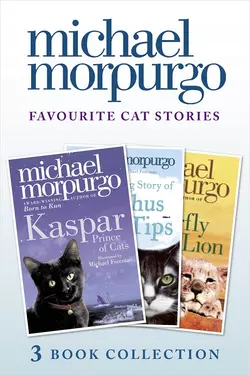

Favourite Cat Stories: The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips, Kaspar and The Butterfly Lion

Michael Morpurgo

Three beautiful tales for all feline-lovers told by the nation’s favourite storyteller including wartime kittens and African lion cubs.‘The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips’:In 1943, Lily Treganza was living in a sleepy seaside village, scarcely touched by the war. But all that was soon to change…‘Kaspar’:Kaspar the cat first came to the Savoy Hotel in a basket – Johnny Trott knows, because he was the one who carried him in. Johnny was a bellboy, you see, and he carried all of Countess Kandinsky's things to her room, including this very special cat!‘The Butterfly Lion’:When Bertie is a little boy, he rescues an orphaned white lion cub from the African veld. They are inseparable until Bertie is sent to boarding school far away in England and the lion is sold to a circus.Bertie swears that one day they will see one another again, but it is the butterfly lion which ensures that their friendship will never be forgotten.

Michael Morpurgo

Favourite Cat Stories:

The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips, Kasper and The Butterfly Lion

Contents

Cover Page (#u30726fbc-6d00-5069-b4eb-d60e163289fd)

Title Page (#uaf21c4cb-0ea3-5e1b-8a9b-a887742413db)

The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips (#u4f0378d0-0cc8-5804-8f23-80f8b6534fd7)

Kasper (#litres_trial_promo)

The Butterfly Lion (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Michael Morpurgo (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

For Ann and Jim Simpson, who brought us to Slapton, and for their family too, especially Atlanta, Harriet and Effie.

Contents

Cover Page (#u0dab48c0-7728-5773-8ec2-c0f1cd5d0d2f)

Title Page (#u4f0378d0-0cc8-5804-8f23-80f8b6534fd7)

Dedication (#ua2d190da-63ab-59cd-8741-c57e641c021f)

Map (#u3babe52a-4cd5-5f75-9483-b2164eaa6d97)

Chapter 1 (#uc8b94c25-3d82-5887-9609-90dd9c7ddf5e)

Friday, September 10

1943 (#uc11e3dfd-6c28-5d38-8423-2a57c5992435)

Sunday, September 12

1943 (#u1e28aaaa-f43c-52f7-a9f1-3b8fae1c7e7d)

Thursday, September 16

1943 (#u2af94275-e730-5145-9aff-5ba12d22cd74)

Friday, September 17

1943 (#u70a469bf-bc53-52f6-a7b5-905a3f1701a4)

Monday, September 20

1943 (#u66d4ae2b-8f87-58b5-b0ec-e69ba52e039a)

Tuesday, October 5

1943 (#ub423cedf-04f3-5146-98c2-5b92bd82a820)

Monday, November 1

1943 (#uaeaff018-e6b2-533c-80c5-65c30dece7c6)

Monday, November 8

1943 (#u7c190636-6bbc-5372-b627-e65eb4153b68)

Saturday, November 13

1943 (#u43a567fd-bfb9-5012-a269-d4d8e0c0d9d8)

Tuesday, November 16

1943 (#u7ca23c31-d67c-5bb5-9ccd-879c902b8cd2)

Tuesday, November 30

1943 (#u0e63200d-cb54-558a-8513-7c497bd12d1f)

Wednesday, December 1

1943 (#u5d075bd9-3e9e-59ef-83a4-b62a37215031)

Wednesday, December 15

1943 (#u58d719e9-eee7-54a2-a8e9-3c2480a47602)

Thursday, December 16

1943 (#ua1450695-c3c5-56ec-b556-9015c7962ab2)

Saturday, December 18

1943 (#u3e30113b-300f-5fba-a0eb-19e9b4967afd)

Thursday, December 23

1943 (#uc20e5f6f-1484-51bc-b3d3-89bbaddfe9fa)

Saturday, December 25

1943 (#u114641eb-92f6-5a40-8be4-339023a16791)

Sunday, December 26

1943 (#uc1323478-f893-5a0e-aa48-d3a96e1cba6b)

Monday, December 27

1943 (#u92a14ea0-42a0-59a1-b57a-cf8f467e2dff)

Tuesday, December 28

1943 (#u1443f353-4dd4-5118-9b92-1a9b6a7599bd)

Thursday, December 30

1943 (#u2660acf1-63b7-550a-8665-1ddbd1630bea)

Friday, December 31

1943 (#u2d5599e0-4f72-5ab2-bde0-8325883fa9d2)

Wednesday, January 12

1944 (#u695e3122-4016-5bf1-ada0-75c26b14d960)

Wednesday, January 19

1944 (#ue8c0c63d-3ccf-5662-a171-4419d62847a4)

Monday, January 24

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday, February 10

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday, February 11

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday, February 24

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday, March 3

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday, March 7

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday, March 8

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday, March 15

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday, March 20

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday, March 29

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday, April 20

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday, April 28

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday, May 1

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday, May 10

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday, May 20

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday, May 22

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday, May 26

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday, June 6

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday, October 5

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday, October 6

1944 (#litres_trial_promo)

Postscript (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

(#ulink_c7e103d1-4890-566e-a259-e2c0f0ef2423)

I first read Grandma’s (#ulink_2e796d47-2946-5089-a516-0d0964554f7d) letter over ten years ago, when I was twelve. It was the kind of letter you don’t forget. I remember I read it over and over again to be sure I’d understood it right. Soon everyone else at home had read it too.

“Well, I’m gobsmacked,” my father said.

“She’s unbelievable,” said my mother.

Grandma rang up later that evening. “Boowie? Is that you, dear? It’s Grandma here.”

It was Grandma who had first called me Boowie. Apparently Boowie was the first “word” she ever heard me speak. My real name is Michael, but she’s never called me that.

“You’ve read it then?” she went on.

“Yes, Grandma. Is it true – all of it?”

“Of course it is,” she said, with a distant echoing chuckle. “Blame it on the cat if you like, Boowie. But remember one thing, dear: only dead fish swim with the flow, and I’m not a dead fish yet, not by a long chalk.”

So it was true, all of it. She’d really gone and done it. I felt like whooping and cheering, like jumping up and down for joy. But everyone else still looked as if they were in a state of shock. All day, aunties and uncles and cousins had been turning up and there’d been lots of tutting and shaking of heads and mutterings.

“What does she think she’s doing?”

“And at her age!”

“Grandpa’s only been dead a few months.”

“Barely cold in his grave.”

And, to be fair, Grandpa had only been dead a few months: five months and two weeks to be precise.

It had rained cats and dogs all through the funeral service, so loud you could hardly hear the organ sometimes. I remember some baby began crying and had to be taken out. I sat next to Grandma in the front pew, right beside the coffin. Grandma’s hand was trembling, and when I looked up at her she smiled and squeezed my arm to tell me she was all right. But I knew she wasn’t, so I held her hand. Afterwards we walked down the aisle together behind the coffin, holding on tightly to one another.

Then we were standing under her umbrella by the graveside and watching them lower the coffin, the vicar’s words whipped away by the wind before they could ever be heard. I remember I tried hard to feel sad, but I couldn’t, and not because I didn’t love Grandpa. I did. But he had been ill with multiple sclerosis for ten years or more, and that was most of my life. So I’d never felt I’d known him that well. When I was little he’d sit by my bed and read stories to me. Later I did the same for him. Sometimes it was all he could do to smile. In the end, when he was really bad, Grandma had to do almost everything for him. She even had to interpret what he was trying to say to me because I couldn’t understand any more. In the last few holidays I spent down at Slapton I could see the suffering in his eyes. He hated being the way he was, and he hated me seeing the way he was too. So when I heard he’d died I was sad for Grandma, of course – they’d been married for over forty years. But in a way I was glad it was finished, for her and for him.

After the burial was over we walked back together along the lane to the pub for the wake, Grandma still clutching my hand. I didn’t feel I should say anything to her in case I disturbed her thoughts. So I left her alone.

We were walking under the bridge, the pub already in sight, when she spoke at last. “He’s out of it now, Boowie,” she said, “and out of that wheelchair too. God, how he hated that wheelchair. He’ll be happy again now. You should’ve seen him before, Boowie. You should have known him like I knew him. Strapping great fellow he was, and gentle too, always kind. He tried to stay kind, right to the end. We used to laugh in the early days – how we used to laugh. That was the worst of it in a way; he just stopped laughing a long time ago, when he first got ill. That’s why I always loved having you to stay, Boowie. You reminded me of how he had been when he was young. You were always laughing, just like he used to in the old days, and that made me feel good. It made Grandpa feel good too. I know it did.”

