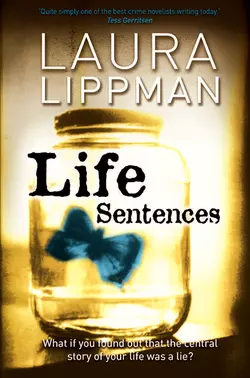

Life Sentences

Laura Lippman

A writer discovers the truth about her past in this haunting and multi-layered thriller from the multi-award-winning New York Times bestseller.What if you found out that the central story of your life was a lie?A successful writer returns to her hometown of Baltimore on the hunt for new material and stumbles into the middle of a mystery which takes her back to her schooldays.Former classmate Callie Jenkins hit the headlines when she was jailed for 7 years having refused to give up the whereabouts of her missing child. But why did she remain silent? And whatever happened to the little boy?Cassandra thinks she can find out. But in the course of her investigation she finds out that her own history might be far from the truth…

LAURA LIPPMAN

Life Sentences

Copyright (#ulink_3fa575d5-552c-5d7b-8f84-7c6c593b5770)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

AVON

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in the USA by HarperCollinsPublishers, New York, NY, 2009

Copyright © Laura Lippman 2009

Laura Lippman asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

Source ISBN: 9781847560933

Ebook Edition © 2009 ISBN: 9780007328970

Version: 2018-06-13

In loving memory of James Crumley, 1939–2008.

Take my word. It was fun.

I detest the man who hides one thing in the depths of his heart, and speaks for another.

—THE ILIAD

Table of Contents

Title Page (#ub7b1a119-53ec-5eb8-b305-a213a6ea4f7d)

Copyright (#u5b5bfe4b-f814-590d-ba8e-15c71ca77df1)

Dedication (#u3e09d2c4-aa4e-53ef-a71a-15f5963f1195)

Epigraph (#u835b1beb-74c2-53f8-9947-db0dc7dde972)

Chapter One (#ulink_f98e164a-e2bc-5cd3-bebd-894bfb706e0b)

Part 1-Bridgeville: February 20–23

Chapter Two (#ulink_31c6e402-c8b2-549f-9262-8864b8d18c47)

Chapter Three (#ulink_ea21c20b-37ab-5368-bc48-d7bb108dfa92)

Chapter Four (#ulink_307c46d2-921a-52b1-9342-ec9987e0cb73)

Part 2-Banrock Station: February 25–28

Chapter Five (#ulink_7cf53a99-d159-5201-b99b-7381bea0b84d)

Chapter Six (#ulink_9c7af0aa-8dfc-54f5-a814-8498f584f4d1)

Chapter Seven (#ulink_bd5e0f99-f1da-5689-a6f4-a2f875b37275)

Part 3-Glass Houses: March 1–2

Chapter Eight (#ulink_dac78847-9c92-5f05-a4c3-3f7468223584)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 4-The Brier Patch: March 3–5

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 5-Collectors: March 11–12

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 6-Low Countries: March 14–21

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 7-How To Cook Everything: March 24–27

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 8-Natural Selection: March 28–29

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 9-And Agamemnon Dead: March 29–31

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 10-Happy Wanderers: September 5–6

Chapter Thirty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Excerpt from The Innocents (#litres_trial_promo)

Autumn 1977–Spring 1978 (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note

About the Author

Copyright (#ulink_46e36d29-e0f2-53df-ba93-f26bc4247019)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#u947e72b4-c54f-5078-842e-a5bac4575c69)

‘Well,’ the bookstore manager said, ‘it is Valentine’s Day.’

It’s not that bad, Cassandra wanted to say in her own defense. But she never wanted to sound peevish or disappointed. She must smile, be gracious and self-deprecating. She would emphasize how wonderfully intimate the audience was, providing her with an opportunity to talk, have a real exchange, not merely prate about herself. Besides, it wasn’t tragic, drawing thirty people on a February night in the suburbs of San Francisco. On Valentine’s Day. Most of the writers she knew would kill for thirty people under these circumstances, under any circumstances.

And there was no gain in reminding the bookseller—Beth, Betsy, Bitsy, oh dear, the name had vanished, her memory was increasingly buggy—that Cassandra had drawn almost two hundred people to this same store on this precise date four years earlier. Because that might imply she thought someone was to blame for tonight’s turnout, and Cassandra Fallows didn’t believe in blame. She was famous for it. Or had been.

She also was famous for rallying, and she did just that as she took five minutes to freshen up in the manager’s office, brushing her hair and reapplying lipstick. Her hair, her worst feature as a child, was now her best, sleek and silver, but her lips seemed thinner. She adjusted her earrings, smoothed her skirt, reminding herself of her general good fortune. She had a job she loved; she was healthy. Lucky, I am lucky. She could quit now, never write a word again, and live quite comfortably. Her first two books were annuities, more reliable than any investment.

Her third book—ah, well, that was the unloved, misshapen child she was here to exalt.

At the lectern, she launched into a talk that was already honed and automatic ten days into the tour. There was a pediatric hospital across the road from where I grew up. The audience was mostly female, over forty. She used to get more men, but then her memoirs, especially the second one, had included unsparing detail about her promiscuity, a healthy appetite that had briefly gotten out of control in her early forties. It was a long-term-care facility, where children with extremely challenging diagnoses were treated for months, for years in some cases. Was that true? She hadn’t done that much research about Kernan. The hospital had been skittish, dubious that a writer known for memoir was capable of creating fiction. Cassandra had decided to go whole hog, abandon herself to the libertine ways of a novelist. Forgo the fact-checking, the weeks in libraries, the conversations with family and friends, trying to make her memories gibe with hard, cold certainty. For the first time in her life—despite what her second husband had claimed—she made stuff up out of whole cloth. The book is an homage to The Secret Garden—in case the title doesn’t make that clear enough—and it’s set in the 1980s because that was a time when finding biological parents was still formidably difficult, almost taboo, a notion that began to lose favor in the 1990s and is increasingly out of fashion as biological parents gain more rights. It had never occurred to Cassandra that the world at large, much like the hospital, would be reluctant to accept her in this new role. The story is wholly fictional, although it’s set in a real place.

She read her favorite passage. People laughed in some odd spots.

Question time. Cassandra never minded the predictability of the Q-and-A sessions, never resented being asked the same thing over and over. It didn’t even bother her when people spoke of her father and mother and stepmother and ex-husbands as if they were characters in a novel, fictional constructs they were free to judge and psychoanalyze. But it disturbed her now when audience members wanted to pin down the ‘real’ people in her third book. Was she Hannah, the watchful child who unwittingly sets a tragedy in motion? Or was she the boy in the body cast, Woodrow? Were the parents modeled on her own? They seemed so different, based on the historical record she had created. Was there a fire? An accident in the abandoned swimming pool that the family could never afford to repair?

‘Did your father really drive a retired Marathon cab, painted purple?’ asked one of the few men in the audience, who looked to be at least sixty. Retired, killing time at his wife’s side. ‘I ask only because my father had an old DeSoto and…’

Of course, she thought, even as she smiled and nodded. You care about the details that you can relate back to yourself. I’ve told my story, committed over a quarter of a million words to paper so far. It’s your turn. Again, she was not irked. Her audience’s need to share was to be expected. If a writer was fortunate enough to excite people’s imaginations, this was part of the bargain, especially for the memoir writer she had been and apparently would continue to be in the public’s mind, at least for now. She had told her story, and that was the cue for them to tell theirs. Given what confession had done for her soul, how could she deny it to anyone else?

‘Time for one last question,’ the store manager said, and pointed to a woman in the back. She wore a red raincoat, shiny with moisture, and a shapeless khaki hat that tied under her chin with a leather cord.

‘Why do you get to write the story?’

Cassandra was at a loss for words.

‘I’m not sure I understand,’ she began. ‘You mean, how do I write a novel about people who aren’t me? Or are you asking how one gets published?’

‘No, with the other books. Did you get permission to write them?’

‘Permission to write about my own life?’

‘But it’s not just your life. It’s your parents, your stepmother, friends. Did you let them read it first?’

‘No. They knew what I was doing, though. And I fact-checked as much as I could, admitted the fallibility of my memory throughout. In fact that’s a recurring theme in my work.’

