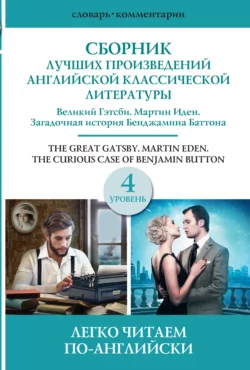

Сборник лучших произведений американской классической литературы. Уровень 4

Сборник лучших произведений американской классической литературы. Уровень 4

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald

Jack London

Легко читаем по-английски

Данная книга представляет собой сборник самых знаменитых произведений американской классической литературы. В него вошли такие романы, как «Великий Гэтсби», «Загадочная история Бенджамина Баттона», а также «Мартин Иден», на которых выросло не одно поколение читателей по всему миру.

Тексты адаптированы для продолжающих изучение английского языка (Уровень 4) и сопровождаются комментариями и словарем.

В формате PDF A4 сохранен издательский макет книги.

Джек Лондон, Фрэнсис Скотт Фицджеральд

Сборник лучших произведений американской классической литературы. Уровень 4

© Матвеев С.А.

© Прокофьева О.Н.

© ООО «Издательство, АСТ», 2021

F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Great Gatsby

Chapter 1

In my younger years my father gave me some advice. “Whenever you feel like criticizing any one[1 - Whenever you feel like criticizing any one – Если тебе вдруг захочется осудить кого-то],” he told me, “just remember that all the people in this world haven't had the advantages that you've had.”

A habit to reserve all judgments has opened up many curious natures to me. In college I was privy to the secret griefs[2 - secret griefs – горести] of wild, unknown men.

When I came back from the East last autumn I felt that I wanted the world to be in uniform. I wanted no more riotous excursions with privileged glimpses into the human heart[3 - riotous excursions with privileged glimpses into the human heart – увлекательные вылазки с привилегией заглядывать в человеческие души]. Only Gatsby, the man who gives his name to this book, was exempt from my reaction – Gatsby who represented everything for which I have an unaffected scorn[4 - which I have an unaffected scorn – всё, что я искренне презирал и презираю].

There was something gorgeous about him, some heightened sensitivity to the promises of life[5 - promises of life – посулы жизни], as if he were related to[6 - as if he were related to – словно он был частью] one of those intricate machines that register earthquakes ten thousand miles away. It was an extraordinary gift for hope, a romantic readiness such as I have never found in any other person.

My family have been prominent, well-to-do people for three generations. The Carraways[7 - Carraways – Каррауэи] are something of a clan. I graduated from New Haven[8 - New Haven – имеется в виду Йельский университет (который находится в городе Нью-Хейвен)] in 1915, then I decided to go east and learn the bond business[9 - bond business – кредитное дело]. Father agreed to finance me for a year and after various delays I came east, permanently, I thought, in the spring of twenty-two[10 - in the spring of twenty-two – весной 1922 года].

I had an old Dodge[11 - Dodge – «додж», марка автомобиля] and a Finnish woman who made my bed and cooked breakfast.

I bought a dozen volumes on banking and credit and investment securities and they stood on my shelf in red and gold.

I lived at West Egg[12 - West Egg – Уэст-Эгг]. My house was between two huge places that rented for twelve or fifteen thousand a season. The one on my right was Gatsby's mansion.

Across the bay the white palaces of fashionable East Egg glittered along the water, and the history of the summer really begins on the evening I drove over there to have dinner with the Buchanans[13 - Buchanan – Бьюкенен]. Daisy[14 - Daisy – Дэзи] was my second cousin[15 - second cousin – троюродная сестра]. Her husband's family was enormously wealthy – even in college his freedom with money was a matter for reproach[16 - was a matter for reproach – вызывала нарекания]. Why they came east I don't know. They had spent a year in France, for no particular reason, and then drifted here and there.

Their house was even more elaborate than I expected. The lawn started at the beach and ran toward the front door for a quarter of a mile. Tom had changed since his New Haven years. Now he was a sturdy, straw haired man of thirty with a rather hard mouth[17 - a rather hard mouth – твёрдо очерченный рот] and a supercilious manner.

It was a body capable of enormous leverage[18 - enormous leverage – сокрушительная сила] – a cruel body.

“Now, don't think my opinion on these matters is final,” he seemed to say, “just because I'm stronger and more of a man than you are.” We were in the same Senior Society[19 - Senior Society – студенческое общество], and while we were never intimate I always had the impression that he wanted me to like him.

“I've got a nice place here,” he said. He turned me around again, politely and abruptly. “We'll go inside.”

We walked through a high hallway into a bright rosy-colored space. The only completely stationary object in the room was an enormous couch on which two young women were lying. The younger of the two was a stranger to me. The other girl, Daisy, made an attempt to rise. She murmured that the surname of the other girl was Baker.

My cousin began to ask me questions in her low, thrilling voice. Her face was sad and lovely with bright things in it, bright eyes and a bright passionate mouth.

“You ought to see the baby,” she said.

“I'd like to.”

“She's asleep. She's three years old. Haven't you ever seen her?”

“Never.”

Tom Buchanan stopped and rested his hand on my shoulder.

“What you doing, Nick?”

“I'm a bond man[20 - I'm a bond man. – Я занимаюсь кредитными операциями.].”

“Who with?”

I told him.

“Never heard of them,” he remarked.

This annoyed me[21 - This annoyed me. – Это меня задело.].

“You will,” I answered shortly. “You will if you stay in the East.”

“Oh, I'll stay in the East, don't you worry,” he said, glancing at Daisy and then back at me.

At this point Miss Baker said “Absolutely!” It was the first word she uttered since I came into the room. It surprised her as much as it did me.

I looked at Miss Baker, I enjoyed looking at her. She was a slender girl, with an erect carriage[22 - with an erect carriage – с очень прямой спиной]. It occurred to me now that I had seen her, or a picture of her, somewhere before.

“You live in West Egg,” she remarked contemptuously. “I know somebody there.”

“I don't know a single – ”

“You must know Gatsby.”

“Gatsby?” demanded Daisy. “What Gatsby?”

Before I could reply that he was my neighbour dinner was announced. We went out.

“Civilization's going to pieces,” said Tom. “We don't look out the white race will be submerged. It's all scientific stuff; it's been proved.”

The telephone rang and Tom left. Daisy suddenly threw her napkin on the table and excused herself and went into the house, too.

“Tom's got some woman in New York[23 - Tom's got some woman in New York. – У Тома есть женщина в Нью-Йорке.],” said Miss Baker. “She might have the decency not to telephone him at dinner-time. Don't you think?”

Tom and Daisy were back at the table.

“We don't know each other very well, Nick,” said Daisy. “Well, I've had a very bad time, and I'm pretty cynical about everything. I think everything's terrible anyhow. I KNOW. I've been everywhere and seen everything and done everything.”

Chapter 2

Tom Buchanan had a mistress[24 - mistress – любовница]. Though I was curious to see her I had no desire to meet her – but I did. I went up to New York with Tom on the train one afternoon and when we stopped he jumped to his feet.

“We're getting off!” he insisted. “I want you to meet my girl.”

I followed him over a low white-washed railroad fence. I saw a garage – Repairs. GEORGE B. WILSON. Cars Bought and Sold[25 - Repairs. GEORGE B. WILSON. Cars Bought and Sold – Джордж Уилсон. Автомобили. Покупка, продажа и ремонт.] – and I followed Tom inside.

“Hello, Wilson, old man,” said Tom, “How's business?”

“I can't complain,” answered Wilson. “When are you going to sell me that car?”

“Next week.”

Then I saw a woman. She was in the middle thirties[26 - She was in the middle thirties. – Она была лет тридцати пяти.], and faintly stout[27 - faintly stout – с наклонностью к полноте], but she carried her surplus flesh sensuously as some women can. She smiled slowly and walking through her husband as if he were a ghost shook hands with Tom. Then she spoke to her husband in a soft, coarse voice:

“Get some chairs, why don't you, so somebody can sit down.”

“Oh, sure,” agreed Wilson and went toward the little office.

“I want to see you,” said Tom intently. “Get on the next train.”

“All right.”

“I'll meet you by the news-stand.”

She nodded and moved away from him.

We waited for her down the road and out of sight.

“Terrible place, isn't it,” said Tom.

“Awful.”

“It does her good to get away[28 - It does her good to get away. – Она и бывает рада проветриться.].”

“Doesn't her husband object?”

“Wilson? He thinks she goes to see her sister in New York. “

“Myrtle'll[29 - Myrtle – Миртл] be hurt if you don't come up to the apartment,” said Tom.

