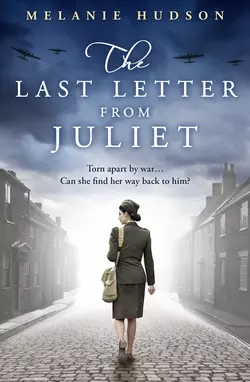

The Last Letter from Juliet

Melanie Hudson

The USA TODAY bestseller! For fans of Soraya M. Lane, Heather Morris, Fiona Valpy and Pam Jenoff. Inspired by the brave women of WWII, this is a moving and powerful novel of friendship, love and resilience. A story of love not a story of a war A daring WWII pilot who grew up among the clouds, Juliet Caron’s life was one of courage, adventure – and a love torn apart by war. Every nook of her Cornish cottage is alive with memories just waiting to be discovered. Katherine Henderson has escaped to Cornwall for Christmas, but she soon finds there is more to her holiday cottage than meets the eye. And on the eve of Juliet’s 100th birthday, Katherine is enlisted to make an old lady’s final Christmas wish come true… Me Before You meets The English Patient in this stunning romantic historical novel from award-winning author Melanie Hudson. Readers love The Last Letter from Juliet ‘OK…. I’ve finished the book. Holy ******…I had to keep taking breaks in the last 15% just so I didn’t break down in a flood of tears’ Zoe Hartgen ‘Read the first chapter and I. Was. HOOKED!’ Skye’s Mum ‘If you only read one book this year make it The Last Letter from Juliet’ Tracey Shults ‘I just couldn't put it down until finished’ Jeanette ‘Captures those stolen moments in dangerous and desperate times…beautiful, nostalgic and emotional’ Cheryl M-M ‘Jam packed full of emotion…I don't usually read historical fiction but I'm so glad I read this’ Jennie Scanlan ‘I can highly recommend this beautiful tale of love, sacrifice, friendship, courage and so much more’ Nessa Stimpson

The Last Letter from Juliet

MELANIE HUDSON

One More Chapter

a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Copyright © Melanie Hudson 2019

Cover images © Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com)

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Melanie Hudson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008319649

Ebook Edition © August 2019 ISBN: 9780008319632

Version: 2019-09-02

Table of Contents

Cover (#u4837d156-e47c-5fdd-b19a-6ba7b19492dc)

Title Page (#u6fdf0755-058b-5223-ab2e-a18ce4b50947)

Copyright (#u5bc6a3af-b2b2-5288-94b0-e73afd07083d)

Dedication (#u01822bc3-2780-50b5-87d4-2a090ac48c19)

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Dedicated to the inspirational and courageous women pilots who served with the Air Transport Auxiliary during the Second World War – the ultimate Attagirls!

Prologue (#u7e48d4b0-6036-5362-8380-0dc83e588d19)

Read Me

This is a note to yourself, Juliet.

At the time of writing you are ninety-two years old and worried that the bits and bobs of your story have begun to go astray. You must read this note carefully every day and work very hard to keep yourself and the memories alive, because once upon a time you told a man called Edward Nancarrow that you would, and it’s important to keep that promise, Juliet, even when there seems to be little point going on.

In the mahogany sideboard you will find all the things you will need to keep living your life alone. These things are: bank details; savings bonds; emergency contact numbers; basic information about you – your name, age and place of birth; money in a freezer bag; an emergency mobile phone. More importantly, there are also your most precious possessions scattered around the house. I’ve labelled them, to help you out.

Written on the back of this note is a copy of the poem Edward gave you in 1943. Make sure you can recite it (poetry is good for the brain). And finally, even if you forget everything else, remember that, in the end, Edward’s very simple words are the only things that have ever really mattered.

Now, make sure you’ve had something to eat and a glass of water – water helps with memory – and whatever happens in the future, whatever else you may forget, always remember … he’s waiting.

With an endless supply of love,

Juliet

Chapter 1 (#u7e48d4b0-6036-5362-8380-0dc83e588d19)

Katherine

A proposal

It was a bright Saturday lunchtime in early December. I’d just closed the lounge curtains and was about to binge-watch The Crown for the fourth time that year when a Christmas card bearing a Penzance postmark dropped through the letter box.

Uncle Gerald. Had to be.

The card, with an illustration of a distressed donkey carrying a (somewhat disappointed-looking) Virgin Mary being egged on by a couple of haggard angels, contained within it my usual Christmas catch-up letter. I wandered through to the kitchen and clicked the kettle on – it was a four-pager.

My Dear Katherine

Firstly, I hope this letter finds you well, or as well as to be expected given your distressing circumstances of living alone in Exeter with no family around you again this Christmas.

Cheers for that, Gerald

But more of your circumstances in a moment because (to quote the good bard) ‘something is rotten in the state of Denmark’ and I’m afraid this year’s letter will not burst forth with my usual festive cheer. There is at present a degree of what can only be described as civil unrest breaking out in Angels Cove and I am at my wits end trying to promote an atmosphere of peace and good will in time for Christmas. I’m hopeful you will be able to offer a degree of academic common sense to the issue.

Here’s the rub: the Parish Council (you may remember that I am the chair?) has been informed that the village boundaries are to be redrawn in January as part of a Cornwall County Council administrative shake-up. This simple action has lit the touch paper of a centuries-old argument amongst the residents that needs – finally – to be put to rest.

The argument in question is this: should our village be apostrophised or not? If ‘yes’, then should the apostrophe come before or after the ‘s’?

It is a Total Bloody Nightmare!

It really isn’t, Gerald.

At the moment, Angels Cove is written without an apostrophe, but most agree that there should be an apostrophe in there somewhere, yet where? The argument seems to rest on three questions:

1. Does the cove ‘belong’ to just one angel (the angel depicted in the church stained glass window, for example, as some people claim that they have seen him) or to a multitude of angels (i.e. the possessive of a singular or a plural noun).

2. Does the cove belong to the angels or do the angels belong to the cove? (The minority who wish to omit the apostrophe in its entirety ask this question.)

3. Does the word angel in Angels Cove actually refer, not to the winged messengers of the Devine, but to the notorious pirate, Jeremiah ‘Cut-throat’ Angel, who sailed from Penzance circa 1723 and whose ship, The Savage Angel, was scuppered in Mounts Bay (not apostrophised, you will note) when he returned from the West Indies at the tender age of twenty-nine?

As you can see, it’s a mess.

Fearing the onset of a migraine, I stopped reading and decided to sort out the recycling, which would take a while, given the number of empties. An hour later saw me continuing to give the rest of Gerald’s letter a stiff ignoring because I needed to get back to The Crown and plough my way through an ironing pile that saw its foundations laid in 1992. Just at the point where Prince Philip jaunts off solo on a raucous stag do to Australia (and thinking that I really ought to write a letter to The Queen to tell her how awesome she is), I turned the iron off (feeling a pang of guilt at leaving a complicated silk blouse alone in the basket) poured a glass of Merlot, popped a Tesco ‘extra deep’ mince pie in the microwave and returned to the letter …

I expect you will agree that this is a question of historical context, not a grammatical issue.

I do not.

As the ‘go to’ local historian (it must run in the family!) I attempted to offer my own hypothesis at the parish meeting last week, but can you believe it, I was barracked off the stage just two minutes into my delivery.

I can.

But all is not lost. This morning, while sitting on the loo wrecking my brains for inspiration, I stumbled across your book, From Nob End to Soggy Bottom, English Place Names and their Origins in my toilet TBR pile (I had forgotten you have such a dry wit, my dear) and I just knew that I had received Devine intervention from the good Lord himself, because although the villagers are not prepared to accept my opinion as being correct, I do believe they would accept the decision of a university professor, especially when I explain that you were sent to them by God.

So, I have a proposition for you.

Time for that mince pie.

In return for your help on the issue, please do allow me the pleasure of offering you a little holiday here in Angels Cove, as my very special present to you, this Christmas. I know you have balked at the idea of coming to stay with me in the past (don’t worry, I know I’m an eccentric old so-and-so with disgusting toenails)

True

but how do you fancy a beautiful sea view this Christmas?

Well, now that you mention it …

The cottage is called Angel View (just the one angel, note) and now belongs to a local man, Sam Lanyon (Royal Navy pilot – he’s away at sea, poor chap). He says you can stay as long as you like – I may have mentioned what happened to James as leverage.