This wasn’t like Grandma at all. Normally with Grandma I was the one who did the talking. She never said much, she just listened. I’d confided in her all my life. I don’t know why, but I found I could always talk to her easily, much more easily than with anyone at home. Back home, people were always busy. Whenever I talked to them I’d feel I was interrupting something. With Grandma I knew I had her total attention. She made me feel I was the only person in the world who mattered to her.

Ever since I could remember I’d been coming down to Slapton for my holidays, mostly on my own. Grandma’s bungalow was more of a home to me than anywhere, because we’d moved house often – too often for my liking. I’d just get used to things, settle down, make a new set of friends and then we’d be off, on the move again. Slapton summers with Grandma were regular and reliable and I loved the sameness of them, and Harley in particular.

Grandma used to take me out in secret on Grandpa’s beloved motorbike, his pride and joy, an old Harley-Davidson. We called it Harley. Before Grandpa became ill they would go out on Harley whenever they could, which wasn’t often. She told me once those were the happiest times they’d had together. Now that he was too ill to take her out on Harley, she’d take me instead. We’d tell Grandpa all about it, of course, and he liked to hear exactly where we’d been, what field we’d stopped in for our picnic and how fast we’d gone. I’d relive it for him and he loved that. But we never told my family. It was to be our secret, Grandma said, because if anyone back home ever got to know she took me out on Harley they’d never let me come to stay again. She was right too. I had the impression that neither my father (her own son) nor my mother really saw eye to eye with Grandma. They always thought she was a bit stubborn, eccentric, irresponsible even. They’d be sure to think that my going out on Harley with her was far too dangerous. But it wasn’t. I never felt unsafe on Harley, no matter how fast we went. The faster the better. When we got back, breathless with excitement, our faces numb from the wind, she’d always say the same thing: “Supreme, Boowie! Wasn’t that just supreme?”

When we weren’t out on Harley, we’d go on long walks down to the beach and fly kites, and on the way back we’d watch the moorhens and coots and herons on Slapton Ley. We saw a bittern once. “Isn’t that supreme?” Grandma whispered in my ear. Supreme was always her favourite word for anything she loved: for motorbikes or birds or lavender. The house always smelt of lavender. Grandma adored the smell of it, the colour of it. Her soap was always lavender, and there was a sachet in every wardrobe and chest of drawers – to keep moths away, she said.

Best of all, even better than clinging on to Grandma as we whizzed down the deep lanes on Harley, were the wild and windy days when the two of us would stomp noisily along the pebble beach of Slapton Sands, clutching on to one another so we didn’t get blown away. We could never be gone for long though, because of Grandpa. He was happy enough to be left on his own for a while, but only if there was sport on the television. So we would generally go off for our ride on Harley or on one of our walks when there was a cricket match on, or rugby. He liked rugby best. He had been good at it himself when he was younger, very good, Grandma said proudly. He’d even played for Devon from time to time – whenever he could get away from the farm, that is.

Grandma had told me a little about the busy life they’d had before I was born, up on the farm – she’d taken me up there to show me. So I knew how they’d milked a herd of sixty South Devon cows and that Grandpa had gone on working as long as he could. In the end, as his illness took hold and he couldn’t go up and down stairs any more, they’d had to sell up the farm and the animals and move into the bungalow down in Slapton village. Mostly, though, she’d want to talk about me, ask about me, and she really wanted to know, too. Maybe it was because I was her only grandson. She never seemed to judge me either. So there was nothing I didn’t tell her about my life at home or my friends or my worries. She never gave advice, she just listened.

Once, I remember, she told me that whenever I came to stay it made her feel younger. “The older I get,” she said, “the more I want to be young. That’s why I love going out on Harley. And I’m going to go on being young till I drop, no matter what.”

I understood well enough what she meant by “no matter what”. Each time I’d gone down in the last couple of years before Grandpa died she had looked more grey and weary. I would often hear my father pleading with her to have Grandpa put into a nursing home, that she couldn’t go on looking after him on her own any longer. Sometimes the pleading sounded more like bullying to me, and I wished he’d stop. Anyway, Grandma wouldn’t hear of it. She did have a nurse who came in to bath Grandpa each day now, but Grandma had to do the rest all by herself, and she was becoming exhausted. More and more of my walks along the beach were alone nowadays. We couldn’t go out on Harley at all. She couldn’t leave Grandpa even for ten minutes without him fretting, without her worrying about him. But after Grandpa was in bed we would either play Scrabble, which she would let me win sometimes, or we’d talk on late into the night – or rather I would talk and she would listen. Over the years I reckon I must have given Grandma a running commentary on just about my entire life, from the first moment I could speak, all the way through my childhood.

But now, after Grandpa’s funeral, as we walked together down the road to the pub with everyone following behind us, it was her turn to do the talking, and she was talking about herself, talking nineteen to the dozen, as she’d never talked before. Suddenly I was the listener.

The wake in the pub was crowded, and of course everyone wanted to speak to Grandma, so we didn’t get a chance to talk again that day, not alone. I was playing waiter with the tea and coffee, and plates of quiches and cakes. When we left for home that evening Grandma hugged me especially tight, and afterwards she touched my cheek as she’d always done when she was saying good night to me before she switched off the light. She wasn’t crying, not quite. She whispered to me as she held me. “Don’t you worry about me, Boowie dear,” she said. “There’s times it’s good to be on your own. I’ll go for rides on Harley – Harley will help me feel better. I’ll be fine.” So we drove away and left her with the silence of her empty house all around her.

A few weeks later she came to us for Christmas, but she seemed very distant, almost as if she were lost inside herself: there, but not there somehow. I thought she must still be grieving and I knew that was private, so I left her alone and we didn’t talk much. Yet, strangely, she didn’t seem too sad. In fact she looked serene, very calm and still, a dreamy smile on her face, as if she was happy enough to be there, just so long as she didn’t have to join in too much. I’d often find her sitting and gazing into space, remembering a Christmas with Grandpa perhaps, I thought, or maybe a Christmas down on the farm when she was growing up.

On Christmas Day itself, after lunch, she said she wanted to go for a walk. So we went off to the park, just the two of us. We were sitting watching the ducks on the pond when she told me. “I’m going away, Boowie,” she said. “It’ll be in the New Year, just for a while.”

“Where to?” I asked her.

“I’ll tell you when I get there,” she replied. “Promise. I’ll send you a letter.”

She wouldn’t tell me any more no matter how much I badgered her. We took her to the station a couple of days later and waved her off. Then there was silence. No letter, no postcard, no phone call. A week went by. A fortnight. No one else seemed to be that concerned about her, but I was. We all knew she’d gone travelling, she’d made no secret of it, although she’d told no one where she was going. But she had promised to write to me and nothing had come. Grandma never broke her promises. Never. Something had gone wrong, I was sure of it.

Then one Saturday morning I picked up the post from the front door mat. There was one for me. I recognised her handwriting at once. The envelope was quite heavy too. Everyone else was soon busy reading their own post, but I wanted to open Grandma’s envelope in private. So I ran upstairs to my room, sat on the bed and opened it. I pulled out what looked more like a manuscript than a letter, about thirty or forty pages long at least, closely typed. On the cover page she had sellotaped a black and white photograph (more brown and white really) of a small girl who looked a lot like me, smiling toothily into the camera and cradling a large black and white cat in her arms. There was a title: The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips, with her name underneath, Lily Tregenza. Attached to the manuscript by a large multicoloured paperclip was this letter.

Dearest Boowie,

This is the only way I could think of to explain to you properly why I’ve done what I’ve done. I’ll have told you some of this already over the years, but now I want you to know the whole story. Some people will think I’m mad, perhaps most people—I don’t mind that. But you won’t think I’m mad, not when you’ve read this. You’ll understand, I know you will. That’s why I particularly wanted you to read it first. You can show it to everyone else afterwards. I’ll phone soon…when you’re over the surprise.

When I was about your age—and by the way that’s me on the front cover with Tips—I used to keep a diary. I was an only child, so I’d talk to myself in my diary. It was company for me, almost like a friend. So what you’ll be reading is the story of my life as it happened, beginning in the autumn of 1943, during the Second World War, when I was growing up on the family farm. I’ll be honest with you, I’ve done quite a lot of editing. I’ve left bits out here and there because some of it was too private or too boring or too long. I used to write pages and pages sometimes, just talking to myself, rambling on.

