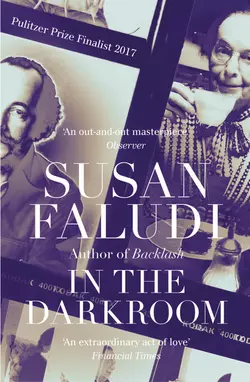

In the Darkroom

Susan Faludi

A NEW YORK TIMES BOOK OF THE YEARWINNER OF THE KIRKUS PRIZESHORTLISTED FOR THE PULITZER PRIZE 2017From the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and best-selling author of ‘Backlash’, an astonishing confrontation with the enigma of her father and the larger riddle of identity.In 2004 feminist writer Susan Faludi set out to investigate someone she scarcely knew: her estranged father. Steven Faludi had lived many roles: suburban dad, Alpine mountaineer, swashbuckling adventurer in the Amazon, Jewish fugitive in Holocaust Budapest. Living in Hungary after sex reassignment surgery and identifying as ‘a complete woman now,’ how was this new parent connected to the silent and ultimately violent father who had built his career on the alteration of images?Faludi’s struggle to come to grips with her father's metamorphosis takes her across borders – historical, political, religious, sexual – and brings her face to face with the question of the age: is identity something you "choose" or is it the very thing you cannot escape?

Copyright (#ulink_95a7fdcc-0e94-5a69-b46f-069b5d93ad4c)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2016

This eBook edition published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Copyright © 2016, 2017 by Susan Faludi

Susan Faludi asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This is a work of nonfiction. The names and identifying characteristics of three individuals have been changed to protect their privacy.

‘I Am Easily Assimilated’ from Candide by Leonard Bernstein. Lyrics by Leonard Bernstein. Copyright © 1994 by Amberson Holdings LLC. Copyright renewed, Leonard Bernstein Music Publishing Company, publisher. International copyright secured. Reprinted by permission.

Excerpt from ‘Red Riding Hood’ from Transformations by Anne Sexton. Copyright © 1971 by Anne Sexton, renewed 1999 by Linda G. Sexton. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Excerpt from ‘Optimistic Voices (You’re Out of the Woods)’ from The Wizard of Oz. Lyrics by E. Y. Harburg. Music by Harold Arlen and Herbert Strothart. Copyright © 1938 by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc., renewed 1939 by EMI Feist Catalog Inc. Rights throughout the world controlled by EMI Feist Catalog Inc. (publishing) and Alfred Music (print). Used by permission of Alfred Music. All rights reserved.

All photographs courtesy of the author, except for the following: here (#litres_trial_promo), Einar Wegener/Lili Elbe by Wellcome Library, London; here (#litres_trial_promo), Christine Jorgensen by Art Edger/NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images; here (#litres_trial_promo), Melanie’s Cocoon by Mel Myers; here (#litres_trial_promo), Class of ’45 photograph courtesy of Otto and Margaret Szekely; here (#litres_trial_promo), Parasite Press photograph courtesy of Judit Mészáros, the original in Budapest Collection of Szabó Ervin Central Library; here (#litres_trial_promo), Ford convertible by Marilyn Faludi; here (#litres_trial_promo), Magyar Garda rally by European Pressphoto Agency/Tamas Kovacs

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008194475

Ebook Edition © July 2017 ISBN: 9780008193515

Version: 2017-06-24

Additional Praise for In the Darkroom: (#ulink_3f1d42cc-a2cd-56f1-9a28-2aed899dcbeb)

A SUNDAY TIMES BOOK OF THE YEAR 2016

‘Faludi’s remarkable, moving and courageous book is extremely fair-minded’

Guardian

‘In the Darkroom reads like a mystery thriller yet packs the emotional punch of a carefully crafted memoir. Susan Faludi’s investigation into her father’s life reveals, with humour and poignancy, the central paradox of being someone’s child. However close, our parents will always be, perhaps by nature of the role, fundamentally enigmatic to us’

AMANDA FOREMAN

‘Faludi weaves together these strands of her father’s identity – Jewishness, nationality, gender – with energy, wit and nuance … Faludi has paid her late father a fine tribute by bringing her to life in such a compelling, truthful story’

New Statesman

‘[A] mighty new book … a searching investigation of identity barely disguised as a sometimes funny and sometimes very painful family saga … reticent, elegant and extremely clever’

Observer

‘A fascinating chronicle of a decade trying to understand a parent who had always been inscrutable’

Economist

‘Compelling’

Sunday Times

Well-written … touching … compelling’

The Times

‘An astonishing, unique book that should be essential reading for anyone wanting to explore transsexuality’s place in contemporary culture’

Irish Independent

‘In the Darkroom is a unique, deeply affecting and beautifully written book, full of warmth, intelligence and humour’

Saturday Paper

Dedication (#ulink_5094d0db-12e4-5d1c-b37b-97840f4bd52c)

For the Grünbergers of Spišské Podhradie and the Friedmans of Košice, and their children and their children’s children, the family I found, and who found me

Epigraph (#ulink_c9593004-edbe-5807-8c7c-5beb78203e40)

He thought about how he had been despised and scorned, and he heard everybody saying now that he was the most beautiful of all the beautiful birds. And the lilacs bowed their branches toward him, right down into the water. The sun shone so warm and so bright. Then he ruffled his feathers, raised his slender neck, and rejoiced from the depths of his heart. “I never dreamed of such happiness when I was an ugly duckling!”

Hans Christian Andersen, “The Ugly Duckling”

The identifying of ourselves with the visual image of ourselves has become an instinct; the habit is already old. The picture of me, the me that is seen, is me.

D. H. Lawrence, “Art and Morality”

Long ago

there was a strange deception:

a wolf dressed in frills,

a kind of transvestite.

But I get ahead of my story.

Anne Sexton, “Red Riding Hood”

Contents

Cover (#ua96a829b-3da2-5096-ae13-57165e4a76f7)

Title Page (#ub2b6a544-3da7-54a3-a8c3-9d513102eb52)

Copyright (#uaf9d0055-5675-5e0f-a1ff-1f544a225857)

Additional Praise for In the Darkroom (#ufd344a2f-3ecc-5004-bc06-c2d07054b0ea)

Dedication (#ue92d6d3b-de28-52b5-a1a5-cd6c988528ea)

Epigraph (#u48a5b879-8ff3-5452-b867-6734b0e11d5f)

Preface: In Pursuit (#udd98535d-fad9-5f88-9f21-7487fc858fd3)

PART I (#u5b40660e-ff3d-526b-9439-08ed8f684aab)

1. Returns and Departures (#uc8cf88bd-4e02-5ed6-a82a-787bc8d73a4d)

2. Rear Window (#u38f2b4a4-6c6e-5bc0-8c98-4a524508fc82)

3. The Original from the Copy (#u3f2e5294-b8f5-5c45-92ff-4c2fba99b792)

4. Home Insecurity (#u96c1965b-7ca1-532f-8b00-381380126a0c)

5. The Person You Were Meant to Be (#uab8909f0-77e6-56a6-8c6a-212d4a146cb7)

6. It’s Not Me Anymore (#u47c5638a-1df6-5cdd-a8c0-ca001736c135)

7. His Body into Pieces. Hers. (#ucdae4e29-e72e-5ef9-a23b-9c7cd1a96aa3)

8. On the Altar of the Homeland (#ud12c33fd-ce60-5416-929a-3108eb60c1e8)

9. Ráday 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

PART II (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Something More and Something Other (#litres_trial_promo)

11. A Lady Is a Lady Whatever the Case May Be (#litres_trial_promo)

12. The Mind Is a Black Box (#litres_trial_promo)

13. Learn to Forget (#litres_trial_promo)

14. Some Kind of Psychic Disturbance (#litres_trial_promo)

15. The Grand Hotel Royal (#litres_trial_promo)

16. Smitten in the Hinder Parts (#litres_trial_promo)

17. The Subtle Poison of Adjustment (#litres_trial_promo)

18. You’re Out of the Woods (#litres_trial_promo)

19. The Transformation of the Patient Is Without a Doubt (#litres_trial_promo)

PART III (#litres_trial_promo)

20. Pity, O God, the Hungarian (#litres_trial_promo)

21. All the Female Steps (#litres_trial_promo)

22. Paid Up (#litres_trial_promo)

23. Getting Away with It (#litres_trial_promo)

24. The Pregnancy of the World (#litres_trial_promo)

25. Escape (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Susan Faludi (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PREFACE (#ulink_0a7a0f1a-d3db-5f14-b081-ae4b05116079)

In Pursuit (#ulink_0a7a0f1a-d3db-5f14-b081-ae4b05116079)

In the summer of 2004 I set out to investigate someone I scarcely knew, my father. The project began with a grievance, the grievance of a daughter whose parent had absconded from her life. I was in pursuit of a scofflaw, an artful dodger who had skipped out on so many things—obligation, affection, culpability, contrition. I was preparing an indictment, amassing discovery for a trial. But somewhere along the line, the prosecutor became a witness.

