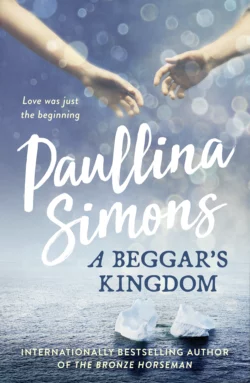

A Beggar’s Kingdom

Pauline Simons

How much would you sacrifice for true love? The second novel in Paullina Simons' stunning End of Forever saga continues the heartbreaking story of Julian and Josephine, and a love that spans lifetimes. Julian has travelled from the heights of joy to the depths of despair and back again. Having found his love – twice – and lost her – twice, he is resolved to continue his search and find her in the past again. Perhaps this time he can save her. But the journey is never so simple and Julian will have to decide just how much one man can sacrifice. He is willing to give up everything – but he must learn what that truly means, and how much more can be taken from you than you ever believed possible.

A BEGGAR’S KINGDOM

The second novel in the End of Forever saga

Paullina Simons

Copyright (#u07b4a1c9-e1f0-52f0-baa5-837cac4532c7)

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

The News Building

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty Ltd in 2019

This edition in Great Britain 2019

Copyright © Paullina Simons

Cover design by HarperCollins Design Studio

Cover images: Hands by Mark Owen / Trevillion Images; Icebergs on the water by Jason Hynes / Getty Images

Part title illustrations by Paullina Simons

Author photo by Paullina Simons

Paullina Simons asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007441679

Ebook Edition © August 2019 ISBN: 9780007441686

Version: 2019-07-09

Praise for Paullina Simons (#u07b4a1c9-e1f0-52f0-baa5-837cac4532c7)

Tully

“You’ll never look at life in the same way again. Pick up this book and prepare to have your emotions wrung so completely you’ll be sobbing your heart out one minute and laughing through your tears the next. Read it and weep—literally.”

Company

Red Leaves

“Simons handles her characters and setting with skill, slowly peeling away deceptions to reveal denial, cowardice and chilling indifference … an engrossing story.”

Publishers Weekly

Eleven Hours

“Eleven Hours is a harrowing, hair-raising story that will keep you turning the pages late into the night.”

Janet Evanovich

The Bronze Horseman

“A love story both tender and fierce” (Publishers Weekly) that “recalls Dr. Zhivago.” (People Magazine)

The Bridge to Holy Cross

“This has everything a romance glutton could wish for: a bold, talented and dashing hero [and] a heart-stopping love affair that nourishes its two protagonists even when they are separated and lost.”

Daily Mail

The Girl in Times Square

“Part mystery, part romance, part family drama … in other words, the perfect book.”

Daily Mail

The Summer Garden

“If you’re looking for a historical epic to immerse yourself in, then this is the book for you.”

Closer

Road to Paradise

“One of our most exciting writers … Paullina Simons presents the perfect mix of page-turning plot and characters.”

Woman and Home

A Song in the Daylight

“Simons shows the frailties of families and of human nature, and demonstrates that there’s so much more to life, such as honesty and loyalty.”

Good Reading

Bellagrand

“Another epic saga from Simons, full of the emotion and heartache of the original trilogy. Summer reading at its finest.”

Canberra Times

Lone Star

“Another epic love story—perfect reading for a long, lazy day in bed.”

Better Reading

Dedication (#u07b4a1c9-e1f0-52f0-baa5-837cac4532c7)

To Kevin,

I can do all things through you who strengthens me.

Epigraph (#u07b4a1c9-e1f0-52f0-baa5-837cac4532c7)

“Guess I was kidding myself into believing that I had a choice in this thing, huh?”

Johnny Blaze, aka Ghost Rider

Contents

Cover (#ue720c326-9fa9-5c10-964f-1a63afc8b72e)

Title Page (#u4f85a5ad-b7f3-5d1b-a0eb-b04ce0d3b964)

Copyright

Praise for Paullina Simons

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue: Real Artifacts from Imaginary Places

Part One: The Master of the Mint

Chapter 1. Fighter’s Club

Chapter 2. Oxygen for Julian

Chapter 3. Silver Cross

Chapter 4. Keeper of the Brothel

Chapter 5. Lord Fabian

Chapter 6. Infelice

Chapter 7. Dead Queen, Revisited

Chapter 8. Bellafront

Chapter 9. Bill of Mortality

Chapter 10. Six Persuasions

Chapter 11. Objects of Outrage

Chapter 12. A Subject of Choice

Part Two: In the Fields of St. Giles

Chapter 13. Rappel

Chapter 14. Gin Lane

Chapter 15. Cleon the Sewer Hunter

Chapter 16. Agatha

Chapter 17. Midsummer Night’s Dream

Chapter 18. The Ride of Paul Revere

Chapter 19. Bucket of Blood

Chapter 20. The Advocate

Chapter 21. Troilus and Cressida

Chapter 22. Grosvenor Park

Chapter 23. Bowl of St. Giles

Chapter 24. Quatrang

Chapter 25. Karmadon

Chapter 26. Best Shakes in London

Chapter 27. Refugees

Part Three: Lady of the Camellias

Chapter 28. Airy’s Transit Circle

Chapter 29. The Prince of Preachers

Chapter 30. Sovereign Election

Chapter 31. The Love Story of George and Ricky

Chapter 32. Pathétique

Chapter 33. Five Minutes in China, in Three Volumes

Chapter 34. The Sublime and Beautiful

Chapter 35. My Love and I—a Mystery

Chapter 36. Foolish Mervyn and Crazy-eyed Sly

Chapter 37. The Valley of Dry Bones

Chapter 38. Ghost Rider

Chapter 39. A Mother

Chapter 40. Two Weddings

Part Four: Tragame Tierra

Chapter 41. The Plains of Lethe

Chapter 42. Masha at the Cherry Lane

Chapter 43. What Will They Care

Chapter 44. Termagant

Chapter 45. Hinewai

Chapter 46. Hula-Hoop

Chapter 47. The Igloo

Chapter 48. Door Number Two

Chapter 49. Heart of Darkness

Keep Reading …

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE (#u07b4a1c9-e1f0-52f0-baa5-837cac4532c7)

Real Artifacts from Imaginary Places (#u07b4a1c9-e1f0-52f0-baa5-837cac4532c7)

ASHTON STOOD, HIS BLOND HAIR SPIKING OUT OF HIS baseball cap, his arms crossed, his crystal eyes incredulous, listening to Josephine trying to sweet-talk Zakiyyah into going on Peter Pan’s Flight. Julian, Josephine, Ashton, and Z were in Disneyland, the last two under protest.

“Z, what’s not to love?” Josephine was saying. “You fly over London with Peter Pan aboard a magical pirate ship to Neverland. Come on, let’s go—look, the line’s getting longer.”

“Is it pretend fly?” asked Zakiyyah.

“No,” replied Ashton. “It’s real fly. And real London. And a real pirate ship. And definitely real Neverland.”

Zakiyyah rolled her eyes. She almost gave him the finger. “Is it fast? Is it spinny? Is it dark? I don’t want to be dizzy. I don’t want to be scared is what I’m saying, and I don’t want to be jostled.”

“Would you like to be someplace else?” Ashton said.

“No, I just want to have fun.”

“And Peter Pan’s magical flight over London doesn’t qualify?” Ashton said, and sideways to Julian added, “What kind of fun are we supposed to have with someone like that? I can’t believe Riley agreed to let me come with you three. I’m going to have to take her to Jamaica to make it up to her.”

“You have a lot of making up to do all around, especially after the crap you pulled at lunch the other week,” Julian said. “So shut up and take it.”

“Story of my life,” Ashton said.

“What kind of fun are we supposed to have with someone like that?” Zakiyyah said to Josephine. “His idea of fun is making fun of me.”

“He’s not making fun of you, Z. He’s teasing you.”

“That’s not teasing!”

“Shh, yes, it is. You’re driving everybody nuts,” Josephine said, and then louder to the men, “You’ll have to excuse her, Z is new to this. She’s never been to Disneyland.”

“What kind of a human being has never been to Disneyland?” Ashton whispered to Julian.

“That’s not true!” Zakiyyah said. “I went once with my cousins.”

“Sitting on a bench while the kids go on rides is not going to Disneyland, Z.”

Zakiyyah tutted. “Is there maybe a slow train ride?”

“How about It’s a Small World?” Ashton said, addressing Zakiyyah but facing Julian and widening his eyes into saucers. “It’s a slow boat ride.”

“That might be okay. As long as the boat is not in real water. Is it in real water?”

“No,” Ashton said. “The boat is in fake water.”

“Is that what you mean when you say he’s teasing me?” Zakiyyah said to Josephine. “You sure it’s not mocking me?”

