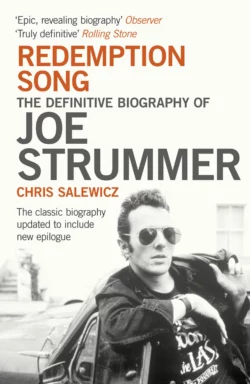

Redemption Song: The Definitive Biography of Joe Strummer

Chris Salewicz

The definitive biography of Joe Strummer, released with a new epilogue to mark the 60th anniversary of his birth.Chris Salewicz was an intimate friend of Strummer’s for over 25 years. Drawing on more than 300 interviews with family, friends and associates, this is a comprehensive, compelling insight into the man behind The Clash.The Clash was the most influential band of its generation, producing punk anthems including ‘London Calling’, ‘White Riot’ and ‘Tommy Gun’. For countless fans across the world, they are the ultimate iconic mainstays of their generation.With his talent, extreme good looks and laid-back attitude Joe Strummer was the driving force behind the band: he was the archetypal punk frontman. His untimely death in December 2002 shook the world to its core.Written with full approval and co-operation of relatives, companions and fellow musicians, this is the ultimate account of one of British rock & roll’s most fascinating idols: his life, his work and his immeasurable impact on the world.Redemption Song is the best and last word on the subject.

Redemption Song

The Definitive Biography of Joe Strummer

Chris Salewicz

CONTENTS

COVER (#ubb96c034-9e9e-5a92-ab03-7ee01eb10641)

TITLE PAGE (#u688326b1-2aa0-54cc-ba7e-f46bf0578019)

1 STRAIGHT TO HEAVEN (#ue275f90c-933d-5c7c-aa55-0ec77dba0c8d)

2 R.I.PUNK (#u2a3a8da0-a298-546d-b209-248f8d07d22f)

3 INDIAN SUMMER (#uf698214c-bf0c-56ac-b46a-50c836472f9a)

4 STEPPING OUT OF BABYLON (ONE MORE TIME) (#u19b2ee0f-c82c-5d46-a1e6-2fe0cf0d1725)

5 BE TRUE TO YOUR SCHOOL (LIKE YOU WOULD TO YOUR GIRL) (#uf1060371-6864-5445-b190-b5f51c768861)

6 BLUE APPLES (#ue91070e4-170c-5b7e-a6b5-310adeafb3ae)

7 THE MAGIC VEST (#u2e1e3aaf-abac-5ee1-bdd4-b371b6fe8cfb)

8 THE BAD SHOPLIFTER GOES GRAVEDIGGING (#u054f85d3-4b8e-5881-9847-eafee3225c64)

9 PILLARS OF WISDOM (#u65a6a49e-21dd-5b4f-970a-c60be2052e74)

10 ‘THIS MAN IS A STAR!’ (#u31b0cbb7-359e-5d3d-af91-9a2a2146772c)

11 I’M GOING TO BE A PUNK ROCKER (#ufdd3c3a4-1de6-5647-af8a-c99d29c7661f)

12 UNDER HEAVY MANNERS (#u5285ba8d-e5db-5286-acf1-83afdc13cc89)

13 THE ALL-NIGHT DRUG-PROWLING WOLF (#ub1bcebc9-e22c-5cdd-b230-d44c96bae32b)

14 RED HAND OF FATE (#udcecb446-03f2-5339-85cd-9382f2af5fc4)

15 NEWS OF CLOCK NINE (#uf2d5e115-a077-538f-b014-9314ce71670a)

16 1 MAY TAKE A HOLIDAY (#ua0294afe-915c-5139-a8d9-6a574e700211)

17 THE NEWS BEHIND THE NEWS (#u3753dd34-1932-5188-a67d-1623532a6dc2)

18 ANGER WAS COOLER (#u3d134930-0198-501c-9e97-1afffc63cef1)

19 SPANISH BOMBS (#u363998a1-c378-5c94-87c7-a573831bb1ec)

20 MAN OF MYSTERY (#u701316b6-aa84-5003-9cc9-558b81d573ce)

21 SOLDIERS OF MISFORTUNE (#u9aed0838-3bb5-5e9f-9138-ce215135c7d7)

22 ON THE OTHER HAND … (#u56c47a3f-3ddf-5d1e-845f-a4a394a4727e)

23 THE RECKLESS ALTERNATIVE (#uc42b0d20-0346-5c11-a072-9542ced031ef)

24 THE COOL IMPOSSIBLE (#u92ddd3c1-9b35-5ef2-ba82-4e515726cb29)

25 THE EXCITEMENT GANG (#u526d76e8-c10f-53f8-b618-f24e0059dde7)

26 LET’S ROCK AGAIN! (#uf21e2d9c-1056-5f3f-a29c-ab815ed7e44f)

27 CAMPFIRE TALES (#uc850a8c2-5fa1-5f6c-b613-c1c49a4a1309)

28 BRINGING IT ALL BACK HOME (#uc5bf346b-deaa-50d4-b545-e2b64791b481)

29 CODA (THE WEST) (#u21e25abf-21b3-5e05-8d5a-9ea8893ad861)

EULOGY (#u42208c71-c5a9-5f9d-ad2c-fd6514306564)

PICTURE SECTION (#uc2686b1c-fb30-5b94-a7da-7872664fa27a)

INDEX (#uae644e67-1cf6-5fe3-8fe0-f65ac1d87731)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#u06d33e66-ec96-523a-9fb3-89775fd272c6)

PRAISE FOR CHRIS SALEWICZ’S REDEMPTION SONG (#u5e3642ec-7c6f-505c-8eed-8fa4b8606400)

BY THE SAME AUTHOR (#u91156a0c-b627-5635-8028-e3d74fef0646)

ROOTS OF HEATHEN (#u05d14e46-ed91-5a72-a6a8-18c285a52cfc)

COPYRIGHT (#ubd0322b3-9d2e-5305-b98e-89185d0a73ec)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#u7abacbb1-78b3-53cf-ad04-53594bcca10f)

1

STRAIGHT TO HEAVEN

2002

This is how I heard about Joe’s death: Don Letts, the Rastafarian film director who had made all the Clash videos, called me at around 9.30 on the evening of 22 December 2002.

‘I’ve got to tell you, Chris: Joe’s died – of a heart attack.’

‘Oh-fuckin’-hell-Oh-fuckin’-hell-Oh-fuckin’-hell,’ was all I could say.

I poured a large glass of rum and stuck Don’s documentary about the group, Westway to the World, on the video. I called up Mick Jones, who in between sobs was his usual funny self, telling me how glad he was he’d played with Joe at the benefit for the Fire Brigades Union five weeks before.

‘I don’t even know what religion he was,’ Mick said.

‘Some kind of Scottish low-church Presbyterian, I imagine,’ I suggested.

‘Church of Beer, probably,’ laughed Mick, tearfully.

I went to bed late, and although I hardly slept I didn’t get up until around 9.30. At around 9.55 the phone rang: ITN News. Could they interview me for the 10.00 bulletin? I sat down on the sofa and made some quick soundbite-sized notes. I’m not even sure what I said. The phone rang again: the Independent wanted me to write an obituary, a long one, 2,000 words, by 4 o’clock. I started up the computer, opening up my assorted Strummer files, pulling out quotes and phrases. Then the phone rang once more: ITN News again. Could they send a car for me to be on the 12.30 News? Call me back in a minute, I said: I need to work out whether I can do it – the obituary is what counts most. I put the phone down. Someone’s got to do this for Joe, I thought, but I don’t want to blow the obit by doing too much. I called Joe’s home in Somerset and left a message of condolence for Lucinda, his widow.

By the time the car came for me at half eleven, I’d got a good amount done. As it always does, the TV stuff took much longer than it was meant to – they wanted to record something more for the evening news. It was 2.00 p.m. before I was home again. I still had a lot to do. But somehow time stretched, giving me many more minutes an hour than I might have expected. I e-mailed the obituary through at ten minutes to four. This is what I wrote:

The job of being Joe Strummer, spokesman for the punk generation and front-man for the Clash, never sat easily with the former John Mellor. Always prepared to give of himself to his fans, he still felt a weight of responsibility on his shoulders that often made him crave anonymity, as much as the natural performer within him needed the spotlight.

But when – after a hiatus of almost a decade and a half – he returned to recording and performing with his new group the Mescaleros in 1999, it was business as usual: seemingly the same huge amounts of energy, passion and heart-on-sleeve belief that were his trademark with the Clash and that drew a worldwide audience for him and the group. After a show the dressing-room or backstage bar still would be crammed with fans and friends as Joe held forth on the issues of the day, in his preferred role of pub philosopher and articulate rabble-rouser for the dispossessed. (But even here was the endless paradox of Joe Strummer: he could argue the case for Yorkshire pitworkers or homeless Latinos in Los Angeles, but if obliged to reveal himself through any interior observation, he would generally freeze. Even other members of the Clash would complain about his hopelessness at soul-baring.)