Gerald!

The cottage sits just above the cove and has everything you could possible need for the perfect holiday (it’s also a bit of a 1940s time capsule because until very recently it belonged to an elderly lady – you’ll love it).

The thing is, before you say no, do remember that before she died, I did promise your mother that I would keep an eye on you …

It was only a matter of time.

… and your Christmas card seemed so forlorn …Actually, not forlorn, bland – it set me off worrying about you being alone again this Christmas, and I thought this would be the perfect opportunity for us to look out for each other, as I’m alone, too – George is on a mercy mission visiting his sister in Brighton this year. Angels Cove is simply beautiful at Christmas. The whole village pulls together (when they are not arguing) to illuminate the harbour with a festival of lights. It’s magical.

But?

But … with all the shenanigans going on this year, I’m not sure the villagers will be in the mood for celebration. Please do say you’ll come and answer our question for us, and in doing so, bring harmony to this beautiful little cove and save Christmas for all the little tourist children.

Surely this kind of thing is right up your Strasse?

My idea is that you could do a little bit of research then the locals could present you with their proposals for the placement of the apostrophe in a climatic final meeting. It will be just like a Christmas episode of the Apprentice – bring a suit! And meanwhile, I’ll have a whole programme of excitement planned for you – a week of wonderful things – and it includes gin.

Now you’re talking

Do write back or text or (God forbid) phone, straight away and say you’ll come, because by God, Katherine, you are barely forty-five years old, which is a mere blink of an eye. You have isolated yourself from all of your old friends and it is not an age where a person should be sitting alone with only their memories to comfort them. Basically, if anyone deserves a little comfort this Christmas, it’s you. I know you usually visit the grave on Christmas Day, but please, for the build-up week at least (which is the best part of Christmas after all) come to Cornwall and allow yourself to be swaddled by our angels for a while (they’re an impressive bunch).

I am happy to beg.

Yours, in desperation,

Gerald.

P.S. Did I mention the gin?

Sitting back in a kitchen chair I’d ruined by half-arsedly daubing it in chalk paint two weeks before, I glanced around the room and thought about Gerald’s offer. On the one hand, why on earth would I want to leave my home at Christmas? It was beautiful. But the energy had changed, and what was once the vibrant epicentre of Exeter’s academia, now hovered in a haze of hushed and silent mourning, like the house was afraid of upsetting me by raising its voice.

A miniature Christmas tree sat on the edge of the dresser looking uncomfortable and embarrassed. I’d decorated it with a selection of outsized wooden ornaments picked up during a day trip to IKEA in November. IKEA in Exeter was my weekly go-to store since James had gone. It was a haven for the lost and lonely. A person (me) can disappear up their own backsides for the whole morning in an unpronounceable maze of fake rooms, rugs, tab-top curtains, plastic plants and kitchen utensils (basically all the crap the Swedes don’t want) before whiling away a good couple of hours gorging themselves on a menu of meatballs and cinnamon swirls, and still have the weirdest selection of booze and confectionary Sweden has to offer (what on earth is Lordagsgodis, anyway?) to look forward to at checkout.

And we wonder why the Swedes are so happy!

But did I really want to spend the run-up to Christmas in IKEA this year? (Part of me actually did – it’s very Scandi-chic Christmassy). But to do it for a third year in a row, with no one to laugh out loud with when we try to pronounce the unpronounceable Swedish word for fold-up bed?

(That was a poor example because a futon is a futon in any language and I really did need to try to control my inner monologue which had gone into overdrive since James died – I was beginning to look excessively absent minded in public).

But did I want to spend Christmas in IKEA this year?

Not really, no.

But the problem (and Gerald knew this, too) was that if I left the house this Christmas, then it would mark the beginning of my letting go, of starting again, of saying that another life – a festive one – could exist beyond James. If I had a good time I might start to forget him, but if I stayed here and kept thinking of him, if I kept the memories alive, re-read the little notes he left me every morning, if I looked through photographs on Facebook, replayed scenes and conversations in my mind, then he would still be here, alive, in me. But if I go away, where would that lead? I knew exactly where it would lead – to the beginning of the end of James. To the beginning of not being able to remember his voice, his smell, his laugh – to the beginning of moving on.

And I wasn’t sure I was ready for that.

But still …

I knocked back the last of the Merlot while googling train times to Penzance and fished out the last card in a box of IKEA Christmas cards I’d abandoned to the dresser drawer the week before. It was the exact replica of the one I’d already sent him, a golden angel. I took it as a sign and began to scribble …

Dear, Uncle Gerald,

You are quite correct. This kind of thing is indeed ‘right up my Strasse’. Rest assure there will be no need to beg – I shall come!

I arrive in Penzance by the 18.30 train on the 17th and intend to stay (wait for it) until Boxing Day! By which time I am confident that, one way or another, I will have found a solution to your problem. DO NOT, however, feel that you have to entertain me all week. It’s very good of you but actually – and quite selfishly – this trip could be a blessing in disguise. I have been racking my brains for an idea for a new book – a history project to keep me going through the rest of the winter – and I have a feeling that hidden deep within the midst of Cornish myth and legend, I might find one.

Please thank Mr Lanyon for the offer of use of his cottage – I accept!

How are the cataracts, by the way? Are you able to drive? If so, I wonder if you could meet me at the station?

With oodles of love,

Your, Katherine

P.S. Wouldn’t it be funny if ‘The Cataracts’ were an old couple who lived in the village and I would say, ‘How are the Cataracts, by the way?’ And you would answer, ‘Oh, they’re fine. They’ve just tripped off to Tenerife for Christmas.’

P.P.S. Take heart in knowing that there is nothing simple about the apostrophe. It is punctuation’s version of the naughty Cornish pixie, and seems to wreak havoc wherever it goes. There is a village in America, for example, where the misplacing of the apostrophe led to full-scale civil unrest and ultimately, the cold-blooded murder of the local Sheriff. Let us hope for your sake that the situation at Angels Cove does not escalate into a similar scale of brouhaha!

P.P.P.S. Gin? I love you.

Chapter 2 (#u7e48d4b0-6036-5362-8380-0dc83e588d19)

Katherine

The last station stop

It turned out that the residents of Angels Cove were expecting not one, but two Katherines to arrive in Penzance on the evening of 17 December. My namesake Storm Katherine – a desperate attention seeker who was determined to make a dramatic entrance – would arrive late with the loud and gregarious roar of an axe-wielding Viking. Trees would crash onto roads, chicken hutches would be turned upside down, and the blight of every twenty first century garden – the netted trampoline – would disappear over hedgerows never to be seen again (it wasn’t all bad, then). I hoped Uncle Gerald wouldn’t see my concurrent arrival with Katherine as some kind of omen, but really, how could he not?

Stepping onto the train in Exeter, despite the forecast weather, I was excited. By Plymouth I was beginning to wonder if it had all been a dreadful mistake – the locals would want to chat, and the woman in the shop (there was always a chatty woman in a shop) would glance at my wedding ring and pry into my life with a stream of double negatives: ‘Will your husband not be joining you in the cottage for Christmas, then? No? Well, it’s nice to have some time away from them all, eh? And what about your children? Will they not be coming down? No children? Oh, dear. Well, never mind …’

That kind of thing.

By Truro, I’d decided to turn back, but Katherine’s advance party had already begun to rock the carriages, and by the time St Michael’s Mount appeared through the late afternoon darkness – a watered down image of her usual self, barely visible through the driving rain and sea fret – my excitement had vaporised completely. Gazing through the splattered carriage window, I was startled by the sight of my mother’s face staring back at me. Only it wasn’t my mother, it was my own aged reflection. When had that happened? Anxious fingers rushed to smooth the lines on my mother’s face, which could only be described as tired (dreadful word) and I realised that, just like St Michael’s Mount in the winter rain, I too was a watered-down image of my usual self, barely visible through a veil of grief I had worn ever since the morning James had gone.

I hadn’t needed an alarm call that morning. I’d been laying on my side for hours, tucked into the foetal position, the left side of my face resting on a tear-stained pillow, my eyes focused just above the bedside table, fixed on the clock.

I watched every movement of Mickey Mouse’s right hand as it made a full circle, resting, with a final little wave, on the twelve.

