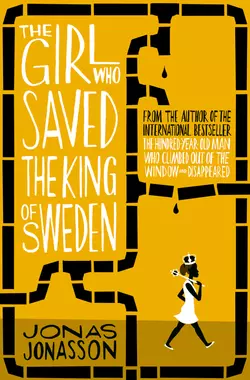

The Girl Who Saved the King of Sweden

The Girl Who Saved the King of Sweden

Jonas Jonasson

Nombeko Mayeki was never meant to be a hero. Born in a Soweto shack, she seemed destined for a short, hard life. But now she is on the run from the world ‘s most ruthless secret service, with three Chinese sisters, twins who are officially one person and an elderly potato farmer. Oh, and the fate of the King of Sweden – and the world – rests on her shoulders.As uproariously funny as Jonas Jonasson’s bestselling debut, this is an entrancing tale of luck, love and international relations.

Jonas Jonasson

The Girls Who Saved the King of Sweden

COPYRIGHT

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thestate.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2014

First published in the United States by Ecco in 2014

Originally published in Sweden as Analfabeten som kunde räkna by Piratforlaget in 2013

Copyright © Jonas Jonasson 2014

Jonas Jonasson asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work

‘Tonight I Can Write’, from Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair by Pablo Neruda, translated by W. S. Merwin, translation copyright © 1969 by W. S. Merwin; used by permission of Jonathan Cape, an imprint of Random House. Pooh’s Little Instruction Book inspired by A. A. Milne © 1995 the Trustees of the Pooh Properties, original text and compilation of illustrations; used by permission of Egmont UK Ltd, and by permission of Curtis Brown Ltd. How to Cure a Fanatic by Amos Oz; used by permission of Vintage, a division of Random House.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Cover by Jonathan Pelham

Source ISBN: 9780007557905

Ebook Edition © April 2014 ISBN: 9780007557882

Version: 2018-06-18

EPIGRAPH

The statistical probability that an illiterate in 1970s Soweto will grow up and one day find herself confined in a potato truck with the Swedish king and prime minister is 1 in 45,766,212,810.

According to the calculations of the aforementioned illiterate herself.

PART ONE

The difference between stupidity and genius is that genius has its limits.

Unknown

CHAPTER 1

On a girl in a shack and the man who posthumously helped her escape it

In some ways they were lucky, the latrine emptiers in South Africa’s largest shantytown. After all, they had both a job and a roof over their heads.

On the other hand, from a statistical perspective they had no future. Most of them would die young of tuberculosis, pneumonia, diarrhoea, pills, alcohol or a combination of these. One or two of them might get to experience his fiftieth birthday. The manager of one of the latrine offices in Soweto was one example. But he was both sickly and worn-out. He’d started washing down far too many painkillers with far too many beers, far too early in the day. As a result, he happened to lash out at a representative of the City of Johannesburg Sanitation Department who had been dispatched to the office. A Kaffir who didn’t know his place. The incident was reported all the way up to the unit director in Johannesburg, who announced the next day, during the morning coffee break with his colleagues, that it was time to replace the illiterate in Sector B.

Incidentally it was an unusually pleasant morning coffee break. Cake was served to welcome a new sanitation assistant. His name was Piet du Toit, he was twenty-three years old, and this was his first job out of college.

The new employee would be the one to take on the Soweto problem, because this was how things were in the City of Johannesburg. He was given the illiterates, as if to be toughened up for the job.

No one knew whether all of the latrine emptiers in Soweto really were illiterate, but that’s what they were called anyway. In any case, none of them had gone to school. And they all lived in shacks. And had a terribly difficult time understanding what one told them.

* * *

Piet du Toit felt ill at ease. This was his first visit to the savages. His father, the art dealer, had sent a bodyguard along to be on the safe side.

The twenty-three-year-old stepped into the latrine office and couldn’t help immediately complaining about the smell. There, on the other side of the desk, sat the latrine manager, the one who was about to be dismissed. And next to him was a little girl who, to the assistant’s surprise, opened her mouth and replied that this was indeed an unfortunate quality of shit – it smelled.

Piet du Toit wondered for a moment if the girl was making fun of him, but that couldn’t be the case.

He let it go. Instead he told the latrine manager that he could no longer keep his job because of a decision higher up, but that he could expect three months of pay if, in return, he picked out the same number of candidates for the position that had just become vacant.

‘Can I go back to my job as a permanent latrine emptier and earn a little money that way?’ the just-dismissed manager wondered.

‘No,’ said Piet du Toit. ‘You can’t.’

One week later, Assistant du Toit and his bodyguard were back. The dismissed manager was sitting behind his desk, for what one might presume was the last time. Next to him stood the same girl as before.

‘Where are your three candidates?’ said the assistant.

The dismissed apologized: two of them could not be present. One had had his throat slit in a knife fight the previous evening. Where number two was, he couldn’t say. It was possible he’d had a relapse.

Piet du Toit didn’t want to know what kind of relapse it might be. But he did want to leave.

‘So who is your third candidate, then?’ he said angrily.

‘Why, it’s the girl here beside me, of course. She’s been helping me with all kinds of things for a few years now. I must say, she’s a clever one.’

‘For God’s sake, I can’t very well have a twelve-year-old latrine manager, can I?’ said Piet du Toit.

‘Fourteen,’ said the girl. ‘And I have nine years’ experience.’

The stench was oppressive. Piet du Toit was afraid it would cling to his suit.

‘Have you started using drugs yet?’ he said.

‘No,’ said the girl.

‘Are you pregnant?’

‘No,’ said the girl.

The assistant didn’t say anything for a few seconds. He really didn’t want to come back here more often than was necessary.

‘What is your name?’ he said.

‘Nombeko,’ said the girl.

‘Nombeko what?’

‘Mayeki, I think.’

Good Lord, they didn’t even know their own names.

‘Then I suppose you’ve got the job, if you can stay sober,’ said the assistant.

‘I can,’ said the girl.

‘Good.’

Then the assistant turned to the dismissed manager.

‘We said three months’ pay for three candidates. So, one month for one candidate. Minus one month because you couldn’t manage to find anything other than a twelve-year-old.’

‘Fourteen,’ said the girl.

Piet du Toit didn’t say goodbye when he left. With his bodyguard two steps behind him.

The girl who had just become her own boss’s boss thanked him for his help and said that he was immediately reinstated as her right-hand man.

‘But what about Piet du Toit?’ said her former boss.

‘We’ll just change your name – I’m sure the assistant can’t tell one black from the next.’

Said the fourteen-year-old who looked twelve.

* * *

The newly appointed manager of latrine emptying in Soweto’s Sector B had never had the chance to go to school. This was because her mother had had other priorities, but also because the girl had been born in South Africa, of all countries; furthermore, she was born in the early 1960s, when the political leaders were of the opinion that children like Nombeko didn’t count. The prime minister at the time made a name for himself by asking rhetorically why the blacks should go to school when they weren’t good for anything but carrying wood and water.

In principle he was wrong, because Nombeko carried shit, not wood or water. Yet there was no reason to believe that the tiny girl would grow up to socialize with kings and presidents. Or to strike fear into nations. Or to influence the development of the world in general.

If, that is, she hadn’t been the person she was.

But, of course, she was.

Among many other things, she was a hardworking child. Even as a five-year-old she carried latrine barrels as big as she was. By emptying the latrine barrels, she earned exactly the amount of money her mother needed in order to ask her daughter to buy a bottle of thinner each day. Her mother took the bottle with a ‘Thank you, dear girl,’ unscrewed the lid, and began to dull the never-ending pain that came with the inability to give oneself or one’s child a future. Nombeko’s dad hadn’t been in the vicinity of his daughter since twenty minutes after the fertilization.

As Nombeko got older, she was able to empty more latrine barrels each day, and the money was enough to buy more than just thinner. Thus her mum could supplement the solvent with pills and booze. But the girl, who realized that things couldn’t go on like this, told her mother that she had to choose between giving up or dying.

Her mum nodded in understanding.