I have been drunk just twice in my life and the second time was that afternoon. Some people came – Myrtle's sister, Catherine, Mr. McKee, a pale feminine man from the flat below, and his wife. She told me with pride that her husband had photographed her a hundred and twenty-seven times since they had been married.

The sister Catherine sat down beside me on the couch.

“Where do you live?” she inquired.

“I live at West Egg.”

“Really? I was down there at a party about a month ago. At a man named Gatsby's. Do you know him?”

“I live next door to him.”

“Well, they say he's a nephew or a cousin of Kaiser Wilhelm's[30 - Kaiser Wilhelm – кайзер Вильгельм]. That's where all his money comes from.”

“Really?”

She nodded.

“I'm scared of him. I'd hate to have him get anything on me.”

Catherine leaned close to me and whispered in my ear: “Neither of them can stand the person they're married to.” She looked at Myrtle and then at Tom.

The answer to this came from Myrtle.

“I made a mistake,” she declared vigorously. “I married him because I thought he was a gentleman, but he wasn't fit to lick my shoe[31 - He wasn't fit to lick my shoe. – Он мне в подмётки не годился.].”

Chapter 3

There was music from my neighbour's house through the summer nights. In his blue gardens men and girls came and went like moths among the whisperings and the champagne and the stars. In the afternoon I watched his guests diving from the tower of his raft or taking the sun on the hot sand of his beach. On week-ends his Rolls-Royce[32 - Rolls-Royce – «Роллс-ройс»] became an omnibus, bearing parties to and from the city between nine in the morning and long past midnight, while his station wagon scampered like a brisk yellow bug to meet all trains. And on Mondays eight servants toiled all day with mops and brushes and hammers, repairing the ravages of the night before.

Every Friday five crates of oranges and lemons arrived from a fruiterer in New York – every Monday these same oranges and lemons left his back door in a pyramid of pulpless halves. There was a machine in the kitchen which could extract the juice of two hundred oranges in half an hour, if a little button was pressed two hundred times by a butler's thumb.

At least once a fortnight a corps of caterers came down with several hundred feet of canvas and enough colored lights to make a Christmas tree of Gatsby's enormous garden. On buffet tables, garnished with glistening hors-d'oeuvre, spiced baked hams crowded against salads of harlequin designs and pastry pigs and turkeys bewitched to a dark gold. In the main hall a bar with a real brass rail was set up, and stocked with gins and liquors and with cordials so long forgotten that most of his female guests were too young to know one from another.

When I went to Gatsby's house I was one of the few guests who had actually been invited[33 - one of the few guests who had actually been invited – один из немногих действительно приглашённых гостей]. People were not invited – they went there. They got into automobiles which bore them out to Long Island[34 - Long Island – Лонг-Айленд] and somehow they ended up at Gatsby's door. Sometimes they came and went without having met Gatsby at all.

I had been actually invited. A chauffeur in a uniform gave me a formal note from his employer – the honor would be entirely Jay Gatsby's[35 - the honor would be entirely Jay Gatsby's – Джей Гэтсби почтёт для себя величайшей честью], it said, if I would attend his little party that night.

Dressed up in white flannels I went over to his lawn a little after seven. I was immediately struck by the number of young Englishmen dotted about; all well dressed, all looking a little hungry.

As soon as I arrived I made an attempt to find my host but the two or three people of whom I asked his whereabouts stared at me in such an amazed way and denied so vehemently any knowledge of his movements that I slunk off in the direction of the cocktail table – the only place in the garden where a single man could linger without looking purposeless and alone.

I noticed Jordan Baker with two girls in yellow dresses.

“Hello!” they cried together.

“Are you looking for Gatsby?” asked the first girl.

“There's something funny about him,” said the other girl eagerly. “Somebody told me they thought he killed a man once.”

“I don't think it's so much THAT[36 - I don't think it's so much that. – Не думаю, что дело в этом.],” argued her friend. “It's more that he was a German spy during the war.”

“Oh, no,” said the first girl. “I'll bet he killed a man.”

I tried to find the host. Champagne was served in glasses bigger than finger bowls.

The moon had risen higher. I was still with Jordan Baker. We were sitting at a table with a man of about my age. I was enjoying myself now. I had taken two finger-bowls of champagne and the scene had changed before my eyes into something significant, elemental and profound.

The man looked at me and smiled.

“Your face is familiar,” he said, politely. “Weren't you in the Third Division during the war?”

“Why, yes.”

“Oh! I knew I'd seen you somewhere before.”

He told me that he had just bought a hydroplane and was going to try it out in the morning.

“Want to go with me, old sport[37 - old sport – старина]?”

“What time?”

“Any time that suits you best.”

“This is an unusual party for me. I haven't even seen the host. This man Gatsby sent over his chauffeur with an invitation.”

For a moment he looked at me as if he failed to understand.

“I'm Gatsby,” he said suddenly.

“What!” I exclaimed. “Oh, I beg your pardon.”

“I thought you knew, old sport. I'm afraid I'm not a very good host.”

He smiled understandingly – much more than understandingly. It was one of those rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it, that you may come across[38 - come across – встретить] four or five times in life. It faced – or seemed to face – the whole external world for an instant, and then concentrated on YOU with an irresistible prejudice in your favor. It understood you just so far as you wanted to be understood, believed in you as you would like to believe in yourself and assured you that it had precisely the impression of you that, at your best, you hoped to convey. Precisely at that point it vanished – and I was looking at an elegant young rough-neck, a year or two over thirty, whose elaborate formality of speech just missed being absurd. Some time before he introduced himself I'd got a strong impression that he was picking his words with care.

Almost at the moment when Mr. Gatsby identified himself a servant hurried toward him with the information that Chicago was calling him on the wire. He excused himself with a small bow.

“If you want anything just ask for it, old sport,” he urged me. “Excuse me. I will rejoin you later.”

When he was gone I turned immediately to Jordan.

“Who is he?” I demanded. “Do you know?”

“He's just a man named Gatsby.”

“Where is he from, I mean? And what does he do?”

“Well, he told me once he was an Oxford man[39 - He was an Oxford man. – Он учился в Оксфорде.]. However, I don't believe it.”

“Why not?”

“I don't know,” she insisted, “I just don't think he went there. Anyhow he gives large parties. And I like large parties. They're so intimate. At small parties there isn't any privacy.”

Jordan Baker instinctively avoided clever men. She was incurably dishonest[40 - incurably dishonest – неисправимо бесчестна]. But dishonesty in a woman is a thing you never blame deeply. Every one suspects himself of at least one of the cardinal virtues, and this is mine: I am one of the few honest people that I have ever known.

Chapter 4

On Sunday morning while church bells rang in the villages along shore everybody returned to Gatsby's house.

“He's a bootlegger[41 - bootlegger – бутлегер (подпольный торговец спиртным во время сухого закона в США)],” said the young ladies, moving somewhere between his cocktails and his flowers. “One time he killed a man who had found out that he was second cousin to the devil. Reach me a rose, honey, and pour me a last drop into that there crystal glass.”

At nine o'clock, one morning late in July Gatsby's gorgeous car lurched up the rocky drive to my door. It was the first time he had called on me though I had gone to two of his parties, mounted in his hydroplane, and, at his urgent invitation, made frequent use of his beach.

“Good morning, old sport. You're having lunch with me today and I thought we'd ride up together.”

He was balancing himself on the dashboard of his car with that resourcefulness of movement that is so peculiarly American – that comes, I suppose, with the absence of lifting work or rigid sitting in youth and, even more, with the form- less grace of our nervous, sporadic games. This quality was continually breaking through his punctilious manner in the shape of restlessness. He was never quite still; there was always a tapping foot somewhere or the impatient opening and closing of a hand.

He saw me looking with admiration at his car.

“It's pretty, isn't it, old sport.” He jumped off to give me a better view. “Haven't you ever seen it before?”

I'd seen it. Everybody had seen it. It was a rich cream color, bright with nickel, swollen here and there in its monstrous length with triumphant hatboxes and supper-boxes and tool-boxes, and terraced with a labyrinth of windshields that mirrored a dozen suns. Sitting down behind many layers of glass in a sort of green leather conservatory we started to town.

I had talked with him perhaps half a dozen times in the past month and found, to my disappointment, that he had little to say. So my first impression, that he was a person of some undefined consequence, had gradually faded and he had become simply the proprietor of an elaborate roadhouse next door.