Yet when he played a show at London’s 100 Club two years ago, he was so exhausted afterwards that he had to lie down on the floor of the dressing-room: his Mescaleros’ set included a good percentage of Clash songs, and you worried that the frenetic speed at which they were performed would test the health of a man approaching his fiftieth birthday. In an irony that Joe Strummer no doubt would have appreciated, his death last Sunday afternoon came not from the stock rock’n’roll killers of drugs, drink or travel accidents, but after taking his dog for a walk at his home in Somerset: sitting down on a chair in his kitchen, he suffered a fatal heart attack. [I later learnt it was in his living-room, and it was ‘dogs’, not ‘dog’.]

Neither of his parents had lived to a ripe old age. Joe Strummer, who earned his sobriquet from his crunchy rhythm guitar style, was born in Ankara, Turkey, in 1952 to a career diplomat. Christened John Graham Mellor, he was sent at the age of ten [nine] to a minor public school, the City of London Freemen’s School at Ashtead Park in Surrey. He had already lived in Cairo, Mexico City (‘I remember the 1956 earthquake vividly; running to hide behind a brick wall, which was the worst thing to do,’ he once told me) and Bonn. Strummer’s father’s profession of career diplomat didn’t arise from any position of privilege – quite the opposite, in fact. ‘He was a self-made man, and we could never get on,’ said Strummer. ‘He couldn’t understand why I was last in every class at school. He didn’t understand there were different shapes to every piece of wood, different grains to people. I don’t blame him, because all he knew was that he pulled himself out of it by studying really hard.’

All the same, such a background was not especially appropriate in the mid-1970s punk world of supposed working-class heroes, which may explain why Strummer always seemed even more anarchic than his contemporaries. Mick Jones, like Strummer a former art-school student, discovered Joe when he was singing with squat-rock R’n’B group The 101’ers, and poached him for a group he was forming called the Clash, becoming his songwriting partner: matched to Jones’s zeitgeist musical arrangements, Strummer’s lyrics were the words of a satirical poet, and often hilariously funny – one of his first creative contributions on linking up with Mick Jones was to change the title of a love-song called ‘I’m So Bored with You’ to ‘I’m So Bored with the USA’. Verbal non-sequiturs were a speciality: his gasped aside of ‘vacuum-cleaner sucks up budgie’ at the end of ‘Magnificent Seven’, inspired by a newspaper headline on the studio floor, is one of the funniest lines in rock’n’roll.

Strummer had one brother, David, who was eighteen months older than himself. By the time he reached sixteen, the younger boy had become accustomed to his brother’s far-right leanings – he had joined the National Front – and to the fact that he was obsessed, ‘in a cheap paperback way’, with the occult. Was it this unpleasant cocktail that led David to commit suicide? Whatever, it was clearly a cathartic moment for his younger brother: Joe Strummer often seemed overhung by a mood of mild depression, a constant struggle.

After dropping out of Central College of Art (‘after about a week,’ [he lied about this]), he threw himself into the alternative world of squatting. Moving for a time to Wales, he spent one Christmas on acid listening to Big Youth’s Screaming Target classic and so discovered reggae. One of the main themes propagated by the Clash was the rise of a multi-cultural Britain; in the group’s early music reggae rhythms jostled with an almost puritan sense of rock’n’roll heritage; as the group progressed, it osmosed and absorbed Latin, blues and early hiphop sounds, with Strummer’s never-less-than-heartfelt lyrics making him a modern-day protest singer, in a tradition stretching back to Woody Guthrie.

Positive light to the darkness of the Sex Pistols, the Clash released an incendiary, eponymously titled first album in 1977, the year of punk, a Top Ten hit. With Strummer at the helm, the group toured incessantly: at a show that year at Leeds University, he delivered the customary diatribe of the times: ‘No Elvis, Beatles or Rolling Stones … but John Lennon rules, OK?’ he barked, revealing a principal influence and hero of his own. The next year, after a night spent at a reggae concert, he wrote what he himself felt was his finest song, ‘White Man in Hammersmith Palais’, a blues-ballad that opened up the musical gates for the future of the group. In that song, however, was contained the seeds of a paradox that would become more and more uncomfortable for Strummer: one line spoke of ‘new groups … turning rebellion into money’. Through writing such outsider lyrics, he became a millionaire; his problem was one common to many radical figureheads: how do you remain a folk hero when you have succeeded in your aim and are no longer the underdog? Touring the country that summer of 1978, the group’s concerts were shot for a feature film, Rude Boy, directed by David Mingay and Jack Hazan. ‘He already seemed to be suffering terribly from the notion of being Joe Strummer,’ said Mingay. ‘He wasn’t exactly lying back and having a great time. Joe was always full of contradictions, one of which was that he managed to be both ultra-British and anti-British at the same time.’

With London Calling, their third album, the group achieved commercial American success. Sandinista!, a sprawling three-record set, followed. When it became clear that the album was commercial folly, Joe Strummer demanded the return of their original manager, Bernard Rhodes, a business colleague of Malcolm McLaren and someone with whom Mick Jones had always had an awkward relationship. With Rhodes’s sense of wily situationism powering the group, the potential disaster of Sandinista! was turned into a triumph after the group played seventeen nights at Bond’s in New York’s Times Square. The group were the toast of the town, and only a big commercial hit stood between them and superstardom.

That came in 1982 with Combat Rock, a huge international success, selling five million copies. Strummer bought a substantial terrace house in London’s Notting Hill, yet seemed to feel obliged to justify this possession by explaining that it reminded him of the houses in which he used to squat. By 1983, the Clash had begun to disintegrate; first, heroin-addicted drummer Topper Headon was replaced; then, extraordinarily, Mick Jones was fired, Strummer having gone along with Rhodes’s perversely iconoclastic desire to get rid of the founder of the group. New members were brought in, but the Clash finally fizzled out in 1986.

Strummer’s sense of guilt over the sacking of Jones developed to a point of almost clinical complexity. In the late summer of 1985 he asked me to go for a drink with him. After much alcohol had been consumed, he suddenly announced: ‘I’ve got a big problem: Mick was right about Bernie [Rhodes].’ He had finally realized he had been manipulated. He caught a plane to the Bahamas, where Mick Jones was on holiday: an ounce of grass in his hand, he sought out the guitarist’s hotel, and presented him with this tribute, asking to get the Clash back together. But it was too late: Jones had already formed a new group, Big Audio Dynamite; although Joe Strummer ended up co-producing BAD’s second album, his own plans came to nothing.

A familiar figure on the streets and in the bars of Notting Hill, Joe Strummer was mired – as he later admitted to me – in depression. He tried acting, with a passable role in Alex Cox’s Straight to Hell (1987), and a minor part in the same director’s Walker (1987), for which he also wrote the music; he made a much more significant impression in 1989, playing an English Elvis-like rocker in Jim Jarmusch’s Mystery Train. That same year he released an impressive solo album, Earthquake Weather, and toured. But apart from briefly filling in as singer with the Pogues, he was hardly heard of again. For a time Tim Clark, who now manages Robbie Williams, attempted to guide his career. ‘He was obviously in bad shape,’ Clark told me. ‘He’d turn up for meetings the worse for wear. You could see he was going through a bad time, but you also felt there was probably no one he could really talk to about it.’

After moving out of Notting Hill to a house in Hampshire – he had become worried about his two daughters, he said, after one of them found a syringe in a west London playground – he subsequently split up with his long-term partner Gaby. Remarrying in 1995, to Lucinda Tait, and moving to Bridgwater in Somerset, Joe seemed to find a relative peace. He formed the Mescaleros and began recording again, releasing two excellent albums, Rock Art and the X-Ray Style (1999) and Global A Go-Go (2001), that title a reflection of his interests in world music, about which he presented a regular show on the BBC’s World Service. Strummer was once again touring, incessantly and on a worldwide basis: he was playing to sold-out audiences, with a set that contained a large amount of Clash material. ‘All that’s happening for me now is just a chancer’s bluff,’ he told me in 1999. ‘This is my Indian summer … I learnt that fame is an illusion and everything about it is just a joke. I’m far more dangerous now, because I don’t care at all.’

One of Joe Strummer’s last concerts was at Acton Town Hall last month, a benefit for the Fire Brigades Union. Andy Gilchrist, the leader of the FBU, was apparently politicized after seeing the Clash perform a ‘Rock Against Racism’ concert in Hackney in 1978, and had asked Strummer if he would play the Acton show. That night Mick Jones joined him onstage, the first time they had performed live together since Jones had been so unfairly booted out of the Clash. ‘I nearly didn’t go. I’m glad I did,’ said the guitarist, the poetry of that reunion clear to him.

Bitterly critical that the present Labour government has betrayed many of its former ideals, Joe Strummer was delighted at the show for the firemen; a smile came over his face at the idea that, if only tangentially, his former group was still capable of causing discomfort for those in power. His death, however, comes as a deep shock. After considerable time in the wilderness, Joe Strummer seemed to have reinvented himself as a kind of Johnny Cash-like elder statesman of British rock’n’roll, a much-loved artist and everyman figure. ‘I still thought he’d be doing this in thirty years time,’ said his friend, the film director Don Letts.

