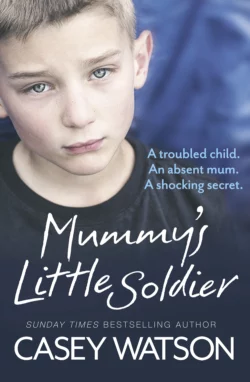

Mummy’s Little Soldier: A troubled child. An absent mum. A shocking secret.

Casey Watson

Casey’s Unit is, as ever, full of troubled, disaffected pupils, and new arrival Leo is something of a conundrum.Thirteen year old Leo isn’t a bad lad – in fact, he’s generally polite and helpful, but he’s in danger of permanent exclusion for repeatedly absconding and unauthorised absences. Despite letters being sent home regularly, his mother never turns up for any appointments, and when the school calls home she always seems to have an excuse.Though Casey has her hands full, she offers to intervene for a while, to try get Leo engaged in learning again and remaining in school. The head’s sceptical though and warns her that this is Leo’s very last chance. But Casey’s determined, because there’s something about Leo that makes her want to fight his corner, and get to the bottom of whatever it is that compels this enigmatic boy to keep running away. With Leo so resolutely tight-lipped and secretive, Casey knows that if she’s going to keep this child in education, she’s going to have to get to the bottom of it herself…

(#u3d9ea8c9-bead-55f7-b9f7-a8162c54e9ad)

Copyright (#u3d9ea8c9-bead-55f7-b9f7-a8162c54e9ad)

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the author’s experiences. In order to protect privacy, names, identifying characteristics, dialogue and details have been changed or reconstructed.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperElement 2016

FIRST EDITION

© Casey Watson 2016

A catalogue record of this book is

available from the British Library

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Cover photograph © Rebecca Nelson/Arcangel Images (posed by model)

Casey Watson asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780007595143

Ebook Edition © May 2016 ISBN: 9780007595150

Version: 2016-02-16

Contents

Cover (#u19323335-1034-58e9-b4a3-ba172e2aad7b)

Title Page (#ulink_8cef1359-d3a8-5982-9137-a9a638f3e4dc)

Copyright (#ulink_f2b7c681-cdc5-5bd3-b44e-3c8106aafac5)

Dedication (#ulink_9ba2dd08-9048-513e-b8d0-13415e06afce)

Acknowledgements (#ulink_f1072a9f-96ff-5a20-b4aa-8745d5aec092)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_ccb4103e-1f56-5c91-bd00-d4dcb7270d75)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_7493c3d4-6e51-5254-b9ca-a594aa629526)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_8214b7eb-b1fe-5ccc-9f41-c3d926ebc5dc)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_68e25958-53fe-5a25-9959-8b5180cea670)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_ff0a9abc-a4da-587c-9b70-73ab0e08639a)

Chapter 6 (#ulink_3565c778-c6bb-5fbe-a450-61358ca2f341)

Chapter 7 (#ulink_42be4dd7-c1c2-57e9-a1aa-688502dd772f)

Chapter 8 (#ulink_ddd6e2cc-7085-5123-b06c-c5daf51af64c)

Chapter 9 (#ulink_c64dcc88-3dc6-589a-a26b-aeefe1e3a1bd)

Chapter 10 (#ulink_9af9a918-a5fa-5594-b3a0-8892d1ad2479)

Chapter 11 (#ulink_7982e4af-6fb9-5759-b9e9-c1b2a4caf457)

Chapter 12 (#ulink_5cd05ea5-992e-5b8b-8edd-c55b73dde21b)

Chapter 13 (#ulink_c30437a6-de5f-56ae-89c3-a4c14eeff3a8)

Chapter 14 (#ulink_bd54da97-4f59-5a8c-9934-e74ffa7ef3c0)

Chapter 15 (#ulink_eae32598-a48c-5f72-8865-53dc4b2c95df)

Chapter 16 (#ulink_241c5b91-884c-5a3a-9e08-6c285189dd17)

Chapter 17 (#ulink_baa641c9-cf3b-55c3-a1c8-05e845ec269c)

Chapter 18 (#ulink_d65fcd78-a5cd-5fd7-a0e1-989f5bf7cf56)

