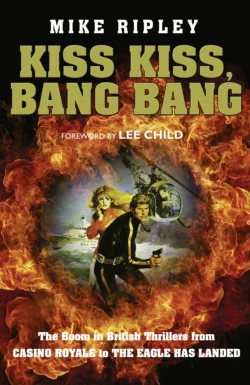

Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang: The Boom in British Thrillers from Casino Royale to The Eagle Has Landed

Mike Ripley

WINNER OF THE HRF KEATING AWARD FOR BEST NON-FICTION CRIME BOOK 2018An entertaining history of British thrillers from Casino Royale to The Eagle Has Landed, in which award-winning crime writer Mike Ripley reveals that, though Britain may have lost an empire, her thrillers helped save the world. With a foreword by Lee Child.When Ian Fleming dismissed his books in a 1956 letter to Raymond Chandler as ‘straight pillow fantasies of the bang-bang, kiss-kiss variety’ he was being typically immodest. In three short years, his James Bond novels were already spearheading a boom in thriller fiction that would dominate the bestseller lists, not just in Britain, but internationally.The decade following World War II had seen Britain lose an Empire, demoted in terms of global power and status and economically crippled by debt; yet its fictional spies, secret agents, soldiers, sailors and even (occasionally) journalists were now saving the world on a regular basis.From Ian Fleming and Alistair MacLean in the 1950s through Desmond Bagley, Dick Francis, Len Deighton and John Le Carré in the 1960s, to Frederick Forsyth and Jack Higgins in the 1970s.Many have been labelled ‘boys’ books’ written by men who probably never grew up but, as award-winning writer and critic Mike Ripley recounts, the thrillers of this period provided the reader with thrills, adventure and escapism, usually in exotic settings, or as today’s leading thriller writer Lee Child puts it in his Foreword: ‘the thrill of immersion in a fast and gaudy world.’In Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang, Ripley examines the rise of the thriller from the austere 1950s through the boom time of the Swinging Sixties and early 1970s, examining some 150 British authors (plus a few notable South Africans). Drawing upon conversations with many of the authors mentioned in the book, he shows how British writers, working very much in the shadow of World War II, came to dominate the field of adventure thrillers and the two types of spy story – spy fantasy (as epitomised by Ian Fleming’s James Bond) and the more realistic spy fiction created by Deighton, Le Carré and Ted Allbeury, plus the many variations (and imitators) in between.

Copyright (#ulink_f41b4eaf-6f90-5711-881b-ce2f414d7589)

Published by COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Copyright © Mike Ripley 2017

Foreword © Lee Child 2017

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover illustration: detail from When Eight Bells Toll by Alistair MacLean © HarperCollinsPublishers 1981 (front); Robert Kyle’s Kill Now, Pay Later by Robert McGinnis © Dell Publishing/Penguin Random House 1960 (back).

Author photograph © Mike Ripley

Mike Ripley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologizes for any errors or omissions on the above list and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008172237

Ebook Edition © May 2017 ISBN: 9780008172244

Version: 2017-11-20

Dedication (#ulink_ac13e2df-6a58-5562-8c69-af961c56fa77)

For Len Deighton,

who has a lot to answer for.

SPOILER ALERT (#ulink_d2c51c61-aaa8-5887-9e1d-236e6c091755)

There will be spoilers. Live with it. Many of the thrillers referred to here were published fifty years ago. You’ve had time.

THRILLERS (#ulink_d2c51c61-aaa8-5887-9e1d-236e6c091755)

‘A book, film, or play depicting crime, mystery, or espionage in an atmosphere of excitement and suspense.’

Collins English Dictionary

‘What exactly is a thriller? The term seems to cover a multitude of sins and quite a fair proportion of virtues.’

Margery Allingham, 1931

‘You after all write “novels of suspense” – if not sociological studies – whereas my books are straight pillow fantasies of the bang-bang, kiss-kiss variety.’

Ian Fleming in a letter to Raymond Chandler, 1956

Contents

Cover (#udc59de6c-705a-5f16-837a-b5dd8684ced7)

Title Page (#uf1e68488-a37a-562f-b537-bfda3990b879)

Copyright (#u410c475b-a55b-50a9-9378-37a894fc292f)

Dedication (#u1de002b6-2251-5630-a02a-a9741f98c9e4)

Spoiler Alert (#uea762348-777a-556b-8256-6b03bf9f65a4)

Thrillers (#u0705f81d-32e3-5069-b28b-8edab0488c8e)

Foreword (#ub1c8256a-9346-5c75-bf20-913967247a37)

Preface (#u50ce7f8c-32b8-5ef5-9edb-12d0d97be045)

Chapter 1: A Question of Emphasis (#u475a4cc9-159f-547b-afcd-024b1ad693f2)

Chapter 2: The Land Before Bond (#u3266babd-843b-5a74-b4c1-0349f0a94fdd)

Chapter 3: Do Mention the War (#u3ff8d1a8-0046-5dff-b7ed-1690d90a5d77)

Chapter 4: Tinkers, Tailors, Soldiers, Spies. But Mostly Journalists. (#u9b2d9f6d-1a02-5a1a-ba20-6ddbfea76b58)

Chapter 5: End of Empire (#uad88998d-aeab-5ff6-aa4c-b1d5f26ebf69)

Chapter 6: Travel Broadening the Mind (#u5b7c88d5-f167-5f71-9c9d-10fb2eeb70f9)

Chapter 7: Class of ’62 (#u590d5fde-1f3e-5182-8437-53b68bf289c0)

Chapter 8: The Spies Have It, 1963–70 (#u4a8096b7-68fd-5c5a-b0e2-df4c47726ea0)

Chapter 9: The Adventurers, 1963–70 (#ue26c53c3-2dbd-5300-a3d3-1dcc69f06bf4)

Chapter 10: The Storm Jackal Has Landed – The 1970s (#u2604c80c-47ba-5671-ad47-f33a3067c96b)

Chapter 11: The New Intake (#uee6c4c99-89ad-56cd-89ce-228d53440065)

Chapter 12: Endgame (#uec5706d0-e0b5-5f84-99c9-1cb8c9da7da8)

Appendix I: The Leading Players (#ub4281226-a4e6-5eaf-ad82-c2103cc82e9b)

Appendix II: The Supporting Cast (#u957c9019-305d-594c-9064-a5c4cd5813ec)

Notes & References (#uabdaee7a-aaaf-54c4-850d-8af06ce00fdd)

Acknowledgements & Bibliography (#uf7df0d65-c7ef-580b-b8a0-f7f0bd2d9d66)

Index (#u20c4338b-aa0e-5281-ba52-3cc92aa29f3e)

Also by Mike Ripley (#u1ad2cb02-aeb9-52de-bfcc-2d0af8ae6434)

About the Publisher (#u9ed8dd63-29f5-5f2d-91e7-838cba0e9611)

FOREWORD (#ulink_a0a10e0d-3ad8-5b33-bfc2-3e5d60509ebe)

Some time ago Mike Ripley e-mailed and asked if I would write a foreword for his new book. I knew roughly what it was about: Mike and I bump into each other a couple of times a year, at industry junkets, and like writers everywhere we always ask about works in progress – secretly hoping, I suppose, that the other guy is having it even worse than we are. So I knew the project was a survey of British thriller fiction during the two golden decades between the mid-Fifties and the mid-Seventies. Knowing Mike, I knew the scholarship would be meticulous; I knew the writing would be pleasantly breezy, but always willing to seize passionately upon a point, and render a clear and acute conclusion, without fear or favour. It would be a book I would want to read – maybe even pay for – so why not get it early and free? So I said yes.

