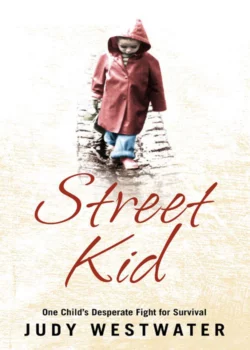

Street Kid: One Child’s Desperate Fight for Survival

Judy Westwater

Wanda Carter

John Peel's programme Home Truths first brought Judy's moving childhood story to light – Abducted by her psychotic spiritualist father and kept like a dog in the backyard, brutalised at the hands of nuns in a Manchester orphanage, and left to live wild on the streets. But Judy survived and today has founded 7 children's centres in South Africa.John Peel first brought Judy's moving childhood story to light on ‘Home Truths’. Abducted by her psychotic spiritualist father and kept like a dog in the backyard, she went on to suffer at the brutal hands of nuns in a Manchester orphanage, before living wild on the streets. An incredible, heart-wrenching story of a child who refused to give up.After a childhood lived in terror, in 1994 Judy was presented with an Unsung Heroes Award for her charity work with street children in South Africa. Her moving story came to light after Judy was interviewed by John Peel on BBC’s ‘Home Truths’. ‘Street Kid’ is the inspirational and heartwrenching story of her early years.At age two, in postwar Manchester, Judy was snatched from her mother and sisters by her psychotic father – a spiritualist preacher. He kept her in his backyard, leaving her to scavenge from bins to beat off starvation. At four, she was sent to an inhumanely strict catholic orphanage, before being put back in her father’s cruel care. For the next three years she was treated as a virtual slave.After being taken by her father to South Africa, Judy ran away to join the circus where she found her first taste of freedom and friendship – before her father tracked her down. Weeks later Judy was alone again and living on the streets, too terrified to turn to her circus friends. For 9 months 12-year-old Judy made her home in a shed behind a bottle store before collapsing in a shop doorway from near-starvation.Finally, aged 17, Judy managed to pay her way back to England to find her mother and sisters. But her return to Manchester cruelly shattered any dreams of a happy reunion.Determined that her childhood experiences should in some way give meaning to her life, Judy has worked tirelessly to help children in need back in South Africa in the very place she had been treated to such abuse herself. She has opened 7 centres to date.

Street Kid

One Child’s Desperate Fight for Survival

JUDY WESTWATER

With Wanda Carter

FOR MY TREASURED FAMILY

My beloved children Jude, David, Carrie and Erin

and all my beautiful grandchildren

Contents

Cover (#ub2cf2b83-4958-55a6-9149-d98f4ed97747)

Title Page (#u76f2c377-427e-56f2-b7a7-4a50f94c0460)

Chapter One (#u4ddd3726-1612-5173-8843-efec61f8f124)

Chapter Two (#u740e4090-befb-5b17-b451-accc12877cda)

Chapter Three (#u25880017-d3f5-5a83-a097-3a6176bd74f4)

Chapter Four (#u9b171ddb-1ab6-5904-91f9-2f39ab04f8e2)

Chapter Five (#u0536616c-31b5-5736-b50c-b419e0a571cf)

Chapter Six (#u30166adc-4bc7-517e-a3b4-e89bfa78f87d)

Chapter Seven (#u8e26e190-d480-53f8-bd5f-acef6945999d)

Chapter Eight (#u3c11c171-6702-57a2-82db-d484aa43619f)

Chapter Nine (#uf2cc8e7e-bfdc-5822-a3f2-264398e2e746)

Chapter Ten (#u93f0050e-c2ae-5e85-960a-d9d882a5454e)

Chapter Eleven (#ubdfd8c9b-f382-56b9-ae08-400cd7119307)

Chapter Twelve (#u6be4b0b4-9126-5a56-9fdb-904b02b67578)

Chapter Thirteen (#u797fc2a9-11e5-5ae1-b28a-ce1883f8259f)

Chapter Fourteen (#uf55506dd-31d4-5b42-b6b8-7c1ade2ad570)

Chapter Fifteen (#u3d7fbc64-81bd-5ced-9a86-85ac47a3f34e)

Chapter Sixteen (#u221d21d8-cad7-5270-bd93-530aab7d7ef9)

Chapter Seventeen (#u3725c824-869a-54ef-bd23-f8c7ff1038ed)

Chapter Eighteen (#u82944b67-f347-5927-8005-de4c69abd854)

Chapter Nineteen (#ue8068a44-6242-59a3-a581-0e0d8ec520f7)