The surprise comes right at the very end. So don’t cheat, Boowie. Don’t look at the end. Let it be a surprise for you—as it still is for me.

Lots of love,

Grandma

PS Harley must be feeling very lonely all on his own in the garage. We’ll go for a ride as soon as I get back; as soon as you come to visit. Promise.

Friday, September 10

1943 (#ulink_7ae35e80-cca8-5ea0-8fce-47952eb26d57)

I’ve been back at school a whole week now. When Miss McAllister left at the end of last term I was cock-a-hoop (I like that word), we all were. She was a witch, I’m sure she was. I thought everything would be tickety-boo (I like that word too) just perfect, and I was so much looking forward to school without her. And who do we get as a head teacher instead? Mrs “Bloomers” Blumfeld. She’s all smiles on the outside, but underneath she’s an even worser witch than Miss McAllister. I know I’m not supposed to say worser but it sounds worser than worse, so I’m using it. So there. We call her Bloomers because of her name of course, and also because she came into class once with her skirt hitched up by mistake in her navy-blue bloomers.

Today Bloomers gave me a detention just because my hands were dirty again. “Lily Tregenza, I think you are one of the most untidiest girls I have ever known.” She can’t even say her words properly. She says zink instead of think and de instead of the. She can’t even speak English properly and she’s supposed to be our teacher. So I said it wasn’t fair, and she gave me another detention. I hate her accent; she could be German. Maybe she’s a spy! She looks like a spy. I hate her, I really do. And what’s more, she favours the townies, the evacuees. That’s because she’s come down from London like they have. She told us so.

We’ve got three more townies in my class this term, all from London like the others. There’s so many of them now there’s hardly enough room to play in the playground. There’s almost as many of them as there are of us. They’re always fighting too. Most of them are all right, I suppose, except that they talk funny. I can’t understand half of what they say. And they stick together too much. They look at us sometimes like we’ve got measles or mumps or something, like they think we’re all stupid country bumpkins, which we’re not.

One of the new ones – Barry Turner he’s called – is living in Mrs Morwhenna’s house, next to the shop. He’s got red hair everywhere, even red eyebrows. And he picks his nose which is disgusting. He gets lots more spellings wrong than me, but Bloomers never gives him a detention. I know why too. It’s because Barry’s dad was killed in the airforce at Dunkirk. My dad’s away in the army, and he’s alive. So just because he’s not dead, I get a detention. Is that fair? Barry told Maisie, who sits next to me in class now and who’s my best friend sometimes, that she could kiss him if she wanted to. He’s only been at our school a week. Cheeky monkey. Maisie said she let him because he’s young – he’s only ten – and because she was sorry for him, on account of his dad, and also because she wanted to find out if townies were any good at it. She said it was a bit sticky but all right. I don’t do kissing. I don’t see the point of it, not if it’s sticky.

Tips is going to have her kittens any day now. She’s all saggy baggy underneath. Last time she had them on my bed. She’s the best cat (and the biggest) in the whole wide world and I love her more than anyone or anything. But she keeps having kittens, and I wish she wouldn’t because we can’t ever keep them. No one wants them because everyone’s got cats of their own already, and they all have kittens too.

It was all because of Tips and her kittens that I had my row with Dad, the biggest row of my life, when he was last home on leave from the army. He did it when I was at school, without even telling me. As soon as they were born he took all her kittens out and drowned them just like that. When I found out I said terrible things to him, like I would never ever speak to him again and how I hoped the Germans would kill him. I was horrible to him. I never made it up with him either. I wrote him a letter saying I was sorry, but he hasn’t replied and I wish he would. He probably hates me now, and I wouldn’t blame him. If anything happened to him I couldn’t bear it, not after what I said.

Mum keeps telling me I shouldn’t let my tongue do my thinking for me, and I’m not quite sure what that means. She’s just come in to say good night and blow out my lamp. She says I spend too much time writing my diary. She thinks I can’t write in the dark, but I can. My writing may look a bit wonky in the morning, but I don’t care.

Sunday, September 12

1943 (#ulink_d4c27396-2bda-5268-bbb0-38cb19af87bd)

We saw some American soldiers in Slapton today; it’s the first time I’ve ever seen them. Everyone calls them Yanks, I don’t know why. Grandfather doesn’t like them, but I do. I think they’ve got smarter uniforms than ours and they look bigger somehow. They smiled a lot and waved – particularly at Mum, but that was just because she’s pretty, I could tell. When they whistled she went very red, but she liked it. They don’t say “hello”, they say “hi” instead, and one of them said “howdy”. He was the one who gave me a sweet, only he called it “candy”. I’m sucking it now as I’m writing. It’s nice, but not as nice as lemon sherberts or peppermint humbugs with the stripes and chewy centres. Humbugs are my best favourites, but I’m only allowed two a week now because of rationing. Mum says we’re really lucky living on the farm because we can grow our own vegetables, make our own milk and butter and cream and eat our own chickens. So when I complain about sweet rationing, which I do, she always gives me a little lecture on how lucky we are. Barry says they’ve got rationing for everything in London, so maybe Mum is right. Maybe we are lucky. But I still don’t see how me having less peppermint humbugs is going to help us win the war.

Thursday, September 16

1943 (#ulink_1e07bb38-8b66-5769-9a1c-d56e46c5e364)

Mum got a letter from Dad today. Whenever she gets a letter she’s very happy and sad at the same time. She says he’s out in the desert in Africa with the Eighth Army and he’s making sure the lorries and the tanks work – he’s very good at engines, my dad. It’s very hot in the daytime, he says, but at night it’s cold enough to freeze your toes off. Mum let me read the letter after she had. He didn’t say anything about Tips and the kittens or the row we had. Maybe he’s forgotten all about it. I hope so.

I feel bad about writing this, but I must write what I really feel. What’s the point in writing at all otherwise? The truth is, I don’t really miss Dad like I know I should, like I know Mum does. When I’m actually reading his letters I miss him lots, but then later on I forget all about him unless someone talks about him, unless I see his photo maybe. Perhaps it’s because I’m still cross with him about the kittens. But it’s not just because of the kittens that I’m cross with him. The thing is, he didn’t need to go to fight in the war; he could have stayed with us and helped Grandfather and Mum on the farm. Other farmers were allowed to stay. He could have. But he didn’t. He tried to explain it to me before he joined up. He said he wouldn’t feel right about staying home when there were so many men going off to the war, men the same age as he was. I told him he should think of Grandfather and Mum and me, but he wouldn’t listen. They’ve got to do all the work on their own now, all the milking and the muck spreading, all the haymaking and the lambing. Dad was the only one who could fix his Fordson tractor and the thresher, and now he’s not here to do it. I help out a bit, but I’m not much use. I’m only twelve (almost anyway) and I’m off to school most days. He should be here with us, that’s what I think. I’m fed up with him being away. I’m fed up with this war. We’re not allowed down on the beach any more to fly our kites. There’s barbed wire all around it to keep us off, and there’s mines buried all over it. They’ve put horrible signs up everywhere warning us off. That wasn’t much use to Farmer Jeffrey’s smelly old one-eyed sheepdog that lifted his leg on everything he passed (including my leg once). He wandered on to the beach under the wire yesterday and blew himself up. Poor old thing.

I had this idea at school (probably because Bloomers was reading us the King Arthur stories). I think we should dress Churchill and Hitler up in armour like King Arthur’s knights, stick them on horses, give them a lance each and let them sort it out between them. Whoever is knocked off loses, and the war would be over and we could all go back to being normal again. Churchill would win of course, because Hitler looks too weak and feeble even to sit on a horse, let alone hold a lance. So we would win. No more rationing. All the humbugs I want. Dad could come home and everything would be like it was before. Everything would be tickety-boo.

Friday, September 17

1943 (#ulink_1c003910-1abd-5765-9cb0-9e42ac53a48b)

I saw a fox this morning running across south field with a hen in his mouth. When I shouted at him, he stopped and looked at me for a moment as if he was telling me to mind my own business. Then he just trotted off, cool as you like, without a care in the world. Mum says it wasn’t one of her hens, but she was someone’s hen, wasn’t she? Someone should tell that fox about rationing. That’s what I think.

There’s lots of daddy-longlegs crawling up my window, and a butterfly. I’ll just let them out…

It’s still light outside. I love light evenings. It was a red admiral butterfly. Beautiful. Supreme.

