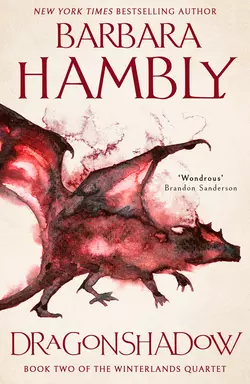

Dragonshadow

Barbara Hambly

Dragonshadow is book two in the breath-taking The Winterlands – an epic, classic fantasy quartet full of whirlwind adventure, magic and dragons. Lord John Aversin and the mageborn Jenny Waynest continue to battle and study dragons. Many years have passed since their battle at Bel and while they remain strong, their love for one another has begun to wane with the passing seasons. But time moves against them in more ways than one. For a danger unlike any they have ever known in their long years of violence begins to stir. Demonspawn from a dark dimension have learned to drink the magic and the souls of mages and dragons alike, turning their victims into empty vessels. The demons are rising and have stolen the couple’s young son. In desperation, John seeks the help of the eldest and strongest dragon: Morkeleb the Black. But it may not be enough. In the coming struggle, all will question what they believe in, and some may have to sacrifice what they value most in order to survive…Dragonshadow is book two in the breath-taking The Winterlands – an epic, classic fantasy quartet full of whirlwind adventure, magic and dragons.

DRAGONSHADOW

BOOK TWO OF THE WINTERLANDS QUARTET

Barbara Hambly

Copyright (#udc5117d0-78f7-5ce2-bf91-4d7fe969b1d4)

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1999

Copyright © Barbara Hambly 1999

Map © Shelly Shapiro

Cover illustration © Nakonechnyi Jaroslav

Cover design by Andrew Davis © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Barbara Hambly asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008374204

Ebook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780008374211

Version: 2019-10-14

Dedication (#udc5117d0-78f7-5ce2-bf91-4d7fe969b1d4)

For J.W.L.

Contents

Cover (#u02c98029-7aa9-5ca1-a470-2d4731e09fbf)

Title Page (#uce6ff666-c27e-5d40-ae07-047e2473f0a7)

Copyright

Dedication

Maps

Book One: The Skerries of Light

Chapter One (#u9175c0ce-6c52-5e38-ae34-33be53a2dbec)

Chapter Two (#uff2d153e-be96-54d4-9432-3c047a17f0c7)

Chapter Three (#u2b0400b7-53e8-5491-b03d-cb1aa448cb4a)

Chapter Four (#ua59103ff-d098-5512-af88-e0b950907aff)

Chapter Five (#uc29c6aa6-d26e-5c40-8716-9962cb1264ea)

Chapter Six (#u02aa51b8-9198-5477-a713-db7af81953db)

Chapter Seven (#u09bfffab-ace7-5e87-8129-5d0d78a5ee78)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Book Two: The Burning Mirror

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

Also by Barbara Hambly

About the Publisher

Maps (#udc5117d0-78f7-5ce2-bf91-4d7fe969b1d4)

Book One (#udc5117d0-78f7-5ce2-bf91-4d7fe969b1d4)

THE SKERRIES OF LIGHT (#udc5117d0-78f7-5ce2-bf91-4d7fe969b1d4)

ONE (#ulink_5ef4cb15-eec0-52ae-8618-71e4fd03777e)

DRAGONSBANE, THEY CALLED him.

Slayer of dragons.

Or a dragon, anyway. And, he’d later found out, not such a very big one at that.

Lord John Aversin, Thane of the Winterlands, leaned back in the mended oak chair in his library as the messenger’s footfalls retreated down the tower stairs, and looked across at Jenny Waynest, who was curled up on the windowsill with a cat dozing in her lap.

“Bugger,” he said.

The night’s first appreciable breeze—warm and sticky as such things were in the Winterlands in summer—brought the grit of woodsmoke through the open window and made the candle flames shudder among the heaped books.

“A hundred feet long,” Jenny murmured.

John shook his head. “Gaw, any dragon looks a hundred feet long if you’re under it.” He pushed his round-lensed spectacles more firmly onto the bridge of his long nose. “Or in a position where you have to think about bein’ under it in the near future. I doubt it’s over fifty. That one we slew over by Far West Riding wasn’t quite thirty …” He nodded to the cold fireplace, where the black spiked mace of the golden dragon’s tail-tip hung. “And Morkeleb the Black was forty-two, though I thought he’d whack me over the back of the head when I asked could I measure him.” He grinned at the memory, but behind the spectacles Jenny could see the fear in his eyes.

Almost as an afterthought he added, “We’ll have to go after it.”

Jenny stroked the cat’s head. “Yes.” Her voice was inaudible. The cat purred and made bread on her knee.

“Funny, that.” John got to his feet and stretched to get the crick out of his back. “I’ve put together every account I can find of past Dragonsbanes—all them old ballads and tales—and matched ’em up as well as I could with the King-lists.” He gestured to the vast rummage that covered desk and floor and every shelf of the low-vaulted study: bound bundles of notes, parchments half copied from waterstained books found in the ruins south of Wrynde. Curillius on The Deeds of the Ancient Heroes, Gorgonimir’s Creatures and Phenomena. A fair copy of a fragment of the old Liever Draiken sent by the Regent of Bel, a connoisseur of both ancient manuscripts and the tales of Dragonsbanes. Notes yet to be copied—he’d jotted them down two years ago—of a dragon-slaying song sung by one of the garrison at Cair Corflyn, all mixed up with wax note tablets, candles, inkwells, scrapers, prickers, pumice, candle scissors, and dismantled clocks. For the fourteen years they’d been together, Jenny had heard John swear every year or two he’d put the place in order, and she knew that the phrase “put together” must not be taken too literally.

Magpie gleanings of learning by a man whose curiosity was an unfilled well; accretions of useful, interesting, or merely frivolous lore spewed back at random by circumstance and the mad God of Time.

“Some Dragonsbanes slay one dragon and that’s that, they’re in the ballads for good,” mused John. “Others slay two or three, and two of those, as far as I can figure ’em, are within ten years of the singletons. Then you’ll get generations, fifty, sixty, seventy years, when the dragons mind their own business, whatever that is, and nobody slays anybody. This is three for me. How’d I get so lucky?”

“The North is being settled again.” Jenny set Skinny Kitty aside and went to stand behind John, her arms around his waist. Through his rough red wool doublet and patched linen shirt she felt the ribs under the hard sheath of muscle, the warmth of his flesh. “It was the cattle herd at Skep Dhû garrison that the dragon hit. There probably hasn’t been this much livestock in the North since the Kings left. It may have drawn this one.”

“Gaw,” he said again, and set his hand over the folded knot of hers. An oddly deft hand for a warrior’s, inkstained and blistered in two places from a chemical experiment that took an unexpected turn. But thick, like his forearm, with the muscle of a lifetime of wielding a sword. In profile his was the face of a scholar. In his reddish-brown hair, hanging loose to his shoulders, the candlelight gilded the first flecks of gray.

He’d been twenty-four when he’d gone against the gold Dragon of Wyr, and his side still hurt like a knife-thrust from the damaged ribs whenever the weather turned. Jenny’s fingers could detect the ridge of the biggest scar he’d taken when he fought Morkeleb the Black in the burned-out Deep beneath Nast Wall. Life is fragile, she thought. Life is precious, and life is short. “How many is the most any Dragonsbane has been able to slay?” she asked, and John half-turned his head to grin down over his shoulder at her.

“Three. That was Alkmar the Godborn. His third dragon killed him.”

In the hour or so that separated them from moonrise, John and Jenny mustered all they would need for the slaying of the Dragon of Skep Dhû, such of them as were stored at the Hold. John’s battle armor, almost as battered and sorry as the doublet of black leather and iron in which he was wont to patrol his lands. Two axes, one a short, single-grip weapon that could be wielded from the back of a horse, the other longer and heavier, a two-handed thing for finishing a creature dying on the ground. Eight harpoons, like boar spears but larger, barbed and massive and written over with spells of death and ruin.

John’s half-brother Muffle, sergeant of the local militia and smith of the village of Alyn, had forged the first two in a hurry, when the Dragon of Wyr had descended on the herds of Great Toby fourteen years ago, and the others had been made a few weeks after that. Jenny had put spells of death on them all. In those days her powers had been small, hedge-witch magics taught her by old Caerdinn, who had once been tutor at Alyn Hold, and she had known little of dragons, only scraps and snippets culled from John’s books. Killing the golden dragon had taught her something of a dragon’s nature, so when Prince Gareth of Magloshaldon, later Regent for the King of Belmarie, had come begging John’s help against the Dragon of Nast Wall, she had been able to weave more accurate spells. Her magic was still, at that time, small.