And then came that disconcerting ride. We hadn't reached West Egg village before Gatsby began leaving his elegant sentences unfinished and slapping himself indecisively on the knee of his caramel-colored suit.

“Look here, old sport,” he broke out surprisingly. “What's your opinion of me, anyhow?”

A little overwhelmed, I began the generalized evasions which that question deserves.

“Well, I'm going to tell you something about my life,” he said. “I don't want you to get a wrong idea of me from all these stories you hear. I am the son of some wealthy people in the middle-west – all dead now. I was brought up in America but educated at Oxford because all my ancestors have been educated there for many years. It is a family tradition.”

He looked at me sideways – and I knew why Jordan Baker had believed he was lying. He hurried the phrase “educated at Oxford”, or swallowed it or choked on it as though it had bothered him before. And with this doubt his whole statement fell to pieces and I wondered if there wasn't something a little sinister about him after all.

“What part of the middle-west?” I inquired.

“San Francisco. My family all died and I came into a good deal of money[42 - I came into a good deal of money. – Мне досталось большое состояние.]. After that I lived in all the capitals of Europe – Paris, Venice, Rome – collecting jewels, chiefly rubies, hunting, painting a little.”

His voice was solemn as if the memory of that sudden extinction of a clan still haunted him. For a moment I suspected that he was pulling my leg but a glance at him convinced me otherwise.

With an effort I managed to restrain my incredulous laughter. The very phrases were worn so threadbare that they evoked no image except that of a turbaned “character” leaking sawdust at every pore as he pursued a tiger through the Bois de Boulogne.

“Then came the war, old sport. It was a great relief and I tried very hard to die but I seemed to bear an enchanted life. I was promoted to be a major[43 - was promoted to be a major – был произведён в майоры]. Here's a thing I always carry. A souvenir of Oxford days.”

It was a photograph of young men. There was Gatsby, looking a little, not much, younger – with a cricket bat in his hand.

Then it was all true.

“I'm going to make a big request of you today,” he said, “so I thought you ought to know something about me. I didn't want you to think I was just some nobody.”

The next day I was having dinner with Jordan Baker. Suddenly she said to me, “One October day in nineteen-seventeen – Gatsby met Daisy. They loved each other, but she married Tom Buchanan. Tom was very rich. I know everything, I was bridesmaid. I came into her room half an hour before the bridal dinner, and found her lying on her bed. She had a letter in her hand. I was scared, I can tell you; I'd never seen a girl like that before. She began to cry – she cried and cried.

The next April Daisy had her little girl. About six weeks ago, she heard the name Gatsby for the first time in years. Gatsby bought that house so that Daisy would be just across the bay. He wants to know, if you'll invite Daisy to your house some afternoon and then let him come over[44 - let him come over – позволить ему зайти].”

The modesty of the demand shook me.

“He's afraid. He's waited so long. He wants her to see his house,” she explained. “And your house is right next door.”

“Does Daisy want to see Gatsby?”

“She's not to know about it. Gatsby doesn't want her to know. You're just supposed to invite her to tea.”

Chapter 5

When I came home to West Egg that night I was afraid for a moment that my house was on fire. Two o'clock and the whole corner of the peninsula was blazing with light which fell unreal on the shrubbery and made thin elongating glints upon the roadside wires. Turning a corner I saw that it was Gatsby's house, lit from tower to cellar.

At first I thought it was another party, a wild rout that had resolved itself into “hide-and-go-seek” or “sardines-in-the-box” with all the house thrown open to the game. But there wasn't a sound. Only wind in the trees which blew the wires and made the lights go off and on again as if the house had winked into the darkness. As my taxi groaned away I saw Gatsby walking toward me across his lawn.

“Your place looks like the world's fair,” I said.

“Does it?” He turned his eyes toward it absently. “I have been glancing into some of the rooms. Let's go to Coney Island, old sport. In my car.”

“It's too late.”

“Well, suppose we take a plunge in the swimming pool? I haven't made use of it all summer.”

“I've got to go to bed.”

“All right.”

He waited, looking at me with suppressed eagerness.

“I talked with Miss Baker,” I said after a moment. “I'm going to call up Daisy tomorrow and invite her over here to tea.”

“Oh, that's all right,” he said carelessly. “I don't want to put you to any trouble.”

“What day would suit you?”

“What day would suit YOU?” he corrected me quickly. “I don't want to put you to any trouble, you see.”

“How about the day after tomorrow?” He considered for a moment. Then, with reluctance:

“I want to get the grass cut,” he said.

We both looked at the grass – there was a sharp line where my ragged lawn ended and the darker, well-kept expanse of his began. I suspected that he meant my grass.

“There's another little thing,” he said uncertainly, and hesitated.

“Would you rather put it off for a few days?” I asked.

“Oh, it isn't about that. At least – ” He fumbled with a series of beginnings. “Why, I thought – why, look here, old sport, you don't make much money, do you?”

“Not very much.”

This seemed to reassure him and he continued more confidently.

“I thought you didn't, if you'll pardon my – you see, I carry on a little business on the side, a sort of sideline, you understand. And I thought that if you don't make very much – You're selling bonds, aren't you, old sport?”

“Trying to.”

“Well, this would interest you. It wouldn't take up much of your time and you might pick up a nice bit of money. It happens to be a rather confidential sort of thing.”

I realize now that under different circumstances that conversation might have been one of the crises of my life. But, because the offer was obviously and tactlessly for a service to be rendered, I had no choice except to cut him off there.

I called up Daisy from the office next morning and invited her to come to tea.

“Don't bring Tom,” I warned her.

“What?”

“Don't bring Tom.”

“Who is Tom?” she asked innocently.

The day agreed upon was pouring rain.

At eleven o'clock a man in a raincoat tapped at my front door and said that Mr. Gatsby had sent him over to cut my grass.

At two o'clock a greenhouse arrived from Gatsby's, with innumerable receptacles to contain it.

An hour later the front door opened nervously, and Gatsby in a white flannel suit, silver shirt and gold-colored tie hurried in. He was pale and there were dark signs of sleeplessness beneath his eyes.

“Is everything all right?” he asked immediately.

“The grass looks fine, if that's what you mean.”

“What grass?” he inquired blankly. “Oh, the grass in the yard.” He looked out the window at it, but judging from his expression I don't believe he saw a thing.

“Looks very good,” he remarked vaguely.

I took him into the pantry where he looked a little reproachfully at the Finn. Together we scrutinized the twelve lemon cakes from the delicatessen shop.

“Will they do?” I asked.

“Of course, of course! They're fine!” and he added hollowly, “…old sport.”

“Nobody's coming to tea. It's too late!” He looked at his watch as if there was some pressing demand on his time elsewhere. “I can't wait all day.”

“Don't be silly; it's just two minutes to four.”

He sat down, miserably, as if I had pushed him, and simultaneously there was the sound of a motor turning into my lane. We both jumped up and, a little harrowed myself, I went out into the yard.

Under the dripping bare lilac trees a large open car was coming up the drive. It stopped. Daisy's face, tipped sideways beneath a three-cornered lavender hat, looked out at me with a bright ecstatic smile.

“Is this absolutely where you live, my dearest one?”

The exhilarating ripple of her voice was a wild tonic in the rain. I had to follow the sound of it for a moment, up and down, with my ear alone before any words came through. A damp streak of hair lay like a dash of blue paint across her cheek and her hand was wet with glistening drops as I took it to help her from the car.

“Are you in love with me,” she said low in my ear. “Or why did I have to come alone?”

“That's the secret of Castle Rackrent. Tell your chauffeur to go far away and spend an hour.”

We went in. To my overwhelming surprise the living room was deserted.

“Well, that's funny!” I exclaimed.

“What's funny?”

She turned her head as there was a light, dignified knocking at the front door. I went out and opened it. Gatsby, pale as death, with his hands plunged like weights in his coat pockets, was standing in a puddle of water glaring tragically into my eyes.

With his hands still in his coat pockets he stalked by me into the hall, turned sharply as if he were on a wire and disappeared into the living room. It wasn't a bit funny. Aware of the loud beating of my own heart I pulled the door to against the increasing rain.

For half a minute there wasn't a sound. Then from the living room I heard a sort of choking murmur and part of a laugh followed by Daisy's voice on a clear artificial note.

“I certainly am awfully glad to see you again.”

“We haven't met for many years,” said Daisy, her voice as matter-of-fact as it could ever be.

“Five years next November.”

The automatic quality of Gatsby's answer set us all back at least another minute. I had them both on their feet with the desperate suggestion that they help me make tea in the kitchen when the demoniac Finn brought it in on a tray.

