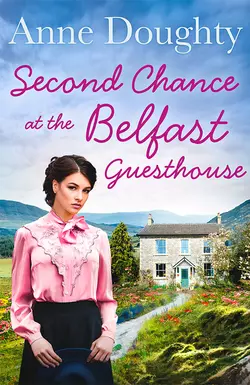

Second Chance at the Belfast Guesthouse

Anne Doughty

Will love be enough to overcome the odds? It is 1960 and Clare Hamilton is returning home to her beloved Armagh to marry Andrew, her childhood sweetheart. Full of the hope and possibilities of a newlywed couple, they plan to turn Andrew’s ancestral home into a guesthouse. Their ambition is to use their income to buy back the land of the former family estate so that Andrew can quit his hated job as a solicitor and farm the land he had known as a boy. But the sixties are a time of change, and when political unrest increases bookings begin to decline… Can the pair save their beloved guesthouse and achieve their dreams for a better life? Prepare to be spirited away to rural Ireland in this stunning new saga from Anne Doughty. Previously published as Come Rain, Come Shine Readers LOVE Anne Doughty: ‘I love all the books from this author’ ‘Beautifully written’ ‘Would recommend to everyone’ ‘Fabulous story, couldn't put it down!’ ‘Looking forward to the next one. ’

ANNE DOUGHTY is the author of A Few Late Roses, which was nominated for the longlist of the Irish Times Literature Prizes. Born in Armagh, she was educated at Armagh Girls’ High School and Queen’s University, Belfast. She has since lived in Belfast with her husband.

Copyright (#u4154b6e1-69da-5b11-93ba-69b4e913599b)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published as Come Rain, Come Shine in 2012

This edition published in Great Britain by HQ, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2019

Copyright © Anne Doughty 2020

Anne Doughty asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © November 2019 ISBN: 9780008328832

Praise for Anne Doughty (#u4154b6e1-69da-5b11-93ba-69b4e913599b)

‘This book was immensely readable, I just couldn’t put it down’

‘An adventure story which lifts the spirit’

‘I have read all of Anne’s books - I have thoroughly enjoyed each and every one of them’

‘Anne is a true wordsmith and manages to both excite the reader whilst transporting them to another time and another world entirely’

‘A true Irish classic’

‘Anne’s writing makes you care about each character, even the minor ones’

Also by Anne Doughty (#u4154b6e1-69da-5b11-93ba-69b4e913599b)

The Girl from Galloway

The Belfast Girl on Galway Bay

Last Summer in Ireland

The Teacher at Donegal Bay

For all those who have cherished

hope for peace in Ireland

‘Do what you can, do it in love and be sure that it

will be more than you ever imagined.’

Deara, fifth century healer from Emain

Contents

Cover (#udc35c64b-523d-52a6-ba65-f424be501b25)

About the Author (#ud0fbf4ff-711b-540b-92ab-b29bb28df1dd)

Also by Anne Doughty (#ua46e033c-87ac-517d-95a6-054209b668b9)

Title Page (#ud62b8dd6-a652-5858-842e-0c6a20980877)

Copyright (#u07295204-ea5c-5350-8aaa-3eeb47a7343e)

Praise (#u5e2cb05e-580c-523b-8da5-4ee3c5b1da76)

Dedication (#ub0128e40-30d3-55c1-a9f5-b9c119e535d9)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

One (#uce7e5777-544e-580f-b761-5bc3df3b1e26)

Two (#u7c3902a1-0368-53ff-8afb-e4b9c51abe9c)

Three (#uf27efac7-b18c-577e-96aa-54390859f0e7)

Four (#u57f615ba-964f-56a8-b4c1-23f39b9b4262)

Five (#u03f53029-9b12-53a9-9636-242f69c520b4)

Six (#u4aced7d7-3e91-5963-a819-8e66ea03b224)

Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader... (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading... (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

One (#ulink_36e46261-5b50-5dae-8ac6-aff576d0ba3e)

September 1960

The moment the Belfast flight was announced, Clare Hamilton put down her coffee cup and picked up the large, beribboned box parked neatly under the table. She walked quickly across the departure lounge, a small, slim figure in an elegant moss green suit and was among the very first passengers to enter the quiet, echoing corridor that led down to the roar and whine of engines, the oscillating turbulence of aircraft movements and the dazzling glare of acres of pale tarmac.

The waiting Vanguard shimmered in the strong evening sun as she paused to hand over her ticket. How long it might be before she flew again she could not guess, but if this was to be her last flight for some time, she hoped it would be like the one she’d made back in April. On just such a sunlit evening she’d flown into Aldergrove over the green landscape she so loved to the totally unexpected sequence of events which had changed her life.

‘May I put that in the hand luggage store for you, madam?’ the young steward asked politely, with a small bow towards her silver and white striped box.

He put out his hand for the box, large and rectangular, but clearly light in weight.

‘I’ll put it down by my side where it won’t get in the way,’ she said, smiling at him. ‘It’s my wedding dress,’ she added, as he seemed about to protest.

‘Who’s the lucky man?’ he asked, his careful pronunciation replaced by a familiar Ulster accent.

She laughed, suddenly delighted by the sound of home and the broad grin that creased his face as he waved her past.

She made her way to the window seat she’d booked weeks ago from her office in the Place de l’Opéra, settled herself and tried to relax, but the excitement that had pursued her all day was not to be dispersed so easily. She was going home, home to Andrew and to her beloved little green hills. In three days they would be married, ahead of them a life together quite different from any they had once imagined.

She looked down through the dusty window at the familiar activities of the airport, the small vehicles scurrying to and fro bringing luggage and catering supplies, the large fuel tankers now uncoupling their hoses and returning to their depot. Luggage manifests were being exchanged. A Royal Mail van appeared at speed, its back doors sprang open, sacks of mail flew out on to waiting trolleys that quickly disappeared from view. She listened for the familiar sound of the hold doors being banged shut.

Whenever she watched the familiar scene, whether in London or Toulouse, Zurich or Athens, she always thought of the summer of 1957, shortly before graduation, when she’d arrived in London, wearing her best summer dress and carrying a single suitcase. She had tramped the dimly lit platform at Euston Station, struggled with the escalator to the Tube, spent a night in a student hostel, got herself to Victoria for the train to Paris and wept. Whenever no one was looking, and even sometimes when they were, tears had streamed down her face. She was quite alone, without home, or job, or future. She had taken the Liverpool boat, because she had broken off her engagement with Andrew. She had loved him for so long and been so happy, but their bright hopes had been shattered and she could see no way forward for them.

The engines roared and the aircraft rose into the clear sky. The wing dipped over the Hounslow reservoirs as they turned west and she studied the streams of traffic flowing in all directions, the veins and arteries feeding the great city at their heart. She tried to take in every detail of the moving pattern for she might never come this way again. Moments later, the course correction complete, she caught sight of the Chilterns, wisps of cloud blurring their outline.

She moved uneasily in her seat, adjusted the box propped between the window and her left foot. Everyone had said she’d got it wrong, that she and Andrew were made for each other, but after his cousin was killed in a road accident, he’d abandoned their plan to go to Canada and had taken over the running of the Richardson family estates. She’d seen him shoulder the responsibility for his grandmother, his aunt and uncle, his cousin Ginny. In fact, it seemed he’d accepted his obligations to everyone except herself, so that all they’d planned together appeared just a beautiful dream.

It was not the first time in her life the world had come crashing down around her. Long years earlier, on a hot June afternoon in 1946, she and her young brother William had been taken to the Fever Hospital outside Armagh by the Headmaster of their school. Days later, her mother and father, Ellie and Sam Hamilton, had both died in the typhoid epidemic of that year leaving them parentless and homeless.

She had found a new home with her grandfather, Robert Scott, and then, only weeks after a scholarship had taken her to university in Belfast, he’d walked down the lane to stand by the anvil in the forge where he’d worked all his life and died instantly of a heart attack.

Once again, she had found herself homeless. The landlord had given her two weeks’ notice to dispose of the contents. There’d been help with that sad task from Jack Hamilton, the youngest of her uncles, but dealing with the memories of a house lived in by Scott blacksmiths for over a century was a different matter. Harder still was the loss of what had been her second home, the one she’d lived in for half her eighteen years.

