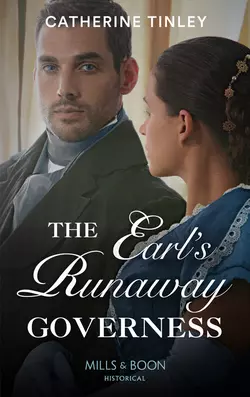

The Earl′s Runaway Governess

The Earl's Runaway Governess

Catherine Tinley

Who knew living with an Earl… …would lead to such temptation? Marianne Grant’s new identity as a governess is meant to keep her safe. But then she meets her new employer, Ash, Earl of Kingswood, and she immediately knows his handsome good looks are a danger of their own! Brusque on first meeting, Ash quickly shows his compassionate side. Yet Marianne doesn’t dare reveal the truth! Unless Ash really could be the safe haven she’s been looking for…

Who knew living with an earl...

...would lead to such temptation?

Marianne Grant’s new identity as a governess is meant to keep her safe. But then she meets her new employer, Ash, Earl of Kingswood, and she immediately knows his handsome good looks are a danger of their own! Brusque on first meeting, Ash quickly shows his compassionate side. Yet Marianne doesn’t dare reveal the truth! Unless Ash really could be the safe haven she’s been looking for...

CATHERINE TINLEY has loved reading and writing since childhood, and has a particular fondness for love, romance and happy endings. She lives in Ireland with her husband, children, dog and kitten, and can be reached at catherinetinley.com (http://www.catherinetinley.com), as well as through Facebook and @CatherineTinley (http://www.@CatherineTinley) on Twitter.

Also by Catherine Tinley (#u1c8cfdd4-a808-5734-8021-39de660cecd1)

The Chadcombe Marriages miniseries

Waltzing with the Earl

The Captain’s Disgraced Lady

The Makings of a Lady

Discover more at millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk).

The Earl’s Runaway Governess

Catherine Tinley

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

ISBN: 978-1-474-08889-3

THE EARL’S RUNAWAY GOVERNESS

© 2019 Catherine Tinley

Published in Great Britain 2019

by Mills & Boon, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London, SE1 9GF

All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition is published by arrangement with Harlequin Books S.A.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, locations and incidents are purely fictional and bear no relationship to any real life individuals, living or dead, or to any actual places, business establishments, locations, events or incidents. Any resemblance is entirely coincidental.

By payment of the required fees, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right and licence to download and install this e-book on your personal computer, tablet computer, smart phone or other electronic reading device only (each a “Licensed Device”) and to access, display and read the text of this e-book on-screen on your Licensed Device. Except to the extent any of these acts shall be permitted pursuant to any mandatory provision of applicable law but no further, no part of this e-book or its text or images may be reproduced, transmitted, distributed, translated, converted or adapted for use on another file format, communicated to the public, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of publisher.

® and ™ are trademarks owned and used by the trademark owner and/or its licensee. Trademarks marked with ® are registered with the United Kingdom Patent Office and/or the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market and in other countries.

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

To all my women friends—colleagues and school friends, college and GAA pals. And to the activists, campaigners and supporters in my life.

You are my sister writers, maternity co-campaigners, repealers and WHO Code supporters.

I feel your support in Women Aloud, the Unlaced Harpies, branch and regional volunteers, conference organisers and maternal mental health champions.

I salute you all.

Contents

Cover (#uff94b676-e532-53d8-8350-78eb8152a430)

Back Cover Text (#u606d205a-625e-5f89-885c-6b0576c1c67e)

About the Author (#u9d1eeadf-cdbe-5238-9a95-6f17e86cd0e2)

Booklist (#uabe87ebc-a1b9-5817-851a-54abe488bac8)

Title Page (#ufe4d048a-e041-5a96-9d76-47309ae033af)

Copyright (#u8868f32d-42fd-5bdc-8626-b2b8586dc8b8)

Dedication (#u4c8b2feb-cdb3-5f39-86d6-31805d6870e3)

Chapter One (#u979ec9f9-006a-4f96-a303-0c4645dfb899)

Chapter Two (#u704a666c-235a-57ff-ae79-33ac6b0e3c2a)

Chapter Three (#uac7b6a59-16f7-51e2-804a-d4b977fbada7)

Chapter Four (#u6a9f3a7b-840b-51da-af4d-84c7c633d14c)

Chapter Five (#ud3368803-cbf9-55e3-88e6-01d2817d03a4)

Chapter Six (#u6ea49bd1-80b0-5bb7-ae9f-7060bc8c80b0)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#u1c8cfdd4-a808-5734-8021-39de660cecd1)

Cambridgeshire, England, January 1810

Marianne tiptoed along the landing towards the servants’ staircase as quietly as she could manage. How different everything looked at night! A sliver of silver moonlight from the only window pierced the curtains, pointing at her. Look! it seemed to say. She is trying to escape!

Her skirts whispered as she moved through the darkness and her cloak billowed behind her like a black cloud. The creak of a floorboard under her feet sounded unnaturally loud, and she had to be careful not to allow her bandboxes to crash against the walls or the furniture. Shadows, unfamiliar and darkly threatening, loomed all around her, growing and shrinking ominously as she passed, her small candle gripped tightly in her right hand.

Downstairs a window rattled in a sudden gust of wind, and in the distance a vixen called mournfully. The candle flickered briefly as she reached the end of the landing, sending shadows scuttling and then reforming all around her.

She paused, listening for any sound, any indication that someone might have heard her.

Nothing.

Her heart was pounding—so much so that it was hard to hear anything above the din of her own blood rushing rhythmically through her body. Her mouth was dry and her palms sticky with fear. But she must not tarry! The longer she delayed, the greater the chance of being discovered.

Raising her candle, she carefully lifted the latch on the door to the back staircase. It gave way with a complaining click and Marianne bit her lip. She moved inside in a swish of silk and closed the door behind her.

She released her breath. Her first task was accomplished safely. Now for the next part.

She stepped down the stone stairs, her stout walking boots making a clatter that sounded thunderous to her ears. But with a closed door behind her hopefully it would not be loud enough to awaken anyone.

Reaching the bottom, she scuttled along the narrow passageway until she reached the chamber that the housekeeper shared with her daughter. The door was ajar, as arranged, and as she reached it Mrs Bailey opened it wide and bustled her inside, closing it securely behind her.

‘Oh, Miss Marianne! I never thought to see this day!’ Jane, the housekeeper’s daughter—Marianne’s personal maid—was sniffling into a handkerchief.

‘Hush now, Jane!’ Mrs Bailey admonished her daughter, though she herself also looked distressed.

Marianne set the candle down and touched the girl’s hand to soften her mother’s words. ‘We talked about this. You know it is for the best, Jane.’

They spoke in whispers, conscious that the housemaids were asleep in the chambers on either side. ‘But surely I should at least come with you?’ Jane protested.

Moved, Marianne enveloped her in a brief hug. ‘I love it that you would be willing to do so, but we all know there is no sense in it. Your place is here with your mother.’

Mrs Bailey, despite her stoicism, wiped away a tear. ‘Your own poor mother would break her heart if she knew you were running away from home, miss!’

Marianne felt the familiar pain stab through her. Mama and Papa had died over six months ago, yet she felt their absence still. Every waking moment.

‘Mama would want me to be safe, and I am no longer safe here.’ Even talking about it caused a wave of fear to flood through her.

‘I know, Miss Grant. It is best that you go.’ Mrs Bailey shook her head grimly. ‘Now, what have you packed?’

Marianne indicated the bandboxes in her left hand. ‘I fitted in as much as I could. My other black dress, two clean shifts, slippers, my reticule and my jean boots. A book. And Mama’s jewels.’ She lifted her chin. ‘I refuse to leave them here for him!’

‘They belong to you, miss. That was clear from the will, so they say. And when your parents made Master Henry your guardian they believed it was for the best.’

‘I know.’

Mama and Papa had refused to accept the truth—that Henry had no kindness in him, no sense of right and wrong. They would never knowingly have placed her in danger.

‘He is your brother, after all.’

‘My stepbrother.’ That had never seemed so important. ‘You know my real father died when I was a baby.’

Mrs Bailey acknowledged this with a nod. ‘The master and mistress were good for each other. Both widowed, both with a child to rear. It seemed a good marriage.’ She hesitated for a moment. ‘I have often wondered,’ she confessed, ‘if losing his own mother so young changed Master Henry.’