The woman was clearly unsatisfied with the answer. As others lined up to have their books signed, she stalked to the cash registers at the front of the store. Cassandra would have loved to dismiss her as a philistine, a troublemaker irritable because she had nothing better to do on Valentine’s Day. But she carried an armful of impressive-looking books, although Cassandra didn’t see her own spine among them. The woman was like the bad fairy at a christening. Why do I get to write the story? Because I’m a writer.

Toward the end of the line—really, thirty people on a wet, windy Valentine’s Day was downright impressive—a woman produced a battered paperback copy of Cassandra’s first book.

‘In-store purchases only,’ the manager said, and Cassandra couldn’t blame her. It was hard enough to be a bookseller these days without people bringing in their secondhand books to be signed.

‘Just one can’t hurt,’ said Cassandra, forever a child of divorce, instinctively the peacemaker.

‘I can’t afford many hardcovers,’ the woman apologized. She was one of the few young ones in the crowd and pretty, although she dressed and stood in a way that suggested she was not yet in possession of that information. Cassandra knew the type. Cassandra had been the type. Do you sleep with a lot of men? she wanted to ask her. Overeat? Drink, take drugs? Daddy issues?

‘To…?’ Fountain pen poised over the title page. God, how had this ill-designed book found so many readers? It had been a relief when the publisher repackaged it, with the now de rigueur book club questions in the back and a new essay on how she had come to write the book at all, along with updated information on the principals. It had been surprisingly painful, recounting Annie’s death in that revised epilogue. She was caught off guard by how much she missed her stepmother.

‘Oh, you don’t have to write anything special.’

‘I want to write whatever you want me to write.’

The young woman seemed overwhelmed by this generosity. Her eyes misted and she began to stammer: ‘Oh—no—well, Cathleen. With a C. I—this book meant so much to me. It was as if it was my story.’

This was always hard to hear, even though Cassandra understood the sentiment was a compliment, the very secret of her success. She could argue, insist on the individuality of her autobiography, deny the universality that had made it appealing to so many—or she could cash the checks and tell herself with a blithe shrug, ‘Fuck you, Tolstoy. Apparently, even the unhappy families are all alike.’

To Cathleen, she wrote in the space between the title, My Father’s Daughter, and her own name. Find your story and tell it.

‘Your signature is so pretty,’ Cathleen said. ‘Like you. You’re actually very pretty in person.’

The girl blushed, realizing what she had implied. Yet she was far from the first person to say this. Cassandra’s author photo was severe, a little cold. Men often complained about it.

‘You’re pretty in person, too,’ she told the girl, saving her with her own words. ‘And I wouldn’t be surprised if you found there was a book in your story. You should consider telling it.’

‘Well, I’m trying,’ Cathleen admitted.

Of course you are. ‘Good luck.’

When the line dispersed, Cassandra asked the bookstore manager, ‘Do you want me to sign stock?’

‘Oh,’ the manager said with great surprise, as if no one had ever sought to do this before, as if it were an innovation that Cassandra had just introduced to bookselling. ‘Sure. Although I wouldn’t expect you to do all of them. That would be too much to ask. Perhaps that stack?’

Betsy/Beth/Bitsy knew and Cassandra knew that even that stack, perhaps a fifth of the store’s order, could be returned once signed. So many things unspoken, so many unpleasant truths to be tiptoed around. Just like my childhood all over again. The book was number 23 on the Times’s extended list and it was gaining some momentum over the course of the tour. The Painted Garden was, by almost any standard, a successful literary novel. Except by the standard of the reviews, which had been uniformly sorrowful, as if a team of surgeons had gathered at Cassandra’s bedside to deliver a terminal verdict: Writing two celebrated memoirs does not mean you can write a good novel. Gleefully cruel or hostile reviews would have been easier to bear.

Still, The Painted Garden was selling, although not with the velocity expected by her new publisher, which had paid Cassandra a shocking amount of money to lure her away from the old one. Her editor was already hinting that—much as they loved, loved, loved her novel—it would be, well, fun if she wanted to return to nonfiction. Wouldn’t that be FUN? Surely, approaching fifty—not that you look your age!—she had another decade or so of life to exploit, another vital passage? She had written about being someone’s daughter and then about being someone’s wife. Two someones, in fact. Wasn’t there a book in being her?

Not that she could see. This novel had been cobbled together with a few leftovers from her life, the unused scraps, then padded by her imagination, not to mention her affectionate memories of The Secret Garden. (A girl exploring a forbidden space, a boy in a bed—why did she have to explain these allusions over and over?) On some level, she was flattered that readers wanted her, not her ideas. The problem was, she had run out of life.

Back in her hotel room, she over-ordered from room service, incapable of deciding what she wanted. The restaurant in the hotel was quite good, but she was keen to avoid it on this night set aside for lovers. Even under optimal circumstances, she had never cared for the holiday. It had defeated every man she had known, beginning with her father. When she was a little girl, she would have given anything to get a box of chocolates, even the four-candy Whitman’s Sampler, or a single rose. Instead, she could count on a generic card from the Windsor Hills Pharmacy, while her mother usually received one of those perfume-and-bath-oil sets, a dusty Christmas markdown. Her father’s excuse was that her mother’s birthday, which fell on Washington’s, came so hard on the heels of Valentine’s Day that he couldn’t possibly do both. But he executed the birthday just as poorly. Her mother’s birthday cakes, more often than not, were store-bought affairs with cherries and hatchets picked up on her father’s way home from campus. It was hard to believe, as her mother insisted, that this was a man who had wooed her with sonnets and moonlight drives through his hometown of DC, showing her monuments and relics unknown to most. Who recited Poe’s ‘Lenore’—And, Guy de Vere, hast thou no tear?—in honor of her name.

One year, though, the year Cassandra turned ten, her father had made a big show of Valentine’s Day, buying mother and daughter department store cologne, Chanel No. 5 and lily of the valley, respectively, and taking them to Tio Pepe’s for dinner, where he allowed Cassandra a sip of sangria, her first taste of alcohol. Not even five months later, as millions of readers now knew, he left his wife. Left them, although, in the time-honored tradition of all decamping parents, he always denied abandoning Cassandra.

Give her father this: He had been an awfully good sport about the first book. He had read it in galleys and requested only one small change—and that was to safeguard her mother’s feelings. (He had claimed once, in a moment of self-justification, that he had never loved her mother, that he had married because he felt that a scholar, such as he aspired to be, couldn’t afford to dissipate his energies. Cassandra agreed to delete this, although she suspected it to be truer than most things her father said.) He had praised the book when it was a modest critical success, then hung on for the ride when it became a runaway bestseller in paperback. He had been enthusiastic about the forever-stalled movie version: Whenever another middle-aged actor got into trouble with the law, he would send along the mug shot as an e-mail attachment, noting cheerfully, ‘Almost desiccated enough to play me.’ He had consented to interviews when she was profiled, yet never pulled focus, never sought to impress upon anyone that he was someone more than Cassandra Fallows’s father.

Lenore, by contrast, was often thin lipped with unexpressed disapproval, no matter how many times Cassandra tried to remind people of her mother’s good qualities. Everyone loves the bad boy. Come April, her father would be center stage again, and there was nothing Cassandra could do about that.

She sighed, thinking about the unavoidable trip back to Baltimore once her tour was over, the complications of dividing her time between two households, the special care and attention her mother would need to make up for her father being lionized. Did she dare stay in a hotel? No, she would have to return to the house on Hillhouse Road. Perhaps she could finally persuade her mother to put it up for sale. Physically, her mother was still more than capable of caring for the house, but that could change quickly. Cassandra had watched other friends dealing with parents in their seventies and eighties, and the declines were at once gradual and abrupt. She shouldn’t have moved away. But if she hadn’t left, she never would have started writing. The past had been on top of her in Baltimore, suffocating and omnipresent. She had needed distance, literal distance, to begin to see her life clearly enough to write about it.

