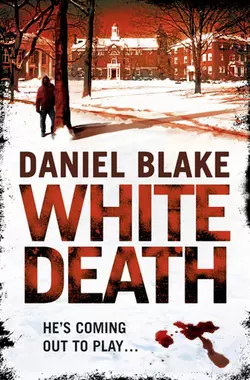

White Death

Daniel Blake

The heart-stopping new thriller featuring FBI Special Agent Frank Patrese, on the trail of a crazed serial killer targeting Ivy League colleges.ONE GAMETwo weeks before Kwasi King, chess’s answer to Muhammad Ali, is due to defend his world title, his mother is found brutally murdered yards from Yale University. A tarot card has been left next to her dismembered body.TWO PLAYERSSoon, more bodies turn up at other Ivy League colleges, all with tarot cards. But while some have been killed in a frenzy, others were dispatched with clinical precision. It looks like FBI Special Agent Franco Patrese’s looking for not just one killer, but two.CHECK MATEAnd while Patrese hunts, he knows that he too is being hunted, for he’s received his own tarot card. The Fool. Could he be the next victim of this macabre intellectual battle?

Table of Contents

Title Page (#ua5e6ec23-f65b-57ea-a0de-d8598bf157a3)

Dedication (#ub428fb3d-d92f-52ca-a73a-defb1dcbbd0c)

Acknowledgements (#ub860b2a9-ab75-518f-86ea-297624d1dc31)

Part One: Opening (#u68879991-29e2-5c41-903b-2b0bf0414612)

Chapter 1 (#ue40ee296-8d8a-571c-b16e-72603537529f)

Chapter 2 (#u1e0f0c53-43ab-5ded-bdd9-a484d783f821)

Chapter 3 (#u5f22818a-e384-501c-9f66-7d51c596ee2c)

Chapter 4 (#u20c01a8c-ec80-5485-a485-9e43975b1e9f)

Chapter 5 (#u8ac5363f-d880-51c2-a6d5-1eb5edfde1d9)

Chapter 6 (#u0f5d6044-ca4c-5638-bb64-aa3d7f66b02e)

Chapter 7 (#u21ba3ff3-043b-569b-a587-723a6052c36c)

Chapter 8 (#uec61a3cd-6d98-54db-b8d4-cb5f4864a323)

Chapter 9 (#ue3873fe2-00b1-56be-ac77-9a8947956381)

Chapter 10 (#u8e3d082a-2e51-5cc4-b146-88d606b67b64)

Chapter 11 (#u8b2d6334-dc6d-57ff-bbcc-119e345e7701)

Chapter 12 (#u75659c5a-f6a5-50d9-b3e8-aa51c07bc2cd)

Chapter 13 (#u7d5c9355-e71a-5688-bebe-1c33f55260dc)

Chapter 14 (#u1a8894c6-5f3e-5a74-9fa0-fe47d14f22ea)

Chapter 15 (#u17186a14-3248-5f28-a3eb-c0d6655b3f7f)

Chapter 16 (#u6ac48c58-eb85-5bf0-8379-1bfa1d85fc4d)

Chapter 17 (#ua8d04c79-d3b3-545c-9454-045e9a49d1ca)

Chapter 18 (#uc617a8ad-f36e-5145-9435-30d49a378d09)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two: Middlegame (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 52 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 53 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 54 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 55 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 56 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: Endgame (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 57 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 58 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 59 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 60 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 61 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 62 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 63 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 64 (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

For Caradoc

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#ulink_0e362b1a-34e7-55ea-9d03-5334b4c87eec)

Thanks to: Sarah, Julia, Emad, Kate and Anne at HarperCollins; Caradoc, Yasmin, Linda, Louise and Elinor at A.P. Watt; Charlotte, Judy and David Starling; John Saunders and the gentlemen and players of the José Raúl Capablanca Memorial Chess Society.

PART ONE (#ulink_881b94ce-e590-5f44-b190-7b9db4532215)

Opening (#ulink_881b94ce-e590-5f44-b190-7b9db4532215)

‘Play the opening like a book.’

Rudolf Spielmann, Austrian chess player

(1883–1942)

1 (#ulink_b8c40ee8-3ac1-54e1-a99a-18bd76d21a9f)

It’s not hard to shrink a human head.

First, you make a slit up the back. (Well, first you sever the head from the body, but I guess you figured that out already.) Then, you peel the skin and hair away from the skull. Slow and careful does it: you gotta keep it all in one piece, else you’ll spend hours tryin’ to make it right again, and even then it won’t look quite the same. And it’s not like human heads grow on trees, and you can just go out and find another one. So take your time and get it right. Sorry to sound all bossy, but it’s gotta be said.

You don’t need the skull no more, least not for this process, so do what you want with it. Chuck it away (someone else’s dumpster’s better than your own, in case the cops come knockin’), or, I don’t know, put a candle in it, save it for Hallowe’en, give it to the next guy you know playin’ Hamlet, whatever.

But you still need somethin’ to keep the head’s shape, so put a wooden ball in where the skull used to be. Sew the eyelids shut; the finer the thread the better. You need delicate fingers; think piano players rather than piano movers. Close the lips and skewer ’em with little palm pins, the kind you get on dog brushes.

Then take the head over to the stove, put it in a cookin’ pot, and simmer for a couple of hours – no more, you hear, not unless you want all the hair to fall out and the skin to end up as dry and cracked as a summer riverbed. A couple of hours, and the skin’ll look and feel like dark rubber. That’s what you’re aimin’ at. Take it out the cookpot, remove the wooden ball, flip the skin inside out and scrape out all the gunk and fat on the inside. Flip it back again and sew shut the slit you made at the back to kick this whole thing off.

You don’t need the wooden ball no more today, but of course keep it close to hand if you’re plannin’ on shrinkin’ more heads any time soon.

Now you need a heap of hot stones, to shrink the head even more and sear its inside clean. Drop the stones through the neck openin’, one at a time. Make sure you keep movin’ ’em around, else you’ll leave scorch marks. When you got too many stones in there to keep rollin’ ’em around nice and easy, take ’em all back out, one by one.

The stones all gone, tip hot sand into the head. The sand gets in the places the stones can’t reach, the little crevices of the nose and ears. Attention to detail, folks. But you ain’t finished with the stones yet, no sir. You press ’em to the outside of the face: shape and seal, shape and seal. Gotta keep those features lookin’ good. Think of it like moldin’ a clay face, like you’re Patrick Swayze and Demi Moore in Ghost. Love that movie.

Singe off any excess hair and cover the face in charcoal ash. This is supposed to let you harness the dead person’s spirit to your own ends; you don’t put on the ash, the soul’ll seep out and avenge the death. That’s what the old-timers say, at any rate. Not sure I believe ’em, but what the hell. Can’t do any harm, can it?

The head should be about the size of an orange by now. Hang it over a fire to harden properly, and you’re done. You can do what you want with it now.

Like I said, not hard. Not hard at all.

2 (#ulink_4560718e-7de1-520c-a13f-ada08c71a9ba)

Sunday, October 31st

Foxborough, MA

There are several types of hangover. There’s Hangover Lite, a mild but insistent ache in the temples; there’s Hangover Medium, where you ride greasy swells of nausea which rear and ebb without warning; and there’s Hangover Max, when a team of roadworkers are jackhammering behind your eyes, your heart is doing a one-man Indy 500, and the thought that you might die is eclipsed only by the fear that you won’t.

And then there’s the kind of hangover Franco Patrese had at the precise moment his cellphone jolted him from sleep with a brutality that was borderline sociopathic.

But Patrese was a pro. In the time it took for the phone to ring once, neither the shock of the rude awakening nor the monumental combination of toxins gleefully racing round his body could prevent him from assembling a few salient points.

First, it was still dark outside.

Second, he was in a hotel room, which he remembered as being on the outskirts of Foxborough, Massachusetts.

Third, there was another bed in the room, and in that bed was a man named Jeff whose snoring had the rhythm and persistence of waves breaking on a shore. Jeff was one of Patrese’s college buddies. A whole bunch of them had hooked up to come see their beloved Pittsburgh Steelers play the New England Patriots in Foxborough this coming afternoon, and, as Patrese hadn’t seen much of his old friends since moving down to New Orleans, they’d decided to make a weekend of it, all boys together. For someone like Patrese, a single guy who lived in party central, this was just another weekend of good times. For those of his buddies who were married with kids, and whose usual weekends were therefore kids’ soccer practice, home-improvement jobs and putting up with the in-laws, this was pretty much their only free time all year, and by hell they’d made the most of it.

