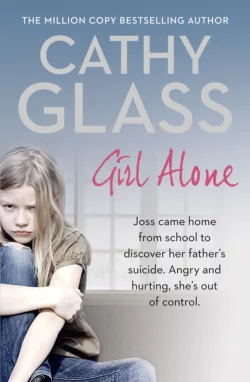

Girl Alone: Joss came home from school to discover her father’s suicide. Angry and hurting, she’s out of control.

Cathy Glass

Aged nine Joss came home from school to discover her father's suicide. She's never gotten over it.This is the true story of Joss, 13 who is angry and out of control. At the age of nine, Joss finds her father’s dead body. He has committed suicide. Then her mother remarries and Joss bitterly resents her step-father who abuses her mentally and physically.Cathy takes Joss under her wing but will she ever be able to get through to the warm-hearted girl she sees glimpses of underneath the vehement outbreaks of anger that dominate the house, and will Cathy be able to build up Joss’s trust so she can learn the full truth of the terrible situation?

(#u50ec7cd7-d34c-5179-9e5e-945635f0f694)

Copyright (#u50ec7cd7-d34c-5179-9e5e-945635f0f694)

Certain details in this story, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect the family’s privacy.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperElement 2015

FIRST EDITION

© Cathy Glass 2015

A catalogue record of this book is

available from the British Library

Cover photograph © Deborah Pendell/Arcangel Images (posed by model)

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cathy Glass asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780008138257

Ebook Edition © September 2015 ISBN: 9780008138264

Version: 2016-08-10

Contents

Cover (#u961e1002-d1a8-5db5-9719-4da1cdcf23f2)

Title Page (#ulink_21c33364-17da-5c1b-ae3d-ee766c9baff6)

Copyright (#ulink_15c2e91a-335d-5f00-99cb-1a90c8f2cd90)

Acknowledgements (#ulink_180f047c-b424-5f45-b703-4eea1bcd4b32)

Chapter One: Unsafe Behaviour (#ulink_3c8a8a84-5928-5a43-9c69-9d725bfbe81c)

Chapter Two: I Thought You Loved Me (#ulink_429320b5-79cf-5c7d-8574-56f2f1e8c8c4)

Chapter Three: Contract of Behaviour (#ulink_db4e4f63-72d7-59a7-82a1-9b5a858f046e)

Chapter Four: No Daddy Doll (#ulink_795a2bc4-fc05-5ec4-9d07-03ddeef55751)

Chapter Five: Eric (#ulink_cc4ed870-2111-509f-8130-429d765153aa)

Chapter Six: Deceived (#ulink_f23c12cf-a689-5d78-bf6a-fc856ae15475)

Chapter Seven: Letter from the Police (#ulink_dc18d427-74d1-5334-b391-be66b604706e)

Chapter Eight: Out of Patience (#ulink_23609fd4-7aa4-5542-855a-b63051532e7e)

Chapter Nine: On Report (#ulink_02f66187-89c1-569d-8b3b-88b581480fcf)

Chapter Ten: A Positive Sign? (#ulink_3f491021-d95f-561f-9553-35e0d29e09c2)

Chapter Eleven: No Progress (#ulink_008d859f-e2a3-599c-8943-4b973e85520a)

Chapter Twelve: Not My Father (#ulink_0a4bc040-1185-5f0a-9354-fd55f41d1f3a)

Chapter Thirteen: End It All (#ulink_4c23596e-92cf-5a66-90b5-49507da4f71a)

Chapter Fourteen: Turning Point? (#ulink_bf332458-d68a-580d-80fe-2dcbb6e4f0a8)

Chapter Fifteen: Doing the Right Thing (#ulink_1aaa7e69-d951-5628-bbdd-e21f503aedcf)

Chapter Sixteen: Failed to Protect Her (#ulink_8ce4a148-a3d6-53b7-b074-b5904f4c54d1)

Chapter Seventeen: Remorse, Guilt and Regret (#ulink_b4926e32-0e18-5334-b835-3258616fbfb2)

Chapter Eighteen: Lying? (#ulink_5cd15125-0e3d-5270-beba-65ea91307e80)

Chapter Nineteen: Alone (#ulink_88fe3df6-1e15-5fdc-a831-1cd3e9b7abda)

Chapter Twenty: Monday (#ulink_59d278db-0718-50ee-8e09-150e9a0f601f)

Chapter Twenty-One: Waiting for News (#ulink_9c85e366-2f4c-5d5c-849f-b978bc76d6e8)

Chapter Twenty-Two: Missing (#ulink_7170ffd7-59ed-5fec-b700-c3c60f7f91c3)

Chapter Twenty-Three: The Endless Wait (#ulink_4e74e539-eaf8-5cc5-819e-7a944a52a2fb)

Chapter Twenty-Four: Unbelievable (#ulink_f97e0455-3f54-5f4c-9965-eab9d89518fa)

Chapter Twenty-Five: And She Wept (#ulink_385028c8-381b-55f4-a2b7-c69efc04b1e5)

Chapter Twenty-Six: Bittersweet (#ulink_ddf50e01-4282-56d4-b4e2-30444a1d15f3)

Epilogue (#ulink_1045252c-d7c0-5806-b355-c2b2b961bf89)