Mum and Grandfather are having an argument downstairs, I can hear them. Grandfather is going on about the American soldiers again, “ruddy Yanks” he calls them. He says they’re all over the place, hundreds of them, and walking about as if they own the place, smoking cigars, chewing gum. Like an invasion, he says. Mum speaks more quietly than Grandfather, so it’s difficult to hear what she’s saying.

They’ve stopped arguing now. They’ve got the radio on instead. I don’t know why they bother. The news of the war is always bad, and it only makes them feel miserable. It’s hardly ever off, that radio.

Monday, September 20

1943 (#ulink_1ced2183-8d76-5660-8d9a-36f67eafc602)

Two big surprises. One good, one bad. We were all sent home from school today. That was the good one. It was all because of Mr Adolf Ruddy Hitler, as Grandfather calls him. So thanks for the holiday, Mr Adolf Ruddy Hitler. We were sitting doing arithmetic with Bloomers – long division which I can’t understand no matter how hard I try – when we heard the roaring and rumbling of an aeroplane overhead, getting louder and louder, and the classroom windows started to rattle. Then there was this huge explosion and the whole school shook. We all got down on the floor and crawled under the desks like we have to do in air-raid practice, except this was very much more exciting because it was real. By the time Bloomers had got us out into the playground the German bomber was already far out over the sea. We could see the black crosses on its wings. Barry pretended he was firing an ack-ack gun and tried to shoot it down. Most of the boys joined in, making their silly machine-gun noises – dadadadadada.

Bloomers sent us home just in case there were more bombers on the way. But we didn’t go home. Instead we all went off to see if we could find where the bomb had landed. We found it too. There was a massive hole in Mr Berry’s cornfield just outside the village. The Home Guard was there already, Uncle George in his uniform telling them all what to do. They were making sure no one fell in, I suppose. No one had been hurt, except a poor old pigeon who was probably having a good feed of corn when the bomb fell. His feathers were everywhere. Then one of the townies got all hoity-toity about it and said he’d seen much bigger holes than this one back home, in London. Big Ned Simmons told him just where he could go and just what he thought of him and all the snotty-nosed townies, and it all got a bit nasty after that, us against them. So I walked away.

I was on my way home afterwards when I saw this jeep coming down the lane towards me. There was one soldier in it. He had an American helmet on. He screeched to a stop and said, “Hi there!” He was a black man. I’ve never in my life seen a black person before, only in pictures in books, so I didn’t quite know what to say. I kept trying not to stare, but I couldn’t help myself. He had to ask me twice if he was on the right road to Torpoint before I even managed a nod. “You know something? You got pigtails just like my littlest sister.” Then he said, “See ya!” and off he went, splashing through the puddles. I was a bit disappointed not to get any candy.

When I got home I had my other surprise, my bad one. I told them about the bomb and about Uncle George and the Home Guard being there, and I told them about the black soldier I’d met in the lane. They didn’t seem very interested in any of it. I thought that was strange. And it was strange too that neither of them seemed to want to talk to me much or even to look at me. We were all having tea in the kitchen when Tips came in. She rubbed herself against my leg and then went off mewing under the table, under the dresser, into the pantry. But she wasn’t mewing like she does when she’s after food or love, or when she brings in a mouse. She was calling, and when I picked her up she felt different. Still saggy baggy underneath, but definitely different. She wasn’t full and fat any more. I knew what they’d done at once.

“We had to do it, Lily,” Mum said. “It’s better straight away, before she gets too fond of them. Sometimes you have to be cruel to be kind.”

I screamed at them: “Murderers! Murderers!” Then I brought Tips up to my room. I’m still up here with her now. I’ve been crying ever since, and really loudly too so they can hear me, so they’ll feel really bad, as bad as I do.

Tips is lying in my lap and washing herself just like nothing’s happened. She’s even purring. Maybe she doesn’t know yet. Or maybe she does and she’s forgiven us already. Now she’s stopped licking herself. She’s looking at me as if she knows. I don’t think she has forgiven us. I don’t think she’ll ever forgive us. Why should she?

Tuesday, October 5

1943 (#ulink_71f70291-c51d-5dbe-a0bd-860a0ca86fcf)

My birthday. I was born twelve years ago today at ten o’clock in the morning. I’ve been calling myself twelve for a long time, and now I really am. All I want to be now is thirteen. And even thirteen isn’t old enough. I so much want to be much older than I am, but not old like Grandfather so that I walk bent and my hands are all hard and wrinkly and veiny. I don’t want a drippy nose and hairs growing out of my ears. But I do want the years to hurry on by until I’m about seventeen, so school and Bloomers and long division are over and done with, so that no one can take my kittens away and drown them. It’ll be so good when I’m seventeen, because the war will be over by then, that’s for sure. Grandfather says that we’re already winning and so it can’t be long till it’s finished. Then I can go up to London on the train – I’ve never been on a train – and I can see the shops and ride on those big red buses and go on the underground. Barry Turner’s told me all about it. He says there’s lights in the streets, millions of people everywhere, and cinemas and dance halls. His dad used to work in a cinema before the war, before he was killed. He told me that one day. That was the first thing he’s ever told me about his dad.

Which reminds me: I still haven’t had a letter from my dad. I think he’s still cross with me after what I said. I wish, I wish I hadn’t said it. I had a dream about him the other night. I don’t usually remember my dreams at all, but I remember this one, some of it anyway. He was back at home milking cows again, but he was in uniform with his tin helmet on. It was scary because, when I came into the milking parlour, I spoke to him and he never looked up. I shouted but he still never looked at me. It was like one of us wasn’t there, but we were. We both were.

Monday, November 1

1943 (#ulink_fa0b6b03-81f9-5b0b-a380-c586b1250329)

“Pinch, punch, first day of the month. Slap and a kick for being so quick. Punch in the eye for being so sly.” Barry kept saying it to me every time he saw me. It was really annoying. In the end I shouted at him and hurt his feelings. I know I shouldn’t have, he was only trying to be friendly. He didn’t cry but he nearly did.

But tonight I feel worse about something else, something much worse. Ever since Bloomers came I’ve been giving her a hard time, we all have, but me most of all. I’m really good at giving people a hard time when I want to. I cheeked her when she first came because I didn’t like her and she got ratty and punished me. So I cheeked her again and she punished me again and on it went, and after that I could never get on with her at all. I’ve been mean to her ever since I’ve known her, and now this has happened.

The vicar came into school today and told us he’d be teaching us for the morning because Mrs Blumfeld wasn’t feeling very well. She wasn’t ill so much as sad, he said, sad because she had just heard the news that her husband, who is in the merchant navy, had been lost at sea in the Atlantic. His ship had been torpedoed. They’d picked up a few survivors, but Mrs Blumfeld’s husband wasn’t one of them. The vicar told us that when she came back into school we had to be very good and kind, so as not to upset her. Then he said we should close our eyes and hold our hands together and pray for her. I did pray for her too, but I also prayed for myself, because I don’t want God to have his own back on me for all the horrible things I’ve said and thought about her. I prayed for my dad too, that God wouldn’t make him die in the desert just because I’d been mean to Mrs Blumfeld, that I hadn’t meant it when I’d said I wanted him to die because he drowned the kittens. I’ve never prayed so hard in my life. Usually my mind wanders when I’m supposed to be praying, but it didn’t today.

After lunch Mrs Blumfeld came into school. She had no lipstick on. She looked so pale and cold. She was trembling a little too. We left a letter for her on her desk which we had all signed, to say how sorry we all were about her husband. She looked very calm, as if she was in a daze. She wasn’t crying or anything, not until she read our letter. Then she tried to smile at us through her tears and said it was very thoughtful of us, which it wasn’t because it was the vicar’s idea, but we didn’t tell her that. We all went around whispering and being extra good and quiet all day. I feel so bad for her now because she’s all alone. I won’t call her Bloomers ever again. I don’t think anyone will.

Monday, November 8

1943 (#ulink_9c1303d3-8c02-5ebc-acf5-fc3b5461ae41)

Ever since Mrs Blumfeld’s husband was killed, I’ve been worrying a lot about Dad. I didn’t before, but I am now, all the time. I keep thinking of him lying dead in the sand of Africa. I try not to, but the picture of him lying there keeps coming into my head. And it’s silly, I know it is, because I got a letter from him only yesterday, at last, and he’s fine. (His letters take for ever to come. This one was dated two months ago.) He never said anything about me being cross. In fact he sent his love to Tips. Dad says it’s so hot out in the desert he could almost fry an egg on the bonnet of his jeep. He says he longs for a few days of good old Devon drizzle, and mud. He really misses mud. How can you miss mud? We’re all sick of mud. It’s been raining here for days now: mizzly, drizzly, horrible rain. Today it was blowing in from the sea, so I was wet through by the time I got home from school.