Chapter Twenty (#u6b1b9276-34af-5693-a454-c2855cbf93a8)

Chapter Twenty-one (#u1aeea85f-13b4-598b-8b29-0b07c6261261)

Chapter Twenty-two (#u0233cf1e-98f6-5c4f-8cd3-baa4367a65ee)

Chapter Twenty-three (#u4d985b08-7205-57e9-bf39-dcaee972c91e)

Chapter Twenty-four (#ud26f5a03-b9ac-5510-9e89-9fe16fb8a8bb)

Chapter Twenty-five (#ue7fccc66-ae29-5951-8bc2-6981db604066)

Acknowledgements (#uc6d5ec92-46cb-5d83-a345-74fee4abfc6f)

About the Author (#uf373994a-d4b1-5684-8246-63ed648e5504)

Pegasus Children’s Trust (#uea8cd66c-3abf-5f78-ad90-9882370c82a3)

One Child by Torey Hayden (#u64d28436-ebcf-5506-aea0-2eb33b725689)

The Little Prisoner by Jane Elliott (#ud952913f-c3a9-5ba5-91a6-e8215e0e64a3)

Hannah’s Gift by Maria Housden (#u4f1659b2-1c37-5edf-8c47-a018703707c2)

The Choice by Bernadette Bohan (#ud4a04a99-977f-506e-8ff6-6fe9ed78cd8a)

Copyright (#uf0161848-d5af-5222-8dbc-693e7aaebbb9)

About the Publisher (#ud61184b2-270a-5909-b849-9020f48a8d1f)

Chapter One (#ulink_2e9aae00-5f8f-518c-83f1-823b639c823b)

Was two when Mum and Dad deserted us, leaving Mary, Dora, and me alone in the house for seven weeks without food, light or coal for the fire.

I was born in Cheshire in 1945 and although the war had ended that year, it had been a battleground in our house whenever my parents were together. When my dad wasn’t working in a factory he was dressed up in a herringbone tweed suit preaching at local spiritualist church gatherings. It was only when my mother married him that she realised what a nasty piece of work he really was but she still managed to have three kids with Dad before she decided she’d be better off with her Irish boyfriend, Paddy.

When Mum ran off she took with her our identity cards and allowance books. She must have thought that my father would see to it that Mary, Dora and I were fed and clothed but all he did when he realised he was saddled with us was ask our next door neighbour, Mrs Herring, to look in on us every so often and check we were okay. He said he’d be back the next weekend but he didn’t keep his promise.

So that was how the three of us came to be left in the house alone.

Mary was seven, and the oldest. I reckon that as soon as I was born, I knew better than to cry for my mother: it was always Mary who’d looked after me and Dora. Mrs Herring looked in on us now and then, letting us have whatever scraps she could spare; but it was Mary that kept us going. She must have longed for a mother’s care herself, especially when she had to go to school in such a terrible state. All the teachers were appalled that she was so dirty, and they’d often have her up in front of all the class to tell her off.

One day it got so bad for Mary that she dragged our tin bath into the living room, put it in front of the fireplace, and started filling it with cold water. She pulled me up from the hearth, where I was eating ashes, and said, ‘Come on, we’ve got to get you dressed. We’ve got to go and look for Mummy.’

We went out and made our way to the market, which wasn’t far from our house. It was cold; my feet were bare; and all the clothes hanging from the stalls were flapping in my face. I kept looking through them to see if I could see my mother.

And Mary kept saying, ‘Look for Mummy.’

After seven weeks, Mrs Herring was at the end of her tether. She had only meant to look out for us for a few days. She must have thought, ‘Where the heck is their father?’ Maybe Dad sent her messages saying he’d be back in a week or something. But the weeks went by and we were in a terrible state. In those days, times were tough but people looked out for each other, and I’m sure Mrs Herring just thought she was doing her best. But at some point she must have realized she had to do something or we’d get really sick. A bitter winter was setting in and we had no money for coal or food. When I touched my hair, I could feel it was all matted and crusty, and my body was covered in weeping sores that hurt when I lay down.

Mrs Herring contacted the welfare people, who managed to track down my father and served him with a summons. Dad suggested to them that he find someone to look after us in exchange for free lodging at our house, and they agreed with the plan. A homeless couple of drifters called the Epplestones came forward, and the welfare board was satisfied. In the years after the war they could barely keep up with the rising tide of poverty and need, so once our case was closed they didn’t bother their heads about us again.

