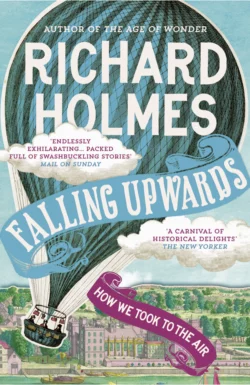

Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air

Richard Holmes

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1488.11 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘Nominally a history of the hot air balloon, Falling Upwards is really a history of hope and fantasy—and the quixotic characters who disobeyed that most fundamental laws of physics and gave humans flight.’ —The New Republic, Best Books of 2013CHOSEN AS BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR IN ** Guardian ** New Statesman ** Daily Telegraph ** New Republic ****TIME Magazine 10 Top Nonfiction Books of 2013** **The New Republic Best Books of 2013** **Kirkus Best Books of the Year (2013)*From ambitious scientists rising above the clouds to test the air, to brave generals floating over enemy lines to watch troop movements, this wonderful book offers a seamless fusion of history, art, science, biography and the metaphysics of flight. It is a masterly portrait of human endeavour, recklessness, vision and hope.In this heart-lifting book, Richard Holmes, author of the best-selling The Age of Wonder, follows the daring and enigmatic men and women who risked their lives to take to the air (or fall into the sky). Why they did it, what their contemporaries thought of them, and how their flights revealed the secrets of our planet is a compelling adventure that only Holmes could tell.It is not a conventional history of ballooning. In a sense it is not really about balloons at all. It is about what balloons gave rise to. It is about the spirit of discovery itself and the extraordinary human drama it produces.From the dramatic and exhilarating early Anglo-French balloon rivalries, the crazy firework flights of the beautiful Sophie Blanchard, the long-distance voyages of the American entrepreneur John Wise and French photographer Felix Nadar to the balloons used to observe the horrors of modern battle during the Civil War (including a flight taken by George Armstrong Custer); the legendary tale of at least sixty-seven manned balloons that escaped from Paris (the first successful civilian airlift in history) during the Prussian siege of 1870-71; the high-altitude exploits of James Glaisher who rose seven miles above the earth without oxygen, helping to establish the new science of meteorology; and how Mary Shelley, Edgar Allan Poe, and Jules Verne felt the imaginative impact of flight and allowed it to soar in their work.