What I was witness to would remain elusive. In the course of a lifetime, my father had pulled off so many reinventions, laid claim to so many identities. “I’m a Hungaaaarian,” my father boasted, in the accent that survived all the shape shifts. “I know how to faaaake things.” If only it were that simple.

“Write my story,” my father asked me in 2004—or rather, dared me. The intent of the invitation was murky. “It could be like Hans Christian Andersen,” my father said to me once, later, of our biographical undertaking. “When Andersen wrote a fairy tale, everything he put in it was real, but he surrounded it with fantasy.” Not my style. Nevertheless, I took up the dare with a vengeance, and with my own purposes in mind.

Despite the overture, my father remained a refractory subject. Most of the time our collaboration resembled a game of cat and mouse, a game the mouse generally won. My father, like that other Hungarian, Houdini, was a master of the breakout. For my part, I kept up the chase. I had cast myself as a posse of one, tracking my father’s many selves to their secret recesses. I was intent on writing a book about my father. It wasn’t until the summer of 2015, after I’d worked my way through many drafts and submitted the manuscript, and after my father had died, that I realized how much I’d also been writing it for my father, who, in my mind at least, had become my primary, imagined, and intended reader—with all the generosity and hostility that implies. It wasn’t an uncomplicated gift.

“There are things in here that will be hard for you to take,” I warned in the fall of 2014, when I called to announce that I had a completed draft. I braced myself for the response. My father, who had made a career in commercial photography out of altering images and devoted a lifetime to self-alteration, would hate, I assumed, being depicted warts and all.

“Waaall,” I heard after a silence. “I’m glad. You know more about my life than I do.” For once my father seemed pleased to be captured, if only on the page.

PART I (#ulink_6e57286c-61aa-5074-b87a-235a774ff688)

1 (#ulink_e2e6a7a4-1f2a-5f54-8e30-0eebb0929c8c)

Returns and Departures (#ulink_e2e6a7a4-1f2a-5f54-8e30-0eebb0929c8c)

One afternoon I was working in my study at home in Portland, Oregon, boxing up notes from a previous writing endeavor, a book about masculinity. On the wall in front of me hung a framed black-and-white photograph I’d recently purchased, of an ex-GI named Malcolm Hartwell. The photo had been part of an exhibit on the theme “What Is It to Be a Man?” The subjects were invited to compose visual answers and write an accompanying statement. Hartwell, a burly man in construction boots and sweat pants, had stretched out in front of his Dodge Aspen in a cheesecake pose, a gloved hand on a bulky hip, his legs crossed, one ankle over the other. His handwritten caption, appended with charming misspellings intact, read, “Men can’t get in touch with there feminity.” I took a break from the boxes to check my e-mail, and found a new message:

To: Susan C. Faludi

Date: 7/7/2004

Subject: Changes.

The e-mail was from my father.

“Dear Susan,” it began, “I’ve got some interesting news for you. I have decided that I have had enough of impersonating a macho aggressive man that I have never been inside.”

The announcement wasn’t entirely a surprise; I wasn’t the only person my father had contacted with news of a rebirth. Another family member, who hadn’t seen my father in years, had recently gotten a call filled with ramblings about a hospital stay, a visit to Thailand. The call was preceded by an out-of-the-blue e-mail with an attachment, a photograph of my father framed in the fork of a tree, wearing a pale blue short-sleeved shirt that looked more like a blouse. It had a discreet flounce at the neckline. The photo was captioned “Stefánie.” My father’s follow-up phone message was succinct: “Stefánie is real now.”

The e-mail notifying me was similarly terse. One thing hadn’t changed: my photographer father still preferred the image to the written word. Attached to the message was a series of snapshots.

In the first, my father is standing in a hospital lobby in a sheer sleeveless blouse and red skirt, beside (as her annotation put it) “the other post-op girls,” two patients who were also making what she called “The Change.” A uniformed Thai nurse holds my father’s elbow. The caption read, “I look tired after the surgery.” The other shots were taken before the “op.” In one, my father is perched amid a copse of trees, modeling a henna wig with bangs and that same pale blue blouse with the ruffled neckline. The caption read, “Stefánie in Vienna garden.” It is the garden of the imperial villa of an Austro-Hungarian empress. My father was long a fan of Mitteleuropean royals, in particular Empress Elisabeth—or “Sisi”—Emperor Franz Josef’s wife, who was known as the “guardian angel of Hungary.” In a third image, my father wears a platinum blond wig—shoulder length with a ’50s flip—a white ruffled blouse, another red skirt with a pattern of white lilies, and white heeled sandals that display polished toenails. In the final shot, titled “On hike in Austria,” my father stands before her VW camper in mountaineering boots, denim skirt, and a pageboy wig, a polka-dotted scarf arranged at the neck. The pose: a hand on a jutted hip, panty-hosed legs crossed, one ankle before the other. I looked up at the photo on my wall. “Men can’t get in touch with there feminity.”

The e-mail was signed, “Love from your parent, Stefánie.” It was the first communication I’d received from my “parent” in years.

My father and I had barely spoken in a quarter century. As a child I had resented and, later, feared him, and when I was a teenager he had left the family—or rather been forced to leave, by my mother and by the police, after a season of escalating violence. Despite our long alienation, I thought I understood enough of my father’s character to have had some inkling of an inclination this profound. I had none.

As a child, when we had lived together in a “Colonial” tract house in the suburban town of Yorktown Heights, an hour’s drive north of Manhattan, I’d always known my father to assert the male prerogative. He had seemed invested—insistently, inflexibly, and, in the last year of our family life, bloodily—in being the household despot. We ate what he wanted to eat, traveled where he wanted to go, wore what he wanted us to wear. Domestic decisions, large and small, had first to meet his approval. One evening, when my mother proposed taking a part-time job at the local newspaper, he’d made his phallocratic views especially clear: he’d swept the dinner dishes to the floor. “No!” he shouted, slamming his fists on the table. “No job!” For as far back as I could remember, he had presided as imperious patriarch, overbearing and autocratic, even as he remained a cipher, cryptic to everyone around him.

I also knew him as the rugged outdoorsman, despite his slender build: mountaineer, rock climber, ice climber, sailor, horseback rider, long-distance cyclist. With the costumes to match: Alpenstock, Bavarian hiking knickers, Alpine balaclava, climber’s harness, yachter’s cap, English riding chaps. In so many of these pursuits, I was his accompanist, an increasingly begrudging one as I approached adolescence—second mate to his captain on the Klepper sailboat he built from a kit, belaying partner on his weekend assays of the Shawangunk cliffs, second cyclist on his cross-the-Alps biking tours, tent-pitching assistant on his Adirondack bivouacs.

All of which required vast numbers of hours of training, traveling, sharing close quarters. Yet my memory of these ventures is nearly a blank. What did we talk about on the long winter evenings, once the tent was raised, the firewood collected, the tinned provisions pried open with the Swiss Army knife my father always carried in his pocket? Was I suppressing all those father-daughter tête-à-têtes, or did they just not happen? Year after year, from Lake Mohonk to Lake Lugano, from the Appalachians to Zermatt, we tacked and backpacked, rappelled and pedaled. Yet in all that time I can’t say he ever showed himself to me. He seemed to be permanently undercover, behind a wall of his own construction, watching from behind that one-way mirror in his head. It was not, at least to a teenager craving privacy, a friendly surveillance. I sometimes regarded him as a spy, intent on blending into our domestic circle, prepared to do whatever it took to evade detection. For all of his aggressive domination, he remained somehow invisible. “It’s like he never lived here,” my mother said to me on the day after the night he left our house for good, twenty years into their marriage.

When I was fourteen, two years before my parents’ separation, I joined the junior varsity track team. Girls’ sports in 1973 was a faintly ridiculous notion, and the high school track coach, who was first and foremost the coach of the boys’ team, mostly ignored his distaff charges. I designed my own training regimen, leaving the house before dawn and loping the side streets to Mohansic State Park, a manicured recreation area that used to be the grounds for a state insane asylum, where I ran a long circuit around the landscaped terrain, alone. By then, I had developed a preference for solo sports.

