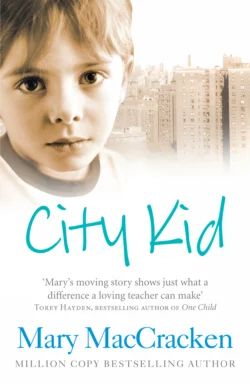

City Kid

Mary MacCracken

From the author of international bestsellers A Circle of Children and Lovey comes an inspiring true story of a gifted teacher’s determination to understand the ‘rotten’ city kid everyone has given up on.Sitting quiet and withdrawn at a battered school desk, Luke had the looks of a shy angel – and a past that special needs teacher Mary MacCracken could barely believe.Already Luke had been picked up 24 times by the police. He’d set over a dozen major fires, and had a staggering record of thefts. No adult could reach him, no teacher could control him, and no policeman could cow him. All this – and Luke was only seven and a half years old.Trying to help Luke was Mary MacCracken’s job – and a seemingly impossible challenge. This is the remarkable story of how the impossible came true.

(#u042f5711-346d-5f23-a1b5-d9f6af79f374)

Copyright (#u042f5711-346d-5f23-a1b5-d9f6af79f374)

This book recounts the essence of my experience and in that sense is a true story. However, it is not intended as a literal account and it is not to be taken as a portrayal of any living person. All names of individuals, places or institutions are fictitious.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

and HarperElement are trademarks of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

First published in Great Britain by Little, Brown & Company, Inc, 1981

This updated edition published by HarperElement 2014

Copyright © 1981, 2014 by Mary Burnham MacCraken 2014

Mary MacCracken asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Cover photograph © Diane Kerpan/Arcangel Images (posed by model)

Mary MacCracken asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780007555161

Ebook Edition © August 2014 ISBN: 9780007555178

Version 2014-07-22

Dedication (#u042f5711-346d-5f23-a1b5-d9f6af79f374)

For Cal:

who believed in me

Contents

Cover (#u839e5972-b0e2-5021-8ce5-4f4b73ba9324)

Title Page (#u55f41833-710e-5ca3-87c1-2323b89516fa)

Copyright (#ulink_c6cfb8d0-b202-59b2-a8e8-4019af138adc)

Dedication (#ulink_e9c79917-42a9-5063-b098-dc913152d04d)

The Fire Within (#ulink_6cbfad5f-6b70-5482-afc1-6441ff82c369)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_9c9debf8-0921-54e5-b017-6d6ae064d10d)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_21d476ec-0c26-5ed8-ac25-cb5eff82a255)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_6254c37e-c750-5951-b29f-b579654124d3)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_693b94bf-605b-5a8e-b83a-bc65b3439c02)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_5d6149f9-3ac0-5352-80d6-cac99e31e5f3)

Chapter 6 (#ulink_5a410699-981c-5f61-9d29-46f36ccc916f)

Chapter 7 (#ulink_c92660c0-6a6b-5ba7-8e03-d76e7e482cdc)

Chapter 8 (#ulink_713dde36-f590-51cc-993d-6ce232ee3d69)

Chapter 9 (#ulink_70210b6a-b44a-5b7b-9e83-d5e5b51407fd)

Chapter 10 (#ulink_c2ef6431-5cc2-5ed7-bde3-8ffe25591159)

Chapter 11 (#ulink_b81684be-f8a8-5af0-bde6-8df8f79c2aba)

Chapter 12 (#ulink_c9470b57-f247-5e65-9096-99c77323a8e8)

Chapter 13 (#ulink_611d37ef-58a9-59b8-8b88-fd7f7d972c65)

Chapter 14 (#ulink_82c69667-9ca3-5094-af0c-45408383e7fe)

Chapter 15 (#ulink_b9cd1754-0523-5cd3-aa2b-bfb915235035)

Chapter 16 (#ulink_218098a2-8726-5bb1-b65e-1bd5e0f714e0)

Chapter 17 (#ulink_ccb34394-864c-5151-b1f2-aff32270745c)

Chapter 18 (#ulink_8b5d623c-cd16-5936-b8bf-618be6bbb9f7)

Chapter 19 (#ulink_32607d9e-8774-58d6-8427-f031ea8bde8a)

Chapter 20 (#ulink_ea674a49-fe83-5d20-b573-4be9957b5fbf)

Chapter 21 (#ulink_49aee3bc-9674-593d-a0ec-ffde193de195)

Chapter 22 (#ulink_e94cf019-f92f-5d47-932d-7dcb320c566c)