Now she sat on the wooden platform that John and Muffle had built at the top of the tower for John’s telescope. The eight harpoons lay before her on the planks. Far below she heard John’s voice, and Muffle’s, distant as birdsong but far more profane, as they dragged out cauldrons and wood. She heard Adric’s voice, too, a gay treble—her second son, at eight burly and red-haired and every inch the descendant of John’s formidable, bearlike father: He should be in bed! Beyond a doubt three-year-old Mag was trailing, silent as a marsh fey, at his heels.

For a moment she felt annoyed at John’s Cousin Dilly, who was supposed to be looking after the children, and then let all thought of them slip away with the releasing of her breath. You cannot be a mage, old Caerdinn had said to her, if your thoughts are ever straying: to your supper, to your child, to whether you will have the next breath of air after this one is gone from under your ribs. The key to magic is magic. Never forget that.

And though she had found that magic’s key was something else, in many ways the old man had been correct. Her thought circled, like the power circle she had drawn on the platform around herself and the harpoons, and like the power that came down to her in silver threads from the shape of the stars, her thought took shape.

Cruelty. Uncaring. The quenching of life. The weary welcoming of the final dark.

Death-spells. And behind the death-spells, the gold fierce fire of dragon-magic.

For four years, now, that dragon-blaze had burned in her blood.

Morkeleb, she thought, forgive me.

Or was it not a thing of dragons to forgive?

Morkeleb the Black. The Dragon of Nast Wall.

She summoned the magic down from the stars, out of the air, called it from the core of fire within her that had burned into life when, by Morkeleb’s power, she had been transformed to dragon-kind. Though she had returned to human form, abandoning the immortality of the star-drakes, part of her essence, her inner heart, had remained the essence of a dragon, and she understood power as dragons understood it. Since it was not a thing of dragons to think or care, she did not, as she wove her death-spells, think or care about Morkeleb, who had loved her.

Loved her enough to let her return to human form.

Loved her enough to return her to John.

But after the death-spells were wrought and bound into the harpoons, she sat on the rickety platform above the Hold, her arms clasped round her knees, listening to the far-off voices of her husband and her son and remembering the skeletal black shape in the darkness, the silver labyrinthine eyes.

Morkeleb.

“Mother?”

Starlight showed the trapdoor that opened among the slates of the turret roof, but it did not penetrate the shadow underneath. Mageborn, Jenny was able to see her elder son, Ian, a weedy twelve-year-old, her own night-black hair and blue eyes in John’s beaky face. He stepped onto the steeply slanting roof and made to come down the stairs, and she said, “No, wait there.” The weariness of working the death-songs dragged at her bones. “Let me gather these up and send them on their way.”

Ian, she knew, would understand what she said. Only this year his own powers had started to manifest: small, as any teenager’s were—the ability to call fire and find lost objects, to sometimes see in fire things far away. Ian sat on the trapdoor’s sill and watched in fascination as she drew the glimmer from out of the circles, collecting it like cold spider-silk in her hands. All magic, Caerdinn had taught her, depended on Limitations. Before even beginning to lay down the circles of power, let alone summon the death-spells, she had cleansed the platform with rainwater and hyssop and laid on each separate rough-hewn plank such Words as would keep the vile magics from attaching to the place itself. Spells, too, were required to hold the wicked ferocity of what she had done within a small space, so it would not disperse over the countryside and cause ruin and death to everyone in the Hold, in the village, in the farms that nestled close to the walls. Like a miser picking up pinhead-sized crumbs of gold dust with his fingernails, so Jenny gathered into her palms each whisper and shudder of the death-spells’ residue, named them and neutralized them and released them into the turning starlight.

“Can I help?”

“No, not this time. You see what I’m doing, though?” He nodded. As she worked, she felt, rising through her—as it always rose, it seemed to her, at the most inopportune of times—the miserable flush of heat, the reminder that the change of a woman’s life was coming upon her. Patiently, wearily, she called upon other spells, little silvery cantrips of blood and time, to put that heat aside. “With spells of cursing you must be absolutely thorough, absolutely clean, particularly with spells worked in a high place,” she said.

Ian’s eyes went to John’s telescope, mounted at the far side of the platform; she saw he read her thought. It would not take much, they both knew, for the rail to give way, or John to lose his balance. A fragment of curse, a stray shadow of ill will, would be enough to cause John or Ian or anyone else to forget to latch the trapdoor, or for the latch to stick, so that Adric or Mag, or one of Cousin Rowanberry’s ever-multiplying brood, could come up here …

And even so, the platform was the safest place in all the Hold to work such spells.

As she and Ian bore the harpoons down the twisting stair, Jenny remembered what it had been, to be a dragon. To be a creature of diamond heart and limitless power. A creature to whom magic was not something that one did—well or less well—but the thing that one was: will and magic, flesh and bone, all one.

And not caring if a child fell from the platform.

With the moon’s rising John and Jenny and Ian rode out from Alyn Hold to the stone house on Frost Fell, where Jenny had for so many years lived alone. It had been Caerdinn’s house, and Jenny had lived as the old wizard’s pupil from the time she was thirteen and the buds of power she’d had as a child began to blossom. A single big room and a loft, bookshelves, a table of pickled pine, a vast hearth, and a big bed. It was to this house that John had first come to her, twenty-two and needing help against one of the bandit hordes that had been the scourge of the Winterlands in the days before the King sent his protecting armies to them again. He’d been challenged, Jenny recalled, to single combat by some bandit chief—maybe the one who had slain his father—and had heard that no weapon could harm a man who’d lain with a witch.

But she’d remembered him from her own childhood and his. His mother had been Jenny’s first teacher in the arts of power, a captive woman, an Icerider witch: the scandal when Lord Aver married her had been a nine days’ wonder through the Winterlands. When her son was four and Jenny seven, Kahiera Nightraven had vanished, gone back to the Iceriders, leaving Jenny with no better instructor than Caerdinn, who had hated all Iceriders and Kahiera above the rest. From that time until his arrival at Frost Fell, she had seen Kahiera’s son barely a score of times.

Riding up the fell now, she saw him in her mind as she had seen him then—cocky, quirky, aggressive, the scourge of maidens in five villages … And angry. It was his anger she remembered most, and the shy fleeting sweetness of his smile.

“Place needs thatching,” he remarked now, standing in Battlehammer’s stirrups to pull a straw from the overhang of the roof. “According to Dotys’ Catalogues, villagers on the Silver Isles used to braid straw into solid tiles and peg ’em to the rafterwork, which must have been gie heavy. Cowan”—the head stableman at the Hold—“says it can’t be done, but I’ve a mind to try this summer, if I can find how they did the braiding. If we’re all still alive by haying, that is.” Chewing the straw, he dropped from the warhorse’s back, looped the rein around the gate, and trailed Jenny and Ian into the house. “Garn,” he added, sniffing. “Why is it no matter what kind of Weirds you lay around the house, Jen, to keep wanderers from even seein’ the place, mice always seem to get in just fine?”

Jenny flashed him a quick glance by the soft blue radiance of the witchlight she called and bent to pull from under the bed the box of herbs she kept there. Hellebore, yellow jessamine, and the bright red caps of panther-mushroom, carefully potted in wax-stoppered jars. Jars and box were written around with spells, as the house walls were written, to keep intruders away, but there were two mice dead under the bed nevertheless.

Jenny traced the box with her blunt brown fingertips, automatically undoing the wards she had woven. Calabash gourds from the south contained the heads of water-vipers and the dried bodies of certain jellyfish. Nameless leaves were tied in ensorcelled thread, and waxed-parchment packets held deadly earths and salts. On the other side of the room Ian hunted among the few books still on the shelf; John caught Jenny around the waist, tripped her and tossed her onto the old flattened mattress, grinning impishly as she flung a spell across the room to keep Ian unaware of his parents’ misbehavior …

“Behave yourself.” She wriggled from his grasp, giggling like a village girl.

“It’s been too long since we’ve come here.” He let her up, but held her with one arm on either side of her, hands grasping the rough bedpost behind her back. Though only a little over medium height himself, John was easily a foot taller than she; the witchlight flashed silvery in his spectacles and in the twinkle of his eyes.

