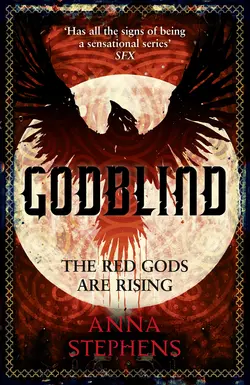

Godblind

Anna Stephens

Fantasy’s most anticipated debut of the yearThere was a time when the Red Gods ruled the land. The Dark Lady and her horde dealt in death and blood and fire.That time has long since passed and the neighbouring kingdoms of Mireces and Rilpor hold an uneasy truce. The only blood spilled is confined to the border where vigilantes known as Wolves protect their kin and territory at any cost.But after the death of his wife, King Rastoth is plagued by grief, leaving the kingdom of Rilpor vulnerable.Vulnerable to the blood-thirsty greed of the Warrior-King Liris and the Mireces army waiting in the mountains…GODBLIND is an incredible debut from a dazzling new voice of the genre.

Copyright (#ulink_efcbcf3b-a5e5-5421-a1e1-604235e2d34f)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2017

Copyright © Anna Stephens 2017

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Anna Stephens asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this bookis available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008215897

Ebook Edition © June 2017 ISBN: 9780008215910

Version: 2018-01-29

Dedication (#ulink_3e9d2403-e08e-552b-8929-a52737dc8185)

For my Uncles, David and Graham.

I wish you could have seen this.

Map (#u19cf0383-bd59-576c-b915-6d0eb3617ed3)

Contents

Cover (#u1f301fd1-08c0-5260-95f9-f4c3922d35e3)

Title Page (#uc6dc7ee0-a33c-590b-82e6-2ba46021ecdf)

Copyright (#u2546c6cf-2bec-58de-9150-c9c929291a35)

Map

Dedication (#u4da36cd5-7c5e-5130-98fa-c50dbe964ce7)

Rillirin (#u2701cfa4-e3d4-586d-a97b-b5ed3ebefc6c)

Corvus (#u1e32df18-638f-5150-bf33-91b437791683)

Crys (#u7bf01e14-a0bb-5474-ae04-cb7eb4678bd7)

Durdil (#uf7882f88-ef2e-5f83-be66-967218410e2d)

Dom (#ua347542f-ed2d-5e41-887d-ff53b18083a8)

The Blessed One (#u73479f24-857d-5d7b-958e-b0ecb0ccffb1)

Crys (#u41f1690d-87ca-59bc-9895-82c4e9914f88)

Rillirin (#u837640e2-c148-5295-8866-7ce432a7cf25)

Galtas (#u1efadb91-bdfb-5482-8c18-e7d395b1240b)

Dom (#u025f94ab-8801-58e6-87d5-f554ee020e7f)

Rillirin (#u4de5c4b2-9b4b-513a-aadd-9e1e582b15e3)

Corvus (#u0d7e9b37-ea5e-5552-a03f-f77ee0642999)

Dom (#ue9e8e67e-3211-5d69-909a-40c9d08829f0)

Mace (#ufaacaab4-e02a-52a4-ac98-436a94968027)

Crys (#uaee01569-c935-5bbe-bb37-a1561179b3e8)

Tara (#ue95c37ce-bb90-555c-91a9-0b134ded4590)

Galtas (#ue5e2e63c-bf9a-5fa1-a097-dc87ac0280b4)

The Blessed One (#uee5dd108-bf00-5f9d-8043-54937269d2b7)

Durdil (#u47cde848-8569-5903-8ade-58cb7aa4c8c4)

Dom (#u27ee600e-6c20-56f7-988d-da88351d27ec)

Crys (#litres_trial_promo)

Rillirin (#litres_trial_promo)

Galtas (#litres_trial_promo)

Crys (#litres_trial_promo)

Gilda (#litres_trial_promo)

Mace (#litres_trial_promo)

Corvus (#litres_trial_promo)

Crys (#litres_trial_promo)

Galtas (#litres_trial_promo)

Dom (#litres_trial_promo)

Rillirin (#litres_trial_promo)

Tara (#litres_trial_promo)

Dom (#litres_trial_promo)

Rillirin (#litres_trial_promo)

Corvus (#litres_trial_promo)

Dom (#litres_trial_promo)

Gilda (#litres_trial_promo)

Crys (#litres_trial_promo)

Durdil (#litres_trial_promo)

The Blessed One (#litres_trial_promo)

Mace (#litres_trial_promo)

Rillirin (#litres_trial_promo)

Dom (#litres_trial_promo)

Durdil (#litres_trial_promo)

Galtas (#litres_trial_promo)

Durdil (#litres_trial_promo)

Tara (#litres_trial_promo)

Crys (#litres_trial_promo)

Corvus (#litres_trial_promo)

Durdil (#litres_trial_promo)

Dom (#litres_trial_promo)

Crys (#litres_trial_promo)

Gilda (#litres_trial_promo)

Crys (#litres_trial_promo)

Rillirin (#litres_trial_promo)

Mace (#litres_trial_promo)

Galtas (#litres_trial_promo)

Durdil (#litres_trial_promo)

The Blessed One (#litres_trial_promo)

Dom (#litres_trial_promo)

Tara (#litres_trial_promo)

Rillirin (#litres_trial_promo)

Dom (#litres_trial_promo)

Mace (#litres_trial_promo)

Galtas (#litres_trial_promo)

Tara (#litres_trial_promo)

Gilda (#litres_trial_promo)

Mace (#litres_trial_promo)

Rillirin (#litres_trial_promo)

Tara (#litres_trial_promo)

Mace (#litres_trial_promo)

Corvus (#litres_trial_promo)

Dom (#litres_trial_promo)

Crys (#litres_trial_promo)

Dom (#litres_trial_promo)

Crys (#litres_trial_promo)

Durdil (#litres_trial_promo)

Dom (#litres_trial_promo)

The Blessed One (#litres_trial_promo)

Galtas (#litres_trial_promo)

Gilda (#litres_trial_promo)

Rillirin (#litres_trial_promo)

Durdil (#litres_trial_promo)

Corvus (#litres_trial_promo)

Gilda (#litres_trial_promo)

Dom (#litres_trial_promo)

Galtas (#litres_trial_promo)

Crys (#litres_trial_promo)

Dom (#litres_trial_promo)

Crys (#litres_trial_promo)

Mace (#litres_trial_promo)

Durdil (#litres_trial_promo)

Mace (#litres_trial_promo)

Tara (#litres_trial_promo)

Rillirin (#litres_trial_promo)

Mace (#litres_trial_promo)

Dom (#litres_trial_promo)

Crys (#litres_trial_promo)

Rillirin (#litres_trial_promo)

Mace (#litres_trial_promo)

Tara (#litres_trial_promo)

Durdil (#litres_trial_promo)

Crys (#litres_trial_promo)

Rillirin (#litres_trial_promo)

Corvus (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue: Dom (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

RILLIRIN (#ulink_ea581031-be21-557c-a0c6-6a3d94eacfb3)

Eleventh moon, year 994 since the Exile of the Red Gods

Cave-temple, Eagle Height, Gilgoras Mountains

Rillirin stood at the back with the other slaves, all huddled in a tight knot like a withered fist. Word had been sent days before, summoning all the Mireces’ war chiefs from the villages along the Sky Path, drawing them to the capital to hear the Red Gods’ Blessed One. Whatever They had told her, it was important enough to bring the war chiefs to Eagle Height as winter set in.

Rillirin glanced towards the Blessed One with an involuntary curl of the lip, and then lowered her head fast. The high priestess of the Dark Lady and Gosfath, God of Blood, spiritual leader of the Mireces, was a remote figure, lit and then hidden by the guttering torches, her blue robe dark as smoke in the gloom, face as closed and beautiful as Mount Gil, rearing harsh and impassable above Eagle Height.

The altar was stained black and the temple reeked of old blood. Most of the Blessed One’s sermons ended with sacrifice, with a slave writhing on the altar stone. Rillirin shrank in on herself, staring at the floor between her boots. She had no desire to be that slave.

‘Come first moon we will enter the nine hundred and ninety-fifth year of our exile,’ the Blessed One said, her voice hard as she paced like a mountain cat before the congregation. King Liris stood at the front among his war chiefs, but she pitched her voice to the back of the temple so it bounced among the stalagtites hanging like stone spears above their heads. All would hear her this night.

‘Almost a millennium since we and our mighty gods were cast from the land of Gilgoras with its warm and bountiful countries to scratch a living up here in the ice and rock. Driven from Rilpor, harried from Listre, exiled from Krike.’ Cold eyes swept the warriors and war chiefs thronging at her feet as she listed the countries where the Red Gods had once held sway. ‘And what have you accomplished in all those years?’ Her voice cracked like a whip and the men flinched, hunching lower beneath wrath as sudden as a late spring storm.