“Positive, Z. It’s a world of laughter, a world of tears. Let’s go on It’s a Small World.”

After it got dark and the toddlers had left and the crowds died down a bit, the three of them convinced Zakiyyah to go on Space Mountain. She half-agreed but balked when she saw the four-man luge they were supposed to board. Josephine would sit in front of Julian, between his legs, and that meant that Zakiyyah would have to sit in front of Ashton, between his. “Can we try a different seating arrangement?” Z said.

“Like what?” Ashton kept his voice even.

“Like maybe the girls together and the boys together.”

“Jules, honey, what do you think?” Ashton asked, pitching his voice two octaves higher. “Would you like to sit between my legs, pumpkin, or do you want me between yours?”

“Z, come on,” Josephine said. “Don’t make that face. Ashton’s right. Get in. It’s one ride. You’ll love it. Just …”

“Instead of you sitting in front of me,” Ashton said to Zakiyyah, as cordial as could be, “would you prefer I sit in front of you?”

“You want to sit between my open legs?” Zakiyyah’s disbelieving tone was not even close to cordial.

“Just making suggestions, trying to be helpful.”

“Aside from other issues, I won’t be able to see anything,” Zakiyyah said. “You’re too tall. You’ll be blocking my view the whole ride.”

Ashton knocked into Julian as they were about to board. “Dude,” he whispered, “you haven’t told her Space Mountain is a black hole with nothing to see?”

“We haven’t even told her it’s a roller coaster,” Julian said. “You want her to go on the ride, or don’t you?”

“Do you really need me to answer that?”

They climbed in, Ashton and Julian first, then the girls in front of them. Zakiyyah tried to sit forward as much as possible, but the bench was narrow and short. Her hips fitted between Ashton’s splayed legs.

“Can you open your legs any wider?” she said.

“Said the bishop to the barmaid,” said Ashton.

“Josephine! Your friend’s friend is making inappropriate remarks to me.”

“Yes, they’re called jokes,” Ashton said.

“They’re most certainly not jokes because jokes are funny. People laugh at jokes. Did you hear anyone laughing?”

Zakiyyah sat primly, holding her purse in her lap.

Ashton shook his head, sighed. “Um, why don’t you put your bag down below, maybe hold on to the grip bars.”

“I’m fine just the way I am, thank you,” she said. “Don’t move too close.”

“Not to worry.”

They were off.

Zakiyyah was thrown backwards—into Ashton’s chest. Her hips locked inside Ashton’s legs. The purse dropped into the footwell. Seizing the handlebars, she screamed for two minutes in the cavernous dome.

When it was over, Julian helped a shaky Zakiyyah out, Josephine already on the platform, jumping and clapping. “Z! How was it? Did you love it, Z?”

“Did I love being terrified? Why didn’t you tell me it was a rollercoaster in pitch black?”

They had a ride photo made of the four of them: Zakiyyah’s mouth gaping open, her eyes huge, the other three exhilarated and laughing. They gave it to her as a keepsake of her first time on Space Mountain, a real artifact from an imaginary place.

“Maybe next time we can try Peter Pan,” Ashton said as they were leaving the park after the fireworks.

“Who says there’s going to be a next time?” said Zakiyyah.

“Thank you for making this happen,” Josephine whispered to Julian in the parking lot, wrapping herself around his arm. “I know it didn’t seem like it, but she had fun. Though you know what didn’t help? Your Ashton pretending to be a jester. You should tell him you don’t have to try so hard when you look like a knight. Is he trying to be funny like you?”

“He’s both a jester and a knight without any help from me, believe me,” said Julian.

Josephine kissed him without breaking stride. “You get bonus points for today,” she said. “Wait until we get home.”

And other days, while she walked through Limbo past the violent heretics and rowed down the River Styx in Paradise in the Park, Julian drove around L.A. looking for new places where she might fall in love with him, like Disneyland. New places where his hands could touch her body. They strolled down Beverly and shopped for some costume jewelry, they sat at the Montage and whispered in nostalgia for the old Hotel Bel Age that overlooked the hills. He raised a glass to her in the Viper Room where not long ago someone young and beautiful died. Someone young and beautiful always died in L.A. And when the wind blew in from Laurel Canyon, she lay in his bed and drowned in his love and wished for coral trees and red gums, while Julian wished for nothing because everything had come.

But that was then.

Part One (#ulink_bac77d9d-3738-5bf2-a271-38de9799d026)

The Master of the Mint (#ulink_bac77d9d-3738-5bf2-a271-38de9799d026)

“Gold enough stirring; choice of men, choice of hair, choice of beards, choice of legs, choice of everything.”

Thomas Dekker, The Humors of the Patient Man and the Longing Wife

1 (#ulink_0cc6eef8-1a60-5b6c-aeaa-4c210d3f3788)

Fighter’s Club (#ulink_0cc6eef8-1a60-5b6c-aeaa-4c210d3f3788)

ASHTON WAS AFFABLE BUT SKEPTICAL. “WHY DO WE NEED TO paint the apartment ourselves?”

“Because the work of one’s hands is the beginning of virtue,” Julian said, dipping the roller into the tray. “Don’t just stand there. Get cracking.”

“Who told you such nonsense?” Ashton continued to just stand there. “And you’re not listening. I meant, painting seems like a permanent improvement. Why are we painting at all? There’s no way, no how we’re staying in London another year, right? That’s just you being insane like always, or trying to save money on the lease, or … Jules? Tell the truth. Don’t baby me. I’m a grown man. I can take it. We’re not staying in London until the lease runs out in a year, right? That’s not why you’re painting?”

“Will you grab a roller? I’m almost done with my wall.”

“Answer my question!”

“Grab a roller!”

“Oh, God. What did I get myself into?”

But Julian knew: Ashton might believe a year in London was too long, but Julian knew for certain it wasn’t long enough.

Twelve months to move out of his old place on Hermit Street, and calm Mrs. Pallaver who cried when he left, even though he’d been a recluse tenant who had shunned her only child.

Twelve months to decorate their new bachelor digs in Notting Hill, to paint the walls a manly blue and the bathrooms a girly pink, just for fun.

Twelve months to return to work at Nextel as if he were born to it, to wake up every morning, put on a suit, take the tube, manage people, edit copy, hold meetings, make decisions and new friends. Twelve months to hang out with Ashton like it was the good old days, twelve months to keep him from drinking every night, from making time with every pretty girl, twelve months to grow his beard halfway down his chest, to fake-flirt sometimes, twelve months to learn how to smile like he was merry and his soul was new.

Twelve months to crack the books. Where was he headed to next? It had to be sometime and somewhere after 1603. Lots of epochs to cover, lots of countries, lots of history. No time to waste.

Twelve months to memorize thousands of causes for infectious diseases of the skin: scabies, syphilis, scarlet fever, impetigo. Pressure ulcers and venous insufficiencies. Spider angiomas and facial granulomas.

Carbuncles, too. Can’t forget the carbuncles.

Twelve months to learn how to fence, to ride horses, ring bells, melt wax, preserve food in jars.

Twelve months to reread Shakespeare, Milton, Marlowe, Ben Johnson. In her next incarnation, Josephine could be an actress again; he must be ready for the possibility.

Twelve months to learn how not to die in a cave, twelve months to train to dive into cave waters.

Twelve months to learn how to jump.

Twelve months to make himself better for her.

It wasn’t enough time.

Every Wednesday Julian took the Overground to Hoxton, past the shanty village with the graffitied tents and cucumber supports to have lunch with Devi Prak, his cook and shaman, his healer and destroyer. Julian drank tiger water—made from real tigers—received acupuncture needles, sometimes fell into a deep sleep, sometimes forgot to return to work. Eventually he started taking Wednesday afternoons off. Now that Ashton was his boss, such things were no longer considered fireable offenses.

Ashton, unchangeable and eternally the same on every continent, lived as if he didn’t miss L.A. at all. He made all new friends and was constantly out partying, hiking, celebrating, seeing shows and parades. He had to make time for Julian on his calendar, they had to plan in firm pen the evenings they would spend together. He flew back to L.A. once a month to visit his girlfriend, and Riley flew in once a month to spend the weekend in London. When she came, she brought fresh flowers and organic honey, marking their flat with her girl things and girl smells, leaving her moisturizers in their pink bathroom.

And one weekend a month, Ashton would vanish, and was gone, gone, gone, Julian knew not where. Julian asked once, and Ashton said, seeing a man about a horse. When Julian prodded, Ashton said, where are you on Wednesday afternoons? Seeing a man about a horse, right? And Julian said, no, I’m seeing an acupuncturist, a Vietnamese healer, “a very nice man, quiet, unassuming. You’d like him.” Julian had nothing to be ashamed of. And it was almost the whole truth.