“And whose fault is that?” She kept her voice low—Ian was still preoccupied with his search. “I wasn’t the one who made stinks and messes and explosions in quest of self-igniting kindling all spring. I wasn’t the one who had to try to make a flying machine from drawings he’d found in some old book …”

“That was Heronax of Ernine,” protested John. “He flew from Ernine to the Silver Isles in it—wherever Ernine was—and I’ve gie near got the thing working properly now. You’ll see.”

He gathered her hair up in his hands, an overflowing double handful of oceanic night, and bent to kiss her lips. His body pressed hers to the tall, smooth-hewn post, and her hand explored the leather of his doublet, the rough wool of the dull-colored plaid wrapped over his shoulder, the hard muscle beneath the linen sleeve. Ian apparently bethought himself of some ingredient hidden inexplicably in the garden, for he wandered unseeing outside; the scents of the old house wrapped them around, moldy thatch and mice and the wild whisper of summer night in the Winterlands.

The heat of her body’s changing whispered to her, and she whispered back, Go away. It was not just the little cantrips, the knots of warding and change, that turned aside those migraines, those flashes of moodiness, those alien angers. It was this knowledge, this man, the lips that sought hers and the warmth of his flesh against her. The joy of a girl who had been ugly, who had been scorned and stoned in the village streets, who had been told, You’re a witch and will grow old alone.

The knowledge that this was not true.

Later she breathed, “And your dragon-slaying machine.”

“Aye, well.” He straightened from hunting her fallen hairpins, and the hard line returned to crease the corner of his mouth. “That’s near done, too. More’s the pity I spent this past winter tryin’ to learn to fly instead.”

Early in the morning Jenny kindled fire under the cauldrons that Sergeant Muffle had set up in the Hold’s old barracks court. She fetched water from the well in the corner and spent the day brewing poisons to put on the ensorcelled harpoons. In this she accepted Ian’s help, and John’s, too, and it was all John’s various aunts could do to keep Adric and Mag from stealing into the court and poisoning themselves in the process of lending a hand. By the late-gathering summer twilight they were dipping the harpoons into the thickened black mess, and the messenger from Skep Dhû joined them in the court.

“It isn’t just the garrison that relies on that herd,” the young man said, glancing, a little uncertainly, from the unprepossessing, bespectacled form of the Dragonsbane, stripped to a rather sooty singlet, doeskin britches, and boots, to that of the Witch of Frost Fell. His name was Borin, and he was a lieutenant of cavalry at the garrison, and like most southerners had to work very hard not to bite his thumb against evil in Jenny’s presence. “The manors the Regent is trying to establish to feed all the new garrisons depend on those cattle as well, for breeding and restocking. And we lost six, maybe eight bulls and as many cows, as far as we can gather—the carcasses stripped and gouged, the whole pasture swept with fire.”

John glanced at Jenny, who could almost read his thoughts. Fifteen cattle was a lot.

“And you got a good look at it?”

Borin nodded. “I saw it flying away toward the other side of the Skepping Hills. Green, as I said to you last night. The spines and horns down its back, and the barb on its tail, were crimson as blood.”

There was a moment’s silence. Ian, on the other side of the court, carefully propped two of the harpoons against the long shed that served John as a workroom; Sergeant Muffle leaned against the side of the beehive-shaped clay furnace in the center of the yard and wiped the sweat from his face. John said softly, “Green with crimson horns,” and Jenny knew why that small upright line appeared between his brows. He was fishing through his memory for the name of a star-drake of those colors in the old dragon-lists. Teltrevir, heliotrope, the old list said, the list handed down rote from centuries ago, compiled by none knew whom. Centhwevir blue, knotted with gold.

“Only a dozen or so are on the list,” said Jenny quietly. “There must be dozens—hundreds—that are not.”

“Aye.” He moved two of the harpoons, a restless gesture, not meeting her eyes. “We don’t even know how many dragons there are in the world, or where they live—or what they eat, for that matter, when they’re not makin’ free with our herds.” His voice was deep, like scuffed brown velvet; Jenny could sense him drawing in on himself, gathering himself for the fight. “In Gantering Pellus’ The Encyclopedia of Everything in the Material World it says they live in volcanoes that are crowned with ice, but then again Gantering Pellus also says bears are born shapeless like dough and licked into shape by their fathers. I near got meself killed when I was fifteen, findin’ out how much he didn’t know about bears. The Liever Draiken has it that dragons come down from the north …”

“Will you want a troop of men to help you?” asked Borin. In the short time he’d been at the Hold he’d already learned that when the Thane of the Winterlands started on ancient writings it was better to simply interrupt if one wanted anything done. “Commander Rocklys said she could dispatch one to meet you at Skep Dhû.”

John hesitated, then said, “Better not. Or at least, have ’em come, but no nearer than Wormwood Ford. There’s a reason them old heroes are always riding up on the dragon’s lair by themselves, son. Dragons listen, even in their sleep. Just three or four men, they’ll hear ’em coming, miles off, and be in the air by the time company arrives. If a dragon gets in the air, the man going after it is dead. You have to take ’em on the ground.”

“Oh.” Borin tried hard to look unconcerned about this piece of news. “I see.”

“At a guess,” John added thoughtfully, “the thing’s laired up in the ravines on the northwest side of the Skepping Hills, near where the herd was pastured. There’s only one or two ravines large enough to take a dragon. It shouldn’t be hard to figure out which. And then,” he said grimly, “then we’ll see who gets slain.”

TWO (#ulink_c6fcc37f-68a4-5d36-8137-5531371a2bbe)

IT WAS A ride of almost two days, east to the Skepping Hills. John and Jenny took with them, in addition to Borin and the two southern soldiers who’d ridden with him—a not-unreasonable precaution in the Winterlands—Skaff Gradely, who acted as militia captain for the farms around Alyn Hold, and two of Jenny’s cousins from the Darrow Bottoms, all of whom were unwilling to leave their farms this close to haying-time but equally unwilling to have the dragon move west. Sergeant Muffle was left in command of the Hold.

“There’s no reason for it,” argued Borin, who appeared to have gotten the Hold servants to launder and press his red military tunic and polish his boots. “There’s been no sign of bandits this spring. Commander Rocklys has put this entire land under law again, so there’s really no call for a man to walk armed wherever he goes.” He almost, but not quite, looked pointedly at Gradely and the Darrow boys, who, as usual for those born and bred in the Winterlands, bristled with knives, spiked clubs, axes, and the long slim savage northern bows. Jenny knew that in the King’s southern lands, farmers did not even carry swords—most of the colonists who had come in the wake of the new garrisons were, in fact, serfs, transplanted by royal fiat to these manors and forbidden to carry weapons at all.

“There’s never any sign of bandits that’re good at their jobs.” John signaled a halt for the dozenth time and dismounted to scout, though by order of the Commander of the Winterlands, roads in this part of the country had been cleared for a bow shot’s distance on either side. In Jenny’s opinion, whoever had done the clearing had no idea how far a northern longbow could shoot.

Borin said, “Really!” as John disappeared into the trees, his green and brown plaid mingling with the colors of the thick-matted brush. “Every one of these stops loses us time, and …”

Jenny lifted her hand for silence, listening ahead, around, among the trees. Stretching out her senses, as wizards did. Smelling for horses. Listening for birds and rabbits that would fall silent at the presence of man. Feeling the air as a wealthy southern lady would feel silk with fingers white and sensitive, seeking a flaw, a thickened thread …

Arts that all of Jenny’s life, of all the lives of her parents and grandparents, had meant the difference between life and death in the Winterlands.

In time she said, quietly, “I apologize if this seems to discount Commander Rocklys’ defenses of the Realm, Lieutenant. But Skep Dhû is the boundary garrison in these parts, and beyond it, the bandit troops might still be at large. The great bands, Balgodorus Black-Knife’s, or that of Gorgax the Red, number in hundreds. If I know them, they’ve been waiting all spring for a disruption such as a dragon would cause to raid the new manors while your captain’s attention is elsewhere.”

The lieutenant looked as if he would protest, then simply looked away. Jenny didn’t know whether this was because she carried her own halberd and bow slung behind Moon Horse’s saddle—women in the south did not customarily go armed, though there were some notable exceptions—or because she was a wizard, or for some other reason entirely. Many of the southern garrisons were devout worshipers of the Twelve Gods and regarded the Winterlands as a wilderness of heresy. In any case, disapproving silence reigned for something like half an hour—Gradely and the Darrow boys sitting their scrubby mounts ten or twelve paces away, scratching under their plaids and picking their noses—until John returned.