Chapter 19 (#ulink_1e3b20a0-c43f-5401-9aed-373f368a7336)

Chapter 20 (#ulink_e88ecc47-54cf-59ef-b525-4e06e43c1c74)

Chapter 21 (#ulink_7b88c656-049d-5c6b-be0f-a22c85595227)

Chapter 22 (#ulink_6ac98d59-f124-5822-81a8-15a38cc6019b)

Chapter 23 (#ulink_d088172d-9bba-5137-927c-ebbf3f564243)

Chapter 24 (#ulink_bb84fa2b-b39f-5bab-8e23-7964f163b5eb)

Chapter 25 (#ulink_95fdb361-2dc0-5bfc-9074-4585a6bec42e)

Epilogue (#ulink_61591a97-1be5-50ab-80aa-580ca3a3903d)

Topics for reading-group discussion (#ulink_05f9950c-b2cd-54ca-9e14-f0742463bad8)

Casey Watson (#u22d6a8f4-02f5-592e-b10c-3a712575c6bc)

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter (#ufda1f861-4d5b-531f-bc9c-49f30f6cae7d)

About the Publisher (#u5e02c397-5bf4-54a3-a615-d0ae4a39b6fb)

Dedication (#u3d9ea8c9-bead-55f7-b9f7-a8162c54e9ad)

I’d like to dedicate this book to all those brave soldiers, men and women, who continue to dedicate their lives to serving their country so that all our grandchildren, mine included, can look forward to a peaceful future. A special mention goes to the parents and grandparents of serving soldiers, airmen and seamen, who will surely be facing their own private battles, as well as being filled with pride. Bless you all.

Acknowledgements (#u3d9ea8c9-bead-55f7-b9f7-a8162c54e9ad)

As ever, I’d like to thank the team I’m so privileged to work with. Huge thanks to everyone at HarperCollins, my agent Andrew Lownie and, of course, my lovely friend Lynne.

Chapter 1 (#u3d9ea8c9-bead-55f7-b9f7-a8162c54e9ad)

Working in a school, or so my thoughts ran, I should really love words, shouldn’t I? Words are good, after all. Words are a brilliant way of communicating with one another. Words are one of the best ways invented for expressing how we feel. But as I looked down at the word that had appeared on the screen of my mobile, I could think of a fair few more I shouldn’t even be thinking, much less typing out furiously in response to it.

The word that had been texted was ‘whatever’. Which was to be expected, as it was the word that was my daughter’s current favourite, in reply to pretty much anything I said. Except she spelt it ‘whateva!’ Which was another thing.

I’d had the last word that morning, which had been no kind of victory, because when you’re a mum and you start the day by having words with your teenage children, you spend the rest of it feeling miserable, even if you’re in the right. Which I was, about that one thing she’d promised to do but ‘couldn’t’, but that didn’t make me feel any better.

And now the text, just to rub it in. Just to make her point. I flipped the phone shut, shoved it into my bag and headed into school. Better not to answer it. Not just yet.

Also better to put it behind me and focus on work. Everyone has one of those days sometimes, after all. But there are some days that you really don’t want to be one of those days, aren’t there? The first day of term being one of them.

Which would have been the case anyway – first days of term tend to be complicated at the best of times – but it seemed that today I wasn’t even going to be allowed the luxury of licking my wounds a bit while easing into it.

‘Ah, Casey!’ Julia Styles called, marching down the corridor towards me, bristling with efficiency and thick manila files. ‘Brilliant. You’ve saved me a journey.’

Julia Styles was the school SENCO, or special educational needs co-ordinator, and it was her job to oversee everything special needs-related. It was also her job, in conjunction with the other relevant senior staff, to act as gatekeeper of where I worked – the school’s behavioural unit.

‘I have?’ I asked her, as we reached each other, wondering why she’d been in search of me anyway. The first day of a new term usually involved me heading to her office, for a sit down and a chat about my latest bunch of pupils, as well as a catch-up about the holidays over a mug of coffee or two.

But not today, it seemed. Julia linked an arm through mine and swivelled me around. ‘We’re off to a meeting in the meeting room,’ she explained, leading me back the way I’d come. ‘All a bit last minute, I know, but I decided we all needed to put our heads together. Donald’s already up there. Gary’s coming, obviously. I’ve sent Kelly off to hunt Jim down as well.’