Marianne had no time to consider this. ‘He is who he is. I only know that I must escape before he...harms me.’

‘Of course you must.’

Unspoken between them was the fact that Mrs Bailey had rescued Marianne when Henry had cornered her a few hours earlier, in her chamber. He had been drunk, of course, but his unnatural interest in his stepsister was of long standing.

Marianne had been keenly aware of how the servants had kept her safe these past months, ensuring that Henry had no opportunity to be alone with her. Until today nothing had ever been said, but the butler had instructed the second footman to fit a new lock to Marianne’s chamber door just last week. Behind the locked door she had been able to relax a little.

Until tonight, when he had lain in wait for her within her own chamber.

Believing Henry to be still drinking with his raucous friends, in what had been her mother’s favourite drawing room, Marianne had hurried upstairs to seek the sanctuary of her room. Sighing with relief, she had closed her door and turned the key, only to hear him murmur silkily, ‘Good evening, my dear Marianne.’

She had whirled round to see him lying on her bed, his cravat loosened and a predatory look in his eye. Her mind had frozen for a second, and then wordlessly she had turned back to the door and unlocked it.

Before she had been able to open it properly he had been upon her, grabbing her from behind and muttering unspeakable things in her ear. Her shriek had not been loud enough to be heard in other parts of the house, but luckily Mrs Bailey had been nearby and had bravely intervened.

‘Oh, sir!’ she had said, bustling into the room. Pretending not to notice Marianne’s distress, or the position of Henry’s hands, she had gone on, with mock distress, ‘One of your friends has been violently sick and they are all requesting your presence.’

‘Damn and blast it!’

Henry had released her and stomped off, but not without a last look at Marianne. I shall win, it had promised. You cannot escape me for ever.

Mrs Bailey had stayed to soothe and calm Marianne. ‘Oh, my poor dear girl! That he would do such a thing!’

‘Please go—do not draw his anger,’ Marianne had urged, though her whole body had been shaking. ‘If the mess is not cleaned up quickly who knows what he will do!’

‘The footmen are already cleaning it,’ the housekeeper had reassured her. ‘My maids will not serve them in the evenings.’

They both knew why. The maids had also experienced the licentious behaviour of Henry and his drunken friends.

During the day their behaviour was rowdy, but they were usually reasonably restrained. In the evenings, however, fuelled by port and brandy, they became increasingly vulgar, ribald and uninhibited. And the entire household suffered as a result.

Marianne, pleading the conventions of mourning, had always avoided the ordeal of eating with them, choosing instead to consume a simple dinner each evening in the smaller dining room. She barely knew who was here this time—apart from his two closest friends, Henry’s guests were different for each house party.

Oh, their hairstyles and clothes were more or less the same—they were all ‘men of fashion,’ who spent their wealth on coats by Weston or Stultz, boots by Hoby and waistcoats by whichever master tailor was in fashion at that precise moment. Their behaviour, too, was more or less the same—arrogance born of entitlement and the belief that they could do whatever they wished, particularly to defenceless women. Including, it seemed, Marianne herself.

Knowing he would be criticised by society if he continued his customary carousing in public too soon after the tragic deaths of his father and stepmother, Henry had told Marianne that he had hit on the ‘genius notion’ of inviting all his friends for a series of house parties. Every few weeks, her home had been invaded by large groups of young men. They stayed for five or six nights each time and were up for every kind of lark.

The housemaids had learned to be wary of them, and Mrs Bailey had hired three older women to serve them, keeping Jane and the other young housemaids as safe as she could. Some of the servants—maids and footmen—had left already, to take up positions elsewhere. Very few long-serving staff remained—chief among them Mrs Bailey and Jane. Mrs Bailey had expressed the hope that once their year of mourning was completed, in March, Henry would return to his preference of living in the capital, and they would again have peace.

His attempt to assault Marianne herself this evening had changed everything.

While the behaviour of Henry and his friends had been gradually worsening, last night’s incident had been different. It had not been simply a lewd comment or a clumsy attempt to embrace a chambermaid. Henry had dark intentions, and Marianne now knew for sure that she was in danger. Running away was her only option. Mrs Bailey agreed.

‘Here is the direction for the registry I told you about.’ The housekeeper pressed a note into Marianne’s hand. ‘I have heard that they will place people who come without references. Lord knows we may need it ourselves before long.’

‘Thank you.’ Marianne secreted the note in her pocket, where her meagre purse also rested.

Although she had never wanted for food, new clothes or trinkets, and had a generous allowance, nevertheless she did not normally need access to much cash. This was an unusual and urgent situation, so she would have to make do with the pin money she’d had in her room. She drew her cloak around her and picked up her bandboxes again, this time hefting one in each hand.

‘Mr Harris will meet you at the gates.’ The housekeeper named one of the tenant farmers. ‘He will take you in his cart as far as the Hawk and Hound, where you can catch the stage at five in the morning. It comes through Cambridge from Ely and you will be in London by nightfall. I’ve also written down the names of two respectable inns. Hopefully one of them will have a room free. Stay there until you find a situation as a governess.’ She gripped Marianne’s hand. ‘I am so sorry that you have to leave your home, miss. Please take care of yourself.’

‘I will.’

Marianne nodded confidently, as if she knew what she was doing. But as she walked up the drive in darkness, away from the only home she had ever known, her heart sank.

How on earth am I to manage? she wondered. For I have never before had to take care of myself!

Grimly, she considered her situation. She had been gently reared, and could play the harp and sing, sketch reasonably well and set a neat stitch. She had been bookish and adept at her lessons when she was younger.

But she had no idea how to buy a ticket for the stagecoach, or wash clothes, or manage money.

She had also never been in a public place unaccompanied before. Mama had always been with her, or her governess, or occasionally a personal maid. But those days were gone. She must learn to dress by herself now, and mend her own clothing, and dress her own hair. And somehow she must keep herself safe in the hell that was London.

London! She knew little of the capital—had never visited the place. But in her mind it was associated with all kinds of vice. London was where Henry lived. London was where his arrogant, lecherous friends lived. London, she had come to understand, was a place overrun with wicked young men, drinking and vomiting and carousing their way through the streets, gambling dens and gin salons.

Mama and Papa had hated to visit the place, and had always exclaimed with relief when they’d returned home to country air and plain cooking. They had never taken her with them, leaving her safely in the care of her nurse or governess, and Marianne had never objected. Even as a child she had understood that London was a Bad Place, and she had been puzzled by Henry’s excitement at going there.

When he had become old enough he had insisted on having lodgings of his own in the city, and with reluctance Papa had given in to his son’s demands. Henry had moved to London, rarely coming home to visit, and everyone at home had breathed a little easier.

And now here she was, leaving home in the middle of a cold January night, with little money, no chaperone, and no notion of how she was going to manage. And she was choosing to go to London, of all places.

She stifled a hysterical giggle. Strangely, the absurdity of it all had cheered her up. That she could laugh at such a moment!

She lifted her chin, squared her shoulders, and trudged on.

Netherton, Bedfordshire

William Ashington, known to his friends as Ash, rubbed his hands together to keep away the cold. The vicar’s words washed over him. ‘For as much as it hath pleased Almighty God in his great mercy to take unto himself the soul of our dear brother here departed: we therefore commit his body to the ground—earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust...’

Ash threw a handful of earth onto John’s coffin, feeling again the loss of the man who had been much more to him than a cousin. In truth John had been like a brother to him—at least until that summer when they had both turned eighteen. In recent years they had recovered something of an awkward friendship, but it had never been the same.

How could it?

He turned away as the service ended, accepting a few handshakes and murmuring appropriate responses to the expressions of sorrow being offered.

‘My Lord?’ It was the vicar. Ash started, realising the man was addressing him. Strange to think that because of John’s death he was now not simply Mr Ashington but the Earl of Kingswood.

‘Yes?’

The vicar shook his hand and thanked him for attending the service. ‘A funeral is always a sad occasion, but laying to rest such a young man is doubly sorrowful. Why, he was not much more than two and thirty!’

I know, thought Ash. For John and I are—were—almost the same age.

‘And to think of his widow and daughter, now left alone in the world...’ The vicar sighed, then looked at Ash intently. ‘Lord Kingswood—er...the previous Lord Kingswood spoke about them often to me in his final weeks.’