2

R.I.PUNK

2002

Christmas Day 2002. Driving through south London, I am wondering if Joe Strummer had known how much people loved him. Pulling up at traffic lights, I glance to my left; there, spray-painted across a building in large scarlet letters, seems to be some sort of answer to my meditations: JOE STRUMMER R.I.PUNK. I call Mick Jones and leave a message, telling him what I’d seen. Joe’s funeral, eight days after he died, polarized all my thoughts and feelings. The following day I wrote this:

Monday, 30 December 2002

The sky is a slab of dark, gravestone grey; rain belts down in bucketfuls, leaving enormous pools of water on the roadside: Thomas Hardy funeral weather. Ready for the funeral’s 2.00 p.m. kick-off, I find myself at the entrance to the West London crematorium on Harrow Road. A voice calls to me from one of the parked cars: it is Chrissie Hynde and Jeannette Lee (formerly of PIL, now co-managing director of Rough Trade, a punk era girlfriend of Joe). Chrissie is clearly in a bad state. ‘Not great,’ she answers my question.

On the main driveway I bump straight into the music journalist Charles Shaar Murray and Anna Chen, his girlfriend: he looks fraught. It is pouring with rain. I take a half-spliff out of my jacket pocket and light it, take a few tokes, and hand it to Charlie. Out of the hundreds of hours I had spent with Joe I don’t think I had been with him on a single occasion when marijuana had not been consumed, so it seems appropriate, even important, to get in the right frame of mind to be with him again.

The spliff is still burning when I see massed ranks of uniformed men. Not police, but firemen, two ranks of a dozen, standing to attention in Joe’s honour. With Charlie and Anna, I walk between them. Standing under the shelter of a window arch I see Bob Gruen, the photographer, and walk over to him. We hug. Then Chrissie and Jeannette arrive; Jeannette and I hug. Soon Don Letts also arrives. I roll him a cigarette.

Suddenly it seems time to walk inside the building, into the main vestibule. That’s where everyone has been waiting. I see Jim Jarmusch, who directed Joe in Mystery Train, Clash road manager Johnny Greene, and – next to him – the stick-thin, Stan Laurel-like figure of Topper Headon. We hug; there is a lot of hugging today. Against the wall I see an acoustic guitar, covered in white roses, really beautiful. In its hollowed-out centre is a message: R.I.P. JOE STRUMMER HEAVEN CALLING 1952–2002. A large beatbox, next to it, is similarly covered in white roses. All the seats in the chapel are full. I find a gap against the rear wall. A lot of people are snuffling.

Then the sound of bagpipes sails in through the door, lengthily, growing nearer. (Later I learn that the music is The Mist-covered Mountains of Home, also played at the funeral of President John F Kennedy.) At last Joe’s coffin slowly comes in, held aloft by half a dozen pallbearers. It is placed down at the far end of the chapel. Keith Allen, the actor and comedian, steps forward and positions a cowboy hat on top of it. There’s a big sticker on the nearest end: ‘Question Authority’, it reads, then in smaller letters: ‘Ask Me Anything’. Next to it is a smaller sticker: ‘Vinyl Rules’. On the sides of the coffin are more messages: ‘Get In, Hold On, Sit Down, Shut Up’ and ‘Musicians Can’t Dance’. Around the end wall of the chapel are flags of all nations. More people are ushered in, like the kids Joe would make sure got through the stage-door at Clash gigs, until the place is crammed. In the crush I catch a glimpse of Lucinda, Joe’s beautiful widow: she carries herself with immense dignity but – hardly surprisingly – has an aura of almost indescribable grief, pain and shock. People are standing right up by the coffin. The aisle is packed: suddenly a tall blonde woman, looking half-gorgeous, a Macbeth witch, is pushed through the throng, to kneel on the stone floor at the front of the aisle – it’s not until later on that I realize this is Courtney Love.

The service begins. I don’t know who the MC is, a man in his late fifties, a vague cross between Gene Hackman and Woody Allen. He’s good, tells us how much love we are all part of, stresses how honoured we are that our lives were so touched by Joe, says that he’s never seen a bigger turn-out for a funeral. (There is a sound system outside, relaying the proceedings to the several hundred people now there.) Then he says we’ll hear the first piece of music, and we should turn our meditations on Joe: it is ‘White Man in Hammersmith Palais’.

Paul Simonon gets up to speak. He tells a story about how when the Clash first formed in 1976, he and Joe had been in Portobello Road, discussing the merits of mirror shades, as worn by Jimmy Cliff in The Harder They Come. If anyone showed you any aggro while you were wearing such a pair, Joe decided, then their anger would be reflected back at them. Immediately he stepped into a store that sold such sunglasses. Paul didn’t follow: he was completely broke, having been chucked off social security benefits; Joe, however, had just cashed that week’s social security cheque. He came out of the store wearing his brand-new mirror shades. Then they set off to bunk the tube fare to Rehearsal Rehearsals in Camden. As they walked towards Ladbroke Grove tube station, Joe dug into his pocket. ‘Here,’ he said, ‘I bought you a pair too.’ Although Joe was now completely broke and with no money to eat for three days, he’d helped out his mate. This story increases the collective tear in the chapel.

Maeri, a female cousin, gets up to speak. Joe’s mother had been a crofter’s daughter, who became a nurse and met Joe’s father in India during the war. Joe’s dad liked to have a great time: a real rebel himself, it seems, not at all the posh diplomat he has been made out to be, a man who pulled himself up by his bootstraps. We are told a story about Joe as a ten-year-old at a family gathering: he is told that he can go anywhere but ‘the barn’; immediately he wants to know where ‘the barn’ is. Then another female cousin, Anna, reads a poem, in English, by the Gaelic poet Sorley MacLean.

Dick Rude, an old friend of Joe’s from LA who has been making a documentary about the Mescaleros, speaks. Keith Allen reads out the lyrics of a song about Nelson Mandela, part of an AIDS charity project for South Africa organized by Bono of U2, that Joe had just finished writing. A Joe demo-tape, just him and a guitar, a slow blues-like song, is played. And the Mescaleros tune, ‘From Willesden to Cricklewood’. The MC suggests that as we file past the coffin to leave, we say a few words to Joe. ‘Wandering Star’ begins to play. ‘See you later, Joe,’ someone says. Yeah, see you later, Joe.

After the extraordinary tension that has built up to the funeral since Joe’s death eight days ago – my sleep is disturbed and troubled the night before the service – it feels like a release when the service concludes. (I have felt Joe around ever since he passed on: Gaby, his former long-term partner, has felt the same thing, she tells me on the phone the previous Friday, and I tell her that a mystic friend of mine has spoken of Joe ‘ascending’ very clearly – according to Buddhism, there is a period of forty-eight days following a death before the soul returns in another form; Gaby feels the same, saying she feels he is very at peace; job done, on to the next incarnation. Until someone reminds me, I have forgotten that Gaby has had plenty of experience of death, her brother having committed suicide while she was still with Joe – as his brother did.) Somehow I expect almost a party atmosphere outside the chapel, with the sound system maybe blaring out some Studio One. But everyone is wandering around in a daze. The wake is being held at the Paradise bar in nearby Kensal Rise.

Outside the Paradise a bloke in a suit and black tie asks if I have any change so he can park his car. He looks familiar; it is Terry Chimes, the original Clash drummer, who had resigned from the group after making the first album, leaving the way open for Topper Headon. Terry is now a superstar of chiropractry, giving seminars on the subject.

The bar is packed with people and a grey atmosphere of grief. I see Lucinda and hold her for a moment. Simultaneously she feels as frail as a feather and as strong as an oak beam. But she is clearly floating in trauma. I tell her how sorry I am, and as I speak my words feel inadequate and pathetic. From a stage at one end speakers are batting out reggae. The pair of pretty barmaids are struggling with the crush. I am handed a beer, which I down, pushed into a corner. I see a woman with a familiar face: Marcia, the wife of Jem Finer, effectively leader of The Pogues – I used to enjoy spending time with them at evenings and parties at Joe’s house when he still lived in Notting Hill. I am incredibly flattered by what she says to me. She says, ‘Joe always used to say that you were the only journalist he trusted. And he said he loved you as a friend. He really loved you.’ I am unbelievably touched by this. I want to talk to her more, but she is clearly looking for someone. I nearly burst into tears when what she has said fully registers with me. (I’m not unusual in being in such a state: all around me I see men putting their hands to their eyes, sobbing for a few moments.) Later Jem Finer, Marcia with him, deliberately seeks me out and tells me this again, both of them together this time.

