is revealed.’

‘It is not what you might think. He and I, we are too different to—’

Hannah gave up. It was no use. Everything was overturned. In the space of ten minutes the life she’d crafted in Paris had been irreversibly altered. Jean-Jacques had found out that she’d misled him and had glimpsed the troubles of her past. The Danton regulars, her supposed friends, would be extracting all they could from poor Clem; they’d probably discover even more than Jean-Jacques had. She’d been exposed. Whatever chance she’d had of being taken on her own merits was gone. She might as well walk back to the Danton and surrender herself to Elizabeth. Her mother had won. She leaned against a wall, pressing her damp palms against her forehead. She was finished in Paris.

‘Hannah,’ said Jean-Jacques. ‘Look there.’

Lucien and Benoît, two of the painters she’d been talking with when Clem had appeared, were strolling past the alley mouth: thin men smoking short cigars, sharing a drunken laugh as they headed towards the place Saint-Pierre. Octave, a sculptor, was a few feet behind. Hannah straightened up. Clem might be with them. She strode past Jean-Jacques, back out onto the rue Saint-André. There was no sign of her brother; the painters, however, gave a ragged roar of salutation.

‘Why, Mademoiselle Pardy,’ Lucien proclaimed, twisting his moustaches, ‘what the devil is going on? You leap from the middle of a really quite stirring account of Courbet’s decline to converse with a young gentleman who, from the brilliant yellow of his hair …’

‘The delicacy of his nose and brow,’ inserted Benoît, who fancied himself a portraitist, ‘the fullness of his lips …’

‘… can only be your brother. And then, even though this fellow has come all the way from the soot and smoke of London, you run from him after a few seconds, grabbing the fine Monsieur Allix for a – a turn beneath the stars, I suppose I should call it, for the sake of decency …’

‘… leaving your brother entirely alone: a whiskery Anglais in an old suit, adrift in the Danton, too scared even to bleat for help.’

Lucien’s cackle would have curdled milk. ‘So we wave him over. What else could we do for the brother of such a dear friend? I have a little English,’ he confessed with a modest shrug, ‘sufficient, at any rate, to learn that he is not the only member of the Pardy family in Montmartre tonight. There is a mother also, standing at the bar. A woman who, although undoubtedly mature, is still worthy of the attentions of any man who—’

‘Enough.’