‘Indeed.’ The last person Ash wished to think about was John’s widow. Thank goodness women did not attend funerals.

‘He also spoke about you.’ The vicar’s warm brown eyes bored into Ash’s. ‘I think he regretted the distance between you.’

Ash was feeling extremely uncomfortable. He was unaccustomed to discussing his personal affairs with someone he had just met. In truth, he was unaccustomed to discussing his personal affairs with anyone. He preferred it that way.

Adopting his usual defence in such moments, he maintained an even expression and said nothing.

The vicar made a few more general comments and Ash listened politely. He thanked the man and turned away to where his coachman, Tully, waited with the carriage. If he left now he could be back in London by tonight.

‘Er...’

The vicar. Again.

‘Yes?’ Ash’s patience was beginning to wear thin, but he forced himself to maintain a courteous expression.

‘I was asked to pass this to you.’ He offered Ash a sealed note.

Ash frowned but took the paper. Opening it, he ran his eyes over the contents.

‘Confound it!’ he snapped, causing the vicar to raise an eyebrow. ‘I am requested to go to the house after the funeral. By the family lawyer.’

The vicar looked bewildered at his reaction to what must seem a perfectly reasonable request. They were literally standing together at the Fourth Earl of Kingswood’s funeral, and Ash was now the Fifth Earl.

But he had never expected to accede to the title.

Why, John had been only thirty-two, with plenty of time to sire a son with Fanny. Everyone—including Ash—had assumed that John would eventually have sons, and that he—Ash—would never have to worry about the responsibilities John had carried for so long.

Ash debated it in his mind. Could he ignore the note and leave immediately for London, as planned? He could ask the lawyer to see him there. No. It would look churlish and impolite. Damn. He would have to comply as a courtesy. Which meant possibly seeing her again.

Fanny. John’s wife—John’s widow, he corrected himself. After all these years of successfully avoiding her.

Placing his hat firmly on his head, he bade farewell to the vicar and made for his carriage. If he must face this ordeal, better to get it over with.

Chapter Two (#u1c8cfdd4-a808-5734-8021-39de660cecd1)

Marianne reminded herself to breathe. Her shoulders were tense and she could feel fear prick her spine. She had paid the fee and entered her name into the registry book at the office recommended by Mrs Bailey, and now she waited.

Well, she acknowledged, not her actual name. Her made-up name.

She had decided during the long journey to London that she must not go by her usual name, for fear Henry might look for her. She would use her father’s surname—her real father—as it would give her comfort, and she was confident Henry would not remember or recognise it.

After being known as Marianne Grant for most of her twenty years, she would now go back to the surname she had been given at birth—Bolton. Charles Bolton had given her her dark brown eyes, her dark hair and, according to Mama, her placid nature. The Grants were altogether more fiery.

She was seated in an austere room with a dozen other would-be servants, all patiently awaiting their turn to be called. Among the would-be grooms, scullery maids and footmen she had espied two other young ladies, respectably dressed, who might also be seeking employment as governesses. She had exchanged polite smiles with both of them, but no one had initiated conversation.

It was greatly worrying that on a random Tuesday there were three young ladies of similar social standing all seeking positions at the same time.

The door to the inner office opened and everyone looked up. The young man who had been called a few moments earlier now emerged. His demeanour gave no sign as to whether he had been offered a position or not, but he kept his head down as he left.

I wonder, thought Marianne, if he is a footman?

‘Miss Bolton? Miss Anne Bolton?’

With a start, Marianne realised that it was her turn. The lady in charge—the one who had been calling people in for the past hour—was standing in the doorway. Anne Bolton was, of course, the false name Marianne had written in the registry book, and her ears had not responded when the name had been called.

Blushing, she stood. ‘I am Miss Bolton.’

My first lie. Or is it?

The lady eyed her assessingly. ‘Come with me.’

Trying to maintain a dignified expression, and hoping that her shaking hands were not obvious, Marianne followed her into the inner chamber and closed the door.

‘Please sit, Miss Bolton.’

Marianne complied, watching as the registry lady took her own seat behind an imposing rosewood desk. So much depended on the next few moments and this woman’s decision!

‘I am Mrs Gray.’

She was a stern-looking lady in her later years, with iron-grey hair, dark skin, piercing dark eyes and deep lines etched into her face. She wore a plain, high-necked gown in sombre grey and no jewellery. Despite this, it was clear that she was a person of authority. It was something about the way she carried herself, how still she was, the way those dark eyes seem to pierce right through Marianne’s flimsy defences.

‘I see that you are seeking a position as a governess,’ she stated, ‘but you have come with no recommendation. Tell me about your situation and why you are here.’

Mrs Gray’s tone was flat, expressionless. Marianne could feel her heart thumping in her chest.

Haltingly, then with increasing fluency, Marianne told the tale she had concocted. Mrs Gray listened impassively, giving no indication whether she believed any of it. Doubt flooded through Marianne. Perhaps she should not have pretended that her father was a lawyer and that he had left her with little money and no connections. What if Mrs Gray asked for some proof? Her heart fluttered as anxiety rose within her.

‘When did your father die?’

‘Six months ago.’ Marianne’s throat tightened as it always did when she thought about Papa.

Mrs Gray’s eyes narrowed. ‘And your mother?’

‘Also dead.’ Marianne swallowed. Her hands clenched into fists as she fought the wave of grief that threatened to overwhelm her.

Mrs Gray’s gaze flicked briefly to Marianne’s hands, then she leaned back slightly in her chair. ‘Tell me about your education, Miss Bolton. What are your talents?’ Mrs Gray spoke bluntly, giving no clue as to whether she would favour Marianne.

Hesitantly, Marianne spoke of drawing and painting, of her musical skills, her ability to sew and to converse in French and Italian—

‘And what do you know of Mathematics, Logic and Latin?’

Marianne blinked. Mrs Gray had asked the question in perfect Italian! ‘I have studied the main disciplines of Mathematics,’ she replied, also in Italian.

Mrs Gray quizzed her on these, then switched to French, followed by Latin, to discuss the finer details of Marianne’s knowledge of Logic, improving texts and the Classics.

Thankfully Marianne’s expensive education had equipped her well. She had been an apt student and had enjoyed her studies. Was that, she wondered, a glimmer of approval in Mrs Gray’s eye?

The woman paused.

Marianne forced herself to sit still. Please, she was thinking, please. If she could not gain a position as a governess she had no idea what she would do. Returning home was not an option. That door was closed in her mind. She had no home. So everything depended on Mrs Gray.

* * *

This house is freezing, thought Ash, stepping towards the fireplace in John’s study. Hopefully he could be on his way quickly—the last thing he needed was a prolonged encounter with the grieving widow.

He paused, holding out his hands to the pathetic fire, but there was little heat to be had. The door opened and closed, sending smoke billowing into the room. Ash coughed and stepped away from the fire.

Have the dashed chimneys ever been cleaned?

He had not been in Ledbury House for many years, but he could not remember it looking so dilapidated.

‘Lord Kingswood, thank you for coming.’ The lawyer, a bespectacled gentleman in his middle years, bowed formally. ‘My name is Richardson.’

Ash nodded his head. ‘I received your note asking me to come to the house after the funeral. I understand you wish to read the will immediately.’

He kept his tone polite, despite his impatience with the entire situation. Every moment he spent here meant a later arrival in London.

‘I am required to outline the extent of your inheritance, plus a number of other matters added by the Fourth Earl to his will.’ The lawyer pushed his spectacles up his nose, where they balanced precariously. He went behind John’s desk and began taking papers out of a small case.

Ash stood there, wishing for nothing more than to leave and never return. Every part of him was fighting the notion that he was now Earl of Kingswood. The last thing he needed was ‘other matters’ complicating his life further.

‘What other matters? And why did John—my cousin—see fit to add to the responsibilities of the Earldom?’

Mr Richardson sniffed. ‘That is not for me to say. My role is simply to see that the requirements of the will are carried out.’ He arranged the papers methodically on John’s desk.

‘I see.’

But he didn’t. Not at all. Why had John added to his burdens, knowing how much he would hate it? Particularly when they had not been intimate friends for fourteen years?

John had settled into life as a country earl, staying in this rundown mausoleum of a house with his wife and daughter and rarely visiting the capital. Ash, on the other hand, barely left London, unless it was to attend a house party. Life in the country was intolerably tedious.

