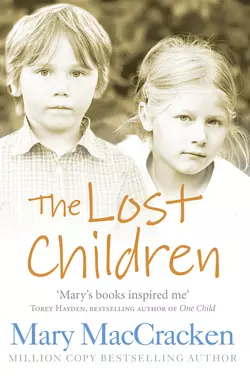

The Lost Children

Mary MacCracken

First published in 1974 as A Circle of Children this is the first of four books from learning disabilities specialist Mary MacCracken.This is a book about children so emotionally disturbed they cannot fit into society; it is also the story of a woman whose involvement with these children changed the shape of their lives forever.When Mary MacCracken joined a school for emotionally disturbed children as a volunteer, she quickly found herself rocked to the core by the strong, loving people who taught there, the hard-pressed and bewildered parents, and the damaged children. On the outside most of the children looked healthy. But the reality was far sadder. Locked away from love and any human contact, these children struggled with life every day.It soon became evident that Mary MacCracken was a natural, gifted teacher. Using her instincts, observations and common sense, Mary was able to establish a rapport with even the most difficult children. Over time, Mary taught her class to eat and to drink; she decoded their mutterings, and taught them to talk and to read. But most important of all she helped them to take the first steps towards feeling love and trust.There are no miracle-workers in this story, only a remarkable woman who refused to give up. Heartfelt, moving and incredibly inspiring, this is an amazing story about the astonishing human capacity for growth and change, even in those whom society regards as beyond help.

(#u810c750e-ba6b-5fb5-b910-f36c64c0d36d)

Contents

Cover (#u993efa4d-eb67-5e3a-8715-e97de2e1a510)

Title Page (#ulink_87bcdcb2-e964-5db1-ac0a-878faafaf865)

Dedication (#ulink_af08fb6c-7213-5add-be89-c25b75a499bb)

Epigraph (#ulink_4551adef-2b7c-5fd1-b312-1a53b5752cdf)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_57a6d546-629c-5034-96ff-9a0899408905)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_7ca1eaba-e213-5bc5-964a-0f6f9bcd9e52)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_056e61e5-5b13-5e01-a410-122e5613469c)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_66dccbff-e27e-5881-9b9c-0086c274c1f2)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_05a1cd82-2099-5a7d-a423-4e49b42ab066)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Teacher (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Mary MacCraken (#litres_trial_promo)

Coming soon … (#litres_trial_promo)

Exclusive sample chapter (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Dedication (#u810c750e-ba6b-5fb5-b910-f36c64c0d36d)

For my mother and first teacher:

Florence Ferguson Burnham

Epigraph (#u810c750e-ba6b-5fb5-b910-f36c64c0d36d)

He drew a circle that shut me out –

Heretic, rebel, a thing to flout.

But Love and I had the wit to win:

We drew a circle that took him in!

– Edwin Markham

Chapter 1 (#u810c750e-ba6b-5fb5-b910-f36c64c0d36d)

I encountered the school without warning, sandwiching the appointment between one at the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) and another at the Cerebral Palsy Clinic, where I had been many times before. It was to be a routine visit; my tennis racket was packed in the back seat of the car in case we finished early enough for a set before our children arrived home from school.

And now, nothing can erase that room, that school. In the slide file of my mind it has a perfect print: each line and shadow as clear now as it was on that first morning. Sunlight slanted across the blue-painted floor surrounding the woman at the piano dressed in a flowered blouse, rose and green, and a green cotton skirt. Small chairs were placed in a semicircle around the piano, and in them sat perhaps twenty children and six or seven adults. The adults, particularly the man, had their knees bunched up to their chins, and yet they seemed comfortable, smiling, calling back and forth across the room to each other.

But there was something strange about the children. It was not their bodies; no one was deformed. In fact, most were beautifully made. There was a translucent quality in their faces, but there was also something more, or perhaps less: a stillness in their expression. These children did not call to each other or playfully poke or tease; instead they sat silently, turned inward.

Suddenly the room became filled with noise and motion. Chairs were shoved to the edge of the room while the Director thumped loudly on the piano. The children galloped in pairs around and around until suddenly one tiny girl broke away and flung herself to the floor, screaming high-pitched, indecipherable screams. Her small legs, clad in red tights, were rigid, spread-eagled against the blue floor. She pulled her plaid skirt over her head and beneath it screamed:

“Vacuum cleaner. Look! Aaaaahhh. Aaaahhhh. Get it! Oooohhh. Aaaaahhhh. Get it! Here it comes! Aaaa. Aaaa.” She sat up, pointing toward the door. Her terror was real: I felt it inside me, and I turned towards the door, expecting to see a monster vacuum cleaner rolling in, motor running, upright, unstoppable, sucking us all into its giant bag.

But there was nothing, and gradually the terror in the room dissolved. The piano quietened and moved to the smoother rhythm of a waltz, and the children changed from galloping to a skating motion, pushing their feet across the blue floor. No one had stopped to look at the small girl in the middle of the floor or for the vacuum cleaner: they skated on, stepping over her arm or leg if they were jostled and pushed too close to her.

Only her teacher knelt beside her, talking softly, touching her shoulder, her hair. Then gathering her up, she held the child against her own body until the terror dissolved, was gone. As surely as I had seen the vacuum cleaner, I felt the loving that had displaced the terror. In that instant, that clear, bright second, with no warning, I knew that I would one day work in this school. I felt I had been here before, some other time or else some other place; it was familiar. I was at home.

They stayed like that, the child standing, the woman kneeling with her arms about the child for perhaps a minute more; then the little girl’s enormous eyes left the door and she put her hand against the teacher’s head. They rose then and, hand in hand, rejoined the circle of skaters.

The woman beside me touched my arm. “My God, Mary, I can’t take much more of this. Let’s get out of here.”

I turned to look at her, my friend Ellen, here with me on the assignment from the Junior League to investigate the school for seriously emotionally disturbed children, to visit and see if it would have good placement jobs for our volunteers; and she seemed suddenly far away. I had known her since I was a child, I had been with her when she bought the tweed skirt and blue cashmere sweater that she was wearing; and yet when she spoke to me it was as if her words were coming from a distant country. How could we leave? It seemed to me that we were on the brink of an enormous secret.

Then as my thoughts returned to her, I saw that she had been moved, but not to wonder. Revulsion showed in her face, and I did not know how to tell her about the excitement that I felt.

I followed her away from the room, out onto the porch of the big old white-frame building that housed the school. She said again:

“Mary, this place is terrible. They’re crazy. Those children are crazy. Mad. Just little kids and they’re completely gone. No one in the League could work here. Think what it would be like to go home to your children after this. Come on, let’s go. We’ll have lunch and then we’ll go to the C. P. Clinic and still have time to get in some tennis before the kids get home.”

Crazy. Were they? And what does “crazy” mean? Did she think perhaps that it was catching – that we might take it home to our children, like measles or a bad cold? What was it? What caused it?

“You go,” I said. “I’ll just be a few minutes, talk to the Director, get some pamphlets and a little information, and then I’ll meet you for lunch, okay?”

Ellen looked at me curiously. “You’re going back in there? What for? There’s no point.” Then perhaps recognizing some stubbornness in me reminiscent of our childhood, she sighed. “Oh all right. You’re a good, responsible placement chairman. Where do you want to eat?”

Ah, good. She was going. “Doesn’t matter. Anywhere. You choose.”

“Well, I did want to pick up a wedding present for Betsy at Jensen’s. Suppose I do that – then I’ll meet you at Lord and Taylor’s and we can eat there.”

“Great,” I said. “I’ll see you in an hour.”

I stood on the steps of the school watching Ellen pull out of the driveway, excited, but knowing that there was still time to change my mind. Instead of going back inside, I, too, could leave. I could get into my car, raise the white convertible top, and drive my way back to my safe, suburban life. I could surprise Ellen at Jensen’s, and while she shopped I could linger, drinking in the lovely things, touching a silver bowl, running my finger along the edge of a crystal vase when the salesman turned away, comfortable in a familiar world.