Mike is a slightly older codger even than I, so there was no immediate e-mail response to my response. I got the impression he treats e-mail like the country squire he pretends to be, treats the post, perhaps once a day, perhaps in the early morning, at the breakfast table. I spent the rest of my own day writing a newspaper article commissioned by the New York Times. I was never quite sure what they wanted, but it seemed to require a retrospective mood, even elegiac, starting right back at the beginning, which in my case meant growing up in provincial post-war Britain. I polished the piece and sent it off.

Then – bing – the attachment arrived from Ripley.

For the New York Times, I had started, ‘Objectively I was one of the luckiest humans ever born.’

Ripley’s preface started, ‘I am of the luckiest generation.’

He’s a couple of years older than me, which makes us a typical older brother–younger brother age pairing right in the middle of the luckiest demographic in history. For the Times I said we were a stable postwar liberal democracy, at peace, with a cradle-to-grave welfare system that worked efficiently, with all dread diseases conquered, with full employment for our parents, with free and excellent education from the age of five for just as long as we merited it. We had no bombs falling on our houses, and no knocks on our doors in the middle of the night. No previous generation ever had all of that, not in all of history, and standards have eroded since. We were very lucky.

But, I said, it was very boring. Britain was grey, exhausted, physically ruined, and financially crippled. The factories were humming, but everything went for export. We needed foreign currency to pay down monstrous war debt. Domestic life was pinched and austere.

We escaped any way we could. Reading was the main way. Thrillers were the highest high, and British writers were never better than during our formative years. But finding out about them was entirely random. Obviously there was no Internet – electricity itself was fairly recent in some of our houses – and it was rare to meet a fellow aficionado face to face, and enthusiast bookshops were inaccessible to most of us, and so on. We blundered from one random find to another. Some of us had older brothers blazing the way, and really that’s exactly what this book is – the perfect older brother, equipped with 20/20 hindsight, saying, ‘Read this, and then this, and this, and this.’

I can follow my own snail-trail across the landscape that Ripley so comprehensively describes. I can pick my way from A to Z, book to book, zigging and zagging. I can remember the joy of escaping, and the thrill of immersion in a fast and gaudy world, and wanting to do it again and again. In that sense this book feels like my own personal memoir, and inevitably it will to thousands of others too, with their own unique zigzag snail-trails, and as such it seems of great sentimental value, like a long-lost diary, like a list of the way stations that carried us through a time that promised to be forever grey.

It’s also sad, in a way. We all missed so much. Zigging and zagging are all very well, but must always conspire to pass by most good things, simply by the law of averages. But what’s done is done. Instead we should treat this book like a catch-up manual, and fill in what we didn’t read the first time. Some of it might be really good. Some of it might recapture the feeling.

Which would be worth something. A book I might pay for, indeed.

Lee Child

New York

2016

PREFACE (#ulink_caca5297-2f27-5a3d-9f26-ae28def0b0b9)

I am of the luckiest generation, the one which avoided National Service and enjoyed a fee-free university education – they even gave you a grant for going.

I spent my early teenage years, and all my pocket money, reading thrillers. It was the first half of the 1960s and I could, by haunting second-hand bookshops and market stalls, usually pick up two, sometimes three, recent paperbacks for the same price as a ‘Top Ten’ 45 rpm vinyl single, which seemed a far better use of my limited disposable income. At least that was my thinking until I discovered girlfriends, and the Rolling Stones recorded Beggar’s Banquet.

I was brought up in a house where a large pile of library books, all fiction, were refreshed every fortnight. Even in a small coal mining village in the West Riding of Yorkshire, there was a public library attached to the infant school which was open two or three evenings a week and allowed four books to be borrowed on each library ticket. My father was a voracious reader of Westerns whilst my mother’s passion was for historical novels. I read thrillers and I knew exactly what I meant when I said that then, although today I would differentiate and describe myself as having started out on adventure thrillers and then moved on to spy thrillers. Unlike many of my peers, science fiction did not entice and detective stories or ‘whodunits’ to me were stale and unappetizing (with the singular exception of Raymond Chandler).

A thriller would offer excitement and almost certainly a connection to WWII. This was a familiar and important reference point as the comic books I had been brought up on as a young lad did not feature Batman, Superman or a Hulk, but soldiers – invariably British or Commonwealth troops – fighting on land, sea, and air against implacable German, inscrutable Japanese and unreliable, if not cowardly, Italian foes. These 64-page book-format magazines were published, rather grandly, as ‘Libraries’. There was War PictureLibrary, Battle Picture Library, Air Ace Picture Library and, from a rival stable, Commando. They cost a shilling (5p) each and were, as far as I could tell being a bit of a military history buff, pretty accurate when describing the campaigns of World War II.

Why the obsession with WWII? I do not come from a military family, had no career aspirations in that direction (not even the Boy Scouts), and the war itself had ended more than seven years before I was born. Yet it somehow dominated my childhood. The headmaster of my village primary school was a former Royal Navy chief petty officer, the village priest had been a Chaplain with the 14th Army in Burma, I had an impressive collection of toy soldiers, and war films always seemed to be on television – mostly proving that no prison camp could ever hold plucky British escapees when they set their mind to it. When the minor public school I attended took the revolutionary step of starting up a Film Club, the first feature it showed was The Guns of Navarone. (The Headmaster who sanctioned the formation of that Film Club also prohibited any boy from going to the local cinema to see Lindsay Anderson’s If … in 1968. He was clearly a man who understood the power of film.)

It was inevitable that I would discover Alistair MacLean’s wartime classic about the Arctic convoys, HMS Ulysses, and although it is (honestly) more than fifty years since I read it, I can vividly recall incidents from it, not least the scene in a snowstorm when the ship’s pom-pom guns are fired whilst their metal muzzle covers are still in place.