‘Nothing,’ the Blessed One spat. ‘Petty raids, stolen livestock, stolen wheat. A few Wolves dead. Pathetic.’ Her teeth clicked together as she bit off the word. She raised her left hand and extended her index finger. It commanded a rustle of fear from Mireces and slave alike as she let it point first here, then there. She didn’t look where she gestured, as though it wasn’t attached to her, or as though it was driven by a will other than hers, a will divine.

The choosing finger. The death finger. How many times had Rillirin felt the brush of its sentience across her nerve endings, wondering if this, now, was the time of her death? It suddenly stilled, its tip pointing straight at her, and Rillirin’s vision contracted to its point and her breath caught in her throat. Stomach cramping, eyes watering, she forced herself to look past the finger into the Blessed One’s eyes, and saw the calculation there.

She wouldn’t dare. Liris would never allow it. Would he?

The finger moved on.

‘You disagree?’ the Blessed One demanded when Liris dared to look up. Challenge heated her eyes, tilted her chin up, and the Mireces king met her gaze for less than a second. ‘No, you would not. You cannot. Each year you swear your oaths to the Red Gods, sanctified in your own blood, promising Them glory and a return to the warm plains, swearing you will restore Them to Their rightful dominion over all the souls within Gilgoras. And each year you fail.’

Her voice dropped to a silky whisper. ‘And so the gods have chosen the instrument of Their return.’

Liris was sweating. ‘You have seen this?’ he managed.

‘The Dark Lady Herself has told me,’ the Blessed One confirmed, her smile small and cruel. ‘There are those in Rilpor who are of more use to Her than any man here.’ She swept her finger across the crowd and they leant away from it. ‘There are those in Rilpor who hate and fear us, and yet who will do more for our cause than you.’

She accompanied the words with the finger, and for a second it pointed at Liris’s heart. The threat was clear and men slid away from him as though he were plagued. The sacred blue of their shirts was dull under the temple’s torches, blackening with fear-sweat at their proximity to death.

Rillirin felt a bubble of shock and then sickening fear. What would happen to her when Liris’s tenuous protection was gone? I’ll be unclaimed. She hated Liris, despised him with everything in her, yet he kept her safe from the depradations of the other men. Kept her for himself.

Liris threw back his shoulders and drew himself up to meet his fate, but then the finger jerked on amid a growing babble of noise. Rillirin breathed out, relieved and disgusted with that relief in equal measure.

The Blessed One hissed and drew all eyes back to her. ‘Our gods are trapped on the borders of Gilgoras like us, but They weave Their holy work inside its bounds nonetheless. With the help of my high priest, Gull, who lies hidden in the very heart of Rilpor, They draw one to Them who can finally see Their desires fulfilled.’ She bared her teeth. ‘Know this now, and rejoice in the knowing. The gods’ plans are revealed to me, and soon enough to you. Begin your preparations and make them good. Come the spring, we do not raid. Come spring, we conquer. And by midsummer, we will have victory not only over Rilpor but over their so-called Gods of Light as well.’

She raised both arms to the temple roof. ‘The veil can only be broken by blood: lakes and rivers of blood. We will shed it all if it will return our gods to Gilgoras. Our blood and heathen blood, spilt together, mixed together, to sanctify the ground and make it worthy for Their holy presence. We shall have victory, you and I,’ she shouted, ‘and the Red Gods, the true gods, will be well pleased.’

Rillirin pushed forward, trying to see Liris’s face, to see whether he knew as much as the Blessed One appeared to. They’re going to war against Rilpor? They’ll be slaughtered. The shadows in the trees will do for them, and the West Rank. Her mouth moved in something that might have been a smile if she could remember what one felt like.

Amid the cheers and cries of exaltation to the gods, the Blessed One dropped her arms to her sides, before the left rose once more, dragged by that weaving, ever-moving finger.

‘You.’ It was a single word whispered amid the tumult, but the silence fell faster than a stone. All eyes looked where she pointed, not to the slaves, but to the warriors and women of the Mireces, born and raised within the gods’ bloody embrace. ‘The Dark Lady demands Mireces blood in return for Mireces failure. She demands a promise that we will stand with our new ally to the gods’ glory, that we will bleed and die for Their return. A promise that we – that you – will not fail Them again. The gods choose you. Come and meet them.’

Liris’s queen rose to her feet, her lips pulled back. She threaded her way through the crowd with small, stumbling steps, breath echoing harsh in the orange light. Rillirin watched her, her guts swamping with relief. You poor bitch, she thought, and then tried to burn out the pity with hate. Rillirin rubbed her stinging eyes, swallowing nausea. Bana was a Mireces and she deserved to die. They all did. Every one of them, starting with Liris and with the Blessed One next. She was pleased Bana was being sacrificed. Pleased.

‘Your will, Blessed One,’ Liris said as the mother of his children reached the altar and looked back at him, for a kind word or a demand for her release, perhaps. Her face rippled when she received neither. The Blessed One smiled and, tearing the woman’s dress down the front, bent her back over the altar stone; the queen’s soft, wrinkled belly undulated as she panted.

‘My feet are on the Path,’ Bana shrieked, and the Blessed One’s knife flashed gold as it drove into her stomach.

Gods take your soul to Their care, Rillirin thought despite herself, her fists clenched at the screams. Yet she didn’t know to which gods she prayed any more, those of Blood or of Light. None of Them did anything to help her. She looked away as the Blessed One dragged the knife sideways and opened Bana’s belly, her other hand pressing on her chest to keep her still. Bana’s screams echoed and re-echoed and the Mireces fell to their knees in adulation.

The slaves knelt too, and one pulled Rillirin down to the stone. ‘Are you stupid?’ he hissed. ‘Kneel or die.’ Rillirin knelt.

Liris’s face was stony and closed as Bana shrieked out the last moments of her life. He stood as soon as it was done and the Blessed One had completed the prayer of thanks. The blood was still running and his war chiefs still knelt in prayer when he shouldered his way through his warriors. Before Rillirin could get away, he reached out a sweaty paw and grabbed her by the hair.

No no no no no no.

‘Come on, fox-bitch,’ he snarled in her ear, hauling her towards the exit. The slaves melted from their path like snow in spring, eyes blank or calculating – her perceived power was something many of them coveted – and the temple rang with Liris’s rasping, angry breath, the pat-pat-pat of blood, Rillirin’s muffled whimpers.

Rillirin stumbled up the slick stone steps from the temple, bouncing from the walls in Liris’s wake, and when they reached the top Liris shook her until she squealed. He cuffed her face and dragged her through the longhouse and into the king’s room, threw her at the bed and dropped the bar across the door.

‘Lord, you must not,’ Rillirin pleaded, on her knees, one hand pressed to her stinging scalp. ‘The Blessed One said that you should not touch me, not for three more days. I’m still sick.’

Liris flung his bearskin on to the floor and brayed a laugh. ‘You’ve had a pennyroyal tea to flush my seed from your belly because you don’t deserve a child of mine. You’re a slave, not a consort, and you’ll do as you’re told.’

‘Honoured, please,’ Rillirin tried as he advanced. She scrabbled away on hands and knees, the weakness a blanket slowing her reactions. He can’t. Bana’s still warm, he couldn’t want – Liris pulled her to her feet by one arm and dragged up her skirts, blunt fingers hard against her thigh. The stench of his breath caught at the back of her throat. It was clear that he did want.

Rillirin squirmed and thrashed, but he was too big, too strong. Always had been. ‘No,’ she screamed in his face. ‘No.’

Liris jolted back in surprise, piggy eyes narrow. His breath sucked in on a whoop of outrage, and Rillirin clenched her jaw and screwed up her eyes. Stupid. Stupid!

She was convinced the punch had broken her jaw, and the impact with the stone floor sent shards of white pain through her shoulder. Black stars danced in her vision. Blood flooded her mouth and her shoulder was numb with sick, hot agony.

Liris picked her up and slammed her into the wall, one hand around her lower jaw, grinding the back of her head into the wood. ‘Bitch,’ he breathed. ‘While I normally enjoy our little games, I’m not in the mood for your spite tonight. You do not answer me back, you hear? You. Do. Not. Answer. Back.’ Each word punctuated by a crack of her skull on the wall. ‘You live because I will it, and you will die when I decide. Tonight, maybe, if you don’t please me. Or on the altar to ensure our success in the war to come. Or after I give you to the war chiefs for sport. When I choose, understand? You belong to me. Now keep your fucking tongue behind your teeth and unclench those thighs. I’ve a need.’

The tears were coming and Rillirin willed them not to fall, glaring her soul-eating hatred at him instead. A wild, suicidal courage flooded her. ‘Fuck you,’ she wheezed.

Liris’s mouth popped open and then he leant back to laugh, huge wobbling gasps of mirth. ‘I’ll break you, fox-bitch,’ he promised and his free hand dragged at her skirts again.

Rillirin worked her fingers around the knife hilt digging into her side, slid it out of Liris’s belt even as he forced her legs apart, and jammed it in the side of his neck. He looked at her in disbelief, hands falling slack, and Rillirin pumped her arm, the blade chewing through the fatty flesh and widening the hole in his neck.