Donald was the deputy head, Gary the school’s child protection officer and Jim was my alter ego; we both did similar jobs. We had the same job title, too – the rather fierce-sounding ‘behaviour manager’. Even though neither of us was very fierce at all. Kelly Vickers, who’d just gone off to find him, was one of the twenty or so teaching assistants in the school, and was these days pretty much my number 2.

‘Quite a gathering, then,’ I said, as Julia and I mounted the stairs up to the room in question. ‘What’s brought all this on? Something happened?’

‘Oh, don’t look so worried,’ Julia reassured me. ‘Nothing bad’s happened. Well, not yet, anyway.’ She grinned. ‘No, you know what it’s like, Casey. I just had one of those eureka moments. As you do. No, we’ve got a couple of potentially rather complicated children joining the school today, and since they’re the sort of kids who are going to require input from all of us I thought “I know! How about I take the bull by the horns and get all of us together, then?” So I did! Seemed to make a great deal more sense than trying to organise half a dozen separate meetings on the hoof, as usually happens. Means we’ll all be on the same page before we start working with them, won’t it?’ She pushed the door to the meeting room open and smiled again. ‘I believe it’s called “joined-up thinking”. Something jargon-y like that, anyway. Ah, Gary, Donald. Hi. You got my notes, then. Thanks so much for coming.’ She threw her files down on the big table that dominated the space. ‘Quite the party, eh? Ah, and here are Kelly and Jim. So that’s almost all of us. Who’s brought the bubbly?’

That’s another thing about the first day of term, particularly when it’s the first term of the academic year as well. For those of us who work in schools, it’s a bit like the first day of January. The ‘happy new year’ we’ve all anticipated over the long summer break. Some with an element of dread (or so I’m told; that never applied to me personally), and some with a degree of manic energy and enthusiasm that would have everyone else wondering what they’d slipped into their cornflakes.

And that was all to the good, because if you didn’t start the school year full of optimism and energy, there was a fair chance you’d be burnt out by Christmas. ‘Come and sit by me,’ Gary Clark said, pulling out the chair beside him around the other side of the table. ‘Come join me in the naughty corner so we can whisper and pass each other secret notes.’

I slung my bag down on the seat next to him, gratefully spying the kettle and jar of instant on the desk on the corner. ‘Need a coffee first,’ I told him. ‘Can I get you one as well?’

Gary shook his head. ‘Coffee?’ he asked, nodding pointedly in Julia’s direction. ‘No way. I want a slug of whatever she’s having.’

That’s the thing about those sorts of days as well, isn’t it? That they always seem to have an infinite capacity to get worse. Though once we were gathered around the table, that was the last thing on my mind, because Julia went straight to work on her short but important agenda so that we could be finished before the children started ‘hunting us down’.

Her terminology wasn’t far off the mark, either. While mainstream school went about its business, most of the people currently in the meeting room were a hard-to-pin down sort of bunch, because that was the nature of the roles we all played. While the head, Mike Moore, oversaw his flock from the calm, tidy-to-within-an-inch-of-its-life environs of his huge office, Donald Brabbiner was invariably fire-fighting somewhere or other, while Julia and Gary, likewise, were out of their offices almost as much as they were in them. Jim Dawson, too, had a peripatetic schedule, his job being similar to mine, but also quite different, in that he roamed the school, also firefighting where needed, but mostly monitoring those kids who might, for whatever reason, need to be pulled out of lessons and come to me for a spell.

In fact, I was the only one in the room who stayed pretty much where I was most days – in the little ground-floor room that had been both my classroom and my office since I’d begun working at the school. Which meant I was easier to find, yes, but also that I was something of a magnet for all the kids who, strictly speaking, weren’t my responsibility any more, and who I regularly had to shoo back to their lessons.

Right now, however, ex-Unit kids were the only kind of kids I had, my last bunch having finished their stint with me at the end of the previous summer term, most to go back to mainstream lessons, one because she was done with school now, and one, rather distressingly, because her life had imploded and she was now in foster care a long way away. Her name was Kiara and she’d been on my mind a lot over the summer. I wondered how she was doing and hoped she was okay.