This was a war novel, but it was a tense, dramatic and thrilling story with lashings of suspense and mystery. Not ‘mystery’ as in ‘whodunit?’ but rather ‘how can they survive this?’ The next MacLean I tried, South by Java Head, was also set during WWII but with more skulduggery than actual combat. Other MacLean books were devoured in quick succession and these were not war stories, yet the heroes were resourceful and brave, the stakes life-and-death, the settings ranging exotically from the South Seas to Greenland, and the action fast and furious. These were not only ‘what is really going on?’ mysteries but also ‘how do they get out of this?’ adventures.

I was no longer reading war stories, I was reading thrillers and then, at the age of 12, I discovered James Bond and realised there was more than one type of thriller out there.

With the benefit of half a century of hindsight I realise that there was a real purple patch of British thriller writing in the Sixties and into the Seventies and I had been hungrily reading my way through it. The ‘Golden Age’ of the British detective story (usually accepted to be the Twenties and Thirties) had well and truly lost its lustre by the Swinging Sixties, but a new generation of thriller writers had emerged after the war, appealing to a much wider audience. Thanks to the expansion of public libraries and attractive, mass market paperback editions British writers dominated the national and international bestseller lists. Nobody, it seemed, when it came to action-adventure heroes, secret agents, or spies, did do it better.

After the dull, austere post-war period as Britain declined as a world power, its thriller fiction had – like British pop music and Carnaby Street fashion – moved from black-and-white to Technicolor. The thrillers just kept coming: bigger, brasher, and more fantastical than ever. The early death of Ian Fleming in 1964 did nothing to slow the rush of would-be successors to Bond, in fact it accelerated the flow as did the success of the Bond films. New voices joined in, establishing a school of more realistic spy fiction born in the shadow of the Berlin Wall and more films followed. The year 1966 seemed to have been a peak year, with twenty-two spy or secret agent films released in the UK – admittedly several of them spoofing the genre and only a few of which have stood the test of time.

Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang attempts to be a reader’s history – specifically this reader – of that action-packed period around the Sixties when, having lost an Empire, Britain’s thriller writers and their fictional heroes saved the world and their books sold by the million. It was very much a British initiative and it only faltered in the mid-Seventies when American thriller writers began to flex their muscles, different types of thriller emerged, and the detective or crime story began to enjoy a renaissance.

This book concentrates unashamedly on the British spies, secret agents, and soldiers, and their creators and publishers, who saved the world from Nazis, ex-Nazis, proto-Nazis, the secret police of any (and all) communist country, super-rich and power-mad villains, traitors, dictators, rogue generals, mad scientists, secret societies, ruthless businessmen and even, on one occasion, an ultra-violent animal protection league which kills anyone who kills animals for sport! I will shamelessly ignore the fictional heroes of other countries and concentrate on British authors, with the exception of a handful of Australians and South Africans, whose primary publishers were in the UK.

It will also limit itself to thrillers rather than ‘detective stories’ or ‘whodunits’. This means that some famous names hardly feature at all, those authors who may well have dipped a toe into the thriller pool but are far better known for their crime novels; for example, the wonderful and much-missed Reginald Hill. Similarly, I will down-play one of my favourite writers, that supreme stylist P. M. Hubbard, who wrote novels of suspense on a domestic, almost micro, level. The thriller-writers taking centre-stage here are those who worked on a broader canvas with sweeping brush-strokes and who came to prominence in the period 1953 to 1975. Some who had established themselves before the Second World War were still writing and experienced something of a ‘second wind’ in the Swinging Sixties.

I should insert here a warning: fans of Eric Ambler (1909–98) and Graham Greene (1904–91) will feel themselves short-changed. Both these authors were immensely influential on the form and tone of the thriller genre (novels and films); indeed, their surnames became adjectives frequently used by reviewers. It was high praise indeed for a thriller to be called ‘Ambler-esque’ and everyone knew exactly where ‘Greene-land’ was. Yet neither of these giants were a product of the period under scrutiny as they had cemented their reputations two decades previously, although both were still producing work of high quality, notably Ambler’s Passage of Arms (1959), The Light of Day (1962) – famously filmed as Topkapi, and The Levanter (1972); and Greene’s The Quiet American (1955), Our Man in Havana (1958), and The Comedians 1966). Their legacy and importance in the genre will be acknowledged, though not in enough detail to satisfy their dedicated fans. I have also relegated Leslie Charteris and Dennis Wheatley to the pre-war era for, although ‘The Saint’ was an immensely popular figure on British television in the early Sixties, Charteris had ceased to produce full-length novels and Dennis Wheatley’s novels in the period under scrutiny tended towards the historical or the occult stories with which he had made his name in the Thirties.

One limitation is not self-imposed, and that is the absence of women writers. Adventure thrillers and spy stories tended to be what is known in the book trade as ‘boys’ books’ or, pejoratively, ‘dads’ books’ and were to a very great degree, written by men – some might say men who had never grown out of being boys. A notable exception was Helen MacInnes, a Scot based in America, whose first novel had appeared in 1939. By the Sixties, she was a well-established and popular writer and had three notable bestsellers in that decade, but she, like Ambler and Greene, was not a product of that period when Britain ruled the thriller-writing waves and so gets an honourable, but passing, mention here. And it should not be forgotten that it was in the Sixties that some rather talented female writers, notably P. D. James and Ruth Rendell, were laying the groundwork for a revival in the British detective story and crime novel.

It is difficult to pin-point the exact end of this ‘Golden Age’ (or purple patch) of dominance by British thriller writers. One option would perhaps be the death of Alistair MacLean – the biggest name in the adventure thriller market – in 1987, or alternatively the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989, which threatened to put many a spy-fiction writer out of business. In truth, the writing was on the wall (if not the Berlin one) from roughly the mid-Seventies onwards as the Americans, slightly late as usual, entered the fray.

The beginning of the boom is rather easier to identify. The 1950s were grey and austere for a supposedly victorious wartime nation whose empire was starting to crumble. You might say Britain had been expecting you, Mr Bond …

Chapter 1: (#ulink_706eb4ec-ee61-545b-8160-6a267aaa4925)

A QUESTION OF EMPHASIS (#ulink_706eb4ec-ee61-545b-8160-6a267aaa4925)

You can smell fear. You can smell it and you can see it and I could do both as I hauled my way into the control centre of the Dolphin that morning. Not one man as much as flickered an eye in my direction … they had eyes for one thing only – the plummeting needle on the depth gauge.

Seven hundred feet. Seven hundred and fifty. Eight hundred. I’d never heard of a submarine that had reached that depth and lived.

