Invictus

Invictus

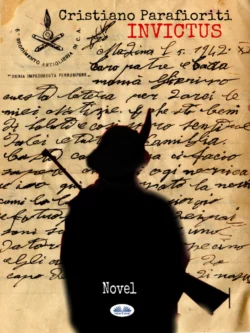

Cristiano Parafioriti

The epic story of Ture Di Nardo, known as “Pileri”, a young Sicilian peasant torn away from his family and his woman by the call to arms during the Second World War.

Enlisted in the Alpini and part of the Julia Division, he followed the bitter fate of the Italian Army in Russia in what was to be the biggest Italian military defeat of the 20th century.

Like a new Ulysses, the young Ture Pileri will have to face terrible trials on the long journey home.

With this engaging historical novel, Cristiano Parafioriti brings to light a real story that has been kept in the heart of its protagonist for seventy years. The strength of a man, driven by love, able to resist and react to the defeat of an entire army.

Sicily, April 1941. In San Giorgio, a small village in the Nebrodi mountains, live the Di Nardo family, known as the “Pileri”, a humble family that supports itself through agriculture and sheep farming. The head of the family is Zi Peppe, married to Za Nunzia, with whom he has seven children. Ture, the eldest, is twenty years old and has only managed to escape being called up to arms thanks to his father’s connections and can therefore continue to provide for the family. One evening, on his way to fetch water from the trough with his sister Concetta, the latter reveals to him the love interest of his cousin Lina. Ture does not reciprocate the young woman’s feelings, but on that occasion, he is struck by the beauty of Lina’s younger sister, Rosa. A few days later, Ture declares his love for her, and Rosa confesses that she, too, has secretly loved him for more than a year. Their passion immediately blows up, but the joy is short-lived: the war outcome takes a turn for the worse, and a new, irrevocable call to arms arrives. Zi Peppe can do nothing this time. His son must leave for the front. The family loses his strong arms while Rosa the newborn bud of love. Here begins the epic of Ture. Ripped from his family and his woman, enlisted in the Alpini and part of the Julia Division, he followed the bitter fate of the Italian Army in Russia in what was to be the biggest Italian military defeat of the 20th century.

Like a new Ulysses, the young Ture Pileri will have to face terrible trials on the long journey home that will end on 23 September 1943. On that night, Ture arrives exhausted on the Nebrodi under Rosa’s house, who runs into his arms. The two lovers, after many adventures, meet again to never leave each other again. A festive procession then escorts the young survivor to San Giorgio, to his family. Unconquered by the war. Unconquered by the Russian winter. Unconquered by the Nazi fascists. Unconquered by the Americans. Ture Pileri can finally embrace the rest of his family and get on with his life. Invictus. Ture Pileri will die in 2018, at the age of 97, surrounded by the love of Rosa and the affection of his large family. A real story, kept in the heart of its protagonist for eighty years. The strength of a man, driven by love, capable to resist and react to the defeat of an entire army.

Invictus

Cristiano Parafioriti © 2021

Cover photo

Anna Francica

Layout and editing

Stefania Salerno

CRISTIANO PARAFIORITI

INVICTUS

NOVEL

With an introductory essay by Antonio Baglio

Translated by Giovanna Bongiovanni

TABLE OF CONTENT

AUTHOR’S NOTE (#ulink_2e0c1183-7c50-58fe-a2a3-01f25bc68ade)

INTRODUCTORY ESSAY

PART I (#ulink_8dd99079-1ff5-596a-aa94-601bfa04c9f9)

I

II (#ulink_2b9ca7d6-6f23-5a8e-969e-8e75a2798643)

III (#ulink_54100be0-ea24-51db-813b-6f167bdee003)

IV (#ulink_ab0cd5d8-cc1f-5a7c-80c5-cf85ad81a78c)

V (#ulink_938c0dcc-a651-5d09-9cc5-c1011831df78)

VI (#ulink_3b4546ac-6a57-5674-9d5c-0a8c0ecc3e12)

VII (#ulink_5a7b207a-f3c1-5092-943b-aa68dcf2a438)

VIII (#ulink_8e8666ce-657d-5a34-b972-9dea2ac56ec4)

IX (#ulink_3e9e2e1d-8928-5361-8c93-fdf37df440b1)

PART II (#ulink_fca2fa37-d01d-5376-abd8-767c58e0162e)

I

II (#ulink_90211444-36d0-5def-abd4-c96b8f3b13a7)

III (#ulink_1b31961d-1033-500c-ae56-e248869cd53f)

IV (#ulink_a17bd17d-f077-59f2-9a7a-21f7fb472449)

V (#ulink_c71623a9-047a-51c1-8440-9c50f015741e)

VI (#ulink_54a73027-72bd-5df7-85fe-5c59eb257901)

VII (#ulink_61903bbf-c6d0-5880-9d91-d038b376b34e)

VIII (#ulink_e687f8ee-7c91-5c1c-87be-6402cb71330c)

IX (#ulink_c7d0c249-9f0d-5fee-8eae-fe79d8ea7b4a)

X (#ulink_5d0005af-f2e6-5742-a75e-360e523c29b5)

XI (#ulink_1f29ef69-7518-5d72-9239-48a046d0baad)

XII (#ulink_1b57f24d-916a-5bbf-91ce-bf06028fe000)

XIII (#ulink_839c91fe-fb67-5374-9941-34ddb5fc7e71)

XIV (#ulink_10132894-1d5e-58bf-be45-494d6e2d76a9)

XV (#ulink_e3960197-31df-5013-ae20-b914ffeb0092)

XVI (#ulink_e1d2a4fa-b40e-5867-bbbe-9dbdf834645d)

XVII (#ulink_419549fb-f38a-5df0-aa99-72b41a020ff4)

XVIII (#ulink_edd54dc1-d49c-59a4-a3ad-4bf416e8b450)

PART III (#ulink_58791234-ace2-56f0-82d0-003edc0841f5)

I

II (#ulink_339169e3-c6e3-5fd0-94a2-922132d3a18c)

III (#ulink_caa6cec1-00f8-5239-9d24-fc65243fc85d)

IV (#ulink_dfd77ea8-22e4-50cb-b59a-70f7ba2cfa59)

V (#ulink_fdf9d87a-32f1-5af3-90c2-f64dee7b5528)

VI (#ulink_8ed445d0-428a-5852-a090-92c0b96895c1)

VII (#ulink_58c8cdb2-a883-5475-a74e-4636085cbc67)

VIII (#ulink_3fc14927-9c62-5010-b09f-bf2d42ff3d9d)

NEMESIS (#ulink_d4e3504c-e2f2-5828-a4be-efcb61811b92)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (#ulink_85811604-2ef0-5cba-a1fb-0863a9eaa839)

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds and shall find me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate,

I am the captain of my soul.

(Invictus, William Ernest Henle (https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Ernest_Henley)y)

To Don Ture Di Nardo “Pileri”

to my grandfather Calogero Barone “Ccanino”

to all veterans

and to those who have never returned

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Nino Amadore, my friend and esteemed journalist of “Il Sole 24 Ore”, wrote in one of his articles: “Cristiano Parafioriti is the founder of a new literary genre, Sicilian minimalism, where the stories of a country and its people become the stories of the whole world”.

I jealously guard this definition in my memory and heart, and the more stories I write, the more I find myself in those words.

My work is born in my small and beloved village, Galati Mamertino, a mountain village perched on the Nebrodi mountains in Sicily. Galati is a melting pot of many other tiny places and many other realities that shine with their own light, each with stories to tell, with their people, with their own myths.

This novel was born from one of these magical corners, San Giorgio, a remote and by now an uninhabited village, of which today only a few abandoned ruins remain.

I believe that some stories come looking for you. Writers often live in a state of almost lethargy, and, suddenly, something awakens them from this sweet wandering. And so it happened that on a hot day in August 2019, Salvatore Di Nardo, the homonymous nephew of the main character of this story, woke me from my peaceful rest.

Salvatore, known as Salvo, has been living in Pisa with his family for years. He, too, is affected by the sicilitudine, a disease that makes us exiled children torn from our roots but always tightly linked to our native land.

I've known him since my days in the marching band when we both lived in the village. We had a good time between concerts, laughter, drinking and lots of friends. It was a lifetime ago.

