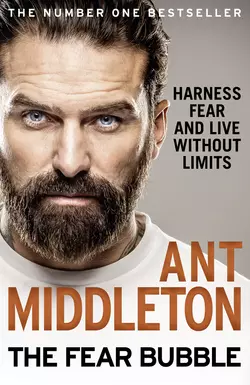

The Fear Bubble: Harness Fear and Live Without Limits

Ant Middleton

The brilliant, inspirational next book by the author of the incredible No. 1 bestseller FIRST MAN IN. Without fear, there’s no challenge. Without challenge, there’s no growth. Without growth, there’s no life. Ant Middleton is no stranger to fear: as a point man in the Special Forces, he confronted fear on a daily basis, never knowing what lay behind the next corner, or the next closed door. In prison, he was thrust into the unknown, cut off from friends and family, isolated with thoughts of failure and dread for his future. And at the top of Everest, in desperate, life-threatening conditions, he was forced to face up to his greatest fear, of leaving his wife and children without a husband and father. But fear is not his enemy. It is the energy that propels him. Thanks to the revolutionary concept of the Fear Bubble, Ant has learned to harness the power of fear and understands the positive force that it can become. Fear gives Ant his edge, allowing him to seek out life’s challenges, whether that is at home, pushing himself every day to be the best father he can be, or stuck in the death zone on top of the world in a 90mph blizzard. In his groundbreaking new book, Ant Middleton thrillingly retells the story of his death-defying climb of Everest and reveals the concept of the Fear Bubble, showing how it can be used in our lives to help us break through our limits. Powerful, unflinching and an inspirational call to action, The Fear Bubble is essential reading for anyone who wants to push themselves further, harness their fears and conquer their own personal Everests.

(#uadee57d7-7e52-5758-ac5e-640da10e2c29)

COPYRIGHT (#uadee57d7-7e52-5758-ac5e-640da10e2c29)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

FIRST EDITION

© Anthony Middleton 2019

Cover design by Clare Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Cover photograph © Andrew Brown

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Anthony Middleton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780008194666

Ebook Edition © September 2019 ISBN: 9780008194697

Version: 2019-07-29

DEDICATION (#uadee57d7-7e52-5758-ac5e-640da10e2c29)

For my wife and children, who have been there for me without fail: Emilie, Oakley, Shyla, Gabriel, Priseïs and Bligh. You give me the driving force to become the best version of myself and to want to succeed at everything I do. You really are my everything. Never forget that.

CONTENTS

1 Cover (#u0588b0c4-4a9d-516e-a8e7-eedf7ef84ac3)

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Contents (#uadee57d7-7e52-5758-ac5e-640da10e2c29)