She turned on the television, settling on CNN. As was her habit on the road, she would leave the television on all night, although it disrupted her sleep. But she required the noise when she traveled, like a puppy who needs an alarm clock to be reminded of its mother’s beating heart. Strange, because her town house back in Brooklyn was a quiet, hushed place and the noises one could hear—footsteps, running water—were no different from hotel sounds. But hotels scared her, perhaps for no reason greater than that she’d seen the movie Psycho in second grade. (More great parenting from Cedric Fallows: exposure to Psycho at age seven, Bonnie and Clyde when she was nine, The Godfather at age fourteen.) If the television was on, perhaps it would be presumed she was awake and therefore not the best choice for an attack.

Her room service tray banished to the hall, she slid into bed, drifting in and out of sleep against the background buzz of the headlines. She dreamed of her hometown, of the quirky house on the hill, but it was 4 A.M. before she realized that it was the news anchor who kept intoning Baltimore every twenty minutes or so, as the same set of stories spun around and around.

‘…The New Orleans case is reminiscent of one in Baltimore, more than twenty years ago, when a woman named Calliope Jenkins repeatedly took the Fifth, refusing to tell prosecutors and police the whereabouts of her missing son. She remained in jail seven years but never wavered in her statements, a very unique legal strategy now being used again….’

Unique doesn’t take a modifier, Cassandra thought, drifting away again. And if something is being used again, it’s clearly not unique. Then, almost as an afterthought, Besides, it’s not Kuh-lie-o-pee, like the instrument or the Muse—it’s Callieope, almost like Alley Oop, which is why Tisha shortened her name to Callie.

A second later, her eyes were wide open, but the story had already flashed by, along with whatever images had been provided. She had to wait through another cycle and even then, the twenty-year-old photograph—a grim-faced woman being escorted by two bailiffs—was too fleeting for Cassandra to be sure. Still, how many Baltimore women could there be with that name, about that age? Could it—was she—it must be. She knew this woman. Well, had known the girl who became this woman. A woman who clearly had done something unspeakable. Literally, to take another word that news anchors loved but seldom used correctly. To hold one’s tongue for seven years, to offer no explanation, not even the courtesy of a lie—what an unfathomable act. Yet one in character for the silent girl Cassandra had known, a girl who was desperate to deflect all attention.

‘This is Calliope Jenkins, a midyear transfer,’ the teacher had told her fourth-graders.

‘Callieope.’ The girl had corrected her in a soft, hesitant voice, as if she didn’t have the right to have her name pronounced correctly. Tall and rawboned, she had a pretty face, but the boys were too young to notice, and the girls were not impressed. She would have to be tested, auditioned, fitted for her role within Mrs Bryson’s class, where the prime parts—best dressed; best dancer; best personality; best student, which happened to be Cassandra—had been filled back in third grade, when the school had opened. These were not cruel girls. But if Calliope came on too fast or tried to seize a role that they did not feel she deserved, there would be trouble. She was the new girl and the girls would decide her fate. The boys would attempt to brand her, assign a nickname—Alley Oop would be tried, in fact, but the comic strip was too old even then to have resonance. Cassandra would explain to Calliope that she was named for a Muse, as Cassandra herself had almost been, that her name was really quite elegant. But it was Tisha who essentially saved Calliope’s young life by dubbing her Callie.

That was where Cassandra’s memories of Callie started—and stopped. How could that be? For the first time, Cassandra had some empathy for the neighbors of serial killers, the people who provided the banalities about quiet men who kept to themselves. Someone she knew, someone who had probably come to her birthday parties, had grown up to commit a horrible crime, and all Cassandra could remember was that…she was a quiet girl. Who kept to herself.

Fatima had known her well, though, because she had once lived in the same neighborhood. And Cassandra remembered a photograph from the last-day-of-school picnic in fourth grade, the girls lined up with arms slung around one another’s necks, Callie at the edge. That photo had appeared, in fact, along with several others on the frontispiece of her first book, but only as testimony to the obliviousness of youth, Cassandra’s untroubled, happy face captured mere weeks before her father tore their family apart. Had she even mentioned Calliope in passing? Doubtful. Callie simply didn’t matter enough; she was neither goat nor golden girl. Tisha, Fatima, Donna—they had been integral to Cassandra’s first book. Quiet Callie hadn’t rated.

Yet she was the one who grew up to have the most dramatic story. A dead child. Seven years in jail, refusing to speak. Who was that person? How did you go from being Quiet Callie to a modern-day Medea?

Cassandra glanced at the clock. Almost five here, not yet eight in New York, too early to call her agent, much less her editor. She pulled on the hotel robe and went over to the desk, where her computer waited in sleep mode. She started an e-mail. The next book would be true, about her, but about something larger. It would include her trademark memories but also a new story, a counterpoint to the past. She wouldn’t track down just Callie but everyone she could remember from that era—Tisha, Donna, Fatima.

Cassandra was struck, typing, by how relatively normal their names had been, or at least uniform in spelling. Only Tisha’s name stuck out and it was short for Leticia, which might explain why she had been so quick to save Calliope with a nickname. Names today were demographic signifiers and one could infer much from them—age, class, race. Back then, names hadn’t revealed as much. Cassandra threw that idea in there, too, her fingers racing toward the future and the book she would create, even as her mind retreated, hopscotching through the past, to fourth grade, then ninth grade, back to sixth grade—her breath caught at a memory she had banished years ago, one described in the first book. What had Tisha thought about that? Had she even read My Father’s Daughter?

Yet Callie would be the central figure of this next book. She must have done what she was accused of doing. Had it been a crime of impulse? An accident? How had she hidden the body, then managed not to incriminate herself, sitting all those years in jail? Was there even a plausible alternative in which Callie’s son was not dead? Was she protecting someone?

Cassandra glanced back at the television screen, watched Callie come around again. Cassandra understood the media cycle well enough to know that Callie would disappear within a day or two, that she was a place-marker in the current story, the kind of footnote dredged up in the absence of new developments. Callie had been forgotten and would be forgotten again. Her child had been forgotten, left in this permanent limbo—not officially dead, not even officially missing, just unaccounted for, like an item on a manifest. A baby, an African-American boy, had vanished, with no explanation and yet no real urgency. His mother, almost certainly the person responsible, had defeated the authorities with silence.

That’s good, Cassandra told herself. She put that in the memo, too.

First Words

I didn’t speak until I was almost three years old. And then it was only because my mother almost killed me. Almost killed both of us, but she had the luxury of making the decision. I was literally just along for the ride.

My mother didn’t worry about my silence, however. It was my father, a classics professor at Johns Hopkins University, who brooded constantly. The possibility of a nonverbal child—and all the other intellectual limitations that this circumstance implied—terrified my father so much that he would not allow my mother to consult specialists. He knew himself well enough to understand that a diagnosis could change his love for me. My father believed in unconditional love, but only under certain conditions.

Besides, he was not irrational to hope that I might be keeping my own counsel for as yet undisclosed reasons. I had walked early and hit the other developmental milestones more or less on time. And I wasn’t mute. I had a three-word vocabulary: yes, no, and Ric, which is how my father, Cedric, was known. I’m not sure why I had no term for my mother. Perhaps ‘Lenore’ was too subtle for my baby mouth. More likely, I didn’t recognize that my mother was a separate entity but saw her as my larger self, capable of detaching from my side in order to meet my needs. With her, I didn’t even use my three paltry words, instead pointing and grunting to indicate my desires. ‘We should have named her Caliban instead of Cassandra,’ my father said.

My refusal to speak continued until almost a month before my third birthday. It had snowed, an early-spring snowstorm that was uncommonly common in Baltimore. On this particular day—a Thursday, not that my three-year-old mind could distinguish days, but I have checked the family story against newspapers from that week—my mother set out to do the marketing, as she called it then, at the old Eddie’s supermarket on Roland Avenue.

The snow had started before she set out, but the radio forecaster was insisting it would not amount to much. In the brief half hour she shopped, the snow switched to rain, then changed over to sleet, and she came out to a truly treacherous world, with cars spinning out of control up and down Roland Avenue. She decided that the main roads would be safer and calculated a roundabout route back to our apartment. But she had forgotten that Northern Parkway, while wide and accommodating, was roller-coaster steep. The car slithered into its left turn onto the parkway, announcing how dangerous her choice was, but it was too late to turn back. The unsanded road lay before her, shining with ice, a traffic light at its foot. A traffic light at which she would never be able to stop. What to do?