Fourth, Patrese had been first a cop and then an FBI agent for more than a decade, so he knew that no one rang that early on a Sunday morning unless there was a good reason for it. And nine times out of ten, a good reason means something bad has happened.

He answered on the second ring. ‘Patrese.’

Well, ‘Patrese’ was what he’d wanted to say. ‘Ngfrujghr’ was how it had actually come out.

‘Hello?’ It was a woman’s voice. ‘I’m looking for Franco Patrese?’

Bile rose fast and hard in Patrese’s throat. He took a deep breath and forced it back down. This time when he opened his mouth to speak, his tongue felt like a desiccated slug.

‘Hello?’ said the woman again. ‘Hello?’

There was a glass of water by the bed. Patrese reached for it. Felt sick again. Hangover motion sickness, he thought: you move, you feel sick. No matter. He grabbed the glass and drank it down in one.

‘This is Patrese.’ His voice still sounded like Darth Vader with flu, but at least he was now speaking recognizable English.

‘Agent Patrese, my name is Lauren Kieseritsky. I’m with the police department in New Haven, Connecticut.’

No apology for waking him so early. Patrese didn’t expect one. Law enforcement personnel don’t apologize to each other for doing their jobs. In any case, Patrese was already trying to think. New Haven, Connecticut? He’d never been there in his life. Never been, didn’t know anyone there, probably couldn’t even point to it on a map.

‘I got your number through ViCAP,’ Kieseritsky continued.

Patrese sat straight up, nausea be damned. ViCAP is the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program, a Bureau database which collates information on violent crime, especially murder. ViCAP is linked to police and sheriff departments across the country. Local officers can enter details of crimes committed on their patch and see if these details match anything already in the system. ViCAP is particularly useful in catching serial killers, who often murder in different jurisdictions and over many years: crimes which beforehand had simply been written off as unrelated and insoluble.

ViCAP definitely meant something bad had happened.

‘What you got?’ Patrese asked.

‘Two bodies found an hour ago on the Green.’

‘The Green?’

‘Sorry. New Haven Green. Grass square, center of the city.’

‘OK.’

‘White man, black woman. No IDs on either yet, though we’ve taken fingerprints and are running them through the system. Both been decapitated. No sign of the heads. Both missing an arm. Both with skin taken from their chests and backs.’

‘The arms – that’s why you called me? Limb removal?’ Patrese’s first case as an agent in New Orleans had been a serial killer who, amongst other things, had amputated his victims’ left legs.

‘Yes, sir. Well, not just that.’

‘Then what?’

‘The dead man. We found him on the steps of a church, and he’s wearing a signet ring with a cross emblem on it. We think it’s the Benedictine medal. We think he’s a monk, a priest, something like that.’

Before Patrese had been a Bureau agent, he’d been a Pittsburgh cop. He’d taken down a killer nicknamed the Human Torch, whose victims had included a bishop – a bishop who, as a young priest, had befriended Patrese’s family and done the kind of things to a teenage Franco that no human being should ever inflict on another.

Patrese ran to the bathroom and threw up.

3 (#ulink_219be7cb-6ae8-5c1d-bbd0-67006ee019f5)

New Haven, CT

Early on Sunday morning, no traffic on the road and a crime scene to get to, it took Patrese dead on two hours to make it from Foxborough to New Haven. He drove fast but not ridiculously so: he was still way over the alcohol limit, so the last thing he wanted was to get stopped. It was a dollar to a dime that any highway patrolman who did pull him over would let him go on his way once Patrese had explained the situation, but it wasn’t inconceivable that Patrese would run across a trooper who disliked the Bureau (most people did), didn’t see what the hurry was (the folks were dead, right? They weren’t going nowhere), and would take great pleasure in busting his ass for DUI (‘The law’s the law, sir’). Either way, better not to risk it.

Kieseritsky had said she’d hold the crime scene for him once he’d made it clear he was just down the road rather than in New Orleans. Patrese had texted his buddies back in Foxborough to explain his absence, and chuckled to himself at the thought of the ragging he’d endure in absentia once they eventually hauled their sorry asses out of bed. He’d have given an awful lot to be at the stadium this afternoon rather than poking round the entrails of yet more lives snuffed out, but when the dead said jump, anyone who dealt with homicide could only ask one question: ‘How high?’ That was the way it was and always would be. You don’t like it? Get another job.

The crime scene came with the sound-and-light show that all major incidents did: rotating blues and reds on top of patrol cars, men and women in sterile suits and shoe covers talking urgently to each other or into handsets, striped tape flapping in the breeze, and a crowd of onlookers both thrilled and appalled to be part of all this. A uniformed officer was subtly videoing the crowd: some killers like to hang around the crime scene.

Patrese parked up on a side street, opened his door, checked to see no one was looking, shoved a couple of fingers down his throat, and parked what was left of the contents of his stomach into the gutter. He hadn’t vomited at a crime scene for many years, but the way he was feeling right now, he couldn’t guarantee continuing that streak. It would do his image and authority no good if, the moment he saw the corpses, he started yakking his guts up like a teenager who’d had too much Coors. Hence the precautions: get it all out now.

When he was sure his stomach was well and truly empty, he popped some gum in his mouth, got out of the car and strode towards the Green. The Green was the kind of space which would have made the Founding Fathers purr: a large expanse of grass criss-crossed with paths and surrounded – protected – on all sides by buildings which reeked of civic pride. A neoclassical courthouse with columns out front; red-brick office blocks designed in Georgian Revival; and what looked like an enormous Gothic castle gatehouse.

A uniform checked Patrese’s badge and lifted the tape for him to duck under.

‘Detective Kieseritsky’s over there, sir.’ The uniform pointed to a small lady in a charcoal trouser suit. Patrese nodded his thanks and walked towards her.

‘You must be Agent Patrese,’ said Kieseritsky when he was still ten yards from her.

She was mid-thirties, all lines and angles: hair parted at the side and cut short at the back, cheekbones tilting above a pointed chin, arms forming triangles as she splayed her hands on her hips. If there was any warmth in her voice or bearing, Patrese couldn’t detect it: then again, he wouldn’t have been full of the milk of human kindness either if he’d spent the first part of his Sunday at a double homicide.

‘Looked you up while you were on your way,’ she added. ‘You ready?’

‘Sure.’

‘Any preference?’

‘Preference?’

‘Which one you want to see first.’

‘Whichever’s nearer.’

‘John, then.’

‘John?’

‘John Doe. That’s what they still are. John Doe and Jane Doe.’

There were three churches on the east side of the Green, arranged in a neat line: one at the north end, one at the south, and the third smack in between. Kieseritsky headed toward the middle one. Patrese fell into step alongside her.

He gestured all round them. ‘Big place,’ he said, and instantly cursed himself for being so facile.

Kieseritsky shot him a look which suggested she was thinking exactly the same thing, but her tone was polite. ‘Sure is. Designed by the Puritans to hold all those who’d be spared in the Second Coming.’

Patrese tried to remember the Book of Revelation. ‘A hundred forty-four thousand?’

‘You a religious man, Agent Patrese?’

‘Used to be. Not anymore.’

‘Then we’re gonna get along just fine.’

She led the way through a line of trees, and now Patrese could see the headless corpse on the church steps. The man was lying naked on his back, though curiously the pose didn’t look especially undignified, at least to Patrese’s eyes. Perhaps, he thought, it was because the cadaver hardly looked human anymore, not without its head.

‘Snappers have all been and gone,’ Kieseritsky said.

Patrese nodded. She was telling him that the crime scene had already been photographed from every conceivable angle and distance, so he could – within reason – poke around to his heart’s content.

Crisp fall morning or not, dead bodies stink. Patrese gagged slightly when the stench first reached him, but not so obviously that anyone would notice. Just as well he’d gone for the gutter option a few minutes before, he thought.

He crouched down beside the corpse.

No head, no right arm, and the skin gone in a large circle from sternum to waist. Hard to tell too much from any of that about whoever this poor soul had once been, but from the crinkly sagging of fat around the man’s waist, the faint wrinkles on his remaining hand and the gray hairs on the arm above it, Patrese guessed his age as mid-fifties.

No blood, either: no blood anywhere around the body, even though it had suffered two major amputations. John Doe had clearly been killed elsewhere and brought here.