6 PROLOGUE

7 CHAPTER 1: TAMING THE GHOST OF ME

8 CHAPTER 2: HOW TO HARNESS FEAR

9 CHAPTER 3: THE ROAD TO CHOMOLUNGMA

10 CHAPTER 4: THE MAGIC SHRINKING POTION

11 CHAPTER 5: IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE LANKY BEEKEEPER

12 CHAPTER 6: THE FEAR OF SUFFERING

13 CHAPTER 7: THE ICEFALL

14 CHAPTER 8: THE FEAR OF FAILURE

15 CHAPTER 9: DEATH IS OTHER PEOPLE

16 CHAPTER 10: THE FEAR OF CONFLICT

17 CHAPTER 11: CONQUERING THE KING OF THE ROCKS

18 CHAPTER 12: EVERYONE’S SECRET FEAR

19 CHAPTER 13: REVENGE OF THE KING

20 CHAPTER 14: THE OPPOSITE OF FEAR

21 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

22 By the Same Author

23 About the Publisher

LandmarksCover (#u0588b0c4-4a9d-516e-a8e7-eedf7ef84ac3)FrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiii (#ulink_b8e5f639-ed98-54ad-ab18-fb725d4e72e3)iv (#ulink_ce018941-b66b-5601-91b5-f2b2ded81531)v (#ulink_a89b5296-c48d-5a5a-826c-012849d69905)1 (#ulink_136586df-9e67-58fd-8aa8-00563351122b)2 (#ulink_a42dfd5f-289c-5371-8dbf-357871de1f2d)3 (#ulink_0702f46e-3139-5748-bd0c-726405bb580d)4 (#ulink_ffb42451-034f-5c77-a3d1-cc0b7f29a65c)5 (#ulink_335d19d6-6616-57f8-a8e1-3e5263a83763)7 (#ulink_85586892-3581-5167-88e9-9e6c6096f245)8 (#ulink_72c5e8ec-8dc8-5d3b-a157-ec5e1894af74)9 (#ulink_461d1d51-fa42-5a37-a391-e791d3a3d1f4)10 (#ulink_4572f252-b353-5821-ad2f-cf54d99446e7)11 (#ulink_8acd531e-cda6-56f5-a4fd-ce7a4838c277)12 (#ulink_53765ad5-dcd8-5a3b-83d5-dbbb1792da7e)13 (#ulink_70de444f-7ada-5964-be58-acdbb552a37f)14 (#ulink_db8230ac-a3c3-5845-8537-047e17b3ca43)15 (#ulink_46008e3a-a494-5bde-b2ec-ad9f2c11f58a)16 (#ulink_3aa134a6-b315-5f31-9085-ed506cbc1f15)17 (#ulink_ebc610c4-a2ed-553c-a376-8b454f60ebbc)18 (#ulink_7b1dcd27-d8be-5fa2-a696-6e8bc3942c42)19 (#ulink_11b6fd35-3c72-5776-bad8-b2f24d5cc3a1)20 (#ulink_b6c5af19-3636-5d59-ae68-3ac2fc92ac47)21 (#ulink_20fd552f-72c3-5de6-87d7-6e4fc9e05bb0)22 (#ulink_fcd0b88a-20ae-5ea7-aa18-bfd8b047b6b7)23 (#ulink_37029a47-2fdc-571c-9ef3-cb374f20e36a)24 (#ulink_85fc2f10-c44a-55f8-aaf0-a9dab1c4e4e8)25 (#ulink_3be4b908-f94f-535a-8ef9-b88e8bd5fe17)26 (#ulink_2d6e3d29-9c0d-5441-808d-1c7c2bd25313)27 (#ulink_e0af4bcf-a4ff-5a40-b0fe-599869e01b52)28 (#ulink_3cf0a82b-ea43-512b-8412-6b40a5f2a389)29 (#ulink_be29e7d2-9b63-5dfd-b08d-90dd97e96b7d)30 (#ulink_21141fae-5454-5082-91da-961644f3aa45)31 (#ulink_2a7c92f9-216c-5bac-99b1-d2369509c560)32 (#ulink_e6dcdb95-fa83-5325-9a86-b87f04b93f2d)33 (#ulink_2bfb3097-d8fc-59e7-8c26-abd91959af45)37 (#ulink_f5b9c302-3abc-52c5-8e7c-f10b102a6e93)38 (#ulink_4725a7cf-51e5-521f-a3b9-841b3c02d912)39 (#ulink_14b4b649-c45b-51d9-b925-8755a9b9d6f6)40 (#ulink_5aa2ef1e-241e-51c7-b5a4-805cf973fa29)41 (#ulink_6e91b04e-6468-56cd-a90f-c4a6c40667e5)42 (#ulink_d649a94a-f7ec-5f4d-8d25-e569831992b7)43 (#ulink_bee13746-7272-5f2b-8422-0d3d464fecb9)44 (#ulink_826e8f57-4b23-5b60-8f49-032c086693d0)45 (#ulink_280b22fc-7991-5fcd-8eeb-dca3c9096453)46 (#ulink_4c458ce1-8663-509a-baf9-5b370d57033d)47 (#ulink_32e43d81-a940-5e56-93b9-8eba1869f8ec)48 (#ulink_ac48a5b1-5ec8-5090-beb9-e68834587458)49 (#ulink_300d4c23-4918-5b79-9f60-a054d557d942)50 (#ulink_e747e04f-ca62-58cd-9169-a98588d04ba0)51 (#ulink_4d220c14-eb37-587c-bf60-6c55266dbf2d)52 (#ulink_0fbd3281-7920-56cd-a25d-9fb25dd7b805)53 (#ulink_2b5b234f-c209-59f1-997c-66a9da6364b7)54 (#ulink_c1ba7340-30f4-551a-a8fa-b30269c0ab42)55 (#ulink_dbe6e5e8-bf5f-513b-bc5b-77af027a2ab5)56 (#ulink_2e45df64-67b5-5f51-817e-6250c0027229)57 (#ulink_2bf18762-bf6c-5ca3-972e-24344deb9b93)58 (#ulink_f2992bcb-6cf0-5321-ad0e-030e8849dcfb)59 (#ulink_a78af9fd-3c36-5a0e-8426-e9f6d3db56ee)61 (#ulink_cd513025-116b-50b5-9a68-75dc4af35bc5)63 (#ulink_a134e165-6547-56e5-870f-37518480b6ab)64 (#ulink_1e84449f-4b07-5c7e-b2d9-1264d91373a7)65 (#ulink_3bcb4ac6-464e-5d4c-980c-ac8fcafdb879)66 (#ulink_230f0628-e662-548b-adae-fdbff99da839)67 (#ulink_b4810051-500f-57db-8c1d-63ce50f93224)68 (#ulink_47fdf51b-a62b-5503-a36e-abca74a9e07d)69 (#ulink_31918496-4acb-5df3-8035-6ee253260e28)70 (#ulink_032ac34a-5687-5b22-b8ca-01f700ccde66)71 (#ulink_74953a3c-c1a4-573d-8ebc-545d9dc50cc9)72 (#ulink_83ecba2a-ee46-5fef-838d-ee3663bc22fb)73 (#ulink_bb7169fe-8860-55f8-8868-94162097c7d9)74 (#ulink_8e693efd-8ead-5a39-b4bc-709a886d7a18)75 (#ulink_57b032a5-f12d-5c2b-93b8-afdc8014c1dd)76 (#ulink_b7795534-e3f6-5ee0-b612-23a7bae65eff)77 (#ulink_6721c2a4-d36f-5ee9-8866-df08674461ec)78 (#ulink_87adee47-aee5-5772-b9cd-aab4d9966528)79 (#litres_trial_promo)80 (#litres_trial_promo)81 (#litres_trial_promo)82 (#litres_trial_promo)83 (#litres_trial_promo)84 (#litres_trial_promo)85 (#litres_trial_promo)86 (#litres_trial_promo)87 (#litres_trial_promo)88 (#litres_trial_promo)89 (#litres_trial_promo)90 (#litres_trial_promo)91 (#litres_trial_promo)92 (#litres_trial_promo)93 (#litres_trial_promo)94 (#litres_trial_promo)95 (#litres_trial_promo)96 (#litres_trial_promo)97 (#litres_trial_promo)99 (#litres_trial_promo)101 (#litres_trial_promo)102 (#litres_trial_promo)103 (#litres_trial_promo)104 (#litres_trial_promo)105 (#litres_trial_promo)106 (#litres_trial_promo)107 (#litres_trial_promo)108 (#litres_trial_promo)109 (#litres_trial_promo)110 (#litres_trial_promo)111 (#litres_trial_promo)112 (#litres_trial_promo)113 (#litres_trial_promo)114 (#litres_trial_promo)115 (#litres_trial_promo)116 (#litres_trial_promo)117 (#litres_trial_promo)118 (#litres_trial_promo)119 (#litres_trial_promo)120 (#litres_trial_promo)121 (#litres_trial_promo)122 (#litres_trial_promo)123 (#litres_trial_promo)124 (#litres_trial_promo)125 (#litres_trial_promo)126 (#litres_trial_promo)127 (#litres_trial_promo)128 (#litres_trial_promo)129 (#litres_trial_promo)130 (#litres_trial_promo)131 (#litres_trial_promo)132 (#litres_trial_promo)133 (#litres_trial_promo)134 (#litres_trial_promo)135 (#litres_trial_promo)136 (#litres_trial_promo)137 (#litres_trial_promo)139 (#litres_trial_promo)140 (#litres_trial_promo)141 (#litres_trial_promo)142 (#litres_trial_promo)143 (#litres_trial_promo)144 (#litres_trial_promo)145 (#litres_trial_promo)146 (#litres_trial_promo)147 (#litres_trial_promo)148 (#litres_trial_promo)149 (#litres_trial_promo)150 (#litres_trial_promo)151 (#litres_trial_promo)152 (#litres_trial_promo)153 (#litres_trial_promo)154 (#litres_trial_promo)157 (#litres_trial_promo)158 (#litres_trial_promo)159 (#litres_trial_promo)160 (#litres_trial_promo)161 (#litres_trial_promo)162 (#litres_trial_promo)163 (#litres_trial_promo)164 (#litres_trial_promo)165 (#litres_trial_promo)166 (#litres_trial_promo)167 (#litres_trial_promo)168 (#litres_trial_promo)169 (#litres_trial_promo)170 (#litres_trial_promo)171 (#litres_trial_promo)173 (#litres_trial_promo)174 (#litres_trial_promo)175 (#litres_trial_promo)176 (#litres_trial_promo)177 (#litres_trial_promo)178 (#litres_trial_promo)179 (#litres_trial_promo)180 (#litres_trial_promo)181 (#litres_trial_promo)182 (#litres_trial_promo)183 (#litres_trial_promo)184 (#litres_trial_promo)185 (#litres_trial_promo)186 (#litres_trial_promo)187 (#litres_trial_promo)188 (#litres_trial_promo)189 (#litres_trial_promo)190 (#litres_trial_promo)191 (#litres_trial_promo)193 (#litres_trial_promo)195 (#litres_trial_promo)196 (#litres_trial_promo)197 (#litres_trial_promo)198 (#litres_trial_promo)199 (#litres_trial_promo)200 (#litres_trial_promo)201 (#litres_trial_promo)202 (#litres_trial_promo)203 (#litres_trial_promo)204 (#litres_trial_promo)205 (#litres_trial_promo)206 (#litres_trial_promo)207 (#litres_trial_promo)208 (#litres_trial_promo)209 (#litres_trial_promo)210 (#litres_trial_promo)211 (#litres_trial_promo)212 (#litres_trial_promo)213 (#litres_trial_promo)215 (#litres_trial_promo)217 (#litres_trial_promo)218 (#litres_trial_promo)219 (#litres_trial_promo)220 (#litres_trial_promo)221 (#litres_trial_promo)222 (#litres_trial_promo)223 (#litres_trial_promo)224 (#litres_trial_promo)225 (#litres_trial_promo)226 (#litres_trial_promo)227 (#litres_trial_promo)228 (#litres_trial_promo)229 (#litres_trial_promo)230 (#litres_trial_promo)231 (#litres_trial_promo)232 (#litres_trial_promo)233 (#litres_trial_promo)234 (#litres_trial_promo)235 (#litres_trial_promo)236 (#litres_trial_promo)237 (#litres_trial_promo)239 (#litres_trial_promo)241 (#litres_trial_promo)242 (#litres_trial_promo)243 (#litres_trial_promo)244 (#litres_trial_promo)245 (#litres_trial_promo)246 (#litres_trial_promo)247 (#litres_trial_promo)248 (#litres_trial_promo)249 (#litres_trial_promo)250 (#litres_trial_promo)251 (#litres_trial_promo)252 (#litres_trial_promo)253 (#litres_trial_promo)254 (#litres_trial_promo)255 (#litres_trial_promo)256 (#litres_trial_promo)257 (#litres_trial_promo)259 (#litres_trial_promo)261 (#litres_trial_promo)262 (#litres_trial_promo)263 (#litres_trial_promo)264 (#litres_trial_promo)265 (#litres_trial_promo)266 (#litres_trial_promo)267 (#litres_trial_promo)268 (#litres_trial_promo)269 (#litres_trial_promo)270 (#litres_trial_promo)271 (#litres_trial_promo)272 (#litres_trial_promo)273 (#litres_trial_promo)274 (#litres_trial_promo)275 (#litres_trial_promo)276 (#litres_trial_promo)277 (#litres_trial_promo)278 (#litres_trial_promo)279 (#litres_trial_promo)280 (#litres_trial_promo)281 (#litres_trial_promo)282 (#litres_trial_promo)283 (#litres_trial_promo)286 (#litres_trial_promo)287 (#litres_trial_promo)288 (#litres_trial_promo)289 (#litres_trial_promo)290 (#litres_trial_promo)291 (#litres_trial_promo)292 (#litres_trial_promo)293 (#litres_trial_promo)294 (#litres_trial_promo)295 (#litres_trial_promo)296 (#litres_trial_promo)297 (#litres_trial_promo)298 (#litres_trial_promo)299 (#litres_trial_promo)300 (#litres_trial_promo)301 (#litres_trial_promo)302 (#litres_trial_promo)303 (#litres_trial_promo)305 (#litres_trial_promo)306 (#litres_trial_promo)307 (#litres_trial_promo)308 (#litres_trial_promo)309 (#litres_trial_promo)310 (#litres_trial_promo)311 (#litres_trial_promo)312 (#litres_trial_promo)313 (#litres_trial_promo)314 (#litres_trial_promo)315 (#litres_trial_promo)316 (#litres_trial_promo)317 (#litres_trial_promo)318 (#litres_trial_promo)319 (#litres_trial_promo)321 (#litres_trial_promo)322 (#litres_trial_promo)323 (#litres_trial_promo)324 (#litres_trial_promo)325 (#litres_trial_promo)326 (#litres_trial_promo)327 (#litres_trial_promo)328 (#litres_trial_promo)329 (#litres_trial_promo)330 (#litres_trial_promo)331 (#litres_trial_promo)332 (#litres_trial_promo)333 (#litres_trial_promo)334 (#litres_trial_promo)335 (#litres_trial_promo)336 (#litres_trial_promo)337 (#litres_trial_promo)338 (#litres_trial_promo)339 (#litres_trial_promo)340 (#litres_trial_promo)341 (#litres_trial_promo)342 (#litres_trial_promo)343 (#litres_trial_promo)ii (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#uadee57d7-7e52-5758-ac5e-640da10e2c29)

There were ten of us up there, single file up a narrow track of rock and ice. The going was hard, the incline steep. We’d been up and out of our sleeping bags since dawn, with heavy daypacks strapped to our backs, and were hungry and thirsty and tired. Toes were sore and fingers were numb. The freezing air dried our mouths. I’d never been so high off the ground. The climb was such that we were half-crawling, ankles bent, hands grabbing at anything that looked as if it might take our weight. There wasn’t much time to look around and take in the view, but with every glimpse upwards I took I could sense the world getting bluer and bigger around us as the sky swelled into a high dome. With every movement of arm, leg and lung, we were leaving our everyday lives further behind and inching higher into the heavens. It felt rare and unsettling.