But today, as was the way of things, it seemed I was about to have my classroom repopulated – by three new kids, two of whom were new to the school as well. ‘And they’ve come with quite a hefty amount of baggage,’ Julia explained, opening the first of the files in front of her. ‘Which is why it seemed sensible for us to get our heads together before they get here.’

She began with a boy by the name of Darryl. Darryl, being eleven, was coming to us from his primary school, which was obviously a big transition in itself. But in Darryl’s case it was a little more complicated. He struggled academically, on account of having some learning difficulties, but also socially, because he had Asperger’s syndrome, which is a mild form of autism.

I knew something about this, because my own son, Kieron, had Asperger’s, so this was familiar territory. But there are degrees of difficulty faced by kids with Asperger’s and it sounded as if Darryl struggled more than Kieron – it seemed he was coming to us after a particularly fraught final year in primary, during which his behaviour and mood had gone markedly downhill.

‘He’s been badly bullied, by all accounts,’ Julia explained, not needing to glance at her notes, having doubtless already memorised the contents. ‘And he stresses about everything: crowded corridors, people touching him, loud noises, altercations …’

‘All of which he’s going to find in spade-loads here,’ Gary pointed out.

‘Exactly,’ Julia said. ‘He struggles with eye contact too. And he’s also developed several compulsions in the past couple of years apparently, which is going to make him a magnet for bullies here, from the outset. He has this thing about hair. Likes to touch it – needs to touch it – and not his own, either. Any hair in reach, according to what his former SENCOs passed on. It’s a self-soothing thing he needs to do when he’s anxious. You’ll have come across that sort of thing before, Casey, yes?’ I nodded. ‘Which, again, is going to mark him out and make life even more stressful for him. Which is why I thought – assuming you all agree, of course –’ she looked around the table – ‘he should start off splitting his time between learning support and the Unit, at least till he’s found his feet and his anxiety levels lessen. I was hoping you’d be able to work on his social skills, Casey.’

The kettle had boiled by this time so, having agreed, I went off to make a couple of teas and coffees; if an army marches on its stomach, a school definitely seems to run on its bladder – at least via the frequent application of hot drinks. Didn’t matter if it was blowing a gale or, like it was today, still positively summery; the soundtrack of any room in school that the children weren’t actually in was the click of switches, the ting of teaspoons and the shouts of ‘Who’s for a brew?’ Oh, and the accompanying rustle of various biscuit packets being opened.

By the time I’d returned to the table, Julia had opened the second of her folders of notes, this one markedly fatter. ‘Cody Allen,’ she said. ‘Thirteen. So she’s going into year 9, and I think she’s going to need a good bit of support.’ She then glanced at Donald, who nodded. ‘Julia’s right,’ he said. ‘I’ve already met her. And had a meeting with her new foster carers yesterday.’

This made me prick my ears up. ‘She’s just gone into foster care?’ I asked, thinking immediately of Kiara, and just how painful a business it had been, however necessary, for her to be dragged away from everything she knew.

But Donald shook his head. ‘Not “just”,’ he said. ‘She’s been in care since she was four, by all accounts. Her current carers are the latest in a long line who’ve looked after her, sad to say.’

‘She’s apparently the strangest child,’ Julia said. ‘Very complicated psychologically. Her mum has learning difficulties and the reason Cody ended up in care was because she used to shut her up in a cupboard for long periods when she was little.’ She gestured to her notes again. ‘According to what’s here, almost as one would put away a doll.’

There was a silence while we all tried to digest this. Didn’t matter how much you read about, or heard about or saw, some images were still difficult to process.

‘Exactly,’ Julia said, articulating what we were all thinking. ‘So, as you can imagine, she’s not the most straightforward child. We don’t have all the reports from her last school yet but social services have been very helpful and what we do know is that she’s … well, the notes I have here say she’s convinced she’s inhabited – well, I suppose the more correct word’s “possessed” – by the devil, and that when she’s not being a poppet, which she apparently can be, she tends to frighten other children.’

‘You don’t say,’ Gary observed wryly.