And what if I went back inside? What then? What kind of world lay there, just a few feet away? If I opened the door what would I find – what would I learn?

I lingered a moment more on the steps – then I turned and went back inside the school.

The Director’s office was in the basement, past the lunchroom. There was a musty smell; and though the walls had been painted yellow to compensate for the lack of windows, there was a distinct greenish cast to both the walls and the air. I stood in the doorway of the office; the Director, Mrs. Fleming, was on the phone and I waited hesitantly in the doorway until she finished.

The rest of the memory is blurred. I know I asked many questions and she replied with words like “emotionally disturbed,” “schizophrenic,” “autistic,” which rolled across my ears as sounds rather than words, almost meaningless to me then. She mentioned the school’s tremendous financial needs, the ratio of four children to one teacher, the newness of the field, the lack of agreement as to causes: some experts citing heredity, others environment, still others, biochemical causes. She spoke of the waiting list of children they could not accommodate and her dream of a new building, a larger school.

“The children?” I asked. “Can you tell me a little more about the children?”

“Well, as you can see,” she said, “they are physically healthy, attractive children. Their intelligence is average or above average, but they’re ill, and this illness causes them to function far below their age level, to live inside themselves and shut out the world. They are not sure who they are. They have great difficulty with language, with relationships, with other people; their behavior is often bizarre, puzzling.”

I stayed well over an hour, fascinated, intrigued, forgetting the time until I heard the children gathering in the lunchroom.

But excitement bubbled inside me, could not be put down. I wanted to teach there. Absurd? Perhaps. But I wanted it, had to do it, knew that I could. Unsure of many things, I was sure of this. One last question: What qualifications did her teachers need?

The Director smiled, “Certification in special education – preferably a master’s degree in teaching the emotionally disturbed – a listening heart and a strong back.”

I thanked her. My own heart was very quiet. I hadn’t even finished Wellesley, having left at the end of my sophomore year to marry Larry.

Chapter 2 (#u810c750e-ba6b-5fb5-b910-f36c64c0d36d)

But all summer long the children of the school walked through my dreams, and in September I went back to the school to ask if I could work there as a volunteer teacher’s aide two days a week. The morning was warm and the windows of the school were open, and I heard again the piano as I climbed the wide wooden steps.

More strongly than ever the déjà-vu feeling returns; perhaps not this same school, but somewhere, sometime, I worked in a school such as this. There is a remembered knowledge that is certain without being specific.

I find the Director in her office.

“Good morning,” she says. “Can I help you?”

“I’m Mary MacCracken,” I remind her. “I was here last June. I … uh. Well, what I wondered was … do you think it would be possible for me to work as a volunteer with one of your teachers?”

“Oh, yes, I remember now. You were here with the other woman from the Junior League. Yes. Well now, let’s see. Yes … I think we’ll put you as a teacher’s aide with Helga. We’re delighted to have you, Mrs. … er – uh …”

“Mary,” I say. “My name is Mary.”

“Yes, of course. Mary. Go right on up to Helga’s room. As I say, we’re delighted to have you.”

I climbed the empty stairs slowly. There was no one in the room at the top of the stairs. As I stood in the hall indecisively a boy of perhaps nine or ten raced by me, his turtleneck shirt pulled completely over his head, screaming, “Jesus Christ, gonna go to Camp Lookout! God save us all!” He thundered down the stairs, and I wondered how he was able to judge their height and depth with his eyes covered.

A man came out of one of the rooms along the hall, smiled at me, and called softly to the boy: “Hey, Tom, it’s okay. Camp’s over, you’re in school,” and he walked slowly down the stairs toward the boy, who was now hesitating on the bottom step.

I continued walking along the long upstairs hall, looking in classrooms, searching for Helga’s room. They were all empty except for one classroom. A small girl watched in fascination an empty turntable revolve. A gray-eyed boy sat beside her, smiling and rocking back and forth, back and forth, until a young woman rose from the table where she was mixing paints and touched him, blocked the rocking with her hand, and he followed her back to the paint table.

A kaleidoscope of impressions was whirling through my head. Was this teacher Helga? And would she, too, be “delighted” to have me? As it turned out, she was not.

I found her finally in the bathroom with her class of four children. She was bent over the toilet bowl with a rubber plunger.

“God damn fucking stopped-up toilet. How can you toilet-train a child when the stupid toilet doesn’t even flush? Who are you?”

“Mary,” I answer. “The Director sent me to be your new volunteer teacher’s aide.”

Helga wields the rubber plunger even harder now – brown-gray hair flying straight out from her head, glasses slipping to the end of her nose. She must be fifty, arms strong and muscular, moving up and down, everything about her alive, filled with vitality. She is wearing a cotton housedress, and under it I can see wide shoulders, full breasts, narrower waist and hips – her legs strong and bare above worn, wet sneakers.

“For Christ sake,” she says in a strong German accent. “How many times do I have to tell her I don’t want any shitty volunteers? I have enough to do with the children. Go on now. Go tell her to assign you to somebody else.”

But I do not want to go. Intuitively I recognize in Helga the essence of the master teacher. I know that she is the one I want to watch; hers are the techniques I want to learn. In this school I do not feel humble or frightened or inadequate, as I often do with Larry. I am at home here and I merely smile at Helga and follow her back to her classroom, watching her quietly. I had never heard a woman swear like that before. The women I had known most intimately were lovely, quiet women – clean and soft, smelling faintly sweet, dressed always in good taste. I survey Helga in her cotton housedress and worn sneakers, and for the first time I wonder what “good taste” means.

Sunlight lies across the green linoleum floor. The walls are covered with children’s primitive finger painting; a large rocking chair is in front of the window, a low table with chairs in the middle of the room, a sandbox on the far side.

One of the boys stands in the sunlight watching the specks of dust move in the golden air currents. He is very small, perhaps five or six, with a small, square face and large gray eyes, black at the center.

Helga speaks to him. “Take off your sweater, Chris. Hang it up on the hook.”

Still he stands without moving, arms slack; only his eyes follow the golden specks of dust. I do not move to help, only watch as I sit on a corner of the sandbox, filling a muffin tin with sand and turning my muffins on a wooden board. Red-haired Jimmy sticks a crayon in each one and then pushes them back to the center of the sandpile.

Helga ignores Chris, giving him a chance to act on his own volition. She notices me and is obviously annoyed that I am still there. She no longer even addresses me directly but instead mutters toward the window concerning me.

“God in heaven. Give me patience. It is not enough that I must teach these children all day with no equipment, only leftover material and promises. Now they send me volunteers. Over and over I have told them I do not want the shitty volunteers. Volunteers to do for the children what they should do for themselves. Do they listen? No. Jesus, deliver me from these volunteers. They should take their shitty good works somewhere else.”

The last is delivered pointedly in my direction and I bend my head in concentration on my muffins.

One last remark from Helga: “Ah – well. It does not usually take us too long to get rid of them, does it?”

Helga chooses now to ignore me. All morning she never looks again in my direction. Instead, she turns once again to Chris. Her voice lifts, half a command, half a seduction: “Come now – get off that sweater and we’ll have a bit of a rock before the day begins.”

Chris slides his eyes from the dust specks toward Helga, not moving, only looking.

She settles herself in the rocking chair and sets it in motion. “Come along now,” she calls, “get along.”

And, unbelievably, the slack, motionless figure becomes a boy. Awkwardly he takes off his sweater and hangs it on a hook beneath his name, CHRIS, and then crosses the room and climbs into the wide lap of Helga. And with her legs spread wide and her foot tapping she sings to him:

“Camptown races is my song – do dah, do dah. Camptown races all day long, all the do dah day.” And if the words are wrong, it does not bother Helga or Chris.

I watch them and then, noticing an empty coffee cup lying beside the sandbox, I go next door to the bathroom and fill it with water.