The further we climbed, up towards the mountain’s famous pyramidal peak, the thinner the track became and the slower the going. Nobody was talking any more. There was no laddy banter or gruff words of encouragement among the men, only grunting and panting and the silence of intense concentration. As I pushed on, I kept reminding myself that we were walking in the steps of my mountaineering hero Edmund Hillary, who’d penetrated these glacial valleys, known hereabouts as ‘cwms’, and scaled these icy cliffs more than six decades ago. We were way above the birds, it seemed, intruding into the realm of the gods and playing by their rules. I tried not to focus on the height or the danger, although I could feel the fear as a kind of tense sickness in my gut. This was getting serious. A couple of steps to the right and you were off the mountain. Dead.

A crack. A cry.

‘Shit!’

A rock the size of a cannonball flew past my face, missing my jaw by about half an inch. It was so close I could smell its cold metallic tang as it shot by. I lurched out of the way, skidding on the track, almost following the rock down. Above my head a brown boot scrabbled on the snowy scree for purchase. I looked down to see the rock being swallowed by the abyss, smacking and echoing as it bashed down the mountainside. An icy wind blew around my neck and face.

‘You all right?’ I shouted up.

The lad above me was gripping on to the mountainside, as if the earth itself were shaking. His cheeks were pale, his shoulders slumped, his gaze rigid.

‘Yeah,’ he said. And then, with a little more assurance, ‘Yes, mate.’

I watched him steel himself and try swallow his dread. He turned to carry on.

‘Good man.’

He lifted his leg once again, trying to find a more secure foothold. But then he paused, his boot hovering mid-air. He sucked in tightly through his chapped lips, breath billowing out.

‘I’m coming down,’ he said. ‘It’s, er … I’m, er …’

I thought he was going to lose it. His breathing became rapid and he started looking all around him, as if surrounded by invisible buzzing demons.

‘Just take it slow,’ I shouted up.

As he picked his way past me, I pressed my body into the freezing incline. His fear was infectious. I wanted so badly to go with him. It was safe down there. There was tea and biscuits and shelter. What the fuck was I doing up here? What was the point? What was I trying to achieve? The mountain didn’t want us crawling up it like fleas, it was making that all too obvious. It was trying to shake us off, one by one. Who was I to think I could take it on? Who was I to think I could succeed where Hillary himself had struggled? How was I supposed to know where to put my feet? The guy in front of me had placed his foot on a rock that looked like it had been rooted in place for a thousand years, and it had nearly made him fall off the mountain and taken me with him.

‘What you doing, Midsy?’ came a frustrated voice from below. ‘Come on!’

I had to make a decision, one way or the other. I had to commit. Up? Or down?

Up.

I pushed myself back into a climbing position. The instant my body followed my mind’s instruction, something incredible happened. The entire mountain changed. It wasn’t trying to shake me off any more – it was pulling me towards it. Every rock had been put there, not to trick me, but to help me. When they worked loose from the mountainside and gave way, that wasn’t the mountain trying to kill me, that was the mountain telling me where not to put my feet. These icy gullies weren’t death slides, they were ladders. Look how beautiful it was up there. I’d never seen anything like it. I’d never felt anything like I was feeling, right then. I would achieve this. I would fight the fear. I would use it like fuel. I would make it up there, to the top of the world, to the seat of the gods. I would conquer heaven.

CHAPTER 1

TAMING THE GHOST OF ME (#uadee57d7-7e52-5758-ac5e-640da10e2c29)

Twenty Years Later

‘Light?’

‘Cheers, buddy.’

I took a few rapid, light puffs of my cigar and heard it crackle into life between my fingers. The smoke that licked the back of my throat was rich and smooth, almost spicy. I took a deeper draw and peered at its glowing end. You could taste that it was expensive. But was this really £400 worth of cigar? That would make it, what, five quid a puff? I settled more deeply into the leather club chair and drew again, this time luxuriating in the experience, allowing the smoke to slide out through my lips gradually and wreathe about my face in silky ribbons. Before it dissipated, I took a sip of the rare single malt whisky my new barrister friend Ivan had also bought me, this time at the bargain price of £60 a shot.

‘So, how are you enjoying your new life?’ he asked me, his accent as cut-glass as the tumbler in my hand.

His wry expression told me he probably wasn’t expecting an answer. After all, wasn’t it obvious? To all outward appearances my new life was going brilliantly. I’d seen my face on billboards, and my latest TV show Mutiny had been broadcast to millions of viewers and enjoyed critical acclaim. If that wasn’t enough, I was in the middle of a sold-out tour of the UK. Every night, in a different town, I’d spend a couple of hours on stage, talking thousands of fans through some of my favourite moments, not just from Mutiny but from two series of SAS: Who Dares Wins. I’d then be whisked away in a black Mercedes with tinted windows to a five-star hotel where an ice-cold beer and twenty-four-hour room service were waiting for me.

And here I was being wined and dined by a top barrister in one of the most exclusive and secretive private members’ clubs in the world. If you’ve not heard of 5 Hertford Street, it’s because the owners like it that way. If you walked past it, you wouldn’t know it was there. It’s set in a warren of closely packed streets in Shepherd Market, Mayfair, a corner of the capital that used to bristle with high-class vice and scandal but now, aside from a red light bulb or two that shines out of an upstairs window, is polished and prim and postcard perfect. Downstairs, I could hear the faint bass throb of music coming from Loulou’s, its nightclub. Next door, the beautiful faces of London high society ate Sicilian prawns or duck with broccoli in the restaurant, their scrubbed and trimmed dogs at their side. This was where billionaires, moguls and the aristocracy of both Hollywood and Britain’s most gilded families went for their Friday-night drinks. And tonight I was among them.

‘So, you’re enjoying it, I take it?’ Ivan asked again.

‘What’s that?’ I said.

‘Is everything all right, Ant? You’re miles away.’

‘Oh, sorry, bud,’ I smiled. ‘Yeah, it’s not bad. It’s OK. I’m bedding in.’

Ivan was one of the elite. He fitted right in to this place, gliding over the sumptuously patterned carpets and past the heavy, gilt-framed paintings with graceful ease. The fact was, with his blue pinstriped Turnbull & Asser suit, his wide pale yellow tie rakishly unknotted and his long fringe swept back, he’d have fitted right in anywhere in the monied world – London, Singapore, Frankfurt or Dubai.

‘Well, yes, I can quite imagine,’ he said. ‘It must be a rather different experience being entertained here than it was back in the mess.’

‘The mess?’

‘That’s right, isn’t it?’ He swirled the golden liquid in his glass and absent-mindedly watched the lights dance across its surface. ‘In the military. Where you ate. The mess. That is what you call it? I’ve always thought that rather odd.’

‘Why odd?’

‘Well, it’s a joke, I take it. Irony. Military humour.’ His eyes flicked up. ‘I mean, you know, are they messy places? One would rather imagine not.’

Between us there was a small mahogany table on which sat a heavy, polished-iron ashtray in the shape of a leaf. I tapped my cigar onto its edge and found myself mentally weighing it. It was big. Hefty.

‘It’s French,’ I told him. ‘From the word “mets”, meaning a dish or a portion of food. It’s not because it’s …’

‘Oh, is that so!’ he said, laughing. ‘Of course. Yes, I should have known. Yes, yes, how silly of me. The French.’ He kind of half-winked in my direction. ‘That was an impressive stab at a French accent there, by the way, Ant. It felt, just for a moment, as if I’d been whisked away to the harbour at St Tropez.’

Yeah, that ashtray had to weigh a good three or four kilos. Maybe more. You could do some proper damage with that. Put a door in. In fact, you could put someone’s head in with that thing. Easily. I’d use the bottom edge. Curl my fingers into the bowl, get some proper purchase on it and wear it like a knuckle-duster. Wallop.

‘I grew up in France, as it happens,’ I told him.

‘In France? Well, I never. Whereabouts?’

‘So I’m fluent in French.’