Early one August morning I was lacing my sneakers in the front hall when I sensed a subtle atmospheric change, like the drop in barometric pressure as a cold front approaches or the prodromal thrumming before a migraine, which signaled to my aggrieved adolescent mind the arrival of my father. I reluctantly turned and made out his pale, thin frame emerging from the gloom at the bend of the stairs. He was wearing jogging shorts and tennis sneakers.

He paused on the last step and inspected the situation with his peculiar remove, as if peering through a keyhole. After a while, he said, “I am running also,” his thick Hungarian accent stretching out the first syllable, “aaaalso.” It was an insistence, not an offer. I didn’t want company. A bit of doggerel, picked up who knows where, spooled in my head.

Yesterday, upon the stair,

I met a man who wasn’t there

He wasn’t there again today

I wish, I wish he’d go away …

I pushed through the screen door, my father shadowing my heels. The air was fat with humidity. Tar bubbles blistered the blacktop. I poked them with the toe of one sneaker while my father deliberated, turning first to his old VW camper, then to the lime-green Fiat convertible he had recently purchased, used, “for your mother.” My mother didn’t drive. “Waaall,” he said after a while. “We’ll take the Fiat.”

We drove the five-minute route in silence. He wheeled into the lot of the IBM Research Center, a block from our destination. Prominent signs made clear that parking was for employees only. My father paid them no mind. He took a certain pride in pulling off small scams, which he called “getting awaaay with things,” a predilection that led him to swap price tags on items at the local shopping center. He acquired a camping cooker in this manner, at a savings of $25.

“Did you lock your door?” my father asked as we headed across the lot, and, when I said I had, he looked at me doubtfully, then turned and went back to check. The flip side of my father’s petty transgressions was an obsession with security.

We hoofed it down the treeless corporate drive to Route 202, the thoroughfare that runs along the north edge of the park. We dodged between speeding cars to the far side, and climbed over the metal divider, jumping down into the depression beyond it. My father paused. “It happened there,” he said. He often talked this way, without antecedents, as if mid-conversation, a conversation with himself. I understood what “it” was: some months earlier, after midnight, teenagers returning from a party had run the stop sign on Strang Boulevard and collided with another car. Both vehicles had hurtled over the divider and landed on their roofs. No one survived. A passenger was decapitated. My father had been witness not to the accident itself but to its immediate aftermath. He was on call that night with the Yorktown Heights Ambulance Corps.

My father’s eagerness to volunteer for the local emergency medical service had seemed out of character, at least the character I thought I knew. He shrank from community affairs, from social encounters in general. On the occasions when my parents had guests, my father would either sit mum in his armchair or take cover behind his slide projector, working his way through tray after tray of Kodachrome transparencies of our hiking expeditions, naming each and every mountain peak in each and every frame, recounting every twist and turn in the trail, until our visitors, wild with boredom, fled into the night.

He referred to his service with the ambulance corps as “my job saaaaving people.” Which I also didn’t understand. Our town was a place of non-events, the 911 summons a suburban emergency: a treed cat, a housewife having an anxiety attack, an occasional kitchen-stove fire. The crash in Mohansic State Park was an exception, although again there was no one to save. When my father arrived, the police were covering the bodies. The ambulance driver grabbed his arm. “Steve, don’t look,” my father recalled him saying. “You don’t want that in your memory.” The driver had no way of knowing the wreckage already lodged in my father’s memory, and of how hard he had worked to erase it.

Leaving the old accident site behind, the two of us took off running along the paved road and into the picnic area, past rows of empty parking lots. The route began on a dull flat stretch of baseball diamonds and basketball courts, then looped around the giant public pool (where I worked summers at the snack stand) and along Mohansic Lake, finishing up a long hill. By the lake, we picked up a narrow footpath. We ran without speaking, single file.

At the final climb, the path gave way to wider pavement, and we began jogging side by side. Minutes into the ascent, he picked up his pace. I sped up. He ran faster. So did I. He pulled ahead again, then I did. We both gasped for breath. I looked over at him, but he didn’t return my gaze. His skin was scarlet, shiny with sweat. He stared straight ahead, intent on an invisible finish line. All the way up the hill, the fierce mute maneuvering maintained. When the pavement flattened, I ached to ease the pace. My stomach was heaving and my vision had blurred. My father broke into a furious stride. I tried to match it. It was, after all, the early ’70s; “I Am Woman (Hear Me Roar)” played on the mental sound track of my morning jogs. But neither my ardor for women’s lib nor my youth nor all my training could compete with his determination.

Something about my father became palpable in that moment, but what? Was I witnessing raw aggression or a performance of it? Was he competing with his daughter or outracing someone, or something, else? These weren’t questions I’d have formulated that morning. At the time, I was trying not to retch. But I remember the thought, troubling to my budding feminism, that flickered through my mind in the final minutes of the run: It’s easier to be a woman. And with it, I let my legs slow. My father’s back receded down the road.

At home in those years, my father was a paragon of the Popular Mechanics weekend man, always laboring on his latest home craft project: a stereo and entertainment cabinet, a floor-to-ceiling shelving system, a dog house and pen (for Jání, our Hungarian vizsla), a shortwave radio, a jungle gym, a “Japanese” goldfish pond with recycling fountain. After dinner he would absent himself from our living quarters—our suburban tract home had one of those living-dining open-floor plans, designed for minimal privacy—and descend the steps to his Black & Decker workshop in the basement. I did my homework in the room directly above, feeling through the floorboards the vibration of his DeWalt radial arm saw slicing through lumber. On occasion, he’d invite me to assist in his efforts. Together we assembled an educational anatomy model that was popular at the time: “The Visible Woman.” Her clear plastic body came with removable parts, a complete skeleton, “all vital organs,” and a plastic display stand. For much of my childhood she stood in my bedroom—on the vanity dresser that my father also built, a metal base with a wood-planked top, over which he’d staple-gunned a frilled fabric with a rosebud pattern.

From his domain in the basement, my father designed the stage sets he desired for his family. There was the sewing-machine table with a retractable top he built for my mother (who didn’t like to sew). There was the to-scale train set that filled most of a room (its Nordic landscape elaborately detailed with half-timbered cottages, shops, churches, inns, and villagers toting groceries and hanging laundry on a filament clothesline) and the fully accessorized Mobil filling station (hand-painted Pegasus sign, auto repair lift, working garage doors, tiny Coke machine). His two children played with them with caution; a broken part could be grounds for a tirade. And then there was one of my father’s more extravagant creations, a marionette theater—a triptych construction with red curtains that opened and closed with pulleys and ropes, two built-in marquees to announce the latest production, and a backstage elevated bridge upon which the puppeteer paced the boards and pulled the strings, unseen. This was for me. My father and I painted the storybook backdrops on large sheets of canvas. He chose the scenes: a dark forest, a cottage in a clearing surrounded by a crumbling stone wall, the shadowy interior of a bedroom. And he chose the cast (wooden Pelham marionettes from FAO Schwarz): Hunter, Wolf, Grandmother, Little Red Riding Hood. I put on shows for my brother and, for a penny a ticket, neighborhood children. If my father ever attended a performance, I don’t remember it.

“Visiting family?” my seatmate asked. We were in an airplane crossing the Alps. He was a florid midwestern retiree on his way with his wife to a cruise on the Danube. My assent prompted the inevitable follow-up. While I deliberated how to answer, I studied the overhead monitor, where the Malév Air entertainment system was playing animated shorts for the brief second leg of the flight, from Frankfurt to Budapest. Bugs Bunny sashayed across the screen in a bikini and heels, befuddling a slack-jawed Elmer Fudd.

“A relative,” I said. With a pronoun to be determined, I thought.

In September 2004, I boarded a plane to Hungary. It was my first visit since my father had moved there a decade and a half earlier. After the fall of Communism in 1989, Steven Faludi had declared his repatriation and returned to the country of his birth, abandoning the life he had built in the United States since the mid-’50s.

“How nice,” the retiree in 16B said after a while. “How nice to know someone in the country.”