Perhaps, Ash mused, John has left me a memento—something from our childhood or youth.

Still, if he was forced to stay for the reading of the will it meant that he would not be able to avoid running into—

‘Mr Richardson! Thank you so much for being here in our time of need.’

Ash turned to see Fanny glide into the room, followed by a girl who must be her daughter.

Fanny had always known how to make an entrance. Her black gown was of the finest silk, with self-covered buttons and black lace detail at the sleeves. Her blonde hair was artlessly arranged in an elegant style, and her matron’s cap did nothing to dim the beauty of her glorious features. The cornflower-blue eyes, cupid’s bow lips and the angelic dimples that had driven him mad with desire all those years ago were all still there. If anyone could make mourning garb look attractive it was Fanny.

Despite himself he felt a wave of recognition and remembered longing which almost floored him. For a moment he felt eighteen again.

She stopped, as if noticing him for the first time. ‘Why, Ash! I did not know you were here already.’

She was lying. The servants would have told her of his arrival—and the fact that he and the lawyer were in the library for the reading of the will.

He bowed. ‘Hello, Fanny.’ He made no attempt to take her hand. Or kiss it.

‘This is most unexpected,’ she murmured. It was unclear whether she was referring to the immediate reading of the will or to his coming into the title.

‘For me, too.’ Pointedly, he eyed her daughter. ‘And this is—?’

‘My daughter, Cecily.’ The girl, as pretty as her mother—though with John’s hazel eyes—curtseyed politely, then looked quizzically at him.

‘I am an old friend of your father. And I am also his cousin.’

‘We were all friends, Ash.’ Fanny seated herself on a faded sofa and smoothed her skirts, indicating with a gesture that Cecily should sit with her. ‘May I offer you some refreshments? Tea, perhaps?’

‘A brandy would be preferable.’ He would need something stronger than tea if he was to endure the next half-hour.

She pressed her lips together and reached for the bell.

Ash sighed inwardly. Fanny had not changed one iota.

* * *

Mrs Gray had been making notes throughout her quizzing of Marianne, but now she lifted her head to fix Marianne with a steely stare. ‘It is difficult to find a situation for a governess who comes with no reference, no recommendation.’

‘I understand.’ With some difficulty Marianne kept her expression neutral. It would not do to show desperation. ‘But I assure you I will make a good governess. When I lived with my parents I taught our maid to read and to write. I found it enjoyable, and I believe I have an aptitude for it.’

That is mostly true, she thought. I did teach Jane—though the implication that she was our only maid is misleading. Oh, dear—how hard it is to be a liar!

Mrs Gray tapped her finger on the table, considering. ‘There is one possibility. A young girl in need of a governess. Her father died recently, too—indeed, my understanding is that he was to be buried today.’

Marianne felt a pang of sympathy for the unknown girl. She knew exactly how it felt to lose a beloved parent.

Mrs Gray was watching closely, and now she nodded in satisfaction. ‘She lives quietly with her mother in the country.’ She eyed Marianne sharply. ‘You do not mind leaving London and living in some quiet, out-of-the-way place? Will you miss the excitements of the capital?’

Marianne shuddered at the very thought of the ‘excitements’ of London. Since arriving in London last night she had been almost overwhelmed by the noise and the smells and the feeling of danger all around her. It had reinforced her notions of the city, gleaned from second-hand tales of Henry’s activities and from the behaviour of the London bucks he had brought to her home.

‘I have no desire to live in London. I am myself country-bred and will be perfectly content in the country.’

It would also make it harder for Henry to find her. If he even bothered searching for her.

‘I have one further question.’ Mrs Gray eyed her piercingly. ‘Those who come to me for a situation know that I sometimes place those whom other registries will not touch. But I insist on my people being of good character.’

Marianne’s chin went up. No one had ever dared question her character before! ‘I can assure you, Mrs Gray, that my character is blameless.’

‘No need to get hoity-toity with me, Miss—’ she glanced down ‘—Miss Bolton.’

Marianne blushed. Mrs Gray was making her scepticism about the name obvious.

The woman’s dark eyes fixed on Marianne, bored into her. ‘Are you with child?’

Marianne gasped. ‘Of course not! I’ve never—I mean I wouldn’t dream of ever—I mean, no.’ She kept looking at Mrs Gray. ‘It’s impossible.’

‘Very well.’

As if she had not just asked Marianne a perfectly outrageous question, Mrs Gray took a fresh sheet of paper, and began writing.

‘You will receive board and lodging and will be paid a yearly wage and a tea allowance. You will be entitled to two days off per month. Take the Reading stage from the Angel on Thursday and get out at Netherton. I will arrange for someone to meet you there and take you to Ledbury House.’

She looked up.

‘Remember, Lady Kingswood and her daughter, Lady Cecily, are in mourning, so they will live very quietly. I have placed servants and staff there before, who have left because the situation is too remote. I believe it is why Lady Cecily’s last governess left. The child needs someone who is willing to stay for a long time. After losing her father—’

‘I understand.’

Living quietly sounded perfect! Marianne had loved her quiet, easy life with Mama and Papa, visiting neighbours and friends and never aching for the so-called delights of the city.

‘Lady Kingswood had been focused, naturally, on nursing her husband through his last illness, which is why she has entrusted the appointment of a new governess to me.’ Mrs Gray handed her the paper. ‘Do not let me down!’

Marianne assured her that she was to be relied upon, then looked at the document. It gave the address as Ledbury House, Netherton, Berkshire. It also included a summary of Marianne’s terms of employment.

Her hand shook a little as she accepted it. Amid the relief which was coursing through her there was also a sense of unreality. Strange to think that from now on she would no longer be Miss Marianne Grant, a young lady of wealth and status, but instead plain Miss Anne Bolton, governess, orphan, and near-pauper.

She swallowed. The alternative was absolute poverty or—God forbid—returning to Henry. Fear flooded through her at the very thought. She would have to make this work, be careful and, crucially, be effective as a governess. She would also have to learn to respond to the unfamiliar name.

She looked at the page again. The wage she was to be given was shockingly little. It was much less than her allowance—the pin money that she had so carelessly spent each quarter on trinkets, stockings and sweetmeats. She had no idea how to make economies. Now she was expected to make this meagre amount cover all her needs, including her clothes.

She lifted her chin. I can do this! she told herself. I must!

* * *

‘And now to the family bequests.’

Mr Richardson, Ash thought, would have made an excellent torturer. Not content with bringing him into this godforsaken house and forcing him to endure Fanny’s company, he was now reading—very slowly—the entire Last Will and Testament of John Ashington, Fourth Earl Kingswood. Ash had sat impassive as the lawyer had detailed the property that was now his—the main element being this house, with its unswept chimneys. Thankfully, the lawyer was now on to the family section.

Ash took another mouthful of brandy. He would be out of here soon.

Fanny sat up straighter, a decided gleam in her eye. Only the house and gardens were entailed, therefore the rest of the estate would likely be placed in trust for Cecily, perhaps with a sizeable portion for Fanny herself.

He wondered, not for the first time, if Fanny had chosen John because of his title. Had he been the Earl when he and John had both fallen in love with the same girl, would she have chosen him?

Ash forced himself away from cynical thoughts and tried to pay attention to the lawyer.

Mr Richardson read on—and what he said next made Fanny exclaim in surprise. Cecily was to receive only a respectable dowry and John’s mother’s jewellery. So Fanny was to inherit everything?

Ash stole a glance at her. She was quivering in anticipation. Ash averted his eyes.

‘To my dear wife,’ Mr Richardson droned, ‘I leave the Dower House for as long as she shall live there unmarried...’ He went on to specify a financial settlement that was again respectable, though not spectacular.

‘What? What?’ Fanny was not impressed. ‘If he has not left everything to Cecily, or to me, then to whom...?’

She turned accusatory eyes on Ash. ‘You!’

The same realisation was dawning on Ash.

‘The remainder of my estate I leave to my cousin, the Fifth Earl Kingswood, Mr William Albert James Ashington...’

Without missing a beat the lawyer detailed the unentailed lands and property that Ash was to inherit. But there was more.

‘I commend my daughter, Lady Cecily Frances Kingswood, to the guardianship of the Fifth Earl—’

‘What? No!’ Fanny almost shrieked. ‘Mr Richardson, this cannot be true!’