Suggested topics for reading-group discussion (#u703fc4da-219c-5f48-a57f-29b258c85d2e)

Exclusive sample chapter (#u8e581523-a4a7-535a-a04c-60b91d4db31b)

Cathy Glass (#u99814e96-c294-5420-ac5c-f842e24c9cf2)

If you loved this book … (#uec676980-335d-5f79-9712-d6989f5f116f)

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter (#ub57c923b-cebc-53f1-a626-a47e2680c946)

About the Publisher (#u61050e3a-490d-5286-b2ae-ab0e9e80d545)

Acknowledgements (#u50ec7cd7-d34c-5179-9e5e-945635f0f694)

A big thank-you to my family; my editors, Holly and Carolyn; my literary agent, Andrew; my UK publishers HarperCollins, and my overseas publishers, who are now too numerous to list by name. Last but not least, a big thank-you to my readers for your unfailing support and kind words.

Chapter One

Unsafe Behaviour (#u50ec7cd7-d34c-5179-9e5e-945635f0f694)

I hate you!’ Joss screamed at the top of her voice. ‘I hate you. I hate your house and your effing family! I even hate your effing cat!’

Our beloved cat, Toscha, jumped out of Joss’s way as she stormed from the living room, stomped upstairs and into her bedroom, slamming the door behind her.

I took a deep breath and sat on the sofa as I waited for my pulse to settle. Joss, thirteen, had arrived as an emergency foster placement twelve days earlier; angry, volatile and upset, she wasn’t getting any easier to deal with. I knew why she was so angry. So too did her family, teacher, social worker, previous foster carers and everyone else who had tried to help her and failed. Joss’s father had committed suicide four years previously, when Joss had been nine years old, and she and her mother had found his lifeless body. He’d hanged himself.

This was trauma enough for any child to cope with, but then, when Joss was twelve, her mother had tried to move on with her life and had remarried. Joss felt rejected and that her mother had betrayed her father, whom she’d been very close to. Her refusal to accept her new stepfather as her younger brother had been able to had seen family arguments escalate and Joss’s behaviour sink to the point where she had to leave home and go to live with an aunt. The aunt had managed to cope with Joss’s unsafe and unpredictable behaviour for a month, but then Joss had gone into foster care. Two carers later, with Joss’s behaviour deteriorating further, she’d come to live with me – the day after Danny, whose story I told in Saving Danny, had left.

It was felt that, as a very experienced foster carer, I’d be able to manage and hopefully improve Joss’s behaviour, but there’d been little progress so far. And, while I felt sorry for her and appreciated why she was so upset and angry, allowing her to self-destruct wasn’t going to help. Her present outburst was the result of my telling her that if she was going out she’d have to be in by nine o’clock, which I felt was late enough for a girl of thirteen to be travelling home on the bus alone. I’d offered to collect her in my car from the friend’s house she was supposedly going to, so she could have stayed a bit later, but she’d refused. ‘I’m not a kid,’ she’d raged. ‘So stop treating me like one!’

It was Friday evening, and what should have been the start of a relaxing weekend had resulted in me being stressed (again), and my children Adrian (sixteen), Lucy (thirteen) and Paula (twelve) being forced to listen to another angry scene.

I gave Joss the usual ten minutes alone to calm down before I went upstairs. I wasn’t surprised to find Paula and Lucy standing on the landing looking very worried. Joss’s anger impacted on the whole family.

‘Shall I go in and talk to her?’ Lucy asked. The same age as Joss and having come to me as a foster child (I was adopting her), Lucy could empathize closely with Joss, but I wasn’t passing the responsibility to her.

‘Thanks, love, but I’ll speak to her first,’ I said. ‘Then you can have a chat with her later if you wish.’

‘I don’t like it when she shouts at you,’ Paula said sadly.

‘I don’t either,’ I said, ‘but I can handle it. Really. Don’t worry.’ I threw them a reassuring smile, then gave a brief knock on Joss’s door and, slowly opening it, poked my head round. ‘Can I come in?’ I asked.

‘Suit yourself,’ Joss said moodily.

I went in and drew the door to behind me. Joss was sitting on the edge of her bed with a tissue pressed to her face. She was a slight, petite child who looked younger than her thirteen years, and her usually sallow complexion was now red from anger and tears.

‘Can I come and sit next to you?’ I asked, approaching the bed.

‘Not bothered,’ she said.

I sat beside her, close but not quite touching. I didn’t take her hand in mine or put my arm around her to comfort her. She shied away from physical contact.

‘Why do you always stop me from having fun?’ she grumbled. ‘It’s not fair.’

‘Joss, I don’t want to stop you from having fun, but I do need to keep you safe. I care about you, and while you are living with me I’ll be looking after you like your mother.’

‘She doesn’t care!’ Joss blurted. ‘Not for me, anyway.’ This was one of Joss’s grievances – that her mother didn’t care about her.

‘I’m sure your mother does care,’ I said. ‘Although she may not always say so.’ It was a conversation we’d had before.

‘No, she doesn’t,’ Joss blurted. ‘She couldn’t care a toss about me and Kevin, not now she’s got him.’

Kevin was Joss’s younger brother. ‘Him’ was their stepfather, Eric.