They camped that night in the ruins of what had been a small village or a large manor farm three centuries ago, when the Winterlands still supported such things. A messenger met them there with word that the dragon was in fact laired in the largest of the ravines east of the Skepping Hills—“The one with the oak wood along the ridge at its head, my lord”—and that Commander Rocklys had personally led a squadron of fifty to meet them at Wormwood Ford.

“Gaw, leavin’ who to garrison Cair Corflyn, if they get themselves munched up?” demanded John, horrified. “You get back now, son, and tell the lot of ’em to stay put. Do they think this is a bloody fox-hunt? The thing’ll hear ’em coming ten miles off!”

The second night they made camp early, while light was still high in the sky, in a gully just west of the Skepping Hills. Beyond, the northern arm of the Wood of Wyr lay thick, a land of knotted trees and dark, slow-moving streams that flowed down out of the Gray Mountains, a land that had never been brought under the dominion of the Kings. Lying with John under their spread-out plaids, Jenny felt by his breathing that he did not sleep.

“I hate this,” he said softly. “I’d hoped, after meeting Morkeleb—after speaking with him, touching him … hearing that voice of his speak in me mind—I’d hoped never to have to go after a dragon again in me life.”

Jenny remembered the Dragon of Nast Wall. “No.”

He sat up, his arms wrapped around his knees, and looked down at her, knowing how her own experience of the dragon-kind had touched her. “Don’t hate me for it, Jen.”

She shook her head, knowing that she so easily could. If she didn’t understand about the Winterlands, and about what it was to be Thane. “No.” John loved wolves, too, and studied every legend, every hunter’s tale: he’d built a blind for himself so he could sit and watch them for hours at their howlings and their hunts. He’d drive them away sooner than kill them, if they preyed on the cattle. But he’d kill them without compunction if he had to.

He was Thane of the Winterlands, as his father had been. He could no more turn his back on a fight with a dragon than he could turn his back should a bandit chief, handsome and wise as the priests said gods were, start raiding the farms.

Jenny supposed that if a god were to come burning the fields and killing the stock, exposing the people to the perils of these terrible lands, John would read everything he could on the subject, pick up whatever weapon seemed appropriate, and try to take it on.

The fact that he’d never wanted any of this was beside the point.

An hour after midnight he rose for good, ate cold barley bannocks—none of them had been so foolish as to suggest cooking, within a few miles of a dragon’s lair—and armed himself in his fighting doublet, his close-fitting helmet, and iron-backed gloves. Jenny knew that dragons were neither strictly nocturnal nor diurnal, but woke and slept like cats; still, she also knew that most dragons were aground and asleep in the hours just before dawn. She flung a little ravel of witchlight close to the ground, just enough for the horses to see the trail, and led the way toward the razor-backed hunch of the Skepping Hills and the oak-fringed ravine.

Mist swirled around the knees of the horses, floated like rags of silk among the heather. They left Borin on the edge of the heath, to watch from afar. Stretching her senses, Jenny felt everywhere the tingle and touch of magic. Had the dragon summoned these unseasonable mists for protection? she wondered. Would it sense her, sense them, if she raised a counterspell to send them away?

For a star-drake’s body to be simply of one color, she thought, it must be either very young or very old, and if very old, its senses would fill the lands around, like still water that would carry the slightest ripple to its dreams. But this she did not feel. She had sensed Morkeleb’s awareness when she and John had first ridden to do battle with the black dragon under the shadows of the Deep of Ylferdun … The red horns and spikes and tail seemed to argue for a young dragon anyway, but would a youngster be large enough to be mistaken for something a hundred feet long?

She touched John’s wrist and whispered, though they were close enough now to the head of the ravine to need absolute silence, “John, wait. There’s something wrong.”

The ravine before them was a drift of gray mist. His spectacles, framed by his helmet, glinted like the eyes of an enormous moth. In a hunter’s whisper, he asked, “Can it hear us? Feel us?”

“I don’t know. But I don’t … I don’t feel it. At all.”

He tilted his head, inquiring.

“I don’t know. Get ready to run or to charge.”

Then she reached out with her mind, her will, her dragonheart and dragon-spells, and tore the mists from the ravine in a single fierce swirl of chilling wind.

The slice and flash of early light blinked on metal in the oak woods above the ravine, and a second later something came roaring and flapping up from between the hills: green, red-horned, bat-winged, snake-headed, serpentine tail tipped with something that looked like a gargantuan crimson arrowhead and absolutely unlike any dragon Jenny had ever seen outside the illuminations of John’s old books. John said, “Bugger all!” and Jenny yelled, “John, look out, it’s an illusion …!”

Unnecessarily, for John was turning already, sword drawn, spurring toward the nearest cover. Jenny followed, flinging behind her a blast and hammer of fire-spells, ripping up from the heather between them and the riders that galloped out of the woods.

Bandits. The illusory dragon dissolved in midair the moment it was clear that neither John nor Jenny was distracted by its presence, and the bearded attackers in makeshift panoplies of hunting leathers and stolen mail converged on the cut overhang of a streambank that provided the only defensible ground in sight.

Jenny followed the fire-spells with a sweeping Word of Poor Aim, and to her shock felt counterspells whirl and clutch at her. Beside her, John cursed and staggered as an arrowhead slashed his thigh. She felt fire-spells in the air around them and breathed Words of Limitation and counterspells herself, distracting her mind from her own magics. Behind the spells she felt the mind of the wizard: an impression of untaught power, of crude talent without training, of enormous strength. She felt stunned, as if she’d walked into a wall in darkness.

John cursed again and nocked the arrows he’d pulled down with him when he’d dismounted; at least, thought Jenny, casting her mind to the head of the stream that the outlaws would have to cross to get at them, their attackers could only come at them from two sides. She tried to call back the mists, to make them work for her and John as they’d concealed the bandits before, but again the counterspells of the other wizard twisted and grabbed at her mind. Fire in the heather, at the same time damping the fire-spells that filled the cut under the bank with smoke; spells of breaking and damage to bowstrings and arrows …

And then the bandits were on them. Illusion, distraction—Jenny called them into being, worked them on the filthy, scarred, furious men who waded through the rising stream. Swords, pikes, the hammering rain of slung stones, some of which veered aside with her warding-spells, some of which punched through them as if they had not been there. A man would stop, staring about him in confusion and horror—Jenny’s spells of flaring lights, of armed warriors around herself and John taking effect … John’s sword, or Jenny’s halberd, would slash into his flesh. But as many times as not the man would spring back with a cry, seeing clearly, and Jenny would feel on her mind the cold grip of the other mage’s counterspell. Illusion, too, she felt, for there were bandits who simply dissolved as the illusion of the dragon had dissolved …

And through it all she thought, The bandits have a wizard! The bandits have a wizard with them!

In John’s words: bugger, bugger, bugger.

Jenny didn’t know how long they held them off. Certainly not much longer than it would take to hard-boil an egg, though it seemed far longer. Still, the sun had just cleared the Skepping Hills when she and John first saw the bandits, and when the blare of trumpets sliced golden through the ruckus and Commander Rocklys and her troops rode out of the hills in a ragged line, the shadows hadn’t shortened by more than a foot. Jenny felt the other wizard’s spells reach out toward the crimson troopers and threw her own power to intercept them, shattering whatever illusions the rescuers would have seen and attacked. Rocklys, standing in her stirrups, drew rein and fired into the thick of the outlaw horde; Jenny saw one of the leaders fall. Then a great voice bellowed, “Out of it, men!” and near the head of the ravine a tall man sprang up on a boulder, massive and black-bearded, like a great dirty bear.

John said, “Curse,” and Rocklys, whipping another arrow to her short black southern bow, got off a shot at him. But the arrow went wide—Jenny felt the Word that struck it aside—and then battle surged around them, mist and smoke rising out of the ground like dust from a beaten rug. The spells she’d called onto the stream were working now and the water rushed in furious spate, sweeping men off their feet, the water splashing icy on John’s boots and soaking the hem of Jenny’s skirt. Then the bandits fled; Rocklys and her men in pursuit.