“Not this one,” I say to myself as the water runs into the cup. “You will not be rid of this volunteer so easily, Helga.” And I smile at her as I carry the water back to the sandbox.

So began our relationship, Helga’s and mine, and my education. I learned more from this strong, loving woman than from any psychology or education course I have ever taken; more than from any book, no matter how distinguished the author. I watched her, remembering, imitating, gradually doing. She breathed life back into the children. Often I watched her gather a child in her arms – one who had gone off to a corner, retreating from the world. Helga would gather him up, blow on his neck, murmur some foolish joke into his ear, take his hand, start the record player, and then dance with him around the room. Her favorite dance was the polka, and as she skipped and stomped in her sneakers, gray hair flying, half carrying her small partner with her, she would sing, “There’s a garden, what a garden, only happy faces bloom there, and there’s never any gloom there …” And gradually the child would return, the faraway look would go out of his eyes, and he would seem once more to be alive, to be back in this world.

There was about Helga such a strong sense of living, of vitality, that as she came into bodily contact with a child – rocking him, holding him from attacking himself or others, kissing him, pushing him – her vitality, her excitement, her desire of life were almost visibly transferred to the child. She could not have told me any of this herself; she was totally absorbed in her work, in her children – so much so that even at the end of the same day, if someone had asked her to describe what methods or techniques she had used to solve a problem, she would not have been able to relate what she had done. She would not even have tolerated the words “methods” and “techniques”; she was the totally natural therapeutic teacher. I was privileged to be able to watch her, and I knew it. A dozen times a day I would find myself silently saying, “Yes, yes,” as I watched her with the children. It was a feeling of silent applause and I knew I must pay attention to it.

She had that rare quality of being alive, involved in, excited by, her world. Whether this is learned or an inherited talent I am not sure, but it was one of her most valuable tools in reaching these children: the electricity that was vibrant in her reached across and touched the child, often before words could.

Helga’s husband Karl worked at a clerical job; their only son was grown, living in the West, They lived in a small upstairs apartment in a two-family house, saving money all year in order to travel. Each winter during Christmas vacation they went to Puerto Rico; in the summer they rode bicycles across Europe. Looking at Helga, I would think of my own friends, my own life, our large homes, all our possessions – and yet Helga had achieved a freedom, a sense of joy, that was absent in my own life.

It was not that she always had an admirable response or even a proper one. She did not. She was no saint. But the thing was, she did respond! She was alive, she was human, she cared, and she showed us that she did. There were no pretenses to Helga. What she felt, she communicated, and because there was no veneer it came through straight and clear.

If a child, as he gradually learned or rediscovered words, came to Helga saying, “Kite,” Helga would listen, repeat, “You like the kite. Ah – get it then. Get the kite. Let’s see it now, this red kite.”

And now Jimmy, excited by the sight and feel of the kite, tugs Helga’s arm: “Kite. Fly kite. Fly kite.”

Helga sits back on her heels from where she has been kneeling beside the boy and says, “Ah, fly the kite. So you think we should fly the kite, leave our papers and crayons, and go fly the kite. Is that what you think?”

Jimmy, ordinarily listless, pale as milk beneath his red hair, hops up and down with excitement. “Fly kite, Helga. Go fly kite.”

Helga grins, satisfied with her work, with the extra words she has managed to extract from Jimmy, and says, “All right, you monkey – we’ll leave the work and go fly the kite.”

And soon all of us – the four children, myself, and Helga – have on our jackets and are trudging out to the field beyond the school, Jimmy carrying the kite. Then they run, the small red-haired boy and Helga in her sneakers. They run holding the string of the kite together, getting it started – until suddenly the kite lifts and sails up high, like hope itself, flashing, tipping against the sky, and we cheer and clap our hands.

I cannot remember now how many weeks it was before Helga spoke to me. I remember that I felt no resentment because of her silence. It seemed to me a logical thing: she was trying to do something important, and volunteers got in her way; it was natural that she be impatient with me. At the same time I had no intention of leaving.

There were other teachers in the school who were good. I watched them in morning assemblies and in the playground and at lunch, but none of them rang the bell for me the way Helga did. Her children grew faster than any others, became independent sooner – or so it seemed to me. I knew I could learn more from her than from anyone else. Whether she liked me or not was not essential. I was not lonely. I did not need her friendship; I needed her example.

For instance, I watched her teach Sarah to walk. Sarah did not walk at all when she first came to school. She was five, with pale yellow hair and the fine, silky skin of a baby. She was a week late starting school because she had been ill, so I was there when she came that first day. Her mother carried her up the stairs to Helga’s room, spread a blanket, and laid her on the floor. There Sarah curled up on her side, her thumb in her mouth. Helga said nothing; but after the mother had left, Helga slipped the blanket from beneath Sarah, folded it, and put it in the back of a closed cupboard. The little girl whimpered and cried, the other children circling around her as I have seen a flock of sea gulls do when one of the birds is injured. The morning was ruined, the children upset and fretful; no work could be done with Sarah mewling, crying, there on the floor. Another teacher might have let her keep the blanket that first day while she adjusted to the school. Not Helga. She would set no such precedent in her classroom – a five-year-old child was not treated like an infant, left lying in a blanket.

Finally Sarah moved. Painfully, slowly, she crawled across the floor, stopping every few minutes to rest, then continuing her slow, tortuous journey as we watched, holding our breath. She made her way directly to the cabinet where Helga had put her blanket, and scratched with her tiny hands at the door. Helga picked her up then and carried her to the rocking chair, talking to her, mixing German words with English:

“Come now – come now, little one. It is all right. Everything will be all right. I know you now; you cannot fool Helga. You are smart and you can move. You try to fool us, ja? Lying there, sucking on your thumb. But you are smart, ja? You know just where I hid that blanket, and when you want it enough and I do not bring it to you, then you yourself go to get it. Ja, ja, my little one, my pretty golden one, we will teach you to talk and to walk.”

Helga rocked her then and sang to her. Each morning after that, Helga greeted Sarah at the front door and carried her up the stairs herself. She did not wish to explain to Sarah’s mother what had happened to the blanket – that it now lay discarded beneath a box of old records in the recesses of the cabinet. Before long, it would disappear altogether. Dealing with parents or the public was not one of Helga’s strong points; she left that to the Director.

Sarah crawled more and more on the green linoleum in Helga’s room, gradually strengthening arms, legs, curiosity, as she explored the room. A small rag doll was her favorite toy. She would find it and play with it long hours at a time. One morning, before Sarah arrived, Helga moved the doll from the floor to the top of one of the low cabinets. Another frustrating, miserable day for all of us – worse than the first because now Sarah had a temper. She not only whimpered and whined; she screamed and kicked her heels against the floor in rage – but two days later she stood for the first time, pulling herself up until she could reach the top of the cabinet, reach her doll. And when she had it safe in one hand, balancing herself with the other to stay upright, she laughed out loud in triumph. Helga let her have her triumph, shaking her head, saying, “Ah, you, Sarah, such a girl. You are too smart for me. Too smart for old Helga. You find that doll no matter where I put it.”

From crawling to walking to climbing that long flight of stairs to Helga’s room. At first Helga stayed where she could cushion the fall if it occurred. Then, as confidence grew, she moved on ahead so that Sarah could see her there, have incentive to move ahead – not begging or pleading with the child, simply waiting, expecting her to be able to do it. And she did. Even then Helga’s praise was short – one word: “Good!” – brief, clipped: “Hang up your coat now. We’re late.”

Helga, wise, strong, letting Sarah savor the pride in her own accomplishment, not setting up a new dependency. Even the morning, many months later, when Sarah came up the whole flight, breaking away from her mother at the door, walking fast, climbing without holding on, up the stairs, up to Helga – even then her kiss on Sarah’s neck was brief, and she said only, “You’ve a lot of energy today, girl. Come and help me.” And they went together to do battle against the toilet.