‘I know it can be very difficult for children when a parent remarries,’ I said. ‘The parent has to divide their time between their new partner and their children. I do understand how you feel.’

‘No, you don’t,’ Joss snapped. ‘No one does.’

‘I try my best to understand,’ I said. ‘And if you could talk to me more, I’m sure I’d be able to understand better.’

‘At least you have time to listen to me. I’ll give you that. She never does.’

‘I expect your mother is very busy. Working, as well as looking after her family.’

Joss humphed. ‘Busy with him, more like it!’

I knew that with so much animosity towards her stepfather it would be a long time before Joss was able to return to live at home, if ever. However, we were getting off the subject.

‘Listen, love,’ I said, lightly touching her arm. ‘The reason you were angry just now wasn’t because of your mother or stepfather; it was because I was insisting on some rules. As you know, when you go out I expect you to come in at a reasonable time. The same rules apply to everyone here, including Adrian, Lucy and Paula.’

‘Adrian stayed out later than nine last Saturday,’ she snapped. ‘It was nearly eleven when he got back. I heard him come in.’

‘He’s two years older than you,’ I said. ‘And even then I made sure he had transport home. Lucy and Paula have to be in by nine unless it’s a special occasion, and they only go out at weekends sometimes.’

‘But they don’t want to go out as much as I do,’ Joss said, always ready with an answer.

It was true. Joss would be out every night until after midnight if I let her, as she had been doing with her aunt and previous foster carers.

‘I don’t want you going out every night, either,’ I said. ‘You have school work to do and you need your sleep. It’s not a good idea for a young girl to be hanging around on the streets.’

‘I like it,’ she said. ‘It’s fun.’

‘It’s unsafe,’ I said.

‘No, it isn’t.’

‘Trust me, love, a teenage girl wandering around by herself at night is unsafe. I’ve been fostering for fifteen years and I know what can happen.’ I didn’t want to scare her, but she had no sense of danger and I was very concerned about her unsafe behaviour.

‘I’m not by myself. I’m with my mates,’ Joss said. ‘You’re paranoid, just like my aunt and those other carers.’

‘So we are all wrong, are we, love? Or could it be that, being a bit older and having more experience, we have some knowledge of what is safe and unsafe?’

Joss shrugged moodily and stared at her hands clenched in her lap.

‘I’m still going out tonight,’ she said defiantly.

‘I’ve said you can. It’s Friday, but you will be in by nine o’clock if you are using the bus.’

‘What if I get a lift home?’ she asked.

‘I offered that before and you refused.’

‘Not from you – one of my mates’ parents could bring me back.’

I looked at her carefully. ‘Who?’

‘One of my mates from school, I guess.’

‘Joss, if you are relying on a lift then I would like to know who will be responsible for bringing you home.’

‘Chloe’s parents,’ she said quickly. ‘She’s in my class. She’s a nice girl. You’d like her.’

I continued to look at her. ‘And Chloe’s parents have offered to bring you home?’

‘Yes. They did before, when I was at my last carer’s. You can ask them if you like.’

On balance, I decided she could be telling the truth, and if she wasn’t, questioning her further would only back her into a corner and make her lie even more.

‘All right, then,’ I said. ‘I trust you. On this occasion you can come in at ten o’clock as long as one of Chloe’s parents brings you home.’

‘Ten’s too early if I have a lift,’ she said, trying to push the boundaries even further. ‘Eleven.’

‘No. I consider ten o’clock late enough for a thirteen-year-old, but if you want to raise it with your social worker when we see her on Monday, that’s fine.’

‘It’s not fair,’ she moaned. ‘You always fucking win.’

‘It’s not about winning or losing,’ I said. ‘I care about what happens to you and I do what I think is best to protect you. And Joss, I’ve told you before about swearing and that you’d be sanctioned. There are other ways to express anger apart from swearing and stomping around. Tomorrow is pocket-money day and I’ll be withholding some of yours.’

‘You can’t do that!’ she snapped. ‘It’s my money. The social services give it to you to give to me.’

‘I will be giving you half tomorrow, and then the rest on Sunday evening, assuming you haven’t been swearing. If you do swear, I’ll keep the money safe for you and you can earn it back through good behaviour.’

‘Yeah, whatever,’ she said, and, folding her arms, she turned her back on me.

I ignored her ill humour. ‘Dinner will be ready in about fifteen minutes. I think Lucy wants to talk to you. Is that OK?’

‘I guess.’

I went out of Joss’s room, called to Lucy that Joss was free and then with a sigh went downstairs to finish making the dinner. I knew I’d have another anxious evening worrying about Joss, and I’d be lying if I said I didn’t have doubts that I’d made the right decision in agreeing to foster her. I was especially concerned about the effect her behaviour could be having on my children. But I hadn’t really had much choice. I was the only experienced foster carer available at the time, and the social services couldn’t place Joss with an inexperienced carer, as they had done the first time. Joss had been that carer’s first placement and she’d only lasted two weeks. I hoped she was given an easier child for her next placement, or she might lose hope and resign.

Once dinner was ready I called everyone to the table. Adrian had stayed in his room while Joss was erupting, and now greeted her with an easy ‘Hi’. There wasn’t an atmosphere at the meal table as there had been on Tuesday and Thursday when I’d stopped Joss from going out at all. Now she was happy at the prospect of a night out and ate quickly, gobbling down her food and finishing first.

