The Belfast Girl at O’Dara Cottage

The Belfast Girl at O’Dara Cottage

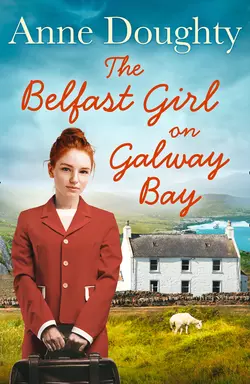

Anne Doughty

Readers LOVE Anne Doughty:‘I love all the books from this author’‘beautifully written’‘would recommend to everyone’‘Fabulous story, couldn't put it down!’‘Looking forward to the next one.’Prepare to be spirited away to rural Ireland in this stunning new saga series from Anne Doughty.

ANNE DOUGHTY is the author of A Few Late Roses, which was nominated for the longlist of the Irish Times Literature Prizes. Born in Armagh, she was educated at Armagh Girls’ High School and Queen’s University, Belfast. She has since lived in Belfast with her husband.

Also by Anne Doughty (#u8888f6c1-5ca0-5ee0-8bd2-f3e958898e78)

The Girl From Galloway

Copyright (#u8888f6c1-5ca0-5ee0-8bd2-f3e958898e78)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Anne Doughty 2019

Anne Doughty asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008328801

Praise for Anne Doughty (#u8888f6c1-5ca0-5ee0-8bd2-f3e958898e78)

‘This book was immensely readable, I just couldn’t put it down’

‘An adventure story which lifts the spirit’

‘I have read all of Anne’s books – I have thoroughly enjoyed each and every one of them’

‘Anne is a true wordsmith and manages to both excite the reader whilst transporting them to another time and another world entirely’

‘A true Irish classic’

‘Anne’s writing makes you care about each character, even the minor ones’

For Peter

Contents

Cover (#u3b19d4a7-9cfa-5db6-9fe2-00b29fc737ff)

About the Author (#uca7d8347-f312-5c68-87b2-18680c4170d5)

Also by Anne Doughty (#u231fc832-bb0b-504c-b53d-380b5b529ea7)

Title Page (#u0315f9c3-0e1b-5e8d-9fa3-ad3cae553fd3)

Copyright (#u1605b2ec-41d9-5eb0-a68e-9c8dd833b92b)

Praise (#u46fe87bd-0216-5bcb-9119-c926a472007b)

Dedication (#ud535762f-44a6-5035-b0d8-67ac828187e9)

Chapter 1 (#u91f27f91-7ec6-580c-8cf2-4a37168ff58d)

Chapter 2 (#ue80a10c8-d981-5778-ac20-210124797614)

Chapter 3 (#u248c992c-0d9b-579a-968f-7056bde0eb3c)

Chapter 4 (#u00b06536-e782-5f70-ab68-8cfdb868fc61)

Chapter 5 (#ubc97aa99-beab-5227-9c11-c5db3a2a81fe)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Two (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_f486e88f-db8b-53f8-8e42-14a94c73d88b)

SEPTEMBER 1960

As the ten o’clock bus to Lisdoonvarna throbbed its way northwards, my spirits rose so sharply I found it almost impossible to sit still. Brilliant light spilled across the rich green fields, whitewashed cottages dazzled against the brilliant sky and whenever we stopped, people in Sunday clothes climbed up the steep steps, greeted the driver by name and settled down to chat with the other passengers.

How incredibly different my train journey from Dublin to Limerick. Under the overcast sky of a rain-sodden evening, we steamed westwards, stopping at innumerable shabby stations with hardly a soul in sight. I caught glimpses of straggling villages and empty twisting lanes, weaving their way between deserted fields. The further we went, the more I felt the heart of Ireland a lonely place. It was so full of a sad desolation that I longed for the familiar busy streets of the red brick city I had left two hundred miles away.

Through the dirt-streaked windows of the rattling bus, I took in every detail of a landscape that delighted me. Flourishing fuchsia hedges, bright with red tassels, leaned over tumbled stone walls. Cats dozed on sunny windowsills. A dog lay asleep in the middle of the road, so that the bus driver had to sound his horn, slow down, and wait until he moved. In the untidy farmyards, littered with bits of old machinery, empty barrels and bales of straw, hens scratched in the dust clucking to themselves, while beyond, in the long lush grass of the large fields, cattle grazed. They looked as if they came straight out of the box which held the model farm I played with at primary school.

Some hillsides were decorated with sheep, scattered like polka dots on a billowing skirt. There were stretches of bog seamed with stony paths, the new, late-summer grass splashed a vivid green against the dark, regular peat stacks and the purple swathes of heather. I imagined myself making a film to show to my family on a long winter’s evening but this country had been excluded from their list. An unapproved country, like an unapproved road, I thought suddenly as we stopped in Ennistymon, in a wide street full of small shops liberally interspersed with public houses.

An hour later, in the Square in Lisdoonvarna, it was my turn to weave my way through the crowd of people waiting to meet the bus. A short distance beyond the rusting vans, the ancient taxi and the ponies and traps by the bus stop, abandoned rather than parked, I spotted a row of summer seats under the windows of a large hotel. They were all unoccupied, so I went and sat down. It was such a relief to have a seat that didn’t shake and vibrate every time the driver changed gear.

It was now after one o’clock. As I watched, the bus disappeared in a cloud of fumes, followed at intervals by the other vehicles. In a few moments the Square was completely deserted. I looked around me. Directly opposite was a war memorial, set within a solidly built stone enclosure. The walls were hooped with railings and pierced with silver-painted gates, hung between solid pillars. Each sturdy pillar was capped by a large, flat flagstone, white with bird droppings. Within the enclosure, grass grew untidily around young trees and shrubs already touched with the tints of autumn. Dockens pushed their rusty spikes through the locked gates and dropped their seeds among the sweet papers and ice-cream wrappers drifted against the wall.

Except for the clatter of cutlery in the hotel behind me and the running commentary of the sparrows bathing in the dust nearby, all was quiet. Nothing moved except a worn-looking ginger dog of no specific breed. He trotted purposefully across the red and cream frontage of the Greyhound Bar, lifted his leg against a stand of beachballs outside the shop next door, and disappeared into the open doorway of a house with large, staring sash windows. A faded notice propped against an enormous dark-leaved plant in the downstairs window said ‘Bed and Breakfast’.

‘What do I do now?’ I asked myself.

Just at that moment, the ancient taxi I’d seen collecting passengers from the bus came back into the Square. To my surprise, the driver went round the completely deserted space twice before stopping his vehicle almost in front of me. He got out awkwardly, a tall, angular man in a battered soft hat, looked around him furtively and began to move towards me.

I concentrated on the buildings straight ahead of me, a cream and green guest-house called ‘Inisfail’, a medical hall, a bar, a grocer’s, and a road leading out of town, signposted ‘Cliffs of Moher’ and ‘Public Conveniences’. The bar and the grocer’s were part of a much larger building that occupied almost all one side of the Square and extended along the road towards the cliffs and conveniences as well. Against the cream and brown of its walls and woodwork, ‘Delargy’s Hotel’ stood out in large, black letters.

‘Good day, miss. It’s a fine day after all for your visit.’

He was standing before me, touching his hand to the shapeless item of headgear he’d pushed back on his shiny, pink forehead. The sleeves and legs of his crumpled brown suit were too short for his build and his hands and feet projected as if they were trying to get out. In contrast, the fullness of his trousers had been gathered up with a leather belt and his jacket hung in folds like a short cloak.

‘Ye’ll be waitin’ for the car from the hotel, miss. Shure, bad luck till them, they’ve kept you waitin’,’ he said indignantly.

I shook my head. ‘No,’ I replied. ‘I’m not staying at a hotel.’

‘Ah no . . . no . . . yer not.’

He nodded wisely to himself as if the fact that I was not staying at a hotel was plain to be seen. He had merely managed to overlook it. He sat himself down at the far end of my summer seat and for some minutes we studied the stonework of the war memorial in front of us as if the manner of its construction were a matter of some importance to us both.

He turned and smiled again. His eyes were a light, watery blue, his teeth irregular and stained with tobacco.

‘Have yer friends been delayed d’ye think? Maybe they’ve had a pumpture,’ he suggested.

He seemed quite delighted with himself for having seen the solution to my problem and he waited hopefully for my reply. It had already dawned on me that I wasn’t going to go on sitting here in peace if I didn’t give him some account of myself.

