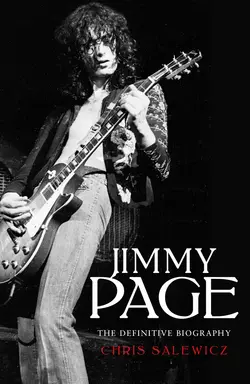

Jimmy Page: The Definitive Biography

Chris Salewicz

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Музыка

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1555.94 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Founder of one of the most influential and successful rock bands of all time, legendary Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page has nevertheless remained an enigma. In this definitive and comprehensive biography of his life so far, Chris Salewicz draws on his own interviews with Page and those closest around him to unravel the man behind the mystery.Having sold over 300 million copies worldwide, Led Zeppelin was the biggest band of the ’70s and has been loved by the legions ever since. From his own conversations with Jimmy, the rest of Led Zeppelin, old girlfriends, tour managers and session musicians to name but a few, Salewicz reveals the many trials and tribulations which transformed the middle class boy from the Surrey suburbs into one of rock’s most enigmatic frontmen.Detailed, thrilling and expertly researched, Salewicz discovers a man who was prepared to die for his art; who justified heroin use so he could harness its narcotic focus whilst making albums, and who overcame numerous death threats during this time. A warrior magician, Salewicz delves into the many skeletons and eccentricities in Page’s closet, contextualising him against a background of London gangsters, deaths, and power struggles which Page has continued to rail against to this day, even within his own band.As entertaining as it is insightful, and from a writer who experienced first-hand the Led Zeppelin furore, this promises to be as close to a Jimmy Page autobiography as fans can get.