Amid the welcome confusion of cups and cakes a certain physical decency established itself. Gatsby got himself into a shadow and while Daisy and I talked looked conscientiously from one to the other of us with tense unhappy eyes. However, as calmness wasn't an end in itself I made an excuse at the first possible moment and got to my feet.

“Where are you going?” demanded Gatsby in immediate alarm.

“I'll be back.”

“I've got to speak to you about something before you go.”

He followed me wildly into the kitchen, closed the door and whispered: “Oh, God!” in a miserable way.

“What's the matter?”

“This is a terrible mistake,” he said, shaking his head from side to side, “a terrible, terrible mistake.”

“You're just embarrassed, that's all,” and luckily I added, “Daisy's embarrassed too.”

“She's embarrassed?” he repeated incredulously.

“Just as much as you are.”

“Don't talk so loud.”

“You're acting like a little boy,” I broke out impatiently. “Not only that but you're rude. Daisy's sitting in there all alone.”

He raised his hand to stop my words, looked at me with unforgettable reproach and opening the door cautiously went back into the other room.

I went in – after making every possible noise in the kitchen short of pushing over the stove – but I don't believe they heard a sound. They were sitting at either end of the couch looking at each other as if some question had been asked or was in the air, and every vestige of embarrassment was gone. Daisy's face was smeared with tears and when I came in she jumped up and began wiping at it with her handkerchief before a mirror. But there was a change in Gatsby that was simply confounding. He literally glowed; without a word or a gesture of exultation a new well-being radiated from him and filled the little room.

“Oh, hello, old sport,” he said, as if he hadn't seen me for years. I thought for a moment he was going to shake hands.

“I want you and Daisy to come over to my house,” he said, “I'd like to show her around.”

“You're sure you want me to come?”

“Absolutely, old sport.”

Daisy went upstairs to wash her face – too late I thought with humiliation of my towels – while Gatsby and I waited on the lawn.

“My house looks well, doesn't it?” he demanded. “See how the whole front of it catches the light.”

I agreed that it was splendid.

“Yes.” His eyes went over it, every arched door and square tower. “It took me just three years to earn the money that bought it.”

“I thought you inherited your money.”

“I did, old sport,” he said automatically, “but I lost most of it in the big panic – the panic of the war.”

I think he hardly knew what he was saying, for when I asked him what business he was in he answered “That's my affair,” before he realized that it wasn't the appropriate reply.

“Oh, I've been in several things[45 - I've been in several things. – Я много чем занимался.],” he corrected himself. “I was in the drug business and then I was in the oil business. But I'm not in either one now.”

Before I could answer, Daisy came out of the house and two rows of brass buttons on her dress gleamed in the sunlight.

“That huge place THERE?” she cried pointing.

“Do you like it?”

“I love it, but I don't see how you live there all alone.”

“I keep it always full of interesting people, night and day. People who do interesting things. Celebrated people.”

Daisy admired everything: the house, the gardens, the beach.

He hadn't once ceased looking at Daisy and I think he revalued everything in his house according to the measure of response it drew from her well-loved eyes. Sometimes, too, he stared around at his possessions in a dazed way as though in her actual and astounding presence none of it was any longer real. Once he nearly toppled down a flight of stairs.

His bedroom was the simplest room of all – except where the dresser was garnished with a toilet set of pure dull gold. Daisy took the brush with delight and smoothed her hair, whereupon Gatsby sat down and shaded his eyes and began to laugh.

Recovering himself in a minute he opened for us two hulking patent cabinets which held his massed suits and dressing-gowns and ties, and his shirts, piled like bricks in stacks a dozen high.

“I've got a man in England who buys me clothes. He sends over a selection of things at the beginning of each season, spring and fall.”

He took out a pile of shirts and began throwing them, one by one before us, shirts of sheer linen and thick silk and fine flannel which lost their folds as they fell and covered the table in many-colored disarray. While we admired he brought more and the soft rich heap mounted higher – shirts with stripes and scrolls and plaids in coral and apple-green and lavender and faint orange with monograms of Indian blue. Suddenly with a strained sound, Daisy bent her head into the shirts and began to cry stormily.

“They're such beautiful shirts,” she sobbed, her voice muffled in the thick folds. “It makes me sad because I've never seen such – such beautiful shirts before.”

Daisy put her arm through his abruptly. I began to walk about the room, examining various objects. A large photograph of an elderly man in yachting costume attracted me, hung on the wall over his desk.

“Who's this?”

“That's Mr. Dan Cody[46 - Dan Cody – Дэн Коди], old sport. He's dead now. He used to be my best friend years ago.”

There was a small picture of Gatsby, also in yachting costume – taken apparently when he was about eighteen.

“I adore it!” exclaimed Daisy.

After the house, we were to see the grounds and the swimming pool, and the hydroplane and the midsummer flowers – but outside Gatsby's window it began to rain again so we stood in a row looking at the corrugated surface of the Sound.

Almost five years! His hand took hold of hers and as she said something low in his ear he turned toward her with a rush of emotion. They had forgotten me, Gatsby didn't know me now at all. I looked once more at them and went out of the room, leaving them there together.

Chapter 6

James Gatz[47 - James Gatz – Джеймс Гетц] – that was his name. He had changed it at the age of seventeen and at the specific moment – when he saw Dan Cody's yacht. It was James Gatz who had been loafing along the beach that afternoon, but it was already Jay Gatsby who borrowed a row-boat and informed Cody that a wind might catch him and break him up in half an hour.

His parents were unsuccessful farm people – his imagination had never really accepted them as his parents at all. So he invented Jay Gatsby, and to this conception he was faithful to the end.

Dan Cody was fifty years old then, he was a millionaire, and an infinite number of women tried to separate him from his money. To the young Gatz the yacht represented all the beauty and glamour in the world. Cody asked him a few questions and found that he was clever, and extravagantly ambitious. A few days later he bought him a blue coat, six pairs of white trousers and a yachting cap.

He was employed as a steward, skipper, and secretary. The arrangement lasted five years during which the boat went three times around the continent. In Boston Dan Cody died.

He told me all this very much later.

For several weeks I didn't see him or hear his voice on the phone. But finally I went over to his house one Sunday afternoon. I hadn't been there two minutes[48 - I hadn't been there two minutes. – Я не просидел и пары минут.] when somebody brought Tom Buchanan in for a drink.

“I'm delighted to see you,” said Gatsby. “Sit right down. Have a cigarette or a cigar.” He walked around the room quickly, ringing bells. “I'll have something to drink for you in just a minute.”

He was profoundly affected by the fact that Tom was there.

“I believe we've met somewhere before, Mr. Buchanan. I know your wife,” continued Gatsby.

“That so?[49 - That so? – Неужели?]“

Tom turned to me.

“You live near here, Nick?”

“Next door.”

“That so?”

Tom was evidently perturbed at Daisy's running around alone, for on the following Saturday night he came with her to Gatsby's party. Daisy's voice was playing murmurous tricks in her throat.

“These things excite me SO,” she whispered.

“Look around,” suggested Gatsby. “You must see the faces of many people you've heard about.”

Daisy and Gatsby danced. I remember being surprised[50 - I remember being surprised – Я помню, как меня удивил.] by his graceful, conservative fox-trot – I had never seen him dance[51 - I had never seen him dance – Я никогда не видел его раньше танцующим.] before. Then they came to my house and sat on the steps for half an hour while at her request I remained watchfully in the garden.

The party was over. I sat on the front steps with them while they waited for their car. It was dark here in front of the house.

“Who is this Gatsby anyhow?” demanded Tom suddenly. “Some big bootlegger?”

“Where'd you hear that?” I inquired.

“I didn't hear it. I imagined it. A lot of these newly rich people are just big bootleggers, you know.”

“Not Gatsby,” I said shortly.

He was silent for a moment.

“I'd like to know who he is and what he does,” insisted Tom. “And I think I'll make a point of finding out[52 - I'll make a point of finding out. – Я постараюсь это выяснить.].”

“I can tell you right now,” answered Daisy. “He owned some drug stores, a lot of drug stores. He built them up himself.”

The dilatory limousine came rolling up the drive.

“Good night, Nick,” said Daisy.

Gatsby was silent.

“I feel far away from her,” he said.

He wanted nothing less of Daisy than that she should go to Tom and say, “I never loved you.”

“You can't repeat the past.”

“Can't repeat the past?” he cried incredulously. “Why of course[53 - of course – конечно] you can!”

He looked around him wildly, as if the past were lurking here in the shadow of his house.

