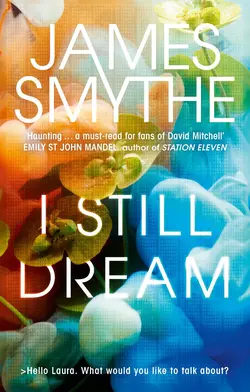

I Still Dream

James Smythe

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Техническая литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1241.52 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘The best fictional treatment of the possibilities and horrors of artificial intelligence that I’ve read’ GuardianIn 1997 Laura Bow invented Organon, a rudimentary artificial intelligence.Now she and her creation are at the forefront of the new wave of technology, and Laura must decide whether or not to reveal Organon’s full potential to the world. If it falls into the wrong hands, its power could be abused. Will Organon save humanity, or lead it to extinction?I Still Dream is a powerful tale of love, loss and hope; a frightening, heartbreakingly human look at who we are now – and who we can be, if we only allow ourselves.