“Uh-huh,” Ashton said. “Well, then I’m also seeing a healer.”

There were so few things Ashton kept from him, Julian knew better than to ask again, and didn’t.

He was plenty busy himself. He took riding lessons Saturday mornings, and spelunking Saturday afternoons. He joined a boxing gym by his old haunt near Finsbury Park and sparred on Thursday and Saturday nights. He hiked every other Sunday with a group of over-friendly and unbearably active Malaysians, beautiful people but depressingly indefatigable.

He trained his body through deprivation by fasting for days, by going without anything but water. Riley would be proud of him and was, when Julian told her of his ordeals. He continued to explore London on foot, reading every plaque, absorbing every word. He didn’t know if he’d be returning to London on his next Orphean adventure, but he wanted to control what he could. After work, when Ashton went out drinking, Julian would wander home, six miles from Nextel to Notting Hill, mouthing to himself the historical tidbits he found along the way, an insane vagrant in a sharp suit. In September he entered one of the London Triathlon events in the Docklands. One-mile swim, thirty-mile bike ride, six-mile run. He came in seventh. An astonished Ashton and Riley cheered for him at the finish line.

“Who are you?” Ashton said.

“Ashton Bennett, do not discourage him!” Riley handed Julian a towel and a water bottle.

“How is asking a simple question discouragement?”

“He’s improving himself, what are you doing? That was amazing, Jules.”

“Thanks, Riles.”

“Maybe next year you can run the London Marathon. Wouldn’t that be something?”

“Yeah, maybe.” Julian stayed noncommittal. He didn’t plan on being here next year. The only action was in the here and now. There was no action in the future; therefore there was no future. Devi taught him that. Devi taught him a lot. The future was all just possibility. Maybe was the appropriate response, the only response. Maybe.

Then again, maybe not.

“But what exactly are you doing?” Ashton asked. “I’m not judging. But it seems so eclectic and odd. A triathlon, fencing, boxing, spelunking. Reading history books, Shakespeare. Horseback riding.”

“My resolve is not to seem the best,” Julian said, “but to be the best.”

“Why don’t you begin being the best by shaving that nest off your face?”

“Ashton! That’s not judging?”

“It’s fine, Riles,” Julian said. “He’s just jealous because he’s barely started shaving.”

She came to Julian during the new moon, her loving face, her waving hands.

In astronomy, the new moon is the one brief moment during the month when the moon and the sun have the same ecliptical longitude. Devi was right: everything returned to the meridian, the invisible mythical line measuring time and distance. When the moon and the stars were aligned, Josephine walked toward him smiling, and sometimes Julian would catch himself smiling back. He knew she was waiting for him. He couldn’t pass the time fast enough until he saw her again.

To be on the meridian was life.

The rest was waiting.

A reluctant Julian was dragged back to California by Ashton to spend the holidays with his family in Simi Valley. In protest, he went as he was, heavily bearded and tightly ponytailed like an anointed priest.

Before he left London, Zakiyyah called to ask him about Josephine’s crystal necklace. Josephine’s mother, Ava, kept calling her about it, Z said. Could he bring it with him to L.A.? Julian lied and told her he lost it. For some reason she sounded super-skeptical when she said, are you sure you lost it? It’s not in some obvious place—like on your nightstand or something?

It was on his nightstand.

“Please, Julian. It belonged to her family.”

And now it belongs to me.

“I don’t know what to tell you,” Julian said.

“Who was that—Z?” Ashton said, overhearing.

“Yes, still bugging me about the stupid crystal.”

“The one on your nightstand?”

“Yes, Ashton. The one on my nightstand.”

Over Christmas break in Simi Valley, his parents, brothers, their wives and girlfriends, his nieces and nephews, and Riley all wanted to know when the boys would be moving back home. Not wanting to hurt his mother’s feelings or get her hopes up, Julian deflected. That was him: always dampening expectations.

He cited ethics: they couldn’t break their lease. He cited family: Ashton’s father, after some health problems, had finally retired from the news service, turning over most of the daily operations to his son. He cited friendship: someone had to help Ashton be in charge. Ashton’s livelihood once again depended on Julian.

“Someone has to be Ashton’s wingman,” is what he told his mother.

“Are you sure you’re my wingman, Jules?” But Ashton backed Julian up. It was true, they weren’t ready to leave England yet. “I can’t navigate London without Jules,” Ashton said. “Your son is insane, Mrs. C. Riley will tell you. He’s like an autistic savant. His psychotic knowledge of London is both random and shockingly specific. He has no idea what the exhibits at the Tate look like, but he knows precisely when it opens and closes. He knows the hours and locations of nearly every establishment in central London. He knows where all the pubs are and all the churches, and what stores are next to each other. Though he’s never been on a double-decker, he can tell you the numbers of every bus route. He can tell you what West End theatre is playing what show. He knows which comedians are doing standup. He knows where the gentleman’s clubs are—though he swears, Mrs. C, that he has not been inside, and from the monastic growth on his face, I’m inclined to believe him. He can’t tell you what the best vanilla shake in London tastes like, but he sure can tell you where you need to stand in line to get one—Clapham apparently.”

“Explain yourself, Jules,” Tristan said.

“Because he’s still walking everywhere, isn’t he?” Julian’s mother said, shaking her head, as if suddenly understanding something she didn’t want to about her fourth-born son (or as Julian liked to call it “fourth-favorite”). “Jules, I thought you were better?”

“I am, Mom.”

“Then why are you still looking for that non-existent café? You’re not still dreaming that awful dream, are you?”

Julian was spared an answer by his father. “Son, Ashton told us you’re boxing again,” Brandon Cruz said. “Please tell us it’s not true.” After nearly forty years in the California educational system, the senior Cruz had retired and now kept busy by trying to save Ashton’s flagging store. “Your mother is very concerned. Why would you start that nonsense again after all these years?”

Once, to be in the ring was life. It’s not nonsense, Dad, Julian wanted to say. It’s not nonsense.

“Son, I hate to say it, but your father is right, you shouldn’t be boxing, you’re blind in one eye.”

“I’m not blind, Mom. I’m legally blind. Big difference.” He smiled a weary smile of a man being assailed.

“Still, though, why?”

“He’s trying to improve himself, Mrs. Cruz,” Riley chimed in with fond approval, patting Julian’s back. “He’s boosting his self-confidence, increasing his fitness levels—and muscle mass.” She squeezed his tricep. “He is de-stressing and revitalizing himself. Staying healthy, you know? He’s doing much better, honest.”

“Oh, Ashton!” exclaimed Julian’s mother, “it can’t be easy, but you really are doing a wonderful job with him. Except for the hair, Riley is right, he looks much better. Thank you for watching over him.” Julian’s entire family bathed Ashton with affection and praise. Joanne sat him at her right hand and gifted him a tray of homemade cardamom shortbread! Ashton took the cookies, looking altruistic and put-upon.

Wordlessly, Julian watched them for a few minutes. “Tristan, bro, earlier you asked me for a London life hack?” he finally said. “I got one for you.” He put down his beer and folded his hands. “If you want to display a head severed from the human body, you need to weatherproof it first. Otherwise after a few weeks, you’ll have nothing but a bare skull. You want to preserve the fleshy facial features at the moment of death, the bulging eyes, the open sockets. So, what you do is, before the head starts to decompose, you partially boil it in a waxy resin called pitch—are you familiar with pitch, Trist? No? Well, it’s basically rubber distilled from tar. Very effective. You waterproof the head by boiling it in tar, and then you can keep it outside on a spike to your heart’s content—in all kinds of weather, even London weather. How long will it last, you ask? A good hundred years.” Julian smirked. “Someone said of William Wallace’s preserved head at the Great Stone Gate on London Bridge that in his actual life, he had never looked so good.”

It was Ashton, his mouth full of shortbread, who broke the incredulous silence of the Cruz family at Christmas by throwing his arm around Julian, swallowing, and saying, “What Jules is trying to say is he’s not quite ready to return to the fun and frolic of L.A. just yet.”

“In London in the old days, they used to break the teeth of the bears in the baiting pits,” Julian said in reply, moving out from under Ashton’s arm. “They broke them to make it a more even fight when the dogs attacked the bear. They did it to prolong the fight, before the bear, even without the teeth, ripped the dogs apart.”

“Settle down, Jules,” said Riley, passing him her smart water. “Believe me, we got the message at the parboiled head.”

“Man is more than his genes or his upbringing,” Julian said, refusing the water and picking up his beer instead. “A man is a force of the living. But—he’s also a servant of the dead. As such, he’s an instrument of some powerful magic—since both life and death are mystical forces. The key,” Julian said, “is to live in balance between the two, so as to increase your own force.”