Suddenly the distant pattern of the English Midlands far below disappeared completely. The grey mizzle that swirled around the aircraft and streaked her window with tiny raindrops as they continued climbing into cloud enveloped her in the chill remembrance of that bleak time. After Granda Scott died the only comfort she knew came from Andrew’s letters and their occasional short phone calls in the dim hall of the house in Elmwood Avenue where she’d inherited her cousin Ronnie’s old student room after he packed up and headed for Canada.

She went on staring through the window, perfectly aware she was rigid with tension. She had never been afraid of flying, had enjoyed all but the most turbulent of flights, but what she could never bear was this grey blanket that removed all light and joy from a world where previously there had been sunshine and colour.

She took a deep breath, extracted her book from her handbag, tried to focus on the words on the page. Then, as suddenly as it had disappeared, the sunlight returned. It poured down from a blue sky, glancing off the moist, glistening wing, the view below now of dazzling white cloud caps. She shut the book gratefully. Yes, she had known the light would return, that above the murk the sun always shone. But no matter how many times it happened, she still feared the grey mist. It was not the mist in itself. It was the fear that, like some of the worst times in her life, the bleakness would go on for so long she would finally lose heart and give up.

The cloudscape below always made her think of the Rocky Mountains, though any postcards she’d ever seen of them made it perfectly clear they didn’t look like this at all. Probably her Rocky Mountains were pictures in her imagination, something she had called up when she and Andrew were planning to go to Canada.

The plan itself emerged quite unexpectedly one day when they’d had an outing with lunch as a special treat. Andrew had looked so miserable most of the time she’d forced him to tell her what was wrong. He’d finally admitted that being back in Belfast and near her didn’t make up for the misery of his job with the firm of solicitors his uncle had arranged for him.

He’d been so negative to begin with, had said there was no other way of earning a living, given all he had was a Law Degree from Cambridge. Gazing down at the towering mountains of cloud, silhouetted against the brilliant blue sky, she remembered how she’d refused to go along with his negative view of himself and asked him what he’d do if he were rich and if money were no object. His answer had delighted her, for it was the same answer he’d given years earlier when the two of them were playing Monopoly with his cousins Ginny and Edward at Caledon that very first summer they’d been able to spend time together.

‘I’d buy cows,’ he said firmly. ‘But not here,’ he added, looking just as dejected as when they’d begun to talk.

She’d stopped smiling instantly, but she went on asking questions and by the time they’d left their sitting place, they’d made their decision. Canada it would be. The Palliser Triangle to be precise, because Andrew had a relative who had gone out there in the 1920s and now had a very large ranch with a substantial herd.

The plan to go to Canada had sustained her through the last year of her Honours course at Queens and Andrew’s year in Linen Hall Street, a junior solicitor at the beck and call of elderly partners. They were very experienced and quite meticulous over points of law, but they had a set of values and attitudes towards the people they encountered that he found almost impossible to stomach.

Then, on that wonderful day when Clare finished her last exam and they’d planned a picnic supper in the Castlereagh Hills to celebrate, it all began to go wrong. Ginny and Edward had had a head-on collision on a narrow country road with a vehicle that shouldn’t have been there. Edward never regained consciousness, Ginny was left with scars on her face and arms and Andrew found himself head of the family and responsible for both the house in Caledon and his grandmother’s home at Drumsollen. The vision of wide acres of prairie and glistening mountains crumbled at a touch, like a warm and comforting dream dissolving as one wakes to the chill of a winter morning.

Perhaps she had been wrong to break off their engagement. If she’d stayed with Andrew, not the most practical of men, she could have helped him cope with the tangle of financial affairs, mortgages and death duties that enmeshed him. She could have supported Ginny, who’d taken her half-brother’s death so very badly and whose scars would need more than plastic surgery if they were not to affect her for the rest of her life.

She felt the bite of tension in her shoulders as the images flowed back. From a point in the future, it’s always easy to see how things could have been different. Here and now, after more than two years in a demanding job, with a new life, new friends, renewed hope for the future and a wedding dress waiting to be worn, it was just possible to see that there might have been an alternative. But the person she was now was not the person she was then. The girl who set off on the Liverpool boat could not have shared Andrew with all the many and conflicting demands he had accepted without question.

She looked at her watch. The time had gone so quickly. Any minute now the familiar tape-recording would tell them to fasten their seat-belts. As they began to lose height, she took a last look at her Rocky Mountains and continued to argue with herself, as if it were a matter of great urgency that she decided what she really thought. Without their parting, there would have been no job in Paris, no new friends like Louise and Jean-Pierre. Especially, there would have been no Robert Lafarge, the eminent French banker who had given her a job and had now become a dear friend, one who treated her like the daughter he’d lost when his wife and children disappeared in the Fall of France.

Parting with Andrew had been heartbreaking, but she’d done her best to begin all over again. When they’d met up again by accident last April and spent a weekend together, they’d admitted they’d found out things about themselves they might never have learnt in any other way.

She prepared herself as they descended rapidly. What did it matter if she arrived home in a rainstorm? She smiled to herself as she remembered her leaving party, the laughter and the gaiety in her favourite restaurant. Her colleagues had teased her, wished her luck, drunk her health with rather a lot of very good champagne and promised to visit her in Ireland, even if it did rain all the time.

Moments later, they came out below the base of the cloud. To her absolute amazement, she saw the familiar outline of the Isle of Man lying in the midst of a deep blue Irish Sea. Beyond, to the west, as far as the eye could see, there wasn’t a cloud in sight, the green and lovely land she called ‘home’ stretched into the far distance, radiant in the low evening sunshine. The Mourne Mountains threw long shadows towards the gentle hills of County Down as the aircraft moved northwards. As the wing dipped over the brick-covered acres of Belfast, she caught the first sight of the Antrim Hills. Dark, hard-edged basalt, as uncompromising as the six-storey mills that sprouted at their feet. Beyond lay the gleaming expanse of Lough Neagh, set amid green fields dotted with small, white farmhouses, placed like models on a playroom floor, a handful of trees alongside each one to shelter it from the prevailing wind.

She wished she could pause, however briefly, so that this moment would be fixed forever in her mind. She needed time to gaze at the far horizon, to separate out the Sperrins and the mountains of Donegal from the distant banks of cloud, beyond which the sun would descend into the Atlantic. But only seconds later they were low over the calm water of the lough. They bumped slightly on the new concrete runway at Aldergrove, disturbing, if only for a moment, the hares who were feeding on the rich grass alongside.

The engines roared in reverse, the whole cabin vibrating, then as the noise and vibration died away the plane taxied so slowly towards the new terminal building that she was able to look down into the yards of the nearest farms. The newly-milked cows moved back from byre to meadow, as indifferent to the noise of their new neighbours as the hares who grazed on the margins of the runways.

‘Andrew, I’m here,’ she said, catching the sleeve of the tall, fair-haired young man who was leaning over the balcony and peering down anxiously into the baggage hall.

‘Clare,’ he gasped, relief spreading across his face as he spun round and clasped her in his arms. ‘I thought you hadn’t made it. I was down at the gate to meet you.’

‘I thought you would be, but I couldn’t see you,’ she explained, shaking her head. ‘The plane was full of large men. All I could see was business suits.’

He laughed and clutched her more firmly. ‘I don’t think I’ll be able to let you out of my sight for a very long time,’ he confessed. ‘I’ve been going mad for the last hour.’

He stopped and looked sheepish as he released her.

‘I know I’m silly, but I can’t bear the thought of losing you again,’ he began. ‘Now tell me, did you have a good flight?’ he went on, making an effort to collect himself.

‘Not entirely,’ she replied honestly, as she smiled up at him. ‘In the end, it was quite wonderful, but I had a bad time too. There was thick cloud and I kept thinking about what happened to us two years ago. And then, when I did get here I couldn’t find you either.’

‘Pots and kettles’ he said, his blue eyes shining, as he kissed her again. He dropped his arm round her shoulders and held her close as they made their way downstairs to the empty carousel.

She laughed, delighted by the familiar phrase. It was one she’d learnt from her grandfather. She could hear him now, see the wry look on his face; ‘Shure them two are always right, one’s as bad as the other, and when they give off about each other, it’s the pot callin’ the kettle black.’