My pragmatic, cautious mother killed the engine, took her foot off the brake and coasted down, turning our car, a turquoise-and-brown station wagon, into a toboggan. I bobbled among the sacks of groceries, unmoored and unperturbed. The car picked up speed, more speed than my mother ever anticipated, yet not enough to get her through the intersection before the light changed to red. She closed her eyes, locked her elbows, and prayed.

When she opened her eyes, we had come to rest in the tiny front yards of the houses that lined Northern Parkway, shearing off a hydrant, which sent a plume of water into the air, the droplets freezing as they came back to earth, hitting our car like so many pebbles. But the last might be a detail that my father added, as he was the one who told this story over and over. Careful Lenore, rigid Lenore, skating down a hill with her only child in the back of the car. My mother could barely stand telling it even once.

That night, at dinner, decades later as far as my mother was concerned—after the police came, after the car was towed, after we were taken to our apartment in a fire truck, along with the groceries, not so much as an egg cracked—my father finished his characteristically long discourse on his day in the groves of academe, which my father inevitably called the groves of academe. Who had said what to whom, his warlike thrusts, as he called his responses, an allusion to Maryland’s state song. His day finally dispatched, he asked, as he always did, ‘Anything to report from the home front?’

To which, I am told, I answered, although not in a recognizable language. I babbled; I circled my pudgy baby arms wildly, trying to simulate the motion of the car. I patted my head, attempting to describe the headwear of the various blue-and yellow-suited men who had come to our rescue. I even did a credible imitation of a siren. Within twenty-four hours, my words came in, like a full set of teeth.

‘And from that day forward,’ my father always says at the end—‘From that day forward’—he is a great one for repeating phrases, for emphasis—‘from that day forward, no one could ever shut you up.’

From My Father’s Daughter by Cassandra Fallows, published in 1998 and now in its nineteenth printing.

BRIDGEVILLE February 20–23 (#u947e72b4-c54f-5078-842e-a5bac4575c69)

Chapter Two (#u947e72b4-c54f-5078-842e-a5bac4575c69)

‘Cassandra Fallows? Who’s she with?’

Gloria Bustamante peered at the old-fashioned pink phone memo the temp held out with a quavering hand. The girl had already been dressed down three times today and was now so jangly with nerves that she was caroming off doors and desks, dropping everything she touched, and squeaking reflexively when the phone rang. She wouldn’t last the week, an unusually hectic one to be sure, given all the calls about the Harrington case. Too bad, because she was highly decorative, a type that Gloria favored, although not for the reasons suspected by most.

The girl examined her own handwriting. ‘She’s a writer?’

‘Don’t let your voice scale up at the end of a declarative sentence, dear,’ Gloria said. ‘No one will ever take you seriously. And I assume she’s a writer—or a reporter—if she’s calling about Buddy Harrington. I need to know which newspaper or television program she reps.’

Gloria’s tone was utterly neutral to her ears, but the girl cowered as if she had been threatened. Ah, she had probably hoped for something far more genteel when she signed up at the agency, an assignment at one of those gleaming start-ups along the water. Arriving at Gloria’s building, an old nineteenth-century town house, she would have adjusted her expectations to something old-fashioned but still grand, based on the gleaming front door and restored exterior, the leaded glass and vintage lighting on the first two floors.

Those lower floors, however, were rented to a more fastidious law firm. Gloria’s own office was on the third story, up a sad little carpeted staircase where dust rose with every step and the door gave way to a warren of rooms so filled with boxes that visitors had to take it on faith that there was furniture beneath them. ‘I want prospective clients to know that every one of the not insignificant pennies I charge goes to their defense, not my décor,’ Gloria told the few friends she had in Baltimore’s legal community. She knew that even those friends, such as they were, amended in their heads, It’s not going to your wardrobe or your upkeep, either. For Gloria Bustamante was famously, riotously, deliberately seedy, although not as cheap with herself as she was with her office. The run-down heels she wore were Prada, her stained knit suits came from Saks Jandel in DC, her dirty rings and necklaces had been purchased on lavish trips abroad. Gloria wanted people to know that she had money, that she could afford the very best—and could afford to take crappy care of the very best.

The girl stammered, ‘N-no, she’s not a journalist. She wrote that book, the one about her, um, father? Father. I read it for book club? I mean, I did, I read it for book club.’

‘Pretty young girls go to book clubs? I thought those were for ugly old broads such as me. Not that you’ll catch me in a room full of women, drinking wine and talking about a book. Drinking, maybe.’

The girl’s eyes skittered around the room, trying to find a safe place to land. Clearly, she was unsure if she was obliged to contradict the inescapable truth of Gloria’s appearance or if she should pretend that she hadn’t yet noticed that Gloria was old and ugly.

‘It was a mother-daughter book club,’ she said at last. ‘I went with my mom.’

‘Thanks for the clarification, dearie. Otherwise, I might think you went with your prepubescent daughter, conceived, in the great local tradition, when you were a mere middle schooler.’

The girl took a few steps backward. She had that breathtaking freshness seen only in girls under twenty-five when everything—hair, eyes, lips, even fingernails—gleamed without benefit of cosmetics. The whites of this girl’s eyes were more startling to Gloria than the light-blue irises, the shell-pink ears as notable as the round, peachy cheeks. And she had the kind of boyish figure that was increasingly rare in this era of casual plastic surgery, when even the thinnest girls seemed to sprout ridiculously large breasts. Gloria remembered the tricks of her youth, not that she had ever bothered with them, the padded bras, the wads of Kleenex. They had been far more credible in their way than all these perky cantaloupes, which looked, in fact, as if they had been molded with very large melon ballers. Real breasts weren’t so round. She hoped this girl wouldn’t tamper with what nature had allotted her.

‘I grew up in Ruxton?’ the girl said, and it was clear that she intended the well-to-do suburb to establish that she was not the kind of girl who had a baby at age twelve. Oh, you’d be surprised, dearie, Gloria wanted to say. You’d be shocked at the wealthy families who have sat in my office, trying to decide what to do when one of Daddy’s friends—or Daddy himself—has helped himself to an underage daughter. It happens. Even in Ruxton. After all, Buddy Harrington happened in a suburb not that far from Ruxton.

‘I’m sure you did,’ Gloria said. ‘So Cassandra Fallows wants to write a book about Buddy Harrington? She must be one of those true-crime types who specialize in whipping books out in four to six weeks. We’ll give her a wide berth.’

Buddy Harrington was, as of this third full week in February, being held responsible for 80 percent of the murders in Baltimore County this year. Granted, the county had only five homicides so far, as compared to the city’s thirty or so. Still, Harrington was charged with four of them—his mother, father, and twin sisters, all shot as they slept. The sixteen-year-old had called the police on a Thursday evening two weeks ago, claiming to have discovered the bodies after returning home from a chorale competition in Ocean City. He had been charged before the day was out, although he had yet to confess and was pressing Gloria to let him tell his story far and wide. She was holding him back precisely because of that eagerness, his keenness to perform. For Buddy Harrington was not the kind of boy who inspired the usual descriptions of those who snap—quiet, introverted. He was an outstanding student, a star athlete, and a gifted singer, well liked by classmates, admired by teachers. The community was stunned.

Gloria, who had spent several hours with Buddy since his arrest, was not. She also knew that all the things that Buddy considered his assets—his good looks, his normalcy—would undercut him. Nothing terrified people more than an all-American sociopath. And until—unless—she got Buddy into the juvenile system, she had to keep him from tainting his future jury. Which would not, of course, be a jury of his peers, but a dozen middle-class mothers and fathers who would be undone by his poise, his composure. Especially—shades of O.J.!—if he stuck to this help-me-find-the-real-killer scenario.

‘No, it’s not about Buddy. She wants to ask you about an old case?’ The girl squinted at her own handwriting. ‘Something about a calley-ope?’

‘A calley—do you mean Calliope?’ Gloria could afford to keep her office in disarray and limit her exposure to computers because the entire history of her practice was always available to her. She had a prodigious memory. On those rare occasions when someone felt intimate enough to challenge her on her drinking, she maintained that it was the only way to level the playing field.