For an unknown reason, I have always had a good feeling towards him, as if only beautiful things orbited around him. It is an irrational belief that comes out of my unconscious thoughts, so illogical that I feel it crystal clear! I am in this way. I follow instinct and live with passions.

Salvo told me that he wanted to publish on Facebook, through the successful Tuttogalatimamertino page, some videos about his grandfather, the homonymous Salvatore di Nardo (born in 1921), an Alpine in Russia with the Armir during the Second World War.

Nino Serio, the page administrator, raised some concerns as the material was complex and lasted more than three hours! It was a long interview with his grandfather about that tragic adventure, full of documentaries.

I could not stand that this story could end like this! It was the sparkle of that boy that did not give me peace. I suddenly felt within me a big craving to see that material, to know that story that had stayed buried for almost seventy years.

Those videos were like sparks that light a fire. The creative clapper set in motion, making my soul buzz. In me, the uncontrollable urge that I had already felt in my life and that I knew very well: to write.

I called Salvo Di Nardo.

“I’ll write a novel about it!” I told him point-blank.

He, touched, replied, “In my heart, that was what I wanted!”

This novel is, therefore, based on a true story. Nevertheless, some characters, organizations, and circumstances may be the fruit of the author's imagination or, if they exist, used for narrative purposes.

Almost.

INTRODUCTORY ESSAY

THE ITALIAN CAMPAIGN OF RUSSIA

OF 1941-1943

AND ITS MEMORY

I’ve still in my nose the smell of grease on a red-hot machine-gun. I’ve still in my ears and even in my brain the crunching of snow under my boots, the coughs and sneezes from Russian lookouts, the sound of dry grass swept by the wind on the banks of the Don. I’ve still in my eyes the stars of Cassiopeia which hung above my head every night, and the bunker props above my head every day. And when I think about it all I feel the terror of that January morning when their gun Katiuscia first let off its seventy-two rocket-shells.

This is the incipit of a famous autobiographical novel, The Sergeant in the snow, written by the Alpine Mario Rigoni Stern, soon destined to become the best-known literary testimony of the disastrous Italian campaign in Russia during the Second World War.

When, in June 1941, Hitler decided to wage war against the Soviet Union, triggering Operation Barbarossa, Mussolini responded by offering his willingness to support the German troops. The establishment of a Corps of Italian expedition to Russia (CSIR) left in mid-July for the eastern front under the orders of General Giovanni Messe.

The following year, combined with new corps in the Armir (Italian Army in Russia), it was deployed on the Don and couldn't resist the Soviet offensive that, between December 1942 and January 1943, would have decimated it. Numbers show the extent of the disaster.

Out of 230,000 Italians who left for the eastern front, one-third of these – about 95,000 – had lost their lives: dying in combat, dying of hardship and cold, during the retreat or the stages of transfer to the prison camps, sadly known as Davaj marches (from the term used to solicit the passage by the Russian escort soldiers). Without forgetting how many perished during the same imprisonment and the high number of those missing.

An event so fatal and fraught with consequences for thousands of Italian soldiers – swallowed up by the Russian steppe, plagued by tough Soviet resistance, as well as by adverse climatic conditions – and for their families, often destined to remain unaware of the fate of their relatives, ended up feeding a copious memoir, stimulated by the desire to account for a unique and devastating experience.

It is no coincidence that the Russian campaign – as the historian Maria Teresa Giusti, author of a valuable volume on the subject, pointed out – ended up as “one of the twentieth-century war events with the biggest impact on Italian collective memory”

.

A memory that is certainly uncomfortable, on the one hand, if we consider the fact that the war campaign was still an expression of the aggressive policy of Mussolini, but so disruptive due to the suffering and dramatic conditions of the retreat as to reveal the profound disillusionment with the regime. The bitter acknowledgment of the lack of training marked the participation of the Italian soldiers in the enterprise, which was opposed by the undoubted acts of heroism of those who were lucky enough to survive that terrible experience and return home. In this regard, it is interesting to re-read the authoritative testimony of another veteran, Nuto Revelli, among the first to denounce the dramatic conditions of the soldiers on the Russian front in his memorial writings:

Everything was unsuitable for the environment. Even the uniform, so green, made us targets. We had wagons of mountain warfare equipment, from ice crampons to avalanche ropes and rock ropes.

We were Alpine soldiers made for slow warfare, for walking. We had 90 mules for each company and four lorries for the whole battalion. Our weapons consisted of the Model 1891 rifle that had one advantage for its age: it was not muzzle loading. The equipment for the department was the Breda machine gun, which fired when well cleaned and oiled. We couldn’t, however, fire too many volleys, lest the barrel turned red, or the gun jammed, or fired on its own. The accompanying weapons – Brixia mortars, Breda machine guns, 81 mortars, and 47/32 cannons – were, for the most part, outdated and, in any case, not enough. Our only anti-tank weapon – the 47/32 cannon – could only pierce Italian tanks. Against Russian tanks, there was nothing to do.

Artillery in the divisional area consisted of museum equipment: the 75/13, the 100/17, utterly harmless and safe hand grenades, which did not always explode.

Means of a connection made for mountain warfare, unsuitable for long distances; the old faded flags, the heliographs, were of no use on that undulating terrain. The few radios, heavy and battered, were sometimes less fast than the order carriers.

No mines, no flares, no reticulates, no tracer bullets. And little ammunition, almost depleted.

The equipment was the same as on the Western Front from the battle of June 1940. Uniforms made of the worst wool, shoes of stiff, dry leather that looked like paper. The foot cloths seemed to have been made on purpose to block the blood circulation, favouring heating or freezing.

We were not tanks. We were mountain troops, poorly armed, poorly equipped for mountain warfare. Throwing ourselves into the plains, where armoured warfare was running fast, meant going in blind.3

Historiographical research confirmed it was a disaster. A disaster made worse by the grave shortcomings of the Italian army's war equipment and the laxity with which the military commanders and Mussolini approached the enterprise.

The Duce was sure that the war would be over soon, mainly due to the training and firepower of the German ally. Therefore, he had refrained from mobilising the country for the campaign – as had happened during the conquest of Ethiopia. The affair resulted in the worst collapse suffered by the Italian army.

To be fair, you must not overlook the fact that the image of the victimized condition of the Italian soldier, in the transmission of the memory and subsequent representation of the event, would have been overshadowed, concerning the criminal policy of the regime, the cruelty of the Red Army and the harsh weather conditions.

Not to mention the often-cited lack of support from the German ally: the offensive and not defensive nature of the war, the Italian army seen as a full-fledged invader against a country that tried to defend itself strenuously against the occupation policy pursued by the Axis powers.

Beyond the reasons and responsibilities for the conflict – to keep in mind to avoid supporting a distorted and “mythical” vision – memories of that traumatic war campaign had a powerful effect on the survivors’ minds, leaving us some of the most intense pages about the Italian war, full of strong impressions, pathos, horror, and titanism.

As Maria Teresa Giusti has also pointed out, it is no coincidence that the accounts relating to the military experience in Russia, within the framework of the memories of the Second World War, have been far more than all those dedicated to the other fronts.

The Russian campaign is the background of Invictus, a historical novel. The novel is the processing of the experience lived by a young Sicilian peasant, originally from a village in the Nebrodi municipality of Galati Mamertino, in the province of Messina, who went to war on the eastern front. We face a memory handed down from generation to generation, at first known only by the family, then entrusted – after a long period of detachment from those events and sedimentation – to the pen of a talented writer and fellow countryman, Cristiano Parafioriti. He managed to give vigour and substance to the narration of that extreme experience, to the point of making it an abiding testimony of the struggle of men to preserve their humanity in the face of the destructive horde and horrors of war.

In a grand choral fresco, the novel tells the story of a Sicilian farmhand, Salvatore, known as Ture, the eldest son of the Di Nardo family. Although his father, who had already experienced the tragedy of the Karst during the First World War, tried to save his son from this ominous prospect with various pressures and expedients, Ture could not avoid military service and be called up for war.

The fate reserved the worst of destinations for him: the Russian steppe.

Accustomed to sacrifices, to harsh winter in the mountains, shaped by the hard life in the fields, he managed to survive the rigours of a campaign, living in prohibitive conditions. And to return to his beloved land, not without further risks and adventures, knitting back the threads of affection that the war had threatened to interrupt forever.