Don’t worry, Riley whispered to a miserable-looking Joanne Cruz. He just needs time.

To be on the meridian, in the cave, on the river, was life.

The rest was just waiting.

Finally the Ides of March and his birthday were upon him. And that meant that after a year of training and boxing and fencing, the vernal equinox was upon him.

“I wish I could bring some money with me,” Julian said to Devi a few days before March 20.

“How is money going to help you?”

“If I’d had money in 1603, I would’ve asked her to marry me earlier. We could’ve left.” It would’ve been different. “I’d just feel better if I had some options.”

“Options.” Devi shook his black-haired head. He was starting to get some gray in it. It was time. The man was over seventy. “Some men are never satisfied.”

“Can you answer my question?”

“There’s no easy way to do what you want.”

“Is there a hard way?”

“No.”

“Why can’t I bring money with me?”

“A thousand reasons.”

“Name two.”

“You don’t know where you’re going,” Devi said. “Are you going to bring every denomination of coin from every place in the world, from every century?”

Julian thought about it. “What about gold? Or diamonds?”

“You want to take diamonds with you.” It wasn’t a question.

“Something of value, yes.”

“You can’t. What I mean is—you literally can’t,” Devi said. “The diamond you talk about, where was it mined, Russia, South Africa? Was it worked on by human hands? Was it then picked up by these hands and shipped to where you could buy it? Was it bought and sold before you ever laid your paws on it, a dozen times, a hundred times? You think it’s sparkly and new just for you? A thousand hearts were broken over your diamond. Bodies were killed, discarded, cuckolded, buried, unearthed. The blood of greed, envy, outrage, and love was spilled over your diamond. Where do you want to end up, Julian? With her, or not with her?”

Having bought a sturdy Peak Design waterproof backpack and loaded it with every possible thing he could need that would fit, ultimately Julian decided not to bring it. Well, decided was a wrong word. He showed it to Devi, who told him he was an idiot.

“I like it very much,” Devi said. “What’s in it?”

“Water, batteries, flashlights—note the plural—a retractable walking pole, crampons, Cliff Bars, a first aid kit, a Mylar blanket, a Suunto unbreakable ultimate core watch, heavy-duty insulated waterproof gloves, three lighters, a Damascus steel blade, a parachute cord, carabiners, climbing hooks, and a headlamp.”

“No shovel or fire extinguisher?”

“Not funny.”

“What about glacier glasses?”

“Why would I need glacier glasses?”

“How do you know you’re not headed into a glacier cave?” Devi paused. “Permafrost in bedrock. Ponded water that forms frozen waterfalls, ice columns, ice stalagmites.” He paused again. “Sometimes the ceiling of the cave is a crystalline block filled with snow and rocks and dirt.”

“You mean full of debris that freezes in the icy ceiling?”

“Yes,” Devi said, his face a block of ice. “I mean full of things that freeze in opaque ice four hundred feet deep. Things you can see as you pass under them but can’t get to.” Devi blinked and shuddered as if coming out of a trance. “That reminds me, best bring an ice axe, too.”

“You’re hilarious.”

“You haven’t mentioned a toiletry kit, a journal, a camera, a neck warmer, and a fleece hat. I feel you’re not prepared.”

“I’m tired of your mocking nonsense.”

“No, no, you’re fine,” Devi said. “Get going. When noon comes, and the blue shaft opens, just send in the backpack by itself to find her. Because there will be room for only one of you. But the bag’s got everything, so it should go.”

“Why can’t I throw the backpack in and then jump after it?”

“I don’t know why you can’t. But as I recall from your story, last time you got stuck. What happens if the backpack gets stuck, and you can’t get to it?”

“Why are you always such a downer? It’s no to everything.”

“I’m the only one in your life who said yes to you about the most important thing,” Devi said, “and here you are whining that I haven’t said yes to enough other things? No to the backpack, Julian. Yes to eternal life.”

“If I can’t bring a backpack, can I bring a friend?” a defeated Julian asked. He would convince Ashton to go with him. He wasn’t ready to part with his friend.

“I don’t know. Does he love her?”

“No, but …” Julian mulled. “Maybe I can be like Nightcrawler. Anything that touches me goes with me.”

“You don’t impress me with your comic-book knowledge,” Devi said. “I don’t know who Nightcrawler is. What if there’s time for only one of you to jump in? You get left behind in this world, and your friend’s stuck in the Cave of Despair without you?”

“I’ll go first, then.”

“And abandon him trapped in a cave without you? Nice.”

But isn’t that what Julian was about to do, abandon Ashton, without a word, without a goodbye? Guilt pinched him inside, made his body twist. “Cave of Despair? I thought you said Q’an Doh meant Cave of Hope?”

“Despair and hope is almost the same word in your language and my language and any language,” Devi said. “In French, hope is l’espoir and despair is désespoir. Literally means the loss of hope. In Italian hope is di speranza. And despair is di disperazione. In Vietnamese one is hy vong and the other is tuyet vong. With hope, without hope. It all depends on your inclination. Which way are you inclined today, Julian Cruz?”

Julian admitted that today, on the brink of another leap through time, despite the remorse over Ashton, he was inclined to hope. “In English, hope and despair are separate words.”

Devi tasted his homemade kimchi, shrugged, and added to it some more sugar and vinegar. “The English borrowed the word despair from the French, who borrowed it from Latin, in which it means down from hope.”

“What about the Russians? You have no idea about them, do you?”

“What do you mean?” Devi said calmly. “In Russian, despair is otchayanyie. And chai is another word for hope. All from the same source, Julian, despite your scorn.”

Julian sat and watched Devi’s back as the compact sturdy man continued to adjust the seasonings on his spicy cabbage. Julian had grown to love kimchi. “What does the name of the cave actually mean?”

“Q’an Doh,” Devi replied, “means Red Faith.”

Julian wanted to bring a zip line—a cable line, two anchors, and a pulley—strong enough to hold a man.

Devi groaned for five minutes, head in hands, chanting oms and lordhavemercies, before he replied. “The anchor hook must be thrown over the precipice. Can you throw that far, and catch it on something that won’t break apart when you put your two hundred pounds on it?”

“Calm down, I’m one seventy.” He had gained thirty of his grief-lost pounds back.

“Okay, light heavyweight,” Devi said. “Keep up the nonstop eating before you grab that pulley. You won’t beat the cave. It’ll be a death slide.”

“You don’t know everything,” Julian said irritably.

“I liked you better last year when you were a babe in the woods, desperate and ignorant. Now you’re still desperate, but unfortunately you know just enough to kill yourself.”

“Last year I was freezing and unprepared, thanks to you!”

“So bring the zip line if you’re so smart,” Devi said. “What are you asking me for? Bring a sleeping bag. An easy-to-set-up nylon tent. I’d also recommend a bowl and some cutlery. You said they didn’t have forks in Elizabethan England. So BYOF—bring your own fork.”

Silently, they appraised each other.

“Listen to me.” Devi put down his cleaver and his cabbage. “I know what you’re doing. In a way, it’s admirable. But don’t you understand that you must rediscover what you’re made of when you go back in? The way you must discover her anew. You don’t know who she is or where she’ll be. You don’t know if you still want her. You don’t know if you believe. Nothing else will help you but the blind flight of faith before the moongate. If you make it across, you’ll know you’re ready. That is how you’ll know you’re a servant not just of the dead and the living, but also of yourself. Will a pole vault help you with that? Will a zip line? Will a contraption of carabiners and hooks and sliding cables bring you closer to what you must be, Julian Cruz?”

Julian’s shoulders slumped. “You’ve been to the gym with me. You’ve seen me jump. No matter how fast I run and leap, I can’t clear ten feet.”

“And yet somehow,” Devi said, “without knowing how depressingly limited you are, you still managed to fly.”

The little man was so exasperating.

A pared-down Julian brought a headlamp, replacement batteries, replacement bulbs and three (count them, three) waterproof flashlights, all Industrial Light and Magic bright. He had a shoemaker braid the soft rawhide rope of his necklace tightly around the rolled-up red beret. Now her beret was a coiled leather collar at the back of his neck, under his ponytail. The crystal hung at his chest. Julian didn’t want to worry about losing either of them again.

“Do you have any advice for me, wise man?” It was midnight, the day before the equinox.

“Did you say goodbye to your friend?”

Julian’s body tightened before he spoke. “No. But we spent all Sunday together. We had a good day. Do you have his cell number?”

The cook shook his head. “You worry about all the wrong things, as always.” Conflict wrestled on Devi’s inscrutable face. “Count your days,” he said.