Mickey’s voice rang out—

‘It’s time, time, time, to wake up! It’s time, time, time to wake up!’

I’d never known if Mickey had been supposed to say the word ‘time’ three times, or if at some point over the past umpteen years he had developed a stutter, but I silenced him with a harsh thump on the head and lay staring at the damp patch on the ceiling we’d never gotten to the bottom of, just to the right of the light fitting.

I wanted to lay there and consider that phrase for a moment – ‘it’s time’. Two little words with such a big meaning.

It’s time, Katherine.

How many times had I heard those words?

My father had said them, standing in the kitchen doorway on my wedding day. He’d taken my hand with a wonderful smile and walked me to the car, a happy man. We were followed closely behind by my Aunt Helena, who was frothing my veil and laughing at Mum – who did not approve of the match – and who fussed along behind us, arguing about … I think it was art, but it might have been cheese. And now, twenty years later, the exact same words were used by Gerald, to direct me out of the house. To force me, my insides kicking and screaming for release, to slide into the long black car that waited in the yard – the car that would take us to James’ funeral, the sort of funeral that has the caption ‘But, dear God, why?’ hovering in the air the whole day.

I turned my back on Mickey and ran my arm across the base sheet on the other side of the bed. If only there was still some warmth there. An arm to curl into, a woolly chest to rest my head on. But the sheet was cold, and like everything else in my house in Exeter, retained the deep ingrained memory of centuries of damp.

But if I just lay there and let the day move on without me …

It’s time, time, time, to wake up!

Mickey again.

I stretched. Ridiculous thought. Mickey was right. The day wouldn’t move on, not if I didn’t wind the cogs and drop-kick the sun through the goal posts. I threw my legs out of bed, sat up, patted Mickey, apologised for hitting him on the head and I kissed him on the face. Poor thing. It wasn’t his fault James had been killed, even if he did insist in shouting at me every morning in his overly polite, American way.

It’s time, Katherine.

But that was the thing with travelling alone on a train, there was simply too much time to think. Trains were just one long rolling mass of melancholy, the carriages filled with random, interconnected thoughts. Travel alone on a train with no book to read and an over-thinker can spend an entire journey in the equivalent of that confused state between sleeping and waking.

And then the guard broke my reverie.

Ladies and gentlemen, we will shortly be arriving in Penzance. Penzance is the last station stop. Service terminates at Penzance. All alight at Penzance.

It was pretty obvious I needed to get off.

The train slowed to a final halt at the station and the last of the passengers began to stir. I grabbed my laptop case, put on my winter coat, hat and gloves and trundled to the end of the carriage in the hope that my suitcase would still be there. It was time to step out onto the platform, find Uncle Gerald, and head out into the storm.

Chapter 3 (#u7e48d4b0-6036-5362-8380-0dc83e588d19)

Katherine

A cottage by the sea

I stepped down onto the platform and stood still for a moment, my eyes searching through a river of passengers, before catching sight of Uncle Gerald, who was waving his multi-coloured umbrella like a lunatic and working his way upstream.

My heart melted. Uncle Gerald had been a steady presence in my life as a child, and although I had hardly seen him during my adult years, the bond that was formed during those childhood visits – nothing overly special, just a kind smile and couple of quid for sweets tucked into my sticky fingers – had never gone away. It was a bond that represented the safety and easiness of family. A bond that is usually lobbed into the back of the dresser drawer, stashed away, forgotten and allowed to loiter with the unused Christmas cards, nutcrackers and Sellotape, until the day came along when you actually needed it, and you opened the drawer with a rummage saying to yourself, ‘I just know I left it in there somewhere.’

Gerald rested his umbrella against my suitcase and put his arms around me.

I wasn’t expecting the sudden onset of emotion, but he represented a simpler time. A happy time. A time of singing together in the kitchen with Mum. The Carpenters.

‘Rainy Days and Mondays’.

I started to cry.

He patted.

‘Now then, none of that, none of that.’

‘Oh, don’t mind me, Uncle Gerald,’ I said, trying to smile while rifling through my handbag and coat pockets for a tissue. ‘Train stations and airport lounges always do this to me. I swear they’re the portals used by the tear fairies to tap directly into the tender places of the soul.’

Gerald handed me a folded blue handkerchief.

I opened the handkerchief and blew my nose.

He smiled. ‘Still over-dramatic then?’

I nodded.

‘That’s my girl!’

We both laughed and sniffed back the emotion before heading out into the wind and rain. We dashed to the car and he handed me the keys. ‘You wouldn’t mind driving, would you? Only I spent the afternoon in the Legion …’

***

The drive to Angels Cove took a little over half an hour. It was a fairly silent half hour because Uncle Gerald slept while I battled the car through the beginnings of the storm, luckily the sat nav remembered the way. The road narrowed as we headed down a tree-lined hill. I slowed the car to a halt and positioned the headlights to illuminate the village sign through the driving rain.

I nudged Uncle Gerald.

‘We’re here.’

He stirred and harrumphed at sight of the sign.

‘Perhaps now you can see why I asked for your help,’ he said.

I failed to stifle a laugh.

The sign had been repeatedly graffiti-ed. Firstly, someone had inserted an apostrophe with permanent marker between the ‘l’ and the ‘s’ of angels. Then, someone else had put a line through the apostrophe and scrawled a new apostrophe to the right of the ‘s’, which had been further crossed out. The crossings out continued across the sign until there was no room to write any more.

‘This all started at the beginning of November, when the letter from the council arrived. The average age in this village is seventy-four – seventy-four!– and they’re all behaving like children. I’ve got my hands full with it all, I can tell you. Especially on Wednesdays.’ He nodded ahead. ‘Drive on, straight down to the harbour.’

‘Wednesdays?’ I asked, putting the car into gear.

‘Skittles night at the Crab and Lobster.’

‘Ah.’

We carried on down the road, the wipers losing the battle with the rain and I tried to remember the layout of the village. I recalled Angels Cove as a pretty place consisting of one long narrow road that wound its way very slowly down to the sea. Pockets of cottages lined the road, which was about a mile long, with the pub in the middle, next to the primary school which was a classic Victorian school house with two entrances: BOYS was written in stone above one entrance and GIRLS written above the other.

The road narrowed yet further before opening out onto a small harbour. I stopped the car. The harbour was lit by a smattering of old-fashioned street lamps. Waves crashed over the harbour walls. The car shook. Although Katherine had not yet arrived with the might of her full force, the sea had already whipped herself up into an excitable frenzy.

Gerald pointed to the right.

‘You can’t make it out too clearly in the dark,’ he said, staring into the darkness. ‘But the cottage you’re staying in is up this little track by about a hundred yards … or so.’

I glanced up the track and put the car into gear.

‘You ready?’ he asked.

‘Ready? Ready for what?’

‘Oh, nothing. It’s just a bit of a bumpy track, that’s all.’ He tapped the Land Rover with an affectionate pat, as if he was praising an old Labrador. ‘No problem for this little lady, though. Been up that track a thousand times, haven’t you, old girl? Onwards and upwards!’

I set off in the general direction of a farm track. The car took on an angle of about forty-five degrees and began to slip and slide its way up the track. Waves crashed against the rocks directly to my left.

‘Shitty death, Gerald! What the f—?’

A couple of wheel spins later, to my absolute relief, a little white cottage appeared under a swinging security light. We pulled alongside and I switched off the engine, left the car in gear and went to open the driver door.

‘Don’t get out for a moment,’ Gerald said. ‘I’ll go in ahead and turn on the lights. It’ll give me time to shoo the mice away and make it nice and homely, that kind of thing.’

‘Mice?’

‘Only a few, and they’re very friendly.’

I wiped condensation from the window and tried to peer out into the storm. ‘OK, but don’t be too long,’ I said. ‘I feel like I’ve stepped through one of the seven circles of hell!’

***

The tour of the cottage was very short but very sweet. When Gerald mentioned that an elderly lady had left it as a 1940s time capsule, he wasn’t exaggerating. There were three bedrooms upstairs, which were pretty but functional, a downstairs bathroom, a good-sized kitchen and an achingly sweet lounge. Gerald lit the fire while talking.

‘I’ve stocked the fridge with enough food, milk and mince pies to take you through to the New Year.’ He glanced up. ‘Just in case.’

‘In case … what?’

He stood and brushed down his trousers. ‘This is Cornwall. Anything can happen.’

