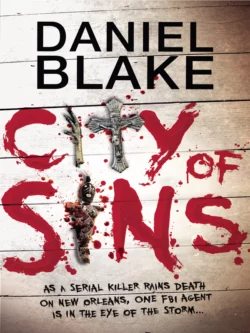

City of Sins

Daniel Blake

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 401.15 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The pulse-pounding thriller featuring FBI agent Franco Patrese, in New Orleans on the hunt for a warped serial killer as Hurricane Katrina threatens the city.Franco Patrese is intrigued when the attractive PA to New Orleans’ richest man requests a clandestine meeting. She has information regarding an unthinkable conspiracy, and will trust no-one else.The next day she’s dead – the victim of a bizarre ritual murder – and Patrese finds himself drawn into the murkiest of underworlds, piecing together connections between the city’s seediest players and her top officials.Only two certainties remain – devastating secrets are hidden in these cesspools of corruption and crime, and some people will do anything to keep them that way.And all the while, the city’s apocalypse looms. Her name is Katrina, and she’s taking aim…