Julia acknowledged his comment with a trace of a smile. Then removed it. ‘But the most important thing is that she’s unpredictable, volatile and can apparently be very violent. She might have a kind of Tourette’s thing going on too – though that’s not been diagnosed – and we’re fairly sure she’ll end up having to go somewhere more specialised, but Mike’s agreed to take her temporarily – again, I hope you’re all happy with this, at least in principle, as long as she is manageable – so that she can be observed and formally assessed. Again, we’re thinking she should split her time between the learni– er,’ she stopped then, and listened. ‘Er … is that what I think it is?’ She then burst out laughing.

As well she might. As well might everyone else. Which everyone else did. Yes, it was definitely going to be that sort of day. Because what they could hear was some kind of rap-like singing … a ringtone my phone didn’t have last time it rang but which I knew, I just knew, it had now. With the volume set to maximum.

Flipping Kieron.

‘I’ll kill him,’ I growled, albeit to no one in particular, as I plucked my handbag from the floor beside my chair. ‘I’m sorry. Hang on. I’ll have my hand on it in just a minute … just got to … hang on. Nope … ah, maybe it’s here …’ I burbled on, realising I couldn’t actually remember where I’d put it, and cursing the day when I’d set the number of rings before it went to the answerphone, on the basis of the length of time it always seemed to take for me to find it in my bag. Oh, the bitter irony.

And that’s when the day got even worse. ‘Hang on,’ I said, snatching my satchel up and then, realising it was pinned under my chair leg by the strap, giving it a tug that was a little too much on the forceful side of tugging, meaning that when it suddenly came free, my arm shot in the air at precisely the moment when Gary, beside me, had lifted his hot tea to his lips.

His roar of pain as our forearms connected and the mug left his hand probably lifted the ceiling panels. ‘Jesus H!’ he yelped, leaping from his seat as the tea cascaded over him, and the chair he’d vacated toppled backwards onto the floor.

Jim was up on his feet too, and being closest to the tea things in the corner, grabbed a bottle of mineral water that had fortunately been left there by someone, popped the lid off and sprayed a jet of that over Gary, it being one of those sports types you can squeeze.

‘You okay, mate?’ Jim asked him, once all the water was gone.

Gary looked down, his whole front now a mass of sodden, dripping clothing. And then at me. ‘You know those days?’ he said, as I struggled with a packet of tissues that had – oh, second cruel irony – come immediately to hand. ‘Those days when you get out of bed,’ he went on, ‘and think – hmm, you know what? I suspect it’s going to be one of those days? Hmm,’ he finished, wiggling his sopping tie towards me. ‘That. Or, there’s a thought. Do you think it might have been a poltergeist?’

Chapter 2 (#u3d9ea8c9-bead-55f7-b9f7-a8162c54e9ad)

Autumn for both me and Mother Nature, I decided gloomily, as, back down in my classroom, I checked both the radiators. With its position at the periphery of the main school building, it was always chilly after a school holiday, and the six weeks of the summer break meant that, whatever the weather, it had the chance to really cool down good and proper. So although outside it was still bright and sunny – almost Indian summerish – inside it was positively Arctic.

Well, perhaps not Arctic – we weren’t quite in fur coat and boots territory just yet – but I was happy to remember that I’d left a chunky cardigan in one of the store cupboards at the end of the previous term. I went to fetch it, reflecting that perhaps it wasn’t that cold – perhaps it was more to do with the hot flush I’d both created and suffered up in the meeting room. I grimaced, remembering poor Gary’s astonished face and his obvious discomfort; had it not been for the thickness of his trousers I could have badly burned him. What on earth was wrong with me? What with ructions at home, and now school as well, I had a powerful wish to rewind the day and start again. No, scrub that – rewind most of the last three weeks.

Conscious of the ticking clock, I sat down at my desk and opened up my phone, intending to ring Kieron and give him a ticking off about altering the ringtone; he was getting way too old for such infantile stunts. But there, on the screen, sat a second text from Riley. Sorry, Mum! Love you! it said, followed by a row of kisses, which for some reason, rather than having the desired effect of making me smile, as it would normally, made me want to cry.