“What does that mean?”

“Why do you always ask me to repeat the simplest things? Count your days, Julian.”

“Why?”

“You wanted advice? There it is. Take it. Or leave it.”

“Why?”

“You’re such a procrastinator. Go get some sleep.”

Julian was procrastinating. He was remembering being alone in the cave.

“Go catch that tiger, Wart,” Devi said, his voice full of gruff affection. “In the first part of your adventure, you had to find out if you could pull the sword out of the stone. You found out you could. In the second part, hopefully you’ll meet your queen of light and dark—and also learn the meaning of your lifelong friendship with the Ill-Made Knight.”

“What about my last act?”

“Ah, in the last act, you might discover what power you have and what power you don’t. What a valuable lesson that would be. After doing what he thinks is impossible, man remembers his limitations.”

“Who in their right mind would want that,” Julian muttered. “I hope you’re right, and Gertrude Stein is wrong.”

“That wisecracking old Gertrude,” said the cook. “All right, let’s have it. What did she say?”

“There ain’t no answer. There ain’t going to be an answer. There never has been an answer. That’s the answer.”

“Is it too much to hope,” Devi said, “that one day you’ll learn to ask better questions? You haven’t asked a decent one since the one you asked my mother.” What is the sign by which you recognize the Lord?

“I’ll learn to ask better questions,” Julian said, “when you and your mother start giving me better answers.” A baby in a swaddling blanket indeed!

2 (#ulink_cb82929d-4fbd-52a8-80b5-f8609f3fafc1)

Oxygen for Julian (#ulink_cb82929d-4fbd-52a8-80b5-f8609f3fafc1)

HE TRAVELLED THROUGH A DIFFERENT SHAFT, HE TRAVELLED through a different cave, he travelled to a different life.

Noon came to zero meridian at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England, the sun struck the crystal in his palm, the kaleidoscope flare exploded, the blue chasm opened for Julian once more. This time he didn’t get stuck. He slid without resistance, plummeted through the sightless air, skydived. He could’ve brought the bigger backpack, Ashton, Devi, Sweeney, an airplane. It occurred to him that if he didn’t stop falling, he’d crash to the ground. Before he had a chance to ponder this, he plunged into warm water.

It was like falling into terror.

His boots never touched bottom. He panic-paddled from the ebony depths to the surface and fumbled in his cargo pocket for the headlamp. When he switched it on, he felt better; when he slipped it over his forehead he felt better still. The rocky bank was only a foot away. He swam to it, grabbed a ridge, and pulled himself out. At first unsettled by the bathwater temperature—in a cave no less—now Julian was grateful. It could’ve been freezing, and then where would he be. How long did the Titanic’s men last in the northern Atlantic?

It was hard to call any footwear waterproof when everything on him was sopping wet, his Thermoprene suit, his boots, his jacket and pants, his two shirts. Wiping his face, he shined a flashlight around the cave. This was a whole new subterranean world than the one he had encountered the first time he went in, a year earlier. He was at the edge of a black cove at the bottom of a mountainous gorge. Hundreds of ragged feet of rock flared up around him. On two sides of the inlet, the vertical slope was unscalable limestone. But on his bank and the bank opposite, the angle was more gradual, and the walls, though rocky and uneven, looked climbable. Good thing Julian had brought crampons. He attached them to the bottom of his boots, careful not to cut himself on the razor-sharp spikes. The blades scraped against the rock as he took a few steps to adjust to walking on them. It was like balancing on Poppa W’s razor wire.

Feeling heavy and cumbersome, Julian wrung out his jacket, shook himself off like a dog, and checked his equipment before climbing to find the moongate. Batteries, extra lights, her stone on his chest, the beret wrapped in rawhide at the back of his neck, his Suunto watch, an impressive wrist computer with a barometer, altimeter, and heart monitor. Proud of his new gadget, Julian switched on the Suunto to check the cave temperature and his GPS coordinates. How deep was he below sea level? What direction was he facing?

The unbreakable scientifically precise timekeeper showed him noon, the coordinates of the prime meridian, the direction as north. In other words, the exact measurements of the Transit Circle as the sun hit the quartz crystal. Well, that was £400 well spent.

On all fours, Julian crawled up the rough slope to the highest elevation in the cave floor where it hit the limestone wall. The walls were solid. Feeling for the moongate with his bare hands, he walked back and forth along the wall but found no opening. On this side at least, the chamber was hermetically sealed.

Julian knew there had to be a way out because otherwise there would be no river and no Josephine, and also because he could hear running water in the distance. He scaled back down to the swimming hole and shined one of his heavy-duty, high-powered flashlights up and down the cave walls. Finally he spotted it. Across the pool, up the slope in the far corner, as if concealed from casual view, the water trickled out from a perfectly round opening in the bedrock and dribbled down into the cove below.

The only way to get to the other side was to swim across. Julian felt some relief. It wasn’t long-jumping over a canyon, it was just swimming, right? When he first fell in, he had swum to the wrong side, that was all. Shame, but now he would swim to the right side.

He hesitated before he dived. Was the pool a wormhole, a shortcut between two distant points in infinite time and space? He didn’t know. He didn’t think so. It didn’t look far, maybe thirty, forty feet. And the water was warm. He was a good swimmer. He came in seventh in the London Triathlon. Riley had been so proud of him. Granted he didn’t enter the top-level category, but still, he had to swim an entire mile, not a few measly feet. Full of confidence, Julian jumped in, like the starting gun had gone off. He swam methodically, pacing himself, without undue exertion. The headlamp illumined only a few feet of black water in front of him. He couldn’t see the other bank. No matter. A minute or two at most and he’d be there. He was glad he had listened to Devi and brought a minimum in his backpack. Fifty pounds of extra weight would’ve been a burden.

Julian swam and swam and swam and swam. It felt longer than forty feet. He must have gotten confused, lost his orientation. It had looked so easy—swimming forward—but for some reason forward wasn’t getting him to the other side, and his headlamp with its short beam was annoyingly little help.

He swam and swam and swam and swam. Above him the cliffs loomed, ominous and oppressive like stone Titans. How could he see those, much farther away, but not see the opposite bank of a medium-sized cave pool?

Julian began to tire, to feel oppressively heavy. And when he started to feel heavy, he panicked.

And when he panicked, he started to sink.

His boots, jacket, gloves, flashlights all felt like anchors strapped to his body. Yes, the water was warm, but so what? He was being sucked into a slow warm drain.

Was he just treading water or actually moving forward? He spun around but couldn’t see where he had been, nor where he was going. He was in the middle of nothing and nowhere. He stopped swimming, held his breath, listened for the trickling stream on the rocks. He heard no sound except his anxious gasps.

He didn’t know what to do.

There was no going back. The only way out was through it.

Julian resumed the front stroke, in slow motion. His body was weighted down, as if concrete blocks were tied to his feet. The body refused to cooperate with staying afloat. He tried to turn onto his back for a rest, but kept sinking. When he stopped flapping his arms, he sank. Even as he swam forward, he sank. It became nearly impossible to hold his head above water.

He flung away the waterlogged gloves, the extra lamps, the batteries, the carabiners, the hooks, his non-working £400 Suunto Ultimate watch. He threw off his jacket and unstrapped and kicked off his boots with the metal crampons. He unzipped and pulled off his cargo pants. He discarded everything but his headlamp and a thin Maglite that fit into a chest pouch in his wetsuit.

And still he sank. Fear was heavier than fifty pounds of gear.

His head slipped under water. He resurfaced, opened his mouth, tried to swim. The effort required to stay afloat became greater. His breath got shorter, the time under got longer. In panicked desperation, gulping for air, Julian lowered his chin to his chest and rammed forward.

His headlamp hit something solid and immovable. Rock! The lamp cracked, slipped off his head and vanished into the deep. He grabbed on to the edge of the rock and after a few moments of gasping, pulled himself out.

For a long time he lay in the darkness getting his breath back. Had the headlamp not been on his head to absorb the blow, he would’ve cracked his skull open. He must’ve been swimming pretty fast, despite his clear perceptions to the contrary. That was quite a jolt he had received. What an ugly cheat it was, not to be able to trust your own senses.

So—four sources of light were not enough. New boots, hooks, spikes, new jacket, new pants, not enough. Extra batteries, bulbs, gloves, all of it at the bottom of the bottomless cave. After all the preparation to offer his woman a new and improved man, Julian was right back on novice course, climbing a steep uneven terrain, barefoot and without his clothes, holding a small cheap flashlight between his chattering teeth.