Know? The person I was going to see was a phantom out of a remote past. I was largely ignorant of the life my father had led since my parents’ divorce in 1977, when he’d moved to a loft in Manhattan that doubled as his commercial photo studio. In the subsequent two and a half decades, I’d seen him only occasionally, once at a graduation, again at a family wedding, and once when my father was passing through the West Coast, where I was living at the time. The encounters were brief, and in each instance he was behind a viewfinder, a camera affixed to his eye. A frustrated filmmaker who had spent most of his professional life working in darkrooms, my father was intent on capturing what he called “family pictures,” of the family he no longer had. When my boyfriend had asked him to put the camcorder down while we were eating dinner, my father blew up, then retreated into smoldering silence. It seemed to me that was how he’d always been, a simultaneously inscrutable and volatile presence, a black box and a detonator, distant and intrusive by turns.

Could his psychological tempests have been protests against a miscast existence, a life led severely out of alignment with her inner being, with the very fundaments of her identity? “This could be a breakthrough,” a friend suggested, a few weeks before I boarded the plane. “Finally you get to see the real Steven.” Whatever that meant: I’d never been clear what it meant to have an “identity,” real or otherwise.

In Malév’s economy cabin, the TV monitors had moved on to a Looney Tunes twist on Little Red Riding Hood. The wolf had disguised himself as the Good Fairy, in pink tutu, toe shoes, and chiffon wings. Suspended from a wire hanging off a treetop, he flapped his angel wings and pretended to fly, luring Red Riding Hood out on a limb to take a closer look. Her branch began to crack, and then the entire top half of the tree came crashing down, hurtling the wolf in drag into a heap of chiffon on the ground. I watched with a nameless unease. Was I afraid of how changed I’d find my father? Or of the possibility that she wouldn’t have changed at all, that he would still be there, skulking beneath the dress.

Grandmother, what big arms you have! All the better to hug you with, my dear.

Grandmother, what big ears you have! All the better to hear you with, my dear.

Grandmother, what big teeth you have! All the better to eat you with, my dear!

And the Wicked Wolf ate Little Red Riding Hood all up …

Malév Air #521 landed right on time at Budapest Ferihegy International Airport. As I dawdled by the baggage carousel, listening to the impenetrable language (my father had never spoken Hungarian at home, and I had never learned it), I considered whether my father’s recent life represented a return or a departure. He had come back here, after more than four decades, to his birthplace—only to have an irreversible surgery that denied a basic fact of that birth. In the first instance, he seemed to be heeding the call of an old identity that, no matter how hard he’d run, he’d failed to leave behind. In the second, she’d devised a new one, of her own choice or discovery.

I rolled my suitcase through the nothing-to-declare exit and toward the arrivals hall where “a relative,” of uncertain relation to me, and maybe to herself, was waiting.

2 (#ulink_d7d2ac8d-be4c-52f4-ac22-2bf95096dc24)

Rear Window (#ulink_d7d2ac8d-be4c-52f4-ac22-2bf95096dc24)

In my luggage were a tape recorder, a jumbo pack of AA batteries, two dozen microcassettes, a stack of reporter’s notebooks, and a single-spaced ten-page list of questions. I had begun the list the day I’d received the “Changes” e-mail with its picture gallery of Stefánie. If my photographer father favored the image, her journalist daughter preferred the word. I’d typed up my questions and, after much stalling, picked up the phone. I had to look up my father’s number in an old address book.

A taped voice said, in Hungarian and then in English, “You have reached the answering machine of Steven Faludi …” By then, more than a month had passed since she’d returned from Thailand. I added another to my list of questions: Why haven’t you changed your greeting? I left a message, asking her to call. I sat by a silent phone all that day and evening.

That night, in a dream, I found myself in a dark house with narrow, crooked corridors. I walked into the kitchen. Crouched against the side of the oven was my father, very much a man. He looked frightened. “Don’t tell your mother,” he said. I saw he was missing an arm. The phone rang. Jolted awake, I lay in bed, ignoring the summons. It was half past five in the morning. An hour later, I forced down a cup of coffee and returned the call. It wasn’t just the early hour that had stayed my hand. I didn’t want to answer the bedside extension. My list of questions was down the hall in my office.

“Haaallo?” my father said, with the protracted enunciation I’d heard so infrequently in recent years, that Magyar cadence that seemed to border on camp. Hallo. As my father liked to note, the telephone salutation was the coinage of Thomas Edison’s assistant, Tivadar Puskás, the inventor of the phone exchange, who, as it happened, was Hungarian. “Hallom!” Puskás had shouted when he first picked up the receiver in 1877, Magyar for “I hear you!” Would she?

I asked about her health, my pen poised above my reporter’s notebook, seeking safety in a familiar role. A deluge commenced. The notepad’s first many pages are a scribbled stutter-fest of unfinished sentences. “Had to pick up the papers for the name change, but you have to go to the office of birth records in the Seventh District for—, no, wait a minute, it’s the Eighth because the hospital I was born in—, waaall, no, let me see now, it maaay be …” “I’m so busy every day, I don’t have time for dilation, and they tell you to dilate three times a day, four times at first, waaall, you can do it two times probably, but—, there are six of these rods, and I’m only on the number 3 …”

The operation, I noted, had not altered certain tendencies—among them, my father’s proclivity for the one-sided rambling monologue on highly technical matters. When I was young, he had always operated on two modes: either he said nothing, or he was a wall of words, a sudden torrent of verbiage, flash floods of data points on the most impersonally procedural of topics. To his family, these dissertations felt like a steel curtain coming down, a screech of static jamming the airwaves. “Laying down covering fire,” we had called it. My father could hold forth for hours, and did, on the proper method for wiring an air conditioner, the ninety-nine steps for the preparation of authentic Hungarian goose pâté, the fine print in the regulatory practices of the Federal Reserve, the alternative routes to the first warming hut on the Matterhorn, the compositional revisions to Wagner’s score of Tannhäuser. My father had mastered the art of the filibuster. By the time he was finished, you’d forgotten whatever it was you’d asked that had triggered the oral counteroffensive—and were as desperate to flee his verbal bombardment as he was to retreat to his cone of silence.

“I could have gone to Germany, they cover everything,” my father rattled on, “but they make you jump through so many hoops, and, waaall, in the U.S., the surgery is vaaary expensive and it’s not in the front line, but, now, in Thailand, they have the latest in surgical techniques, the hospital has an excellent website where they go into all the procedures, starting with …” “I have to change the estrogen patch twice a week, it was fifty micrograms before the operation, but after the operation it gave me hot flashes, now it’s twenty-five micrograms and …” “I got the first hair implant in Hungary, five hundred thousand forints, it came out pretty good, but it’s still short in front, but maybe my hairdresser can do something, waaall, I could get another one, but it might be better in Vienna, yaaas but to go just for—, I’m taking hair growth medication, so—”

I quit trying to get it down verbatim.

“Long speech abt VW cmpr stolen,” I wrote. “Thieves evywhre. Groc store delivry this wk., many probs.” “Great trans sites online, evrythng on Internet, many pix dwnloaded.”

My attempts to cut through his verbal eruption—“Why have you done this?”—only inspired new ones.

“Waaall, but you couldn’t do it for a long time, waaall, you could, but it was risky. In Thailand, the hospital has greaaat facilities, faaantastic. In every room, bidets with special sprayheads, a unique nozzle that …”

I asked if she’d been dressing as a woman before.

“No. Waaall … Maybe a little … I have to pick up the papers to get my passport changed, and I need to get my name changed with the Land Registry, but first you have to go to the municipality office and get a certificate to bring to the Ministry of …”

“Why didn’t you tell us before you had the operation?”

“Waaall … I didn’t talk until everything was all right, successful. Dr. Sanguan Kunaporn, he was faaantastic, trained with one of the leading surgeons of vaginoplas—, his name was—, it’s—, no, wait—waaall, he is well-known as the best of—”

I lost my patience.

“You never talk to me. You aren’t talking to me now.”

Silence.

“Hello?” I ventured. Hallom?

“Waaall, but it’s not my fault. You never came here. Every year, you never came.”

“But you—”

“I have a whole dossier. They stole our property.” My father was referring to the two luxury apartment buildings that my grandfather once owned in Budapest. They had been commandeered by the Nazi-allied state during the Second World War, nationalized under the Communist regime, and then sold off to private owners after 1989. “You showed no interest whatsoever.”

“What am I supposed to do?”

“You’re a journalist. You should at least somewhere mention it. They’re consorting with thieves. Your country of birth, you know.”

“Mention to whom?” I asked, thinking: the country of my birth?

“A family should work together to get back their stolen property. A normal family stays together. I’m still your father.”