I knew from experience that country people have a habit of curiosity based on self-preservation. Strangers create unease until they have been labelled and placed. And he couldn’t place me. In his world people who travel on buses and have suitcases are to be met. I had a suitcase, I had travelled on a bus, but I had not been met. I glanced at him as he pushed his hat back further and scratched his head.

‘I’m just having a rest before my lunch,’ I said, hoping to put him out of his misery. ‘I’m going on to Lisnasharragh this afternoon,’ I explained easily.

‘Ah yes, Lisnasharragh.’

Again, he nodded wisely, but the way he pronounced the name produced instant panic. He’d said it as if he had never heard of it before.

‘Ye’ll be having a holiday there, I suppose?’ he said brightly.

I was slow to reply for I was already wondering what on earth I was going to do if Lisnasharragh had disappeared. It had been there in 1929 all right. On the most recent map I’d been able to get hold of, the houses referred to in the 1929 study I’d found were clearly shown, but that didn’t mean they were inhabited now in 1960. Lisnasharragh might be one more village where everyone had died, moved away, or emigrated to America. There had been no way of finding out before I left Belfast.

‘No, I’m not on holiday,’ I began at last ‘I’m going to Lisnasharragh to do a study of the area,’ I explained patiently.

All I wanted was for him to go away and leave me in peace to think what I was going to do about this new problem.

‘Are ye, bedad?’

His small eyes blinked rapidly and he leaned forward to peer at me more closely.

‘And yer going to write about it all, I suppose, eh?’

He laughed good-humouredly as if he had made a little joke at my expense.

‘Well. . . yes . . . I suppose I am,’ I admitted reluctantly.

He leapt to his feet so quickly he made me jump. Then he grabbed my suitcase, stuck out his free hand towards me and pumped my arm vigorously.

‘Michael Feely at your service, miss. There’s no one knows more about this place than I do, the hotels, the waters, the scenery, everything. I’ll be happy to assist you in your writings.’

He tossed my heavy suitcase into his taxi as if it were an overnight bag and opened the rear door for me with a flourish.

‘You’ll be wantin’ yer lunch now, miss,’ he said firmly. ‘I’ll take you direct to the Mount. The Mount is the finest hotel in Lisdoon, even if it isn’t the largest. All the guests are personally supervised by the owner and guided tours of both scenery and antiquities are arranged on the premises for both large and small parties, with no extra charge for booking.’

‘Thank you, Mr Feely,’ I said weakly, as he closed the door behind me.

As he’d taken my suitcase, I couldn’t see I had much option. I settled back on the worn leather seat, glanced up at the rear-view mirror and saw his pink face wreathed in smiles. He looked exactly like someone who has struck oil in their own back garden.

The Mount was a large, dilapidated house set in an enormous, unkempt garden where clumps of palm trees and a pair of recumbent lions with weather-worn faces suggested a former glory. He parked the taxi at the back of the house between a row of overflowing dustbins and a newish cement mixer, picked up my case, marched me round to the front entrance, across a gloomy hall and into a dining room full of the smell of cabbage and the debris of lunch.

He summoned a pale girl in a skimpy black dress to remove the greasy plates and uneaten vegetables from a table by the window, pulled out my chair for me and left me blinking in the strong sunlight that poured through the tall, uncurtained windows.

Across the uneven terrace the lions stared unseeing at groups of priests who strolled on the lawns or lounged in deckchairs. Against a background of daisies and dandelions or of striped canvas, their formal black suits looked just as out of place as the bamboo thicket and the Japanese pagoda I could see on the far side of the garden.

My soup arrived. I stared at the brightly coloured bits of dehydrated vegetable floating in the tepid liquid and recognised it immediately. Knorr Swiss Spring Vegetable. One of the many packets my mother uses ‘for handiness’. But she does mix it with cold water and leaves it to simmer on a low heat while she’s downstairs in the shop. My helping had not been so fortunate. It was full of undissolved lumps. I stirred it with my spoon and wondered what the chances were that Feely would return to supervise me personally while I ate it.

Fortunately he didn’t. My untouched bowl was removed without comment. I wasn’t expecting much of the main course, so I wasn’t too disappointed. Underneath a lake of thick gravy, overlooked by alternate rounded domes of mashed potatoes and mashed carrots, I found a layer of metamorphosed beef. It was tough and tasteless just like it is at home, but I did my best with it. The vegetables weren’t too bad and my plate with its pile of gristle was safely back in the kitchen without Feely having reappeared.

I looked around the shabby dining room as I tackled the large helping of prunes and custard that followed. There were now two very young girls, dressed identically in skimpy black skirts, crumpled white blouses and ankle socks, beginning to lay the tables from which lunch had just been cleared. Out of the corner of my eye I watched them brush away crumbs and place paper centrepieces over the stiffly starched cloths. The table next to mine was beyond such treatment. Well-anointed with gravy, the heavy fabric was dragged off unceremoniously to reveal underneath a worn and battered surface ringed with the pale marks of innumerable overflowing drinks.

I smiled to myself and thought of Ben, my oldest friend. How many rings had we wiped up from the oak-finish Formica of the Rosetta Lounge Bar in these last two months? He would miss me tomorrow when there was only Keith in the kitchen and no one to help him with the cleaning and the serving. The thought of doing the Rosetta job on my own appalled me. If it hadn’t been for Ben the whole episode would have been grim indeed.

‘Hi, Lizzie, what are you doing up so early?’

He greeted me as I stood disconsolately at the bus stop outside the Curzon Cinema waiting for a Cregagh bus. It was the first Monday in July, seven-thirty in the morning. I was sleepy and cross, my period had just started, and I was trying to convince myself it wasn’t all a horrible mistake.

‘Holiday job up in Cregagh.’

He looked me up and down, took in my black skirt, my surviving white school blouse and the black indoor shoes I’d worn at Victoria.

‘It wouldn’t by any chance be the Rosetta, would it?’ he asked, as he squinted down the road at an approaching double decker.

‘How did you guess?’

‘Read the same advertisement. That’s where I’m for too,’ he announced, grinning broadly. ‘When I get my scooter back, I can give you a lift. Save you a lot in bus fares.’

I could see how delighted he was and the thought of his company was a real tonic, but something was niggling at the back of my mind.

‘But weren’t you going to Spalding for the peas, Ben?’ I asked uneasily. ‘It’s far better paid.’

‘You’re right there,’ he nodded. ‘But Mum’s not well again,’ he said slowly. ‘She won’t see a specialist unless I keep on at her. You know what she’s like. So I cancelled and the Rosetta was all I could get. It could be worse,’ he grinned. ‘It could be the conveniences in Shaftesbury Square.’

When the bus came, we climbed the stairs and went right to the front so we could look into the branches of the trees the way we always did when we were little.

Tinker, tailor, soldier, sailor, rich man, poor man, I counted silently, as I scraped up the last of my custard, but before the prune stones had told me who I was to marry, a cup of coffee descended in front of me and my future disappeared before my eyes.

The coffee was real coffee, freshly made Cona with a tiny carton of cream parked in the saucer. I could hardly believe it. I sipped slowly and went on watching the pale, dark-haired girls as they humped battered metal containers full of cutlery from table to table. At least we didn’t have that to do at the Rosetta. The restaurant only opened in the evenings, at lunchtime we only served bar food, sandwiches and things in a basket. But there were other jobs just as boring as the endless laying of tables.

Every morning at eight o’clock, we started on the mess the evening staff had to leave so they could run for the last bus from the nearby terminus. Stacks of dishes, glasses and ashtrays from the bar. After that the staircases and loos to sweep and mop before we started on lunches. That first day, the manageress set us to work separately and by four o’clock when we staggered off to the bus stop we were not only bored but absolutely exhausted. Next morning Ben had an idea.

‘C’mon, Lizzie, let’s do it all together. I’ve worked out a system.’

‘But what’ll we say if she catches us?’

‘Wait and see,’ he grinned.

I knew there was no use pressing him, because he’s good at keeping secrets. You could sooner get blood out of a stone.

We were standing under one of the Egyptian kings who provide the decor at the Rosetta with Ben holding a table on its side and me vacuuming under it, when she appeared.

‘I thought you were supposed to be doing the washing-up, Ben,’ she said crossly.

‘Oh, that’s all finished,’ said Ben cheerily. ‘But you were losing money on it.’

‘What? What d’you mean?’

She wrinkled up her brow, peered into the kitchen behind the bar, and saw it was all perfectly clean and tidy.

‘Time and motion,’ he said easily. ‘I did you a complete survey yesterday. No charge of course, it’s just a hobby of mine, but when I processed the results last night I really was shocked. . .’