Not that she was likely to forget Callie Jenkins under any circumstances. She had tried.

‘Yes, that’s it. Calliope. Calliope Jenks.’

‘Jenkins.’

‘Right.’

‘What, specifically, does she want to know?’

‘She wouldn’t say?’

‘Did you ask?’

The girl’s downward gaze answered the question more emphatically than any statement-question she might have offered in return. Gloria leaned across the desk and tried to take the paper, but the girl was out of reach. She moved forward tentatively, as if Gloria might bite her, jumping back as soon as Gloria had the phone memo in her hand.

‘It’s an out-of-state number,’ Gloria said. ‘New York, I think, but not the city proper. Long Island, maybe Brooklyn. I can’t keep all the new ones straight.’ She had, in fact, once been able to recognize every area code at a glance. She knew state capitals, too, and was always the one person at a party who could complete any set of names—the seven dwarves, the nine Supreme Court justices, the thirteen original colonies.

‘But she’s in town,’ the girl said, thrilled that she had gleaned an actual fact. ‘For a while, she said. That’s her cell. She said she plans to be in town for a while.’

Gloria crumpled the pink sheet and tossed it in the overflowing trash can by the desk, where it bounced out.

‘But she’s famous!’ the girl said. ‘I mean, for a writer. She’s been on Oprah.’

‘I don’t talk to people unless they can help me. That case ended a long time ago, and it’s better forgotten. Callie’s a private citizen now, living her life. It’s the least she deserves.’

Was it? Gloria wondered after dismissing the girl. Did Calliope have the least she deserved or far more? What about Gloria? Had she gotten more than she deserved, less, or exactly her due? Had Gloria done the best she could for Callie, given the circumstances, or let her down?

But Gloria didn’t like the concept of guilt any more than she liked the word guilty coming from a jury foreman, not that she had a lot of experience hearing the latter. Guilt was a waste, misplaced energy. Guilt was a legal finding, a determination made by others. Gloria didn’t have time for guilt, and she was almost certain she didn’t deserve to feel it, not in the case of Callie Jenkins. Almost.

She called the temp agency and told them she wouldn’t be able to use the new girl past this week. ‘Send me someone new. More capable, but equally pretty.’

‘You’re not allowed to say that,’ the agency rep objected.

‘Sue me,’ Gloria said.

Chapter Three (#ulink_72aaf979-358d-5798-9f94-6a49046bf712)

‘Why aren’t you staying with me?’ her mother asked, and not for the first time. ‘That was the original plan.’

‘Yes, when I was going to be in Baltimore a week. But for ten, twelve weeks? I would drive you crazy.’ And you me.

‘But a hotel room, for all that time—you won’t be able to cook for yourself—’

‘It’s an apartment, the kind set up for short-term corporate renters.’ Cassandra anticipated her mother’s next protest: ‘It’s not that expensive.’

‘Did you sublet your place back in New York?’

‘No.’

‘So you’re carrying two rents for three months. And you’ll need a car here.’

‘Mom, I have my own car. I drove down. I drove here, it’s parked in your driveway.’

‘I don’t know what the point is of having a car if you live in New York.’

‘I like to be able to get away—visit friends upstate or at the…beach.’ She used the generic, beach, instead of the specific, Hamptons, out of fear that the latter would provoke another spasm of worry.

The reviews of the last book had been hard on her mother. Her mother’s e-mails had been hard on Cassandra. Until this winter, she hadn’t even known that her mother could initiate e-mail. She seemed to use the laptop that Cassandra had given her for nothing more than playing hearts and solitaire while depending on the reply-to function to answer Cassandra’s sporadic notes. Even then, she was extremely terse. ‘Thank you.’ Or ‘That’s nice, dear.’ Lennie Fallows seemed to think e-mail was the equivalent of a telegram or a long-distance call back in the seventies. It was a mode of communication to be limited to dire emergencies or special occasions, and even then brevity was required.

Then, back in January, the e-mails had started, with no ‘RE:’ in the subject headers, with no subject headers at all, which made them all the more terrifying, as Cassandra had no idea what conversation her mother was about to start.

‘I wouldn’t worry about the Kirkus.’ ‘The PW is good, if you omit the dependent clause.’ ‘Sorry about the New York Times.’

Except she hadn’t written ‘the New York Times’ or even ‘NYT’, come to think of it, but the critic’s surname, as if the woman were a neighbor, an intimate. This detail saddened Cassandra most of all. All she had ever wanted was to give her mother a sense of ownership in Cassandra’s success. She had felt that way even as a teenager, back when Lennie was, in fact, a profound embarrassment, running around town in—oh, God, the memory still grated—painter’s pants or overalls, that horrible cap on her head, tools sticking out of her pockets. Yet Lennie insisted on crediting Cassandra’s achievements to her ex-husband’s side of the DNA ledger. Even the book that had forged Cassandra’s reputation had been problematic for her mother, arriving with that title that slanted everything toward him.

But the life that book brought Cassandra—ah, that her mother had loved and gloried in, and not because of the small material benefits that came her way. She adored turning on the radio and hearing Cassandra’s voice, basked in being in a store and having a neighbor comment on one of Cassandra’s television appearances. Once, in the Giant, Cassandra had seen how it worked: Her mother furrowed her brow at the mention of Cassandra’s most recent interview, as if it were impossible to keep track of her daughter’s media profile. Was it Today? Charlie Rose? That weird show on cable where everyone shouted?

You must be very proud of her, the neighbor persisted.

And Lennie Fallows—it had never occurred to her to drop the surname of the man she detested—said with steely joy, ‘I was always proud of her.’ In her mother’s coded lexicon, this was the rough equivalent of Go fuck yourself.

Cassandra opened the refrigerator to browse its contents, a daughter’s prerogative. It was huge, the kind of double-wide Sub-Zero one might find in a small restaurant. The kitchen had been Lennie’s latest project, and superficially, it looked great. But Cassandra knew where to find the corners her mother never stopped cutting, a legacy of the lean years that had left her so fearful. The refrigerator and the stove would be scratch-and-dent specials, with tiny flaws that prevented them from being sold at full list. The new porcelain sink would have been purchased at Lennie’s ‘professional’ discount—and, most likely, installed by her, along with the faucet and garbage disposal. She had kept the palette relatively plain. ‘Better for resale,’ she said, as if she had any intention of putting the house on the market. Like Penelope stalling her suitors, Lennie continually undid her own work. By Cassandra’s reckoning, this was the kitchen’s third renovation. Lennie was desperate not to leave the house, which had been big for a family of three, almost ruinous for a single mother and daughter, simply ridiculous for a woman now in her seventies.

But this conversation was already too fraught to take on the subject of the house, which her mother had come to love and defend against all comers. Instead, Cassandra asked her mother, ‘Do you remember Calliope?’

‘An organ? You mean at the Presbyterian church? And I think it’s pronounced differently, dear.’ Her father would have made the correction first.

‘No, in my class. Callie Jenkins. At Dickey Hill, starting in fourth grade. She’s in one of the photographs. She wore her hair in three fat braids, with those little pompon things on the ends.’

Cassandra bunched up a fistful of her own hair to jog her mother’s memory.

‘Three—oh, she must have been black.’

‘Mother.’

‘What? There’s nothing bigoted in saying that. Unless you’re me, I guess. I’m not allowed to notice the color of anyone’s skin.’

Cassandra had no desire to lecture her mother. Besides, she had a point.

‘At any rate, I was watching CNN and there was a story about this case in New Orleans—a woman’s child is missing and she took the Fifth, refused to say where the child is. Someone said it was similar to a case here years ago, involving Calliope Jenkins. It has to be the same person, don’t you think? The age is about right, and how many Calliope Jenkinses could there be in Baltimore?’

‘More than you might think.’

Cassandra couldn’t tell if her mother was being literal or trying to make some larger point about infanticide or her hometown. ‘Don’t you think that would make a good book?’

Her mother pondered. That was the precise word—she puckered her forehead and considered the question at hand as if she were Cassandra’s literary agent or editor, as if Cassandra could not go forward without her mother’s blessing.

‘True crime? That would be different for you.’

‘Not exactly true crime. I’d weave the story of what happened to Callie as an adult with our lives as children, our time in school together. Remember, she was one of the few girls who went to junior high with me.’