Ash’s blood ran cold as he saw the trap ahead of him. Guardian to a twelve-year-old child? Cutting out the child’s mother? What on earth had John been thinking?

The lawyer paused, coughed, and looked directly at Fanny over his spectacles. Chastised, she subsided, but with a mutinous look. Mr Richardson then returned to the document and read to the end.

John explained in the will that Ash was to link closely with Fanny, so that together they might provide ‘loving firmness’ for Lady Cecily. Loving firmness? What did that even mean?

Ash’s mind was reeling. Why on earth had John done this? Did he not trust Fanny to raise the child properly by herself?

The last thing Ash wanted was to be saddled with responsibility for a child! Fanny could easily have been named as guardian, with Ash and the lawyer as trustees. Indeed, it was normally expected that a child’s mother would automatically be guardian.

The feeling of impatience and mild curiosity that had occupied him when Mr Richardson had begun his recitation had given way to shock and anger, barely contained.

Fanny, of course, then added to Ash’s delight by indulging in a bout of tears. Cecily just looked bewildered. Ash met Mr Richardson’s gaze briefly, sharing a moment of male solidarity, then he closed his eyes and brought his hand to his forehead. Would this nightmare never end?

* * *

Marianne emerged from Mrs Gray’s registry hugely relieved. She glanced at the other two young ladies in the outer office. They were now seated together and had clearly been quietly chatting to each other. They looked at her now with similar expressions—curious, polite, questioning. She was unable to resist sending them what she hoped was an encouraging smile.

She patted her reticule as she stepped into the street, conscious of the paper within. This was her future. Governess to an unknown young lady, recently bereaved and living quietly with her mother. It sounded—actually, it sounded perfect.

For the first time since her decision to run away she felt a glimmer of hope. Perhaps, after all, things would work out. She had a situation and she would have a roof over her head. She would be living quietly in the country, far away from London. As long as Henry did not find her all would be well.

Of course she had no idea whether he was even looking for her. He might be content simply to let her vanish. On the other hand, that last look he had thrown her—one filled with evil intent—haunted her. Henry was entirely capable of ruthlessly, obsessively searching for her simply because she had thwarted his will by escaping.

She shrugged off the fear. There was nothing she could do about it beyond being careful. Besides, so far everything was working out well.

With renewed confidence, she set off for the modest inn where she had stayed last night. On Thursday her new life would properly begin.

* * *

‘You are telling me that there is no way to avoid this?’

‘Lord Kingswood, I simply executed the will. I did not write it.’ Mr Richardson was unperturbed.

Fanny had gone, helped from the room by her daughter. Fanny had been gently weeping, the image of the Wronged Widow. Ash’s hidden sigh of relief when the door had closed behind her had been echoed, he believed, by Mr Richardson. Fanny had not, it seemed, lost the ability to make a scene.

‘You have not answered my question.’

There! The subtlest of gestures, but the lawyer had squirmed a little in his seat.

‘Tell me how I can extricate myself from this and allow Lady Kingswood to raise her own child.’

‘With your permission, Lady Kingswood can of course raise her daughter.’

‘But her having to seek my permission is not right. She is the child’s mother. Why should I be the guardian?’

The lawyer shrugged. ‘Her father must have had his reasons. He did not clarify, and it was not my place to ask such questions.’

Ash decided to try another tack. ‘What of Lady Kingswood’s portion? How can I give my cousin’s widow more than her husband did?’

‘That part of the estate, as you know, is not entailed, which is how the Fourth Earl was at liberty to leave it to you. It is true that you do have the option of selling it or gifting it to someone. However—’ he raised a hand to interrupt Ash’s response ‘—after the death duties have been paid the estate will barely manage to break even. Lord Kingswood had been ill for more than a year, as you may be aware.’

‘No. I was not aware.’ Guilt stabbed through him. Damn it! Why had he not known about John’s illness?

‘During that time Lord Kingswood’s investments suffered from a lack of attention, as did the estate. His steward was very elderly—he predeceased Lord Kingswood by only a few weeks—and the burden of management fell on the shoulders of Lady Kingswood. As...er...she had no previous knowledge or background in such matters...’ His voice tailed away.

‘But nor do I!’ Ash ran his hand through his thick dark hair in frustration. ‘If the estate has suffered under Lady Kingswood’s stewardship, then how can I, equally inexperienced, be expected to do better?’

Mr Richardson eyed him calmly.

‘Well?’

‘I am afraid I have no answer to that question. What I do know is that if things are left to Lady Kingswood to manage...’ Again his voice tailed off.

Ash reflected on Lady Kingswood. The young Fanny he remembered had been a beauty, a lively dancer and a witty conversationalist. He had no idea about the woman she had become.

‘Are you suggesting that Lady Kingswood is incapable of managing?’

‘I could not possibly comment.’

‘Damn it!’ Ash slammed his hand down on John’s desk. He was trapped. A title, financial responsibilities, and now this. A twelve-year-old child to raise and a large estate to manage.

‘Quite.’ The lawyer indicated three large chests in the corner. ‘Lady Kingswood informs me that documents relating to the estate and all of Lord Kingswood’s business affairs are contained in these chests.’

Ash opened the nearest box. It was full to bursting with papers, haphazardly stuffed into the chest. It would take at least a week to sort this box alone.

‘Right. I see. Right.’

His mind was working furiously. This was going to take weeks to sort out. Weeks even to discover the extent of the commitment he had been left with. And his life was already full—friends to meet, parties to attend, an appointment to look at a new horse...

He came to a decision. ‘I shall go to London now, as planned, and then return on Thursday, once I have dealt with my most pressing appointments.’

Inside, rage threatened to overpower him. Why have I been given this burden? Damn it, John! Why did you have to die?

Chapter Three (#u1c8cfdd4-a808-5734-8021-39de660cecd1)

The inn at Netherton was similar in some ways to the Hawk and Hound. There was a stone archway off to one side, and Marianne had barely a moment to register the swinging metal sign before the coach swung into the yard.

See? Marianne told herself. It is just an inn. The people here are no different from the people at home. I can do this.

It was a refrain she had repeated numerous times in the few days since she had slipped away from the only home she could remember. Today she had survived the indignity of travelling on the public mail coach for only the second time in her life, sandwiched between a buxom farmer’s wife and a youth travelling to visit his relations in Reading. The farmer’s wife had talked incessantly, which had been both vexing and a relief, since no one could ask her any questions.

Grateful that the jolting coach was finally arrived at Netherton, Marianne descended, and pointed out her bandboxes to the coachman. He untied them from the top of the coach and passed them down to her, then he jumped down again, making for the warmth of the inn and its refreshments.

Marianne looked around the yard. The only other vehicle was a dashing high-perch phaeton, painted in an elegant shade of green, with green and black wheels. She had seen carriages like it before. They were all the crack among the London sporting gentlemen. Henry, of course, owned one—though his was a little smaller and painted red.

So where was the cart or the gig that would convey her to Ledbury House? Mrs Gray had said only that she would inform the family of her arrival. She had no idea who would be meeting her.

The other passengers had also dismounted and were going inside. Those who were travelling on would have a few moments here to relieve themselves, or quickly buy refreshments from the landlord.

Hesitantly, Marianne followed them into the inn.

The interior was dark, cosy and well-maintained. A fire burned in the grate, for the January day was chilly.

Marianne made her way towards the wooden counter at the far end of the room, where a woman who must be the landlady was busy pouring ale. As she walked Marianne found herself warily assessing the strangers in the room. Since the day and the hour she had left home she had not felt truly safe for even a minute. She had no experience with which to assess where danger might lurk, so found herself constantly on edge.

Her fellow passengers were already seating themselves in various parts of the taproom, and there were also two men who looked as if they might be farmers, each with a mug of beer in front of him.

Then she saw him. Her heart briefly thumped furiously in her chest and the hairs at the back of her neck stood to attention.

He was seated with his back to her, at the table closest to the counter. She could see his dark hair, swept forward in fashionable style. He wore a driving cloak with numerous capes. She could also see long legs encased in tight-fitting pantaloons and gleaming black boots. He looked like any one of a dozen London bucks.

Except this time, she reminded herself, you have no reason to fear him.

She kept walking, soothing herself with calm thoughts. As she reached his table she turned her head, compelled to confirm that it was no one she knew.