Next to the cloakroom I find a couple more rooms, where food has been laid out. I grab a plate: smoked salmon, feta cheese salad, pasta – good nosh. And sitting down I find a middle-aged woman. The sister of Joe’s mum, and a great person, Sheena Yeats now lives in Leeds, where she teaches at the university. She’s very Scottish, however: ‘Well, this is the best funeral I’ve ever been to,’ she burrs, with a smile. ‘Joe would have really appreciated it.’ She tells me how Joe had been up to Scotland a month ago, to a wedding, and that he had been in touch with everyone in his family recently. She reminds me that Joe’s mum Anna had passed on in January 1987. ‘Although he chose to call himself Joe, because it was such an everyman name, his real name was John, a name with the common touch,’ she explains.

Bob Gruen tells me how Joe had been in New York a couple of months ago, in some bar, leading the assembled throng in revelry and having a great time. Seated nearby is Gerry Harrington, a Los Angeles agent who had guided Joe’s career when he was working on Walker and Mystery Train and releasing 1989’s Earthquake Weather. Joe had written a song for Johnny Cash last April, at Gerry’s house in LA, entitled ‘Long Shadow’: he plays it for me on an I-Pod, an extraordinary valedictory work that could have been about Joe himself, with lines about crawling up the mountain to the top.

I talk to Rat Scabies, former drummer with the Damned. He tells me he and Joe had been working together in 1995 on the soundtrack of Grosse Pointe Blank, but that they fell out over that hoary old rock’n’roll chestnut – money. ‘I was stupid,’ he admits. ‘I thought I knew everything from playing with the Damned. But working with Joe was like an entirely new education. He understood how to trust his instincts and go with them every time. I couldn’t believe how fast he worked.’

I run into Mick Jones. He puts his arms around me and kisses me on the cheek. We hold each other. He tells me how he’d loved the message I’d left on his voice-mail after seeing the JOE STRUMMER R.I.PUNK graffiti on Christmas Day; it had touched Mick as deeply as it touched me. He tells me how great the Fire Brigades Union have been, and that the police have behaved similarly. At the Chapel of Rest where Joe had been laid in Somerset a sound system had blared out 24-7. When the police came round in response to complaints from neighbours, and were told it was Joe who was lying there, instead of telling them they must turn down the music they responded by placing a permanent two-man unit outside the chapel: a Great Briton getting a fitting guard of honour, an irony Joe would have appreciated as his mourning bredren consumed several pounds of herb.

Pearl Harbour, Paul’s ex-wife, is there, talking to Joe Ely, the Texan rockabilly star who had often played with the Clash. She tells me how this trip has brought closure for her by bringing her back to what, she admits, was the happiest time in her life.

A moment later Tricia – Mrs Simonon – comes over as Pearl departs and proceeds to tell me how the absent Clash manager Bernie Rhodes had been contacted and invited to come to the funeral, but after the usual over-lengthy conversation it was impossible to discover what Bernie really felt or thought. ‘It seemed that he was more intent on getting on to the next agenda, which was that he desperately wanted to be invited to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction for the Clash next March. What he didn’t realize was that it was already decided that he would be invited.’

‘I always had a soft spot for Joe,’ Bernie later told me. ‘But I couldn’t go to the funeral because I didn’t like the people he was hanging around with.’

Joe and Mick had both wanted a re-formed Clash to play at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction. But the one refusenik? Paul Simonon, painter of Notting Hill. Trish admits that the last communication Paul had from Joe was on the morning that he died. Joe sent Paul a fax – he loved faxes, hated e-mails – saying, ‘You should try it – it could be fun.’ Paul, however, was adamant that the group shouldn’t re-form for the show.

Never too computer-literate, Joe wrote on a typewriter to the end. (Lucinda Mellor)

Next I find myself in a long conversation with Jim Jarmusch’s partner, Sara Driver, who commissioned Joe to write the music for When Pigs Fly, a film she made in 1993, starring Marianne Faithfull, that suffered only a limited release after business problems, and Bob Gruen’s wife Elizabeth. Jim is sitting next to us, deep in conversation with Cosmic Tim, a mutual friend of Joe and myself, from completely separate angles of entry. I had walked into the main upstairs bar as Cosmic Tim was standing on the stage with a microphone. It was the usual stuff that had gained him his sobriquet, and I groaned inwardly. ‘And this man Baba had been to the mountains of Tibet and lived there for twenty-five years, meditating.’ Other people in the packed crowd were groaning too (‘Get on with it.’). But then Cosmic Tim turned it around: ‘And one day when he returned to London, I was walking down Portobello Road with Baba when I see Joe walking towards us. I cross the road, and Baba and Joe look at each other. Suddenly, Baba calls out, “Woody!” (Joe’s nickname from The 101’ers.) And Joe looks up and shouts, “Baba!”’ According to Tim, Baba and Joe had known each other at art college. At length Sara, Elizabeth and myself discuss the state of depression in which Joe was regularly mired, and that most of the tributes to him that day are utterly omitting. Sara says how Jim used to refer to him as ‘Big Chief Thundercloud’. She also tells me how Joe had an enormous crisis when he was on tour in the States singing with the Pogues: he had fallen deeply in love with a girl and wanted to leave Gaby for her. Although he didn’t, in some ways it was the end of his relationship with the mother of his children. (This was a period when I remember Joe seemed even more in turmoil than usual, an air of great anger about him.)

The party is thinning out a little. It is 11 o’clock. I’ve got a slight headache. I leave and walk down to Ladbroke Grove tube station with Flea, Mick’s guitar roadie, and get home around midnight. I fall asleep on the sofa.

3

INDIAN SUMMER

1999

7 November 1999

In a shrine-like case in the seedily glitzy foyer of Las Vegas’s Hard Rock casino stands a guitar once owned by Elvis Presley. ‘What would Elvis think?’ groans Joe Strummer, here to play a show on his first solo tour in ten years. This distress seems a trifle exaggerated, as though Strummer is trying to force himself into the character of a 47-year-old bad boy rocker. ‘This case is only plexiglass: we could smash it open and have the guitar out of there before anyone noticed,’ he continues. Is this a confrontational posture he feels he should adopt in his job of Last Active Punk Star?

The frozen grins on the faces of those around him – his wife, an old friend from San Francisco, myself – suggest this is not what we want to hear: there seems a certain anxiety amongst us that, to prove his point, Strummer might carry out his threat, and that within seconds we will be shot to death by security guards. Thankfully, a fan approaches him for an autograph, the moment passes, and he makes his way backstage for his performance.

As a stage act, the reputation of the Clash was almost unsurpassed. Championed by many as the most exciting performing rock’n’roll group ever, there’s recently been the release of a live record, accompanied by a Don Letts’ documentary, Westway To The World. If ever there was a time to jump-start his solo career, this was it. Strummer seized the moment: he released an excellent album, Rock Art and the X-Ray Style; and took off on a seemingly endless tour, which is how I come to find him in Las Vegas.

Standing with him at the Hard Rock casino’s central bar at 4 in the morning after many post-show drinks, I tell him I’d had the impression that for years he had been going through an ongoing minor nervous breakdown. He balks at this, but initially will admit to having been locked into a state of long-term depression: ‘When people have nervous breakdowns, they really flip out. We shouldn’t treat them flippantly. It was more like depression, miserable-old-gitness.’

How long were you depressed for?

‘About five minutes. Until I had a spliff.’

A moment later he tries to wriggle out of even this admission: ‘I’m not claiming to have been depressed. All I’ll allow is that I didn’t have any confidence and I thought the whole show was over: you can wear your brain out – like on a knife-sharpening stone, run it until it shatters – and I just wanted to have some of it left.

Assisted by his now four-year-old marriage to Lucinda, his second wife, Strummer seems to have found a relative peace; Lucinda is credited by many around him with pulling him out of his malaise.

Christened John Mellor (‘without an “s” on the end, unfortunately: if there was, I’d have pulled more women,’ referring to the game-keeper’s surname in Lady Chatterley’s Lover), he was born in Ankara. His background would seem to show why Mick Jones once expressed amazement to me at how hard and tough a worker Strummer could be. For his father’s profession of career diplomat didn’t arise from any position of privilege, quite the opposite. ‘He was a self-made man, and we could never get on,’ says Strummer.

The musician’s grandparents had worked as management on the colonial railway network in India. ‘My father was a smart dude: he won a scholarship to a good school, then won another scholarship to university. When the war broke out, he joined the Indian army. My mother and father met in a casualty ward in India – she was working in the nursing battalion. After the war he joined the Civil Service at a lowly rank.’

Strummer’s earliest memory was of his brother, who was eighteen months older, ‘giving me a digestive biscuit in the pram’. He still is unable to assess what it was that led David to commit suicide. ‘Who knows? You can’t say, can you?’

Clearly this would have seemed a crucial, motivating catalyst in the life of the person who became Joe Strummer. How did it affect him? ‘I don’t know how it affects people. It’s a terrible thing for parents.’ He pauses for a very long time, until it becomes evident that this is all he is prepared to offer.

If it hadn’t been for punk, what on earth would have happened to Joe? He didn’t last too long at art school. After that, the only upward career move he seemed to have made was when he decided to stop being a busker’s money-collector and to become a busker himself – but even that worried him, he tells me, because he thought it might prove too difficult. It was this that led to him playing with The 101’ers, from which he was poached to become the Clash’s singer. ‘There is a part of Joe that is a real loser,’ says Jon Savage, author of England’s Dreaming, the definitive account of the punk era. ‘That’s what he was in his days as a squatter. And it’s that that comes across in his vocals, which was why people could identify with them so much.’