Chapter 23 (#ulink_dca5257d-15fc-5c39-a904-52afcfec3b8a)

Chapter 24 (#ulink_00de93e8-5231-528e-9507-c0e80635904b)

Chapter 25 (#ulink_69f143cd-b229-5c83-8d12-62287579ee82)

Chapter 26 (#ulink_a0f05403-2286-542c-bdcc-1ea7e0ab23e4)

Chapter 27 (#ulink_45e475bc-6d71-55dc-ae62-9b2b63d29943)

Chapter 28 (#ulink_dbbaa136-e62b-5d90-a724-71ab3d71678d)

Chapter 29 (#ulink_dcdba31d-ce4c-5710-b302-83663c086ed1)

Chapter 30 (#ulink_26b100ee-5fdb-5f38-b5f2-924b2e266381)

Chapter 31 (#ulink_ee876bad-4a21-5bf4-9294-ddcb4f429f09)

Chapter 32 (#ulink_46c7ad79-8e40-5762-82a9-5ec17b3f9040)

Chapter 33 (#ulink_6b32518d-6b4b-5a02-9d2f-c0e676e7d757)

Afterword (#ulink_38eae321-fcaf-582b-8ae0-e2f32079c94d)

Coming soon … (#uec64751e-1b4a-5a07-a796-b26fe46e65d7)

Exclusive sample chapter (#ua191cdf1-9aca-5764-bf3f-0f621d158bd2)

Also by Mary MacCracken (#u858e62a3-5559-54a8-8fcc-ac4805f05fc9)

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter (#ue1ea9639-4ee2-566d-9ef1-bf1db7666455)

About the Publisher (#ucb75501a-cb60-5d2a-9a2a-2416f35a9b4e)

The Fire Within (#u042f5711-346d-5f23-a1b5-d9f6af79f374)

“Luke,” I said, “why do you like to start fires?” “Don’t know,” Luke said. “Just like to watch ’em. They’re pretty, all red and blue and orange, dancin’ around.”

“The big fire last fall? Did you set that?”

Luke smiled – and I hated that smile. “That one was real pretty. It kept on gettin’ bigger and bigger ’til it was taller than me.” Luke paused. There was no guilt or repentance in his voice, only admiration for the fire. “The cops came, then the fire trucks, but they couldn’t put it out – it just kept goin’.”

His voice sounded hard and cruel, not like Luke’s at all.

There was a fire burning within this seven-and-a-half-year-old boy – a fire that would destroy him if a dedicated but near-despairing teacher couldn’t find what fueled it and how to put it out.

Chapter 1 (#u042f5711-346d-5f23-a1b5-d9f6af79f374)

“Which one is Luke?” I whispered.

“There, next to my desk,” Lisa answered. “The one not working, of course. He doesn’t even answer when his name is called. Listen, I’ve got to go. Talk to you later.”

Lisa walked to the front of the classroom to continue the math lesson I’d interrupted. I sat on a radiator cover and studied Luke.

I couldn’t believe it. When they had told us at college that we’d be working with children who were socially maladjusted juvenile delinquents, I conjured up images of burly kids with bulging muscles and perpetual sneers. And now here was this little boy in second grade who couldn’t be more than seven years old.

I peered at him intently, saying his name under my breath, “Lucas Brauer, Lucas Brauer,” trying to make him real. He shifted slightly in his seat and I could see that his brown hair curved around his cheeks, so that from this angle he looked almost like a girl.

There must be some mistake, I thought. How could this child have a record of twenty-four arrests for arson, theft, and truancy? I shook my head. Something was wrong somewhere.

But if something was wrong, something was also right. For the first time in months, I felt the beginnings of the familiar, soaring, ridiculous excitement that came with teaching – a feeling I’d almost forgotten since I’d become a student at the state teachers’ college.

I had entered in September, full of hope and determination. By February I was full of disillusionment. In fact, until that day when I found Luke, I wasn’t sure I could make it through one year, much less two.

So now I memorized him – the scruffy sneakers half the size of mine, the faded jeans torn at the knees, a plaid shirt with one button missing, and each inch of his small profile. I could help Luke, now that I’d found him. I knew I could, and he would help me, too. He would make me remember there was some reason for the endless empty courses, the meaningless assignments, and the foolish terror of exams.