The funeral was well attended. At the time, there were plenty of people in Soweto who devoted themselves primarily to two things: slowly killing themselves and saying a final farewell to those who had just succeeded in that endeavour. Nombeko’s mum died when the girl was ten years old, and, as mentioned earlier, there was no dad available. The girl considered taking over where her mum had left off: chemically building herself a permanent shield against reality. But when she received her first pay cheque after her mother’s death, she decided to buy something to eat instead. And when her hunger was alleviated, she looked around and said, ‘What am I doing here?’

At the same time, she realized that she didn’t have any immediate alternatives. Ten-year-old illiterates were not the prime candidates on the South African job market. Or the secondary ones, either. And in this part of Soweto there was no job market at all, or all that many employable people, for that matter.

But defecation generally happens even for the most wretched people on our Earth, so Nombeko had one way to earn a little money. And once her mother was dead and buried, she could keep her salary for her own use.

To kill time while she was lugging barrels, she had started counting them when she was five: ‘One, two, three, four, five…’

As she grew older, she made these exercises harder so they would continue to be challenging: ‘Fifteen barrels times three trips times seven people carrying, with another one who sits there doing nothing because he’s too drunk… is… three hundred and fifteen.’

Nombeko’s mother hadn’t noticed much around her besides her bottle of thinner, but she did discover that her daughter could add and subtract. So during her last year of life she had started calling upon her each time a delivery of tablets of various colours and strengths was to be divided among the shacks. A bottle of thinner is just a bottle of thinner. But when pills of 50, 100, 250 and 500 milligrams must be distributed according to desire and financial ability, it’s important to be able to tell the difference between the four kinds of arithmetic. And the ten-year-old could. Very much so.

She might happen, for example, to be in the vicinity of her immediate boss while he was struggling to compile the monthly weight and amount report.

‘So, ninety-five times ninety-two,’ her boss mumbled. ‘Where’s the calculator?’

‘Eight thousand seven hundred and forty,’ Nombeko said.

‘Help me look for it instead, little girl.’

‘Eight thousand seven hundred and forty,’ Nombeko said again.

‘What’s that you’re saying?’

‘Ninety-five times ninety-two is eight thousand seven hund—’

‘And how do you know that?’

‘Well, I think about how ninety-five is one hundred minus five, ninety-two is one hundred minus eight. If you turn it round and subtract, it’s eighty-seven together. And five times eight is forty. Eighty-seven forty. Eight thousand seven hundred and forty.’

‘Why do you think like that?’ said the astonished manager.

‘I don’t know,’ said Nombeko. ‘Can we get back to work now?’

From that day on, she was promoted to manager’s assistant.

But in time, the illiterate who could count felt more and more frustrated because she couldn’t understand what the supreme powers in Johannesburg wrote in all the decrees that landed on the manager’s desk. The manager himself had a hard time with the words. He stumbled his way through every Afrikaans text, simultaneously flipping through an English dictionary so that the unintelligible letters were at least presented to him in a language he could understand.

‘What do they want this time?’ Nombeko might ask.

‘For us to fill the sacks better,’ said the manager. ‘I think. Or that they’re planning to shut down one of the sanitation stations. It’s a bit unclear.’

The manager sighed. His assistant couldn’t help him. So she sighed, too.

But then a lucky thing happened: thirteen-year-old Nombeko was accosted by a smarmy man in the showers of the latrine emptiers’ changing room. The smarmy man hadn’t got very far before the girl got him to change his mind by planting a pair of scissors in his thigh.

The next day she tracked down the man on the other side of the row of latrines in Sector B. He was sitting in a camping chair with a bandage round his thigh, outside his green-painted shack. In his lap he had… books?

‘What do you want?’ he said.

‘I believe I left my scissors in your thigh yesterday, Uncle, and now I’d like them back.’

‘I threw them away,’ the man said.

‘Then you owe me some scissors,’ said the girl. ‘How come you can read?’

The smarmy man’s name was Thabo, and he was half toothless. His thigh hurt an awful lot, and he didn’t feel like having a conversation with the ill-tempered girl. On the other hand, this was the first time since he’d come to Soweto that someone seemed interested in his books. His shack was full of them, and for this reason his neighbours called him Crazy Thabo. But the girl in front of him sounded more jealous than scornful. Maybe he could use this to his advantage.

‘If you were a bit more cooperative instead of violent beyond all measure, perhaps Uncle Thabo might consider telling you. Maybe he would even teach you how to interpret letters and words. If you were a bit more cooperative, that is.’

Nombeko had no intention of being more cooperative towards the smarmy man than she had been in the shower the day before. So she replied that, as luck would have it, she had another pair of scissors in her possession, and that she would very much like to keep them rather than use them on Uncle Thabo’s other thigh. But as long as Uncle kept himself under control – and taught her to read – thigh number two would remain in good health.

Thabo didn’t quite understand. Had the girl just threatened him?

* * *

One couldn’t tell by looking at him, but Thabo was rich. He had been born under a tarpaulin in the harbour of Port Elizabeth in Eastern Cape Province. When he was six years old, the police had taken his mother and never given her back. The boy’s father thought the boy was old enough to take care of himself, even though the father had problems doing that very thing.

‘Take care of yourself’ was the sum of his father’s advice for life before he clapped his son on the shoulder and went to Durban to be shot to death in a poorly planned bank robbery.

The six-year-old lived on what he could steal in the harbour, and in the best case one could expect that he would grow up, be arrested and eventually either be locked up or shot to death like his parents.

But another long-term resident of the slums was a Spanish sailor, cook and poet who had once been thrown overboard by twelve hungry seamen who were of the opinion that they needed food, not sonnets, for lunch.

The Spaniard swam to shore and found a shack to crawl into, and since that day he had lived for poetry, his own and others’. As time went by and his eyesight grew worse and worse, he hurried to snare young Thabo, then forced him to learn the art of reading in exchange for bread. Subsequently, and for a little more bread, the boy devoted himself to reading to the old man, who had not only gone completely blind but also half senile and fed on nothing more than Pablo Neruda for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

The seamen had been right that it is not possible to live on poetry alone. For the old man starved to death and Thabo decided to inherit all his books. No one else cared, anyway.

The fact that he was literate meant that the boy could get by in the harbour with various odd jobs. At night he would read poetry or fiction – and, above all, travelogues. At the age of sixteen, he discovered the opposite sex, which discovered him in return two years later. So it wasn’t until he was eighteen that Thabo found a formula that worked. It consisted of one-third irresistible smile; one-third made-up stories about all the things he had done on his journeys across the continent, which he had thus far not undertaken other than in his imagination; and one-third flat-out lies about how eternal their love would be.

He did not achieve true success, however, until he added literature to the smiling, storytelling and lying. Among the things he inherited, he found a translation the sailor had done of Pablo Neruda’s Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair. Thabo tore out the song of despair, but he practised the twenty love poems on twenty different women in the harbour district and was able to experience temporary love nineteen times over. There would probably have been a twentieth time, too, if only that idiot Neruda hadn’t stuck in a line about ‘I no longer love her, that’s certain’ towards the end of a poem; Thabo didn’t discover this until it was too late.

A few years later, most of the neighbourhood knew what sort of person Thabo was; the possibilities for further literary experiences were slim. It didn’t help that he started telling lies about everything he had done in life that were worse than those King Leopold II had told in his day, when he had said that the natives of the Belgian Congo were doing fine even as he had the hands and feet chopped off anyone who refused to work for free.

Oh well, Thabo would get what was coming to him (as did the Belgian king, incidentally – first he lost his colony, then he wasted all his money on his favourite French-Romanian prostitute, and then he died). But first Thabo made his way out of Port Elizabeth: he went directly north and ended up in Basutoland where the women with the roundest figures were said to be.

There he found reason to stay for several years; he switched villages when the circumstances called for it, always found a job thanks to his ability to read and write, and eventually went so far as to become the chief negotiator for all the European missionaries who wanted access to the country and its uninformed citizens.