I tell Joe that Kosmo Vinyl, the unlikely named ‘creative director’ of the Clash, once said to me that if it hadn’t been for punk the singer would have ended up a tramp.

‘Yeah,’ he agrees, without a moment’s thought. ‘When I was a kid I knew that I was never going to make it in the thrusting executive world. I love picking stuff out of skips. A few bum records and I’ll be away with my shopping-trolley.’

I ask Joe Strummer what he learnt from his years in the wilderness. ‘Any pimple-encrusted kid can jump up and become king of the rock’n’roll world,’ he says, voicing something to which he has clearly given much thought. ‘But when you’re a young man like that you really do glow in the light of everyone’s attention. It becomes a sustaining part of your life – which is something that is rotten to the core: you cannot have that as a crutch, because one day you’re going to be over. So obviously I learnt that fame is an illusion and everything about it is just a joke.

‘I don’t give a damn any more. I’ve learnt not to take it seriously – that’s what I’ve learnt. And I’ve also learnt that because what you do is sort of interesting, doesn’t mean you’re any better than anyone else: after all, we’re not exactly devising new forms of protein. If they say, “Release this record because otherwise your career is finished,” and I don’t want them to, then I just won’t do it. I’m far more dangerous now, because I don’t care at all.’

4

STEPPING OUT OF BABYLON (ONE MORE TIME)

2003 (1952–1957)

Moving at a fast pace, Paul Simonon and I are cutting along a narrow rocky mud path that splits the wet grass on this high stretch of Scottish flatland. In a soaking spray of fine rain we have been climbing for twenty minutes. But the moment that we had stepped onto this level plateau the downpour had stopped: damp odours and mysterious scents are all that saturate us now. In the dagger-cold water of a lochan, we stash two cans of beer for our return journey. On the far bank a frog croaks irregularly.

Lusher and even more magical than its much larger, bleaker neighbour of Skye, this is the remote Inner Hebrides island of Raasay, up towards the northern tip of its twelve mile length. Thanks to an abiding impression of all-pervading strangeness, however, we feel we could as easily be on the other side of the moon as on the far north-western periphery of Europe. But you can’t avoid that feeling of being out on the edge. For miles around there are no other human beings, only a vast, amorphous silence, the soundtrack to the greyish-blue wild mountain scenery that juts around us; you can almost hear the clouds clashing on the highland rock and rustling on the purple heather.

As we push on each turn of a corner seems to brings a new microclimate, announced by a gasp of angular wind, like a message from a spirit: now the cloud cover is dashed away and a crisp blue sky sets in relief the Cuillin, Skye’s looming mountain peaks, a few miles across the Sound of Raasay; in this sudden sunlight the sea turns azure, the rough breakers crackling and glistening. After our steep, wet, upward hike, the flat stretch has come as a relief. We don’t know there is a far more arduous climb still to come: finally perched on a rock cairn at the top of that tough ascent, we can see both east and west coasts of the isle of Raasay, three miles apart.

Tough, gritty, awkward, dangerous, an astonishing terrain of primal, pure, mysterious beauty … It is little surprise that one of the descendants of Raasay – John Graham Mellor, known to those outside his blood family as Joe Strummer – has many of the same qualities as the island itself. Although he’d marked it in his diary for the summer of 2003, Joe himself never made it to Raasay; in the years immediately preceding he had been making a conscious effort to reacquaint himself with the Scottish roots on his mother’s side, an effort to redeem the previous thirty or so years when he admitted he had neglected this part of his past. ‘I’ve been a terrible Scotsman, but I’m going to be better,’ Joe said to his cousin Alasdair Gillies at the wedding of their cousin George in Bonar Bridge, three weeks before he died.

To the east, across the deepest inshore water in Britain, sits the mainland of Scotland and the mountain peaks of the Applecross peninsula, rising to over 2,000 feet and tipped by streaks of white quartzite. Opposite it, down towards the Raasay shoreline, lies our destination. Paul Simonon and I are here to find the earliest known home of Joe Strummer’s Scottish ancestors: the rocky, heathery, hilly path that at times we have to hang on to with our fingertips that we are following is the same one that Joe’s grandmother, Jane Mackenzie, would have taken to school. Donald Gilliejesus (‘servant of Jesus’), a stone mason, from near Mallaig on the Scottish mainland, arrived to repair Raasay House, destroyed by English Redcoats after ‘Bonnie’ Prince Charlie hid on the island in 1746 following the Jacobite Rebellion against the English crown. The house at Umachan was built in the early 1850s after the Gillies fled from the ‘clearances’ – the savage requisitioning of small-holdings by landowners – on the south of Raasay. Built by Angus Gillies, the great-grandson of Donald, it was inherited by his son Alastair Gillies. The second of Alastair’s ten children was Jane, born in 1883; Joe’s grandmother would walk barefoot to school along the same path Paul and I had clung to.

We head sharply down, across a lazy burn, past further cairns of stone. On our right there is what appears to be a natural amphitheatre, and a clearly evident ancient burial mound rising out of the greeny-brown terrain. Finally we are standing amidst waist-high bracken on a precipitous ledge, looking down on where we have been told Umachan should be. Between us we have distributed Paul’s canvases, paints and an easel, which have become a burden: we hide them in some undergrowth. Paul, something of a gourmet, tells me how in London he had popped into Bentley’s Oyster Bar in Swallow Street for a dozen oysters and a bottle of Chablis whilst buying the hiking shoes he’s wearing; it’s a long way from heating up flour-water poster-paste on a saw to eat, as Paul did in the early days of the Clash at Rehearsal Rehearsals. But a nourished belly and well-shod feet can only mark us out as the useless city slickers we are: we can find no trace of the home of Joe Strummer’s ancestor.

At a quarter to one, lunchtime on Friday 12 September 2003, my phone rings. It is Paul Simonon. ‘I think you’d better pack your bag, Chris. On Sunday I’m going up to Raasay off the Isle of Skye to do a painting of the house Joe’s grandmother used to live in. You should come with me.’

The Scottish Herald has commissioned Paul to paint a landscape of Rebel Wood, the forest on the Isle of Skye dedicated to Joe Strummer. Paul Simonon is the only member of the Clash to have carved out a non-musical career; returning to his original love of painting, and utilizing contacts he caught along the way as a member of such a prestigious British group, he has made a name and money as a figurative painter. Paul has agreed to paint the wood, but also will supply what he believes is a better idea: a picture of the ruined house in Umachan on Raasay. Iain Gillies, Joe’s cousin, had told us about these ruins.

As I am to discover, our expedition forms part of an experience that will bring some form of ending to the former Clash bass player for the thoroughly unexpected death of his former lead singer. During our time together, Paul emphasizes on several occasions that Joe was his brother, ‘my older brother’.

Every year film director Don Letts and his wife Grace throw a garden barbecue at their Queen’s Park home on August Bank Holiday Monday – a sort of refuge for the over-forties and under-tens from the Notting Hill carnival taking place a mile or so to the south. At the event in 2003, eighteen days before he made that Friday lunchtime call to me to come up to Scotland, I’d last seen Paul Simonon. The smaller 1976 Notting Hill carnival, when black youths and police had violently clashed beneath the elevated Westway in front of Joe Strummer and Paul Simonon, had led to the writing of ‘White Riot’, one of the most contentious songs in the Clash’s canon of work, a tune that at first – before people understood that its lyrics expressed the envy of white outsiders that black kids could so successfully rebel against the forces of law and order – led to suspicions that the group had a fascist political agenda. The 1976 event and the Westway became part of Clash mythology.

In the early days of the group Paul had always seemed shy. In 2001, however, when I had written the text for a picture-book about the Clash by Bob Gruen, the New York photographer, I had been surprised by a change that had overcome the group’s former bass player; as Bob Gruen and I went through hundreds of photographs with each of the group members, he was by far the most articulate. Mick was as warm as ever, but his comments were more jokey and less specific; and although Joe had insisted to Bob Gruen that I should write the text for his book, he surprised me by being the worst of the three interview subjects. Perhaps the photographs, which encapsulated almost the entire span of the career of the Clash, drew up too many memories; he ended up by saying he would write captions himself – and never did. Global A Go-Go, his second CD with the Mescaleros, was being readied for release and Joe was exhaustively – the only way he knew how to anything – promoting it; I could feel tension from Lucinda, on the couple of occasions when I rang up and spoke to her, trying to press Joe to come up with some text. A couple of months later, in the upstairs office that served as a dressing-room at the HMV Megastore on London’s Oxford Street, where Joe and the Mescaleros had just aired the new Global A Go-Go songs to a housefull crowd, he came up and apologized to me for not having come up with the goods.

‘It’s fine,’ I said, telling him I’d used quotes he’d given me over the years. ‘I know you had a lot on your plate, and we came up with something anyway.’