I had known it wouldn’t be easy, going back to college at age forty-four. In 1970 the movement for continuing education had not yet become popular and ninety-nine percent of the members of the junior class at Union State College were under twenty years old. They walked the campus in pairs or clumps, ate in noisy groups at the student union, shouted cheerfully at one another over the blare of rock that poured from speakers mounted in the ceiling. I walked alone, ate my cheese and apple in my old convertible, and tried to learn to be heard over the sounds of the Grateful Dead.

That was all okay. I was there to get a degree, to get certified so that I could continue teaching, not to develop my social life. I had remarried in June and the excitement of living with Cal and trying to blend our combined seven kids, aged fifteen to twenty-seven, into some kind of homogeneous group was challenging and absorbing. None of the children lived at home full time, but they arrived in bunches on weekends and vacations and filled our apartment or country house with excitement, laughter, and dirty laundry.

It would be difficult to give up teaching and go back to college after a twenty-five-year interval between sophomore and junior years, but it was also the one way I could continue to teach. What I hadn’t expected was the stifling boredom, the frustration of hours spent taking courses that had nothing to do with teaching, and most of all, the overpowering, unending longing for the troubled children I had taught.

I had been teaching seriously emotionally disturbed children full time for more than six years, when the school where I taught became “state approved” and its teachers had to be fully certified. I had no certification, only two years at Wellesley and some night-school education credits. Not enough. I had to leave because the only way I could continue to work as a teacher was to get a bachelor’s degree in education, and certification. I could get my degree and dual certification in elementary and special education in two years going full time during the day; it would take six years at night school. At my age there was no choice.

But where were the children? Children had been the warp and woof of my life for years. Without ever really asking, as an education major I had assumed that my days would be filled with children. Not so. They saved the children until senior year, and then only for six weeks of student teaching.

I railed inwardly at the poor preparation the young teachers-to-be were getting. How could they learn to be teachers without children, without the models of experienced teachers, without being in a classroom?

I remembered Helga, the wonderful teacher I had worked under as a volunteer when I had first started, and all she had taught me. Where would these young people learn about commitment and involvement and communicating with children? Not in my courses in Background of Mathematics I, Adapted Physical Education, Integrated Techniques, Current Methods and Materials for the Mentally Challenged, and Teaching Reading to the Mentally Challenged.

Of all my courses, Background of Mathematics I was the worst. Not only did it have nothing to do with children, it was also couched in a foreign language. Math to me meant addition, subtraction, multiplication, fractions, decimals. Maybe word problems and a few math concepts. Not so to Mrs. Kaiser, our professor. She talked of sets and union and commutative properties.

Each morning she said coldly, “Good morning, class. I will explain the work to be assigned. Follow now.” With that she turned her back to the classroom and the tight blood braid that ran across the back of her head bobbed up and down as her chalk made numbers, arrows, circles with overlapping circles, equations resting between and below her drawings. She talked rapidly to the figures on the board, never turning her head. She covered one, two, sometimes three of the blackboards that surrounded the room.

Then, “Volunteer?” she demanded more than asked. Five hands in the front row shot up. She chose two and sent them to the unused portion of the board. Then she read a problem out loud and the race was on. Who would finish first? Who would get it right?

I watched from the back of the classroom, never volunteering and hoping only for invisibility and sudden insight.

Ian Michaels, the boy in the seat next to mine, attended only every other day and never volunteered. Instead he silently scratched out the problem on a back page of his notebook. He was always right, always ahead of the blackboard people.

I decided I would try to do the same. I was beginning to understand some of the vocabulary now – matching sets, equivalency, the commutative property – but usually I got lost about halfway through the problem.

One morning Ian’s hand reached lazily across my paper, underlining the place where I had gone wrong, putting it right, then finishing the problem. After several days of this, I began to follow it through, while Ian dozed beside me, coming awake just before the end of class to circle those I had gotten right.

Dr. Kaiser was a believer in unexpected quizzes. She would sit wearing the same bland expression as we arrived each day, but twice a week, always on different days, after her “Good morning, class,” the scribble on the board was put there for us to solve on paper and hand in.

I began to wake in the middle of the nights from the sound of chalk on blackboard rattling in my dreams. My stomach was queasy on the morning elevator rides from the apartment to our cars.

“Are you all right?” Cal asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I’ve got a sixty-eight average and I dream about Mrs. Kaiser.”

Now Cal, too, studied the associative, distributive, and commutative properties, shaking his head, saying almost inaudibly, “This is math?” Cal was an engineer and inventor with over eighty patents. If he had trouble understanding Background of Mathematics I, how could I ever hope to get it straight?