Helga and I had one thing in common, and it was one of the things that made me sure that I must work under her, learn from her, rather than from another teacher. Helga and I had the same basic language. Even though our native tongues were different – she born in Germany, I in America – we both had a body language and communicated best through it, trusting it more than words. It was less tricky, more complete. It is more than merely touch: people touch each day and communicate nothing. Body language is the first language – the way the mother speaks to the child long before he can understand her words. As she holds him, bathes him, feeds him, she is telling him of love or anger or irritation. So, too, Helga spoke to her seriously emotionally disturbed children, many of whom had rejected verbal communication, and they listened to this body language. Most of her touching was light and firm and quick. She used it to communicate affection, support, pride in the child; usually she touched the back, shoulders, arm, or head; she used it alone or with a few simple words. She also used another kind of touching. It was really more holding. It said in effect, “I am here. We will survive.” She reacted this way during violence, when a child tried to kick her or bite himself – holding him, restraining him from the destructive act and at the same time comforting him with the solidness of her body. When violence explodes inside a child, all things seem unreal, and the solid strength and warmth of another human being who is not driven away or shattered by it makes the terror more controllable.

Never, however, did she use this body language to express her own anger or irritation. Striking a child may cause him to become fearful of your touch, and this is too valuable a tool to lose, too high a price to pay for momentary frustration. Instead, Helga swore. She cursed as I had never heard a woman do before, and it seemed to harm the children not at all.

If I do not remember when she first addressed me directly, I do remember when she first called me by name.

It was in the spring of that first year, more like summer really although the official date had not arrived. Yellow daffodils had already flooded the hills and fields where we had sailed our kite. Nick, our one male teacher, had put up swings under two of the apple trees, and whenever we could we took the children there in the late morning to play and relax before lunch.

I was pushing Chris on a swing – pushing him from in front instead of from behind so that I could see his face while I played with him. A small game had developed between us: he would straighten and stiffen his legs as the swing approached me, and then laugh out loud as his feet hit my hands and I pushed against them, sending him arcing gently back. Helga had taken the other three children to play some sort of game with Nick’s group. Since Chris was not very good at games, always running, hitting, biting, Helga had stated, “It is a good day for a swing for Chris,” and I had known I was to do this. I loved being with Chris anyway – his very stubbornness fascinated me. Bright as a button, he refused to speak a word; perfectly toilet-trained for months now, he would deliberately pee on the Director’s foot when she brought visitors to our room for “public relations.” She handled it well, though, not even blanching as the brown leather of her shoe turned slowly darker and a puddle formed around it as Chris stood still, looking out the window, smiling, with her hand stroking his head.

In any event, I was totally absorbed in my game with Chris and, thinking we were alone, had even started hamming it up a little as I had with my own children, making funny faces, pretending to be knocked backward when his feet hit my hands. I thought he was beginning to say something: was it “More” – “Mo, mo”? I had not heard footsteps, and was startled when I felt a hand on my arm. I turned quickly. Unexpectedly, Helga was standing beside me.

“Mary,” she said, calling me by name for the first time, “these are for you.” She stretched out her hand toward me and it was full of small wild strawberries. We ate them there together, standing in the sun, sharing the sharp, sweet taste, the grittiness. Since then I have been given many other gifts and some honors, but none has meant more to me than this. Helga had acknowledged me; I was sure then that I could teach.

Chapter 3 (#u810c750e-ba6b-5fb5-b910-f36c64c0d36d)

I worked even harder the remainder of that year with Helga. I canceled my Tuesday bridge and my Thursday afternoon tennis foursome and went three days a week to school rather than two.

From the time Elizabeth and Rick had entered school I had always worked as a volunteer, either at the hospital on the library cart or in the county shelter for adolescents. There was strong tradition in our family for community volunteer and board work, and I had always enjoyed it. But the school was different. I had worked at the hospital and the shelter because it had seemed part of a responsible way of living. I worked now at the school because I loved it and couldn’t stay away.

If I had studied Helga carefully before, I watched her even more closely those last weeks, for she told me suddenly, one day as we walked with the children, that she would not be back the following year.

“Why?” I asked. It seemed impossible to me. I could not imagine Helga without the children or the children without Helga.

“They want me to go back to school,” she said, “An old woman like me. What would they teach me? Ha! What do I need with their fancy courses, their methods-teaching, visual aids, curriculum-planning? They say I will not get my proper salary unless I go to the college and take courses given by some young pup, because our school is about to become approved by the state and I will need the courses for certification. Ach, it is a waste. They can take their shitty courses.

“I know what I am saying, Nick took me to visit the college. The professors either say in fancy language what I already know, or they speak foolishness that is best never heard.”

“Where will you go? What will the children do without you?” I asked.

Helga laughed out loud and put her arm around my shoulders, and I could feel the resiliency of her strong, still-lithe body.

“There are plenty of sick children in the world. Come with me on Saturday and I will show you. As for these, my children here, they will be all right. They are almost ready to go now – and if not, she will hire another to teach them.”

I could not tell whether it was bitterness I heard in Helga’s voice or only disappointment.

On Saturday, Helga picked me up in her ancient coupe and drove me over to her new school; she had met its young director many years before. She led me to the central resource room filled with shelves lined with paper, paints, clay, doll families, puzzles, books, workbooks, textbooks, pencils, blocks, on and on – and outside in the shed beside the building, bicycles, scooters – contrasting to our own meager supplies.

Helga spread her hands. “We are rich!” she said. “Come, come.” Down a long hall, then she threw open a door marked Girls: there in white-tiled glory were five sinks and seven toilets, and Helga flushed each one with satisfaction.

On Memorial Day weekend Helga went bicycling through northern New England with her husband. She was anxious to be gone, and I knew those last weeks of school were very difficult for her. She might say she didn’t mind leaving, but I saw her eyes fill with tears more than once, and her cursing had increased. She decided to add a day and a half to her weekend and asked if I would take charge of her class during that time.

I was pleased to be asked, of course – I was proud that Helga felt that I could teach alone. I knew she cared too much for her children to leave them with anyone she thought incompetent. It was not until much later that I realized that Helga was now consciously teaching me, preparing me, making me grow, just as she did the children. Helga had never taken an education or psychology course, but she was a born teacher, and she knew instinctively when it was time for me to take on more responsibility.

Now, too, I read, researched, balancing what I was reading against Helga’s teaching. Helga had not thought much of education courses, and yet I was greedy for every morsel of information I could find on childhood schizophrenia, autism, the emotionally disturbed. I soon exhausted our local libraries and moved on to the libraries of New York, and bought my own books. Still, amazingly little had been written about these illnesses in children, and many of the authorities disagreed with one another on the cause and range, on diagnosis and prognosis. I wished Helga would write her own book. The others were confusing, contradictory – and yet valuable. So I kept on reading – textbooks, case histories, personal experiences – agreeing, disagreeing, gradually evolving my own beliefs, though these, too, I knew would shift and change as more research was done and my own experience grew.

The term “seriously emotionally disturbed child” covers a wide range, including both the withdrawn, autistic child and the hyperactive, violently acting-out child. Many of the children in our school were diagnosed as being autistic, but the Director preferred the broader term “seriously emotionally disturbed.”

Although there were differing views, gradually a pattern appeared as I read. Various authorities differed on cause and treatment, but most writers and educators seemed to agree on the prime characteristics of the emotionally disturbed child.

First of all, he has a lack of awareness of his own identity. His concept of his own body image is very small. He seldom speaks properly; sometimes he may not speak at all. Certainly this was true at our school; over two thirds of the children had severe language problems.

The seriously emotionally disturbed child resists change, often becomes preoccupied with a particular object, and is filled with excessive anxiety. His emotional relationships with family, peers, and teachers are severely impaired. He does not care; he is turned in upon himself. Although he may appear to be retarded because of these things, still he may often have flashes of brilliance in contrast to the even performance of the retarded child.

The books said this and I believed it: still, it was a conglomerate, whereas to me each child was unique, an individual.