“I'm going to fix everything just the way it was before,” he said, nodding determinedly.

Chapter 7

It was when curiosity about Gatsby was at its highest that the lights in his house failed to go on one Saturday night – and, as obscurely as it had begun, his career as Trimalchio[54 - Trimalchio – Тримальхион, герой сатирического романа Петрония «Сатирикон», вольноотпущенник и нувориш, задающий роскошные пиры] was over.

Only gradually did I become aware that the automobiles which turned expectantly into his drive stayed for just a minute and then drove sulkily away. Wondering if he were sick I went over to find out – an unfamiliar butler with a villainous face squinted at me suspiciously from the door.

“Is Mr. Gatsby sick?”

“Nope.” After a pause he added “sir” in a dilatory, grudging way.

“I hadn't seen him around, and I was rather worried. Tell him Mr. Carraway came over.”

“Who?” he demanded rudely.

“Carraway.”

“Carraway. All right, I'll tell him.” Abruptly he slammed the door.

My Finn informed me that Gatsby had dismissed every servant in his house a week ago and replaced them with half a dozen others, who never went into West Egg Village to be bribed by the tradesmen, but ordered moderate supplies over the telephone. The grocery boy reported that the kitchen looked like a pigsty, and the general opinion in the village was that the new people weren't servants at all.

Next day Gatsby called me on the phone.

“Going away?” I inquired.

“No, old sport.”

“I hear you fired all your servants.”

“I wanted somebody who wouldn't gossip. Daisy comes over quite often – in the afternoons.”

He was calling up at Daisy's request – would I come to lunch at her house tomorrow? Miss Baker would be there. Half an hour later Daisy herself telephoned and seemed relieved to find that I was coming. I couldn't believe that they would choose this occasion for a scene[55 - would choose this occasion for a scene – собираются воспользоваться случаем, чтобы устроить сцену].

The next day I stood before the Buchanans' house.

“Madame expects you in the salon!” cried the servant.

Gatsby stood in the center of the crimson carpet and gazed around with fascinated eyes. Daisy watched him and laughed, her sweet, exciting laugh.

We were silent. Tom opened the door, blocked out its space for a moment with his thick body, and hurried into the room.

“Mr. Gatsby! I'm glad to see you, sir… Nick…”

“Make us a cold drink,” cried Daisy.

As he left the room again she got up and went over to Gatsby and pulled his face down kissing him on the mouth.

“You know I love you,” she murmured. “I don't care!”

Daisy sat back upon the couch.

“It's so hot,” said Daisy. “Let's all go to town! Who wants to go to town?”

“Let's go! Come on, come on!” said Tom.

“I can't say anything in his house, old sport,” said Gatsby to me. “Her voice is full of money,” he said suddenly.

That was it. I'd never understood before. It was full of money.

“Shall we all go in my car?” suggested Gatsby.

“Well, you take mine and let me drive your car to town,” offered Tom.

“I don't think there's much gas,” said Gatsby.

Daisy walked close to Gatsby, touching his coat with her hand. Jordan and Tom and I got into the front seat of Gatsby's car.

“You think I'm pretty dumb, don't you?” suggested Tom. “Perhaps I am, but I have a – almost a second sight, sometimes. I've made a small investigation of this fellow,” he continued. “I'd been making a small investigation of his past.”

“And you found he was an Oxford man,” said Jordan helpfully.

“An Oxford man!” He was incredulous. “Like hell he is![56 - Like hell he is! – Чёрта с два!]”

“Listen, Tom. Why did you invite him to lunch?” demanded Jordan.

“Daisy invited him; she knew him before we were married!”

The car began to make strange sounds. I remembered Gatsby's caution about gasoline.

“There's a garage right here,” objected Jordan.

Tom threw on both brakes impatiently and we came to a dusty stop under Wilson's sign.

“Let's have some gas!” cried Tom roughly. “What do you think we stopped for – to admire the view?”

“I'm sick,” said Wilson without moving. “I've been sick all day.”

“Well, shall I help myself?” Tom demanded.

With an effort Wilson left the shade and unscrewed the cap of the tank. In the sunlight his face was green.

“I've been here too long. I want to get away. My wife and I want to go west.”

“Your wife does!” exclaimed Tom.

“She's been talking about it for ten years. I'm going to get her away. I learned something,” remarked Wilson. “That's why I want to get away.”

Tom was feeling the hot whips of panic. His wife and his mistress were slipping from his control.

“You follow me to the south side of Central Park, in front of the Plaza,” said he.

Several times he turned his head and looked back for their car. I think he was afraid they would dart down a side street and out of his life forever.

We all decided to take the suite in the Plaza Hotel.

The room was large and stifling. Daisy went to the mirror and stood with her back to us, fixing her hair.

“It's a great suite,” whispered Jordan respectfully and every one laughed.

“Open another window,” commanded Daisy, without turning around.

“The thing to do is to forget about the heat,” said Tom impatiently. “You make it ten times worse by crabbing about it.”

He unrolled the bottle of whiskey from the towel and put it on the table.

“Why not let her alone, old sport?” remarked Gatsby. “You're the one that wanted to come to town.”

There was a moment of silence.

“Where'd you pick that up – this 'old sport'?”

“Now see here, Tom,” said Daisy, turning around from the mirror, “if you're going to make personal remarks I won't stay here a minute.”

“By the way, Mr. Gatsby, I understand you're an Oxford man.”

“Not exactly.”

“Oh, yes. It was in nineteen-nineteen, I only stayed five months. That's why I can't really call myself an Oxford man.”

Daisy rose, smiling faintly, and went to the table.

“Open the whiskey, Tom,” she ordered. “Then you won't seem so stupid to yourself.”

“Wait a minute,” said Tom, “I want to said Mr. Gatsby some words.”

“Go on,” Gatsby said politely.

“I suppose the latest thing is to sit back and let Mr. Nobody from Nowhere[57 - Mr. Nobody from Nowhere – мистер Невесть Кто, Невесть Откуда] make love to your wife!” “I know I'm not very popular. I don't give big parties.”

Angry as I was[58 - Angry as I was – как я ни был зол.], I was tempted to laugh whenever he opened his mouth.

“I've got something to tell YOU, old sport, – ” began Gatsby. But Daisy interrupted helplessly.

“Please don't! Please let's all go home. Why don't we all go home?”

“That's a good idea.” I got up. “Come on, Tom. Nobody wants a drink.”

“I want to know what Mr. Gatsby has to tell me.”

“Your wife doesn't love you,” said Gatsby. “She's never loved you. She loves me.”

“You must be crazy!” exclaimed Tom automatically.

Gatsby sprang to his feet, vivid with excitement.

“She never loved you, do you hear?” he cried. “She only married you because I was poor and she was tired of waiting for me. It was a terrible mistake, but in her heart she never loved any one except me!”

At this point Jordan and I tried to go but Tom and Gatsby insisted with competitive firmness that we remain – as though neither of them had anything to conceal and it would be a privilege to partake vicariously of their emotions.

“Sit down, Daisy.” Tom's voice groped unsuccessfully for the paternal note. “What's been going on? I want to hear all about it.”

“I told you what's going on,” said Gatsby. “Going on for five years – and you didn't know.”

Tom turned to Daisy sharply.

“You've been seeing this fellow[59 - You've been seeing this fellow – Ты встречалась с этим типом.] for five years?”

“Not seeing,” said Gatsby. “No, we couldn't meet. But both of us loved each other all that time, old sport, and you didn't know. I used to laugh sometimes – ” but there was no laughter in his eyes, “to think that you didn't know.”

“Oh – that's all.” Tom tapped his thick fingers together like a clergyman and leaned back in his chair.

“You're crazy!” he exploded. “I can't speak about what happened five years ago, because I didn't know Daisy then – and I'll be damned if I see how you got within a mile of her unless you brought the groceries to the back door. But all the rest of that's a God Damned lie. Daisy loved me when she married me and she loves me now.”

“No,” said Gatsby, shaking his head.

“She does, though. The trouble is that sometimes she gets foolish ideas in her head and doesn't know what she's doing.” He nodded sagely. “And what's more, I love Daisy too. Once in a while I go off on a spree and make a fool of myself, but I always come back, and in my heart I love her all the time.”

“You're revolting,” said Daisy. She turned to me, and her voice, dropping an octave lower, filled the room with thrilling scorn: “Do you know why we left Chicago? I'm surprised that they didn't treat you to the story of that little spree.”

Gatsby walked over and stood beside her.