Blood sprayed over her hand, her arm, her face and neck and chest, great warm lapping waves of it washing into the room until his knees buckled and he went down. She went with him, knife stabbing again and again, long past need, long past his last bubbling breath, until his face and neck and torso were a mass of gore and torn flesh.

Red with blood, red as vengeance, Rillirin spat on his corpse and waited for dark.

CORVUS (#ulink_4bc8e1be-b95a-5aea-98d7-28cd9292d51d)

Eleventh moon, year 994 since the Exile of the Red Gods

Longhouse, Eagle Height, Gilgoras Mountains

Corvus, war chief of Crow Crag, paced below the dais. Lady Lanta, the Blessed One and the Voice of the Gods, sat in regal splendour beside the empty throne. The other war chiefs fidgeted on their stools and benches.

The Blessed One would not reveal more of the gods’ plan until the king was present, and the king was not one for stirring himself unnecessarily. Still, the sun was high even this late in the year and Corvus would bet Lanta was as impatient as he. A full-scale invasion with only months to plan; an ally within Rilpor they could use to their advantage. The idea warmed his belly. Invasion. Conquest. A chance for glory such as there’d never been, for Corvus to put his name, and Crow Crag’s, on the lips of every Mireces and Rilporian alive. And yet Liris lounged in his stinking pit like an animal.

The other end of the longhouse was crowded with warriors, complaining bitterly about the storm that had blown in. Slaves hunched and scurried to their chores, and Corvus’s lip curled in disgust as an old man tripped and spilt his tray of bowls across the floor. Dogs lunged for the scraps, fighting around the man’s feet and legs, scrabbling through the ragged furs piled up to keep off the chill.

Corvus kept pacing, fists clenched behind his back and face schooled to patience. He glanced at Lanta, sitting remote and inaccessible as the very mountains, and fought the urge to shake the information out of her, to slap it from her. The Blessed One is not as other women, he reminded himself. She’ll wind my guts out on a stick if I touch her. Despite his own warning, he glanced at her with a mixture of irritation and hunger. She didn’t deign to meet his eyes.

‘The gods wait for no man. Not even a king.’ Lanta’s voice was honey and poison and Corvus noted how the other war chiefs froze at its sound. ‘There is much to discuss.’

Edwin, Liris’s second, jumped up. ‘I’ll go, Blessed One,’ he said and scuttled down the longhouse to the king’s quarters at the end, his relief palpable. They all wanted to settle this and get out from under the Blessed One’s eye. Bana’s death hung in the air like the scent of blood.

Corvus had completed two more circuits below the dais before the yelling began. By the time the others had struggled out of their chairs, he was at Lanta’s side with drawn sword, ready to defend her.

‘The king,’ Edwin screeched as he shoved back into the longhouse. His hands were bloody. ‘The king has been murdered. Liris is dead!’

For a moment Lanta’s calm cracked, and Corvus would’ve missed it if he hadn’t been looking at her instead of Edwin squawking like a chicken on the block. But then the mask was firmly back in place. Corvus’s sword tip drooped on to the dais as Edwin’s words sank in. Corvus opened his mouth, closed it again, and looked at the men gathered like a gaggle of frightened children below him, backs to the dais, eyes on the far door. They were bursting with questions for Edwin, but none seemed keen to approach him.

Lanta picked up her skirts and strode the length of the longhouse, bursting through the door to the king’s quarters and slamming it behind her before anyone could see. Edwin stood outside it, staring at his hands in disbelief.

Liris is dead and the Blessed One is with the body. Eagle Height has no king. Eagle Height is vulnerable.

‘Gosfath, God of Blood, Dark Lady of death, I thank you,’ Corvus whispered. ‘I swear to be worthy of this chance you have given me. All I do is in your honour.’ One of the chiefs turned at the sound of his voice, his mouth an O of curiosity.

‘My feet are on the Path,’ Corvus said, completing the prayer. He took three steps forward, raised his sword, and started killing. The king was dead. Long live the king.

CRYS (#ulink_64817ebd-ce01-5b47-8562-5b565c9383fc)

Eleventh moon, seventeenth year of the reign of King Rastoth

North Harbour docks, Rilporin, Wheat Lands

‘I will have you know I am the most trustworthy man in Rilporin. No, not just in the capital, in all of Rilpor. And these cards are brand new, picked up from a shop in the merchants’ quarter a mere hour ago. Examine them, gentlemen, hold them, look closely. Not marked, not raised, even colouring, even weight. Now, shall we play? A flagon, wench.’

Crys clicked his fingers at the pretty girl hovering in his eyeline and plastered a wide grin across his face. He’d been watching this pair for the last hour, and now they were just drunk enough to be clay in his hands.

The men watched suspiciously as he cut and shuffled the cards, fingers blurring, and dealt them with a neat flick of the wrist only slightly marred by the fact the cards stuck in or skittered over the spilt beer. They’d be ruined, but he’d just buy more. What was the point in gambling if he didn’t spend the money he won? He slapped the remains of the deck into the middle of the table, scooped up his cards, examined them, swallowed ale to hide his glee and breathed thanks to the Fox God, the Trickster, patron of gamblers, thieves and soldiers. He was all three, on and off.

The faces of his fellow players were so wooden Crys could have carved his name into them, but the man to his left was tapping his foot on the floor. Man to his right? No obvious tell. No, wait, spinning the brass ring on his thumb. Excellent, he’d dealt the cards right.

‘Five, no, six knights.’ Crys opened the betting and tinkled the coppers next to the deck. He smiled and drank.

‘Six from me,’ Foot-tapper said.

Ring-spinner matched him. ‘And from me.’

Crys made a show of looking at his cards again, squinting at the table and his opponents. ‘Um, two more.’ He added to the pile with a show of bravado that sucked them right in. He leant back in his chair and scratched the stubble on his cheek, fingernails rasping. He’d better shave before tomorrow’s meeting. He’d better win enough to buy a razor.

‘So, you fresh in from a Rank, Captain? The West, perhaps?’ Foot-tapper asked.

Crys hid a grimace behind his cup: always the West. City-folk were obsessed with the West, with tales of Mireces and Watchers and border skirmishes. The crazy Wolves – civilians no less – were Watchers who took up arms to guard the foothills from Raiders and protect the worshippers of the Gods of Light from the depradations of the bloody Red Gods.

Crys didn’t reckon half the stories were true, and those that had been once were embellished with every telling until the Watchers and Wolves were more myth than men and every soldier of the West Rank was a hero. They’re soldiers watching a line on a map for two years, interrupted with brief bouts of fighting against a couple of hundred men. Yeah. Heroes.

Crys snorted. ‘The North, actually,’ he said, swallowing his frustration. ‘Finished my rotation there. Palace Rank next.’

‘Palace, eh? Two comfy years for you, then, eh? Must be a relief. But I’m Poe and this is Jud.’

Crys nodded at them both. ‘Captain Crys Tailorson.’

‘Captain of the Palace Rank? I’m sure no one deserves it more. I imagine King Rastoth is in the very safest of hands now you’re here, Captain.’ Poe watched him closely, looking for tells. Crys made a show of thumbing one card repeatedly. Deserved? He’d be bored out of his mind for two years, more like. Still, there were likely a lot more idiots prepared to lose their money here than in the North Rank and its surrounding towns. Few men had dared gamble with him towards the end of that rotation. Not to mention Rilporin bred prettier lasses.

Jud brayed a laugh. ‘You hear about those Watchers? Ever met one? I hear the men all stick each other up there. Ever see that?’

‘I haven’t served in the West Rank yet,’ Crys said, uncomfortable. It was all anyone could talk about of late, the rumours coming from the west; General Mace Koridam, son of Durdil Koridam, the Commander of the Ranks, increasing patrols and stockpiling weapons and food. ‘And that sort of business is against the king’s laws,’ he added belatedly.

‘Strange people, those Watchers. Civilians, ain’t they? Take it upon themselves to patrol the border. Why? They don’t get paid to do it, do they? Why risk your life when the West’s there to protect you?’ Poe asked. He seemed in no hurry to get on with the game. ‘I mean, West’s best, or so they say,’ he added with an unexpected touch of malice.

‘I know why,’ Jud said, laughing again. ‘It’s ’cause their women are all so fucking ugly. That’s why they fight, and that’s why they stick each other. Nothing else to do.’

‘Wolves fight, Watchers don’t,’ Crys explained. Jud frowned. ‘They’re all from Watchtown, it’s just they call their warrior caste Wolves and the Wolves have little or no regard for the laws of Rilpor. As you said, they take it upon themselves to fight. And there are Wolf women as well, I hear,’ Crys said as he flicked his cards again, letting the happy drunk mask slip for a moment. West is best? Maybe you don’t need all that coin weighing you down, Poe. ‘Fierce and just as good as the men,’ he added.

‘She-bears. ’Bout as pretty too, they say.’ Jud emptied his cup, helping himself to more as Crys eyed him. ‘They’re all touched with madness, those Watchers. Fighting for no pay, letting their women fight. Women! Can you imagine? What’d you do if you had to fight a woman, Captain?’