‘One of the few black girls,’ her mother said with a look that dared Cassandra to correct her for referencing Callie’s race.

‘Well, yes. And race is a small part of the story, I guess. But it’s really Callie’s story. If I can find her.’

‘Even if you do find her, can she speak to you? I remember the case—’

‘You do?’

‘Anyone who lived here at the time would remember.’ Was there an implicit rebuke in her mother’s words, a reminder that Cassandra had disappointed her by moving away? ‘I didn’t recognize her name, but I remember when it happened. The whole point was that she wouldn’t talk. But if she did kill her child, she can still be charged. If she didn’t, why didn’t she cooperate all those years ago?’

Cassandra was well aware of this particular problem; her editor had raised it first. They had agreed the book wouldn’t be dependent on a confession, or even answering all the questions, but the reader would need to believe that Cassandra had reached some kind of conclusion about her old school friend. Old school friend was the editor’s term, and while Cassandra had initially tried to correct the impression, using classmate and acquaintance, she soon gave up. What was a ‘friend’, after all, when you were ten or eleven? They had played together at school, gone to birthday parties together.

‘I can’t plan this book in advance. That’s what makes it exciting. With the first two books, they were already constructed, in a sense. I had lived them, I just didn’t know how I would write them. And they were very solitary enterprises. Solipsistic, even. But this time—I’m going to interview Callie, once I find her, but also other girls from the class. Tisha, Donna, Fatima. And Callie’s lawyer, I guess, and the police detective who investigated her…heavens, I’m not sure three months here will be enough.’

‘And, of course,’ her mother said, staring into her tea, ‘you’ll be here for all the hoo-haw surrounding your father.’

‘One event in a week of events,’ Cassandra said. ‘A simple onstage interview, and I’m doing it only because it will raise money for the Gordon School’s library building fund. We do owe the school a great debt. Besides, it will be interesting, interviewing Daddy in front of a captive audience. He’s the king of digressions.’

‘Yes,’ her mother said. ‘Your father loved digressing.’

‘It’s not a big deal,’ Cassandra said. She wished, as she often did, that they were a family comfortable with casual touches, that she could place her hand over her mother’s now.

‘I know,’ her mother said. ‘I just hate the way he…romanticizes what he did, to the point where he won’t even talk about it. Or her.’

Cassandra respected her mother for holding on to that ‘Or her’ for all these years, refusing to say Annie’s name unless forced. It might not be particularly healthy, but it was impressive. Cassandra shared her mother’s talent for grudges—it was, she liked to say in speeches, a useful quality for the memoirist, the ability to remember every slight, no matter how small. They called it their Hungarian streak, a reference to her mother’s mother, who had gone thirty years without speaking to her son and lived just long enough to see her granddaughter immortalize this fact in her first book. Nonnie hadn’t minded, not in the least. It had given her a little bit of cachet in the retirement center where she lived, largely indifferent to her neighbors. On what would prove to be Cassandra’s last visit with her, Nonnie had insisted on going to the dining hall, parading her successful granddaughter past the other residents: ‘My granddaughter, she’s a writer, a real one, a bestseller.’ Cassandra wasn’t sure if her grandmother had even read the book in which she took such pride; the volumes—only one book then, but Nonnie had purchased the hardcover and paperback—stood on a table in her apartment. They were, in fact, the only books in the apartment, perhaps the only books her grandmother had ever owned. Nonnie had been mystified, but proud, when her daughter had married a learned man, as she called him. And, true to her own unfathomable principles about loyalty, she continued to like Cedric Fallows even after he betrayed her daughter.

‘I’ve never understood,’ Cassandra said at that last lunch, ‘why you could forgive my father but not your own son. What did he do?’

Her grandmother waved the question away, as she had repeatedly while Cassandra was working on My Father’s Daughter. ‘Pfftt. I don’t talk to him and I don’t talk of him.’

‘Okay, but what Daddy did was pretty bad. Does that mean Uncle Leon did something even worse?’

‘Your father, Uncle Leon…who knows?’

‘Someone must know.’

‘It doesn’t matter. The book is good.’ Meaning: It sold a lot of copies. ‘It doesn’t have to be true. War and Peace isn’t true.’

‘My book is true, Nonnie. It’s a memoir, I made a point to get everything right.’

‘But you can only get things as right as people let you.’

‘Are you mad that I told the story about Uncle Leon and you? I asked your side.’

Nonnie pointed a fork at her. ‘I know how to be mad at people and if I were mad, you wouldn’t be here.’

A month later, she was dead. Cassandra was surprised to see her father at the funeral, more surprised that he had the tact not to bring Annie. He seldom went anywhere without her. Still, when the rabbi invited people up to share their thoughts, Cedric simply couldn’t resist getting up to say a few words, awkward as that was. Uncle Leon didn’t get up, nor did Cassandra’s mother, but the son-in-law who long ago ceased to be a son-in-law waxed eloquent about a woman he had never much liked.

Later, at a brunch in her mother’s house, Cassandra ventured to her father, ‘Nonnie said I didn’t know the truth of the things I wrote, that I got them wrong.’ They were alone, by the buffet table, and she was struck by the novelty of having him to herself.

‘Nonnie was the queen of the mind-fuckers,’ her father said, spearing cold cuts. ‘Do you know why she was so angry at your uncle Leon?’

‘No, she would never tell me.’

‘That’s because she couldn’t remember. He did something thirty years ago that pissed her off, but she would never tell him what it was. Then she forgot. She forgot the precipitating incident, but she never forgot the grudge. Your uncle Leon was desperate to apologize, but he never knew what he did. Your mother used to go visit her and try to guess what Leon did, so he might make amends, and your grandmother would say, “No, that’s not it,” like some Alzheimer’s-addled Sphinx or a Hungarian Rumpelstiltskin, forcing the princess to guess his name when he didn’t know it himself.’

Could it really be? Cassandra decided she believed him, although her father had never let the facts get in the way of a good story.

‘Those are your mother’s people, Cassandra,’ her father said. ‘Thank God you take after me.’

Now, more than a decade later, her mother was saying, ‘Thank God you take after me, Cassandra. In your resilience. You’ll come back from this, I’m sure of it.’

‘From what?’

‘Well—I just mean that I think you’re right, this next book could be something special.’

Her mother did not mean to suggest Cassandra was a failure. Lennie simply couldn’t escape the context of her own life, which she saw as a series of mistakes and disappointments. Yet she had actually enjoyed a brief burst of local celebrity when Cassandra was in high school, appearing on a chat show as ‘Lennie the handywoman’, demonstrating basic repairs. That was when she had started to wear overalls and painter’s caps, much to her teenage daughter’s chagrin.

A more ambitious woman might have parlayed this weekly segment into an empire; after all, the cohost of People Are Talking was a bubbly young woman named Oprah Winfrey. Years later, when Cassandra took her place on Oprah’s sofa, she had asked during the commercial break if Oprah remembered the woman who had provided those home repair tips, the one with the short sandy hair. Oprah said she did, and Cassandra wanted to believe this was true. Her mother had always been easily overlooked, which was one reason she had been enthralled with vivid, attention-grabbing Cedric Fallows.

Cassandra had always thought her mother’s transformation would be the focus of the second memoir. But sex had taken over the second book—her first two marriages, the affairs in and around them, a bad habit she had renounced on the page, if not quite in life. Her mother’s cheerful solitude had seemed out of place. In fact, it had been embarrassing, having her mother in proximity to all that sex. But her mother’s story, alone, was not enough to anchor a book. It was too straightforward, too predictable. ‘It’s a little thin,’ her first editor had said. ‘And awfully sad.’ The second part had surprised Cassandra, who thought she had written about her mother with affection and pride.

‘Does it bother you,’ Cassandra asked Lennie now, ‘that I never wrote about your life in the same way I wrote about Daddy’s?’

‘Oh no,’ her mother said. ‘It’s the nicest thing you ever did for me.’ Recovering quickly, she said, ‘Not that it’s bad, what you do. It’s just not my style, to be all exposed like that. That’s your father. And you.’

‘You just said that I take after you.’