‘But you shouldn’t let down your mates,’ he shook his head at himself.

Anyway, in Don Letts’s back garden it dawned on me that – contrary to everything that you might have expected in 1977 – even before Joe’s passing Paul had become the spokesman and historian of the Clash. At Don’s home that August evening he was especially communicative and open and seemed to feel an urge to talk about the group.

Paul Gustave Simonon was born on 15 December 1955 to Gustave Antoine Simonon and Elaine Florence Braithwaite. Gustave, who preferred to call himself Anthony, was a 20-year-old soldier who later opened a bookshop; Elaine worked at Brixton Library. As happened to Mick Jones, Paul’s bohemian parents split up when he was eight; he and his brother were taken to Italy when about ten, where they lived for six months in Siena, and six months in Rome. There his mother took him to see all the latest Spaghetti Westerns – not just Sergio Leone, but all the Django films also. In London, Paul moved to live with his father in Notting Hill. His father, once an ardent Roman Catholic churchgoer, joined the Communist Party: ‘Suddenly we’re being told we’re not going to church any more. I’m being sent off to stuff leaflets for the Communist Party through people’s letterboxes in Ladbroke Grove. You can imagine what it was like: all these rough Irish or West Indians, hanging out on the steps, and I’m coming up to their letterboxes: “What’s that you’re putting through there?” “Oh, it’s just something about the Communist Party.” Then I figured out, if my dad was such a passionate Communist, how come he was sitting at home and sending me off to do this?

‘The Clash was a bit like the Communist Party,’ Paul free-associates, drawing up mention of manager Bernie Rhodes, ‘with Bernie as Stalin. We were his playthings. Bernie is a total original, it’s impossible to pin down exactly what he is – he’s absolutely unique.

‘What happened to Topper,’ he brings up the subject of the firing in 1982 of Topper Headon, ‘was that Mick, Joe and myself had an absolute belief in what we were setting out to do, and Topper came along later, when our attitudes were already set in stone. It’s like Topper said in Don’s documentary, Westway to the World, he thought he’d play with the Clash for a bit and use it as a stepping-stone for the rest of his career. He had a different attitude to it all.

‘But the Clash really was made up of Mick with his rock-star attitudes, Joe with his hippy beliefs, and me. And I was out there on my own: I wasn’t caught up in anything. I didn’t even really have any friends, only Nigel from Whirlwind.

‘I was angry at the time when it all came to a halt. It seemed such a waste. But now I’m glad we stopped at a point when we were about to be mega-huge and enormously rich. I’m glad we never re-formed. We proved we could come through it all. None of us were casualties, even though we came close to it. We came out the other side and survived, and people still love our music. Twelve year olds love the Clash now, so we must have done something right.’

Up on Raasay, Paul and I return to the site of Umachan with a guide, the ranger who looks after Rebel Wood. In fact, we had been right all along about the location of the settlement. The ranger shows us how we should have gone backwards along a trail to go forwards, a lesson in Highland zen. When we finally round a sheer mountain cliff and find Umachan a hundred yards in front of us, a lonely and haunting place, a tiny hamlet of eight homes, we rush through the ferns. On the scurrying high winds a golden eagle sails past us, its wings seeming to wave to us from the solitude in the sky, before it disappears behind a headland.

Among the ruins that have been reduced almost to rubble since the settlement was abandoned during the 1930s, Angus Gillies’s house is still standing, although its heather roof is long gone. A sturdy building, it is clearly the largest of those in the settlement, with an intact chimney gable and upper window. In the fireplace, Paul places a gift to the building, a copy of the Clash On Broadway boxed set, which sits like an icon amidst the rubble. There are two rooms on the ground floor – the smaller second room was used for keeping livestock warm in winter. In the late September sun the building’s pink sandstone is warm, vibrating with pulses of energy. The house is held together with lime mortar – beach sand – which allows moisture to be absorbed. Above it is a small, flat pasture. In front, towards the sea, a hundred yards below, is a walled-off yard, where kale and potatoes were grown to supplement the salt herring that was the staple diet of the islands. Out of the rear wall grows a red-berried rowan tree, which legendarily keeps away such bad spirits as witches. In this house was where Joe’s grandmother Jane lived.

Paul Simonon immediately sets up his easel and starts work, slipping off his jeans jacket and his shoes, which have been giving him blisters. As he stands painting in his white V-neck T-shirt, grey Levi 501s and bare feet Paul seems to be method-painting, swaying and rocking and feeling with the elements. He always paints standing, physically getting into it. ‘I act as a conduit: it’s not really me painting. I just stand there and something goes on, and it ends up on the canvas,’ he says.

In the sunlight the view across the sea of the mainland and the Applecross mountains is awesome. A lone yacht ploughs the water, edging the coastline, bounced back almost vertically by each crashing wave, a warning. Suddenly the weather changes. Thick dark-grey cloud gusts across the mountaintops. The view vanishes as we are engulfed in a haze of instant mist. It starts to piss down: thick, drenching rain direct from a Scottish heritage film. Struggling with the billowing wind, Paul even more assiduously straps his canvas to the easel.

The only spot in the roofless house to give any rain protection is in the shadow of the gable. When his canvas is running with rainwater, Paul brings it down to the house and slips it into the fireplace. Our guide produces a flask of malt whisky, mint tea, chocolate cake; we also consume a Joe Strummer Memorial Spliff. Our conversation veers to the practical: where did Joe’s ancestors keep the house whisky still, common to every Highland croft? Paul reveals that in his mid-teens he and his father had gone on holiday to Skye, hitch-hiking the seven hundred miles from London.

When the downpour eases, Paul picks up his canvas and steps back out again into the blustery fray. But the elements are simply too extreme for any more work. Again, he stashes his canvas in the fireplace, next to the Clash boxed set, turning the painted side away from the wind and rain. On the back, in red paint, he adds a warning note: Back later! Paul!

For travellers heading up the east coast of Scotland, Bonar Bridge, birthplace of Joe’s mother Anna Mackenzie, was the crossing-point over the Kyle of Sutherland – looking at the map it is the last significant indentation on the coastline. Nestling on the north bank of the estuary, the east of the area still hosts the ancient woodland planted by James IV to replace the oak forest that had been decimated in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries by the village’s iron foundry. Five miles from Bonar Bridge is Skibo Castle, the scene in 2000 of the wedding of Madonna to Guy Ritchie; at the handyman shop in Bonar Bridge the stepladders were all sold out, having been bought by paparazzi photographers trying to snap pictures over the wall of the castle. At Spinning Dale, on the edge of Bonar Bridge, the actor James Robertson Justice lived overlooking the water; when Joe’s Aunt Jennie worked for him there was a certain amount of local gossip after he was once alleged to have pinched her on the bottom. Nearby is the battlefield at which the Marquis of Montrose was defeated in 1650, forcing the later Charles II of England to accept the Scots’ demands for Presbyterianism if he was also to be accepted as King of Scotland; the ethos of Presbyterianism runs strongly in Bonar Bridge. A further battle affected Joe’s family history: after Culloden, which marked the defeat of the Jacobite army in 1746, four brothers from the Mackenzie clan hid in this remote corner from the savage reprisals.

When speaking to any of Joe’s Scottish relatives, I sometimes feel I am wandering in a fog of confusion: the same Christian names recur throughout the generations. But to compound my bewilderment the Gillies relatives I met weren’t always related to Joe’s grandmother, Jane Gillies. When Jane moved to Bonar Bridge at the start of the twentieth century, she married David Mackenzie – Jane did not pass on until Joe was fourteen. The Mackenzies form a large extended family. Anna Mackenzie, who was born 13 January 1915 and married Ron Mellor in 1949, was one of nine brothers and sisters. At the wake I spoke to Sheena Yeats, one of Joe’s eighteen cousins: the two women who gave eulogies at the funeral were Maeri, who works for the BBC, and Anna, a teacher, the sister of Iain, Rona and Alasdair Gillies, who were especially close to Joe.

It was amidst the wood-panelled surrounds of Carbisdale Castle that, three weeks before he died, Joe Strummer spent his last night at Bonar Bridge – on 30 November 2002, St Andrew’s Night, at the wedding banquet of cousin George to his partner Fiona. Folded in his pocket Joe had a copy of the family tree that his cousin Anna Gillies had drawn up. From time to time he would put down his ever-present can of cider and pull out the chart as another of his countless relatives hove into view; and he would show his willowy blonde wife Lucinda how this person fitted into his life.

Joe and Lucinda had rented a car at Inverness train station. Disdaining to take the new, faster motorway, he had driven over the highland route of the Struie, which he loved for its wildness and fabulous views of the Dornoch firth, past the inn on the road that is open all night and which serves soup and haggis until seven in the morning. ‘That’s the only way you can come,’ he would say. Arriving in Bonar Bridge that afternoon he and Luce had taken a room at the Dunrobin pub on the high street to rest up: ‘He seemed so healthy, so debonair, relaxed, healthy and fit, and young,’ said Alasdair Gillies, who was five years younger. ‘I remember saying, “You look younger than me.”’ ‘He was in good shape,’ confirmed his aunt Jessie, his mother’s younger sister, and the only surviving female amongst her siblings. Aunt Jenny, who had been married to the late David Mackenzie, one of Joe’s mother’s three younger brothers, thought Joe looked ‘terribly tired’, though she added ‘but they hadn’t eaten and were starving’.