This man was a few years older than Henry—perhaps in his late twenties or early thirties. His hair was similar—thick, dark and luxuriant. But the face was totally different. This man was handsome—or at least he would be if he were not scowling so fiercely. His strong bones and lean features contrasted with Henry’s slight pudginess and rather weak jawline. And now that she could see all of him she realised that his body shape was totally different from Henry’s. He was lean and muscular, with no sign of a paunch. His clothing was similar to that favoured by Henry—and indeed by all the young bucks of London. But there the resemblance ended.

Sensing her standing there, he looked up from his mug and their eyes met. Stormy blue bored into her and Marianne felt a slow flush rise. My, but he was attractive! And she realised his gaze was doing strange things to her.

Breaking away from that endless, compelling contact, she bit her lip and took the final four steps to the counter.

‘Yes, miss?’

Marianne summoned a polite smile. She felt slightly lost and shaky, and she could feel the man’s gaze boring into her back.

Still, she managed to reply to the landlady. ‘I am expecting someone to meet me here. I have travelled from London on the mail coach.’

‘Who is it you are expecting, miss?’

Marianne’s brow creased. ‘I am not exactly sure.’

Inside, panic was rising. What if there has been some mistake? What if there is no governess position?

‘I am to take up a position as governess at a place called Ledbury House. I was told to travel here by mail coach today.’

‘Ledbury House? This gentleman—’ the landlady indicated the fashionable buck ‘—is also travelling there. Perhaps you are expected to travel with him?’

Heart sinking, Marianne swung round to face him. His scowl had deepened as he’d listened to their exchange, and he now raised a quizzical eyebrow.

‘Curious...’ he mused. ‘And to think I was unaware of the delights this day would hold.’

Marianne was taken aback. She was unsure how to take this. The man’s words had been perfectly polite, but something about the tone suggested the possibility that he was not, in fact, delighted. Accustomed as she was to straightforward politeness, his words and tone felt disconcerting.

Something of what she was feeling must have shown on her face because, as she watched him, his expression changed to one of chagrin.

‘I have no doubt,’ he murmured cryptically, ‘that this is a mess of Fanny’s making and I am expected to fix it. Well, I shall do so this one time, but no more.’ With this enigmatic statement he drained his mug, then stood. ‘You’d best come with me.’

Not waiting for her reply, he swung away towards the door.

Marianne stood rooted to the spot, uncertainty bedevilling her. Should she go with him? A stranger? And she was to travel with him unaccompanied? Miss Marianne Grant, a lady, would never have done so. Miss Anne Bolton, a governess, could.

Conscious that all eyes were all on her, Marianne was surprised to find determination rising within her. Surprised because she did not often need to be brave. She was normally a placid, timid creature, most at home with a book in her hand and harmony and peace all around her.

This unknown gentleman was expecting her simply to climb into a carriage beside him—without any chaperon, maid or footman accompanying them. Perhaps he had a groom? Well, even if he didn’t, it was clear that everyone expected the governess to go with him and be grateful for the ride.

Although he was handsome, and strangely compelling, she was almost relieved to be wary of him—being guarded would be much, much safer than being attracted to him.

Torn between the surprising temptation to sit down somewhere safe and wait for an unknown rescuer and the even stronger temptation to run, to get as far away as she could from the danger inherent in being alone in a carriage with a man, Marianne recognised that her best option was simply to get into the carriage and hope she would be safe with him.

She had very few options. She must get to Ledbury House, where she would have food and a place to sleep, and where she could perhaps eventually feel secure.

You are no longer Miss Marianne Grant, she reminded herself, but a poor governess, and you need this situation. Hopefully she would be safe and unmolested by this man for the last part of her journey.

Swallowing hard—she could almost feel the fear in the back of her throat—she gave the landlady a polite nod and followed him out to the yard.

There he was, barking orders at the ostlers, instructing them to harness his horses to the carriage as soon as they could find the time. Two men and a stable boy had immediately jumped to their task, apparently caught out by the gentleman’s earlier than anticipated departure from the taproom.

Marianne walked slowly towards him. He glanced sideways at her, then turned his impatient gaze back to the ostlers. They stood like that, with Marianne feeling increasingly awkward and unsure, until the four beautifully matched greys were ready. The gentleman then held out his hand.

Confused, Marianne just looked at it.

‘Your bandboxes?’ he said mildly.

‘Oh!’ She passed them to him, and he stowed them in the back. One of the ostlers handed her up, and the gentleman got up beside her. He threw the men a couple of coins, and then they were off.

Marianne had never ridden in a high-perch phaeton before. It was high up, and there were no sides to speak of, and she was with a strange man who was taking her off to God knew where.

As a governess, this was now her lot. She had not the protection of any relative, nor even a servant known to her. Anything might happen to her, and no one would know or care.

It was not to be wondered at that fear, her constant companion these days, was now screaming inside her.

The carriage continued along the narrow streets of Netherton and onwards to the countryside beyond. Once free of the village the gentleman increased speed, driving his horses to what Marianne worried was an unsafe pace.

She wrapped her cloak more tightly around herself against the cold air and gripped the side of the carriage with her left hand. When they turned a bend in the road at what she felt was unnecessary speed, she could not prevent a small gasp.

Hearing it, he raised an eyebrow, but only slowed the pace slightly.

Marianne bit her lip. Between anxiety about being alone with a young man and driving too fast, she was all inner turmoil. Still, he had not so far shown any interest in her person. Except—Her mind wandered back to that first compelling gaze, when their eyes had been locked together and she had felt...something. Had he felt it too? Or had she imagined it?

The narrow seat was built to just about accommodate two people, with the result that he was seated uncomfortably close to her. His left thigh was aligned with her right leg, and she could feel his muscles tighten and relax as he concentrated on the exertions of driving. She could even detect his scent—a not unpleasant combination of what she thought was wood smoke and lye soap.

He seemed incredibly big and powerful and dangerous. And she had no idea who he was as he had not even had the courtesy to introduce himself.

They rounded another bend—to find a wide farm cart coming straight towards them! Marianne moaned, anticipating the inevitable collision. Their pace was too fast and the road too narrow to avoid it. She gripped more tightly and closed her eyes.

Seconds passed. Nothing. They were still moving! Opening her eyes, she was amazed to see that somehow they had passed the cart without collision. Twisting around, she saw that the cart was also continuing on its way. She sank back into her seat, unable to account for it.

‘I apologise.’

Surprised, she looked at him.

He took his eyes off the road long enough to give her a rueful grimace. ‘I was driving too fast. I have been taking out my frustration on you and everyone else.’

This was unexpected! She inclined her head, unable to disagree with him. ‘You were—and you have.’

His eyebrows rose and he chuckled. It was a surprisingly attractive sound.

‘Shall we begin again?’

He slowed the horses to a walk and turned to half face her. ‘Ashington—William Ashington. Also—since very recently—Earl Kingswood.’ He bowed his head to her.

Warily, she nodded back. ‘I am Miss Bolton.’

‘A pleasure to meet you, Miss Bolton. I understand,’ he continued politely, ‘that you are to be the new governess at Ledbury House?’

‘That is correct.’

She was as suspicious of his politeness as she had been thrown by his puzzling tone earlier. Still, perhaps he could give her some more information about the family.

She watched him closely. ‘I am to be governess to a girl, or a young lady, who lives there with her widowed mama.’

‘Lady Cecily, yes. Lord Kingswood died very recently.’

A flash of pain was briefly visible in his eyes. Interesting. So he was the new Earl and the previous Earl had been Lady Cecily’s father.

‘How old is Lady Cecily, do you know?’

He considered this, speaking almost to himself as he thought it through. ‘John and Fanny were married in ninety-four, and I believe their child was born a year or so after the wedding, so—’ he turned to Marianne ‘—she must be twelve or thirteen.’

‘Twelve or thirteen!’

Marianne had not been expecting this. She had, she realised, been hoping for a younger child, who might be easier to get to know. There was also the fact that a young lady of that age would soon be dispensing with the services of a governess anyway. So this position might not last for more than a few short years, regardless of how she performed in the role.

‘Is that a problem?’

‘Oh, no! Of course not. Just that I had somehow expected her to be younger.’ She waited, but he had nothing to say to this. She tried another angle. ‘Is Lady Cecily a quiet young lady, or rather more spirited?’

