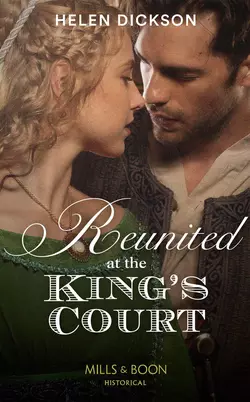

Reunited At The King′s Court

Хелен Диксон

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 640.49 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Kept apart by duty… Reunited by love? Arlette Dryden has never forgotten William Latham, the Royalist soldier who accompanied her to safety while the battle of Worcester raged. Or how her heart broke when he left. Now, it’s the exiled king’s return parade, and stunned Arlette locks eyes with her charismatic cavalier again. She’s still irresistibly drawn to him, but as both have convenient betrothals beckoning, can their long-held passion conquer all?