He put the table aside, pulled out a chair and motioned to her to sit down.

‘You must never stand while talking to employees, it’s bad for your veins. Senior staff must safeguard their well-being, it’s one of the first principles of efficient management.’

Standing there with the vacuum cleaner in one hand and a clean duster in the other, I had an awful job keeping my face straight. Ben is a medical student, so he does know about veins; it was the time and motion study that really got me. But it worked a charm. After that, she left us to do the jobs in whatever way we liked. Often, we even enjoyed ourselves.

As I finished my coffee I began to wonder how much my lunch was going to cost. Just because it wasn’t very nice didn’t mean it couldn’t be expensive. Then there would be the taxi fare to Lisnasharragh and a night in a hotel if I’d got it wrong. Suddenly, I felt very much on my own, a solitary figure in an empty dining room. Ben and the Rosetta and the familiar things in my life were all a very long way away. I was painfully aware of being a stranger in a strange place.

It was some time before Feely breezed in. He ignored my unease about not having had the bill, said the car was at the door and he was all ready to take me to Lisnasharragh. Which way did I want to go?

According to my map, there was only one possible way. I took a deep breath and explained carefully that the village lay at least five miles away on the coast road to the Cliffs of Moher. But it might be as much as six.

I might as well not have bothered. As soon as we were out of town, he dropped to a crawl, following the thin, tarmacked strip of road between wide, windswept stretches of bog. Nothing I said had the slightest effect upon him and we continued to crawl along, furlong by furlong, through totally unfamiliar territory. For once in my life, I was more anxious about the distance itself than about the hole this luxurious journey would be making in my small budget. As each mile clicked up on the milometer, I became more agitated. Once it showed seven miles, I would know I’d got it wrong. Either I had misread my map, or worse still, Lisnasharragh no longer existed.

As we approached the five-mile mark, the bog ended abruptly. On my left the land rose sharply and great outcrops of rock dominated the small fields. On the other side of the road, the much larger fields dropped away into broad rolling country with limestone hills in the distance. Bare of any trace of vegetation, the Hills of Burren stood outlined grey-white against the blue of the sky.

We turned a corner and there ahead of us was the sea. Sparkling in the sun across the vast distance to the horizon, it broke in great lazy rollers over a black, rocky island about a mile from the shore. Beyond this island, in the dazzle of light, like the backs of three enormous whales travelling in convoy, were the Aran islands. Inisheer, Inishman and Inishmore.

My heart leapt in sheer delight. For weeks now these names had haunted me with their magic. Now the islands themselves were in front of me. Nothing lay between me and them except the silver space of the sea. As if a window in my mind had been thrown open, I felt I could reach out and touch something that had been shut away from me. My anxieties were forgotten. The islands were an omen. Now I had found them all would be well.

The road began to climb and as it did, I crossed an invisible boundary onto the map I carried in my mind. I knew exactly where I was.

‘It’s not far now, Mr Feely,’ I said quickly, making no attempt to conceal my relief. ‘Down the hill and over the stream. There’s a clump of trees to the right and then a long pull up. Maybe we could stop at the top.’

‘Ah, shure you’ve been pulling my leg, miss. Aren’t you the sly one and you knows Lisara as well as I do.’

Feely turned to me and laughed. He seemed almost as pleased about finding Lisara as I was. Even the idea that I’d played a trick on him didn’t appear to bother him.

‘Oh no, Mr Feely, I haven’t been here before, truly,’ I assured him as I studied the road ahead. I wished he would look at it himself just occasionally.

‘Ye haven’t?’

‘No.’ I shook my head emphatically. ‘Not at all.’

‘Not at all,’ he repeated feebly.

To my great relief, he turned away and corrected our wavering course. I stared around me in disbelief.

For the last two weeks of the summer term, I had spent every day in the departmental library copying maps and reading monographs. In the main library I had found reports from the Land Commissioners and the Congested Districts Board. They were so heavy I could barely carry them down from the stack. I had ploughed my way through acres of fine print. Now, it all seemed irrelevant. Nothing I had done had prepared me for the sheer delight that overwhelmed me as I moved into this unknown country on the edge of the world.

Months ago, when the whole question of theses was being discussed, something told me I had to come here. I’d managed to cobble up some good reasons for coming but it had never occurred to me to think how I might feel when I actually arrived.

It wasn’t enough to say that it was beautiful, though I thought the prospect of the islands the most wonderful sight I’d ever seen. It was something much less tangible. However hard I struggled, I could find no words to describe what I felt, not even inside my head.

‘Mr Feely, could you stop round the next bend. There’s a cottage on the left with a lane down the side of it. We could park there while I have a quick look round.’

As we turned the corner and pulled into the lane, my spirits rose yet further. The cottage was not only trim and neat but it had pale patches in the thatch where it had been mended quite recently. Before we had even bumped to a halt, a young woman appeared at the half-door to see who had turned into the lane. I went and asked her if she could help me at all, told her I was looking for somewhere to stay and assured her I would be no trouble.

‘And I’m shure you wouldn’t, miss.’

She smiled weakly and fingered a straggling lock of dark hair. She looked strained and tired, her face almost haggard as she stood thinking. She couldn’t be much older than I was.

‘Shure I’d be glad to have you here, miss, but I’m thinkin’ you’d not have much peace for yer work with four wee’ ans. Is it the Irish yer learnin’?’

As soon as she opened the half-door a chicken made a dive for the house. As she shooed it away it was clear there would soon be another wee’ an to care for.

‘I’m thinkin’, miss, where ye’d be best off. Is it Lisara ye want?’

‘Yes, indeed, but anywhere in Lisara will do.’

It was only as I pronounced the word ‘Lisara’ for the first time that I realised Lisnasharragh no longer existed. Perhaps it never had existed, except as a name some ordnance surveyor had put in the wrong place, or one he’d found that the local people never used. Whatever the story, Lisara was my Lisnasharragh, alive and well, and exactly where it should be.

‘Well, I think ye might try Mary O’Dara at the tap o’ the hill. She’s a good soul an’ they’ve the room now for all her family’s gone. Tell her Mary Kane sent ye.’

She leaned against the whitewashed wall of the cottage, weary with the effort of coming out to talk to me.

‘I’ll do that right away,’ I said quickly. ‘If she can have me, perhaps I could come down and talk to you about Lisara.’

‘Indeed you’d be welcome,’ she said warmly. ‘We don’t have much comp’ny.’

I thanked her and turned back towards the car. To my surprise, she followed me into the bumpy lane.

‘I’ll see ye again, miss, won’t I?’

‘You will, you will indeed. Goodbye for now.’

Feely was looking gloomy and when I asked him if we could go up the hill to O’Dara’s he just nodded and drove off. I wondered if I’d said something I shouldn’t have.

O’Dara’s cottage was just as trim and neat as Mary Kane’s, but there was a small garden in front of it. A huge pink hydrangea was covered with blooms and there were plants in pots and empty food tins on the green-painted sills of the small windows. Sitting outside, smoking a pipe, was a small, wiry little man with blue eyes, a stubbly chin, and the most striking pink and mauve tie I have ever seen.

‘Good day, is it Mr O’Dara?’ I asked.

‘It is indeed, miss, the same.’

For all my flat-heeled shoes and barely reaching five foot three, I found myself looking down at his wrinkled and sunburnt face when he got to his feet.

‘I’m sorry to disturb your nice quiet smoke, Mr O’Dara, but I wonder, could I have a word with Mrs O’Dara? Mrs Kane sent me.’

‘Ah, Mary-at-the-foot-of-the-hill.’

He turned towards the doorway and raised his voice slightly. ‘Mary, there’s a young lady to see you.’

Mary O’Dara came to the door slowly. She looked puzzled and distressed. Her face was blotchy and she had a crumpled up hanky in one hand. I wondered if I should go away again but I could hardly do that when I’d just asked to speak to her.

Her eyes were a deep, dark brown, and despite her distress, she looked straight at me as I explained what I wanted. When I finished, she hesitated, fumbled with the handkerchief and blew her nose.

‘You’d be welcome, miss, but I’m all through myself. My daughter’s away back to Amerikay, this mornin’, with the childer an I don’ know whin I’ll see the poor soul again.’

She rubbed her eyes and looked up at me. ‘Shure ye’ve come a long ways from home yerself, miss.’

‘Yes, but not as far as America. It must be awful, saying goodbye when it’s so very far away.’ I paused, saddened by her distress. ‘Perhaps she’ll not be long till she’s back.’