I took off my coat and lay it across the arm of a green velvet chaise longue, then crossed to the window to close the curtains. A photograph frame sat on the windowsill. The black and white image inside was of woman standing in front of a bi-plane, holding a flying helmet and goggles, smiling brightly, squinting slightly against the sun. There was a tag attached to the photo. I read it.

Summer 1938. Edward took this. Our first full day together. Two days in one – fantastic and tragic all at once. Why can we never have the one, without the other. Why can’t we have light without shade?

‘Juliet was a pilot,’ Gerald said by way of explanation, turning to face me briefly while attempting to draw the fire by holding a sheet of newspaper across the fireplace. ‘She flew for the Air Transport Auxiliary during the war. They used to deliver all the aircraft from the factories to the RAF, that kind of thing. Amazing woman.’

I nodded my understanding, still looking at the photograph.

‘Juliet handed the old place to Sam Lanyon last year, but he hasn’t got around to sorting through her belongings yet.’ Gerald rose to his feet. He screwed up the paper he’d used to draw the fire and threw it onto the flames.

I put the frame down, closed the curtains and looked around the room … photos, books, paintings, odds and ends of memorabilia. There was a 1920s sideboard, I opened a drawer. It was full of the same forgotten detritus of someone else’s life.

This was no holiday cottage, this was a home.

Gerald turned his back on the fire a final time. It was blazing.

‘Anyway, you’ve a good supply of coal and logs so just remember to keep feeding it, and don’t forget to put the guard up when you go to bed – this type of coal spits!’

He made a move towards the door. His hat and scarf were hanging on a peg in the little hallway. He grabbed them and began to wrap his scarf around his throat.

‘Are you sure it’s all right for me to stay here, Gerald?’ I was standing in the lounge doorway looking pensive. ‘Only it seems a bit … intrusive.’

‘Nonsense! It was Sam’s idea. He’s happy that it’s being aired.’

Gerald turned to leave and attempted to open the door. The force of the storm pushed against him. My unease at the prospect of staying alone in an unfamiliar cottage perched precariously on a cliff side, unsure of my bearings, during one of the worst storms in a decade, must have shown on my face. He closed the door for a moment and walked back into the lounge, talking to himself.

‘On nights like this, Juliet always put her faith in one thing, and it never let her down.’

I followed him. ‘What was that? God?’

He opened the sideboard door and peered inside.

‘Ha!’ He took out a bottle.

‘Whiskey?’

‘And there’s a torch in there, too.’ He put the whiskey back and walked into the kitchen. I heard him open and close a few drawers before reappearing in the lounge with half a dozen candles. He handed them to me.

‘Just in case the electricity goes out. And the matches are on the fireplace so you’re all set.’

The lounge window started to rattle.

He straightened his hat and headed to the door. ‘This cottage might seem rickety, but it’s the oldest and sturdiest house in the village. It’ll take a bit more than Katherine to see her off now!’

I picked up the car keys from the hall table and grabbed my coat from the lounge.

‘I’ll drive you home,’ I said.

‘No, no. I’ll walk back.’ He pulled his scarf tighter.

‘In this weather?’ I asked, only half concentrating, searching in my handbag for my phone. ‘Mercy, me! I have a signal!’

Gerald paused at the door.

‘Put the keys down, Katherine. I’ll be fine. Listen, why don’t you leave your coat on and come with me to see my friend, Fenella. Poor thing. I promised her I’d pop in on my way home. She’s had a bit of a bereavement and isn’t coping very well.’

‘Husband?’

‘Worse. Dog. Her cottage is on the harbour. We can nip in and pay our respects, quick cup of tea, then make our excuses and go back to mine … via the pub. You might as well meet the enemy straight off.’

I wanted to say, ‘Thank Christ for that. Yes please.’ But the curse of the twenty-first-century independent woman prevented me from throwing myself at his mercy. And I didn’t fancy the pub.

‘Don’t be silly,’ I said with a blasé shoulder shrug, taking my coat off one final time. ‘I’ll be absolutely fine.’ (Which is the exact phrase everyone uses when they are, in fact, sure that they will not ‘be absolutely fine’.)

He put his hand on the door handle.

‘And how are you sleeping these days?’

I shrugged.

‘Don’t tell me you’re still listening to Harry Potter audio books half the livelong night?’

I shrugged again.

Listening to Stephen Fry narrate Harry Potter was much better than tossing and turning all night. There was just something about the combination of the two – Fry and Potter – that made the world seem like a safe place again.

‘It relaxes me. And you must admit, you can’t beat a bit of Stephen Fry at bedtime.’

Gerald laughed.

‘I wouldn’t kick him out of bed, I suppose – but don’t tell George, you know how jealous he gets. Well, if you’re sure, I’ll be off. Just phone me if you need reassurance. Oh, and there’s WiFi here.’

Result.

‘The code is …’ Gerald paused and delved into his coat pocket. He took out a scrap of paper. ‘… “tigermoth”, one word, all lowercase. And try not to worry. I wouldn’t leave you here if I thought it wasn’t safe.’

Gerald kissed me on the cheek and stepped out into the wind.

‘I’ll pop up tomorrow morning once the storm’s gone through,’ he shouted. ‘I’ve got a fabulous programme of events all worked out, people to meet, things to do! And lock the door behind me straight away. It’ll bang all night if you don’t.’

‘I will,’ I shouted back, down the lane. ‘And, thank you!’

With the door locked and bolted, I walked into the lounge, sat on the sofa and stared into the fire, unconsciously spinning my wedding ring around my finger. The lights began to flicker, and in the kitchen, another window rattled. I grabbed my laptop from the hallway, logged onto the WiFi and – for at least five seconds – thought about doing a little apostrophe research (or any research that might lead me in the direction of a new project and take my mind off the storm). I closed the laptop lid.

Tomorrow. I’d do the research tomorrow.

I grabbed the remote control, flashed the TV and Freeview box into life and pressed the up button on the volume. The closing scenes of a Miss Marple rerun sounded-out most of the noise of the storm. Now all I needed to do was make a cup of tea, rustle up dinner and settle down to a spot of Grand Designs (the harangued couples who mortgaged themselves to the hilt and lived in a leaky caravan during the worst winter on record with three screaming kids and another on the way while trying to live off the land and source genuine terracotta tiles in junk shops for a bathroom that wouldn’t be built for another five years … they were my favourites).

With the closing credits of Miss Marple rolling down the screen, I walked through to the kitchen to make dinner. It was the real deal on the quintessential cottage front – not a fitted cupboard in sight – and very pretty, with French doors at the rear. A circular pine table with two chairs sat at the opposite end of the kitchen to the French doors, underneath a window. A golden envelope addressed to Katherine Henderson, C/O Angel View, sat on the table. I opened the envelope and took out the Christmas card.

Another angel, they were everywhere this year.

Dear Katherine

Just a quick note to welcome you to Angel View and explain about the house, which until recently belonged to a very special lady called Juliet Caron – my amazing Grandmother. You will find that her personality is still very much alive within the cottage walls. I’m sorry I wasn’t able to decorate the cottage for Christmas before you arrived, but you’ll find lots of decorations in the loft if you want to make the old place feel a bit more Christmassy.

Most importantly, please make yourself at home and have a wonderful time.

Yours,

Sam Lanyon

P.S. … you may find that a particularly vigilant Elf has already pitched up and positioned himself in the house somewhere. He always kept a beady eye on Juliet at this time of year. Give him a tot of whiskey and he’ll be your friend for life!

Smiling, I rested the card against a green coloured glass vase filled with yellow roses and took a cursory glance around the kitchen. There he was – sitting on a shelf, looking directly at me with his legs crossed and auspicious expression on his face.

I crossed the room to take a good look at him.

‘Hello, Mr Elf,’ I said, cheerily. ‘You needn’t worry about me. As Eliza Doolittle once said, I’m a good girl, I am … unfortunately!’

A few half-burned candles were scattered around the worktop and also on the windowsill. I took the matches from the lounge and lit them. There was a notepad and pen on the worktop, as if waiting for the occupier to make a list, and a very pretty russet red shawl was draped over the back of one of the chairs. I picked up the shawl and ran it through my fingers – it smelt of lavender and contentment. A luggage-style label had been sewn onto the shawl at one end. It read—

This was Lottie’s shawl – her comfort blanket. You wrapped Mabel in it on the day Lottie died.