Crys licked his teeth. ‘Try not to lose,’ he said. ‘It’d look awful on my record.’

Poe laughed and slapped the table, but Jud had lost his sense of humour all of a sudden. ‘Look at his eyes,’ he hissed, waggling a finger in Crys’s direction and heaving on Poe’s arm.

Fuck’s sake, and it had all been going so well. Crys put his palms on the sticky table and leant forward, opening his eyes wide and staring them down in turn. ‘One blue, one brown, yes. Very observant.’

He sat back and folded his arms, the soggy cards tucked carefully into his armpit where they couldn’t be seen. Old habits. ‘But I had thought you wealthy, sophisticated merchants of this city and as such not susceptible to the superstitions of countryside fools. Perhaps I was mistaken. Perhaps I’ve been wasting my time here tonight.’

Jud and Poe eyed each other, clearly uncomfortable. They were nothing of the sort and all of them knew it.

Poe’s foot tapped and he managed a nonchalant grin. ‘But of course. A topic of conversation only. You must hear it a lot in the Ranks, no?’ He drained his mug and ordered a flagon. About fucking time, too.

Crys forced a mollified note into his voice, at odds with the irritation mention of his eyes always engendered. Splitsoul, cursed, unlucky. He knew them all. ‘I do, sir. Men either stick to me like bindweed thinking I’m lucky, or they refuse to be anywhere near me. It’s a real pain in the arse, has dogged me all my life.’ Poe tutted in sympathy. ‘Still, what can a man do?’

‘Cut one of them out?’ Jud honked and laughed into his cup, spraying Crys with froth. Crys unfolded his arms and watched him.

Poe thumped him in the arm. ‘Forgive my friend, Captain. Too much ale. He’s got a sword, you fucking idiot,’ he hissed to Jud, who was clutching his arm and whining.

Crys drew out the moment, but decided against it. ‘Come on then, let’s play,’ he said and Poe slumped in relief, thumping Jud again for good measure.

‘You heard the good captain. Play.’

‘Two,’ Jud said sulkily.

Excellent. And about bloody time. ‘I call,’ Crys said and plopped his cards face up, watching the others reveal. He’d lost by a dozen, as expected. Poe had the winner and scooped coins and ale to his side of the table, baring yellow snaggle-teeth in something that might have been a smile. On a bear.

Crys groaned and drank; he topped up the cups of his companions with fatalistic good cheer. Poe collected the cards and Crys watched him shuffle: not even an attempt to separate the already played cards through the deck. He dealt and Crys knew he’d have a poor hand. No matter, he wasn’t ready to win just yet.

Gods, that meal was heavy, he thought as he made his first bet, but it was doing its job of soaking up the ale. Jud was red in the face and giggling, superstitions forgotten against the prospect of winning Crys’s money. He’d be the first to get sloppy and Crys and Poe could clean him out in a few hands. But then they’d need another third. No, better to bide a while longer and then take them both for a little too much instead of everything. Crys had no need of an enemy on his first day in Rilporin, and some men preferred to blame the man instead of their luck when it came to cards.

Plan decided, Crys sucked down some more ale and proceeded to lose another three hands.

Crys had found a lucky streak from somewhere. Strange, that, how his fortune had changed so suddenly. He’d won back most of what he’d lost but was still some way behind the others. Still, it was all running smooth—

‘I’ve been watching you. You’re a cheat.’

Crys lurched up from his chair and fumbled for his sword as Poe and Jud gawped, faces twisting with drunken outrage. The light fell on the speaker and Crys gasped, released the hilt and dropped to one knee. ‘Sire. Forgive me, Your Highness. You startled me and I – I simply reacted. I beg your pardon.’

Poe and Jud grabbed their coins and fled, not looking back, leaving Crys to the mercy of the Crown and seeming glad about it.

‘Shut up, stand up and pour me a drink.’

‘Yes, Your Highness.’

‘Sire or milord will do, soldier.’ Crys straightened and Prince Rivil took the proffered mug and sipped, made a face and sipped again. ‘Awful. I note you haven’t denied my accusation.’

Crys’s knee buckled again but he hoisted himself back up. ‘Your High— Milord may say and think anything he wishes, Sire,’ he said in a rush, staring anywhere but into Rivil’s face and so looking at his crotch instead. He blushed, straightened and snapped into parade rest, staring over the prince’s left shoulder and through the man behind him, one-eyed, well-dressed, a lord if Crys was any judge.

‘Oh, for shit’s sake, man, stop that. You think I’d be in a dockside tavern if I wanted pomp and ceremony? Sit the fuck down and have a drink. I’m here for relaxation, not to have my arse kissed.’

‘I – yes, Your … Sire.’

Rivil folded long legs under the small table and leant forward, oblivious to the ale staining the elbows of his velvet coat. ‘This is Galtas Morellis, Lord of Silent Water,’ he said, jerking a thumb at the man seating himself beside him.

Crys’s head swam. Galtas, Rivil’s drinking companion and personal bodyguard. Crys was in it up to his neck and it didn’t smell sweet.

‘Teach me your version of cheating at cards,’ Rivil said abruptly. ‘I’m not familiar with it.’

Oh, holy fuck. A bed and a razor, that’s all he’d wanted. All right, maybe a woman, but was that so much to ask when you’d been stationed in the North Rank for the last two years, negotiating border treaties?

Crys swallowed ale, wetting his throat, giving himself time to think, not that he could see a way out. ‘It would be an honour, Sire. Would you care to use my cards?’

Crys’s stack of coins was dwindling fast. At this rate he’d be sleeping in the gutter and shaving himself with his sword come morning. Or just using it to slit his own throat; the Commander didn’t listen to excuses, even ones about meeting a prince in a grimy tavern.

‘Oi, rich man. You’re fuckin’ cheatin’. I been watching you, you lanky bastard. You’re doing our brave soldier out of his hard-earned coin. He risks his life on those wild borders and comes here for a bit of ease and rest, and you’re fuckin’ doin’ him out of his money like you don’t have enough of it already? Fuckin’ nobility.’

Crys was suddenly and entirely sober. Galtas had swivelled in his chair and then risen to his feet. Rivil remained seated, his back to the speaker and his cool gaze resting on Crys. The message was clear: get off your arse and help, Crys Tailorson. Crys got off his arse.

‘Sir, I assure you nothing untoward is occurring here. I am merely experiencing bad luck with the cards. It happens – a lesson from the Fox God. Your concern is touching—’

‘Never fear, soldier, we’ll have at him for you. Fuckin’ lords comin’ in here and screwin’ over decent hard-workin’ folk. Honestly, you’re doin’ us a favour if you let us have ’im.’

‘Really, I don’t—’ Crys began into the heavy silence of dozens of men readying for a brawl.

The man was already swinging at Rivil’s unprotected head and Crys could do nothing but bite off the words and make a desperate lunge over the table. Galtas caught the attacker’s wrist, twisted it up and into an elbow lock, and threw him back into the press. He drew his sword, useless in the crowd but an effective deterrent to unarmed men.

‘City guard’s comin’. Scarper,’ a voice called before anyone had a chance to react. Rivil’s eyes snapped to Crys. The aggressors melted away and the rest of the patrons settled down, buzzing with conversation. Many slipped out, not eager to meet the Watch. Crys sat back down and emptied his mug.

Galtas remained on his feet, scanning the room for long moments, and then sat. Rivil jerked his head at Crys. ‘You did that? Those words? How?’

‘A knack,’ Crys said. ‘I can make my voice come from somewhere else.’

‘Sounds like witchcraft. And with eyes like that, I’m not surprised,’ Rivil teased. Galtas frowned, a dagger appearing in his hand.

‘No. Just a knack, like I said.’ Crys had both hands palm down on the table, as unthreatening as he could make himself. Rivil scraped all of his winnings, and Galtas’s, over to Crys’s side of the table.

‘My thanks,’ Rivil said, ‘but why bother? I’m not exactly popular with the Ranks. Why not let that man kick the shit out of me?’

‘You are my prince, Sire,’ Crys said, dropping the coins into his pouch, ‘even if you are a better cheat than me. No one kicks the shit out of the prince while I’m with him.’

‘I’m glad to hear it. Come and find me when you’re off-duty tomorrow. I might have a use for you.’

DURDIL (#ulink_aa986597-fb6c-5f68-bae6-9d88f8964a73)

Eleventh moon, seventeenth year of the reign of King Rastoth

The palace, Rilporin, Wheat Lands

‘Where is His Majesty?’ Durdil asked. The throne room was empty but for guards, the audience chamber vacant too.

‘The queen’s wing, Commander Koridam,’ Questrel Chamberlain said with an oily smile and the corners of Durdil’s mouth turned down. Third time this month.

Durdil’s breath steamed as he ducked out of the throne room and into a courtyard and took a shortcut through the servants’ passages. Winter was coming early this year, and the preparations for Yule were increasing apace.

Servants flattened themselves against the rough stone walls as he passed, ducking their heads respectfully. He nodded at each in turn. Durdil knew every servant in the palace; it made it that much easier to identify outsiders, potential threats to his king.