“Curse it,” said John. “Balgodorus Black-Knife, damn his tripes, and they had a wizard with ’em, didn’t they, love?” He leaned against the clay wall of the bank, panting; Jenny pressed her hand against his thigh, where the first arrowhead had cut, but felt no poison in the wound.

“Somebody who knew enough about dragon-slaying to know we’d have to attack it alone, together.”

“Maggots fester it—ow!” he added, as Jenny applied a rough bandage to the wound. “Anybody’d know that who’s heard me talk about it, or talked to someone who had. Anyway, it wasn’t me they was after, love.” He reached down and touched her face. “It was you.”

She looked up, filthy with sweat and soot, her dark hair unraveled: a thin small brown woman of forty-five, flushed—she was annoyed to note—with yet another rise of inner heat. She sent it away, exasperated at the untimeliness and the reminder of her age.

“Me?” She got to her feet. The rush of the stream was dying as quickly as it had risen. Bandits slain by John’s sword, or her halberd, or by the arrows of Rocklys’ men, lay where the water had washed them.

“You’re the only mage in the Winterlands.” John tucked up a wet straggle of her hair into a half-collapsed braid, broke off a twig from a nearby laurel bush and worked it in like a hairpin to hold it in place. “In the whole of the King’s Realm, for all I know. Gar”—that was the Regent—“told me he’s been trying to find wizards in Bel and Greenhythe and all around the Realm, and hasn’t located a one, bar a couple of gnomes. So if a bandit like Balgodorus Black-Knife’s got a wizard in his troop, and we have none …”

“We’d have been in a lot of trouble,” Jenny said softly, “had this ambush succeeded.”

“And it might have,” mused John, “if their boy—”

“Girl.”

“Eh?”

“Their mage is a woman. I’m almost certain of it.”

He sniffed. “Girl, then. If their girl had known the first thing about star-drakes, beyond that they have wings and long tails, you might not have twigged soon enough to keep us out of the jaws of the trap. Which goes to demonstrate the value of a classical education …”

Commander Rocklys returned in a clatter of hooves, Borin at her side. “Are you all right?” She sprang down from her tall bronze-bay warhorse, a lanky powerful woman of thirty, gold-stamped boots spattered with mud and gore. “We were saddled and ready to ride to your help with the dragon when Borin charged into camp shouting you were being ambushed.”

“The dragon was a hoax,” John said briefly. He wiped a gout of blood from his cheekbone and scrubbed his gloved fingers with the end of his plaid. “Better if it had been a real drake than what’s really going on.”

Rocklys of Galyon listened, arms folded, to his account. It was a rare woman, Jenny knew, who could get men to follow her into combat; on the whole, most soldiers knew of women only what they saw of their victims during the sack of farmsteads or towns, or what they learned from the camp whores. Some, like John, were willing to learn different. Others had to be strenuously taught. Though the women soldiers Jenny had met—mostly bandits—tended to gang together to protect one another in the war camps, a woman commander as a rule had to be large and strong enough to take on and beat a good percentage of the men under her command.

Rocklys of the House of Uwanë was such a woman. The royal house of Bel was a tall one, and she was easily John’s nearly six-foot height, with powerful arms and shoulders that could only have been achieved by the most strenuous physical training. As a cousin of the King, Jenny guessed she would have been granted a position as second-in-command or a captaincy of royal guards regardless, but it was clear by the set of her square chin that an honorary post was not what she wanted.

For the rest, she was fair-haired, like her cousin the Regent Gareth—though the last time Jenny had seen Gareth, two years ago, he’d still affected a dandy’s habit of dyeing portions of his hair blue or pink or whatever the fashionable shade was that year. Her eyes, like Gareth’s, were a light, cold gray. She neither interrupted nor reacted to John’s tale, only stood with the slight breezes moving the gold tassels on her sword-belt and on the red wool oversleeves that covered her linen shirt. At the end of his recital she said, “Damn it.” Her voice was a sort of husky growl, and Jenny guessed she’d early acquired the habit of deepening it. “If I’d known there was a wizard with them I’d never have called off the men so soon. You’re sure?”

“I’m sure.” Jenny stepped up beside John. “Completely aside from the green dragon, which was sheer illusion—only created to lure John and me—I could feel this mage’s mind, her power, with every spell I tried to cast. There’s a wizard with Balgodorus, and a strong one.”

“Damn it.” Rocklys’ mouth hardened, and for a moment Jenny saw a genuine fury in her eyes. Then they shifted, thoughtful, considering the two people before her: the bloodied and shabby Dragonsbane and the Witch of Frost Fell. Jenny knew the look in her eyes, for she’d seen it often in John’s. The look of a commander, considering the tools she has and the job that needs to be done.

“Lady Jenny,” she said. “Lord John.”

“Now we’re in trouble.” John looked up from polishing his spectacles on his shirt. “Anytime anyone comes to me and says …” He shifted into an imitation of that of the Mayor of Far West Riding, or one of the councilmen of Wrynde, when those worthies would come to the Hold asking him to kill wolves or deal with bandits, “‘Lord John’—or worse, ‘Your lordship.’”

Commander Rocklys, who didn’t have much of a sense of humor, frowned. “But we are in trouble,” she said. “And we shall be in far worse trouble should Balgodorus Black-Knife continue at large, with a witch …” She hesitated—she’d used a southern word for the mageborn that had pejorative connotations of evil and slyness—and politely changed it. “… with a wizard in his band. Surely you agree.”

“And you want our Jen to go after ’em.”

Rocklys looked a little surprised to find her logic so readily followed. As if, thought Jenny, the necessity for her to pursue the renegade mage was not obvious to all. “For the good of all the Winterlands, you must agree.”

John glanced at Jenny, who nodded slightly. He sighed and said, “Aye.” The good of all the Winterlands had ruled his life for twenty-two years, since his father’s death. Even before that, when as his father’s only son he had been torn from his books and his music and his tinkerings with pulleys and steam, and had a sword thrust into his hand.

Four years ago it had been the good of all the Winterlands that took him south, to barter his body and bones in the fight against Morkeleb the Black, so the King would in return send troops to garrison those lost territories and bring them again under the rule of law.

“Aye, love, you’d best go. God knows if you don’t we’ll only have ’em besiegin’ the Hold in the end.”

“Good.” Rocklys nodded briskly, though she still looked vexed. “I’ve already sent one of the men back to Skep Dhû, with orders to outfit a pack-train, Lady Jenny; you’ll ride with twenty-five of my men here.”

“Twenty-five?” said John. “There were at least twenty in the band that attacked us, and rumor has it Balgodorus commands hundreds these days.”

Rocklys shook her head. “My scouts report no more than forty. Untrained men at that, scum and outlaws, no match for disciplined troops.

“If at all possible,” she went on, “bring the woman back alive. The Realm needs mages, Lady Jenny. You know that, you and I have talked of this before. It is only the most appalling prejudice that has caused wizardry to fall into disrepute, so that the Lines of teaching died out or went underground. I am told the gnomes have wizards: that alone should have convinced my uncle and his predecessors to foster, rather than forbid, the study of those arts. Instead, what did they do? Simply crippled themselves, so that four years ago when an evil mage like the Lady Zyerne rose up, no one was prepared to deal with her. That situation cannot be allowed to repeat itself. Yes, Geryon?”

She turned as an orderly spoke to her; John put his hands on Jenny’s shoulders.

“Will you be all right?” she asked him, and he bent to kiss her lips. She tasted blood on his, and sweat and dirt; he must have tasted the same.

“Who, me? With Muffle and Ian and me aunties to defend the Hold if we’re attacked? Nothing to it.” Deadpan, he propped his spectacles more firmly onto the bridge of his long nose. “Shall I send a messenger after you with your good shoes and a couple of silk dresses just in case you want a change?”

“I’ll manage with what I have,” said Jenny gravely. “Borin was right, you know,” she added. “The garrisons may be a nuisance, and the farmers may grumble about the extra taxes, but there hasn’t been a major bandit attack since their coming. I’ll scry you, and the Hold, in my crystal every night—a pity Ian’s powers haven’t grown strong enough yet for him to learn to speak with me through a crystal or through fire. But he’s a fair healer already. And if there’s trouble …” She raised her hand, touched the long hair where it straggled, pointy with sweat, over his bruised face. “Braid a red ribbon into your hair. I’ll see it when I call your image. If I can, I’ll return to you.”