I hated rowing with my kids over anything. I was no soft touch – quite the opposite – I was big on boundaries and discipline. So being unpopular on occasion was a fact of parental life. But these last few weeks I’d apparently swapped my rhino hide for a skin made of porcelain. Which was as much a surprise to me as it was to the rest of the family.

It had started early in August, when Mike had suggested we go and spend a long weekend in his boss’s caravan in North Wales. And with the kids being of the age where they could think of better things to do with their respective weekends, he had also made the monumental decision that just the two of us would go.

‘What, leave them home alone for the whole weekend?’ I’d spluttered, when he suggested it over tea. I could already see it in my mind’s eye; me in panic mode for the duration. How could there possibly be any fun in that?

‘Please, Mum!’ Riley had pleaded, correctly sensing from her dad’s expression that she was probably onto a winner. ‘All of my friends have been looking after themselves for years! I swear I’ll keep the house clean,’ she added for good measure, knowing what might be my main worry after either of them being murdered in their beds. ‘And I promise I’ll look after our Kieron properly.’

‘I can take care of myself!’ Kieron replied indignantly. ‘In fact it’ll probably be me looking after you, Ri! We all know how scatty you are. I’ll probably have to show you how to turn the cooker on.’

If the fact that they were already at each other’s throats hadn’t already had me in a cold sweat, the thought of them being involved in using the cooker definitely would have done. And if Mike hadn’t stepped in I’m quite sure I’d have cancelled everything right then.

‘Casey, love,’ he said calmly, ‘me and you are going and that’s that. If we have to leave money for takeaways every night, then that’s what we’ll do, but we’re having a few days away by ourselves and these two will have to figure it out. They’re old enough to manage, and’ – he paused, to fix them one by one in his sights – ‘we know we can trust them not to throw any wild parties while we’re gone.’

My jaw had dropped. I hadn’t even thought about parties yet, which sent me into another panicked spin. But Mike was right, however much I flapped and fussed and fretted. There came a time, I supposed, when you just had to trust your kids to do the right thing; trust that you’d brought them up to be independent enough to look after themselves. Even so, our few days in Wales included many phone calls home, despite Mike trying to dissuade me from checking up on them all the time. But the snippets of reassurance I got from both Riley and Kieron did nothing to prepare me for the bombshell that was to hit us when we returned, and Riley had us gather once again around the table.

‘Now, before you start,’ she said, looking at me more than her father, ‘I’ve given this a lot of thought, okay? A lot. It’s not just a whim, and I know what I’m doing.’

‘What are you doing then? Spit it out,’ I said, my heart already lurching. The house was still standing and all seemed okay. So what was she about to announce to us? Was she pregnant?

Apparently not. ‘Well, I’ll just come right out and say it,’ she continued. ‘David and I have decided we’re going to move in together. Just as soon as we’ve found a nice flat.’

I stared open-mouthed at my pretty, young daughter. And then at Mike, just to check he was as horrified as me.

Strangely, he didn’t seem to be. And Riley looked positively indignant at my expression. ‘What?’ she demanded. ‘Why do you look so surprised? We’ve been together ages! I’d have thought you’d have been happy for me.’

‘Love, you’re too young for such a big thing!’ I said, gathering my wits and shooting Mike a call for support with my eyes. ‘What’s the rush anyway?’

‘Oh, Mum, I’m not too young at all,’ Riley said dismissively. ‘You just want to keep us like flipping babies! I’m a grown woman,’ she added. ‘And I’ve made my decision. In fact, while you were away, me and David have been flat-hunting.’

Ah, it was all making sense now. No wonder she was so keen to pack us off to Wales, I thought dejectedly. I stood up, struggling to keep a rein on my temper. Inexplicably, I also seemed to be on the verge of angry tears. ‘Oh, is that so?’ I snapped at her, banging my chair back into place, while Mike looked on, his expression apparently stunned. ‘Well, you can tell David that the plans have changed. It’s ridiculous, Riley. You’re both far too young to be thinking about that sort of thing right now. And the last thing you should be doing is wasting money on rent. You should be saving your money so you’ll have something for a deposit, when you can afford to buy somewhere.’

Like a house. Down the line. A good way down the line, too. Far enough down the line that I didn’t have the spectre of my little girl leaving home – leaving me – on the horizon. Because that was what it was really all about.