A guard stood in silence outside the queen’s chamber. Durdil slowed. He straightened his uniform and scraped his fingernails over the iron-grey stubble on his head.

‘Lieutenant Weaverson, is the king inside?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Did he speak to you?’

Weaverson was impassive as only a guard can be. ‘Not to me, sir. He was conversing with the queen.’

Durdil paused, chewing the inside of his cheek. Nicely phrased, no hint of mockery. ‘Thank you, Lieutenant. As you were.’

‘Sir,’ Weaverson said and thumped the butt of his pike into the carpet.

Durdil moved past him and pushed open the door to the queen’s private chambers. He hesitated on the threshold, bracing himself, and then stepped inside, closing the door behind him. Rastoth was in the queen’s bedroom, staring at the empty bed in confusion.

‘Your Majesty, you shouldn’t be in here,’ Durdil said quietly, and Rastoth looked over his shoulder, his eyes wide and watery. Durdil was struck by his gauntness. Where had that muscle and fat, that ruddy good humour, gone? This man was a shadow of himself.

‘Where is Marisa, Durdil? Where is my queen?’ Rastoth asked, his voice plaintive. ‘I was just talking with her. She was right here.’ He gestured vaguely and creases appeared between his brows. ‘But that’s not right, is it?’ he whispered. His fingers smoothed the coverlet over and over, the material thin and cold in the freezing room. No fire burning, no tapestries on the walls any more. No rugs.

Durdil walked towards him. ‘No, Sire, it’s not right,’ he said, his voice low. ‘Marisa’s gone, my old friend. Your queen’s dead. Almost a year now.’

Rastoth mewed like a seagull from deep in his chest. He collapsed on to the bed and hid his face in palsied hands too weak to support the rings on each finger. ‘No, that can’t be. That can’t be.’

He straightened suddenly, eyes bright with pain and coherence. ‘Murdered. Disfigured. Defiled here in this very room,’ he said, his voice harsh and broken and filling with rage. ‘My queen. My wife. And her killers still at large. Are they not, Commander? Despite your promises. Despite your every promise?’ He spat the words.

Durdil inhaled through flared nostrils and knelt before Rastoth, his knee protesting at the cold stone. No rugs because they’d been covered in blood. No tapestries because they’d been torn from the walls, covering the queen as her killers hacked through the material into her body. As though even the murderers couldn’t bear to look on what they’d done before they killed her, the destruction they’d wrought on her body and face.

No shattered door bolt, remember? Marisa opened the door to her murderers, let them in. Her guards dead on the threshold, dead facing into the room, not out of it. It ran like a litany through Durdil’s head. The queen knew her killers. Her guards knew them, hadn’t stopped them from entering, only engaged them when they were on their way out, the deed done.

Durdil swallowed the thoughts. ‘Yes, Sire. I have failed to find the killers of your queen. I have failed you.’ He chanced a look up. ‘But I have not stopped looking, my liege. I will never stop looking. I will find them. And we will bring them to justice.’

But Rastoth wasn’t listening. ‘Why, there she is. My little sparrow, hiding behind her loom.’ He scrambled to his feet, tripping on the edge of his cloak and his knee catching Durdil’s shoulder. He wobbled past and Durdil heaved himself to his feet, each of his fifty-six years an anvil on his back.

Rastoth had ducked behind the loom by the window. ‘Where are you hiding now, my pretty?’ he called. ‘Marisa? Marisa, my love.’

Durdil winced. ‘Your Majesty, we must return to your chambers. The hour grows late. Let us leave the queen to her rest. It has been a long day.’

Rastoth straightened and stared at Durdil through the strings of the loom, Marisa’s half-completed tapestry collecting dust on its frame. He’d tried this before and Rastoth had flown into a fury. Durdil had no idea which way it would play this time.

‘You’re right, of course, Durdil. She’s tired. I’m tired.’ He glanced fondly at the bed. ‘Sleep well, my beauty,’ he said, and tiptoed to the door, hissing at Durdil to do the same when the heels of his boots rang on the flagstones.

Durdil grimaced and rose on to his toes and together they crept to the door of the empty room and squeezed through it. Weaverson didn’t so much as glance in their direction, but Durdil stopped in surprise when he saw Prince Rivil.

‘We must let her rest, Commander,’ Rastoth murmured as he pulled shut the door. ‘Perhaps tomorrow my wife will be well enough to be seen by the court again, do you think?’

Rivil stepped forward and Durdil relinquished his place at the king’s side. ‘I’m sure Mother will be well again soon,’ he said, taking Rastoth’s arm. ‘For now it’s you I’m worried about. You shouldn’t be wandering around in the cold at this time of night.’

Durdil glanced at Weaverson and then followed his king and prince, listening to Rivil’s careful voice, watching his hand firm on his father’s elbow. ‘Come, Father, you should be abed,’ Rivil said with a nod to Durdil. Durdil nodded back and forced a smile for the prince.

Rastoth’s fits were getting worse and there was nothing Durdil could do about it. His friend and king was losing his grip on reality; he was slowly becoming a laughing-stock. Durdil wasn’t sure that even finding Marisa’s killers could end Rastoth’s illness now. Not that he had a single lead anyway. He knuckled his eyes hard and glanced again at Weaverson. Then he followed in the wake of his king.

DOM (#ulink_ca8bf4a3-d657-5435-9f99-50b3e870ae5a)

Eleventh moon, seventeenth year of the reign of King Rastoth

Watcher village, Wolf Lands, Rilporian border

‘I’ve got you this time, you old bugger,’ Dom muttered. He was knee-deep in a stream that began high up in the Gilgoras Mountains and widened into the Gil, mightiest river of Rilpor. His bare feet were numb and the air smelt of snow, but the pike was cornered. Dom felt forward with his toes, the fishing spear up by his jaw.

The pike flicked its tail and Dom grinned as he edged closer. He’d laid the net behind him just in case, but this was becoming personal. A flicker again, and Dom lunged, stabbing down into the gloom.

The pike flashed past him, twisting out of the spear’s path, and Dom spun, slipped on a rock and went to one knee. He gasped at the cold but the pike wasn’t in the net, so he lunged back on to his feet and examined the pool.

‘Come out, come out, little fishy,’ he sang, ‘I want you in my belly.’

Instead the sun came out and reflected off the water, blinding him, and Dom blinked. The brightness stayed in his vision, like an ember bursting into life, racing into a conflagration.

Dom groaned as the image of fire grew. He dropped the spear and splashed for the bank, panting. ‘No,’ he grunted through a thick tongue, ‘no no no,’ but it was too late. He was a stride away from land when the knowing came, and he hurled himself desperately towards dry ground before the images took him.

He felt his chest hit the mud as his surroundings vanished and then all that was left was the message from the Gods of Light, filling his mind with fire and pain and truth.

‘You really are a shit fisherman, Templeson,’ Sarilla laughed when he staggered back into camp at dusk. She pointed her bow at him. ‘Why don’t you just – ah, fuck. Lim! Lim, it’s Dom.’

Sarilla slung Dom’s arm over her shoulders and took his weight; she led him to the nearest fire and sat him so close the heat stung his face. He turned away, unwilling to look into the flames, and Sarilla chafed his hands between hers, and then dragged his jerkin off and threw her coat around his shoulders.

Lim arrived at a run and Dom held up a hand before he could speak. ‘Just get me warm first,’ he croaked. ‘I’ve been belly up in that fucking stream all afternoon.’ It might not be what I think it is. Fox God, I hope it’s not what I think it is.

They stripped him, wrapped him in blankets and made him drink warm mead until the colour came back into his face and he finally stopped shivering. Feltith, their healer, pronounced him hale and an idiot. Dom didn’t have the energy or inclination to disagree. He couldn’t look at the fire, but he met the eyes of the others one by one.

‘I have to go to the scout camp, and I have to go alone.’ He waited out their protests, gaze turned inward as he fought to unravel the Dancer’s meaning. His hand gestured vaguely west. ‘It’s coming from the mountains. I have to fetch it. Fetch the key. Message. Herald?’

Dom’s face twitched and he spoke over Lim’s fresh complaints. ‘Don’t know. Not yet. It’s like – it’s like a storm’s brewing up there. There’ll be a warning before it breaks, but only if I can get to it in time.’ He grunted in frustration. ‘I don’t know. It doesn’t make sense. Midsummer.’

‘Midsummer? What about the message?’ Sarilla said.

‘That too. Shit, why is it so hard?’ Dom grunted, knuckling at the vicious pain behind his right eye. Sarilla slapped his hand away. ‘If the Dancer and the Fox God want me to know something, why don’t They just tell me?’

‘They are. We just don’t have the capacity to understand,’ Sarilla said, and for once her tone held no mockery. ‘They’re gods, Dom. You can’t expect Them to be like us.’

‘Sarilla’s right, the knowings rarely make sense at first,’ Lim soothed him. ‘But midsummer? We’re not even at Yule. We’ve got time, Dom. Don’t push it; it’ll come. There’s no immediate threat?’ he clarified.