I heard myself speak the words and wondered where they’d come from. Then I remembered. Uncle Albert, my father’s eldest brother. ‘Don’t be long till you’re back, Elizabeth,’ was what he always said to me, when he took me to the bus after I’d been to visit him in his cottage outside Keady.

It was also what everyone said to the uncles and aunts and cousins who appeared every summer from Toronto and Calgary and Vancouver, Virginia and Indiana, Sydney and Darwin. Everybody I knew in the Armagh countryside had relatives in America or Australia.

‘Indeed she won’t, miss. Bridget’ll not forget us,’ said her husband energetically. ‘Come on now, Mary, dry your eyes and don’t keep the young lady standin’ here.’

But Mary had already dried her eyes.

‘Would you drink a cup o’ tea, miss?’

‘I’d love a cup of tea, Mrs O’Dara, thank you, but Mr Feely is waiting for me. I’ll have to go back to Lisdoonvarna, if I can’t find anywhere to stay in Lisara.’

‘Ah, shure they’d soak ye in Lisdoonvarna in the hotels,’ said Mr O’Dara fiercely. He looked meaningfully at his wife.

‘That’s for shure, Paddy. But the young lady may not be used to backward places like this.’

‘Oh yes, I am, Mrs O’Dara. My Uncle Albert’s cottage was just like this and I used to be so happy there. Perhaps I’m backward too.’

Maybe there was something in the way I said it, or maybe it was my northern accent, but whatever it was, they both laughed. Mary O’Dara had a most lovely, gentle face once she stopped looking so sad.

‘Away and tell Mr Feely ye’ll be stayin’, miss.’

She crossed the smooth flagstones of the big kitchen and took a blackened kettle from the back of the stove.

‘Paddy, help the young lady with her case.’

She bent towards an enamel bucket to fill the kettle so quickly she didn’t see Paddy clicking his heels and touching his forelock. He turned to me with a broad grin as we went out.

‘God bless you, miss, ye couldn’t ‘ive come at a better time.’

Feely sprang to life as Paddy lifted my case from the luggage platform.

‘Are ye goin’ to stay a day or two, miss?’

‘I am indeed, Mr Feely. Two or three weeks, actually.’

‘Are ye, begob?’

I was sure I’d told him I needed to stay several weeks, but he looked as if the news was a complete surprise to him. Paddy had disappeared into the cottage with my case, so I set about thanking him for his help.

‘I don’t know what I’d have done without you, Mr Feely,’ I ended up, as I pulled my purse from my jacket pocket and hoped I wouldn’t have to go to my suitcase for a pound note.

‘Ah no, miss, no,’ he protested, waving aside my gesture. ‘We’ll see to that another time. I’ll see ye again, won’t I?’

He started the engine and looked at me warily.

‘Oh yes, I’ll be in Lisdoonvarna often, I’m sure. I’ll look out for you. I know where to find you, don’t I?’

‘Oh you do, you do indeed,’ he said hastily. ‘Many’s the thing you know, miss, many’s the thing. Goodbye, now.’

He put his foot down, shot off in a cloud of smoke and reappeared only moments later on the distant hillside. I was amazed the taxi could actually move that fast. Before the fumes had stopped swirling round me, Feely had roared across the boundary of my map and was well on his way back to Lisdoonvarna.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_ccfb6aa9-6177-5866-beeb-33329c14bfe9)

While I’d been talking to Mary Kane, streamers of cloud had blown in from the sea. Now, as I crossed the deserted road to the door of the cottage where Paddy stood waiting for me, a gusty breeze caught the heavy heads of the hydrangea and brought a sudden chill to the warmth of the afternoon.

‘Ah come in, miss, do. Shure you’re welcome indeed. ’Tis not offen Mary an’ I has a stranger in the place.’

Mary waved me to one of the two armchairs parked on either side of the stove and handed me a cup of tea.

‘Sit down, miss. Ye must be tired out after yer journey. Shure it’s an awful long step from Belfast.’

She glanced up at the clock, moved her lips in some silent calculation and crossed herself.

‘Ah, shure they’ll be landed by now with the help o’ God,’ she declared, as she settled herself on a high-backed chair she’d pulled over to the fire. ‘It’s just the four hours to Boston and the whole family ‘ill be there to meet them. Boys, there’ll be some party tonight. But poor Bridget’ll be tired, all that liftin’ and carryin’ the wee’ ans back and forth to the plane.’

She fell silent and gazed around the large, high-ceilinged room with its well-worn, flagged floor as if her thoughts were very far away. The sky had clouded completely, extinguishing the last glimmers of sunshine. Even with the door open little light seemed to penetrate to the dark corners of the room. What there was sank into the dark stone of the floor or was absorbed by the heavy furniture and the soot-blackened underside of the thatch high above our heads.

I stared at the comforting orange glow beyond the open door of the iron range. One of the rings on top was chipped and a curling wisp of smoke escaped. As I breathed in the long-familiar smell of turf I felt suddenly like a real traveller, one who has crossed wild and inhospitable territory and now, after endless difficulties and feats of courage, sits by the campfire of welcoming people. The sense of well-being that flowed over me was something I hadn’t known for many years.

‘Is it anyways?’

The note of anxiety in Mary O’Dara’s voice cut across my thoughts. For a moment, I hadn’t the remotest idea what she was talking about. Then I discovered you had only to look at Mary O’Dara’s face to know what she was thinking. All her feelings were reflected in her eyes, or the set of her mouth, or the tensions of her soft, wind-weathered skin.

‘It’s a lovely cup of tea,’ I said quickly. ‘But you caught me dreaming. It’s the stove’s fault,’ I explained, as I saw her face relax into a smile. ‘Your Modern Mistress is the same as one I used to know. It’s ages since I’ve seen an open fire. And a turf fire is my absolute favourite.’

‘Shure it’s not what you’d be used to atall, miss.’

‘Don’t be too sure of that,’ I replied, shaking my head. ‘I used to be able to bake soda farls and sweep the hearth with a goose’s wing. I’m out of practice, but I’d give it a try.’

‘Ah shure good for you,’ said Paddy warmly.

He put down his china teacup with elaborate care and turned towards me a mischievous twinkle in his eyes.

‘Now coulden’ I make a great match for a girl like you?’ he began. ‘There’s very few these days can bake bread. It’s all from the baker’s cart or the supermarket.’

I thought of the rack of sliced loaves by the door of my parents’ shop. Mother’s Pride, in shiny, waxed paper. They opened at eight every morning to catch the night workers coming home and the bread was always sold out by nine. ‘A pity we haven’t the room to stock more,’ said my father. ‘Or that the bakery won’t deliver two or three times a day.’

Bread was a good line. People came for a loaf and ended up with a whole bag of stuff. Very good for trade. And, of course, as my mother always added, the big families of the Other Side ate an awful lot of bread.

‘It was my Uncle Albert down in County Armagh taught me to make bread,’ I went on, reluctant to let thoughts of the shop creep into my mind. ‘He wouldn’t eat town bread, as he called it In fact, he didn’t think much of anything that came from the town. Except his pint of Guinness. His “medicine”, he used to call that.’

Paddy O’Dara’s face lit up. He looked straight at me, his eyes intensely blue.

‘Ah, indeed, miss, every man needs a drap of medicine now and again.’

‘Divil the drap,’ retorted Mary O’Dara. ‘I think, miss, it might be two draps or three. Or even more.’

It was true the arithmetic wasn’t always that accurate. I could never remember Uncle Albert being drunk, but he certainly livened up after he’d had a few. That was the best time to get him to tell his stories.

‘They’re all great men when they’ve had a few,’ she said wryly, as she offered us more tea.

‘Ah, no, Mary, thank you. Wan cup’s enough.’ Paddy got hurriedly to his feet. ‘I’ll just away an’ see to the goose.’

I smiled to myself, as she refilled my cup. Uncle Albert always went to ‘see to the hens’ when he’d been drinking.

‘I’ll have to go and see to the goose myself when I finish this,’ I said easily.

‘Ah, sure you knew we had no bathroom and I was wonderin’ how I would put it to ye.’

Her relief was written so plainly across her face that I wondered if she could ever conceal her feelings. I knew what my mother would say about someone like Mary. Only people with no education showed their feelings. Anyone with a bit of wit knew better. You couldn’t go round letting everyone see what you felt even if it meant ‘passing yourself’ or just ‘telling a white lie’.

My mother sets great store by saying the right thing. Most of her stories are about how she put so and so in their place, or gave them as good as she got, or just showed them they weren’t going to get the better of her.