The chief of the Basotho people, His Excellence Seeiso, didn’t see the value in letting his people be Christianized, but he realized that the country needed to free itself from all the Boers in the area. When the missionaries – on Thabo’s urging – offered weapons in exchange for the right to hand out Bibles, the chief jumped at the opportunity.

And so pastors and lay missionaries streamed in to save the Basotho people from evil. They brought with them Bibles, automatic weapons and the occasional land mine.

The weapons kept the enemy at bay while the Bibles were burned by frozen mountain-dwellers. After all, they couldn’t read. When the missionaries realized this, they changed tactics and built a great number of Christian temples in a short amount of time.

Thabo took odd jobs as a pastor’s assistant and developed his own form of the laying on of hands, which he practised selectively and in secret.

Things on the romance front only went badly once. This occurred when a mountain village discovered that the only male member of the church choir had promised everlasting fidelity to at least five of the nine young girls in the choir. The English pastor there had always suspected what Thabo was up to. Because he certainly couldn’t sing.

The pastor contacted the five girls’ fathers, who decided that the suspect should be interrogated in the traditional manner. This is what would happen: Thabo would be stuck with spears from five different directions during a full moon, while sitting with his bare bottom in an anthill. While waiting for the moon to reach the correct phase, Thabo was locked in a hut over which the pastor kept constant watch, until he got sunstroke and instead went down to the river to save a hippopotamus. The pastor cautiously laid a hand on the animal’s nose and said that Jesus was prepared to—

This was as far as he got before the hippopotamus opened its mouth and bit him in half.

With the pastor-cum-jailer gone, and with the help of Pablo Neruda, Thabo managed to get the female guard to unlock the door so he could escape.

‘What about you and me?’ the prison guard called after him as he ran as fast as he could out onto the savannah.

‘I no longer love you, that’s certain,’ Thabo called back.

If one didn’t know better, one might think that Thabo was protected by God, because he encountered no lions, leopards, rhinoceroses or anything else during his twelve-mile night-time walk to the capital city, Maseru. Once there, he applied for a job as adviser to Chief Seeiso, who remembered him from before and welcomed him back. The chief was negotiating with the high-and-mighty Brits for independence, but he didn’t make any headway until Thabo joined in and said that if the gentlemen intended to keep being this stubborn, Basutoland would have to think about asking for help from Joseph Mobutu in Congo.

The Brits went stiff. Joseph Mobutu? The man who had just informed the world that he was thinking about changing his name to the All-Powerful Warrior Who, Thanks to His Endurance and Inflexible Will to Win, Goes from Victory to Victory, Leaving Fire in His Wake?

‘That’s him,’ said Thabo. ‘One of my closest friends, in fact. To save time, I call him Joe.’

The British delegation requested deliberation in camera, during which it was agreed that what the region needed was peace and quiet, not some almighty warrior who wanted to be called what he had decided he was. The Brits returned to the negotiating table and said:

‘Take the country, then.’

Basutoland became Lesotho; Chief Seeiso became King Moshoeshoe II, and Thabo became the new king’s absolute favourite person. He was treated like a member of the family and was given a bag of rough diamonds from the most important mine in the country; they were worth a fortune.

But one day he was gone. And he had an unbeatable twenty-four-hour head start before it dawned on the king that his little sister and the apple of his eye, the delicate princess Maseeiso, was pregnant.

A person who was black, filthy and by that point half toothless in 1960s South Africa could not blend into the white world by any stretch of the imagination. Therefore, after the unfortunate incident in the former Basutoland, Thabo hurried on to Soweto as soon as he had exchanged the most trifling of his diamonds at the closest jeweller’s.

There he found an unoccupied shack in Sector B. He moved in, stuffed his shoes full of money, and buried about half the diamonds in the trampled dirt floor. The other half he put in the various cavities in his mouth.

Before he began to make too many promises to as many women as possible, he painted his shack a lovely green; ladies were impressed by such things. And he bought linoleum with which to cover the floor.

The seductions were carried out in every one of Soweto’s sectors, but after a while Thabo eliminated his own sector so that between times he could sit and read outside his shack without being bothered more than was necessary.

Besides reading and seduction, he devoted himself to travelling. Here and there, all over Africa, twice a year. This brought him both life experience and new books.

But he always came back to his shack, no matter how financially independent he was. Not least because half of his fortune was one foot below the linoleum; Thabo’s lower row of teeth was still in far too good condition for all of it to fit in his mouth.

It took a few years before mutterings were heard among the shacks in Soweto. Where did that crazy man with the books get all his money from?

In order to keep the gossip from taking too firm a hold, Thabo decided to get a job. The easiest thing to do was become a latrine emptier for a few hours a week.

Almost all of his colleagues were young, alcoholic men with no futures. But there was also the occasional child. Among them was a thirteen-year-old girl who had planted scissors in Thabo’s thigh just because he had happened to choose the wrong door into the showers. Or the right door, really. The girl was what was wrong. Far too young. No curves. Nothing for Thabo, except in a pinch.

The scissors had hurt. And now she was standing there outside his shack, and she wanted him to teach her to read.

‘I would be more than happy to help you, if only I weren’t leaving on a journey tomorrow,’ said Thabo, thinking that perhaps things would go most smoothly for him if he did what he’d just claimed he was going to do.

‘Journey?’ said Nombeko, who had never been outside Soweto in all her thirteen years. ‘Where are you going?’

‘North,’ said Thabo. ‘Then we’ll see.’

* * *

While Thabo was gone, Nombeko got one year older and promoted. And she quickly made the best of her managerial position. By way of an ingenious system in which she divided her sector into zones based on demography rather than geographical size or reputation, making the deployment of outhouses more effective.

‘An improvement of thirty per cent,’ her predecessor said in praise.

‘Thirty point two,’ said Nombeko.

Supply matched demand and vice versa, and there was enough money left over in the budget for four new washing and sanitation stations.

The fourteen-year-old was fantastically verbal, considering the language used by the men in her daily life (anyone who has ever had a conversation with a latrine emptier in Soweto knows that half the words aren’t fit to print and the other half aren’t even fit to think). Her ability to formulate words and sentences was partially innate. But there was also a radio in one corner of the latrine office, and ever since she was little, Nombeko had made sure to turn it on as soon as she was in the vicinity. She always tuned in to the talk station and listened with interest, not only to what was said but also to how it was said.

The weekly show View on Africa was what first gave her the insight that there was a world outside Soweto. It wasn’t necessarily more beautiful or more promising. But it was outside Soweto.

Such as when Angola had recently received independence. The independence party PLUA had joined forces with the independence party PCA to form the independence party MPLA, which, along with the independence parties FNLA and UNITA, caused the Portuguese government to regret ever having discovered that part of the continent. A government that, incidentally, had not managed to build a single university during its four hundred years of rule.

The illiterate Nombeko couldn’t quite follow which combination of letters had done what, but in any case the result seemed to have been change, which, along with food, was Nombeko’s favourite word.

Once she happened to opine, in the presence of her colleagues, that this change thing might be something for all of them. But then they complained that their manager was talking politics. Wasn’t it enough that they had to carry shit all day? Did they have to listen to it, too?

As the manager of latrine emptying, Nombeko was forced to handle not only all of her hopeless latrine colleagues, but also Assistant Piet du Toit from the sanitation department of the City of Johannesburg. During his first visit after having appointed her, he informed her that there would under no circumstances be four new sanitation stations – there would be only one, because of serious budgetary problems. Nombeko took revenge in her own little way:

‘From one thing to the next: what do you think of the developments in Tanzania, Mr Assistant? Julius Nyerere’s socialist experiment is about to collapse, don’t you think?’

‘Tanzania?’

‘Yes, the grain shortage is probably close to a million tons by now. The question is, what would Nyerere have done if it weren’t for the International Monetary Fund? Or perhaps you consider the IMF to be a problem in and of itself, Mr Assistant?’

