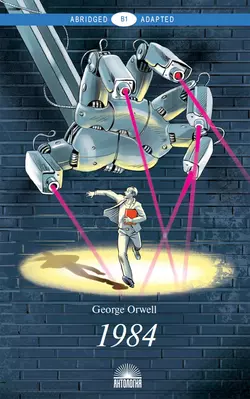

1984. Адаптированная книга для чтения на английском языке. Уровень B1

Джордж Оруэлл

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Литература 20 века

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 190.00 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: Антология

Дата публикации: 29.12.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Уинстон Смит, чиновник министерства правды, ведёт двойную жизнь. Внешне он добропорядочный гражданин и член партии, но внутренне готов поставить под сомнение и принятые политические идеалы, и разумность самого общественного устройства. Его роман с Джулией – попытка не в мыслях, а на деле совершить рывок за пределы, очерченные режимом.