Whatever my mother might think I knew Mary was no simple soul. She had a wisdom that I recognised. It was wisdom based on awareness of the world, of its joys and sorrows, of how people managed to live with them. I had known the same kindly, clear-eyed perspective on life for eighteen of my twenty-one years. I had lost it when Uncle Albert died and had not found it again. Until this moment.

‘Mrs O’Dara,’ I said quickly, ‘before Mr O’Dara comes back, you must tell me how much I’m to give you for my keep. Would four pounds a week be enough?’

‘Four pounds, miss . . . an’ the dear save us . . . I couldn’t take your money, shure you’re welcome to what we have, if it’s good enough for you.’

‘It’s more than good enough. But I must pay my way,’ I insisted quietly.

She had taken a basin from under the table that stood against the outside wall of the cottage and was putting the teacups to drip on the well-wiped oilcloth that covered its surface. She looked perplexed.

‘Have you a tea-towel, so I can dry up for you?’

‘Shure, two pounds would be more than enough, miss. I don’t know your right name.’

‘Elizabeth, Elizabeth Stewart.’

‘Well, two pounds, Miss Stewart, then, if you want to pay me.’

‘Oh you mustn’t call me that, Mrs O’Dara. I’m only called Miss Stewart when I’m in trouble with my tutor.’

She laughed gently and pushed a wisp of grey hair back from her face. ‘Well, indeed, no one calls me Mrs O’Dara either, savin’ the doctor and the priest. Nor Paddy either. Paddy woulden’ like me takin’ your money, miss . . . I mean Elizabeth.’

‘But you’re not taking my money. It’s just grocery money,’ I reassured her. ‘I’ll tell you what. I’ll put it in that teapot on the dresser every week, that wee one with the shamrock on it. You can tell him it was the little people. Say three pounds and we’ll split the difference.’

I went and took a striped tea-towel from the metal rack over the stove. Long ago, I had learnt to bargain for goods when I knew they were overpriced. I was good at it. This was the first time I had ever had to bargain upwards. I knew that Mary O’Dara would rather go short herself than exploit someone else. What a fool my mother would think she was not to take all she could get and close her hand on it.

I dried the cups and watched her put them away in the cupboard under the open shelves of the dresser. When she came back to the table, she ran the dish-cloth round the basin inside and out, slid it onto the shelf below, wiped the oilcloth and spread both the dish-cloth and the tea-towel to dry above the stove. She moved slowly, with a slight limp and a hunch in her shoulders that spoke of years of heavy work. But there was no resentment in her movements, neither haste, nor hurry, nor twitch of irritation.

I found myself thinking of a novel I’d read at school. The hero believed that all work properly done was an offering to God. His superiors thought he was mad, but his workmates didn’t. They were mechanics and the aircraft they serviced flew better than any others and seldom had accidents. The idea of a practical religion that worked on the principle of love really appealed to me, especially since the only one I was familiar with seemed to work entirely on the principle of retribution.

I smiled to myself. After Round the Bend I’d read everything Nevil Shute had written and enjoyed it enormously. Then, when my mother finally realised that he wasn’t on the A-level syllabus, there was a furious row. ‘Filling my head with a lot of old nonsense,’ was what she’d said.

Mary straightened up from the potato sack and came towards me. ‘Ah, ’twas my good angel that sent ye to my door today, Elizabeth, for I was heartsore. Sometimes our prayers be answered in ways we never thought of. Draw over to the table an’ talk to me, while I peel the spuds for the supper?’

‘I will indeed, Mary. But first, I really must go and look at the Aran islands.’

She laughed quietly as Paddy came back into the cottage and I went out, crossing the front of the house in the direction from which he had appeared. Somewhere round that side I’d find a well-trodden path to a privy in an outhouse, or the sheltered corner of a field.

The path led up behind the house, so steeply at first that there were stone steps cut into the bank. I stopped on the topmost one and found myself looking down on the roof. The cottage was set so close to the hillside, I could almost touch it from my vantage point. The thatch was a work of art. Combed so neatly there was not a straw out of place, it had an elaborate pattern of scalloping like the embroidery on a smock, all the way along the roof ridge, a dense weave to hold it firm against winter storms. Beyond the cottage, fields stretched down to the sea. Under the overcast mass of sky it lay calm and grey, but I could hear the crash of breakers where the long swells born in mid-Atlantic pounded the cliffs, a mere two fields away.

I counted the houses. Seven cottages facing west to the sea, each with turf stacks and smoke spiralling from their chimneys. Four more in various stages of dereliction, their roof timbers fallen, the walls tumbled, grass sprouting from the remains of the thatch. There should be another group of cottages facing south to Liscannor Bay, but from this angle they were hidden by high ground. I breathed a sigh of relief; here below me at least was a remnant of the community I had come in search of, a community once more than a hundred strong.

I stood for some time taking in every detail of the quiet, green countryside, the wide, grey sweep of the sea and the now-dark outlines of the islands. I thought of those who had once lived in the tumbled ruins, those who had been forced to go, those who had endured poverty and toil by remaining. Sadness swirled around me with the wind from across the sea. I knew nothing of these people, of their lives here in Lisara, or beyond in America, and yet some part of me felt as if I had known them, and this place, all my life. As I walked up the hillside, the sadness deepened. It was all the harder to bear because try as I might I could find no reason to explain my feelings.

By the time we cleared away the supper things the wind had strengthened and the dark clouds hurled flurries of raindrops onto the flags by the open door. Reluctantly, Paddy put down his pipe and went and closed it.

‘I may light the lamp, Mary, for it’s gone terrible dark. I think we’ll have a wet night.’

‘Indeed it looks like it, but shure aren’t the nights droppin’ down again forby.’

Paddy waited for the low flame to heat the wick and mantle, his face illuminated by the soft glow.

‘D’ye like coffee, Elizabeth?’

‘I do indeed, Mary, but are you making coffee? Don’t make it just for me.’

‘Oh no, no. Boys, I love the coffee meself, and Paddy too. Bridget always brings a couple of packets whinever she comes.’

Paddy put the globe back on the lamp and turned it up gently. The soft, yellowy light flowed outwards and the dark shadows retreated. I gazed across towards the corner of the kitchen where heavy coats hung on pegs. There the shadows were crouched against the wall. They huddled too beyond the dresser so that in the darkness I could barely distinguish the sack of flour leaning against the settle bed. But here I sat beyond the reach of the shadows in a warm, well-lit space. I leaned back in my chair and let my weariness flow over me, grateful for the moment that nothing was required of me.

Above my head, the lamplight caught the pale dust on the blackened underside of the thatch. The rafters were dark with age and smoke from the fire. A row of crosses pinned to the lowest rough-hewn beam ran the whole length of the seaward wall. Some were carved from bits of wood, others were woven from rushes now faded to a pale straw colour or smoked to a honey gold. A cross for every year? There were a hundred or more of them.

‘I’ll just get a wee sup of cream from the dairy.’

The lamp flickered and the fire roared as Mary opened the door and the wild wind poured in around us. As she pulled it shut behind her, I found myself gazing up at a tiny red flame that danced in the sudden draught. Beside it, on a metal shelf a china Virgin smiled benignly down upon the freshly wiped table, her hands raised in blessing over three blue and white striped cups and a vacuum pack of Maxwell House.

‘Boys, it would blow the hair off a bald man’s head out there,’ Mary gasped, as she leaned her weight against the door to close it, a small glass jug clutched between her hands.

‘That’s a lovely expression, Mary. I don’t know that one,’ I said, laughing. ‘I think Uncle Albert would’ve said, “It would blow the horns off a moily cow.”’

She repeated the phrase doubtfully, while Paddy chuckled to himself. ‘Ah Mary, shure you know a moily cow.’ He prompted her with a phrase in Irish I couldn’t catch. ‘Shure it’s one with no horns atall.’

She laughed and drew the high-backed chair over to the fire. I jumped to my feet.

‘Mary, you sit here and let me have that chair.’

‘Ah, no, Elizabeth, sit your groun’. I’m all right here.’

I sat my ground as I was bidden. I was sure I could persuade her to sit in her own place eventually, but it wouldn’t be tonight. When Mary did come back and sit in her own place, it would say something about change in our relationship. But that moment was for Mary to choose.

I watched Paddy fill his pipe, drawing hard, tapping the bowl and then, satisfied it was properly alight, lean back. The blue smoke curled towards the rafters and we sat silently, all three of us looking into the fire.

It was not the silence of unease that comes upon those who have nothing to say to each other, rather, it was the silence of those who have a great deal to say, but who give thanks for the time and the opportunity to say it.