John caught her hand as she would have lowered it and kissed her dirty fingers; and she drew down his in return, pressed her lips to the scruffy leather, the battered chain-mail of his glove. Skaff Gradely and the Darrow boys had come up by this time, arguing all the way with Borin’s fellow messengers, with the spare horses and the baggage, so there was little to stay for.

“Borin will ride with you,” Commander Rocklys said, “and his fellows. Send one of them to me when you’ve come up with these bandits and their wizard. Let us know where you are and if you need troops. I’ll dispatch as many as I can, as swiftly as I can. And bring the woman alive, at whatever the cost. We’ll make it worth her while to pledge her services to the Realm.”

“Even so.” Jenny swung to Moon Horse’s saddle again and adjusted her halberd and bow. She wondered what reward she herself would consider “worth her while” to betray John, to turn against him, to ride with his foes …

Or, she thought, as the twenty-five picked pursuers formed up around her, to leave him and our children and the folk of Alyn Hold to their own devices, when I know there’s a bandit wizard abroad in the lands?

The good of all the Winterlands, maybe.

The good of the Realm, which John considered his first and greatest loyalty.

She lifted her hand to him as she and the men rode off. A little later, as they crested the rise above the ravine and approached the oak woods into which the bandits had fled, she looked back to see Commander Rocklys marshaling her forces to ride back to Cair Corflyn, the garrison on the banks of the Black River, which was the headquarters for the whole network of new manors and forts. John’s doing, those garrisons, she thought. The protection he had bought with the blood he’d shed, dragon-fighting four years ago. His reward.

As the dragon-magic in her veins was hers.

John himself stood, a small tatty black figure on the high ground above the stream, watching her. She lifted her hand again to him, and his spectacles flashed like mirrors as he waved good-bye. The wasting moon still stood above the moors to the west, a pale crescent like a slice of cheese.

Less than three weeks later, before that moon waxed again to its full, a real dragon descended on the farms near Alyn Hold.

THREE (#ulink_bee18f69-ec21-5fe2-bab9-d13081ad82e9)

“A HUNDRED FEET long it was, my lord.” Deke Brown from the Lone Steadings, a man John had known all his life, folded his hands together before his knees and leaned forward from the library chair in the flicker of the candlelight. His face was bruised, and there was a running burn on his forehead, the kind John knew was made by a droplet of the flaming acid that dragons spit. “Blue it was, but like as if it had gold flowers spread all over it, and golden wings, and the horns of it all black and white stripes, and maned like a lion. It had three of the cows, and I bare got April and the babies out’n the house and in the root cellar in time.”

In the silence John was very conscious of the hoarseness of the man’s breathing, and of the thumping of his own heart.

No illusion this time. Or a damn good one if it was.

Jenny, wherever you are, I need you. I can’t handle this alone.

“I heard down in the village that Ned Wooley was up here yesterday, from Great Toby.” Brown spoke diffidently, trying to word it without sounding accusing. “They said this thing killed his horse and his mule on the road to the Bottom Farms, and near as check killed him.”

John said, “Aye.” He swallowed hard, feeling very cold inside. “We’ve been makin’ up the poisons and gettin’ ready to go all day. You didn’t happen to see which way it went?”

“I didn’t, no, my lord. I was that done up about the cows. They’re all we’ve got. But April says it went off northwest. She says to tell you she saw it circling above Cair Dhû.”

“You give April a kiss for me.” He knew the ruins of the old watchtower, every ditch, bank, and clump of broken masonry; he’d played there as a child, risking life and soul because blood-devils haunted them at certain times of the year. He’d hunted rabbits there, too, and hidden from his father. At least I’ll be fighting it on familiar ground. “Get Cousin Dilly to give you something from the kitchen, you look fagged out. I’ll be going there in the morning.”

He drew a deep breath, trying to put the thought of the dragon from his mind. “We’ll see about getting you another cow. One of the Red Shaggies is heavy with calf; I could probably let you have the both of them. Clivy writes that red cows give more wholesome milk that’s higher in butter, but I’ve never measured—still, it’s the best I can do. We’ll talk about it when I get back.”

If I get back.

Brown disappeared down the tower stair.

Jenny, I need you.

Behind him a clock chimed the hour, amid a great parade of mechanical lions, elephants, trumpeters, and flying swans. The moon turned its phases, and an allegorical representation of Good thumped Evil repeatedly over the head with a golden mallet. John watched the show with his usual grave delight, then got up and consulted the water-clock that gurgled quietly in a corner of the study.

Not even close.

Shaking his head regretfully, he descended the tower stair.

He passed the kitchen, where Dilly, Rowan, and Jane clustered around Deke Brown, exclaiming over his few bruises and filling him in on what had befallen Ned Wooley—“A hundred feet long, it was, and breathed green fire …”

Ian was in the old barracks court, the firelight under the cauldrons gleaming on the sweat that sheathed his bare arms. Tawny light tongued Jenny’s red and black poison pots, carefully stoppered and arranged along a wall out of all possible chance of being tripped over, broken, or gotten into by anything or anyone. The fumes burned John’s eyes. It was all a repeat of the scene three weeks ago.

He hoped to hell the stuff would work.

“Father.” The boy laid his stirring stick down and crossed the broken and weedy pavement toward him. Muffle and Adric put down their loads of wood and followed, stripped, like Ian, to their breeches, boots, and knitted singlets in the heat; clothed like Ian in sweat. “That messenger wasn’t …?”

“Deke Brown. It hit his farm.”

“Devils bugger it,” Muffle said. He hitched his belt under the muscled roll of his huge belly. “April and the children …?”

“Are fine. April saw the thing to ground at Cair Dhû.”

“Good for April.” John’s half-brother regarded him for a moment, his thick, red-stubbled face eerily like their father’s, trying to read his thoughts. “No word from Jenny?”

John shook his head, his own face ungiving: a holdover, he supposed, from growing up with his father’s notions about what a man and the Lord of Alyn Hold must and must not feel. It would never have occurred to him to beat Adric for showing fear—not that Adric had the slightest concept of what the word meant. And Ian …

Mageborn children feared different things.

“Wherever she is, she can’t come.” The bloody light darkened the red ribbon he’d braided yesterday into his hair. I’ll scry every evening in my crystal … “Or she can’t come in time.”

“I could go to the house on Frost Fell.” Ian wiped his face with the back of his arm. “Mother’s books—old Caerdinn has to have written down how to do …” he hesitated, “how to do death-spells.”

“No.” John had thought of that yesterday.

“I don’t think these poisons are going to work against a dragon unless there are fresh death-spells put into their making.” Returning from the false alarm and ambush, John had cleansed the harpoons with water and with fire, as Jenny had instructed him to do: a necessary precaution given little Mag’s eerie facility with locks, bolts, and anything else she was particularly not supposed to get into. Jenny, he knew, was conscientious about the Limitations she put on the death-spells. It had never occurred to either of them that they’d be needed again so soon. “We need to put death-spells on the harpoons as well.”

“No.” John had thought of that, too. “I don’t want you touching such stuff.”

“But we don’t want you to die!” protested Adric reasonably.

Muffle raised his brows and looked away in a fashion that said, The boy’s got a point.

“Mother uses them.”

“You’re twelve years old, Ian.” John swallowed hard, hoping by all the gods that his own fear didn’t show. “Leavin’ out the fact that certain spells can be too strong for an inexperienced mage to wield—”

“I’m not inexperienced.”

“—you haven’t learned near all there is to know about Limitations, and I for one don’t want to end up havin’ one of me feet fall off from leprosy in the middle of the fight because you got a word wrong.”

Surprised into laughter, Ian looked quickly aside, mouth pursed to prevent it. Like many boys he had the disapproving air of one who feels that laughter is not the appropriate response to facing death, especially not for one’s father. John had suspected for some time that both his sons regarded him as frivolous.

“Now, get back to stirring,” he ordered. “Is that stuff settin’ up at all like it’s supposed to? Adric, as long as you’re down here you might as well stir that other cauldron, but for God’s sake put gloves on … We’ve got a long night.” He stripped off his old red doublet and his shirt and hung both on pegs on the work shed wall. The smell of summer hay from the fields beyond the Hold filled the night. Though midnight lay only a few hours off, the sky still glowed with light. As he pulled on his gloves, John watched them all in the firelit court: his sons, his brother—his aunts, Jane and Rowe and Hol, and Cousin Dilly, coming down with gingerwater and trying to tell Adric it was time for him to go to bed. Seeing them as Jenny would be seeing them, wherever the hell she was, gazing into her crystal. Rowe with her long untidy braids of graying red and Dilly peering shortsightedly at Muffle, and all of them chatting like a nest of magpies—the real rulers, if the truth be told, of Alyn Hold.