Grandfather came in later. He’d been drinking a bit, but then he always drinks a bit when he goes to market, just to keep the cold out, he says. He sat down in front of the stove and put his feet in the bottom oven to warm up. Mum hates him doing it but he does it all the same. He’s got holes in his socks too. He always has.

“There’s hundreds of gum-chewing Yanks everywhere in town,” he said. “Like flies on a ruddy cow clap.” I like it when Grandfather talks like that. He got a dirty look from Mum, but he didn’t mind. He just gave me a big wink and a wicked grin and went on talking. He said he was sure something’s going on: there are fuel dumps everywhere you look, tents going up all over the place, tanks and lorries parked everywhere. “It’s something big,” he said. “I’m telling you.”

Still raining out there. It’s lashing the windowpanes as I’m writing, and the whole house is creaking and shaking, almost as if it’s getting ready to take off and fly out over the sea. I can hear the cows lowing in the barn. They’re scared. Tips is frightened silly too. She wants to hide. She keeps jogging my writing. She’s trying to push her head deeper and deeper into my armpit. I’m not frightened, I like storms. I like it when the sea comes thundering in and the wind blows so hard that it takes your breath away.

Mrs Blumfeld said something this morning that took my breath away too. That Daisy Simmons, Ned’s little sister, is always asking questions when she shouldn’t and today she put her hand up and asked Mrs Blumfeld if she was a mummy, just like that! Mrs Blumfeld didn’t seem to mind at all. She thought for a bit, then she said that she would never have any children of her own because she didn’t need them; she had all of us instead. We were her family now. And she had her cats, which she loved. I didn’t know she had cats. I was watching her when she said it and you could see she really did love them. I was so wrong about her. She likes cats so she must be nice. I’m going to sleep now and I’m not going to think of Dad lying out in the desert. I’m going to think of Mrs Blumfeld at home with her cats instead.

I just went to shut the window, and I saw a barn owl flying across the farmyard, white and silent in the darkness. There one moment, gone the next. A ghost owl. He’s screeching now. They screech, they don’t toowit-toowoo. That word looks really funny when you write it down, but owls don’t have to write it down, do they? They just have to hoot it, or toowit-toowoo it.

Saturday, November 13

1943 (#ulink_c5b5e326-d585-5287-9324-451e2182b517)

Today was a day that will change my life for ever. Grandfather was right when he said something was up. And it is something big too, something very big – I have to keep pinching myself to believe it’s true, that it’s really going to happen. Yesterday was just like any other day. Rain. School. Long division. Spelling test. Barry picking his nose. Barry smiling at me from across the classroom with his big round eyes. I just wish he wouldn’t smile at me so. He’s always so smiley.

Then today it happened. I knew all day there was going to be some kind of meeting in the church in the evening, that someone from every house had to go and it was important. I knew that, because Mum and Grandfather were arguing about it over breakfast before I went off to school. Grandfather was being a grumpy old goat. He’s been getting crotchety a lot just lately. (Mum says it’s because of his rheumatism – it gets worse in damp weather.) He kept saying he had too much to do on the farm to be bothered with meetings and such. And besides, he said, women were better at talking because they did more of it. Of course that made Mum really mad, so they had a fair old dingdong about it. Anyway in the end Mum gave in and said she’d go, and she asked me to go along with her for company. I didn’t want to go but now I’m glad I did, really glad.

The place was packed out. There was standing room only by the time we got there. Then this bigwig, Lord Somethingorother, got up and started talking. I didn’t pay much attention at first because he had this droning-on hoity-toity (I like that word) sort of voice that almost put me to sleep. But suddenly I felt a strange stillness and silence all around me. It was almost as if everyone had stopped breathing. Everyone was listening, so I listened too. I can’t remember his exact words, but I think it went something like this.

“I know it’s asking a lot of you,” the bigwig was saying, “but I promise we wouldn’t be asking you if we didn’t have to, if it wasn’t absolutely necessary. They’ll be needing the beach at Slapton Sands and the whole area behind it, including this village. They need it because they have to practise landings from the sea for the invasion of France when it comes. That’s all I can tell you. Everything else is top secret. No point in asking me anything about it, because I don’t know any more than you do. What I do know is that you have seven weeks from today to move out, lock, stock and barrel – and I mean that. You have to take everything with you: furniture, food, coal, all your animals, farm machinery, fuel, and all fodder and crops that can be carried. Nothing you value must be left behind. After the seven weeks is up, no one will be allowed back – and I mean no one. There’ll be a barbed-wire perimeter fence and guards everywhere to keep you out. Besides which, it will be dangerous. There’ll be live firing going on: real shells, real bullets. I know it’s hard, but don’t imagine it’s just Slapton, that you’re the only ones. Torcross, East Allington, Stokenham, Sherford, Chillington, Strete, Blackawton: 3000 people have got to move out; 750 families, 30,000 acres of land have got to be cleared in seven weeks.”

Some people tried to stand up and ask questions, but it was no use. He just waved them down.

“I’ve told you. It’s no good asking me the whys and wherefores. All I know is what I’ve told you. They need it for the war effort, for training purposes. That’s all you need to know.”

“Yes, but for how long?” asked the vicar from the back of the hall.

“About six months, nine months, maybe longer. We can’t be sure. And don’t worry. We’ll make sure everyone has a place to live, and of course there’ll be proper compensation paid to everyone, to all the farms and businesses for any loss or damage. And I have to be honest with you here, I have to warn you that there will be damage, lots of it.”

You could have heard a pin drop. I was expecting lots of protests and questions, but everyone seemed to be struck dumb. I looked up at Mum. She was staring ahead of her, her mouth half open, her face pale. All the way home in the dark, I kept asking her questions, but she never said a word till we reached the farmyard.

“It’ll kill him,” she whispered. “Your grandfather. It’ll kill him.”

Once back home she came straight out with it. Grandfather was in his chair warming his toes in the oven as usual. “We’ve got to clear out,” she said, and she told him the whole thing. Grandfather was silent for a moment or two. Then he just said, “They’ll have to carry me out first. I was born here and I’ll die here. I’m not moving, not for they ruddy Yanks, not for no one.” Mum’s still downstairs with him, trying to persuade him. But he won’t listen. I know he won’t. Grandfather doesn’t say all that much, but what he says he means. What he says, he sticks to. Tips has jumped up on my bed and walked all over my diary with her muddy paws! She’s lucky I love her as much as I do.

Tuesday, November 16

1943 (#ulink_bf81e76c-11d6-5262-9b38-a8f29ea640d9)

At school, in the village, no matter where you go or whoever you meet, it’s all anyone talks about: the evacuation. It’s like a sudden curse has come down on us all. No one smiles. No one’s the same. There’s been a thick fog ever since we were told. It hangs all around us, tries to come in at the windows. It makes me wonder if it’ll ever go away, if we’ll ever see the sun again.

I’ve changed my mind completely about Barry. That skunkhead Bob Bolan came up to me at playtime and started on about Grandfather, just because he’s the only one in the village refusing to go. He said he was a stupid old duffer. He said he should be sent away to a lunatic asylum and locked up. Maisie was there with me and she never stood up for me, and I thought she was supposed to be my best friend. Well she’s not, not any more. No one stood up for me, so I had to stand up for myself. I pushed Skunkhead (I won’t call him Bob any more because Skunkhead suits him better) and Skunkhead pushed me, and I fell over and grazed my elbow. I was sitting there, picking the grit out of my skin and trying not to let them see I was crying, when Barry came up. The next thing I know he’s got Skunkhead on the ground and he’s punching him. Mrs Blumfeld had to pull him off, but not before Skunkhead got a bleeding nose, which served him right. As she took them both back into school Barry looked over his shoulder and smiled. I never got a chance to say thank you, but I will. If only he’d stop picking his nose and smiling at me I think I could really like him a lot. But I’m not doing kissing with him.

Tuesday, November 30

1943 (#ulink_ba4a9482-ebe3-5fd8-b6cd-f89272d92250)

Some people have started moving their things out already. This morning I saw Maisie’s dad going up the road with a cartload of beds and chairs, cupboards, tea chests and all sorts. Maisie was sitting on the top and waving at me. She’s my friend again, but not my best friend. I think Barry’s my best friend now because I know I can really trust him. Then I saw Miss Langley driving off in a car with lots of cases and trunks strapped on top. She had Jimbo on her lap, her horrible Jack Russell dog who chases Tips up trees whenever he sees her. Mum told me that Miss Langley is off to stay with a cousin up in Scotland, hundreds of miles away. I’ve just told Tips and suddenly she’s purring very happily. It’s a “good riddance” purr, I think.