‘Well, bravo,’ he said, raising his glass. ‘Cheers to you. And I do hope we can come to some arrangement over this company retreat in April. We’ll fly you in first-class. It would be a real morale booster for the firm to have you come along and speak to the troops, even if they’re not of quite the same physical calibre as the troops you’re used to working with. Although, saying that, some of the chaps and chapesses in the office are terribly into the fitness scene – it’s quite impossible to get them out of the gym at lunchtimes. But it gets harder as you get older, doesn’t it? I expect this new phase of your career has come at just the right time for you. Even if you do miss the military life, when you get to our age, it’s … I mean, you’re clearly in very fine shape. I try to keep in reasonably decent order myself. But the selection process. The SAS. Do people our age do it? People in their forties?’

‘Ivan, mate, I’m thirty-seven,’ I said.

‘Of course you are. I’m so sorry. I didn’t mean to imply … Of course you could still pass Selection. You’d fly through it. You’ve only got to see your television programmes …’ He was beginning to bluster.

‘Ivan, mate, it’s totally fine,’ I said, laughing. ‘Forget it. Fucking forties! What are you like?’

As he relaxed once again, he began telling me about his own fitness regime. No carbs after 6 p.m., forty-five minutes in his home gym three times a week, a personal trainer called Samson. As I listened, enjoying my cigar, I found myself beginning to wonder, what would happen if it all kicked off in a place like this? What if Isis came through the door? A lone shooter or a guy in a bomb vest? What would Ivan do? How would that waiter over there respond? Rugby tackle him? Go for his legs? Or shit himself and dive under the table? I scanned the people around me. They’d go into a flat panic. Every single one of them.

I know what I’d do. I’d head-dive into cover, down there in the corner, and then I’d come around and try to disarm him. I’d use the ashtray as a weapon. I’d crack it right over him. Right around the fucking face. Smack. Cave in his cheekbone and then go straight into a backswing, push his chin up into his nose. God, I would love to see it kick off in here. That old geezer in the corner in the bow tie just turning around head-butting that fat dude with the pink hanky in his top pocket – landing it perfectly between the eyes, knocking the cunt into the fire. That woman in the lily dress giving the terrorist a proper crack in the jaw, bursting his nose open with that massive jewel on her finger. Some old Duke being kicked down the stairs by a minor royal in stilettos. Yes. Yes! What would it take for this place to go up? I would pay good money to see that.

‘To success!’ said Ivan. Suddenly, I was back in my body. The room instantly reorganised itself back into its hushed, murmuring and peaceful state. There was no blood on the walls or scalp on the carpet. The stairs were empty of violence. I was no longer crouched on that £10,000 rug de-braining a terrorist.

‘Success!’ I replied.

I raised my glass and downed it all.

Success. Is this what it was? Warm rooms and expensive dinners? Small talk with top barristers about personal fitness and fat cheques for corporate events? An hour later, as I strode down to Green Park tube past pubs and art galleries and dark human forms hurrying along the wet pavements, I found myself brooding. When I left the Special Forces in 2011, I had no idea what I was going to do with the rest of my life. What could I possibly achieve that would be better than the buzz of leading a Hard Arrest Team in the badlands of various war zones over two intensely frightening and violent tours of duty? Life back home in Chelmsford, I quickly discovered, was not like life in Helmand Province. I found it difficult to adjust, ending up physically assaulting a police officer and serving time in prison. The easiest thing I could have done, when I hit those lows, was to join my friends and associates in their criminal gangs. It wasn’t as if they hadn’t tried hard and repeatedly to recruit me. Someone with my background, I knew, had enormous value to those kinds of organisations – and I’d be handsomely rewarded. I would certainly have ended up wealthier than I was now. And the excitement? Oh, that would have been there, no doubt about it.

As I reached the end of the dark, narrow corridor of White Horse Street, a young couple were walking in my direction. The girl, her pale face framed in a white parka hood, gave a slight double-take when she saw me. I hunched my shoulders and sent my gaze to the floor. Please don’t ask for a selfie. Not now. When they were safely in the distance I went to cross the road and waited at the kerb. The usually busy lanes of Piccadilly were at a rare lull. I looked left and then right. There were a couple of double-decker buses, one coming in each direction, both trailing a stream of taxis and vans behind them. I waited. And then I waited some more, allowing them to get even closer. At the final instant, just as they were about to roar past my face, I darted out, dodging one and then the other, feeling their fumes billow around me as I danced between them.

I knew only too well why so many former Special Forces operators ended up either on the street, traumatised and addicted, or working for a criminal firm. Because success in civilian life lacks something that we’ve come to crave. You can’t take it out of us. It’s in there for life. And it’s not the fault of the military training, either. You can’t blame that. The fact is, we’re simply those kinds of men. We exist on that knife edge. Go one way, they’ll end up calling you a hero, a protector of the public and the nation. Go just a little in the other direction and you’ll find yourself in prison, an enemy of the same public and the same nation. The extreme forms of training that admittance into the Special Forces demands don’t cause us to be these kinds of people. It just takes what’s already there, hones it, draws it out and teaches us to control it. The problem is, this quality doesn’t simply evaporate when you leave the SAS or, in my case, the SBS. It’s still in there. It’s in your blood. It’s in your daydreams. It’s in how you walk. It’s in the way you scan a room the moment you enter it, looking for entry and escape routes, pockets of cover and potential aggressors.

And it’s also in how you cross the road. I’d noticed myself doing that increasingly over the last few weeks. If I was in London, or in one of the traffic-choked streets in the centre of Chelmsford, and I saw a pedestrian crossing with the green man flashing, I wouldn’t run to catch it like everyone else. I’d slow down. I’d wait until the traffic was fast and raging again, and only then would I cross. I’d never do this in front of my wife Emilie and certainly not in front of my kids. To be honest, I was only half-conscious of doing it myself. I hardly even knew how to explain it, apart from to say that it was that edge I was after, that edge I would go looking for anywhere – a brief moment of danger to keep my heart beating and my spirit alive. That threat, that trouble, that fear. I was constantly looking for opportunities to push myself, test myself and add a little dose of risk to my otherwise overwhelmingly safe days.

So that was it. That was why Ivan had provoked a host of strange and uncomfortable emotions to come bubbling out from deep within me when he’d asked if I was enjoying what he called my ‘new life’. Of course I enjoyed its trappings. Who wouldn’t? It felt great to achieve so much in these areas of popular culture that I’d never have even dreamed of entering just a few years ago. You couldn’t deny I was successful. But this wasn’t my kind of success. I felt as if I were somehow losing my identity. And the problem was, my identity was beginning to fight back. I could feel it punching and kicking, whenever I was in meetings with guys like Ivan or in places like 5 Hertford Street. The warrior inside me would rise out of nowhere and take over my thoughts. I’d find myself daydreaming about terrorist attacks or mass brawls breaking out, building my strategy for dealing with the madness, assessing everyone around me in terms of how much of a threat they’d be and how I could take them out. This could happen to me anywhere – in the ground-floor canteen at Channel 4 or on the set of This Morning, waiting to be interviewed by Phil and Holly in front of millions of viewers. It was like I was being possessed by the ghost of the man who used to be me. And the really worrying thing was, these weren’t waking nightmares that left me in cold sweats. They weren’t PTSD-like moments of dread and horror. They were fantasies. I was willing them to happen.

After the deep orange darkness of London’s November streets, the lights inside Green Park tube station felt too bright, and I squinted a little as I ran down the long flights of stairs towards my platform, racing the people descending the escalators on either side of me. I found a quiet seat at the end of a carriage and jammed my hands into the pockets of my jacket. A few seats away from me a couple of girls sat opposite each other. They looked to be in their early twenties, and were giggling and laughing in that drunk schoolgirl way. One had taken her high heels off, and her bare toes were now blackened from the tube floor. An unopened bottle of WKD Red stuck out of her lime-green handbag. Another, open and half drunk, was clutched in her hands. The other girl wore a tight white mini-dress and had a tattoo of Michael Jackson on her arm. Her faux leather jacket lay on the seat beside her, along with their crumpled Burger King wrappers and boxes.

When I stepped into the carriage they’d been cackling loudly, but once they clocked me they fell into a hushed chatter, interspersed by periodic piggy, nasal snorts of laughter.

‘Here we go,’ I thought. ‘I’ve been spotted.’ But then I checked myself. Maybe not. One of the things about finding yourself unexpectedly well known – among certain parts of the general public, at least – is that it’s easy to become paranoid. You start to think that everyone’s watching you, wherever you go, even though most members of the public would never have even heard of you. Anyone who’s been on the TV for more than ten minutes has an embarrassing story to tell about a stranger coming up to them in the street, and them presenting their finest prime-time Saturday-night smile and preparing to quickly scribble out an autograph, only for that person to ask if they know the directions to the nearest McDonald’s.

The girls were now leaning into each other and whispering intensely. I wondered what they were they doing. Plotting their next assassination? I kept noticing their eyes swivelling out from their dark huddle and looking in my direction. Then they abruptly sat back, now not saying anything. Suddenly a phone appeared. It was in a black case with Michael Jackson picked out in fake diamonds, one hand on his trilby, the other on his crotch. The girl in the mini-dress was holding it directly in front of her face, but some distance away from her, like an old lady squinting at a book. Then it turned slowly in my direction. The girl looked upwards, now apparently closely examining the advert for student home insurance above the window opposite her. There was the faint electronic sound of a shutter being clicked. Her mate snorted with laughter. ‘Shut up!’ the first one hissed.