I was okay in my other courses, averages in the nineties, but I wasn’t at all sure I would pass Background of Mathematics I.

I said so to Ian Michaels.

He opened his eyes slightly and looked at me through half-raised lids. “No problem,” he said between yawns. “Just copy my answers on the final. Then go back and mess up enough to get what you need.”

He closed his eyes again.

Cheating. He was suggesting that I cheat.

I knocked my sneaker on his boot. “That’s cheating,” I said.

His eyes stayed closed. “No shit,” was his nearly inaudible comment.

I wasn’t sure how to interpret this. I sat silently drawing circles on my notebook, watching the others file into class.

Everybody cheated. This was my first exposure to the marketing of papers. All the various societies and clubs on campus had a file of papers for every course, going back over several years. This was supposed to be a secret, but unless you were considered the type that would rat, the availability and cost of papers were discussed openly. Students mocked professors for giving an A to a paper that had earned only a B two years before. Copy machines made it possible simply to “rent” a paper for a day, copy it, return it, and then, depending on audacity and/or willingness to risk, either retype it or simply hand in the copy, saying you were keeping the original for your files.

Did anybody ever get caught? Not that I knew. Did the professors know what was going on? Again, not that I knew. But somehow the fact that it was happening contaminated the atmosphere. There was an “I’ll get away with as much as I can” philosophy among a large group of students.

The environment was so impersonal that the students often reminded me of little children with their hands in the cookie jar, wishing desperately that someone would catch them, just so they’d know someone cared.

Adapted Phys Ed was a two-credit course, which meant that we met only three times a week. As if to make up for this, Mrs. Hogan assigned twice as much work as any other teacher. Each class ended with a lengthy new assignment, and a moan from the students. Mrs. Hogan had graduated from Union State five years earlier. It was as if she were saying, “In my class, you’re going to work for those two credits.”

I admired her spirit, but wished she had a subject closer to my work. One of her favorite assignments was to ask us to write twenty abstracts on twenty different physical education articles. I spent hours in the library. Locating the article was a major problem in itself; often the one needed issue was missing from the stack. Then I spent more hours reducing articles on wheelchair volleyball and adapted jungle gyms to short abstracts, and still more hours typing them up. Where were the children? What was I doing here?

We were assigned to demonstrate before the class a “phys ed technique” that would be useful with “special children.” I could not do this. I had taught Rufus to swim, Hannah to ride a bike, Brian to climb a mountain, but I could not bring myself to stand before those forty nineteen-year-olds and put on a demonstration.

An old shyness returned, and for the hundredth time I thought, “I cannot do this. I cannot stay here in these classes for two whole years, while the children are out there.”

Cal put his arms around me in the middle of the night, and then wiped my tears. Neither of us spoke.

The next morning I wrote a letter to Mrs. Hogan asking if I could substitute a paper or else more abstracts for the demonstration. Perhaps because of my age, the letter came back. “Permission granted for substitution of twenty abstracts for class demonstration.” Back to the library.

If only I had known about Luke then.

Chapter 2 (#u042f5711-346d-5f23-a1b5-d9f6af79f374)

Our final math exam was on December 20. I was later than usual and I could feel nervousness building as I inched the car along the highway. It was snowing lightly and snow combined with Christmas shoppers made travel slow. I finally reached the college parking lot, found a spot heading downhill, and then walked rapidly across campus, quiet and beautiful under the fresh cover of snow.

For once, Ian Michaels was in his seat before I was. We always sat in the same seats. I don’t know why, but it was the same in all my classes. There was some slight juggling and changing the first week. After that we returned as though programmed to the same seat each day.

I hesitated inside the doorway for a minute. Maybe I should take another seat. Maybe I couldn’t resist looking at his paper, with the problems worked so simply, so elegantly, so clearly once I saw him do it Ian, I thought, whatever I have learned in this class, I’ve learned from you.

I sat down in my regular seat next to him. He opened his eyes to half-mast and winked at me.

“Listen,” I said, the wink catapulting nervousness into annoyance. “Keep your answers to yourself. I can do this on my own.”

The eyelids lowered. “Sure, lady.”

Thirty minutes later, Ian had handed in his paper and was gone. Forty-five minutes later, everybody was gone but me. On the hour, Dr. Kaiser announced, “Time’s up. Pass the papers to the front, please.” There was no one there to pass to. I carried my paper to her desk.