A lot of people are going to stay with relatives, and we could too except that Grandfather won’t hear of it. Uncle George farms only a couple of miles away, just beyond where the wire fence will be. They’re beginning to put it up already. He said that family’s family, and he’d be only too happy to help us out. I heard him telling Grandfather. We could take our milking cows up to his place, all our sheep, all the farm machinery, Dad’s Fordson tractor, everything. It’ll be a tight squeeze, Uncle George said, but we could manage. Grandfather won’t listen. He won’t leave, and that’s that.

Wednesday, December 1

1943 (#ulink_f2ed4c02-0d16-552e-b5ea-fcc903fedaef)

At playtime I found Barry sitting on his own on the dustbins behind the bike shed. He was all red around the eyes. He’d been crying, but he was trying not to show it. He wouldn’t tell me why at first, but after a while I got it out of him. It’s because there won’t be room for him any more with Mrs Morwhenna when she moves into Kingsbridge next week. He likes her a lot and now he has nowhere to go. So, to make him feel better, and because of what he had done for me the other day with Skunkhead, I said he could come home with me and play after school, so long as he didn’t pick his nose. He perked up after that, and he was even chirpier when he saw the cows and the sheep. And when he saw Dad’s Fordson tractor he went loopy. It was like he’d been given a new toy of his own to play with. I couldn’t get him off it. Grandfather took him off around the farm, letting him steer the tractor – which wasn’t fair because he’s never let me do that.

By the time they came back they were both of them as happy as larks. I haven’t heard Grandfather laugh so much in ages. Barry tucked into Mum’s cream sponge cake, slice after slice of it, and all the time he never stopped talking about the tractor and the farm (and no one told him not to talk with his mouth full, which wasn’t fair either because Mum’s always ticking me off for that). He’d have scoffed the lot if Mum hadn’t taken it away. He still smiles at me, but I don’t mind so much now. In fact I quite like it really.

Afterwards, when we were walking together down the lane to the farm gate, he seemed suddenly down in the dumps. He hardly said a word all the way. Then suddenly he just blurted it out. “I could come and stay,” he said. “I wouldn’t be a nuisance, honest. I wouldn’t pick my nose, honest.” I couldn’t say no, but I didn’t want to say yes, not exactly. I mean, it would be like having a brother in the house. I’d never had a brother and I wasn’t sure I wanted one, even if Barry was my best friend now, sort of. So I said maybe. I said I’d ask. And I did, at supper time. Grandfather didn’t even have to think about it. “The lad needs a home, doesn’t he?” he said. “We’ve got a home. He needs feeding. We’ve got food. We should have had one of those evacuee children before, but I never liked townies much till now. This one’s all right though. He’s a good lad. Besides, it’ll be good to have a boy about the place. Be like the old days, when your father was a boy. You tell him he can come.”

He never asked me what I thought, never asked Mum. He just said yes. It took me so much by surprise that I wasn’t ready for it, and neither was Mum. So it looks as if I’m going to have a sort of brother living with us, whether I like it or not. Mum came in a minute ago and sat on my bed. “Do you mind about Barry?” she asked me.

“He’s all right, I suppose,” I told her. And he is too, except when he’s picking his nose of course.

“One thing’s for sure, it’ll make Grandfather happier,” Mum said. “And if he’s happier, then maybe it’ll be easier to talk him into leaving, into moving to Uncle George’s place. They’re going to move us out, you know, Lily. One way or another, they’re going to do it.” She gave me a good long cuddle tonight. She hasn’t done that for ages. I think she thinks I’m too old for it or something, but I’m not.

I haven’t had my nightmare about Dad for a long time now, which is good. But I haven’t thought much about him either, which is not so good.

Wednesday, December 15

1943 (#ulink_c87a8987-8fe3-5334-a3d7-d0cf01904216)

Barry moved in this afternoon. He walked home with me from school carrying his suitcase. He skipped most of the way. He’s sleeping in the room at the end of the passage. Grandfather says that’s where Dad always used to sleep when he was a boy. Straight after tea Grandfather took him out to feed the cows. From the look on Barry’s face when he came back I’m sure he thinks he’s in heaven. Like he says, there’s no tractors in London, no cows, no sheep, no pigs. He’s already decided he likes the sheep best. And he likes mud too, and he likes rolling down hills and getting his coat covered in sheep poo. He told Mum that brown’s his favourite colour because he likes mud, and sausages. I learnt a little bit more about him today – he tells Mum more than he tells me. But I listen. He didn’t say much about his dad of course, but his mum works on the buses in London, a “clippy”, he says – that’s someone who sells the tickets. That’s about all I know about him so far, except that he twiddles his hair when he’s upset and he doesn’t like cats because they smile at him. He’s a good one to talk. He’s always smiling at me. If he’s living with us, he’d better be nice to Tips, that’s all I can say. He twiddles his hair a lot at school. I’ve noticed it in class, especially when he’s doing his writing. He can’t do his handwriting very well. Mrs Blumfeld tries to help him with his letters and his spelling but he still keeps getting everything back to front. (I think he’s frightened of them – of letters, I mean.) He’s good with numbers though. He doesn’t have to use his fingers at all. He does it all in his head, which I can’t do.

Grandfather’s still telling everyone he’s not going to be moved out. Lots of people have had a go at persuading him, the vicar, Doctor Morrison, even Major Tucker came to see us from the Manor House. But Grandfather won’t budge. He just carries on as if nothing is happening. Half the village has moved out now, including Farmer Gent next door. I saw the last of his machinery being taken away yesterday. All his animals have gone already. They went to market last week. His farmhouse is empty. Usually I can see a light or two on in there from my window, but not any more. It’s dark now, pitch black. It’s like the house has gone too.

We see more and more American soldiers and lorries coming into the village every day. Grandfather’s turning a blind eye to all of it. Barry’s out with him now. They’ve gone milking. I saw them go off together a while ago, stomping across the yard in their wellies. Barry looked like he’d been doing it all his life, as if he’d always lived here, as if he was Grandfather’s grandson. To tell the truth I feel a little jealous. No, that’s not really true. I feel a lot jealous. I’ve often thought Grandfather wanted me to be a boy. Now I’m sure of it.

Thursday, December 16

1943 (#ulink_fd8904b9-b12a-5a6e-b52b-b66e44eddb8a)

When school ends tomorrow it’ll be the end of term and that’s four days earlier than we thought. We’ve got four days’ extra holiday. Hooray! Yippee! That’s because they’ve got to move out all the desks, the blackboard, the bookshelves, everything, down to the last piece of chalk. Mrs Blumfeld told us the American soldiers will be coming tomorrow to help us move out. We’ll be going to school in Kingsbridge after Christmas. There’ll be a bus to take us in because it’s too far to walk. And Mrs Blumfeld said today that she’ll go on being our teacher there. We all cheered and we meant it too. She’s the best teacher I’ve ever had, only sometimes I still don’t exactly understand her because of how she speaks. Because she’s from Holland we’ve got lots of pictures of Amsterdam on the wall. They’ve got canals instead of roads there. She’s put up two big paintings, both by Dutchmen, one of an old lady in a hat by a painter called Rembrandt (that’s funny spelling, but it’s right), and one of colourful ships on a beach by someone else. I can’t remember his name, I think it’s Van something or other. I was looking at that one today while we were practising carols. We were singing I Saw Three Ships Come Sailing In, and there they were up on the wall, all these ships. Funny that. I don’t really understand that carol. What’s three ships sailing in got to do with the birth of Jesus? I like the tune though. I’m humming it now as I write.

We all think she’s very brave to go on teaching us like she has after her husband was drowned. Everyone else in the village likes her now. She’s always out cycling in her blue headscarf, ringing her bell and waving whenever she sees us. I hope she doesn’t remember how mean I was to her when she first came. I don’t think she can do because she chose me to sing a solo in the carol concert, the first verse of In the Bleak Midwinter. I practise all the time: on the way home, out in the fields, in the bath. Barry says it sounds really good, which is nice of him. And he doesn’t pick his nose at all any more, nor smile at me all the time. Maybe he knows he doesn’t need to smile at me – maybe he knows I like him. My singing sounds really good in the bath, I know it does. But I can’t take the bath into church, can I?