We must have talked for two or three hours before Mary drew the kettle forward to make the last tea of the day. Paddy had told me about Lisara and the people who lived there, Mary spoke about their family, the nine sons and daughters scattered across Ireland, England, Scotland and the United States. In turn, I had said a little about the work for my degree, mentioned my boyfriend, George, a fellow student away working in England for the summer, and ended up telling them a great deal about my long summers in County Armagh when I went to stay with Uncle Albert.

It was only when Mary rose to make the tea, I realised I’d said almost nothing about Belfast, or my parents, or the flat over the shop on the Ormeau Road that had been my home since I was five years old.

‘Boys but it’s great to have a bit of company . . . shure it does get lonesome, Elizabeth, in the bad weather. You’d hardly see a neighbour here of an evening.’

I listened to the wind roaring round the house and reminded myself that this was only the beginning of September.

‘It must be bad in the January storms,’ I said, looking across at Paddy.

‘Oh, it is. It is that. You’d need to be watchin’ the t’atch or it would be flyin’ off to Dublin. Shure now, is it maybe two years ago, the roof of the chapel in Ballyronan lifted clean off one Sunday morning, in the middle of the Mass.’

He looked straight at me, his eyes shining, his hands moving upwards in one expressive gesture.

‘And the priest nearly blowed away with it,’ he added, as he tapped out his pipe.

‘Oh, the Lord save us,’ Mary laughed, hastily crossing herself, ‘but the poor man had an awful fright and him with his eyes closed, for he was sayin’ the prayer for the Elevation of the Host’.

As she looked across at me, I had an absolutely awful moment. Suddenly and quite accidentally, we had touched the one topic that could scatter all our ease and pleasure to the four winds. I could see the question that was shaping in her mind. It was a fair question and one she had every right to ask, but I hadn’t the remotest idea how I was going to reply.

‘Would ye be a Catholic now yerself, Elizabeth?’

‘No, Mary, I’m not. All my family are Presbyterians.’

‘Indeed, that’s very nice too. They do say that the Presbyterians is the next thing to the Catholics,’ she added, as she passed me a cup of tea.

If she had said that the world was flat or that the Pope was now in favour of birth control, I could not have been more amazed. I had a vision of thousands of bowler-hatted Orangemen beating their drums and waving their banners in a frenzy of protest at her words. I could imagine my mother, face red with fury, hands on hips, vehemently recounting her latest story about the shortcomings of the Catholics who made up the best part of the shop’s custom. Try telling her that a Presbyterian was the next thing to a Catholic. I looked across at Mary, sitting awkwardly on the high-backed chair, and found myself completely at a loss for words.

‘’Tis true,’ said Paddy, strongly. ‘Wasn’t Wolfe Tone and Charles Stuart Parnell both Presbyterians, and great men for Ireland they were, God bless them.’

I breathed a sigh of relief and felt an overwhelming gratitude to these two unknown men. The names I had heard, but I certainly couldn’t have managed the short-answer question’s prescribed five lines on either of them. The history mistress at my Belfast grammar school was a Scotswoman, a follower of Knox and Calvin. She had no time at all for the struggles of the Irish, their disorderly behaviour, their revolts, their failure to recognise the superior values of the British Government.

When she had made her choice from the history syllabus, she chose British history, American history and Commonwealth history. I could probably still describe the make-up of the legislatures of Canada, India or South Africa, and bring to mind the significant figures in the history of each, but I knew almost nothing about a couple of men who were merely ‘great men for Ireland’.

Yesterday, when the Hendersons had given me a lift to Dublin they had dropped me by the river within walking distance of the station. Under the trees, I gazed across the brown waters of the Liffey at a city I knew not at all. I had been to Paris and to London with my school, travelled in Europe on a student scholarship, visited Madrid, and Rome, and Vienna, but I had never been to Dublin. My parents had raised more objections to my coming to Clare than to my spending two months travelling in Europe.

It was pleasant under the trees, the hazy sunlight making dappled patterns on the stonework, a tiny drift of shrivelled leaves the first sign of the approaching autumn. I liked what I saw, the tall, old buildings with a mellow, well-used look about them, the dome of some civic building outlined against the sky, the low arches of the bridge I would cross on my way to the station.

‘A dirty hole,’ I heard my father say. ‘Desperate poverty,’ added my mother. Neither of them had ever been there.

I sat on my bench for as long as I dared before I set off to catch the last through-train to Limerick. Just as I reached the bridge, I saw the name of the quay where I had been sitting. ‘Wolfe Tone Quay,’ it said in large letters.

Mary took two candlesticks from the mantelshelf above the stove and I stirred myself. Paddy turned the lamp down and the waiting shadows leapt into the kitchen, swallowing it up, except for the tiny space where the three of us stood beside the newly lighted candles. Paddy blew down the mantle of the lamp to make sure it was properly out.

‘Goodnight Elizabeth, astore. Sleep well. I hope you’ll be comfortable,’ said Mary, handing me my candle.

‘Goodnight, Elizabeth. Mind now the pisherogues don’t get you and you sleeping in the west room,’ said Paddy. ‘And you might hear the mice playing baseball in the roof. Pay no attention, you’ll not disturb them atall,’ he added with a grin.

‘Come on, old man, it’s time we were all in bed.’

He laughed and followed her towards the brown door to the left of the fireplace.

‘Goodnight, and thank you both. It was a great evening,’ I said, as I pointed my candle into the darkness at the other end of the kitchen.

I pressed the latch of the bedroom door, pushed it open, and reached automatically for the light switch. Of course, there wasn’t one. My fingers met a small, cold object which fell off the wall with a scraping noise. As I brought my candle round the door, I saw another china Virgin. This one was smaller than the one in the kitchen and from her gathered skirts she was spilling Holy Water on my bed.

Thank goodness, no harm done. I put her back on the nail and swished the large drops of water away from the fat, pink eiderdown before they had time to sink in. The room was cold and the wind howling round the gable made it seem colder still. I undressed quickly, the linoleum icy beneath my feet when I stepped off the rag rug to blow out the candle on the washstand. The pillowcase smelt of mothballs and crackled with starch under my cheek as I curled up, arms across my chest, hugging my warmth to me.

‘And don’t say the bit about getting my death of cold sleeping in a damp bed. It isn’t damp. Just cold. And it will soon warm up.’

I laughed at myself for addressing my mother before she could get in first. She had beaten me to it last night in Limerick. Oh, the predictability of it. Like those association tests my friend Adrienne Henderson did in psychology. She said a word and you had to respond without thinking. My parents were good at that. I knew the key words. Or more accurately, I spent my life avoiding them. If I accidentally tripped over one, I could be sure I would get a response as predictable and consistent as a tape-recording.

The smell of the snuffed candle floated across to me. I was back in the small upstairs room of Uncle Albert’s cottage. The candle wax made splashes on the mahogany furniture and I picked them off with my fingernails, moulded them and made water-lilies to float on the rainwater barrel at the corner of the house. Suddenly, I was there again, a ten-year-old, sent to ‘the country’ for the holidays.

Being ten years old didn’t seem at all strange. I lay in the darkness, wondering if I would always be able to remember what it was like to be ten. Would I be able to do it when I was thirty, or forty, or fifty? Or would some point come in my life where I would begin to see things differently? For as long as I could remember, my parents, my relatives and those neighbours who were ‘our side’ had all assured me that when I was ‘grown up’, or ‘a little older’, or ‘had a family of my own’, I would come to see the world as they did. The thought appalled me.

Was it really possible that I could end up locked into the kind of certainty that permeated all their thinking? They always knew. They were sure. Indeed they were so sure, I regularly panicked that I would come to think as they did. What if there was nothing to be done to stop the process? What would I do if I found that thinking as they did was like going grey, or needing spectacles, or qualifying for a pension, one of those things that was as inevitable as the sun rising tomorrow.

As I began to feel warm I uncurled and lay on my back. Moonlight was flickering from behind dark massed clouds and gradually my eyes got used to the luminous glow reflected from the pink-washed walls. I distinguished the solid shape of the wardrobe at the foot of my bed and the glint of the china jug on the washstand. Then, quite suddenly, for a few moments only, the room was full of light. In the brightness, I saw a large, grey crucifix on the distempered wall above me. Crucifixes and Holy Water. Even more to be feared than a damp bed.

The room settled back to darkness once more and I closed my eyes. The door latch rattled and stopped. Then rattled again. Perhaps I wouldn’t have to change after all. Perhaps I could just go on being me at twenty-one, or thirty-one, or any age, till I was so old there would be no one left older than me, to tell me what I ought to think. There was a scurry of feet in the roof. The wind whined round the gable and the door latch rattled again. The scurrying increased. Mice, of course.