At the wedding party at Carbisdale Castle Joe was fascinated by the traditional Scottish melodies of the Carach Showband, and spent time talking with the piper. At Carbisdale Castle Joe was distressed to find that an LP sleeve of the Bonar Bridge Pipe Band, on which the cover photograph showed the musicians posing outside the castle, contained no record inside it: writing down its details he vowed to trace the LP and get hold of a copy. ‘Unfortunately he didn’t have time,’ said Alasdair.

Fiona, George’s bride, and two of her friends sang unaccompanied versions of Gaelic songs at the party. ‘I looked over at Joe and he was in tears,’ recalled Alasdair. ‘A few minutes later he was saying, “Wouldn’t it be great if you could get twelve of those tunes and put them on a CD.” I was very moved. He said, “You don’t get songs like that now: they last forever.”’ Lucinda had mentioned that in New York on Tartan Day the previous April Joe had insisted on marching all the way up Fifth Avenue, determined to see the pipe bands, and again he had been so moved that tears had run down his face. To the amusement of some of his relatives, Joe and Luce danced their own, not very accurate versions of the Highland ‘Skip the Reel’.

The following day, Joe visited a property called West Airdens, a croft with a startling view that belonged to his aunt Jessie and her shepherd husband Ken, an extraordinary house that seemed magical to Joe. When he learnt that Jessie and her husband Ken had decided it was time to move down to Bonar Bridge, Joe made an instant decision: ‘Let’s buy it now, all of us, all the cousins.’ ‘“For each according to his means,” he said,’ Alasdair remembered, ‘quoting Marx. I said, “What would Engels say?” And he laughed. “What would Jessie say?” I wondered. “She’ll be up for it,” said Joe. Then it was 5 p.m., and he had to go the station.’

Joe was already a day late. He had to be in Rockfield studio in South Wales, where he was to record his next album with The Mescaleros. But he had learnt something that was strongly drawing him back to Bonar Bridge: that day, 1 December, was the birthday of Uncle John Mackenzie, the brother of Anna, his mother, and the man Joe always called ‘the original punk rocker’. As he grew older Joe Strummer felt close to all his Bonar Bridge relatives, but Uncle John held a special meaning for him and touched his heart. Johnny Mellor was even christened after Uncle John. ‘In a perfect world, I wouldn’t go home,’ he stated. ‘Uncle John told me he’s 77 today. In a perfect world I’d go to the Dunrobin for the evening. Maybe I could go back tomorrow.’ ‘He knew he had to go,’ said Alasdair, ‘but didn’t want to. But at the last minute, he said, “I’d better go. In a perfect world, I’d stay. But this is not a perfect world.”’ (When we call round, Uncle John pours us each ‘a wee dram’ of the Irish whiskey that Joe had despatched up to him as a birthday gift as soon as he arrived at Rockfield.)

Minutes into Joe and Luce’s hour-long drive to Inverness station, he phoned Alasdair, fired up with enthusiasm, reminding him they had to buy the house. Moments later he called again, repeating this insistence, and – filled with the emotion of the weekend – reminding his cousin he would waste no time in tracking down the LP by the Bonar Bridge Pipe Band. ‘The Bonar Bridge magnetism holds you: you don’t want to go back to the city. On his last visit Joe exhibited all the symptoms of that condition. Then he phoned me at the station, saying he had made it, and we’d sort out the house. “Love to all,” he said. And that was the last time I saw him. The next thing I knew I got a call from Amanda Temple, the wife of Julien Temple, the film director, who lived near him in Somerset, three weeks later.

‘But those two days we were with him, I felt he’d reached a new level, reconciled both his father’s side and his mother’s Highland stuff. He was being restored to his rightful place in the bosom of the family, onwards and upwards. And it was very hard to bear, when he died.’

Sitting in his favourite armchair by the window of the living-room in the sturdy family croft of Carnmhor in Bonar Bridge, Uncle John speaks with the same lilting Highlands accent that Joe’s mother Anna never lost. ‘Johnny first came here when he was under a year. They were just back from Turkey, and came up by train.’ At one moment on the first of these fortnight-long visits to Bonar Bridge, the toddler Johnny Mellor was found standing at the top of Carnmhor’s steep stairs, shouting in Turkish for someone to carry him down them as there was no banister rail. Upstairs at Carnmhor, the bedroom in which John and his brother David stayed had big brass bedsteads, hard mattresses and bolsters. The two boys were always collectively referred to by the family as David-and-Johnny, like fish’n’chips, or Morecambe-and-Wise, or – perhaps more appositely – like rock’n’roll.

With his young nephew, uncle John Mackenzie shared certain characteristics which only increased as Johnny matured into the figure of Joe Strummer. In his almost Australian aboriginal tendency to go ‘walkabout’, Uncle John predicted behaviour that many people connected with Joe were obliged to accept: the most public example of this was his famous vanishing act in 1982 before a Clash US tour. Uncle John had that same ability to disappear. In the early 1940s, ‘Bonnie John’ – as he was known in his youth – vanished for several weeks. Assuming he was dead, Jane Mackenzie, his mother, went to bed for a fortnight. Eventually he was discovered in Inverness.

After that first visit to Bonar Bridge it was seven years (‘a long while,’ said John, with sadness in his voice) before the Mellor family returned to Anna’s home. On each of the annual visits his family paid to Bonar Bridge between 1960 and 1963, Johnny Mellor liked nothing better than running after Uncle John and his tractor. ‘David was about nine, Johnny was about seven,’ John remembered of that next visit. ‘Johnny was a very cheery, happy boy. He would just wander around the place. He was very fond of being outside. He was a young boy full of life. He did a painting of cowboys and Indians, which we hung up on the wall.’ That painting, a precursor of a theme around which much of Joe’s later drawing and painting was based, hung in the hallway at Carnmhor for many years.

David, Johnny’s older brother, was ‘much quieter’, remembered Uncle John. ‘Johnny used to wander around with me when I was working. I had cattle and sheep: he was always watching them with me. He’d help with what he called the “hoos coo”, milking it. I never saw him play a guitar. I heard his music often. I saw them on the TV as well. They were oot of my mind altogether – the young people liked them.’ But he remembered a surprise phone-call from Joe in Japan in 1982: ‘He was just blathering away. “I’m looking for a job, teaching rock’n’roll,” he said to me, joking of course.

‘He was here for a long while on the Sunday with his wife,’ said Uncle John. ‘He was very reluctant leaving. If anyone had said two words to him he’d have stayed. He said, “I’m bringing my two daughters up in the summertime.” But it never came to pass.’

The visit in the summer of 1960 marked the first time that Alasdair’s brother Iain had met Johnny. From their home in Glasgow, the Gillies family – with Joe’s four cousins Iain, Anna, Alasdair and Rona – had also gone up to Bonar Bridge, as they did every year without fail, and both families were crammed into Carnmhor. With Johnny, Iain would play in the barn, swinging on the rope and rolling on the piles of corn. Together they caught newts from the stream in jam jars, releasing those still left alive. In a pillbox concrete bunker on the farm they discovered left-over boot polish. ‘We probably showed off too much that we thought we were from somewhere else. Johnny seemed to me to be very lively, funny and inventive. David was quiet. I recall Johnny being the organizer and the one who dictated the plans for our games and general mischief-making. He was a bit pugnacious and always insouciant. On the first day we met at the croft, Johnny started a pebble-throwing fight. It was Johnny and David versus me. I was two years younger than Johnny and three younger than David, so I was a bit concerned at first. As the stone-throwing got more vicious I could tell that David’s heart wasn’t really in it, and it tailed off into a draw. Johnny said, “We won that battle, didn’t we, Dave?” In retrospect, I think, to gee David up, give him succour.’ The lines of battle, claimed Anna, were drawn between the Scots and the English. ‘Because I was a girl I wasn’t even recruited for that,’ she complained. ‘In the living room at the farm,’ said Iain, ‘Johnny recited some scurrilous rhyme that he knew, the subject matter of which concerned coating the crack of a female bottom with jam. He knew all the words and to my six-year-old mind it was very funny, slightly shocking, but exhilarating.’ Clearly by that age Johnny was indicating the mischievous humour within him that would remain all his life. But he was also revealing a slight tendency to bully, an aspect of himself that also never entirely went away. ‘On another occasion at Carnmhor,’ Iain recalled, ‘he convinced me that it would be a great idea to completely strip my sister Anna, who was about five, of all her clothes and hide them upstairs in our Uncle John’s cupboard – nobody would ever find them in there, he said. Anna came downstairs and made her grand naked entrance.’