Feeling a sudden chill, I took the liberty of wrapping the shawl around my shoulders and began to put together the makings of dinner – cheese on toast with a bit of tomato and Worcester sauce would do. I took an unsliced loaf out of the breadbin and opened the drawer of a retro cream dresser looking for cutlery. Sitting on top of the cutlery divider was a hard-backed small booklet with a large label attached to it. Another label? I took out the booklet and ran a finger over the indented words, First Officer Juliet Caron, Flying Logbook.

I turned the label over. With very neat handwriting, it read:

This is your flying logbook, Juliet. It is the most significant document of your life. Look at it often (whenever you use cutlery will do) and remember the times when you were happy (Spitfires), the times when you were stressed out (Fairey Battle – awful machine), the times when you had no idea how you survived to fly another day (like that trip in the Hurricane when the barrage balloons went up just as you were leaving Hamble) and that terrible day you tried to get to Cornwall with Anna – the one entry you wish you could delete. Other than the compass, this is your most treasured possession.

My rumbling tummy brought me back to the moment. I filled the kettle, stepped over to the fridge and noticed a laminated note stuck to the door with ‘Read Me’ written on the top. I read it, expecting it to be instructions from Sam, or Gerald.

It wasn’t.

While the kettle was boiling, I read a letter which began:

This is a letter to yourself, Juliet …

So that was what all the labels were for … Juliet had been frightened of losing her memory. I took the letter off the fridge and turned it over.

Where Angels Sing, by Edward Nancarrow

When from this empty world I fall

And the light within me fades

I’ll think, my love, of a sweeter time

When life was light, not shade

With bluebirds from this world I’ll fly

And to a cove I’ll go

To wait for you where angels sing

And when it’s time, you’ll know

To meet me on the far side where

We once led Mermaid home

And finally, my love and I

Will be, as one, alone

And at that moment, after pouring water from Juliet’s kettle into Juliet’s cup, sitting in Juliet’s house and wearing Juliet’s shawl, I felt an overwhelming sensation of being swaddled, that Juliet and I were somehow linked. Gerald would blame my overactive imagination, of course, but I really did feel that I was supposed to come to Angels Cove this Christmas.

With my dinner quickly made and eaten, I set up camp in the lounge and, trying to ignore the other Katherine who was hammering at the door to get in, I decided it was time for Kevin McCloud (such a lovely man) to transport me into his TV world of Grand Designs, into other people’s lives – happier, family lives – where dreams really do come true (and maybe a tot or two of that whiskey wouldn’t go amiss either).

Glancing into the sideboard I was mesmerised – it was an Aladdin’s Cave of memorabilia, of yet more labels. Next to the whiskey was a wad of faded A4 paper held together by green string. The top sheet had the typewritten words,

Attagirls!

The war memoirs of Juliet Caron

Lest she forgets

I untied the string and peeled back the top sheet to reveal a letter.

1 June 1996

My dear Sam

How is life at sea treating you? I know I say it too much for your liking, but I’ll say it again – I’m so very proud of you (and a little jealous of all that fabulous flying, too!).

Anyhow, I’m sure you must be busy so I’ll get to the point because I’m worried, Sam. Worried that my older memories are starting to fade and that one day soon they may leave me completely. Sitting here in my little cottage, able to do less and less each day, watching the tide ebb and flow, I have felt suddenly compelled to remember and record what happened in my life during the war. I read somewhere that if you wish to tell a story of war, do not tell the basic facts of the battle, but tell instead of the child’s bonnet removed from the rubble of a Southampton street, or the smell of twisted metal from a burnt Hurricane crashed by a friend, or the lingering smell of a man, robbed of his prime by typhus, as he lays in a strange bed in a foreign land, dying. I’m not sure I shall be able to do this, but even so, I have begun to write everything down. My friend Gerald is helping me. I aim to write one instalment per month – the first one is written already and attached – and send you copies as I write them. It’s an heirloom, I suppose, for you and your children (or if nothing else to give you something sensational to read during those long nights at sea!).

As you read each instalment, remember that my words will be as accurate as my aging mind allows them to be. Certain days stand out more than the rest. Just lately, I find that I can remember 1943 like it was yesterday, and yet events from yesterday elude me as if set in 1943. But what is truth of any situation anyway? I really do feel that life is made up of a constant stream of living, punctuated only by that otherworld of sleep. The fact that we choose to put a time and date to everything is merely a paper exercise. I used to think that once a moment is gone, it is gone forever, resigned only to memory. But now – now that I can no longer take my memory for granted – I realise that this is not the case. Love, for example, once thought lost, can be captured forever, just so long as someone out there strives to keep the memory of that love alive.

And so here is the first in a series of my memories that consist only of certain vivid days. They are memories of a time when suddenly, for a woman, absolutely anything (both the good and the desperately bad) became possible.

Anyway – enough of my ramblings!

Drum roll, please …

‘Ladieeeees and gentlemen! Lift your eyes to the heavens and prepare to be amazed, to be wowed and bedazzled! Here she is … the fearless! The death-defying! The one and only – Juliet Caron!’

I rested the letter on my knee just as a crash outside coincided with the sudden outage of the lights and the television turned to black. The glow from the fire provided sufficient ambient light for me to reach into the sideboard and find the torch, but the battery must have been an old one because the torchlight was weak and to my disappointment, within a few seconds, petered out.

Determined to take on some of the inner strength of the remarkable woman who had written a note to herself at ninety-two years old to never give in, I surrounded myself with candles, stoked the fire and wrapped the russet shawl tighter around my shoulders. And despite knowing that I shouldn’t waste my phone battery on a little light reading, not tonight of all nights, I got myself cosy on the sofa, abandoned Harry Potter, enabled the torch on my phone and began to read.

Chapter 4 (#u7e48d4b0-6036-5362-8380-0dc83e588d19)

Juliet

1938

A Cornish Christmas

Newspaper Cutting: The Bicester Herald

FREE AEROPLANE FLIGHTS FOR TEN LUCKY READERS!

AIR DISPLAY EXTRAVAGANZA!

Reach for the stars with the one and only

LOUIS CARON FLYING CIRCUS!

Old Bradley’s Field

1

July (for one day only)

2.30 p.m. till dusk

Star Attraction

JULIET CARON

The daredevil darling of the skies and Britain’s finest child star &aerobatic pilot

Admission 1s. Children 6d.

My name is Juliet Caron and although it would be difficult for anyone to believe if they saw me now (age has a dreadful habit of throwing a dust sheet over the vibrancy of youth) I was once the celebrated flying ace and undisputed star of the one and only Louis Caron Flying Circus.

I do not say this to boast, well, maybe a little bit, but to explain how it was that my father taught me to fly almost as quickly as I learned to walk and how, on a bright winter’s afternoon just a few days before Christmas 1938, I found myself soaring one thousand feet above Cornwall in my bright yellow Tiger Moth, looking for angels. It was a simple time in my life. Simple in the way that only those brief years before we know the agony of love, can be. My lungs were exploding with the exuberance of youth and my face was tight against the freezing air. In sum, I was living a life that was just about as alive as it is possible for a human life to be.

But first I must tell you a little of the flying circus, because my childhood was the circus, it moulded those formative days when the personality begins to take shape. My circus years were wonderful years. They were the years I had my parents with me, parents who were – and always would be – my inspiration, my warriors, my rocks.

When I was fourteen a journalist asked me to describe what being part of a flying circus was like. My father stood by me while I thought of my answer. We were in Sam Bryant’s field near Bicester, Oxfordshire, our aircraft lined up side by side, waiting to display. The crowd was arriving and the buzz of expectation bounced in the air while a cornflower blue sky kissed by a soft, silky breeze heralded the chance of a wonderful display. Tongue-tied, I looked at my father, who knelt next to me, and stalled as to what to say. He said to close my eyes and imagine how it feels to fly – to say the first thing that came into my head. The answer I gave was the answer of a child, but I would have given exactly the same answer as an adult, because the euphoria of flying – that feeling of absolute freedom – never left me.

