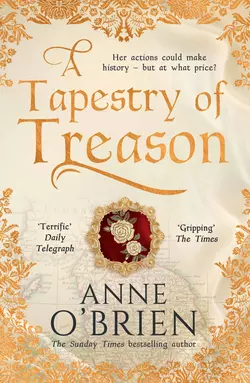

A Tapestry of Treason

Anne OBrien

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1331.15 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘Gripping’ The Times ‘Fans of Philippa Gregory and other historical fiction writers will love Anne O’Brien’s A Tapestry of Treason’ Yours Her actions could make history – but at what price? 1399: Constance of York, Lady Despenser, proves herself more than a mere observer in the devious intrigues of her magnificently dysfunctional family, The House of York. Surrounded by power-hungry men, including her aggressively self-centred husband Thomas and ruthless siblings Edward and Richard, Constance places herself at the heart of two treasonous plots against King Henry IV. Will it be possible for this Plantagenet family to safeguard its own political power by restoring either King Richard II to the throne, or the precarious Mortimer claimant? Although the execution of these conspiracies will place them all in jeopardy, Constance is not deterred, even when the cost of her ambition threatens to overwhelm her. Even when it endangers her new-found happiness. With treason, tragedy, heartbreak and betrayal, this is the story of a woman ahead of her time, fighting for herself and what she believes to be right in a world of men. Praise for A Tapestry of Treason ‘O’Brien’s page-turner vividly brings to life the restriction of women, and the compassion and strength of this real-life figure from medieval times’ Woman ‘Anne O’Brien does not disappoint… there are so many twists and turns… If you love Philippa Gregory or Alison Weir, you will love Anne O’Brien too’ My Weekly ‘A wonderful novel… a rich, gripping, enchanting read. Anne’s vivid writing took me straight to the year 1400 and kept me wonderfully lost there throughout’ Joanna Courtney ‘A detailed portrayal of a fascinating character’ Woman’s Weekly ‘An engaging novel of political intrigue’ Choice Praise for Anne O’Brien ‘O’Brien cleverly intertwines the personal and political in this enjoyable, gripping tale’ The Times ‘O’Brien is a terrific storyteller’ Daily Telegraph ‘A gripping story of love, heartache and political intrigue’ Woman & Home ‘Packed with drama, danger, romance and history … the perfect reading choice for the long winter nights’ The Press Association ‘A gripping historical drama’ Bella