‘I’m going to get ready,’ she said, standing and pushing back her chair.

‘Wouldn’t you like some pudding first?’

‘Nah. I need to get ready.’

‘All right. Off you go, then.’ Normally I encouraged the children to remain at the table until everyone had finished, as it’s polite. But with a child like Joss, who had so many issues, I had to be selective in choosing which ones I dealt with first. I couldn’t change all her behaviour at once, and coming home at a reasonable time for her own safety and not swearing were more important than having exemplary table manners.

It was the beginning of June and therefore still daylight at seven o’clock when Joss yelled, ‘Bye. See ya later!’ from the hall and rushed out. I was in the living room drinking a cup of coffee, with the patio doors open and the warm summer air drifting in, thinking – worrying – about Joss. I’d thought about little else since she’d arrived. Although I’d been fostering for a long time, Joss was possibly my biggest challenge yet. I was also thinking about her mother, Linda, whom I would be meeting for the first time on Monday. Judging by what I knew from the social services, Linda had been a good mother and had done her best for Joss and her younger brother, Kevin, supporting them through the tragic loss of their father and then, more recently, gradually and sensitively introducing them to her new partner, Eric. I certainly didn’t blame Linda for wanting to move on with her life and remarry. I was divorced, so I knew what it was like bringing up children alone, and it’s not easy. Yet, sadly, it had all gone horribly wrong for Linda – by introducing Eric into her family she’d effectively lost her only daughter.

I never completely relaxed while Joss was out in the evening, but there was always something to do to occupy myself. I cleared up the kitchen, sorted the clean laundry and then returned to the living room and wrote up my fostering log. Foster carers are required to keep a daily record of the child or children they are looking after, which includes appointments, the child’s health and well-being, significant events and any disclosures the child may make about their past. When the child leaves, this record is placed on file at the social services. Once I’d finished, I watched some television.

Lucy, Paula and Adrian were in their rooms for much of the evening; the girls were doing their homework so that it wasn’t hanging over them all weekend, and then they chatted to their friends on the phone, and Adrian – who was in the middle of his GCSE examinations – was studying. By ten o’clock all three of them were getting ready for bed and I was listening out for Joss. I prayed she wouldn’t let me down this time. If she hadn’t returned by midnight I’d have to report her missing to the police, as I had done the previous Saturday. Then, doubtless, as before, she’d arrive home in the early hours, having wasted police time, and be angry with me for ‘causing a fuss’. I hadn’t given Joss a front-door key as I’d learnt my lesson from previous teenagers I’d fostered who’d abused the responsibility. My policy – the same as many other carers – was that once the young person had proved they were responsible, then they had a key, and it gave them something to work towards. But, of course, not having a key was another of Joss’s grievances that she would be telling her social worker about on Monday. Joss wasn’t open to reason; she felt victimized and believed she was invincible, which was a very dangerous combination.

At five minutes past ten the doorbell rang. I leapt from the sofa and nearly ran down the hall to answer it, grateful and relieved she’d returned more or less on time.

‘Good girl,’ I said as I opened the door. ‘Well done.’ I heard a car pull away.

‘Well done,’ she repeated, slurring her words. And I knew straight away she was drunk.

‘Oh, Joss,’ I said.

‘Oh, Joss,’ she mimicked.

Keeping her eyes down, she carefully navigated the front doorstep. ‘I’m going to bed, see ya,’ she said, and headed unsteadily towards the stairs.

As she passed me I smelt the mint she was sucking to try to mask the smell of alcohol, and also a sweet, musky smell lingering on her clothes, which was almost certainly cannabis – otherwise known as marijuana, weed or dope. I’d smelt it on her before. My heart sank, but there was no point in trying to discuss her behaviour with her while she was still under the influence. Greatly saddened yet again by her reckless behaviour, I watched her go upstairs.

I gave her five minutes to change and then went up to check on her. Her bedroom door was closed. I knocked but there was no answer, so I went in. She was lying on the bed, on her side, asleep, and fully clothed apart from her shoes. I eased the duvet over her legs, closed the curtains and then came out, leaving the door slightly open so I would hear her if she was sick or cried out. Joss often had dreadful nightmares and screamed and cried out in her sleep. On those nights I would immediately go to her room to comfort and resettle her, but that night – possibly because of the alcohol – she didn’t wake.

She was still asleep when I got up the following morning. As it was Saturday and we didn’t have to be anywhere I left her to sleep it off. She finally appeared downstairs in her dressing gown shortly after twelve. I was in the kitchen making lunch.

‘Sorry,’ she said, pouring a glass of water. Joss apologized easily, but it didn’t mean that she wouldn’t do it again.

‘Joss, we need to talk,’ I said.

I heard her sigh. ‘Can’t we make it later? After I’ve showered. I feel like crap.’

‘I’m not surprised. Have a shower and get dressed, then, and we’ll talk later. But we do need to talk.’

