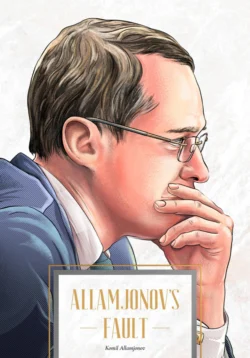

Allamjonov′s fault

Komil Allamjonov

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на русском языке

Стоимость: 299.00 ₽

Статус: Нет в наличии

Издательство: Автор

Дата публикации: 26.08.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The book you are holding in your hands contains the story so far of my not-quite-yet long life. It is not a work of fiction nor is it intended as a treatise. If a young person reads this book and finds even the slightest motivation in it, it will only make me happy. And if you find some mistakes (spelling, stylistic, etc.), don′t judge me too harshly. While working on the book, we had our fair share of differences of opinion. In my own personal opinion, if someone has a pure heart and pure intentions, then Allah will protect him or her.Books like this one should be commonplace and not sensational; our country ought to produce many such works. And if we do manage to inspire someone to read it, despite our fears about publishing books in this novel format, then we′ll just keep on in the same vein. Many times in my life, I have relied on Allah and achieved that which I set out to do. As I intend to do the same on this occasion, it means that whatever happens was always destined to be.