Alistair MacLean, Ice Station Zebra

Was it a Golden Age or an explosion of ‘kiss-kiss, bang-bang’ pulp fiction which reflected the social revolution – and some would say declining morals – of the period? Both are reasonable explanations, depending on your standpoint, for the extraordinary growth in both the writing and reading of British thrillers, between 1953 and 1975.

Popular fiction, as opposed to literary or ‘highbrow’ fiction was always, well – popular; but suddenly the thriller seemed to be out-gunning all other forms. Writing in the middle of the Swinging Sixties, in his economic history Industry and Empire, the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm noted that since 1945, ‘that powerful cultural export, the British detective story, has lost its hold, conquered by the American-patterned thriller.’ Professor Hobsbawm was certainly correct in that the traditional British detective story had been replaced by the thriller as a cultural, and in fact economically valuable, export but wrong in suggesting they were ‘American-patterned’. This was a very British boom.

The British, or probably more accurately the English detective story had flourished in the period, roughly, between the two World Wars, a period which earned the epithet ‘Golden Age’ and was characterized, often unfairly, as the era of ‘the country house murder mystery’ or the ‘whodunit?’ It had given rise to the concept of ‘fair play’ whereby the reader was presented with clues to solving the puzzle presented, ideally before the fictional detective did, and the puzzle element was very important. There were even ‘rules’ (fairly tongue-in-cheek ones) on what was and was not allowed in a detective story, and a self-selecting, totally unofficial, Detection Club of the leading practitioners of the art to set the standards of good writing – or just standards in general.

After WWII tastes changed and readers began to demand something other than an intellectual puzzle. Cynics may say that the launch of the board game Cluedo in 1949 was an ironic final nail in the coffin of the ‘whodunit?’ – all those fictional cardboard characters being reduced to actual pieces of cardboard. Of course, it wasn’t the end; it was a period of cyclical dip and transition. Readers were looking for exotic settings, not country houses; heroes and heroines who often acted outside the law rather than plodding policemen; suspense rather than a puzzle; more realistic violence rather than a ridiculously over-elaborate murder method; and, above all, action and excitement at a time when, in the Sixties, everything seemed exciting and moved much faster.

For a period of more than two decades the British thriller delivered on all counts, and on a truly international level. It may not have been a Golden Age but it was certainly a boom time.

This is not a work of literary criticism or comparative literature; it is a reader’s history of one specific category, or genre, of popular fiction – the thriller – over a particular period when British writers dominated the bestseller lists at home and abroad. There will be little, if any, discussion of heroic mythology, social individualism, the atemporality of the appeal of the thriller, the symbiotic relationship between hero and conspiracy, or genre theory. Those debates are left to others on the grounds that, to paraphrase E. B. White: dissecting a thriller is like dissecting a frog – few people are really interested and the frog dies.

But there has to be some attempt to define the term ‘thriller’, a term used as loosely in the past as ‘noir’ is today (‘Tartan Noir’, ‘Scandi Noir’, etc.) to describe an important segment of that exotic fruit which is generally known as crime fiction. Whether it matters a jot to the reader who simply wants to be entertained is debatable, but again, it probably does. Crime fiction is a recognised genre, just as horror, science fiction, romance, fantasy, westerns and supernatural are all genres of popular fiction and genres tend to have dedicated followers.

The idea of genre fiction evolved in the late nineteenth century and blossomed in the Thirties with the advent of cheaper, paperback books with crime fiction among the first instantly identifiable genres thanks to the famous green covers used by Penguins and logos such as the Collins Crime Club’s ‘gunman’. Dedicated readers were steered to genres they liked and genre readers appreciated the guidance – though they did not want to read the same book again, they did want more of the same.

Within a genre as big as crime fiction, which could be described as a broad church (albeit an unholy one) readers tended to specialise often to a slightly frightening degree. There are those who only read spy stories (and some who only read spy stories set in Berlin), those who only read the Sherlock Holmes canon, those who refuse point blank to read anything written after 1945, those who only want to read about serial killers, those who always prefer the private eye novel, those who disparage the amateur sleuth preferring police detectives, and these days there are those naturally light-hearted optimistic readers of nothing but Scandinavian crime fiction.

Thankfully only a few crime fiction readers go as far as some science fiction fans and attend conventions dressed as their favourite fictional heroes but all like the security of identifiable categories and so some attempt must be made to define the terms used in this book.

As a recognisable genre, the thriller is certainly as old if not older than the detective story which, casually ignoring the interests of students of eighteenth-century literature and languages other than English, is generally dated from Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue in 1841. With reluctance, the honours could also go to America, with James Fenimore Cooper’s The Spy (1821) and The Last of the Mohicans (1826) for the earliest examples of the spythriller and the adventure thriller.

Already the dissection of the term ‘thriller’ has begun, yet by the time the British had flexed their writing muscles things were becoming clearer. Both Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883) and Sir Henry Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines (1885), published in the same decade in which Sherlock Holmes took his first bow, were fully-formed adventure thrillers. They were adventure stories which thrilled and distinctly different from the detective story, which could of course be thrilling but in a different, perhaps more cerebral, way. If that was not confusing enough, the 1890s saw the early days of the spy novel – albeit in the shape of a string of xenophobic potboilers which revelled in the fear of an invasion of England by Russia, France, or even Germany.

They were certainly meant to be thrilling, if not hysterical, but a quality mark was soon achieved with Erskine Childers’ The Riddle of the Sands (1903) and the work of John Buchan, seen by many as the Godfather of the quintessential British thriller, although he preferred the term ‘shocker’ presumably in the sense that his stories were electrifying rather than revolting.

When the Golden Age of the English detective story dawned, it suddenly seemed important that the thriller was publicly differentiated from the novel of detection which offered readers ‘fair play’ clues to the solution of the mystery, usually a murder. At least it seemed important to the writers of detective stories, who saw themselves as, if not quite an elite, then certainly a literary step up on the purveyors of potboilers and shockers.

The Golden Age can be dated, very crudely, as the period between the two world wars, beginning with the early novels of Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers (when it actually ended is still a matter of some debate – an often interminable and sometimes heated debate). Although a boom time for detective stories, it was also a boom time for spy thrillers. Donald McCormick in his Who’s Who in Spy Fiction (1977) claims that the years between 1914 and 1939 were the most prolific period of the spy thriller, the public’s appetite having been whetted by the First World War and real or imagined German spy-scares. ‘The spy story became a habit rather than a cult’ was his polite way of saying that this was definitely not a Golden Age for the thriller. Names such as Edgar Wallace, E. Phillips Oppenheim, Sydney Horler and Francis Beeding (Beeding’s books were publicised under the banner ‘Breathless Beeding’ or ‘Sit up with …’ after a review in The Times had declared that Beeding was an author whose books made ‘readers sit up [all night] until the book is finished’) are now mostly found in reference books rather than on the spines of books on shelves, whereas certain luminaries of the Golden Age of detective fiction, such as Christie, Sayers, Margery Allingham, Anthony Berkeley and John Dickson Carr are still known and respected and, more importantly, in print somewhere.