She returned upstairs to get ready and then half an hour later came down, and we all sat at the table for lunch. She looked fresher and chatted easily to Lucy, Adrian and Paula as though nothing untoward had happened, which for her it hadn’t. Arriving home drunk and smelling of dope was a regular occurrence – at her parents’, her aunt’s, her previous foster carers’, and now with me. She didn’t talk to me, though, and after lunch kept well away from me all afternoon, although I heard her chatting and laughing with Lucy and Paula. Not for the first time, I hoped their good influence would rub off on Joss and not the other way around. The girls were a similar age to Joss and it was a worry that her risky behaviour could appear impressive and exciting. I’d talked to them already about the danger she placed herself in, and would do so again.

It was nearly five o’clock before Joss finally came to find me. I was on the patio watering the potted plants. I knew why she was presenting herself now, complicit and ready to hear my lecture: she would want to go out again soon.

‘You wanted to talk?’ she said, almost politely.

‘Yes, sit down, love.’

I put the watering can to one side, pulled up a couple of garden chairs and in a calm and even voice began – the positive first. ‘Joss, you did well to come home on time last night. I was pleased. Well done. But I am very worried that you are still drinking alcohol and smoking dope after everything I’ve said to you.’

She looked down and shrugged.

‘I thought you understood the damage alcohol and drugs do to a young person’s body.’

‘I do,’ she said.

‘So why are you still doing it, Joss? You’re not daft. Why abuse your body and mind when you know the harm it’s doing?’

‘Dunno,’ she said, with another shrug.

‘It’s not only your physical and mental health that are being damaged by drink and drugs,’ I continued. ‘You’re putting yourself in great danger in other ways too. When someone has a lot to drink or smokes dope, they feel as though they haven’t a care in the world – that’s why they do it. But their awareness has gone; they lose their sense of danger and are more at risk of coming to harm.’ I was being careful to talk in the third person and not say ‘you’ so that she wouldn’t feel I was getting at her – another complaint of Joss’s. ‘Joss, apart from your health, I’m worried something dreadful could happen to you. Do you understand?’

‘Yes.’ She glanced at me. ‘So if I promise not to drink or smoke, can I go out tonight?’

‘Where?’

‘Chloe’s.’

‘Did Chloe’s parents know you were drinking and smoking drugs last night?’

‘We weren’t,’ Joss said.

I held her gaze. ‘Joss, I’m not stupid.’

‘No, they didn’t know. They weren’t in,’ she admitted.

‘So who brought you home last night?’

‘Not sure,’ Joss said easily. ‘Her uncle, I think.’

‘You think?’ Joss could have just admitted to eating too many sweets for all her lack of concern. ‘Joss, are you telling me that you were so off your head last night that you don’t even know who drove you home?’

‘I’m sure it was her uncle,’ she said.

I looked at her carefully. ‘Joss, I’m very worried about you.’

‘I know, you said before. I’m sorry, but I can look after myself.’

I wish I had a pound for every teenager who’s said that, I thought. ‘Joss, I don’t want to stop you from having fun and spending time with your friends, but I do need to keep you safe. Given what happened last night, and last weekend, the only way you’re going out this evening is if I take and collect you in my car.’

‘But that’s not fair!’ she cried, jumping up from her chair, all semblance of compliance gone. ‘You treat me like a fucking baby. I hate you and this fucking family! I hate everyone.’

Chapter Two

I Thought You Loved Me (#u50ec7cd7-d34c-5179-9e5e-945635f0f694)

I left Joss to calm down for a little longer than usual, allowing her time to reflect and me a chance to recharge my batteries. I found her outbursts exhausting and stressful. I was never sure what she might do or what she was capable of – the carers who’d looked after Joss before had reported that she’d hit one of them – and, although she hadn’t physically threatened me (yet), I always put some distance between us when she was very angry.

I continued to water the plants on the patio, largely as a displacement for my anxious thoughts. How could I get through to Joss before it was too late and she came to real harm? Continue as I had been doing with firm boundaries, love, care and concern? It had worked in the past with other young people I’d fostered, but would it work now? Joss was coming close to being the most challenging child I’d ever looked after, and it wasn’t something for her to be proud of.

Deep in thought, I set down the watering can and was about to go indoors to find Joss to talk to her, as I always did after one of her flare-ups, when she appeared on the patio.

‘Sorry,’ she said. ‘You can take and collect me tonight if you want.’

‘To Chloe’s?’ I asked, slightly surprised by the sudden turnaround.

‘Nah. To the cinema. We’ve decided to see a film.’

‘OK. That sounds good. Which film are you going to see?’

Joss rattled off the title of a film I knew was showing at the local cinema and then said, ‘It starts at seven-thirty, so I’m meeting Chloe there at seven to give us time to buy our tickets and popcorn. The film finishes at nine-forty-five, so you can collect me at ten.’

It did cross my mind that this all sounded a bit pat, but I had to trust Joss, so I gave her the benefit of the doubt. ‘All right. We’ll leave here at six-forty,’ I said. ‘Lucy is seeing a friend this evening, so I’ll drop her off on the way.’

‘I’ll tell her,’ Joss said helpfully, and went back indoors.