The more I read, the more certain I became of one fact: the screening and certifying of teachers of emotionally disturbed children should not depend solely upon graduation and completion of required courses; the screening should be different for this field. The Helgas of this world must not be lost. The art of communication is just that – an art – and there must be a talent before the craftsmanship can be developed, or you will have only technicians, not gifted teachers. You can instill a hundred techniques in a teacher, have her memorize thousands of technical terms; but if she cannot make contact with the children they are useless.

We said good-bye on the last day of school, Helga and I. We stood on the paint-stained green linoleum of her classroom and I knew I would never see her just so again. I tried to memorize her – the short, thick, straight, graying hair; the horn-rimmed glasses slipping ever closer to the end of her nose as she bent her head nearer, closer, to get a better look; the strong legs above the sneakers. Not young or fashionable or beautiful – merely ageless and phenomenal, like the mountains I had seen in Canada. She had charted a new course, opened a new door, turned a new leaf; there were no right words, only clichés; but Helga had done it for me – and I loved her.

I had wanted to give her a present but I could not think of the right one, and so I went to her now and put my arms around her and out loud could only say, “Thank you, Helga.” But I hope my body language spoke to her.

She held me, too, and we stood like this. Then she moved back a little and took my chin and held it in her hand, smiled, and said, “You will be a good teacher, Mary. Yes. Just watch out for the shitty volunteers.”

Chapter 4 (#u810c750e-ba6b-5fb5-b910-f36c64c0d36d)

In the fall I went back to work at the school again, but it was very different. Not only had Helga left, but most of the staff left with her, having been lured to higher-paying positions. The Director remained, strong, resolute, and for the first time I could imagine her founding the school. She hired a new staff – new psychologists, teachers, psychiatrist, speech therapist.

Besides a new staff, there was also a new location. One of the board members had been instrumental in persuading a church in a nearby town to let the school use its building during the week. It was new and clean and pleasant. There were only two drawbacks: there was no kitchen – all the lunches had to be brought in – and nothing could be left in the classrooms over the weekends; they had to be cleared for Sunday school. Each Friday everything had to be taken down, rolled up, packed away, carried down a long hall to be stored in a back room; then early on Monday mornings the process was reversed.

I was assigned to work with Renée when I went back, and for the first time I learned what bad teaching was. She was young and pretty with teased blond hair; but instead of the happy, confident security I had come to take for granted as the school’s atmosphere, there was a tight, brittle tension in Renée’s room behind what she called “permissiveness.” I watched her narrow hands clench and her voice rise as she refilled the bathtub of water she kept in the center of the room; time and time again the children dumped it over with shrill laughter.

Her theory of permissiveness, she explained, was one that was used with great success in Canada. She felt that all emotional disturbance stemmed from the same source: the fact that the child had never been accepted by his parents. So before he could grow up, he must be allowed to be a baby and do the things he had wanted to do. Renée brought with her pink tin playhouse equipment – stove, refrigerator, sink. I was not quite sure how these fitted into her theory, but I know that my major contribution to her class that fall was the lugging of stove, refrigerator, sink, and bathtub back and forth on Fridays and Mondays.

I was not happy working in that room. All day long the children destroyed things. “They are getting the hate out of their systems,” Renée would say; but if they were, they did not seem any happier for it. They whined and cried and lay on the floor, cold and wet with bath water and urine.

Just before Christmas vacation I spoke to the Director, asking to be transferred to another room. I did not feel knowledgeable enough to be critical – it was possible that this was another way to teach, perhaps a valid way, but it was not for me. And by now my own self-knowledge had grown to the point where I did not wish to pretend. At least not here at school.

There was a great deal of snow that Christmas and our town was white and beautiful. The schools, of course, were closed for the holiday and the house was filled with the noises of my own two children and their friends.

Rick was the oldest, a senior in high school – tall, solidly built, good in both sports and his studies. He was one of those rare children who seemed to have been born happy, well adjusted in his own world, tolerant of others.

Elizabeth was four years younger, and whereas Rick was broad, thick through the shoulders, Elizabeth was slender with black hair, blue eyes; always late, always rushing, eager, stormy, both sensitive and critical – and the most tender and loving of us all. Her Christmas presents expressed her intimate knowledge of us, each gift specific and personal – exactly what each of us had wanted but had not had the time or money or courage to buy.

Larry left early each day for his office in the city, and so I ate a second, long, lazy breakfast with the kids, lingering over the pancakes, a luxury for which there was never time during school. I savored both my coffee and my children, knowing that after breakfast they would be gone into the city for a basketball game or a movie, or else skating at the club with their friends.

Thoughts of the school receded slightly from my mind until one morning just after New Year’s Day when the phone rang. It was the President of the Board of Trustees of the school saying that there was a vacancy on the Board and asking if I would be willing to fill it. I did not really want the position. I had served on too many boards already, gone to too many meetings, voted too many times; but this was the school, and the thought crossed my mind that perhaps this was as far as I would get there, my dreams of teaching too impossible. At least this way I could help build a new school, for our present quarters were only temporary. I watched a brown female cardinal in the pine tree just outside the window beside the telephone, and said, “Yes, I would be delighted to serve.”

I never did, though.

Before that same day ended, the Director of the school called. She said that Joyce, one of the new teachers, had been in a bad automobile accident; her car had skidded out of control and she had slammed head on into a highway divider. The car was a total loss, Joyce’s injuries serious but not permanent. Still, they would take time to heal; she would be in the hospital for six weeks. Could I take her class during that time at substitute’s salary?

The thing I had wanted so badly had happened; the job I had hoped for had been offered to me. So this is how it happens, I thought, no heavenly choir like in the movies, just quietly – a voice on the telephone. I, too, spoke quietly, using mundane language.

“I’ll speak to my family,” I said, “and call you this evening.”

Again I was surprised how small a thing it seemed to them. The kids said merely that they thought it was great. They loved to hear stories of the school and had been over to visit a couple of times.

When I told Larry that I had been asked to teach, he barely looked up from the television set. I lingered uncertainly, feeling in some way that I should warn him that this would change me. I was not sure how, but if the days as a volunteer with Helga had influenced me as much as they had, surely a full-time job would do more. But the commercial came on and he watched even that with concentration.

I called the Director then and asked more questions about Joyce’s class. Which children were in it? What were they like?

Billy, Chris, Louis, and Brad.

I knew none of them except Chris – the same Chris I had pushed on the swing when I was in Helga’s class. I had seen him only once or twice this year because his room was at the opposite end of the building from Renée’s. My head spun – so much to find out, but I couldn’t do it on the phone; no point in holding the Director. I thanked her and asked when it would be possible to come and talk with her.

“Oh, I’ll see you in the morning,” she replied.

“Tomorrow morning?” I asked.

“Yes. Vacation ends today, you know. The children will all be back tomorrow. You will start then.”

Chapter 5 (#u810c750e-ba6b-5fb5-b910-f36c64c0d36d)

I arrived early that first morning, thinking to talk with the Director, to find out about the children in Joyce’s class, to learn their backgrounds, their case histories, the results of their psychological and physical examinations. Even more important was to learn what their routine in school had been, what they were used to, how Joyce handled their problems; the daily lesson plan.

The Director was on the phone when I walked into her office, and I realized that this was my most familiar memory of her, both in this new building and in the old school. As I passed the office I would see her at her desk writing, talking – cigarette and pencil alternating in her right hand, the phone in her left.

She had white hair cut short, pushed back from a small, attractive face, bright brown eyes, and was somewhere between forty and sixty years old. She was cheerful and articulate in her speech; her movements were quick, strong, and spontaneous. She smiled and waved a good morning to me across the phone and cigarette and motioned to me to hang up my coat. I hung my heavy storm coat in the closet in her office, took off my fur-lined gloves and high brown boots, and – in memory of Helga – put on my sneakers. With my sneakers on, I was ready to teach.