After five months my mother returned home, pregnant and penniless. My dad allowed her back in the house on the understanding that she didn’t see Paddy again and had her baby adopted. She agreed.

I don’t remember being glad Mum was back or anything like that. You only feel glad or relieved if you have something to compare it with but life with her had always been pretty awful for us. Still, it was better than being in the care of Mrs Epplestone who’d hated having to look after us and shouted a lot. Most of the time, Mary, Dora and I had sat huddled like mice on the old brown couch in the living room, with its springs poking through the cover. But it was when it came to mealtimes that the horror really began. Bowls of porridge were banged down in front of us and when I couldn’t eat the nasty, slimy, lumpy stuff, Mrs Epplestone would yank my head back by the hair and force the spoon down my throat until I couldn’t breathe. When I choked and gagged she’d hit me across the face.

Mum had no intention of giving up her baby when it arrived and when my Dad discovered that she was keeping her he was furious and came straight over to the house. It was a frosty New Year’s Day and Paddy was round, warming himself in front of the fire. He must have come in for a quick one with my mother and to see the new baby. They both got a big shock when the door opened and there was my father. When he walked in and saw them playing happy families, and Paddy’s trousers over the chair – in his house – all hell broke loose. The men tore into each other like dogs. My mother was screaming like a banshee, and they were hammering into each other with their fists and breaking up the furniture.

Paddy was a big fellow, much larger than my father, and he’d been a boxer in the army, so he soon got the upper hand. Dad stood there, all bloody with his chest heaving, knowing he’d been beaten and yet burning up with fury and wanting to kill them both. Mum and Paddy looked back at him, confident now that my father had been beaten. My mum told him that they were keeping the baby and that there was nothing he could do about it.

Being told he couldn’t do anything made my dad determined to show that he was still boss in his own house. He strode across the room to where we were huddled, boiling with anger, and grabbed me. I hid my face against Mary’s chest and clung to her. She and Dora held on tight, screaming at him, ‘Leave her alone! Leave her alone!’ But they only managed to hang on to me for a few seconds before he peeled their arms away.

I don’t think I made much of a sound, but I can still hear Mary and Dora screaming my name as my father dragged me down the street. I can remember my legs not being able to touch the ground: they were just batting the air as Dad took great big strides to get away from the house. I didn’t know where we were going or what was going to happen. I’d just seen him fighting Paddy and was terrified that it might be my turn next. I don’t know how far I was dragged but it seemed like a long way. I didn’t have a coat and felt colder than I’d ever been in my life.

I’d never been separated from my sisters before. The trauma of having been left on our own at such an early age had made us terrified of leaving each other’s sides. At night we’d always slept in one bed and during the day we moved about the house like silent triplets or sat on the sofa wrapped in each other’s arms. I think we were frightened one of us might disappear. And now I had.

When we arrived at my father’s place there was a dark-haired woman sitting at the table. Her face was rigid and, although she didn’t say anything, I sensed that she was shocked. I wasn’t really aware of much that first evening as I was almost catatonic with fear, but in the days that followed, I realised from the way she treated me that this sharp-faced woman hated me.

Her name was Freda and she’d left her husband and child for my father. He had promised her the moon and now he here he was, walking in with a two-year-old child in tow and telling her that she had to look after me. It wasn’t surprising she was bitter. All her dreams of starting a new life in their own little love nest, just the two of them, were shattered in that moment.

Things were only to get worse for Freda. The spiritualist union were tipped off by her husband that she was living in sin with one of their preachers, a man who had deserted his wife and three kids and the scandal was soon splashed over the local papers. My dad and Freda were effectively run out of town and we wandered homeless for weeks. No one wanted anything to do with an adulteress who had left her baby.

Finally, we had a lucky break. A friend of Freda’s knew an old couple who needed caretakers for their shop in Patricroft, an old mill town near Manchester. When we went into the shop I thought we’d gone in to buy something. It smelt of sugar and biscuits, and I saw meringues on a shelf by the door. There were newspapers, jars of sweets and cakes, and my stomach gave a rumble as we walked through to the back of the shop. When my father introduced us to the lady behind the counter, she led us through the door behind her and down some stone steps to a room at the back.

Gertie and George Roberts, the owners of the shop, interviewed my dad in the living room of the flat that was to become our home. It had a fireplace and a back door that led out into the yard, a table under the window, a sink in a sort of cubicle, and a tiny two-ring stove.

I’d been cleaned up a bit before the interview, but I expect I must still have looked a sight. My dad was on his best behaviour and laid it on pretty thick, acting the loving family man, trying hard but down on his luck.