Patrese peered closer at the points where the killer had performed those amputations. Clean cuts, both of them, even though taking off a head and arm involved slicing through tough layers of tissue, muscle, cartilage and bone. Must have used something very sharp, Patrese thought. Must have been skilled at using it, too. A surgeon? A butcher?

The man’s neck looked like an anatomy exhibit: hard white islands of trachea and esophagus surrounded by dark-red seas of jugulars and carotids. The stump of his shoulder was a sandwich in cross-relief: skin round the outside like bread, livid muscle and nerves the filling within. And where the skin on his chest had been was now a matrix of areolar tissue, thousands of tiny patches like spiders’ webs which Patrese could see individually up close but which blended into formless white from even a few feet away.

Patrese looked at the signet ring on the man’s pinkie. Kieseritsky had been right when she’d called it as the Benedictine medal: Patrese had grown up a good Catholic boy, and symbols such as these were now hardwired into his memory. There on the ring was Saint Benedict himself, cross in his right hand and rulebook in his left, and around the picture ran the words Eius in obitu nostro praesentia muniamur.

‘May we be strengthened by his presence in the hour of our death,’ said Kieseritsky.

Patrese nodded, wondering whether John Doe had indeed felt the presence.

‘This isn’t a Benedictine church, though?’ he asked.

Kieseritsky shook her head. ‘United Church of Christ.’

‘And the other two?’

She shook her head again. ‘That one’ – pointing to the church at the north end of the green – ‘is also United Church. The other’s Episcopal.’

Patrese looked over the rest of the corpse. Indentations on the skin of both ankles: restraints, Patrese knew. That apart, nothing: no watch, no jewelry, no tattoos.

There was something next to John Doe’s hand. A playing card, by the look of it.

Kieseritsky handed Patrese a pair of tweezers. He picked the card up.

Not a playing card; well, not one of the standard fifty-two-card deck, at any rate.

The card pictured a man in red priestly robes sitting on a throne. On his head was a triple crown in gold, and in his left hand he carried a long staff topped with a triple cross. His right hand was making the sign of the blessing, with the index and middle fingers pointing up and the other two pointing down. At his feet were two crossed keys, and the back of two monks’ heads could be seen as they knelt before him.

Beneath the picture, in capital letters, THE HIEROPHANT.

Patrese knew exactly what it was. A tarot card.

4 (#ulink_ee371189-4a7f-518b-bb4d-fb5cf654752a)

There was a tarot card by the cadaver of Jane Doe, too. Hers was THE EMPRESS. The figure on this card was also sitting on a throne, though this one was in the middle of a wheat field with a waterfall nearby. She wore a robe patterned with what looked like pomegranates, and a crown of stars on her head. In her right hand she carried a scepter, and beneath her throne was a heart-shaped bolster marked with the symbol of Venus.

Like John Doe, Jane was also naked, and also missing her head, an arm (the left one, this time), and large patches of skin front and back.

The more Patrese looked, though, the more he saw that there were at least as many differences between the two corpses as there were similarities.

For a start, Jane was lying on the grass under a tree, a couple of hundred yards from the church where John had been left.

More pertinently, perhaps, she’d been killed where she lay.

Patrese saw the splatter marks of blood high and thick on the tree trunk: the carotid artery, he thought, spraying hard and fast as her neck was cut. The ground around and beneath her body squelched with all the blood which had run from the cut sites.

And whereas John had been killed with what looked like clinical precision – clean lines of severance at neck and thigh, neat removal of the chest and back skin – Jane had been attacked with a far greater, unfocused fury. The wound at her neck gaped open and jagged, as though the killer had sawn or twisted or yanked her head: possibly all three. Flaps of skin and muscle hung messily from the stump of her arm. The perimeters where the patches of skin had been taken were uneven and torn. No restraint marks on her remaining wrist or her ankles: the attacker must have set about her instantly.

Heads, arms, skin, all gone. Had the killer taken them with him, as proof of his skill and tools to help him relive the fantasy he’d just acted out?

‘Any thoughts?’ Kieseritsky asked.

‘Lots. Some of them might even be right.’ Patrese pushed himself to his feet. ‘John was killed elsewhere and brought here. Jane was killed here. Pretty risky, to decapitate someone in a public place. Lot of people round here at night?’

‘Up to midnight, sure. Most of ’em the kind of people who keep you and me in business, of course. Same for urban parks the country over. But we ain’t talkin’ murderers usually, let alone something like this. We’re talking pickpockets, drug dealers, muggers, those kind of guys. The guys who know the process system as well as I do, they come in and out of the station house so often.’

‘New Haven’s got a high murder rate, right?’

‘Where d’you hear that?’

‘Bureau report. I remember it ’cos after Katrina, when all the criminals had been shipped out of state during reconstruction, New Orleans dropped out of the top three for the first time in years. Big rejoicing in the Big Easy.’

‘Yeah, well. I seen that report too. We’re fourth highest in the US proportionate to population, it says. Only ones in front of us are Detroit, St Louis and some other hellhole, can’t remember where. But it’s bullshit, Agent Patrese.’

‘Yes?’

‘First off, our crime figures are down year-on-year, and that’s what matters to me, not how we rank against someplace else. Second, it all depends on where you draw the municipal boundaries. May I speak freely? New Haven ain’t no different to any other damn place in the States. The vast majority of crime is committed by poor black people, on poor black people, in areas full of poor black people. Don’t make it right, of course, but that’s the way it is. You must know that.’

Patrese nodded. He’d worked in Pittsburgh and New Orleans, and it was the same in both those places. Kieseritsky continued:

‘But round here, downtown, this kind of thing just doesn’t happen.’ She gestured toward the Gothic gatehouse on the edge of the Green. ‘That’s the main entrance to Yale, you know. That’s the kind of place this is. Ivy League, old school, full of the kids who in twenty years’ time will be running the country.’

‘And screwing it up, same as generations before them have done.’

She raised a sardonic eyebrow. ‘President Bush went to Yale.’

‘I rest my case.’

She laughed. ‘Anyway. Like I said, most law-abiding folks wouldn’t hang around on the Green late night, but those that do are only going to lose their wallets and cellphones. Not their lives.’

‘And the lowlife? They here all night?’

She shook her head. ‘Most of them have cleared out by two or three in the morning, even on weekends.’

‘And no one saw Jane Doe being killed, or John Doe being dumped?’

‘Not that we’ve found so far.’

A uniform hurried across the grass toward them, eyes bright with the importance of the news bearer.

‘We’ve got a match on Jane’s fingerprints, ma’am,’ he said.

‘Previous offense?’

‘Arrested in New York on the Iraq war demonstration, February 2003.’

Patrese remembered that day well: there’d been protests all over the world. He’d intended going, but he’d spent what had started as the night before and ended up as the whole weekend with a waitress he’d met on the Strip in Pittsburgh.

‘Regina King,’ the uniform continued.

He must have seen both Patrese’s and Kieseritsky’s eyes widen in surprise, because he nodded. ‘Yes, ma’am. Sir. That Regina King. Kwasi King’s mom.’

5 (#ulink_6609a2fe-553b-5565-9d4d-6a9429e99abf)

Kwasi King was twenty-four years old, and he had been famous for exactly half his life. A month after his twelfth birthday, he became the youngest chess grandmaster in history. Before he reached fourteen, he won the US championship. Chess was pretty much a minority sport as far as the mainstream media were concerned, but one story was always guaranteed to get their attention – a child prodigy who might, just might, be the next Bobby Fischer.

Especially when that prodigy was a black kid raised by a single mom in America’s largest public housing project.

Regina King had been seventeen when she’d given birth to Kwasi. The name meant ‘born on a Sunday’, because he had been. If she knew who Kwasi’s father was, she never said so. She had no qualifications to speak of, but what she did have was a work ethic that was positively Stakhanovite and a tidal desire to give her son a better start than she’d had.

She took two jobs at once, sometimes three, just to keep them afloat; but the jobs were minimum wage and childcare cost money, so the only place she could afford was a small apartment high up in a Queensbridge tower block. Six thousand people lived in the Queensbridge complex, peering with hopeless longing across the water to Manhattan’s glass-and- steel canyons.

Drug dealers worked shifts along the development’s main commercial stretch, punching clocks as diligently as stevedores. You wanted to go get something from the store, even a loaf of bread or a bar of candy, you had to walk past them. This is the life, their very presence seemed to hiss, this is thelife, this is the only life you’ll ever know. In the daytime, they shouted and snarled at each other: when night fell, they started shooting.