The Director’s voice continued on the phone: “You’re right, it’s freezing cold this morning. If he’s coughing you’re wise to keep him home. Mmmmm. Yes. He did? Last night?”

Another ten minutes passed. I was beginning to get restless. In twenty minutes my class would arrive. I didn’t even know their last names.

Finally the phone call ended and the Director smiled at me. “I’m so glad you were able to come, Mary. How about a cup of coffee? First thing I do every morning when I get here is to plug in the pot.” From the shelf behind her desk she produced two cups and poured coffee for each of us.

“Could you tell me a little about the children in Joyce’s class?” I asked.

“Well, there are four boys … oh, excuse me, the phone. Oh, dear, I forgot to make a note that Jeff won’t be in; I must remember to tell Dan. Lots of calls on these cold mornings …”

And she was gone again. The phone rang four more times. There was a minor crisis when the woman who was scheduled to bring the casserole lunch for the children called to say that she herself was sick and couldn’t get out.

“Don’t worry. You take care of yourself now. Thanks for calling. Oh – yes. Yes. Certainly. No problem at all. Get well in a hurry now.” Cheeriness continued to flow out of the Director’s voice over the haze of cigarette smoke.

As soon as she was off the phone she was putting on her coat. “I’m going to have to dash over to the store and then back home for a minute to pick up the hot plate. The woman from the church who was supposed to bring lunch is sick, or so she says, so we’ll have to heat up some soup. Tell Zoe to handle the phone till I get back; she’ll be in in a minute. Oh, and I’ll see you at Circle with your class.” She emphasized the last two words and smiled.

“Mrs. Fleming …” I said.

“No, no. Call me Doris. Here now – here are the folders on the children …” She rummaged in a green file cabinet behind her desk. “Let’s see now – Chris, you remember him. From Helga’s class. Brad, he’s a doll. Where’s Billy’s – ah – here it is. And let’s see. Who else is there? Oh, yes, Louis. Mmmmm. Can’t find his at the moment. Oh, well, it’s not important. These will give you a start.”

She left then, leaving me holding the pale manila folders in my hand.

At the front door she turned back. “Don’t worry. Everything will be fine.”

I had wished for information, not cheery platitudes, and yet I had a small glimpse of the courage of the woman who had somehow not only founded the school but kept it together through many desperate times when money had been nonexistent and her own personal life rocked with the tragedy of her husband’s death. Perhaps she had found it necessary to ignore certain needs in order to be able to cope with bigger problems – perhaps cheeriness was the mask she wore.

Nonetheless, I shivered in my red jumper as I followed her out the door, calling, “Which is my room. Which door?”

“Oh, my. I forgot that, didn’t I? Well, you can’t remember everything. Especially on these cold mornings. The last one in the back is Joyce’s. Yours, I mean.”

I went back inside with a sinking heart. How could I have been so presumptuous as to think I could handle all this? It was one thing under Helga’s direction. But alone? I knew the Director scarcely at all. Helga had always referred to her by title or as “they,” which I had taken to signify authority. Now I wondered. She had left without introducing me to the children, without giving me any idea of the day’s routine.

Well, I decided, I would go down to the classroom and look at the folders. Perhaps I could at least learn how to recognize Brad from Louis.

The room was L-shaped, painted green. There were two high windows on the north wall so that the room was light enough, but cold and wintry. There was a large wooden jungle gym in one corner, a small white bookcase which held a few Golden books, and two Maxwell House coffee cans with wooden beads, strings, pegs, and missing puzzle pieces. There were three wooden puzzles and a peg board. Beside the bookcase was a small wooden chest that held some blocks, a doll with a missing head, a small, soiled blanket, and half a dozen clean diapers. There was also a jumping-jack rocking horse and a small pink table with chairs. A complete inventory. It had taken me less than three minutes to make it. Helga’s materials were sparse, but they were four times this. I looked again at the chest and bookshelves – could I teach four children with just these odds and ends?

There were coat hooks along one wall, though, and these at least looked familiar – until I saw that there were more than a dozen and they were labeled with names like Susan and Diane. Obviously names from the Sunday school class. Where did Joyce’s boys hang their coats? On nameless hooks or under someone else’s name?

Slam! The door of the room slammed shut so hard the glass in the window of the door rattled. A tall, dark man stood inside the door leaning against it, holding a small boy by the arm. It was Chris; I could not mistake those gray eyes – but if he recognized me he gave no sign of it.

“I’m Chris’s father,” the man said. “Will you tell his teacher he’s here?”

Chris twisted his body away from his father, trying to loosen his arm, pulling at the doorknob, trying to get the door open, to get out.

And I think, What is this? I have known this child before – he was always difficult, disruptive, but he never fought school before. What is this now?

Out loud I say, “Joyce isn’t in today. I’m Mary MacCracken, the substitute teacher.”

His eyes travel over me. “Well … good luck,” he says. Then: “Look, could you just hold the door while I get out, then I can hold it closed from the other side till you can slip the bolt?”

For the first time I see a brass sliding bolt near the top of the door, and something inside of me is outraged. I may be new, I may be inexperienced, but I do not need to lock my children in a room to keep them there.

I smile at the man, still not knowing his last name, and say, “That’s all right. You just go on ahead. Thank you for bringing Chris,” and I see my brave, foolish words reflected in his gray eyes that are much like Chris’s.

I knelt on the floor beside Chris and put my arm around his waist. The father, in one swift movement, was out the door, holding it closed from the outside, peering in through the window.

Chris gave a tremendous lurch, trying to reach freedom, but my hand fastened on his belt and I held on, even as I toppled over and spread flat against the floor.

Damn that window, I thought, knowing that the father was watching – but I held on tight. It was important, what we were doing right then. We were establishing our code, our modus operandi, in this our first meeting and confrontation; our standards were being set. I would not lock the door. I knew if I locked it that first morning, it would be necessary to lock it each successive morning and afternoon – every time any of us went in or out. I did not want that. I wanted eventually to develop free access.

I did not think all this as I lay there on the floor: I just did not want to lock the door, and so I held on tight and said again softly, “Good morning, Chris. I’m glad to see you.”

I inched my way across the floor, never looking up, until I had my back against the door. Then I let go of Chris’s belt. He tore at the knob and rattled the door. I braced my feet on the tile floor and leaned my full weight against the door. At least, I thought, the man must be gone by now.

Chris stopped shaking the door and stood looking at me. Did he remember those times a year ago in Helga’s class? I thought I saw a flicker in the huge gray eyes, but I could not be sure.

“Hiya, Chris,” I say from the floor.

Momentarily he smiles, but it is so swift a smile that it ends long before it reaches his eyes. He moves back away from the door and for one long minute we look at each other – full, complete eye contact.

Then deliberately he takes off his coat and throws it on the floor. Is this what he always does and why there is no need for his name above a coat hook – or is he merely testing me?

I get up from the floor. “Hang it up, Chris.”

He laughs and runs and so I go and get him. There is no point in calling to him: he will not come and I want to make words meaningful, and so I go and get him a red crayon. There is no time to find labels and make neat lettering.

I lead him to the coat hooks and point to the hook farthest on the right.

“This is yours,” I tell him. “This is where you will hang your coat.”

He does not pull away from me now but stands silently as I write CHRIS in large red-crayon letters on the wall above the hook. Defacing church property? So be it.

“Get your coat, Chris. Hang it here.”

Wrong. He laughs and runs again.

I go and get him once again and we go together to the center of the room where his discarded coat lies on the floor and I take his hand and guide it to the coat – but he will not pick it up and instead slumps slack and boneless to the floor, laughing his shrill laugh.

I prop him up, my hand closes over his, and we take the coat and hang it on the hook beneath his name.

“Good for you,” I say.

But there is a tapping at the door and he does not even seem to hear me now. Instead, he finds two drumsticks in the wooden chest and takes them and climbs up on the jungle gym in the corner of the room, climbs until he reaches the highest platform – and there he folds his legs beneath him, and his mind inside him and his gray eyes look blankly down.