‘This is my wife, Freda, and that’s Judy, our daughter.’ I sat on my stool quietly, hearing his lies but not reacting, knowing I’d be severely punished later if I did.

‘You see, I was made redundant from the factory and since then we’ve been struggling to get by.’ His shoulders slumped dramatically.

‘Oh dear me, you poor things. I know it’s been bad for so many just now.’ Gertie’s face was creased with pity and concern.

‘The thing is, I’ve been trying to do my best for them, but it’s been really hard and we’ve got nowhere to go.’

George looked at his wife and cleared his throat. ‘Well, we’d like to help you and you seem like good folk. I know Gertie would agree with me that we’d like the job to go to a family who really needs it.’

‘We’re hard workers,’ said Dad, ‘and we’ll do well for you, I promise you that. We never dreamed we’d be lucky enough to find a job and a roof over our heads too.’

I really felt I had a home now, all because of Auntie Gertie and Uncle George. Uncle George looked like Father Christmas – fat, with a white beard and huge rosy cheeks. He used to sit in the chair while Auntie Gertie helped Freda, and I’d stand against his knees by the fire, happy to be feeling so comfy. I don’t think he spoke much to me, but I liked it that way.

Auntie Gertie was a big-boned woman who looked rather dour; but she was the gentlest person – never aggressive in any way – and had arms that sort of snuggled you. She also helped Freda a lot in the first weeks. I used to watch her mixing the ice-cream by the door of the shop. She gave me a meringue while I sat there with her, which I ate in little bites. She also took us down the steps into the cellar, where she showed Freda how to use the plunger for the washing and the mangle to wring the water out of the wet clothes.

I still missed my sisters terribly and thought of them a lot, especially before I went to sleep at night. I lay on an old settee in the box room upstairs, wondering if they were thinking about me too, and whether Mary wanted to put her arms around me as much as I longed for her to hold me safe and warm.

After the first couple of weeks, once Freda had got the hang of things, Uncle George and Auntie Gertie hardly came round any more. When their dog, Jessie, died they were completely heartbroken and, without the excuse of a walk, didn’t leave their house much. When George and Gertie were around, Freda minded her behaviour and acted the dutiful wife and mother. But now she had the place to herself, things really began to change.

My dad soon got a job in a linen factory, where they made handkerchiefs and eiderdowns. He worked nights as a security guard and slept during the day. I don’t think I ever saw him, unless it was a Sunday. Freda shut me out in the yard as soon as the papers were delivered to the shop in the morning, so I never saw my father come in. And because he was never around, Freda could be as vicious to me as she liked.

In the box room where I slept, there were stacks of boxes all round, making it difficult to get undressed. I didn’t have pyjamas or a nightdress, so I wore my vest in bed and covered myself with a blanket to keep warm. In the morning, as soon as I heard Freda coming out of her room, I would get up and put on my dress and cardigan and go downstairs.

One morning, I came down to find Freda waiting for me. The paperboy had just arrived and she grabbed my arm impatiently and took me to the back door.

Pushing me roughly outside she said, ‘Sit there. I don’t want you moving.’ She pointed to a spot on the paving in the middle of the yard, gave me a vicious little nudge so that I almost fell down the steps, then went back inside.

I walked over to the spot she’d pointed at and sat down. There was nothing to be seen but enclosing grey walls, and a bucket standing against the door of the outdoor toilet. I sat on the cold paving stones wondering when Freda was going to let me in. I remained there for an hour or so, scared to move in case I’d be punished. I remember putting my finger in a crack between the paving stones and moving it along the tiny strip of sand. Then I traced the outline of one of the stones, then another beside it. It wasn’t a very interesting game, but I made it last for a long time.

I’d been told to stay put, but, as I wasn’t wearing any tights or socks, the cold began to get to me. I needed to move about to keep warm, so I stood up and went over to the steps, looking nervously at the back door. I was curious to see what was over the dividing wall, so I climbed up the steps to look into the next yard. I saw it was almost the same as ours, except for a few plants.

I then tried jumping down the steps, one at a time, then climbing up again. I did this at least twenty times, then got bored of it and sat down and looked at the sky. I watched it for ages. I saw the smoke coming out of the chimneys and the patterns it made, and the pigeons on the roofs, hopping about and sitting hunched up in pairs by the chimney pots.

It was several cold hours before Freda opened the back door.

‘Get in,’ she said.

She didn’t even look at me. It was as if she was letting in the dog.