Back in the day though, the fact of the matter was that the Oppenheims and Breathless Beedings et al were the bigger sellers. Edgar Wallace’s publishers once claimed him to be the author of a quarter of all the books read in Britain (which even by publishing standards of hype is pretty extreme) and they were to inspire in various ways, often unintended, a new generation of thriller writers. In 1936, a debut novel, The Dark Frontier, arrived without much fanfare marking the start of the writing career of Eric Ambler, who was later to admit that he had great fun writing a parody of an E. Phillips Oppenheim hero.

Two decades later, the eagle-eyed reader of a certain age could spot certain Oppenheim traits in another new arrival, James Bond. In fact, the reader didn’t have to be that eagle-eyed.

The question of what was a thriller, and how seriously it should be taken, seemed to exercise the minds of the writers of detective stories and members of the elite Detection Club, confident in the superiority of their craft, rather than the thriller writers themselves.

One writer closely associated with the Golden Age, though happy to experiment beyond the confines of the detective story, was Margery Allingham. In 1931, Allingham wrote an article for The Bookfinder Illustrated succinctly entitled ‘Thriller!’ trying to explain the different categories then evident in crime fiction. It was a remarkably good and fair analysis of the then current crime scene, identifying five types (and one sub-type) which made up the family tree of the ‘thriller’, which were:

Murder Puzzle Stories – which could be sub-divided into (a) ‘Novels with murder plots’ by writers ‘who take murder in their stride’ (such as Anthony Berkeley), and (b) ‘Pure puzzles’ such as those by Freeman Wills Crofts;

Stout Fellows – the brave British adventurer or secret agent, usually square-jawed and later to be known as the ‘Clubland hero’ type (as written by John Buchan);

Pirates and Gunmen – the adventurers and gangsters as found in the books of American Francis Coe and the prolific Edgar Wallace;

Serious Murder – novels such as Malice Aforethought by Francis Iles (Anthony Berkeley) which Allingham put ‘in the same class as Crime and Punishment’;

High Adventures in Civilised Settings – crime stories ‘without impossibilities and improbabilities’ for which she cited Dorothy L. Sayers as an example.

Whether Dorothy L. Sayers was pleased with this somewhat lofty and isolated categorisation is not recorded, but it is likely that she bridled at being lumped, even in a specialised category, in the general genre of thrillers. She was crime fiction reviewer for the Sunday Times in the years 1933–5 and was not slow off the mark to say that a novel she did not approve of had ‘been reduced to the thriller class’. Responding to a claim, real or imagined, that she had been ‘harsh and high hat’ about thrillers, she claimed to hail them ‘with cries of joy when they displayed the least touch of originality’, whenever she found one that is, which seemed to be rarely and she clearly felt the detective story the purer form. (This in turn provoked the very successful thriller writer Sydney Horler, creator of ‘stout fellow’ hero Tiger Standish, to remark rather acidly that Miss Sayers ‘spent several hours a day watching the detective story as though expecting something terrific to happen’.)

In fairness, during her time as the Sunday Times critic, Sayers did attempt to provide a working definition of what a ‘thriller’ was and how it differed from the (in her opinion) far superior detective story. Indeed, she had three goes at doing so, which suggests the lady might have been protesting a little too much.

In June 1933 she suggested: ‘Some readers prefer to be thrilled by the puzzle and others to be puzzled by the thrills.’ She refined this in January 1934 to: ‘The difference between thriller and detective story is one of emphasis. Agitating events occur in both, but in the thriller our cry is “What comes next?” – in the detective story “What came first?”. The one we cannot guess; the other we can, if the author gives us a chance.’

Now Sayers believed in writing detective stories to a set of rules which gave the reader the chance, if they were clever enough, of guessing the solution to the mystery/problem posed before the author revealed the solution. She did not realise that there were readers out there who did not want the author to give them a chance, they just wanted to be thrilled however outrageous and implausible the story.

Sayers had a third go, in her Sunday Times column in March 1935, where she defined the thriller as something where ‘the elements of horror, suspense, and excitement are more prominent than that of logical deduction’. By that time an intelligent woman such as Sayers must have realised that the fair-play, by-the-rules detective story as an intellectual game was running out of steam and that other types of crime fiction were taking over. She herself effectively retired from crime writing after 1937.

Margery Allingham, who by her own set of definitions wrote most types of thriller, continued writing until her death in 1966 and kept a watchful eye on developments in the genre as a whole. In 1958 she was still wary of the superior status given to the detective story noting that ‘In this century there is a cult of the crime story as distinct from any other adventure story (thriller) – mainly read by people ill in bed.’

Allingham’s gentle analysis was that the detective story had been an intellectual exercise, whereas the thriller had included adventure stories, almost modern fairy stories – by which she presumably meant Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels. Now there was the crime story (in which she included the works of Georges Simenon and John Creasey) and the mystery story, a loose term which covered everything from the Gothic to the picaresque. In 1965, shortly before her death, like Sayers she predicted that the mysterystory was ‘going out’ and would be replaced by the novel of suspense.

To further confuse matters, in 2002 in The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Modern Crime Fiction compiled by Mike Ashley (one of the most respected anthologists in the business) Ashley excluded thrillers from his truly mammoth work on the grounds that ‘whilst some crime fiction may also be classed as a thriller, not all thrillers are crime fiction’. For his purposes, Ashley defines crime fiction as a book which involves the breaking and enforcement of the law, which is fair enough, but then he also excludes spy stories and novels of espionage – on the grounds that they constitute such a large field they deserve a study in their own right and even though spying usually involves breaking someone’s laws.

Even excluding thrillers and spy stories, as well as stories involving the supernatural or psychic detectives and anything labelled ‘suspense’ or ‘mystery’ (when describing the mood rather than content of a story), and then only dealing with authors writing since WWII, Ashley’s splendid encyclopedia weighs in at almost 800 pages.

Does any of this soul-searching by people in the business (writers, editors, reviewers) over terminology really matter? Because the field of crime fiction, or what the Victorians would have called ‘sensational fiction’, is now so large – so popular – it probably does, at least if one is trying to make a point about a particular aspect or time period.

To keep it simple, let us say that the overall genre of crime fiction encompasses crime novels (which contain danger, a puzzle or a mystery centred on an individual or individuals, the outcome of which is resolved by more or less lawful means by characters who are usually law-abiding citizens or officers of the state) and thrillers where the perceived threat is to a larger group of people, a nation or a society and a solution is reached by heroic action by individuals taking action outside the law, usually having to deal with extreme physical conditions or an approaching deadline.