Said the girl who had never gone to school or been outside Soweto. To the assistant who was one of the authorities. Who had gone to a university. And who had no knowledge of the political situation in Tanzania. The assistant had been white to start with. The girl’s argument turned him as white as a ghost.

Piet du Toit felt demeaned by a fourteen-year-old illiterate. Who was now rejecting his document on the sanitation funds.

‘By the way, how did you calculate this, Mr Assistant?’ said Nombeko, who had taught herself how to read numbers. ‘Why have you multiplied the target values together?’

An illiterate who could count.

He hated her.

He hated them all.

* * *

A few months later, Thabo was back. The first thing he discovered was that the girl with the scissors had become his boss. And that she wasn’t much of a girl any more. She had started to develop curves.

This sparked an internal struggle in the half-toothless man. On the one hand, his instinct told him to trust his by now gap-ridden smile, his storytelling techniques and Pablo Neruda. On the other hand, there was the part where she was his boss. Plus his memory of the scissors.

Thabo decided to act with caution, but to get himself into position.

‘I suppose by now it’s high time I teach you to read,’ he said.

‘Great!’ said Nombeko. ‘Let’s start right after work today. We’ll come to your shack, me and the scissors.’

Thabo was quite a capable teacher. And Nombeko was a quick learner. By day three she could write the alphabet using a stick in the mud outside Thabo’s shack. From day five on she spelled her way to whole words and sentences. At first she was wrong more often than right. After two months, she was more right than wrong.

In their breaks from studying, Thabo told her about the things he had experienced on his journeys. Nombeko soon realized that in doing so he was mixing two parts fiction with at the most one part reality, but she thought that was just as well. Her own reality was miserable enough as it was. She could do without much more of the same.

Most recently he had been in Ethiopia to depose His Imperial Majesty, the Lion of Judah, Elect of God, the King of Kings.

‘Haile Selassie,’ said Nombeko.

Thabo didn’t answer; he preferred speaking to listening.

The story of the emperor who had started out as Ras Tafari, which became rastafari, which became a whole religion, not least in the West Indies, was so juicy that Thabo had saved it for the day it was time to make a move.

Anyway, by now the founder had been chased off his imperial throne, and all over the world confused disciples were sitting around smoking while they wondered how it could be possible that the promised Messiah, God incarnate, had suddenly been deposed. Depose God?

Nombeko was careful not to ask about the political background of this drama. Because she was pretty sure that Thabo had no idea, and too many questions might disrupt the entertainment.

‘Tell me more!’ she encouraged him instead.

Thabo thought that things were shaping up very nicely (it’s amazing how wrong a person can be). He moved a step closer to the girl and continued his story by saying that on his way home he had swung by Kinshasa to help Muhammad Ali before the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ – the heavyweight match with the invincible George Foreman.

‘Oh wow, that’s so exciting,’ said Nombeko, thinking that, as a story, it actually was.

Thabo gave such a broad smile that she could see things glittering among the teeth he still had left. ‘Well, it was really the invincible Foreman who wanted my help, but I felt that…’ Thabo began, and he didn’t stop until Foreman was knocked out in the eighth round and Ali thanked his dear friend Thabo for his invaluable support.

And Ali’s wife had been delightful, by the way.

‘Ali’s wife?’ said Nombeko. ‘Surely you don’t mean that…’

Thabo laughed until his jaws jingled; then he grew serious again and moved even closer.

‘You are very beautiful, Nombeko,’ he said. ‘Much more beautiful than Ali’s wife. What if you and I were to get together? Move somewhere together.’

And then he put his arm round her shoulders.

Nombeko thought that ‘moving somewhere’ sounded lovely. Anywhere, actually. But not with this smarmy man. The day’s lesson seemed to be over. Nombeko planted a pair of scissors in Thabo’s other thigh and left.

The next day, she returned to Thabo’s shack and said that he had failed to come to work and hadn’t sent word, either.

Thabo replied that both of his thighs hurt too much, one in particular, and that Miss Nombeko probably knew why this was.

Yes, and it could be even worse, because next time she was planning to plant her scissors not in one thigh or the other, but somewhere in between, if Uncle Thabo didn’t start to behave himself.

‘What’s more, I saw and heard what you have in your ugly mouth yesterday. If you don’t shape up, starting now, I promise to tell as many people as possible.’

Thabo became quite upset. He knew all too well that he wouldn’t survive for many minutes after such time as his fortune in diamonds became general knowledge.

‘What do you want from me?’ he said in a pitiful voice.

‘I want to be able to come here and spell my way through books without the need to bring a new pair of scissors each day. Scissors are expensive for those of us who have mouths full of teeth instead of other things.’

‘Can’t you just go away?’ said Thabo. ‘You can have one of the diamonds if you leave me alone.’

He had bribed his way out of things before, but not this time. Nombeko said that she wasn’t going to demand any diamonds. Things that didn’t belong to her didn’t belong to her.

Much later, in another part of the world, it would turn out that life was more complicated than that.

* * *

Ironically enough, it was two women who ended Thabo’s life. They had grown up in Portuguese East Africa and supported themselves by killing white farmers in order to steal their money. This enterprise went well as long as the civil war was going on.

But when independence came and the country’s name changed to Mozambique, the farmers who were still left had forty-eight hours to leave. The women then had no other choice than to kill well-to-do blacks instead. As a business idea it was a much worse one, because nearly all the blacks with anything worth stealing belonged to the Marxist-Leninist Party, which was now in power. So it wasn’t long before the women were wanted by the state and hunted by the new country’s dreaded police force.

This was why they went south. And made it all the way to the excellent hideout of Soweto, outside Johannesburg.

If the advantage to South Africa’s largest shantytown was that one could get lost in the crowds (as long as one was black), the disadvantage was that each individual white farmer in Portuguese East Africa probably had greater resources than all the 800,000 inhabitants of Soweto combined (with the exception of Thabo). But still, the women each swallowed a few pills of various colours and set out on a killing spree. After a while they made their way to Sector B, and there, behind the row of latrines, they caught sight of a green shack among all the rusty brown and grey ones. A person who paints his shack green (or any other colour) surely has too much money for his own good, the women thought, and they broke in during the middle of the night, planted a knife in Thabo’s chest and twisted it. The man who had broken so many hearts found his own cut to pieces.

Once he was dead, the women searched for his money among all the damn books that were piled everywhere. What kind of fool had they killed this time?

But finally they found a wad of banknotes in one of the victim’s shoes, and another in the other one. And, imprudently enough, they sat down outside the shack to divide them up. The particular mixture of pills they had swallowed along with half a glass of rum caused the women to lose their sense of time and place. Thus they were still sitting there, each with a grin on her face, when the police, for once, showed up.

The women were seized and transformed into a thirty-year cost item in the South African correctional system. The banknotes they had tried to count disappeared early on in the chain of custody. Thabo’s corpse ended up lying where it was until the next day. In the South African police corps, it was a sport to make the next shift take care of each dead darky whenever possible.

Nombeko had been woken up in the night by the ruckus on the other side of the row of latrines. She got dressed, walked over, and realized more or less what had happened.

Once the police had departed with the murderers and all of Thabo’s money, Nombeko went into the shack.

‘You were a horrible person, but your lies were entertaining. I will miss you. Or at least your books.’

Upon which she opened Thabo’s mouth and picked out fourteen rough diamonds, just the number that fitted in the gaps left by all the teeth he’d lost.

‘Fourteen holes, fourteen diamonds,’ said Nombeko. ‘A little too perfect, isn’t it?’

Thabo didn’t answer. But Nombeko pulled up the linoleum and started digging.

‘Thought so,’ she said when she found what she was looking for.

Then she fetched water and a rag and washed Thabo, dragged him out of the shack, and sacrificed her only white sheet to cover the body. He deserved a little dignity, after all. Not much. But a little.

Nombeko immediately sewed all of Thabo’s diamonds into the seam of her only jacket, and then she went back to bed.