Some of them tried their luck with Regina: she was a good-looking girl, and still only twenty. She turned them down, politely but firmly. A couple of her wannabe suitors weren’t used to women turning them down, and liked to use their fists on such occasions: but there was something about Regina which made them meekly accept it and walk away.

One day, shortly before Kwasi’s fourth birthday, Regina took him into Manhattan for the day. They walked through Washington Square Park, past the corner of the world which is forever chess: an array of checkered tables in poured concrete, and round them an endless flow of players and spectators. All human life is here: alcoholic hustlers who’ll bet you a handful of dollars a game, Eastern European grandmasters down on their luck, bankers and lawyers in their lunch hours, students, bums, sages, fools. And the play is strictly speed chess. No two-hour games in reverential library-style silence: five minutes each player, tops, with trash-talking not so much encouraged as mandatory.

Kwasi stood to watch one of the games, his little face barely at table level, so he was peering through the pieces rather than over them as adult players do. The game had ended in a flurry of moves and insults, both players’ laughter deflecting any malice. Come on, Regina said, game’s over, let’s go.

One more, Mom. Can I watch one more?

She’d been at work all week, farming Kwasi out to friends. She owed him a little indulgence, no? Sure, honey, one more. Just one more.

One more became one more after that, and another one, and another one. Nine games later, when a hotshot lawyer had been checkmated seven ways to Sunday by one of the regular park hustlers and grudgingly handed over the five bucks stake, Kwasi turned to him and said, quietly but precisely: ‘You missed checkmate in three moves.’

Regina, swaying from foot to foot in her impatience to get going, stopped dead.

She knew two things for sure. First, Kwasi had never so much as seen a chess set in his life, let alone played with one. Second, he wasn’t the kind of kid to come out with something like this unless he meant it. She’d always known he was bright: talking at six months, reading at a year, glued to The Price Is Right at eighteen months – but this, if this was what she thought it was … well, this was something else entirely.

Lawyer and hustler both laughed: the hustler with some good humor, the lawyer with none. The hustler, breath sweet from his paper-bag rum, leaned toward Kwasi. ‘Mate in three, huh?’

Kwasi said nothing: simply put the pieces back to where they’d been halfway through the game, and played through the three-move sequence. When he finished, the lawyer took the pieces from him and played it through himself, muttering ‘I’ll be damned, I’ll be damned’ with every slap of piece on board.

‘I done seen all that at the time,’ the hustler said. Kwasi merely looked at him, his face completely still like a little black Buddha, until the hustler’s mouth cracked into a goofy raggedy-tooth smile and he threw up his hands in mock surrender. ‘OK, kid, OK, you got me. I never saw that neither, none of that. How old are you?’

‘Three years, eleven months and twenty-six days.’

‘A’iiiight. It’s good to be precise. And when you learn to play chess?’

‘Thirty-eight minutes ago.’

The hustler laughed again, until he saw that Kwasi was serious.

When it came to chess, Serious was Kwasi’s middle name. This is my boy, Regina would proclaim, and he’s not taking no crap off of nobody. Not in the years he spent playing all comers in the park, and certainly not when some of them tried to cheat by making illegal moves or subtly nudging a piece off its square; not when people tried to trash-talk him, because the regulars understood that Kwasi didn’t trash-talk and that, get this, it didn’t matter, ’cos he was so damn good; not in the proper tournaments he played, the ones that had TV crews and arbiters and trophies; not at school when the other kids swung between admiring his talent and calling him a freak; not when the cops came round after yet another gang murder to ask whether he’d seen anything from his apartment window six stories up; not when as a teenager he threw away his polo shirts and acrylic sweaters, started wearing long black leather coats and motorbike boots, and ran his hair into dreadlocks; not even when he went on Letterman or Conan or Leno or any of those shows. He didn’t give a shit about what folks did or said to unsettle him, he didn’t take any shit off of them. He wasn’t in the shit business.

And all the time around him, the endless whispering undercurrent of hope and fear: the next Fischer, the next Fischer, the next Fischer, for Fischer had been both genius and lunatic, the two sides of him waxing and waning against each other until the lunatic had taken over, ringing radio stations after 9/11 to exult in the destruction of the Twin Towers and tell the world that America had had it coming for years.

Wherever Kwasi was, so too would Regina be. To give him more time to play chess, now his tournament winnings were enough to let her go part-time at work, she pulled him out of school and began to home-tutor him herself. The deal was simple: he played chess, she did everything else. She dealt with anything that might stress or distract him even before he knew it existed.

Kwasi had a growth spurt around thirteen or fourteen, and after that people who didn’t know them sometimes thought that he and Regina were brother and sister, or even boyfriend and girlfriend, as she still looked so young. When he went to college – none of the Ivy Leagues would take him, but the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, offered him a chess scholarship and a major in computer science, and he led the varsity chess team to three consecutive Pan-American Championships – she came with him, setting the two of them up in an apartment near campus.

In America of all places, there’s fame and there’s fame; and there was no doubt as to the moment when Kwasi made the jump from one to the other. Three years ago, at the age of twenty-one, he played for the world championship in Kazan, the ancient Tatar capital which was now part of modern-day Russia, a night’s train ride east of Moscow. His opponent was Rainer Tartu, a thirty-something Estonian (long after the fall of communism, the old Soviet republics still dominated the chess world) with wire-rimmed spectacles, a bouffant of sandy hair, an expression of benevolent openness, the fluent English of the international cosmopolitan, and the long slim fingers of a concert pianist, which was what he was when he wasn’t playing chess.

The match was twelve games, with a tie-break procedure if the scores were still level at the end. A dozen US reporters and analysts went out to Kazan to cover the match: the networks carried highlights, and there was full, real-time, coverage over the Internet.

To start with, it all seemed for nothing. Kwasi, this great natural talent, this badass who’d steamrollered all the other candidates to get here, who wore a suit at the board because those were the rules but who wouldn’t cut his hair – indeed, he’d woven red, white and blue ends into his dreads – Kwasi was off the pace.

Tartu won the first game at a canter, played out draws for the second and third, won the fourth and had the better of draws in the fifth and sixth. A succession of draws can appear boring, but these were anything but. They were see-saw games where the initiative swung first one way and then the other, where pressure led to mistakes and mistakes led to pressure. Each player had to dig deep within themselves to hold the line, slugging each other to a battered and exhausted standstill, knowing that it was just as important not to let your opponent draw blood as it was to try to hurt him: because sometimes when the blood starts to flow, it’s hard to staunch.

With one point for a win, half for a draw and none for a loss, Tartu was 4–2 up at halfway. Kwasi looked shell-shocked, and all Regina’s soothing could do nothing to stop the rot. Kwasi was letting it slide through his fingers, little by little. The reporters wanted to go home.

Game seven was another draw, though for the first time in the match Kwasi was the better player. But draws weren’t going to be enough: he had to win two games of the remaining five even to force a tie-break.

In game eight, he finally, triumphantly, magnificently got it right, playing a game of such breathtaking brilliance that when Tartu resigned, he – Tartu – led the audience in a standing ovation. Kwasi peered through his dreads in shy appreciation.

Now it was Tartu’s turn to look shell-shocked. He lost game nine inside twenty moves, almost unheard of at this level. Four and a half points each, but the momentum was all with Kwasi. The reporters were getting their front pages again. Game ten, Kwasi missed a difficult winning chance and had to settle for a draw.

Then came game eleven. In a routine opening, Kwasi made a knight move that brought gasps from the spectators in the hall. Even a casual player could see it was a blunder. Tartu, blinking in astonishment, looked at the position, then at Kwasi, then at the arbiter, then back at Kwasi, then back at the position. There was no trap, no swindle. A genuine, twenty-four-carat mistake, or so it seemed. Five moves later, Kwasi resigned.

In the press conference afterwards, Kwasi explained what had happened. He’d reached out to move the knight, and as he’d done so, he’d realized it would be a mistake: but before he’d been able to withdraw his hand, he’d felt the tips of his fingers brush the head of the knight. Chess rules state that if you touch a piece, you have to move it. He’d touched the knight, so he’d had to move it.

Sitting next to Kwasi, in front of the world’s press, Tartu shook his head in astonishment. I didn’t see you touch it, he said. The arbiter concurred: Me neither. Kwasi could have chosen a different move, a better move, and no one would have been any the wiser. How did he feel about that?

He shrugged. At the chessboard, he said, rules are rules. Nobody’s fault but mine.