Paraphrasing Dorothy L. Sayers, in the crime novel it is what happened in the past (who did the murder? what motive did the murderer have? how did a particular cast of characters happen to come together?) which is important; in the thriller it is what is going to happen next.

A good dictionary will define a thriller as a book depicting crime, mystery, or espionage in an atmosphere of excitement and suspense, which could, of course, also define the crime novel – accepting that espionage is a crime, or it certainly is if you are caught. So perhaps, to quote Sayers again, it is all a question of emphasis. In the crime novel the emphasis is on the crime and its consequences. In the thriller the emphasis is on thwarting or escaping the crime or its consequences and the thriller usually requires a conspiracy rather than a crime.

P. G. Wodehouse is reputed to have called readers of thrillers ‘an impatient race’ as they long ‘to get on with the rough stuff’ and rough stuff, or action, is certainly more predominant in the thriller, often taking place in a hostile environment – at sea, under the sea, in the Arctic, or under a pitiless desert sun, sometimes cliff-hanging from the edge of a precipice. In keeping with Edgar Wallace’s ‘pirate stories in modern dress’ description (of which Margery Allingham would have approved – she was keen on pirates and treasure hunts), the exotic foreign location became a popular trait of the British thriller. More than that, it became a major component and though it would be too simplistic to say that crime novels happened indoors whilst thrillers happened outdoors, the concentration on action and ‘rough stuff’ thrills did often require a large, open-air canvas.

If the key building blocks of crime fiction are: plot, characters, setting, pace, suspense and humour (the latter may come as a surprise, but there is a long tradition of humour in British crime writing going back to the days of Wilkie Collins), then one can logically assign large blocks of plot, character, and suspense and smaller characteristics of setting, pace, and humour to the crime novel whereas the thriller’s foundation might be huge blocks of plot, setting, and pace, with smaller proportions of bricks devoted to characters and suspense and sometimes no humour at all. (Ian Fleming disapproved of the use of humour in thrillers, though many other writers found room for a wise-cracking hero.)

Once again, it comes down to a question of emphasis.

For the period under review here – 1953 to 1975 in Britain – our basic division of crime fiction into crime novel and thriller is a starting point only. Any assessment of crime fiction over the period 1993 to 2015, for example, would certainly require a different schema and to cover the entire history of crime writing just in Britain would produce a family tree with so many sprigs and branches it would resemble a Plantagenet claim to the throne.

Such an exercise would be an interesting challenge, but this is not the place. Even so, we must divide our sub-genres into sub-sub-genres, but hopefully not too many. If we can accept that the crime novel is an identifiable entity, and that we know one when we read one, then it is reasonably safe to assume that we can all recognise Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express as a crime novel, but Ian Fleming’s From Russia, with Love, which involves at least two murders on the Orient Express, as something else – it’s a thriller.

In another example of compare-and-contrast, 1954 saw the publication of two novels which were both initially billed by their publishers as ‘adventures’. The Strange Land by Hammond Innes had a lone hero figure in an exotic location (Morocco) struggling with a shipwreck, arid desert and mountainous terrain. Live and Let Die by Ian Fleming had a lone hero in an exotic location (America and the Caribbean) battling gangsters and communists as well as Voodoo and sharks. Both were clearly thrillers, but different types of thriller. The Innes was an adventure thriller, for want of a better term, and the Fleming was a spythriller, albeit featuring a hero who did little actual spying and who acted more as a secret policeman,

and not a particularly secret one at that.

Ten years later, that distinction was redundant as a new, more realistic type of spy story began to appear. Live and Let Die may have been one sort of spy thriller but The Spy Who Came in from the Cold was obviously of a different ilk.

For the purpose of this survey, the novels under discussion – all thrillers – can be counted as adventure thrillers (for example, the work of Hammond Innes and Alistair MacLean), and, following the suggestion of Len Deighton, spy fantasy (for example, Ian Fleming and James Leasor) and the more realistic spy fiction (John Le Carré, Deighton, Ted Allbeury).

What makes a good, or bestselling, thriller is anyone’s opinion or guess; there is no set formula though at times it seemed that writers assumed there was. The best thought, if not the last word, on this goes to Jerry Palmer in his 1978 study Thrillers: Genesis and Structure of a Popular Genre: ‘I would say that thriller writing is like cookery: you can give exactly the same ingredients, of the highest quality, to two cooks and one will make something so delicious that you gobble it, the other something that is just food.’

Whatever the quality of the cooking, between 1953 and 1975 Britain’s thrillers certainly fed their readers well. From the dour and austere Fifties, through the fashionable ‘Swinging’ Sixties and into the more severe Seventies, British thriller writers saved the world on a regular basis and in the process achieved fame and fortune, making some of them the pop idols or football stars of their day.

Chapter 2: (#ulink_13c8b815-6a62-500d-b8a8-f0af1f6dc0b2)

THE LAND BEFORE BOND (#ulink_13c8b815-6a62-500d-b8a8-f0af1f6dc0b2)

The Fifties was the decade when Britain had to come to terms with being ordinary. It had emerged from the Second World War as a hero, but an exhausted and almost bankrupt hero. Austerity was Britain’s peculiar reward for surviving WWII unbeaten at the cost of selling her foreign assets and taking on a crippling load of debt to the United States.

Economically, Britain had been stretched to the point of snapping and it could no longer rely on its Empire for financial support, as it had relied on it for fighting men during the war – a vital contribution without which the outcome may have been different. British overseas assets in 1938 were estimated as being worth £5 billion, but by 1950 had been reduced to less than £0.6 billion and the countries of the Empire had already begun to cut their historic bonds with the mother country. This would not, or should not, have come as a surprise to anyone as independence or ‘home rule’ for many of the colonies, most significantly India, had been suggested or agreed during the war itself. There was also the plain fact that, whilst coping with its debt and a domestic programme creating a welfare state and a National Health Service, Britain could simply not afford the running costs of an Empire any more.

Britain was no longer the global power it had once confidently assumed it always would be and was now running, or perhaps limping, in third place behind the USA and Soviet Russia in any international race. On the home front it struggled simply to get by, a depressing state of affairs for a country which thought it had won the war. Even seven years after the end of hostilities, basic foodstuffs were in short supply (sweets and sugar rationing ending in 1953), there were uncleared bomb sites in many cities and government restrictions on building materials for anything other than housing meant that many buildings including the morale-boosting British pub were at best badly run-down, at worst still bombed-out shells. Until 1952, Britons were required to carry Identity Cards, something perceived (still) as a very un-British, ‘foreign’ affectation unless there was a war on and in 1953, to add insult to injury, the England football team was soundly thrashed 6–3 by Hungary at Wembley Stadium and a new, small family car called a Volkswagen Beetle was being imported from, of all places, Germany.