Saturday, December 18

1943 (#ulink_9f9a5a60-4da4-52b5-8a8a-d78947810c6f)

I love Christmas carols, especially In the Bleak Midwinter. I wish we didn’t only sing them at Christmas time. We had our carol concert this afternoon in the church and I had to sing my verse in front of everyone. I wobbled a bit on one or two notes, but that’s because I was trembling all over, like a leaf, just before I did it. Barry told me it sounded perfect, but I knew he said that just to make me happy. And it did, but then I thought about it. The thing is that Barry can sing only on one note, so he wouldn’t really know if it sounded good or bad, would he?

There’s only a fortnight to go now before we’re supposed to leave. Barry keeps asking me what will happen to Grandfather if he doesn’t move out. He’s frightened they’ll take him off to prison. That’s because we had a visit yesterday from the army and the police telling Grandfather he had to pack up and go, or he’d be in real trouble. Grandfather saw them off good and proper, but they said they’ll be back. I just wish Barry wouldn’t keep asking me about what’s going to happen, because I don’t know, do I? No one does. Maybe they will put him in prison. Maybe they’ll put us all in prison. It makes me very frightened every time I think about it. So I’ll try not to. If I do think about it, then I’ll just have to make myself worry about something else. This evening Barry and me were sitting at the top of the staircase in our dressing gowns listening to Mum and Grandfather arguing about it again down in the kitchen. Grandfather sounded more angry than I’ve ever heard him. He said he’d rather shoot himself than be moved off the farm. He kept on about how he doesn’t hold with this war anyhow, and never did, how he went through the last one in the trenches and that was horror enough for one lifetime. “If people only knew what it was really like,” he said, and he sounded as if he was almost crying he was so angry. “If they knew, if they’d seen what I’ve seen, they’d never send young men off to fight again. Never.” He just wanted to be left alone in peace to do his farming.

Again and again Mum tried to reason with him, tried to tell him that everyone in the village was leaving, not just us; that no one wanted to go but we had to, so that the Americans could practise their landings, go over to France, and finish the war quickly. Then we’d all be back home soon enough and Dad would be back with us and the war would be over and done with. It would only be for a short time, she said. They’d promised. But Grandfather wouldn’t believe her and he wouldn’t believe them. He said the Yanks were just saying that so they could get him out.

In the end he slammed out of the house and left her. We heard Mum crying, so we went downstairs. Barry made her a cup of tea, and I held her hands and told her it would be all right, that I was sure Grandfather would give in and go in the end. But I was just saying it. He won’t go, not of his own accord anyway, not in a million years. They’ll have to carry him out, and, like Mum said, when they do it will break his heart.

Thursday, December 23

1943 (#ulink_ecef4300-420b-5ce0-a5ba-705a5336799f)

Letter from Dad to all of us, wishing us a happy Christmas. He says he’s in Italy now, and it’s nothing but rain and mud and you go up one hill and there’s always another one ahead of you, but that at least each hill brings him nearer home. We’d just finished reading it at breakfast when there was a knock on the door. It was Mrs Blumfeld. She was bringing her Christmas card, she said. Mum asked her in. She was all red in the face and breathless from her cycling. It seemed so strange having her here in the house. She didn’t seem like our teacher at all, more like a visiting aunt. Tips was up on her lap as soon as she’d sat down. She sipped her tea and said how nice Tips was, even when she was sharpening her claws on her knees.

Then suddenly she looked across at Grandfather. I don’t remember everything she said, but it was something like this. “You and me, Mr Tregenza,” she said, “I think we have so much – how do you say it in English? – in common.” Grandfather looked a bit flummoxed (good word that). “They tell me you are the only one in the village who won’t leave. I would be just like you, I think. I loved our home in Holland, in Amsterdam. It is where I grew up. All I loved was in our home. But we had to leave; we could do nothing else. There was no choice for us because the Germans were coming. They were invading our country. We did what we could to stop them but it was no good. There were too many tanks and planes. They were too strong for us. My husband, Jacobus, was a Jew, Mr Tregenza. I am a Jew. We knew what they wanted to do with Jews. They wanted to kill us all, like rats, get rid of us. We knew this. So we had to leave our home. We came to England, Mr Tregenza, where we could be safe. Jacobus, he joined the merchant navy. He was a sea captain in Holland. We Dutch are good sailors, like you English. He was a good man and a very kind man, as you are – Barry has told me this and Lily too. They may have killed him, Mr Tregenza, but they have not killed me, not yet. They would if they could. If they come here they will.”

Grandfather’s eyes never left her face all the time she was talking. “That is why I ask you to leave your home, as I did, so that the American soldiers can come. They will borrow your house and your fields for a few months to do their practising. Then they can go across the sea and liberate my people and my country, and many other countries too. This way the Germans will never come here, never march in your streets. This way my people will not suffer any longer. I know it is hard, Mr Tregenza, but I ask you to do this for me, for my husband, for my country – for your country too. I think you will, because I know you have a good heart.”

I could see Grandfather’s eyes were full of tears. He got up, shrugged on his coat and pulled on his hat without ever saying a word. At the door he stopped and turned around. Then all he said was, “I’ll say one thing, missus. I wish I’d had a teacher like you when I was a little ‘un.” Then he went out and Barry ran out after him, and we were left there looking at one another in silence.

Mrs Blumfeld didn’t stay long after that, and we didn’t see Grandfather and Barry again until they came back for lunch. Grandfather was washing his hands in the sink when he suddenly said that he’d been thinking it over and that we could all start packing up after lunch, that he’d begin moving the sheep over to Uncle George’s right away, and he’d be needing both Barry and me to give him a hand. Then very quietly he said: “Just so long as we can come back afterwards.”

“We will, I promise,” Mum told him, and she went over to hug him. He cried then. That was the first time I’ve ever seen Grandfather cry.

Saturday, December 25

1943 (#ulink_33cbf3d7-8639-519f-9c75-42397e51634a)

Christmas Day. There’s no point in pretending this was a happy Christmas. We tried to make the best of it. We had decorations everywhere as usual and a nice Christmas tree. We had our stockings all together in Grandfather’s bed. But Dad wasn’t there. Mum missed him a lot and so did I. Barry was homesick too and Grandfather was really down in the dumps all day and grumpy about moving. We had roast chicken for lunch, which did make everyone feel a little happier. I found a silver threepenny bit in the Christmas pudding and Barry found one too, so that made him forget he was homesick, for a while anyway. We all gave Grandfather a hand with the evening milking to cheer him up, and it worked, but not for long. There’s only a week to go now before we have to have everything out of here. It’s all Grandfather can think about. The house is piled high with tea chests and boxes. The curtains and lamp shades are all down, most of the crockery is already packed. We may have the Christmas decorations up, but it doesn’t feel at all like Christmas.

For my present I got a pair of red woolly gloves that Mum had knitted specially and secretly, and Barry had a navy blue scarf which he wears all the time, even at meal times. Mum didn’t knit that, she didn’t have time. We all went off to church this evening. It’s the last time we’ll be doing that for a long while. They’re going to empty it of all its precious things – stained glass windows, candlesticks, benches – in case they get damaged. The American soldiers are coming to take it all away. They’ll be putting sandbags around everything that’s too heavy to move, so that everything will be protected as much as possible. That’s what the vicar told us – he also said they’ll be needing all the help they can get. They’re starting to empty the church tomorrow. Mum says we’ve all got to be there to lend a hand.

I gave Tips some cold chicken this evening for her Christmas supper. She licked the plate until it was shiny clean. She’s a bit upset, I think. She knows something’s up. She can see it for herself and she can feel it too. I think she’s unhappy because she knows we’re unhappy.

I’m getting a bit fed up with Uncle George already, and we haven’t even moved in with him yet. All he talks about is the war: the Germans this and the Russians that. He sits there with his ear practically glued to the radio, tutting and huffing at the news. Even today, on Christmas Day, he has to go on and on about how we should “bomb Germany to smithereens, because of all they’ve done to us”! Then once he got talking about it, everyone was talking about it, arguing about it. So I came up to bed and left them to it. It’s supposed to be a day of peace and goodwill towards all men. And all they can talk about is the war. It makes me so sad, and I shouldn’t be sad on Christmas Day. But now I am. Happy Christmas, Dad.