Lennie was at the sink, her back to Cassandra as she rinsed dishes. Lennie had a top-of-the-line Bosch now, but she hewed to the belief that dishes had to be washed before they could go in the dishwasher. ‘You take after me in some ways, but you take after him in other ways. You’re strong, like me. You bounce back. But you’re…out there, letting the world know everything about you. That’s your father’s way.’

Cassandra carried her empty mug over to the sink and tried to quiet the suspicion that her own mother had, in her polite way, just called her a slut and an exhibitionist.

Chapter Four (#ulink_fa3f5880-b020-59b8-a63f-a709a4ce4603)

Stove hot.

Baby bad.

Stove hot.

Baby bad.

Stove bad.

Baby hot.

Stove bad.

Baby cold.

Stovebabyhotcold. Stovebabyhotcold. Stovebabyhotcold. Cold stove. Cold baby. Hot stove. Hot baby. Bad stove. Bad baby. Babystove, babystove, babystove.

She awoke, drenched in sweat. Supposedly part of the change, but she didn’t think that was the whole explanation in her case. After all, she had been having this dream for more than a decade now. Although it wasn’t exactly a dream, because there was nothing to see, only words tumbling over each other, rattling like spare change in a dryer.

But even if the nondream dream caused tonight’s bout of sweating, she knew menopause was coming for her. Up until a year ago, she had really believed there would be time to have one more child, to grab the ring that had been denied her repeatedly. First with Rennay, then Donntay. She wanted so little. Sometimes, she thought that was the problem. She had wanted too little. The less you asked for, the less you got. The girls who had the confidence to demand the moon got the moon and a couple of stars. They never cut their price. A man bought what they were selling or moved on. As soon as you began to bargain, the moment you revealed you were ready to take less than what you wanted—no, not wanted, but needed, required—they took everything from you.

The flush had passed, but she couldn’t go back to sleep. She changed into a dry nightgown, put on her robe, and went out to the glassed-in porch, which overlooked her neat backyard, her neighbors’ yards beyond it. It was a house-proud street, not rich, but well tended. Pretty little house, pretty little town, pretty little life. Bridgeville, Delaware.

She would rather be in jail.

She was in jail, actually, only this time, there was nothing to sustain her, no hopes or dreams or promises. No, not jail. Hell. She was in hell. Which was not, as it turned out, a place of fire and brimstone, of physical discomfort and torture. Hell was a pretty little house in a pretty little town, with plenty of food in the refrigerator and enough money in the bank. Not a lot, but enough, more than she had ever known. Her mind free from workaday worries, she had all the time in the world to dwell on what had gone wrong and could never be made right. What if she—? What if he—? What if they—? Bridgeville, Hell-aware. Most people would think it was a better fate than she deserved.

They would be right.

Amo, Amas, Amat

I was five when my father decided that I should start studying Latin and Greek. No one found this odd. He was, after all, a professor of the classics. He had named me for Cassandra, the ignored prophetess. This was after my mother refused to consider Antigone, Aphrodite, Andromeda, Atalanta, Artemis, any of the nine Muses, or—his personal favorite—Athena. After all, Athena sprang, fully formed, from her father’s head, while her mother, Metis, remained imprisoned inside. My father admired this arrangement.

My mother would have preferred to call me Diana, as Artemis is known in Roman mythology. But my father hated the Roman names and often railed at their primacy in our culture. When I had to learn the names of the planets, I couldn’t rely on mnemonic devices—My very elegant mother just served us nine pickles—because I had to transpose them in my head: Hermes, Aphrodite, Earth (‘Gaia!’ my father would correct with a bark), Ares, Zeus, Cronus, Uranus (‘The one Greek in a batch of Romans, that sly dog, and incestuous to boot,’ my father liked to say), Poseidon, Hades.

Again, no one found this odd, least of all me. My father was a man of many emphatic opinions, which he announced with the same vehemence of callers to WBAL shouting about the Orioles and the Colts. The Greek gods were preferable to the Romans. Nixon was a criminal—my father’s verdict long before Watergate. Mr Bubble was bad for the skin and the plumbing. Stovetop popcorn would give you cancer. Pornography was preferable to any ghostwritten syndicate novel, such as Nancy Drew or the Hardy Boys. Girls should not wear their hair short.

The last, at least, was mounted in my defense, when my exasperated mother wanted to chop mine off because I fought so during shampoos. ‘You take over her hair,’ she challenged my father, and he did, finding a gentle cream rinse and a wide-tooth comb that tamed my unruly mane. ‘It’s too much hair for a girl, but you’ll be glad when you’re a woman,’ he often said. One of my happiest memories is of standing in the never-quite-finished bathroom off my parents’ bedroom, my father pulling the comb through my hair, insistent but never cruel. My father—incapable of throwing a ball, bored by most sports—would have been lost with a son. The only man he understood was himself.

So, in the world according to Ric Fallows, insisting on language lessons for his only child was not at all strange. But everyone wondered why my father didn’t tutor me himself. He could read both languages, although he was far more skilled in Latin. Instead, my father took me to the home of a faculty colleague, Joseph Lovejoy, whom I was instructed to call Mr Joe, in the Baltimore fashion.

Mr Joe and his sister, Miss Jill, lived in our neighborhood in a place I liked to call the upside-down house. It was built into a bluff above the Gwynns Falls, with the living room on the top floor, the next floor down housing the kitchen and dining room, and the bedrooms on the garden level. Mr Joe sat with me in the study on the top floor, while my father helped Miss Jill prepare tea—not just the beverage but a proper tea of sandwiches and sweets. The Lovejoys were British, visiting Baltimore on some kind of academic exchange program. Miss Jill had what my father called that famous English skin, although it looked like anyone else’s skin to me. Mr Joe was tall and gaunt, and he had skin that no country would claim.

One particularly warm Saturday afternoon in May, the teakettle whistled on the floor below us. It continued to sing for almost a minute and Mr Joe decided to investigate. I could hear him walking around the floor below, then continuing down the steps to the first floor. He returned a few minutes later and announced that would be all for today. My father arrived, but not Miss Jill with the sandwiches.

‘What about tea?’ I asked.

‘There will be no tea today,’ Mr Joe said.

‘Did the kettle run dry?’

‘Did the—yes, yes, it did.’

‘And the sandwiches, the cakes?’

‘Cassandra, your manners,’ my father said.

I was almost fifteen before I figured it out. By then, I knew my father had lots of romances—‘Not romances! Dalliances. The only romance I ever had was with Annie, and I married her.’ But I didn’t know about any of the others until he left my mother for Annie and I started piecing together my father’s long history of infidelities. He rejects that word, too. ‘I was never unfaithful or faithless where your mother was concerned. Sex meant nothing to me, it was a bodily function. That was the problem. I didn’t know you could have both, sex and love, until I met Annie.’

We had this conversation a few days before I headed to college. My father had decided to lecture me on the double standard, persuade me that my own virginity was precious. He was a little late.

‘And Miss Jill?’

‘Miss Jill. Oh, the redheaded Brit. Yes, she was one. But not right away. It wasn’t a plan. Well, maybe it was a little bit of a plan.’

‘What did her brother think?’

‘Her brother? Her brother?’ My father was genuinely puzzled.

‘Mr Joe.’

‘Mr—oh, honey, he was her husband. Where did you get the idea that they were brother and sister?’

To this day, I comb my memory, certain I will find the moment of the lie. Perhaps it was my father’s insistence on calling them Mr Joe and Miss Jill, a localism that my father normally belittled. But what would have been the point in deceiving me? A sibling relationship may have kept Mr Joe from being a cuckold, but it would not excuse what my married father did with Miss Jill while ‘making tea’. A tea, I see now, that required no preparation—the cakes were store-bought, the sandwiches made well ahead of our visit, the crustless bread dry from the air yet damp from the cucumbers that had sweated on them.

Why did I think they were brother and sister? Because even my five-year-old self sensed something was off. My language lessons ended when the Lovejoys went back to England that summer. Miss Jill—Mrs Lovejoy—sent us Christmas cards for several years, but my mother never added them to our list. I spent my junior year abroad in London and discovered I hated the social convention of tea. But I loved Englishmen, especially redheaded ones—gingers—and fucked as many of them as I could.