It may have been a scarred country stumbling to find its place in a reshaped world, but it was not all gloom. In 1953 Mount Everest was finally conquered (technically by a New Zealander and a Nepalese, but it counted as a ‘British’ achievement). The number of television sets increased to two-and-a-half million (from around 300,000 in 1950) so that an estimated twenty million proud Britons could watch the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, and two young scientists at Cambridge, James Watson and Francis Crick, discovered something called ‘DNA’. And on 13 April, a thriller called Casino Royale was published.

It marked, according to the critic Julian Symons, ‘the renaissance of the spy story’ and it unleashed the character of James Bond on an unsuspecting world. Prior to 1953, new fictional heroes had been compared to Richard Hannay, Bulldog Drummond, or Jonah Mansel, the ‘Terrible Trio of popular fiction between the two wars’ (as created by John Buchan, ‘Sapper’ and Dornford Yates).

One could add Leslie Charteris’ Simon (the Saint) Templar to this list; but now Bond was the new standard.

Casino Royale, Pan, 1955, illustrated by Roger Hall

Bulldog Drummond, Hodder & Stoughton, 1920

Before Bond, heroes had been upright, square-jawed, patriotic, honourable, and always kind to women, dogs, and horses, though not necessarily in that order. If a John Buchan hero had a gun in his hand it was usually because he was striding through the heather of a Scottish grouse moor – and the same could be said of the heroes of Geoffrey Household’s thrillers of the early Fifties, substituting a Dorset heath for Scotland. Any game that James Bond was hunting with a gun was invariably human and he did not really seem to care too much if an innocent bystander got in the way, and whilst avid fans of E. Phillips Oppenheim and Peter Cheyney would feel right at home with the descriptions of luxury living and thick-eared violence, there was no doubt that Bond was something different.

Unlike the grey and shady worlds created before the war by those masters of the more ‘realistic’ spy novel, Graham Greene and Eric Ambler (and indeed W. Somerset Maugham in his influential 1928 ‘novel of the secret service’ Ashenden – or The British Agent), Fleming had created a Technicolor dream land littered with fast cars, trips abroad, good food, fine wines, and beautiful women. It was just the sort of fantasy needed to brighten the monochrome Fifties landscape.

Confident that he had written a successful thriller, Fleming himself indulged in a bit of fantasy. He bought a gold-plated typewriter and then requested a first print run of 10,000 copies from his publisher. The publisher, Jonathan Cape, took this request from a debut author as seriously as any publisher ever takes a request from a writer and printed half that quantity. That first run sold out in under a month and Fleming was left grinding his teeth when a second print of only 2,000 copies went equally quickly.

However shaky, to Fleming, was the start for Casino Royale (though many a contemporary crime writer would be very pleased, in fact rather smug, with that initial hardback print run), it has been estimated that within five years, once the Pan paperback edition had appeared in 1955, a million Britons had bought Casino Royale, though fewer than one in 10,000 would ever visit a casino.

They did not have to: the fact that James Bond was quite at home in a casino or a five-star hotel, or on a transatlantic jet-liner or a beach in Jamaica, was fantasy enough for most readers in those austere times.

There was another male fantasy which James Bond provided in satisfying quantities in comparison with what had gone before: sex. Kingsley Amis put it succinctly thus: ‘No decent girl enjoys sex – only tarts. Buchan’s heroes believed this. Fleming’s didn’t.’

It may seem that James Bond provided everything readers, at least male ones, desired that they were denied in real life: sex, travel, luxury branded goods, un-rationed foods, alcohol, sadistic villains and guns to battle them with, cars, and all with an impressive salary of £1,500 a year, as well as a small private income, as revealed in Moonraker. (Bond’s boss, ‘M’, by the time we get to On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, received a staggering £5,000 a year, almost as much as a Chancellor of the Exchequer.) Which red-blooded male would not want to be James Bond (perhaps without the famous Casino Royale carpet-beater torture scene), let alone read about him?

Yet in the overall thriller market, Bond did not have it all his own way, far from it. Fleming himself took a keen interest in how his rivals in the bookshops were doing and in 1955 undertook a piece of undercover work, wining and dining an executive from a rival publisher, Collins. He was somewhat chastened to learn that the books of the leading writer of adventure thrillers, Hammond Innes, were regularly selling between 40,000 and 60,000 copies in hardback and were already proving successful as Fontana paperbacks.

They were to be even more successful in the next decade, despite the fact that they contained no sex or sadism and relatively little violence. Innes’ heroes were anything but supermen, rather they were invariably honest, decent, and upright citizens. They certainly did not have expensive tastes in wine, food, or clothes and were more likely to be found driving a bulldozer or a snow plough than a supercharged Bentley (though Hammond Innes’ books always supplied a touch of the exotic through their settings). The reader could always rely on Innes for an exciting scene or two involving skiing or sailing, usually in extreme weather conditions, and travel to a foreign land unfamiliar to most readers. The Strange Land, published in 1954, was far from one of Innes’ best adventures but it was set in Morocco, a country which today is considered a tourist destination only a three-hour-flight away but for most readers back in 1954 must have been as mysterious as Conan Doyle’s The Lost World.

There was also competition from other thriller writers who were now seasoned veterans. Dennis Wheatley, who had briefly worked with Fleming on deception initiatives during the war, was exorcising his two favourite demons in the shape of communism in Curtain of Fear and Satanism in To the Devil – A Daughter. That other stalwart of the thriller genre, Victor Canning, who like Wheatley and Innes had first been published before 1939, was also enjoying considerable success. Three of his thrillers – The Golden Salamander, Panthers’ Moon and Venetian Bird, set in Algeria, the Swiss Alps, and Venice respectively – had been filmed between 1950 and 1952, with reliable British stars such as Trevor Howard and Richard Todd. In 1953, arguably Canning’s best spy story A Forest of Eyes was published as a Pan paperback. Set in Yugoslavia, this book was clearly influenced by Eric Ambler’s 1938 thriller Cause for Alarm set in Italy (Canning and Ambler were wartime pals), which also, coincidentally, became a Pan paperback in 1954.

A Forest of Eyes, Pan, 1953

Campbell’s Kingdom, Fontana, 1956

Paperback editions were becoming an important factor in the thriller market, both in style and volume. The Pan edition of Canning’s Venetian Bird had a ‘film tie-in’ style cover (though an illustration rather than a still photograph from the film) clearly showing Richard Todd in the lead role. The later Fontana paperback of Hammond Innes’ Campbell’s Kingdom similarly referenced the 1957 film, with an illustration of star Dirk Bogarde. On the crime fiction front, Penguin had shown what could be done in terms of volume by launching an author as a ‘millions’ author, starting in 1948. Prolific crime writers such as Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Margery Allingham and John Dickson Carr would have ten titles issued simultaneously, each with a print run of 100,000 green-jacketed copies, making a million paperbacks per author.