And pisherogues. I had not the slightest idea what a pisherogue was. But whatever it turned out to be, it would not harm me. Indeed, in this unknown place at the edge of the world, I felt as if nothing could harm me. Tomorrow, I would ask Paddy what a pisherogue was and make a note about it. I was going to make lots and lots of notes. In the blue exercise books I had brought with me. Tomorrow.

Chapter 3 (#ulink_d8c2f7f7-708e-5ea6-838a-3942029f2600)

After three days tramping the lanes and fields of Lisara I was looking forward to my walk into Lisdoonvarna on Thursday afternoon. Paddy was sure I’d get a lift, but as I strode along, turning over in my mind all I’d learnt since my arrival, the only vehicles that overtook me were full of children and luggage. I was very glad when they waved and left me to the quiet of the sultry afternoon.

As I reached the outskirts of the town and turned up the hill by the spa wells, I was surprised to find there were people everywhere. Preoccupied and distracted, they wandered over the road, walked up and down to the well buildings and streamed back and forth to the Square. After the emptiness of the countryside and the company of my own thoughts, the sudden noise and bustle hit me like a blow. I wove my way awkwardly between family parties, strolling priests, and bronzed visitors, only to find that the Square too was completely transformed.

The empty summer seats were now packed with brightly coloured figures. Close by, a luxury coach unloaded a further consignment. Clutching handbags and carrier bags, beach bags and overnight bags, they queued erratically beside a small mountain of luggage and reclaimed matching suitcases from a uniformed courier.

I’d been planning to sit down for a bit but now even the stone wall of the war memorial was fringed by families eating ice-creams. Nothing for it but the first grassy bank on the way home.

The queue for the post office greeted me on the broken pavement outside. It moved slowly forward. When I finally got inside the door the smell of damp and dry rot caught at my nostrils. The place hadn’t seen a paintbrush for years, the walls were yellowed with age and seamed with cracks. Behind a formidable metal grille, an elderly lady with iron-grey hair and spectacles despatched stamps and thumped pension books with dogged determination, apparently unconcerned by the queue of restless women with coppery tans, white trousers and suntops in violent shades of lime-green and pink.

I shuffled forward on the bare wooden floor. In front of me, an old lady cast disapproving glances at two women writing postcards on the tiny ledge provided. She glared at their bare shoulders and arms and the skimpy tops that revealed their small, flat breasts. Despite the heavy warmth of the afternoon, she was wearing a black wool coat and a felt hat firmly skewered to her head with large, amber hatpins.

The woman behind me fidgeted impatiently and shuffled her postcards as if she were about to deal a hand of whist.

‘Gee, you Irish girls sure do have lovely complexions. How come you manage it?’

Her voice so startled me, I must have jumped a couple of inches but I went on watching the postmistress counting out money for the old lady, a pound note and some silver coins. Could her pension possibly be so small?

I felt a tap on my shoulder. When I turned round she was looking down at me. Waiting. Pinned to her suntop was a button which said: ‘I’m Adele from New York City . . . Hi.’

‘I think it’s probably the climate,’ I said, awkwardly.

The moment I spoke I knew it was ‘my school teacher voice’. George often says I must never become a teacher. Women who do always lose their femininity and he couldn’t bear that. He loves me just as I am so I mustn’t ever change.

‘D’you mean all that there rain we had in Killarney lass’ week?’

She looked baffled, but something in her manner suggested she would not give up easily. People were turning to look at us and I felt my ‘Irish’ complexion grow a few shades more rosy.

‘I think it’s the dampness of the air here.’

I tried to sound suitably casual, but I just sounded lame. What else could I say? I could hardly explain the adaption of skin colour and texture to environmental features, could I? What on earth would George say if I did that?

‘Gee, you Irish girls do talk cute.’

She beamed indulgently and gazed around at the women writing postcards, delighted to have got one of the natives to perform.

I was saved from further questions by the little lady in black who pushed past me, handbag firmly clutched in both hands, leaving me to face the postmistress who stared at me fiercely as I handed over my letters.

‘You’d be a friend of Mrs O’Dara, then?’

I nodded awkwardly. Of course Mary and I were friends, but I knew that wasn’t what she meant.

‘I’m staying with Mr and Mrs O’Dara for a few weeks,’ I said quickly. ‘I’m a student.’

‘We don’t get many students here,’ she said suspiciously. ‘Is it the Irish yer leamin’?’

‘Only the odd wee bit from Mr O’Dara. I’m really studying farming.’

That sounded a bit schoolmistressy too. Behind me, the queue was building up again and Adele from New York City was breathing down my neck.

‘And that’s nice fer ye too,’ she said decisively, as she studied the envelope addressed to Mr and Mrs William Stewart.

‘You’d be wanting to let yer paren’s know ye was safely landed, indeed,’ she said severely, as she turned her attention to my letters to George and Ben, and my thank you to the Hendersons.

‘Oh, I did write letters on Monday, but Paddy the Postman took them for me.’

‘Indeed, shure he wou’d take them for you, and why wou’dn’t he?’

Her face crinkled into a grimace that looked like a friendly gesture, though I could hardly call it a smile.

‘I’ll be seein’ ye again, Miss Stewart, won’t I?’

‘Oh yes, you will indeed. I’ll be doing the shopping while I’m here.’

I was so glad to escape the smell of Adele’s Ambre Solaire that I set off back to the Square at a brisk trot. But I had to slow down. Apart from the ache in my legs, the afternoon was getting hotter by the minute. Huge clouds were building up in threatening grey masses and it felt warm, sticky and airless.

The windows of the hotel with the summer seats had been thrown wide but there wasn’t the slightest trace of a breeze. The net curtains hung motionless and I could see into the dining room where small black figures moved to and fro. Like the pale, dark-eyed girls I’d seen at the Mount, these girls were equally young, straight from school at fourteen.

I thought about them as I waited in the queue at the butcher’s, drawing circles in the sawdust with my toe. I too might have left school at fourteen if I hadn’t passed the Eleven Plus. Even then, I still might have had to leave if it hadn’t been for the Gardiners.

‘Did ye hear that Mrs Gardiner today, bumming again?’

I was back in my bedroom in Belfast on a summer evening towards dusk, reading in the last of the light. My parents had come out into the yard behind the shop. There was a rattle as my father filled his old metal can so he could water the geraniums and the orange lilies which he grew in empty fuel oil cans he’d brought home from Uncle Joe’s farm. It was the beginning of July, for the lilies were in flower but hadn’t yet been taken to the Lodge to decorate the big drums for the Twelfth.

‘Oh yes, she was in great form, and the whole shop full. Did ye not hear? Ah don’t know how ye cou’da missed her.’

The reply was indistinct. My father always speaks quietly. Often, he just nods or grunts.

‘There’ll be no standin’ that wuman, if that wee girl of hers goes to Victoria an’ our Elizibith doesn’t.’

Eavesdroppers hear no good of themselves, I thought to myself. But there wasn’t much I could do about it. The window was wide open and they were right underneath.

‘Well, if Bill Gardiner is going to send that wee scrap of a girl, why shouldn’t we send our Elizibith,’ my mother went on. ‘None of the Gardiners have any brains worth talkin’ about an’ that shop of theirs is only a huckster of a place, not even on the main road. It won’t look well at all, Willy, if we don’t send her. People’ll think our shop’s not doin’ well. I think we should just send her. We’re every bit as good as the Gardiners. We’d have done it for wee Billy for sure.’

I stuck my fingers in my ears, for I hated them talking about wee Billy and I knew that was wicked. You shouldn’t hate your brother, especially if he was dead. The trouble was it didn’t feel as if he was dead. They were always talking about him, what he liked and disliked, what he used to say, what age he would be his next birthday if he’d lived, where he would be going to school, or even what flowers they would take when they next visited the cemetery where he was buried. My Aunt Maisie once said to me that it was a pity I hadn’t been a boy, for Florrie would never get over wee Billy now and her too old to have another.

I lifted Mary’s shopping bag onto the counter and let the red-faced man put the brown-paper parcel inside. The butcher’s counter was marble and the one in the shop was wood. I imagined myself standing behind it in a pink, drip-dry, nylon shop coat like my mother’s, handing out papers and cigarettes and penny lollipops, ringing up items on the till, running up the rickety stairs to the stockroom for a new box of Polo mints, or a fresh carton of Players.