Taken from the treasure chest of memory, in the frame of a historical novel that edits and enriches but does not alter the truth – if anything, in some cases, it transcends it – the story of the main character Ture Di Nardo becomes exemplary of the condition of many farmers. They often are the only support for their families but are torn away from their work and affections. They are thrown into a sort of no man’s land, the battlefield, dominated by anonymous and mass death, at the mercy of a war that brutalises and, in some ways, depersonalises them.

The narrative represents well the perspective from below, of those peasants from the most remote areas of the country suddenly catapulted into a hellish conflict, ruled by resignation and frustration and by a substantial indifference towards the reasons for the war, experienced at like a natural disaster. The protagonist’s attitude in the novel reflects the conditions of that rural world accustomed to patient sacrifice, which struggles to identify with the State and whose dimension still lived the local, municipal one. Far from the ideas of power and greatness promoted by the regime, averse to fascist myths, far from the exasperated patriotic spirit nurtured at that time, Ture found himself immersed in the tragic reality of the Italian war on the eastern front. The only comfort offered by solidarity with his comrades in arms and the faint hope of one day being able to return home to fulfil his love dream with his beloved Rosa.

The novel gives us an extraordinary cross section of the physical and mental universe, of the values, fears, needs, and aspirations of peasant families in a mountain area – the Nebrodi area: the hard work in the fields, made of toil, sweat, and abuses perpetrated by a class of landowners, of noble origin, who still in the first half of the 20th century firmly held possession of most of the land, profiting handsomely by renting it out, often with random criteria.

Parafioriti’s realist prose is fluid and easy to read, in the best Sicilian literary tradition. He thickens the narrative plot as he follows the development of the love affair between Ture and his cousin Rosa, with the twist of events and circumstances reminiscent of Manzoni that hinder its full completion.

He deals efficiently with the various characters, captured in their intimate essence, creating an impressive social fresco based on solid historical knowledge and appropriate use of language.

After the short stories of Era il mio paese (2014), Sicilitudine (2016), and the transition to the historical novel with D’Amore e di briganti (2019), set in the post-unification period of the nineteenth century, this new literary effort marks the author's arrival at a test of definite maturity, with an organic novel able to hold the reader's attention by the force of the story and its universal value. All Parafioriti’s writings have a common denominator, an unmistakable common thread: they express a deep connection with his homeland in Sicily, Galati Mamertino and its hamlet of San Basilio, on the Nebrodi mountains, which becomes an integral part of the characters the author narrates. From this context, the novel events unfold to fit into the broader framework of the history of the twentieth century.

In conclusion, it seems accurate to reflect on the genesis and scope of this work to recall the following observation:

“Every human being is unique, an unrepeatable being who, however much he may run about in the dark, mixing accidents with his intentions, never follows in the footsteps of another, never repeats the same path, never leaves behind the same story. This is another reason why life stories are told and listened to with interest, because they are similar and yet new, irreplaceable and unexpected, from start to finish.”

As Hannah Arendt pointed out, “no one has a life worthy of consideration of which a story cannot be told”

. By recounting the cruel reality of war, the author tries to emphasise and exalt the unparalleled nature of each human destiny but also the eternal, exceptional value of the testimony of suffering and dignity capable of overcoming the barrier of time and projecting itself into today’s world. In the hope that memory can always represent – in the words of Liliana Segre – a precious vaccine against indifference.

Prof. Antonio Baglio

(Università degli Studi di Messina)

PART I

I

Village of San Giorgio, April 1941

Nebrodi mountains

Zi

Peppe Pileri would go back from the countryside in the evening. The days were getting longer, and he tried to make the most of every last ray of sunshine. Thus, just before retiring, he would pluck the last dry twigs from the ground and pile them up in the corner with the rest, load up the sack with the day’s harvest, and, with a broom rope, put a few pieces of dry wood on the mule to fuel the fireplace.

It was early April, and the cold was still being felt, especially within the stone walls of the small village of San Giorgio, where Zi Peppe lived with his family. There, the gusts of mistral blew in the nights while the foxes and martens ate the chickens. There was starvation, and now there was also war.

Zi Peppe Pileri had to provide for his family, consisting of seven children, and there was never enough bread. He always said that he believed in God for heavenly things, but with earthly things, he needed luck, and to have it, you had to be born under a lucky star and, above all, escape the evil eye. Thus, every single evening, as soon as he reached the last houses of the large village of San Basilio, in a place called Bolo, before taking the rough mule track towards San Giorgio, he would dismount from the animal and stand on the opposite side of the houses. Then he would walk, almost rubbing the wall, trying to escape the gaze and the words of ‘Gnura Mena, the witch.

She was an uptight and grumpy woman who had lost her husband in the WWI and, since then, bitter for this harsh fate, she was said to cast the evil eye on other women’s husbands and children.

Everyone feared her.

That evening Zi Peppe Pileri thought he had dodged her, but he was wrong.

‘Gnura Mena was lurking at the edge of the trough, on the other side of the road, and he couldn’t avoid her.

“Peppe, is the day over?” the woman asked. “Yes, Mena, I’m retiring before it gets dark,” he cut in. “You know they still call a lot of boys to fighting in the war...” “I’ve already been to war with your dearly departed husband, Caliddo. They can’t call me anymore, Mena!” Zi Peppe said.

“Not you, but your son Ture can be!” “It will be God’s will, and God’s will will be done. Good night, Mena.” “God has forgotten us, Peppe,” was the harsh reply.

Zi Peppe digested the bitter words of the woman, but when the roofs of Bolo disappeared behind him, he stopped the mule and touched the iron under the hoof for good luck.

Damn witch, she is trying to jinx my son Ture!

When he arrived in San Giorgio, he put the beast back in the stable and went home for dinner. He wearily said hello to his family, ready for the evening meal, and sank into his chair, waiting for one of his daughters to come and serve him.

Concetta arrived. She was eighteen years old and already looked like a grown-up woman. She immediately became upset.

“You are stubborn, father! I told you that you should take off your boots full of mud outside the door!” Zi Peppe lowered his eyes. He was so absorbed in his thoughts that he had forgotten to take them off.

He apologized with a tired gesture of his fingers and brought a basin of hot water to clean at least his hands with a pumice stone because they were still dirty.

Concetta came back with a jug, filled the basin again, and with vigour, washed her father from the feet up to the knees, then dried him with a cotton cloth, put on his woollen socks, and began to prepare the table for dinner.

Before eating his soup, Zi Peppe grabbed the bread to cut it. He wanted to dunk a few pieces into the steaming broth, but while he was about to swallow the first bite, his wife, Za Nunzia, scolded him back:

“Peppe, you forgot to mark the bread with the cross before cutting it! What’s wrong with you? You’ve gone off the deep end! Don’t forget that the daily bread is God’s blessing!”

Zi Peppe sank the dripping spoon into his plate and looked up at Nunzia. “That old goat of Mena of Bolo cast the evil eye on me!”

“I can’t believe it... do you still believe in curses?”

“Shit, Nunzia, you still believe in priests, don’t you? And I believe in curses!”

“Don’t swear in front of the kids, and don’t insult the Church, as usual! And what curse did that poor woman cast to you? Let’s hear it…”

“She told me they’re calling soldiers to the war and that Ture might be…”

“That motherfu–” Nunzia winced, covering her mouth before uttering other insults.

“Tomorrow, if I see her at the trough, I’ll tell her off! She must leave my son Ture alone!”

Zi Peppe appeased her, and they both ate the last meal of the day in silence. It was a great relief that, at least for that evening, at the table, Ture was not there. He had gone to work for a week in Bronte.

After dinner, the whole family said a Hail Mary and prepared to rest.

Nunzia picked up a blanket hanging over the fire pit, laid it on their children’s bed to give them some warmth, and then returned to her husband. They chatted and promised each other not to pay too much attention to Mena’s words.

It was past midnight, but Zi Peppe could not sleep. He heard everything: the barking of Zi Dimonio’s dogs, the creaking gate of Zi Natale Sponzio’s henhouse, and, almost, even the river slowly flowing downstream. Above all, the words of Mena were still in his mind. Maybe the woman had never forgiven him for having survived her husband, who had also been on the Karst during the First World War. He turned towards Nunzia, seeking comfort from her body beside him. But in the pitch dark, even his wife’s eyes shone like stars.