“Daisy, that's all over now,” he said earnestly. “It doesn't matter any more. Just tell him the truth – that you never loved him – and it's all wiped out forever.”

She looked at him blindly. “Why, – how could I love him – possibly?”

“You never loved him.”

She hesitated. Her eyes fell on Jordan and me with a sort of appeal, as though she realized at last what she was doing – and as though she had never, all along, intended doing anything at all. But it was done now. It was too late.

“I never loved him,” she said, with perceptible reluctance.

“Not that day I carried you down from the Punch Bowl to keep your shoes dry?” There was a husky tenderness in his tone. “…Daisy?”

“Please don't.” Her voice was cold, but the rancour was gone from it. She looked at Gatsby. “There, Jay,” she said – but her hand as she tried to light a cigarette was trembling. Suddenly she threw the cigarette and the burning match on the carpet.

“Oh, you want too much!” she cried to Gatsby. “I love you now – isn't that enough? I can't help what's past.” She began to sob helplessly. “I did love him once – but I loved you too.”

Gatsby's eyes opened and closed.

“You loved me TOO?” he repeated.

“Even that's a lie,” said Tom savagely. “She didn't know you were alive. Why, – there're things between Daisy and me that you'll never know, things that neither of us can ever forget.”

The words seemed to bite physically into Gatsby.

“I want to speak to Daisy alone,” he insisted. “She's all excited now – ”

“Even alone I can't say I never loved Tom,” she admitted in a pitiful voice. “It wouldn't be true.”

“Of course it wouldn't,” agreed Tom.

She turned to her husband.

“As if it mattered to you,” she said.

“Of course it matters. I'm going to take better care of you from now on.”

“You don't understand,” said Gatsby, with a touch of panic. “You're not going to take care of her any more.”

“I'm not?” Tom opened his eyes wide and laughed. He could afford to control himself now. “Why's that?”

“Daisy's leaving you.”

“Nonsense.”

“I am, though,” she said with a visible effort.

“She's not leaving me!” Tom's words suddenly leaned down over Gatsby.

“Certainly not for a common swindler who'd have to steal the ring he put on her finger.”

“I won't stand this!” cried Daisy. “Oh, please let's get out.”

“Who are you, anyhow?” broke out Tom. “I've made a little investigation into your affairs. I found out what your 'drug stores' were.” He turned to us and spoke rapidly. “He sold alcohol over the counter.”

“What about it[60 - What about it? – И что из этого?], old sport?” said Gatsby politely.

“Don't you call me 'old sport'!” cried Tom.

I glanced at Daisy who was staring terrified between Gatsby and her husband and at Jordan who had begun to balance an invisible but absorbing object on the tip of her chin. Then I turned back to Gatsby – and was startled at his expression. He looked – and this is said in all contempt for the babbled slander of his garden – as if he had “killed a man.” For a moment the set of his face could be described in just that fantastic way.

It passed, and he began to talk excitedly to Daisy, denying everything, defending his name against accusations that had not been made. But with every word she was drawing further and further into herself, so he gave that up and only the dead dream fought on as the afternoon slipped away, trying to touch what was no longer tangible, struggling unhappily, undespairingly, toward that lost voice across the room.

The voice begged again to go.

“PLEASE, Tom! I can't stand this any more.”

Her frightened eyes told that whatever intentions, whatever courage she had had, were definitely gone.

“You two start on home, Daisy,” said Tom. “In Mr. Gatsby's car.”

She looked at Tom, alarmed now, but he insisted with magnanimous scorn.

“Go on. He won't annoy you. I think he realizes that his presumptuous little flirtation is over.”

They were gone, without a word, snapped out, made accidental, isolated, like ghosts even from our pity.

After a moment Tom got up and began wrapping the unopened bottle of whiskey in the towel.

“Want any of this stuff? Jordan?…Nick?”

I didn't answer.

“Nick?” He asked again.

“What?”

“Want any?”

“No… I just remembered that today's my birthday.”

I was thirty. Before me stretched the portentous menacing road of a new decade.

It was seven o'clock when we got into the coupe with him and started for Long Island. Tom talked incessantly, exulting and laughing, but his voice was as remote from Jordan and me as the foreign clamor on the sidewalk or the tumult of the elevated overhead. Human sympathy has its limits and we were content to let all their tragic arguments fade with the city lights behind. Thirty – the promise of a decade of loneliness, a thinning list of single men to know, a thinning brief-case of enthusiasm, thinning hair. But there was Jordan beside me who, unlike Daisy, was too wise ever to carry well-forgotten dreams from age to age. As we passed over the dark bridge her wan face fell lazily against my coat's shoulder and the formidable stroke of thirty died away with the reassuring pressure of her hand.

So we drove on toward death through the cooling twilight.

The young Greek Michaelis[61 - Michaelis – Михаэлис] was the principal witness at the inquest. He had slept through the heat until after five, when he went to the garage and found George Wilson sick in his office. Michaelis advised him to go to bed but Wilson refused. While his neighbour was trying to persuade him some noise broke out overhead.

“I've got my wife locked in up there[62 - I've got my wife locked in up there. – Там наверху я запер жену.],” explained Wilson calmly. “She's going to stay there till the day after tomorrow and then we're going to move away.”

Michaelis was astonished; they had been neighbours for four years and Wilson had never seemed capable of such a statement[63 - had never seemed capable of such a statement – не казался способным на такое]. He was his wife's man and not his own.

So naturally Michaelis tried to find out what had happened, but Wilson wouldn't say a word. Michaelis took the opportunity to get away, intending to come back later. But he didn't.

A little after seven he was heard Mrs. Wilson's voice, loud and scolding, downstairs in the garage.

“Beat me!” he heard her cry. “Throw me down and beat me, you dirty little coward!”

A moment later she rushed out into the dusk, waving her hands and shouting; before he could move from his door the business was over[64 - the business was over – всё было кончено].

The “death car” as the newspapers called it, didn't stop; it came out of the gathering darkness and then disappeared around the next bend. Michaelis wasn't even sure of its colour – somebody told the first policeman that it was yellow. Myrtle Wilson was lying dead. Her mouth was wide open.

We saw the three or four automobiles and the crowd when we were still some distance away.

“Wreck!” said Tom. “That's good. Wilson'll have a little business at last. We'll take a look, just a look.”

Then he saw Myrtle's body.

“What happened – that's what I want to know!”

“Auto hit her. Instantly killed. She ran out in a road. Son-of-a-bitch didn't even stop the car.”

“I know what kind of car it was!”

Tom drove slowly until we were beyond the bend. In a little while I saw that the tears were overflowing down his face.

“The coward!” he whimpered. “He didn't even stop his car.”

The Buchanans' house floated suddenly toward us through the dark trees. Tom stopped beside the porch.

I hadn't gone twenty yards when I heard my name and Gatsby stepped from between two bushes into the path.

“What are you doing?” I inquired.

“Just standing here, old sport. Did you see any trouble on the road?” he asked after a minute.

“Yes.”

He hesitated.

“Was she killed?”

“Yes.”

“I thought so; I told Daisy I thought so. I got to West Egg by a side road,” he went on, “and left the car in my garage. I don't think anybody saw us but of course I can't be sure. Who was the woman?” he inquired.

“Her name was Wilson. Her husband owns the garage. How did it happen? Was Daisy driving?”

“Yes,” he said after a moment, “but of course I'll say I was. You see, when we left New York she was very nervous – and this woman rushed out… It all happened in a minute but it seemed to me that she wanted to speak to us, thought we were somebody she knew.”

Chapter 8

I couldn't sleep all night; a fog-horn was groaning incessantly on the Sound, and I tossed half-sick between grotesque reality and savage frightening dreams. Toward dawn I heard a taxi go up Gatsby's drive and immediately I jumped out of bed and began to dress – I felt that I had something to tell him, something to warn him about and morning would be too late.

Crossing his lawn I saw that his front door was still open and he was leaning against a table in the hall, heavy with dejection or sleep.

“Nothing happened,” he said wanly. “I waited, and about four o'clock she came to the window and stood there for a minute and then turned out the light.”

His house had never seemed so enormous to me as it did that night when we hunted through the great rooms for cigarettes. We pushed aside curtains that were like pavilions and felt over innumerable feet of dark wall for electric light switches – once I tumbled with a sort of splash upon the keys of a ghostly piano. There was an inexplicable amount of dust everywhere and the rooms were musty as though they hadn't been aired for many days. I found the humidor on an unfamiliar table with two stale dry cigarettes inside. Throwing open the French windows of the drawing-room we sat smoking out into the darkness.