Cheap paperbacks may well have ‘democratised literature’ and even, in lieu of a shrinking Empire, spread British values across the world

but they were not the only source of popular fiction. Between 1949 and 1959, the number of books in public libraries increased from forty-two million to seventy-one million, and an estimated 70 per cent of borrowings were thought to be fiction

which naturally gave rise to grumbling in some quarters that ‘fiction on the rates’ was not a good use of public finances. It was hardly a subversive socialist plot as much of the library expansion came under Conservative governments, perhaps to help convince voters that they had never had it so good and as more than a quarter of the British population had a library card, it was a constituency too large to ignore.

Not all libraries were in the public sector: there were commercial subscription libraries such as the Boots Booklovers Library in branches of Boots the High Street chemist. Established in 1898, the BBL attracted one million subscribers during World War II and, by 1945, Boots were buying 1.25 million books a year, but the decline set in during the Sixties with the boom in paperbacks and the Boots operation closed in 1966. A similar fate awaited the W. H. Smith Lending Library which had opened in 1860 and had specialised in crime and romantic fiction initially for railway passengers. It issued its last borrowings in 1961, though some subscription libraries attached to large department stores did continue to service loyal customers into the Nineties.

For those thriller addicts who could not wait for the paperback of a favourite author’s latest, usually a minimum wait of at least two years in the Fifties (often three, sometimes five), a number of book clubs started up offering cheaper hardback editions to members who usually subscribed to a set number of titles per year, one of the earliest being the Thriller Book Club. These clubs were to flourish in the Sixties, often producing their own promotional catalogues and developing stylish artwork for the jackets. They attracted the biggest-selling authors of the day and continued into the 1980s.

From 1956 onwards, starting with Live and Let Die, Fleming’s Bond novels also appeared in cheaper editions published by The Book Club (established by Foyles, the bookseller), usually a year after the first hardback editions and a year before the paperback. The Bond novels also began to be serialised in national newspapers – an increasingly important promotional tool for books, as not only did more people use libraries in the Fifties, they also read more newspapers. From Russia, with Love was the first, serialised in the Daily Express in 1957 at the time the book was published (a comic strip version was to follow in 1960) and this undoubtedly helped sales.

Fleming’s publishers (Jonathan Cape) were confident enough to have produced an initial print run of 15,000 copies of From Russia, with Love and it is difficult now, knowing how famous the title became, to understand how the book could not have been the top-selling thriller of 1957. The problem was that Bond was being out-gunned and out-actioned – if not ‘out-sexed’ – by another sort of thriller. The Guns of Navarone, a rousing, wartime adventure thriller and the second novel by a newcomer called Alistair MacLean, reputedly sold 400,000 copies in its first six months.

MacLean was just one of several new thriller writers to make their mark in the decade of James Bond’s creation – along with such as Francis Clifford, Berkely Mather, John Blackburn and Desmond Cory (who does have something of a claim to having beaten Fleming to producing the first ‘licensed to kill’ secret agent). None were, in the long run, likely to seriously compete with Fleming and Bond, but for a while, MacLean certainly did. However, once Fleming’s books started to be filmed (something Fleming had been very keen on from the start – perhaps, as it turned out, too keen), Bond’s iconic status was assured of immortality.

Fantasist though he might have been, even Ian Fleming could not have seen the future and the scale of the industry his creation would become, but he did have the wit to acknowledge the man who had shaped the more realistic modern spy thriller: Eric Ambler.

As James Bond faces execution at the hands of assassin Red Grant across a compartment on the Orient Express in one of the most famous scenes in From Russia, with Love, both men have books to hand. Grant has a copy of War and Peace which is actually a cunningly-disguised pistol (Bond has given his own gun to Grant, proving perhaps that he wasn’t always the sharpest throwing-knife in the attaché case) but Bond has a copy of Eric Ambler’s The Mask of Dimitrios, into the pages of which he slips his gunmetal cigarette case. When the assassin shoots, Bond whips the armour-plated book over his heart and stops the fatal bullet.

It would be stretching a point to say that without Eric Ambler there would have been no James Bond, as Fleming took his inspiration from a more fantastical school of ‘blood and thunder’ thrillers and played up the fantasy element, rather than down. But in one way one could have said in 1957 that without Eric Ambler there would have been no more James Bond …

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/mike-ripley/kiss-kiss-bang-bang-the-boom-in-british-thrillers-from-casino/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Mike Ripley

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Справочная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1841.75 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: WINNER OF THE HRF KEATING AWARD FOR BEST NON-FICTION CRIME BOOK 2018An entertaining history of British thrillers from Casino Royale to The Eagle Has Landed, in which award-winning crime writer Mike Ripley reveals that, though Britain may have lost an empire, her thrillers helped save the world. With a foreword by Lee Child.When Ian Fleming dismissed his books in a 1956 letter to Raymond Chandler as ‘straight pillow fantasies of the bang-bang, kiss-kiss variety’ he was being typically immodest. In three short years, his James Bond novels were already spearheading a boom in thriller fiction that would dominate the bestseller lists, not just in Britain, but internationally.The decade following World War II had seen Britain lose an Empire, demoted in terms of global power and status and economically crippled by debt; yet its fictional spies, secret agents, soldiers, sailors and even (occasionally) journalists were now saving the world on a regular basis.From Ian Fleming and Alistair MacLean in the 1950s through Desmond Bagley, Dick Francis, Len Deighton and John Le Carré in the 1960s, to Frederick Forsyth and Jack Higgins in the 1970s.Many have been labelled ‘boys’ books’ written by men who probably never grew up but, as award-winning writer and critic Mike Ripley recounts, the thrillers of this period provided the reader with thrills, adventure and escapism, usually in exotic settings, or as today’s leading thriller writer Lee Child puts it in his Foreword: ‘the thrill of immersion in a fast and gaudy world.’In Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang, Ripley examines the rise of the thriller from the austere 1950s through the boom time of the Swinging Sixties and early 1970s, examining some 150 British authors (plus a few notable South Africans). Drawing upon conversations with many of the authors mentioned in the book, he shows how British writers, working very much in the shadow of World War II, came to dominate the field of adventure thrillers and the two types of spy story – spy fantasy (as epitomised by Ian Fleming’s James Bond) and the more realistic spy fiction created by Deighton, Le Carré and Ted Allbeury, plus the many variations (and imitators) in between.