‘I can remember going down the three steps,’ said Anna, ‘where Aunt Anna was drying clothes, and there was a tremendous hullabaloo. They couldn’t find my clothes, which were hidden in Uncle John’s room.’

Each Sunday morning the adults would take themselves and any girls about the house to endure the tedious sermonizing of Mr McDonald at church. On one of these occasions Johnny and Iain, who had quickly become partners-in-crime, decided to provide an entertaining homecoming greeting for Anna. Taking her favourite doll, they suspended it upside down with pegs in the lobby. She was most distressed. ‘It was all blamed on Johnny,’ she said. ‘Because I was a girl they wouldn’t let me play.’ ‘I was immediately aware,’ added Iain, ‘that for all my six years of worldly experience, cousin Johnny was unlike anyone I had met so far.’

It was on one of those trips between 1960 and 1963 that Johnny’s family broke their journey up from London by staying for a couple of days with the Gillies family in Glasgow. David was in a bad mood for the duration of their sojourn because he had to sleep in the same bedroom as Anna. ‘He stood there sawing this piece of string up and down on the door handle, which even at my young age seemed pointless,’ she said. In Bonar Bridge itself, ‘Johnny decided,’ said Iain, ‘that since we were going on a two-mile walk to visit our relatives and the road would take us past a Gypsy encampment, that we would need to be fully armed to repel any attack. Johnny told me to explain the seriousness of the situation to my parents; he would do the same with his, and therefore our parents were bound to provide us with the funds for weapons. There was much adult laughter but they complied, and we bought shiny, one shilling pen-knives at the local newsagent’s. I remember Johnny and I debating whose knife had the most style and panache.’ Johnny and Iain managed to arrive without having to draw their pen-knives.

Anna Mackenzie was born on 13 January 1916, the second child of David and Jane Mackenzie and their first daughter. After attending local schools, she opted for a career in nursing, one of the few choices open for women from families with limited means and one that accorded well with the Presbyterian need to fulfil one’s societal duty. Anna’s older brother, David, had died of peritonitis as a young man. Anna herself was imbued with characteristic Mackenzie qualities: ‘self-reliant, uncomplaining, serene, stoic, ironic, shrewd, determined, engaging, solicitous, and quietly aware of the vicissitudes of life,’ thought Ian Gillies. She was also beautiful.

Moving to Aberdeen, 120 miles south of Bonar Bridge, Anna received her training at Forester Hill hospital. Fifteen years older than her sister Jessie, she was nursing before Jessie had even gone to school. After Aberdeen, Anna went to Stob Hill hospital on the north-east edge of Glasgow, moving into accommodation nearby in Crowhill Road; Anna was promoted to Sister, a position with much responsibility for one still in her early twenties, a clear indication of her abilities.

At Stob Hill she met Adam Girvan, a male nurse from Ayrshire. Twice when she travelled home to Bonar Bridge he was with her. In 1940 they were married.

But as World War II had begun the previous year, Anna Girvan, as she now was, joined the Queen Alexandra Nursing Service; meanwhile, her husband, went into the Royal Army Medical Corps. Although they had expected to do service together, Adam Girvan was sent to Egypt, whilst Anna went to India: it was three years before she saw her husband again.

Stationed at a large army hospital in Lucknow in northern India, this woman from the north of Scotland suffered from the climate. ‘The heat disagreed with her severely,’ said her sister Jessie. ‘She had prickly heat.’ Struck down with appendicitis, which must have triggered memories of the death of her older brother David, she was successfully operated on. Then she was sent to recuperate in the cooler weather higher up in the hills. ‘In the hospital where she stayed she had a great view of the Himalayas.’

There, while lancing a boil for him, she met a lieutenant in an artillery regiment in the Indian army called Ronald Mellor who had been called up into the armed forces in 1942.

Ronald Mellor had been born in Lucknow on 8 December 1916. He was the youngest of four children; Phyllis, Fred and Ouina came before him. His father was Frederick Adolph Mellor, who had married Muriel St Editha Johannes; half-Armenian and half-English, she was a governess to a wealthy Indian family. There was a large population of Armenians in Lucknow. Frederick Adolph Mellor was one of five sons of Frederick William Mellor and Eugenie Daniels, a German Jewess, who had married during the Boer War when his father lived in East Budleigh in Devon. Shortly afterwards they moved to India. The family home in Lucknow was named Jahangirabad Mansion. Later Frederick William Mellor returned to East Budleigh, where he bought a row of cottages that he rented out. His son Bernhardt came to East Budleigh and married the local postmistress. Phyllis, his daughter still lives there.

Muriel Johannes was one of three daughters of Agnes Eleanor Greenway and a Mr Johannes: her two sisters were Dorothy and Marian. After the early death of her Armenian father, Muriel’s mother Agnes remarried, to a Mr Spiers, with whom she had two further daughters, Mary and Maggie.

Frederick Adolph Mellor, Joe’s grandfather, worked in a senior administrative position for the Indian railway, but died of pleurisy in 1919, when Ronald was still a toddler. Following his death his widow married George Chalk, who became Ronald Mellor’s stepfather, but Chalk disappeared to South Africa. Joe’s grandmother Muriel Mellor was not without her problems. A social whirl was part of the colonial norm in India; excessive drinking was an accepted part of that world, and she was an alcoholic, taking out her drunken rages on her children. Gerry King, a former teacher who lives in Brighton, is the daughter of Phyllis, the eldest of Ron’s siblings: ‘I was told that the mother was alcoholic, and used to beat them up. So my mother protected all four of them, and they used to hide from her.’ In 1927 Muriel Mellor died, largely because of her addiction to drink. (In 1999 Joe Strummer told me that both his grandparents on his father’s side had been killed in an Indian railway accident. When I learned what the truth was, I suspected him of some Bob Dylan or Jim Morrison-like obfuscation of his past. But no, said Gaby, the mother of his two children: ‘Joe really thought that was the truth. All the information that came down to him about his father’s life in India was so befuddled, and he was always trying to find out what the real history was.’) Joe’s father Ronald Mellor and his brother and two sisters were then brought up by Agnes Spiers, although Mary, her daughter, took a keen interest in helping to raise the children. ‘Ronald was the favourite with his half-Aunt Mary,’ said Jonathan Macfarland, another cousin on Joe’s father’s side. Ronald and Fred were educated at La Martinière College in Dilkusha Road in Lucknow, a revered Indian school. After La Martinière Ronald Mellor moved on to the University of Lucknow.

After Mrs Adam Girvan met Lieutenant Ronald Mellor, they fell in love. Ron, who by the end of the war had been promoted to Major, was great company, very funny, sensitive, intelligent and articulate; his Indian upbringing and racial mix made him seem unusual to the woman with a pure Highlands bloodline; and when she was with him her natural beauty was only emphasized by the glow of love that surrounded her like a halo. ‘Ron was very exotic, and I can see why Anna was captivated,’ thought Rona, Alasdair Gillies’s twin sister. Anna’s heart was touched by the subtly lingering sense of sadness that Ron had carried with him ever since the death of his difficult mother; some felt that the fact that he couldn’t even remember his father accounted for his faintly other-worldly air of permanent bewilderment.

They decided to make their lives together. But there was a problem: Anna was still married. Divorce in those days was very rare, and not in the vocabulary of the Bonar Bridge Mackenzies. All the same, Anna communicated her intentions to Adam Girvan. When she returned to the United Kingdom at the end of the war, they divorced: Anna discovered that as soon as Adam had learned of her relationship with Ron Mellor, he had cleaned out their joint bank account.

‘I remember my father wasn’t very chuffed about the divorce,’ said her sister Jessie. ‘But Mum didn’t say much.’ But would you have expected her to? As Jessie pointed out, ‘You didn’t even talk about pregnancy. Granny was very, very strict.’ Anna went up to Bonar Bridge and made peace with her parents. In that Highland way of keeping intimate matters close to your chest, the divorce was kept secret from everyone, including her children. ‘My mum told me Anna had been married before, but she never told my dad,’ Rona described a typical piece of Mackenzie behaviour. ‘I wasn’t surprised about it – things happen,’ said Uncle John, customarily phlegmatic. Joe didn’t learn about it until he was in the Clash. ‘I’ve just found out that my mum was married before,’ he said, tickled. ‘She seems to have been a bit of a goer.’

Ron Mellor made his way to London, and took a job in the Foreign Office as a Clerical Officer; considered highly prestigious, the FO only admitted candidates considered high fliers; they were subjected to a supposedly rigorous security check. Soon Ron and Anna were married: in a picture of Ron and Anna on their wedding day on 22 October 1949, her new husband’s caddish Clark Gablethin moustache and double-breasted suit give him the appearance of an archetypal Terry Thomas marriage-wrecker – which, in a way, he was. The newlyweds moved into a top-floor flat, up four flights of stairs, at 22 Sussex Gardens in the seedy area of Paddington. They lived there for two years. Meanwhile, Anna took a post as sister at one of the largest hospitals in London, St George’s by Hyde Park Corner.