‘Imagine heaven on earth,’ I said, ‘or rather, heaven in the skies. Imagine you’re in a dream and in that dream you somehow shrink down to the size of a doll and strap yourself onto the back of a golden eagle. You cling on to his feathers while he swoops and dives and soars and loops. And then you realise that if you’re very gentle with him and pull lightly on a feather here and there, you can control him a little, and then you’re flying too, every bit and just as naturally as the bird, and every element hits you with a freshness that can’t be matched, every sense is bright and alive. And then the bird dives towards the earth, barely missing the ground, before turning on a hairpin and soaring away. You are not in control at that moment, I think, but you are not in danger either, not so long as he – you – pull up in time. But that’s the best thrill of all – the not completely knowing if you’ll pull out of the dive in time. You simply have to trust, have faith in your judgement and let go of all fear. But you do pull out, because instinct and survival and an understanding of how to fly and how to move through the air kicks in, and you climb higher and take a breath, but not for long, because then you jump off the bird and into your father’s arms and cling on while he spins you around and around and the whole world is no more than a line of spinning colour. And your hair and skirt and legs are flung out at ninety degrees and you know that if he lets you go, you’ll fly out of the dream and into oblivion. But again, you have to trust, to become a part of the motion, to know that he will never let you go, you’re safe.’ I glanced up at Father and smiled. ‘I suppose I just feel full of joy and completely free. That’s all, really.’

An hour after the interview, my Father and mother died. Father was flying and mother was his wing-walker, her long hair and scarf trailing behind her. She was waving at me just before she died. I was standing next to my Tiger Moth, my performance coming later. I waved back at her, proud and happy. But then Pa lost control somehow and didn’t pull up in time, and I was no longer waving but screaming and running, not believing such a thing could possibly be true, already aching for a feeling I would only ever know once again – that feeling of unquestioned security and unconditional love.

But back to Cornwall and Christmas 1938.

The little Tiger Moth, its Gypsy engine humming a familiar tune, clung to the Cornish coast as I peered over the side, my face tight against the freezing slap of the winter air. I was looking for my final navigational landmark – three small craggy mounts known locally as the Angels – that sat a few hundred yards out to sea next to a little fishing village called Angels Cove. All I had to do was to find the mounts, then a mile or so further along the coast I would find my destination, a rather grand-looking house called Lanyon and in turn, my landing strip.

I took a moment to glance down again and cross-reference the river arteries on a map before turning at Lizard Point to follow the coast northbound. If my calculations were correct, the mounts would be on the nose in two minutes exactly. They were, and looked exactly like stepping stones plopped into the sea for the convenience of a Cornish giant. After circling around the Angels a couple of times to take a closer look, I headed inland and descended, slowing to almost stalling speed looking for Lanyon – a large, red-brick manor house, with four gables and twelve chimneys. And suddenly it was there, sitting above a little patch of sea haze, in majestic reverence, on the cliffs above the cove.

The landing strip was nothing more than the lawned area in front of the house, but drat it all, a downdraft from the cliffs pulled at the aircraft’s little wooden frame as I approached, dragging me far too close to a line of very tall cedar trees as I turned finals. I powered on, overshot the approach and climbed away, waving cheerily at a couple of gardeners just a few feet below, who were leaning on rakes, open-mouthed, watching. The performer in me not dead but simply sleeping, couldn’t resist throwing the Moth into a tidy little barrel roll, before disappearing off over the horizon, to find pastures new and within these pastures, hopefully, a safe place to land. Within a minute I had found a stretch of level grass on the cliffs, directly above Angels Cove. There was a large barn in the corner of the field, too, which, if empty, could act very nicely as a store for the Moth. I turned into the wind, began my final decent and moments later, to my great relief, landed safely.

With the propeller slowed to a stop, I tore off my goggles and wool-lined leather helmet, unclipped the harness and jumped out to gather my bearings. A minute later found me jumping back into the wing’s stepping plate because a dozen or so cows approached at speed with a collective air of indignant and inquisitive over-confidence.

From my position of height, I attempted to shoo.

Shooing proved fruitless.

Help appeared almost immediately in the form of two men and a dog. They were walking towards me from the direction of the barn. The first man was wearing a long coat, his collar turned up against the wind. On closer inspection he was frowning. Definitely frowning. The second – the stockman by the looks of things – was shaking a stick in my direction. Even the dog seemed to walk with an air of peeved annoyance.

The men slapped fat sashaying backsides as they walked towards me, saying things like, ‘Get on with you,’ and ‘Away, away.’ On seeing the younger man’s face more clearly, and suffering from sudden and complete amnesia regarding the existence of Charles, my fiancé, who was waiting for me at Lanyon, I attempted to tidy my hair, which was beyond redemption. I quickly glanced down at my clothes. I was wearing a flying jacket (my father’s, far too big for me and ripped on the right sleeve) and, over thermal long-johns, men’s overalls, covered in oil, rolled up at the ankle and pulled in at the waist with a wide belt. The icing on the cake was my footwear – muddy, fur-lined flying boots.

Taking a cloth from my pocket, I gave my face and hands a quick wipe. The two men were only a few steps away now. The younger one paused out of earshot to speak to the other man, who snorted in my direction before turning tail and heading towards the barn, using a long stick to usher the cows with him.

The man approached. His expression did not soften.

‘Well, hello, there,’ I said, cheerily.

He stood there for a moment, not speaking. A kind of apoplexy seemed to have set in (this often happened to a man who found himself unexpectedly face to face with a female pilot. It was the shock, you see). I decided to wade straight in with an apology. Farmers could be ever so touchy about aircraft landing in their fields without invitation. It was best to take the wind out of their sails with a smile.

‘I’m so sorry for the …’ I glanced towards the cows. Their backsides lumbered from side to side as they began to disperse. Tails flicked with annoyance ‘… disturbance. I meant to land in front of a large house, up the way there.’ I paused to look in the direction of the house. ‘It’s the one with the four gables and twelve chimneys … or is it four chimneys and twelve gables, I can never remember …? Do you know it?’

‘Lanyon?

‘Yes.’

‘Of course. But look here …’

My bright smile and humble apology fell on blind eyes and deaf ears. He began to chide – really chide – something about the utter irresponsibility of landing an aircraft in a field full of cattle … could have killed myself, etc. etc. He went on for quite some time about all kinds of things that might possibly have happened had luck not been on my side, but I really couldn’t concentrate because he was just so damn gorgeous and to top it had a slight American twang in his accent, too, and I had a very definite soft spot for a soft American accent on a man, probably because of all the movies we watched in those days.

I was just trying to work out what an American was doing working on a Cornish farm when he stopped preaching and returned to his preoccupation of staring at me. I realised he was waiting for me to respond to his disciplinary lecture, but not knowing quite how to respond, and rather than answer and annoy him further, I simply kept quiet and ran my fingers through my tangled mop of thick hair, just as the cold wind nipped at my face and turned my nose into a dripping tap. I wiped my nose with the cloth and we stood in a kind of ‘what now?’ silence while the Tiger Moth rocked on its wheels in the wind. He was obviously going to wait it out until I spoke. There was nothing left to do but to shrug and apologise again.

‘You’re absolutely right, of course,’ I said, adding a suitably big enough sigh. ‘Landing on a cliff in a field full of cows was not my finest spot of airwomanship, but to be fair, I didn’t see the cows and if you think about it, nothing bad actually did happen so I wonder, could we start again because, you know, ’tis done now, and what else can I do but say to that I’m so very – very – sorry.’

I tried my best to look remorseful.

He took a deep breath. His eyes were cold, steady.

‘I’d say that was a perfunctory apology.’

‘Perfunctory?’ I repeated.

‘Yes, perfunctory.’

He had more.

‘You think that because you’re a beautiful woman you can do whatever you want – gallivant around, hither and thither …’

Hither and thither? An American saying ‘hither and thither’?

I let him rant on again, completely unaware of what he was saying because frankly, he could say what the hell else he liked. No person on the planet (other than my parents) had called me beautiful before – even my fiancé had never called me beautiful.

‘Listen,’ I interrupted, eventually, ‘we seem to have got off on the wrong foot.’ I turned towards the cows again who were quite a way away now. ‘You’re absolutely right in everything you say. Perhaps we could shake hands on the matter and start again – shall we?’

I removed my right flying glove and held out my hand. He hesitated, as if some kind of trickery might be involved, but then my hand was in his, being held for what seemed to be a couple of seconds ever so slightly longer than necessary, despite the chiding.

