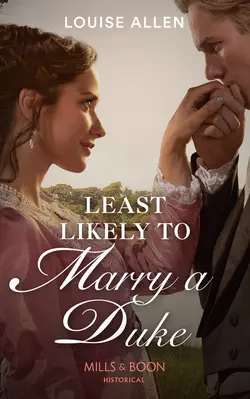

Least Likely To Marry A Duke

Louise Allen

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 677.35 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A marriage of inconvenience For the buttoned-up Duke! Bound by convention, William Calthorpe, Duke of Aylsham is in search of a suitable bride to help raise his half-siblings. Despite his methodical approach to finding such a lady, he stumbles – quite literally – into free-thinking and rebellious bishop’s daughter Verity Wingate. And when they find themselves stranded overnight on a tiny island, compromising them completely, he knows exactly what he must do…