A week later, Dr. Kaiser stood in front of us. “I will announce both your exam grade and your final grade. Anyone who wishes to see his paper may request it after class. Barker, Frank – exam eighty-six, final grade eighty-two. Cavaluso, Florence – exam sixty-five, final grade seventy-eight.”

I studied my notebook, wondering how far Dr. Kaiser would go. Would she read the failures?

“Mann, Anita – exam forty-eight, final grade fifty-two.”

She would. She was – and she was already to the M’s. Could my stomach really churn like this over a math grade?

“Michaels, Ian – exam ninety-eight. Congratulations, Mr. Michaels. Final grade ninety-six.”

What was the matter? Where was MacCracken? MacCracken came before both Mann and Michaels.

“MacCracken, Mary. I always leave the Mc’s and Mac’s till the end of the M’s.”

She pinned me with her eyes. The others turned to look. Ian Michaels’s eyes were closed. My stomach rumbled beneath my jeans. Say it. Would you just say it and get it over with?

“MacCracken, Mary – exam eighty-eight, final grade, eighty.”

I passed! I not only passed, but a B! Exultation flooded through me. How could I care so much about a math grade? I felt foolish, but anyway, I wouldn’t have to take this course again. I did it! We did it!

Ian Michaels’s boot nudged my sneakers. Eyes half-opened, he gave me his accolade before lowering his lids once more. “Way to go, MacCracken.”

The second half of my junior year was still filled with required courses, but the ordeal of scheduling and registration was a little easier the second time around. I was getting to know most of the professors in the special ed department by name and/or reputation and that helped.

“Have you had Bernstein yet? Well, don’t if you can help it. He’s a pig.”

“Jones? A good lady. Marks hard, but knows her stuff.”

“Telker? Terrific if you need an easy B. Never gives anything lower.”

I wondered if the teachers knew their reputations were graven into oral history and available to anyone who listened.

Still, registration was always tedious, sometimes traumatic. We were classified like so many potatoes. With us, the identifying characteristic was the first initial of our last names. On the first day of registration names beginning with A through F were admitted; on the second day, G through L; on the third, M through R; and on the fourth, S through Z. The following semester the order would be reversed. Patiently we lined the walks and stairs and halls of the student union, where various rooms and floors had been partitioned into cubicles representing different courses. The faculty took turns at the adviser’s desk.

To actually get in the front door, an hour process in itself, took two things, your student identification card and your social security number. Nobody cared what your name was, only what letter it began with, to make sure you were with the right potatoes. After that you were known by your social security number. I wondered, as I stood waiting in boredom, if I could find my numerical relatives by adding up my digits and matching the total results. If I was a 46, who were the other members of my clan? Were there 42’s and 48’s around me? I contemplated the girl ahead of me, her hair combed into a high Afro; maybe she was a generic 40.

Behind me a red-haired woman in her twenties shifted from foot to foot. “What’s taking so long? Christ! If Statistics is filled by the time I get there, I’ll kill myself. I only need six more credits, but that one’s required. I’ll have to come back to this hole again next semester if I can’t get that course.” I understood. I had some required courses myself. If I didn’t get them I could quit, I told myself. I could stop taking these inane courses … but what about teaching? What about the children?

Inside, we raced frantically from booth to booth, checking our catalogs against our schedules.

Working with schedule sheets and catalog in hand, I was trying to keep to my plan of double certification (in both elementary and special ed), which meant I had a lot of courses to fit in. Trouble came when the course planned for 10:40 or 11:40 turned out to be filled; then there was a scramble for the catalog. What else have they got at that hour that’s required? Teaching math. Great. Nope – turned out it wasn’t allowed.

“You don’t have the prerequisite. You have to complete Background of Math Two first. Sorry, it’s the rule,” said the graduate student manning the booth.

The rules! I was beginning to understand the frustrations of some of my natural-born children and their friends. It had been different in a small private college like Wellesley, where students were honestly seen as individuals, or at least they had been twenty years ago. But in a state college like the one I was attending, there were no exceptions. As long as it came out right on the computer, it was okay. (Computers don’t make exceptions.)

Well, Statistics and Orientation to Psychological Testing didn’t have a prerequisite – and what’s more, it was required and met only once a week, on Thursdays from 4:00 to 6:30. I signed up. Finally, my spring schedule was complete: Counseling and Guidance for the Handicapped; Current Methods of Teaching Mentally Challenged Adolescents; History of Education in the United States; Background of Mathematics II; Statistics and Orientation to Psychological Testing; and a Practicum in Teaching Reading to the Mentally Chalenged. All required courses.