But it seemed it was going to happen, even so. For the first time in her life, my daughter took me on and went against me, insisting that, no matter what I said, she was moving out and there was nothing that her dad and I could say to change her mind. Not that Mike was saying anything, it had to be said. Not a peep.

Boxes suddenly started appearing on the landing, packed with things from her bedroom, almost taunting me, daring me to try to stop her, and relations between us were frosty, to say the least. Poor Kieron and Mike avoided both of us whenever we were in the house together, both hating the tension and the inevitable confrontations.

I behaved ridiculously, looking back – being both petulant and petty, grabbing things she’d packed and pointing out they weren’t hers to take with her, even going so far one day as to remind her that this was real life; that if she was leaving, then she’d have to find the money to buy home comforts of her own.

Cover myself in glory, I did not. It was almost a kind of madness. So much so that one day, just a week back, she’d collared me in the kitchen, grabbed my hands and said, ‘Mum, can’t you just be happy for me?’

It was at that point that I realised what I’d so far not seen. That it was me being the child here – a child who was simply afraid. Not for my daughter – she and David were clearly very much in love, and David was a hard worker who would always provide for her. No, I was afraid for myself. Maybe of acknowledging that I was getting older, maybe of the terror of empty nest syndrome. Either way, the realisation hit me like a brick when it did arrive. It was enough to end hostilities and was the first in a long line of lessons to come – reminders that the balance had shifted, and would keep doing so; that there were things my daughter could teach me. My adult daughter.

Which was not to say everything was immediately hunky dory. It was still difficult for me to let go, hard not to welly in. They duly found a flat to rent (only a few minutes from home, which cheered me up no end) and every night after work the pair of them would be round there, cleaning and painting. But now I’d come round to it, I still couldn’t let them alone. Hence this morning’s terse exchange, following my suggestion the previous evening that when I’d finished school for the day I could pop round and do the bathroom with my bleach spray and marigolds, the subtext of course being – and it wasn’t conscious, honestly – that they wouldn’t do it quite as well themselves.

And so came the text: Spoke to David and we’d rather sort the flat out ourselves Mum, so please don’t go round there, we’ll take you to see it when we’re done.

And so off went my text, which was supposed to be light-hearted, but clearly wasn’t: Fine, if that’s what you want, but don’t blame me if you both come down with something with all those germs!

And so to Riley’s riposte. A clearly heartfelt ‘whateva!’

I now texted back a ‘love you too’. On balance, it was helpful to be back in school again, whatever was – ahem – thrown at me, and as I closed my phone I reflected that having other things on my mind that I could hopefully do something to change, I would be much less preoccupied with things I could – and should – do nothing about. Like the fact that my daughter was grown and had a right to her own life. That where she led, Kieron would surely follow. No, I thought, pushing up the sleeves of the elderly cardigan, it was better to be here and be focused once again – on the poor kids who, in way too many cases I’d seen here, didn’t have the luxury of such trivial non-problems.

And not just the kids. The door flew open just as I was reaching for my staple remover. It was Gary, with a single word: ‘Help!’

I’d been quick to do just that while we were still in the meeting room, obviously, going as far as to suggest I grab the key to the lost property cupboard, just in case there was anything in there that would fit him, while someone – me, for preference – rinsed his trousers.

He’d declined, but, looking at him now, it seemed he was having something of a rethink. ‘Given the colour of them, I thought they’d dry without staining,’ he explained, gesturing towards the dark bloom that now spread even further than I remembered. ‘But when you look at this bit’ – he then gestured to a separate patch that had already dried – ‘I figured I was just going to end up with a big, obvious ring, so I doused them with water, as you can see –’

I nodded. ‘I sure can.’

‘And then tried to use the hand-dryer in the gents’ toilets – which was worse than useless – and then I remembered.’ He crossed his fingers. ‘Do you still have your hairdryer by any chance?’

In other circumstances I’d be hooting with laughter at the state of him, but not today. ‘I am so sorry, Gary,’ I told him, for the umpteenth time. ‘Really. Look at you. Such a clumsy thing for me to do – I’ve had a crappy morning, and my nerves must have been on edge. And then that bloody ringtone …’

‘On edge?’ Gary said with feeling. ‘Trust me, you and me both!’