And now he needed to win the last game just to take the match into a tie-break. Tartu could try to close things down, go for the easy draw. Kwasi would have to shake things up: go for the victory even at the risk of losing.

Mikhail Tal, a former world champion and the most dashing player the modern game has seen, once said: ‘You must take your opponent into a deep dark forest where two plus two equals five, and where the path leading out is only wide enough for one.’

In game twelve, that’s exactly what Kwasi did. He piled complication on complication, trying to scramble Tartu’s powers of concentration and calculation. Feint left and go right: feint right and go left. Knights jumping around at close quarters, rooks battering down open lines. In between moves, Kwasi got up and walked around, pawing at the ground like a bull.

A well-aimed, well-timed counterpunch from Tartu would probably have taken the game back to Kwasi, but Tartu was – as Kwasi had hoped – too conservative, too wedded to the idea that he could ride out the storm if he battened down the hatches. Kwasi sacrificed two pieces and then a third to rip open Tartu’s defenses; and when Tartu finally extended a hand in resignation, he looked almost relieved that the agony was over.

Tie-break: first ever in a world championship.

The twelve games so far had been played with classical time controls: each player given two hours to make forty moves. Now there would be four games at 25/10: twenty-five minutes for all moves, with ten seconds added to each player’s clock every time he made a move. Kwasi won the first game and Tartu the second. The third and fourth were both draws. Still level.

The ratchet got even tighter, and up went the excitement. Two games at 5/3: five minutes for all moves, three seconds added per move. If the scores were still level after these two games, another set of two would be played, and another, up to five: ten possible games in all. NBC cleared its schedule and started beaming the matches live. Viewing figures later released would show that, on average, quarter of a million more people started watching every minute as news of the showdown spread across America.

Kwasi won the first game. He was five minutes from the world title, all he needed was a draw – and he blew it, letting Tartu’s pieces strangle the life out of his position. Third and fourth games, both draws. Fifth game, Tartu won, and now he had the advantage. That meant shit or bust for Kwasi: win or go home.

He crouched low on his seat like a panther, wild and beautiful. When he reached across the board, it seemed that he was not so much shuffling wooden figures from one square to another as unleashing some long-hidden primal force. The cameras zoomed in on his face. He winced in agony, gasped in delight. He put his head in his hands. When he bared his teeth, a couple of the spectators in the front row recoiled instinctively.

This wasn’t just chess anymore, the commentators panted breathlessly: this was heavyweight boxing, this was a five-set Wimbledon final, this was Ali and Frazier, Borg and McEnroe, where the momentum swings first one way and then the other, and both men can practically smell the prize they want so much.

Frantic scramble with seconds left for both men in game six, but it was the flag on Tartu’s clock that dropped first. He’d lost on time. They were even again. The crowd stamped and cheered, not because they were against Tartu but because they recognized that what they were seeing was a once-in-a-lifetime drama.

Seventh game to Kwasi. Eighth to Tartu, at last beginning to sweat under the tension. Punch-drunk, perhaps trying to save themselves for what they knew really would be the final decider, they played out the final two games as draws.

Now came sudden death, Armageddon chess: and for once the sobriquet didn’t seem inappropriate. The colors had so far alternated game on game, but since this was a one-off, they tossed again. Kwasi won, and chose Black. In Armageddon chess, White has five minutes to make all his moves and Black only four: but White has to win, because a draw is counted as a Black victory.

By now, thirty-two million people were watching in the United States alone, and three or four times that worldwide.

Tartu and Kwasi shook hands, gave brittle smiles for the cameras. The arbiter checked their clocks, and off they went.

Most all the chess teachers Kwasi had ever had – and every one of them had been obliged to provide their services for free, as Regina had never been able to afford lessons – had tried to stop him playing speed chess in Washington Square Park. It’s not real chess, they’d tell him; it’s cheap stuff, trickery, simple two- or three-move patterns. Real chess takes time and contemplation, real chess requires vision and strategy. Real chess is the Four Seasons: speed chess is Mickey D’s.

But they’d all been wrong, because it was exactly those thousands of two- and three-minute games in the park that won Kwasi the world title now. All the things that were gradually leaching Tartu’s energy from him – the ever-tightening vice of quicker time controls, the barely controlled pandemonium in the hall, the insane pressure of playing a blitz game for the greatest prize in his sport – these were the very things that energized Kwasi, that arced through him like electricity. Four minutes on his clock, spectators who couldn’t keep still or shut up, all eyes on him. This wasn’t a hall in Kazan, this was the park, rain and shine and summer and winter, this was where he felt at home.

Now, with no time in which to think and even less in which to move, Kwasi played with deathless precision, mind and eyes and fingers everywhere on the board at once. He made moves like a tennis player plays shots, all instinct and muscle memory, pieces finding their way to the perfect square time after time as though by homing instinct. Some called it the zone, some called it a trance. It was both, and neither. Kwasi was no longer playing chess. He was chess.

And when he came back to the States as world champion, the youngest in history and America’s first since Fischer, he remained chess in a different but equally all-consuming way. Suddenly, the game was no longer a refuge for weirdos and sad sacks, for guys with pocket protectors and BO, sweating out fast-food toxins in gloomy rooms.

Kwasi, single-handedly, had made chess cool.

He played against celebrities. He guested on hip-hop albums, rapping about the ways in which chess mirrored life. He said he was going to hire himself the best architect available and build himself a house shaped like a rook, replete with spiral staircases and parapets. Sponsors fell over themselves to sign him up, this perfect synthesis of every marketing man’s dream: hip enough to appeal to kids, smart enough to appeal to adults, wholesome enough – never much talk of girls, let alone drugs – to be held up as a model for the black community. Kwasi had Tiger’s reach, Jordan’s smarts, 50 Cent’s cred, Denzel’s looks. Will Smith wanted to play him in a movie.

The one thing he didn’t do was the one thing that had made him famous. He didn’t play competitive chess. As world champion, he was guaranteed the right to defend his title, so he didn’t have to go through the official qualification process again, but there were still plenty of other tournaments in which he could have played, names that tripped off the tongue of chess fans the world over: Linares, Wijk aan Zee, Dortmund.

The less he played, the more his mystique grew, this Gatsby of modern-day chess. Was he working on some new fiendish openings? Could anyone else call themselves a winner without playing him?

It wasn’t as though Kwasi needed the tournament income. The championship prize money had made Kwasi a millionaire literally overnight. In the year or two that followed, endorsements multiplied that at least tenfold, probably more. The only two people who knew the exact figures were Kwasi and Regina, and they weren’t telling. And yes, she was still there, always at his side. No one got to say so much as a single word to him without going through her first. No sponsor got to pitch him a proposal until she’d read it and sat in their boardroom for three hours going over it point by point.

When he bought a condo in the Village, she moved in with him. When he played in exhibition matches, she was right there in the auditorium, front and center. When they stayed in hotels, they had a suite, two bedrooms, one for him and one for her. At home or on the road, she made sure his cooking and laundry were done. She was mother, manager, promoter, gatekeeper.

Time ran a profile on her. YOU KNOW THE KING, ran the headline, NOW MEET THE QUEEN. She cut it out and put it on the noticeboard in their kitchen, alongside one that showed her on the street outside their old tower block, a farewell to their old life. THE QUEEN OF QUEENS, that one said.

And now Kwasi was due to begin the defense of his title – against Tartu once more – at Madison Square Garden in less than two weeks’ time, and Regina was dead.

6 (#ulink_b68138c9-5d45-5662-aeac-b373d38e6c6e)

New York, NY

‘I don’t understand,’ Kwasi said. ‘She’s never late.’

Marat Nursultan tapped his Breitling. ‘We get on with it? We suppose to start a half-hour ago.’

‘Of course,’ said Rainer Tartu.

It was only the three of them in the room: the three most powerful men in world chess. Not that it was an equal triumvirate, of course. Kwasi was the box office: his presence, and his presence alone, determined the dollars. Tartu just happened to be the one on the other side of the board. If Kwasi could have somehow played against himself, the sponsors wouldn’t have given Tartu a look-in; and if he, Tartu, didn’t like it, there were plenty of other grandmasters who’d take his place in a heartbeat.

As for Nursultan … well, he was the kind of guy that everyone had an opinion about. He liked people to call him Mr President, as he held two such offices: the presidency of Tatarstan, the semi-autonomous region of Russia whose capital Kazan had hosted the first match between Kwasi and Tartu; and the presidency of FIDE, the Fédération Internationale des Échecs, the governing body of world chess.