She has to know what all this means. He closed his eyes, desperately willing that Jenny be on her way. I’m sorry. I waited as long as I could.

Teltrevir, heliotrope … His mind echoed the fragments of the old dragon-list. Centhwevir is blue knotted with gold. Nymr blue violet-crowned, Glammring Gold-Horns bright as emeralds … Scraps of information and old learning:

Maggots from meat, weevils from rye,

Dragons from stars in an empty sky.

And, Save a dragon, slave a dragon.

Secondhand accounts, most of them a mash of broken half-volumes; notes of legends and granny rhymes; jumbled ballads that Gareth collected and sent copies of. Everything left of learning in the Winterlands, after the King’s armies had abandoned them to bandits, Iceriders, cold, and plague. He’d gathered them painfully from ruins, collated them in those few moments between fighting for his own life and the lives of those who depended on him … Secondhand accounts and the speculations of scholars who’d never come closer to a dragon than the sites of old slayings, or a nervously cursory inspection of torn-up, blood-soaked, acid-burned ground.

Something in there might save his life, but he didn’t know what.

Antara Warlady was supposed to have gotten right up next to the Worm of Wevir by wrapping herself in a fresh-flayed pig hide, according to the oldest Drymarch version of her tale; Grimonious Grimblade had supposedly put out live lambs as bait.

Alkmar the Godborn had been killed by the third dragon he fought.

Selkythar of golden curls and sword of sunlight flashing,

Seeking meed of glory through the dragon’s talons lashing.

Cried he, “Strike again, foul worm, my bloody blade is slashing …”

John shook his head. He’d never sought a meed of glory in his life, and if he ever decided to start, it wouldn’t be by riding smack up a long hill in open daylight as Selkythar had reportedly done, armed with only a sword—well, a shield, too, as if a shield ever did any good against a thirty-foot hellstorm of spitting acid and whirling spikes.

“The boy may be right.” Muffle’s voice pulled him out of his memories of the Dragon of Wyr, of Morkeleb’s black talons sweeping down at him from darkness …

John dipped the harpoon he held into the cauldron and watched the liquid drip off the iron, thin as water.

“Stuff ain’t thickenin’ up,” he sighed. “Maybe I should get Auntie Jane back here. Her gravies always set.”

Muffle caught his arm. “Be serious, son.”

“Why?” John rested the harpoon’s spines on the vat’s edge and coughed in the smoke. “I may be dead twenty-four hours from now.”

“So you may,” replied the blacksmith softly, and glanced across at Ian in the amber glare. “And what then? Four years ago you bargained with the King to send garrisons. Well, they’ve been gie helpful, but you know there’s a price. If you die, d’you think your boys are going to be let to inherit? In the south they’ve laws against wizards holding property or power, and Adric’s but eight. You think the King’s council’s going to let a witch be Regent of Wyr? Especially if they think they can get tax money by ruling here themselves?”

“I’m the King’s subject.” John stepped back from the fire, hell-mouth hot on his bare arms. “And the King’s servant, and the Regent’s me friend. What’re you askin’? That I not fight this drake?”

“I’m asking that you let Ian do what he’s asked to do.”

“No.”

Muffle pursed his lips, which made him look astoundingly like their father. Except, thought John, that their father had never let things stop with pursed lips, nor would he have reacted to No with that simple grimace. The last time John had said a flat-out No to old Lord Aver, at the age of twelve, he’d been lucky his collarbone had set straight.

“In the village they say the boy’s good. He goes over those magic-books in your library like you go over the ones on steam and smokes and old machines. He knows enough …”

“No,” said John. And then, seeing the doubt, the fear for him in the fat man’s small brown eyes, he said, “There’s things a boy his years shouldn’t know about. Not so soon.”

“Things you’d put your life at risk—your people at risk—to spare him?”

John thought about them, those things Jenny had told him lay in old Caerdinn’s crumbling books. Things he’d read in the books that had been part of his bargain with Prince Gareth to fight the Dragon of Nast Wall. Things he read in Jenny’s silence when he surprised her sometimes in her own small study, studying in the deep of night.

He said, “Aye.” And saw the shift in Muffle’s eyes.

“People hereabouts know the magic Jen does for them.” John picked up the harpoon and turned the shaft in his hands. “Or what old Caerdinn did. Birthin’ babies, and keepin’ the mice out of the barns in a bad year, or maybe buyin’ an hour on the harvest when a storm’s coming in. Those that remember me mother are mostly dead.” He glanced up at Muffle over the rims of his spectacles. “And anyway, by what I hear from our aunties, me mother never did the worst she could have done.”

Except maybe only once or twice, he thought, and pushed those barely coherent recollections from his mind.

“People here don’t know what magic really is,” John went on. “They haven’t seen what it can do, and they haven’t seen what it can do to those that do it. You always pay for it somehow, and sometimes other people besides you do the payin’. Gaw,” he added, turning back to the cauldron and dipping the harpoon once more, “this’s blashier than Cousin Rowanberry’s tea. Let’s put some flour in it, see if we can get it thick enough to do us some good.”

Ian’s heart beat hard as he kicked his scrubby pony to a gallop up Toadback Hill.

Death-spells.

And the dragon.

He’d always hated the harpoons with which his father had killed the Dragon of Wyr, two years before he was born. He had instinctively avoided the cupboard in his father’s cluttered study in which they were locked. If he touched the wood he could feel them, even before he realized that he had magic in him. Sometimes he dreamed about them, each barbed and pronged shaft of iron its own ugly entity, whispering in the darkness about pain and cold and giving up.

His mother had wrought well.

Ian shivered.

For the first eight years of Ian’s life he had only seen her now and then, for she’d lived alone with her cats on the Fell, coming to be with his father at the Hold for a few days together. She had told him later—when his own powers had crossed through that wall from dreaming to daytime reality—that in those days her powers were small. She had kept herself apart to study and meditate, to work on what little she had. There was only so much time in her life to give.

And then had come the Dragon of Nast Wall.

His parents had gone away to the south together to fight it, along with the messenger who’d fetched them, a gawky nearsighted boy in spectacles. That boy had turned out to be Prince Gareth, later Regent for the ailing King Uriens of Belmarie. At that time Ian had accepted without question that his father could easily slay a dragon and hadn’t been particularly concerned. As if to confirm him in this opinion, his parents had returned more or less unharmed, and he didn’t learn until much later how close both had come to not returning at all.

After that, Jenny had lived at the Hold. But she still went sometimes to meditate in the stone house on Frost Fell, and it was there that she’d begun to teach Ian, away from the Hold’s distractions. In that quiet house he did not need to be a brother or a nephew or a father’s firstborn son.

Even had Ian not been mageborn and able to see easily in the clear blue darkness, he could have followed the path that led away from the village fields over Toadback Hill. Ruins dotted the far slope, one of the many vanished towns that spoke of what the Winterlands had been and had become. Shattered walls, slumped puddles where wells had been, all were nearly drowned now in the mists that rose from the cranberry bog.

From the hill crest he looked back and saw his father and his uncle by the village gates, talking with Peg the Gatekeeper. The gates were squat and solid, built up of rubble filched from the broken town. Lanterns burned over them, but Ian did not need those dim yellow smudges to see how his father turned in Battlehammer’s saddle, searching the formless swell of the hills, gesturing as he spoke.

He knows I’m gone. Ian felt a stab of guilt. He’d laid a word on Peg, causing her to rise from her bed in the turret and lower the drawbridge to let him pass. This cantrip wasn’t something his mother had taught him, but he’d learned it from one of Caerdinn’s books and had experimented, mostly on the unsuspecting Adric. He knew perfectly well that such magic was an act of betrayal, of violation, and he squirmed with shame every time he did it, but as a wizard, he felt driven to learn.

He was glad he’d practiced it, now.

It was still too dark to distinguish his pony’s hoofprints in the mud. In any case, he guessed his father had no time to search. Nor had he, Ian, any to linger. He shrugged his old jacket closer around him and put his pony to a fast trot through the battered walls, and the rags of bog mist swallowed them.