“You’re the one who—”

“I sent you the notice about my school reunion, and you never came,” my father said. The surviving members of my father’s high school class in Budapest had gathered in Toronto three years ago. Guilty as charged: I didn’t attend. “I sent you a copy of the movie I made of the reunion, and you never said anything.” She wasn’t finished. “One of my classmates lives near you, right in Portland, and I e-mailed you the Google map with his address, and you never contacted him. You never …”

I wasn’t sure how to respond to this writ of attainder.

After a while, I said, “I’m sorry.”

Then: “You said you were going to write my life story, and you never did.”

Had I said that?

“Is that what you want?”

We both went mute. I scanned my list of questions. What I wanted to ask wasn’t on the page.

“Can I come see you?”

I could hear her breathing in the silence.

In the arrivals hall at Ferihegy Airport, a line of people waited to greet passengers. I reluctantly scanned the faces. Maybe I wouldn’t recognize him as her. Maybe she wouldn’t be here. Maybe I could turn around and fly home. Salutations in two genders were gridlocked on my tongue. I wasn’t sure I was ready to release him to a new identity; she hadn’t explained the old one. Did she think sex reassignment surgery was a get-out-of-jail-free card, a quick fix to a life of regret and recrimination? I can manage a change in pronoun, I thought, but paternity? Whoever she was now, she was, as she herself had said to me on the phone, “still your father.”

I spotted a familiar profile with a high forehead and narrow shoulders at the far end of the queue, leaning against an empty luggage cart. Her hair looked thicker than I remembered his, and lighter in color, a henna-red. She was wearing a red cabled sweater, gray flannel skirt, white heels, and a pair of pearl stud earrings. She had taken her white pocketbook off her shoulder and hung it from a hook on the cart. My first thought, and it shames me, was: no woman would do that.

“Waaall,” my father said, as I came to a stop in front of her. She hesitated, then patted me on the shoulder. We exchanged an awkward hug. Her breasts—48C, she would later inform me—poked into mine. Rigid, they seemed to me less bosom than battlement, and I wondered at my own inflexibility. Barely off the plane, I was already rendering censorious judgment. As if how one carried a purse was a biological trait. As if there weren’t plenty of “real” women walking around with silicone in their breasts. Since when had I become the essentialist?

“Waaall,” she said again. “There you are.” After a pause: “I parked the camper in the underground lot, it’s a new camper, a Volkswagen Caaalifornia Exclusive, much bigger than my last one, the biggest one they make, the next-to-the-fastest engine, I got it from the insurance for the old one, it was one year on the market because the German economy is bad, the first one I bought was six years old, eighty thousand marks—forty-six thousand euros—fifty thousand dollars, the new one they sold to me for forty thousand euros, the insurance paid twenty thousand euros, it’s parked by the guard booth, it’s safer there, waaall, nothing’s safe, thieves stole my old camper right out of the drive, I had the alarm on, they must’ve disabled it, climbed the fence, thieves were probably watching the house, they saw no one was home for weeks and—”

“Dad, Stefánie, how are you? I want—” My desire got lost in my own incoherence.

“—and they came right into my yard, and the neighbors did aaabsolutely nothing, no one saw anything, waaall, that’s what they said. But they were great at Rosenheim, the man there was vaaary nice, he said to me, ‘Oh, meine gnädige Frau, it’s not safe for a woman to travel alone!’”

“Rosenheim?” I asked. I put my luggage on the cart, and she led the way to the parking garage. I trailed behind, watching uncomfortably the people watching us. The dissonance between white heels and male-pattern baldness was apparently drawing notice. Some double-chinned matrons gave my father the up-and-down. One stopped in her tracks and muttered something. I didn’t understand the words, but I got the intent. When her gaze shifted to me, I glared back. Fuck off, you old biddy, I thought.

“Rosenheim VW,” my father said, “in Germany, where I bought the new camper, aaand my old one, they do all my servicing and maintenance, aaand I register the camper there, you can’t trust anyone else to work on it, waaall, they’re German, they’re very good, and the man was very courteous. Now that I’m a lady, everyone treats me very nicely.”

We had no trouble finding the van. It was, as advertised in the brochure my father still had at home, VW’s biggest model (eight and a half feet high), “Der California Exclusive.” It looked like a cruise ship beached in a parking lot, a ziggurat on wheels. A heavily defended ziggurat: my father had installed a wrap-around security system, which she set off twice while trying to unlock the driver’s door. Right there in the airport lot, she gave me the tour: the doll-sized kitchenette (two-burner gas cooker, fridge, sink, fold-out dining table, and pantry with pots and pans and well-stocked spice rack), a backseat bench that opened into a double bed (an overhead stowaway held duvet, linens, and pillows), a wardrobe with a telescopic clothesrail, and, in the very rear, a tiny bathroom and closet (with towels, toiletries, wall-mounted mirror). She opened up the cabinets to show me the dishware she’d just purchased, a tea service in a rosebud pattern.

I couldn’t quite put the disparities into focus: Motor Trend meets Marie Claire. Was this why I’d flown fifty-six hundred miles? Here we were, meeting after twenty-seven years, a high-stakes reunion after a historic Glasnost, and she was acting like she’d just returned from Williams-Sonoma by way of NAPA Auto Parts.

“Ilonka helped me pick it out,” my father said, handing me a saucer to admire.

Ilonka—I had met her; for some years after my father returned to Hungary she’d been what he called his “lady friend.” She had accompanied my father to a family wedding in California, but I hadn’t gleaned much from our encounter: she spoke no English. I wasn’t clear on their relationship—though Ilonka would tell me later that it was platonic. She was married and very Catholic. For years she seemed to function as an unpaid housekeeper for my father, cleaning, cooking, sewing. She helped him pick out the furnishings for his house, from the lace curtains to the vintage Hungarian Zsolnay porcelain (purchased to impress a snooty couple, distant kin of Ilonka’s, who had come to dinner at my father’s house one night; the husband had claimed to be a “count”). My father had taken Ilonka on trips around Europe and loaned money to her family. When one of her grandchildren was born, my father assumed the duties of godfather, now godmother.

“How is Ilonka?” I asked.

My father made a face. “I don’t see her so much.” She took the saucer from me and placed it carefully on the cabinet shelf with its mates. The problem evidently was Ilonka’s husband. “It was fine with him when I was the man buying things for his wife and giving money to his family. But now that I’m a woman, I’ve been banished.”

She shut and secured the cupboard doors. We went around to the front. It took some effort to hoist ourselves into the elevated cockpit. My father disengaged the clutch and shifted into reverse and we lurched backward, nearly plowing into a parked car. I noted with dismay that the makers of the well-appointed Exclusive had excluded one feature: a usable rear window. The tiny transom above the commode showed only empty sky.

At the pay booth, she fished through her purse for her wallet. The ticket taker, another Magyar babushka, stuck her head out the window and gave my father the once-over. As the bills were counted, I studied my father, too. I could see the source of her thickening hair (a row of implant plugs) and the lightened color (a dye job). Her skin had a glossy sheen. Foundation powder? Estrogen? What struck me most forcefully, though, wasn’t what was new. I’d spotted it in the airport—that old nervous half-smile, that same faraway gaze.

On the road, she steered the lumbering Gigantor into the fast lane. It was rush hour. A motorist trailing us in a rusted subcompact blasted his horn. My father leaned out the window and swore at him. The honking stopped. “When they see I’m a laaady, they pipe right down,” she said.

We merged onto a highway, and I gazed out the window at the dilapidated industrial back lots flying by, a few smokestacks belching brown haze, boarded-up warehouses with greasy windows, concrete highway dividers slathered in graffiti. We passed through a long stretch of half-finished construction, grasses growing high over oxidizing rebar. Along the shoulder, billboards proliferated, shiny fresh faces flashing perfect teeth, celebrating the arrival of post-Communist consumption: Citibank, Media Markt, T-Mobile, McDonald’s. Big balls of old mistletoe parched in the branches of trees. Along the horizon, I could make out the red-roofed gables of a distant hamlet.

Half an hour later, we entered the capital. My father threaded the monster vehicle through the tight streets of downtown Pest, shadowed by Art Nouveau manses nouveau no longer, facades grimy and pockmarked by a war sixty years gone. A canary-yellow trolley rattled by, right out of a children’s book. We drove past the back end of the Hungarian Parliament, a supersized gingerbread tribute to the Palace of Westminster. In the adjacent plaza, a mob of young men in black garb and black boots were chanting, waving signs and Hungarian flags.

“What’s that about?” I asked.

No answer.

“A demonstration?”

Silence.

“What—”

“It’s nothing. A stupid thing.”