Rumors of bribery and corruption had swirled around both elections, and Nursultan had done little to dampen them: how else, his sly smile and calculated bonhomie seemed to ask, how else was one supposed to win elections? Nursultan was pretty much the prototype for homo post-sovieticus: after completing a doctorate in applied mathematics from Kazan State Technical University, he’d seen which way the winds of perestroika were blowing in the late 1980s and had positioned himself accordingly.

In the chaos that had followed the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, he’d made a small fortune in car dealerships, a medium one in oil and banking, and an enormous one in technology. The Kazan Group, of which he was chairman and CEO, was now at the forefront of mobile communications and software development. On a good day he was worth $12 billion, on a bad day $10 billion. He was comfortably one of the richest hundred people in the world. He had mistresses whom he paraded in public and a wife whom he didn’t. He claimed to have been abducted by aliens and given a tour of their galaxy.

And he loved chess with a passion. His Rolls-Royces were only ever black or white, the floors of all the houses he owned around the world were checkerboard marble, and he’d made the game a compulsory subject at every school in Tatarstan. He spent as much time out of Tatarstan as he did in it, leaving the day-to-day running of the place to the prime minister, who happened to be his brother. As far as Nursultan was concerned, both Tatarstan and FIDE were his own private fiefdoms. He liked to answer to one person only: himself.

Now he sat in his suite – the presidential suite, naturally – at the Waldorf-Astoria, graying hair slicked back above his brown, watchful, flat Asiatic face. ‘Kwasi, we not wait any longer. Your mother not here, that too bad.’ He put out his hand. ‘You have demands, no? You give them to me.’

Kwasi handed a sheaf of papers to Nursultan and another one to Tartu. ‘They’re both the same,’ he said.

Nursultan flicked to the last page. ‘Sixteen pages.’ He looked up, eyes glittering with the prospect of challenge. ‘One hundred and eighty demands!’

‘We’ve divided them into sections. Prize money, playing environment, and so on.’

‘This is a laundry list,’ Tartu said.

‘And they’re not demands,’ Kwasi added. ‘They’re conditions. I’m entitled to have match conditions which suit me.’

‘And me?’ Tartu added. ‘Am I entitled to conditions which suit me?’

Kwasi shrugged.

‘If we not accept these, er, points,’ Nursultan said carefully, ‘then what?’

‘Then I don’t play.’

‘They are demands, then.’

Kwasi shrugged again.

‘The match starts in two weeks’ time.’

A third shrug. ‘I know.’

Nursultan looked at Tartu and raised his eyebrows.

They started to read Kwasi’s list. Nursultan jotted notes in margins, pursing his lips and giving little dismissive laughs from time to time. Tartu read the whole thing very fast, and then went back to the start and did it again, more slowly. Kwasi walked over to the window and looked down at Park Avenue, as though he could will his mother into arriving simply by the power of his gaze.

‘Well,’ Nursultan said at last, ‘Rainer and me, we should talk about this, no?’

‘OK,’ Kwasi said.

He didn’t move. Nursultan laughed. ‘We want to, how you say? Talk about you behind your back.’

‘Oh. OK. Sure.’

‘You go into room next door,’ Nursultan said. ‘I call you when we finish.’

Kwasi left. Nursultan batted the back of his hand against Kwasi’s list. ‘This: outrageous. You know how much money on this all? He want to hold us ransom.’

‘He’s not trying to hold you to ransom.’

Nursultan snorted: hard-headed businessman telling airy-fairy chess player the ways of the world. ‘Two weeks before biggest chess match since Reykjavik? What else he do? Rainer, they not coming to see you. Sorry, but true. They come to see him.’

‘You don’t get him, do you?’

‘Get him?’

‘Understand him.’

‘Sure I do.’

‘No, you don’t. Why does he make all these demands?’

‘To get more money. To, how you say, unsettle you.’

‘No. He makes them because they’re what he wants. He has no agenda beyond that. He’s a child. He doesn’t want to play in Linares, so he doesn’t. He doesn’t want to play in Dortmund, so he doesn’t. He sees the world like a child. Black and white.’

‘He not behave this way last time.’

‘He wasn’t world champion last time. He wanted that prize so much, he didn’t care about anything else. But now he wants everything to be the way he wants it.’

Nursultan flicked through the pages. ‘Some of these, reasonable. Some, no. I see ten, twelve, simply no good. Cannot accept.’

‘Then we won’t play.’

‘You will play.’

‘I’ll play. But he won’t.’

‘Then I negotiate with him.’

Tartu’s smile meant the same thing as the snort Nursultan had given a minute or so before: I know the truth of this situation better than you. ‘He won’t negotiate.’

‘Everyone negotiates.’

‘Not him. These aren’t one hundred and eighty demands: they’re one demand. Take it or leave it.’

‘We’ll see.’ Nursultan called out. ‘Kwasi!’

Two doors opened at once: the one that led into the room where Kwasi was waiting, and the main door of the suite, which was guarded round the clock by Nursultan’s security men. Two of them stood in the doorway. As Kwasi came back in, one of the security men walked over to Nursultan and spoke quickly in Tatar. Nursultan nodded. The man by the door stepped aside, and Patrese walked in. Nursultan remained seated. People like him didn’t get up for government agents.

‘I’m looking for Kwasi King,’ Patrese said.

‘That’s me,’ Kwasi said.

‘Franco Patrese, Federal Bureau of Investigation.’

‘Have I done something wrong?’

Patrese looked around the suite. ‘Could I talk to you in private, sir?’

7 (#ulink_0b82e581-a5b6-5455-981c-be3abe298371)

Patrese led Kwasi back into the room from where he, Kwasi, had just come, and shut the door behind them. Deep red sofas, antique escritoires, carpets thicker than some of the surfaces he’d played football on, and a wicker chair that JFK had used for his bad back: Patrese figured that, on a Bureau salary, he too could afford to stay in this place. For about five minutes.

He’d volunteered to tell Kwasi. In terms of gathering evidence and following leads, the first twenty-four hours after a homicide was critical, and so it made sense for Kieseritsky to stay in New Haven and supervise the investigation there: it was her turf, and she knew it backwards. The easiest thing to do would have been to phone the nearest precinct to Kwasi’s apartment and get them to send a couple of uniforms over, and perhaps that’s what they would have done had Jane Doe turned out to be an ordinary Jane, but this: this was something else.

The news was going to get out sooner rather than later, and the moment it did the press would be all over them like the cheapest suit on the rack. In that situation, you didn’t need some guy barely out of police academy, so Patrese had hauled ass from New Haven down to New York, a couple of hours’ drive to add to what he’d already done. En route, he’d checked in with his boss at the Bureau’s New Orleans field office, Don Donner – yes, that really was his name and yes, he had eventually forgiven his parents. Donner was one of the least territorial Bureau guys around, which made him a rare and precious beast. Sure, he’d said, do whatever you have to, help them for as long as they need you. We’re all the Bureau: we’re all the good guys.

And Patrese’s hangover had disappeared somewhere around Stamford.

Death notification is the redheaded stepchild of law enforcement work, the dirty job that no one really wants to do; but one of Patrese’s partners, an old-time Pittsburgh detective named Mark Beradino, had always believed it to be one of the most important tasks a police officer could have. It wasn’t merely that you owed the living your best efforts to find whoever had killed their loved one; it was also that the skilled detective could ascertain a whole heap from what the bereaved said or did. Shock and grief, like lust and rage, flay the truth from people.

Patrese knew the rules of death notification. Talk directly. Don’t be afraid of the d-words – dead, died, death. Don’t use euphemisms. Driver’s licenses expired, parcels were passed on, keys were lost. Not people. People died.

Patrese gestured for Kwasi to take a seat, and sat down opposite him.

‘Mr King, your mother is dead.’

Kwasi stared at him. Patrese held his gaze, rock-solid neutral. He didn’t try to take Kwasi’s arm or touch him in any way. Everyone reacts to news like this differently. Some people clap their hands to their chest and catch their breath; some fall sobbing to the floor; some even attack the messenger.

Kwasi did none of these things. He stared at Patrese for fully half a minute, totally blank, as though his brain – this vast, amazing brain that could see fifteen moves ahead through a forest of pieces on a chessboard – was struggling to comprehend the very short, very simple, very brutal sentence he’d just heard.

‘You sure?’ he said at last.

‘Yes, sir.’

‘How?’ He blinked twice. ‘How? Where? When?’