‘Have your tea, then get out of my sight.’ She pushed a cheese triangle across the table at me.

Afterwards, I went and sat under the table, which was where I always hid when Freda was around. It had a long cloth, so no one could see I was there. I stayed quiet as a mouse until it was time to go up to bed.

After that, Freda shut me outside in the yard every day. The first time it rained, I ran to the back door and tried to get in, but it was locked. I hadn’t known until then that Freda actually locked the door. By the time I’d made it to the privy I was soaked through. I had to shelter in the toilet most of the afternoon, which smelt damp and mouldy, like the cupboard under the sink, and I felt I’d never get warm again.

One day, when it was just starting to spit with rain, our neighbour, Mrs Craddock came out of her house and looked over the wall.

‘All by yourself, chicken?’ She tutted and cooed, coaxing me over. I approached her cautiously. Mrs Craddock had rollers in her hair and was wearing a flowery pink overall, stretched tight across her enormous bosom.

‘Come inside and keep warm.’ She scooped me up, lifted me over the dividing wall and put me down in her yard. I saw she was wearing brown tweed slippers with pompoms on them.

‘Let’s get you warmed up then.’

She took me by the hand, led me indoors, and sat me down on the sofa by a big fireguard that had washing hanging over it. I was very frightened. I’d been told to stay in the yard.

Mrs Craddock stood at the window watching for Freda, hands on hips, and as soon as she saw her get off the bus she opened the front door. I tried to slip past her but she pushed me back, tucking me behind her, protectively.

I was panicking badly now. I’m going to be in big trouble. Freda’s going to go mad.

But Mrs Craddock was puffed up with rage and nothing was going to stop her now. She didn’t pause to think that I’d be the one getting hurt at the end of it.

‘Oi Freda! What do you bloody think you’re doing leaving this child in the yard? It was raining for Christ’s sake!’

‘What the hell’s she doing there? Give her back here! And you can take your fat nose out of my bloody business.’ Freda’s face looked sharp and pointy as a knife and I thought she was going to go for Mrs Craddock.

‘You stupid cow! I don’t know how you can stand there. People like you should never be allowed to have kids!’

They went at it hammer and tongs, watched by some of the women from neighbouring houses. Finally, Freda grabbed me and took me with her, slamming the door behind her. She dragged me through the shop and down the steps into the room at the back. I thought she’d beat me senseless, but instead she gave me a couple of slaps and sent me to bed. I think the row with Mrs Craddock had exhausted her. Mrs Craddock never took me in again. But from then on, other people began looking out for me, and occasionally they threw toys over the wall.

One day, there was a thunderstorm and I was feeling frightened. A girl came running over to me. She wasn’t wearing a coat and was getting drenched. She looked about eight or nine and had ringlets, which the rain had plastered against her head.

‘My mum said to come and fetch you.’

She lifted me over the wall and we ran, hand in hand, through the sheets of rain to her house. Her mum was waiting at the door.

‘You poor little thing. You come in and get dry.’ She led me into the kitchen and dried me with a towel, fussing over me as she did so.

‘I’ll make you a cup of cocoa. That’ll warm you up. What’s your name, poppet?’ She was talking to me soothingly as she put some milk and water on the hob.

‘Judy,’ I whispered.

‘And how old are you?’

‘Three and a half.’

‘Now poppet, I think you’ll get warmer if you come into the living room and sit by the fire.’ She led the way to the other room, where her two daughters and husband were sitting.

‘Tony, this is Judy. She got all wet in the storm,’ she said.

‘Hello young lady. How would you like to come sit by the fire with me and help me win the pools?’ With that, he scooped me onto his knee and let me help him pick out the winning teams with a pin on his football coupon.

It was the first time I’d ever got a glimpse of what family life could be. I bathed in the warmth of it.

Chapter Two (#ulink_e962aafc-cb82-59a4-8098-c853e96989a7)

Freda never gave me anything to eat or drink in the mornings. Whenever I got thirsty, I’d scoop water from the toilet; but there was nothing I could do to calm the gnawing hunger I felt every day.

It wasn’t long before I made my escape from the yard. One day I stood on tiptoe to reach the bolt on the back gate. I pulled on it with all my strength and when it slid back it cut my hand. But it didn’t matter to me that it was bleeding because I’d got out. The only worry I had was that now I’d opened the door, I couldn’t close it from the other side. But a second later I managed to slip the toe of my sandal underneath and closed it. I felt very proud of myself.