I wouldn’t mind if they’d asked. I never complain about being recognised or having to pose for selfies, as that would be ungrateful and disrespectful. And I’d hate – more than anything – to be perceived as being rude to anyone. Having said that, I always try to keep my head down when I’m out and about. I never pretend that I’m someone. I hate being in that mindset, thinking that I’m the centre of attention. But more and more, things like this kept happening. I’d leave the house and be reminded very quickly that my existence had changed. There wasn’t much I could do about it. This was the reality of the ‘new life’ that Ivan had been asking about.

It was a life that didn’t come without its own peculiar risks. I only had to walk out of a pub looking unsteady and some newspaper somewhere would print a story that I was an alcoholic. I only had to scowl in someone’s direction and it would be reported that I was in the middle of a heated argument. So I needed to make sure that my behaviour in public wasn’t merely immaculate – it could never even be perceived to be anything less than immaculate, even down to the expression on my face.

Maintaining that level of good behaviour wasn’t easy, especially for someone with a past like mine. It wasn’t a comfortable combination, all those eyeballs, all that stress – and my personality. The more I felt watched, the more that old, raucous version of me wanted to kick back. The intense pressure to behave immaculately – in trains, on the street and within private members’ clubs – taunted that unstable ghost living inside me. It goaded him and mocked him and motivated him to take me over. I felt him writhing around, pushing at me, tempting me to make chaos. As the girl took another photo, and this time barely bothered to pretend she wasn’t, I buried my fists deeper into my pockets and pushed my chin into the collar of my coat, as my left leg bounced up and down in nervous, aggravated motion. ‘I should’ve got a car back,’ I thought to myself. ‘Fuck this. I’m not taking the tube any more. I’m going to stop taking public transport.’

By the time I got to Liverpool Street station I’d done a lot of serious reflecting. What on earth was I thinking? Who was I turning into? Some TV celebrity puffing on £400 cigars who refuses to go on the underground? In that moment with the girls and the photos, it felt as if everything I was, everything I’d fought so hard to become, was at risk of getting lost. I didn’t want to fall head first into this new life, with its new definition of success. It wasn’t just that I was worried I’d change for the worse and become some spoiled ‘celebrity’. I was afraid that if I didn’t grab hold of the situation, the old me would fight back in a way that I couldn’t control. There was a genuine danger that I would revert to finding my buzzes elsewhere. That could be drinking. That could be fighting. That could be getting myself killed by a double-decker bus. Too many people were relying on me these days for that to happen. It wasn’t only my wife and five children. My life had somehow turned into a small industry. There were teams of people making serious parts of their livelihoods off the back of me, and all of them needed me out of prison and off the tabloid scandal pages, not underneath ten tonnes of steel and rubber in the middle of Piccadilly. My success and theirs were intertwined. I felt a responsibility to every single one of them.

But what could I do? How could I exorcise this ghost when I had all these eyeballs on me? Perhaps I could take a spell out of the limelight and go back to West Africa, where I’d carried out some security work before life in the media found me. That might be fun – I’d get into some interesting scrapes – but there was no way I’d get it past Emilie. It was too sketchy. I thought about running a marathon or taking up boxing in a serious way, but neither of these would really test me. I needed that perfect balance, somewhere I could feel fear but actually be relatively safe.

As soon as I had that thought, an incredibly vivid memory came to me. It was so powerful it was like being in a momentary dream, one that took me back all of twenty years, when I was seventeen. It was my first adventure training package in the army, and we’d climbed Snowdon in Wales. Before that day, during basic training, my life in the military had been extremely controlled. We’d been spit-polishing boots, doing drills and press-ups and running around in the mud, all under the instruction of barking troop sergeants, with almost every minute of every day being tightly regimented. Even though I’d been pushed to my limits, it had all been done in an environment of safety. I’d been scared and intimidated, but the only things I’d really had to fear were failure and humiliation – threats to my feelings. It had been fake danger. And then we’d climbed the mountain.

And it wasn’t just any mountain. It was Snowdon, at 3,560 feet the highest peak in England and Wales. It was said to be where Sir Edmund Hillary himself had trained for his successful assault on Mount Everest. When we reached the summit that day I remember thinking, ‘Fucking hell, I’ve just climbed a mountain!’ It felt like the greatest achievement of my life. I’d never experienced getting out into the world like that before. I’d never felt as if I’d truly conquered anything. And there I was, on top of the world, breathing the air of the gods.

But that wasn’t the only reason my memory of Snowdon was so precious. After my father suddenly died at the age of just 36, on 31 December 1985, my mum and her young boyfriend Dean moved the family from our three-bedroom council house in Portsmouth first to an eight-bedroom mansion outside Southampton, and then to northern France. Flush with money from my dad’s life-insurance payout, they bought a huge house that had once been a children’s home on a large plot of land on the outskirts of a town called Saint-Lô, twenty miles from Bayeux. Life with my mother and new step-father was tough, and my happiest times were the hours I’d spend tearing around in the fields and woods playing soldiers. I had a wild time, and even at that age I began to wonder about being an actual soldier when I was older.

As wild as those days had felt to me, however, they had really been lived within a controlled environment. Even when I stayed in one of my dens for two or three nights, someone would always have to know where I was. If I ever got into trouble I’d feel it. Part of why I wanted to join the army was my urge to re-create those experiences of wild adventure under open skies. But in the early weeks and months after I joined up, the experience had been more like being at home with my stepfather. I was always watched and pushed and corrected by a figure of authority.

All of that changed on my ascent of Snowdon. My most vivid memory of all, even more than of reaching the top, was when I saw the lad in front of me almost fall off a narrow track, right off the side of it. I’d seen the fear first grip him, then overwhelm him, and watched him give up the climb completely, fumbling his way back down to safety. I’d become infected with that same fear. It had soaked into me like a heavy, disabling liquid. I looked around me and realised I was on the edge of death. Anything could have gone wrong. I could have slipped. The weather could have come in. I could have got hypothermia or been blown off the mountain. I’d never experienced such vulnerability. For the first time, I felt that I had my own life in my hands. As the fear washed through me I had to make that decision. Do I listen to what it’s telling me? Or do I trust myself to do this? Do I go up? Or down?

It was that fear I remembered most. As I paced up and down the platform at Liverpool Street waiting for the Chelmsford train I was in a trance of memory, feeling it again as if it was all happening to me right now. That fear had almost beaten me. But the moment I’d committed to the decision to climb, an incredible transformation had taken place. My perception changed. It had been as if the mountain itself had stopped trying to hurl me down its precipitous flanks. Now, instead, it was drawing me up to its summit and I no longer felt as if I were on the edge of death.

Why had that change occurred? How had it happened? Partly, I realised, it was because, in making the decision to continue on upwards, I’d fully embraced the responsibility of my task. There were no rules on that mountain except for the ones I gave myself. There was no drill instructor telling me where to look or put my feet. There was no stepfather telling me what time I had to be in or where I could or couldn’t go. It was lawless up there. Amid the freezing blasts of wind I found an ecstatic sense of liberation on Snowdon that was completely new to me. I was in real danger on that narrow, icy track. If I made the wrong decision it was entirely down to me, and I alone would pay the price. That was petrifying. But it was also exciting. I was my own god up there. I felt completely alive in a way that I never had done before. I felt afraid – and I felt free.

I found a quiet seat on the train where no stray eyeballs or selfie cameras were likely to find me and excitedly pulled my phone out of my pocket. How long did it take to drive to Snowdon? I’d go up it again. Do it solo. The next weekend I had free. That’s it, it was decided. I wondered if I could remember the exact route we’d taken twenty years ago. It wasn’t one of the normal tourist routes. It was … I didn’t know. Well, what was the toughest way up? I opened up my web browser and typed in S.N.O. … I stopped. Snowdon? Really? I was seventeen when I’d done it. I was thirty-seven now, and a completely different man. I could walk up Snowdon in silk slippers. It just wouldn’t do. It wouldn’t give me what I needed. So what would? What’s the ultimate Snowdon? I went back to the web browser on my phone and deleted S.N.O. … In the place of those letters, I pecked out a new word.

E.V.E.R.E.S.T.

As the train wobbled to a start and began to rattle out of the station towards home, I excitedly scanned the results on Google. One page leapt out at me. A Wikipedia article: ‘List of people who died climbing Mount Everest’. I began reading.

Mount Everest, at 8,848 metres (29,029 ft), is the world’s highest mountain and a particularly desirable peak for mountaineers. Over 290 people have died trying to climb it. The last year without known deaths on the mountain was 1977, a year in which only two people reached the summit.

Most deaths have been attributed to avalanches, injury from fall, serac collapse, exposure, frostbite or health problems related to conditions on the mountain. Not all bodies have been located, so details on those deaths are not available.