You are so small, I think. Seven years, and you cannot weigh more than fifty pounds. Your eyes seem bigger than the rest of you; they dominate your small, square face like diffuse gray clouds covering a sky … But I have watched and I have seen you be aware; I remember when your eyes would clear, lit from behind – and I will have more of this.

I go to the door to investigate the tapping. A stout woman is there, holding a large, curly-haired boy in her arms.

“Miss MacCracken?” Her speech is cultured, almost

English in articulation. “I understand that you will be filling in for Joyce. A tragic thing. Tragic. For her as well as for our poor children. Well, there’s nothing to do but make the best of it.”

She comes into the room, where Chris is beating a tattoo on the highest platform of the jungle gym, and stands the boy on the floor, takes off his red bonnet and mittens; then lays him on the floor and takes off his white shoes so that she can get the red snow-suit over his feet – unzips his overalls and feels inside his rubber pants.

“Oh, dear. He’s wet again. Never mind, I’ll fix it.” And she changes him there on the floor.

Then she rises and hands me the plastic bag of diapers, first removing two baby bottles full of milk, complete with rubber nipples.

“I’ll put these in the refrigerator for you, although I must say I don’t think much of that refrigerator. It must be at least five years old – not even a separate freezer so the poor children can have ice cream. Still, we mustn’t complain, must we? Now, the baby food is in the bag. It will be all right until you open the jars; then be sure to refrigerate it. Poor girl. It must be difficult for you to get the hang of things. Well, you can always call me. I’m never far from Bradford if he needs me.”

She kisses him then and calls to Chris, “Good morning, Christopher. Have fun with Bradford.”

She addresses me: “My, Christopher is athletic, isn’t he? Climbing way up there. Well, each of us has our own strengths. And the boys Christopher and Bradford do have such a marvelous time together.”

She left then before I could speak. Which was perhaps just as well. The only thing I could think to do was to look at Brad’s folder; perhaps I would regain some semblance of reality.

There it was. Brad. Bradford Turner. I checked the birth date. He was six years old.

My God, I thought, what kind of a class is this?

I was to find out later that this was the most difficult class I would ever teach, the hardest, the lowest-functioning. Four untoilet-trained boys, three of whom were nonverbal, ranging in age from five to eight. But I was unschooled – and while I knew it was somewhat different from Helga’s class, in my naïveté I thought, “Well, at least it’s a challenge. In a way, I’m lucky – there’s no way to go but up.”

Then in my mind’s ear I heard Helga’s voice, “You sound like a shitty Pollyanna. Get to work.” And I laughed out loud.

Louis was brought in by one of the women drivers and I recognized him immediately. If his name was not familiar to me, his blue football helmet was, and I remembered hearing the staff psychiatrist discussing him in Renée’s room. There was discussion as to whether he should be placed in her room for the remaining days. This would be his last year at the school; he was having multiple seizures now, sometimes as many as four or five in one hour. While it was never stated in words, most of us were sure these were epileptic in nature.

There was nothing much to do for Louis now except make sure his small football helmet was securely fastened to protect his head, should he fall beyond reach, and to cover him until he woke again after an attack. He was staying on at the school only until his parents could find a suitable residential setting for him. Some of the staff thought that it was wrong to keep him on in a school designed for the emotionally disturbed – wrong for him and an imposition on the teachers who had not been trained, and did not want to give the kind of custodial care Louis needed. But the Director wanted him there.

His parents had been strong supporters of the school, grateful and willing helpers, and the Director felt a loyalty and a responsibility to help them now. And right or wrong, if the Director wanted him there, he stayed. So the problem had been temporarily resolved by moving Louis from Renée’s room to Joyce’s. Joyce was more tolerant, her room more removed, and Louis’s unnamed but ever-increasing seizures were less noticeable and distracting to the other children and teachers …

Louis’s driver hands me his bib and an extra set of clothing and says, “Had a seizure on the way over. Went stiff – then right out – but he came to soon enough. Seems all right now.”

I take off his hat and coat and he climbs upon the jumping-jack rocking horse and starts the motion that he will keep up all day unless he is lifted off – up and down, up and down – the springs beneath him groaning under the weight of his eight-year-old body. Saliva runs down his chin and I wipe it with the first of many Kleenexes and say, “Good morning, Louis,” but his blue eyes do not focus and the motion does not stop – up and down, up and down. I wonder if there is such a thing as mental masturbation.

Someone crashes against the door and I open it to Tom, the boy who ran down the stairs so many eons ago when I was first searching for Helga’s classroom. Tom is a tall, frail boy with wispy black hair falling across his eyes. All his shirts and sweaters have turtlenecks, which he unfolds and pulls up over his chin and eyes whenever a situation grows too threatening.

Tom has a bell in one hand; the other is behind his back. He emerges from the turtleneck, clangs the bell, and shouts, “Circle time!”

“Thank you,” I answer. “Good morning, Tom.”

“Good morning, Tom,” he replies, and leaves us.

Circle time. The formal day at the school began with Circle each morning. It was the only time during the day when the Director observed all of us closely and noted the relationship between child and teacher, teacher and teacher, and improvements and lapses in each child. At the beginning of Circle we all sang to each child, singling him out, making him special, and on Wednesday afternoons at staff meetings there would be references to how the child acted. Group singing followed the individual greeting, and then the galloping and skating exercises and other games, which the Director said were designed for “gross motor development.” These were followed by more social, nursery-school-type games where the children chose partners and again the Director watched for “peer relationships.”

It was a warm and friendly time. Most teachers had aides assigned to them and the aides arrived as Circle began, so that the ratio of child to adult was two to one.

And now it is time, the first time, for me to take my own class to Circle. But so far there are only three children. Where is my other one? Billy. Well, perhaps his was one of the phone calls; perhaps the weather or a cold has kept him home.

I survey my three: Chris on the top of the jungle gym, Brad sitting placidly on the floor bulging like a Buddha because of his many diapers, Louis up-and-downing it on the rocking horse. How do I gather these three and get them down the long hall to the room where Circle is held?

I stand beside the jungle gym. “Circle time, Chris. Let’s go.”

He spreads himself flat and laughs his silver laugh. I climb seven rungs until I can reach the platform, and then lift his slack body down beside me. How can he be so heavy when he is so small? But at least he does not seem inclined to run, and lets me hold his hand. With the other hand I disentangle Louis from the rocking horse and support him against my side. Now Brad – how to get him there? Lacking alternatives, I simply say once again, “Circle time, Brad. Come on now.” And surprisingly he stirs. He rocks forward until he can push against the floor with his hands, pushes himself up to a standing position, and then he willingly waddles to me and holds my skirt – and we are off down the hall toward Circle.

The others are already there. Twelve more children; quite a few must be absent because I know there are twenty-four children in the school, and five other teachers, one for every four children. They call across the room, introducing themselves to me – Susan, small and blond; Renée; Carolyn, tall, black-haired, beautiful; Ruth, red-haired with glasses; and Dan, a new male teacher replacing Nick, blue eyes, strong-looking in a khaki shirt. The Director smiles from in front of the piano and I maneuver my three to the small chairs in the Circle. The Director motions to a woman on the side of the room who comes and sits next to Louis and so I put Brad and Chris on either side of me.

The singing starts, all the teachers and some of the children joining voices – the Director plays the piano, leading us.

“Good morning to you,

Good morning to you,

Good morning, dear Louis,

We’re glad to see you.”

I reach across Brad and touch Louis’s shoulder as we sing to him – the blue eyes are marbles, and the woman beside him wipes his chin.