‘Her body was found this morning on New Haven Green.’

‘Where?’

‘New Haven, sir. Connecticut.’

‘What the hell she doing there?’

‘I was hoping you could tell me that, sir.’

Kwasi looked around, as though seeing the room for the first time. ‘Can you take me home, officer?’

‘Sure.’

Manhattan slid past the windows of Patrese’s car. A church on Lexington spat worshippers out on to the sidewalk. In a Union Square café, a man jabbed his fork in the air to make a point amidst pealing laughter from his friends.

The journey passed in silence. Kwasi said nothing, and Patrese didn’t try to make him talk. Some people gush an endless torrent of questions, wanting to know everything about how their loved one has died: others are silent, perhaps in the hope that if they don’t ask, don’t know, don’t listen, then it won’t have happened.

Kwasi didn’t move the entire journey. He sat bolt upright and stared straight ahead. Only once, when they turned past Washington Square Park, did he so much as glance out of the window.

Kwasi’s apartment was on Bleecker Street. Patrese pulled up outside. A little further on, at the junction with Sixth Avenue, police barriers were being erected on the sidewalk.

‘Do you have anyone you can call?’

Kwasi shook his head.

‘No one at all?’

‘No.’ Kwasi made no move to get out of the car.

‘Would you like me to come up with you?’

‘Yes. Thank you.’ Kwasi looked at Patrese for the first time since leaving the Waldorf-Astoria. ‘That would be’ – he searched for the right word – ‘helpful.’

There was a doorman in the lobby; a young guy with tight curly hair and teeth white enough to be visible from space. He got to his feet as they came in.

‘Hey, Mr King. Looking forward to the parade tonight?’

Kwasi didn’t hear; or if he did, he didn’t acknowledge it. Patrese nodded at the man. ‘Parade?’ he asked.

‘Hallowe’en parade. Expecting a million folks, they say.’

The apartment was typical Bleecker: gentrification writ large over smatterings of old-school authenticity. Exposed brickwork and windows framed with industrial steel: wooden floorboards and subtle uplighting. Poliform kitchen with corian countertops and Miele appliances: pre-wired Bose sound system and fifty-inch plasma TV.

And on pretty much every surface was a chess set. There must have been hundreds, jostling on shelves and squatting on tables. Standard sets were very much the minority. Think of a theme, and it was there somewhere. Cowboys faced off against Indians, Crusaders against Saracens, Red Sox against Yankees, Spartans against Athenians, angels against demons. There were Egyptian gods, Norse gods, Greek gods. Terracotta warriors peered sideways towards Harry Potter characters. Star Wars figurines backed on to samurai. One set was made of automobile parts; another had skeleton keys as pieces, fitting into a hole in each square; a third had squares of all different heights. Blue pieces eyeballed green ones, pink played yellow, red played orange. A hexagonal board was designed for three players; a multi-dimensional set stacked four boards atop each other.

Kwasi looked at Patrese, saw his interest.

‘Can never have too many sets,’ he said.

This was Kwasi’s refuge, Patrese sensed. When the world got too big and complex and nasty – and it must have been all those things right now for him, and more – here’s where he came, back to the chessboard, where everything had order and rules and where he was the master.

‘Which one’s your favorite?’

‘Don’t have one. If I did, the others would get upset.’

‘The others? The other sets? The pieces?’

‘That’s right. Tell you one I haven’t got, though. It’s this one from Wales; you know, part of England. The chessboard of Gwenddoleu. The board’s made of gold, the men are made of silver, and when the pieces are set up, they play by themselves.’

‘That’s a nice story.’

‘It’s not a story. It’s true. It really exists.’

Patrese decided to change tack. ‘Mr King, I’m sorry to do this, but I have to ask you some questions about your mother. Help us find the person who killed her.’

‘She was killed?’

‘I told you that.’

‘You told me her body was found on New Haven Green.’

‘Well, I’m sorry, but yes. She was killed.’

‘How?’

Patrese had thought about this one already. ‘A knife was used.’ Not a lie. Not the whole truth either, of course, but not a lie. ‘Now, you said you don’t know why she might have been there. In New Haven.’

‘I didn’t say that.’

‘You did, sir.’

‘I said, “What the hell she doing there?”’

‘I took that as you not knowing why she was there.’

‘I don’t.’

Patrese wondered briefly whether Kwasi was being deliberately obstructive. No, he thought, I’ve just told the man that his mother’s dead. Cut him some slack.

‘When did you last see her?’

‘Yesterday.’

‘You remember what time?’

‘A quarter of ten exactly.’

‘That’s very precise.’

‘I know the time of everything that happens.’

‘What was she doing?’

‘Leaving for Baltimore.’

‘What was she planning to do when she got there?’

‘She was attending a symposium run by the National Council of Black Women.’

‘You know where this symposium was?’

‘The Hyatt Regency in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor: 300 Light Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21202. Phone number 410-528-1234.’

Hell, Patrese thought, was this what you needed to be world chess champion? Rain Man with dreads?

‘How did she get there?’

‘By train. Amtrak. Depart Penn Station, New York, yesterday at 10 a.m., arrive Penn Station, Baltimore 12.13 p.m. Return journey, depart Baltimore 9.34 a.m., arrive New York 11.52 a.m.’

Patrese did a quick calculation. ‘You last saw her at quarter of ten when she had to get a train at ten?’

‘I drove her to Penn Station.’

‘And dropped her outside?’

‘There was nowhere to park.’

‘And then you came back here?’

‘Yes.’

‘So you didn’t see her get on the train?’

‘No. I saw her go into the station.’

‘And what did you do after that?’

‘I came back here.’

‘You were here all weekend?’

‘Yes.’

‘What were you doing?’

‘Playing chess.’

‘With who?’

‘Myself.’

‘You play against yourself?’

‘Sure. Against computer programs, and against myself. I have a world title match in two weeks. I’m preparing. Practicing. Training.’

‘What does that involve?’

‘Some general stuff. Get a position, turn it round, see how best to play against it. Also preparing specific openings, a lot of the time. Opening lines are constantly getting developed and refined. You try ’em out, see what works for you. You find a variation you don’t like, you move on to another one.’

Checking through different lines, trying to look at positions from your opponent’s point of view: chess sounded a lot like detective work to Patrese.

‘Did you go to Penn to pick her up today?’

‘Yes?’

‘Were you concerned when she didn’t turn up?’

‘Yes.’

‘What did you do?’

‘I rang her cellphone. She didn’t answer.’

‘You think of doing anything else?’

‘Like what?’

‘Like ring the hotel in Baltimore?’

‘I had to meet with Nursultan and Tartu. She knew where I was going. I figured she’d gotten the wrong train and had no cellphone reception. I guessed she’d come right along to the Waldorf when she arrived.’

‘So your car’s still at the Waldorf?’

‘Yes.’

‘And you have no idea why your mother would have been in New Haven?’

‘No.’

‘No friends, family there?’

‘No.’

‘She lived here, that’s correct?’

‘Yes.’

‘May I see her room?’

‘Sure.’

It was clear from even a first glance that Regina had been a neat freak. Her bed was made to a standard that wouldn’t have disgraced the Waldorf-Astoria, the bottles and tubs on her dressing table were arranged with millimetric precision, and the clothes in her closet were color-coded. In the en-suite bathroom, the same level of order.

‘How many bedrooms are there here?’

‘Two.’

Patrese looked round the room again: high ceilings, south-facing, plenty of light. ‘If this is anything to go by, the master bedroom must be quite something.’

‘This is the master bedroom.’

Patrese looked surprised. ‘Where do you sleep?’

‘Next door.’

Kwasi’s room was smaller. His bed, a single, was jammed hard up against the far corner, the better to make room for as many bookshelves as possible. Chess books, Patrese saw, with titles that might as well have been double Dutch as far as he was concerned. An Anti-Sicilian Repertoire for White. Caro-Kann: Bronstein-Larsen. The Strategic Nimzo-Indian: A Complete Guide to the Rubinstein Variation.

‘Your mom had the master bedroom?’

‘Sure.’

‘Why, may I ask?’

‘Why not?’

Patrese was getting used to the rhythm of Kwasi’s speech and thought patterns now. Kwasi might be a genius on the chessboard, but quotidian details that seemed obvious to Patrese clearly passed Kwasi by.

‘Mr King, your success, your skill, your money bought this place. Most all homeowners I know, it’s the same thing: whoever buys the house gets the nicest room.’