The upper reaches of the mountain are in the death zone. The ‘death zone’ is a mountaineering term for altitudes above a certain point – around 8,000 m (26,000 ft), or less than 356 millibars (5.16 psi) of atmospheric pressure – where the oxygen level is not sufficient to sustain human life. Many deaths in high-altitude mountaineering have been caused by the effects of the death zone, either directly (loss of vital functions) or indirectly (unwise decisions made under stress or physical weakening leading to accidents). In the death zone, the human body cannot acclimatise, as it uses oxygen faster than it can be replenished. An extended stay in the zone without supplementary oxygen will result in deterioration of bodily functions, loss of consciousness and, ultimately, death.

Why did people die on the mountain every year? There must be something special up there. And what was this ‘death zone’ they were going on about? What did a death zone actually look like? What would it feel like to tackle one? It sounded as if you only got a certain amount of time to climb the mountain before you ran out of oxygen – that climbers used ‘oxygen faster than it can be replenished’. So it was like a race for your life. I felt my heart lurch with excitement. I scrolled down the page to the seemingly endless list of fatalities. The deaths started with the very first expedition to attempt to climb the mountain, undertaken by a British team in 1922. Seven Nepalese guys, who I guessed were helping them get to the top, died on the same day in an avalanche. Two years later, there was a Brit, Andrew Irvine: ‘Disappeared; body never found; cause of death unknown’. He was twenty-two. With him, another Brit, the famous George Mallory. ‘Disappeared; body found in 1999; evidence suggests Mallory died from being accidentally struck by his ice axe following a fall.’

As I kept scrolling, the deaths mounted up. Wang Ji, China, 1960, ‘mountain sickness’; Harsh Vardhan Bahuguna, India, 1971, ‘succumbed after falling and being suspended above a crevasse during a blizzard’; Mario Piana, Italy, 1980, ‘crushed under serac’. My eyes flicked across to the column that noted the causes of death. There were hundreds of entries, page after page: avalanche, avalanche, fall, fall, exposure, exposure, exposure, drowning, heart attack, high-altitude pulmonary oedema (HAPE), high-altitude cerebral oedema (HACE), exhaustion, organ failure due to freezing conditions. And these people were from all over the planet: Australia, Germany, Taiwan, Canada, Bulgaria, South Korea, the United States, Vietnam, Switzerland … Finally, I reached the end of the list. 2017. This year. Six deaths. An Indian, a Slovakian, an Australian, an American, a Nepalese and a Swiss guy. Causes of death? Everything from altitude sickness to ‘fall into a 200m crevasse’.

Of all the names I’d seen on that page, I’d only heard of one: George Mallory. I knew, of course, that Hillary had been the first man in, up on Everest’s summit, but why was Mallory so famous? I clicked on his name and began reading the article about him. It turned out that he’d taken part in the first three expeditions to the mountain, the first a reconnaissance expedition in 1921, the second two being serious attempts to ascend the peak in 1922 and 1924. He was last seen alive just 245 feet away from the summit, and it remains unknown whether he reached the top before his death. He’d served in the military, as a second lieutenant in the Royal Garrison Artillery, and fought at the Battle of the Somme. I noticed his age on the day he died.

Thirty-seven.

‘But Ant, you said Mutiny was your last thing.’

It was the following morning, just after 7.30 a.m., and I was disappointed to discover that 5 Hertford Street £60-a-shot whisky gives you exactly the same hangovers as the stuff from Tesco at £6.99 a bottle. My wife Emilie was at the counter with her back to me, preparing breakfast for our one-year-old boy. I’d forgotten I’d made that promise to her. But she was right. Mutiny, the TV show I’d filmed the previous year, re-created the 4,000-mile journey across the Pacific Ocean in a twenty-three-foot wooden boat undertaken by Captain Bligh and eighteen crewmen following the mutiny on HMS Bounty in 1789. That had been a tougher-than-expected sell when I’d first run it past her. Looking back, the idea was borderline insane. Together with the nine men I was responsible for, we’d braved wild storms, twenty-foot waves, starvation, dehydration and the onset of madness, and I’d only just made it back in time for the birth of the amazing boy – named Bligh – whom Emilie was now spooning mashed bananas into.

‘Well, I actually said Mutiny was the last stupid thing I’d do,’ I told her. ‘Everest isn’t stupid. Hundreds of people do it every year. It’s just a holiday, really. A camping trip.’

‘And how long will you be gone on this camping trip?’

‘Er, it takes about six weeks, give or take.’

‘Six weeks?’

‘Yeah, because you need to acclimatise. The air up the mountain is so thin you’ve got to give your body a chance to get used to it. So you go up a little way, rest and get used to the altitude, then you go down, rest some more, and then you go up again, but a bit higher.’

‘Sounds annoying.’

She was still in her pyjamas and had her hair pulled back in a loose ponytail. I often think of the word ‘angelic’ when I see Emilie. She has a perfect, heart-shaped face – her cheekbones are wide and high, and her chin forms the cutest little bump. Her eyes are large and dark green, speckled with brown that sometimes, in the right light, seems to glisten like pale gold. She has exactly the kind of face you’d imagine on an angel.

‘It’s just being careful,’ I told her. ‘It’s the safest way of doing things.’

I took the spoon off her and began feeding Bligh myself.

‘I’m not up for taking any risks up there, babes. This isn’t for a TV show or anything, so there’ll be no drama. It’s just a bit of fun. An old pal of mine from the military takes people up there every year. He’s got a company that does it. Proper professional outfit. Here you go …’

I unlocked my phone. The website of my friend’s organisation, Elite Himalayan Adventures, was still on my web browser from when I’d last looked at it. I passed it over to her and she picked it up warily. I’d spent the rest of my train journey the previous night reading pretty much every page of it. Elite Himalayan Adventures specialised in expeditions up the world’s fourteen highest mountains including Kangchenjunga on the border of Nepal and Sikkim, K2 in Pakistan, and the king of them all, Mount Everest. The page I showed Emilie highlighted the company’s emphasis on not putting their clients in any undue danger: ‘Safety will always be our priority, and all of our Sherpa guides are expert climbers and expedition leaders in their own right, who then undergo a rigorous selection and training process to ensure you get the safest, most informed and most professional climbing experience possible.’

‘Looks fun.’ She put the phone down and started noisily unloading the dishwasher. ‘But six weeks, Ant?’

‘Well, the entire trip, with actually getting to the mountain in the first place … I mean, you’re probably talking more like two months, if I’m honest.’

‘And how much is this two-month holiday going to cost?’ she said, over the sound of bowls being stacked in the cupboard.

‘It’s not exactly cheap. But we’re doing OK, aren’t we? I’ve been working hard.’

‘I know, Ant,’ she said, still not looking at me. ‘You have. It’s totally up to you. What are we talking, though? For the trip?’

‘It’s probably … I don’t know.’ I did know. ‘Sixty grand? Give or take?’

There was a silence. I watched her put a pile of plates down, slowly and gently on the counter, and then pull a chair out opposite me.

‘This isn’t a wind-up, is it?’ she said in disbelief once she’d sat down. ‘I can tell by your face it’s not a wind-up.’

I spooned another mouthful of banana into Bligh.

‘It’s just what it costs, babe.’

‘But why does it cost sixty grand?’ she said. ‘I mean, sixty grand? For a camping trip? How did they work that one out?’

‘Emilie, you’ve got to trust me. I need to get away. This new life we’re building is great but I’m beginning to feel claustrophobic. I keep having these thoughts. It’s hard to explain.’

I put the sticky spoon down and looked her in the eye.

‘I don’t want to muck anything up for us. I don’t want to do anything stupid. If I manage to behave myself, it’s just onwards and upwards for us and the kids. There’ll be no stopping us. But there’s a lot of steam building up. I can feel it. And if I don’t let it off up that mountain, I might end up doing it outside some bar or something. If I don’t get the buzz I need, I’m going to find that buzz myself, whether it’s breaking the law or offending someone or fighting someone. I can’t end up back in that place again. We’d lose everything. It is sixty grand. But you should see it as an insurance payment.’

‘It’s not dangerous, is it?’

‘Not for me it isn’t. I could walk up Everest backwards. They’ve had all sorts up there on the summit. Postmen. Celebrities. It’s just an adventure holiday. Just something to sort my head out.’

To be honest, there was never really any chance of Emilie standing in the way of my going. Although she sometimes worried about me, she always trusted me, and I always respected her enough to run anything I wanted to do past her. When I’d served in the military, she hadn’t been like the wives and girlfriends of some of the other men, worrying and fussing and distracting them with the anxieties and problems of home life. As had been my wish, Emilie just let me get on with serving my country when I went away, and that allowed me to keep my head clear and focused on the job in hand. She didn’t call. She didn’t write letters. And that’s exactly how I liked it. Her strength of character helped keep me alive. I’m not exaggerating when I say that Emilie has always been the perfect partner for me. We instinctively understand what each other needs and we always do our best to provide it. Me and her are an unbreakable team.