We ate dinner at six and then, having explained to Adrian and Paula that I was dropping off Lucy and Joss and I’d be gone for no more than an hour, we left. Sometimes I feel I’m running a taxi service with all the driving I do, but I’d much rather that and know the children are safe than have them waiting for buses that don’t always arrive, especially at night. Both girls sat in the rear of the car, and as I drove they chatted to each other, mainly about the film Joss was going to see. Lucy wanted to see it too and was hoping to go to the cinema with a friend the following weekend. I dropped Lucy off at her friend’s house (her friend’s mother was going to bring her home later) and then I continued to the cinema.

‘Chloe will be here soon,’ Joss said, opening her car door.

‘You can wait in the car until she arrives if you like,’ I suggested.

‘Nah, it’s OK. She might be waiting inside.’

Joss got out and closed the door. I lowered my window. ‘I’ll see you at ten o’clock, then,’ I said. ‘If Chloe doesn’t arrive, phone me and I’ll come back to collect you.’

‘Sure,’ Joss said. Then she spotted her waiting to cross the road. ‘Hi, Chloe!’ she yelled, waving hard.

‘Hiya!’ the girl yelled back.

I pulled away, pleased that I’d believed Joss. She’d come to me with a history of lying, so I found myself doubting everything she told me, which wasn’t good, and not like me. Usually I trusted people and accepted what they said, unless experience proved I should do otherwise. I was so pleased I hadn’t doubted Joss or questioned her further on her trip to the cinema with Chloe, as it could have undermined our already very fragile relationship.

At home, Paula and I watched some television together and then I suggested to Adrian that he left his studies for tonight and relaxed. The examinations he was revising for were important, as he needed good grades to continue to the sixth form, but I was concerned he was overdoing it. Half an hour later he joined us and we had a game of Scrabble before it was time for me to leave to collect Joss.

Although I was ten minutes early, Joss was already waiting outside the cinema with Chloe. They came over and I lowered my window.

‘Can you give Chloe a lift home?’ Joss asked. ‘It’s on the way.’

‘Of course. Get in,’ I said.

Both girls giggled, climbed into the back and giggled some more – possibly from teenage self-consciousness or embarrassment, I didn’t know. Chloe was a largely built girl with jet-black, chin-length hair, heavily made-up eyes and a very short skirt. She looked older than Joss, but then Joss was so petite she looked younger than thirteen. Both girls reeked of cheap perfume, which I assumed was Chloe’s, as Joss hadn’t been wearing any perfume when she’d left. It was so strong I kept my window open a little.

‘Was the film good?’ I asked as I drove.

‘Yeah,’ they said, and giggled again.

‘And you’re in the same class at school?’ I asked after a moment, trying to make conversation.

‘Yeah,’ Joss said, while Chloe remained silent.

‘Where do you live?’ I asked Chloe. ‘I’ll take you to your door.’

‘We pass it,’ she said. ‘I’ll shout when we’re there.’

There was more giggling and then whispering as I drove, and finally Joss yelled, ‘Stop! We’re here!’

I checked in my mirrors and pulled over. We were outside a small parade of shops about five minutes from where I lived. ‘I’ll take you to your door,’ I said to Chloe.

‘You have!’ Joss shouted, laughing. ‘She lives here.’

‘I live over the newsagents,’ Chloe explained. ‘Thanks for the lift.’

‘You’re welcome.’

There was more giggling as Chloe got out, and then before Joss closed the car door she yelled to her, ‘See ya Monday!’

‘Yeah, see ya, you old tart!’ Chloe yelled back.

Joss shut the car door with more force than was necessary and I pulled away. As we passed Chloe walking along the pavement Joss banged on her window. Chloe grinned and put up her middle finger in an obscene gesture. I didn’t comment. Chloe was the only friend of Joss’s I’d met so far and I didn’t want to criticize her, but she was so unlike Lucy’s and Paula’s friends that I had to stop myself making an instant judgement. If I felt Chloe might not be the best choice of friend for Joss, who was drawn to trouble, I didn’t say so, and reminded myself that first impressions can be deceptive.

‘How does Chloe get into her flat?’ I asked out of interest, for there hadn’t been an obvious front door.

‘Round the back of the shops and up the fire escape,’ Joss said.

‘You’ve been to her flat?’

‘Yeah, we hang out there sometimes.’

Now that the smell of perfume was starting to clear – with Chloe’s departure and the window open – I was beginning to catch the smell of something else, which I thought could be dope, but I wasn’t sure. I knew that just as mints are used to mask the smell of alcohol, dope, tobacco, glue and other substances on the breath, so perfume and cologne can be used to try to hide the smell from clothes, skin and hair. I wasn’t going to accuse Joss unjustly, but I wanted her to know I was aware of the possibility that she may have been using again.

‘What’s the perfume?’ I asked.

‘It’s Chloe’s. I don’t know what it’s called.’

‘It’s very strong,’ I said, and I glanced at her pointedly in the mirror.

Joss immediately looked away. ‘I haven’t been smoking, if that’s what you think,’ she said defensively.

‘Good.’