That night, the Pileri could not sleep.

II

Zi Peppe Pileri often repeated that he had already lived two lives. About his first life, he told little and reluctantly. He referred to his harsh childhood, the troubles of his adolescence, and the subsequent tumultuous events that had involved him.

Of all of them, the memory that troubled him most was when, as a conscript, he was on patrol at the Camaro Infantry Regiment on 28 December 1908.

At dawn on that day, Messina was destroyed by an earthquake and seaquake. He survived by a miracle. The barracks had imploded in a few moments, and the ammunition storage area had blown up. As luck would have it, he was on patrol along the outer perimeter and was thrown twenty metres by the shock wave. He had been deaf in one ear for fifteen days but could not benefit from any recovery because he was needed to shovel through the rubble of the devastated city.

After that event, he spent a month and a half among the corpses, and the memory of those few survivors being pulled out alive from the ruins of the massacre still made him flinch. At the time, the Command had taken care to send a dispatch only to the families of the dead soldiers; there was no news of the living. Moreover, Zi Peppe hadn’t heard anything about his family, whether the earthquake had affected the villages in the Nebrodi mountains.

Only in March 1909, when he had finished his military service, he returned to San Giorgio.

He had not even had time to rejoice at the safe return of his loved ones when hunger and the crisis forced his father to embark him for America in May of that year.

After 29 days spent between Messina, Naples, and the Atlantic Ocean, he arrived in New York on 26 June 1909.

He was 20 years old and, arrived in the New Continent, had been admitted to the quarantine area of the Ellis Island Immigrant Reception Centre for a month because of suspected bronchopneumonia.

During those long days as a prisoner-sick man, he had met some shady Sicilian emigrants, who had hired him for some ‘special commissions’.

A few revolver shots he had dodged, a few others he had fired, and he had thus created a ‘respectable reputation’ for himself, thanks to his charisma and cleverness in smuggling whisky.

After six years, he was called up as a soldier in Italy because of the Great War. If he had stayed in America, he would have been considered a deserter and couldn’t have returned to Sicily any more.

Therefore, he had decided to return home, and, soon, young Peppe, from the charming and dangerous New York, found himself in the Cavalry Regiment Savoia on the Isonzo front.

He saw more dead people killed in one day on the Karst than in six years in New York!

When he returned, he carried the signs of war with him, and, suddenly, the American dream had vanished completely. The mere thought of returning to the Wild West that was America in the early 1900s made him shudder.

The Messina earthquake, the American mafia, the war, too much blood, and the too many deaths in so few years had worn him out.

He chose the quiet life of a farmer and decided to stay in San Giorgio.

There he began his second life.

A year after the end of the Great War, he met Nunzia and got married. Slowly, they began to cultivate the land, raise animals, and have children.

In November 1921, his first son, Ture, was born.

Ture was now 20 years old.

He was a bright and solid young man. As the eldest of the large family, he was, by right and by duty, the right-hand man of Zi Peppe Pileri, who had brought him up on hoe and bread from an early age.

Young Ture was meek, but not a few times he came home red with rage and fisticuffs. He never offended anyone, he was respectful towards his elders, and he didn’t let anyone push him around.

His brothers were still little and only helped out on some occasions, such as during the harvest, the grape harvest, or the olive and hazelnut picking.

Ture, on the other hand, was already of an age to serve the family full-time. When he didn’t go with his father, because there wasn’t much work, he was hired by someone and walked home in the evening because there was only one mule in the family, used by Zi Peppe. If he had any luck, on the way back, there was a cart that would take him to San Basilio, and from there, he would continue along the mule track that connected the two villages. Sometimes, however, he had no luck and arrived in San Giorgio wet to the bone because, on the way, he had been caught in a gale and, in order to not remain in the dark, had walked without shelter under the pouring rain.

Since the beginning of the war, things had got worse for the family because the local farmers no longer hired Ture on a day-to-day basis. They seemed resentful because he had managed to be exempted from the military service, thanks to a recommendation his father had provided him with.

It was as if those men were complaining that Zi Peppe had not also recommended their sons. Strong arms were needed. The war was causing hunger and mourning for almost a year over those desolate lands of the Nebrodi mountains.

Zi Peppe knew well that some things were better done by himself and for himself, so he had pulled some strings only for his son Ture. Besides, he knew from experience that, if the situation were reversed, they would have provided only for their children so as not to lower the chance of saving them from the war.

He had succeeded, and he did not even feel guilty about it. He saw Ture working hard for his brothers and sisters and knew he had done the right thing.

Honest as he was, however, he did carry a little guilt inside: he had had to bow down to lord Marchiolo, a hardened fascist, who had rank and power at the Military District of Tortorici.

He had swallowed many bitter pills just for his son, to keep him with him in the fields and, above all, to save him from the horrors he had experienced on the Karst, and from almost certain death.

For this reason, when ‘Gnura Mena had cast the evil eye on him, he had felt it all over him! It was not just the words of a charlatan, but a common feeling that had crept into the souls and minds of the other villagers: why were their sons at war, while Ture, young and strong, was still serving his father?

The war had taken many strong arms from their families, and this was the major gripe.

People were starving, and hunger claimed more victims than war. And it took no prisoners.

III

At first, Ture wanted nothing to do with going to war, hearing his father’s gruesome tales. As soon as he was exempted from military duties, he went back to his village, and the next day he set off to work in the fields.

Summer arrived.

With time, however, this privilege began to take its toll on him, as he felt the eyes of everyone, especially the families who had soldiers at the front.

His behaviour began to be affected: he withdrew into himself. He became more and more quarrelsome and grumpy. Sometimes, when people asked him why he wasn’t at war, he would tell them stories he made up at the moment. He said he was waiting for being called to the front to some of them. Or that he was about to leave the following month. To others, that he was about to embark from Messina or that any more soldiers were needed. Time passed, and, at the end of July 1941, Ture was still in the fields harvesting with his father.

After a time, most people began to disbelieve these excuses, and many others, who learned the truth, accused him of being a coward, of bringing dishonour to their village. And even if they did not spit such contempt in his face for fear of getting a few punches in the jaw, they talked behind his back everywhere: at the mill, the haberdashery, the grain stores.

Ture would hear this chatter, and it would eat away at his pride, but when he got home in the evening, he would look his brothers and sisters in the eye, and the thought of these evil tongues soon disappeared. For this reason, he worked even harder. He felt that he owed to fate, then he busied himself with many more tasks than his father gave him daily.

August also arrived.

One evening, when he came back from the countryside a little earlier, he saw Concetta loaded down with some pitcher, intent on going to the trough near the river, and offered to help her.

“Why are you in a rush to help me?” His sister asked.

“Usually you nod your head and say thank you in these cases,” Ture replied.

“Are you coming to help your poor sister or to see your cousin Lia?”

Concetta’s question caught her brother off guard. Cousin Lia was nineteen years old. She was already shapely but not yet engaged. Ture had honestly never thought she could be anything more than a cousin.

“I’m not interested in Lia, and if you talk any more, you will go to the trough on your own!”

“No? Too bad...”

“Too bad, why?”

“Because Lia likes you!”

“Concetta, stop it! I don’t have time to be engaged now and don’t put ideas in our cousin’s head. Indeed tell her that your brother Ture doesn’t want her, so she’ll make her peace!”

“Then you can tell it to her if we find her at the trough.”

“I don’t have to tell her anything! That’s a lie you put in your head. Or maybe mum and dad want me to settle down with Lia? Tell me the truth!”

Ture, worried that his parents wanted to arrange a marriage with his cousin, stopped suddenly, put down the pottery pitchers, and waited anxiously for his sister’s reply. He had a debt of honour and gratitude to his father for the military service issue, but he did not want to settle it that way.

“Brother, calm down! Nobody knows anything. Lia confided in me, and that’s why I told you. If it’s not your will, then nothing will be done about it,” his sister said, resuming her walk.

Ture took up the pitchers again and started walking towards the trough. His sister’s reply had relieved him, and, with a slight grin, he continued the conversation: “And you, how is it that at eighteen you are already a matchmaker? If you want, I can find a suitor for you, sister dear!”