The latrine manager let herself sleep in the next day. She had a lot to process. When she stepped into the office at last, all of the latrine emptiers were there. In their boss’s absence they were on their third morning beer, and they had been underprioritizing work since the second beer, preferring instead to sit around judging Indians to be an inferior race. The cockiest of the men was in the middle of telling the story of the man who had tried to fix the leaky ceiling of his shack with cardboard.

Nombeko interrupted the goings-on, gathered up all the beer bottles that hadn’t yet been emptied, and said that she suspected her colleagues had nothing in their heads besides the very contents of the latrine barrels they were meant to be emptying. Were they really so stupid that they didn’t understand that stupidity was race-neutral?

The cocky man said that apparently the boss couldn’t understand that a person might want to have a beer in peace and quiet after the first seventy-five barrels of the morning, without also being forced to listen to nonsense about how we’re all so goddamn alike and equal.

Nombeko considered throwing a roll of toilet paper at his head in reply, but she decided that the roll didn’t deserve it. Instead she ordered them to get back to work.

Then she went home to her shack. And said to herself once again: What am I doing here?

She would turn fifteen the next day.

* * *

On her fifteenth birthday, Nombeko had a meeting with Piet du Toit of the sanitation department of the City of Johannesburg; it had been scheduled long ago. This time he was better prepared. He had gone through the accounting in detail. Take that, twelve-year-old.

‘Sector B has gone eleven per cent over budget,’ said Piet du Toit, and he looked at Nombeko over the reading glasses he really didn’t need, but which made him look older than he was.

‘Sector B has done no such thing,’ said Nombeko.

‘If I say that Sector B has gone eleven per cent over budget, then it has,’ said Piet du Toit.

‘And if I say that the assistant can only calculate according to his own lights, then he does. Give me a few seconds,’ said Nombeko, and she yanked Piet du Toit’s calculations from his hand, quickly looked through his numbers, pointed at row twenty, and said, ‘We received the discount I negotiated here in the form of excess delivery. If you assess that at the discounted de facto price instead of an imaginary list price, you will find that your eleven mystery percentage points no longer exist. In addition, you have confused plus and minus. If we were to calculate the way you want to do it, we would have been under budget by eleven per cent. Which would be just as incorrect, incidentally.’

Piet du Toit’s face turned red. Didn’t the girl know her place? What would things be like if just anyone could define right and wrong? He hated her more than ever, but he couldn’t think of anything to say. So he said, ‘We have been talking about you quite a bit at the office.’

‘Is that so,’ said Nombeko.

‘We feel that you are uncooperative.’

Nombeko realized that she was about to be fired, just like her predecessor.

‘Is that so,’ she said.

‘I’m afraid we must transfer you. Back to the permanent workforce.’

This was, in fact, more than her predecessor had been offered. Nombeko suspected that the assistant must have been in a good mood on this particular day.

‘Is that so,’ she said.

‘Is “is that so” all you have to say?’ Piet du Toit said angrily.

‘Well I could have told Mr du Toit what an idiot Mr du Toit is, of course, but getting him to understand this would be verging on the hopeless. Years among the latrine emptiers has taught me that. You should know that there are idiots here as well, Mr du Toit. Best just to leave so I never have to see you again,’ said Nombeko, and did just that.

She said what she said at such speed that Piet du Toit didn’t have time to react before the girl had slipped out of his hands. And going in among the shacks to search for her was out of the question. As far as he was concerned, she could keep herself hidden in all that rubbish until tuberculosis, drugs or one of the other illiterates killed her.

‘Ugh,’ said Piet du Toit, nodding at the bodyguard his father paid for.

Time to return to civilization.

Of course, Nombeko’s managerial position wasn’t the only thing to go up in smoke after that conversation with the assistant – so did her job, such as it was. And her last pay cheque, for that matter.

Her backpack was filled with her meagre possessions. It contained a change of clothes, three of Thabo’s books, and the twenty sticks of dried antelope meat she had just bought with her last few coins.

She had already read the books, and she knew them by heart. But there was something pleasant about books, about their very existence. It was sort of the same with her latrine-emptying colleagues, except the exact opposite.

It was evening, and there was a chill in the air. Nombeko put on her only jacket. She lay down on her only mattress and pulled her only blanket over her (her only sheet had just been used as a shroud). She would leave the next morning.

And she suddenly knew where she would go.

She had read about it in the paper the day before. She was going to 75 Andries Street in Pretoria.

The National Library.

As far as she knew, it wasn’t an area that was forbidden for blacks, so with a little luck she could get in. What she could do beyond that, aside from breathing and enjoying the view, she didn’t know. But it was a start. And she felt that literature would lead her onward.

With that certainty, she fell asleep for the last time in the shack she had inherited from her mother five years previously. And she did so with a smile.

That had never happened before.

When morning came, she took off. The road before her was not a short one. Her first-ever walk beyond Soweto would be fifty-five miles long.

After just over six hours, and after sixteen of the fifty-five miles, Nombeko had arrived in central Johannesburg. It was another world! Just take the fact that most of the people around her were white and strikingly similar to Piet du Toit, every last one. Nombeko looked around with great interest. There were neon signs, traffic lights and general chaos. And shiny new cars, models she had never seen before. As she turned round to discover more, she saw that one of them was headed straight for her, speeding along the pavement.

Nombeko had time to think that it was a nice car.

But she didn’t have time to move out of the way.

* * *

Engineer Engelbrecht van der Westhuizen had spent the afternoon in the bar of the Hilton Plaza Hotel on Quartz Street. Then he got into his new Opel Admiral and set off, heading north.

But it is not and never has been easy to drive a car with a litre of brandy in one’s body. The engineer didn’t make it farther than the next intersection before he and the Opel drifted onto the pavement and – shit! – wasn’t he running over a Kaffir?

The girl under the engineer’s car was named Nombeko and was a former latrine emptier. Fifteen years and one day earlier she had come into the world in a tin shack in South Africa’s largest shantytown. Surrounded by liquor, thinner and pills, she was expected to live for a while and then die in the mud among the latrines in Soweto’s Sector B.

Out of all of them, Nombeko was the one to break loose. She left her shack for the first and last time.

And then she didn’t make it any farther than central Johannesburg before she was lying under an Opel Admiral, ruined.

Was that all? she thought before she faded into unconsciousness.

But it wasn’t.

CHAPTER 2

On how everything went topsy-turvy in another part of the world

Nombeko was run over on the day after her fifteenth birthday. But she survived. Things would get better. And worse. Above all, they would get strange.

Of all the men she would be subjected to in the years to come, Ingmar Qvist from Södertälje, Sweden, six thousand miles away, was not one of them. But all the same, his fate would hit her with full force.

It’s hard to say exactly when Ingmar lost his mind, because it sneaked up on him. But it is clear that by the autumn of 1947 it was well on its way. It is also clear that neither he nor his wife realized what was going on.

Ingmar and Henrietta got married while almost all of the world was still at war and moved to a plot of land in the forest outside Södertälje, almost twenty miles southwest of Stockholm.

He was a low-level civil servant; she was an industrious seamstress who took in work at home.

They met for the first time outside Room 2 of Södertälje District Court, where a dispute between Ingmar and Henrietta’s father was being handled: the former had happened, one night, to paint LONG LIVE THE KING! in three-foot-high letters along one wall of the meeting hall of Sweden’s Communist Party. Communism and the royal family don’t generally go hand in hand, of course, so naturally there was quite an uproar at dawn the next day when the Communists’ main man in Södertälje – Henrietta’s father – discovered what had happened.

Ingmar was quickly seized – extra quickly, since after his prank he had lain down to sleep on a park bench not far from the police station, with paint and brush in hand.

In the courtroom, sparks had flown between the defending Ingmar and the spectating Henrietta. This was probably partly because she was tempted by the forbidden fruit, but above all it was because Ingmar was so… full of life… unlike her father, who just went around waiting for everything to go to hell so that he and Communism could take over, at least in Södertälje. Her father had always been a revolutionary, but after 7 April 1937, when he signed what turned out to be the country’s 999,999th radio licence, he also became bitter and full of dark thoughts. A tailor in Hudiksvall, two hundred miles away, was celebrated the very next day for having signed the millionth licence. The tailor received not only fame (he got to be on the radio!) but also a commemorative silver trophy worth six hundred kronor. All while Henrietta’s dad got nothing more than a long face.