Schedule and course sheet in hand, I headed for Professor Foster’s office. I had discovered at registration that he had been assigned as my adviser and his signature was required on my completed course schedule. A stroke of luck to get him, I was told. He was considered one of the best.

Foster’s office door stood open and he sat with his feet on the desk, chair tipped back against the wall.

“Professor Foster?” I asked from the hall. “I’m Mary MacCracken. Could I see you for a minute about signing my course schedule?”

“Mary MacCracken? Where the hell do you keep yourself? I’ve been trying to locate you for weeks. Ever since I discovered you’d been a teacher at Doris Fleming’s school and have over six years’ experience with emotionally disturbed kids. Is that right?”

I nodded.

“Well, come in. Sit down.” He lifted a pile of journals from a chair beside the desk. “Do you ever hear from Doris? I’ve been out to that school several times. Damn good reputation, even before it got state approval. Those are tough kids. When did you teach there?”

“Until last year.”

“What the hell are you doing here?”

“Trying to get certified.”

“Ah, I get it. Last year is when the state approval came in, right? No tickee, no job, eh?”

I nodded.

“Well, Doris is a tough old war-horse, but she kept that school alive when no one else could.”

“Yes, she taught me a great deal.” Glad that I could say it. That the hurt of having to leave was easing.

“Okay now,” Foster said, “let’s get down to business. We have come up with a terrific idea.”

“We?”

“Yeah. Bernie Serino and me and the Falls City Mental Health Clinic. You know Bernie?”

“Yes. He was supervisor of special ed when I was teaching and helped me get one of my kids back into a regular class in junior high.”

“Yeah. Well, Bernie and I have lunch every Wednesday. A little business, a little pleasure. We’ve known each other a long time.

“In some of the districts they’re having a hell of a time with the younger kids. Not just truancy, you expect that, but stealing, setting fires, drugs – you name it. So what happens, they call the school social worker or psychologist, she adds a name to her list. Then the truant officer, they call him something fancier, but I don’t remember what it is, checks in. Nine times out of ten he comes back and says it’s a ‘broken home,’ either the father’s skipped or nobody knew who he was. All they got is uncles, Uncle This and Uncle That. Every time Mom gets a new boyfriend, the kids get a new uncle. Convenient, but unstable.

“So they have a conference and call up Bernie and tell him they need ‘special services.’ Well, about the only ‘special services’ Bernie’s got any connection to where he might get help for these kids is the Mental Health Clinic. They’re a good bunch, working hard in the community, but they got an even longer waiting list than the school social worker.”

He paused and I asked what he knew I would ask.

“What happens?”

“What happens?” Professor Foster banged his feet to the floor and leaned toward me.

“Same damn thing happens every time. By June the kid has moved up to number thirty on the waiting list. He’s been picked up by the police, taken to court, warned and fined, and released. The school year ends and the whole thing begins all over again the next fall.”

I said nothing. I sat looking at my hands, feeling the old familiar sadness as I heard about the children. What sense did it make? Any satisfaction I had felt at completing registration faded. What was I doing here in this college memorizing the commutative, associative, distributive mathematical properties and the content and study skills of reading?

I was so deep in my own thoughts that I missed the first few words or sentences of Professor Foster’s next statement, tuning in when he got to “… the Mental Health Clinic has gotten a grant to put ‘therapeutic tutors’ into one of the schools in Falls City on a trial basis. Bernie’s agreed and picked the school and I’ve offered to supply the therapeutic tutors.”

“What’s a therapeutic tutor?” I interrupted.

“Somebody who’s good with kids. What else? You can hear it in fancy words later. So what do you say?”

“It sounds like a good idea from what you’ve told me.”

“No. Not that. Will you do it? Be a tutor?”

“Me?” I couldn’t believe it. I answered instantly before he could change his mind. “I’d love to. Where do I go?”

Professor Foster smiled at me. “Don’t you want to know about credits – hours?”

I looked down, embarrassed and immediately shy. I had been too eager, revealed too much. I nodded.

“Well, first there’ll be training sessions at the clinic. Then you’ll see your child three times a week for about fifty minutes each session. Eventually you’ll have three children.”

In my mind’s eye, I could see the schedule of courses that I had just completed. Falls City was about twenty minutes from the campus; that would mean another forty minutes each time I went down. There wasn’t a day when there was a block of time long enough. Wordlessly I handed Professor Foster my schedule.

He studied it briefly, then whacked it down on the table.