He pulled away.

Silence again, except for the whistle of the wind across the cliff tops. The void needed to be filled.

‘And hey! As a thank you, how about I take you flying this week sometime?’

He tilted his head to one side. He was suppressing a smile, I was sure of it.

‘A thank you? A thank you for what?’

I glanced towards the barn.

‘Well – and I know it’s ever so cheeky – but for allowing me to store my aircraft in your barn for the week.’

He turned to look at the barn.

‘The thing is, I can’t leave the old girl out here all week. I’m a guest at Lanyon for Christmas, you see, and I’m sure they would vouch for my good character – although it seems you’ve made a decision about that already.’ I added, with a side-eye towards the dog, who looked unconvinced. ‘I’ll pay for the inconvenience, obviously, although you’ll probably simply accuse me of throwing money at the problem …’

He braced his back against the breeze. His expression was unreadable. Was that a smile, though?

‘Which one?’ he asked, finally.

‘Which one, what?’

‘Which Lanyon are you the guest of?’

‘Er …’

Now, I know I should have said, Charles, I’m his fiancée, but the angel sitting on my right shoulder went into all-out battle with the devil on my left and the devil won. I should also have added, ‘We’re getting married this week, on Christmas Eve in fact. Do you know him?’

But I didn’t. Instead I went with …

‘Oh, I went to school with the daughter of the house. Lottie Lanyon?’

He nodded a kind of understanding.

‘The cove was the most perfect navigational landmark, what with the mounts …’ I touched my hair far too often as I spoke. ‘But the lawn at Lanyon – where I was expecting to land – was not at all suitable – trees, you see – and then there was the most terrible downdraft from the cliffs. So, it was either put down in your field or bust the old girl up in a hedge. And as I said. I didn’t notice the cows. I’m so very sorry.’

Just how many times would I need to apologise to the man?

He sniffed, considering. I wasn’t sure quite just what he was considering, exactly. We glanced in unison at the cows again, who were slowly being funnelled through a gateway into the next field.

‘Are they very upset by it all, do you think?’ I asked. ‘Is that what the problem is? Should I go and, I don’t know, pat them all and apologise or something.’

Finally, he laughed. Even his dog glanced up at him with an amused eye roll.

‘I shouldn’t think an apology is necessary.’ He patted the aircraft, visibly relaxing. ‘They would have eyed this machine of yours as an excellent scratching post. They’re most likely annoyed to have missed a good look-see. Cows are inquisitive beasts. Don’t you think so, Miss?’

‘Caron,’ I answered brightly. ‘Miss Caron.’

What the hell was I doing? The man was a rude and sanctimonious ass. And, oh, yes – I was getting married.

‘Caron,’ he repeated, softly. ‘Is that a French name?’

‘Yes. My mother was the Caron. She was French. She insisted that Papa took her name. Papa was English through and through, though.’

‘How very …’

‘Modern?’ I offered.

‘I was going to say, “good of him”. They sound like a progressive family.’

Gaining just a little of the sense I was born with, and not wishing to talk about my parents, I took control.

‘But back to the barn,’ I said. ‘I know it’s such an imposition, Mr …’ I paused and waited for him to finish my sentence.

‘Nancarrow – Edward, Nancarrow.’

A Cornish name? But the American accent? Intriguing.

‘… Nancarrow, but as I said, do you think I could put my aircraft in your barn overnight. Only, the wind’s getting up and an aircraft like this isn’t very sturdy – it’s not much more than a few planks of wood nailed together, really – just a wing and a prayer, as my mother always said. And the thing is, I’m here for the whole of Christmas week – I think I told you that already – so I’ll need somewhere safe to stow her and I’d be ever so grateful if I could pop her into the barn, really I would.’

Edward tightened his scarf against the wind. ‘I should think that would be all right,’ he said, turning towards the stockman who waited by the far gate, looking back at us, probably still scowling. ‘But you’ll have to check with Jessops over there, first.’

He glanced across to the stockman. I took the opportunity to examine Edward’s face. The afternoon light highlighted golden flecks in his hair and the wind reddened his cheeks to a marvellous healthy glow.

He noticed you looking at him. He bloody-well noticed.

Edward returned his attention to the aircraft and stroked it this time, rather than patted.

‘But you shouldn’t call this lovely old Tiger Moth a few planks of wood, she’s beautiful. Absolutely beautiful.’

I adopted an expression of surprised amusement. ‘You actually know what type of aircraft it is?’

‘Ah, you think I don’t know one end of a magneto switch from another?’

Handsome and a flyer …

‘But seriously. You fly too?’ I pressed.

‘Now and again, a bit of joy riding. Nothing much more than that. And there’s the feed to consider …’ The change of tack confused me.

‘Feed?’

‘For the cows. Jessops may have to check with your Mr Lanyon first, before you put the aircraft away. This is Lanyon land and they’re his cows, after all. But as you’re their guest … I’m sure it will be fine.’

I wanted to say, ‘Don’t be silly, he’s not my Mr Lanyon,’ but then remembered that, of course, Charles was exactly that – my Mr Lanyon.

‘His cows? I thought they were your cows.’

He shook his head. ‘My cows!? No. I was walking my dog along the cliffs and I’d stopped to talk to Jessops when we saw your aircraft coming in.’

He glanced around, realising the dog had wandered off while we were talking.

‘Speaking of your dog, where is she?’

He whistled. Moments later the red-and-white Collie dog appeared from behind a Cornish hedge. She had one ear up, one ear down. Edward ruffled her head. His face was a picture of fatherly pride. I knelt down to fuss the dog who jumped backwards and had absolutely no interest in me, just as Edward decided to turn tail towards the far field in the direction of Jessops.

‘Wait here a moment, will you …?’ he shouted back, already dashing across the field.

The dog ran after him. I shivered. The breeze really was frightfully cold, and I hadn’t been able to warm up since the flight. I danced on the spot and waited for Edward to come back.

‘All sorted,’ he said, slightly out of breath having run across the field with the dog, whose name I would later learn was ‘Amber’, barking at his heels. ‘You can leave it in the barn for the week. No need to check with the big house. But perhaps you could arrange for some kind of gift to be sent to Jessops – some beer or cider perhaps, as a thank you. It’s quite an inconvenience for him.’

You’d have thought the man was my father!

‘Of course. I’m not a completely inconsiderate oaf, you know!’

Edward’s face fell.

‘Fine. If you’re all sorted, I’ll be on my way.’ And with a curt nod of the head, he began to walk away.

‘Wait!’ I said, running in front of him, forcing him to stop. ‘Sorry, sorry to impose – again – but if I show you how, could you turn the propeller for me to get her started?’ I spun my arm in a clockwise direction. ‘I would do it myself, but it’s much easier with two, and it would be better to taxi her across to the barn under power than to push her all the way.’ I glanced down at Amber. ‘You might want to tether the dog first, of course.’

Edward took a deep breath. For a moment I think he considered walking away – it seemed he also had a devil and angel on each shoulder, too!

The angel won.

He changed his mind.

‘I know how to spin a propeller.’

He strode back to the Tiger Moth ahead of me.

But then, from nowhere, his face softened and his eyes danced when he noticed the paint work on the side of the aircraft.

‘The Incredible Flying Fox?’ He turned to me, smiling. ‘That’s never you?’

I shrugged. ‘Once upon a time, yes.’

‘You’ve got to be kidding? But you’re too young, surely.’

He was genuinely shocked. My heckles started to twitch.

‘Kidding? Not at all. I’d take you up, take you through my routine, but I doubt you’ve got the stomach for it. Few do.’

My ‘I dare you’ expression set off a further glimmer of amusement in his eyes. He took the bait and ran with it.

‘Oh, I’ve got the stomach for it, but only if you truly know what you’re doing. I’ve no wish to die young.’

‘Ah, I see.’ I turned away and knelt to duck under the aircraft to remove the chocks while talking. ‘You’re one of those men.’ He followed me.

‘Those, men?’

‘Yes, the type who can’t believe – or cope with – a woman doing anything outside of the ordinary drudge they’re usually stuck with. I grew up with a thoroughly modern and fair father – progressive, as you said – and I’m simply not used to being around men like you.’ I glanced up at him.

He raised his brows into a question mark.

‘Dinosaurs,’ I said.

I expected a smirk. But he smiled. A soft smile. He stepped towards me.