Then we were through the maze and hugging an embankment. The Royal Palace, a thousand-foot-long Neo-Baroque complex perched on the commanding heights of Castle Hill, swung into view on the far bank of the Danube, the Buda side. My father swerved the camper onto a ramp and we ascended the fabled Chain Bridge, its cast-iron suspension an engineering wonder of the world when it opened in 1849, the first permanent bridge in Hungary to span the Danube. We passed the first of the two pairs of stone lions that guard the bridgeheads, their gaze stoical, their mouths agape in perpetual, benevolent roar. A faint memory stirred.

The camper crested the bridge and descended to the Buda side. We followed the tram tracks along the river for a while, then began the trek into the hills. The thoroughfares became leafier, the houses larger, gated, many surrounded by high walls.

“When I was a teenager, I used to ride my bicycle around here,” my father volunteered. “The Swabian kids would say, ‘Hey, you dirty little Jew.’” She lifted a hand from the wheel and swatted at the memory, brushing away an annoying gnat. “Yaaas but,” she answered, as if in dialogue with herself, “that was just a stupid thing.”

“It doesn’t sound—” I began.

“I look to the future, never the past,” my father said. A fitting maxim, I thought, for the captain of a vehicle without a rear window.

Growing up, I’d heard almost nothing about the paternal side of my family. My father rarely spoke of his parents, and never to them. I learned my paternal grandfather’s first name in 1967, when a letter arrived from Tel Aviv, informing us of his death. My mother recalled aerogrammes with an Israeli postmark arriving in the early years of their marriage, addressed to István. They were from my father’s mother. My mother couldn’t read them—they were in Hungarian—and my father wouldn’t. My mother wrote back a few times in English, bland little notes about life as an American housewife: “Between taking care of Susan, cooking, and housekeeping, I’m very busy at home … Steven works a lot, plus many evenings doing ‘overtime.’” An excuse for his silence? By the early ’60s, the aerogrammes had stopped.

I knew a few fundamentals. I knew my father’s birth name: István Friedman, or rather, Friedman István; Hungarians put the surname first. He’d adopted Faludi after World War II (“a good authentic Hungarian name,” my father had explained to me), then Steven—or Steve, as he preferred—after he’d moved to the United States in 1953. I knew he was born and raised Jewish in Budapest. I knew he was a teenager during the Nazi occupation. But in all the years we lived under the same roof, and no matter how many times I asked and wheedled and sometimes pleaded for details, he spoke of only a few instances from wartime Hungary. They were more snapshots than stories, visual shrapnel that rattled around in my childish imagination, devoid of narrative.

In one, it is winter and dead bodies litter the street. My father sees the frozen carcass of a horse in a gutter and hacks off pieces to eat. In another, my father is on a boulevard in Pest when a man in uniform orders him into the Grand Hotel Royal. Jews are being shot in the basement. My father survives by hiding in the stairwell. In the third, my father “saves” his parents. How? I’d ask, hungry for details, for once inviting a filibuster. Shrug. “Waaall. I had an armband.” And? “And … I saaaved them.”

As the camper climbed the switchbacks, I gazed out at the terra-cotta rooftops of the hidden estates, trying to divine the outlines of my father’s youth. As a child and until the war broke out, he’d spent every summer in these hills. The Friedmans’ primary address was on the other side of the Danube, in a capacious flat in one of the two large residential buildings my grandfather owned in fashionable districts of Pest. My father referred to the family quarters at Ráday utca 9 as “the royal apartment.” But every May of my father’s childhood, the Friedmans would decamp, along with their maid and cook, to my grandfather’s other property in the hills, the family villa. There, an only child called Pista—diminutive for István—would play on the sloping lawn with its orchards and outbuildings (including a cottage for the resident gardener), paddle in the sunken swimming pool, and, the year he contracted rheumatic fever, lie on a chaise longue in the sun, tended by a retinue of hired help. As we ascended into the hills of Buda I thought, here I am in the city that was the forge of my father’s youth, the anvil on which his character was struck. Now it was the stage set of her prodigal return. This proximity gave me a strange sensation. All my life I’d had the man without the context. Now I had the context, but with a hitch. The man was gone.

3 (#ulink_234016ac-306d-55b5-9f8e-a444ea663b3c)

The Original from the Copy (#ulink_234016ac-306d-55b5-9f8e-a444ea663b3c)

I’d met the lions on the Chain Bridge before, when I was eleven. We were on a family vacation in the summer of 1970: my mother, my father, my three-year-old brother, and me. It was, all and all, a vexed journey. One evening we drove across the river to attend an outdoor performance of Aida. I remember the crossing for its rare good cheer; family trips were always fraught affairs. The car seemed to float over the Danube, the cable lights winking at us from above, the leonine sentries heralding our arrival to the city. My father reminisced about how his nurse used to push his pram past the lions and over the bridge to the base of the Sikló, a charming apple-red funicular that chugged up the Castle Hill palisade. He told us the story about the sculptor who had forgotten to carve tongues for the lions: a child had pointed out their absence at the opening ceremonies, and the humiliated artist leaped off the bridge into the Danube. It was a popular tale in Hungary, he’d said, but “probably not true.”

Castle Hill, my father informed us, was honeycombed with subterranean caverns, carved out of the limestone millennia ago by thermal springs coming up “from the deep.” The occupying Turks had turned them into a giant labyrinth. “They say Vlad the Impaler—the real-life Dracula!—was locked up down there.” During World War II, the caves were retrofitted to accommodate air raid shelters and a military hospital. Thousands of the city’s inhabitants took refuge here for the fifty days of the Siege of Budapest. “It’s said that some people even had their mail delivered here,” my father reported. “But that’s probably a made-up story, too.”

Some days earlier, we had driven to Lake Balaton, south of Budapest. I remember walking a long way out into the shallow lake, the water only reaching my thighs. No matter how far I fled from shore, I could still hear my parents, their voices raised in acrid argument. The sour climate extended beyond our domestic circle. A scrim of sullenness seemed to hang over every encounter: the long waits in queues to receive a stamp so that we could proceed to other long queues to be issued other certifications of approval from scowling apparatchiks; the pitiful settee spitting yellowed foam in the guest room my father had rented; our aged landlady’s resentful eyes, sunk deep in a walnut-gnarled face, as she gave us each morning a serving of boiled raw milk, a thick curdled rind floating on its surface; the murky intentions of the “priest” in vestments who approached us one day after we’d toured the Benedictine monastery of Pannonhalma, asking my father if he’d deliver a letter to “friends” in the States—a government agent, my father said. The day we crossed the border into Hungary from Austria, customs officers combed through every inch of our luggage. My father stood to the side, uncomplaining, eager to please, a strange servility in his voice.

Throughout that visit, my father was in search of “authentic” Magyar folk culture. Driving through the countryside, we stopped to watch “traditional village dances” that were, in fact, staged tourist attractions: the government paid locals to whirl in what was billed as the national dress, the women in ornamental aprons and floral wreaths, the men in black vests and high leather boots. (As I’d learn later, the outfits and dances were only marginally traditional: they had been enshrined by urban nationalists in the mid-nineteenth century, and again in the interwar years, to create the impression of an ancient Magyar heritage.) In a village shop, my father insisted I try on folk dresses. As I modeled elaborately embroidered frocks, while cradling an elaborately clad Hungarian doll in my arms, my father took what felt like far too many rolls of film. The shop owner played stylist. Eventually my father purchased a lace-up bodice-and-dirndl number with a puffy-sleeved embroidered chemise, bell-shaped blue skirt, and a starched white apron with a tulip and rosebud motif. He thought I could wear it to school. His American daughter thought there was no way in hell she was going to junior high dressed as the Hungarian Heidi.

That fall, there ensued a series of tense standoffs over The Dress. My father would demand I put it on in the morning before school. I’d wait until he left for work, then run upstairs and change. He caught me once in suburban mufti. I was ordered to wear the costume to school the next day, which I did in a state of high mortification. Eventually he lost interest, and I banished the dress to the back of my closet. A year or so later, with hippie garb in vogue, I dug the offending garment out from its purgatory, detached the embroidered chemise from the rest of the outfit, and paired it with acid-washed jeans. It was my attempt at an au courant peasant look. Which was about as “authentic” as my father’s Hungarian folk fashions.