“What the hell is this? How could you sign up for classes before you checked with me? Am I your adviser or not? Why didn’t you ask for advice?

“Never mind,” Foster said after a minute, picking up my schedule. “Sorry. Didn’t mean to yell. Let’s see what we can do.” He studied it closely and then grinned at me. “At least you’ve got good taste, picking ‘Counseling and Guidance for the Handicapped’ – that’s mine. Unfortunately, it’s only a two-credit course, but at least that gives us a couple of hours to play with. Mmm-de-dum-dum.”

Professor Foster hummed to himself as he flipped through catalog pages, checking them against course requirements and my own schedule. Finally, he looked up at me and said, “That’ll do it. Drop History of Ed and take Independent Study in its place and spend the time of my course at School Twenty-three and you’ll be all set.”

“What’s Independent Study? And what do I do about History?”

“Independent Study is whenever I want you to do something. I just write up a slip and send it to the dean. You’ll get your three credits.”

“Power,” I said.

“What was that?”

“Nothing.”

“Okay, now. Go on back to registration before it closes and drop that history course. You can always take it next year, there are plenty of sections. Here’s a note if you need it.”

“Thank you,” I said as I stood up. “When, where will I start?”

“Well, the other two tutors are both seniors with much more freedom in courses, so scheduling will be a lot easier for them. Let’s see your schedule again. Okay. You’ve got some time on Monday afternoons. We’ll meet down at the clinic at two.” He glanced out his door. Four pairs of blue-jeaned legs could be seen below the hall bench.

“Ah. Gotta rush now, way behind. See you next Monday. Call the clinic to get directions down there. Sorry I can’t talk longer.” He was already standing, tucking in his shirt, smoothing back his hair.

The line was still long at the student union. I went up to the guard at the door. “I’ve already registered. I just want to drop one course. Is it all right if I go in?”

“Name, please.”

“Mary MacCracken.”

“MacCracken. M. That’s all right. Social security number?”

“No. Look, I’ve already done this. I don’t need to regis –” it wasn’t any use. I was just wasting time. I sighed. “One four seven –”

“All right. Step to the back of the line. No exceptions.”

I went back. Six new people in line since I arrived, but I should have known better than to ask the guard. There were no exceptions on the lines, only in professors’ offices.

But if the system bothered me, it couldn’t snuff out the small bubbles of excitement surfacing inside me. What kind of children would they be? What were we going to do together? Who would be my child?

Chapter 3 (#u042f5711-346d-5f23-a1b5-d9f6af79f374)

It was cold, even for the end of January, and the fact that there was no snow made it worse. The campus looked bleak and bare, and the contrast with the remembered warmth of Christmas made it even more difficult for me to return.

We had spent most of vacation and winter break at our house in the country. We cut our own tall, wonderful, scraggly Christmas tree and carried it up from the woods. We hung eleven stockings in front of the stone fireplace, ours and the children’s and the grandparents’ and friends’.

The house was not meant to be a winter house. Cal’s parents had built it for summers fifty years before. It took days to warm the stone walls and floors. The small furnace worked valiantly, shedding soot as well as heat. Gusts of wind and small mice scurried through chinks in the stone walls to the inside warmth of the house.

In the mornings we lay in bed and blew smoke rings of warm breath into the frosty air and then rushed from bed to shiver by the window as we watched deer leap across the meadow. We ate simple meals and trudged along un-plowed roads, chopped logs and read and talked quietly to each other. Happiness was almost visible that week.

Vacation over, spring courses began. I wondered if every one had as hard a time coming back to school as I did. But I did have seventy-six credits now – five A’s and a B – and fifteen more credits coming up this semester. If I could just get through Statistics and Orientation to Psychological Testing and Background of Mathematics II, I’d have ninety-one by May. And now, thanks to Professor Foster, there would be children.

Many of the faces in Background of Mathematics II were familiar, but instead of Dr. Kaiser, the teacher was a man in his thirties, wearing black horn-rimmed glasses – and there, sleeping beneath a grubby tennis hat, was Ian Michaels. My spirits lifted.

I stepped over several pairs of blue-jeaned legs and settled beside Ian, who continued to sleep, or to pretend he did.

On the board was written Background of Math II. Beneath this was the statement:

A denumerably infinite set is one that can be put in a 1–1 correspondence with the set of counting numbers.

Oh, no. Here we go again. I had thought we’d at least be to something like fractions.

I opened my notebook and copied the statement down anyway; I could puzzle over it later.

A familiar hand reached lazily across the page and scrawled an example.