On the other side of the gate I was faced with a high stone wall with a path running along in front of it leading to a small green square with rows of houses backing onto it. As I stood there on the grass, a boy came up to me. He must have been about twelve.

‘You alright? Are you lost or something?’ I didn’t answer, didn’t run away either. I just stood there. Then he went away.

From time to time I noticed women coming out of their back doors carrying bags of rubbish over to the low, open-topped bins at each corner of the square. My tummy hurt from hunger and so, as soon as the women were gone, I went over to one of the bins, stood on a brick, and leaned in to hunt for scraps.

The smell was almost overpowering, but I delved down into the damp and greasy rubbish, rummaging through it looking for something edible. I found a promising looking newspaper parcel and unfolded it. Inside there was a handful of potato peelings and some chicken bones. I picked up a bone and sucked on it, tearing off a few tiny strands of meat with my teeth. It tasted good, but didn’t satisfy my hunger one bit, so I started on the peelings. They didn’t taste nice at all. After eating as many of them as I could stomach, I leaned further over the bin and dug down deeper, looking for other newspaper parcels. I spotted one, and pulled it loose. It contained an old crust of bread and some bacon rind, which I eagerly devoured.

That first time I ventured out of the yard, I didn’t go any further than the square behind our houses, but it wasn’t long before I was exploring the rest of the neighbourhood. I wandered down the gutters and cobbled alleyways that ran between the rows and rows of back-to-back brick houses. None of them had front gardens or yards and, without a flowerbed or patch of grass to bring colour to the streets, Patricroft was a monotonous place of grey stone and sooty brick. The only things that brought colour to the place were the barges which shipped their cargo along the old canal. I’d stand on the iron bridge and watch them for hours as they made their slow progress through the tar-coloured water, littered with bottles and other bits of rubbish. If anyone came towards me I’d run away and hide.

One day, about three months after we’d moved to Patricroft, and soon after I’d first escaped from the yard, I walked past a gate, through which I could see some grass. Thinking it must be the entrance to a park, I pushed open the gate and went in. I found myself in a large garden, with beds of beautiful flowers planted in patterns. I’d never seen anything so wonderful in my life, and wandered through the garden in the sunshine, hardly aware of time.

After a while, I thought I’d better go home – it must have been mid-afternoon at least, and I was always careful to get back to the yard in good time. But when I looked for the gate I couldn’t find it. I began to wander further and then started to panic. I skirted the big, grey stone wall of the building in the centre of the garden, thinking that if I went round it I might find my way back to where I started. Then, as I came round the corner, I was met by a curious sight.

Groups of children in grey uniforms were playing on the grass in little groups. Moving about amongst them was the strangest looking person I’d ever seen. She was wearing a long black dress that flapped as she floated along the grass, and her hair was completely covered with black cloth too. She was gliding along as if on motorized wheels. It was my first sight of a nun.

I watched for about ten minutes, and then a loud clanging noise almost had me jumping out of my skin. One minute it had been quiet and peaceful, the next a huge bell was ringing right above my head. I crouched by the big stone steps, frozen in terror and certain that it was telling everybody where I was. I thought I might have stood on something and set it off.

My fear grew even worse when the groups of children starting coming towards me. They came over to the steps and lined up in pairs. I was crouching down between a shrub and the side of the steps, watching the children as they went up, hand in hand. About ten pairs went by without seeing me, but then I must have made some little movement. My eyes met those of a little girl. It was clear she’d spotted me: she began to tug on the nun’s sleeve and said something to her while looking back at me. Then the nun turned and glided over, her big black dress flapping as she came.

‘What are you doing here? What is your name?’ I knew my name but I couldn’t say it. I couldn’t speak to her.

‘Come with me.’ I couldn’t move. When someone said ‘Come with me’ it always meant only one thing. I was certain the nun was going to beat me for being in her garden.

She took my hand and beckoned to the little girl who’d seen me. ‘Josephine, I’d like you to take her to the kitchen.’ Her tone of voice wasn’t particularly warm, but at least I wasn’t getting beaten yet.

The girl took my hand and we both went up the steps together. It felt like I was entering a huge mouth as we went through the great doorway. I’m going to get swallowed, I thought to myself. We walked through the hall, which smelled of polish, to an enormous kitchen with a long scrubbed wood table in the middle. The only things that brought brightness and colour to the stark room were the copper pans hanging on the walls. Everything else had a sober black and white formality, and even the older girls who were preparing food on tables around the sides of the room in their white dresses looked austere. I was told to sit down and one of the girls brought me a slice of bread and jam, which I devoured hastily, despite my apprehension.