‘It’s nearly a thousand years since the veil was cast,’ Dom said suddenly. He had no idea where the words came from, but years of knowings had taught him to relax and let his voice tell him what he didn’t yet understand. ‘Now it weakens. The Red Gods wax and the Light wanes. Blood rises. Find the herald; staunch the flow.’

Dom focused on the mud between his boots, loamy and rich, his chest heaving as though he’d run down a deer. He swallowed bile. The pain crescendoed and then settled to a steady agony that made his vision pulse with colours around the edges. This is it. I think it’s starting. After all these years, it’s coming.

I need more time.

Lim, Sarilla and Feltith were silent, waiting for more. Dom squeezed his hands into his armpits to hide their trembling. No point scaring them before he had to. Why not? I’m scared. I’m fucking terrified. But he was the calestar, for good or ill, and with the knowings came duty. Duty? Sacrifice, more like. My sacrifice. Duty, he told himself sternly, silencing the inner voice.

‘Everything’s in flux, but there’s always a threat,’ he said, finally answering Lim’s question. ‘I’m going up there tonight.’

Lim didn’t argue further. ‘Rest a while longer and I’ll pack provisions.’

‘I have to go alone,’ Dom insisted.

‘You can’t go alone,’ Sarilla said quietly. ‘If you have another knowing up there, in the Mireces’ own territory, you’ll be helpless. Even I don’t want you frozen to death or eaten by bears. Or taken by Mireces.’

Lim glanced at Sarilla. ‘Send a messenger to Watchtown and another to the West Rank. You know how much truth to tell to each. We don’t know what we’re preparing for yet, so let’s not panic.’ He pointed west, the way Dom had. ‘But nothing good has ever come out of those mountains. Be alert.’

THE BLESSED ONE (#ulink_0aa17d21-abef-5ae2-83f0-b12efb2fc122)

Eleventh moon, year 994 since the Exile of the Red Gods

Longhouse, Eagle Height, Gilgoras Mountains

Lanta dealt regularly in blood and death in her exaltation of the gods, but what had been done to Liris … it was messy, wild. A frenzied, senseless attack, lacking in control, lacking in style.

Edwin had done a headcount and reported one missing slave as well as the various men out on business for the king or Lanta herself; then he’d taken a war band and hounds out in pursuit of the killer. The room stank of blood and fear, a scent easy enough for the dogs to follow in the clear mountain air.

Lanta’s thoughts returned to her predicament. One missing slave was easy enough to replace. A killer easy enough to track down. One pliable king, however, would need careful consideration. Of the war chiefs, Mata would be—

She stopped halfway down the longhouse, trying to make sense of what she was seeing. ‘What is this?’

Corvus, seated on the throne, looked up from inspecting his boots. They were bloody, as were his hands. ‘This, Blessed One, is a succession. I thought our people should have the smoothest transition after Liris’s untimely death.’ Corvus spared her a brief smile and picked drying blood from beneath a thumbnail.

He hasn’t. He wouldn’t, not without my approval. Her eyes flicked to the corpses at the base of the dais. And yet he has. She replayed his words as she fought for serenity. ‘Our people?’ She arched a brow. ‘May I remind you, Corvus of Crow Crag, that not too many years ago you were taken as slave from Rilpor? You were Madoc of Dancer’s Lake then, born and raised a heathen. So these are my people, and I decide what is best for them.’

Corvus glared at her. ‘Am I not a good son of the Dark Lady? I pay my blood debts, I raid in Her name, I worship Her and Her Brother, Holy Gosfath, God of Blood. I am Mireces, dedicated in blood and fire, war chief of Crow Crag and now King of the Mireces. That is all of my lineage you need to know.’

So quickly he challenges me. So quickly he eliminates any who would oppose him. And of course, there is Rillirin, who Liris dragged to his chamber after Bana’s holy sacrifice. And Rillirin … interests me.

‘Such a hurried transition, Corvus,’ Lanta said in a low voice as she stalked through the silent audience, picking her way through the tangle of corpses below the dais. Slaves were wide-eyed with panic, huddled at the back of the longhouse like a flock of chickens before the wolf. ‘On whose authority do you claim the throne? I was not consulted.’

Corvus steepled his fingers before his lips. ‘My own. But you can consult the other war chiefs if you’d prefer. Not sure how much talk you’ll get out of them, though.’

Lanta paused in her stride and then continued, stately, predatory. So the challenge comes now, before his arse has even warmed the throne. Then let the gods decide.

‘As for authority, I claim it by right of conquest, as Liris did.’ Corvus had pitched his voice to reach the end of the longhouse, drawing warriors to him. They crowded at Lanta’s back.

‘I stand beside the throne, my voice is second to the—’ Lanta began as she stepped on to the dais. Corvus leapt from his seat and, firm but courteous, pushed her back down the wooden steps. Lanta wobbled, rigid and red with fury now, down on the floor with the rabble.

‘I didn’t invite you to approach,’ Corvus said, his voice pitched loud. ‘When I do, a seat will be made available for you behind me and I will ask for the Dark Lady’s’ – he stressed the honorific – ‘counsel as and when I need it.’

‘The Red Gods will not suffer me to be abused,’ Lanta screeched, her fury a lightning bolt from a clear sky. Insolent, arrogant child! He thinks stabbing men in the back gives him authority over the gods? Over me?

Men shrank away from her anger, but Corvus’s smile mocked. He returned to his throne before answering, stretching the moment long, forcing Lanta and the rest to wait.

‘Where is your obeisance, Blessed One?’

Lanta gaped, disbelief etched across her face. ‘What did you say?’ she whispered.

‘Liris was weak – you took advantage of that to seize more power than your station demanded. I’m restoring the balance. You may not have authorised a new king, but the Dark Lady did. So kneel. Or die. I don’t much care either way.’

‘I know the Lady’s will,’ Lanta shouted. ‘I am the Blessed One. She talks to me, not you.’ Her fists were clenched, face hot with outrage and anger. A challenge directed not just at her power, but that of the gods? I’ll see him writhing beneath my knife for this outrage.

Corvus spread his red hands. ‘Then you’ll know it was Her will that I defeated my rivals. If She didn’t want me on the throne, they would’ve killed me.’

There were murmurs and Lanta felt the shift in the room. He was right and everyone knew it; godsdamnit but she knew it. A change in tactic, then. ‘King Corvus,’ she said and he grinned, ‘now is not the time for a change in administration. Perhaps—’

‘Well, unless you can bring a man back from the dead, you’re fucked,’ he replied and there was muted laughter, quickly stilled.

Lanta bared her teeth. It had been years since anyone’d dared interrupt her. She remembered now how little she liked it. ‘I simply meant, perhaps our people would prefer a united front until you settle into your new role. There are many things I can advise on. If you would allow it?’

‘No.’

Lanta could feel her cheeks burning. The air fizzed between them as Corvus looked into her eyes, all cool detachment and deep amusement, daring her to look away.

She smiled. There were many ways to play this game and she had far more experience than he did. Still, he’d riled her. ‘Perhaps men will be sent to Crow Crag for your consort,’ she hissed, and heard the collective intake of breath. Had she really just threatened the king? Corvus flicked his fingers in dismissal, his face disinterested. As though she hadn’t even spoken. Lanta inhaled hard.

‘Perhaps you should focus on finding Liris’s killer instead,’ he said.

‘Oh, don’t you worry about that,’ she said. ‘They’ll be found and dragged before you for judgement. I wonder what sort of a king you’ll be then, when you have before you the one who really granted you the throne.’

Lanta was never reckless; the gods had too many plans and she was too important to all of them. Yet that easy smile, those infuriating blue eyes, made her desperate to hurt him, but instead of her barbs finding his flesh, everything she said simply glanced off him, as though he was wearing that ridiculous Rilporian plate armour.

‘Tread lightly, Blessed One,’ Corvus said, his voice low with menace. ‘You have no idea who you’re dealing with.’ He paused and smiled, friendly, open. ‘But I can show you, if you ever threaten me or mine again.’

Perhaps that had been over-hasty, she conceded as she stared at Corvus and his bloody hands, his bloody boots. His strawberry-blond hair was wild and sweaty from the fight, and she dropped her gaze from his to examine the bodies. Wounds in the back. She snorted faintly. He hadn’t even had the balls to do it properly.

But done it was. While she’d been examining the torn and bloody corpse of Liris in the room next door, she’d lost everything. The gods’ desires subordinated to the desires and whims of a man. No, she vowed into the silence of her skull, not during my lifetime. Not when I still have some power.

‘It is a comfort to hear you will not let Liris’s killer escape. By all means conduct your own investigation; I shall entreat the Dark Lady’s advice. Liris had taken a whore into his bedchamber before he was killed; she escaped during the confusion but I’ve already sent men after her. The chances are good she saw the killer and we can use her to identify the man,’ Lanta said, deliberately keeping Rillirin’s identity to herself. She needed every scrap of leverage she could find.

‘Why don’t you think it was the whore?’ Corvus asked.

Lanta laughed. ‘A slave and a whore? Impossible.’ She turned away. Even so,I’ll have that cunt on the altar stone one way or another, belly open to the sky and soul food for the gods.