All the pots and kettles at the forge house were black from the smoke from the stove. They’d have been even worse when they were hung on a chain over an open fire, as once they were in the days before there was a stove at all. Like everything else she had shared with Andrew from her life with her grandfather, he’d remembered it.

‘Six of one and half a dozen of the other,’ she replied, offering him back the phrase his mother would have used.

For so many years, they’d exchanged words and phrases as they’d explored their very different life experiences. While Clare had never moved beyond ‘her teacup’, a small area round Armagh itself and her grandparents’ homes, Andrew had spent most of his time in England. He had been born at Drumsollen, the big house just over a mile from the forge, where his grandparents had lived, but after his parents had been killed in the London blitz, the very day they had taken him over to start prep school, Andrew was seldom invited back. Only when his grandfather, Senator Richardson, insisted on his coming, did his grandmother agree to a short visit.

‘Here, let me carry that,’ he said, reaching out his free hand for her cardboard box.

‘No, I’m fine. It’s not heavy.’

‘What is it?’

‘My wedding dress.’

He laughed and shook his head. ‘My dear Clare,’ he began with exaggerated patience, ‘it is only seeing you in it before the wedding that brings bad luck, not me carrying it.’

She laughed aloud, relief and joy finally catching up with her as he began to tease her.

‘Well, I’m taking no chances anyhow,’ she came back at him, as the first of the luggage appeared in front of them.

She had arrived and all was well. It wouldn’t even matter now if her luggage had gone to Manchester or Edinburgh. She had her dress. The rest could be managed.

‘So where are we spending the night?’ she asked, as they drove out of the airport.

‘Officially, you are staying with Jessie’s mother at Ballyards,’ he said, glancing across at her.

‘And unofficially?’ she replied, raising an eyebrow.

‘Jessie told her you were arriving tomorrow. Slip of the tongue, of course, but we can’t just have you arriving when she’s not expecting you.’

‘Of course not,’ she agreed vigorously. ‘I’ll just have to come home to Drumsollen with you.’

‘I was hoping you’d say that,’ he said, as they turned on to the main road and headed for Armagh.

The sun had dipped further now, and with the light evening breeze that had sprung up, its golden light rippled through the trees that overhung the road. The first autumn leaves caught its glow and small heaps lying by the roadside swirled upwards in the wind of their passing.

‘Let me, Andrew,’ she said, as they drew up at the newly-painted gates of Drumsollen.

She paused as she waited for him to drive through, looking across the empty road, grateful for the fresh air after a day of sitting in cars and planes. This was where it had all begun, so many years ago. She and Jessie had left their bicycles parked against the wall by the gates while they went down to their secret sitting-place by the little stream on the opposite side of the road. They’d come back up to find Andrew bending over her bicycle. Jessie thought he was letting her tyres down, but Clare had taken one look at him and known that could not possibly be. In fact, he’d been blowing them up again after some boys from the nearby Mill Row had indeed let them down. She closed the gates firmly and got back into the car.

‘I can hardly believe it, Andrew. Drumsollen is ours.’

‘God bless our mortgaged home,’ he said, grinning, as they rounded the final bend in the drive. Ahead of them stood the faded façade of the handsome house where generations of Richardsons had lived, its windows shuttered, its front door gleaming with fresh paint.

‘Andrew! My goodness, what have you done?’ she demanded as he stopped by a large, newly-planted space in front of the house.

‘Parterre, I think is the word,’ he said, looking pleased with himself. ‘But we could only manage half. John Wiley found the plan inside one of the old gardening books Grandfather left him, so we poked around to see if we could find the outline. We knew where it ought to be, because June remembered it from before the war. It showed up quite clearly when we started mowing the grass. What d’you think?’

‘I think it’s quite lovely,’ she said, running her eye over the dark earth with its rows of bushes. ‘Did you choose the roses?’

‘No, not my department,’ he replied, shaking his head. ‘Given I hadn’t got my favourite gardener at hand, I thought Grandfather’s choice would be more reliable. There was a list with the plan. We got the bushes half-price at the end of August, so I’m afraid there’s not much bloom.’

‘There’s more than enough for what I need,’ she said happily, as they parked by the front door and got out together. ‘Have we time to go up to the summerhouse before the light goes, or are you starving?’

‘There’s plenty of time if you want to,’ he said easily, drawing her into his arms again. ‘June left me a casserole to heat up. I think by the size of it she guessed you were coming, but she didn’t say a word,’ he added, as he took her hand.

They crossed the gravel to the steps that led up the low green hill which hid Drumsollen from the main road and climbed in silence. This was where they had come in April after their unexpected meeting. This was where they had agreed their future was to be together after all.

‘Little bit of honeysuckle still blooming,’ she said, as they came to the highest point and stood in front of the old summerhouse, which Andrew had restored over a year ago, his first effort to redeem the loss of the home he thought he must sell. They stood together looking out to the far horizon. The sun appeared to be sitting on the furthest of the many ridges of land between here and the distant Atlantic.

‘Clare, do you remember once saying to me that you loved this place, that you wanted to be here, but you’d be sad if you never saw anything beyond these little green hills?’ he asked quietly.

‘No, I don’t remember saying it, but I’m sure I did,’ she said slowly. ‘It’s true, of course. And you always did pay attention to the really important things I said.’

‘Makes up for my other unfortunate characteristics,’ he added promptly.

She turned towards him and glared at him until he laughed.

‘Sorry. I’m not allowed to refer to my less admirable qualities.’

‘Oh yes, you can refer to them if you want, but you are not allowed to behave as if they were real.’

‘But they feel real,’ he protested. ‘I’m no use with money. I can’t stand sectarianism, or arrogance, or injustice. What use is that in the world we’ve got to live in?’

‘Andrew dear, it only needs one of us to be able to do sums. I’ve had a holiday from the things you’ve been living with. I’m not ignorant of them, just out of touch. Does it matter?’

‘No, nothing matters except that we are together. I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have said what I said to spoil your homecoming. Here of all places, where we were so happy last April.’

Clare looked at him and saw the distress and anxiety in his face. She thought of the little boy who’d been told on his very first day at prep school that he had lost his parents. ‘Andrew, my darling. We both have weaknesses. Look at the way we both got anxious when I was flying. With any luck our weaknesses won’t attack both of us at the same time,’ she began gently, taking his hands in hers. ‘Let’s just say that between us we’ll make one good one.’

He nodded vigorously and looked away.

She knew he was near to tears but said nothing. He’d been taught for most of his life to hide his feelings; it would take many a long day for him to be easy even with her.

They stood for some time holding each other and kissing gently. As the sun finally went down, they stirred in the now chill breeze and noticed that the sky behind them had filled with cloud. A few spots of rain fell and sat on the shoulders of Andrew’s suit until she brushed them off.

Clare laughed. ‘We’re going to get wet,’ she said cheerfully, as they turned back down the steps to the empty house below.

‘No,’ he replied, ‘it’s been doing this all day. We’ll be fine. And what does it matter anyway,’ he added, beaming, as he put his arm round her. ‘We’ll be all right, come rain, come shine.’

Two (#ulink_5009f8b8-7500-59b5-9a4d-74c469036d71)

The little grey parish church built by the Molyneux family in the early 1770s for the workers on their estate at Castledillon, and their many tenants in the surrounding farmlands, sits at the highest point of the townland of Salters Grange. Not a particularly high point in effect, for the hills of this part of County Armagh are drumlins, low rounded mounds, their smooth green slopes contoured by moving tongues of ice that reshaped the land long ago, leaving a pattern of well-drained hillsides and damp valley bottoms with streams liable to flooding at any season after the sudden showers carried by the prevailing, moisture-laden west wind from the Atlantic, a mere hundred miles away.

Despite its modest elevation, the church tower and the thin grey spire above has an outlook that includes most of the six counties of Ulster. From the vantage point of the tower’s battlements, you could scan the surrounding lowlands, take in the shimmering, silver waters of Lough Neagh and, on a clear day, penetrate the misty blue layers of the rugged hills of Tyrone to glimpse the far distant mountains of Donegal.