Kwasi shrugged. ‘Don’t bother me. Bedroom’s just a place to sleep.’

Most twenty-four-year-old men thought bedrooms were a place to do pretty much anything and everything other than sleep, Patrese thought: but then again, most twenty-four-year-old men didn’t buy a Bleecker penthouse and then ask their mom to move in with them.

Patrese excused himself and went out on to the apartment’s private roof terrace. He had to talk to Kieseritsky, and thought it best to discuss gory details of beheading and amputation in private.

The terrace had wrought-iron railings set six inches too low for comfort. A few blocks to the south, floats and giant puppets were already beginning to gather in preparation for the parade. Patrese looked out over the river toward Hoboken.

As he dialed, Patrese could hear a low noise from inside the apartment. He wasn’t sure, but it sounded as though Kwasi was crying.

8 (#ulink_f91e827d-727f-590b-8a29-54f78030fff6)

In the first few hours of any major homicide investigation, no news is most certainly not good news. Forensic evidence is fresh, eyewitnesses can remember what they’ve seen, people are willing to offer information. If detectives don’t get decent leads right from the get-go, their chances of solving the crime are seriously jeopardized.

Lauren Kieseritsky had two pieces of news for Franco Patrese.

First, they’d found a fingerprint on John Doe’s chest, and it belonged neither to him nor to Regina. They were running it through the system, so far without matches.

Second, they’d found a knife in the undergrowth on the Green: a hunting knife covered with Regina King’s blood. No fingerprints on it, and no evidence that it had been used on John Doe too. The knife was manufactured by a German company named Liberzon. Officers were trying to get hold of the company to check their US retail outlets.

Talking of John Doe – the Reverend John Doe – well, he was still unidentified. They knew that he wasn’t from New Haven itself or the immediate environs, as they’d checked every Catholic church within that area. They were now spreading that search outwards, looking for any missing priests within an hour’s radius of the city. If that brought no joy, they’d extend it to two hours’ radius, and so on.

No one had come forward to say they’d seen anything suspicious on the Green. Shortly before one in the morning, a couple had walked past the church and treeline in question and had seen nothing. Whoever had killed Regina King and dumped John Doe’s body must have therefore done so after that time.

This concurred with the medical examiner’s preliminary findings. Taking into account the bodies’ exposure to several hours of a crisp fall night and the subsequent effect on the temperatures of the cadavers, the medical examiner had put Regina King’s time of death as between 1.30 and 2.30 a.m., and John Doe’s as between 3.00 and 4.00 a.m. In other words, John Doe had been killed after Regina, in a different location, and then brought to the Green.

There were no bullet holes in the bodies, and no stab wounds to the vital organs. A full toxicological analysis was still pending, but the most basic tests had showed up no evidence of poisons, sedatives or intoxicants. Blood splatter and flow patterns – particularly the difference between pre-mortem and post-mortem bleeding – suggested that the victims’ arms and skin patches had all been removed post-mortem. It was therefore most likely that the act of decapitation itself had killed both Regina King and John Doe.

Wouldn’t they have screamed? Not if the killer had put a rag in their mouths. Certainly not once he’d severed their larynxes.

No sexual interference in either case. That was interesting. Dismemberment is usually sexual and often connected with picquerism, where the killer is aroused by stabbing, pricking or slicing the body; all obvious substitutes for penile penetration, of course. The slicing was here – both in terms of the missing arms and heads, and the patches of skin removed – but there was no sexual interference and no stabbing.

Criminology theory holds that there are five forms of dismemberment: the practical, the narcotic, the sadistic, the lustful and the psychotic.

Practical usually involves cutting up bodies to make them easier to transport or store, which didn’t seem to be the case here. Regina had been alive when she’d come to the Green; it was hard to see how removing John Doe’s head and arm would have made him materially easier to move.

Narcotic, as in the perpetrator being off his head on drugs; well, that was a possibility in Regina’s case, given the frenzy with which she had been attacked, but not for John Doe, whose killing had been a work of clinical precision.

Sadistic; unlikely, even given the gruesome method of death. Those things which would inflict unimaginable pain on a person, such as amputating their arm and removing their skin, had been done post-mortem.

Lustful: no, for the absence of sexual interference.

Which left psychotic. The killer was doing all this for his own reasons, and those reasons would be buried somewhere unfathomably deep within his psyche. It might turn out that they would find the reasons only by finding the killer, through traditional police work and evidence-gathering. Taking wild guesses at what was driving him might simply distract them from genuine leads.

But as for such evidence-gathering: well, so far there was no forensic evidence worth the name, as was often the case when bodies had been left outside. The police lab was doing its best, though no one was holding their breath for a breakthrough: not because the lab wasn’t good – it was as good as could be expected of any short-staffed, underfunded public body – but because this was real life, and in real life cases don’t get solved in fifty-eight minutes minus commercial breaks.

The tarot cards were part of a standard Rider-Waite deck, the most common tarot deck in the United States and Europe. They were trying to trace the manufacturer, but that was easier said than done, especially on a Sunday. Manufacturers tend to put their details on the packaging box, but not on individual cards themselves.

As for the symbolism of the cards, they’d managed to find some basic information on the Internet: the mighty Google, helping cops and porn fiends since 1998. ‘Hierophant’ was more or less a fancy ancient word for a priest: ‘Regina’ was Latin for ‘queen’, which would tie in with ‘empress’.

The curator at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library was one of the country’s foremost experts on the history and symbolism of tarot – the Beinecke had one of the oldest decks in the world, dating back to 1466 – but she was returning from vacation and wouldn’t be at her desk until tomorrow morning.

Kieseritsky had scheduled a press conference for an hour’s time. Patrese said he’d look after Kwasi, keep the press away from the world champion, and at the same time do some digging to try to find out what had happened to Regina King.

He hung up and dialed the Hyatt Regency in Baltimore, number helpfully supplied by Kwasi’s incredible memory. No, the receptionist said, we didn’t have a Regina King staying last night. Yes, sir, she was absolutely sure. Not in the general register, and not under the National Council’s discount rate block booking.

Could she have registered under a false name? Patrese asked.

Yes, the receptionist said, but only if she had a fake ID too: each guest had been obliged to present some form of photocard. The receptionist had a copy of the National Council’s own attendee list, and there was no Regina King on that either.

Patrese thanked her and hung up.

Regina had told Kwasi she was going to Baltimore. He’d dropped her off at Penn Station. She hadn’t gone to Baltimore. She’d gone to New Haven. Trains from Penn Station ran to New Haven too.

Time to go to Penn Station.

Patrese stepped back inside the apartment. Kwasi was sitting at a computer. Patrese noted without surprise that there was a chessboard on the screen.

He explained what he’d found out from the Hyatt receptionist, and said he was going to Penn Station to try to find out where Regina had gone from there. ‘I’ll give you my cell number. You got a pen?’

‘Tell me. I’ll remember it.’

Patrese did, and he had no doubt that Kwasi would.

‘Will you come back when you’ve finished?’ Kwasi said. He sounded so like a little boy lost that Patrese instinctively put a hand on his shoulder.

‘Sure, Kwasi. Sure I will.’

Penn Station was no one’s idea of a grand railway terminus, the kind of place movie crews would dress up in period detail and have steam trains come hissing to a halt beside men in thick tweed suits. It was a catacomb, mostly underground and as bland as it was dark. Armed police stood with their feet wide apart and tried to look as though they weren’t dying of boredom. The government had warned of terrorist attacks on transport hubs a few weeks back, so everyone was going through the motions of pretending to do something about it.

A bomb in this place might actually improve it, Patrese thought.

He found his way to the control center after a couple of wrong turns and a station worker who’d been less impressed by a Bureau badge than Patrese would have liked. The control center was half movie theater, half trading floor: rows of workstations, many of them empty, and an enormous wall covered in intricate maps of the railway system. Trains inbound and outbound were marked by little symbols in various colors. It looked pretty busy even now, midway through a Sunday afternoon. God alone knew what it must be like during a Monday-morning rush hour.

The train to Baltimore that Regina had said she’d catch had left at ten o’clock. The train to New Haven had left at exactly the same time: ten o’clock, on the dot. Patrese asked for CCTV footage of both platforms from the moment the gates had been opened until the moment the trains had departed. The angles weren’t great and the picture resolution left much to be desired, but after going over the footage in fine detail, often asking to rewind a frame two or three times, Patrese had to accept a simple fact. Regina had been on neither of those trains.