Past the moongate, the river was shallow and flowed slowly—and in the wrong direction! It flowed back toward the black hole cove. After a curve in the cave and a shallow whirlpool, it finally turned and flowed in the direction Julian was wading, filling the barrel-shaped passage to his knees. The cylindrical walls shimmered with hallucinations, with carved etchings. Julian no longer believed his eyes. It could be a Rorschach test. He saw what he wanted to see, not what was really there. But why would he want to see illusions of writhing beasts with open groaning, screaming mouths, why would he wish to see colliding live things loving each other, fucking each other, killing each other? In many cases all three.

Before long, trouble came. It came in the form of water that rose to his legs and then to his waist. The Thermoprene suit was wet inside, and the trapped moisture kept him warm, but the water that seeped in and trickled down his ribs and back also made him itch like a motherfucker. The cave remained troublingly warm, as did the water. Weren’t caves supposed to be 54ºF at all times? Maybe not magic caves. He should’ve brought an inflatable boat. He was so tired. There was no ledge or shelf for him to rest on, no dry ground. Endlessly, relentlessly, half-blind, Julian trudged hip-deep in water, avoiding the images that filled his defective vision, of gods and men and beasts intertwined.

He should’ve known better than to complain about cave drawings. As soon as they vanished, the water rose to his chest. He could no longer walk in it. That meant he could no longer carry the flashlight or even hold it in his mouth. In impenetrable darkness, he swam. Either the water level kept rising or the cave narrowed, because when Julian lifted his arm for the front stroke, he hit the roof of the cave. The space between the surface of the water and the ceiling—in other words the space in which he breathed—was no longer large enough to fit his head. He had eight inches, then six, then four.

He stopped swimming, turned on the flashlight, stuck it between his teeth, and put both palms on the ceiling to rest for a bit while he looked around. He lifted his mouth to the limestone and breathed through the slit of remaining air. He couldn’t stay still for long because the channel began to fill up with black rushing water. Oh—now it was rushing. It swallowed him and pitched him forward before he had a chance to put away his one light. While Julian was flung about like a rubber duck, the flashlight slipped out of his hands and swirled into the void, and Julian once again was plunged into wet spinning darkness.

What did he learn in advanced spelunking that could help him now? The first thing he remembered was decidedly unhelpful.

Never cave alone.

Dennis, his unruffled instructor, could not have been more plain. The only reasons to be alone in a cave were injury and emergency.

As he tumbled through the gushing current, Julian came up with a third reason. Insanity.

Cave diving was the most advanced, specialized, dangerous of all caving activities. Without training, Dennis said, no human being had the knowledge to stay alive. Only months of rigorous preparation could help you. You had to learn to control five things on which your life depended. If those five things weren’t built into your muscle memory, you would die.

Not could die.

Would die.

Julian recalled precisely two things.

Number one: respiration.

Number two: emotion.

The first one was impossible, since he was fully submerged in the current, and as for the second one, check. Emotion aplenty.

You have no training for open water, he kept hearing in his head. Stop. Think. Picture the reaper. See her face. Prevent your death. Respiration. Emotion.

What else?

His head bobbed up for a moment, he gasped for air, was pulled under, and then driven forward. But there was air above him! There was oxygen for Julian. Sounded like a song.

Respiration!

Emotion!

Calm yourself!

Think!

Another bob.

Another gasp.

Oxygen for Julian.

He must keep his mouth closed. If he swallowed water and his lungs filled up, he wouldn’t be able to continue bobbing like a buoy. He would sink. Think! Breathe! Another bob. Another gasp. Oxygen for Julian.

Trouble was, when his mouth was closed, he couldn’t breathe.

How could he save her when he couldn’t even save himself?

Josephine. Mary.

Calm yourself. Think! Breathe.

Oxygen for Julian.

All he could feel was panic for his life.

Finally, Julian found something to grab on to, a churning plank. Pulling himself on top of it, he lay down on it lengthways, grabbed the short edge with both hands, put his head down, gurgled up a lungful of water, and was asleep in seconds. No terror was so strong that it could force his eyes open.

3 (#ulink_b6ba4edd-8a9f-59d4-a7c4-afc17594aa93)

Silver Cross (#ulink_b6ba4edd-8a9f-59d4-a7c4-afc17594aa93)

HE WAKES UP BECAUSE HE’S BURNING. HE CAN’T TELL WHAT’S wrong with him, only that it’s so hot, he wants to crawl out of his skin to cool down. The plank he drifts on is hot, the water underneath him is hot, the air is hot. Not warm like cove water, but hot like near boiling. He falls sideways into the water, and the steaming plank, scorched as a summer deck, drifts down river.

Julian can finally stand, and even though his flashlight is gone, the cave isn’t completely without light. He can see.

Why is it so blisteringly hot? His body itches intensely under the Thermoprene. He unzips the suit, pulls it halfway down, stands against the wall of the cave and like an animal rubs against the rock to relieve his back. He pulls the suit down to his knees and scratches his legs, his stomach. It’s better, but not great. The more he scratches, the more it itches, his skin as if crawling with a thousand mosquitoes feasting on his body.

Now that he’s out of the water, Julian remembers the other three things he learned about cave diving. Posture. Propulsion. And buoyancy. How the hell do you learn buoyancy, he thinks. You either float or you don’t. I know this for a fact. Idiots.

Julian is so excited to be alive even though he is fucking itchy.

No way he can zip up the suit again. He tries. As soon as the foam fabric touches his body, he’s in a frenzy. Both he and the suit need to dry, but as he dries, he starts to sweat, and the salt in his sweat makes his itchy body burn. What a hot mess he is. He’s got to get out, get to somewhere cooler. Where is he? Where did the river bring him?

Leaving the wetsuit dangling at his waist, Julian climbs up the slope, away from the river and toward the dim flickering light. He’s burning the soles of his bare feet and the palms of his hands on the hot rocks. The light that illumines a sliver of the cave is somewhere above his head. He keeps climbing to it, as if up a spiral staircase carved into the rocks, up, up, up, and round and round.

There’s an overhanging wooden ledge above him. Wooden? He pulls himself up and GI Joes through a narrow opening, crawling out into a tight, musty space with timber rafters. It looks like a secret closet under a dormer. It’s half-height, but there’s a door in front of him! The ambient flicker that led him here is streaming through a keyhole in that door. He hears muffled voices. He peeks through the keyhole.

He sees a small section of a shimmering room lit entirely by candles placed so close together it looks like a fire. How long did it take someone to make those, Julian thinks, knowing what a thankless and tedious task it is, and just as he thinks this—he leans on the door too hard. It swings open and he falls through.

As he tumbles out, he knocks over the small table, and the stacked candles fall in a melting waxy jumble onto the floor. The rug fringe catches fire. Someone in the room squeals.

“Careful! You’ll burn the house down!”

Someone else squeals. “Well, don’t just sit there. Put it out!”

Julian swats the rug with his bare hands and blows at the downed candles. With potential disaster averted, his eyes adjusting to the dim remaining light, he surveys the room, still on his knees.

Before he fell into the dormered space, his plans were grand. He was prepared. He’s read, he’s fenced, he’s cave dived, he is a daredevil, he isn’t scared.

But in this room, the plans change. Between two windows there’s a bed, and on this bed sit two naked women intertwined, pressing their breasts against one another and eyeing him with lanquid curiosity. The burning fireplace is behind them. He can’t see the women’s faces, only the contours of their naked bodies. They’re like iridescent drawings. But mostly they’re women’s naked bodies.

“Well, hello there,” one girl says. “Where did you come from? Did you sneak in to spy on us? That costs extra, you know.” The girl has a British accent, not posh—not that he expects posh here, wherever he is. “Look at him, he’s got a beard, how delicious. Maybe we won’t charge him?”

“Well, that would hardly be fair,” whispers the other, also in a British accent, “we charge everyone else.”

“Oh, don’t be a ninny, let him sample the goods. We can charge him double next time, right, handsome? Come here,” the girl croons. “Come here, precious.” Two pairs of female arms reach out to him. “Don’t be shy,” the girl says, wiggling her fingers at him, motioning him forward. “Don’t be afraid of us, we won’t bite.”

Julian gets up off the floor, stands straight. They appraise him, their smiles widening. “Well,” one girl says, “maybe bite a little.” All he can see in the semi-darkness is the whites of their teeth and the length of their brown hair. He is about to ask if he should light another candle—to see them better—but they grab his hands and pull him onto the bed, onto his back, crouching around him, interested and unafraid. They stroke his beard, pat his chest, tap his shoulders and arms, examine his necklace close to their faces, rub his stomach. “Look how warm you are, how damp you are. Why are you sweating? Are you hot?” They giggle. They pull at the wetsuit. To be helpful, Julian mutely shows them how to work the front zipper.