From the heavy iron gates that give entrance to the churchyard, the view is more limited, a prospect of fields and orchards, sturdy farmhouses with corrugated iron hay sheds and narrow lanes leading downhill to the Rectory, the forge or the crossroads. Through gaps in the hedgerow, a glint of sun on a passing windscreen marks the line of the main road linking the nearby villages with their market town, Armagh, dominated by the tall spires of the Catholic cathedral and the massive tower of the Protestant one, regarding each other from their respective hills.

On this bright September afternoon, the sun reflecting off the grey stone of the tower, the gates stand open, a small, battered car parked close by, as two women make their way up to the church door, their arms full of flowers and foliage.

‘You divide them up, Ma, and I’ll get out the vases,’ said the girl, as she lowered her burden gently on to the pedestal of the font. ‘Aren’t they lovely? Where did Clare get them?’

‘Sure, they’re from Drumsollen,’ June Wiley replied, watching her eldest daughter finger the bright blooms. ‘Hasn’t Andrew and your Da replanted one of the big beds at the front?’ she went on, as she began to strip green leaves briskly from the lower stems. ‘They’ve half of it back the way it was in the old days when the Richardsons had three or four gardeners,’ she added, with a little laugh. ‘You’ll see great improvements at Drumsollen. Mind you, that’s only the start. They’ve great plans, the pair of them. They’ll maybe take away some of your trade from the Charlemont.’

‘That’ll not worry me after next week,’ Helen replied cheerfully. ‘I’ll have my work cut out keeping up with all these Belfast students cleverer than I am.’

‘Now don’t be sayin’ that,’ June replied sharply, as Helen lined up a collection of tall vases. ‘Sure didn’t Clare go up to Queens just like you’re doin’ and look where she’s got to. Just because you come up from the country, ye needn’t think those ones from Belfast are any better than you are. Didn’t you get a County Scholarship? How many gets that?’

‘Clare was the first one from round here, wasn’t she?’

‘She was indeed, an’ I’ll never forget the day she got the news. Her grandfather was that pleased he could hardly tell me when I called at the forge to ask. I thought he was going to cry.’

‘Wish he was here for tomorrow, Ma. He’d be so proud,’ Helen replied, looking away, suddenly finding her own eyes full of tears, so sharp the memory of the old man in his soot-streaked clothes.

‘Aye, he would. But the other granda’s coming from over Richhill way with her Uncle Jack. So I hear. But she hasn’t mentioned her brother who lives with them. She talks about the uncle often enough, but the brother I’ve never met. They say he’s kind of funny. Very abrupt. Unsettled. Apparently the only one can manage him is Granda Hamilton. The granny pays no attention to him at all.’

‘Is she not coming to the wedding?’

‘Oh no. Not the same lady,’ the older woman replied, her tone darkening. ‘Apparently she won’t go to weddings or funerals. Says they’re a lot of fuss about nothing. But I hear she’s bad with her legs, so maybe it’s an excuse,’ she added, a frown creasing her pleasant face as she laid roses side by side and studied the length of their stems.

They worked quietly together as the afternoon sun dropped lower and the light faded in the north aisle. June Wiley had always loved flowers and had learnt long ago how to make the best of whatever the gardener’s boy had brought into the big kitchen at Drumsollen. She’d started work there as a kitchen maid, progressed to the parlour and had been instructed in the art of flower arranging by Mrs Richardson herself, a formidable lady known to all the staff as The Missus. It was later that young Mrs Richardson had chosen June as nurse for her son. She was a very different woman from her mother-in-law, warm-hearted and kindly, devoted to her little boy. June herself had gone in fear of The Missus for most of her working life, but she ended up by caring for her right up until her death in the house only eighteen months earlier.

‘Have you seen her dress, Ma?’ Helen asked, as she knelt down and swept up small fragments of foliage and discarded thorns from the step of the font.

‘No, not yet. She said she’d bring it when she came to help me with the food this morning, but she had to leave it behind at Rowentrees. She said she hung it up for the creases to drop out for she didn’t want to risk the iron. I think it has wee beads sewn into it here and there.’

‘I wonder what she’s thinking about today,’ Helen said, half to herself. ‘She used to work at Drumsollen with you, didn’t she, washing dishes and making beds like me at the Charlemont, and now she’s the lady of the house.’

June gave her daughter a thoughtful look. A clever girl she was by all accounts, but she’d always made up stories in her head. That was not something June had much time for, her own life having been hard. She had tried to bring up her three girls so they wouldn’t get ideas that would let them down.

‘Oh, something sensible, I wouldn’t wonder,’ she replied crisply. ‘Oh, she loves him all right, she always has from ever they met, but she’ll not think of him and her till she’s seen to what has to be done. Them visitors ye have at the Charlemont, Mr Lafarge and the French lady and her daughter. She’ll make sure they’re all right before she thinks about her and Andrew. Can’t remember their name.’

‘The girl is Michelle.’

June shook her head. ‘No, I meant the mother, Madame Saint-something. Clare said she was awful good to her when she first went over to France, bought her a suit for her first interview and taught her how to dress like the French do.’

She stopped suddenly, straightened up and laughed, so unexpectedly that Helen nearly dropped her dustpan.

‘What’s the joke?’ she demanded.

‘You should’ve seen her this mornin’,’ her mother said, shaking her head. ‘A pair of jeans I wouldn’t let any of you girls be seen dead in and an old shirt. It must have been Andrew’s before it shrank in the wash. I wonder what the French lady would have thought of that.’

‘It’s Madame St Clair, Ma, and she’s very nice. Speaks beautiful English. And Mr Lafarge is very polite. But I though he was American. He has an American accent.’

‘Oh aye. That’s another story too,’ June replied, lifting the first of the arrangements into place. ‘Clare says he learnt English from the Americans at the end of the war and he has some awful accent. Not the right thing at all in his job. I suppose the French are just as fussy about that sort of thing as they are here. Sure old Mrs Richardson, God rest her, was furious when young Andrew came back from a visit to Brittany with some country accent he’d picked up. Clare told me once that when he wants to make her laugh he asks her would she like ‘fish and chips’.

‘Poisson et pommes frites’

‘Aye, maybe that’s the right way of it, but that’s not how Andrew says it. The Missus always used to talk French to him when he came visitin’ and when he landed back with this accent she was fit to be tied. A Richardson talkin’ like a servant.’

‘But it was only in French, Ma. What did that matter? It was how he spoke English that would matter here, wouldn’t it?’

‘Well, I suppose you’re right, but these gentry families are full of things you wouldn’t believe. They’re always lookin’ to see whose watchin’ them. An’ the less money they have, the more they look,’ she added, nodding wisely. ‘Now the Senator was always the same to everyone, high or low, but The Missus, she was a different story. She was always on her high horse about somethin’ and yet she once told our Clare that Andrew wasn’t good enough for her, that she could do better for herself. An’ Clare a wee orphan with her granda a blacksmith.’

‘Even though Andrew was a Richardson and might some day have a title?’ Helen asked, her dark eyes wide and full of curiosity.

‘Yes. She hadn’t a good word for Andrew an’ I’ll never understand it, for you’d travel a long way to meet a nicer young man. She always said he had no go in him. He was clever enough, but he never made the best of himself, even with the posh boarding school in England and the uncle behind him sending him to Cambridge to do Law.’

‘Was Law what he wanted to do?’

June removed a dead leaf from the spread of colour which would grace the font itself and looked at her daughter thoughtfully.

‘Maybe it wasn’t,’ she said flatly. ‘I’ve often wondered about it, but I never had the heart to ask him,’ she went on. ‘When you got your scholarship to go up to Queens, it didn’t matter whether you did Geography, or History, or English. I know your teachers advised you, but it was you decided what you wanted to do. But then we’re only working people. If you’re a Richardson, it’s a different kettle of fish. The family will tell you what to do if you don’t already know what’s expected in the first place. As far as I can see there’s no two ways about it, you just have to do it.’

‘Well, there’s none of the family left, now The Missus is gone. There’s just Andrew and Clare. They can do what they like, can’t they?’ Helen responded cheerfully, her face lighting up with a great beaming smile.

‘Aye well, I suppose you’re right. But you needn’t think, Helen, that falling in love and getting married is all roses. You can’t know what’s up ahead and it may not turn out the way you hope.’