“Stop it, you moron, I can look after myself all right, and when I get engaged, no one will know! One evening I would take him home suddenly, and the next morning I get married!”

They burst into roaring laughter, and as they were close to the trough, they attracted the women’s attention, who were also intent on collecting water in their pitchers.

There was Lia, who seemed to have been waiting for that moment all her life. Concetta’s face was enough to dispel any illusion.

They spent some time apart, and Ture’s sister confessed that her cousin was not interested in her.

Then Lia, feeling rejected, was filled with rage faster than the pitchers being filled. Then she began to taunt Ture, always on the story of the war, of the exemption, of Zi Peppe Pileri’s recommendation.

Ture didn’t answer. He knew very well that these provocations came from a young woman whose pride was wounded, and he waited patiently for that trickle of water, now made feeble by the August heat, to fill the pitcher without uttering a word.

Suddenly, a young, witty voice broke the irritating blabber of Lia.

“Shut up, lizard!” On the other side of the big trough, Lia’s younger sister, Rosa, blurted out to the older one with such a scowl that Ture himself, who had not noticed her at first, was intrigued.

Lia suddenly became quiet. Although she was the eldest, she felt like those vain horses that suddenly, for nothing, become agitated and to which the master, to calm them, gives them a single well-aimed blow of the whip. She pulled a sheet out of the big straw basket and resumed her washing without looking at the onlookers.

Ture, on the other hand, had not ceased to stare at Rosa during all those brief moments of silence following her heated intervention, and when their eyes finally met, the young woman almost blushed with shame, and he nodded his head briefly in thanks.

Concetta exchanged a few more unclear words with poor Lia, who was venting her lingering anger on the sheet, now whiter than snow. Then she waved for her brother to start off for home, for the evening was already approaching.

“Lizard!” Concetta said when the trough was far away. “From where did Rosa pull that?”

“It was a polite way of not saying snake to her,” her brother retorted. “But is it acceptable that she addresses me like that – just for a no as an answer –, to talk bullshit she’d heard around? Forked lizard!”

“And what kind of animal is Rosa? Let's hear it…”

In a different mood and tone, Ture said: “Rosa is a little dove!”

“Hahaha! A little dove sharp-tongued, though!” Concetta retorted, with a smile on her lips. “And if I didn't shake you, you’d still be there, at her until dark! You see, Rosa isn’t one of those little doves you can get your hand on!”

Ture had the peculiar ability to imitate the dove sounds so well that those birds approached him without fear. Now and then, in quiet moments in the country, he would sit among the branches and attract the lovebirds with his cry.

“You always know everything, Concettina, don’t you? You feel like the sage of the house, the schoolteacher!”

“I don’t know anything, but I saw you staring at the little dove!”

“Only because I hadn’t seen her for a long time. She’s grown, that’s all…”

“The little dove is not easy to catch, dear brother! She doesn’t fall under your lures.”

“Why not? What do you know about it?”

“Ture, are you nuts? Because she is a rogue little dove, and if you try to catch her…”

“She flies...” his brother continued. “I know very well that, if you get too close, she gets scared, opens her wings... and flies.”

IV

Ture carried the story of the little dove with him for days to come. He kept thinking about Rosa, how she had reprimanded her sister, and how she had shyly lowered her gaze in front of her cousin’s awe-struck eyes. This last image was upsetting his soul.

At the sweet thought of his cousin, suddenly, everything else paled in comparison: the anxiety about the war, the rumours in the village, the uncertainty about his future. How many times had he seen her? At least ten thousand, if he had bothered to count. But a few nights ago, at the river fountain, for the first time, he had looked at her with different eyes.

Without realising it, Ture Pileri was falling in love.

Throughout August, he had only seen Rosa a few more times and only briefly. However, since that day at the trough, he lost focus. His hands were always sweaty, and his hoe would almost slip from his grasp. If he was tending the herds, and some goats would escape down the slope, he did not even notice them, so much engrossed in thoughts of that young girl who had stunned his soul.

All this without Rosa ever saying a word to him.

For another two months, no one was seen there, in San Giorgio. The war seemed to have forgotten him, but Ture, on those autumn nights of 1941, thought only of Rosa’s voice, because in his head reverberated that shut up, lizard shot in her sister’s face; he dreamed of sweet words in a time without hunger or need. Then, at dawn, he would wake up again in his world: the air was already beginning to get cold and sharp, half a bowl of milk and a piece of hard bread to dip in, and then work, the fields, the goats in the afternoon and nothing more.

In the moments of solitude, Ture’s twenty years of age all appeared before him.

What had he been up to all that time? He had served his family, had listened to his father’s advice, had gone, and still went to work under a master. He thought that, deep down, he had never done a thing on his own, never stepped out of line, never said a word more, and even the times he had gotten into fisticuffs, it had only been to defend himself.

It was All Souls’ Day, when Ture, looking after the goats in Santa Nicola, met his uncle, Zi Nunzio, Lia and Rosa’s father, whom everyone in San Basilio called Zi Duca.

A pleasant sun kissed the spring-like morning and warmed bones numb from the dreary season.

“God bless you, Zi Duca. What are you doing here?”

“We are picking some asparagus. Your cousin Rosa is close by.”

“And Lia isn’t here?” Ture asked.

“No, she’s been in a foul mood lately and stayed at home. If you go down the road, and you’ll find her under the brick wall.”

He didn’t even have time to make sense of Zi Duca’s answer when Rosa jumped out of a patch of broom.

In one hand, she was holding her apron full of wild asparagus, and in the other, an awl with which she was digging the earth. Her raven hair was in a braid, she wore a heavy pair of boots that were too big for her slender feet, and she had the dishevelled look of someone clinging to cliffs to tear up the precious vegetable with her bare hands.

She is beautiful!, Ture thought. Even more beautiful than that evening at the fountain.

Looking at her with different eyes now, he understood he had always loved her and was blind before. He figured out a way to get close to her and to talk to her without anxiety. He wanted to express this feeling without a shaking voice and sweating hands.

Ture Pileri had never been in love, and now, like a bolt of lightning, Rosa had arrived to change his thoughts and disrupt his days.

In the meantime, Zi Duca had picked up some shredded tobacco from his pocket and, while he chewed it, had settled down to rest.

Ture took the opportunity to trot over to Rosa, hoping to get a few moments alone with her. When he reached her, Rosa herself made the first move.

“Cousin, how are you? Have you forgiven my sister Lia? Sometimes she gets caught up in the heat of the moment!” “It’s been a lifetime since that evening, and I’ve already forgotten about it,” Ture replied. Then he let the most longspun moment of his life pass, drew a long breath, and declared: “I can’t forget you, Rosa!”

The young girl gasped, so much so that she knocked over most of the vegetables she had collected. She quickly picked it up again and slipped off in the direction of her father, dismissing Ture, who had remained motionless.

In the meantime, Zi Duca had fallen asleep in the shade of a mulberry tree. His daughter woke him up, shaking him so abruptly that he was startled.

“Father, stand up! Come on, don’t sleep!” “Damn hell! I had just fallen asleep!”

Zi Duca huffed repeatedly, rinsed his face with some water he had in his saddlebag, then, with the help of his nephew, he rose and was ready to set off again with his daughter.

“Females are a blessing and a curse, dear Ture!”

Rosa glared at him, then began to clean him up. “Father, I’d better wash these clothes tonight! That tobacco in your pocket has stained everything! I’ll go alone. I’m sure Lia doesn’t want to come.”

They said goodbye to Ture and started walking home. After a few steps, Rosa turned to her cousin and waved stealthily. She was doubtful that he had understood.

Ture was still surprised: did Rosa want to meet him at the fountain that evening, alone? He turned those words over and over in his head, yet he could not make any different sense of them.

Why not invite him earlier, when he had confessed to thinking of her all the time? Why run away like that and then throw that mysterious invitation at him instead?

He didn’t understand, but he wanted to believe that this was a clear signal that she wanted to meet him. Besides, what could poor Ture do? He had never had a woman, and so they were a completely unknown universe to him.

He could only wait for her to the fountain and hope to talk to her openly this time.