She also knew I wasn’t lying when I told her I could walk up the mountain backwards. In Everest I’d found the ideal challenge to tame that warrior ghost inside me, at least for the time being. Nobody could deny that climbing the world’s highest mountain was dangerous. Its list of confirmed kills was impressive. But I wasn’t just anyone.

I’d often told Emilie that I was invincible, and I wasn’t really joking. I didn’t really believe anything could kill me – and it was this belief that had kept me in one piece. Nothing that had ever been thrown at me had taken me out. All those people I’d read about on Wikipedia who’d fallen down crevasses or succumbed to exhaustion or organ failure or a cerebral oedema, whatever that was – I felt bad for them, but they weren’t me. Everest would give me a taste of the danger that I’d begun to crave, that was probably true, but it wasn’t going to pose me any genuine problems. If anything, it would be too easy. This would be a camping trip. A walk in the park.

‘Thanks, Emilie,’ I said, lifting Bligh out of his seat and cradling him against my shoulder. ‘I’ll get it booked.’

A sudden wave of excitement washed over me and I grinned in her direction.

‘How good is it going to be, standing on top of the world?’

CHAPTER 2

HOW TO HARNESS FEAR (#uadee57d7-7e52-5758-ac5e-640da10e2c29)

Why did I want to climb Mount Everest so badly? Why was I taking deliberate, crazy risks when crossing busy roads? Why was my mind slipping into violent fantasies at the very moment I was being made to feel most coddled, in a Mayfair private members’ club over expensive whisky and cigars? What kind of a man would imagine such horrific things? Believe me, I didn’t want a terrorist to come bursting in with an AK47 and a bomb vest because I’m some psychopath. I didn’t want people to get hurt. What I wanted was to be handed a reason to leap up and stop people being hurt. I wanted to be forced into action. I wanted to be put in a position in which I had no choice but to perform or die. What I wanted – what I’d started craving almost like a drug – was fear.

This might seem strange, but that’s what my relationship with fear is like. I crave it. I need it. And as much as I need it, I also dread it. As I travel up and down the country meeting people on my tours, one of the questions I always get asked is a variation on this – ‘How did you get to be so fearless?’ The answer is, I didn’t become fearless. I don’t believe that’s even possible. I feel fear all the time. Not only do I feel it all the time, I hate it. It’s not that I’ve learned to conquer fear or enjoy it. It’s that I’ve learned how to use it. My experiences fighting in Afghanistan with the Marines and serving as ‘point man’ as a member of the Special Boat Service, the first man in as part of an elite team that was charged with capturing some of the world’s most dangerous men, taught me that fear is like a wild horse. You can let it trample all over you, or you can put a harness on it and let it carry you forwards, blasting you unscathed through the finish line.

More than anything else, I believe that my ability to harness fear and use it to my advantage is the secret of my success. There’s no way I would have come out of Afghanistan, or any other theatre of war, in a healthy psychological state if I hadn’t learned how to do this. And more than that, there’s no way I’d have been a success in my personal or professional life if I hadn’t developed the ability to grab hold of the incredible power of human fear and let it take me where I wanted to go. I’ve now got to a place where I rely on fear. When it goes missing from my life I find myself becoming anxious and dissatisfied. Without fear, there’s no challenge. Without challenge, there’s no growth. Without growth, there’s no life.

INTO THE BUBBLE

This method for harnessing fear has changed my life in ways that are almost unimaginable. It’s transformed me from the naïve, angry and dangerous young man I once was to the person I am today. The good news is that anyone can learn it. I call it the ‘the fear bubble’.

Back when I was in the military, there were many times in the breaks between tours when I caught myself thinking that I didn’t want to return. The fear you experience on the battlefield is unbelievably intense. There are many different levels of fear, but ‘life or death’ is surely the worst of them all. Most people never experience the feeling that when they step around the next corner there’s a decent chance they’ll take a bullet in the skull. I had to deal with that time and time again.

Many amazingly brave and tough operators didn’t find a way of processing that level of fear and horror. I’ve seen the hardest and best soldiers brought to their knees, reduced to crumbling, quivering wrecks, in floods of tears. That’s what fear can do to you if you fail to harness it and let it trample you. Today, many of these men are suffering from serious, debilitating mental disorders from which they might never recover. Their marriages have fallen to pieces, they can’t sustain regular employment, and they’re utterly lost in drugs and alcohol. Some are homeless, some enmeshed in a life of street crime. They’ve been destroyed by fear.

Although I was determined not to become one of these men when I served with the military, I could feel the effects of fear creeping up on me. When I was in the Special Forces, I’d be dropped off in a war zone in some grim and dusty back-end of the planet, and then for six interminable months it would feel as if I were utterly trapped in this enormous bubble of constant, crushing dread. As soon as I left the theatre of operations and my plane touched down in the UK, the bubble would suddenly burst and life would be great again. But when I began counting down the days until the start of the next tour, I started to experience that gut-wrenching feeling all over again. I didn’t want to go back.

For a while I couldn’t work it out. What was wrong with me? What was that heavy, greasy sensation in the pit of my stomach? I loved my job. So why was I feeling that I didn’t want to go back? I had to be brutally honest with myself. The truth was, I was shit scared. Fear had got a grip of me, just like it had got a grip of thousands of brave and capable men before me.

I didn’t know what to do. How could I ever solve the problem of experiencing intense fear on the battlefield? Of course you’re going to be scared when the air is filled with bullets and the ground is filled with IEDs (improvised explosive devices). Surely this was an impossible task? It then occurred to me that if I couldn’t get rid of fear completely, perhaps I could break it down into smaller packets so that it was a little less all-consuming and relentless. So that’s what I did. After giving it some thought, I realised I needed to adopt a coldly rational view of why I was feeling scared and, even more importantly, when I was feeling scared. Why, for example, was I experiencing such dread two weeks before my deployment, when I was still in the safety and joyfulness of my family home? There was nothing to be scared of there. Nothing whatsoever.

And while I was at it, what was the point of being scared when I landed in whatever unnamed conflict zone to which I happened to have been assigned? We were usually stationed in a secure area inside some form of military base. If you actually thought about it, a military base was one of the safest places on the planet, teeming with highly trained men and women, and guarded with the latest military equipment. There was not much, realistically, to be scared about there. Statistically, you were probably more likely to be walking around with an undiagnosed tumour in your body than you were to be killed by the enemy in a place like that, and nobody on the base was running around all day fretting about whether or not they had cancer.

And what about when I was on an actual operation? When I was dropped off behind enemy lines, I didn’t need to be in that bubble of fear. No bullets would be flying. We’d land in a safe space and be entirely incognito. The lads would be with me. When I was approaching the target location, where we’d often be attempting the hard arrest of a terrorist leader, there was no point being in that bubble of fear either. That would be a lengthy walk in complete silence through the darkness – several hours of relative safety. It was only when I actually got onto target, where the bad guys were, that it was really appropriate to feel scared.

From my very next mission onwards I put this coldly rational approach to fear into practice. I tried to make it a cast-iron rule. The proper time to feel scared was when we were inside the process of an active operation. At all other times, I told myself, the fear was irrational. Pointless. So shake it off.

And it worked. Kind of. As soon as we hit the target, the fear would take me. I’d be inside that bubble, gripped with absolutely gut-wrenching dread until we were done. After the completion of the mission I’d run on to the helicopter, and the moment the door had closed and we’d lifted off to a safe altitude I’d be out of the bubble. Happy. Elated. Delirious. Thank God. And I wouldn’t allow myself to feel fear again until the next mission was in play.

But after a couple of months of this the old feeling started to return. As much as I genuinely loved being a Special Forces operator, the grinding, bubbling sensation in the pit of my stomach when I thought about getting on that helicopter came back. Brutal honesty. I was shit scared. Again. Although I’d managed to break the fear down into a much smaller and more rational chunk, I realised that even that was too much for me to handle. An active operation could last many hours – and sometimes stretch into days, depending on how bad the situation became. That was too long to spend inside a fear bubble.

The next step was obvious. I’d have to break it down into even smaller packets. From now on, I told myself, I would be absolutely rational and clear-headed about when it was appropriate to feel fear and when it wasn’t. Even when I was standing right in front of the terrorist’s compound, I decided, I didn’t need to be in that bubble. After all, he was probably fast asleep with his thumb in his mouth and his dick in his hand, and his guards would most likely be completely unaware of our presence. So what was the point of feeling fear? There was nothing to be scared of. I was a ghost, at that moment, as invisible as a subtle change in the breeze. It was only when I was under a direct threat – when I knew, for example, that there was a sentry position or an armed guard behind a corner or a door that I was stacked right up against – that it was actually appropriate to feel fear. That precise moment before the bullets flew. That was the time.

It was on the next operation that I had my huge breakthrough. We’d entered a terrorist compound at just gone four in the morning. I knew there was an armed combatant just around the corner of a mud and rock wall that I was approaching. I could see the smoke from his cigarette and the black steel barrel-tip of his AK47 in the green static blur of my night-vision goggles. I looked at the corner and told myself, ‘That is where the fear bubble is.’ And then I did something new. I visualised the bubble. I could actually see the fear, right there at the place where my life would be in danger. Not where I was standing, ten metres away from it, but over there where the threat actually, truly was. And nor was that fear happening right now, at this moment. I would feel it a few seconds later, when I made the conscious decision to go over there and step into the bubble.