He counted out my change slowly, made a mistake and corrected himself. His fingers were smeared with blood. My father’s fingers were yellowed with nicotine, the nails cut short to keep them clean. I could see him as he spread the day’s takings on the table each evening. Piles of silver, mounds of copper, creased pound notes, and the occasional papery fiver which he held up to the light to make sure it was all right. Business was good, he would admit as he counted. Never better, my mother would agree. Everyone has money these days, she would continue, especially the Other Side.

It was the Other Side’s money that let me stay at school to take A-levels. Then my scholarship had taken me to Queen’s. After seven years passing the back of the students’ union every day on my way to school, I got off the bus one stop earlier and stepped into a different world. It was luck. Pure luck. I had my books and my hopes for the future, these girls had their skimpy black skirts and their long hours of hard, poorly paid work.

‘Well then, how do you fancy a career in catering?’ Ben and I were sitting in our usual seats at the top of the double decker, our first week’s pay envelopes torn open on our knees.

‘Not a lot,’ I replied. ‘If this was all you had to live on you wouldn’t have much of a life, would you?’

‘No, not even if there were two of you and there was equal pay.’

I laughed wryly and counted the crumpled notes in my hand. We had worked so hard, sharing the same dreary jobs, working the same long hours. Ben had ten pounds, I had only seven.

‘It’s one thing if you’re earning book money,’ he went on, stuffing the notes into his pocket, ‘it’s another if it’s all you’ve got. Are you going to have enough for going to Clare, Lizzie?’

I’d reassured him that I’d be fine for I knew he’d offer to help me. I couldn’t let him do that for I knew what he was planning to buy. The newly published book he hoped might help him to make sense of his mother’s condition would cost several weeks’ work.

‘It’s exploitation, Ben, isn’t it? But what can one do? What can anyone do?’

‘Political action, Lizzie. Probably the only way. But that’s not my way. It needs a particular sort of mind and I know I haven’t got it. I’ll have my work cut out to make a decent doctor. What about you?’

I told him I didn’t really know about me.

The first thing I noticed as I opened the door of Delargy’s shop was the smell. This time, unlike the post office, it brought the happiest of memories: small shops in Ulster, in villages where I had done messages for various aunts, places where you could buy everything from brandy balls and humbugs to groceries and grass seed, packets of Aspros and pints of Guinness. There had been many such places in my childhood and I had loved them all.

Surprisingly, the shop was empty but for a single customer, the little lady in the black coat whose hatpins I’d studied closely in the post office queue. A pleasant-faced girl in a blue overall had come from behind the counter to pack her shopping bag. As she fitted in the packets of tea and sugar, she listened sympathetically to what the old lady was saying.

‘And they want to put me out and knock the whole row down.’

‘But Mrs McGuire dear, they’ll have to give you a new house, or one of the bungalows. Wouldn’t that be nice for you now, and no stairs to climb?’

The girl glanced at me and made a slight move as if to come and serve me but I shook my head. ‘I’m not in a hurry. Do you mind if I have a look round?’

‘Do, miss, do. I’ll be with you shortly.’

We exchanged glances over the head of Mrs McGuire, who was completely absorbed in her problem. Indeed, they were very nice, she agreed. And a nice price too. Where would she get seventeen shillings rent out of her pension?

I moved away in case my presence would disturb them and began to examine the contents of the long, low-ceilinged room. A solid wooden counter ran the whole length of one side. Behind it, shelves filled with packets and boxes rose to the ceiling, except at a central point where a large clock with dangling weights ticked out the separate minutes of the day. Against the counter leaned bags of dried goods, barley and rice, lentils and oatmeal, each with its polished metal scoop thrust into the mouth of the sack ready to measure into the pan of the shiny brass scales on the counter. Beyond the end of the counter, a low-arched doorway led into a passage which gave access to the stable yard outside.

On the opposite wall was the bar. Empty now. But the fluorescent light was on. It reflected in the rows of bottles and glinted off the well-polished seats of the high stools. At the furthest end of the bar, a new Italian coffee machine had just been installed. It sat, still partly draped in its polythene wraps, looking across the worn floorboards to a stand of Wellington boots and a rack of Pyrex ware.

I wandered around slowly. Who would buy the bottles of DeWitts Liver Pills, the mousetraps with the long-life guarantee, the shamrock-covered egg-timers, the hard yellow bars of Sunlight soap? And what would the same people make of the contents of the freezer, tucked between a pile of yard-brushes and a display unit of the blue and white striped delft I’d met at the cottage. Prawn curry. Chicken dinner for two. French beans and frozen strawberries. Unlikely substitutes for the bacon and cabbage, the champ, or the stew Mary had cooked for our supper on these last evenings.

Below a small counter laid out with newspapers and magazines, I found some exercise books. The notebooks I’d brought with me were filling up rapidly and these had the wide-spaced lines I liked. As I turned one over to look for the price, I heard voices in the passage leading to the stable yard.

‘Now don’t worry, Moyra. You concentrate on Charles and I’ll see to the stock. Paddy knows what’s needed here and Mrs Grogan won’t let you down in the hotel.’

There was a woman’s voice too, light and pleasant but further away.

‘I’ll come in this evening to make sure all is well, but I won’t come up to you. You look tired yourself.’

The voice intrigued me. It had something of the intonation of the voices I’d been hearing all around me since I arrived, but it was more formal. With her sharp ear for social distinctions, my mother would pronounce the owner either ‘educated’ or ‘good class’, depending on the mood she was in.

‘Are you all alone, Kathleen?’

I glimpsed the figure who strode across the empty shop to where Kathleen had just closed the door behind Mrs McGuire. I busied myself with the stand of postcards as he followed her glance.

‘It went quiet a wee while ago, so I let May and Bridget go for their tea,’ she explained. ‘They hardly got their lunch atall we were so busy. It’s teatime in the hotels, that’s why it’s gone quiet.’

He nodded as he listened to her. I had the strange feeling he was watching me out of the corner of his eye. A rather striking man. What some people might call handsome. A strongly shaped face, rather tanned, dark, straightish hair. He seemed to tower over Kathleen who was about my own height.

‘I’ve been talking to Mrs Donnelly and I’ve told her I’ll take care of the stock till Mr Donnelly is better. Would you let me have a note of anything you can think of. It’s so long since I’ve done the ordering I shall probably be no good at all.’

Kathleen laughed easily at the idea and said she’d start a list right away. He moved towards the door leading out into the Square and then, as if he had forgotten something, he turned and walked back towards me.

‘I’m afraid the selection isn’t very good,’ he said, as I looked up from the postcards. ‘We’ve some new colour ones on order from John Hinde, but there seems to be some delay.’

His eyes were a very dark brown and he was looking at me carefully, as if he was possessed by the same curiosity I had come to expect, but was too well-mannered to let it show.

‘I don’t honestly think they do justice to the place,’ I replied, nodding at the inexpensive sepia cards on the stand. ‘I’m glad you’re getting the John Hinde, he’s done some very good ones of Donegal.’

‘But you don’t come from Donegal, do you?’ he replied promptly. ‘I’d have thought it was more likely to be Armagh or Down myself.’

I had to laugh. Partly because it’s a game I play myself, placing people by their accent, and partly because he was so accurate. Even after growing up in Belfast, my accent hadn’t lost the markings of my earliest years when we lived with my grandparents down near the Armagh-Monaghan border.

‘You’re not far wrong,’ I admitted, smiling at him. ‘Very near in fact, but I live in Belfast now.’

‘Yes,’ he agreed, ‘and you’re staying with Paddy and Mary O’Dara at Lisara.’ He held out his hand and made me a small bow. ‘Miss Elizabeth Stewart, I presume. Patrick Delargy at your mercy.’

‘How on earth did you know that?’

His hand was warm and firm and he was smiling broadly.

‘Kathleen, come over here a moment Come and meet the lady herself. Does she answer the description we had of her?’

Kathleen hurried over.

‘Oh, miss, you made us all laugh, you did indeed. Didn’t you put the fear of God into Michael Feely on Sunday. I hear he’s not the better of it yet.’

Patrick Delargy leaned himself comfortably against the side of the freezer. ‘I missed all the fun,’ he said sadly. ‘Kathleen had better tell you the whole story.’

‘Ah miss, poor Feely came in here on Sunday evening and we thought he had seen a ghost,’ she began, her face horror-stricken.

I was so worried by the look on her face and the thought that I’d upset Michael Feely that I turned to Patrick Delargy to see how he was reacting. He appeared to be enjoying himself thoroughly.