He never got over this event; he lost his (already limited) ability to see the humour in anything, not least the prank of paying tribute to King Gustaf V on the wall of the Communist Party’s meeting place. He argued the party’s case in court himself and demanded eighteen years of prison for Ingmar Qvist, who was instead sentenced to a fine of fifteen kronor.

Henrietta’s father’s misfortune knew no bounds. First the radio licences. And the relative disappointment in Södertälje District Court. And his daughter, who subsequently fell into the arms of the Royalist. And, of course, the cursed capitalism, which always seemed to land on its feet.

When Henrietta went on to decide that she and Ingmar would marry in the church, Södertälje’s Communist leader broke off contact with his daughter once and for all, upon which Henrietta’s mother broke off contact with Henrietta’s father, met a new man – a German military attaché – at Södertälje Station, moved to Berlin with him just before the war ended, and was never heard from again.

Henrietta wanted to have children, preferably as many as possible. Ingmar thought this was basically a good idea, not least because he appreciated the method of production. Just think of that very first time, in the back of Henrietta’s father’s car, two days after the trial. That had been something, all right, although Ingmar had had to pay for it – he hid in his aunt’s cellar while his father-in-law-to-be searched all over Södertälje for him. Ingmar shouldn’t have left that used condom in the car.

Oh well, what’s done is done. And anyway, it was a blessing that he’d happened across that box of condoms for American soldiers, because things had to be done in the proper order so that nothing would go wrong.

But by this Ingmar did not mean making himself a career so he could support a family. He worked at the post office in Södertälje, or the ‘Royal Mail Service’, as he liked to say. His salary was average, and there was every chance that it would stay that way.

Henrietta earned nearly double what her husband did, because she was clever and quick with both needle and thread. She had a large and regular clientele; the family would have lived very comfortably if it weren’t for Ingmar and his ever-growing talent for squandering everything Henrietta managed to save.

Again, children would be great, but first Ingmar had to fulfil his life’s mission, and that took focus. Until his mission was completed, there mustn’t be any extraneous side projects.

Henrietta protested her husband’s choice of words. Children were life itself and the future – not a side project.

‘If that’s how you feel, then you can take your box of American soldiers’ condoms and sleep on the kitchen sofa,’ she said.

Ingmar squirmed. Of course he didn’t mean that children were extraneous, it was just that… well, Henrietta already knew what. It was, of course, this matter of His Majesty the King. He just had to get that out of the way first. It wouldn’t take for ever.

‘Dear, sweet Henrietta. Can’t we sleep together again tonight? And maybe do a little practising for the future?’

Henrietta’s heart melted, of course. As it had so many times before and as it would many times yet to come.

What Ingmar called his life’s mission was to shake the hand of the King of Sweden. It had started as a wish, but had developed into a goal. The precise moment at which it became a true obsession was, as previously mentioned, not easy to say. It was easier to explain where and when the whole thing started.

On Saturday, 16 June 1928, His Majesty King Gustaf V celebrated his seventieth birthday. Ingmar Qvist, who was fourteen at the time, went with his mother and father to Stockholm to wave the Swedish flag outside the palace and then go to Skansen Museum and Zoo – where they had bears and wolves!

But their plans changed a bit. It turned out to be far too crowded at the palace; instead the family stood along the procession route a few hundred yards away, where the king and his Victoria were expected to pass by in an open carriage.

And so they did. At which point everything turned out better than Ingmar’s mother and father could ever have imagined. Because just next to the Qvist family were twenty students from Lundsbergs Boarding School; they were there to give a bouquet of flowers to His Majesty as thanks for the support the school received, not least because of the involvement of Crown Prince Gustaf Adolf. It had been decided that the carriage would stop briefly so that His Majesty could step down, receive the flowers and thank the children.

Everything went as planned and the king received his flowers, but when he turned to step up into the carriage again he caught sight of Ingmar. And stopped short.

‘What a beautiful lad,’ he said, and he took two steps up to the boy and tousled his hair. ‘Just a second – here you go,’ he went on, and from his inner pocket he took a sheet of commemorative stamps that had just been released for the king’s special day.

He handed the stamps to young Ingmar, smiled, and said, ‘I could eat you right up.’ Then he tousled the boy’s hair once more before he climbed up to the furiously glaring queen.

‘Did you say “thank you”, Ingmar?’ asked his mother once she’d recovered from the fact that the king had touched her son – and given him a present.

‘No-o,’ Ingmar stammered as he stood there with stamps in hand. ‘No, I didn’t say anything. It was like he was… too grand to talk to.’

The stamps became Ingmar’s most cherished possession, of course. And two years later he started working at the post office in Södertälje. He started out as a clerk of the lowest rank possible in the accounting department; sixteen years later he had climbed absolutely nowhere.

Ingmar was infinitely proud of the tall, stately monarch. Every day, Gustaf V stared majestically past him from all the stamps the subject had reason to handle at work. Ingmar gazed humbly and lovingly back as he sat there in the Royal Mail Service’s royal uniform, even though it was not at all necessary to wear it in the accounting department.

But there was just this one issue: the king was looking past Ingmar. It was as if he didn’t see his subject and therefore couldn’t receive the subject’s love. Ingmar so terribly wanted to be able to look the king in the eye. To apologize for not saying ‘thank you’ that time when he was fourteen. To proclaim his eternal loyalty.

‘So terribly’ was right. It became more and more important… the desire to look him in the eye, speak with him, shake his hand.

More and more important.

And even more important.

His Majesty, of course, was only getting older. Soon it would be too late. Ingmar Qvist could no longer just wait for the king to march into the Södertälje Post Office one day. That had been his dream all these years, but now he was about to wake up from it.

The king wasn’t going to seek out Ingmar.

Ingmar had no choice but to seek out the king.

Then he and Henrietta would make a baby, he promised.

* * *

The Qvist family’s already poor existence kept getting poorer and poorer. The money kept disappearing, thanks to Ingmar’s attempts to meet the king. He wrote veritable love letters (with an unnecessarily large number of stamps on them); he called (without getting further than some poor royal secretary, of course); he sent presents in the form of Swedish silversmith products, which were the king’s favourite things (and in this way he supported the not entirely honest father of five who had the task of registering all incoming royal gifts). Beyond this, he went to tennis matches and nearly all of the functions one could imagine the king might attend. This meant many expensive trips and admission tickets, yet Ingmar never came very close to meeting his king.

Nor were the family finances fortified when Henrietta, as a result of all her worrying, started doing what almost everyone else did at the time – that is, smoking one or more packets of John Silvers per day.

Ingmar’s boss at the accounting department of the post office was very tired of all the talk about the damn monarch and his merits. So whenever junior clerk Qvist asked for time off, he granted it even before Ingmar had managed to finish formulating his request.

‘Um, boss, do you think it might be possible for me to have two weeks off work, right away? I’m going to—’

‘Granted.’

People had started calling Ingmar by his initials instead of his name. He was ‘IQ’ among his superiors and colleagues.

‘I wish you good luck in whatever kind of idiocy you’re planning to get up to this time, IQ,’ said the head clerk.

Ingmar didn’t care that he was being made fun of. Unlike the other workers at postal headquarters in Södertälje, his life had meaning and purpose.

It took another three considerable undertakings on Ingmar’s part before absolutely everything went topsy-turvy.

First he made his way to Drottningholm Palace, stood up straight in his postal uniform, and rang the bell.

‘Good day. My name is Ingmar Qvist. I am from the Royal Mail Service, and it so happens that I need to see His Majesty himself. Could you be so kind as to notify him? I will wait here,’ said Ingmar to the guard at the gate.

‘Do you have a screw loose or something?’ the guard said in return.