‘Blessed One,’ Corvus said in a voice of honey, and she gritted her teeth and stopped. ‘You still haven’t made your obeisance.’

‘I kneel only to the gods,’ she grated over her shoulder, her eyes murderous slits.

Corvus tutted and shook his head. ‘Not true. I hear you regularly knelt to Liris, mouth open and no doubt eyes closed. Who’d want to see that, after all?’ He laughed and there was a ripple of shocked amusement through the hall, amusement at her expense.

Lanta could hear her teeth grinding and swallowed a roil of nausea. She stared at him in silence. The air grew thick with hate, but Corvus never lost that easy smile. She could level men with a glance but not, it appeared, this one. Not yet. So she curtseyed, low, deep, correct. What does it mean, after all? Nothing. It is as empty as his supposed kingship and soon to be as distant a memory.

In stunned silence, Lanta walked the length of the hall, proud and distant. She crooked a finger and her priest, Pask, held the door for her and then followed her through. It closed with a click and she sucked in a deep breath of mountain air. She had much to think about.

CRYS (#ulink_ee57ccb5-e9ef-5f10-84f9-f87612868fbe)

Eleventh moon, seventeenth year of the reign of King Rastoth

Commander’s quarters, the palace, Rilporin, Wheat Lands

‘So, Captain Tailorson, it appears you have led a varied and interesting career in the last two years with the North Rank. Any particular reason for that?’ Commander Durdil Koridam eyed him from behind his desk.

‘No, sir.’

‘Demoted to lieutenant for brawling with common soldiers, a month in the cells for smuggling a family over the border into Rilpor, promotion back to captain for outstanding gallantry under fire … Outstanding?’

‘Major Bedras found himself surrounded by the Dead Legion. It seemed appropriate to save him.’

‘From the Dead Legion? Alone?’ Durdil’s grey eyebrows rose a fraction.

‘There were five of them, sir, youngsters on a blood hunt to prove their manhood.’

‘And how did they manage to surround the major?’

‘Couldn’t say, sir.’

‘No, though I note from General Tariq’s subsequent report that the major is no longer a major.’

‘As you say, sir.’

‘And the family you allowed into our country?’

‘A woman with three children, starving and filthy. Husband killed by the Dead, fleeing to save her children’s lives. It was … it was the right thing to do.’

‘You are a soldier, Tailorson. Right and wrong is for your superiors to decide.’

Crys met his eyes. ‘Right and wrong is for every man to decide. Sir.’

Durdil leant back in his chair and pursed his lips. Crys stared past his left ear, palms clammy. ‘There is a pattern here, Tailorson. You have talent, you have intelligence, you have flair. You could be an outstanding officer. And yet every time you reach captain you do something to get demoted. Are you afraid of being a leader?’

Crys’s left eyelid flickered. ‘Sir.’

‘Was that a “yes, sir” or a “no, sir”, Tailorson?’

‘It was an “I don’t know the answer to your question, sir”, sir.’

‘Well, you’re honest, at least. You’re to join the Palace Rank, Tailorson.’ Durdil shuffled some papers. ‘But because I’m curious about you, you’re to be under my direct command.’

‘Sir.’

The corner of Durdil’s mouth twitched. ‘Normally I’d assume the “Sir” was agreement, but with you I’m not so sure. South barracks. Report to Major Wheeler at dusk for the night shift. Dismissed.’ Crys saluted, spun on his heel and marched to the door. ‘And, Tailorson? Turn up hungover in my presence again and you won’t be demoted; I’ll flog the booze out of you myself. Off you go.’

How does he know? How can he possibly know? I’ve had a bath, a shave, a change of uniform. Crys was still pondering it when he exited the palace and was slapped in the face with a gust of rain. He shivered and hunched his shoulders against the wet. His scarf and cloak were in the barracks in the second circle of the city, a good half-hour’s walk away. The palace crouched at the centre of the city, surrounded by walls like the heart of an onion.

He made his way through the gate into the fourth circle, walking fast and trying not to gawk. The palace in Fifth Circle was awe-inspiring and suitably royal, but Fourth Circle was home to the nobles. Real people lived here, albeit rich and powerful ones, in houses that were ridiculous confections of wood and stone and paint and carved plinths, all set in lavish grounds that could have accommodated three times the number of houses but seemed to serve no purpose except to look pretty.

Rich men and their rich fancies. Never mind the slums in First Circle and the beggars holed up in the tanneries or the slaughter district. Still, it was wide open and defensible and another layer of protection between the palace and any invaders.

Crys snorted and wiped rain from his face. Rumours of unrest were one thing, but Rilporin couldn’t fall. Even the thought was impossible. He stood aside for a clatter of horses and their noble riders, peering up in case it was the Prince Rivil. Still couldn’t quite believe that. When the prince’d run out of copper knights to bet with, he’d started using silver royals as if they were nothing, and he’d given Crys all his winnings at the end of the night. He hadn’t counted it but he was pretty sure it was more than a month’s pay.

Crys felt a stab of shame at how dismissive he’d just been of the nobility. Rivil wasn’t like that and he was more than a lord. He was royalty and, yes, he gambled and drank, but he also rewarded those who served him and aided the king and the heir, Prince Janis, in running Rilpor. Rivil probably did more for the people than all the nobility put together.

Galtas, though. Galtas was as unpleasant as a runny shit, and the loathing was mutual. It had taken all of an hour for them to agree on that, and it was the only thing they did agree on. There was just something wrong about him, something inherently untrustworthy. Crys didn’t think he should have so prominent a position close to the prince. But maybe that was Rivil’s weakness? A certain blindness to the bad in people. It would be a shame if true. Crys found he didn’t want to see Rivil get hurt.

He exited the fourth circle into the silk and spice quarter of the third, the scents wafting despite the rain. He bought dried mint for tea to settle his stomach and some massively overpriced pepper to spice up the standard-issue breakfast pottage. This might be Rilporin, but it seemed rations were the same wherever you were stationed.

Rilporin, fairest city in the world. He reckoned the whole of Three Beeches, his home town, would fit in Fourth Circle with room to spare. The shops and stalls stopped selling silks and spices and he was in the craft district, with wares of all kinds on display, from tiny polished metal mirrors to knives, cooking pots and jewellery side by side with carved wooden toys and fine beeswax candles. It was a warren of delights, from the pretty girls selling their goods to the gossip they let fall so easily from their painted mouths.

By the time he’d got through the craft district into the cloth district his purse was lighter and he’d had to buy a pack to carry his purchases. Still, the new knife for his brother Richard and the wooden horse for little Wenna were worth every copper and more. Just a shame he couldn’t see their faces when they were delivered.

The sun was westering as he tucked the last of his purchases into his pack, and he slung it over his shoulder and hurried through the press towards the gate into Second Circle and the south barracks. Hungover was bad enough. If he was late as well, he may as well kiss his captaincy goodbye – again.

The south barracks were awash with the scent of fifteen hundred men living in close proximity. Feet and armpits and farts, mostly, the hint of sweat and blood souring the mixture further. Crys barely noticed; he’d been a soldier for twelve years and his nose had long since stopped recognising that particular odour.

The south barracks’ captains shared a small room away from the main dormitories, a luxury he hadn’t been expecting. He slid into it now, just as Kennett, his bunk-mate, was shrugging into his uniform.

Kennett whistled. ‘Cutting it fine, aren’t you?’

Crys flung the pack on to his bunk and tore at the buttons of his sodden uniform. He had one more, dry and mostly clean, which had been stuffed with packets of sweet-smelling herbs for the journey. He dragged it out of his chest and shook it out. ‘Got lost,’ he said.

Kennett eyed the pack and shook his head. ‘Sure,’ he said. ‘Lost. Right.’

‘What’s this Wheeler like, anyway?’ Crys asked as he towelled his hair and struggled into the dry uniform.

‘An annoying little shit, mostly,’ a voice said. Crys had his head stuck in his uniform and grunted in reply. ‘Stickler for the rules, particularly for punctuality,’ the voice continued.

‘Sounds charming,’ Crys said, his voice muffled. Kennett didn’t answer. The voice didn’t answer. Shit. Crys forced his head through the neck hole and looked over to the door. Really shit.

He snapped out a salute. ‘Major Wheeler? Captain Crys Tailorson reporting for duty.’

‘No, you’re not,’ Wheeler said. ‘You’re still getting dressed.’

‘I got lost, sir. A thousand apologies, sir.’ He buckled his sword belt, did up his buttons and dragged fingers through his hair.

‘Did you?’ Wheeler asked. ‘I trust it won’t happen again.’

‘Absolutely not, sir,’ Crys said and snapped into parade rest. Wheeler was taller than him, lean in the waist and broad in the shoulders. He stood with an easy grace that told Crys he knew exactly how to use the sword on his hip. His face was calm, his eyes curious and maybe, just maybe, the littlest bit amused.

‘Are you an arse-licker, Tailorson?’ Wheeler asked.