Ture arrived at the fountain early. He hid in the shade of a vine and watched the women passing by. When he saw Rosa emerge from the path, he was startled. He waited a moment, saw that she was alone, and realised that he had been right. From that moment on, every word could change his life, and his palms began to sweat again. To kick this off, he decided to take the situation head on and approached his cousin. He didn't even have time to say a word that the young woman shoved a pitcher into his hands.

Ture understood the meaning of this sudden gesture: in his frenzy to meet Rosa, he had not even thought of creating an alibi for himself in the eyes of the people who came to the fountain. Instead, that pitcher protected them. Although they were first cousins, as the children of two sisters, the situation could arouse suspicion.

It was Rosa who broke those initial moments of silence.

“I’ve been thinking about you since last year’s harvest, Ture Pileri! It’s been thirteen months!”

Ture’s eyes widened in astonishment, he went back in his mind to that harvest, but nothing came up, no particular memory of those days, nothing that would remind him of that little girl who was about to become a woman.

Ture was bewildered by this revelation, and he didn’t even realise to take the filling amphora out from under the spring. He did not realise that time had passed so suddenly that the water, gushing out, soaked his shirt up to his sleeves.

“And why did you wait all these months to tell me that, Rosa?” “To be honest, if you had chosen my sister, I would never have told you. I would have suffered, but I would have got over it. Lia likes you, but then that evening, right here, she understood that she was unrequited and, reluctantly, she is putting her soul at rest. At first, I didn’t want to tell you anything anyway. I didnt want to hurt my sister, but when you told me that today…”

“What I told you today at San Nicola is the truth! I want to be honest with you, and I’ve been honest with your sister. I’m not interested in her and, until that evening at the trough, I wasn’t interested in you either. Then, I don’t know, since your words that time you are in my head. I’m not good with words, you know, but that’s how I feel, and you can’t imagine how much I prayed that I wasn’t wrong today when you said that thing about the dirty shirt to your father and the trough.

Rosa, who had been rinsing and rinsing the clothes all the time, stopped for a moment, looked around, and, realising that they were alone, hugged Ture, who seemed taken aback by this gesture. She kissed him on the cheek.

An almost embarrassing smile formed on his lips, but he didn’t even have time to wrap his arms around her when she was already back on the washing line.

Ture thought back to the story of the little dove and his sister’s words – A little dove, if you try to catch it, flies away!

“My father loves you,” Rosa resumed. “You know, he has never believed what they say... I mean, in the story that you dodged from the war. He says that Zi Peppe Pileri did well and that he would have done the same thing for his son!

Ture did not want to change the subject and, focusing back up, asked: “Are you going to tell Lia?”

“I do not feel like it yet. Moreover, it’s too soon.”

“Are we engaged then?” Ture asked, lowering his gaze.

Rosa smiled. She was only sixteen, but she seemed much wiser than her cousin in matters of the heart. So she answered him with gentle eyes: “How naive you are, Ture Pileri! Tell me, are you always good at imitating the call of the doves?”

Her cousin smiled. Rosa’s last question had relieved him of his embarrassment. He put his hands over his mouth and began to imitate the cry of the birds.

It was time to go home, so Rosa put the wet clothes in the basket while Ture emptied and filled the pitcher for the last time and offered to accompany her to the first houses of San Basilio.

There they said goodbye, and after he had kissed her on the cheek, his hand lingered on her face. He followed Rosa with his eyes until he saw her disappear down the street, then walked home.

He returned to San Giorgio very excited, tempted whether or not to tell Concetta. He took off his boots and went inside. As soon as he closed the door behind him, however, he felt a strange tension. Everything was eerily quiet.

Concetta hugged him, almost knocking the breath out of him.

“What’s happened?” Ture asked, puzzled.

“My son,” his mother answered, “they say a postcard has arrived for you in the village.”

“Postcard? What postcard?”

His mother, drawing all the strength she could from her heart, said: “The war, Ture. They called you to go to war!”

V

Ture skipped dinner, dismissed his family with a brief wave of his hand, and had Concetta bring him a basin of cool water to wash his face.

He was about to stand again when he saw that, in the meantime, he had been surrounded by Santo, Betta, Nino, and Calogero, his younger siblings, who tried to comfort him with their candid innocence.

Ture dried his face, moved the basin of water aside, and held Calogero, who was not yet three years old, in his arms. He kissed him on the neck as he always did and then knelt and hugged the other three, trying to hide the tears that welled up in his heart.

Concetta and Sina, his other two sisters who were already girls, made up the bed for him, so their brother, leaving the little ones, spread his arms and held them close to him. Then he got ready for bed.

Hardly a half-hour passed before his mother joined him. Ture couldn’t sleep while his other brothers in the room had already fallen asleep, so the woman, under the light of a small candle, quietly approached her son’s bed and, in a quiet voice, tried to reassure him.

“Your father says he will find a solution,” Nunzia said.

“My dear mother, I want to be honest, when I did the medical examination in Tortorici, I felt in my soul that my time had not come. I don’t know why I had this feeling. It wasn’t only the fact that my father had found me the recommendation to be exempted. I was calm. I thought, If war is in my destiny when it comes, it comes. Then my time had not come, but now, I know that I must leave. I felt it somehow, but not right now, when…” Ture cleared his throat. As vulnerable as he was at that moment, he didn’t want to reveal to his mother what had happened only a few hours before with Rosa. Rosa! Those moments of happiness seemed so far away! Within that one day, things that would happen in a lifetime had happened.

How could he tell her now? He was already struggling with words. How to look her in the face and say, “My beloved, I must go to war”?

He thought about all these things, losing himself in his mother’s sad eyes. Then he caressed her gently.

“It will be as God wishes, mother. Please, don’t worry!”

A tear ran down the woman’s cheeks. She kissed her son on the forehead and let him rest for the night.

When the dim light of the candle left the room with his mother, Ture felt the weight of the world on him.

So much for ‘Gnura Mena!

All the jinx of the world had hit him now that his heart had finally known love. Now that he had a reason to get out of bed every morning. Now that the future was beginning to look less bleak.

The war, like a blow between his head and neck, threw him back into distress, numb. He would lose so much love! His little brothers, his parents, and Rosa.

Would she, in the bloom of her youth, so beautiful and graceful, have waited for him? And for how long? In the end, it had only been a kiss on the cheek. Two words exchanged on an afternoon at the trough. It might have been just a fleeting moment and nothing more. How real could the love of a sixteen-year-old girl be? Although she told him she had had him in her heart for more than a year. But would she be willing to wait for him for who knows how much longer, staying away from so many other young men who would court her?

These doubts gripped him. He felt that the fear of losing Rosa was heavier than his own life.

He sensed his brothers’ quiet sleep floating in the dark, envied their age and blissful innocence.

He loved them so much that the thought that he would also go to war to ensure their peaceful future comforted him.

That night, Ture Pileri felt “atonement”: the recommendation, the nasty rumours of the other villagers, the jinx, the rejection given to Lia. Everything would be alright if he went off to war. The evil tongues would have been hushed up, the jinx would have been fulfilled, and even Lia would have breathed a sigh of relief for not having compromised herself with a soldier whose fate was completely uncertain.

But that didn’t seem to work out well because a family would lose, perhaps forever, the love and the arms of a son. Then a young lover would be left, frozen like a rosebud after a night frost.

There was no consolation in Ture’s soul, only the extreme desire to carry all these burdens upon himself, undeterred, and then, as he had told his mother, he mumbled, “As God wishes”.

Just before dawn, Zi Peppe got up and rode his mule to the village. He wanted to make a last, desperate attempt to save his son from the war. The first rays of sunlight touched him, already on the road to Salicaria.

He had planned to reach his destination early in the morning and meet the head of the district council, Marchiolo, careful not to cross path with the municipal messenger. He was afraid that he would give him the infamous postcard. He arrived in Galati in the early morning hours and, cautiously, looked for the officer at the Circolo dei Nobili.

As soon as he saw him, Marchiolo immediately understood the reason for his visit. He had already received many other help requests in the last few days because of those cursed postcards that called even those who could not be called up to arms. He signalled with his head to Zi Peppe to retire to the back and joined him.

“Zi Peppe, did the postcard reach Ture too?”

Lord Marchiolo, we haven’t received anything yet, but I’ve heard that he’s on the list to be summoned. They say three people from the village have to leave, and they were considered unfit at the examination.