“You ought to go away,” I said. “It's pretty certain they'll trace your car.”

“Go away NOW, old sport?”

“Go to Atlantic City for a week, or up to Montreal.”

He wouldn't consider it. He couldn't possibly leave Daisy until he knew what she was going to do. He was clutching at some last hope and I couldn't bear to shake him free.

It was this night that he told me the strange story of his youth with Dan Cody – told it to me because “Jay Gatsby” had broken up like glass against Tom's hard malice and the long secret extravaganza was played out. I think that he would have acknowledged anything, now, without reserve, but he wanted to talk about Daisy.

She was the first “nice” girl he had ever known. In various unrevealed capacities he had come in contact with such people but always with indiscernible barbed wire between. He found her excitingly desirable. He went to her house, at first with other officers, then alone. It amazed him – he had never been in such a beautiful house before. But what gave it an air of breathless intensity was that Daisy lived there – it was as casual a thing to her as his tent out at camp was to him. There was a ripe mystery about it, a hint of bedrooms upstairs more beautiful and cool than other bedrooms, of gay and radiant activities taking place through its corridors and of romances that were not musty and laid away already in lavender but fresh and breathing and redolent of this year's shining motor cars and of dances whose flowers were scarcely withered. It excited him too that many men had already loved Daisy – it increased her value in his eyes. He felt their presence all about the house, pervading the air with the shades and echoes of still vibrant emotions.

But he knew that he was in Daisy's house by a colossal accident. However glorious might be his future as Jay Gatsby, he was at present a penniless young man without a past, and at any moment the invisible cloak of his uniform might slip from his shoulders. So he made the most of his time. He took what he could get, ravenously and unscrupulously – eventually he took Daisy one still October night, took her because he had no real right to touch her hand.

He might have despised himself, for he had certainly taken her under false pretenses. I don't mean that he had traded on his phantom millions, but he had deliberately given Daisy a sense of security; he let her believe that he was a person from much the same stratum as herself – that he was fully able to take care of her. As a matter of fact he had no such facilities – he had no comfortable family standing behind him and he was liable at the whim of an impersonal government to be blown anywhere about the world.

He knew that Daisy was extraordinary but he didn't realize just how extraordinary a “nice” girl could be. She vanished into her rich house, into her rich, full life, leaving Gatsby – nothing. He felt married to her, that was all.

“I can't describe to you how surprised I was to find out I loved her, old sport. She was in love with me too. She thought I knew a lot because I knew different things from her… Well, there I was, way off my ambitions, getting deeper in love every minute, and all of a sudden I didn't care. What was the use of doing great things if I could have a better time telling her what I was going to do?”

I didn't want to go to the city.

“I'll call you up,” I said finally.

“Do, old sport.”

“I'll call you about noon.”

We walked slowly down the steps.

“I suppose Daisy'll call too.”

“I suppose so.”

“Well – goodbye.”

We shook hands. I remembered something and turned around.

“They're a rotten crowd[65 - They're a rotten crowd. – Ничтожества, вот кто они.],” I shouted across the lawn. “You're worth the whole damn bunch put together[66 - You're worth the whole damn bunch put together. – Вы один стоите их всех, вместе взятых.].”

George Wilson told Michaelis, “He killed her.”

“Who did?”

“I have a way of finding out. He murdered her.”

“It was an accident, George.”

Wilson shook his head.

“I know,” he said definitely, “It was the man in that car. She ran out to speak to him and he wouldn't stop.”

“I spoke to her,” he muttered, after a long silence. “I told her she might fool me but she couldn't fool God. I said 'God knows what you've been doing, everything you've been doing.'”

Michaelis went home to sleep; when he awoke four hours later and hurried back to the garage, Wilson was gone.

His movements – he was on foot all the time – were afterward traced[67 - were afterward traced – удалось позже проследить]. The police, on the strength of what he said[68 - on the strength of what he said – основываясь на словах] to Michaelis, that he “had a way of finding out,” supposed that he spent that time going from garage to garage inquiring for a yellow car. By half past two he was in West Egg where he asked someone the way to Gatsby's house. So by that time he knew Gatsby's name.

At two o'clock Gatsby put on his bathing suit.

The chauffeur heard the shots. Just that time I drove from the station directly to Gatsby's house. Four of us, the chauffeur, servant, gardener and I, hurried down to the pool. Gatsby was lying in the pool dead.

It was after we brought Gatsby's body toward the house that the gardener saw Wilson's body a little way off in the grass. The holocaust[69 - holocaust – искупительная жертва] was complete.

Chapter 9

Most of those reports were a nightmare – grotesque, circumstantial, eager and untrue. But all this seemed remote.

I called up Daisy half an hour after we found him, called her instinctively and without hesitation. But she and Tom had gone away early that afternoon, and taken baggage with them.

“Left no address?”

“No.”

“Say when they'd be back?”

“No.”

“Any idea where they are? How I could reach them?”

“I don't know. Can't say.”

I wanted to get somebody for him[70 - to get somebody for him – найти ему кого-нибудь]. I wanted to go into the room where he lay and reassure him: “I'll get somebody for you, Gatsby. Don't worry. Just trust me and I'll get somebody for you.”

When the phone rang that afternoon I thought this would be Daisy at last. But I heard a strange man's voice. The name was unfamiliar.

“Young Parke's in trouble,” he said rapidly. “They picked him up[71 - They picked him up. – Его поймали.].”

“Hello!” I interrupted. “Look here – this isn't Mr. Gatsby. Mr. Gatsby's dead.”

There was a long silence on the other end of the wire… then the connection was broken.

On the third day that a telegram signed Henry C. Gatz arrived from a town in Minnesota. It was Gatsby's father.

“I saw it in the Chicago newspaper,” he said. “It was all in the Chicago newspaper. I started right away.”

“I didn't know how to reach you. We were close friends.”

“He had a big future before him, you know. He was only a young man but he had a lot of brain power here.”

“That's true,” I said.

That was all. Daisy hadn't sent a message or a flower. “Blessed are the dead that the rain falls on[72 - Blessed are the dead that the rain falls on. – Блаженны мёртвые, на которых падает дождь.].”

Nobody came to Gatsby's house, but they used to go there by the hundreds.

One afternoon late in October I saw Tom Buchanan. Suddenly he saw me and walked back holding out his hand.

“What's the matter, Nick? Do you object to shaking hands with me?”

“Yes. You know what I think of you.”

“You're crazy, Nick,” he said quickly. “I don't know what's the matter with you.”

“Tom,” I inquired, “what did you say to Wilson that afternoon?”

“I told him the truth,” he said. “He was crazy enough to kill me if I hadn't told him who owned the car.”

I couldn't forgive him or like him but I saw that what he had done was, to him, entirely justified. They were careless people, Tom and Daisy.

Gatsby believed in the green light, the future that year by year recedes before us. We try to swim against the current, taken back ceaselessly into the past.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button

In 1860 it was proper to be born at home. Now, so I am told, children are usually born in fashionable hospitals. So young Mr. and Mrs. Roger Button were fifty years ahead of style when they decided that their first baby should be born in a hospital. Whether it played any role in the astonishing story I am about to tell we will never know.

I shall tell you what happened, and let you judge for yourself.

The Roger Buttons held a high position, both social and financial, in Baltimore. This was their first baby – Mr. Button was naturally nervous. He hoped it would be a boy[73 - He hoped it would be a boy – Он надеялся, это будет мальчик] so that he could be sent to Yale College in Connecticut, the institution to which Mr. Button himself had been once sent.

On that September morning he got up at six o'clock, dressed himself, and hurried to the hospital. When he was approximately a hundred yards from the Maryland Private Hospital for Ladies and Gentlemen he saw Doctor Keene, the family physician, descending the front steps, rubbing his hands together as all doctors do by the unwritten ethics of their profession.

Mr. Roger Button, the president of Roger Button amp; Co., Wholesale Hardware, began to run toward Doctor Keene. “Doctor Keene!” he called.

The doctor heard him, turned around, and stood waiting, with a curious expression on his harsh, medicinal face.

“What happened?” demanded Mr. Button, as he came up in a rush. “How is she? A boy? Who is it?” Doctor Keene seemed somewhat irritated.

“Is the child born?” begged Mr. Button.

Doctor Keene frowned. “Why, yes, I suppose so… ”

“Is my wife all right?”

“Yes.”

“Is it a boy or a girl?”

“I'll ask you to go and see for yourself!” Then he turned away muttering: “Do you imagine a case like this will help my professional reputation? One more would ruin me-ruin anybody.”