He snorted. ‘I have met her exactly once—certainly not long enough to form an impression of her character.’

His tone indicated he was becoming uninterested in the topic, so she let it go.

‘You are not, then, a regular visitor to Ledbury House?’

‘I have been there twice in the past fourteen years—once just before Lord and Lady Kingswood’s wedding, and once this week for Lord Kingswood’s funeral.’ His tone was flat.

‘Oh.’ This was a little confusing. If he had been the heir presumptive, then why was he not close to the family, and why had he so rarely visited?

She stole a glance at him. Gone was the indulgent politeness of the past few moments. In its place was the hard jaw that she had seen before. She sighed inwardly. She had no idea why he was so frustrated, or whether any of it was due to something she had said. Still, it confirmed that she was right to maintain her wariness.

They continued on in silence for a few moments, with Marianne trying to think of something to say, and Lord Kingswood seemingly lost in his own thoughts. The road continued to twist and turn, and Marianne, despite herself, began to relax a little as she saw how deftly the Earl was handling the reins. She would not, it seemed, perish today at the hands of a breakneck driver.

After a particularly neat manoeuvre in which he negotiated a double bend with skill and ease, she could not help exclaiming ‘Oh, well done!’ Immediately she clapped a hand to her mouth. ‘I do apologise! It is not for me to comment on your driving.’ She held her breath as she waited for his response.

His brows arched in surprise. ‘Indeed it is not. However, I shall indulge you, as you seem to have gone from abject terror to trusting my handling of the team.’

She blushed. ‘Oh, dear! Was it so obvious?’

‘Er—you were gripping the side as if your life depended upon it and gasping at every turn in the road. So, yes, it was fairly obvious.’

‘I have never been driven so fast before, and have never sat in a carriage so far above the ground. It all seemed rather frightening. I would not presume to judge your driving skills.’

He threw her a sceptical look. ‘Would you not?’

Her blush deepened. He knew quite well that she had been judging him.

‘Miss Bolton, have you heard of the Four Horse Club, sometimes called the Four-In-Hand Club?’

‘No? What is that?’

‘Never mind.’ He chuckled to himself.

‘Well, I think that you are a very good driver,’ she declared.

For some reason this made him laugh out loud. She could not help appreciating his enjoyment and noting how well laughter became him. Then she realised the direction of her thoughts and put an abrupt halt to them.

‘Miss Bolton,’ he stated, once he had recovered a little, ‘I must admit I am grateful that fate brought you to Netherton today, for you have enlivened a dull journey. The Four Horse Club, by the way, is for those of us who have developed a certain level of skill at carriage driving. Now, here we are.’

He swung the carriage around to the left, entering a driveway via a set of iron gates. Ahead, Marianne could see the house. It was a broad, welcoming, two-storey building with tall windows, a wide front door, and ivy curving lovingly up the right-hand side.

‘What a pretty house!’ she could not help exclaiming.

Lord Kingswood grunted. ‘It may look pretty from afar, but it has seen better times.’

It was true. As they got closer Marianne could see signs of ill-use and lack of care. Some of the windows had not been cleaned in a while, it seemed, and the exterior was littered with autumn leaves and twigs—debris that should have been cleared away long since.

Her heart sank a little. What did this mean for her? Could they afford a governess? Would her existence be uncomfortable? Her pulse increased as she realised she was about to meet Lady Cecily and her mother. What if they disliked her?

Lord Kingswood glanced at her. ‘You are suddenly quiet, and all the vivacity has left you. Do not be worried—I have no doubt that they will be glad of your arrival.’

She gave him a weak smile. ‘I do hope so.’

He pulled the horses up outside the house and jumped down. Immediately he came to her side of the carriage and helped her down. She could feel the warmth of his hand through her glove. It felt strangely reassuring.

She looked up at him, noting the difference in height between them. ‘Thank you,’ she said.

He squeezed her hand reassuringly, then let it go. She felt strangely bereft as he did so.

Turning, Marianne saw that the front door of the house was open and two ladies stood there. Both were dressed in mourning gowns, and one was a young girl of twelve or thirteen. This, then, was the widowed Lady Kingswood and her daughter.

Lord Kingswood strode forward and Marianne deliberately dropped back a pace.

‘Good day, Fanny,’ he said amiably. ‘Good day, Lady Cecily.’

Marianne searched their faces and her heart sank. Neither looked welcoming. In fact both looked decidedly cross. Still, she was taken aback when Lady Kingswood’s voice rang out, addressing Lord Kingswood.

‘And so you have returned, as you threatened to do! I wonder at you showing your face here again after what you have done to us!’ She turned to Marianne. ‘And who are you? One of his ladybirds, no doubt! Well, you shall not be installed in my home, so you should just turn and go back to wherever you came from!’

Chapter Four (#u1c8cfdd4-a808-5734-8021-39de660cecd1)

Marianne’s jaw dropped. What? What is this woman saying? She felt a roaring in her ears as all her hopes for a welcome, security, a safe place, crumbled before her. She stopped walking and simply stood there, desperately trying to fathom what was happening.

Lady Kingswood’s face was twisted with raw fury—mostly, it seemed, directed at Lord Kingswood. Lady Cecily held her mother’s arm, supporting her, and her young face was also set with anger. Both were white-faced, their pallor accentuated by their black gowns. Marianne knew that her own face was similarly pale.

Lord Kingswood kept walking, tension evident in every line of his body.

‘Oh, for goodness’ sake, Fanny, stop play-acting.’

‘Play-acting? Play-acting?’ Lady Kingswood’s voice became shrill. ‘You think this is some sort of jest, do you? Did you honestly believe that you could simply turn up here, with your lightskirt, and expect us to simply accept it?’ She took a step forward into the centre of the doorway. ‘You are not welcome here, and nor is she!’

‘Dash it all, Fanny, you have become quite tedious. She is the new governess—not a lightskirt. And if you would pause these vapours for one second you would see that.’ His tone was calm, unperturbed. ‘Besides, you know full well that you cannot prevent me from entering Ledbury House. Nor do you have any say in who accompanies me.’

She gasped. ‘That you should speak so to me! If John were here...why, he would—’

‘Yes, but John is not here, is he?’ He marched up to her and stepped inside.

Marianne felt a pang of sympathy for Lady Kingswood. Despite the woman’s erroneous assumptions about her, Lady Kingswood was a recently bereaved woman who was clearly in distress.

The two ladies had turned to follow Lord Kingswood inside, and Marianne could hear the altercation continuing indoors. Behind her, a groom had taken charge of the horses and begun walking them towards the side of the house. The noise of hooves on gravel, combined with the jingling harnesses, prevented Marianne from making out the words, but she could hear Lady Kingswood’s distress, punctuated by Lord Kingswood’s deep tones.

The door was still open, but Marianne remained rooted to the spot. What on earth was she to do now? How would she get back to Netherton? She would have to walk, and some of her precious coins would have to be spent to pay for the next mail coach back to London—probably in the early hours of tomorrow morning.

She hurried after the phaeton and retrieved her bandboxes from the groom. He failed to meet her eyes and was clearly uncomfortable with the entire situation.

Marianne squared her shoulders, turned, and began trudging down the drive. As she walked, she carefully focused her attention on each step.

Don’t think about reality. About the fact that you have no position. That you will be walking for the next hour just to reach the village. That you have no bed to sleep in tonight.

Could she afford to pay for a meal at the coaching inn? Once she had bought her ticket she would count her coins and decide what she must do.

Stop! She was thinking about exactly the things she should not be thinking about. Just walk, she told herself. Just. Walk.

‘Miss Bolton!’

Surprised, she turned. Judging by Lady Kingswood’s distress, she had not expected the argument between her and Lord Kingswood to end so soon. If she had thought about it at all, she would have said that neither of them would remember her existence for at least a half-hour.

Lord Kingswood was marching towards her, his face contorted with wrath. ‘Where the hell do you think you are going?’

‘To Netherton, of course.’

‘Lord preserve me from melodramatic females!’ He raised his eyes to heaven. ‘Give those to me!’

Stupidly, she just stood there, trying to understand what was going on. He took the luggage from her.

‘B-but...’ she stuttered. ‘Lady Kingswood—you surely cannot expect her to accept me as a governess, when she believes—’ She broke off, unwilling to repeat Lady Kingswood’s shocking assumption about her.