Ex: The set of multiples of 5 is a denumerably infinite set.

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, … n …

5, 10, 15, 20, 25, … 5n …

I looked at what Ian had written. Okay, I see that. I smiled at Ian’s tennis hat.

“Thank you,” I said, settling back in my chair. “The one thing I’m good at in math is knowing how to pick the right seat.”

If classes at college were as frustrating as ever, our training sessions at the clinic were fascinating.

The Mental Health Clinic was in the center of Falls City on the second floor of the Logan Building, and although the streets were littered and the surrounding buildings shabby, there was a lingering ambiance of power and elegance.

In earlier years Falls City had been a leading manufacturing center. Its chief industries were the dyeing and finishing of textiles and the manufacture of silk. But with the rising popularity of synthetic fabrics, business declined and companies closed. Although pockets of culture remained, the downtown area had become drab and rundown and the population was predominantly lower middle class.

Inside the Logan Building, shabbiness was more evident. Water stains marked the ceilings, walls needed painting, floors were bare, furniture was folding metal. But there was a lot of space, a large waiting room, several secretarial offices, and a half-dozen rooms for therapists to meet with clients. Some rooms were furnished with chairs, table, and couch; another had low furniture and toys for children. We met in the children’s room.

The other two tutors were both seniors, Shirley Hayes and John Hudson. Shirley was quiet, with a soft sure voice and dark smooth skin. Hud was tall, slender, red-haired, filled with vitality. Shirley was going on to graduate school next year, and was working now as a clerk in a department store after her college classes to earn tuition. Hud was job-hunting, hoping to teach teenagers with emotional problems. I liked them both. Hud had worked with multiply handicapped children at summer camp. Shirley with disadvantaged children at a day care center.

Jerry Cotter had been put in charge of the program and conducted our training sessions. He was small, with a brown-gray beard and a gentle handshake. His official title at the clinic was psychiatric social worker.

At our first meeting Jerry said, “This program could be the beginning of a revolutionary change in the treatment of emotional problems in children. The central idea is to expand and intensify mental health services in the schools themselves, instead of letting kids vegetate on waiting lists. We are going to try to do this through therapeutic counseling and tutoring at the school – and you are the ones who are going to do it.”

At later sessions Jerry stressed again that help would go to the child in a familiar place, his school, rather than the child going, or waiting to go, to a clinic. He also said we would not be asked to work with psychotic children, the ones who were so disturbed that they would be considered autistic or schizophrenic. He smiled at me. “These children are not as out of touch with reality as the children you’ve worked with, Mary. Instead, they take their anger out on society, stealing, burning, destroying, and earn the label of ‘socially maladjusted’ or ‘juvenile delinquent.’”

I smiled back but didn’t reply. Labels meant little to me. In fact, as far as I could see, their only use was to give a name to a program so it could be funded. Nobody funded anything without a name.

The next four sessions focused on diagnostic tests and teaching procedures. Jerry demonstrated the administration and scoring of various tests given to screen for emotional or neurologically based impairments. We, of course, did not have the skill to score the tests ourselves, but we were all amazed at how much information he was able to obtain from such seemingly simple devices.

Our last session was on observing and charting behavior. Jerry gave us stopwatches and taught us how to use observation charts, marking down the number of incidents of a child’s disruptive behavior during short intervals carefully timed by the stopwatch.

At the end of this session, Jerry said, “That’s it. I, of course, will be at the school scoring tests and supervising from time to time. The grant covers the rest of this year and I’ll get over as much as I can, but we’re short-handed here and you’re going to be more on your own than originally planned.

“Anyway, good luck. I’ve enjoyed our sessions together and I’ll see you all at School Twenty-three on Wednesday.”

How could I wait till Wednesday?

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/mary-maccracken/city-kid/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Mary MacCracken

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 493.36 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From the author of international bestsellers A Circle of Children and Lovey comes an inspiring true story of a gifted teacher’s determination to understand the ‘rotten’ city kid everyone has given up on.Sitting quiet and withdrawn at a battered school desk, Luke had the looks of a shy angel – and a past that special needs teacher Mary MacCracken could barely believe.Already Luke had been picked up 24 times by the police. He’d set over a dozen major fires, and had a staggering record of thefts. No adult could reach him, no teacher could control him, and no policeman could cow him. All this – and Luke was only seven and a half years old.Trying to help Luke was Mary MacCracken’s job – and a seemingly impossible challenge. This is the remarkable story of how the impossible came true.