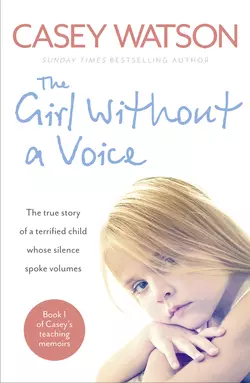

The Girl Without a Voice: The true story of a terrified child whose silence spoke volumes

Casey Watson

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 246.16 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 28.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Bestselling author and foster carer Casey Watson tells the shocking and deeply moving true story of a young girl with severe behavioural problems.This is the first of several stories about ‘difficult’ children Casey helped during her time as a behaviour manager at her local comprehensive.Casey has been in the post for six months when thirteen-year-old Imogen joins her class. One of six children Casey is teaching, Imogen has selective mutism. She’s a bright girl, but her speech problems have been making mainstream lessons difficult.Life at home is also hard for Imogen. Her mum walked out on her a few years earlier and she’s never got on with her dad’s new girlfriend. She’s now living with her grandparents. There’s no physical explanation for Imogen’s condition, and her family insist she’s never had troubles like this before.Everyone thinks Imogen is just playing up – except the member of staff closest to her, her teacher Casey Watson. It is the deadpan expression she constantly has on her face that is most disturbing to Casey. Determined there must be more to it, Casey starts digging and it’s not long before she starts to discover a very different side to Imogen’s character.A visit to her grandparents’ reveals that Imogen is anything but silent at home. In fact she’s prone to violent outbursts; her elderly grandparents are terrified of her.Eventually Casey’s hard work starts to pay off. After months of silence, Imogen utters her first, terrified, words to Casey: ‘I thought she was going to burn me.’Dark, shocking and deeply disturbing, Casey begins to uncover the reality of what Imogen has been subjected to for years.