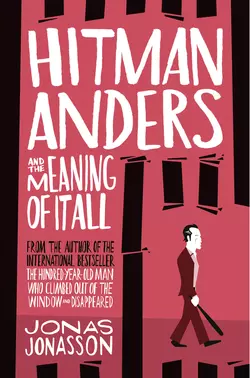

Hitman Anders and the Meaning of It All

Jonas Jonasson

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 659.93 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A madcap new novel from the one-of-a-kind author of The Hundred-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out of the Window and The Girl Who Saved the King of SwedenIT’S NEVER TOO LATE TO START AGAIN. AND AGAIN.It’s always awkward when five thousand kronor goes missing. When it happens at a certain grotty hotel in south Stockholm, it’s particularly awkward because the money belongs to the hitman currently staying in room seven. Per Persson, the hotel receptionist, just wants to mind his own business, and preferably not get murdered. Johanna Kjellander, temporarily resident in room eight, is a priest without a vocation, and, as of last week, without a parish. But right now she has two things at her disposal: an envelope containing five thousand kronor, and an excellent idea . . .Featuring one violent killer, two shrewd business brains and many crates of Moldovan red wine, Hitman Anders and the Meaning of It All is an outrageously zany story with as many laughs as Jonasson’s multimillion-copy bestseller The Hundred-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out of the Window and Disappeared.