We sing to Brad and I smile down at him and take his pudgy hand and touch his bulging stomach with it, and he beams up at me – brown curls, rosy cheeks, brown eyes, a beautiful child, but how can he manage to look only two years old when he is six? No time to think now. It’s Chris’s turn. He decides that he must leave his chair and sit on me – he winds his arm tight, tight, around my neck. From across the room it must look as though he’s hugging me affectionately, and the teachers smile approvingly at this sign of rapport. Only I can feel his sharp fingernails as he pinches the skin below my ear, pinches hard, and I lift him back to his chair and my hand holds him there as we finish the song … “Good morning, dear Chris, I’m glad to see you.”

I soon saw why there had been no lesson plan. There was no one to do lessons. Nor was there time. The day was consumed with eating and eliminating. Circle took approximately forty-five minutes; when it was over, the classes went to the bathroom. My class changed its diapers. The Director told me this as the other children left the room and I nodded, still filing away the picture of that morning’s Circle in my mind. It had not changed much since the first day I visited: although some of the children were different, they were still beautiful; although Helga was no longer there, the strength and the loving were.

As we made our slow trek back to our classroom, we passed the furnace room where Zoe, chief cook and bottle washer, secretary, public relations expert, and the Director’s right hand, was beginning to heat a frozen casserole in the electric warming cart.

We were just rounding the corner, Chris and Louis holding my hands, Brad waddling behind, when I heard Zoe say, “Jesus, cut that out, Franklin!”

“Aw, come on, Zoe, one quick one. I never did it in a furnace room, did you?”

That must be that new teacher, I thought, Dan Franklin. Zoe called everybody by their last name.

“Go on, get out now. Quit kidding around.” But there was laughter behind her voice.

“Okay. All right. I’ll catch you later then. Incidentally, who’s the new teacher with Joyce’s class? Where’d she come from!”

“Came from the Junior League. One of the volunteers.”

“The Junior League? You’re kidding? Jeez! Well, Zoe, I’ll bet ‘Junior League’ doesn’t last a week. I’ll lay a meatball on it.”

“Okay, you’re on, Franklin. She’s better than you think. I saw her work with Helga last year.”

Billy was my fourth child. He was the youngest in the class, just five, with blond, wavy hair and a soft, unformed face with a rosy, puckered mouth and, like the others, not toilet trained. His mother was young, separated from her husband, and she would bring Billy to school an hour or so late each morning. The Director spoke to her about this, then Dr. Steinmetz, the psychologist, finally Vic Marino, our psychiatrist, each explaining how important the schedule, the routine, was for Billy, how necessary the regular scheduling … and she would agree – and then the next morning come as late as usual – or later – dark, bruised hollows beneath her eyes.

It was hard not knowing what happened to the children when they left school. They did not speak, and so there was no way to learn from them.

Helga had been sure some of them were physically abused, and told me of visiting one family unannounced and finding the boy chained to a doghouse in the high-fenced backyard, his food and water on the ground.

But if some parents were cruel, others were kind and devoted, making unbelievable sacrifices for the special child within their home. Schizophrenic children are classically poor sleepers, refusing to go to bed, haunted by nightmares; and often the parents slept in shifts, keeping watch over the child who controlled their home. This schedule slowly eliminated sexual relations or even friendship between the parents. The children could be tyrants, and their houses could become filled with the hate common to tyranny.

To me the amazing thing was that the parents managed as well as they did – and that any teacher or outsider would presume to judge them. After all, we worked with the children five hours each day, from nine-thirty in the morning until two-thirty in the afternoon; but the parents were with them the other nineteen hours without relief as they tried to care for their children and accomplish other chores as well. I felt compassion and admiration for their courage, and I often longed to reach out and put my arms around them as well as the children – not so much to care for them as to say what I could not put into words. I was not sure that I would have been as strong as they, had a child such as this been born to us. For more and more it seemed to me that there must be a chemical imbalance in at least some of these children – and who could say which ones?

But my job was not research. While I might hope for answers from the laboratories, still there was this day, this hour, when answers had not yet been found and my own job was teaching. I believed then and I believe still in the day school for emotionally disturbed children. There are valid reasons and occasions for residential settings, but whenever possible I believe the child is better at home with his parents. However, if the child is to go home to these parents each afternoon, then parent and teacher must try to work together.

And this was often difficult. To begin with, many of these parents had been hurt so often, lied to so much, accused of so many things, that their own defenses were high – or their own hopes had been abandoned and they had settled into what was easiest.

With Brad, for example, it was difficult for his mother to agree to leave the baby bottles and diapers home; and it was an important day for both of us when she brought me six pairs of white cotton training pants for him as a gift.

For I had set my goals. I was not a psychiatrist or even a trained teacher yet, but I was a mother and I had raised my own children. It seemed to me that if in those weeks while Joyce was absent I could teach the children to take care of their bodily needs – eat, go to the bathroom by themselves, dress themselves – and to communicate a little, I would have helped.

Zoe told me later how impossible my goals were – but because I was new, alone in my room at the far end of the hall, and had no one to tell me otherwise, I did not know it.

And so I bought five small plastic glasses and began. Each day after Circle we sat at the pink table and drank juice and ate cookies. At first they tipped over the glasses, dumped the juice upon the floor, threw the cookies; but they liked the sweet apple juice and the soft sugar cookies, and I would not let them have them unless they sat with me at the table. I wanted them to get the feeling of having a place where they felt safe. I knew no better way than to feed them there.

We also stripped. There alone in our bare classroom I took off their clothes. Not Louis – even I knew that he had left us, was now beyond reaching. But I took off the clothes of the other three piece by piece and taught them to put them back on by themselves. For a half hour or more each morning we worked on learning to get dressed and undressed. I took off three pairs of shoes, three pairs of jeans, three pairs of diapers. I laid out three pairs of cotton training pants – one on Brad’s chair, one on Billy’s, one on Chris’s. I worked with whichever one I could capture first, sitting him on the floor in front of his chair, guiding his hand to the underpants, then pushing him forward, laying the pants out on the floor in front of him, then bending first the right leg, aiming the right foot for the proper hole, then the left leg.

Standing him up, I’d hook his thumbs beneath the elastic at the top of the underpants and pull them up, and then, finally, I’d release the child and capture another and begin again.

And somehow, it did not seem like drudgery. I was, after all, in bodily contact with the child the whole time, touching him, helping him learn. And I knew, without really knowing it, that this touching was my own best way of communicating with these children. There are other ways for other people, but I could almost hear the children through my fingertips, and I think I also spoke to them.

That was all I asked for in the beginning, just the underpants. But I did not set our table or pour the juice until all the underpants were on.

For Chris, this was merely relearning. I had seen him put on and take off his own jacket, even his shoes, dozens of times in Helga’s classroom. I knew he had not “regressed”; there was too much intelligence in his laughter, in his willful disobedience. It was a matter of getting through again.

Brad learned to manage both underpants and jeans – he could not get past his stomach to his shoes and socks.

Billy was much slower, finally able to pull on his underpants with help. I never got as far as taking off his shirt.

I was happy and totally absorbed. I loved being on my own with the children; they were making progress, I was sure of it – and now I understood Helga’s reaction to having volunteers. I was glad the Director did not visit my room, grateful that no volunteer or aide had been assigned to us – just the children and myself. Without interference of adult words in the room, I could hear the unspoken words of the children – their rage, their refusals, their protests, their pleas, their questions, compliance, or excitement.

I stopped taking the class to the lunchroom for the noon meal. There they had been allowed to eat what they liked, Chris roaming around, snatching food from other plates. It was not that the school or Joyce was lax: I felt then and I still feel that of all the schools I’ve seen – and there have been quite a few now – ours was one of the finest. It was not that they were lax; it was that these four children of Joyce’s were so difficult. They were in many ways more like small animals – some wild, some tame – than like human children. Because the other children in the school were more advanced, though perhaps as sick in their own way, the other teachers were more tolerant of these four. Asking less, making fewer demands.

But I did not want this. If I accepted it, or allowed the children to, it meant that I did not believe they could improve; and if this was so then we were without hope. And it was necessary to hope; more than necessary – it was essential. On this I built my own new creed. I believed in the children.