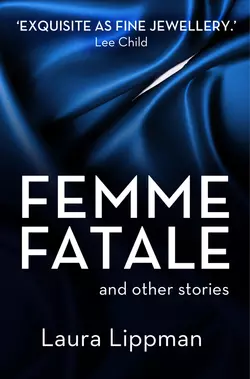

Femme Fatale and other stories

Laura Lippman

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 234.27 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Seven deliciously dark, funny and twisted short stories from one of America’s top crime writers.EXCLUSIVE EBOOK EDITION ALSO INCLUDES A FREE EXTRACT FROM LAURA’S FORTHCOMING NOVEL THE INNOCENTS.If you haven’t discovered Laura Lippman yet, delve into these seven ingenious tales and read an exclusive extract from Laura’s latest novel The Innocents.In this short story collection we are taken back to richly drawn 1975 where we meet Sofia and her degenerate gambling father in ‘Hardly Knew Her’; and in ‘Femme Fatale’ we are introduced to sixty-eight year old Mona who suddenly finds herself in a rather surprising situation.Sometimes poignant, sometimes humorous and always filled with shocking twists and turns, expect the unexpected…If you enjoy this collection, why not try ‘The Accidental Detective and other stories’. Also available now as an exclusive ebook short story collection.