“What's the matter? Triplets?[74 - What's the matter? Triplets? – В чем дело? Тройня?]” “No, not triplets! You can go and see for yourself. And get another doctor. I'm through with you! I don't want to see you or any of your relatives ever again! Goodbye!”

Without another word he climbed into his carriage and drove away.

Mr. Button stood there trembling from head to foot[75 - trembling from head to foot – дрожа от головы до ног]. He had suddenly lost all desire to go into the Maryland Private Hospital for Ladies and Gentlemen-it was with the greatest difficulty that, a moment later, he forced himself to mount the steps and enter the front door.

A nurse was sitting behind a desk in the hall. Swallowing his shame, Mr. Button approached her.

“Good-morning. I–I am Mr. Button.”

A look of terror spread over the girl's face.

“I want to see my child,” said Mr. Button.

The nurse gave a little scream. “Oh-of course!” she cried hysterically. “Upstairs. Right upstairs. Go up!”

She pointed the direction, and Mr. Button began to mount to the second floor. In the upper hall he addressed another nurse who approached him. “I'm Mr. Button,” he managed to say. “I want to see my-”

“All right, Mr. Button,” she agreed in a hushed voice. “Very well! But the hospital will never have the ghost of its reputation after-”

“Hurry! I can't stand this!” “Come this way Mr. Button.”

He went after her. At the end of a long hall they reached a room. They entered. Ranged around the walls were half a dozen rolling cribs.

“Well,” gasped Mr. Button, “which is mine?”

“There!” said the nurse.

Mr. Button's eyes followed her pointing finger, and this is what he saw. Wrapped in a white blanket, in one of the cribs, there sat an old man apparently about seventy years old. His sparse hair was almost white[76 - his sparse hair was almost white – его редкие волосы были почти белыми], and he had a long smoke-coloured beard. He looked up at Mr. Button with a question in his eyes.

“Is this a hospital joke?

“It doesn't seem like a joke to us,” replied the nurse. “And that is most certainly your child.”

Mr. Button's closed his eyes, and then, opening them, looked again. There was no mistake-he was gazing at a man of seventy – a baby of seventy, a baby whose feet hung over the sides of the crib.

The old man suddenly spoke in a cracked voice. “Are you my father?” he demanded. “Because if you are,” went on the old man, “I wish you'd get me out of this place…”

“Who are you?”

“I can't tell you exactly who I am, because I've only been born a few hours-but my last name is certainly Button.”

“You lie!”

The old man turned wearily to the nurse. “Nice way to welcome a new-born child,” he complained in a weak voice. “Tell him he's wrong, why don't you?”

“You're wrong. Mr. Button,” said the nurse. “This is your child. We're going to ask you to take him home with you as soon as possible.” “Home?” repeated Mr. Button. “Yes, we can't have him here. We really can't, you know?”

Mr. Button sank down upon a chair near his son and put his face in his hands. “My heavens!” he murmured, in horror. “What will people say? What must I do?”

“You'll have to take him home,” insisted the nurse- ”immediately!”

“I can't. I can't,” he moaned. People would stop to speak to him, and what was he going to say? He would have to introduce this- this creature: “This is my son, born early this morning. ” And then the old man would gather his blanket around him and they would go on, past stores, the slave market-for a dark instant Mr. Button wished his son was black-past luxurious houses, past the home for the aged…

“Pull yourself together,” commanded the nurse.

“If you think I'm going to walk home in this blanket, you're entirely mistaken,” the old man announced suddenly.

“Babies always have blankets.” Mr. Button turned to the nurse. “What'll I do?”

“Go down town and buy your son some clothes.”

Mr. Button's son's voice followed him down into the hall:

“And a cane, father. I want to have a cane.”

“Good-morning,” Mr. Button said, nervously, to the clerk in the Chesapeake Dry Goods Company. “I want to buy some clothes for my child.”

“How old is your child, sir?”

“About six hours,” answered Mr. Button.

“Babies' supply department in the rear.”

“I'm not sure that's what I want. It's-he's an unusually large-size child. Exceptionally-ah-large. ”

“They have the largest child's sizes.”

“Where is the boys' department?” inquired Mr. Button. He felt that the clerk must scent his shameful secret.

“Right here.”

“Well-” He hesitated. If he could only find a very large boy's suit, he might cut off that long and awful beard[77 - he might cut off that long and awful beard – он мог бы отрезать ту длинную и ужасную бороду], dye the white hair brown, and hide the worst and retain something of his own self-respect-not to mention his position in Baltimore society.

But there were no suits to fit the new-born Button in the boys' department. He blamed the store, of course-in such cases it is the thing to blame the store.

“How old did you say that boy of yours was?” demanded the clerk curiously.

“He's-sixteen.”

“Oh, I beg your pardon. I thought you said six hours. You'll find the youths' department in the next aisle.”

Mr. Button turned miserably away. Then he stopped, brightened, and pointed his finger toward a dressed dummy in the window display. “There!” he exclaimed. “I'll take that suit, out there on the dummy.”

The clerk stared. “Why,” he protested, “that's not a child's suit. You could wear it yourself!”

“Wrap it up,” insisted his customer nervously. “That's what I want.”

The astonished clerk obeyed.

Back at the hospital Mr. Button entered the nursery and almost threw the package at his son: “Here's your clothes.”

The old man untied the package and viewed the contents.

“They look sort of funny to me,” he complained, “I don't want to be made a monkey of-”

“You've made a monkey of me! Put them on-or I'll-or I'll spank you.” He swallowed uneasily at the word, feeling nevertheless that it was the proper thing to say.

“All right, father”-this with a grotesque simulation of respect- ”you've lived longer; you know best. Just as you say.”

As before, the sound of the word “father” confused Mr. Button. “And hurry.”

“I'm hurrying, father.”

When his son was dressed Mr. Button regarded him with depression. The costume consisted of dotted socks, pink pants, and a belted blouse with a wide white collar. Over the collar waved the long beard.

The effect was not good.

“Wait!”

Mr. Button seized a pair of hospital shears and with three quick snaps cut a large section of the beard. But even without it his son was far from perfection. The remaining hair, the watery eyes, the ancient teeth seemed out of tone with the gayety of the costume. Mr. Button, however, held out his hand.

“Come along!” he said sternly.

His son took the hand trustingly. “What are you going to call me, dad?” he quavered as they walked from the nursery-”just 'baby' for a while? till you think of a better name?”

Mr. Button grunted. “I don't know,” he answered harshly. “I think we'll call you Methuselah.”

Even after the new-born Button had had his hair cut short and then dyed to an unnatural black, had had his face shaved so close that it glistened, and had been dressed in small-boy clothes made to order, it was impossible for Button to ignore the fact that his son was a poor excuse for a first family baby. Benjamin Button-for it was by this name they called him instead of by Methuselah- was five feet eight inches tall. His clothes did not conceal this, nor did the dyeing of his eyebrows disguise the fact that the eyes under were watery and tired. In fact, the baby-nurse left the house after one look at him in a state of considerable indignation.

But Mr. Button persisted that Benjamin was a baby, and a baby he should remain. At first, he declared that if Benjamin didn't like warm milk he could go without food altogether, but he finally allowed his son bread and butter, and even oatmeal by way of a compromise. One day he brought home a rattle and, giving it to Benjamin, insisted that he should “play with it.” The old man took it with a weary expression and jingled it obediently at intervals throughout the day.

There can be no doubt that the rattle bored him, and that he found other amusements when he was left alone. For instance, Mr. Button discovered one day that some cigars were missing. A few days later he found the room full of faint blue haze and Benjamin, with a guilty expression on his face[78 - with a guilty expression on his face – с виноватым выражением лица], trying to hide the butt.

This, of course, called for a severe spanking, but Mr. Button found that he could not do it.

Nevertheless, he persisted in his attitude. He brought home lead soldiers, he brought toy trains, he brought large pleasant animals made of cotton, and, to perfect the illusion, which he was creating-for himself at least-he passionately demanded of the clerk in the toy store whether “the paint would come of the pink duck if the baby put it in his mouth.” But Benjamin refused to be interested. He would steal down the back stairs and return to the nursery with a volume of the Encyclopedia Britannica[79 - He would steal down the back stairs and return to the nursery with a volume of the Encyclopedia Britannica – Он прокрадывался вниз по чёрной лестнице в детскую комнату с томиком энциклопедии «Британника»], which he would read through an afternoon, while his cotton cows were left neglected on the floor. Mr. Button could do nothing against such stubbornness.