The nubile girls get distracted by the zipper of a commercially made suit. With some chagrin Julian notes that they’re more fascinated by the zipper than they are by the naked man underneath it. They unzip him past his groin, and with delight zip him up to his throat. Instead of playing with Julian, they’re playing with the zipper.

The suit is damp. His skin is damp. He had just been itchy and uncomfortable. He had just been tired and thirsty. Not anymore. He’s less the sum of all other parts than he is of the awakened primal hungry thing. He takes in their curves and dark nipples, their swaying white breasts, their loose hair and limbs amber in the candlelight. One has straight long brown hair, one wavy thick slightly shorter brown hair. One has larger breasts, one has larger hips. They’re both rounded and soft. They’re on their knees on the bed, joyfully running the polymer zipper up and down over Julian.

This is so unexpected.

Julian smiles.

“Ooh, what’s this?” one girl coos.

“Do you mean the zipper?” he asks. “Or …”

“What’s a zipper? No, this squishy black covering all over you. How do you squirm out of it? Oh, look, it stretches. And what’s this around your neck, some kind of talisman?”

“Yes,” he says, pulling the girl’s hand away from it and trying to glimpse into her shadowed face. “It’s some kind of talisman.”

“How do we get you out of this unwieldy thing?”

“You could stop playing with the zipper and pull the suit off my feet.” Julian is on his back. “Or do you want me to do it?”

“No, no, handsome, you just lie there, you’ve done enough, don’t you think? You almost started a fire. We’ll find other things for you to do.”

The women get off the bed and pull off his wetsuit. He feels better now that he is naked himself. He lies on a bed of silk sheets, while two young beauties, bounteous and bare, stand at his feet, lustily appraising him. They’re both delicious, both about the same height. Is one of them his? Julian hopes so. It’s hard to tell in the ghostly light. They’re both so beautiful, and he is so fired up.

“Are you sure we should touch him? Remember what the Baroness said? What if he carries the sickness?”

“Where are you from, sire?”

“Wales. The unknown forest.”

“There you go. Wales. The unknown forest. Where’s that?”

“Over yonder,” Julian says. “Where there is no sickness.”

“There you go. Just look at him. What sickness? I’ve never seen a healthier specimen of a man, have you?”

“I suppose not.”

“He is so robust, so full-bodied.”

“He is.”

“He’s the epitome of male health. Have you no interest in touching him where he’s especially strong and vigorous? Then leave at once. I’ll have him all to myself.”

“I didn’t say I had no interest in touching him.”

The girls stand, admiring him, smiling. He lies, admiring them, smiling.

The room is warm and getting warmer. Everything that can stir in Julian, stirs, simmers, gets hotter. Everything that can be switched on and lit up is switched on and lit up.

“What are your names, ladies?” Please let one of them be his.

“What do you want them to be, sire?”

“Josephine,” Julian says, his voice thick. He opens his arms.

“Your wish is my command,” says one. “I’m Josephine.”

Not to be outdone the other chimes in, “I’m Josephine, too.” They crawl to him, lie next to him, one on the left, the other on the right, pressing their breasts into his ribs. What good did Julian ever do in his life to deserve this? One kisses his left cheek, one kisses the right. One kisses his lips, the other pushes her away and kisses him, too. They run their hands over his body, from his long beard to his knees. They ooh. They ahh. He puts his arms around the girls, leaves his hands in their hair, one head silky and straight, the other soft and thick. He wills himself not to close his eyes.

“What would you like, sire?” one croons in her easy sexy voice.

“What we mean to say is, what would you like first?” the other croons in her easy sexy voice.

“I don’t know,” he murmurs. He doesn’t know where to start. He wants it all. “What have you got?”

A better question might be what haven’t they got.

For his visual pleasure, the girls fondle each other leaning over him, playing with each other’s breasts. Two sets of breasts are heaved into Julian’s hands, two sets of nipples are pressed into Julian’s mouth. They fight to climb on top of him and for his auditory pleasure, argue over which one gets to mount him first, a discussion Julian deeply enjoys. After a while, he informs them—again, trying to be helpful—that they can take turns or, if they wish, both get on top of him. He points to his mouth. They eagerly assent. For his tactile pleasure, they give him a lot, and finally—God, finally—all at once. They move him to the middle of the bed, throw off all the blankets and pillows, and ride him like a carousel. One mounts him, first facing him, then facing away from him. One presents herself to his mouth. They switch. They switch again. Their lack of modesty is as stunning as it is magnificent. They pull him up, both get on their hands and knees in front of him and summon him with their moans and beckoning open hips to alternate between them. A minute for me and a few seconds for her, sire. No, no, a minute for me and a few seconds for her, sire. Julian obliges. No one wants the bell at the end of that round to ring, not them, and emphatically not him.

While mortal man rejoices, refracts and rejuvenates, all the while wishing he were immortal and needed no bells and no rounds, the roses and lilies show him that downtime can also be wonderful, by intermingling with each other in ways Julian has only dreamed of. The flowers have reappeared on the earth. The girls make kissing and sucking sounds when he uses his mouth and fingers to please them, as if to guide Julian aurally to what they would like him to do to them orally.

He fights the desire to close his eyes as he is smothered under their warm abundant flesh in friction against every inflamed inch of him. With impressed murmurs, they cluck over his rigid boxer’s body, they praise his drive, his short rest, his devouring lust. They kiss his lips until he can’t breathe. One slides south. Aren’t you something, she purrs. She kisses his stomach. Josephine, she calls to the other one. Come down here.

I’m coming, Josephine. They both kiss his stomach. Their hair, their kisses, their lips, their hands slide farther south. His hands remain on their heads, in their hair.

Four breasts bounce against him, four hands and two warm mouths caress him in tandem. They feed him and drink from him and melt in the fading fire. One scoots up to his face, holding on to the frame of the bed and lowers her hips to him. One remains down below.

I’m coming, Josephine.

They entrust him again and again with their bodies and their happiness, and he bestows them with his own gifts because he doesn’t like to deny insatiable beautiful girls with lips of scarlet.

If you keep this up, next time I’ll charge you double, one moaning girl murmurs.

If you keep this up, next time I’ll give it to you for free, murmurs the other.

Julian can’t decide which murmur he prefers.

The honeycomb hours pour forth in a treacly feast, in debauched splendor. The fire goes out. The room is lit only by faint moonlight through the open windows. It’s hot, and outside is quiet except for occasional bursts of revelry on the street below. Exhausted, the girls lie in his arms during another break, ply him and themselves with house wine, and confer to him all manner of knowledge.

Julian learns he’s near Whitehall Palace, in a house of pleasure named the Silver Cross. So for the second time, he’s back in London. He knows the tavern fairly well. The Silver Cross, a block away from Trafalgar Square, is one of London’s oldest pubs. He’s drunk and eaten there a few times with Ashton. The selection of beer is first rate and the red meat is tender. Whitehall, a short stroll from Westminster, was once the residence of kings. In 1530, Henry VIII bought the white marble palace from a cardinal, lived there, died there. A fire had decimated the palace (a fire? or the fire?) and now only the Banqueting House remains, and the eponymous street. It’s July, the girls inform him, which explains why it’s so bloody hot, that and the fiery female flesh scorching his hands.

Before Oliver Cromwell in his Puritan zeal shuttered all of London’s playhouses, pubs and houses of bawd, Charles I licensed the Silver Cross as a legal brothel and the irony is, to the present day the license has never been revoked. The king was beheaded, England became a republic, there was a civil war. There was so much else to think about besides a brothel license. For four hundred years, it had slipped everyone’s mind. Julian read this on a plaque in the pub, while dining and drinking there with Ashton.

The Silver Cross is run by a woman named Baroness Tilly. She has ten high-quality girls and “ten rooms of pleasure.” The house is colloquially called the Lord’s Tavern after its most frequent patrons—“the Right Honorable Lords Spiritual and Temporal of the Kingdom of Great Britain, England, Scotland, and Ireland in Parliament Assembled!” the girls proclaim to him in happy unison. They do so many splendid things to him in happy unison. With the recently re-established House of Lords, the Temporal Peers have become the tavern’s most generous benefactors. They have unlimited time, unlimited money and unlimited vices. The girls are top-notch, game for all sorts of debauchery (as Julian can attest), and most importantly (after the recent “epidemic of death”), clean. The girls and the rooms adhere to rules of purity not found in other similar establishments, “like that pig-pit the Haymarket, or Miss Cresswell’s in Clerkenwell.”

Did someone say Clerkenwell?

Yes, sire, do you know it? It’s filthy.

I know it. It’s not so bad. His heart pinches when he remembers Clerkenwell, the rides to Cripplegate through the brothel quarter on Turnbull Street. He wants to peer into the girl’s face but can’t keep his eyes open.