Death-spells. His palms grew clammy at the thought. In a corner of his mind he knew perfectly well that he might not have the strength to wield them, certainly not to wield the dreadful power he sensed whenever he touched the harpoons. But he could think of no other way to help. Since the coming of that first word of the dragon yesterday, he’d tried desperately to make contact with his mother in the ways she’d told him wizards could, by looking into fire or water or chips of ensorcelled crystal or glass. But he had seen only confusing images of trees, and once a moss-covered standing stone, and water glimmering in the moon’s waxing light.

Remember the Limitations, he told himself, ticking over his mother’s instructions in his mind. And gather up the power circles afterward and disperse them. Don’t work in a house. Don’t work near water …

There had to be something in the house at Frost Fell that he could use to save his father’s life.

Frost Fell was a hard gray skull of granite, rising nearly two hundred feet above waterlogged bottomlands—enough to be free of the mosquitoes that made the summers of Winterlands such a horror. In spring, huge poppies grew there, and in fall, yellow daisies. Most of the other fells were barren of anything but heather and gorse, but Frost Fell boasted a modest pocket of soil at its top, where centuries ago some hardy crofter had cultivated oats. These days it was his mother’s garden, circled like the house in wardings and wyrd-lines. Ian reviewed these in his mind, hoping he’d be able to get past the gate, hoping he could open the doors. Triangle, triangle, rune of the Eye … The last two times he’d been there she’d simply stood back and let him do it, so there was a chance …

Light burned in the house.

She’s back! Exultation, and blinding relief. A dim glow of candle flame, like a stain on the blue bulk of shadow. The rosy flicker of hearth-fire glimpsed through half-open doors. He wrapped the pony’s rein hastily around the gate, ran up the path. She’s back, she’ll be able to help!

It wasn’t until his foot was on the step that he thought, If it was Mother, she’d have ridden at once to the Hold.

And at that moment, he saw something bright on the step.

He stopped and knelt to look at it. Like a seashell wrought of glass, thin as a bubble, broken at one end. A little beyond the broken end lay what appeared to be a blob of quicksilver, glistening on the wet stone in the reflected candle-glow.

“Go ahead.” A deep, friendly voice spoke from within the house. “It’s all right to touch it. It’s perfectly safe.”

Looking up Ian saw a man sitting by his mother’s hearth, a man he’d never seen before. Big and square and pleasant-faced, he was clothed like the southerners who came from the King’s court, in a short close coat of quilted violet silk lined with fur, and a fur-lined silk cap embroidered with violets. Expensive boots sheathed his calves and a pair of black kid gloves lay across his knee, and in his pale fingers he turned a jewel over and over, a sapphire dark as the sea. Ian knew he had to be a wizard, because he was in the house, but he asked, “Are you a mage, sir?”

“I am that.” The man smiled again and gestured with his finger to the frail glass shell, the bead of quicksilver on the step. “And I’m here to help you, Ian. Bring that to me, if you would, my boy.”

Ian reached toward it and hesitated, for he thought the quicksilver moved a little on the stone of the step. For an instant he had the impression that there were eyes within it, looking up at him. Bright small eyes, like a lizard or a crab. That it had its own name, and moreover that it knew his. But a moment later he thought, It has to be just the light. He carefully scooped the thing up in his hand.

FOUR (#ulink_5c0b3796-9ea5-5752-b4f0-482df6ef305d)

ALKMAR THE GODBORN, greatest of the heroes of antiquity (it was said), slew two dragons while serving the King of Ernine—though according to Prince Gareth there was a late Imperteng version of the legend that said four—using a lasso made of chain and an iron spear heated red-hot, which he threw down each dragon’s throat. Must have been on a cable, thought John, though of course Alkmar had been seven and a half feet tall, thewed like an ox, and presumably had a lot of time to spend at throwing practice.

For someone a thumb’s breadth under six feet and thewed like a thirty-eight-year-old man who’s spent most of his life riding boundary in cold weather, other strategies would probably be required.

John Aversin flexed his shoulders and listened, hoping to hell Sergeant Muffle and the spare horses were keeping absolutely quiet in the base camp at Deep Beck. Was three and a half miles far enough?

Morning stillness lay on the folded world of heather and stone, broken only by the hum of mosquitoes and bees. Even the creak of his stirrup leather seemed deafening, and the dry swish of Battlehammer’s tail.

Interesting that the greatest hero of legend was described as throwing something at the dragon, rather than nobly slicing its head off with a single blow of his mighty sword and to hell with Selkythar and Antara Warlady and Grimonious Grimblade, thank you very much.

Battlehammer snuffled and flattened his ears. Though the wind blew south off the ruins of Cair Dhû, if the stallion could smell the dragon from here, could the dragon smell them?

Or hear them, in the utter absence of the raucous dawn chitter of birds?

Dragonsbane. He was the one who was supposed to know all this.

John flexed his hands. The walls of the gorge still protected him, and the purl of the stream might conceivably cover the clack of Battlehammer’s hooves. The problem with dragons was that, mostly, nobody knew what worked.

He slid from the saddle, checked the girths, checked the harpoons in their holsters. Lifted each of the warhorse’s four feet to make sure he hadn’t picked up a stone. That’s all I’d need. While he did this, in his mind he reviewed the ruins. He’d checked them a few months ago; there couldn’t have been much change. The dragon would be lairing in the crypt.

He’d have to catch it there, before it got into the air.

Stair, hall, doorway, doorway … How fast did dragons move? Morkeleb had come out of the dark of Ylferdun Deep’s great markethall like a snake striking. Broken walls, the drop of a slope, everything tangled with heather and fallen masonry. Ditches invisible where weeds grew across them … What a place for a gallop. At least he knew the ground.

He settled his iron cap tighter on his head, the red ribbon still fluttering in his hair. Jen, I’m in trouble, I need you, come at once.

Though he supposed if she scried him now she’d get the idea without the ribbon.

He propped his spectacles again, dropped his hand back to touch the first of the harpoons in their holsters, and took a deep breath.

“Strike again, foul worm,” he whispered, and drove in his heels.

At five hundred yards, they knew you were coming, upwind, downwind, dark or storm. That seemed to be the consensus of the ballads. Maybe more than five hundred. Maybe a lot more.

Battlehammer hit open ground at a dead gallop and John watched the walls pour toward him: broken stone, stringers of outwalls, craggy pine and dwarf willow spreading around the ground. Everything broken now and burned with dragon-acid and the poisons of its breath. He saw it in his mind, slithering up those shattered stairways. A hundred feet long … God of the Earth, let them be wrong about that …

It was there in the riven gate. Centhwevir is blue knotted with gold. Fifty feet in front of him, rising on long hind legs to swing that birdlike head. Blue as gentian, blue as lapis and morning glories, iridescent blue as the summer sea all stitched and patched and flourished with buttercup yellow, and eyes like twin molten opals, gold as ancient glass. The beauty of it stopped his breath as his hand went back, closed around the nearest harpoon, knowing he was too far yet for a throw and thinking, Sixty feet if it’s an inch …

Centhwevir is blue knotted with gold.

The thing came under the gate and the wings opened and John threw: arm, back, thighs, every muscle he possessed. The harpoon struck in the pink hollow beneath the right wing where the skin was delicate as velvet, and he was reining Battlehammer hard away and angling for distance, catching up another weapon, swinging to throw for the mouth.

Alkmar, if you’re there among the gods, I could use the help …

That one missed as the snakelike neck struck at him, huge narrow head framed in its protective mane of black and white, primrose and cyan. Battlehammer screamed and fell and rolled, lifted from his feet by the hard counterswipe of the dragon’s tail, and John kicked free of the stirrups and tumbled almost by instinct. Yellow-green acid slapped the heather at his feet, the stiff brush bursting into flame.

Battlehammer. He could hear the horse scream again in pain but didn’t dare turn to look, only scooped up four harpoons from the ground—as many as he could reach—and ran in.

Keep it under the gate. Keep it under the gate. If it stays on the ground, you’ve a chance.

The star-drake struck at him again, head and tail, spitting acid that ignited in the air. John flung himself under the shelter of a broken wall, then rolled clear, coming in close, fast, striking up at the rippling wall of blue-and-golden spikes. The heather around them blazed, smoke searing his eyes. The dragon snapped, slashed, drove him back, slithered free of the confining walls. He struck with the harpoon, trying to hold it; talons like gold-bladed daggers snagged his leg, hurling him off balance. He struck up with the harpoon again as the head came down at him, teeth like dripping chisels, the spattering sear of blood.