The visual chronicle of this vacation resides in a stack of Kodak carousels that my father kept for the rest of her life in an attic closet, slide after slide of my mother and me and my brother in the shadow of Gothic cathedrals and castle ruins, leaning against the rails of a Danube cruise boat, waving from a train at a saluting Pioneer scout in starched uniform and red neckerchief, or staring up at the mammoth Hungarian Parliament topped by a red star. We often face away from the camera. Many of the shots are taken from a distance, as if my father were on safari, tracking a fleeing herd.

On that long-ago trip we took a break from sightseeing one day to visit two apartment buildings in Pest, fin de siècle Vienna-Secession edifices once grandly appointed, now derelict and coated in soot. Tatty shutters hung catawampus over the graceful arched windows of Váci út 28; the ceremonial balconies of Ráday utca 9 were visibly rotting. At Ráday 9, we climbed a set of dimly lit stairs to knock on a door. And toured a series of high-ceilinged rooms, partitioned now with plywood boards, shabbily furnished and overflowing with tenants, several families jammed into living quarters meant for one. I remember especially my father’s distress. This building, like the other one, once belonged to my grandfather. The flat was my father’s childhood domicile, the “royal apartment.” On the sidewalk again, my father looked back up at the dingy facade of Ráday 9, where a blond girl in a white hair ribbon peered down from a crumbling double balcony, the one attached to the opulent rooms where a boy named Pista had grown up. He took a photograph. It was the last frame on the roll.

In 1940, when Pista turned thirteen, he’d received a Pathé 9.5mm movie camera. It was a bar mitzvah gift from his father. From then on—in Hungary where he joined an amateur film society during the war and a youth film club right after, in Denmark where he started a movie-distribution business, in Brazil where he made documentaries in the rain forests and on the pampas—my father would continue to prefer the moving picture over the still one. “With photography, you get one chance,” my father told me once. “You’re stuck with that shot. With film, you can cut it up and change it all around. You can make the story come out the way you want it.”

For a brief time in my infancy, my father’s filmmaking enterprises were domestic. In a box in my cellar, I possess the results, salvaged from a trash can, where my mother had relegated them after the divorce. A set of metal canisters holds the reels of the 16mm home movies my father had made from 1959 to 1961, the two years following my birth. My parents and I were living then in Jackson Heights, Queens, in a tiny upstairs rental in a brick duplex, and the films record the banal milestones of newlywed life: my mother large with child and eating pizza in her third trimester, my mother pushing a baby stroller and washing diapers in a plastic bucket, my first birthday, my first day at the beach, my first Easter Parade and Christmas. The “director,” as my father listed himself in the credits, makes an occasional appearance. In a shot filmed with the aid of a tripod, my father poses just inside the front door of our apartment, impersonating the man he aspired to be. He is wearing a suit and tie, a herringbone coat, leather gloves, a fedora. His gaze is trained on the camera. He leans over to give my mother an awkward peck on the cheek. Then he gives a stagy wave and mimes something in the direction of my mother, his eyes still fixed on the lens, and heads out the door. It’s a silent film, but I can script the “Father Knows Best” voice-over.

The longest reel is dedicated to Christmas. The camera lingers on the tree—reverential close-ups of frosted ornaments, tinsel strands, a large electric nativity star. Then a slow pan over the three red-and-white-striped stockings tacked to the wall in descending order. Poppa Bear, Mama Bear, Baby Bear. And finally the ceremonial unwrapping of the gifts: my father holds up each of his to the camera—tie, striped pajamas, Champion Dart Board. He mugs a forced grin and mouths, “Just what I wanted for Christmaaas!” My mother sits cross-legged on the floor in a ruffled blouse and pleated skirt, staring at her gifts with a wan expression: apron, bedroom slippers, baby-doll nightie.

In the final minutes of “Susie’s First Christmas,” the camera shifts to an eight-month-old me, wobbling to a precarious standing position before the full-length hall mirror, baby-fat fingers scrabbling along the slick surface for a purchase. I press my nose and then crush my whole face against the mirror, as if searching for something behind the reflection. What the film hid, I thought as I watched it decades later, was my father. Who was nowhere more absent than in the brief moments when he appeared on-screen, surrounded by the props of his American family, parading an out-of-the-box identity before the camera, splicing himself, frame by frame, into a man whose story had been replaced by an image, an image of anyone and no one.

By then, he was working in a darkroom in the city, commuting to a windowless chamber that would become as thoroughly his domain as our suburban basement. He became a master of photographic development and manipulative techniques: color conversions, montages, composites, and other transmutations of the pre-Photoshop trade. “Trick photography,” he called it. He always smelled of fixer.

My father was particularly skilled at “dodging,” making dark areas look light, and “masking,” concealing unwanted parts of the picture. “The key is control,” he liked to say. “You don’t expose what you don’t want exposed.” In the aquarium murk where he spent his daytime hours, hands plunged in chemical baths, a single red safelight for navigation, he would shade and lighten and manipulate, he would make body parts, buildings, whole landscapes disappear. He had achieved in still photography what he had thought possible only in film. He made the story come out the way he wanted it to.

His talent made him indispensable in certain quarters—most notably in Condé Nast’s art production department. From the ’60s to the ’80s, Condé Nast relied on my father to perform many of the most difficult darkroom alterations for the photography that appeared in its premier magazines, Vogue, Glamour, House & Garden, Vanity Fair, Brides. For years a note that one magazine art director had sent to another hung in my father’s studio: “Send it to Steve Faludi—don’t send it to anyone else!” My father performed his “tricks” on the work of some of the most celebrated fashion photographers of the time—Richard Avedon, Francesco Scavullo, Irving Penn, Bert Stern—at several commercial photo agencies and, later, on his own at his one-man business, Lenscraft Studios, in a garment-district loft previously occupied by fashion photographer Hank Londoner. He also worked his magic on many vintage photographs whose negatives had been lost; he could create a perfect copy from a print. Among the classic images he worked on were those by the preeminent Hungarian photographer (and World War II Jewish refugee), André Kertész. My father’s handiwork “was so precise and close and meticulous, there would be no bleeding of color or light,” Dick Cole, the director of Condé Nast’s art production department in that period, told me many years later, as we sat in his living room in Southern California, leafing through glossy coffee-table books that featured my father’s artifice. “It was amazing. You could never tell what had been changed. You couldn’t tell the original from the copy.”

Occasionally as a small child I would take the commuter train to the city with my father and visit one of the series of Manhattan photo agencies where he worked. He’d lead me to the other side of the partitioned studio, where men perched on high stools before light tables, effacing with fine-tipped brushes the facial imperfections of fashion models. He regarded retouching as the crowning glory of the photographic arts. He would hold up the before-and-after shots of ad copy for me to appreciate. See, she no longer has that unsightly mole! Look, no more wrinkles! He admired the men bent over those light tables, obliterating blemishes. My father rarely involved himself with my educational or professional prospects. But he did, several times, advise me to become a retoucher. Which was peculiar counsel for a daughter who was consumed, from the day she first joined the staff of her grade school newspaper, with exposing flaws, not concealing them. At the heart of our relationship, in the years we didn’t speak and, even more, in the years when we would again, a contest raged between erasure and exposure, between the airbrush and the reporter’s pad, between the master of masking and the apprentice who would unmask him.

4 (#ulink_5671f42b-a33e-5251-b410-13bfd95dfd96)

Home Insecurity (#ulink_5671f42b-a33e-5251-b410-13bfd95dfd96)

Hegyvidék (literally, “mountain-land”), the XIIth district of Budapest, is high in the Buda Hills. Always an exclusive enclave—home to embassies, villas, the residences of the nouveaux riches—its palatial properties were hot investments in post-Communist, new-millennial Budapest. As the broken-English text from one online real estate pitch I read put it, Hegyvidék is “the place where the luxury villas and modern detached houses—as blueblood estates—are ruling their large gardens in the silent milieu.” To reach my father’s address required negotiating several steep inclines and then a series of hair-raising tight turns on increasingly potholed and narrow roads.

“Damn Communists,” my father said, as the Exclusive plunged in and out of craters in the macadam. “They never fix the streets.”

“Weren’t they fifteen years ago?” I said.

“Waaall, they call themselves the ‘Socialists’ now”—she was speaking of the party in power at the time—“but it’s the same thing. A bunch of thieves.”

The camper wheezed up the final precipice and around a tight curve. A house loomed into view, a three-story concrete chalet. It had a peaked roof and stuccoed walls. A security fence ringed the perimeter, with a locked and alarmed gate. A large warning sign featured a snarling, and thankfully nonexistent, German shepherd.