That visualisation changed everything. Fear was no longer a vague, fuzzy concept with the power to utterly overwhelm me like an endless storm. Fear was a place. And fear was a time. That place was not here. And that time was not now. It was over there. I could see it. Shimmering and glinting and throbbing and grinding, and waiting patiently for my arrival.

Now all I had to do was step into it. I girded myself with a deep breath. And then I took a few paces forwards and walked into it. There it was. Fuck. The fear hit me like wave. I was so close to the enemy combatant I could practically smell the stale camel milk on his breath. Now I was in the bubble, I had to act. I made the conscious decision to do what needed to be done.

The moment he hit the dirt, my fear bubble burst. I stepped forward, around the body, as the relief and elation that I was actually still alive ripped through me. Gathering myself together, I saw that I was now in a wider courtyard area. Out of the corner of my eye I glimpsed someone running into a doorway, slamming the door behind him. I felt a sudden surge of fear and then squashed it dead. ‘I’m now in this courtyard alone,’ I thought to myself. ‘There’s no danger in this physical location or at this precise time. I’m good. Right now, in this place, at this moment, I’m safe.’

I looked at the door. Behind it lay the enemy. Behind it lay the danger. I visualised the bubble right outside it. I approached the bubble. I took a deep breath. I stepped into it and felt the wave of dread slam into me. I composed myself. Kicked the door down. Entered. Cleared the room. And I was out of the bubble again. And that’s how the entire operation continued. When the next target was coming up, I visualised the bubble, stepped into it and felt the fear, committed myself to doing what had to be done and acted. Then, with a wave of bodily pleasure, the fear bubble burst. All I had to do then was look for the next one.

THE POWER OF ADRENALINE

That night I managed to break my experiences of fear down into episodes that lasted mere minutes – and sometimes just a few seconds. Whereas I’d once treated entire six-month tours as enormous, life-sapping fear bubbles, I’d now reduced them to manageable packets and made my relationship with fear completely rational and functional. I realised that while it was surely impossible not to feel fear, it was certainly possible to contain it. It was just a case of working out exactly where the fear was in space and time, then visualising it, before making a conscious choice to step into it and – finally – doing what had to be done.

If it was a surprise how effectively this technique enabled me to manage extreme fear, it was an even bigger surprise to find that it actually made what had sometimes been a horrendous experience almost addictively enjoyable. There was no greater feeling than popping one of those bubbles by going out the other side of it. As soon as I did, I’d experience a surge of adrenaline. I’d use the massive buzz that my adrenaline gave me to propel myself from bubble to bubble. Before long I was running around like a lunatic, looking for the next bubble. Soon, rather than dreading the next moment of danger, I actually began craving it.

People often get fear mixed up with its adrenaline-soaked aftermath. It’s important to understand that these are two separate states of mind. It’s not uncommon for individuals to confuse one with the other and conclude that they’ve conquered fear. Instead, adrenaline is a tool. It’s a temporary high that powers you on to the next bubble and the next bubble, providing you with the energy and the confidence to keep on going, and giving you the natural high of the reward when you pop each one.

As that tour of duty continued, I began to work out more and more about the fear bubble technique. The final critical lesson I learned was that I didn’t have to pop every single bubble that I stepped into. Sometimes I’d enter a bubble, feel all those familiar emotions and sensations blasting up through me, then realise that I wasn’t ready for it. It was too much. When operational conditions allowed, I’d step out of the bubble again, take a moment to compose myself and try again. I realised that it was extremely important not to remain in any fear bubble for too long. If I did, those dreadful emotions and sensations would start to drain me. They’d become overwhelming. Then I’d start overthinking my situation and the fear would just grab me and hold me there, frozen to the spot, as all my courage began to weep away. I had to consciously commit to whatever action was necessary to make that bubble pop. If I couldn’t do that, I’d step back out of it. Take a moment. Have another go. Too much still? No problem. Step out of it again. Two or three attempts was usually all it took. Ultimately, no bubble ever proved too difficult for me to burst.

TAKING THE BUBBLE HOME

The fear bubble technique not only got me through that tour, it prevented the feeling of dread I’d always experienced between operations from ever coming back. Now that I had my fear compartmentalised and rationalised, and I’d learned to use the natural power of adrenaline to sail me from bubble to bubble, I began to actively look forward to getting out there. My professional life became all about bursting those bubbles. As it did, my performance on the battlefield sky-rocketed. I became a better operator than I’d ever dreamed possible.

And then I returned home. By the time I left the Special Forces, the fear bubble technique had become something that I’d do almost subconsciously. It was just how I handled myself and the various challenges that life threw up. I never considered that it would be transferable to other people until one day I received a message from a sixteen-year-old boy called Lucas who was doing his GCSEs.

After the first series of SAS: Who Dares Wins was broadcast, it became normal for me to receive hundreds of messages every week, many of them from young men with various questions about mindset. Often they wanted to join the military or were simply looking for advice on how to cope with certain difficult situations they had coming up. Sadly, I’m only able to respond to a small fraction of these appeals for help. But Lucas sent me a message via social media that I couldn’t ignore.

‘I just don’t want to be on this planet any more,’ he wrote.

‘What’s wrong?’ I replied.

‘I’ve got my GCSEs coming up. I’m stressing out. I’m better off not being here. I can’t deal with it.’

‘Where are you?’

‘I’m at home.’

‘If you’re at home, why are you in that bubble of fear? If you want to get up and have a can of Coke and talk to your parents, you can do that. At this place and time you’re in control. You don’t need to be in that bubble now. Don’t put that pressure on yourself. Even the day of your exams, when you’re on your way to school, you don’t need to be in that bubble. Even when you open the classroom door and you sit down with the exam paper in front of you, you don’t need to be in that bubble. The moment control gets taken away from you and the clock starts ticking, that’s when you need to get in the bubble. Attack Question 1 with a bubble. Once you’re done with that, come out of it, enjoy the adrenaline, compose yourself, and attack Question 2 with a fresh bubble.’

After I’d properly laid out my own method for dealing with fearful situations, he asked me, ‘But why don’t I just stay in that bubble for all fifty questions?’

‘Because you’ll be in it for too long,’ I explained. ‘What happens if you only know 50 per cent of Question 1? All you’re going to do is drag that bubble over to Question 2 and then it’s going to negatively affect your performance on that question. And what if you don’t know Question 2? The fear will build and build. The negativity will build and build. I guarantee you won’t get to Question 10 without your mind starting to frazzle and you losing the plot.’

A couple of weeks later Lucas got back in touch. He had tried my fear bubble technique. And he’d nailed his exam. But it was what he told me afterwards that really got me excited. He said, ‘Ant, I loved going from bubble to bubble. It actually made me enjoy the exam.’

I couldn’t believe what I was reading. I thought, ‘So did I! I used to run around the battlefield looking for the next bubble to get into.’ Not only that, but Lucas’s performance was dramatically improved by his use of the technique. He reported that his time appreciation was much better and that he actually finished the exam ten minutes early. He came out of his final bubble, looked around and saw that everyone else was still heads down and deep in it.

Hearing all this from Lucas was simply incredible. I never dreamed that this little hack that I’d worked out years previously on a foreign battlefield as a terrified soldier engaging in brutal firefight after brutal firefight could possibly transfer to a GSCE exam hall in Bolton. It was only then that it occurred to me that the technique might have the power to transform other people’s lives, just as it had transformed my own.

Eagle-eyed fans of SAS: Who Dares Wins might have seen its powerful effects in a famous scene from Series 2. After my experience with Lucas, I thought I’d see if the technique could help the recruits get through some of the tough challenges we throw at them. One capable young contestant called Moses Adeyemi confessed that he was scared of heights and water. Unfortunately for Moses, heights and water were pretty much all we had planned for him in that series. One morning we brought the contestants to a large river into which they’d have to perform a backwards dive from a high platform that we’d erected on top of a shipping container. The moment Moses saw what we had in store for him he began shaking like a leaf.

What the producers of the programme don’t have time to show is that, as well as bawling at the contestants and pushing them and punishing them, we also mentor them. When I saw the state that Moses was whipping himself into, I decided to take him off for a couple of minutes and explain the fear bubble technique to him.

‘Why are you shaking now?’ I asked him. ‘You’re not in any danger whatsoever. The bubble is on the end of that platform. It’s at a place and a time that is not here and is not now. So fucking calm down.’

As I was speaking, Moses was so busy shaking that I thought it was all going completely over his head. But when he walked along the platform a few minutes later, he did so with utter confidence, as if he owned the bloody thing. I watched him get to the very edge, turn around and wobble. That’s when I knew he’d grasped it. He was in the bubble. The fear was hitting him.

‘You’ve got this,’ I told him.

He tapped his chest three times and muttered something to himself. In that moment I could see that he’d committed. There was no going back now.