Helen nodded and said nothing. Her mother was always warning her against disappointment. There was no use arguing. She just didn’t seem to see how wonderful it was for Clare and Andrew to have found each other and to make such a marvellous plan for turning Drumsollen into a guest house. They were going to save up and buy back the land that had once made up the estate, then Andrew would give up his job and farm just as he had always wanted. Helen smiled to herself. It was exactly the sort of plan she’d make herself if she found someone she really loved.

‘Time we were gettin’ a move on, Helen,’ June said abruptly, as she turned round and saw her daughter gazing thoughtfully at a handful of rose leaves in the palm of her hand. ‘Yer Da’ll be home soon and no sign of his tea and we’ve both got to go back up to the house tonight to give them a hand.’

‘Right, Ma, what do you want me to carry?’ asked Helen quickly, as she dropped the petals in her pocket. One day, she thought, I’ll marry someone lovely and I’ll have a shower of rose petals as I come out of the church just like they have in films.

‘D’ye not think that neckline is a bit much for Salters Grange?’

Clare, who was dressed only in a low cut strapless bra and a slim petticoat, turned round from the dressing-table and laughed, as her friend Jessie pushed open the door of the bedroom, dropped down on the bed, and kicked off her elegant new shoes.

‘I hope ye slept well in my bed,’ Jessie continued. ‘I left ye my teddy-bear to tide you over till tonight,’ she went on, looking around the room that still had her watercolours and photographs covering all the available wall space.

‘Oh, I slept all right,’ replied Clare, as she dusted powder over foundation with a large brush. ‘By the time June and I had got all the food organized and the tables laid I could have slept on the floor. But your bed was much nicer. Thank you for the loan of it.’

‘Or the lend of it as we always said at school and got told off for.’

Clare smiled, relieved and delighted that Jessie seemed to have fully recovered her old self after the hard time she’d had with her second child.

‘How’s Fiona?’ she asked, as she turned back to the mirror.

‘Oh, driving us mad,’ she said calmly. ‘I sent Harry to walk her up and down and tire her out a bit before Ma tries to get the dress on. She can talk about nothin’ but Auntie Clare and Uncle Andrew. Does it not make you feel old?’

‘No. Old is not what I feel today,’ she said lightly. ‘Blessed, I think is the word, as long as you don’t think I’ve gone pious,’ she added quickly. ‘It’s not just Andrew. It’s being home and having family. It’s you and Harry and wee Fiona and your mother and all the people who’ll come to the church. Even the ones that come to stand at the gate, because they go to all the weddings, or because they remember Granda Scott.’

‘Aye, there’ll be a brave few nosey ones around,’ Jessie added promptly. ‘Ma says she heard your dress was made by yer man Dior himself.’

Clare laughed, stood up and reached out for the hem of the gleaming, silk gown hanging from the picture rail.

‘Look Jessie, I only found it this morning.’

Jessie leaned over and looked closely at the inside hem. ‘Good luck, Bonne chance, Buenos . . . something or other . . . and there are names as well. Ach, isn’t that lovely? All the way round. Who did that?’ she demanded, her voice hoarse, her eyes sparkling with tears.

‘The girls in the work room. I knew them all, because I had to have so many suits and dresses, but when I had the last fitting there was nothing there. I’m sure I’d have noticed.’

‘So you’ll have luck all round ye and in whatever language takes your fancy . . .

Clare nodded, her own eyes moistening at the thought of all the little seamstresses taking it in turns to embroider their name and their message. She paused as she slipped the dress from its hanger and took a deep breath. The last thing she must do was shed a tear. Whatever it said on the packaging she had never found a mascara that didn’t run if provoked by tears. Tears of joy would be just as much of a disaster as any other kind.

The crowd of women and children gathered round the churchyard gates were not expecting very much. They knew it was to be a small affair with only close family. In fact, there were those who thought there couldn’t even be much in the way of close family if June Wiley, the housekeeper, her husband John and their girls were to be among the guests, even if June had once been Andrew Richardson’s nurse. They certainly did not expect any ‘great style’ from anyone except the bride. Even that was a matter of some doubt as rumour had it she’d bought her dress on the way home from Paris and arrived with it at the Rowentrees in a cardboard box.

The first guests to arrive did little to disperse their expectations. Jack Hamilton drove up in a well-polished, but elderly Hillman Minx. He was accompanied by his father, Sam, now in his eighties, who got out of the car with some difficulty, but once on his feet, smiled warmly at the waiting crowd, pushed back his once powerful shoulders and tramped steadily enough up to the church door.

Charlie Running, old friend of Robert Scott, walked briskly up the hill from his cousin’s house and said, ‘How are ye?’ to the gathered spectators, for Charlie knew everyone in the whole townland. Before going inside he tramped round the side of the church to pay his respects to Robert.

Next to arrive were the Wileys. June, John and all three girls, as expected. No style there. Not even a new hat or dress among them. Just their Sunday best. Charles Creaney, Andrew’s colleague and best man, parked his almost new A40 under the churchyard wall somewhat out of sight of the twin clusters of onlookers by the gates. Andrew and the two ushers got out and the four of them strode off, two by two, heading for the church door without a glance at the women in aprons or the children fidgeting at their sides.

Moments later, a small handful of husbands and wives, some of them clearly from ‘across the water’, arrived by taxi. But there was no one among them to excite more than a brief speculation as to who they might be. Only the need to view the bride and to have the relevant news to pass on in the week ahead kept some of the women from going back to their abandoned Saturday morning chores.

Then, to their surprise and amazement, one of Loudan’s smaller limousines, polished so you could see yourself in its black bodywork, and bedecked with satin ribbons, drove up and slid gently to a halt. The driver opened the passenger door, touched his cap, offered his hand and a woman stepped out into the morning sunshine, a pleasant smile on her face. In the total silence that followed her arrival, she walked slowly towards the church door.

Salters Grange had its own version of ‘great style’, but they had never seen anything to equal the poise and presentation of Marie-Claude St Clair. Her couturier would have been charmed.

‘I think she’s a film star,’ said the first woman to find her voice. ‘She’s like somethin’ ye’d see on the front of Vogue.’

‘I’m sure I’ve seen her on our new telly.’

‘Young Helen Wiley said there was a French woman and her daughter staying at the Charlemont in Armagh. Would that be her?’

‘Where’s the daughter then?’

It was then that Loudan’s largest limousine appeared, driven by none other than Loudan himself. It drew to a halt in front of the gates. From the front passenger seat, a small man in immaculate morning dress stepped out, drew himself to his full height and waited attentively until first one lovely young woman and then another was assisted by the bowler-hatted Loudan to alight from the back seat.

Robert Lafarge bowed to them both and then offered his arm to the older one. So it was that, Cinderella no more, Clare Hamilton entered Grange Church on the arm of an eminent French banker, attended by a smiling young woman, whom she had cared for in her student days as an au pair on the sands at Deauville.

As the quips and comments flew back and forth across the gravel driveway it was clear the wait had not been in vain.

‘Did ye ever see the like of it? Was that necklace emeralds?’

‘How would I know? But I can tell you somethin’. That dress was such a fit you’d not buy that in some shop. An’ her that slim. Shure it must have been made for her, and those wee pearl beads round the skirt with the green and gold threadwork in-between to match the necklace.’

‘Was it silk or brocade? It was white all right, but there was green in it somewhere when she moved.’

‘Who was the wee man giving her away?’

‘They say that’s Robert Scott’s younger brother, the one that went to America an’ niver came back.’

‘Well, he doesn’t look like a Scott to me, that’s for sure. Sure he’s only knee high to a daisy. Robert was a fair-sized man in his day . . .’

While the women of Church Hill speculated on the past and future of Clare Hamilton, granddaughter of their former blacksmith, and of Andrew Richardson, sole surviving member of the once wealthy family who had lived in the parish since the seventeenth century and served in the Government since it was first set up 1921, the two individuals themselves stood together on the newly-replaced red carpet of the chancel and exchanged rings.