BANROCK STATION February 25–28 (#ulink_827369ca-79dc-541c-9488-f55cc8aef474)

Chapter Five (#ulink_3f93dccd-c808-583d-a522-c5b9c372b66d)

Cassandra had begun her last two projects by packing a laptop and retreating to a weekend resort, attempting to replicate the serendipitous origins of her first book. My Father’s Daughter had started almost by itself, an accident of heartbreak and idleness: A romantic getaway, planned for West Virginia, had become a solitary one when her first husband left her, walking out after revealing a gambling addiction that had drained their various bank accounts, meager as they were, and saddled their Hoboken condo with a second and a third mortgage that made it practically worthless, despite the robust real estate market of the mid-nineties.

Disconsolate, terrified of the future, but also aware that the room was prepaid, she had driven hours in the wintry landscape—God help her, it was the weekend before Valentine’s Day—thinking that she would spend the two nights and two days crying, drinking, and eating, but she ran out of wine and chocolate much faster than anticipated. The second night, a Saturday, she awoke at 2 A.M., her head strangely clear. At first, she chalked it up to the alcohol wearing off, but when she was still awake an hour later, she pulled on the fluffy robe provided by the bed-and-breakfast—one of two fluffy robes, she noticed, feeling the clutch and lurch of fresh heartbreak—and made her way, trancelike yet lucid, to the picturesque and therefore infuriating little desk not really intended for work.

She found a few sheets of stationery in the center drawer and began scratching out, with the crummy B and B pen, the first few pages of what would become My Father’s Daughter. She had kept those pages, and while the book changed considerably over the next six months, as she wrote to blot out her pain and fear, those first few pages remained the same: I didn’t speak until I was almost three years old. Later, when she began to query agents, a famous one had said he would represent her, but only if she consented to a rewrite in which she excised that opening.

He took her to lunch, where he explained his pet theory of literature, which boiled down to The first five pages are always bullshit.

‘It’s throat clearing,’ he said over a disappointingly modest lunch of spinach salad and bottled water. Cassandra had hoped the lunch would be grander, more decadent, at one of the famous restaurants frequented by publishing types. But the agent was in one of his drying-out phases and had to avoid his usual haunts.

He continued: ‘Tapping into a microphone. Is this thing on? Hullo? Hullo?’ (He was British, although long removed from his native land.) ‘It’s overworked, too precious. As for prologues—don’t get me started on prologues.’

But Cassandra believed she had written a book about a woman finding her own voice, her own story, despite a title that suggested otherwise. Her father was simply the charismatic Maypole at the center; she danced and wove around him, ribbons twisting. She found another agent, a Southern charmer almost as famous but sweet and effusive, unstinting in her praise, like the mother Cassandra never had. Years later, at the National Book Awards—she had been a judge—she ran into the first agent, and he seemed to think they had never met before. She couldn’t help wondering if he cultivated that confusion to save face.

She had started the sequel at a spa in the Berkshires, another shattered marriage behind her, but at least she was the one who had walked out this time. Paul, her second husband, had showed up in the final pages of her first book; she had believed, along with millions of readers, that he was her fairy-tale ending. Telling the truth of that disastrous relationship—along with all the others, before, after, and during the marriage—had felt risky, and some of her original readers didn’t want to come along for the ride. But enough did, and the reviews for The Eternal Wife were even better. Of course, that was because My Father’s Daughter had barely been reviewed upon release.

Then, just eighteen months ago—not enough time, she decided now, she hadn’t allowed the novel to steep as the memoirs had—she had checked into the Greenbrier, again in West Virginia, but much removed, in miles and amenities, from that sadly would-be romantic place where the first memoir had begun. Perhaps that was the problem—she had been too self-conscious in trying to recapture and yet improve the circumstances of that first feverish episode. The woman who had started scratching out those pages in the West Virginia bed-and-breakfast had an innocence and a wonder that had been lost over the subsequent fifteen years.

Or perhaps the problem was more basic: She wasn’t a novelist. She was equipped not to make things up but to bring back things that were. She was a sorceress of the past, an oracle who looked backward to what had been. She was, as her father had decreed, Cassandra, incapable of speaking anything but the truth.

Only this time, the answers were not inside her, not most of them. Last night, in her sterile rental, she had started jotting down, stream of consciousness, what she could remember. Her list wasn’t confined to Calliope but covered every detail of life at Dickey Hill Elementary, no matter how trivial, because she knew from experience that small details could unearth large ones. The memories of the latter had come readily: foursquare, the Christmas pageant, Mrs Klein teaching us about Picasso and Chagall, the girl group. The girl group—she hadn’t thought about that in ages, although it had been key to a scene in the first book. Now and Later candies—did they even make those anymore?—the Dickeyville Fourth of July parade, her own brief television appearance, lumpy in a leotard, demonstrating how adolescent girls cannot do a full, touch-your-toes sit-up at a certain point during their development. She couldn’t decide what was funnier—her desperation to be on television or the fact that people believed those sit-ups accomplished anything.

But where was Calliope in all of this? The girl-woman who was supposed to be at the center of Cassandra’s story remained a cipher, quiet and self-contained. No matter how hard Cassandra tried to trigger memories of Callie, she was merely there. She didn’t get in trouble, she didn’t not get in trouble. Was there a clue in that? Was she the kind of child who tortured animals? Did she steal? There had been a rash of lunchbox thefts one year, with all the girls’ desserts taken. Was there something in Callie’s home life that had taught her early on that it was better not to attract attention? Cassandra had a vague impression—it couldn’t even be called a memory—of an angry, defensive woman, quick to suspect that she was being mocked or treated unfairly, the kind of woman given to yanking children by the meat of the upper arm, to hissing, You are on my last nerve. She had done that at the birthday party, upon coming to gather Callie. No, wait—Fatima’s mother had picked the two up, and she would not have grabbed another woman’s child that way. Still, Cassandra believed she had witnessed this scene with Callie, not Fatima.

Abuse—inevitable in such a story, but also a little, well, tiresome. She hoped it didn’t turn out to be that simple, abused child grows up to be abusive mother. Hitting the wall of her own memory, but feeling too tentative to press forward in her search for the living, breathing Calliope, she decided to spend an afternoon at the library, researching what others had learned about the adult woman presumed to have murdered her own child.

The Enoch Pratt Central Library had been one of the places where her father brought her on Saturday afternoons, after the separation. That was the paradox of divorce in the sixties—fathers who had never much bothered with their children were suddenly expected to do things with them every other weekend. It was especially awkward in the Fallows family because Ric wanted to involve Annie in their outings and Lennie had expressly prohibited Annie’s participation. Ric defied his estranged wife, setting up fake chance encounters with his girlfriend. At the library, at the zoo, at Westview Cinemas, at the bowling alley on Route 40. Why, look who it is! You couldn’t even say he feigned surprise; it was more as if he feigned feigning. Annie, at least, had the grace to look embarrassed by their transparency. And nervous, with good reason. People were not comfortable with interracial couples in 1968 and not at all shy about expressing their objections.

Cassandra liked Annie. Everyone liked Annie—except, of course, Cassandra’s mother, and it was hard to blame her for that. In fact, the outings were more fun when Annie was along because Annie didn’t give the impression that she felt debased by the things that a ten-year-old found pleasurable. Annie was only twenty-six, and a young twenty-six at that, but her interest in Cassandra was always maternal. She expected to be Cassandra’s stepmother long before anyone else thought this might be possible, including Ric. In his mind, he was having a great romance, and romance was not possible within a marriage.

But Annie assumed she would be his wife. ‘She set her cap for him,’ Cassandra’s mother said with great bitterness, and Cassandra had tried to imagine what such a cap looked like. A nurse’s hat? Something coquettish, with a bow? (She was the kind of ten-year-old who knew words like coquettish.) She imagined the hat that the cinematic Scarlett O’Hara lifted from Rhett Butler’s box, the girl in Hello, Dolly! who wanted to wear ribbons down her back, the mother in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, setting her jade green velvet hat at a jaunty angle. But Cassandra could not imagine round-faced Annie, who wore her hair in a close-cropped ‘natural’, in any kind of hat, much less see her as calculating.