The woman in black came in and began asking me questions again.

‘Where do you live? Just tell me your name.’

I looked at her, still unable to speak.

She was huffing and puffing, quite irritated now. She left the room but returned a few minutes later with a group of girls and boys.

‘Do any of you know this girl? Have you seen her before?’ No one answered.

The nun appeared even more exasperated and turned back to me.

‘Come on, we’d better go and see if we can find where you live.’

She took my hand and we went out of the kitchen, back through the hall and out into the sunshine again. We went through a different gate to the one I’d come in by. It was bigger and led onto the main road, with the canal opposite. I told the nun that I knew where we were and made to go; but, to my horror, she kept hold of my hand and began to march me up the street towards the door of the shop.

But I can’t go in the front! Don’t take me in that way! The panic was rising in a swift tide and washing over me. Don’t take me in that way! I’m supposed to be in the yard!

The bell tinkled as the nun pushed open the shop door. Freda was looking over from the counter at the back.

‘Is this your child?’

Freda said that I was and thanked her very sweetly for bringing me back. Then, as soon as the nun had left, she took me into the back room and closed the dividing door.

‘Don’t you ever dare go out again.’ she screamed. ‘Never, ever come in the front, and never ever leave the yard. Do you hear what I’m saying? I’m going to tell your father when he gets back.’

Then she began to lay into me, punching and kicking. She boxed my ears, which she’d done before, only this time the pain was more excruciating. It felt like sharp daggers in my head. I heard a pop and a horrible kind of rushing sound. Freda stopped hitting me and stood, breathing quickly, hands on hips, glaring down at me.

‘Get up to your room,’ she hissed. ‘I don’t know why I bother to look after you. You disgust me.’

It was only after I’d got upstairs and crawled under the blanket that I realized I was completely deaf in my right ear.

The next morning Freda recovered her energy and as soon as I’d crept downstairs, heading for my hiding place under the table, she grabbed me and began shouting at me again, calling me a little piece of vermin. She hadn’t told my father: I knew she wouldn’t, because she would only have got in trouble herself. If he was crossed, he could get extremely vicious; a cold brutality came over him which even Freda, who usually gave as good as she got, was scared of. My dad was always paranoid that someone would pry into his business. He’d come up against the welfare board before, and he didn’t want anyone poking their nose into his life now.

Freda grabbed me by the hair and threw me at the back door. She then opened the door and gave me a kick, which sent me tumbling down the steps. I gashed one of my knees against the step, and when I picked myself up at the bottom of the steps I couldn’t put any weight on it at first, it was so painful. Then I looked down and saw blood trickling down my leg. I gave a little whimper, but not because of the pain. My dress had got blood on it from the gash and I was suddenly sick to my stomach with terror, knowing that Freda would punish me for getting it dirty. I’d already been beaten by her for losing my bobble hat, and I knew that she’d seize any excuse to beat me.

I hobbled gingerly across the yard to the outside toilet, where I took a square of newspaper from the bundle that hung from a piece of string. Dipping it in the toilet pan, I tried desperately to scrub the blood off my dress with the sodden paper until my arm was shaking, but the blood wouldn’t come off.

When Freda let me in later, she looked at my tear-stained face and I knew it made her want to beat the hell out of me. When she saw the state of my dress, stained with blood and spotted with little bits of newspaper, she snatched up the cheese triangle that was sitting on the table and said, ‘Right, for that you won’t be having any tea, my girl.’ As I hadn’t been out of the yard that day, I hadn’t managed to scavenge anything from the bins, so I was sent to bed with hunger pains gnawing at my insides.

It was only two days later that I once again fell foul of Freda in a big way. It was a sunny day and I was playing in the yard, walking carefully on tiptoe from bar to bar of the iron grate that covered the cellar window. All of a sudden, I slipped and fell, saving myself with my arm. However, my foot had fallen between two of the bars and my leg was dangling in the gap between grate and window. When I tried to pull it out, my knee was in the way; so I tugged and tugged at it, trying to yank it free, becoming more and more panicked that Freda would find me wedged there later when she opened the door. But I couldn’t see how I was going to free myself. I was totally trapped and unable to work out why my knee wasn’t able to slip back through the way it had gone in. After several minutes of frenzied pulling, my knee got past the bars, but then I found out that my foot in its sandal couldn’t get through. I struggled with it until finally my foot came free, but by then my shoe had come off and fallen through the bars.