I guessed that Joss would want to go out again on Sunday, as previous carers had complained that she went out as soon as she was dressed and didn’t return until after midnight, and then she was too tired to get up for school on Monday morning. Joss had been out both Friday and Saturday evening, so I thought it was reasonable that she spent Sunday with us. I look upon Sundays as family time, as many others do, and I like us to try to spend most of it together, as a family, which obviously includes the child or children I am fostering. When my children were little I used to arrange an activity on a Sunday, visiting a park or place of interest, or seeing family or friends, but now they were older I accepted that they didn’t always want to be organized every weekend and liked to spend time just chilling. However, we hadn’t been out together the previous two Sundays, so I thought a family outing now would be nice for everyone, including Joss. Doing things together encourages bonding and helps improve family relationships – something Joss was a bit short on. I knew Adrian would want to do some exam revision first, so I would make it for the afternoon only. I racked my brains for an activity that wasn’t too far away, preferable outdoors as the weather was good, and that they’d all enjoy. I came up with the Tree Top Adventure Park. It was an assault course set in the treetops of a forest about half an hour’s drive away. It had zip wires, swing bridges and rope ladders, and was suitable for ages ten and above. I’d taken my children before but not for a while. I mentioned it to Lucy and Paula first, who liked the idea, and then to Adrian, who agreed that taking the afternoon off would be fine.

Then I knocked on Joss’s door.

‘Yeah? Come in!’ she called from inside.

She was propped up on her bed using the headboard for support, earphones in, and flicking through a magazine. I motioned for her to take out an earphone so she could hear me, then I explained about the proposed outing, emphasizing how much fun it would be and that it was suitable for teenagers, girls and boys. ‘You’ll need to wear something a bit looser than those tight jeans,’ I suggested, ‘so you can climb. And trainers rather than sandals.’

‘Nah, it’s OK,’ she said, returning her attention to the magazine. ‘You can go. I’ll stay here.’

‘Joss, I’d like you to come with us, so would the girls and Adrian. While you’re here you’re part of this family and it’s nice to do things together as a family sometimes.’

‘Nah, thanks,’ she said. ‘I’m OK.’

‘I want you to come, Joss,’ I said.

She looked up. ‘If you don’t trust me here alone I can go out and meet up with my mates. That’s what I did when the other carers went out.’

‘But I won’t do that,’ I said more firmly. ‘I would like you to come. It’s just for the afternoon and I’ve chosen an activity you’ll like.’

‘What if I don’t like it?’ Joss said. She challenged me on everything if she had a mind to.

‘Then you’ll put it down to experience and won’t ever go again. But at least you will have tried it.’

‘Nah,’ she said again. ‘It’s not my thing.’ She went back to the magazine and flipped a couple of pages.

There was no way I was leaving Joss alone in the house having heard about the mischief she’d got up to at her previous carers’ when she’d been left alone – underage drinking and smoking dope with friends, the house trashed and the police called. Neither was I agreeing to her going out and spending the afternoon on the streets, with the potential for getting into more trouble. Apart from which, I wanted Joss to come with us as part of the family and have a good time.

‘I think you’ll enjoy it,’ I said.

‘Nah. I won’t,’ she said.

I took a breath. It was hard work. ‘OK, Joss, the bottom line is: you come with us, which is what I would like, or I can take you to another foster carer for the afternoon.’ I knew carers who would help me out if necessary, as I would help them, but whether they were available at such short notice on a Sunday, I didn’t know. I was hoping I wouldn’t have to put it to the test.

‘I don’t want to go to another carer,’ Joss moaned, her face setting.

‘I don’t want you to go either. I want you to come with us.’ I smiled.

‘Is it only for the afternoon?’

‘Yes. We’ll leave here around twelve-ish and we’ll be back about six.’

‘OK. You win. Again,’ she said. ‘But I won’t enjoy myself. I’ll be miserable all afternoon.’

‘Joss, I bet you two pounds you do enjoy yourself. If you do, you’ll win; if not, I win.’

It took her a moment to work this out and then she smiled.

Despite her appalling behaviour and bravado, I liked Joss. I felt that underneath there was a nice kid trying to get out. I appreciated that losing her father in such tragic circumstances and then not getting on with her stepfather was a bad deal, but I was hoping that coming to live with me would give her the chance to sort her life out.

Joss did thoroughly enjoy herself at the Tree Top Adventure Park, despite staying in the very tight jeans that pinched her legs when she climbed. She was confident and tackled even the very high walks, wires, swings and ladders fearlessly. So much so that the supervisors stationed throughout the park warned her a few times to take it more steadily or she could fall and injure herself. But then, of course, that was part of Joss’s problem. She had no sense of danger. Paula and Lucy took the course together at a steadier pace, and Adrian met a friend from school and they went off together. I completed one circuit and then sat on a bench in the shade of the trees reading my book and also watching the young people having fun. By six o’clock they were all tired and hot and sitting with me in the shade eating ice creams. Our tickets allowed us to stay until the park closed at eight o’clock, but everyone agreed they were ready to go. As we left, Joss actually asked if we could come again.

‘We could,’ I said. ‘But there are other fun places to go on a day out.’

‘But I like it here. I’ve had a good time,’ she said.

‘Great. You win the bet,’ I said. I handed her the two pounds.

On the way home we picked up a takeaway, and after we’d eaten Adrian resumed his studies, Lucy and Paula went up to Paula’s room and Joss went to hers. I was just congratulating myself on a successful day when Joss appeared in the living room. I knew straight away from her expression she was in challenge mode. ‘As I did what you wanted me to this afternoon, can I go out now?’ she said.