PS Just after I finished my diary I heard Barry crying in his room, so I went to see him. He didn’t want to tell me at first. Then he said he was just a bit homesick, missing his mum, he said. And his dad – mostly his dad. What could I say? My dad is alive and I’m living in my own home, going to my own school. Then I had an idea. “Shall we say Happy Christmas to the cows?” I said. He cheered up at once. So we crept downstairs in our dressing gowns and slippers, and ran out to the barn. They were all lying down in the straw grunting and chewing the cud, their calves curled up asleep beside them. Barry crouched down and stroked one of them, who sucked his finger until he giggled and pulled it out. We were walking back across the yard when he told me. “I hate the radio,” he said suddenly. “It’s always about the war, and the bombing raids, and that’s when I think of Mum most and miss her most. I don’t want her to die. I don’t want to be an orphan.”

I held his hand and squeezed it. I was too upset to say anything.

Sunday, December 26

1943 (#ulink_0c5c7cc3-cb4f-5c39-8c73-e967b42e6af2)

I’ve had the strangest day and the happiest day for a long time. I met someone who’s the most different person I’ve ever met. He’s different in every way. He looks different, he sounds different, he is different. And, best of all, he’s my friend.

We were supposed to be helping to move things out of the church, but mostly we were just watching, because the Yanks were doing it all for us. Grandfather’s right: they do chew gum a lot. But they’re very happy-looking, always laughing and joking around. Some of them were carrying sandbags into the church, whilst others were carrying out the pews and chairs, hymn books and kneelers.

Suddenly I recognised one of them. He was the same black soldier I had seen in the jeep a while ago. And he recognised me too. “Hi there! How you doing?” he said. I never saw anyone smile like he did. His whole face lit up with it. He looked too young to be a soldier. He seemed so pleased to see me there, someone he recognised. He bent down so that his face was very close to mine. “I got three little sisters back home in Atlanta – that’s in Georgia and that’s in the United States of America, way across the sea,” he said. “And they’s all pretty, just like you.”

Then another soldier came along – I think he was a sergeant or something because he had lots of stripes on his arm, upside-down ones, not like our soldiers’ stripes at all. The sergeant told him he should be carrying sandbags, not chatting to kids. So he said, “Yessir.” Then he went off, smiling back at me over his shoulder. The next time I saw him he was coming past me with a sandbag under each arm. He stopped right by me and looked down at me from very high up. “What do you call yourself, girl?” he asked me. So I told him. Then he said, “I’m Adolphus T. Madison. (That’s T for Thomas.) Private First Class, US Army. My friends call me Adie. I’m mighty pleased to make your acquaintance, Lily. A ray of Atlanta sunshine, that’s what you are, a ray of Atlanta sunshine.”

No one has ever talked to me like that before. He looked me full in the eye as he spoke, so I knew he meant every word he said. But the sergeant shouted at him again and he had to go.

Then Barry came along, and for the rest of the morning we stood at the back of the church watching the soldiers coming and going, all of them fetching and carrying sandbags now, and Adie would give me a great big grin every time he went by. The vicar was fussing about them like an old hen, telling the Yank soldiers they had to be more careful, particularly when they were sandbagging the font. “That font’s very precious, you know,” said the vicar. I could see they didn’t like being pestered, but they were all too polite and respectful to say anything. The vicar kept on and on nagging at them. “It’s the most precious thing in the church. It’s Norman, you know, very old.” A couple of Yanks were just coming past us with more sandbags a few moments later when one of them said, “Who is this old Norman guy, anyway?”

After that Barry and me couldn’t stop ourselves giggling. The vicar told us we shouldn’t be giggling in church, so we went outside and giggled in the graveyard instead.

We told Grandfather and Mum about that when we got back this evening and they laughed so much they nearly cried. It’s been a happy, happy day. I hope Adie doesn’t get killed in the war. He’s so nice. I’m going to pray for him tonight, and for Dad too.

Tips has just brought in a dead mouse and dropped it at my feet. She knows how much I hate mice, dead or alive. I really wish she wouldn’t do it. She’s sitting there, licking her lips and looking so pleased with herself. Sometimes I think I understand why Barry doesn’t like cats.

Monday, December 27

1943 (#ulink_66d242a6-9a33-54fb-a8f6-605ad904c712)

It’s my very last night in my own bedroom. Until now I don’t think I thought it would ever really happen, not to us, not to me. It was happening to everyone else. Everyone else was moving out, but somehow I just didn’t imagine that the day would ever come when we’d have to do the same. But tomorrow is the final day and tomorrow will come. This time tomorrow my room will bè empty – the whole house will be empty. I’ve never slept anywhere else in my whole life except in this room. For the first time I think I understand why Grandfather refused to leave for so long. It wasn’t just because he was being stubborn and difficult and grumpy. He loves this place, and so do I. I look around this room and it’s a part of me. I belong here. I’ll start to cry if I write any more, so I’ll stop.

Tuesday, December 28

1943 (#ulink_78845493-813e-510b-813a-e096b207375d)

Our first night at Uncle George’s and it’s cold. But there’s something worse than that, much worse. Tips has gone missing. We haven’t got her with us.

We moved up here today. We were the last ones in the whole village to move out. Grandfather is very proud of that. We had lots of help. Mrs Blumfeld came and so did Adie, along with half a dozen other Yanks. We couldn’t have managed without them. Everything is here, all the tea chests, all the furniture. Most of it is stored in Uncle George’s granary under an old tarpaulin. But the cows are still back home on the farm. We’ll go back for them tomorrow, Grandfather said, and drive them up the lane.

Uncle George has made room here for all of us. He’s very kind, I suppose, but he talks to himself too much and he grunts and wheezes a lot, and when he blows his nose it sounds like a foghorn. He’s very dirty and scruffy and untidy, which Mum doesn’t like, and I think he’s a bit proud too. I was only trying to be polite, because Mum said I should be, when I asked him which chair was his before I sat down. Uncle George said: “They’m all my chairs Lil.” (I wish he wouldn’t call me Lil, only Mum and Dad call me that.) He was laughing as he said it, but he meant it, I know he did. I think it’s because he’s Mum’s eldest brother that he’s a bit bossy with us. He keeps saying Dad shouldn’t have gone off to the war and left her on her own. That’s what I think too, but I don’t like it when Uncle George says it. Anyway, she’s not on her own. She’s got Grandfather and she’s got me.

.Mum says I have to be very patient with him because he’s a bachelor, which means that he’s lived on his own all his life which is why he’s untidy and doesn’t know how to get on with people very well. I’ll try, but it’s not going to be easy. And what’s more, he looks like a scarecrow, except when he’s in his Home Guard uniform. When he’s in his uniform he looks very pleased with himself. Grandfather says he doesn’t do much in the Home Guard, that he just sits up in the lookout post on top of the hill. They’re supposed to be looking for enemy ships and planes, but Grandfather says they just have a good natter and a smoke.

I miss my room at home already. My bedroom here is not just cold, it’s very small, a bit like a cupboard – a cupboard I have to share with Mum. Barry’s in with Grandfather. It was the only way to fit us all in. Mum and me have to share a bed too, but I don’t mind that. We’ll cuddle up. She’ll keep me warm! I haven’t got a table, so I’m writing this sitting up in bed with my diary on my knees.

I wish Tips was here. I miss her and I’m really worried about her. She ran off when everyone came to the house to carry the furniture out. I called and called, but she didn’t come. I’m trying my best not to be worried. Mum says she’s just gone off on her wanders somewhere, that she’ll come back when the house is quiet again. She’s sure she’ll be there when we go to fetch the animals tomorrow. She keeps saying there are still three days to go before they close the farm off, but I can’t stop thinking that after that we won’t be allowed back for six months or even more. What if Tips isn’t there tomorrow? What if we can’t find her?

Barry’s happier than ever, because he’s got two farmers to work with now, and two tractors. But what’s more surprising is that Grandfather is happy too. I thought he was going to be very sad when we left home. I was there when he locked the door and slipped the key into his waistcoat pocket. He stood looking up at the house for some moments. He even tried to smile. But he never said anything. He just took my hand and Barry’s, and we all walked off without looking back. He made himself at home in Uncle George’s kitchen right away. He’s got his feet in the oven already, which you can see Uncle George doesn’t like. But Grandfather’s much older than he is, so Uncle George will just have to put up with it, won’t he?

Oh yes, I forgot. This afternoon Adie introduced me to his friend Harry, while they were carrying out our kitchen table. He’s from Atlanta too, and he’s black like Adie is. They’re both quite difficult to understand sometimes because they speak English differently from us. Adie does most of the talking. “Harry’s like my brother, Lily, not my brother brother, if you get my meaning, just my friend. Like twins, ain’t we, Harry? Always on the lookout for one another. Harry and me, we growed up together, same street, same town. We was born on the same day too – 25