A fruitless dialogue ensued, and in the end Ingmar was asked to leave immediately; otherwise the guard would make sure that Mr Postal Clerk was packaged up and delivered right back to the post office whence he came.

Ingmar was offended and in his haste happened to mention the size he would estimate the guard’s genitalia to be, whereupon he had to run away with the guard on his tail.

He got away, partly because he was a bit faster than the guard, but most of all because the latter had orders never to leave the gate and so had to turn back.

After that, Ingmar spent two whole days sneaking around outside the ten-foot fence, out of sight of the oaf at the gate, who refused to understand what was best for the king, before he gave up and went back to the hotel that served as his base for the entire operation.

‘Should I prepare your bill?’ asked the receptionist, who had long since suspected that this particular guest was not planning to do the right thing and pay.

‘Yes, please,’ said Ingmar, and he went to his room, packed his suitcase, and checked out via the window.

The second considerable undertaking before everything went topsy-turvy began when Ingmar read a news item in Dagens Nyheter while hiding from work by sitting on the toilet. The news item said that the king was in Tullgarn for a few days of relaxing moose hunting. Ingmar rhetorically asked himself where there were moose if not out in God’s green nature, and who had access to God’s green nature if not… everyone! From kings to simple clerks at the Royal Mail Service.

Ingmar flushed the toilet for the sake of appearances and went to ask for another leave of absence. The head clerk granted his request with the frank comment that he hadn’t even noticed that Mr Qvist was already back from the last one.

It had been a long time since Ingmar had been entrusted to rent a car in Södertälje, so first he had to take the bus all the way to Nyköping, where his honest looks were enough to get him a decent second-hand Fiat 518. He subsequently departed for Tullgarn at the speed allowed by the power of forty-eight horses.

But he didn’t get more than halfway there before he met a black 1939 Cadillac V8 coming from the other direction. The king, of course. Finished hunting. About to slip out of Ingmar’s hands yet again.

Ingmar turned his borrowed Fiat round in the blink of an eye, was helped along by several downhill stretches in a row, and caught up with the hundred-horsepower-stronger royal car. The next step would be to try to pass the car and maybe pretend to break down in the middle of the road.

But the anxious royal chauffeur speeded up so he wouldn’t have to endure the wrath he expected the king to exhibit should they be passed by a Fiat. Unfortunately, he was looking at the rear-view mirror more than he was looking ahead, and at a curve in the road, the chauffeur, along with Cadillac, king, and companions, kept going straight, down into a waterlogged ditch.

Neither Gustaf V nor anyone else was harmed, but Ingmar had no way of knowing this from behind his steering wheel. His first thought was to jump out and help, and also shake the king’s hand. But his second thought was: what if he had killed the old man? And his third thought: thirty years of hard labour – that might be too high a price for a handshake. Especially if the hand in question belonged to a corpse. Ingmar didn’t think he would be very popular in the country, either. Murderers of kings seldom were.

So he turned round.

He left the hire car outside the Communists’ meeting hall in Södertälje, in the hope that his father-in-law would get the blame. From there he walked all the way home to Henrietta and told her that he might have just killed the king he loved so dearly.

Henrietta consoled him by saying that everything was probably fine down there at the king’s curve, and in any case it would be a good thing for the family finances if she were wrong.

The next day, the press reported that King Gustaf V had ended up in the ditch after his car had been driven at high speeds, but that he was unharmed. Henrietta had mixed feelings upon hearing this, but she thought that perhaps her husband had learned an important lesson. And so she asked, full of hope, if Ingmar was done chasing the king.

He was not.

The third considerable undertaking before everything went topsy-turvy involved a journey to the French Riviera for Ingmar; he was going to Nice, where Gustaf V, age eighty-eight, always spent the late autumn to get relief from his chronic bronchitis. In a rare interview, the king had said that when he wasn’t taking his daily constitutional at a leisurely pace along the Promenade des Anglais, he spent the days sitting on the terrace of his state apartment at the Hôtel d’Angleterre.

This was enough information for Ingmar. He would travel there, run across the king while he was on his walk and introduce himself.

It was impossible to know what would happen next. Perhaps the two men would stand there for a while and have a chat, and if they hit it off perhaps Ingmar could buy the king a drink at the hotel that evening. And why not a game of tennis the next day?

‘Nothing can go wrong this time,’ Ingmar said to Henrietta.

‘That’s nice,’ said his wife. ‘Have you seen my cigarettes?’

Ingmar hitchhiked his way through Europe. It took a whole week, but once he was in Nice it took only two hours of sitting on a bench on the Promenade des Anglais before he caught sight of the tall, stately gentleman with the silver cane and the monocle. God, he was so grand! He was approaching slowly. And he was alone.

What happened next was something Henrietta could describe in great detail many years later, because Ingmar would dwell on it for the rest of her life.

Ingmar stood up from his bench, walked up to His Majesty, introduced himself as the loyal subject from the Royal Mail Service that he was, broached the possibility of a drink together and maybe a game of tennis – and concluded by suggesting that the two men shake hands.

The king’s reaction, however, had not been what Ingmar expected. For one thing, he refused to take this unknown man’s hand. For another, he didn’t condescend to look at him. Instead he looked past Ingmar into the distance, just as he had already done on all the tens of thousands of stamps Ingmar had had reason to handle in the course of his work. And then he said that he had no intention, under any circumstances, of socializing with a messenger boy from the post office.

Strictly speaking, the king was too stately to say what he thought of his subjects. He had been drilled since childhood in the art of showing his people the respect they generally didn’t deserve. But he said what he thought now, partly because he hurt all over and partly because keeping it to himself all his life had taken its toll.

‘But Your Majesty, you don’t understand,’ Ingmar tried.

‘If I were not alone I would have asked my companions to explain to the scoundrel before me that I certainly do understand,’ said the king, and in this way even managed to avoid speaking directly to the unfortunate subject.

‘But,’ Ingmar said – and that was all he managed to say before the king hit him on the forehead with his silver cane and said, ‘Come, come!’

Ingmar landed on his bottom, thus enabling the king to pass safely. The subject remained on the ground as the king walked away.

Ingmar was crushed.

For twenty-five seconds.

Then he cautiously stood up and stared after his king for a long time. And he stared a little longer.

‘Messenger boy? Scoundrel? I’ll show you messenger boy and scoundrel.’

And thus everything had gone topsy-turvy.

CHAPTER 3

On a strict sentence, a misunderstood country and three multifaceted girls from China

According to Engelbrecht van der Westhuizen’s lawyer, the black girl had walked right out into the street, and the lawyer’s client had had no choice but to swerve. Thus the accident was the girl’s fault, not his. Engineer van der Westhuizen was a victim, nothing more. Besides, she had been walking on a pavement meant for whites.

The girl’s assigned lawyer offered no defence because he had forgotten to show up in court. And the girl herself preferred not to say anything, largely because she had a jaw fracture that was not conducive to conversation.

Instead, the judge was the one to defend Nombeko. He informed Mr van der Westhuizen that he’d had at least five times the legal limit of alcohol in his bloodstream, and that blacks were certainly allowed to use that pavement, even if it wasn’t considered proper. But if the girl had wandered into the street – and there was no reason to doubt that she had, since Mr van der Westhuizen had said under oath that this was the case – then the blame rested largely on her.

Mr van der Westhuizen was awarded five thousand rand for bodily injury as well as another two thousand rand for the dents the girl had caused to appear on his car.

Nombeko had enough money to pay the fine and the cost of any number of dents. She could also have bought him a new car, for that matter. Or ten new cars. The fact was, she was extremely wealthy, but no one in the courtroom or anywhere else would have had reason to assume this. Back in the hospital she had used her one functioning arm to make sure that the diamonds were still in the seam of her jacket.

But her main reason for keeping this quiet was not her fractured jaw. In some sense, after all, the diamonds were stolen. From a dead man, but still. And as yet they were diamonds, not cash. If she were to remove one of them, all of them would be taken from her. At best, she would be locked up for theft; at worst, for conspiracy to robbery and murder. In short, the situation she found herself in was not simple.