My leg was cut and bruised and very sore, but I was more worried about my sandal, which was lying below the iron grate, about three feet down. I knew I’d get into terrible trouble if I didn’t get it back, so I lay down on the grate and stretched my right arm through the bars. My fingertips didn’t even nearly touch it, but I wasn’t about to give up. Come on, you can reach it. Come on! I couldn’t bear to think about what Freda would do if she found I’d lost a shoe. So, again and again, I ground the side of my face down onto the bars in a frenzied attempt to reach my sandal.

When at last I stood up and looked down at my bare foot, I realized that my dress had got dirty from lying on the ground. There was nothing more I could do, so I went over and sat on the steps, where I remained for the next two hours, stiff with fear and awaiting my fate.

When I heard Freda unlock the door, I tried to creep in without catching her eye, but she saw the state of me at once.

‘What the hell have you been doing, and where’s your shoe?’

I just stared back at her, too terrified to say anything.

She grabbed my arm, pinching it viciously. ‘You answer me, damn it! Where’s your bloody shoe?’

She yanked my arm and pulled me outside and down the steps. I pointed at the iron grate.

‘You little swine. Didn’t I tell you not to move? What the hell were you doing throwing your shoe down there?’ She poked my forehead with a finger, jabbing it at me so hard my neck snapped back.

Then she went back inside and a minute later I heard her trying to open the cellar window. It was stuck. A moment later, she returned.

‘Right, Missie, you lie down and get it!’

I tried to tell her it was no use my trying, but she wasn’t listening.

She pushed me down and forced my arm between the bars, though she could see perfectly well that it wasn’t nearly long enough to reach the sandal. She put her foot down on my shoulder and pushed. The bars were crushing my chest, making it impossible to breathe.

After a while she dragged me back inside and looked around the room for something long enough to reach the shoe. Finally she stood on a chair, took down the curtain rod, and unhooked the curtain from it. ‘Don’t you dare move!’ she said, taking the rod outside.

A couple of minutes later she came back with the shoe in her left hand. In her right, she held the rod. She whacked me hard across the face with the shoe, making me reel back with the shock of it.

‘Get upstairs, damn you,’ she snarled. Her eyes were dark slits in her white face.

But as I turned to scramble up the stairs and out of her way, she went for me with the rod, savagely beating the back of my legs. I crumpled to the floor and continued up the stairs on my hands and knees. I felt her black snake-eyes on my back as I turned the corner to my room.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/judy-westwater/street-kid-one-child-s-desperate-fight-for-survival/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Judy Westwater и Wanda Carter

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Семейная психология

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 736.08 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 18.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: John Peel′s programme Home Truths first brought Judy′s moving childhood story to light – Abducted by her psychotic spiritualist father and kept like a dog in the backyard, brutalised at the hands of nuns in a Manchester orphanage, and left to live wild on the streets. But Judy survived and today has founded 7 children′s centres in South Africa.John Peel first brought Judy′s moving childhood story to light on ‘Home Truths’. Abducted by her psychotic spiritualist father and kept like a dog in the backyard, she went on to suffer at the brutal hands of nuns in a Manchester orphanage, before living wild on the streets. An incredible, heart-wrenching story of a child who refused to give up.After a childhood lived in terror, in 1994 Judy was presented with an Unsung Heroes Award for her charity work with street children in South Africa. Her moving story came to light after Judy was interviewed by John Peel on BBC’s ‘Home Truths’. ‘Street Kid’ is the inspirational and heartwrenching story of her early years.At age two, in postwar Manchester, Judy was snatched from her mother and sisters by her psychotic father – a spiritualist preacher. He kept her in his backyard, leaving her to scavenge from bins to beat off starvation. At four, she was sent to an inhumanely strict catholic orphanage, before being put back in her father’s cruel care. For the next three years she was treated as a virtual slave.After being taken by her father to South Africa, Judy ran away to join the circus where she found her first taste of freedom and friendship – before her father tracked her down. Weeks later Judy was alone again and living on the streets, too terrified to turn to her circus friends. For 9 months 12-year-old Judy made her home in a shed behind a bottle store before collapsing in a shop doorway from near-starvation.Finally, aged 17, Judy managed to pay her way back to England to find her mother and sisters. But her return to Manchester cruelly shattered any dreams of a happy reunion.Determined that her childhood experiences should in some way give meaning to her life, Judy has worked tirelessly to help children in need back in South Africa in the very place she had been treated to such abuse herself. She has opened 7 centres to date.