At the Silver Cross, the rooms are spotless, richly decorated, well furnished. “And the girls, too,” Julian murmurs sleepily. His body is raw, sore, sated in all its imaginable and unimagined earthly cravings. This is his favorite room in the world.

Yes, this room is nice, the girls murmur in return, but there are a few others that have bathtubs, and in those rooms the girls can soap him, and lather him, and wash him. Would he like that, for the eager girls to soap his naked body? Look, it’s almost dawn, one girl says, what’s better than dawn by cocklight? Nothing, says the other, tugging on him and smiling. Nothing’s better than the crowing of the cock to usher in a new day.

Julian is nearly unconscious. Yet the mention of being soaped by the caressing hands of the lush sirens in his bed calls him to attention and turns the girls once again into warm quivering masses of excited and groany giggles—

The bedroom door is thrown open. The giggling stops. In the frame stands a tall woman wearing yesterday’s theatrically overdone face makeup and an outrageous pink velvet housecoat with a red fringe.

“Mallory!” she shouts. “How many times have I told you—No! Bad girl! No, no, no, no, no!”

One of the girls scrambles off the bed and searches the floor for her clothes.

“This isn’t your job! Do you know what your job is?”

“Yes, Aunt Tilly.”

Julian nearly cries. Don’t go, Mallory! Her back is to him, but if only he could catch a glimpse of her face …

“No, I don’t think you do know what your job is. And it’s Baroness Tilly while you’re working—and I assume this was work?”

“All my other work was done, Baroness.” The girl throws a chemise over herself, a skirt, a flowy blouse, an apron. She ties up her hair. “I was finished for the day.”

“You don’t look as if you were finished.”

“Just wanted to make some extra money, Baroness …”

“That’s everybody’s excuse. But you know I forbid it. Your mother, may she rest in peace, forbid it. I will not tell you again. I’m going to send you to the South of France if you don’t stop this. Do you want to be sent away with your boorish benefactor? He’ll be a lot stricter than me.”

“No, Baroness.”

“I didn’t think so. Then, go do what you’ve been hired to do and stop the wickedness at once. Oh—and who is this man? I allowed you upstairs at the start of the night for the viewing pleasure of Lord Fabian, and here you are, at nearly dawn, with another man in your bed.”

Viewing pleasure? Lord Fabian? What? Julian lifts his head off the pillows. Baroness Tilly, a broad, vulgar woman, turns her unwelcome attention to him. “I don’t remember you walking past me, good sir, and I certainly don’t remember you paying me. No one goes upstairs with my girls without me knowing about it. Announce yourself! Mallory, Margrave, who is this man?”

Still in bed with Julian, Margrave, a most unblushing flower a few minutes earlier, gets tongue-tied. Her brazen demeanor vanishes. She stammers.

The standing girl comes to his aid. “I believe he said he’s here for the position of the keeper of the house, Baroness. Aren’t you, sire? He came from the Golden Flute across the river. Madame Maud sent him.”

“So why is he up here with you? Why didn’t he speak to me first if Maud sent him?”

“He wandered in and got lost, he didn’t see you.”

“Oh, enough! There’s clean-up needed in Room Four. Golden Flute indeed. I am so tired of your nonsense, Mallory, so very tired.”

Mallory rushes past the hyperventilating baroness. Margrave covers Julian with a quilt. He finds it fascinating that she remains uncovered as if it’s only his modesty she is concerned with.

“Margrave, don’t sit there like a wanton hussy, get dressed. It’s morning. What is your name, sir?”

“Julian Cruz.”

“Well, Master Cruz, this is not the way I usually make the acquaintance of the keepers of my house. Did you need to sample the product before you could hawk it? I admire that. We have only the best here, sire. These are not the usual wagtails and bunters you’re used to at the Golden Flute, I can assure you.”

Julian doesn’t need to be assured. He knows.

“Our old keeper died last month without any warning. A little warning would’ve been so helpful. It would’ve given me and the girls time to prepare. This is a house run nearly entirely by women and there are things we do well, wouldn’t you agree, Master Cruz?”

Julian would agree.

“But there are other things we cannot do. Fix doors, patch holes, replace broken lanterns, fix the roof. We have lanterns that have not been filled with oil because Ilbert refuses to buy some, and the candles are running low, as is the soap. After the recent health problems, soap is an absolute necessity. We’re quite busy here. I hope you can manage. Marg, go tell Mallory to prepare the gentleman’s room, and you, sir, meet me downstairs as soon as you’re attired.” (Attired in what exactly, Julian wants to know.) “I’ll go over the rest of the details, and we’ll raise a glass. Margrave—spit spot.” With that, Baroness Tilly claps her hands twice, and exits.

As soon as she’s gone, Margrave jumps out of bed.

“We could’ve got into so much trouble,” she bleats, tying the sashes of her robe. “The Baroness hates it when Mallory disobeys. Not that she does anything about it, the girl is a terror.” She smiles. “But who could resist you? Even heartless Mallory couldn’t. Wait here, I’ll be right back with a robe. You should ask the Baroness for an advance, go buy yourself some clothes befitting a brothel keeper.”

“What do they wear, tuxedoes?”

“If you like, sire. Forever naked would be my preference.” Beaming, she straightens out, and Julian catches her eye. It’s dawn, he can see her smiling round face. She is pretty and young and sexy. Low light, a tired mind, lust, pounding desire are all great equalizers.

But Margrave is not his girl.

4 (#ulink_f03c00b7-7702-5b6f-a7fb-81eae034a7c7)

Keeper of the Brothel (#ulink_f03c00b7-7702-5b6f-a7fb-81eae034a7c7)

THE ALE IS A COVER. ALE FOR BREAKFAST, ALE FOR DINNER, ale for supper. It’s a euphemism for the other things that go on at the Silver Cross. Yet downstairs, the wood-paneled restaurant-bar appears as just that: a well-to-do tavern, patronized by connected and wealthy men (much as in the present). The ale is top-notch, Baroness Tilly tells him, the food superb.

Naked underneath a black velvet robe, Julian sits across from the Baroness, feeling ridiculous. Tilly’s pink robe has been replaced by hooped petticoats and gaudy layers of sweeping silk ornamental fabrics with puffy sleeves and lace velvet collars. She wears a huge blonde wig, her eyes hastily drawn in black and her oversized mouth made ever larger by smeared red cake-paint.

The pub is narrow and tall, with flagstone floors and tables of heavy oak. It’s upholstered in leather, draped with blue velvet curtains, and set with crystal and fine china. The breakfast tables are lined with white napkins.

“It’s a beautiful place, wouldn’t you agree,” the Baroness says. After colorfully describing what’s expected of him (the daily inspections of the girls before they begin work is one of Julian’s more intriguing duties), she offers him a salary and only as an afterthought inquires about his experience, which he recounts to her just as colorfully—parroting her own words from minutes ago (taking extra time to detail how he imagines the inspections of the girls might go). He would like to begin immediately. Where are these girls? When can he inspect them, so he can find his girl?

He and the Baroness have a sumptuous breakfast of porridge and milk, smoked herring, spiced eel pie (“caught fresh from the Thames just yesterday!”) and bread and marmalade. And ale. The Baroness lingers over breakfast as if starved for some normal company, entertaining an increasingly impatient Julian with stories about the Silver Cross. A hundred years earlier, a man named Parson from Old Fish Street was paraded in shame down Parliament Street for selling the sexual services of his apparently accomplished wife. After spending years in prison, he opened the Silver Cross in revenge, and his wife became the cornerstone of his business.

Julian tells the Baroness he’s read somewhere that a prostitute was murdered in the Silver Cross, and it’s been haunted ever since.

“I don’t know nothing about that,” the Baroness says, frowning. “Where did you read that, the Gazette?” Grudgingly she admits that the Silver Cross has only recently reopened, having been shuttered for the better part of last year, “because of the horror that befell all London. But we’ve had no recent murders here, sire, I can assure you. Murder is very bad for business.”

“What horror?” Julian asks and instantly regrets it when she stares at him suspiciously. He clears his throat. “I meant why stay shuttered for so long?” His eyes dart around, trying to catch the date from the newspaper lying on the next table.

“Where are you from, good sir, that you don’t know about the terrible pestilence that destroyed our town?”

The unknown forest, Julian tells her. Wales. Largely spared from the plague. One of these days, Julian will meet an actual Welshman and be promptly pilloried on Cheapside.

“I thought you’ve just come from across the river?” She lowers her voice. “You know, that’s where the Black Death took wind. From south of the river.”

Julian nods. It’s common knowledge—everything is worse south of the river.