‘You too?’ I asked.

He nodded. ‘Nerves-wise, absolutely.’

‘Why? What’s up?’ I asked, concerned at his suddenly vexed expression.

‘How long have you got?’ he said. ‘No, no. Bell’s going to go at any moment. Hairdryer first, explanations after.’

I did indeed have my hairdryer; in fact, I had what was called my ‘beauty cabinet’ – in reality a large plastic crate stashed on a shelf under my desk, which housed all manner of girly indispensables. It had grown almost organically; I had so many girls come to the Unit who’d not even had the time to run a brush through their hair in the morning that I had built up a supply of essentials. It was also a valuable icebreaker.

But right now, it had a different sort of job to attend to. Plugging it in, I gave it a blast in Gary’s general direction. ‘All sounds very mysterious,’ I said. ‘Spill, or the crotch gets it!’

Needless to say, he took it from me and attended to his wet patch, and so it was that the tableau presented moments later was of me looking on, grinning, while Mr Clark, his back to the door, was busy blasting his lower torso with hot air. At least, that was how Tommy Robinson found us.

I heard him before I saw him, even over the blast of my high-wattage hairdryer. Owner of an unmistakable Cockney accent – unmistakable in our school, anyway – Tommy was a year 9 pupil who’d been with me the previous term. A pupil I had a great deal of affection for.

‘Well, I ain’t gonna keep this quiet,’ he said, a smile widening on his astonished face. ‘This looks well sus, this does. Miss, what’s going on?’

There was no doubt about it; the sight of the school’s child protection officer blow-drying the band of his underpants – as he was by now – wasn’t one you saw every day. Gary took it as only he could, grinning ruefully at Tommy as he switched off the hairdryer, before touching his nose. ‘I’m saying nothing, kiddo,’ he told Tommy, ‘except do not get on the wrong side of Mrs Watson while holding a cup of tea, okay? Lethal, she is!’

Tommy nodded, grinning toothily, and I’m sure he believed it too. Which didn’t mean it wouldn’t be all round the school by the end of the morning.

Well, so be it. Nothing to be done. ‘Hi, Tommy,’ I said. ‘How are you?’

‘Cushty, Miss,’ he said. ‘I just thought I’d bob in and say hello, like, as I was passing. Though I can’t stop,’ he added. ‘Bell’s about to ring.’

‘Indeed it is, Tommy,’ Gary said, picking up the papers he’d been carrying. ‘I’ll walk with you.’

I smiled. No doubt to impress upon him the wisdom of keeping his intelligence to himself.

‘Hang on!’ I called as he went to follow Tommy through the door. ‘You haven’t told me yet. Why is today such a bad day to get tea on your pants?’

Gary smiled. ‘That will have to wait now, oh, impatient one. Though, seriously,’ he added, ‘I really would value your input. Tell you what, my office for lunch? Then I’ll tell you all about it. It’s juicy gossip, so make sure you bring biscuits!’

With that he rushed off, to avoid the inevitable gridlock on the corridors, leaving me open-mouthed and wondering what on earth he was going on about, my domestic worries happily now forgotten.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/casey-watson/mummy-s-little-soldier-a-troubled-child-an-absent-mum-a-shock/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Casey Watson

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 858.94 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 18.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Casey’s Unit is, as ever, full of troubled, disaffected pupils, and new arrival Leo is something of a conundrum.Thirteen year old Leo isn’t a bad lad – in fact, he’s generally polite and helpful, but he’s in danger of permanent exclusion for repeatedly absconding and unauthorised absences. Despite letters being sent home regularly, his mother never turns up for any appointments, and when the school calls home she always seems to have an excuse.Though Casey has her hands full, she offers to intervene for a while, to try get Leo engaged in learning again and remaining in school. The head’s sceptical though and warns her that this is Leo’s very last chance. But Casey’s determined, because there’s something about Leo that makes her want to fight his corner, and get to the bottom of whatever it is that compels this enigmatic boy to keep running away. With Leo so resolutely tight-lipped and secretive, Casey knows that if she’s going to keep this child in education, she’s going to have to get to the bottom of it herself…