In the September sunshine filtering through the windows on the south aisle, the two rings gleamed just as they had when Clare found them in the dust and fluff under the wooden couch by the stove in the forge house. As the smaller one, once bound with human hair inside the larger one, was slipped on her finger, Clare feared for her mascara once again. She had found the rings a mere fortnight after her grandfather’s death. Then, she had lost both her grandfather and her home and had only a student room to call her own. Now, so much had been given back. Someone to love who loved her as dearly. A home that was theirs, Andrew’s family home, the place he had longed to be for most of his life.

With hands joined and heads bowed for the blessing, they both felt the touch of gold. The rings that had lain in the dust for a hundred years or more had emerged untarnished. Engraved on each of them were the initials EGB. It was a message of hope: in Irish, Erin Go Bragh; in English, Ireland Forever. Or better, the words the minister had used earlier . . . for as long as you both shall live.

Three (#ulink_916c1e66-f47d-5f25-877e-fce499381129)

The first day of January 1961 was dull and overcast in Armagh. Clare stood at the bedroom window and looked out across the lawn and over the curve of Drumsollen’s own low hill. Even under a grey sky the grass was a vibrant green and shaggy with growth. So far this winter there had been no severe weather and no snow at all, but spring was still a long time away.

After breakfast, Andrew stepped out into the early morning, left crumbs on the bird table and came back in again looking pleased. The wind was light and from the south-east. Echoing a phrase of her grandfather’s, he announced: ‘There’s no cold.’

‘Thank goodness for that,’ Clare laughed, as she carried their breakfast dishes to the draining board. ‘It’ll be draughty enough by the lake at Castledillon without a cold wind as well,’ she declared, as he shrugged his shoulders into his ancient waxed jacket and took his binoculars from a drawer under the work surface.

‘You’re sure you don’t mind me going, Clare? We were supposed to have a holiday today and you’re left with all the work,’ he added, a hint of anxiety creeping into his voice.

‘Oh Andrew, don’t be silly,’ she responded, giving him a hug, ‘We BOTH work so hard. You must take some time to do the things you want to do. You go and help with the count and get a look at the heronries. Another day when YOU are at work, I’ll go and see what Charlie’s added to his archive and talk local history with him. Fair shares for all, as your mother would say.’

They went upstairs and crossed the dim entrance hall where a small collection of ancestors still stared gloomily around them as if they had mislaid something they needed. A light breeze blew in their faces as Andrew opened the double glass doors into the porch, stepped through and swung the heavy outer door back into its daytime position. He put an arm round her shoulders as they walked across the stone terrace and down the broad sandstone steps to the driveway.

‘I’ll be back by twelve,’ he said, kissing her. ‘If you do start on Seven you can have my paintbrush ready. Don’t do too much while I’m gone.’

‘I promise. I’ll have your lunch ready. You’ll be starving. You always are. It’ll only be a toasted sandwich,’ she warned, as he opened the car door.

She went back indoors and ran upstairs to their bedroom. The kitchen had been warm from the Aga but the unheated bedroom was cold. Not as cold as her old bedroom at the forge house had been in winter but bad enough to make her grateful for the thick wool sweater she pulled out from a deep drawer below the handsome rosewood wardrobe.

She retrieved the hot water bottles from under the bedclothes, made the bed and took the bottles into the adjoining bathroom to empty them. The plasterwork was still drying out and the acres of white tile and gleaming taps made it feel even colder than the bedroom. She did a quick wipe of the hand basin and turned back gratefully into the room once used by The Missus.

Unlike the cold linoleum of the forge house, this room had always had the comfort and pleasure of a carpet but when they moved in they found it was so full of holes it would have to be replaced before they handed it over to the guests they hoped to welcome in April. Given the new bathroom, they had assumed this would be their best room until they realized the state of the carpet. She was still trying to decide what to do about it when their good friend Harry spotted a carpet when he was buying antique furniture in a house scheduled for demolition. He’d tipped the workmen to carry it to his van, brought it up to them and stayed to help them cut up old one up.

Harry said the ‘new’ carpet was probably older than the one they’d just carried to the compost heap. It was full of dust and dirty from the tramp of workmen’s feet but it showed very little signs of wear. They’d spent the best part of a warm, autumn weekend beating it, vacuuming it and sponging it. By the time they’d managed to lay it they were exhausted, but the carpet with its exotic birds and plants transformed the room. It even matched the faded curtains so well they decided they’d not replace them after all.

The bed made, the room tidied, Clare sat down at her dressing-table and began her make-up. For weeks after their brief honeymoon, she had applied only moisturizer, but as day followed day and she spent most of her time sorting, cleaning, or gloss painting, dressed in the oldest of old clothes, she began to feel something was wrong. The day before the surveyor came to estimate for the new central heating system she made up her mind. Cheap jeans from the cut-price shop in Portadown and well-worn shirts that could go in the machine would be fine for the job in hand, but she needed her go-to-work face to keep up spirits. To her surprise, that simple decision steadied her when she was presented with the enormity of the surveyor’s estimate next day.

She smiled to herself as she applied powder with a sable brush just as her dear friend Louise had taught her when they’d first shared an office in Paris. She missed Louise. She missed Paris. She missed that whole other world where she had been mostly happy and certainly successful. But now she and Andrew had each other and a life they could make together. You can’t have everything and she knew she had chosen what she really wanted.

She thought again of that sunlit October morning when the surveyor had presented his estimate. It brought back memories of all the meetings she’d sat through with Robert Lafarge, listening to companies putting forward plans, projects and requests for loans. She had smiled at him, given him coffee in the kitchen and negotiated the price. By suggesting the project be spread over the winter period when the company would be short of work, she’d secured a substantial discount. Andrew laughed when she told him. What delighted him was the thought of the unsuspecting surveyor coming face to face with a woman who had once been party to negotiating sums in seven figures.

By Christmas Eve, three of the five large bedrooms on the first floor had been freshened up or completely redecorated. Apart from the high ceilings and cornices, they’d done all the painting themselves. While Andrew was at work, Clare did as much of the brushwork as she could while supervising the installing of the two new bathrooms. When Andrew got home from work, he’d hang his suit over the bedroom chair, pull on his dungarees and take over her brush while she prepared a meal. Afterwards, they’d share the day’s news over coffee and then go back together to where he’d left off.

‘What do we tackle next?’ he asked, as they put up a holly wreath on the front door and looked forward to a few days holiday from paint.

‘Your guess is as good as mine,’ she said honestly. ‘A double brings in double the money and there’s only one set of bed linen to launder, but the single rooms will be cheaper and might attract more business. The five singles on the top floor could be very important. It all depends on who we manage to attract.’

‘Some of each, then?’ he suggested. ‘Doing a single would take us half the time it’s taken for the doubles. And we could do our own ceilings up there. Or rather I could do them.’

Clare pulled the bedroom door shut behind her and headed for the top floor, turned along the narrow corridor and stopped at a door with a dim and worn brass number seven. This was the largest of the upper bedrooms with a view over the garden. She stepped into the almost empty room and smiled to herself. It was in a much better state than she’d remembered.

Back in October, she and June had cleaned all the rooms in the house, getting rid of anything that could not be restored or reused. The windows on both floors had stood open for long, sunny days till finally the odour of damp and neglect had been overwhelmed by the faint perfume of lavender polish, the fresh smell of emulsion paint and the strange odour of the new rose-coloured carpet in two of the double bedrooms. Tomorrow, when June came back to work she must ask her who had slept in number seven when she had arrived straight from Grange School to begin her service at Drumsollen.

‘Dust sheets,’ she said aloud, as she tried to remember where the nearest pile of clean ones might be.

She looked more closely at the window frame. ‘And sandpaper,’ she added, wearily. You could paint over fine cracks but loose flakes like these came off on the brush. It was more trouble than it was worth trying to take a short cut.

It was just as she was about to go in search of her materials that a movement caught her eye, a glint, or a gleam from a vehicle just coming into view. She looked down in amazement and watched as a large black taxi drew up at the foot of the steps.

Could it possibly be someone who had misread their opening date? She’d been advertising in a whole variety of newspapers and magazines but she’d stressed: Springtime in the countryside. Special offers for our first guests from April the First. Bookings now accepted.

She peered down. She could see the driver perfectly well as he opened his door, strode round to the boot and took out a large and heavy suitcase, but she couldn’t get a good look at the figure emerging from the front passenger seat.