I wasn’t sure whether the bunkered fortress was an expression of my father’s hypervigilance or that of the culture she’d returned to. Later, I read Colin Swatridge’s A Country Full of Aliens, a reminiscence of the British author’s residence in Budapest in the ’90s, and was struck by his remarks on the Hungarian fetish for home protection:

You may peer at the grandiosity of it all—at the grey-brick drive and the cypress trees, and the flight of steps, and the juttings, and the recesses, and the columns and the quoins—but you may do this only through the ironwork of the front gates, under the watchful eyes of a security camera, and of movement-sensitive security lights. It is fascinating, this need to reconcile security and self-display. The house must show its feminine lacy mouldings, its leggy balusters, its delicate attention to detail, its sinuous sweep of steps; yet it must also show its teeth, and muscular locks, and unyielding ironwork. It must be at once coy and assertive, like a hissing peacock—a thing beautiful and ridiculous …

What is, perhaps, characteristically Hungarian about these green-belt houses, these kitsch castles in the Buda Hills and the Pilis Hills, by Lake Balaton and the Bükk, is the conflation of exhibitionism with high security. It is akin to the confusion of the feminine and the masculine that is a feature of the language.

I knew all about that linguistic confusion. It was a staple of my childhood. “Tell your mother I’m waiting for him,” my father would say. Or “Your brother needs to clean up her room.” Hungarians are notorious for mixing up the sexes in English. Magyar has no gendered pronouns.

My father steered the camper to the far shoulder and yanked on the parking brake. She teetered perilously across the road in her white heels and keyed in the code in a box installed on the defending wall, and the gate creaked open—and shut again as soon as we’d pulled through. The camper labored up the steep driveway and came to a halt in a grassy patch—it was too tall to fit in the house’s two-car garage. A twenty-five-foot flagpole presided over the front lawn. It had three ropes, “so I can show all my flags,” my father told me. “I put up the Hungarian flag on March 15”—National Day, commemorating Hungary’s failed 1848 revolution against the Austrian Empire—“and the U.S. flag on July 4.” The third rope periodically hoisted the banners of my father’s other past residences, Denmark and Brazil.

My father scrambled down from the pilot’s seat and swung her purse over one shoulder. We stood in the drive for what felt to me like a good quarter hour while she fussed with various security measures. First she had to reengage the VW’s internal burglar alarm. Then she had to reset an outdoor surveillance system that “protected” the driveway. Once it was armed, we had sixty seconds to hurry to the front door, the one on the right. The house was a duplex; the other side-by-side identical unit, a doppelgänger residence, stood empty.

Before we entered, my father disarmed a third alarm system—and reactivated it as soon as we got inside. While she punched in numbers, I tried to find my bearings in the gloom. We were standing in a dark hallway. To the right was a stairwell, shrouded in shadow. Wooden steps ascended two levels. At the far end of the hall, through an open door, I caught a glimpse of yellow kitchen cabinets, the same cabinets that had adorned his Manhattan loft. (My father had shipped them, along with the refrigerator, dishwasher, oven, and everything else he owned at the time, including a giant stash of lumber and his VW van, in a forty-foot crate.) She led me down the hall and through another door on the left, which led to a large tiled living room and, off it, a dining room with a chandelier and a display case full of Zsolnay china.

A wall of glass with French doors overlooked the front terrace, but they, too, were dark, the thick drapes closed. “Someone could look in and want to steal my electronic equipment,” she said. She had a lot of it to steal. A wall-mounted cabinet system in the living room was filled, floor to ceiling, with monitors, receivers, amplifiers, speakers, woofers, CD, DVD, VHS, and Betamax players, a turntable, even a reel-to-reel tape machine. The last served to play her old opera recordings, the same ones my father used to blast every weekend in our suburban living room in Yorktown Heights. A half dozen cabinets contained a thousand or more operas on CDs, tapes, videos, and record albums.

Bookshelves lined the opposite wall. On one end were all my father’s old manuals on rock climbing, ice climbing, sailboat building, canoeing, woodworking, shortwave-radio and model-airplane construction. The My-Life-as-a-Man collection, I thought. Not that there was a corresponding woman’s section. Other shelves were populated with works devoted to all things Magyar: Hungarian Ancient History, Hungarian Fine Song, Hungarian Dog Breeds, and thick biographies of various Hungarian luminaries, including a two-volume set of memoirs by Countess Ilona Edelsheim Gyulai, the daughter-in-law of Admiral Miklós Horthy, the Regent who ruled Hungary during all but the final months of World War II.

Another section of books belonged to a genre that was as lifelong a preoccupation of my father’s as opera: fairy tales. Even as a girl, I understood that the puppet theater and the toy-train landscapes my father constructed were only ostensibly for his children. They gratified his craving for storybook fantasy. And the more extravagant the fantasy, the better. Likewise with opera. He hated a production that wasn’t lavishly costumed and staged. The two obsessions were, in fact, conjoined. One of my father’s most treasured childhood memories is of the night when his parents first took him to the Hungarian Royal Opera House. He was nine, and the opera was Hansel and Gretel.

“I wish I still had that book,” my father said, gazing over my shoulder at her impressive assortment of fairy tales. She was referring to a children’s anthology that the first of several nannies had read to Pista in his infancy. The nursemaid was German, and her mother tongue would become her young charge’s first language. “Leather binding, thick pages, gorgeous illustrations,” my father reminisced. “A gem. Whenever I go to a bookstore, I look for it.” Over the years she’d amassed many similar volumes, most featuring the tales of her most beloved storyteller, Hans Christian Andersen. She owned editions of his works in Danish, German, English, and Hungarian. (And could read them all. Like so many educated Hungarians, my father was a polyglot, fluent in five languages, plus Switzerdeutsch.) In 1972, when we took a family vacation to Denmark, my father made repeated pilgrimages to the Little Mermaid statue in Copenhagen’s harbor. I remember him standing for a long time by the seawall, pondering the sculpture of the sea nymph who cut out her tongue and split her tail to become human. I had studied him as he studied the statue, a girl in bronze on a surf-swept rock, her pain-racked limbs tucked beneath a nubile body, her mournful eyes turned longingly toward shore. My father had taken many pictures.

In idle moments on my first visit to Hegyvidék, and on the visits to come, I would take down from the shelf the English version of Hans Christian Andersen’s collected stories and leaf through its pages, repelled and riveted by the stories of mutilation and metamorphosis, dismemberment and resurrection: The vain dancing girl who has her feet amputated to reclaim her virtue. The one-legged tin soldier who falls in love with a ballerina paper cutout and, hurled into a stove, melts into a tiny metal heart. The lonely Jewish servant girl who dreams her whole life of being a Christian—and gets her wish at the resurrection. And most famously, the despised runt of the litter who grows into a regal cygnet. “I shall fly over to them, those royal birds!” says the Ugly Duckling. “It does not matter that one has been born in the hen yard as long as one has lain in a swan’s egg.” And I’d wonder: if the duckling only becomes a swan because he is born one, if the Little Mermaid cleaves her tail only to return to the sea, what kind of transformation were these stories promising?

On still more shelves on the living-room wall kitty-corner to the electronic equipment, stacks of photo albums contained snapshots from my father’s multiple trips to Odense, Andersen’s birthplace. “I took Ilonka there once,” my father said. “I think she was a little bored.” Flipping through them, I was startled to find a familiar townscape: the distinctive step-gabled roof of Vor Frue Kirke (the Church of Our Lady), a GASA produce shop (a Danish market cooperative), and the half-timbered inn of Den Gamle Kro (there’s an inn by that name a block from the Hans Christian Andersen Museum). Had my father reproduced the city of Odense in the train set he’d installed in our playroom? Later, when I inspected the two photos I still had of our childhood model railroad, I admired all the more the particularity of my father’s verisimilitude. The maroon snout of the toy locomotive bore the winged insignia and royal crown of the Danish State Railway.

Above the Odense photo albums, on two upper shelves, a set of figurines paraded: characters from The Wizard of Oz. My father had found them in a store in Manhattan, after my parents divorced and he’d moved back to the city. They were ornately accessorized. Dorothy sported ruby-red shoes and a woven basket, with a detachable Toto peeking out from under a red-and-white-checked cloth. The Tin Man wore a red heart on a chain and clutched a tiny oil can. The Scarecrow spewed tufts of straw, and the Lion displayed a silver-plated medal that read COURAGE. My father had strung wires to the head and limbs of the green-faced Wicked Witch of the West, turning her into a marionette. I paused before the dangling form and gave it a furtive push. The witch bobbled unsteadily on her broom.