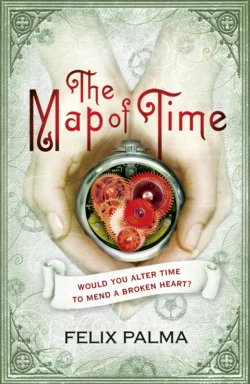

The Map of Time and The Turn of the Screw

Генри Джеймс и Felix Palma

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 625.04 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: An epic, ambitious and page-turning mystery that will appeal to fans of The Shadow of the Wind, Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell and The Time Traveller’s WifeLondon, 1896. Andrew Harrington is young, wealthy and heartbroken. His lover Marie Kelly was murdered by Jack the Ripper and he longs to turn back the clock and save her.Meanwhile, Claire Haggerty rails against the position of women in Victorian society. Forever being matched with men her family consider suitable, she yearns for a time when she can be free to love whom she choses.But hidden in the attic of popular author – and noted scientific speculator – H.G. Wells is a machine that will change everything.As their quests converge, it becomes clear that time is the problem – to escape it, to change it, might offer them the hope they need…