Lord Marchiolo, though sympathetic to the rightful prayers of an affectionate father, shook his head as if apologetic.

“Zi Peppe, there’s little you can do for your son, as for the others: the war isn’t turning in favour of the Duce, and all able-bodied young men are needed at the front. Those who desert risk being shot. I can’t do anything this time! A physical exam is one thing, a call to arms is another. In January, at the Military District, I had contacts with the medical lieutenant and could pull some strings: it was a matter of a professional opinion, so we could at least get a chance. And that’s what happened: we made it. Now, however, they call directly from the lists and without medical approval. He who has two arms and two legs go. Is your son an amputee? No! So he’ll have to enlist.”

Zi Peppe took off his cap and wiped his sweat. In front of the honest words of the Sir, he felt powerless, and, with a voice broken by resignation, he tried to advance some faint hope.

“I’ve come to terms with the fact that my son has to leave, but can’t we even stretch things out a little?”

He did not want to give in to the idea of losing Ture and tried to find at least a temporary expedient to postpone his departure. Lord Marchiolo pondered for a while, then, as if enlightened, looked up at Zi Peppe.

“You said, if I’m not mistaken, that he still hasn’t received the postcard? You know it’s supposed to arrive only by hearsay, but you haven’t signed anything. Did I get that right?”

“Yes, Sir!”

“Then, Zi Peppe, there’s one thing we can do, and that’s final! Of course, as I’ve already told you, sooner or later, he has to leave, but at least for a month, a month and a half, we can stretch things out, as you said.”

Zi Peppe leaned with his whole body and soul towards his interlocutor. He had understood that perhaps a solution, albeit temporary, even this time, was found.

“You have to send him away from the house!” Marchiolo said. “Make sure that when the messenger comes to serve him the postcard, he’s not there, and he mustn’t be in the days to come either. Don’t do anything stupid, I’m telling you! Don’t hide him in the stable and send him to the country the next day, because if they catch him, the Carabinieri will shoot him and you too!”

“And where shall I send him?”

“Send him to some farm in Nicosia, Enna, Paternò! Anywhere far from the province of Messina. Sooner or later, the notification will reach him there too but, from town to town, the paperwork is slower. If, perhaps, in the new year, the war ends, by the time he leaves, they train him and assign him... he might end up not even serving a day in the front line.”

“And if the messenger comes with the postcard in his hand, what shall I tell him?”

“You have to give him an address! It’s enough to say, my son is in Carrapipi, at Mr. Tizio’s farm, without any other specifications. In this case, he will not be considered a draft evader or deserter, but the call will be left open and marked as in notification. In the end, Zi Peppe, I’m telling you not to get your hopes up: they will find him! But at least a month, and maybe a few more, will pass.”

“I understand. Thank you, eminent.”

He kissed his hand, then took a wrapped piece of cheese out of his saddlebag and handed it to him, despite the sir’s reluctance, who initially did not want to accept the gift.

Zi Peppe Pileri watered the mule at the trough in the square and sat down in the shade of the large poplar tree. He still had the other half of the cheese and had also brought with him a piece of bread and some olives. He ate only the bread and two olives and quickly finished his frugal meal.

As he was about to head towards the animal, a voice called out to him.

“Peppe Pileri, a glass of wine would be good for us now, wouldn’t it?”

Zi Peppe, blinded by the midday sun, found it hard to see who was calling him, although he guessed that the words were coming from Don

Giardinieri’s small shop. He walked towards the shop, and, as soon as the wall blocked the sun, he was surprised to discover that it was Zi Calogero Tocco calling him, who had been with him in the Karst and had returned together at the end of the war. They embraced each other warmly. They had not seen each other for months.

“Are you still alive, Calogero Tocco?”

“My friend, if the good Lord didn’t take us to the Karst, I don’t think He wants us anymore!”

“It was fate that today was a day of war then!”

“We’ve been at war for over a year. Why are you talking about today?”

“They called my son Ture: he has to leave too, and I came to Galati today to get help.”

“And did you manage to get anything?” Calogero asked.

“A month, maybe two, but then…”

Zi Peppe, disheartened, shook his head and shrugged. The other man, understanding his friend’s worries and knowing how hard and horrible the war was, put his hand on his shoulder and signalled to the boy to pour another glass of wine. He gave it to him, they both drank in silence, and, after thanking Calogero, Zi Peppe returned to the mule looking a little refreshed. The wine, at that time of day, had made him a little happy, and when he got on the beast, the animal seemed reluctant to move and spurred it on with a mighty slap on the back.

“What’s the matter? Were you disappointed because I didn’t give you wine? The water from the trough and the shade from the poplar tree was enough for you! I respect you! If you belonged to someone else, he might have left you in the sun all morning!”

The mule snorted, but then, as if encouraged by his master's words, he resumed his journey at full speed.

He had not yet reached the Mother Church when he heard himself being called again.

“Mr. Di Nardo, Mr. Di Nardo!”

A shiver ran down his spine: no one called him by his surname. Everyone in the village knew each other and called each other by their informal names, and, for a moment, he was afraid it might be the Marshal of the Carabinieri.

When he turned around, he saw a man in civilian clothes, elegant and with greasy hair. He was not a familiar face and addressed him with his usual reverence: “God bless you, to whom do I have the honour of speaking?”

The man nodded his head in cordial greeting, waited for Zi Peppe to get off the mule, approached him, and offered him his hand. “How do you do. I’m La Pinta, the town messenger.”

VI

Zi Peppe Pileri was face to face with the one person he had been trying to avoid all morning. In those interminable moments, he cursed those two glasses of wine drunk at the little shop. He thought that if he had left without delay, he might have avoided that unwelcome encounter. But it was too late. The town messenger was standing there, in front of him and his mule, and he had to address him.

“At your service,” Zi Peppe replied.

And the messenger, without much pretence, got straight to the point.

“I have a draft notice for your son Salvatore. He lives in the village of San Giorgio. Can you confirm that?”

Zi Peppe, with all his confidence and pride, answered the messenger.

“I confirm! My son is in San Giorgio. He is now with the animals, but you will find him at home tonight. He is twenty years old and is my eldest son. I have three more boys beside him. They are eleven, eight, and three years old; I also have three girls. The oldest is eighteen, the second is fifteen, and the third is eight. Only the first two, Concetta and Sina, can help the family. The other four, as you can understand, are still children. So, dear sir, I talk with a heavy heart when I say that if you take Ture away from me now, it’s like cutting off my arm. No one questions that he must go, nor do I want to make him desert. He’ll go, and he’ll be a soldier, and I only ask one thing: leave him with me for a fortnight, just two more weeks! Today is Friday, right? Well, in two more Fridays I’ll come here again to collect the postcard, and I won’t even bother you to go as far as San Giorgio.

In the meantime, I’ll send him to a friend in Troina. The postcard will then go to Enna, and from there, one of your colleagues will notify him, and then he will have to leave. As you can see, I am well informed, and I do not want to tell you any lies or small talk. I wish I could spare my son a few months of war! I was in Karst in 1917. We were dying like flies. One day we were laughing and joking with a comrade and the next day half of us were dead! Don't give his mother this pain! Give her a few more days to get used to the idea of losing him, perhaps forever.”

The messenger stroked his hairless chin with his hand and then, with a condescending tone, replied: “Mr. Di Nardo, if I did that with all the young men, who would go to war? I’m only doing my duty, and I have to account for these postcards…”

“Are you a father, sir?”

“Yes, I have two children.”

“I have six little mouths to feed and a son who has to go to war... Please have a hand on your heart!”

The official reflected, looking around briefly, then turned to Zi Peppe with a resolute face.

“One week, that’s all I can do. I’ll come to San Giorgio, and you’ll have to tell me where you’ve sent him: town, address, name, and surname of the person who hired him. This is not a negotiable offer. Believe me, for your sake, I am going beyond my official duties. Needless to say, no one must know of our agreement. Otherwise, you will find me at your doorstep in San Giorgio, but this time with the Carabinieri! Go on... You and I have never met!”

Zi Peppe nodded gratefully and put the other half of the cheese into the messenger’s hands. In a flash, he jumped on the mule and urged it to set off. He realised that he could not have received a better offer than that and felt satisfied.

The messenger stowed what he had received inside the bag with the postcards, looked around to make sure, for the umpteenth time, that he had not been seen, and resumed his chores.