‘No, Joss. Not tonight, love. You were out Friday and Saturday, and you have school tomorrow. It’s already seven-thirty.’

‘I’ll be back by ten. Just for a couple of hours.’

‘No, not tonight. Two nights out over the weekend is plenty.’

‘But that’s not fair.’

‘I think it is fair, but you can raise it with your social worker tomorrow if you wish.’

‘I fucking will!’ she said, stamping her foot. ‘And you can’t stop my pocket money now, because you’ve already given it to me! Cow!’

She stormed out of the living room and upstairs into her bedroom, slamming the door behind her. I felt my heart start racing. Another confrontation. It was so stressful. But I reminded myself that at least she was doing what I’d asked and was staying in, which was a huge improvement. At her previous carers’ she’d come and gone as she’d liked, often defying them when they said she had to stay in. Foster carers (and care-home staff) are not allowed to lock a child in the house or physically prevent them from leaving, even if it is for the child’s own good. It’s considered imprisonment. With your own child you’d do anything within reason to keep them safe, and I think the whole area of what a carer can and can’t do to keep a young person safe is something that needs to be looked into, with practical guidelines set up.

I tried not to take Joss’s words personally. I knew she was angry – not only with me, but with life in general – and I was an easy target, especially when I put boundaries in place. Once she’d calmed down she usually reverted to being pleasant and often apologized. Sure enough, ten minutes later I heard her bedroom door open. She came down and said she was sorry. Then she joined Lucy and Paula in Paula’s room, where the three of them sat chatting and listening to music until it was time to get ready for bed.

Joss had another nightmare that night. I heard her scream and was out of bed in a heartbeat, going round the landing to her room. As usual, she was sitting up in bed with her eyes closed, still half asleep. Normally she didn’t say anything as I resettled her, and in the morning she would have no recollection of the nightmare, so I no longer mentioned it. But now, as I gently eased her down and her head touched the pillow, she said softly, ‘Daddy used to take us on outings too.’

‘That’s a lovely memory,’ I said quietly. Her eyes were still closed. I sat on the edge of the bed and began stroking her forehead to soothe and comfort her. I guessed the memory had been triggered by our day out.

Her eyes stayed shut, but then her face crumpled in pain. ‘Why did you leave us, Daddy? Why? I thought you loved us.’ A small tear escaped from the corner of her eye and ran down her cheek onto the pillow. I felt my own eyes fill. The poor child.

She didn’t say anything further and appeared to be asleep. I continued to stroke her forehead and soothe her as she drifted into a deep sleep. Then I stood and quietly came out and returned to bed. Joss had never talked about her father to me, but I guessed the horrific memory of that day was probably as fresh as ever. There are so many feelings connected with the suicide of a loved one, apart from the immense sadness at losing them: regret and remorse at things that were said and unsaid; rejection because the person chose to go; guilt (was it something I did?) and anger – perhaps the most difficult to cope with – that the person has gone. Joss was clearly still hurting badly, and I didn’t think her behaviour would improve until she had dealt with all the conflicting emotions she must still be wrestling with following her father’s death.

The following morning Joss didn’t mention her dream. I assumed that, as before, she hadn’t remembered it, so I didn’t say anything. She had her usual cereal and a glass of juice for breakfast, and then, as I saw her off at the door, I reminded her that she had to go straight to the council offices after school for the meeting with her social worker. I was going too, and so was her mother. I’d offered to collect Joss from school, which would have guaranteed that she arrived, and on time, but she’d refused, and I felt it wasn’t something I needed to take a stand on.

‘Make sure you catch the first bus as soon as you come out of school,’ I emphasized to Joss as I said goodbye. ‘No chatting with your friends tonight.’

‘I know. I’ll see you there,’ Joss said. ‘But if Mum brings him to the meeting, I’m leaving.’

As usual, ‘him’ meant her stepfather, Eric, whom Joss so deeply resented. I hadn’t met her mother or stepfather yet, and I didn’t know if Eric would be there, but it wasn’t for me to tell the social worker whom to invite to a meeting. She was aware of the animosity between Joss and her stepfather, so hopefully would have advised Joss’s mother, Linda, accordingly.

During the morning, Jill, my supervising social worker, telephoned to see how the weekend had gone, so she had an update from me prior to the meeting. She would be there too. All foster carers in England have a support social worker, also known as a supervising social worker or link worker, supplied by the agency they foster for. Jill had met Joss a few times and was aware of her history. I gave Jill a brief résumé of our weekend, good and bad, but emphasizing that we’d had a good afternoon on Sunday, and Jill said she’d see me at four o’clock at the meeting.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/cathy-glass/girl-alone-joss-came-home-from-school-to-discover-her-father-s/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Cathy Glass

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Aged nine Joss came home from school to discover her father′s suicide. She′s never gotten over it.This is the true story of Joss, 13 who is angry and out of control. At the age of nine, Joss finds her father’s dead body. He has committed suicide. Then her mother remarries and Joss bitterly resents her step-father who abuses her mentally and physically.Cathy takes Joss under her wing but will she ever be able to get through to the warm-hearted girl she sees glimpses of underneath the vehement outbreaks of anger that dominate the house, and will Cathy be able to build up Joss’s trust so she can learn the full truth of the terrible situation?