The judge studied Nombeko and read something else in her expression of concern. He stated that the girl didn’t appear to have any assets to speak of and that he could sentence her to pay off her debt in the service of Mr van der Westhuizen, if the engineer found this to be a suitable arrangement. The judge and the engineer had made a similar arrangement once before, and that was working out satisfactorily, wasn’t it?

Engelbrecht van der Westhuizen shuddered at the memory of what had happened when he ended up with three Chinks in his employ, but these days they were useful to a certain extent – and by all means, perhaps throwing a darky into the mix would liven things up. Even if this particular one, with a broken leg, broken arm and her jaw in pieces might mostly be in the way.

‘At half salary, in that case,’ he said. ‘Just look at her, Your Honour.’ Engineer Engelbrecht van der Westhuizen suggested a salary of five hundred rand per month minus four hundred and twenty rand for room and board. The judge nodded his assent.

Nombeko almost burst out laughing. But only almost, because she hurt all over. What that fat-arse of a judge and liar of an engineer had just suggested was that she work for free for the engineer for more than seven years. This, instead of paying a fine that would hardly add up to a measurable fraction of her collected wealth, no matter how absurdly large and unreasonable it was.

But perhaps this arrangement was the solution to Nombeko’s dilemma. She could move in with the engineer, let her wounds heal and run away on the day she felt that the National Library in Pretoria could no longer wait. After all, she was about to be sentenced to domestic service, not prison.

She was considering accepting the judge’s suggestion, but she bought herself a few extra seconds to think by arguing a little bit, despite her aching jaw: ‘That would mean eighty rand per month net pay. I would have to work for the engineer for seven years, three months and twenty days in order to pay it all back. Your Honour, don’t you think that’s a rather harsh sentence for a person who happened to get run over on a pavement by someone who shouldn’t even have been driving on the street, given his alcohol intake?’

The judge was completely taken aback. It wasn’t just that the girl had expressed herself. And expressed herself well. And called the engineer’s sworn description of events into question. She had also calculated the extent of the sentence before anyone else in the room had been close to doing so. He ought to chastise the girl, but… he was too curious to know whether her calculations were correct. So he turned to the court aide, who confirmed, after a few minutes, that ‘Indeed, it looks like we’re talking about – as we heard – seven years, three months, and… yes… about twenty days or so.’

Engelbrecht van der Westhuizen took a gulp from the small brown bottle of cough medicine he always had with him in situations where one couldn’t simply drink brandy. He explained this gulp by saying that the shock of the horrible accident must have exacerbated his asthma.

But the medicine did him good: ‘I think we’ll round down,’ he said. ‘Exactly seven years will do. And anyway, the dents on the car can be hammered out.’

Nombeko decided that a few weeks or so with this Westhuizen was better than thirty years in prison. Yes, it was too bad that the library would have to wait, but it was a very long walk there, and most people would prefer not to undertake such a journey with a broken leg. Not to mention all the rest. Including the blister that had formed as a result of the first sixteen miles.

In other words, a little break couldn’t hurt, assuming the engineer didn’t run her over a second time.

‘Thanks, that’s generous of you, Engineer van der Westhuizen,’ she said, thereby accepting the judge’s decision.

‘Engineer van der Westhuizen’ would have to do. She had no intention of calling him ‘baas.’

* * *

Immediately following the trial, Nombeko ended up in the passenger seat beside Engineer van der Westhuizen, who headed north, driving with one hand while swigging a bottle of Klipdrift brandy with the other. The brandy was identical in odour and colour to the cough medicine Nombeko had seen him drain during the trial.

This took place on 16 June 1976.

On the same day, a bunch of school-aged adolescents in Soweto got tired of the government’s latest idea: that their already inferior education should henceforth be conducted in Afrikaans. So the students went out into the streets to air their disapproval. They were of the opinion that it was easier to learn something when one understood what one’s instructor was saying. And that a text was more accessible to the reader if one could interpret the text in question. Therefore – said the students – their education should continue to be conducted in English.

The surrounding police listened with interest to the youths’ reasoning, and then they argued the government’s point in that special manner of the South African authorities.

By opening fire.

Straight into the crowd of demonstrators.

Twenty-three demonstrators died more or less instantly. The next day, the police advanced their argument with helicopters and tanks. Before the dust had settled, another hundred human lives had been extinguished. The City of Johannesburg’s department of education was therefore able to adjust Soweto’s budgetary allocations downward, citing lack of students.

Nombeko avoided experiencing any of this. She had been enslaved by the state and was in a car on the way to her new master’s house.

‘Is it much farther, Mr Engineer?’ she asked, mostly to have something to say.

‘No, not really,’ said Engineer van der Westhuizen. ‘But you shouldn’t speak out of turn. Speaking when you are spoken to will be sufficient.’

Engineer Westhuizen was a lot of things. The fact that he was a liar had become clear to Nombeko back in the courtroom. That he was an alcoholic became clear in the car after leaving the courtroom. In addition, he was a fraud when it came to his profession. He didn’t understand his own work, but he kept himself at the top by telling lies and exploiting people who did understand it.

This might have been an aside to the whole story if only the engineer hadn’t had one of the most secret and dramatic tasks in the world. He was the man who would make South Africa a nuclear weapons nation. It was all being orchestrated from the research facility of Pelindaba, about an hour north of Johannesburg.

Nombeko, of course, knew nothing of this, but her first inkling that things were a bit more complicated than she had originally thought came as they approached the engineer’s office.

Just as the Klipdrift ran out, she and the engineer arrived at the facility’s outer perimeter. After showing identification they were allowed to enter the gates, passing a ten-foot, twelve-thousand-volt fence. Next there was a fifty-foot stretch that was controlled by double guards with dogs before it was time for the inner perimeter and the next ten-foot fence with the same number of volts. In addition, someone had thought to place a minefield around the entire facility, in the space between the ten-foot fences.

‘This is where you will atone for your crime,’ said the engineer. ‘And this is where you will live, so you don’t take off.’

Electric fences, guards with dogs and minefields were variables Nombeko hadn’t taken into account in the courtroom a few hours earlier.

‘Looks cosy,’ she said.

‘You’re talking out of turn again,’ said the engineer.

* * *

The South African nuclear weapons programme was begun in 1975, the year before a drunk Engineer van der Westhuizen happened to run over a black girl. There were two reasons he had been sitting at the Hilton Hotel and tossing back brandies until he was gently asked to leave. One was that part about being an alcoholic. The engineer needed at least a full bottle of Klipdrift per day to keep the works going. The other was his bad mood. And his frustration. The engineer had just been pressured by Prime Minister Vorster, who complained that no progress had been made yet even though a year had gone by.

The engineer tried to maintain otherwise. On the business front, they had begun the work exchange with Israel. Sure, this had been initiated by the prime minister himself, but in any case uranium was heading in the direction of Jerusalem, while they had received tritium in return. There were even two Israeli agents permanently stationed at Pelindaba for the sake of the project.

No, the prime minister had no complaints about their collaboration with Israel, Taiwan and others. It was the work itself that was limping along. Or, as the prime minister put it:

‘Don’t give us a bunch of excuses for one thing and the next. Don’t give us any more teamwork right and left. Give us an atomic bomb, for fuck’s sake, Mr van der Westhuizen. And then give us five more.’

* * *

While Nombeko settled in behind Pelindaba’s double fence, Prime Minister Balthazar Johannes Vorster was sitting in his palace and sighing. He was very busy from early in the morning to late at night. The most pressing matter on his desk right now was that of the six atomic bombs. What if that obsequious Westhuizen wasn’t the right man for the job? He talked and talked, but he never delivered.

Vorster muttered to himself about the damn UN, the Communists in Angola, the Soviets and Cuba sending hordes of revolutionaries to southern Africa, and the Marxists who had already taken over in Mozambique. Plus those CIA bastards who always managed to figure out what was going on, and then couldn’t shut up about what they knew.