Arriving in San Giorgio at dusk, Zi Peppe took Nunzia and Ture aside and told them what had happened in the village. The woman sighed and curled up in her chair, distraught. He was her son and, although she was aware that her husband had done everything he could again, she couldn’t get used to the idea of losing her boy.

Ture, on the other hand, was thinking only of Rosa. He pondered the words his father said and searched inside himself for a way to tell this to his beloved. He had a week left, and then he would shelter in Troina until they would track him down and notify him of the date, by which he had to appear at the Military District in Messina. Finally, the front.

Firstly, he decided to reveal everything to Concetta. He had wanted to do so the night before, but the news of the incoming postcard had upset everyone, and he had had no way or time to talk to his sister.

That same evening, he made up his mind and told Concetta what had happened with Rosa, from the episode of the lizard to the afternoon spent at the trough. The girl smiled and, as usual, she surprised her elder brother again.

“I had imagined it. You should know that your sister has eyes and ears everywhere. I’m not surprised at all!”

“But how? I told Rosa not to say anything. We had agreed that…”

“Rosa didn’t tell me. It was too simple. I understood it by myself. I heard that you were at the fountain yesterday afternoon and it seemed strange to me. I thought: he never goes to the fountain and now he goes twice in such a short time! And then, I saw that the pitchers were halfway up, and I imagined that if you had gone there, it was not for the water but some other reason. Then I also heard that you were with Rosa, that you accompanied her home, and I connected these facts with the reaction our cousin had that time she called Lia a lizard. It was pure jealousy! The only thing I wasn’t sure about was whether you had already been seeing each other since before that night or if it was something born later, but now you have cleared everything up for me. Well done, brother Ture, you’ve caught the little dove at last!”

Ture was astonished; he thought he had done everything with the utmost reserve that time at the trough, but his sister had understood everything anyway. He felt like a fool, but it mattered little, and asked Concetta for advice on how he could tell Rosa about his imminent departure.

His sister eventually ruminated on Rosa’s words.

“If, as she told you, she has waited more than a year, will be able to do it again; indeed, now that you have declared your love, she has an even better reason. Now you are together, and she has the certainty that you want each other. Write to her, don’t forget and do as I say: send the letters for our mother here in San Giorgio, those for Rosa to me and have them delivered to Zi Strino’s shop in San Basilio; no one will suspect a brother at war who writes to his sister.”

Ture smiled and felt relieved, and the two hugged each other affectionately. He thought of what a good wife and excellent mother his sister would be one day. So clever and wise already at eighteen, who knows at twenty or twenty-five.

The next day Ture waited again for Rosa at the trough

As soon as she arrived, together with his sister, Ture called her aside, not caring about Lia’s reaction, who ignored him completely.

He reported the events of the previous day and those that would happen from then on.

“I have to go, Rosa. There are no saints to help me this time. It’s war!”

Rosa listened attentively to every word Ture said and sometimes shook her head in disbelief.

She had waited, had cherished that love that seemed impossible, defying her old sister’s anger. And now that she was ready to take flight, she couldn't fly like a little dove. The war clipped the wings of the ambitions and dreams of many young people.

She knew that but never before had she imagined that such a fate could befall her. And then, finally, the war which, at that moment, was also taking away her hope and knowledge of love itself.

She had been thinking over and over how to break the news to Lia and her mother, what words to use and how to fight to defend her feelings for Ture. In San Basilio, as in San Giorgio or the village, marriages were often made out of self-interest because people died of hunger but not love! Therefore, the will of the family was significant and, many times, crucial.

But Rosa would not have accepted impositions, and she had even considered facing the shame of an elope to get Ture. She would have run away with her beloved for a few days, she would have compromised herself with him, and then things would have worked out somehow.

She had heard of other girls who, to escape the impositions of the family or simply to accept an undesirable debt, finally decided to run away with their beloved at night. Yes! She would undoubtedly have done so because now she was sure that Ture Pileri loved her too. Although her heart was in pieces because of what was happening, she felt incredibly strong, and not even the war scared her.

She would wait for him for another year or more. What a pity, though! Just now that they had got engaged, the front was calling.

Would she see him again before he left? Or was this already their last time? No one could know.

Ture pulled Rosa behind a mulberry tree. Their lips touched in a long, deep kiss because they both wanted that kiss to remain in their hearts, like a trace, an indelible sign of their love.

Throughout the week, Ture and Rosa continued to see each other in secret. During those days, they tried to insert support strips next to the small and vulnerable creature that was their affection, similar to how they used to do in the countryside, to prop up the vine or the young and fragile tomato or bean plants.

It was as if they were looking deeply into each other: how much could they rely on each other?

Ture had before him a young girl who was only sixteen but who had been the driving force behind the whole thing: she had fallen in love with him, had waited for him, and had even put herself aside out of respect for her older sister who, in the family’s original plans, was to be destined for Ture. Then, when the tables had turned, she had taken action, seizing the right opportunity. In a flash, she had taken it. In Ture's mind, these were certainties.

But how long would the war last? How many things could happen? And then, the biggest hurdle was their families. A marriage between cousins was not difficult to digest, but his rejection of Lia could be an impossible obstacle. Yet Rosa seemed so determined! She looked like a lioness, and nothing frightened her. In front of the girl's certainties, Ture was afraid of appearing too soft, too indecisive. He didn’t want to appear doubtful because, quite frankly, he wasn’t.

He was only a few years older than her, therefore, he was trying to remain a little more grounded. The war had destroyed nations, homes, lives, and even loves, unfortunately. He knew that well.

“What if I never come back?” He repeated.

“If you don’t come back, it won’t be your problem anymore,” Rosa answered, almost sarcastically. But this answer certainly did not reassure Ture.

In those last days in San Giorgio, he had grown more afraid of leaving Rosa alone to face the pain of his death than of dying in the war. He had said this to her and got the sweetest answer in the world.

“It means you really love me! So I’m not wrong in loving you too!”

And it was true. Digging into his soul, Ture Pileri felt he loved Rosa more than his own life, and yet, from that moment on, ironically, he had to learn to love his life more.

If he wanted to reclaim Rosa on his return, he could only do so with his life on him. So he agreed that, when the impetus to live on the front line was gone, the thought of Rosa waiting for him would give him strength. She was the path and the light that would never let him lose hope.

However, the second to last evening, Zi Peppe surprised his son, telling him they were leaving for Troina at dawn.

Some farmers, who were also travelling to the inland parts of Sicily, had suggested they joined them in making the journey. First skirting the heights of Serra Corona and then cutting across the mule track that, passing through the Mangalaviti woods, wedged between Serra del Re and Pizzo Cannella. From there, they would easily reach Cesarò and then the road to Troina. So they would have left a day early, but at least they wouldn't have had to walk alone along that rough and difficult path.

Ture understood his father’s good intentions but, by doing so, he would never see Rosa again, who was obviously unaware of his early departure. He, therefore, sent an embassy to Concetta to tell Rosa of his sudden departure. His sister reassured him, but Ture’s soul was sad to the core.

The farewell was imminent.

VII

At dawn, as planned, the farmers, who had agreed to make the journey together with Peppe and Ture Pileri, reached the houses of San Giorgio, and from there, the caravan set off towards the province of Enna, crossing the Nebrodi along paths and mule tracks.

After leaving part of the travellers in Cesarò, father and son reached the farmhouse of Lord Solima in Troina before nightfall. Mindful of his friendship with Zi Peppe, Lord Solima welcomed Ture with open arms, knowing that the young man would leave without delay as soon as the municipal messenger arrived for the new notification.

So, a few days later, when the messenger La Pinta arrived in San Giorgio, Zi Peppe, honouring his word, told him the address of Lord Solima’s house in Troina.

It was over: they would have found him, but he would have spared his son Ture at least a month of war, or maybe more. When the town clerk left, Zi Peppe shook his head, dejected: he had done all he could. Then he stretched himself tightly on his chair and kept to himself without speaking.

Za Nunzia approached him, gave him some water, and put her hand on his shoulder: it was a way to sympathize with her husband. She wanted to make him feel all the love she still had for him, for that man who had always devoted himself body and soul to his large family.

“And now what? What will happen to my brother?” Concetta asked.