She ran along the top corridor and hurried downstairs. As she strode across the entrance hall, she caught a glimpse of a familiar figure through the glass panels of the porch door. It can’t be, she’s supposed to be in America, she said to herself, as she pulled them open. But there was no mistaking that red hair. It was Ginny, whom she hadn’t seen since they’d met in a hotel in Park Lane just over a year ago.

‘Clare, I’m sorry, I haven’t any money,’ Ginny said bleakly, as she walked round the vehicle, her face pale, her eyes red rimmed.

Clare threw her arms round her and hugged her. She could feel Ginny’s shoulders trembling ominously. Something was dreadfully wrong.

‘How much is it?’ Clare asked as steadily as she could manage, stepping back and smiling rather too brightly at the taxi man.

She was completely taken aback by the sum he named. She wasn’t sure she had that amount of money in the house, even with the reserve she still kept in Granda Scott’s old Bible.

‘Hold on a moment, will you. My handbag is probably upstairs,’ she said quickly. ‘Perhaps you could bring in my friend’s suitcase.’

‘Right y’ar,’ he replied agreeably, eyeing the well-swept steps and the heavy, white-painted front door.

Clare ran upstairs, emptied her handbag on to the bed. There was a wallet and a purse and some loose silver she’d dropped in when she was in a hurry. Putting it all together, she was still well short of the taxi fare even if she added the pound notes from the Bible and the bread man’s money from the kitchen drawer.

‘Where on earth has Ginny come from?’ she asked herself. Not Armagh certainly. Not since the railway had been closed down. And hardly Portadown to chalk up a bill like that. She stood breathless, a handful of pound notes in her hand and looked around the room as if an answer might lie there somewhere if only she could think of it.

‘Oh, thank goodness,’ she gasped, as she remembered Andrew’s wallet in the top drawer of his bedside table.

It was empty, as usual, but all was not lost. Not yet. She unzipped an inner compartment. There sat the balance of the fare. She ran back downstairs triumphant, delighted by the irony that the reserve she insisted he carry for emergencies was what had saved the situation for her.

‘Thank you very much, ma’am,’ the taxi driver said, as he folded the notes away into his back pocket. ‘I think this young lady had a rough crossing last night,’ he added kindly, nodding at Ginny, as he took a battered card from his pocket. ‘If I can be of service, give us a ring. Distance no object,’ he added, raising a hand in salute to them both as he drove off.

‘That smells good,’ said Andrew as he tramped into the kitchen and struggled out of his jacket. ‘I thought you said a toasted sandwich,’ he went on cheerfully. He ran his eye across the large wooden table. The end nearest the Aga sported a red checked cloth, three place settings and a bottle of wine. ‘Has Harry found us another carpet?’

Clare pushed a covered dish into the bottom oven, closed the door, straightened up and shook her head. His eyes flickered away from her face as he caught her sober look.

‘Don’t tell me the bailiff has arrived before we’ve even started?’ he said, trying to sound light.

Clare knew the tone only too well. He was going to be upset, but there was nothing for it but to tell him the truth.

‘Ginny arrived a couple of hours ago, by taxi. She came over on the Ulster Queen from Liverpool. Mark’s gone off with an American heiress.’

‘But they were supposed to be getting married last year,’ Andrew protested, as he dropped down into the nearest chair. ‘In June, wasn’t it? But his father was ill, so they had to postpone it. And then they weren’t able to come to our wedding, because of something else. Some big job came up in America and he couldn’t say “No” to it. Wasn’t that what she told us?’

Clare nodded. ‘I though it sounded funny at the time, but I can see it all now. Ginny tried to cover up for him. He lost a lot of money on the Stock Market. She said they couldn’t even afford her fare to come to the wedding. There was something came up in America, so she gave him all she had in the bank for his airfare. But nothing came of it. At least, that’s what he said when he came back. Apparently he thought she’d got a lot more money somewhere and he kept on asking her to help him out.’

‘But what made him think Ginny had money? The bit she gets from Grandfather Barbour’s shares goes down all the time. It’s hardly more than pocket money. She had a job, didn’t she? Did it pay well?’

‘I really don’t know. But remember she was living with your aunt in Knightsbridge while she had her plastic surgery. You know what a splendid house that is and how much you had to raise for the Clinic. It must have looked as if there was a lot of money around.’

‘So, what happened?’

‘She found a letter from this American woman. She thinks he left it lying around deliberately. They had a terrible row. He was planning to fly out next week. Told her he wasn’t cut out for poverty. Sorry and all that. They’d had some good times. But it was over.’

‘God Almighty! Where is she now?’

‘Asleep on our bed under a couple of rugs. There isn’t a bed made up. Anyway, ours is the only room that gets any heat from below. That’s why you chose it. Remember?’

Andrew leaned his arms on the table and dropped his head in his hands. For one moment, she thought he might be crying. He’d always been fond of Ginny. At one time, while she was in Paris, she’d thought there was something between them. Harry had said he’d seen them together quite often, but it turned out it was simply Andrew trying to get her back on her feet after Edward was killed.

Ginny had been driving when they were hit by the speeding lorry and his death had left emotional scars as well as the obvious physical ones. She’d needed a psychiatrist as well as a plastic surgeon. Andrew had raised the money by mortgaging their family home at Caledon which he’d inherited, but that had left him in serious financial difficulties because he couldn’t pay the death duties owed by the estate.

‘So what do we do?’ he asked steadily, lifting his head, a hint of a smile on his face. ‘There’s two of us this time, isn’t there?’

She nodded reassuringly, bent down and kissed his cold cheek and put her arm round his shoulders.

‘There might be some brandy left from that bottle Harry and Jessie gave you for your birthday,’ she said softly, ‘I seem to remember Ginny doesn’t like whiskey.’

‘I’ll go up and see,’ he said briskly, as he got to his feet and headed for the morning room, now their own small sitting-room.

Clare took a deep breath and felt herself relax. She’d been dreading telling him what had happened because she was so anxious about how he would react. He was always so responsible. Far too responsible. For the moment she would keep to herself the fact that Ginny thought she might be pregnant.

‘So you’re quite sure, Ginny?

‘Yes,’ she replied, beaming, as she closed the door behind her and sat down by the sitting-room fire. ‘I feel awful and I’ve got through half that packet of Tampax you gave me yesterday, but I don’t feel sick any more. I think I was just sick with worry, Clare. What would I have done without you and Andrew?’

‘Unhelpful speculation,’ Clare replied easily, as she closed her account book, got up from her desk and came over to sit opposite her in front of the comforting blaze. ‘I can’t say I’m not relieved, though we’d have managed somehow.’

‘I feel I’ve been such a fool. I’ve made such a mess of things after all the hard work Andrew put in to help me,’ she began, throwing out her hands in a typical Ginny manner.

Clare looked at her pale face and listened, comforted by the fact that she seemed so much herself again only a week after her flight from London. Exhausted she had been and still was, but the gestures, the eye movements, the toss of her head, all said this was the Ginny she had known since that wonderful summer she and Andrew had stayed with his cousins at The Lodge.

Since she’d taken up decorating herself, Clare often found herself thinking of that happy summer when they’d all painted the big sitting-room at Caledon. Ginny’s mother had made sketches of all four of them and Edward designed extraordinary games of skill for them to play in their free time. She still found herself thinking of Teddy and the long conversations they had about Irish history, which was his great passion.

He’d told her it was high time Ireland sorted out what actually happened from all the myths that had been invented. Whether you looked at 1690, or 1847, or 1916, there were facts to be had. What he wanted to do was put the record straight, one way or another, so that this group or that could not select their version of events and use them to justify the unjustifiable, nor to prop up corrupt or idle governments, North or South.

‘But I can’t impose on you and Andrew any longer, you’ve been more than kind. Besides, it’s not fair . . .’

Clare had been listening, but only with part of her mind, knowing what Ginny was likely to say and having her answer ready.

‘Ginny dear, you’ve only been here a week and you’ve been helping with jobs every day. Now, come on,’ she continued. ‘You’ve not moaned, you’ve been good company. You just had a lot of sleep to catch up on.’

Ginny smiled ruefully. ‘I haven’t even got the price of a packet of Tampax, never mind the bus fare to go and see Mother and Barney in Rostrevor.’