‘No, sir, never could get used to the taste. Just keen to make a good first impression.’

Wheeler huffed. ‘Well, you haven’t, so stop trying to ingratiate yourself and fall in.’ He gestured through the door and Crys saw his men. His Hundred. All listening to this little exchange with the greatest of enthusiasm. Crys saluted and marched past Wheeler into the corridor. He swept his gaze along the Hundred and found nothing to fault. What they thought was another matter entirely.

‘Our post, Major?’ he asked.

‘East wing of the palace. The heir and His Highness Prince Rivil’s quarters and surrounds. This is your lieutenant, Roger Weaverson. Rilporin born and bred. Take him with you next time you venture into the city, Captain. He’ll see you don’t get lost.’

‘Thank you, Major,’ Crys said, and nodded to Weaverson, a lanky youth with more spots than beard, but he too carried a sword and carried it well. ‘Lieutenant, Hundred, my name is Captain Crys Tailorson, late of the North Rank. I don’t know you yet, but I’ll come and speak to each of you during this shift. Any questions or concerns, please do speak up and I’ll see what can be done.’ He faced Wheeler again and saluted.

‘You have command, Captain,’ Wheeler said.

Crys nodded. ‘Lieutenant Weaverson, fastest route to the palace,’ he said.

They set out, his Hundred marching behind him, and Crys felt himself fall into the same rhythm, the movements as automatic as breathing. Weaverson took them on a circuitous route, and Crys had his earlier suspicion confirmed: the roads deliberately curved away from the gates in each circle to confuse and confound an enemy. Made it a bastard to do your shopping, but if this place was ever attacked, it’d be a blessing and no mistake.

‘So, Lieutenant, what should I know about my Hundred?’

‘Good men all, sir,’ Weaverson said, as Crys had expected. Never mind, he’d find out soon enough. ‘Can I ask a question, sir?’ Crys nodded. ‘Is it true about the Dead Legion and the Mireces, that they’ve allied to invade? You coming from the North, I thought you’d know the truth of it.’

‘I know nothing of it, by which you can assume it’s horseshit, Lieutenant. My ear is always pressed most firmly to the ground, and I haven’t heard it. The Dead have their own honour, their own code and their own gods. A version of our gods, really, when you get down to it. They’re a small cult within Listre and even if they did join forces with the Raiders, there aren’t enough of them to make much of a difference. So no, I wouldn’t expect there to be verified news of an alliance.’

‘So there isn’t a Mireces invasion coming? Puck has a brother in the West, and he said they’re restless up there, causing all sorts of mischief.’

‘Causing mischief and invading a country are two fairly different things, Lieutenant,’ Crys said, and took the sting from his words with a grin and a slap on the boy’s back. ‘Soldiers talk. Gods, we gossip worse than women at the loom or men in their cups. But I might be wrong, so we should probably guard those princes really well, don’t you think? In case the Mireces have made it into the palace? I want you using every ounce of your guarding muscles, all right? Let no inch of the blank stone wall opposite your face go unstudied during the endless, cold hours ahead. Concentrate really hard on the important stuff, like standing up straight and not farting when someone rich walks past.’

There were chuckles from the first couple of ranks behind him and a sheepish smile from Weaverson. ‘It’s an important job, lads,’ he called, raising his voice, ‘even if it isn’t a complicated one. So if you cock it up, I’ll know you’re a complete imbecile and will treat you accordingly. This is my first shift as your captain. Don’t make me look bad and I won’t have to make you search for something I think I might have lost at the bottom of a deep and pungent cesspit.’ More laughter, and Crys knew they were relaxing into his command, deciding he was all right, not a high-born, bought-his-commission, weak-chinned moron.

Crys took a deep breath of cold night air, sucking it in through his nose and exhaling through a broad grin. Greatest city, tallest walls, miles from a border that might get feisty at any moment. Even better, there was money in his purse and men under his command. Truly was it said that life could be worse than being a captain in His Majesty’s Palace Rank.

RILLIRIN (#ulink_11ca0dd7-e2dc-5682-b18a-716016e15432)

Eleventh moon, year 994 since the Exile of the Red Gods

Sky Path, Gilgoras Mountains

She’d thought the storm a blessing when it rushed in, covering her tracks and blowing her scent downhill. She’d stumbled through the night, expecting every moment to be caught, for the Mireces’ dogs to fasten their teeth in her and drag her into the snow. She’d made it on to the Sky Path and to the source of the Gil River before she’d heard the first howls on the wind. She’d made it so much further than she’d expected, a night and a morning and an afternoon.

Now, though, with the sky darkening to dusk again and her skin as blue as her gown where it wasn’t rusty with dried blood, facing an angry mountain cat, Rillirin changed her mind. There were no more blessings left, not for the likes of her.

‘I don’t want your goat,’ she hissed and the cat’s yowl went up an octave. She edged back the way she’d come, back in the direction of her pursuers, wondering which way to die would be least painful. Probably the cat. But the cat’s ears were better than hers and they pricked up, the rumble of threat dying in its throat. It’d heard those hunting her despite the howl of the wind. They were closer than she’d thought, then. She cursed and looked behind, catching flickers of torchlight further up the mountain, the faintest tang of smoke. Liris’s blood was a beacon calling to the dogs, and she hadn’t had the foresight to wash it off. Now it was too late.

Stay ahead of them, get down into the foothills, find someone who’ll help. She shifted back towards the cat and its ears flattened, then pricked again. Face it, no one’s going to help a woman dressed in blue and covered in blood. You’re dead whoever finds you first. Rillirin swallowed tears and shoved her hair back out of her eyes. Then fuck you all, she thought, I’ll save myself. Somehow.

Gripping the remains of the goat, the cat bounded lightly down the sheer rock face on to a ledge Rillirin hadn’t noticed and vanished, its pelt as patchy white as its surroundings. Follow it or follow the path? Could the dogs handle the cat’s path? Could she?

A faint howl on the wind made up her mind for her and she edged on to the steep rock, her boots scrabbling for purchase, the wind tearing at the remains of her skirt and throwing her off balance. She skidded, fell hard on her right hip and was sliding down the rock before she’d had a chance to suck in breath to scream.

She hit the cat’s ledge, winded, and sailed on past, faster, stone burning the backs of her legs and arse until there was no more mountain and then she did scream, falling through space for long, endless seconds, eyes screwed shut, arms flailing uselessly through the air.

She hit water so cold it felt like knives stabbing into her. She’d thought herself cold before, but this was cold that burnt. Everything constricted and she hit the bottom. Fighting her way back up against the drag of her skirts, her head broke the surface and she warbled in a breath, lungs burning as well as her skin. She opened her eyes in time to see the rock the current slammed her into, crumpling her body and forcing her head back beneath the icy surface. She rebounded and the current swept her on, every breath a choking effort against the cold and the insidious lethargy creeping through her limbs.

She could hear the echo of men and dogs lost somewhere behind her, far above the river. If she survived the cold, survived the weight of her skirts dragging her down, survived the rocks, rapids and falls, she’d gladly pray daily for the rest of her life to any god who’d have her.

The river’s voice changed, deeper and angrier, a full-throated roar. The cold, the pain: none of it mattered. There was a waterfall ahead, and Rillirin wasn’t sure she’d survive this fall. She started to paddle, then to thrash, her limbs heavy and dull. The current picked up, swirling her with playful malevolence into the centre of the river, and then again, endlessly, she fell.

Rillirin must’ve gone another half-mile after the waterfall before the water slowed and she managed to haul herself on to the bank. She’d seen enough slaves die of cold in Eagle Height and so she stripped off her gown. She wrung out the worst of the water and then used the rough material to scrub hard at her skin, stimulating blood flow. At least I don’t smell of blood any more. A giggle escaped through chattering teeth.

She staggered forward, fell to her hands and knees and stared blearily at the ground. Pine needles. She crawled forwards into the shadow of trees, a copse so small as to not be worth the name. The wind still howled through the trunks and gouged her skin but the softness under her knees brought tears to her eyes. She squirmed behind a trunk and the wind lessened. Rillirin curled on her side and dragged at the ground, piling needles up and over her, heaping them on to her thighs and flank and chest, against her shoulders and around the back of her head, draping the gown over the top. It cut the wind even further. A few minutes to restore some warmth and she’d look for some way to make a fire. Just a few minutes …

Rillirin blinked and stretched, felt an immediate bite of cold as the pine needles slithered away and the damp wool of her gown settled against her skin.

Daylight. Fuck, she’d slept all night. They could be right there, right behind her. Rillirin lay still, her eyes roaming between the trees and out on to the mountainside. The river chattered angrily behind her, swollen with snowmelt. There wasn’t any movement, and she didn’t expect the Mireces would wait for her to wake up before taking her captive. Had they passed her by, or missed her completely and taken the path she’d meant to take herself?

Rillirin slid to her feet and into her gown, torn and ragged now, one sleeve missing, but all she had against the cold. Checking for movement, she crept to the bank and splashed water into her mouth, wincing at the cold and the pain in her face and jaw, pain which started to spread throughout her body as her muscles woke.