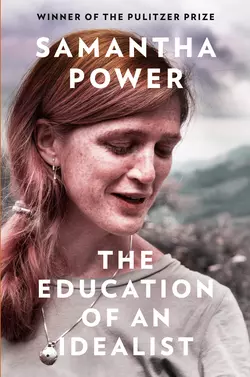

The Education of an Idealist

Samantha Power

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Политология

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 2049.57 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: THE INTERNATIONAL BESTSELLER ‘Samantha Power is a Pulitzer winner, an incredible writer, and a great friend. Her memoir grapples with the balance between idealism, pragmatism, advocacy, and governancy. It’s a must read for anyone who cares about our role in a changing world. ’ Barack Obama What can one person do? At a time of division and upheaval, Samantha Power offers an urgent response to this question – and calls for a clearer eye, a kinder heart, and a more open and civil hand in our politics and daily lives. The Education of an Idealist combines gripping storytelling, vivid character portraits and deep political insight, tracing Power’s journey from Irish immigrant to war correspondent and presidential Cabinet official. In 2005, her critiques of US foreign policy caught the eye of newly elected Senator Barack Obama, who invited her to work with him on Capitol Hill and then on his presidential campaign. After Obama was elected president, Power went from being an activist outsider to a government insider, navigating the halls of power while trying to put her ideals into practice. She served for four years as Obama’s human rights adviser, and in 2013 took one of the world’s most powerful diplomatic positions, becoming the youngest ever US Ambassador to the United Nations. A Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, Power transports us from her early years in Dublin to the streets of war-torn Bosnia into the White House Situation Room and the arena of high-stakes diplomacy. The Education of an Idealist lays bare the searing battles and defining moments of her life and shows how she juggled the demands of a 24/7 national security job with the challenge of raising two young children. Along the way, she illuminates the intricacies of politics and geopolitics, and reminds that in the face of great challenges there is always something each of us can do to advance the cause of human dignity. Honest, inspiring and evocatively written, Power’s memoir is an unforgettable account of the world-changing power of idealism – and of one person’s fierce determination to make a difference.