‘I can and I shall!’ he said through gritted teeth. ‘Now, Miss Bolton, please come into the house and stop enacting tragedies. The day is too cold to be standing in a garden exchanging nonsense!’

He turned and began walking back to the house. As if tied to her precious bandboxes by an invisible thread Marianne followed, her mind awhirl.

The door was still open. Marianne followed him inside. And there was Lady Kingswood, seated on a dainty chair in the hallway, sobbing vigorously, and being soothed by her daughter, who threw Lord Kingswood a venomous look.

‘Now then, Fanny,’ he said loudly, ‘apologise to the new governess!’

‘Oh, no!’ said Marianne. ‘There’s really no need.’

‘I think there is. Lady Kingswood has jumped to conclusions and insulted both of us. Fanny! Quit that wailing!’

Lady Kingswood sobbed a little louder. Overcome with compassion—for she could see how distressed the lady was—Marianne rushed forward and touched Lady Kingswood’s hand.

‘Oh, please, Lady Kingswood, there is no need! I can see your anguish. Is there something that can be done to aid you?’ She looked at Cecily. ‘Would your mama be more comfortable away from the hall?’

‘Yes,’ said Cecily. ‘Mama, let us go to the sitting room and we shall have some tea.’

Lady Kingswood let it be understood that she was agreeable to this, and Marianne and Cecily helped her up. One on either side, they supported her through the hallway. Her sobs had quietened.

The Earl did not follow, but Marianne could still hear him, muttering under his breath.

Marianne could not help remembering her own grief in the days after her parents’ death. She knew that she had been in a dark place, and that she had at times been so overwhelmed that, like Lady Kingswood, she had not been able to think straight. Whatever was going on between the widow and Lord Kingswood was none of her business. But she could not ignore someone in need.

Lady Cecily opened the first door to their left and they went inside. The pale February sunshine illuminated a room that was—or once had been—cosy. It was in need of a good clean, and perhaps the door could do with a lick of paint, but the sofa that they led Lady Kingswood to was perfectly serviceable.

She lay down, quiet now, and Marianne put a soft cushion under her head. ‘Now, Lady Kingswood, should you like a tisane? Or some tea?’ Marianne spoke softly.

‘Tea...’ The voice was faint.

Lady Cecily sat on the edge of the sofa and lifted her mother’s hand. Marianne looked around. Spotting a bell-pull near the fireplace, she gave it a tug.

‘It doesn’t work.’ Cecily rose from the sofa and opened the door. ‘Mrs Cullen! Mrs Cullen!’ Her voice was shockingly loud—and quite inappropriate for a young lady. ‘Some of the bells work, but not this one.’

Oblivious to Marianne’s reaction, the girl returned to her station by her mother’s side. Marianne sat on an armchair near the sofa and took the opportunity to study both of them.

Lady Cecily was a pretty young lady, with blonde hair, a slim figure and distinctive amber eyes. She carried herself well and was clearly very fond of her mama. Lady Kingswood, still prostrate on the sofa, with her hand over her forehead and her eyes closed, was a good-looking woman with fair hair, beautiful blue eyes, and the merest hint of wrinkles at the sides of her mouth. She was, Marianne guessed, in her early thirties. If Cecily was twelve—which seemed correct—then Lady Kingswood must have been married young. Married young and now widowed young.

It was not uncommon, Marianne knew. Why, when she herself had turned seventeen, three years ago, her parents had offered her a London season—which she had declined in horror. Go to London? Where Henry did his drinking and his gambling and his goodness knew what else? She had shuddered at the very idea.

Her parents, themselves more comfortable in the country, had let the matter drop, but had encouraged Marianne to attend the local Assembly Rooms for country balls and musical evenings. These she had enjoyed, and she had struck up mild friendships with some of the young men and women of a similar age. She had received two polite but unexciting marriage proposals, had declined both, and had continued to enjoy her life with her family.

Until the tragedy. That night when she had lost both parents at once.

Immediately a wave of coldness flooded her belly. Lord—not now!

Exerting all the force of her will, she diverted her attention from her own loss to the sympathy she felt for the bereaved woman and child in front of her. Gradually her pulse settled and the coldness settled down.

As she sat there, deliberately forcing her attention back to the present, she wondered where ‘Mrs Cullen’ was, and why she had not yet appeared. Lady Cecily was still sitting patiently, clearly unsurprised at the time it was taking.

Eventually Marianne heard footsteps in the corridor and the door opened, admitting a woman who must be Mrs Cullen. She was a harassed-looking woman in her middle years, with reddish hair and a wide freckled face. She wore the simple grey dress of a servant, covered with a clean white apron. Her arms were uncovered, her hands red and chapped from kitchen work, and there was a trace of flour on her right cheek.

She bobbed a curtsey to Lady Cecily. ‘Yes, miss?’

‘My mother is unwell. Could we have tea, please?’

‘Of course. Right away, miss.’

‘Oh, and Mrs Cullen, this is my new governess. Miss...’ She looked expectantly at Marianne.

‘Miss Bolton. Anne Bolton,’ Marianne said confidently. The lie was coming more easily to her now. That is not a good thing. ‘I arrived a short time ago.’

‘Yes, Thomas said so. Welcome, Miss Bolton.’

Marianne automatically thanked her, then frowned in confusion. Who is Thomas? she wondered.

Mrs Cullen must have noticed her confusion. ‘Oh—Thomas is the groom and the gardener, and I am the cook.’ She flushed a little. ‘I apologise for rattling on. It is nice to meet you, Miss Bolton. Now, I shall go and make that tea.’

She left in a flurry, but Marianne was relieved to feel that at least one person had welcomed her in a perfectly natural way.’

‘Thomas is married to Mrs Cullen’s daughter, Agnes. Agnes is our maid of all work.’ Lady Cecily was speaking shyly to her.

Marianne gave her an encouraging smile. ‘Mrs Cullen... Thomas... Agnes. I shall try to remember all the names. How many others are there?’

‘None. We used to have a housekeeper and a footman, and two housemaids, but they have all gone. And our steward died. He was old—not like Papa.’

‘None?’ Marianne was shocked.

A house of this size, an earl’s home at that, with only three servants?

From the sofa, a low moan emerged.

‘Mama!’ Lady Cecily was all attention.

‘Help me up.’

Assisted by her daughter, Lady Kingswood raised herself into a sitting position. Her face was blotched from her recent tears, but she was still an extremely pretty woman, Marianne thought. She could not help but notice the fine silk dress that Lady Kingswood was wearing. Cecily’s gown looked similarly expensive—the finest fabrics and the expert cut indicated that considerable expense had been laid out on both mourning dresses.

So why, Marianne wondered, have the staff all gone? And why is the house so dilapidated?

Lady Kingswood took a deep breath. ‘Miss Bolton,’ she began, fixing Marianne with a keen eye, ‘while I appreciate the kindness with which you responded to me just now, there are certain questions I must ask you.’

Marianne’s heart sank. ‘Of course.’

‘I contacted a London registry to find a governess, but they sent me no word that they had appointed someone. I had no notion of your arrival.’

‘They appointed me only two days ago, but assured me they would write ahead to let you know I would arrive today.’

‘No letter has been received.’ Her eyes narrowed. ‘So how did you manage to arrive with A—with Lord Kingswood?’

Haltingly, Marianne explained how it had come about. Lady Kingswood listened intently, but Marianne had the feeling that she was not convinced.

‘I assure you,’ she said earnestly, ‘I had never met Lord Kingswood before today.’

‘Hmm...’

Lady Cecily, Marianne noted, was looking from one to the other, her expression one of mild confusion. Lady Kingswood noticed it too.

‘Cecily, please pass me my shawl. It is positively freezing in here!’

It was true, Marianne thought. Still attired in her cloak, bonnet and gloves—and how rude she was to be so—nevertheless could tell that the sitting room was only a little milder than outdoors.

Discreetly, she removed the gloves and stowed them in the pocket hung under her cloak.

Cecily passed an ornate shawl to her mother, commenting as she did so, ‘The fire has not been lit in here, Mama. And Agnes will be helping Mrs Cullen with dinner. We shall have to wait until afterwards for her to set the fire in the parlour again.’

Lady Kingswood looked a little uncomfortable. ‘I should explain,’ she said, addressing Marianne, ‘that we have had to make certain economies during my husband’s illness. Temporary, of course.’