‘I was joking. Truly. I’m not at all one of those men.’

It was my turn to take a deep breath. I’d been overly nice to this man long for enough. I put on my helmet, goggles and gloves with sharp snatches.

‘So, will you help? Because I can manage on my own if not.’

‘I’ll help,’ he said.

‘And you’ve started a propeller before, you say?’

He nodded. ‘A few times, yes.’

‘I’ll jump in and leave you to it, then.’ I paused. ‘But only you’re sure you know what you’re doing?’

‘Of course, I do.’

‘Good.’

‘Good.’

I climbed into the back seat and prepared the Moth for taxi. He turned the propeller and then …

‘Contact?’

‘Contact!’

And off the little Tiger Moth went.

Chapter 5 (#u7e48d4b0-6036-5362-8380-0dc83e588d19)

Juliet

Lanyon

I grabbed my bag and ran away from the field, sharpish, arriving at Lanyon half an hour later to find a concerned Charles on the drive pacing outside the grand front door.

‘Oh, hello, darling,’ I said, blundering my way into the hallway ahead of him. ‘Sorry I’m late. I had to put down in a field and ended up having a bit of commotion with some cows, but it’s all sorted now.’ I pecked him on the cheek. ‘Where’s Lottie,’ I asked, taking off my flying helmet while glancing in the hall mirror. God! Had I really looked like that in front of Edward? I quickly tidied my hair and tried to rub a smudge of oil away with the back of my hand. ‘Only I’m desperate to catch up.’

Charles didn’t answer but took my hands.

‘But … Darling,’ he paused. ‘Before you see Lottie, I really do think we need to talk about, you know, the arrangement … only, Pa wants to iron a few things out. Details, you know.’

I shook him off with a peck on the lips.

‘Yes, I suppose we do. But not now though.’ I smiled my brightest smile and patted him on the arm. ‘I’m desperate to get in front of the fire and warm up, it was absolutely freezing up there today. Oh, and I’m afraid I rather upset those cows when I landed. Do you think you could send a thank you to your man … Jessops, is it? Perhaps some cider or something? He was ever so helpful, moving the cows to another field. And I’ve left the Moth in a barn.’

Charles laughed.

‘Poor Jessops. Yes, of course I can. I’m visiting him tomorrow. I’ll take something to him then.’

I kissed Charles again, with a little more enthusiasm this time, before striding across the hallway and placing my hand on the sitting room door handle. ‘Is Lottie in here?’

Charles nodded. Smiling, I slipped off my muddy flying boots and turned the brass knob on the large panelled door.

Lottie was dozing on a large sofa by the bay window. A King Charles Spaniel lay by her feet. An embroidered shawl, the most perfect shade of russet red, was wrapped around her shoulders.

‘Juliet!’

Lottie, stirring at the sound of the door, threw her legs off the sofa and crossed the room to hug me. ‘I’ve been waiting for you all afternoon. We saw you fly past ages ago. Charles imagined you dead in a ditch somewhere, although why a ditch always has to be involved whenever anyone goes missing is beyond me.’ She took a step backwards to look me up and down. ‘But looking at the state of you, I think you really have been in a ditch!’ She turned to Charles who had followed me into the room. ‘Do leave us to catch up in peace, Charles! And perhaps arrange for some tea?’

Charles shook his head in mock disapproval, crossed the room to kiss me once more before turning on his heels to leave us alone. Lottie returned to the sofa while I mothered around her, straightening her shawl around her shoulders. It was Lottie’s comfort shawl from school, the thing she always turned to in moments of distress (that and a book of Christina Rossetti poetry). This wasn’t a good sign. If the shawl was out, before you knew it the poetry books would also be out and Lottie would spiral into a depression that could last for weeks. The door clicked shut.

‘Good, he’s gone!’ Lottie said, lounging back into the sofa. ‘So, tell me, what have you really been up to all afternoon?’

I was just about to sit down myself and launch into a watered-down version of the truth when the door clicked open again and Charles’ mother rushed into the sitting room carrying a bed sheet.

‘Ah, Juliet. You made it. Jolly good …’ She glanced at my clothes and then at the bed sheet. ‘It’s because of the oil, dear,’ she said kindly, before laying the sheet across a chair.

‘Sorry, Ma,’ (Lottie insisted I called her this, although Mrs Lanyon and I both seemed to wince every time I said it) ‘But I did take my muddy boots off in the hallway.’

She glanced at my stockinged feet – men’s stockings – and patted me on the head as I sat down – ‘Thank you, Juliet. Most considerate.’ She pulled the bell for tea, sat down and started to chat, leaving Lottie to roll her eyes with annoyance at having had her confidential catch-up delayed.

The late afternoon passed pleasantly. Charles reappeared with the maid, Katie, who brought tea and a few eats, and we all caught up in the civilised manner befitting gentle folk who lived in a house like Lanyon. Final plans for the wedding were made, and it was only when Ma and Charles retired to dress for dinner that Lottie and I finally found a few moments to be alone. We sat in a delicious silence at first. I was perched on the end of her sofa, having dragged the sheet with me to tuck underneath my oil-stained clothes. We stared out into the darkness of the garden, which in daylight had uninterrupted views across the grounds to the ocean beyond, but at night was one long expanse of black, except for the moon, which was almost full and served to backlight a line of cedar trees perfectly, the moon shadows throwing glorious patterns across the lawn and river of silver through the sea.

‘I don’t know why I’m asking,’ Lottie said, breaking the silence. ‘But have you given any thought to what you might wear to the wedding?’

‘Oh, I’ve brought a warm woollen suit that belonged to Mummy. That will do, I suppose.’

Lottie shook her head in frustration. I pressed on.

‘But it’s winter, Lottie! And it’s very smart, too. Truly it is.’

‘But it’s your wedding day, Juliet. I can’t understand why you’re keeping it so simple.’

I began to play with a tassel on Lottie’s shawl.

‘Charles and I agreed – no fuss. And your Ma was relieved on the “no fuss” front, too. There might be a war. It doesn’t do for the big house to start being extravagant in front of the tenants. And I’ve got no one to invite, no one at all. I’d much rather spend Pa’s money on a new aircraft …’ I sat up. ‘Oh, did I tell you? There’s this fabulous little monoplane coming out soon and it’s …’ Noticing Lottie glance down at her very slightly swollen belly, I stopped. ‘Well anyway, that’s just a bit of a dream. But what about you.’ I tried to buoy her up. ‘What will you wear?’

She shrugged, disconsolate.

‘I know!’ I said, not waiting for an answer. ‘You should wear your cream cashmere two-piece. The one I bought in you in Paris.’

Lottie shook her head.

‘I was going to. But Katie can’t do the zip up anymore. And anyway, I want you to wear it.’

‘Me! But … look at my hands, Lottie! I’ll never get them clean enough to wear cream.’

‘I thought of that. I’ve told Katie to scrub them. No buts. It’s been laid out on the end of your bed. I knew you wouldn’t have brought anything suitable.’ She glanced at my clothes. ‘Just look at you, Juliet. I mean to say, have you even brought any decent clothes? You do know there’s a party here tomorrow evening? In your honour, I might add.’

I went back to the tassel.

‘I managed to pack a few bits and bobs. But truly, Lottie, it’s difficult to fit anything in the old Moth, what with the tools I carry and so on …’ My voice petered out.

Lottie wasn’t listening. She stirred herself sufficiently to leave the comfort of the chaise and cross to the fireplace to ring the bell. Katie appeared.

‘Katie, please escort Miss Caron to her room – via my room. Do not allow her to deviate. Wash her hands and help her to pick out a dress for dinner this evening, and for tomorrow evening, too. And when she finally steps out of the dreadful clothes she’s wearing, wash them and when she’s not looking, give them to the poor, although the poor probably won’t want them so you might as well burn them.’

‘Lottie!’

Katie tried to hide a smile. I made tracks towards the door.

‘Oh, and Katie …’ Lottie added, forcing Katie to pause at the door.

‘Yes, Ma’am?’

‘Tomorrow’s dress should be something stunning for Miss Caron. And don’t forget to take that tweed suit I pointed out for yourself, too. I don’t need it anymore and it will be nice for you to wear it over Christmas …’

Katie’s eyes widened.

‘Thank you ever so much, Ma’am.’