‘Well then, let me make you an offer,’ said Clare lightly. ‘Like Robert Lafarge, when he offered me my job, I will hope to make it irresistible. Part-time work for three months, starting tomorrow. Artistic director to the Managing Director of Drumsollen House Limited. Full board and lodging, one long weekend per month in Rostrevor, transport provided and five pounds per week. First month’s salary paid in advance so you can repay your friend who lent you the money for the train and boat. I’m the Managing Director and the artistic bit means you’ll have a lot of painting to do! How about it?’

‘Oh Clare, you can’t pay me as well as giving me full board and lodging. I should be paying you for that!’

‘Well, if it’ll make you feel any better, I hope to make a profit on the deal,’ Clare said, looking as sober as she could manage.

‘But how can you possibly manage that?’

‘Well, if you say “Yes” I’ll tell you.’

‘You’re not just being kind?’

‘No. Can’t afford to be,’ Clare responded honestly. ‘I’m supposed to be good with money and I can help you with yours, but I can’t start being kind enough to help you manage your money rather better if you haven’t got any money to manage in the first place, now, can I?’

Ginny laughed and threw out her hands in a gesture of complete defeat. ‘All right. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Now tell me how you are going to make a profit on this outrageously generous offer.’

‘Well, I’ve managed to do some “sharp deals” as one of my American clients used to say, but buying sharp means a lot of research to find what we need at special prices. If I had someone here who could carry on with my painting efforts and keep an eye on workmen when we have them in, then I’d be free to hunt for all the stuff we need, like bed linen and towels, china, glass and so on. I’d like to check out these new Cash and Carry places for basics, but I can’t leave June on her own all the time, especially when there might be bookings coming in and we’ve still got to get the place up and running for April.’

‘Right. You’re on. If you can tackle something you’ve never done before, then why can’t I? Even if I have been an idiot, I can still do all sorts of useful things when I remember what they are,’ she added dryly.

‘That’s got that settled then.’

Clare paused, suddenly uncertain that what she wanted to say next was quite the right thing.

‘What is it, Clare? I know that look of yours. You’re thinking.’

‘Yes, you’re right. I am, but about something quite different,’ she began slowly. ‘I keep looking at your face. You’re still very pale, but that’s what makes it so wonderful. Even when you are so pale and have no make-up on at all, I can’t see any of your scars, even though I know exactly where they are.’

Four (#ulink_2a9f00fc-e09f-55cc-8de7-84aaf0eac94e)

The small, pebble-dashed bungalow overlooking the road from Armagh to Loughgall and the local landmark of Riley’s Rocks had been part of Clare’s life for as long as she could remember. As a child, hand in hand with her mother or father, she’d walked past often on a Sunday afternoon to visit Granda and Granny Scott at the forge. She could still remember how she had gazed up the steep slope and said proudly, ‘That’s where Kate and Charlie Running live, isn’t it?’ She had known the names of all the people who lived in the scattered houses beyond the Mill Row and even the names of those who lived out of sight at the ends of lanes that dipped down under the railway bridge or curved round the low hill on which the Runnings’ bungalow was perched.

Later, after she had lost both her parents and had come to live with her grandfather, she’d cycled the road each day on her way to school in Armagh. Sometimes, on days as hot as today, she would stop at the rusting iron pump opposite the bungalow, to drink the cold water that came gushing up from deep underground. It certainly gushed up when Jessie was with her. Jessie did nothing if not whole-heartedly and when she put her hand to the pump, Clare was sure to end up with a wet gymslip or splashed shoes.

Today, on the loveliest of June days, the sky a perfect blue, the heat tempered by a hint of a breeze, Clare parked Andrew’s ancient bicycle on the hedge bank beside the gate her grandfather had made for his old friend, took a cake tin from her front basket and prepared to climb the two flights of steps to his front door.

All morning she’d looked forward to visiting Charlie, a pleasant walk of about a mile if one counted in the long driveway of Drumsollen, but by the time she’d dealt with checking out their overnight guests, sorted the paperwork from the morning’s deliveries and answered a scatter of telephone enquiries, she knew she was going to be late. While Charlie had such a relaxed attitude to time he often forgot what day it was, nevertheless, she felt sad that events had cut into her time with him.

Charlie did not suffer from the absent-mindedness that was sometimes a feature of age, nor did he have the habit of looking the other way from what he would prefer not to see. Charlie saw so much he was perpetually preoccupied, thinking through some item he had read or teasing out some puzzle he’d encountered in his formidable reading programme. Given how often his mind was elsewhere, Clare took it as a great compliment that he never forgot when she was coming. Not only did he have the kettle boiling, but he always cleared away enough of his books, papers, maps and sketches to leave them a seat each in his small front room.

‘Well now, tell me all your news, Clare. How is that good man of yours? I hear he’s been down in Fermanagh again. Did he prosper, as the saying is?’

Clare laughed. Not only did Charlie know everyone for miles around, but he knew everything going on in the entire area as well. When she’d last seen him a couple of weeks earlier, the complicated land dispute in Fermanagh involving one of Charles and Andrew’s biggest clients had not yet arisen.

‘Well, Charlie, as you well know, Andrew hasn’t much time for litigation or the criminal side, but he’s in his element when it’s land. As long as he has a good dispute, preferably with boundaries, so he can get his feet on the ground, he’s happy. I wish there was more work of that kind,’ she ended sadly.

‘Too soon for him to give up being a solicitor and take to farming?’

‘’Fraid so. I can’t give him much hope till we’ve a year behind us, or more likely two. It has gone well though, so far, as I’m sure you’ve heard. But we can’t think of buying land till we’ve repaid all the loans for the structural work,’ she admitted honestly. ‘The trouble is, the more we do, the more we find to do. We had to have the gutters cleared and the bad bits replaced and one of the men who’d been up on the roof told us the west chimney is in a bad way. How bad it is we don’t know yet. We’re just keeping our fingers crossed.’

‘Aye, I can see that would be a worry. But I did hear you were fully booked in May.’

‘Yes indeed,’ she laughed, as he filled the teapot from his electric kettle and took the lid off the cake tin. ‘Full up in May and bookings coming in all the time. The local papers did us proud with that piece about Armagh in apple blossom time. That was your idea. But there’s more good news. Besides visitors, we’ve a couple of surveyors booked for the whole of June. I don’t know how they got to hear of us but more long stays like that would be just great. Steady income and less laundry,’ she added, making a face.

‘Surveyors now?’ he nodded, as he laid out the cups and saucers methodically. ‘Would that be a new factory or suchlike?’

‘Yes, it’s an American company. Textiles. I think it’s probably synthetics. Steve and Tom aren’t American, they’re English, so they’re not really much interested in the end product. In fact, to be honest, though they’re very friendly, I think they’re only interested in doing the job, watching TV in the evening and getting back home to their wives.’

‘So you got the TV then?’ he demanded, raising his shaggy eyebrows.

‘I got two actually,’ she confessed, only too aware of Charlie’s thesis that television prevented conversation and was undermining the quality of local visiting. ‘The sixteen inch is in the old smoking room for the use of guests. I told you we’d have to have that. But I was in luck. Apparently fourteen inch ones are out of date already, so I got one cheap and we have that in our sitting-room. Mind you it’s much bulkier than the sixteen inch and it’s a tight squeeze with my desk and the typewriter and the office stuff we need in there as well, but we’ve been so busy we were beginning to think we’d no idea what was going on in the world at all. Not even what’s going on here in Northern Ireland.’

‘Not a lot, Clare, not a lot. I can tell you you’re not missing much, though I have to say the unemployment has dropped a bit and there’s a few more houses going up,’ he said, between mouthfuls of cake. ‘There’ll not be much happening unless your man Brookeborough exerts himself. And that’s not very likely. Sure, it’s time he was retiring. The man’s a few years younger than I am but I can’t say the same for his ideas. We need someone with a new perspective and some notion of how to create jobs and a whole different attitude to people forby. Sure, the ship building’s going down the plughole and the linen industry isn’t far behind. Emigration is way up again and there’s desperate poverty, and not just in Belfast and Derry. Even the small farmers are laying off men and bringing in tractors . . .’